Enhancement of Nonlinear Optical Rectification in a 3D Elliptical Quantum Ring Under a Transverse Electric Field: The Morphology, Temperature, and Pressure Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

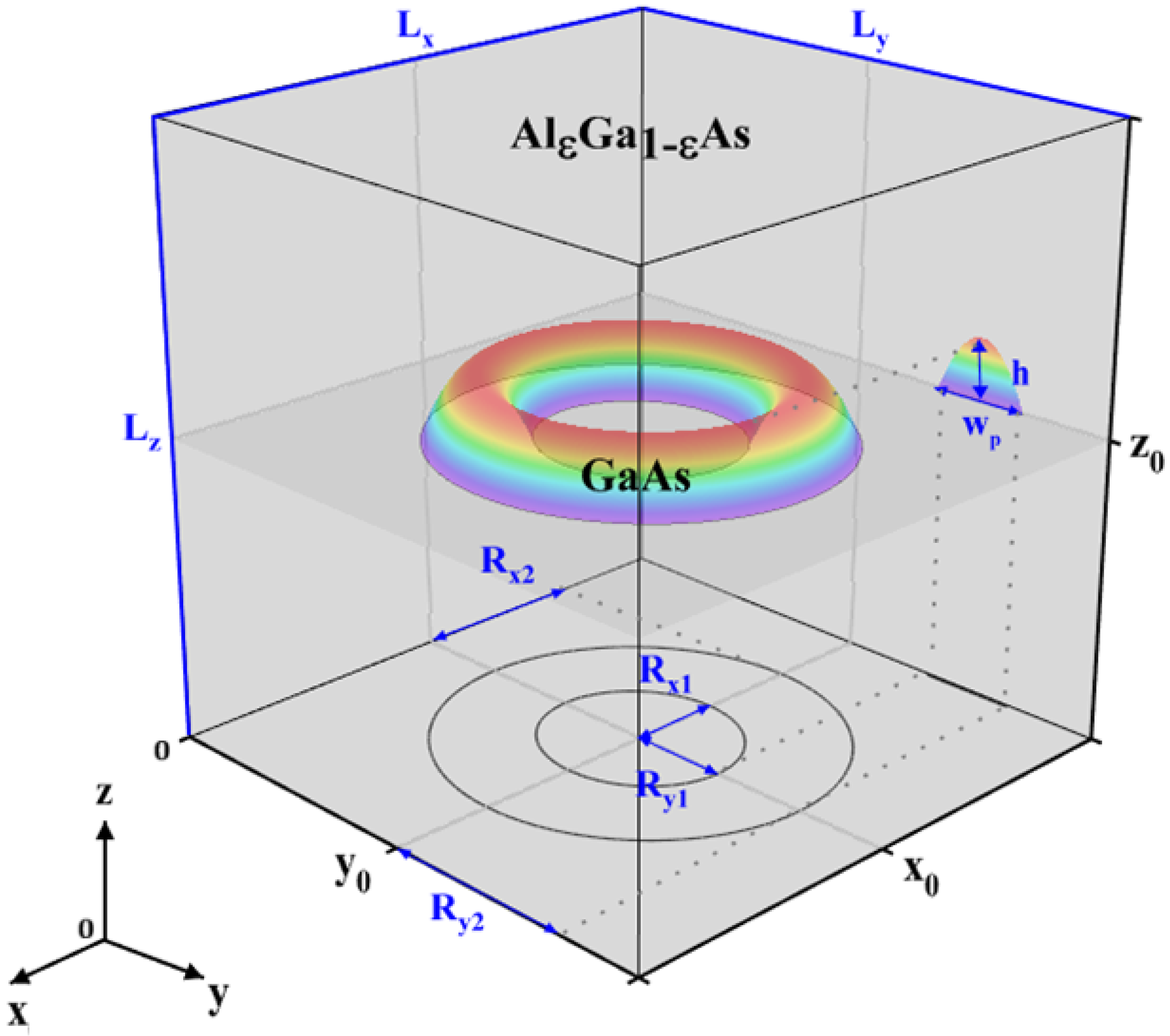

