Towards an End-to-End (E2E) Adversarial Learning and Application in the Physical World †

Abstract

1. Introduction

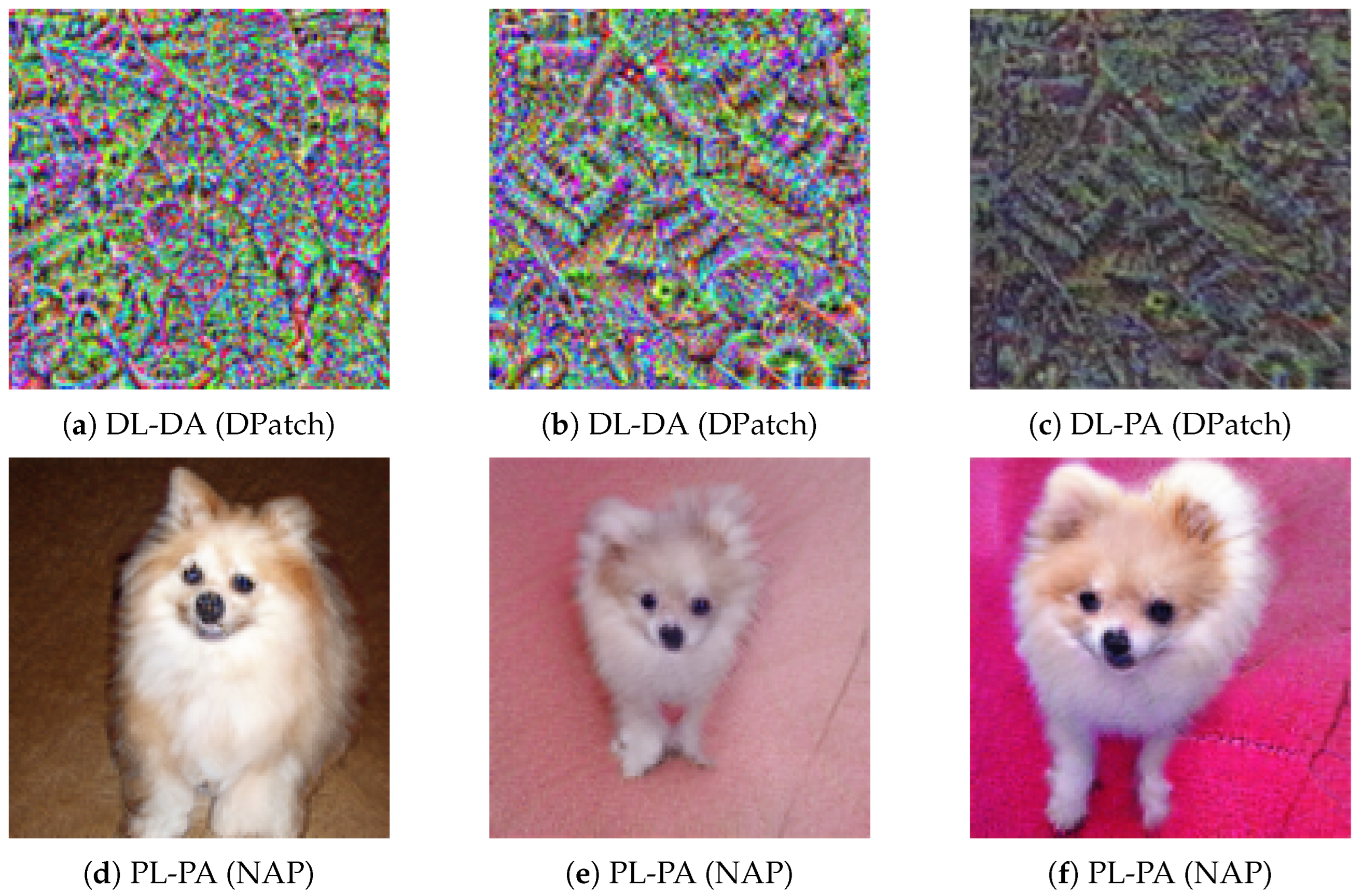

2. Transferability Between Digital and Physical Domains

2.1. Experimental Setup

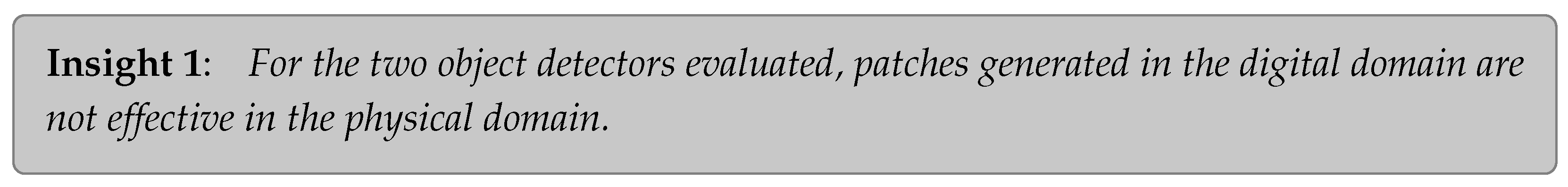

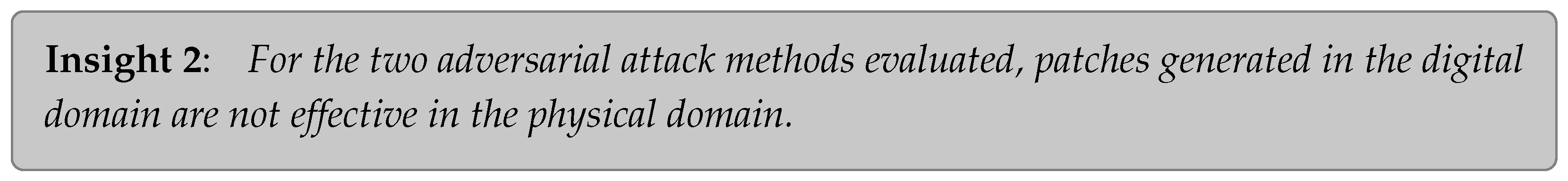

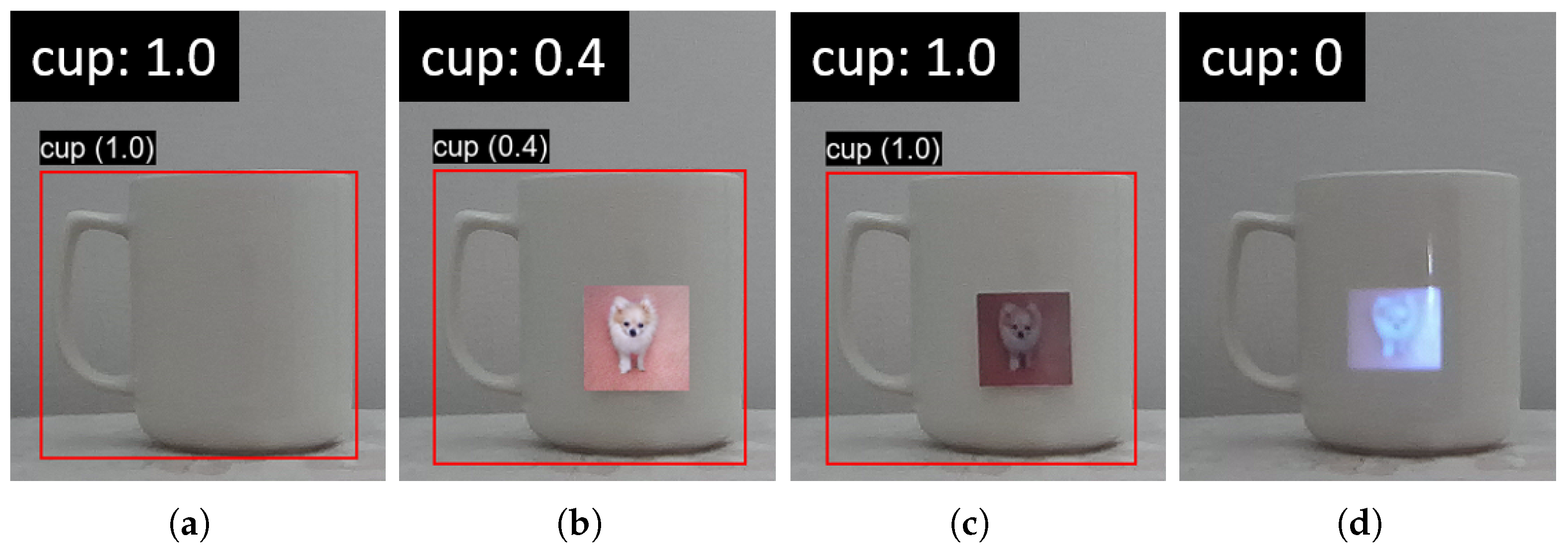

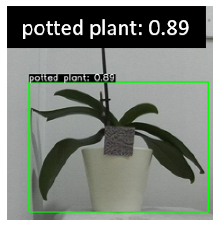

2.2. Failure of Transferability

2.3. Cause of the Failure

2.3.1. Differences Between Digital and Physical Patches

2.3.2. Differences Between Consecutive Captures of the Same Scene

3. Threat Model and Method

3.1. Threat Model

3.1.1. Attacker’s Capabilities and Knowledge

3.1.2. Extension of Previously Evaluated Threat Model

3.1.3. Significance

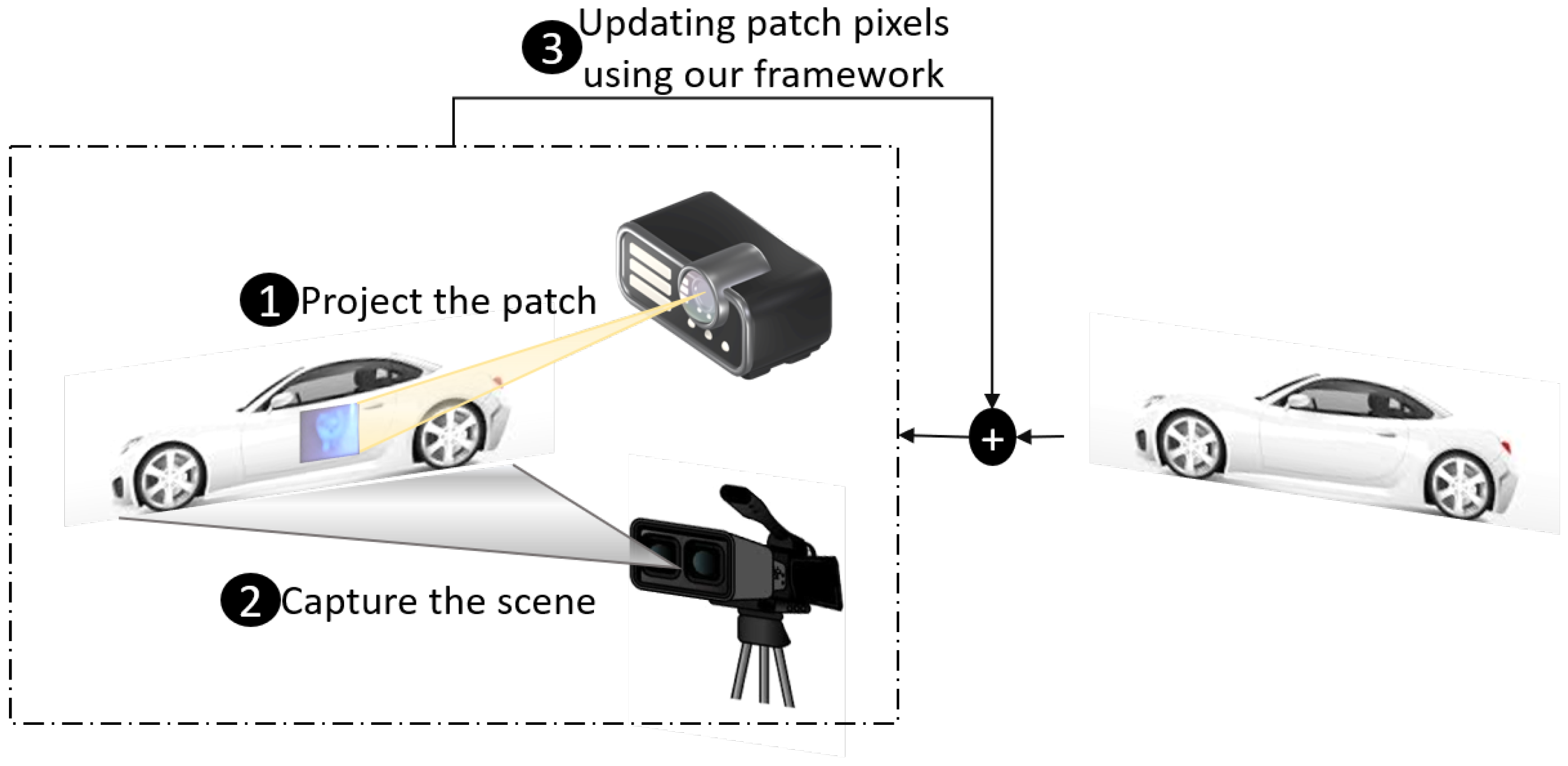

3.2. Method—PAPLA

- Iterative Learning: In this phase, the framework generates a random digital patch using an existing digital attack method (e.g., DPatch [14] or NAP [4]). The patch is then iteratively optimized according to the chosen attack, using footage from the physical domain:

- (a)

- Apply (project) the patch onto the target object using a projector.

- (b)

- Capture the physical scene containing the object and the projected patch with a camera.

- (c)

- Update the patch pixels iteratively using the chosen attack, incorporating the physical conditions to maximize the adversarial effect.

- Attack Application: After the patch is fully optimized, it is projected onto the target object in the physical environment to mislead the object detector.

