PEG-Coated Nanostructured NiO Synthesized Sonochemically in 1,2-(Propanediol)-3-methylimidazolium Hydrogen Sulfate Ionic Liquid: DFT, Structural and Dielectric Characterization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Instruments

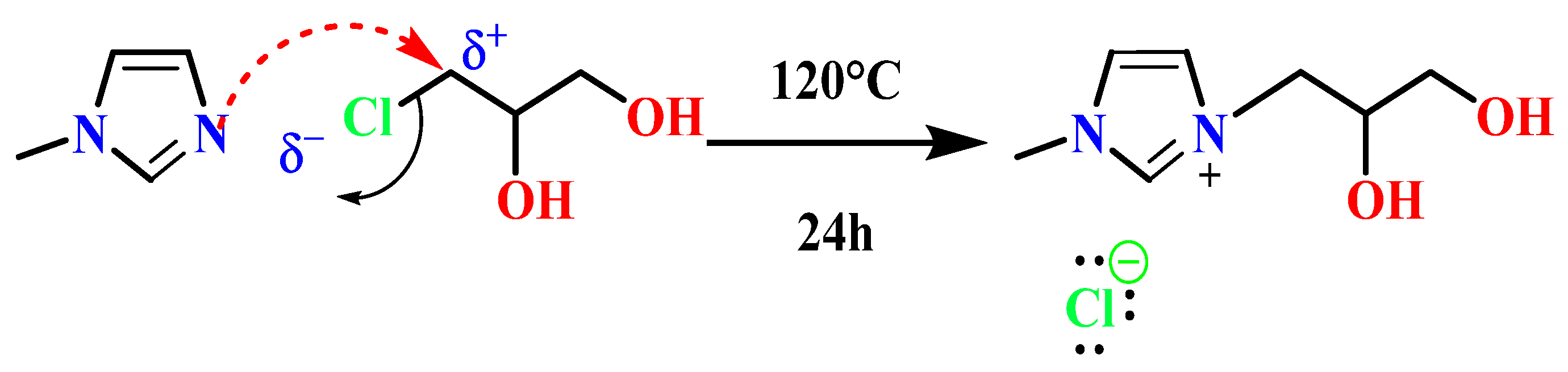

2.3. Synthesis and Characterization of 1,2-(Propanediol)-3-methylimidazolium Chloride Ionic Liquid [PDOHMIM+][Cl−] [33,34,35]

