Development of the Electrical Assistance System for a Modular Attachment Demonstrator Integrated in Lightweight Cycles Used for Urban Parcel Transportation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Attachment Features

- Independent electric assistance: the attachment does not rely on the PEDELECs’ electric assist system;

- Flexibility: the ability to adapt to various types of pedal vehicles through a universal coupling mechanism;

- Variable storage volume: to maximize transport efficiency [12].

2.1. Hardware Characteristics

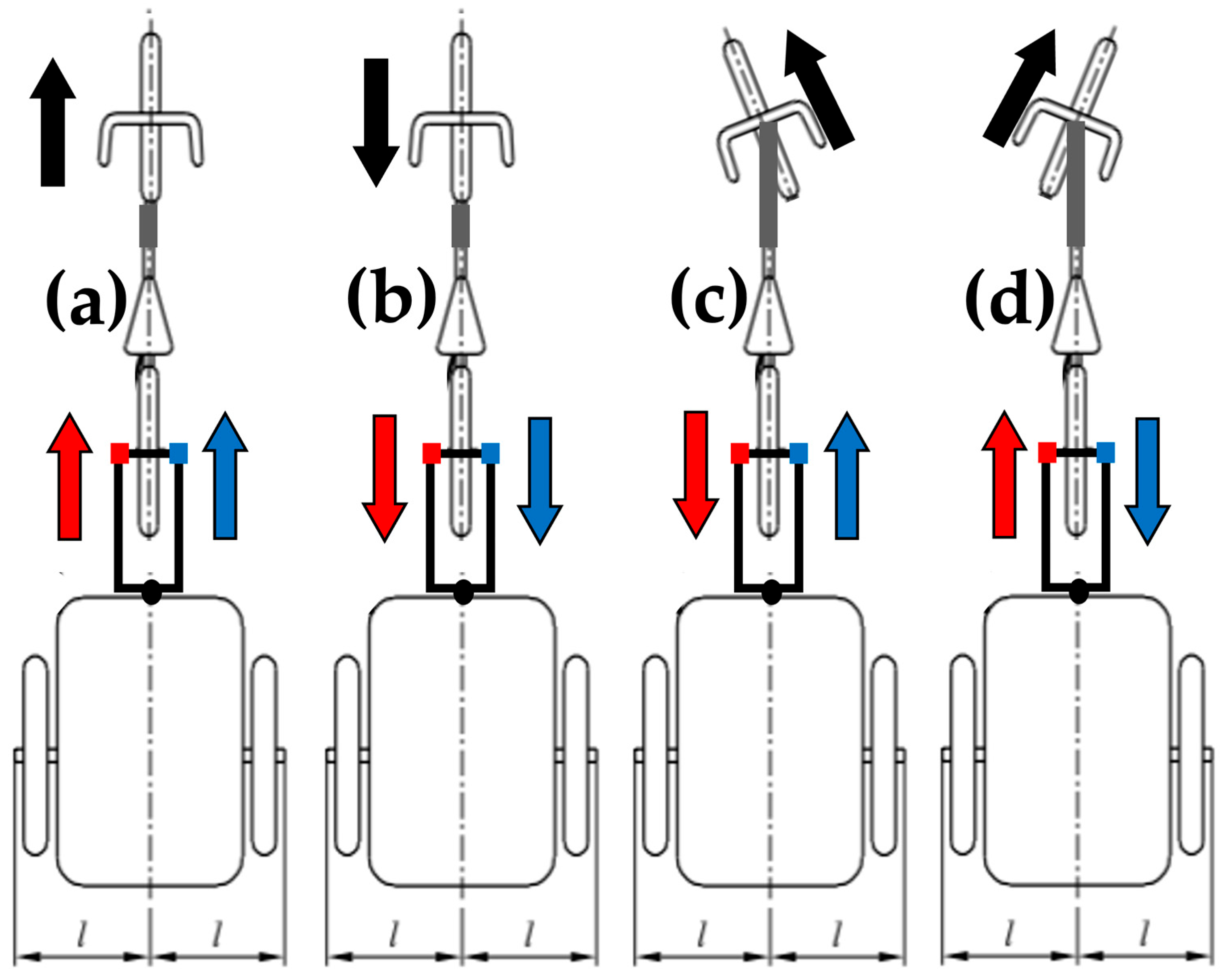

- The attachment must match the speed of the coupled cycle without disrupting natural pedaling dynamics or introducing excessive drag. This ensures a smooth riding experience while maintaining the natural dynamics of pedaling.

