MalVis: Large-Scale Bytecode Visualization Framework for Explainable Android Malware Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

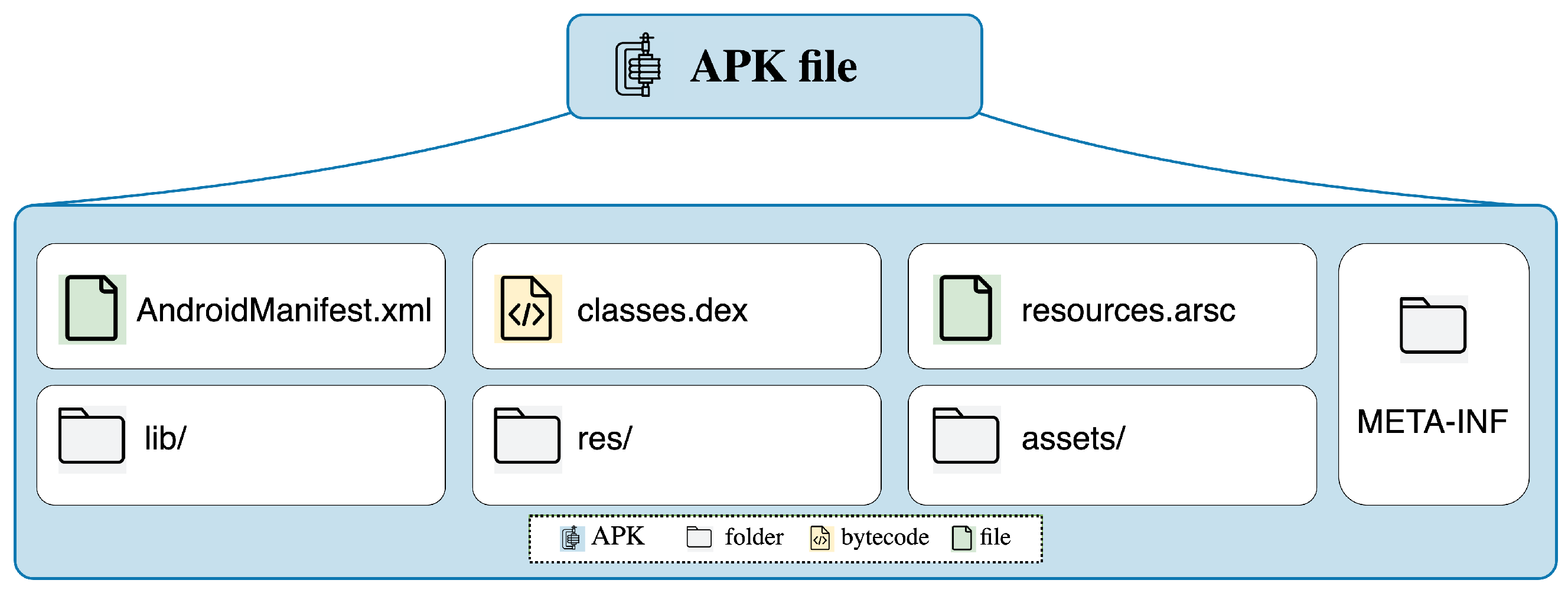

1.1. Overview of the Android APK File Structure

1.2. Contributions

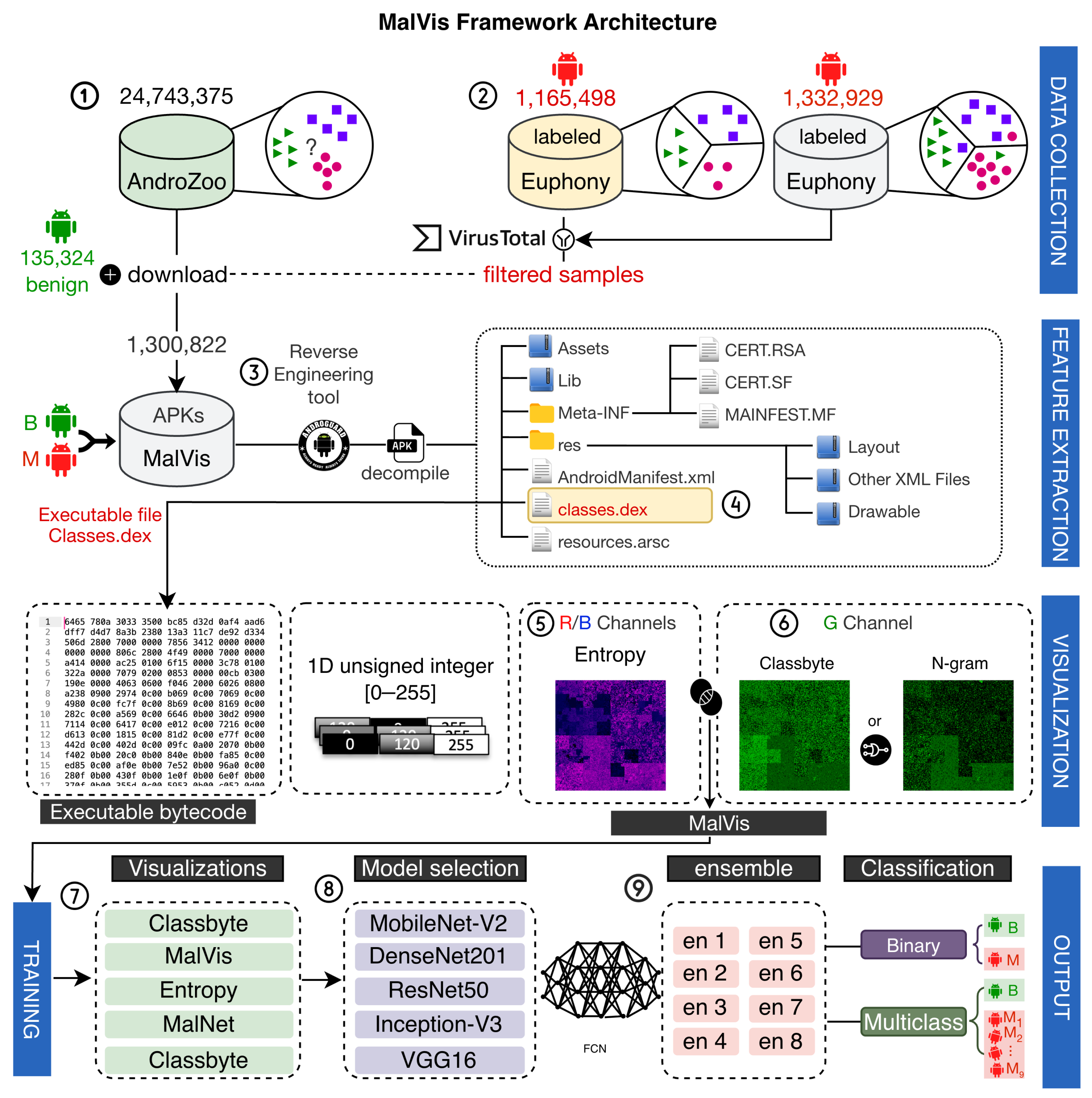

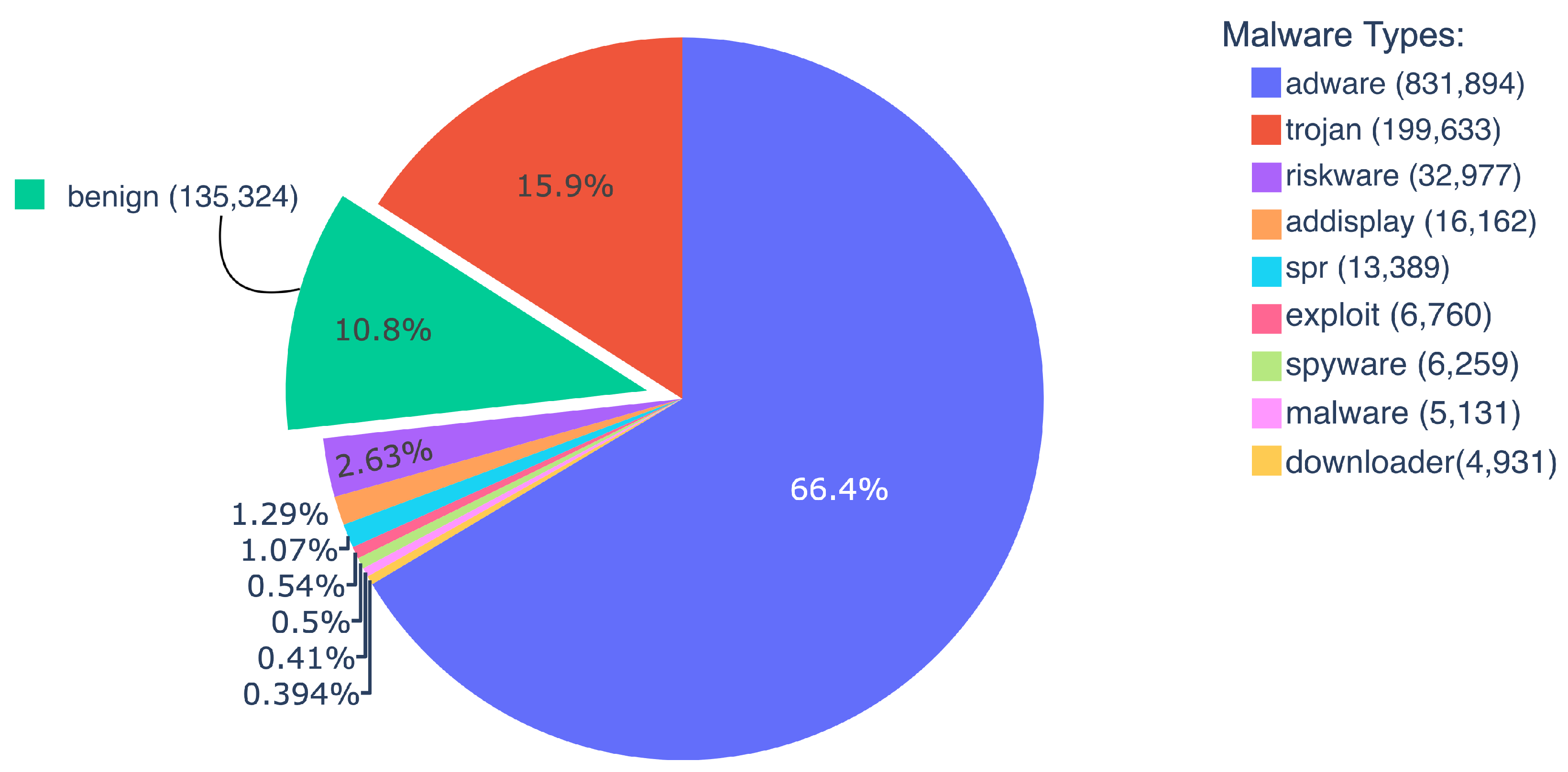

- MalVis Dataset: Introducing MalVis, the largest Android malware visualization dataset with over 1.3 million images across ten classes, including nine malware types and benign software that is accessible to the research community at (www.mal-vis.org, accessed on 2 October 2025). Scripts for generating these various visualization methods are publicly available on GitHub at the link (https://github.com/makkawysaleh/MalVis, accessed on 2 October 2025).

