Abstract

This paper presents a detailed experimental evaluation of a newly developed diesel fuel additive, specifically formulated to enhance the energy efficiency and emission characteristics of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, with particular emphasis on its applicability to aging vehicle fleets. Diesel engines are known for producing significant amounts of harmful emissions, necessitating the development of effective mitigation strategies. One such approach involves the use of fuel additives. The additive under investigation is a proprietary formulation containing 1-(N,N-bis(2-ethylhexyl)aminomethyl)-1,2,4-triazole and other compounds. To the best of our knowledge, this specific additive composition has not yet been tested or reported in the existing scientific literature. To evaluate the real-world contribution of such additives, a comprehensive set of controlled measurements was conducted in a certified chassis dynamometer laboratory, including an exhaust gas analyser and supplementary diagnostic equipment. The testing protocol comprised repeated measurement cycles under identical driving conditions, both without and with the additive. Exhaust gas concentrations of CO2, CO, and NOx were continuously monitored. Simultaneously, fuel consumption and engine performance were tracked over a cumulative driving distance of 2000 km. The results indicate measurable improvements across all monitored domains. CO2 emissions decreased by 4.57%, CO by 14.29%, and NOx by 3.12%. Fuel consumption was reduced by 4.79%, while engine responsiveness and power delivery showed moderate but consistent enhancements. These improvements are attributed to more complete combustion and an increased cetane number enabled by the additive’s chemical structure. The findings support the adoption of advanced additive technologies as part of transitional strategies towards low-emission transportation systems.

1. Introduction

The current trend of a constant increase in road vehicles in traffic results in an increase in emission generation. In recent years, we have seen a steady increase in interest in improving diesel performance and durability due to the increasing reliability and efficiency of engines [1,2,3]. Each combustion process is a source of different emissions. Emissions released into the environment pollute the atmosphere and cause various problems such as global warming, acid rain, smog, respiratory and other health hazards [4,5,6,7]. The main pollutants contributed by engines are carbon monoxide CO emissions, unburned hydrocarbons HC, nitrogen oxides NOx and other particulate emissions. In addition, all systems burning hydrocarbon fuels emit carbon dioxide CO2 in large quantities, which has a negative effect on increasing the greenhouse effect [8,9,10,11]. The EU aims to achieve a 90% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from transport by 2050 compared to 1990. This is part of its efforts to reduce emissions and achieve climate neutrality as part of the European Green Deal. Transport is the only sector where emissions have increased by 33.5% over the past three decades. According to current projections, transport emissions will decrease by only 22% by 2050, which is still far from the set ambitions [12,13].

Currently, various means are used to reduce emissions, which are more or less effective. These are, for example, particulate filters, which have been in use since 2000 and remove particulate emissions from exhaust gases of diesel and gasoline engines through physical filtration. Furthermore, it can be a DOC (diesel oxidation catalyst), whose main function is the oxidation of HC and CO [14,15,16]. In addition, they play an important role in reducing the mass of particulate matter by oxidizing some hydrocarbons that are adsorbed on carbon particles. DOCs can also be used in conjunction with SCR (Selective Catalytic Reduction) catalysts to reduce NOx. An active emission reduction system used in cars is the EGR (exhaust gas recirculation) system, which also aims to reduce NOx emissions by recirculating exhaust gases back into the combustion chamber and mixing with fresh air on the intake stroke [17,18,19].

However, this technology does not have a high enough efficiency to meet emission standards, and as a result of lowering the temperature in the combustion chamber, the technology increases CO and HC emissions [20,21].

One of the most common ways to achieve these goals is through the use of diesel additives. According to authors [22], using additives to improve fuel quality can improve engine efficiency, chemical composition and reduce pollutant emissions and improve the overall durability without changing the internal combustion engine structure or adding additional units. With older engines, any structural and technical intervention is unthinkable, as it would be extremely economically demanding, because each engine was designed for a certain period of time. If we take into account only all approval processes, it is economically unprofitable, and this can be solved in most cases with the help of an additive, while otherwise all cars would have to be withdrawn from circulation because they do not have approved technical capability, as a result of which it would be necessary to approve new certificates. Such a process would not only be economically costly but also time-consuming. Fuel additives have the task of increasing the cetane number of the fuel and overall increasing the performance parameters, improving the engine operation and reducing emission parameters and consumption [23,24]. Other tasks of additives include increasing the lubricity and freezing point of diesel fuel, cleaning the fuel system and protecting against corrosion [25,26]. Diesel additives are divided into winter and summer. Winter additives are recommended to be used only in winter to increase the filterability of diesel in cold periods, when diesel can start to solidify or form paraffin. Summer additives work actively in the field of lubrication of injection pumps and injectors, remove deposits in the fuel system and help clean oxidation catalysts with the lambda probe and particulate filters [27,28,29].

However, before deciding to use any additive, it is crucial to understand its effects and verify its true effectiveness through tests and research. These ingredients bring an effective reduction in harmful substances; although these benefits are known, there is quite a bit of distrust and skepticism, because few results or almost no credible results are published in this area. Therefore, it is necessary to find out their real contribution to the improvement of fuels; it is necessary to verify whether there is a real benefit or if it is just a commercial matter for the general motoring public [30,31,32].

This topic is currently of great importance, as specifically in Slovakia and also in other countries of Europe, the average age of vehicles used by people is 16–20 years, so despite their age, there are still many older vehicles with lower emission standards on the road and these vehicles and specifically diesel-engine vehicles, have higher emission values. The related field of reducing emissions is currently very much discussed and a suitable form of reducing or eliminating them is constantly being sought. It is important to note that until the transition is complete to other alternative fuels with lower or zero emissions, it is necessary to reduce the emission values of the still many older vehicles with lower emission standards to an acceptable level with the lowest possible emissions [33,34].

The issue of reducing emissions is currently of great importance, also from the point of view of the European Commission’s “Green Deal” plan for the green transformation of the European Union’s economy for the sake of a sustainable future and effective reduction in emissions until the transition to other alternative sources of energy [35].

The aim of the research was to evaluate the effect of a specific fuel additive with content of 1-(N, N-bis(2-ethylhexyl) aminomethyl); 1,2,4-triazole; amides and other compounds on various parameters of the vehicle, such as emissions, energy and power efficiency in the conditions of the laboratory of bioenergy resources of the Agrobiotech research center at the Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristic of Used Material

The fourth-generation Volkswagen (Wolfsurg, Germany) Golf from 2000 was used for this research. An older vehicle with higher mileage was deliberately selected to evaluate the effect of the additive even on such types of vehicles, which are still relatively common on roads today. The vehicle is powered by a 1.9 dm3 diesel engine with direct injection and turbocharging. At the time of measurement, the odometer reading was 225,325 km. Relevant technical specifications of the vehicle are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Technical parameters of the examined vehicle.

For all measurements, diesel fuel was used. According to the manufacturer, this fuel meets the requirements of the STN 590 standard (Slovenská technická norma 590) [36]. The parameters of the diesel fuel are shown in Table 2, and the characteristics of the tested diesel additive are presented in Table 3. The additive was mixed in the prescribed ratio of 70 mL per 100 L of fuel. Table 2 presents the basic physical and chemical properties of diesel fuel labeled Energy Diesel 55, from the Real-K (Komárno, Slovakia) gas station. These parameters are important for assessing the quality of the fuel, its combustion properties, suitability for modern diesel engines, and for comparison with legislative requirements.

Table 2.

Parameters of used diesel fuel [15].

Table 3.

Parameters of tested additive.