| Algorithm 1 PAPLA |

|

4. Analysis

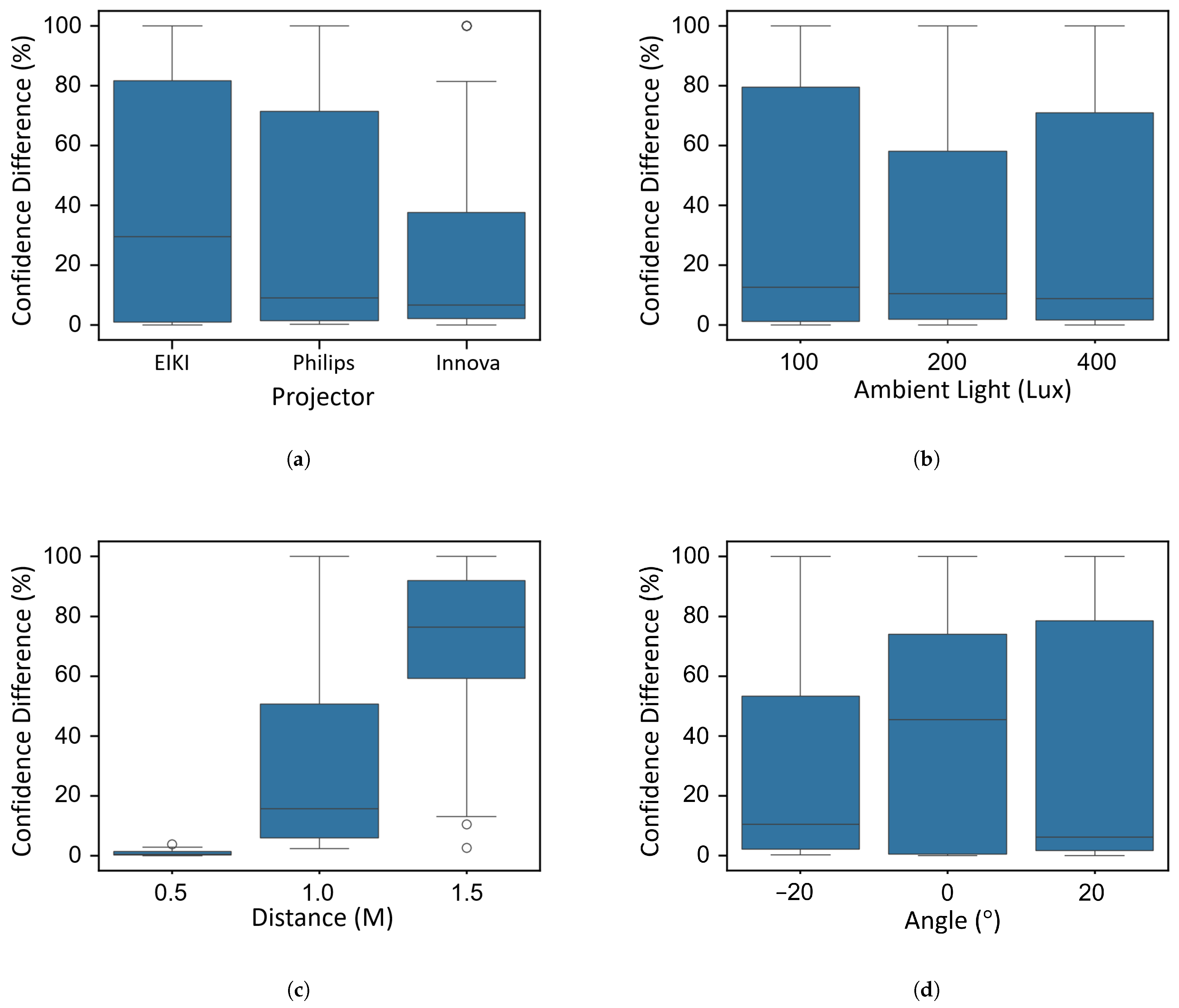

4.1. Impact of Environmental Factors on Attack Success

4.1.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.2. Results

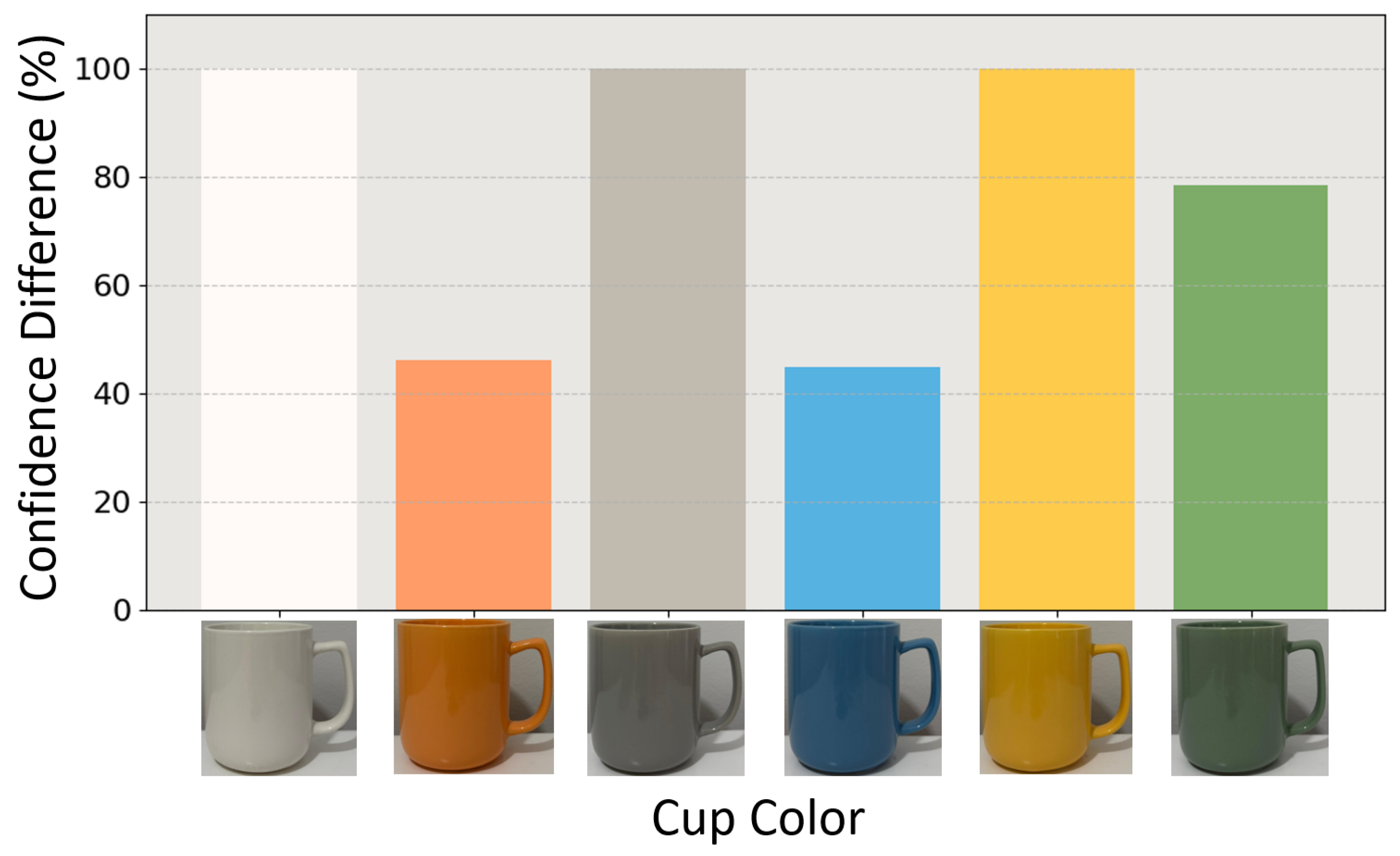

4.2. Effect of Surface Color on Patch Effectiveness

4.2.1. Experimental Setup

4.2.2. Results

5. Evaluations

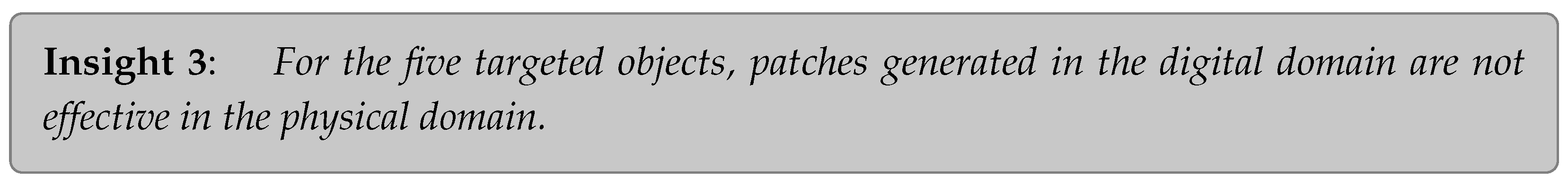

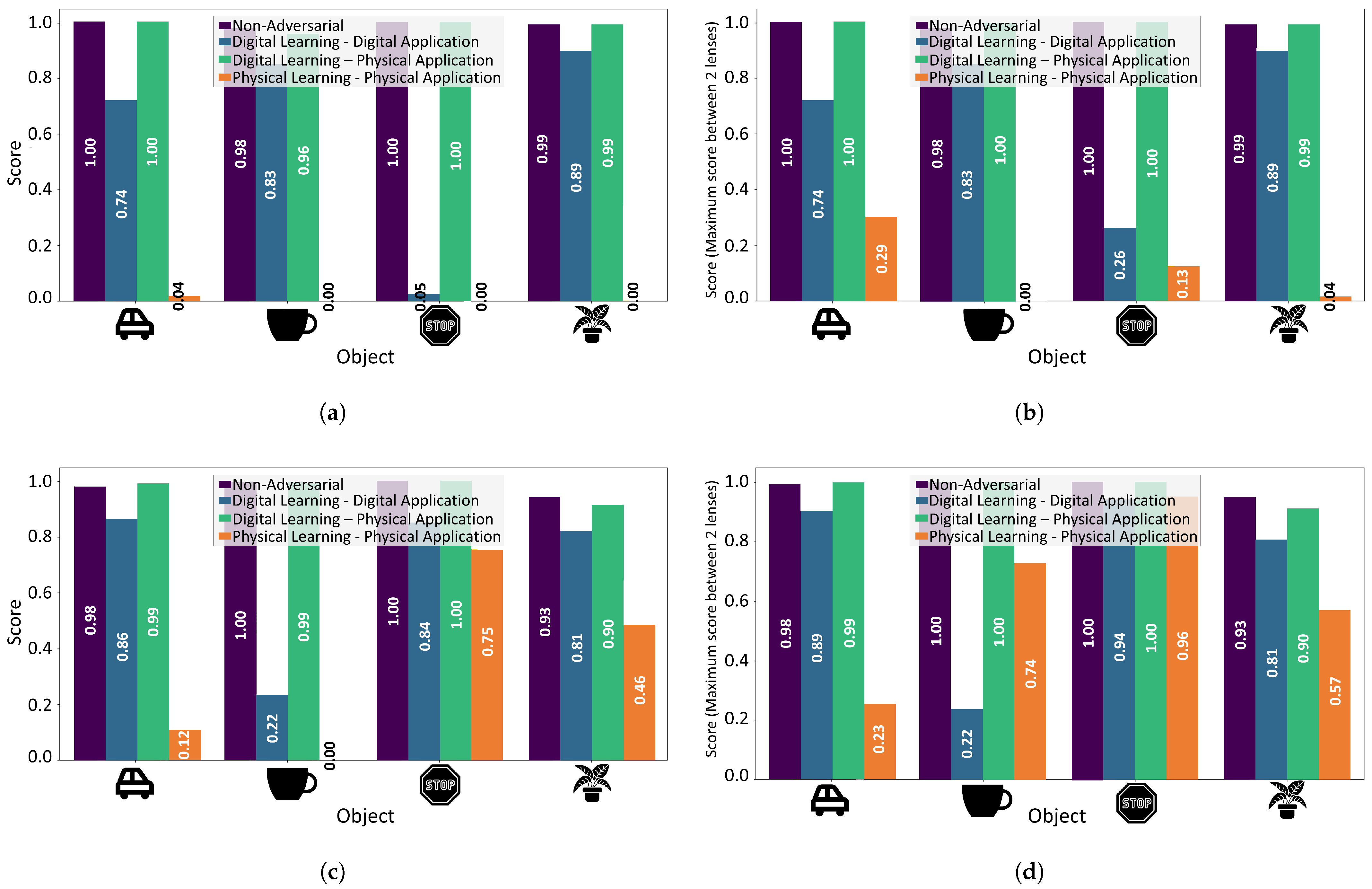

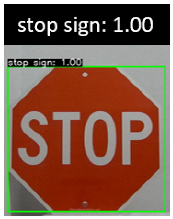

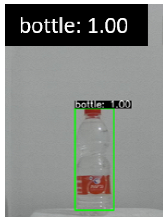

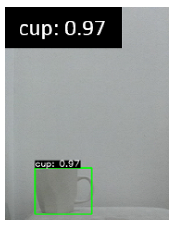

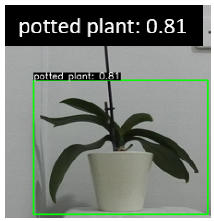

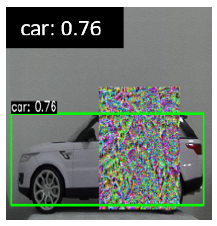