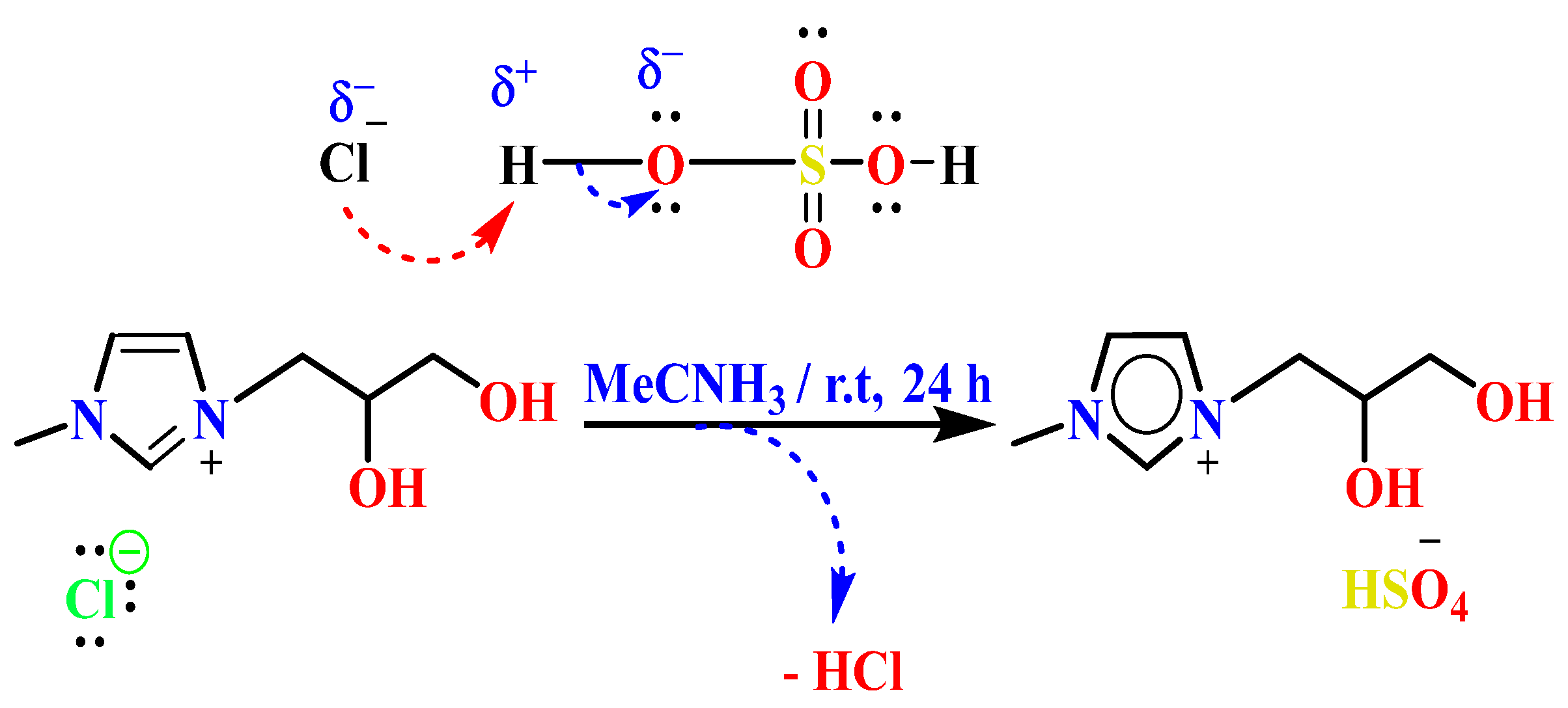

2.4. Synthesis and Characterization of 1,2-(Propanediol)-3-methylimidazolium Hydrogénosulfate [PDOHMIM+][HSO4−] [33,34]

2.5. Sonochemical Synthesis of [NiO NPs + IL]

2.6. Preparation of PEG-Coated [NiO NPs + IL]

2.7. Computational Methods

3. Results and Discussion