According to the listed parameters, Energy Diesel 55 fuel meets all the requirements of the EN 590 standard for diesel fuel and also exhibits several above-standard values, for example, a high cetane number indicates good ignition ability, quieter operation and lower emission generation during cold start. It is also possible to see a good calorific value, which indicates good energy quality of the fuel. As for the proportion of bio components, the value of 7% corresponds to the maximum permitted limit in the EN 590 standard, while the presence of bio components affects the lubricity of the fuel. The density and viscosity values show that the fuel meets the prescribed values. The value of 845 kg/m3 is the upper limit of the standard for density, which means that the fuel contains relatively more heavier fractions, and the kinematic viscosity value of 3 mm2/s is in the middle of the range given by the standard, which is ideal for reliable injection.

2.2. Characteristic of Used Devices

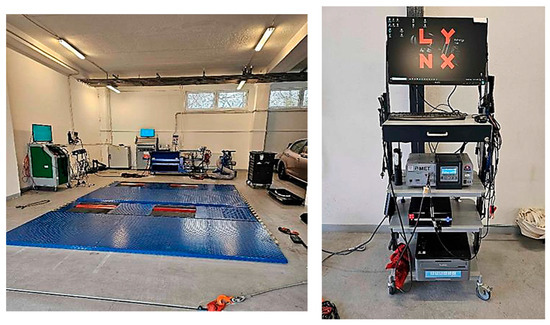

Certified equipment at the Agrobiotech research center was used to measure selected energy parameters, emissions and fuel consumption.

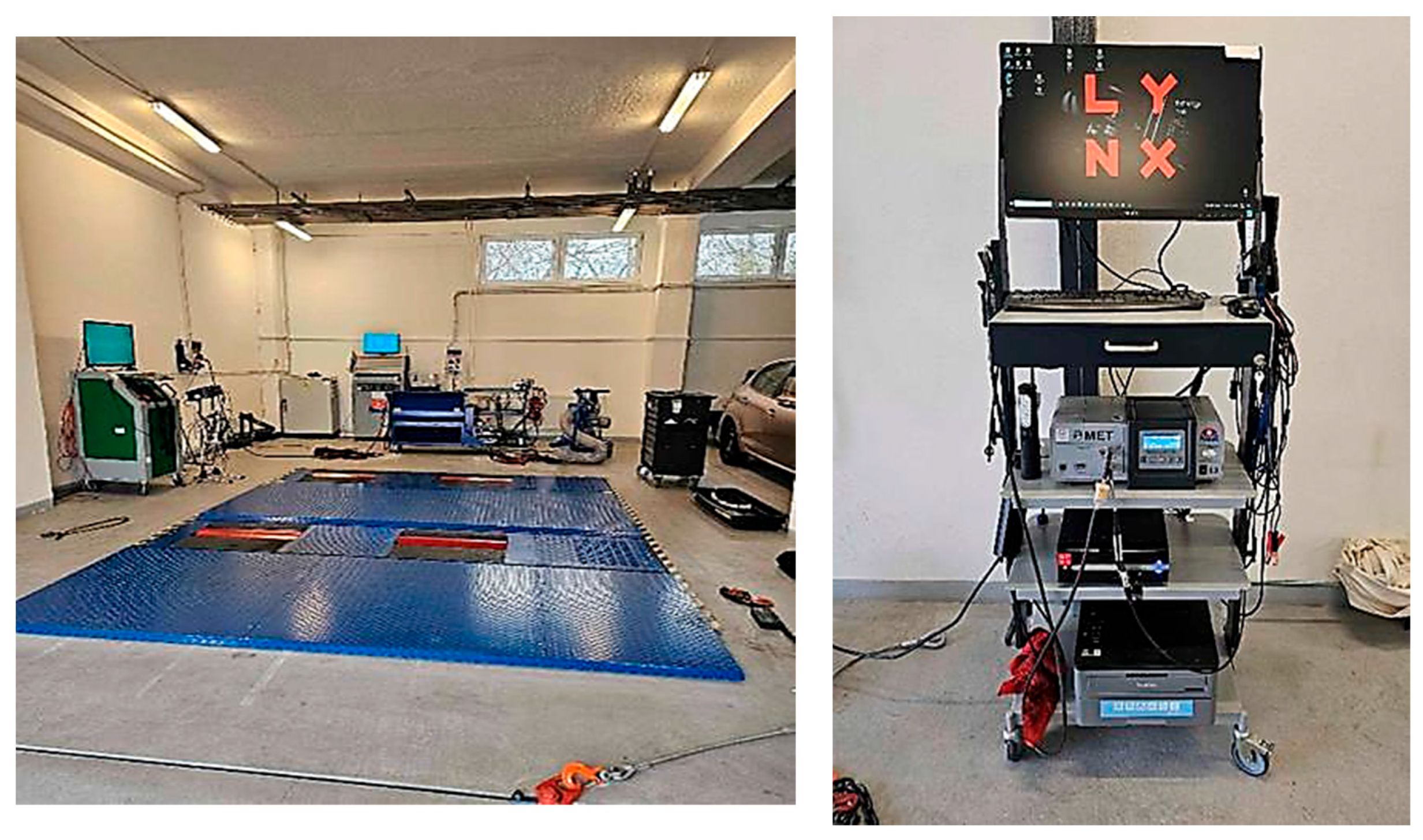

- Cylinder test unit MAHA MSR 500

The performance parameters were measured on a chassis dynamometer manufactured by the MAHA (Haldenwang, Germany), model MSR 500/3 4WD, in combination with the MCD 2000 communication console, which enables the testing of vehicles with 4 × 4 drive. The relevant device can be seen in Figure 1. The accuracy and uncertainty of the device are given in Table 4.

Figure 1.

MAHA MSR 500 Cylinder test bench and MAHA MGT 6.3 Exhaust Gas Analyzer (MAHA, Haldenwang, Germany).

Table 4.

Accuracy and measurement uncertainties of Cylinder test unit MAHA MSR 500 (MAHA, Haldenwang, Germany) and Flow meter AIC-5004 Fuel Flowmaster.

- Correction factor Ka for turbocharged diesel engines

To determine the corrected power, it is necessary to recalculate the measured actual motor power using the relationship for calculating the correction factor Ka. In our case, we used the calculation according to the standard DIN 70020, EWG 80/1269, SAE J1349, JIS D1001 [37,38,39,40,41].

where Ka is the correction factor

- p is the atmospheric pressure on the cylinder test bench;

- T is the temperature of the air on the cylinder test bench;

- fm is the characteristic parameter for each engine type and setting (norm = 0.3).

- Flow meter AIC-5004 Fuel Flowmaster (AIC Systems AG, Alschwil, Switzerland)

Fuel consumption was measured using a flow meter connected to the vehicle’s fuel system in the engine compartment. Data from the flow meter were directly displayed, along with other measured quantities, on the communication console of the dynamometer.

- Exhaust gas analyzer

We analyzed the composition of exhaust emissions using the MAHA MGT 6.3 emission analyzer and the corresponding MAHA Emission Software (version 7.51). The accuracy and uncertainty of this device are given in Table 5. The relevant device can be seen in Figure 1.

Table 5.

Accuracy and measurement uncertainties of the analyzer.

- Engine cooling-Radial fan MAHA Air 7

A MAHA Air 7 (MAHA, Haldenwang, Germany) radial fan was used to cool the engine and thus ensure heat dissipation.

2.3. Characteristics of Preparatory Work Before Measurement

Preparatory work before measurement included centering the vehicle so that the wheels were correctly positioned on the dynamometer rollers and securing the vehicle in accordance with applicable standards. The fuel flow meter was connected to the vehicle’s fuel system, the oil temperature probe was inserted into the dipstick tube, and the emission sampling probe was placed into the exhaust pipe. The OBD (On-Board Diagnostics) terminal of the test bench was then connected to the vehicle’s diagnostic socket. Additionally, the exhaust extraction device was positioned near the exhaust pipe, and a cooling fan was placed in front of the vehicle.