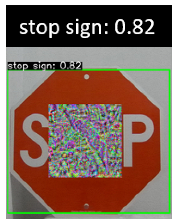

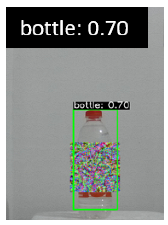

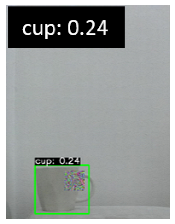

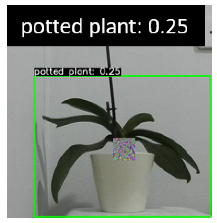

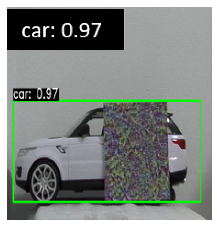

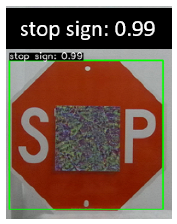

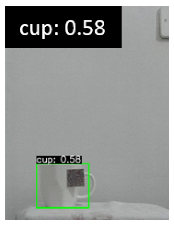

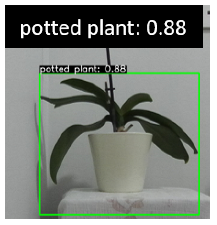

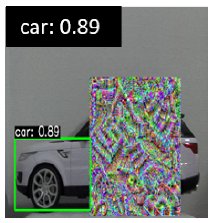

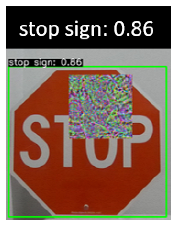

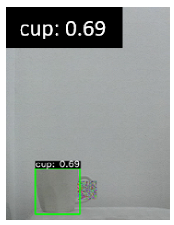

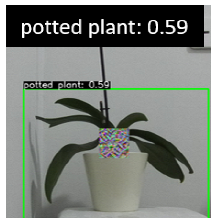

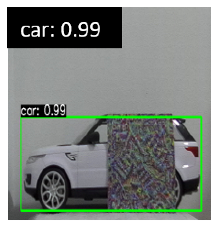

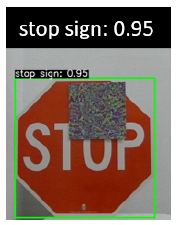

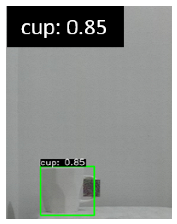