- The attachment should be capable of providing additional propulsion when necessary, such as during uphill climbs, rapid accelerations, or when extra assistance is needed due to rider fatigue.

- A dedicated battery pack that supplies power to the system, designed to offer sufficient energy storage for extended use while maintaining a compact and lightweight profile.

- DC motors that provide the necessary propulsion characteristic, carefully selected based on power efficiency, torque output, and speed adaptability.

- Acceleration and torque sensors that monitor rider input and road conditions, allowing real-time adjustments to motor output for a natural and responsive riding experience.

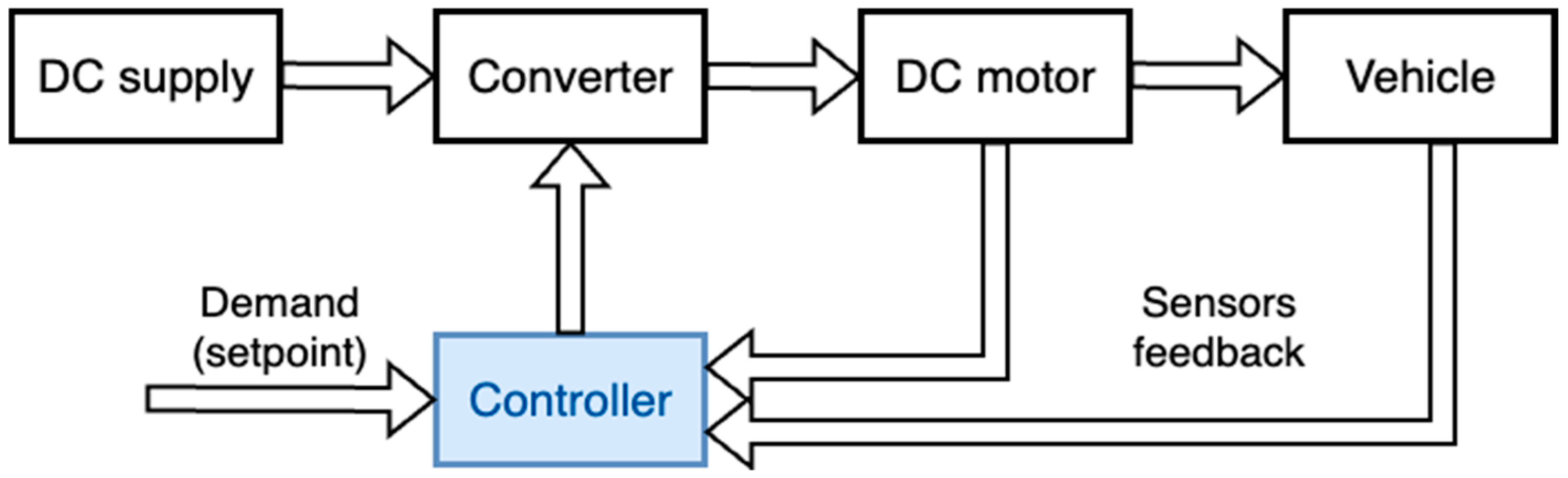

- A static converter that regulates and optimizes the power flow between the battery, motor, and controller, ensuring efficient energy distribution.

- A controller that acts as the system’s intelligence hub, processing data from the sensors and executing the embedded control algorithm to manage speed synchronization, power distribution, and dynamic assistance levels.