The measurement procedure began with warming up the engine to its operating temperature. Engine performance was first measured through an acceleration test at full throttle without the additive, repeated three times. Subsequently, fuel consumption and engine emissions were measured under a steady load simulated on the chassis dynamometer, also without the additive, and repeated three times. An acceleration test was then conducted under a constant engine load in fourth gear at a speed of 90 km/h for 60 s with a simulated load of F = 600 N. Afterward, the additive was added to the test fuel tank in the prescribed concentration of 700 mL/m3. To ensure that the system was properly flushed with fuel containing the additive, driving was simulated on the chassis dynamometer under a load of 300 N while consuming approximately 2 L of fuel.

Following this preparation, engine performance measurements with the additive were conducted, each repeated three times. Fuel consumption and engine emissions under steady load were then measured with the additive, again repeated three times. After driving 2000 km with the additive, the same set of measurements—engine performance, fuel consumption, and emissions—was repeated three times to evaluate the long-term effects of the additive. Finally, all measured data were processed, analyzed, and evaluated.

It was necessary to calculate and analyze measured parameters using the following basic relationships:

- Calculation of performancewhere Mk is torque [Nm]

ω is angular speed [rad.s−1]

n is revolutions [min−1]

- Calculation of torque

- The quantity of fuel consumed for the selected period of time

- Hourly fuel consumptionwhere ρf is the density of fuel [kg.m−3]

t is time [s]

