A Methodological Framework for Inferring Energy-Related Operating States from Limited OBD Data: A Single-Trip Case Study of a PHEV

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Development of operational signatures of a PHEV driving in pure electric mode using unsupervised clustering applied to real-world OBD data [16].

- Use of a multidimensional feature space (power, speed, acceleration, altitude, SOC), allowing for a physically interpretable decomposition of operating states.

- Introduction of an indirect method for identifying regenerative braking phases using kinematic–topographic relations, overcoming the limitations of OBD systems.

- Demonstration of the influence of urban topography on the electric drivetrain’s operating states, an aspect rarely addressed in PHEV research [17].

- Construction of a clustering-based methodology that can be directly used for eco-driving assessment, route optimization, and fleet-level energy efficiency analysis [18].

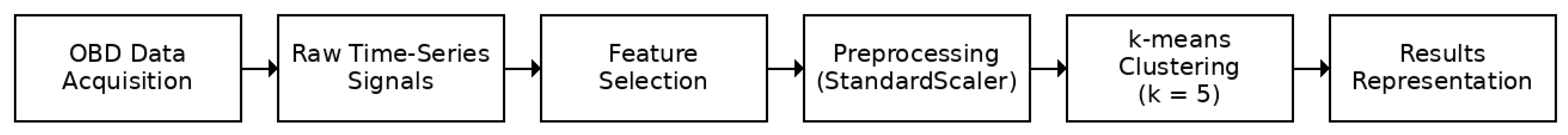

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Vehicle and Data Acquisition

2.2. Available Variables and Feature Selection

- electric motor power at the wheels (kW),

- vehicle speed (km/h),

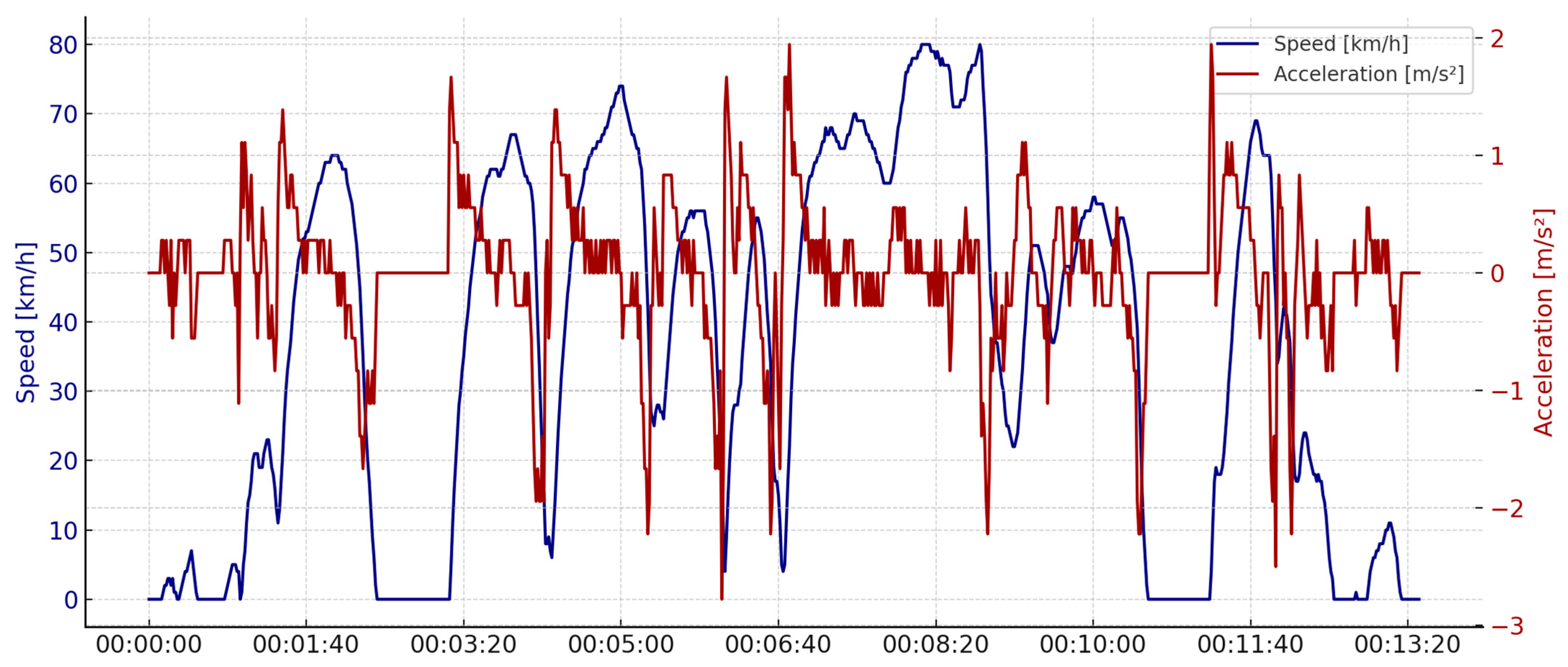

- longitudinal acceleration (m/s2).