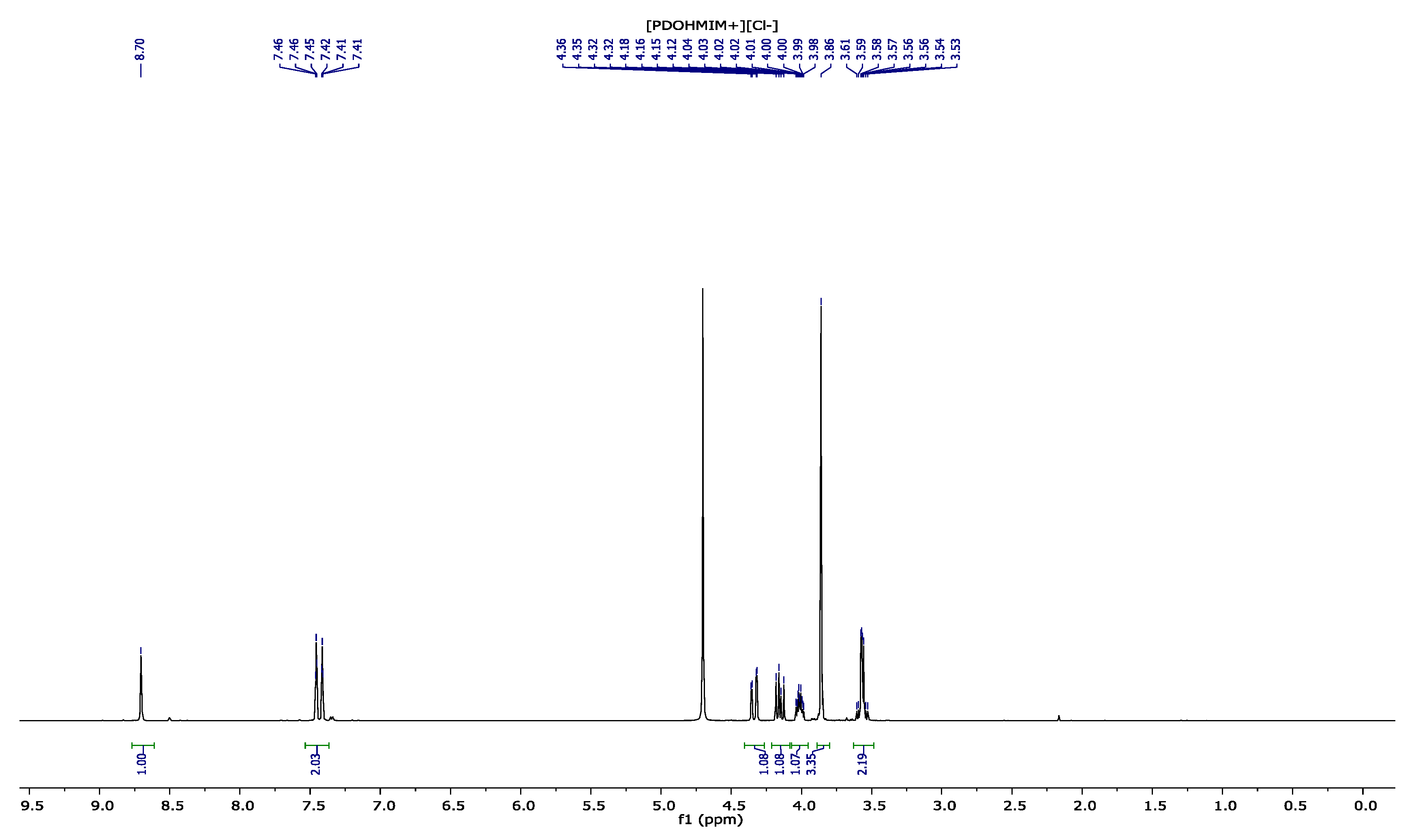

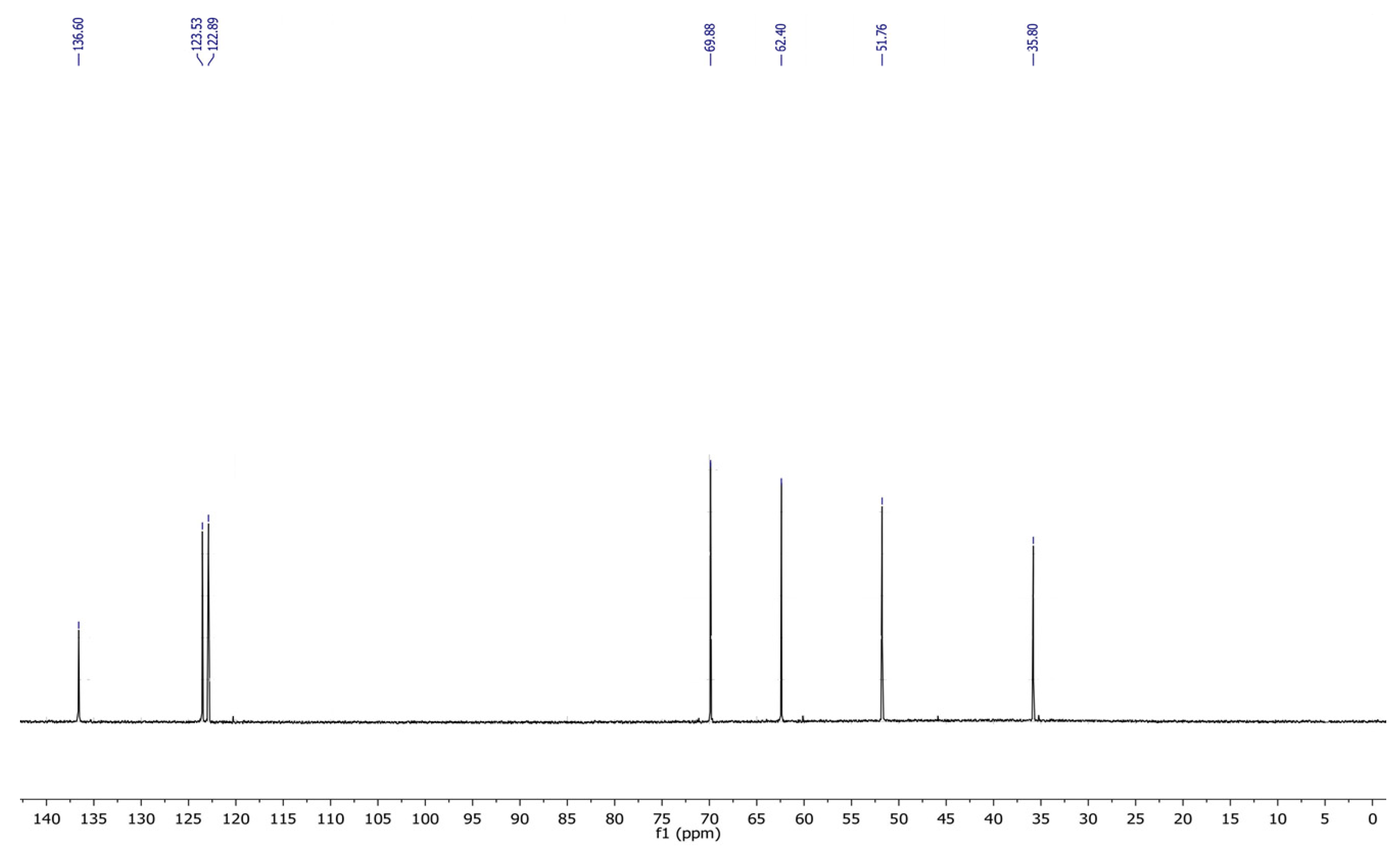

3.1. NMR Results

3.2. 1,2-(Propanediol)-3-methylimidazolium Chloride [PDOHMIM+][Cl−] 1H, 13C NMR

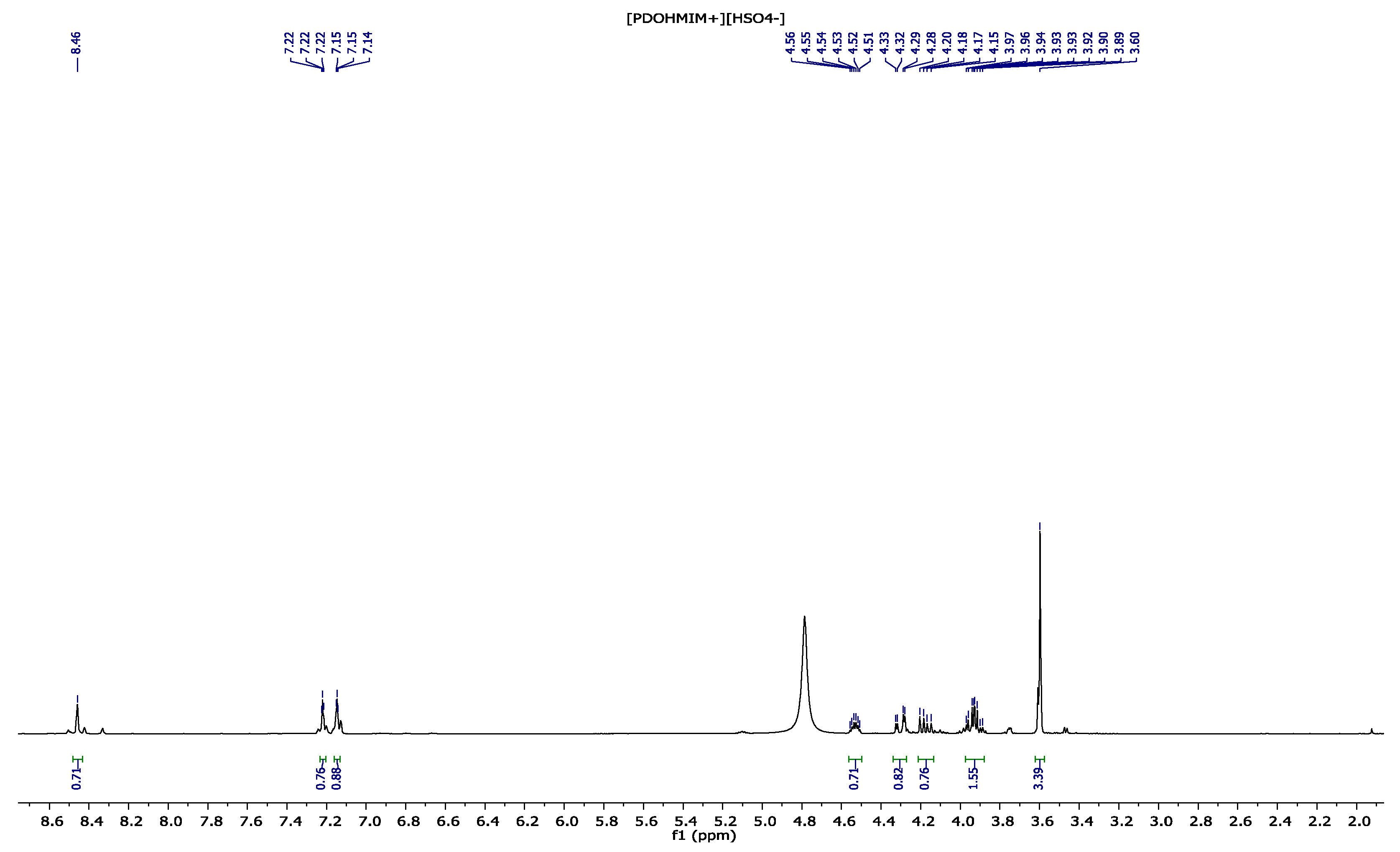

3.3. 1,2-(Propanediol)-3-methylimidazolium Hydrogenosulfate [PDOHMIM+][HSO4−] 1H, 13C NMR