2.1.1. Electrical Motors

2.1.2. Battery Systems

2.1.3. Sensors and Controllers

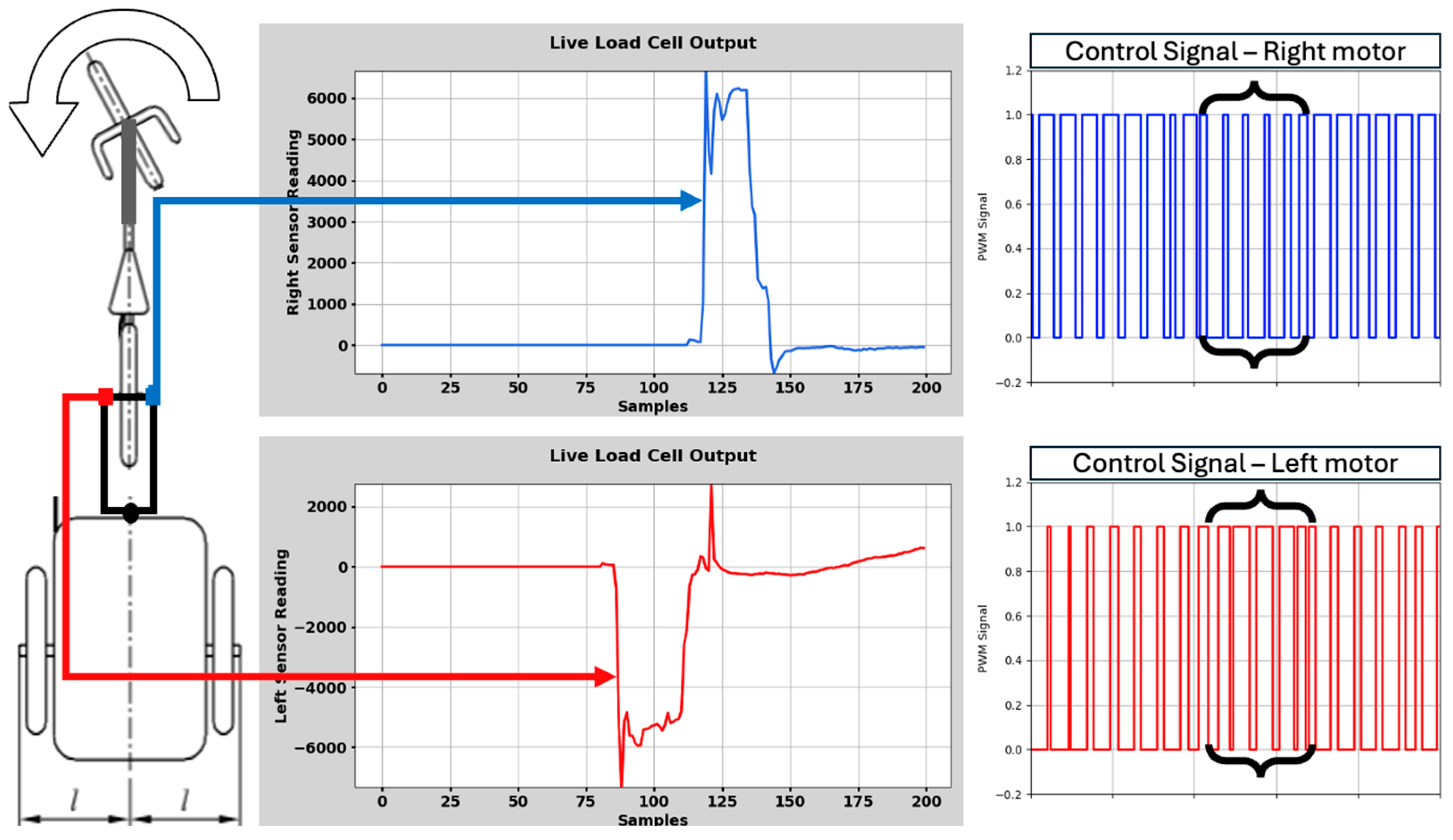

- Managing the data acquisition from the two load cells;

- Sending data over serial through the UART protocol for logging, display and debugging;

- Processing the sensor values and executing the PID control algorithm to generate the throttle signals.

3. Software

3.1. Speed Control Loop

| // Variable definition float Maximum_rate = 15f; // Max change of output per cycle float Previous_Output_value = 0.0f; // Last throttle value // PID Parameters float setpoint = 0.0f; // Desired force = 0 float Kp_low = 0.8f; // Proportional gain low speed region float Kp_high = 0.4f; // Proportional gain near maximum speed float Ki = 0.05f; // Integral gain float Kd = 0.3f; // Derivative gain // Threshold for adaptive control float Motor_Command_threshold = 80.0f; // Integral limits for anti-windup #define INTEGRAL_MAX 200.0f #define INTEGRAL_MIN -200.0f // PID State variables float integral = 0.0f; float previous_error = 0.0f; |

| // PID Controller Function uint32_t PID_Compute(float input) { float error = setpoint-input; // Adaptive Kp float Kp = (Previous_Output_value < Motor_Command_threshold) ? Kp_low : Kp_high; // Derivative calculation float derivative = error-previous_error; previous_error = error; // Output calculation before integral update float output = Kp * error + Ki * integral + Kd * derivative; // Rate limiting if (output > Previous_Output_value + Maximum_rate) output = Previous_Output_value + Maximum_rate; if (output < Previous_Output_value - Maximum_rate) output = Previous_Output_value - Maximum_rate; // Output saturation if (output < 0) output = 0; if (output > 100) output = 100; if (!((output <= 0 && error < 0) || (output >= 100 && error > 0))) { integral += error; // Clamp integral to prevent excessive accumulation if (integral > INTEGRAL_MAX) integral = INTEGRAL_MAX; if (integral < INTEGRAL_MIN) integral = INTEGRAL_MIN; } Previous_Output_value = output; return (uint32_t)output; } |