5.1. Robustness Against Various Target Objects

5.1.1. Experimental Setup

5.1.2. Results

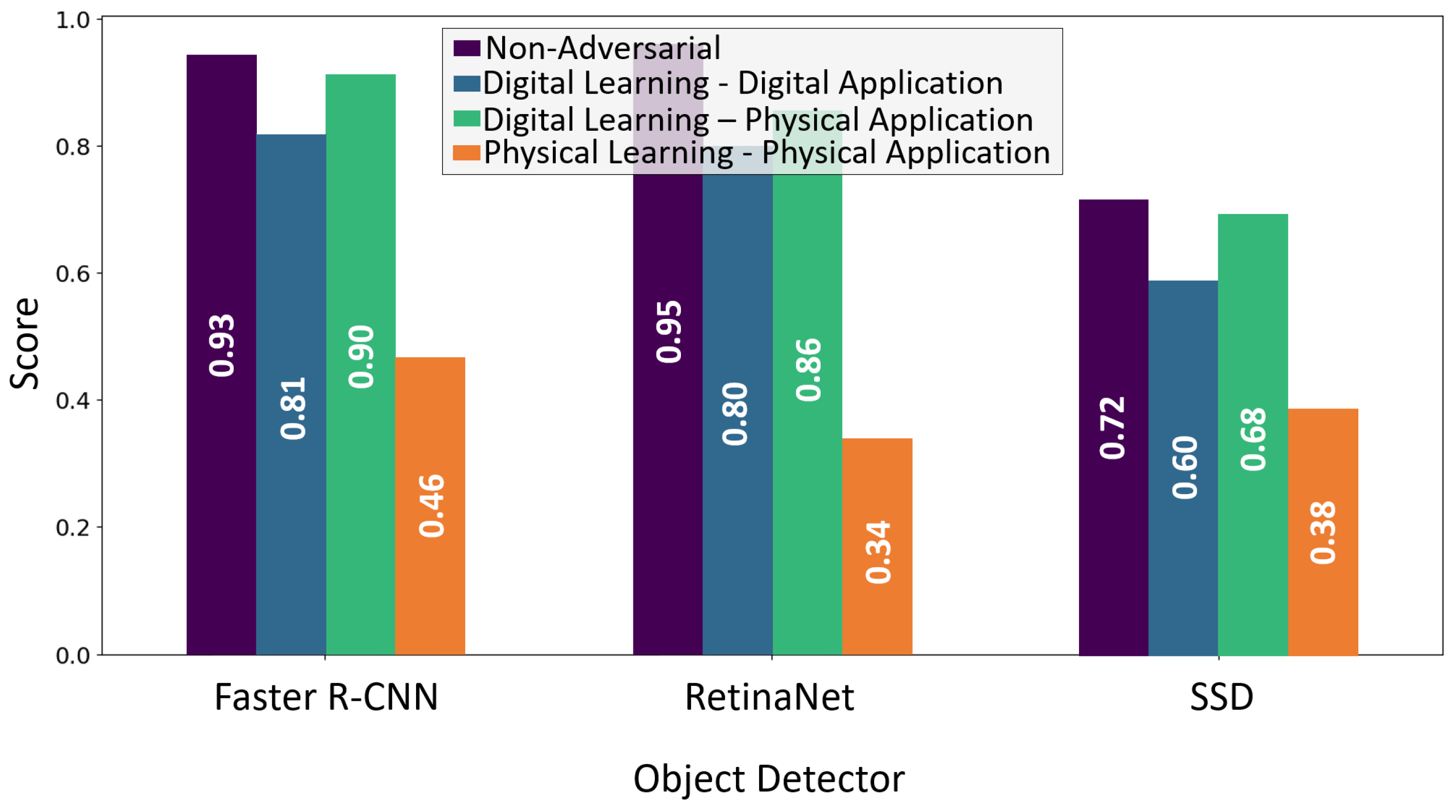

5.2. Robustness Against Various Object Detectors

5.2.1. Experimental Setup

5.2.2. Results

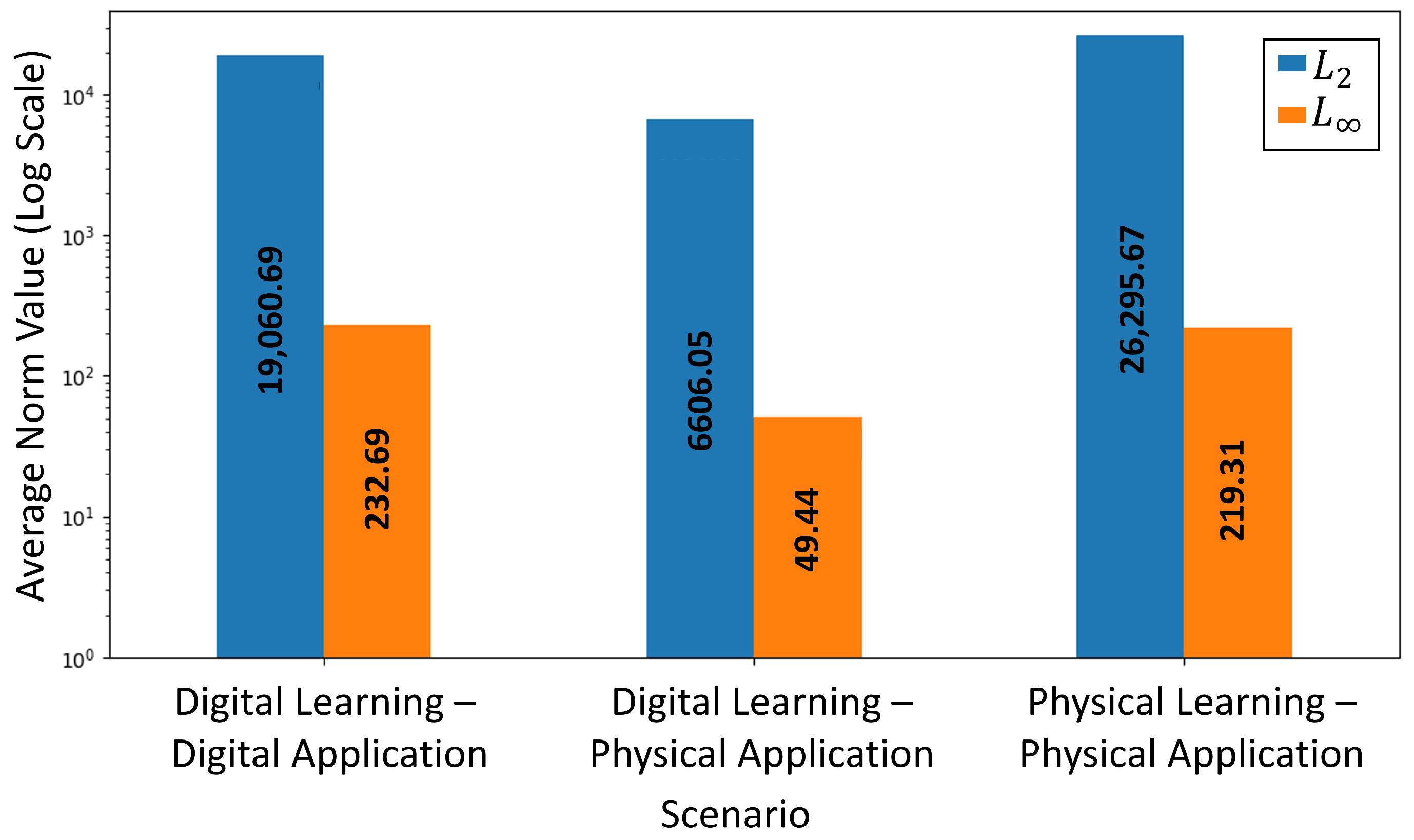

5.3. Evaluating Image Quality Using and

Results

5.4. Transferability of Patches Across Object Detectors

5.4.1. Experimental Setup

5.4.2. Results

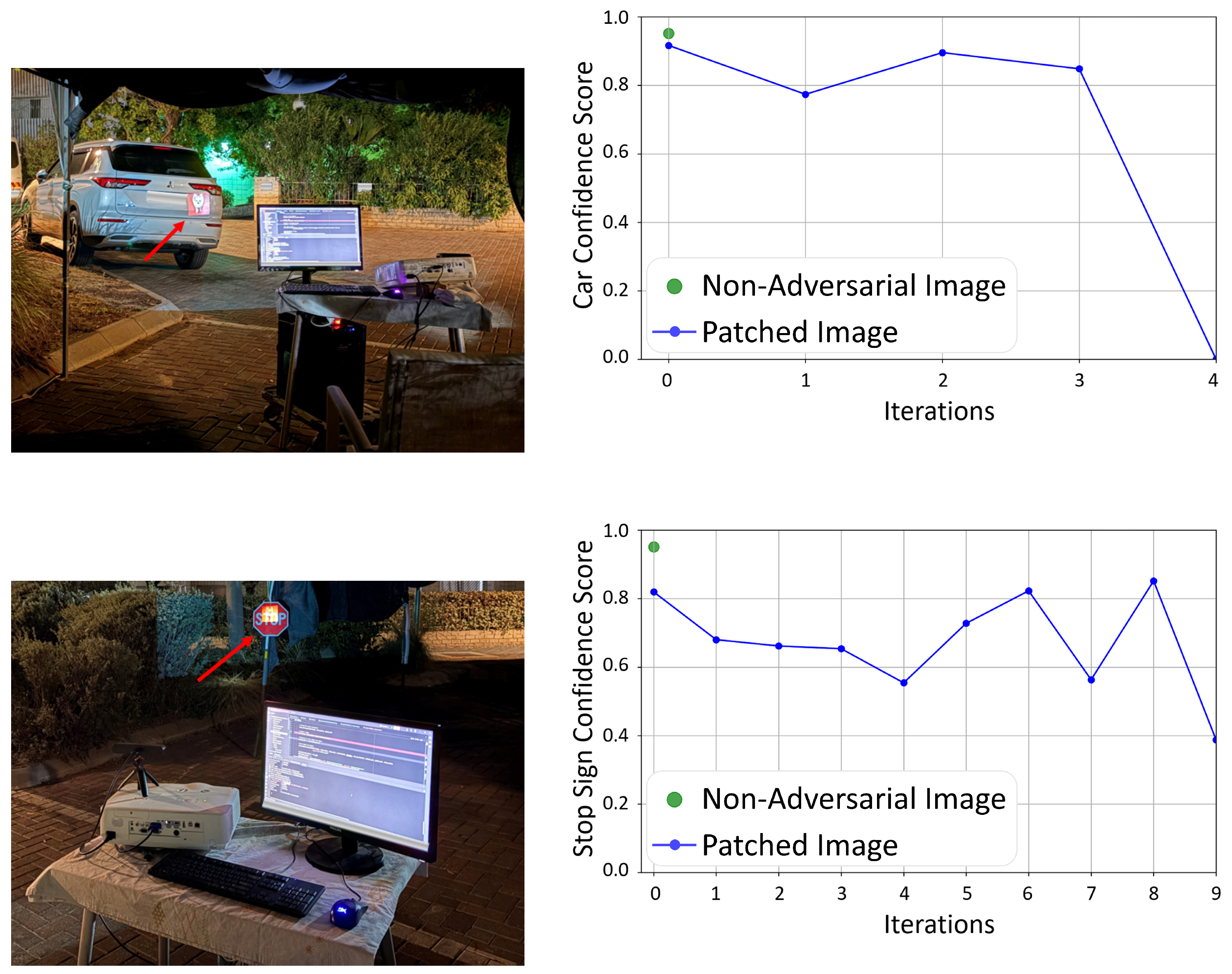

5.5. Performance in the Real World

5.5.1. Experimental Setup

5.5.2. Results

6. Limitations & Constraints

7. Related Work

8. Conclusions & Discussion

Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Ouardirhi, Z.; Mahmoudi, S.A.; Zbakh, M. Enhancing Object Detection in Smart Video Surveillance: A Survey of Occlusion-Handling Approaches. Electronics 2024, 13, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubna; Mufti, N.; Shah, S.A.A. Automatic number plate Recognition: A detailed survey of relevant algorithms. Sensors 2021, 21, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juyal, A.; Sharma, S.; Matta, P. Deep learning methods for object detection in autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI), Tirunelveli, India, 3–5 June 2021; pp. 751–755. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.C.T.; Kung, B.H.; Tan, D.S.; Chen, J.C.; Hua, K.L.; Cheng, W.H. Naturalistic physical adversarial patch for object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 7848–7857. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Jordan, M.I.; Wainwright, M.J. Hopskipjumpattack: A query-efficient decision-based attack. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–21 May 2020; pp. 1277–1294. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Gardner, J.; You, Y.; Wilson, A.G.; Weinberger, K. Simple black-box adversarial attacks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 2484–2493. [Google Scholar]