2.3. Data Preprocessing and Scaling

2.4. Unsupervised Clustering Procedure

2.5. Output Representation and Consistency Checks

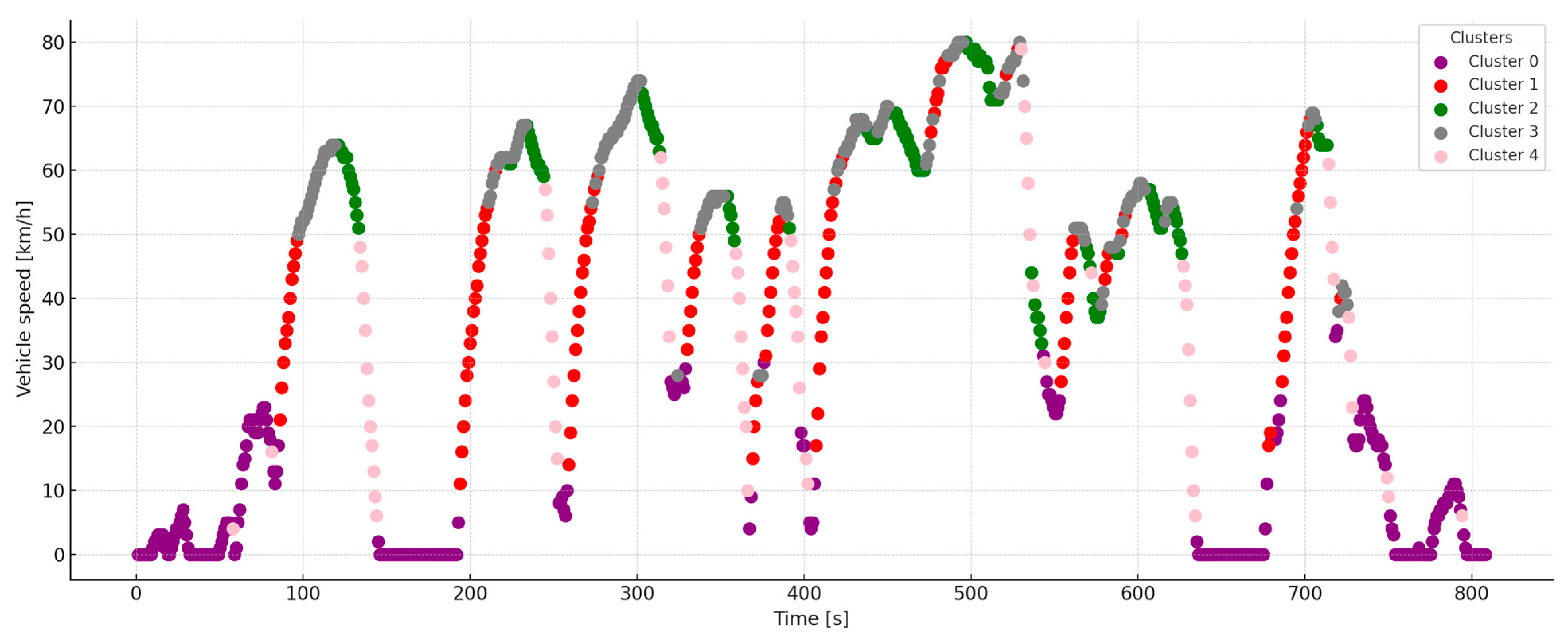