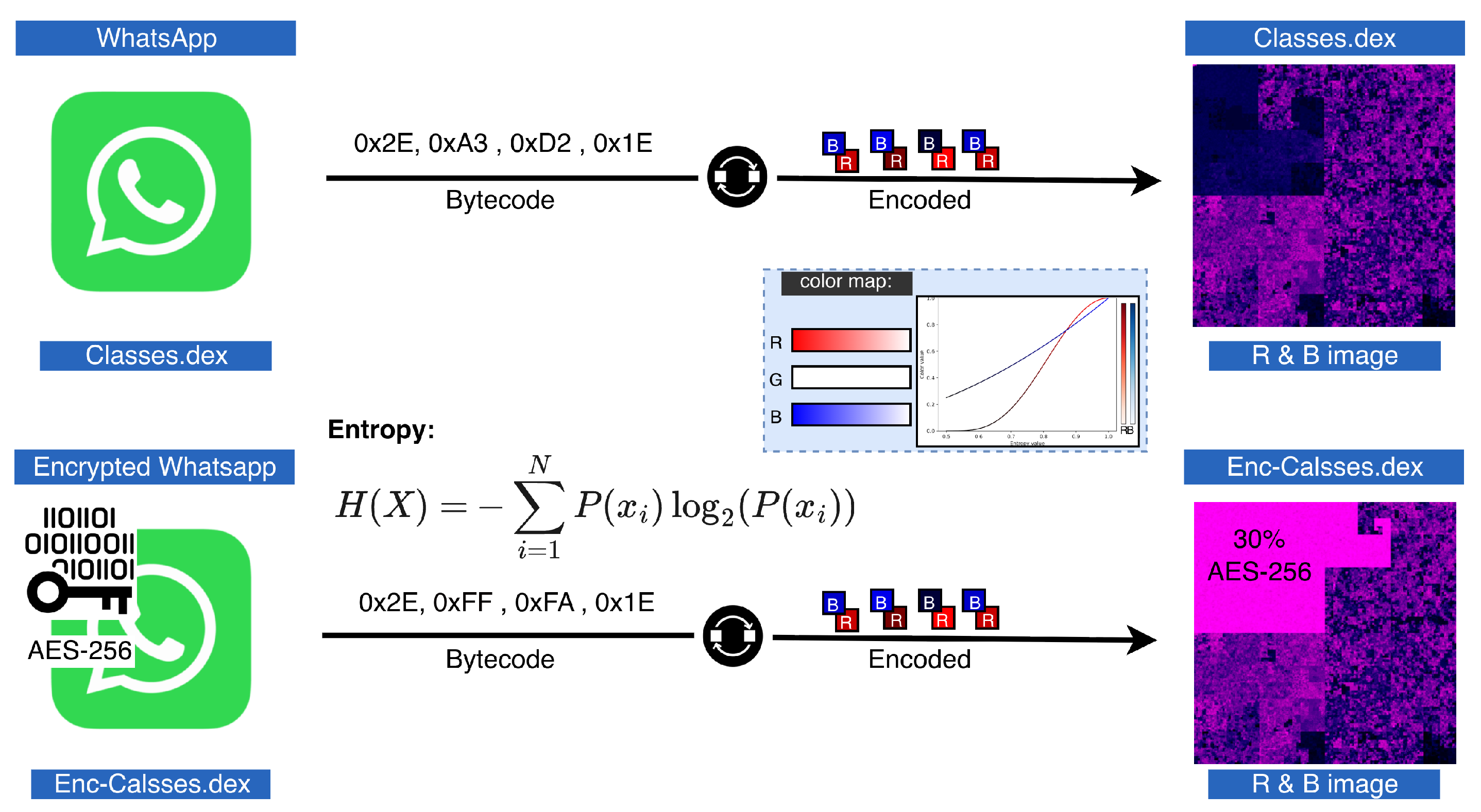

- Enhanced Visualization Framework: Developing an advanced MalVis framework that enhances malware visualization by incorporating an entropy encoder with an N-gram technique. This approach utilizes the three RGB channels to effectively capture a broader range of malware characteristics, including encryption, compression, packing, and structural irregularities. This improves the precision of malware pattern detection in the visualizations.

- Robust Detection Model: Evaluation of the performance of the MalVis framework on several state-of-the-art visualization methods using advanced deep CNN architectures such as MobileNet-V2, DenseNet201, ResNet50, VGG16, and Inception-V3, combined with several ensemble techniques, to further improve detection accuracy and generalization. The results showed that the MalVis framework achieved superior performance compared to others.

- Improved Framework Explainability and Transparency: We employ two distinct heatmap and attention mechanisms, GradCAM and GradCAM++, to ensure that the MalVis Framework effectively utilizes the introduced malicious features detected by the application of our entropy and N-gram encoders to the malware representations. Additionally, identifying prevalent malicious patterns specific to each malware class in the malware representations.

2. Related Works

2.1. Signature-Based Analysis

2.2. Dynamic Analysis

2.3. Static Analysis

2.4. Motivation

2.5. Existing Malware Image Datasets

2.6. Visualization Strategies for Malware Detection

2.6.1. Grayscale Image Encoding

2.6.2. RGB Image Encoding

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Label Generation

3.2. MalVis Bytecode-to-Image Visualization

- Classbyte Encoding:We adopt the Classbyte encoder introduced by Duc-Ly et al. [21], as shown by Figure 3➅, which maps semantic features of bytecode to varying intensities of the green channel. We selected this method due to its effectiveness and comparable performance to our previously employed entropy-based encoding for binary classification tasks.