3. Results

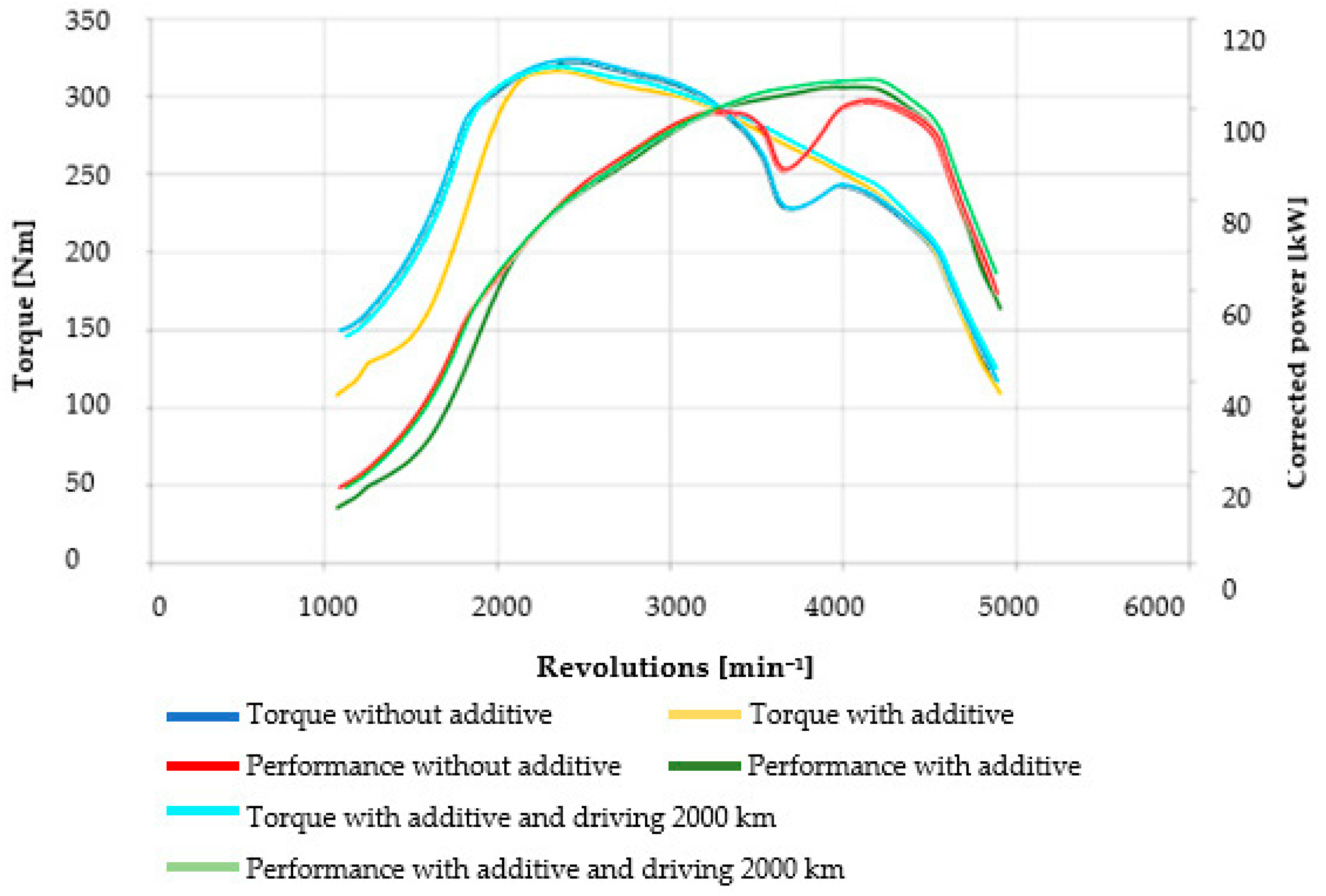

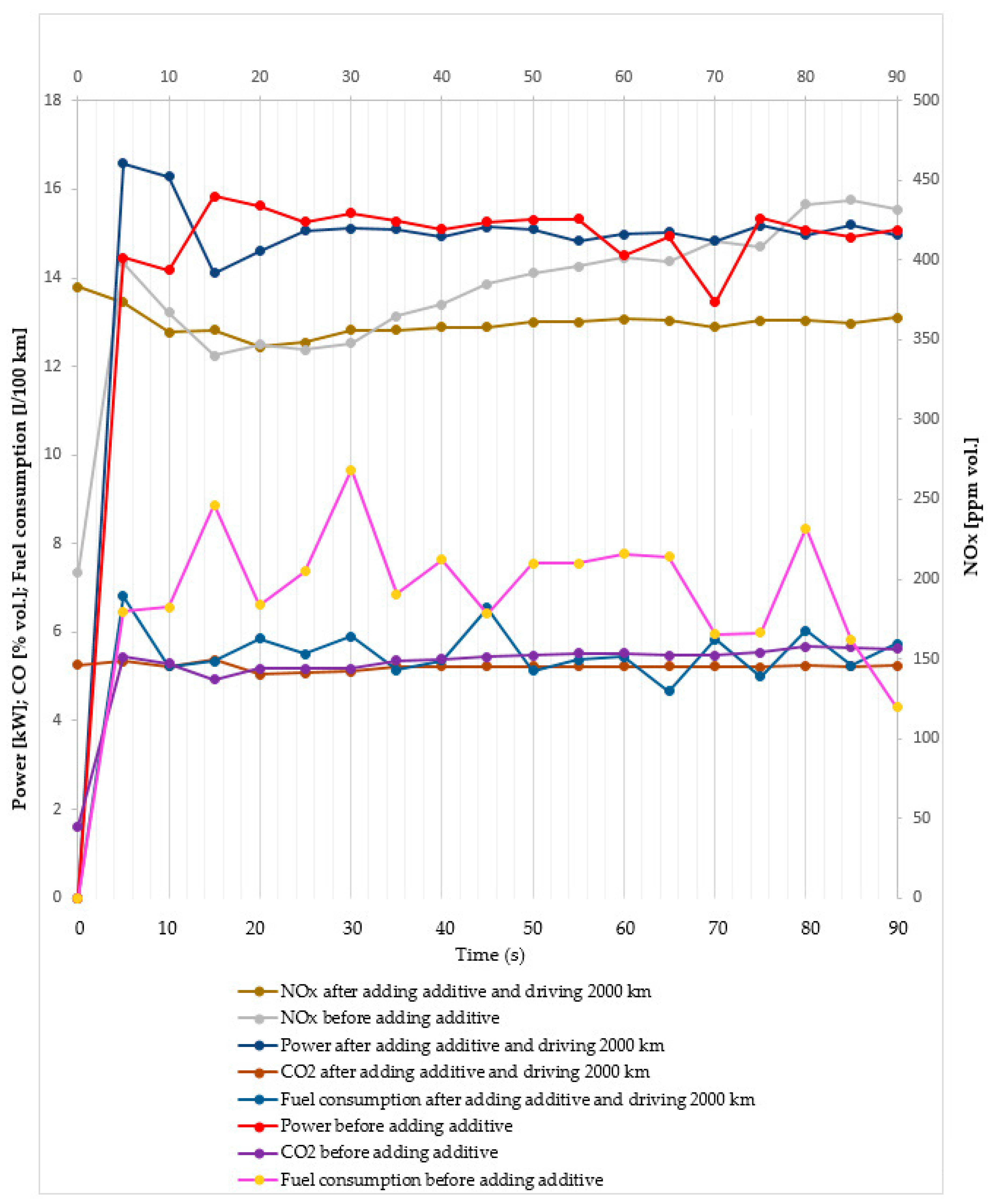

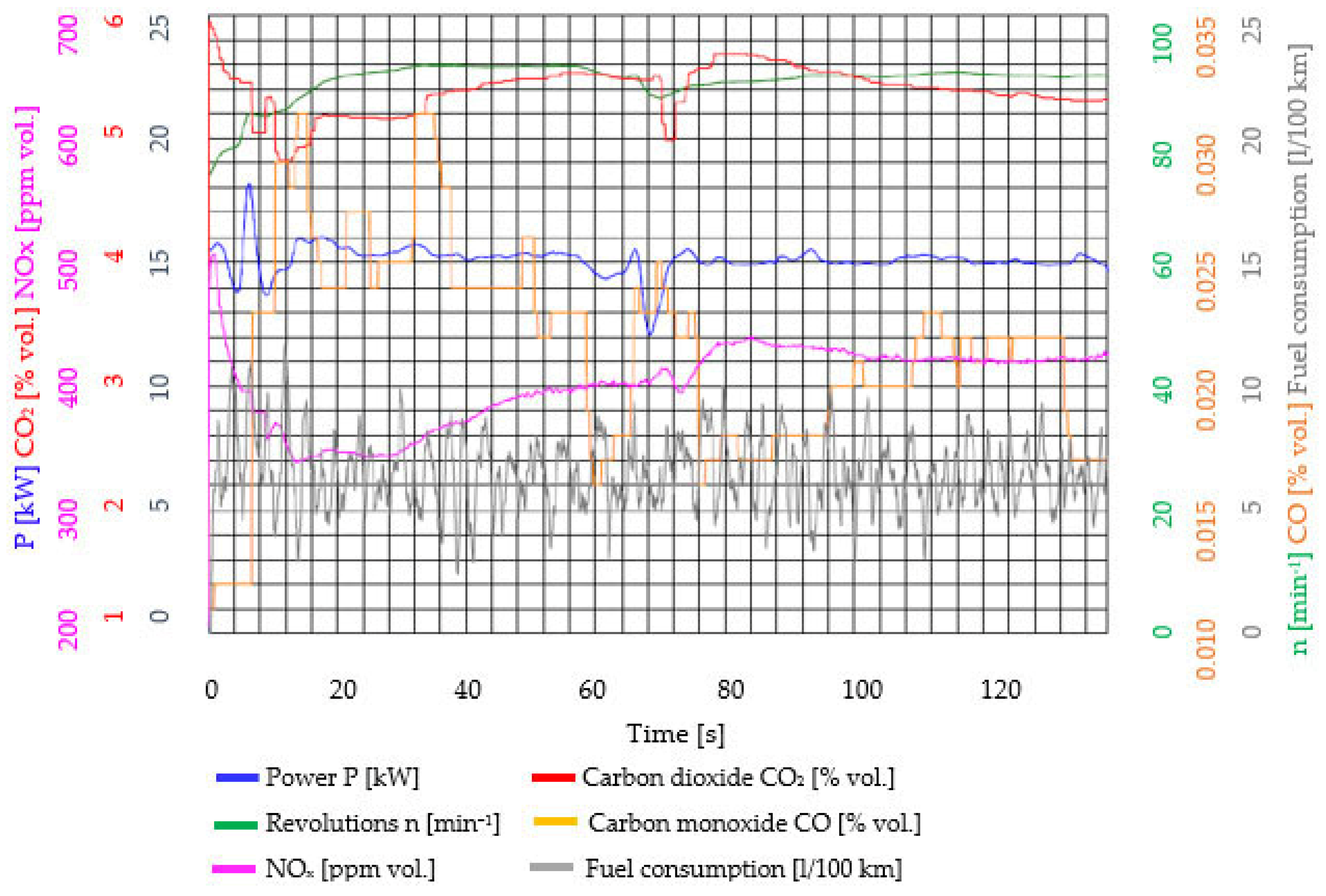

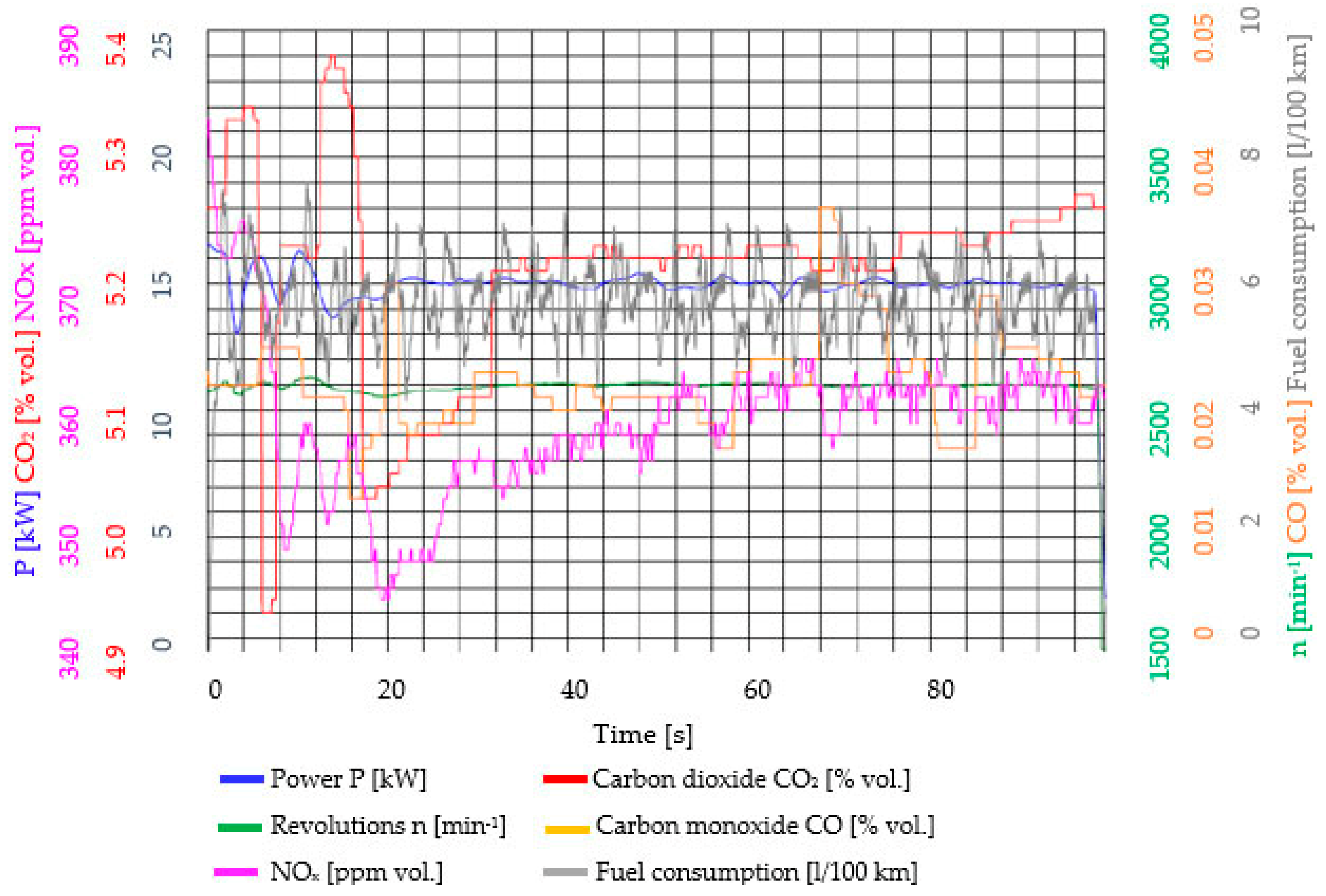

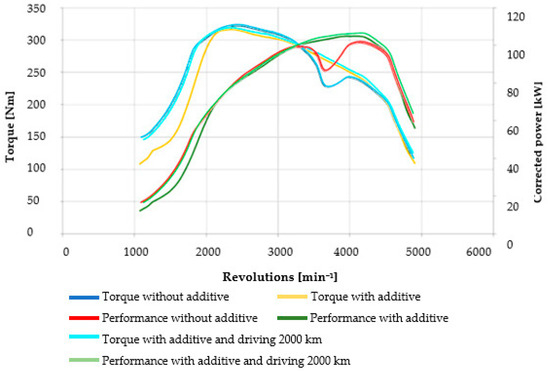

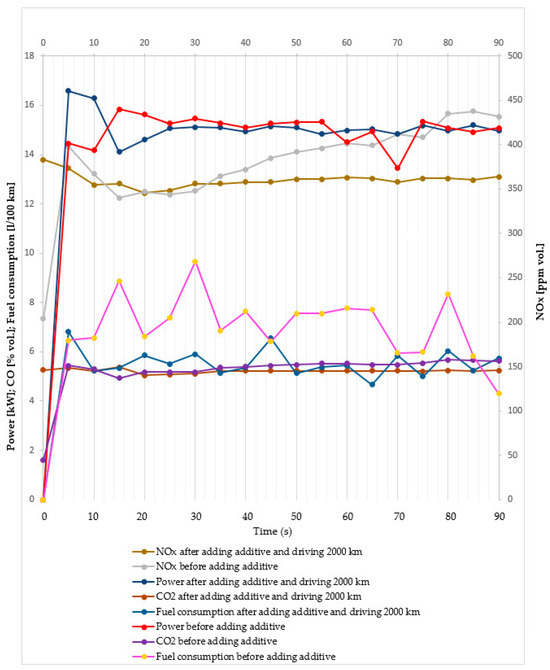

The following section presents the measurement results. The results of power output measurements before and after the use of the additive are shown in Figure 2, showing the dependence of torque and corrected engine power on speed. As can be seen, a slight increase was found in both power and torque. Figure 3 displays the results for emissions and fuel consumption with and without the additive, as well as after 2000 km of driving.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the external speed characteristics of the examined vehicle—before, after adding the additive and driving 2000 km with added additive.

Figure 3.

Time course of emissions and fuel consumption at steady load without additive and after adding additive and driving 2000 km.