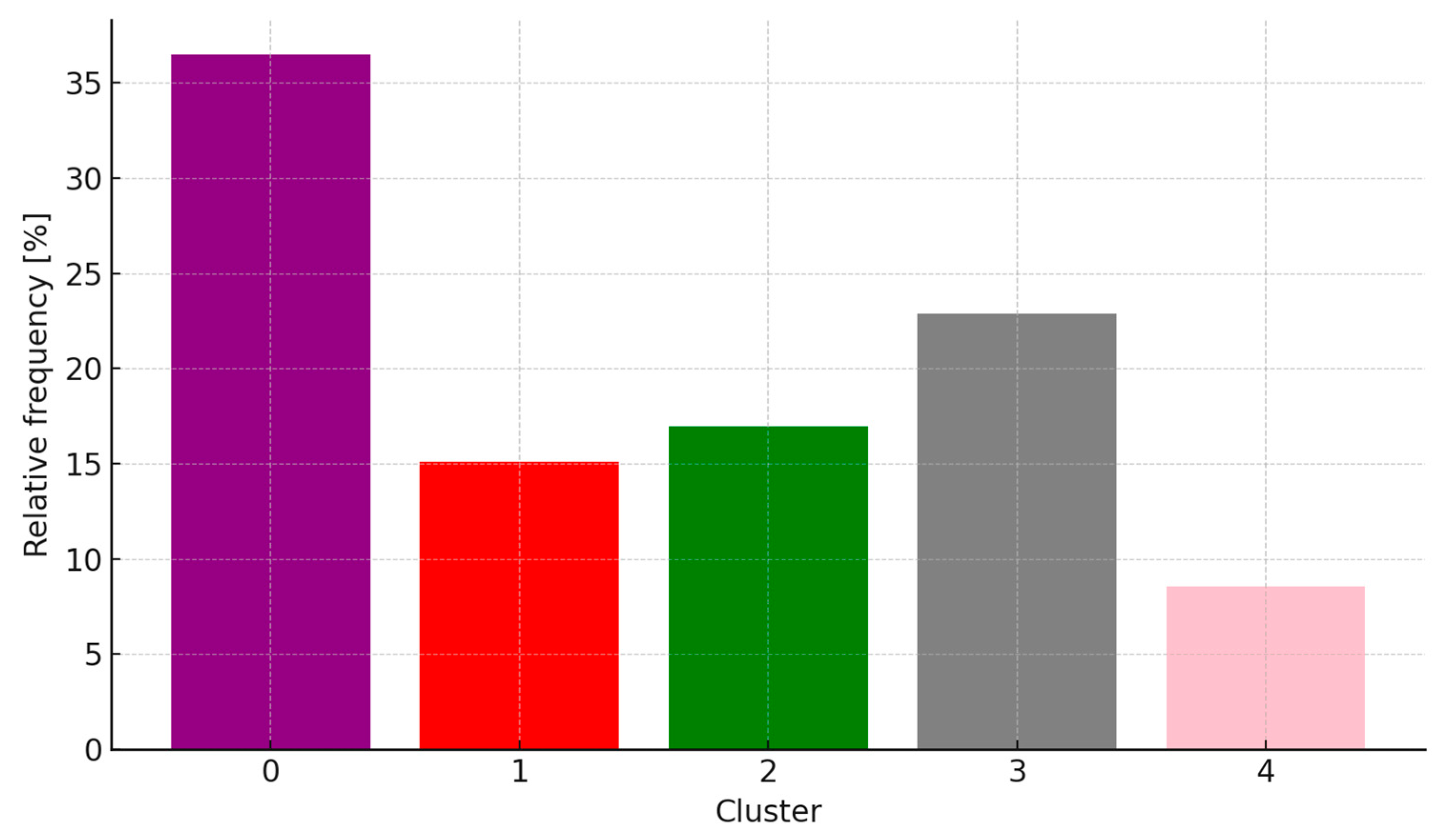

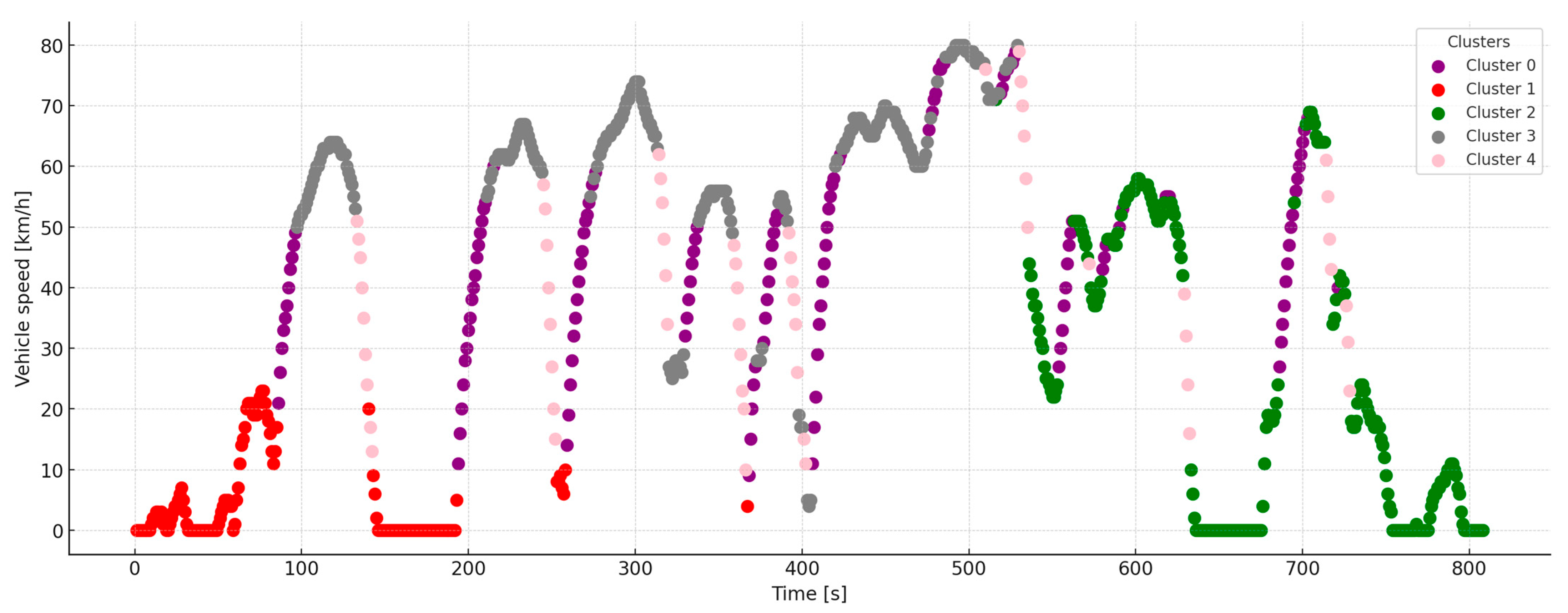

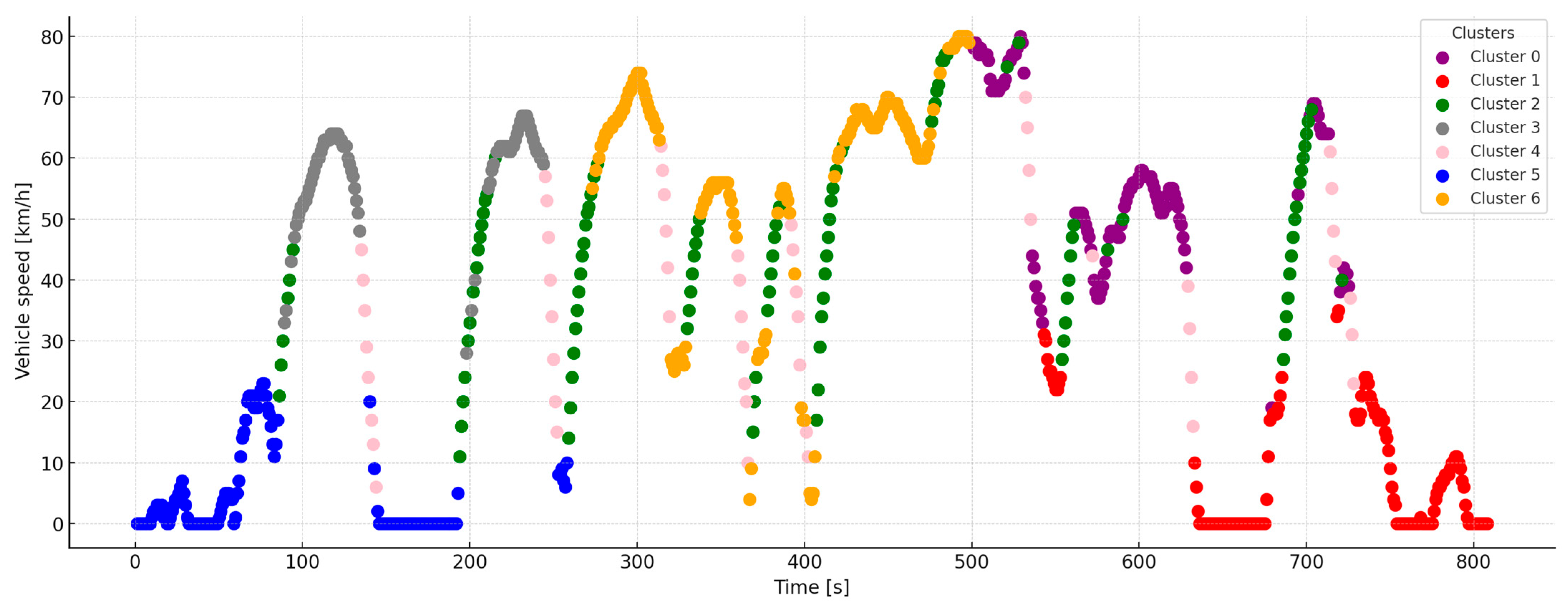

- temporal plots showing vehicle speed over time with cluster assignments,