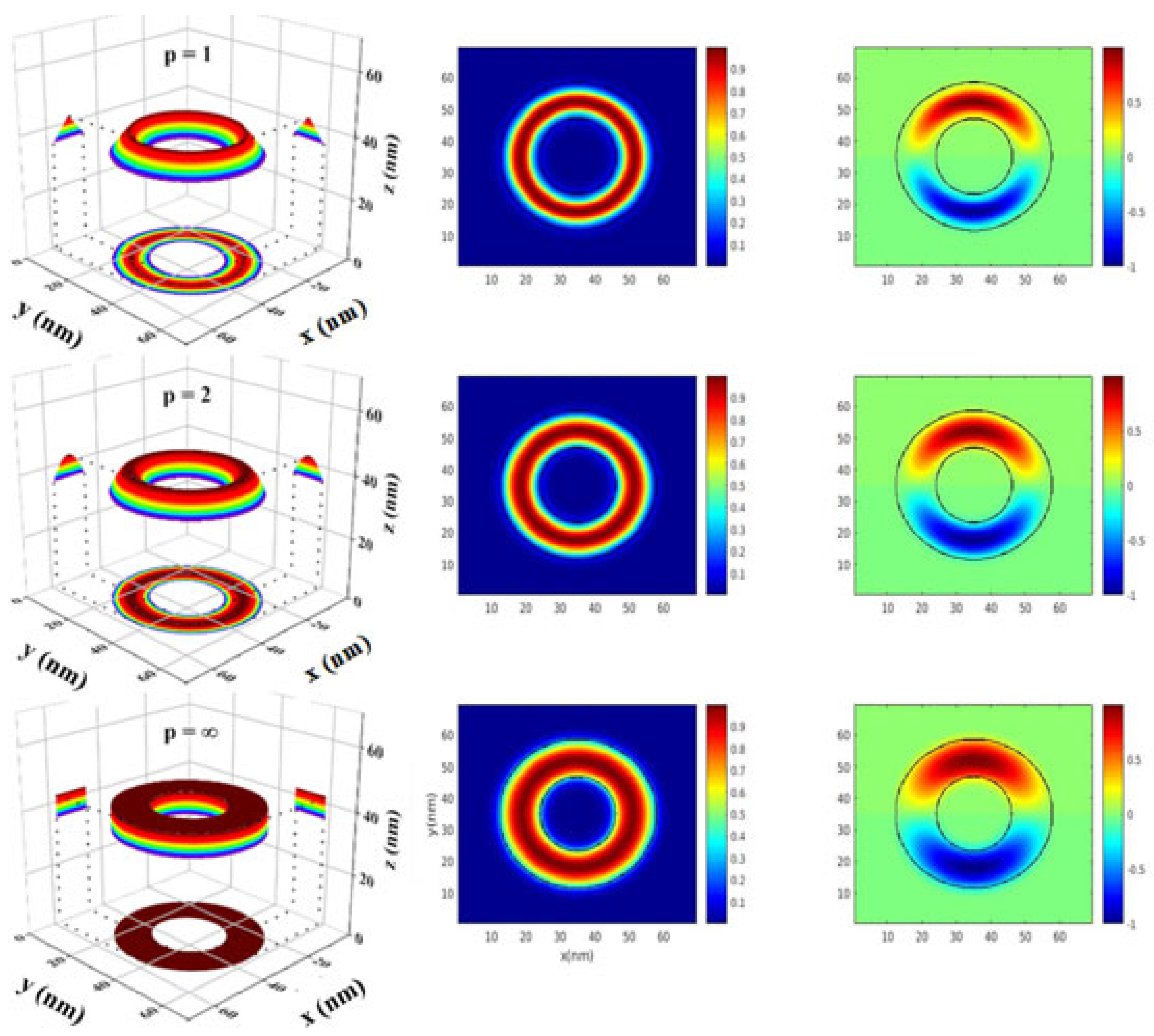

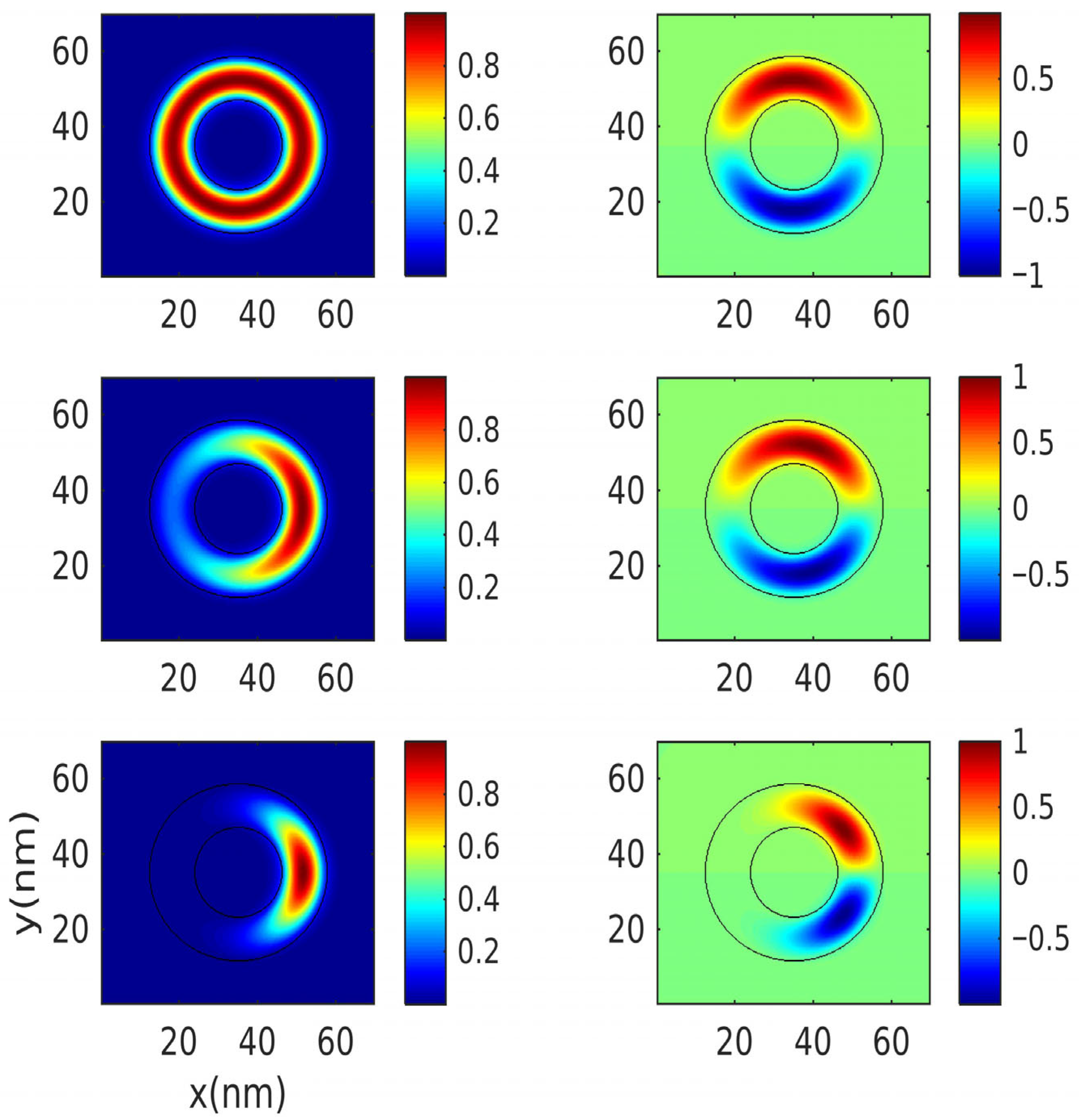

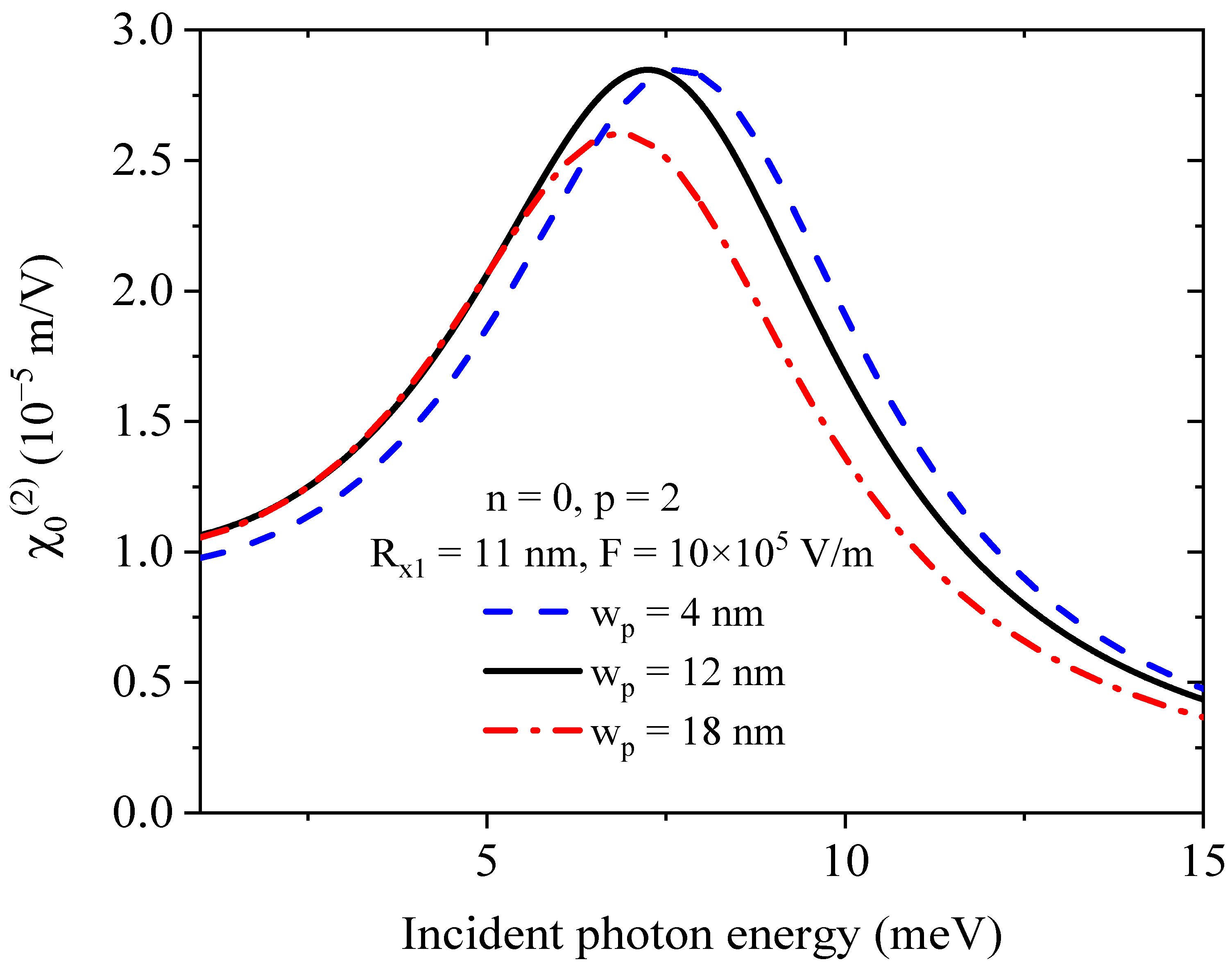