- N-gram Encoding: We incorporate N-gram representations, as illustrated by Figure 3➅, derived from byte sequences to capture the malware bytecode’s underlying structural patterns and contextual dependencies. This technique, commonly used in malware detection research [62,63], enriches the green channel with statistical features that reflect code regularities and anomalies, thereby enhancing the capability to distinguish between different types of malware.

3.2.1. Approach Classbyte

3.2.2. Approach N-Gram

3.3. The Impact of Entropy and N-Gram on MalVis Representations Experiments

| Algorithm 1 MalVis Visualization Algorithm: generate RGB from bytecode using entropy and N-gram | |

| 1: Input: Data array of bytecode, symbol map , index x | |

| 2: Output: RGB values in the range [0, 255] | |

| 3: | ▹Calculate entropy using a window size of 32 bytes |

| 4: function curve(v) | |

| 5: | |

| 6: | |

| 7: return f | |

| 8: end function | |

| 9: if then | |

| 10. | ▹ Red component is determined by the scaled entropy value |

| 11: else | |

| 12: | ▹ If entropy is less than or equal to 0.5, set red component to 0 |

| 13: end if | |

| 14: | ▹Blue component is proportional to the square of entropy |

| 15: if then | |

| 16: | ▹ Compute 2-byte n-gram value |

| 17: | ▹ Normalize n-gram value to [0, 1] for green component |

| 18: else | |

| 19: | ▹ If at the last byte, the green component is set to 0 |

| 20: end if | |

| 21: return | ▹Return RGB values scaled to the range [0, 255] |

3.3.1. Obfuscation Detection Captured by Entropy in Red and Blue Channels

3.3.2. Unstructured Bytecode Insertion Captured by N-Gram in Green Channel

3.4. Model Architecture and Experiment Settings

3.5. Environment Setup

4. Performance Measures

5. Results

5.1. Evaluation of MalVis (Classbyte Encoded) and MalVis Performance Compared to Other Methods on the Binary Classification Dataset

5.2. Evaluation of MalVis Performance on Imbalanced Multiclass Dataset

5.3. Evaluation of MalVis Performance Using Undersampling

5.4. Evaluation of MalVis Performance Using Ensemble Models

- Average Voting: Combines predictions by averaging the probabilities of all CNN models.