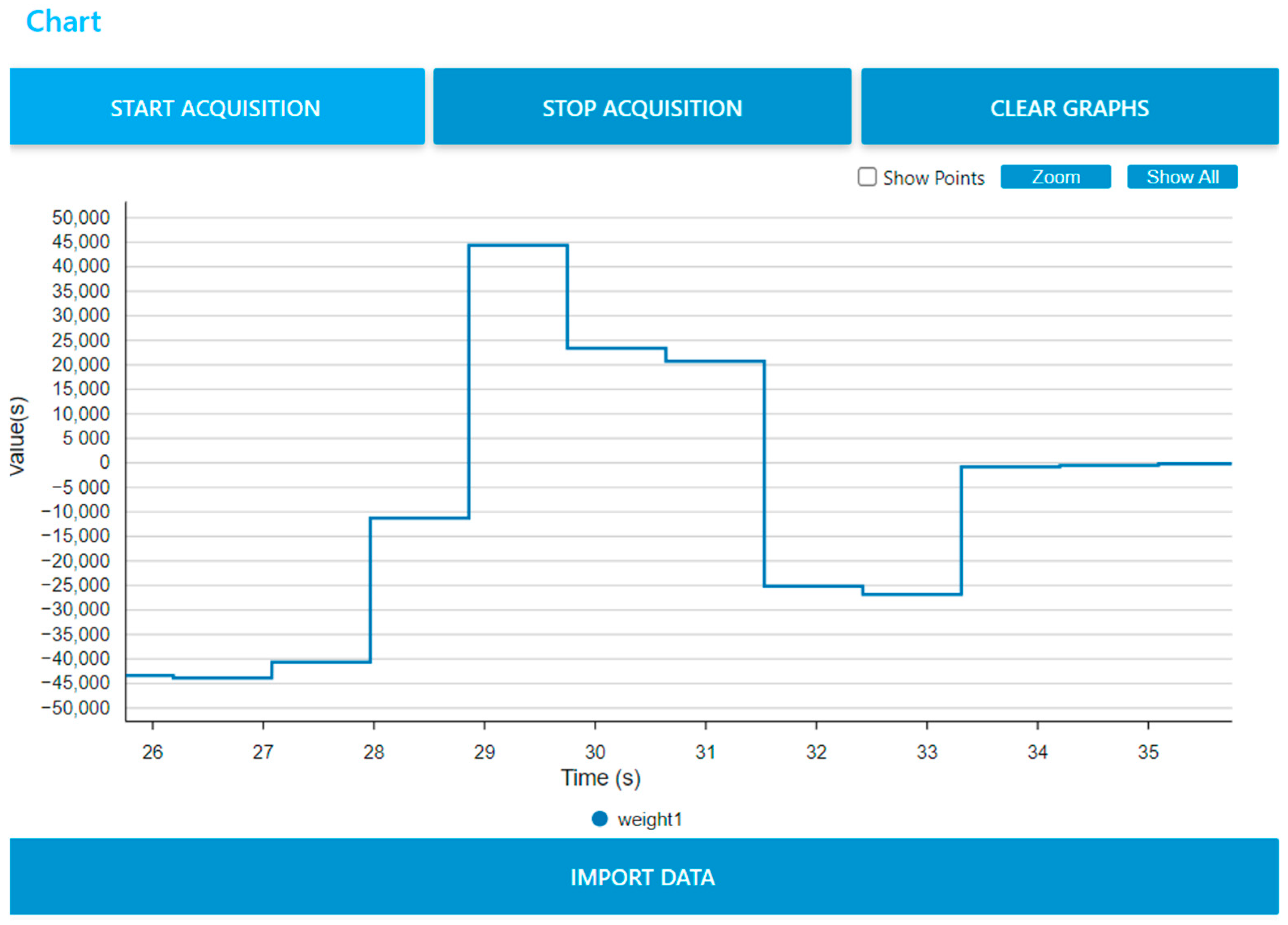

3.2. Data Visualization in Python

| SERIAL_PORT = "COM8" BAUD_RATE = 115200 ser = serial.Serial(SERIAL_PORT, BAUD_RATE, timeout=1) BUFFER_SIZE = 100 data = deque([0] * BUFFER_SIZE, maxlen=BUFFER_SIZE) plt.ion() fig, ax = plt.subplots() line, = ax.plot(data) while True: try: line_data = ser.readline().decode(errors='ignore').strip() if "Load1" in line_data: data.append(line_data) line.set_ydata(data) ax.set_ylim(min(data)-10, max(data)+10) except ValueError: print(f"Skipping: {line_data}") ser.close() plt.ioff() plt.show() |

4. Serial Communication

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BLDC | Brushless Direct Current (Motor) |

| BES | Battery Energy Storage |

| DC | Direct Current |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative (Controller) |

| PEDELEC | Pedal Electric Cycle |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| USB | Universal Serial Bus |

| UART | Universal Asynchronous Receiver-Transmitter |

| STM32 | STMicroelectronics 32-bit Microcontroller |

| IDE | Integrated Development Environment |

| COM Port | Communication Port |

| RPM | Revolutions Per Minute |

| HSI | High-Speed Internal (Oscillator) |

| PLL | Phase-Locked Loop |

| SYSCLK | System Clock |

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats |

References

- European Commission. Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy-Putting European Transport on Track for the Future. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0789 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Dornoff, J.; Mock, P.; Baldino, C.; Bieker, G.; Díaz, S.; Miller, J.; Sen, A.; Tietge, U.; Wappelhorst, S. Fit for 55: A Review and Evaluation of the European Commission Proposal for Amending the CO2 Targets for New Cars and Vans. 2021. Available online: https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/fit-for-55-review-eu-sept21.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- CityChangerCargoBike Project Consortium. CityChangerCargoBike: Increasing the Take-Up and Scale-Up of Cargo Bikes in Urban Areas; Grant Agreement 769086; H2020 Programme; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018–2022. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/769086 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Urban Logistics as an on Demand Service Project Consortium. Urban Logistics as an on Demand Service: Sustainable System Innovations in Urban Logistics; Grant Agreement 861833; H2020 Programme; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020–2024. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/861833 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Dorsey, B. Sustainable Intermediate Transport in West Africa: Quality Before Quantity. World Transp. Policy Pract. 2008, 14, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lenz, B.; Riehle, E. Bikes for Urban Freight? Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2013, 2379, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schier, M.; Offermann, B.; Weigl, J.D.; Maag, T.; Mayer, B.; Rudolph, C. Innovative two wheeler technologies for future mobility concepts. In Proceedings of the 2016 11th International Conference on Ecological Vehicles and Renewable Energies, EVER 2016, Monte Carlo, Monaco, 6–8 April 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyesiku, O.O.; Akinyemi, O.O.; Giwa, S.O.; Lawal, N.S.; Adetifa, B.O. Evaluation of Rural Transportation Technology: A Case Study of Bicycle and Motorcycle Trailers. J. Kejuruter. 2019, 31, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NÜWIEL. NÜWIEL eTrailer. Available online: https://www.nuwiel.com (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Aevon. CARGO 10. Available online: https://aevon-trailers.com/en/homepage/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Carla Cargo. e-Carla Cargo. Available online: https://www.carlacargo.de/products/ecarla (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Teodorascu, V.; Burnete, N.; Kocsis, L.B.; Duma, I.; Molea, A.; Sechel, I.C. Design and validation of an electrically assisted modular attachment demonstrator for lightweight cycles. J. Eng. Sci. Innov. 2024, 9, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley. Travoy® Cargo Trailer. Available online: https://burley.com/en-in/products/travoy (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Burley. FlatbedTM Cargo Trailer. Available online: https://burley.com/en-in/products/flatbed (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- TAXXI. LOAD Heavy—Trailer for Heavy Loads and Luggage. Available online: https://mytaxxi.de/en/products/taxxi-load-heavy (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Wike. Aluminum Landscaping & Utility Cargo Bike Trailer. Available online: https://wikeinc.com/en-ca/products/cargo-landscaping-trailer (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- ASTM F2917-12; Standard Specification for Bicycle Trailer Cycles Designed for Human Passengers. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012. [CrossRef]

- ASTM F1975-09; Standard Specification for Nonpowered Bicycle Trailers Designed for Human Passengers. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015. [CrossRef]