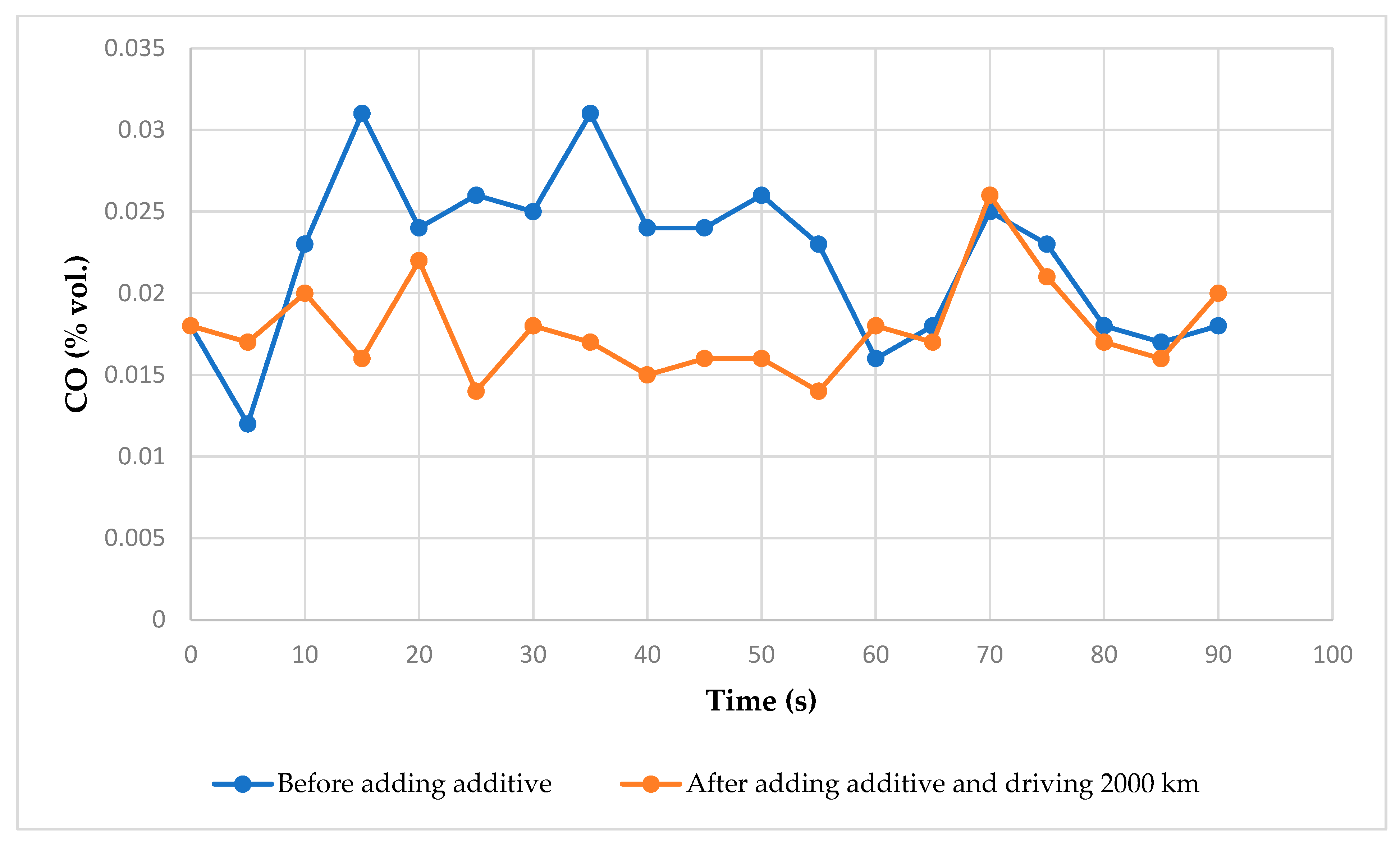

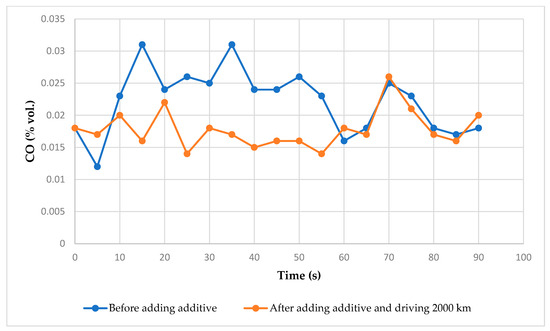

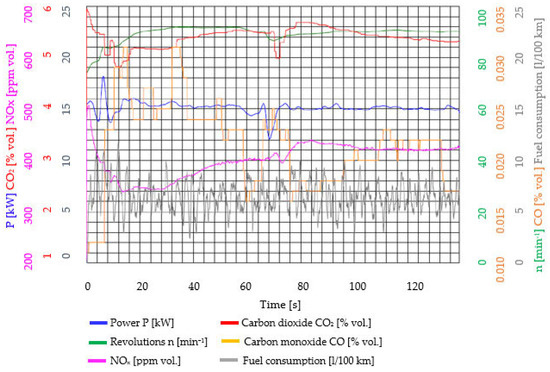

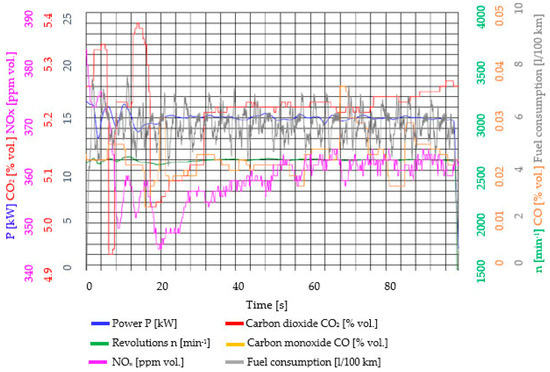

Figure 4 presents the CO emission results under the same conditions. In both of these figures, we can observe the improvement of individual parameters, namely the reduction in emissions and fuel consumption after adding the additive. The time-based progression of emissions and fuel consumption without the additive can be seen in Figure 5, while Figure 6 shows the time course following additive application and 2000 km of driving. In these figures, it is possible to see the authentic output of the measuring device when measuring individual emissions and fuel consumption as a function of time and where the improvement of all examined parameters is also visible.

Figure 4.

Time course of CO emissions at steady load without additive and after adding additive and driving 2000 km.

Figure 5.

Time course of emissions and fuel consumption at steady load before adding the additive.

Figure 6.

Time course of emissions and fuel consumption at steady load after adding the additive and driving 2000 km.

Table 6 summarizes the results of power and torque measurements before and after adding the additive, together with the variation coefficient and standard deviation. In Table 6, it can be seen that the standard deviation ranged from a value of 0.15 for engine power to a value of 4.15 for torque and we can see that for all values, the standard deviation decreased after adding the additive.

Table 6.

Power and torque parameters without additive, with additive and after 2000 km with additive.

Table 7 presents the results for emission parameters. In Table 7, we can see that the standard deviation ranged from 0.003 for CO emissions to 17.64 for NOemissions and we can see that for all values, the standard deviation decreased after adding the additive. The coefficient of variation ranged from 0.011 for CO2 emissions to 0.257 for CO.

Table 7.

Parameters of emissions and fuel consumption without additive, with additive and after 2000 km with additive.

As shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 and Table 8, improvements were observed in all measured parameters after adding the additive. Regarding performance parameters, an increase was recorded in both engine power and revolutions. The average maximum power value before adding the additive was 103.5 kW, after adding the additive, 104.3 kW, and after adding the additive and driving 2000 km, it was 106.3 kW. The maximum engine speed increased from 4006 min−1 to 4073 min−1. The measured engine power differed slightly from the values stated by the vehicle manufacturer; however, an increase of 0.8 kW was recorded after the additive was added. While this change may fall within the measurement deviation, a further increase of 2.71% in power was observed after driving 2000 km with the additive, which is a measurable improvement within the ±2% accuracy margin of the dynamometer, as specified by the manufacturer.

Table 8.

Summary table with average values of performance and emission parameters without additive and with added additive.

Thanks to the addition of the additive, CO2 emissions were reduced by 4.57%. CO2 emissions decreased from 5.47% vol. before adding the additive to 5.29% vol. after the additive was added, and further decreased to 5.21% vol. after driving 2000 km. This may have a positive long-term impact on overall emissions. Initially, CO emissions increased by 19.04% after adding the additive; however, after 2000 km of driving, a reduction of 14.29% was observed compared to the initial measurement. Similarly, NOx emissions increased immediately after the additive was introduced (from 380.25 ppm vol. to 393.14 ppm vol.), but after 2000 km, NOx levels decreased by 3.12%. Fuel consumption with the additive, after 2000 km of driving, decreased by 4.79% from 6.68 L/100 km to 6.36 L/100 km compared to the baseline measurement without the additive. This result confirms the manufacturer’s claim of a minimum reduction of 3.3% in fuel consumption.

4. Discussion

Based on the evaluation of our results, we can conclude that the investigated additive has a positive effect on all the parameters we examined in long-term use. An increase of 2.71% was recorded for the performance parameters and a decrease of 4.57% was found for CO2 emissions after 2000 km. CO and NOx emissions had different trends. After the first addition of the additive, a slight increase occurred, but after 2000 km, a decrease of 14.29% was recorded for CO and 3.12% for NOx emissions. A decrease of 4.79% was found for the diesel consumption results after 2000 km.

Table 9 presents the results of our research together with the results of studies conducted by other authors. Comparable results were reported by Janoško and Feriancová (2019) [42], who evaluated the impact of a VIF brand additive in diesel fuel on vehicle performance, emissions, and fuel consumption. Their experimental measurements partially demonstrated a positive effect, as they observed a 4% decrease in NOX emissions, although fuel consumption increased by 1%.

Another study by Modrocký (2020) [43], which also investigated the effect of the VIF Super Diesel additive, found that NOX emissions decreased by 8.64%, smoke levels (expressed by the absorption correction factor) decreased by 35.48%, and the smoke value expressed as a percentage decreased by 33.8%. Fuel consumption decreased by 4.2% after 3600 km of driving with the additive.

Balušík (2017) [44] conducted similar research using the same additive on a Škoda Octavia I with a 1.9 TDI engine. He reported a 10.25% increase in engine performance, a 29.2% reduction in NOX emissions, and a 3.39% reduction in fuel consumption.

Podskalan (2023) [45] conducted comparable research using the same VIF additive in a Škoda 100. He concluded that NOX emissions were reduced by 11.71%, and fuel consumption decreased by 5.44% after the additive was applied. Similarly,

Marchitto et al. (2024) [46] analyzed the effects of two performance packages (for diesel and gasoline) on the exhaust emissions and fuel consumption of five vehicles. They found that performance packages led to fuel consumption reductions ranging from 1.2% (in a Euro 6 diesel passenger car) to 8.1% (in a Euro 4 diesel passenger car). They also observed significant reductions in CO, total hydrocarbons (THC), and particulate matter (PM) in Euro 4 vehicles using additives. However, an increase in NOX emissions was also noted, in line with PM reduction.