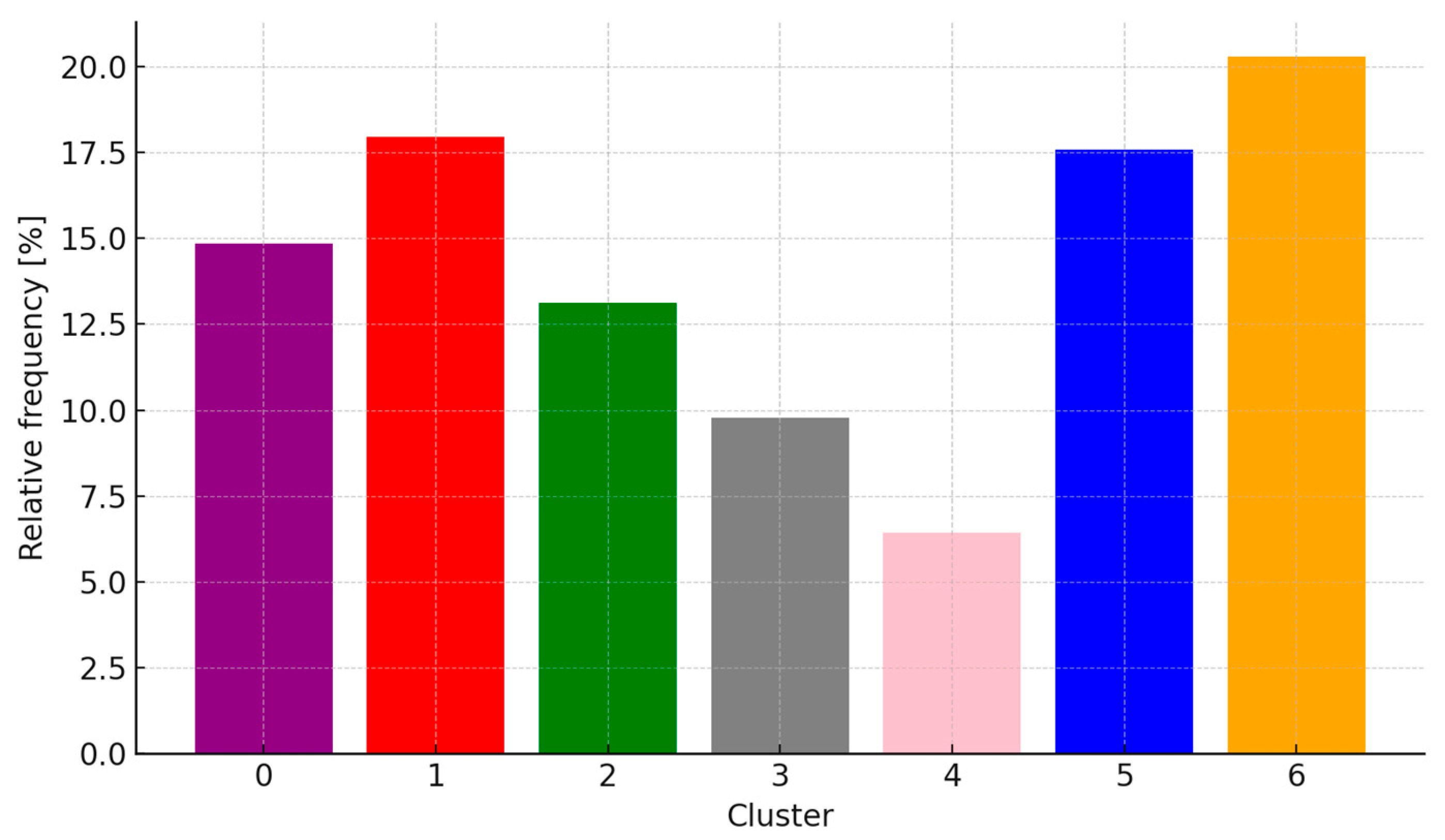

- relative frequencies of occurrence of individual clusters,

- centroid tables summarizing average feature values for each cluster.