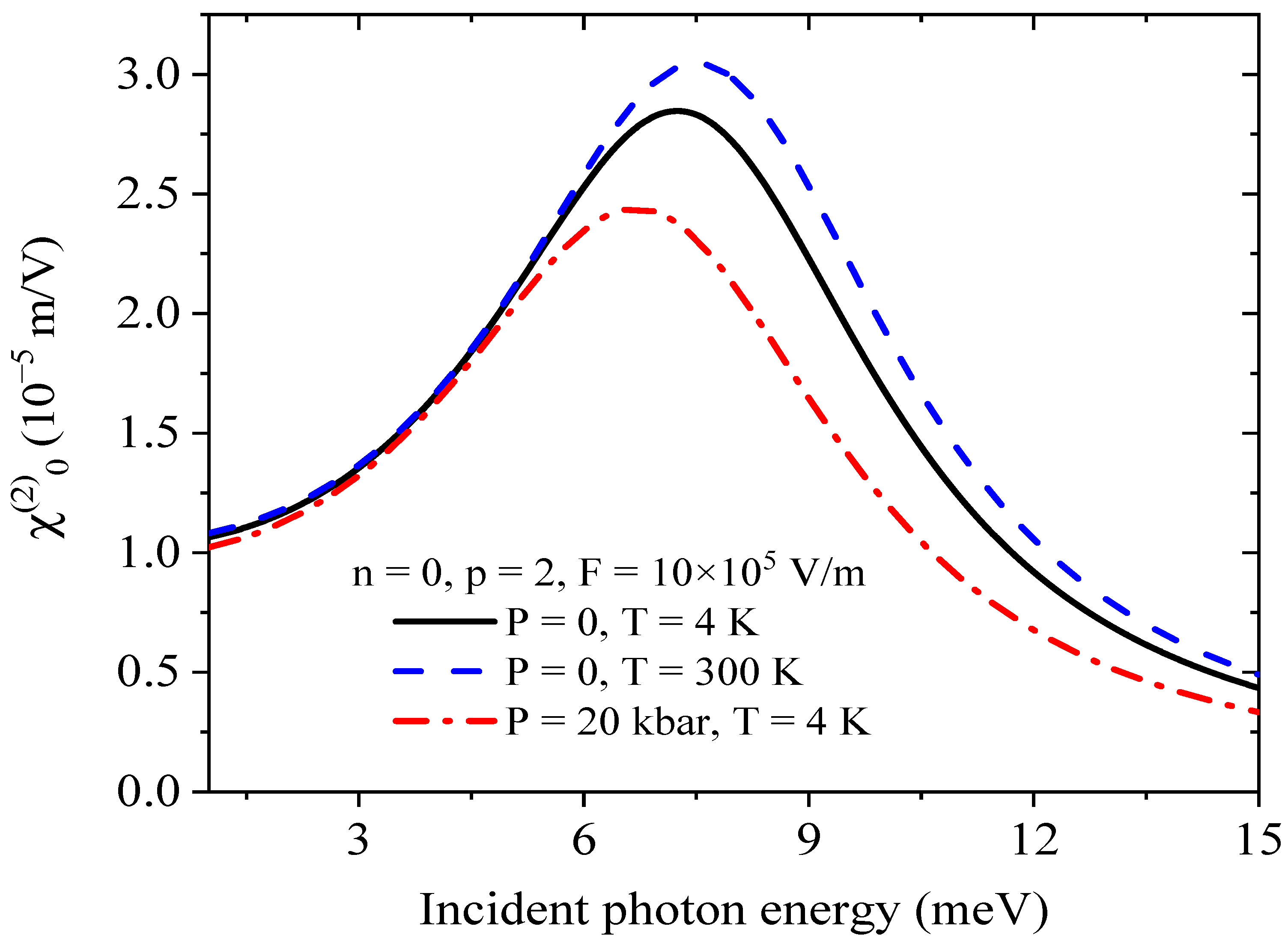

2. Theory

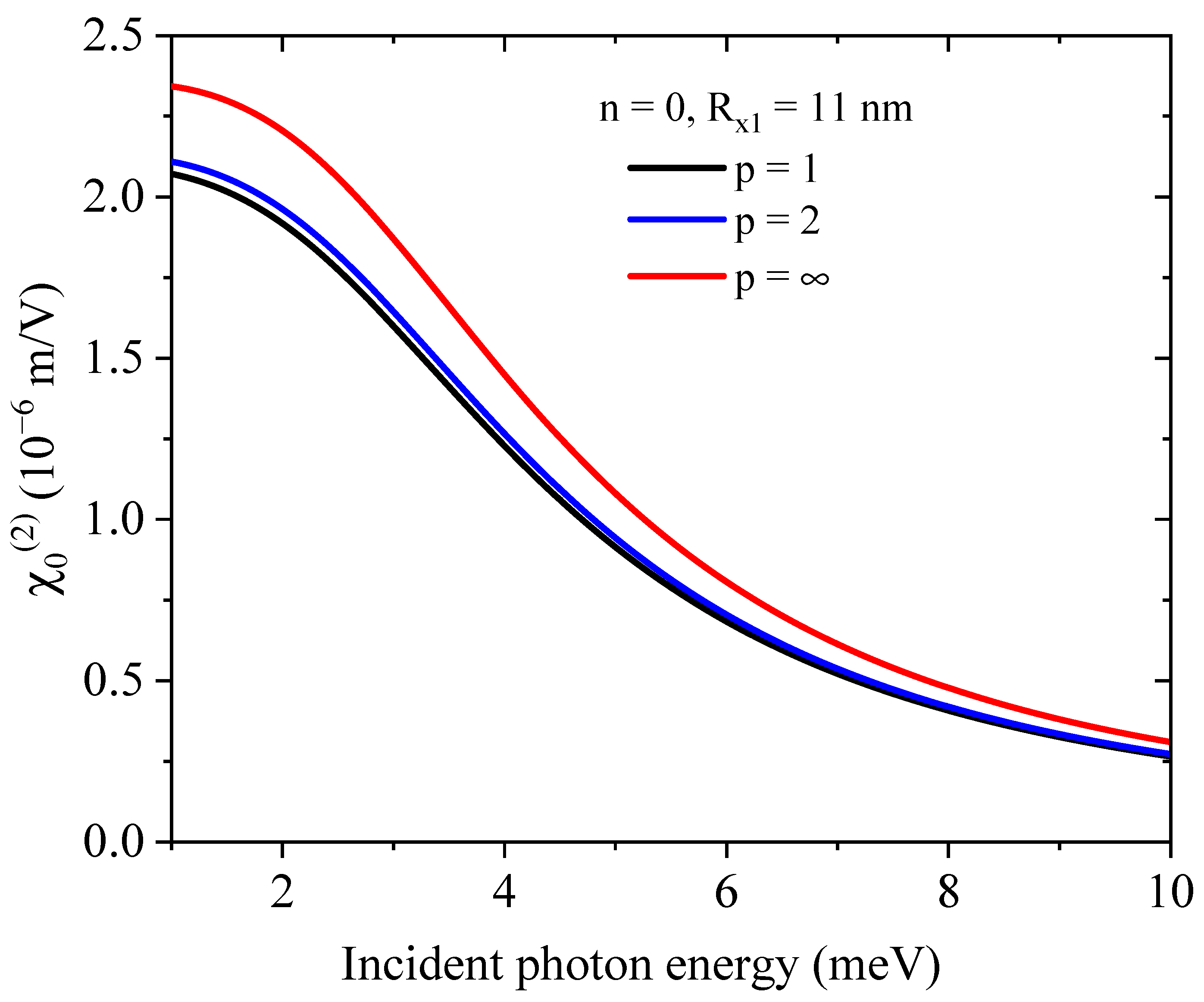

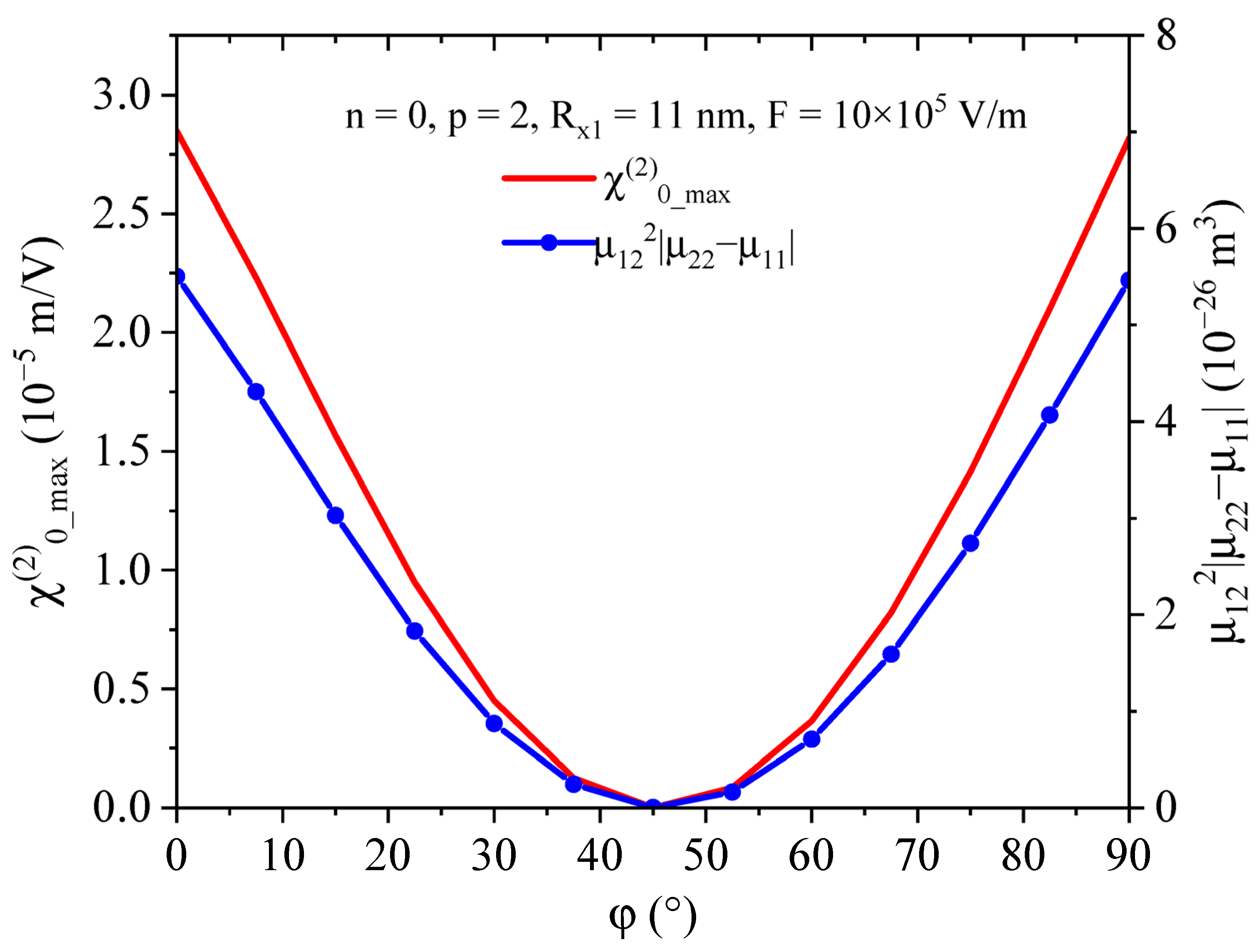

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cc | complex conjugate |

| EWFD | electron wave function distribution |

| FDM | Finite Difference Method |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| G.F | geometrical factor |