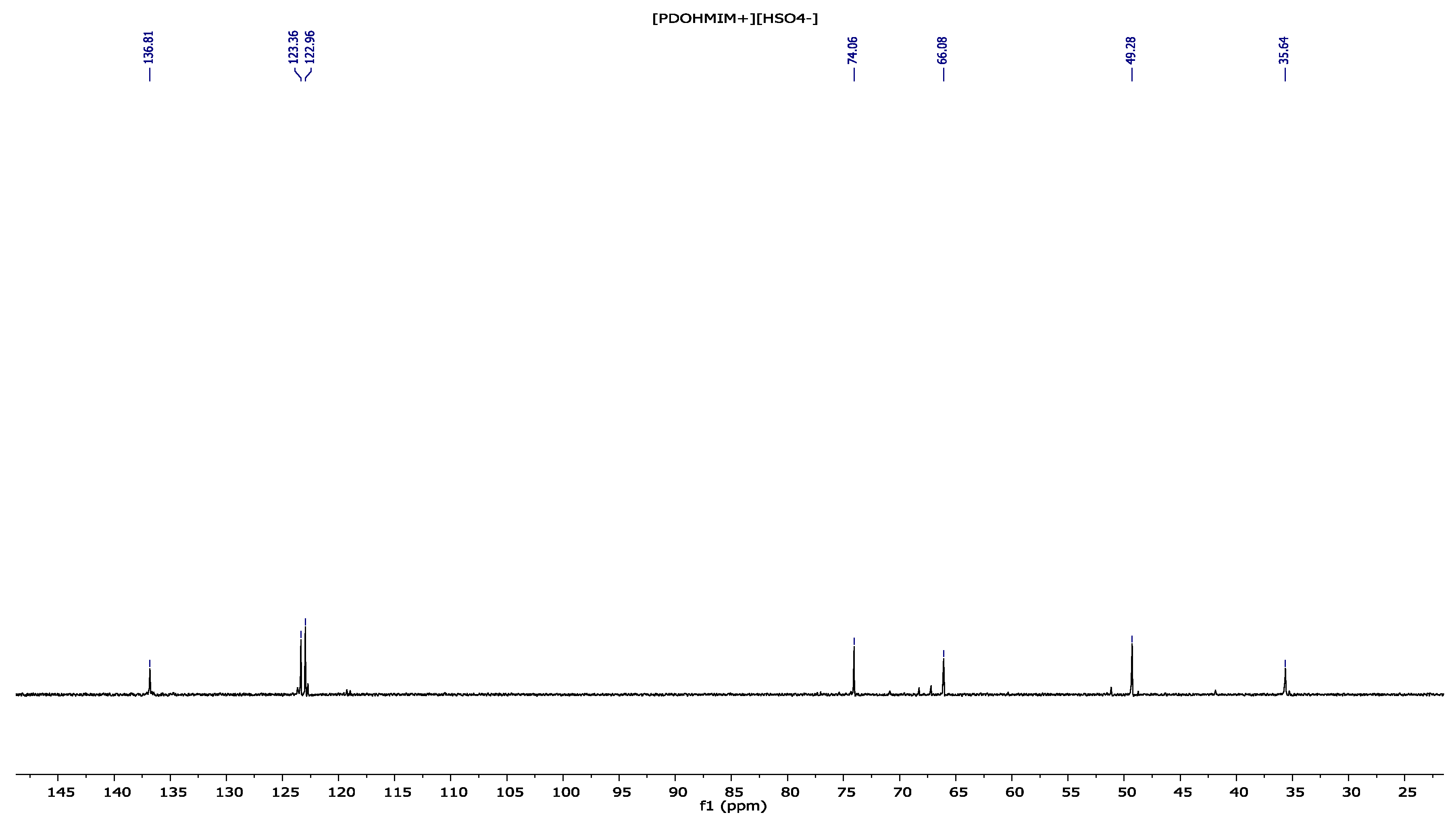

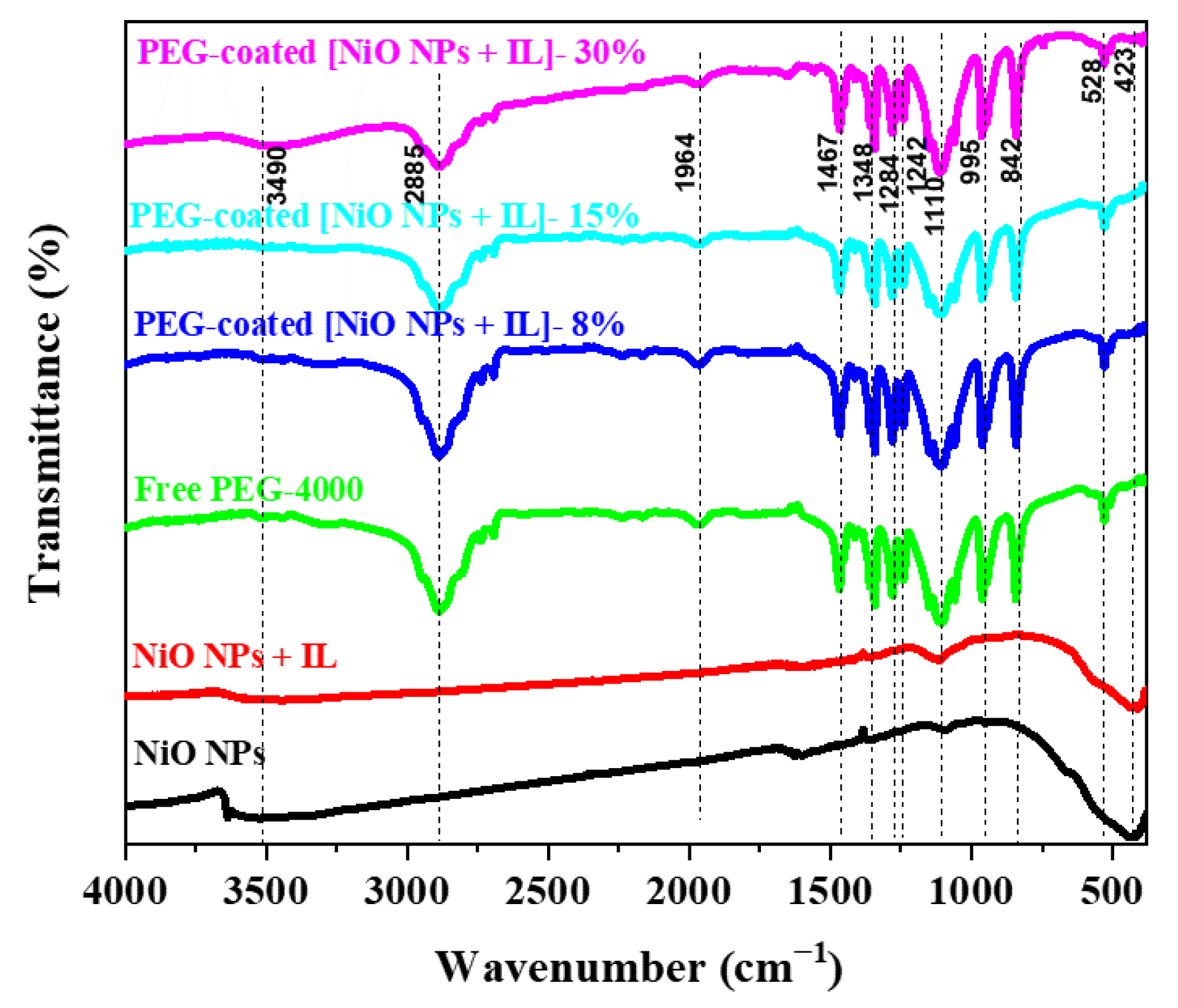

3.4. Compared FTIR/ATR Spectra of [PDOHMIM+][Cl−] and [PDOHMIM+][HSO4−]

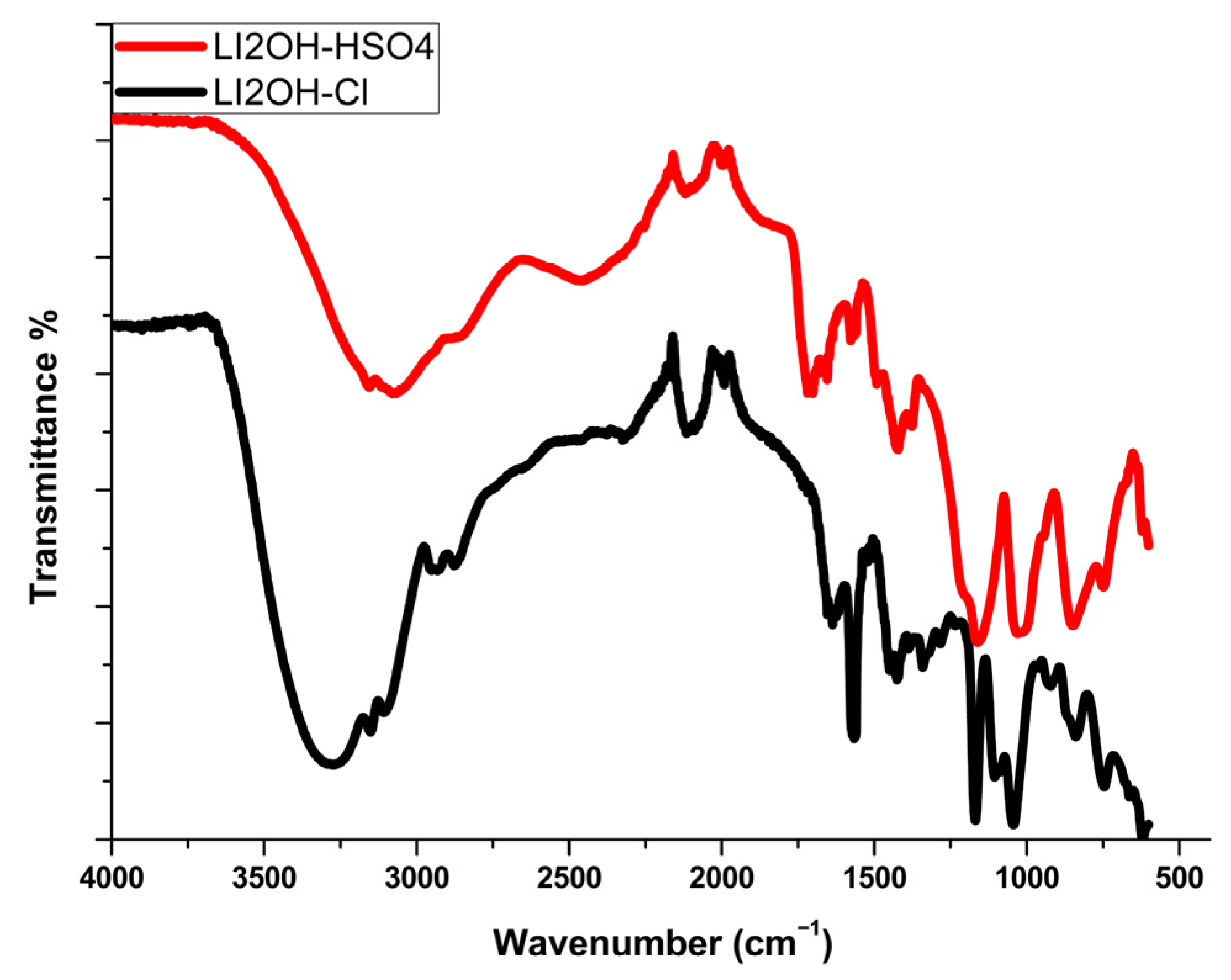

3.5. FTIR Analysis of PEG-Coated [NiO NPs + IL]

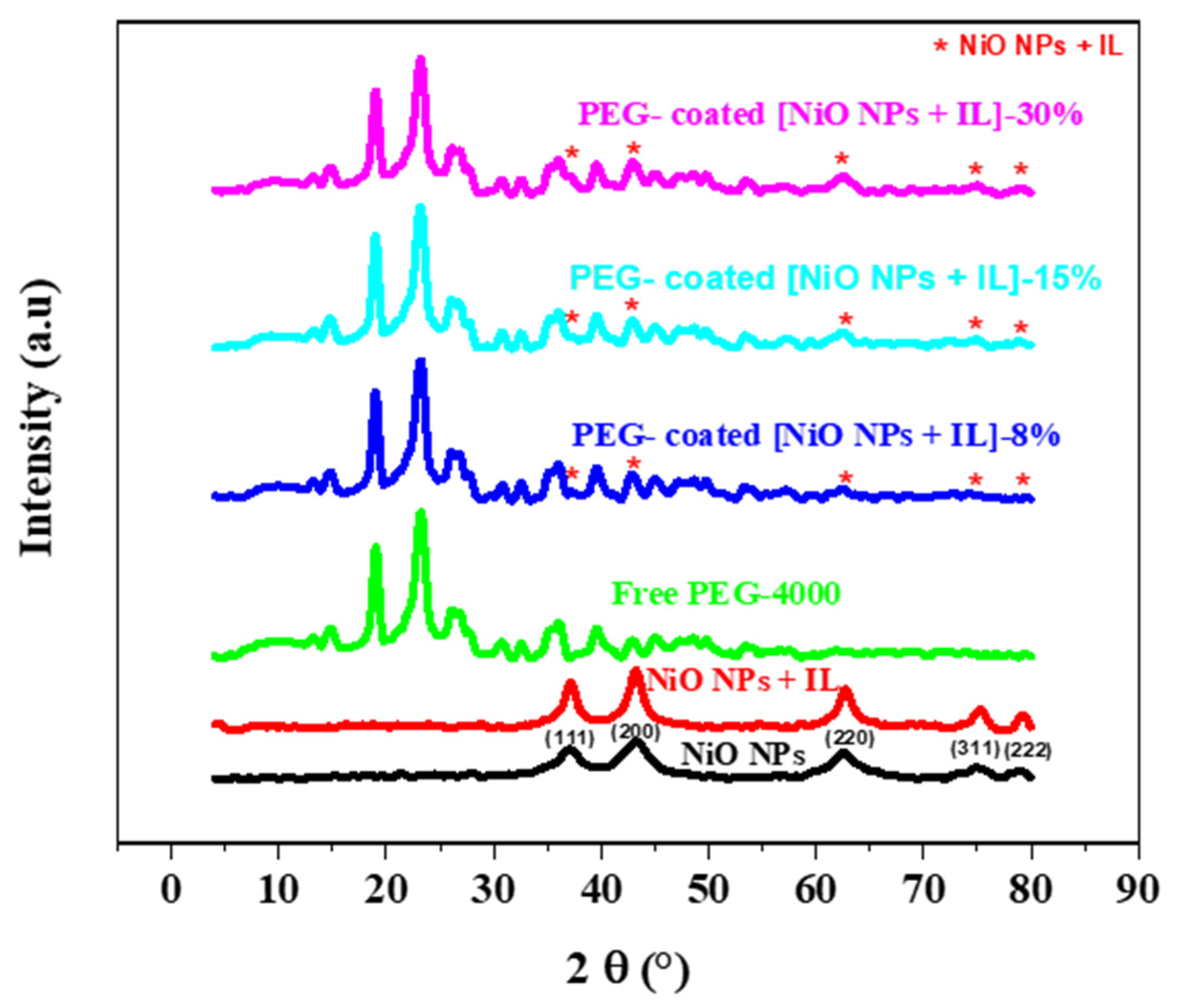

3.6. XRD Analysis of PEG Coated [NiO NPs + IL]

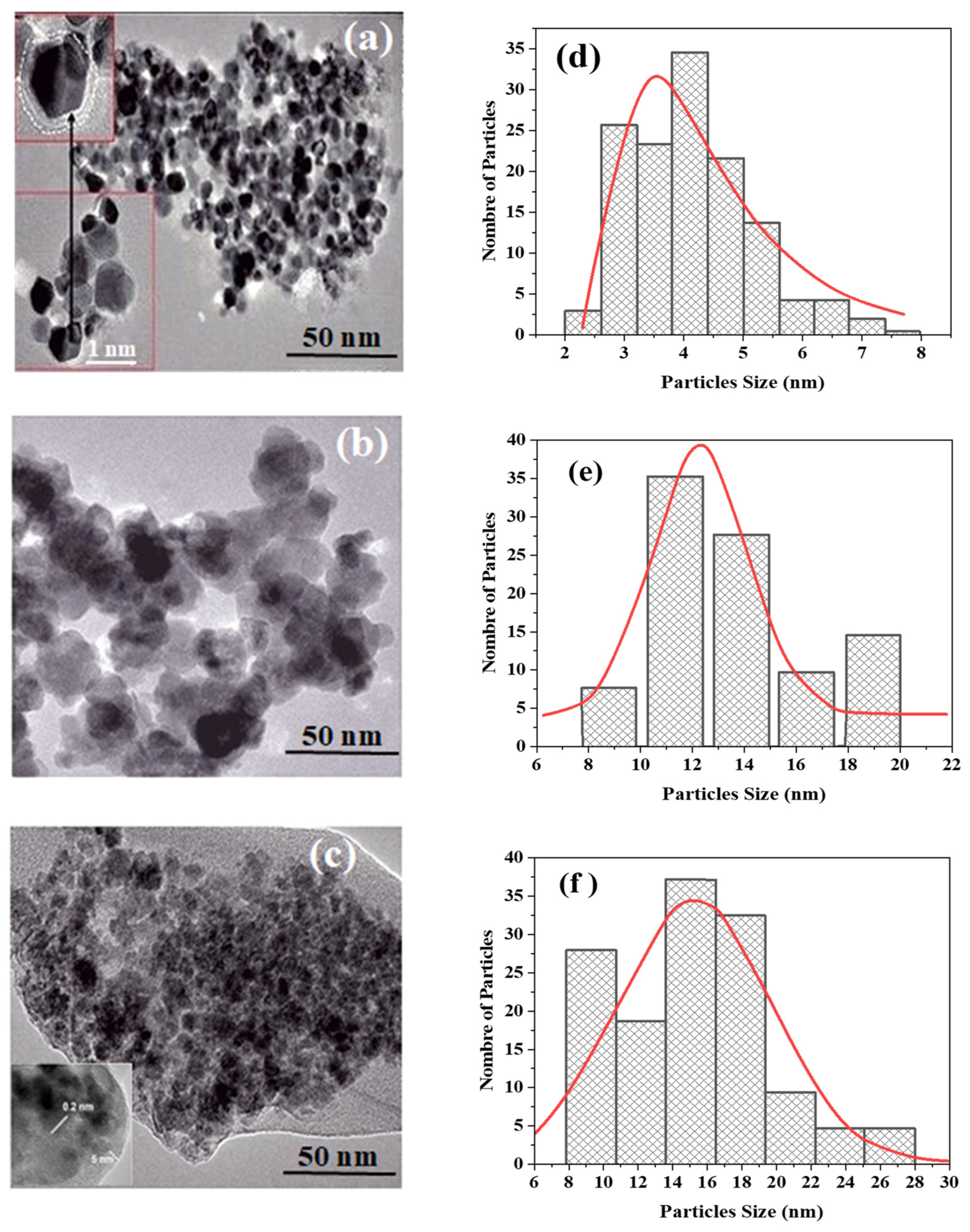

3.7. TEM Morphology Analysis

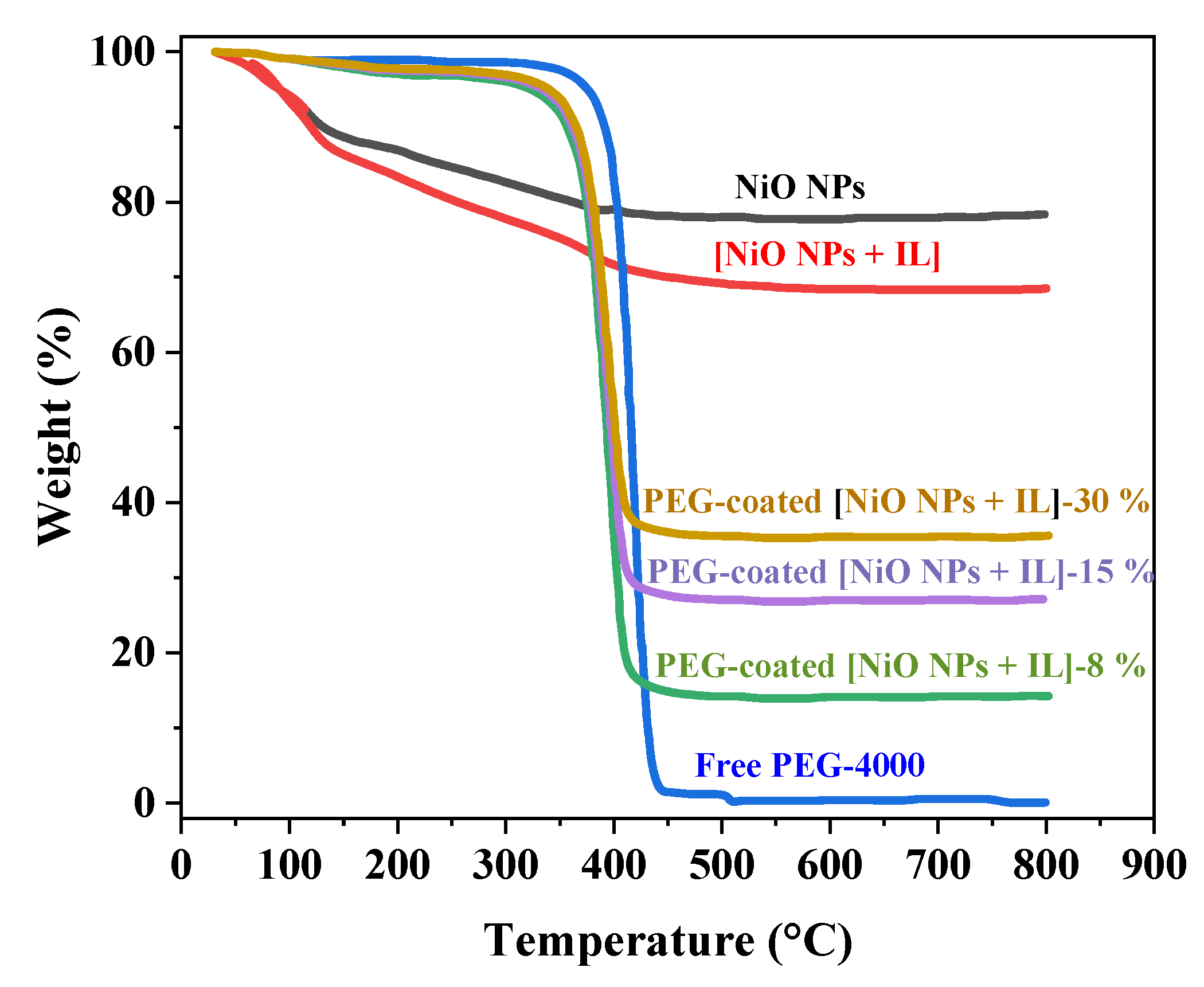

3.8. TGA Analysis

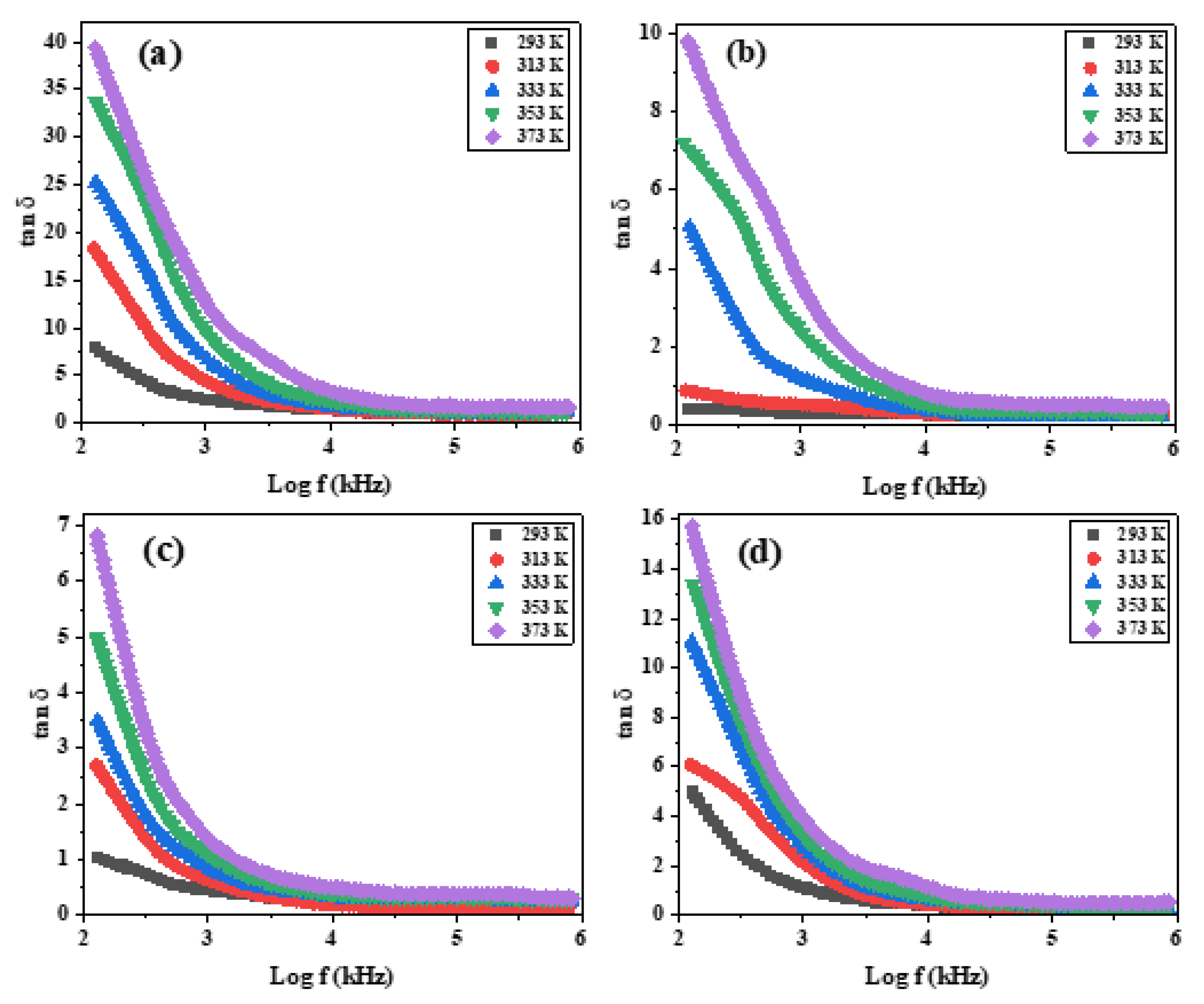

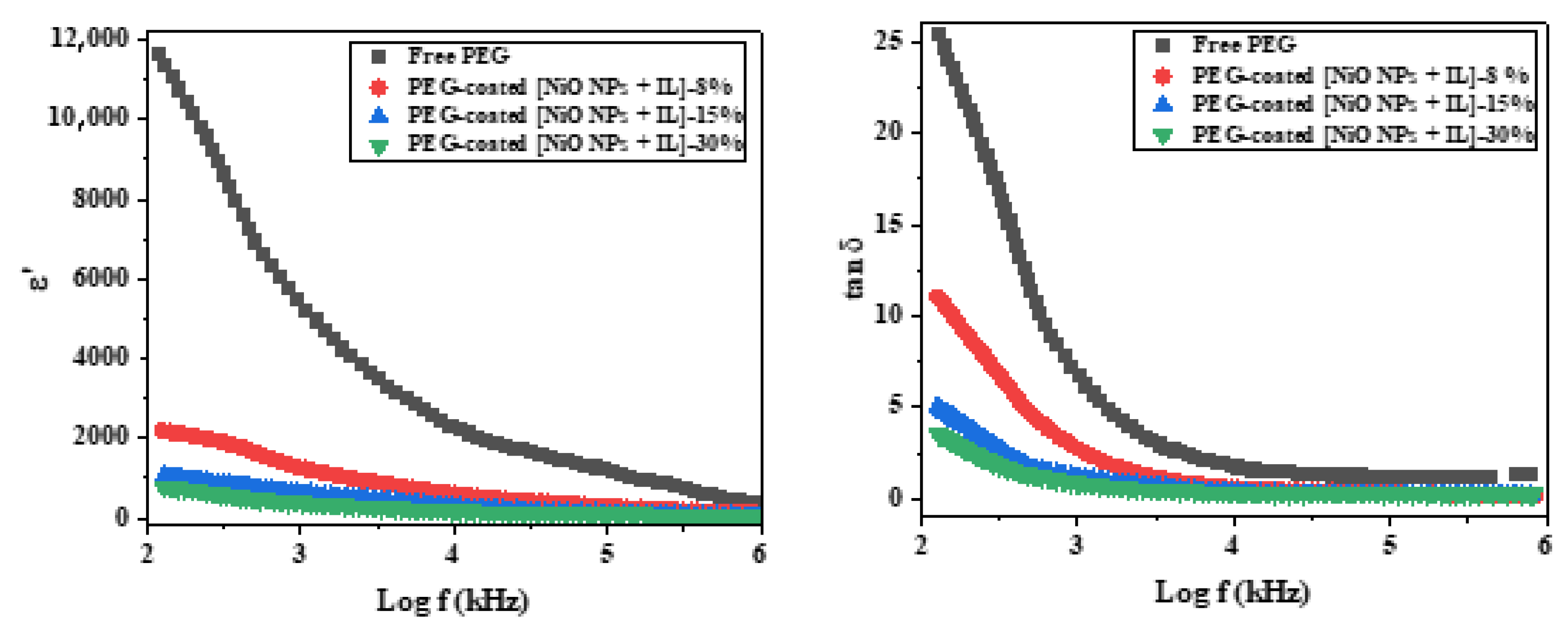

3.9. AC Conductivity and Dielectric Proprieties of PEG-Coated [NiO NPs + IL]

3.10. Stability

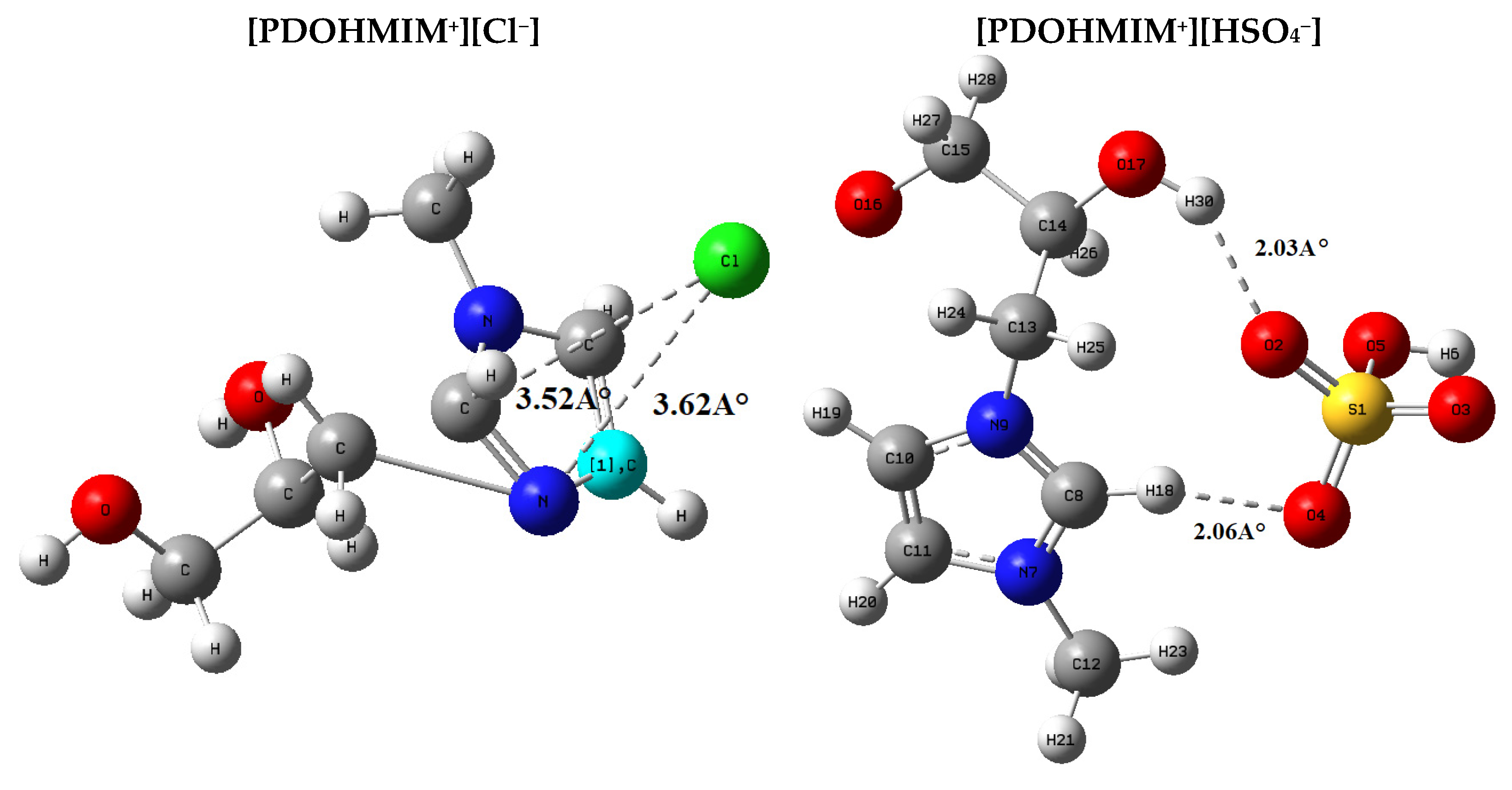

3.11. Geometry

3.12. Orbital Analysis

3.13. Electrostatic Stabilization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Comanescu, C. Magnetic nanoparticles: Current advances in nanomedicine, drug delivery and MRI. Chemistry 2022, 4, 872–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paravannoor, A.; Nair, S.V.; Pattathil, P.; Manca, M.; Balakrishnan, A. High voltage supercapacitors based on carbon-grafted NiO nanowires interfaced with an aprotic ionic liquid. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 6092–6095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsalme, A.; Alsaeedi, H.; Altowairqi, M.F.; Khan, R.A.; Alharbi, G.M.; Alhamed, A.A. Sol-gel synthesized nickel-oxide-based fabrication of Arsenic (As3+) sensor. Inorganics 2023, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Guan, X. HMT-controlled synthesis of mesoporous NiO hierarchical nanostructures and their catalytic role towards the thermal decomposition of ammonium perchlorate. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morejón Aguila, G.L.; Rodríguez Santillán, J.L.; Poznyak, T.; Cruz Narváez, Y.; Mendoza León, H.F.; Lartundo Rojas, L.; Ramos Torres, C.J.; Castro Arellano, J.J. Naproxen Degradation Using NiO Synthesized via Ultrasonic Spray Pyrolysis on Ni–Fe Foam by Ozone. Catalysts 2025, 15, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhou, X.; Wang, B.; Yang, T.; Yang, J.; Jia, N.; Zhang, M. Ni/Ce0.2Zr0.8O2 Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane: Effects of Surfactant Amount on the Support Structure and Properties. Materials 2025, 18, 4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duraisamy, N.; Numan, A.; Fatin, S.O.; Ramesh, K.; Ramesh, S. Facile sonochemical synthesis of nanostructured NiO with different particle sizes and its electrochemical properties for supercapacitor application. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 471, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeFrates, K.; Markiewicz, T.; Gallo, P.; Rack, A.; Weyhmiller, A.; Jarmusik, B.; Hu, X. Protein polymer-based nanoparticles: Fabrication and medical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabliov, C.M.; Astete, C.E. Polymeric nanoparticles for food applications. In Nanotechnology and Functional Foods; Sabliov, C.M., Chen, H., Yada, R.Y., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 272–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nahrawy, A.M.; Ali, A.I.; Abou Hammad, A.B.; Youssef, A.M. Influences of Ag-NPs doping chitosan/calcium silicate nanocomposites for optical and antibacterial activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 93, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belhocine, M.; Haouzi, A.; Ammari, A.; Chaker, Y.; Bassou, G. On the effect of Benzethonium intercalation process: Structural and dielectric properties of exchanged montmorillonite. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 577, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoroh, D.O.; Ozuomba, J.; Aisida, S.O.; Asogwa, P.U. Thermal treated synthesis and characterization of polyethylene glycol (PEG) mediated zinc ferrite nanoparticles. Surf. Interfaces 2019, 16, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Aisida, S.O.; Akpa, P.A.; Ahmad, I.; Maaza, M.; Ezema, F.I. Influence of PVA, PVP and PEG doping on the optical, structural, morphological and magnetic properties of zinc ferrite nanoparticles produced by thermal method. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2019, 571, 130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Aisida, S.O.; Ahmad, I.; Ezema, F.I. Effect of calcination on the microstructural and magnetic properties of PVA, PVP and PEG assisted zinc ferrite nanoparticles. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2020, 579, 411907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisida, S.O.; Akpa, P.A.; Ahmad, I.; Zhao, T.; Maaza, M.; Ezema, F.I. Bio-inspired encapsulation and functionalization of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 122, 109371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umut, E. Surface Modification of Nanoparticles Used in Biomedical Applications. Modern Surface Engineering Treatments. 2013. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=le-gDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA185&dq=Umut,+E.+(2013).+Surface+modification+of+nanoparticles+used+in+biomedical+applications.+Modern+surface+engineering+treatments,+20,+185-208.&ots=Q53pGoVrzE&sig=ehNX05gppSZRG5ytC7nlxXx-6aA (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Aslani, A.; Oroojpour, V.; Fallahi, M. Sonochemical synthesis, size controlling and gas sensing properties of NiO nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 4056–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H.A.; Bouafia, A.; Laouini, S.E.; Laib, I.; Salmi, C.; Alharthi, F.; Menaa, F. PEG-Modified NiFe2O4 Nanocomposites: Synthesis, Characterization, and Multifunctional Biomedical Applications in Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, Photoprotective, Antiemolytic, and Antibacterial Therapies. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2025, 39, e70212. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi, H.S.; Alshrefi, S.M.; Dhabian, S.Z.; Mutar, M.A.; Lazim, H.G. Synthesis as Well as Characterization of New PEG-Coated Nanoparticles for Biomedical Application. J. Nanostruct 2024, 14, 1252–1260. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, J.A.; Lawrance, G.A.; McCluskey, A. ‘Green’leaching: Recyclable and selective leaching of gold-bearing ore in an ionic liquid. Green Chem. 2004, 6, 313–315. [Google Scholar]