2.6. Experimental Protocol and Repeatability

3. Results

3.1. Preparing the Vehicle for Testing

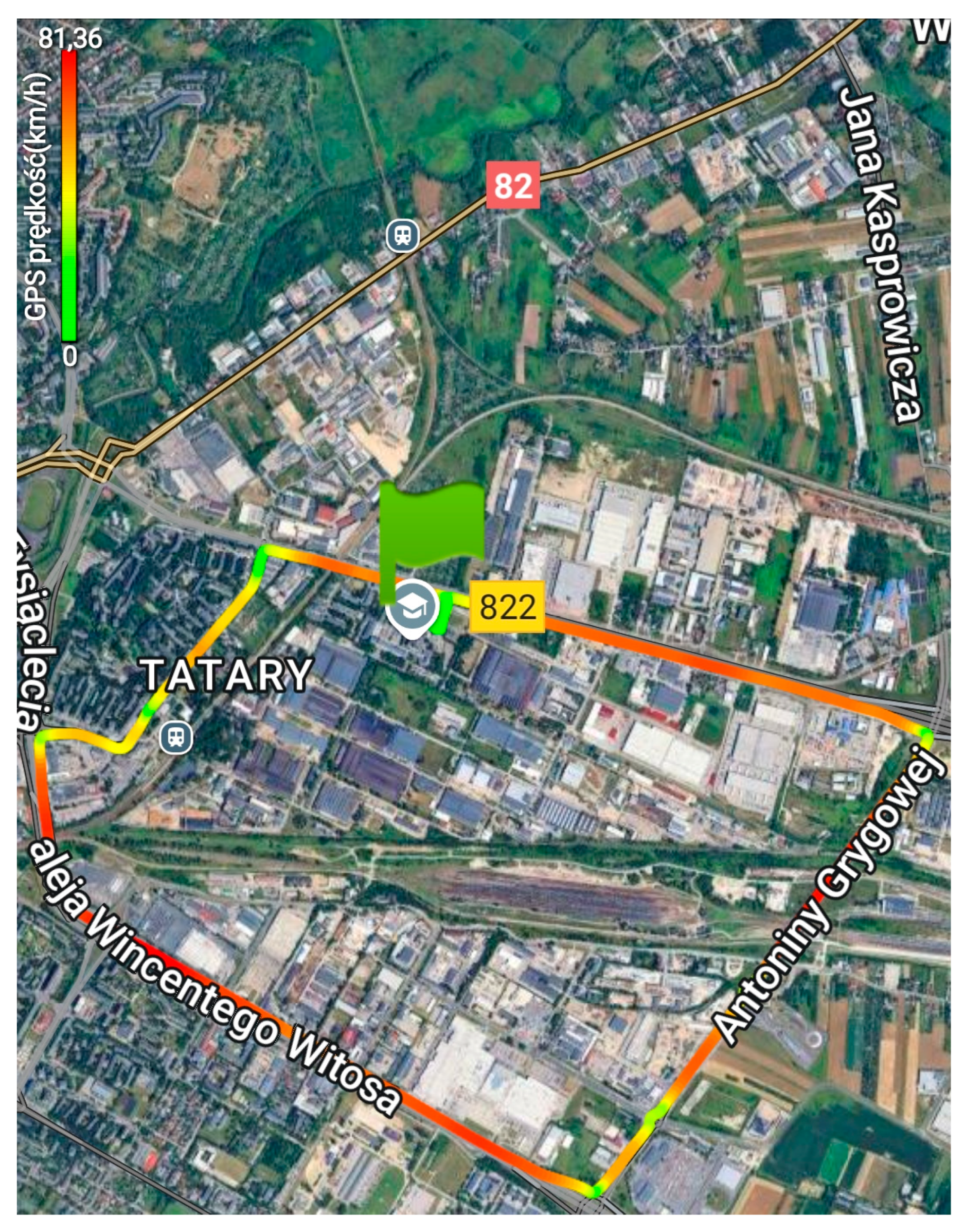

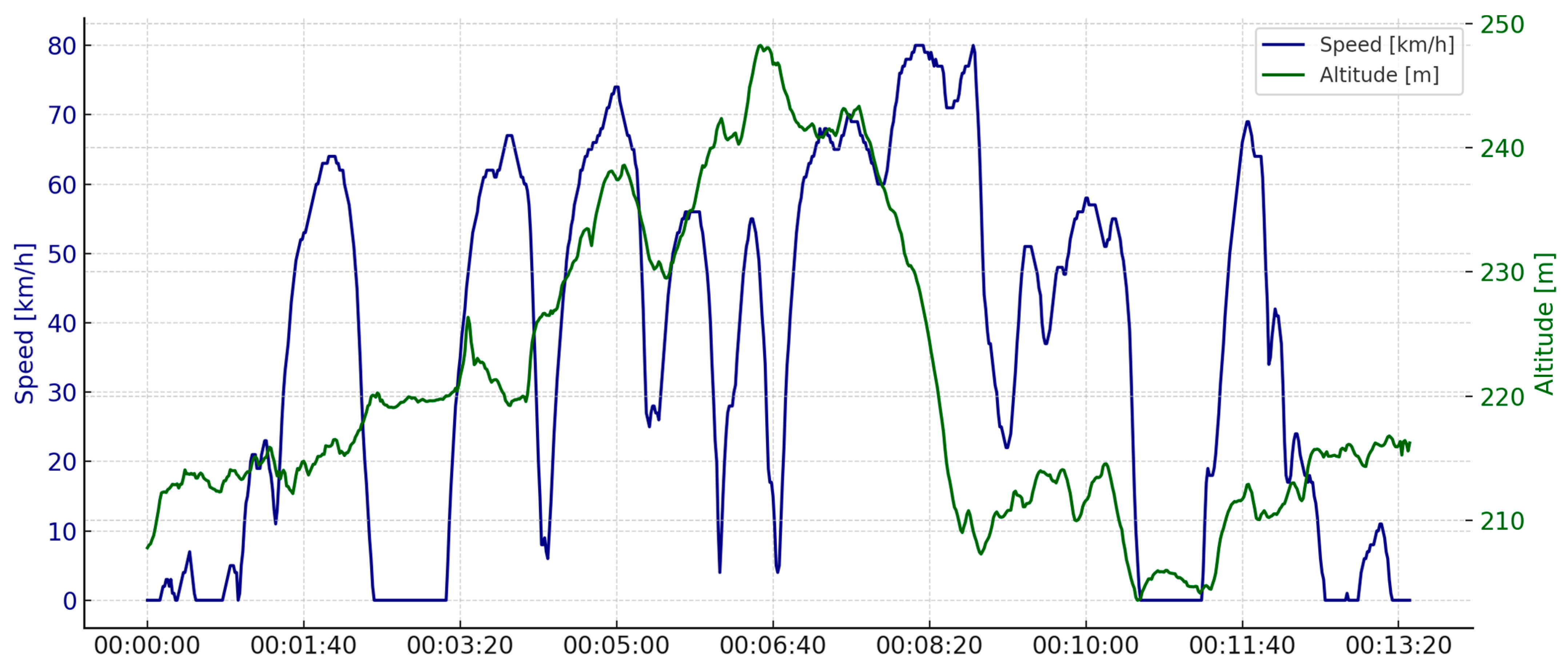

3.2. Road Driving Course in Urban Conditions

3.3. Additional Calculations

3.4. Measurement Data Processing—Unsupervised Clustering

- Hybrid Battery Charge (%)

- Electric motor power at the wheels (kW)

- OBD Speed (km/h)

- Acceleration (m/s2)

- Height above sea level (m)

3.4.1. Unsupervised Clustering in 3-Dimensional Space

- Electric motor power at the wheels (kW)—directly describes the load level and energy flow,

- Acceleration (m/s2)—reflects the dynamics of movement and allows for the distinction between acceleration and deceleration (an indirect indicator of recuperation),

- OBD Speed (km/h)—determines the driving phase (maneuvering, city traffic, smooth driving).

- SOC changes slowly and to a small extent, therefore not contributing much variability to the feature space, but allows for the interpretation of the energy balance (whether the battery is discharging or charging).

- Height above sea level is a contextual parameter, useful for analyzing the impact of topography (e.g., Lublin—a city on hills) but not necessary for the division of clusters describing driving style and drive dynamics.