Author Szorád (2025) [47] evaluated the effects of the Excellium Pro Concentrate fuel additive for diesel engines. Adding the additive to the fuel showed a slight decrease in fuel consumption and a slight improvement in engine power and torque. The author also noted changes in emissions, where the volume values of individual components decreased by approximately 6.99%. The additive manufacturer declared a possible fuel saving of 3.3%, while the measurement results showed an even greater decrease in consumption, thus not only meeting but exceeding the expected efficiency of the additive. When measuring CO concentration in both cases, the results indicated the stability of this parameter even when the chemical composition of the fuel changed. Regarding engine power, after adding the additive, the engine power increased by approximately 1.49%. This slight increase may indicate an improvement in the combustion process or a positive effect of the additive on the overall dynamics of the engine under load. The maximum torque increased from 275.27 Nm to 283.07 Nm, an increase of approximately 2.83%. This indicates that the presence of the additive improved engine dynamics, enhancing the overall performance of the vehicle and its adaptability to different operating conditions.

When compared with other authors, it can be stated that the results of our measurements achieved the most favorable values in most parameters. For example, in performance, we recorded the highest increase after applying the additive compared to other studies. Conversely, in CO2 emissions and fuel consumption, we observed the largest decreases. For CO emissions, our results were similar to those of author [47].

Table 9.

Comparison of our results with the results of other authors.

Table 9.

Comparison of our results with the results of other authors.

| Parameters | Our Results | [47] | [42] | [43] | [45] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before adding additive | Corrected engine power P [kW] | 103.5 | 88.6 | 108.6 | 71.4 | 30.7 |

| CO [% vol.] | 0.022 | 0.019 | 0.1 | - | 1.55 | |

| CO2 [% vol.] | 5.47 | 7.18 | - | - | - | |

| HC [ppm vol.] | - | 5.7 | - | - | 406.87 | |

| NOx [ppm vol.] | - | - | 102 | 311.2 | 1557.19 | |

| Fuel consumption [L/100 km] | 6.68 | 6.62 | 5.84 | 7.62 | 4.04 | |

| After adding additive | Corrected engine power P [kW] | 104.3 | 89.27 | 109.4 | 72.02 | 31.4 |

| CO [% vol.] | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.03 | - | 1.18 | |

| CO2 [% vol.] | 5.29 | 7.04 | - | - | - | |

| HC [ppm vol] | - | 7.0 | - | - | 291.93 | |

| NOx [ppm vol.] | - | - | 98 | 208.19 | 1374.8 | |

| Fuel consumption [L/100 km] | 6.25 | 6.25 | 5.92 | 7.37 | 3.82 |

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the impact of a novel diesel fuel additive designed to enhance fuel quality, combustion characteristics, emission profile, and overall fuel efficiency in a passenger vehicle equipped with an internal combustion engine. The test vehicle was a Volkswagen Golf 1.9 TDI, representative of a widely used class of older diesel-powered cars. Monitored parameters were measured on a chassis dynamometer together with a flow meter and an exhaust gas analyzer.

The experimental results demonstrated a consistently positive influence of the additive across all monitored parameters. As for performance parameters, a 2.71% increase in corrected engine power was recorded after 2000 km of operation with the additive.

The most significant improvement was observed in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, which decreased by 4.57%. This reduction was evident immediately after the additive was introduced and continued to improve with extended operation.

After 2000 km, CO emissions were reduced by 14.29%, while NOX emissions decreased by 3.12% compared to baseline measurements. Furthermore, fuel consumption showed a 4.79% reduction, indicating improved combustion efficiency and optimized energy use.

The final evaluation confirms that the application of this diesel additive can lead to measurable improvements in engine performance, fuel economy, and emission reduction—without requiring any mechanical modifications to the vehicle. These benefits are particularly valuable for older vehicles, where technical upgrades are often economically or practically unfeasible. Based on the measurements and results obtained within this research, it is appropriate to recommend the use of additives in diesel-powered vehicles aged 15 years and older during the ongoing transition to alternative propulsion systems.

The findings provide a strong basis for further research and development in the field of fuel additive technologies. Future studies should explore a broader range of operating conditions, vehicle types, and long-term effects to fully validate and expand upon the promising results observed in this investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.J. and M.K.; Methodology, I.J.; Writing—original draft preparation, I.J. and M.K.; Writing—review and editing, M.K.; Formal analysis, M.K.; Investigation, I.J. and M.K.; Resources, I.J.; Project administration, I.J.; Validation, I.J. and M.K.; Supervision, I.J.; Data curation, M.K.; Funding acquisition, I.J.; Visualization, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Elkelawy, M.; El Shenawy, E.A.; Bastawissi, H.A.; Shams, M.M.; Panchal, H.A. Comprehensive review on the effects of diesel/biofuel blends with nanofluid additives on compression ignition engine by response surface methodology. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2022, 14, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonický, J. Motorové Vozidlá 1; Slovak University of Agriculture: Nitra, Slovakia, 2010; pp. 21–65. [Google Scholar]

- Janoško, I.; Kuchar, P. Evaluation of the fuel commercial additives effect on exhaust gas emissions, fuel consumption and performance in diesel and petrol engine. Agron. Res. 2018, 16, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matějovský, V. Automobilová Paliva; Grada: Praha, Czech Republic, 2005; pp. 20–190. [Google Scholar]

- Jablonický, J.; Hujo, Ľ.; Kosiba, J.; Králik, M.; Angelovič, M. Measurement of diesel engine smoke emission at the application of hydrogene. Tech. V Technológiách Agrosektora 2012, 1, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. CO2 Emission Performance Standards for Cars and Vans. European Climate Action—Road Transport: Reducing CO2 Emissions from Vehicles. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/transport/road-transport-reducing-co2-emissions-vehicles/co2-emission-performance-standards-cars-and-vans_en (accessed on 11 August 2024).

- Arslan, A.B.; Çelik, M. Investigation of the Effect of CeO2 Nanoparticle Addition in Diesel Fuel on Engine Performance and Emissions. J. ETA Marit. Sci. 2022, 10, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, F.; Pourdarbani, R.; Ardabili, S.; Hernandez-Hernandez, J.L. Life Cycle Assessment of a Hybrid Self-Power Diesel Engine. Acta Technol. Agric. 2023, 26, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karczewski, M.; Chojnowski, J.; Szamrej, G. A review of low-CO2 emission fuels for a dual-fuel RCCI engine. Energies 2021, 14, 5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diesel Engine. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/technology/diesel-engine (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Wen, M.; Yin, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; Cui, Y.; Ming, Z.; Feng, L.; Yue, Z.; Yao, M. Effects of Different Gasoline Additives on Fuel Consumption and Emissions in a Vehicle Equipped With the GDI Engine. Front. Mech. Eng. 2022, 8, 924505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Acharya, A.K.; Parida, B.; Panda, A.K.; Yao, Z.; Kumar, S. Sustainable combustion and pollution cost analysis of diesel engine fueled with waste plastics pyrolysis oil and advanced additives: An experimental investigation on emission reduction potential. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 67, 104136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickevičius, T.; Dudziak, A.; Matijošius, J.; Rimkus, A. Evaluation of Tire Pyrolysis Oil–HVO Blends as Alternative Diesel Fuels: Lubricity, Engine Performance, and Emission Impacts. Energies 2025, 18, 4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhameed, E.; Tashima, H. EGR and Emulsified Fuel Combination Effects on the Combustion, Performance, and NOx Emissions in Marine Diesel Engines. Energies 2023, 16, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Role of Fuel Additives in Improving Diesel Fuel Performance and Longevity. Available online: https://www.fueltek.co.uk/the-role-of-fuel-additives-in-improving-diesel-fuel-performance-and-longevity (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Abdelwahed, S.B.; Hamdi, F.; Gassoumi, M.; Yahya, I.; Moussa, N.; Alrasheedi, N.H.; Ennetta, R.; Louhichi, B. Enhancing Diesel Engine Performance Through Hydrogen Addition. Fire 2025, 8, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonický, J.; Tulík, J.; Bártová, S.; Tkáč, Z.; Kosiba, J.; Kuchar, P.; Čorňák, Š.; Kollárová, K.; Kaszkowiak, J.; Tomić, M.; et al. Influence of Decarbonization on Selected Parameters of ICE. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewbuddee, C.; Maithomklang, S.; Aengchuan, P.; Wiangkham, A.; Klinkaew, N.; Ariyarit, A.; Sukjit, E. Effects of alcohol-blended waste plastic oil on engine performance characteristics and emissions of a diesel engine. Energies 2023, 16, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddartha, G.N.V.; Ramakrishna, C.S.; Kujur, P.K.; Rao, Y.A.; Dalela, N.; Yadav, A.S.; Sharma, A. Effect of fuel additives on internal combustion engine performance and emissions. Mater. Today 2022, 63, A9–A14. [Google Scholar]