- Taubert, A.; Li, Z. Inorganic materials from ionic liquids. Dalton Trans. 2007, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-W.; Zhu, Y.-J. Shape-controlled synthesis of zinc oxide by microwave heating using an imidazolium salt. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2004, 7, 1003–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Recent Advances in Ionic Liquids for Synthesis of Inorganic Nanomaterials. Curr. Nanosci. 2005, 1, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Li, N.; Zheng, L.; Li, G.; Yu, L. Synthesis of Well-Dispersed NiO Nanoparticles with a Room Temperature Ionic Liquid. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2008, 29, 1103–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Niimi, S.; Suzuki, N.; Inui, M.; Yukawa, H. Metabolic engineering of 1,2-propanediol pathways in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 90, 1721–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankaj, S.K.; Misra, N.N.; Cullen, P.J. Kinetics of tomato peroxidase inactivation by atmospheric pressure cold plasma based on dielectric barrier discharge. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2013, 19, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Jiménez-Aberasturi, O.; Ochoa-Gómez, J.R.; Pesquera-Rodríguez, A.; Ramírez-López, C.; Alonso-Vicario, A.; Torrecilla-Soria, J. Solvent-free synthesis of glycerol carbonate and glycidol from 3-chloro-1,2-propanediol and potassium (hydrogen) carbonate. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 1663–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Gómez, J.R.; Gómez-Jiménez-Aberasturi, O.; Ramírez-López, C.A.; Nieto-Mestre, J.; Maestro-Madurga, B.; Belsué, M. Synthesis of glycerol carbonate from 3-chloro-1,2-propanediol and carbon dioxide using triethylamine as both solvent and CO2 fixation–activation agent. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 175, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliaro, M.; Rossi, M. Glycerol: Properties and production. Future Glycerol 2010, 2, 1À28. [Google Scholar]