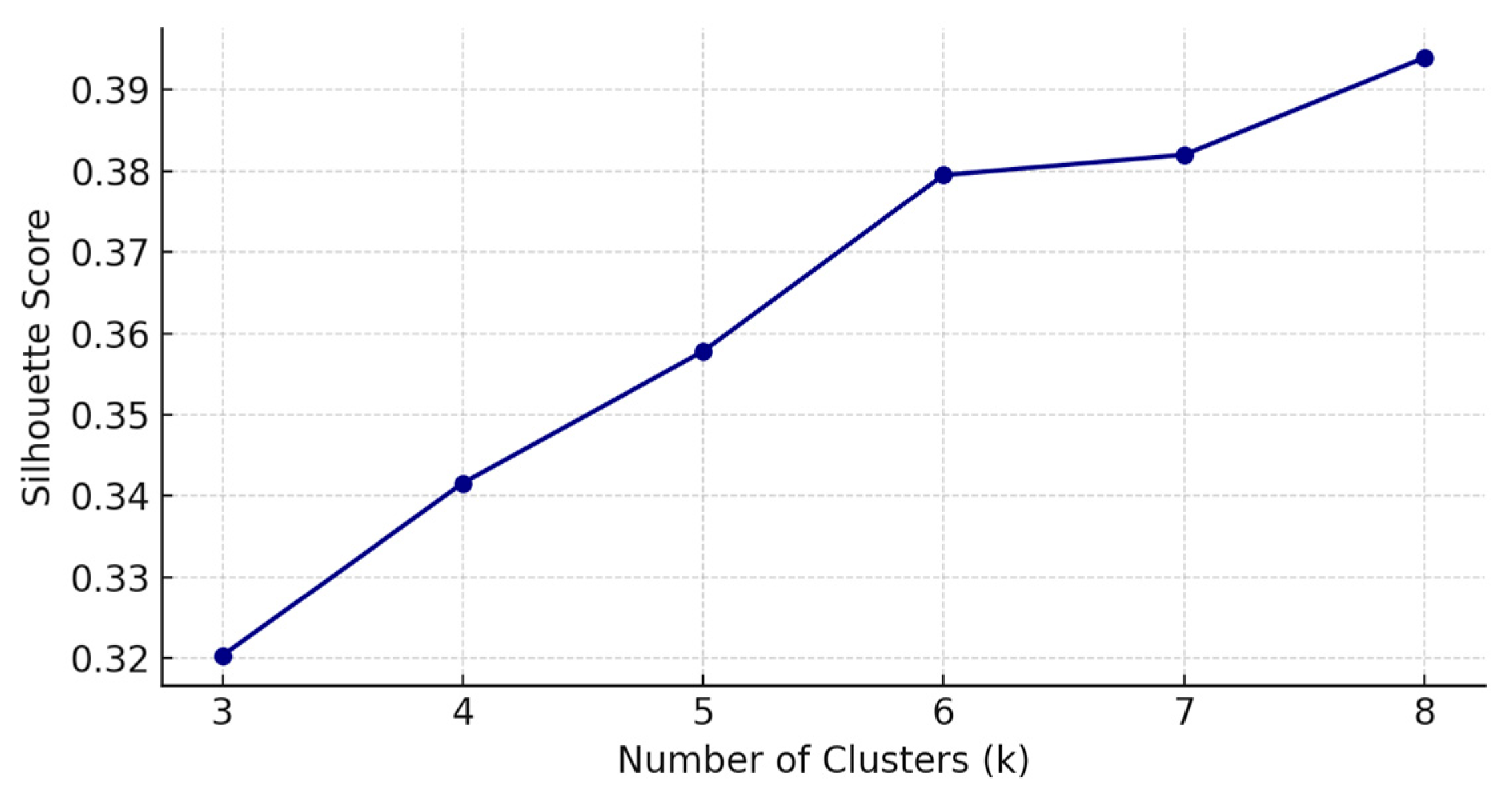

- Silhouette Coefficient (SC)—higher values indicate better cohesion and separation.

- Davies–Bouldin Index (DBI)—lower values reflect better compactness and inter-cluster separation.

- Calinski–Harabasz Index (CHI)—higher values indicate better variance ratio between clusters.

- The average acceleration in this cluster is approximately −1.45 m/s2, which clearly indicates deceleration, i.e., the braking phase.

- At the same time, the electric motor’s power is very low (0.12 kW), meaning it does not provide traction power. In reality, it could operate in generator mode during this phase, but the OBD does not record negative power values.

- The average speed of 34 km/h confirms that the vehicle is not stationary but is decelerating smoothly—typical conditions in which the hybrid system switches to energy recovery mode [26].

- Clusters 0, 2, and 3 are well separated (silhouette ~0.52–0.60).

- Clusters 1 and 4 are more diffuse, partially overlapping neighboring clusters (silhouette ~0.31–0.37).

- Cluster 0 (low speeds)—longer, less frequently interrupted periods (up to 57 s); this corresponds to driving at very low speeds/standing still.

- Cluster 1 (rapid acceleration)—short episodes (~5 s on average), typical of acceleration phases.

- Clusters 2 and 3 (steady driving at higher speeds)—average segments of 5–7 s, sometimes longer (up to 22–26 s).

- Cluster 4 (braking/recuperation)—the shortest episodes, ~4 s, consistent with short phases of intense deceleration.

- Base model: k-Means (k = 5, n_init = 10, random_state = 0)

- Alternative model: k-Means (k = 5, n_init = 5, random_state = 1)

- Goodness of fit: Adjusted Rand Index (ARI)

3.4.2. Unsupervised Clustering in 4-Dimensional Space

- Electric motor power at the wheels (kW)

- OBD Speed (km/h)

- Acceleration (m/s2)

- Height above sea level (m)

- link changes in speed and acceleration to terrain, which is particularly important in hilly Lublin, where topography significantly influences driving energy efficiency;

- identify episodes in which braking results from gravity descent rather than active driver input—such cases indicate potential points of intense recuperation;

- separate acceleration on uphill slopes (higher power consumption at lower speeds) from acceleration on flat terrain, allowing for more precise analysis of electric drive load;

3.4.3. Unsupervised Clustering in 5-Dimensional Space

- Electric motor power at the wheels (kW)

- OBD Speed (km/h)

- Acceleration (m/s2)

- Height above sea level (m)

- Hybrid Battery Charge (%)

- Distinguish between states that appear dynamically similar but have different energy balances, such as acceleration at high and low SOC, which differ in power consumption characteristics and the operation of the energy management system (BMS).