- Majority Voting: Determines the final class by selecting the most predicted by individual models.

- Weighted Voting: Assigns different weights to CNN models based on their prediction accuracy. We preserve the ranking performance of the models and assign weights corresponding to their ranking positions.

- Min Confidence Voting: Only consider a model’s prediction when it meets the minimum required confidence level. In our implementation, a confidence threshold of 60% was selected.

- Soft Voting: Uses the predicted class probabilities to decide the final output.

- Median Voting: Determines decisions by selecting the median of predicted class probabilities.

- Rank-Based Voting: Ranks predictions from models and aggregates ranks to select a class.

- Stacking Ensemble: Trains a new model to integrate the predictions of the base model and improve performance.

5.5. Current Limitations and Future Work

- Statistical Validation: Experiments were conducted using a single train–test split without k-fold cross-validation or statistical significance testing. The primary focus of this research work was to develop a bytecode visualization framework that provides competitive performance and explainable visual patterns for malware analysis.

- Computational Constraints: Performing full cross-validation and repeated training on the 1.3 M sample multiclass dataset was computationally expensive, limiting the scope of statistical validation.

6. Explainability Through Grad-CAM and Grad-CAM++ Visualization

6.1. Grad-CAM

6.2. Grad-CAM++

6.3. Key Findings from Visualization Analysis

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sherif, A. Market Share of Mobile Operating Systems Worldwide from 2009 to 2024, by Quarter. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272698/global-market-share-held-by-mobile-operating-systems-since-2009/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Statista. Smartphone Operating System Share by Age Group in the U.S. as of December 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1313944/main-smartphone-usage-share-by-age/ (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Business, V. Mobile Security Index (MSI) Report 2023: Security Threats and Attacks. 2023. Available online: https://www.verizon.com/business/resources/reports/mobile-security-index/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Noever, D.; Noever, S.E.M. Virus-MNIST: A benchmark malware dataset. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.00602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; González, M.C.; Hidalgo, C.A.; Barabási, A.L. Understanding the spreading patterns of mobile phone viruses. Science 2009, 324, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kienzle, D.M.; Elder, M.C. Recent worms: A survey and trends. In Proceedings of the 2003 ACM workshop on Rapid Malcode, Washington, DC, USA, 27 October 2003; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, S.; Zavrak, S. Adware: A review. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2015, 6, 5599–5604. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh, S.; Di Troia, F.; Potika, K.; Stamp, M. An analysis of Android adware. J. Comput. Virol. Hacking Tech. 2019, 15, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldt, M.; Carlsson, B.; Jacobsson, A. Exploring spyware effects. In Proceedings of the Nordsec 2004, Espoo, Finland, 4–5 November 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A. Ransomware: A research and a personal case study of dealing with this nasty malware. Issues Informing Sci. Inf. Technol. 2017, 14, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beegle, L.E. Rootkits and their effects on information security. Inf. Syst. Secur. 2007, 16, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhenfang, Z. Study on computer trojan horse virus and its prevention. Int. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2015, 2, 257840. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Goundar, S. Keyloggers: Silent cyber security weapons. Netw. Secur. 2020, 2020, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feily, M.; Shahrestani, A.; Ramadass, S. A survey of botnet and botnet detection. In Proceedings of the 2009 Third International Conference on Emerging Security Information, Systems and Technologies, Athens, Greece, 18–23 June 2009; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 268–273. [Google Scholar]

- Pachhala, N.; Jothilakshmi, S.; Battula, B.P. A comprehensive survey on identification of malware types and malware classification using machine learning techniques. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICOSEC), Trichy, India, 7–9 October 2021; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 1207–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Halevi, S.; Krawczyk, H. Strengthening digital signatures via randomized hashing. In Proceedings of the Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 20–24 August 2006; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Canfora, G.; Di Sorbo, A.; Mercaldo, F.; Visaggio, C.A. Obfuscation techniques against signature-based detection: A case study. In Proceedings of the 2015 Mobile Systems Technologies Workshop (MST), Milan, Italy, 22 May 2015; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Thangaveloo, R.; Jing, W.; Chiew, K.L.; Abdullah, J. DATDroid: Dynamic Analysis Technique in Android Malware Detection. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2020, 10, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Ge, X.; Fang, C.; Fan, Y. A systematic literature review of android malware detection using static analysis. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 116363–116379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, R.; Chiba, D.; Goto, S. Detecting android malware by analyzing manifest files. Proc. Asia-Pac. Adv. Netw. 2013, 36, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, D.L.; Nguyen, T.K.; Nguyen, T.V.; Nguyen, T.N.; Massacci, F.; Phung, P.H. HIT4Mal: Hybrid image transformation for malware classification. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2020, 31, e3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, S.; Dong, Y.; Neil, J.; Chau, D.H. A large-scale database for graph representation learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.07682. [Google Scholar]