- BS EN 15918:2011; Cycles—Cycle Trailer—Safety Requirements and Test Methods. SGS: Baar, Switzerland, 2011. Available online: https://knowledge.bsigroup.com/products/cycles-cycle-trailers-safety-requirements-and-test-methods (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Gov. of Romania. DECISION No. 1,391 of October 4, 2006, for the Approval of the Regulation for the Implementation of Government Emergency Ordinance No. 195/2002 Regarding Traffic on Public Roads. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/164781 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Muetze, A.; Tan, Y.C. Electric bicycles—A performance evaluation. IEEE Ind. Appl. Mag. 2007, 13, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starschich, E.; Muetze, A. Comparison of the performances of different geared brushless-DC motor drives for electric bicycles. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Electric Machines and Drives Conference, IEMDC 2007, Antalya, Turkey, 3–5 May 2007; Volume 1, pp. 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, A.; Ishak, D. Finite element modeling and analysis of external rotor brushless DC motor for electric bicycle. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Student Conference on Research and Development—SCOReD 2009, Serdang, Malaysia, 16–18 November 2009; pp. 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contò, C.; Bianchi, N. E-Bike Motor Drive: A Review of Configurations and Capabilities. Energies 2023, 16, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafang Electric (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. BFSWXK36V250W255R Brushless Hub Motor Specifications; Bafang Electric: Suzhou, China. Available online: https://www.bafang-e.com/en/oem-area/components/motor/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Arsadiando, W.; Sutikno, T.; Widodo, N.S.; Santosa, B. Comprehensive Analysis of Current Research Trends in Battery Technologies as Electricity Storage Devices for Electric Bikes: A Review. JEEE 2022, 15, 138–143. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376810202 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Weinert, J.X.; Burke, A.F.; Wei, X. Lead-acid and lithium-ion batteries for the Chinese electric bike market and implications on future technology advancement. J. Power Sources 2007, 172, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilo, L.; Segura-Velandia, D.; Lugo, H.; Conway, P.P.; West, A.A. Electric bicycles, next generation low carbon transport systems: A survey. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 10, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Such, M.C.; Hill, C. Battery energy storage and wind energy integrated into the smart grid. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies, ISGT 2012, Washington, DC, USA, 16–20 January 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, J.M.; Ramana, P.V.; Mehta, J.R. Performance assessment of valve regulated lead acid battery for E–bike in field test. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 2058–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, E.; Cherry, C. E-bikes in the Mainstream: Reviewing a Decade of Research. Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.A.; Hoque, M.M.; Mohamed, A.; Ayob, A. Review of energy storage systems for electric vehicle applications: Issues and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 69, 771–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, N.B.; Lim, O. A review of history, development, design and research of electric bicycles. Appl. Energy 2020, 260, 114323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogel, D. Strategic Sustainability: A Natural Environmental Lens on Organizations and Management; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; pp. 1–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdsup, B.; Fuengwarodsakul, N.H. Performance and cost comparison of reluctance motors used for electric bicycles. Electr. Eng. 2017, 99, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, X. Research on battery to ride comfort of electric bicycle based on multi-body dynamics theory. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Automation and Logistics, ICAL 2009, Shenyang, China, 5–7 August 2009; pp. 1722–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YJ Power Group Limited (Shenzhen), Shenzhen, China. Model YJ1281005 Electric Bicycle Battery (36V, 16Ah, 576Wh). Available online: https://www.jetechbattery.com/products (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Khanke, P.K.; Jain, S.D. Comparative analysis of speed control of BLDC motor using PI, simple FLC and Fuzzy-PI controller. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Energy Systems and Applications, ICESA 2015, Pune, India, 30 October–1 November 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About the Smart Ebike Project—E Mountain Bikes. Available online: https://emountainbikekings.com/events/smart-ebikes/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Robert Bosch GmbH. Bosch eBike Systems. Available online: https://www.bosch-ebike.com/en/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Zahid, A. Vanhawks Valour | First Ever Connected Carbon Fibre Bicycle. Available online: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1931822269/vanhawks-valour-first-ever-connected-carbon-fibre (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Kiefer, C.; Behrendt, F. Smart e-bike monitoring system: Real-time open source and open hardware GPS assistance and sensor data for electrically assisted bicycles. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 10, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjing Lishui Electronics Research Institute Co., Ltd. LSW943-92F Brushless Motor Controller for Electric Bicycles; Lishui Controller: Nanjing, China. Available online: https://www.lsdzs.com/ls_product/product.php?lang=en&class2=19 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Tamilmani, T.; Tanushri, K. E-Bike Speed Control System. JETIR 2023, 10, b864–b871. Available online: https://www.jetir.org/view?paper=JETIR2312206 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Thakare, C.S. A Review Paper on-E-Bike Motor Speed Controller. Int. J. Adv. Res. Sci. Commun. Technol. IJARSCT 2023, 3, 314–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.L.; Chen, E.P.; Chen, Y.C.; Liu, M.K. Advanced driving/braking control design for electric bikes. In Proceedings of the 2017 12th IEEE Conference on Industrial Electronics and Applications, ICIEA 2017, Siem Reap, Cambodia, 18–20 June 2017; pp. 1254–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, M.V.S. Model based design to control DC motor for pedal assist bicycle. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Communication Technologies, ICECCT 2015, Coimbatore, India, 5–7 March 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, S.; Jayasree, P.R.; Ravi, S.; Prasad, R.; Vijayakumar, V. Economically viable conversion of a pedal powered bicycle into an electric bike. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems, ICEMS 2013, Busan, Republic of Korea, 26–29 October 2013; pp. 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruque, K.F.I.; Nawshin, N.; Bhuiyan, M.F.; Uddin, M.R.; Hasan, M.; Salim, K.M. Design and Development of BLDC Controller and Its Implementation on E-Bike. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Recent Innovations in Electrical, Electronics and Communication Engineering, ICRIEECE 2018, Bhubaneswar, India, 27–28 July 2018; pp. 1461–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thejasree, G.; Maniyeri, R.; Kulkami, P. Modeling and Simulation of a Pedelec. In Proceedings of the 2019 Innovations in Power and Advanced Computing Technologies, i-PACT 2019, Vellore, India, 22–23 March 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangdong South China Sea Electronic Measuring Technology Co., Ltd.: Guangdong, China. 3134-Micro Load Cell (0–20 kg)-CZL635. Available online: http://www.mantech.co.za/datasheets/products/CZL635-EIE.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Avia Semiconductor. HX711: 24-Bit Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) for Weigh Scales. HX711 Datasheet (Rev. English). Available online: https://cdn.sparkfun.com/datasheets/Sensors/ForceFlex/hx711_english.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