- Identify sections where SOC stabilizes or increases, which may indirectly indicate recuperation activity or drive power reduction to save energy. 3. Detecting changes in the PHEV control strategy—during low SOC phases, the system can further reduce electric power and switch to fuel-efficient modes more frequently, even under similar speed and acceleration conditions.

- Enhance the classification with energy consumption, allowing for analysis not only of vehicle behavior but also of the hybrid system’s efficiency depending on terrain conditions and driving style.

- Separation of acceleration and braking intensity—previously, a single cluster could encompass both light and heavy acceleration; now, for example, a standstill start (low power, positive acceleration) can be distinguished from dynamic acceleration (high power, high acceleration). Similarly, gentle deceleration can be distinguished from deep regenerative braking.

- Detecting transient states—with a larger number of clusters, groups appear corresponding to transition periods between driving phases, such as between acceleration and a steady-state phase. Such clusters are valuable for assessing driving smoothness and electric drive control strategies.

- Identifying the influence of topography—thanks to the altitude parameter, it is possible to separate driving on hills from driving on flat terrain, even at similar speeds and power levels [29]. This allows for analyzing how changes in terrain affect energy consumption and recuperation frequency.

- Distinguishing between SOC-dependent states—the 7-cluster model often distinguishes clusters associated with different battery charge levels, allowing for the study of how the control strategy changes with high vs. low SOC (e.g., power reduction, increased frequency of gentle energy recovery phases).

- Better representation of real-world driving cycles—more clusters enable the creation of a more detailed “driving pattern” that can be used to compare different vehicles, drivers, or routes.

- Enabling the detection of anomalies or unusual drivetrain behavior, such as situations where the vehicle consumes too much energy at low SOC or reaches high power on descents—such outliers can reveal control inefficiencies or component degradation.

- Increased resolution of the energy-dynamic space—clustering with a larger k enables the study of detailed drivetrain operating regimes: from economical driving, through comfortable driving, to dynamic driving, which is important for calibrating driving strategies in future PHEV models.

- Cluster 0 (purple)—14.9%: A typical section of a smooth start from a traffic light, driving in a traffic jam, or slowly rolling through urban zones at 30 km/h.

- Cluster 1 (red)—18.0%: Stopping at a traffic light, in traffic, waiting to turn. Typical “idle travel” in EV mode, where the vehicle waits without increasing power consumption.

- Cluster 2 (green)—13.2%: Corresponds to smooth, steady driving on longer straights, e.g., exit streets, sections between intersections, and city roads at a speed of 50 km/h.

- Cluster 3 (gray)—9.8%: A typical situation when approaching a traffic light, pedestrian crossing, or the end of a line of vehicles. Strongly associated with energy recovery and power recuperation.

- Cluster 4 (pink)—6.4%: Responds to emergency braking situations, e.g., when the driver reacts to changing lights, pedestrian traffic, merging drivers or the sudden stop of a column of cars.

- Cluster 5 (blue)—17.6%: This is dynamic starting—for example, after changing traffic lights, joining traffic, leaving a minor lane, or wanting to join traffic before other vehicles.

- Cluster 6 (orange)—20.3%: This involves driving on sections of high-speed traffic, such as city bypasses, dual carriageways in cities, and sections at 70 or 80 km/h. In real-world EV–PHEV data, such sections often appear between districts.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpreting Clusters in the Context of Energy Efficiency of Electric Driving

4.2. Application of Clustering to Detect Energy Recovery

4.3. The Influence of Topography (Altitude Above Sea Level) on the Cluster Structure

4.4. Comparison of Models with Different Numbers of Clusters

4.5. Valorization of Research Methodology—OBD + KNIME

4.6. Practical Application of the Results

4.7. The Importance of the Obtained Research Results for Sustainable Transport

4.8. Additional Analytical Insights

4.9. Fundamental Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BEV | Battery Electric Vehicle |

| BMS | Battery Management System |

| CSV | Comma-Separated Values |

| ECU | Electronic Control Unit |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| GDI | Gasoline Direct Injection |

| ICE | Internal Combustion Engine |

| KNIME | Konstanz Information Miner (Analytics Platform) |

| OBD | On-Board Diagnostics |

| PHEV | Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| SOC | State of Charge |