- Papini, S.; Andréa, M.M. Enhanced degradation of metalaxyl in gley humic and dark red latosol. Rev. Bras. De Ciência Do Solo 2000, 24, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rafiee, H.R.; Frouzesh, F. The effect of ionic liquid 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium hydrogen sulfate on thermodynamic properties of aqueous lithium nitrate solutions at different temperatures and ambient pressure. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 237, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althumayri, K.; Eldesoky, A.M.; Alqahtani, N.F.; Ismail, L.A.; Elshaarawy, R.F.; Zakrya, R. Synthesis of tunable aryl alkyl ionic liquid-stabilized NiO nanoparticles supported reduced graphene oxide as highly efficient hole transport layer in perovskite solar cell. Results Chem. 2025, 18, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaker, Y.; Ilikti, H.; Debdab, M.; Moumene, T.; Belarbi, E.H.; Wadouachi, A.; Abbas, O.; Khelifa, B.; Bresson, S. Synthesis and characterization of 1-(hydroxyethyl)-3-methylimidazolium sulfate and chloride ionic liquids. J. Mol. Struct. 2016, 1113, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaker, Y.; Benabdellah, A.; Debdab, M.; Belarbi, E.H.; Haddad, B.; Kadari, M.; Van Nhien, A.N.; Zoukel, A.; Chemrak, M.A.; Bresson, S. Synthesis, characterization, and dielectric properties of 1,2-(propanediol)-3-methylimidazolium chloride, hydrogenosulfate, and dihydrogenophosphate ionic liquids. Stud. Eng. Exact Sci. 2024, 5, e10517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaoui, T.; Debdab, M.; Haddad, B.; Belarbi, E.H.; Chaker, Y.; Rahmouni, M.; Bresson, S.; Baeten, V. Synthesis, vibrational and thermal properties of new functionalized 1-(2-hydroxyethyl)-3-methylimidazolium dihydrogenophosphate ionic liquid. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1236, 130264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, I.; Dizaji, H.R.; Aghazadeh, M. Preparation, characterization and PEGylation of superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles from ethanol medium via cathodic electrochemical deposition (CED) method. Mater. Res. Express 2016, 3, 095022. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, A.; Lee, E.; Chen, R.; Chae, S.R.; Sun, Y.; Diao, J. Understanding the role of polyethylene glycol coating in reducing the subcellular toxicity of MXene nanoparticles using a large multimodal model. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 35, 102372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Ahmad, B.; Hayat, K.; Ullah, F.; Sfina, N.; Elhadi, M.; Khan, A.A.; Husain, M.; Rahman, N. Synthesis of ZnO and PEG-ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) with controlled size for biological evaluation. R. Soc. Chem. 2024, 14, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, S.V.; Nikam, D.S.; Khot, V.M.; Mali, S.S.; Hong, C.K.; Pawar, S.H. PVA and PEG functionalised LSMO nanoparticles for magnetic fluid hyperthermia application. Mater. Charact. 2015, 102, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghazadeh, M.; Ganjali, M.R. One-step electro-synthesis of Ni2+ doped magnetite nanoparticles and study of their supercapacitive and superparamagnetic behaviors. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 4981–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, G. Metal organic framework supported surface modification of synthesized nickel/nickel oxide nanoparticles via controlled PEGylation for cytotoxicity profile against MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines via docking analysis. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1287, 135445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebur, Q.; Hashim, A.; Habeeb, M. Structural, AC electrical and optical properties of (polyvinyl alcohol–polyethylene oxide–aluminum oxide) nanocomposites for piezoelectric devices. Egypt. J. Chem. 2019, 62, 719–734. [Google Scholar]

- Bafna, M.; Garg, N.; Gupta, A.K. Variation of dielectric properties & AC conductivity with frequency and composition for stannous chloride_PMMA composite films. J. Emerg. Technol. Innov. Res. 2018, 5, 494–497. [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy, T.; Ahmed, M.T. Dielectric relaxation spectroscopy and AC conductivity of doped poly (Vinyl Alcohol). Int. J. Mater. Phys. 2015, 6, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Hu, W.; Han, S. First-principles calculation of the elastic constants, the electronic density of states and the ductility mechanism of the intermetallic compounds: YAg, YCu and YRh. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2008, 403, 3792–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonscher, A.K. The ‘universal’dielectric response. Nature 1977, 267, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S.; Clark, T. Halogen bonding and other σ-hole interactions: A perspective. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 11178–11189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrone, A.; Cimino, P.; Donati, G.; Hratchian, H.P.; Frisch, M.J.; Rega, N. On the Driving Force of the Excited-State Proton Shuttle in the Green Fluorescent Protein: A Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (TD-DFT) Study of the Intrinsic Reaction Path. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 4925–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyss, J.; Ledoux, I. Nonlinear optics in multipolar media: Theory and experiments. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 77–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, C.; Welton, T. Solvents and Solvent Effects in Organic Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.G.; Wang, N.N.; Yu, Z.W. The hydrogen bonding interactions between the ionic liquid 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium ethyl sulfate and water. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 4747–4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| [NiO NPs + IL], Wavenumber (cm−1) | [PDOHMIM+][HSO4−] Wavenumber (cm−1) | Assignment |

|---|---|---|

| 2948–2885 | 3050–2851 | C–H (υstretching) |

| 1771–1421 | C–H2 (υstretching) | |

| 1467–1470 | C–H2 (υstretching) | |

| 1348–1410 | C–H2 (υstretching) | |

| 1284–1286 | 1374–1158 | C–O–C (υbending) |

| 1110–1656 | C–O–C (υbending) | |

| 955–842 | 1018–746 | C–H (υwagging) |

| 1110–1144 | C–C (υstretching) | |

| 1066–1110 | C–O–H (υstretching) | |

| 3180–3070 | O–H (υwagging) | |

| 849 | N–S (υwagging) | |

| 1212 | S–O (υwagging) |

| Content of [NiO NPs + IL] Coated by PEG (%) | Dielectric Parametres | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σAC | ε′ | tan (δ) | ||

| Free PEG | S values | 4.38 × 10−9 | 1.2 × 104 | 25.4 |

| 8 | 0.394 | 3.65 × 10−5 | 2.20 × 103 | 11.2 |

| 15 | 0.368 | 3.95 × 10−5 | 1.13 × 103 | 4.95 |

| 30 | 0.309 | 4.92 × 10−5 | 6.8 × 103 | 3.65 |

| Total Electronic Energy (a.u). | |

|---|---|

| [PDOHMIM+][Cl−] | −994.858323057 |

| [PDOHMIM+][HSO4−] | −1229.0517 |

| EHOMO | ELUMO | Eg | |

|---|---|---|---|

| [PDOHMIM+][Cl−], | −6.8 eV | −1.6 eV | 5.2 eV |

| [PDOHMIM+][HSO4−] | −7.8 eV | −2.3 eV | 5.5 eV |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dekkiche, G.; Chaker, Y.; Benabdellah, A.; Belarbi, E.-H.; Harid, N.; Hatti, M.; Zoukel, A.; Rabehi, A.; Habib, M. PEG-Coated Nanostructured NiO Synthesized Sonochemically in 1,2-(Propanediol)-3-methylimidazolium Hydrogen Sulfate Ionic Liquid: DFT, Structural and Dielectric Characterization. Chemistry 2025, 7, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060194

Dekkiche G, Chaker Y, Benabdellah A, Belarbi E-H, Harid N, Hatti M, Zoukel A, Rabehi A, Habib M. PEG-Coated Nanostructured NiO Synthesized Sonochemically in 1,2-(Propanediol)-3-methylimidazolium Hydrogen Sulfate Ionic Liquid: DFT, Structural and Dielectric Characterization. Chemistry. 2025; 7(6):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060194

Chicago/Turabian StyleDekkiche, Ghania, Yassine Chaker, Abdelkader Benabdellah, EL-Habib Belarbi, Noureddine Harid, Mustapha Hatti, Abdelhalim Zoukel, Abdelaziz Rabehi, and Mustapha Habib. 2025. "PEG-Coated Nanostructured NiO Synthesized Sonochemically in 1,2-(Propanediol)-3-methylimidazolium Hydrogen Sulfate Ionic Liquid: DFT, Structural and Dielectric Characterization" Chemistry 7, no. 6: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060194

APA StyleDekkiche, G., Chaker, Y., Benabdellah, A., Belarbi, E.-H., Harid, N., Hatti, M., Zoukel, A., Rabehi, A., & Habib, M. (2025). PEG-Coated Nanostructured NiO Synthesized Sonochemically in 1,2-(Propanediol)-3-methylimidazolium Hydrogen Sulfate Ionic Liquid: DFT, Structural and Dielectric Characterization. Chemistry, 7(6), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry7060194