- Aurangzeb, S.; Aleem, M.; Khan, M.T.; Loukas, G.; Sakellari, G. AndroDex: Android Dex images of obfuscated malware. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurier, M.; Suarez-Tangil, G.; Dash, S.K.; Bissyandé, T.F.; Traon, Y.L.; Klein, J.; Cavallaro, L. Euphony: Harmonious unification of cacophonous anti-virus vendor labels for Android malware. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 20–21 May 2017; IEEE Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 425–435. [Google Scholar]

- VirusTotal—Free Online Virus, Malware, and URL Scanner. Available online: https://www.virustotal.com (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Makkawy, S.J.; Alblwi, A.H.; De Lucia, M.J.; Barner, K.E. Improving Android Malware Detection with Entropy Bytecode-to-Image Encoding Framework. In Proceedings of the 2024 33rd International Conference on Computer Communications and Networks (ICCCN), Kailua-Kona, HI, USA, 29–31 July 2024; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dhammi, A.; Singh, M. Behavior analysis of malware using machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2015 Eighth International Conference on Contemporary Computing (IC3), Noida, India, 20–22 August 2015; pp. 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poettering, B.; Rastikian, S. Sequential digital signatures for cryptographic software-update authentication. In Proceedings of the European Symposium on Research in Computer Security, Copenhagen, Denmark, 26–30 September 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 255–274. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, R. A study on malware and malware detection techniques. Int. J. Educ. Manag. Eng. 2018, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Cai, M.; Yin, S.; Huang, G.; Li, H.; Yuan, W.; Luo, X. Obfuscation-Resilient Android Malware Analysis Based on Complementary Features. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 18, 5056–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsersy, W.F.; Feizollah, A.; Anuar, N.B. The rise of obfuscated Android malware and impacts on detection methods. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2022, 8, e907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirat, D.; Vigna, G. Malgene: Automatic extraction of malware analysis evasion signature. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Denver, CO, USA, 12–16 October 2015; pp. 769–780. [Google Scholar]

- Pereberina, A.; Kostyushko, A.; Tormasov, A. An approach to dynamic malware analysis based on system and application code split. J. Comput. Virol. Hacking Tech. 2022, 18, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Ullah, S.; Srivastava, G.; Lin, J.C.W.; Zhao, Y. NMal-Droid: Network-based android malware detection system using transfer learning and CNN-BiGRU ensemble. Wirel. Netw. 2024, 30, 6177–6198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihwail, R.; Omar, K.; Zainol Ariffin, K.A.; Al Afghani, S. Malware detection approach based on artifacts in memory image and dynamic analysis. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfari, Y.; Meimandi, A. A new approach to android malware detection using fuzzy logic-based simulated annealing and feature selection. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 83, 10525–10549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlova, V.; Goiko, V.; Alexandrova, Y.; Petrov, E. Potential of the dynamic approach to data analysis. E3s Web Conf. 2021, 258, 07012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, T.; Kaushal, R. Malware detection in android based on dynamic analysis. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Cyber Security and Protection of Digital Services (Cyber Security), London, UK, 19–20 June 2017; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jose, R.R.; Salim, A. Integrated static analysis for malware variants detection. In Inventive Computation Technologies, Proceedings of the ICICT 2019 Conference, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, 29–30 August 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 622–629. [Google Scholar]

- Sutter, T.; Kehrer, T.; Rennhard, M.; Tellenbach, B.; Klein, J. Dynamic Security Analysis on Android: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 57261–57287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kancherla, K.; Mukkamala, S. Image visualization based malware detection. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Symposium on Computational Intelligence in Cyber Security (CICS), Singapore, 16–19 April 2013; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Alblwi, A.; Makkawy, S.; Barner, K.E. D-DDPM: Deep Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models for Lesion Segmentation and Data Generation in Ultrasound Imaging. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 41194–41209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, A.; Verma, G.K. Convolutional neural network: A review of models, methodologies and applications to object detection. Prog. Artif. Intell. 2020, 9, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.H.; Kong, S.H.; Paek, D.H. A Survey on Deep Learning-Based Lane Detection Algorithms for Camera and LiDAR. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 7319–7342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chen, M.; Weng, J.; Liu, Z.; Geng, G. Anomaly detection for in-vehicle network using CNN-LSTM with attention mechanism. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 10880–10893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allix, K.; Bissyandé, T.F.; Klein, J.; Le Traon, Y. Androzoo: Collecting millions of android apps for the research community. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories, Austin, TX, USA, 14–22 May 2016; pp. 468–471. [Google Scholar]