| Manufacturer | Carla Cargo (Herbolzheim, Germany) | Aveon (Lormont, France) | NÜWIEL (Hamburg, Germany) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | eCARLA | e-STD100 | CARGO100 | NÜWIEL |

| Electric motor power [W] | 250 | ≤1000 peak | ≤1000 peak | 250 |

| Battery capacity [Wh] | 720 | optional | NR | 600–800 |

| Maximum allowed payload [kg] | 200 | 45 | 100 | 150 |

| Cargo volume [m3] | 1.5 | 0.16 | NR | 1 |

| Top speed [km/h] | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| Rated Voltage [V] | Rated Power [W] | Rated Current [A] | Efficiency [%] | Weight [kg] | Freewheel Speed [km/h] | Torque [Nm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | 250 | 7 | ≥78% | ~3 kg | 20–30 | 20–35 |

| Nominal Voltage [V] | Rated Capacity [Ah] | Rated Energy [Wh] | Weight [kg] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | 16 | 576 | 3.11 |

| Rated Voltage [V] | Maximum Current [A] | Rated Current [A] | Low Voltage Protection [V] | Throttle Adjustment Voltage [V] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | 14 | 7 | 31.5 | 1.2–4.4 |

| Capacity [kg] | Precision [%] | Rated Output [mv/V] | Excitation Voltage [V] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 0.05 | 1.0 ± 0.15 mv/V | 5 |

| Power Supply Voltage [V] | Analog Supply Current [µA] | Digital Supply Current [µA] | Output Settling Time [ms] | Reference Bypass [V] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.6–5.5 | 1400 | 100 | 400 | 1.25 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