| TLA | Three-Letter Acronym |

| WLTC | Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Cycle |

References

- Michailidis, E.T.; Panagiotopoulou, A.; Papadakis, A. A Review of OBD-II-Based Machine Learning Applications for Sustainable, Efficient, Secure, and Safe Vehicle Driving. Sensors 2025, 25, 4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramai, C.; Ramnarine, V.; Ramharack, S.; Bahadoorsingh, S.; Sharma, C. Framework for Building Low-Cost OBD-II Data-Logging Systems for Battery Electric Vehicles. Vehicles 2022, 4, 1209–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szumska, E.M. Regenerative Braking Systems in Electric Vehicles: A Comprehensive Review of Design, Control Strategies, and Efficiency Challenges. Energies 2025, 18, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rykała, M.; Grzelak, M.; Rykała, Ł.; Voicu, D.; Stoica, R.-M. Modeling Vehicle Fuel Consumption Using a Low-Cost OBD-II Interface. Energies 2023, 16, 7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małek, A.; Caban, J.; Dudziak, A.; Marciniak, A.; Vrábel, J. The Concept of Determining Route Signatures in Urban and Extra-Urban Driving Conditions Using Artificial Intelligence Methods. Machines 2023, 11, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małek, A.; Marciniak, A.; Kroczyński, D. Defining Signatures for Intelligent Vehicles with Different Types of Powertrains. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, K.; Laberteaux, K.P. Utility Factor Curves for Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles: Beyond the Standard Assumptions. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielecha, I.; Cieslik, W.; Szwajca, F. Energy Flow and Electric Drive Mode Efficiency Evaluation of Different Generations of Hybrid Vehicles under Diversified Urban Traffic Conditions. Energies 2023, 16, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, M.; Hussain, A.; Musilek, P. Applications of Clustering Methods for Different Aspects of Electric Vehicles. Electronics 2023, 12, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Xing, Q.; Yang, K.; Wu, X.; Li, L. Unsupervised Contrastive Learning for Time Series Data Clustering. Electronics 2025, 14, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szumska, E.M.; Jurecki, R. The Analysis of Energy Recovered during the Braking of an Electric Vehicle in Different Driving Conditions. Energies 2022, 15, 9369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, E.; Zimakowska-Laskowska, M.; Dudziak, A.; Wiśniowski, P.; Laskowski, P.; Stankiewicz, M.; Šnauko, B.; Lech, N.; Gis, M.; Matijošius, J. Analysis of Instantaneous Energy Consumption and Recuperation Based on Measurements from SORT Runs. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropiwnicki, J.; Gawłas, T. Estimation of the Regenerative Braking Process Efficiency in Electric Vehicles. Acta Mech. Autom. 2023, 17, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Y. Research on Electric Vehicle Regenerative Braking System and Energy Recovery. Int. J. Hybrid Inf. Technol. 2016, 9, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Liu, C. Long Downhill Braking and Energy Recovery of Pure Electric Commercial Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enang, W.; Bannister, C. Modelling and Control of Hybrid Electric Vehicles: A Comprehensive Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 74, 1210–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, R.; Montaleza, C.; Maldonado, J.L.; Tostado-Véliz, M.; Jurado, F. Hybrid Electric Vehicles: A Review of Existing Configurations and Thermodynamic Cycles. Thermo 2021, 1, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junthopas, W.; Wongoutong, C. Pre-Determining the Optimal Number of Clusters for k-Means Clustering Using the Parameters Package in R and Distance Metrics. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, E.; Wiśniowski, P.; Gis, M.; Zimakowska-Laskowska, M.; Borucka, A. Vehicle Acceleration and Speed as Factors Determining Energy Consumption in Electric Vehicles. Energies 2024, 17, 4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, M.; Shafi, I.; Mahnoor, M.; Vargas, D.L.R.; Thompson, E.B.; Ashraf, I. A Systematic Literature Review on Identifying Patterns Using Unsupervised Clustering Algorithms: A Data Mining Perspective. Symmetry 2023, 15, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akogul, S.; Erisoglu, M. An Approach for Determining the Number of Clusters in a Model-Based Cluster Analysis. Entropy 2017, 19, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, X. A Fast Method for Estimating the Number of Clusters Based on Score and the Minimum Distance of the Center Point. Information 2020, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Yin, Y.; Liu, P. A New Cluster Validity Index Based on Local Density of Data Points. Axioms 2025, 14, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuza, A.; Jurecki, R.; Szumska, E. Influence of Traffic Conditions on the Energy Consumption of an Electric Vehicle. Commun. —Sci. Lett. Univ. Zilina 2023, 25, B22–B33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gechev, T.; Mruzek, M.; Barta, D. Comparison of Real Driving Cycles and Consumed Braking Power in Suburban Slovakian Driving. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 133, 02003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G.; Naghinajad, S.; Tiano, F.A.; Marino, M. A Survey on Through-the-Road Hybrid Electric Vehicles. Electronics 2020, 9, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Winbush, T.; Newman, A.; Helmers, E. Energy Consumption of Electric Vehicles in Europe. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarout, H.; Zaki, H.; Chahbouni, A.; Ennajih, E.; Louragli, E.M. Optimizing Energy Consumption in Electric Vehicles: A Systematic and Bibliometric Review of Recent Advances. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila-Sacoto, M.; Toledo, M.A.; Hernández-Callejo, L.; González, L.G.; Alvarez Bel, C.; Zorita-Lamadrid, Á.L. Location of Electric Vehicle Charging Stations in Inter-Andean Corridors Considering Road Altitude and Nearby Infrastructure. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KNIME Analytics Platform. Available online: https://www.knime.com/ (accessed on 12 December 2025).

| Cluster | Speed OBD (z) | Power (z) | Acceleration (z) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −1.114 | −0.638 | 0.081 |

| 1 | 0.273 | 1.831 | 0.685 |

| 2 | 0.932 | −0.755 | −0.193 |

| 3 | 0.929 | 0.642 | 0.101 |

| 4 | −0.062 | −0.729 | −1.445 |

| Cluster | Speed OBD (z) | Power (z) | Acceleration (z) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6.45 | 0.55 | 0.081 |

| 1 | 43.43 | 12.17 | 0.685 |

| 2 | 60.99 | ≈0.00 | −0.193 |

| 3 | 60.92 | 6.57 | 0.101 |

| 4 | 34.49 | 0.12 | −1.445 |

| Cluster | Mean Silhouette |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0.603 |

| 1 | 0.306 |

| 2 | 0.561 |

| 3 | 0.519 |

| 4 | 0.368 |

| Cluster | Number of Segments | Average Duration [s] | Maximum Duration [s] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 19 | 15.5 | 57 |

| 1 | 26 | 4.7 | 17 |

| 2 | 20 | 6.8 | 22 |

| 3 | 38 | 4.9 | 26 |

| 4 | 18 | 3.8 | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loman, M.; Šarkan, B.; Małek, A.; Caban, J.; Martyna-Syroka, B.; Piotrowska, K. A Methodological Framework for Inferring Energy-Related Operating States from Limited OBD Data: A Single-Trip Case Study of a PHEV. Vehicles 2025, 7, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040165

Loman M, Šarkan B, Małek A, Caban J, Martyna-Syroka B, Piotrowska K. A Methodological Framework for Inferring Energy-Related Operating States from Limited OBD Data: A Single-Trip Case Study of a PHEV. Vehicles. 2025; 7(4):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040165

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoman, Michal, Branislav Šarkan, Arkadiusz Małek, Jacek Caban, Beata Martyna-Syroka, and Katarzyna Piotrowska. 2025. "A Methodological Framework for Inferring Energy-Related Operating States from Limited OBD Data: A Single-Trip Case Study of a PHEV" Vehicles 7, no. 4: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040165

APA StyleLoman, M., Šarkan, B., Małek, A., Caban, J., Martyna-Syroka, B., & Piotrowska, K. (2025). A Methodological Framework for Inferring Energy-Related Operating States from Limited OBD Data: A Single-Trip Case Study of a PHEV. Vehicles, 7(4), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040165