- Lamore, M.T.; Zeleke, D.S.; Kassa, B.Y. A comparative study on the effect of nano-additives on performance and emission characteristics of CI engine run on castor biodiesel blended fuel. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2023, 20, 100493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelovič, M.; Jablonický, J.; Tkáč, Z.; Angelovič, M. Comparison of Smoke Emissions in Different Combustion Engine Fuels. Acta Technol. Agric. 2020, 23, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Wen, M.; Liu, H. Effects of different additives on physicochemical properties of gasoline and vehicle performance. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 242, 107668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, M.; Valle, S.; Cevallos, J.; Calvopina, H.; Montero, F. Analysis of Emissions and Fuel Consumption of a Truck Using a Mixture of Diesel and Cerium Oxide on High-Altitude Roads. Vehicles 2025, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Yao, L. Effect of Combustion Boundary Conditions and n-Butanol on Surrogate Diesel Fuel HCCI Combustion and Emission Based on Two-Stroke Diesel Engine. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdikopoulos, M.; Karageorgiou, T.; Ntziachristos, L.; Cavellin, L.D.; Joly, F.; Vigneron, J.; Arfire, A.; Debert, C.H.; Sanchez, O.; Gaie-Levrel, F.; et al. Developing Emission Factors from Real-World Emissions of Euro VI Urban Diesel, Diesel-Hybrid, and Compressed Natural Gas Buses. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenďák, P.; Tkáč, Z.; Jablonický, J. Návrh Metodiky Výkonu Emisných Kontrol pre Vozidlá so Zážihovým Motorom a Zdokonaleným Emisným Systémom, 1st ed.; Slovak University of Agriculture: Nitra, Slovakia, 2015; pp. 17–169. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Mendoza, A.S.; Vinueza-Morales, M.; Alcázar-Espinoza, J.A.; Pineda-Silva, G.V.; Aucay-Garcia, I.P. Gasoline Vehicle Emissions at High Altitude: An Exploratory STATIS Study in Guaranda, Ecuador. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmer, H.; Alahmer, A.; Alamayreh, M.I.; Alrbai, M.; Al-Rbaihat, R.; Al-Manea, A.; Alkhazaleh, R. Optimal Water Addition in Emulsion Diesel Fuel Using Machine Learning and Sea-Horse Optimizer to Minimize Exhaust Pollutants from Diesel Engine. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, S. The Role of Cheap Chemicals Containing Oxygen Used as Diesel Fuel Additives in Reducing Carbon Footprints. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, S.; Rajendran, S.; Azad, K. Assessment of performance, combustion, and emission behavior of novel annona biodiesel-operated diesel engine. In Advances in Eco-Fuels for a Sustainable Environment; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Elsevier: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Volume 14, pp. 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resitoglu, İ.A.; Altinisik, K.; Keskin, A. The pollutant emissions from diesel-engine vehicles and exhaust aftertreatment systems. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2015, 17, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Wang, M.; Qin, P.; Yan, T.; Li, K.; Wang, X.; Han, C. Field Measurements of Vehicle Pollutant Emissions in Road Tunnels at Different Altitudes. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 118, 104187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Králik, M.; Jablonický, J.; Tkáč, Z.; Hujo, L.; Uhrinová, D.; Kosiba, J.; Tulík, J.; Záhorská, R. Monitoring of selected emissions of internal combustion engine. Res. Agric. Eng. 2016, 62, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synák, F.; Synák, J. Study of the Impact of Malfunctions of and Interferences in the Exhaust Gas Recirculation System on Selected Vehicle Characteristics. SAE Int. J. Engines 2022, 15, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synák, F.; Synák, J. Impact of using different types of gasoline on selected vehicle properties. Appl. Eng. Lett. 2020, 5, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STN EN 590: 2023; Automotive Fuels, Diesel Fuel. Requirements and Test Methods. Office for Standardization, Metrology and Testing of the Slovak Republic: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2023.

- EWG 80/1269/EEC. Council Directive 80/1269/EEC of 16 December 1980 on the Approximation of the Laws of the Member States Relating to the Engine Power of Motor Vehicles. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/1980/1269/oj/eng (accessed on 9 February 2025).

- DIN 70020; Road Vehicles—Automotive Engineering—Part 7: Engine Mass Standard by Deutsches Institut Fur Normung. German Institute for Standardization: Berlin, Germany, 2013. Available online: https://www.dinmedia.de/en/standard/din-70020-7/170094456 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- SAE J1349; Engine Power Test Code—Spark Ignition and Compression Ignition. Society of Automotive Engineers. SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2011. Available online: https://www.sae.org/standards/j1349_201109-engine-power-test-code-spark-ignition-compression-ignition-installed-net-power-rating (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Slovak Republic Act no. 106/2018 Coll. on the Operation of Vehicles in Road Traffic and on the Amendment of Some Laws. Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/ezbierky/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2018/106/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Methodological Guideline No. 2/2020 for Carrying Out Emission Control of Regular Motor Vehicles with a Spark-Ignition Engine with an Unimproved Emission System, with a Spark-Ignition Engine with an Improved Emission System and with a Diesel Engine Issued by the Ministry of Transport and Construction of the Slovak Republic Pursuant to Act No. 106/2018 Coll. Available online: https://www.seka.sk/storage/app/media/stranky/legislativa/metodiky/2020/MP_2_2020.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Janoško, I.; Feriancová, F. The effect of diesel additive on emissions and engine performance. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Trends in Agricultural Engineering (TAE), Prague, Czech Republic, 17–20 September 2019; Czech University of Life Sciences: Prague, Czech Republic, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Modrocký, P. Testovanie zvolenej prísady do paliva. In Proceedings of the Scientific Conference: Recent Advances in Agriculture, Mechanical Engineering and Waste Policy, Nitra, Slovakia, 15 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Balušík, M. Prevádzkové Testovanie Prísady do Motorovej Nafty. Diploma Thesis, Slovak University of Agriculture, Faculty of Engineering, Department of transport and handling, Nitra, Slovakia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Podskalan, J. Hodnotenie parametrov aditíva do benzínu vyrábaného pre automobilový priemysel. In Proceedings of the Scientific Conference: Recent Advances in Agriculture, Mechanical Engineering and Waste Policy, Nitra, Slovakia, 20 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Marchitto, L.; Costagliola, M.A.; Berra, A. Influence of Performance Packages on Fuel Consumption and Exhaust Emissions of Passenger Cars and Commercial Vehicles under WLTP. Energies 2024, 17, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szorád, A. Hodnotenie Parametrov Aditíva do Nafty Vyrábaného pre Automobilový Priemysel. Bachelor’s Thesis, Slovak University of Agriculture, Faculty of Engineering, Department of transport and handling, Nitra, Slovakia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).