- Arp, D.; Spreitzenbarth, M.; Hubner, M.; Gascon, H.; Rieck, K.; Siemens, C. Drebin: Effective and explainable detection of android malware in your pocket. In Proceedings of the Ndss, San Diego, CA, USA, 23–26 February 2014; Volume 14, pp. 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, S.; Duggal, R.; Chau, D.H. MalNet: A large-scale image database of malicious software. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–22 October 2022; pp. 3948–3952. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, T.; Manavi, F.; Hamzeh, A. A PE header-based method for malware detection using clustering and deep embedding techniques. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2021, 60, 102876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nataraj, L.; Karthikeyan, S.; Jacob, G.; Manjunath, B.S. Malware images: Visualization and automatic classification. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Visualization for Cyber Security, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 20 July 2011; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kunwar, P.; Aryal, K.; Gupta, M.; Abdelsalam, M.; Bertino, E. SoK: Leveraging Transformers for Malware Analysis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.17190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalash, M.; Rochan, M.; Mohammed, N.; Bruce, N.D.; Wang, Y.; Iqbal, F. Malware classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th IFIP International Conference on New Technologies, Mobility and Security (NTMS), Paris, France, 26–28 February 2018; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Panconesi, A.; Marian; Cukierski, W.; Committee, W.B.C. Microsoft Malware Classification Challenge (BIG 2015). Kaggle. 2015. Available online: https://kaggle.com/competitions/malware-classification (accessed on 3 March 2024).

- Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, K.; Ding, X.; Wang, X. Advandmal: Adversarial training for android malware detection and family classification. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünver, H.M.; Bakour, K. Android malware detection based on image-based features and machine learning techniques. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoudi, N.; Samhi, J.; Kabore, A.K.; Allix, K.; Bissyandé, T.F.; Klein, J. Dexray: A simple, yet effective deep learning approach to android malware detection based on image representation of bytecode. In Proceedings of the Deployable Machine Learning for Security Defense: Second International Workshop, MLHat 2021, Virtual Event, 15 August 2021; Proceedings 2. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, F.; Li, Q. A novel malware detection and family classification scheme for IoT based on DEAM and DenseNet. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2021, 2021, 6658842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwaish, A.; Naït-Abdesselam, F. Rgb-based android malware detection and classification using convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2020—2020 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 7–11 December 2020; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, S.J.I.; Rahardjo, B.; Juhana, T.; Musashi, Y. MalSSL–Self-Supervised Learning for Accurate and Label-Efficient Malware Classification. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 58823–58835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google.com, A.D. Androguard Tool by Google, 13 February 2013/1st January 2024. Available online: https://code.google.com/archive/p/androguard/ (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Cortesi, A. (BinVis) A Library for Drawing Space-Filling Curves like the Hilbert Curve. 2015. Available online: https://github.com/cortesi/scurve (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Ali, M.; Shiaeles, S.; Bendiab, G.; Ghita, B. MALGRA: Machine learning and N-gram malware feature extraction and detection system. Electronics 2020, 9, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, F.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, C.; Wu, D. Enhancing Malware Classification via Self-Similarity Techniques. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 7232–7244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almomani, I.; Alkhayer, A.; El-Shafai, W. An automated vision-based deep learning model for efficient detection of android malware attacks. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 2700–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, R.; Rawashdeh, J.; Abdullah, M. Machine learning with oversampling and undersampling techniques: Overview study and experimental results. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Systems (ICICS), Irbid, Jordan, 7–9 April 2020; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- Gosain, A.; Sardana, S. Handling class imbalance problem using oversampling techniques: A review. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), Udupi, India, 13–16 September 2017; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhay, A.; Sarkar, A.; Howlader, P.; Balasubramanian, V.N. Grad-cam++: Generalized gradient-based visual explanations for deep convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 839–847. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | # Classes | Dataset Size | Public | Private |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MalVis | 10 | 1,300,822 | ✓ | |

| MalNet [48] | 696 | 1,262,024 | ✓ | |

| AndroDex [23] | 180 | 24,746 | ✓ | |

| Virus-MNIST [4] | 10 | 51,880 | ✓ | |

| MalImg [52] | 25 | 9458 | ✓ | |

| Microsoft [53] | 9 | 108,000 | ✓ | |

| IVMD-2013 [41] | 2 | 37,000 | ✓ | |

| AdvAndMal [54] | 12 | 5560 | ✓ | |

| Halil-2020 [55] | 2 | 29,100 | ✓ |

| Approaches | Models | Accuracy | F1-Score | Precsion | Recall | MCC | R-AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classsbyte Encoder [21] | MNv2 | 91% | 85% | 79% | 92% | 80% | 96% |