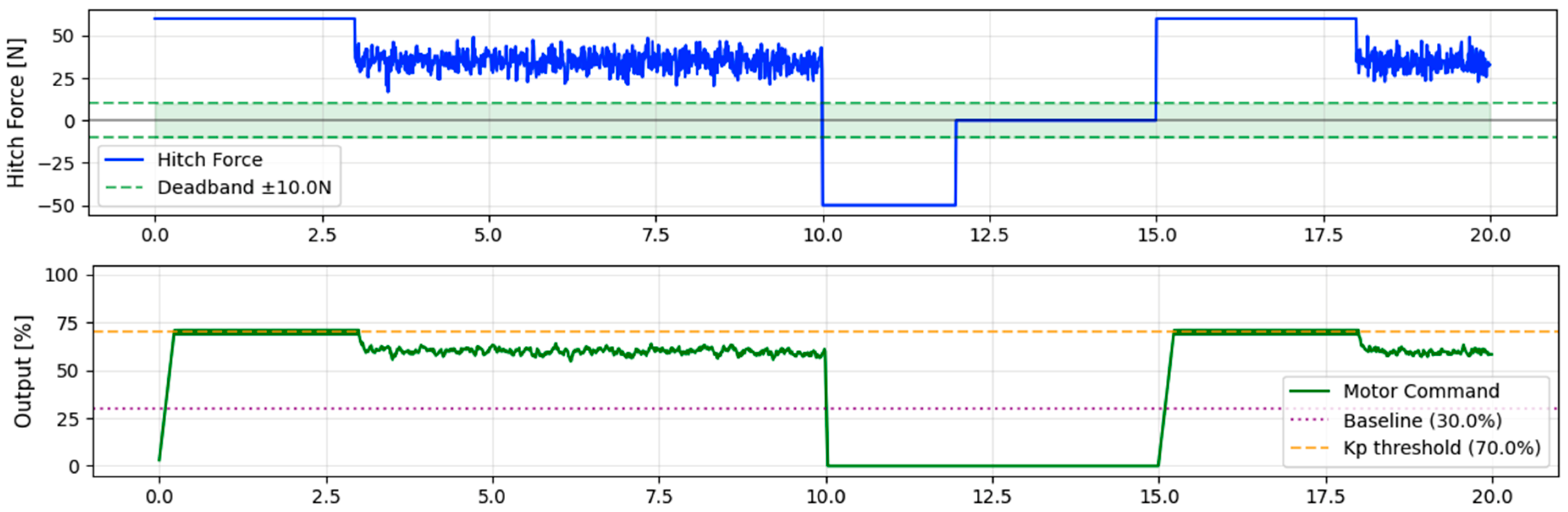

| Time in Deadband | 3.00 s |

| Settling Time | 3.49 s |

| Integral of Absolute Error | 703.24 |

| Integral of Squared Error | 33,187.25 |

| Integral of Time-weighted Absolute Error | 6459.90 |

| Rise Time | 0.39 s |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Internal High-Speed Oscillator (HSI) | 8 MHz |

| Input to PLL: HSI/2 | 4 MHz |

| PLL Multiplier | ×12 |

| PLL Output | 4 MHz × 12 = 48 MHz |

| System Clock (SYSCLK) | PLLCLK |

| Frequency | 48 MHz |

| AHB Prescaler | HCLK = 48 MHz |

| APB1 Prescaler | PCLK1 = 48 MHz |

| USART Clock: Derived from PCLK1 | 48 MHz |

| UART baud rate | 115,200 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teodorascu, V.; Burnete, N.; Kocsis, L.B.; Duma, I.; Burnete, N.V.; Molea, A.; Sechel, I.C. Development of the Electrical Assistance System for a Modular Attachment Demonstrator Integrated in Lightweight Cycles Used for Urban Parcel Transportation. Vehicles 2025, 7, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040164

Teodorascu V, Burnete N, Kocsis LB, Duma I, Burnete NV, Molea A, Sechel IC. Development of the Electrical Assistance System for a Modular Attachment Demonstrator Integrated in Lightweight Cycles Used for Urban Parcel Transportation. Vehicles. 2025; 7(4):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040164

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeodorascu, Vlad, Nicolae Burnete, Levente Botond Kocsis, Irina Duma, Nicolae Vlad Burnete, Andreia Molea, and Ioana Cristina Sechel. 2025. "Development of the Electrical Assistance System for a Modular Attachment Demonstrator Integrated in Lightweight Cycles Used for Urban Parcel Transportation" Vehicles 7, no. 4: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040164

APA StyleTeodorascu, V., Burnete, N., Kocsis, L. B., Duma, I., Burnete, N. V., Molea, A., & Sechel, I. C. (2025). Development of the Electrical Assistance System for a Modular Attachment Demonstrator Integrated in Lightweight Cycles Used for Urban Parcel Transportation. Vehicles, 7(4), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/vehicles7040164