| MBE | molecular beam epitaxy |

| NOR | nonlinear optical rectification |

| OR | optical rectification |

| QD | quantum dot |

| QR | quantum ring |

| SHG | second harmonic generation |

| THG | third harmonic generation |

| 2D, 3D | two/three-dimensional |

References

- Maouhoubi, I.; Chouef, S.; Mommadi, O.; En-nadir, R.; Zorkani, I.; Hassani, A.O.T.; El Moussaouy, A.; Anouar, J. Computational investgation of the optical properties of GaAs/Ga0.7Al0.3 core/shell thin film for optoelectronic applications: Under tuned external field and impurity effects. Mater. Sci. Engin. B 2024, 299, 116988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomin, V.M. NanoScience and Technology. In Physics of Quantum Rings, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.M.; Medeiros-Ribeiro, G.; Schmidt, K.; Ngo, T.; Feng, J.L.; Lorke, A.; Kotthaus, J.; Petroff, P.M. Intermixing and shape changes during the formation of InAs self-assembled quantum dots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1997, 71, 2014–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghramyan, H.M.; Barseghyan, G.; Kirakosyan, A.A.; Restrepo, R.L.; Duque, C.A. Linear and nonlinear optical absorption coefficients in GaAs/Ga1-xAlxAs concentric double quantum rings: Effects of hydrostatic pressure and aluminum concentration. J. Lumin. 2013, 134, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Y.K.; Garcia, R. Advanced oxidation scanning probe lithography. Nanotechnology 2017, 28, 142003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, A.D.B.; da Silva, E.C.F.; Quivy, A.A.; Bindilatti, V.; de Aquino, V.M.; Dias, I.F.L. The influence of different indium-composition profiles on the electronic structure of lens-shaped InxGa1−xAs quantum dots. J. Phys. D 2012, 45, 225104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorke, A.; Blossey, R.; Garcia, J.M.; Bichler, M.; Abstreiter, G. Morphological transformation of InyGa1−yAs islands, fabricated by Stranski–Krastanov growth. Mater. Sci. Engin. B 2002, 88, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzmann, B.B.V.; Vliem, J.F.; Maaskant, D.N.; Post, L.C.; Li, C.; Bals, S.; Vanmaekelbergh, D. From CdSe nanoplatelets to quantum rings by thermochemical edge reconfiguration. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 6853–6859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, T.; Mano, T.; Ochiai, T.; Sanguinetti, S.; Sakoda, K.; Kido, G.; Koguchi, N. Optical transitions in quantum ring complexes. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 205301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, R.L.; Morales, A.L.; Martínez-Orozco, J.C.; Baghramyan, H.M.; Barseghyan, M.G.; Mora-Ramos, M.E.; Duque, C.A. Impurity-related nonlinear optical properties in delta-doped quantum rings: Electric field effects. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2014, 453, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, E.; Khoshnoud, D.S.; Naeimi, A.S. Non-linear optical properties of nanoscale elliptical ring-shaped at the presence of Rashba spin–orbit interaction and magnetic field. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Phys. Process. 2019, 125, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. Studies on the third-harmonic generations in a quantum ring with magnetic field. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2023, 138, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.S.; Wang, S.Y.; Lee, C.P.; Lo, M.C. Characteristics of In (Ga)As quantum ring infrared photodetectors. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 105, 034504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.M.; Jr, V.L.C.; Portnoi, M.E.; Römer, R.A. Exciton storage in a nanoscale Aharonov–Bohm ring with electric field tuning. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 096405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejan, D.; Stan, C. Impurity and geometry effects on the optical rectification spectra of quasi-elliptical double quantum rings. Phys. E Low-dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2023, 147, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Guo, W.; Bhattacharya, P.; Ariyawansa, G.; Perera, A.G.U. A quantum ring terahertz detector with resonant tunnel barriers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 101115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, N.F.; Otten, M.; Fedin, I.; Talapin, D.; Cygorek, M.; Hawrylak, P.; Korkusinski, M.; Gray, S.; Hartschuh, A. Uniaxial transition dipole moments in semiconductor quantum rings caused by broken rotational symmetry. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestri, M.; Sahoo, A.; Ferrante, C.; Benassi, P.; Ciattoni, A.; Marin, A. Doubly resonant third-harmonic generation in near-zero-index heterogeneous nanostructures. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 110, 023524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaouane, M.; Ed-Dahmouny, A.; Fakkahi, A.; Arraoui, R.; El-Bakkari, K.; Azmi, H.; Sali, A.; Ungan, F. Investigation of nonlinear optical rectification within multilayer wurtzite InGaN/GaN cylindrical quantum dots under the impact of temperature and pressure. Opt. Mater. 2024, 147, 114711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, A.; Azargoshasb, T.; Niknam, E. Second and third harmonic generations of a quantum ring with Rashba and Dresselhaus spin-orbit couplings: Temperature and Zeeman effects. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2017, 523, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazwani, H.A.; Hasanirokh, K.; Yvaz, A. Theoretical studies on the effects of pressure, temperature, and aluminum concentration on the optical absorption, refractive index and group velocity within GaAs/Ga1− xAlxAs quantum ring in the presence of Rashba spin–orbit interaction. Opt. Quant. Electron. 2024, 56, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejan, D.; Stan, C. Nonlinear optical rectification, second and third harmonic generation in quantum dot—Double quantum rings: Electric field and geometry effects. Opt. Quant. Electron. 2025, 57, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayrac, M.; Acıkgoz, L.; Tuzemen, A.T.; Mora-Ramos, M.E. Exploring nonlinear optical properties of single δ-doped quantum wells: Influences of position-dependent mass, temperature, and hydrostatic pressure. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2025, 140, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W. The nonlinear optical rectification coefficient in a hydrogenic quantum ring. Phys. Scr. 2012, 85, 055702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, E.C.; Bejan, D. Off-centre impurity-related nonlinear optical absorption, second and third harmonic generation in a two-dimensional quantum ring under magnetic field. Philos. Magaz 2017, 97, 20892107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, C.M.; Acosta, R.E.; Morales, A.L.; Mora-Ramos, M.E.; Restrepo, R.L.; Ojeda, J.H.; Kasapoglu, E.; Duque, C.A. Optical coefficients in a semiconductor quantum ring: Electric field and donor impurity effects. Opt. Mater. 2016, 60, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinasco, J.A.; Londono, M.A.; Kasapoglu, E.; Mora-Ramos, M.E.; Feddi, E.M.; Radu, A.; Kasapoglu, E.; Morales, A.L.; Duque, C.A. Optical absorption and electroabsorption related to, electronic and single dopant transitions in holey elliptical GaAs quantum dots. Phys. Status Sol. B 2018, 255, 1700470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, E.C.; Stan, C.; Bejan, D.; Cartoaje, C. Impurity and eccentricity effects on the nonlinear optical rectification in a quantum ring under lateral electric fields. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 122, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmand, S.E.; Rezaei, G.; Vaseghi, B. Impacts of external fields and Rashba and Dresselhaus spin-orbit interactions on the optical rectification, second and third harmonic generations of a quantum ring. Eur. Phys. J. B 2019, 92, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinasco, J.A.; Radu, A.; Kasapoglu, E.; Mora-Ramos, M.E.; Feddi, E.M.; Radu, A.; Kasapoglu, E.; Morales, A.L.; Duque, C.A. Effects of geometry on the electronic properties of semiconductor elliptical quantum rings. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Ramos, M.E.; Vinasco, J.A.; Radu, A.; Restrepo, R.L.; Morales, A.L.; Sahin, M.; Sierra-Ortega, J.; Escorcia-Salas, G.E.; Duque, C.A. Elliptical quantum rings with variable heights and under spin–orbit interactions. Condens. Matter 2023, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choubani, M.; Maaref, H.; Saidi, F. Nonlinear optical properties of lens-shaped core/shell quantum dots coupled with a wetting layer: Effects of transverse electric field, pressure, and temperature. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2020, 138, 109226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqraoun, E.; Sali, A.; Iqraoun, E.; Ezzarfi, A.; Mora-Ramos, M.E.; Duque, C.A. Simultaneous effects of temperature, pressure, polaronic mass, and conduction band non-parabolicity on a single dopant in conical GaAs-AlxGa1–x As quantum dots. Phys. Scr. 2021, 9, 065808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Orozco, J.C.; Mora-Ramos, M.E.; Duque, C.A. Nonlinear optical rectification and second and third harmonic generation in GaAs δ-FET systems under hydrostatic pressure. J. Lumin. 2012, 132, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Branis, S.V.; Baja, K.K. Exciton binding energy in a quantum wire in the presence of a magnetic field. J. Appl. Phys. 1995, 77, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baser, P.; Karki, H.D.; Demir, I.; Elagoz, S. The hydrostatic pressure and temperature effects on the binding energy of magnetoexcitons in cylindrical quantum well wires. Superlat. Microstruct. 2013, 63, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, S. GaAs, AlAs, and AlxGa1−xAs: Material parameters for use in research and device applications. J. Appl. Phys. 1985, 58, R1–R29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susa, N. Improvement in electroabsorption and the effects of parameter variations in the three—Step asymmetric coupled quantum well. J. Appl. Phys. 1993, 73, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bakkari, K.; Sali, A.; Iqraoun, E.; Rezzouk, A.; Es-Sbai, N.; Jamil, M.O. Effects of the temperature and pressure on the electronic and optical properties of an exciton in GaAs/Ga1−xAlxAs quantum ring. Phys. B Phys. Condens. Matter 2018, 538, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welber, B.; Cardona, M.; Kim, C.K.; Rodriguez, S. Dependence of the direct energy gap of GaAs on hydrostatic pressure. Phys. Rev. B 1975, 12, 5729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Shu, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, Z. Numerical analysis on quantum dots in-a-well structures by finite difference method. Superlattices Microstruct. 2013, 60, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samara, G.A. Temperature and pressure dependences of the dielectric constants of semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B 1983, 27, 3494–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhlouf, D.; Choubani, M.; Saidi, F.; Maaref, H. Applied electric and magnetic fields effects on the nonlinear optical rectification and the carrier’s transition lifetime in InAs/GaAs core/shell quantum dot. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 267, 124660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakkahi, A.; Sali, A.; Jaouane, M.; Arraoui, R.; Ed-Dahmouny, A. Investigation of the nonlinear optical rectification coefficient in a multilayered spherical quantum dot. Opt. Mater. 2022, 132, 112752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejan, D.; Stan, C. Geometry-tuned optical absorption spectra of the coupled quantum dot–double quantum ring structure. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benzerroug, N.; Choubani, K.; Rabha, M.B.; Choubani, M. Enhancement of Nonlinear Optical Rectification in a 3D Elliptical Quantum Ring Under a Transverse Electric Field: The Morphology, Temperature, and Pressure Effects. Physics 2025, 7, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/physics7040068

Benzerroug N, Choubani K, Rabha MB, Choubani M. Enhancement of Nonlinear Optical Rectification in a 3D Elliptical Quantum Ring Under a Transverse Electric Field: The Morphology, Temperature, and Pressure Effects. Physics. 2025; 7(4):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/physics7040068

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenzerroug, Nabil, Karim Choubani, Mohamed Ben Rabha, and Mohsen Choubani. 2025. "Enhancement of Nonlinear Optical Rectification in a 3D Elliptical Quantum Ring Under a Transverse Electric Field: The Morphology, Temperature, and Pressure Effects" Physics 7, no. 4: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/physics7040068

APA StyleBenzerroug, N., Choubani, K., Rabha, M. B., & Choubani, M. (2025). Enhancement of Nonlinear Optical Rectification in a 3D Elliptical Quantum Ring Under a Transverse Electric Field: The Morphology, Temperature, and Pressure Effects. Physics, 7(4), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/physics7040068