| DN201 | 94% | 89% | 89% | 88% | 85% | 97% | |

| RN50 | 93% | 86% | 89% | 83% | 81% | 96% | |

| INC-V3 | 94% | 89% | 92% | 85% | 85% | 97% | |

| VGG16 | 93% | 87% | 86% | 88% | 82% | 96% | |

| MalNet Encoder [48] | MNv2 | 92% | 85% | 91% | 80% | 81% | 97% |

| DN201 | 89% | 83% | 74% | 90% | 77% | 96% | |

| RN50 | 86% | 67% | 91% | 53% | 63% | 94% | |

| INC-V3 | 94% | 90% | 92% | 87% | 86% | 97% | |

| VGG16 | 93% | 88% | 91% | 84% | 84% | 97% | |

| Entropy-based [26] | MNv2 | 93% | 88% | 90% | 85% | 84% | 97% |

| DN201 | 95% | 91% | 90% | 92% | 88% | 98% | |

| RN50 | 93% | 86% | 90% | 82% | 82% | 97% | |

| INC-V3 | 94% | 90% | 91% | 89% | 86% | 97% | |

| VGG16 | 93% | 87% | 94% | 80% | 83% | 97% | |

| MalVis (Classbyte) | MNv2 | 91% | 84% | 89% | 79% | 78% | 96% |

| DN201 | 94% | 90% | 92% | 88% | 86% | 98% | |

| RN50 | 93% | 87% | 92% | 83% | 83% | 97% | |

| INC-V3 | 94% | 88% | 92% | 85% | 84% | 97% | |

| VGG16 | 92% | 86% | 87% | 85% | 81% | 96% | |

| MalVis | MNv2 | 95% | 90% | 91% | 89% | 87% | 98% |

| DN201 | 95% | 90% | 92% | 89% | 87% | 98% | |

| RN50 | 95% | 90% | 92% | 88% | 87% | 98% | |

| INC-V3 | 95% | 90% | 92% | 89% | 87% | 98% | |

| VGG16 | 94% | 89% | 89% | 90% | 86% | 97% |

| Models | MalVis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | F1 | P | R | MCC | ROC-AUC | |

| MNv2 | 83% | 83% | 82% | 83% | 67% | 93% |

| DN201 | 82% | 81% | 81% | 82% | 65% | 95% |

| RN50 | 84% | 84% | 83% | 84% | 68% | 94% |

| INC-V3 | 80% | 78% | 78% | 80% | 59% | 93% |

| VGG16 | 82% | 81% | 81% | 82% | 65% | 91% |

| Models | MalVis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | F1 | P | R | MCC | ROC-AUC | |

| MNv2 | 61% | 61% | 62% | 61% | 57% | 89% |

| DN201 | 66% | 66% | 65% | 66% | 62% | 91% |

| RN50 | 65% | 64% | 64% | 65% | 61% | 90% |

| INC-V3 | 64% | 64% | 64% | 64% | 60% | 90% |

| VGG16 | 60% | 60% | 60% | 60% | 56% | 89% |

| Ensemble Methods | MalVis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | F1 | P | R | ROC-AUC | |

| Average Voting | 66% | 65% | 65% | 66% | 81% |

| Majority Voting | 63% | 61% | 63% | 63% | 79% |

| Weighted Voting | 64% | 63% | 63% | 64% | 80% |

| Min Confidence Voting | 88% | 86% | 89% | 88% | 86% |

| Soft Voting | 66% | 65% | 65% | 66% | 81% |

| Median Voting | 64% | 63% | 64% | 64% | 80% |

| Rank-Based Voting | 63% | 63% | 64% | 63% | 79% |

| Stacking Ensemble | 83% | 83% | 83% | 83% | 90% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makkawy, S.J.; De Lucia, M.J.; Barner, K.E. MalVis: Large-Scale Bytecode Visualization Framework for Explainable Android Malware Detection. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2025, 5, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp5040109

Makkawy SJ, De Lucia MJ, Barner KE. MalVis: Large-Scale Bytecode Visualization Framework for Explainable Android Malware Detection. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy. 2025; 5(4):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp5040109

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakkawy, Saleh J., Michael J. De Lucia, and Kenneth E. Barner. 2025. "MalVis: Large-Scale Bytecode Visualization Framework for Explainable Android Malware Detection" Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 5, no. 4: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp5040109

APA StyleMakkawy, S. J., De Lucia, M. J., & Barner, K. E. (2025). MalVis: Large-Scale Bytecode Visualization Framework for Explainable Android Malware Detection. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, 5(4), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp5040109