- Brendel, W.; Rauber, J.; Bethge, M. Decision-based adversarial attacks: Reliable attacks against black-box machine learning models. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.04248. [Google Scholar]

- Athalye, A.; Engstrom, L.; Ilyas, A.; Kwok, K. Synthesizing Robust Adversarial Examples. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1707.07397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Eykholt, K.; Evtimov, I.; Fernandes, E.; Li, B.; Rahmati, A.; Tramer, F.; Prakash, A.; Kohno, T. Physical adversarial examples for object detectors. In Proceedings of the 12th USENIX Workshop on Offensive Technologies (WOOT 18), Baltimore, MD, USA, 13–14 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Kolter, Z. On physical adversarial patches for object detection. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.11897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eykholt, K.; Evtimov, I.; Fernandes, E.; Li, B.; Rahmati, A.; Xiao, C.; Prakash, A.; Kohno, T.; Song, D. Robust physical-world attacks on deep learning visual classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 1625–1634. [Google Scholar]

- Katzav, R.; Giloni, A.; Grolman, E.; Saito, H.; Shibata, T.; Omino, T.; Komatsu, M.; Hanatani, Y.; Elovici, Y.; Shabtai, A. Adversarialeak: External information leakage attack using adversarial samples on face recognition systems. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 4 October–29 September 2024; pp. 288–303. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.T.; Cornelius, C.; Martin, J.; Chau, D.H. Shapeshifter: Robust physical adversarial attack on faster R-CNN object detector. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases: European Conference, ECML PKDD 2018, Dublin, Ireland, 10–14 September 2018; pp. 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, Z.; Song, L.; Li, H.; Chen, Y. Dpatch: An adversarial patch attack on object detectors. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.02299. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Foroosh, H.; David, P.; Gong, B. CAMOU: Learning physical vehicle camouflages to adversarially attack detectors in the wild. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Learning Representations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Thys, S.; Van Ranst, W.; Goedemé, T. Fooling automated surveillance cameras: Adversarial patches to attack person detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–17 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Zhang, G.; Liu, S.; Fan, Q.; Sun, M.; Chen, H.; Chen, P.Y.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X. Adversarial t-shirt! evading person detectors in a physical world. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Proceedings of the 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part V 16; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 665–681. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Gao, C.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, C.; Yuille, A.L.; Zou, C.; Liu, N. Universal physical camouflage attacks on object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 720–729. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Lim, S.N.; Davis, L.S.; Goldstein, T. Making an invisibility cloak: Real world adversarial attacks on object detectors. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2020, Proceedings of the 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part IV 16; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zolfi, A.; Kravchik, M.; Elovici, Y.; Shabtai, A. The translucent patch: A physical and universal attack on object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 15232–15241. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, P.; Tang, Q.; Du, Y.; Xue, L.; Luo, X.; Wang, T.; Nie, S.; Wu, S. Too good to be safe: Tricking lane detection in autonomous driving with crafted perturbations. In Proceedings of the 30th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 21), Virtual Event, 11–13 August 2021; pp. 3237–3254. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.; Ji, N.; Xie, H.; Xiang, X. Legitimate adversarial patches: Evading human eyes and detection models in the physical world. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Chengdu, China, 20–24 October 2021; pp. 5307–5315. [Google Scholar]

- Suryanto, N.; Kim, Y.; Kang, H.; Larasati, H.T.; Yun, Y.; Le, T.T.H.; Yang, H.; Oh, S.Y.; Kim, H. DTA: Physical camouflage attacks using differentiable transformation network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 15305–15314. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Huang, S.; Zhu, X.; Sun, F.; Zhang, B.; Hu, X. Adversarial texture for fooling person detectors in the physical world. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 13307–13316. [Google Scholar]

- Biton, D.; Misra, A.; Levy, E.; Kotak, J.; Bitton, R.; Schuster, R.; Papernot, N.; Elovici, Y.; Nassi, B. The Adversarial Implications of Variable-Time Inference. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security, Copenhagen, Denmark, 30 November 2023; pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, W.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Qu, G. Fooling the eyes of autonomous vehicles: Robust physical adversarial examples against traffic sign recognition systems. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.06192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, Z.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K. T-SEA: Transfer-based self-ensemble attack on object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 20514–20523. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Ji, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xu, W. {TPatch}: A Triggered Physical Adversarial Patch. In Proceedings of the 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23), Anaheim, CA, USA, 9–11 August 2023; pp. 661–678. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Chu, W.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, B.; Hu, X. Physically realizable natural-looking clothing textures evade person detectors via 3d modeling. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 16975–16984. [Google Scholar]

- Guesmi, A.; Ding, R.; Hanif, M.A.; Alouani, I.; Shafique, M. Dap: A dynamic adversarial patch for evading person detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 24595–24604. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Hou, J.; Liu, Y.; Tang, H.; Wang, Z. Revisiting Adversarial Patches for Designing Camera-Agnostic Attacks against Person Detection. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Hu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Su, H.; Hu, X. Full-Distance Evasion of Pedestrian Detectors in the Physical World. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Hu, Z.; Huang, S.; Li, J.; Hu, X. Infrared invisible clothing: Hiding from infrared detectors at multiple angles in real world. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 13317–13326. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Wang, Z.; Jia, X.; Zheng, Y.; Tang, H.; Satoh, S.; Wang, Z. Hotcold block: Fooling thermal infrared detectors with a novel wearable design. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; Volume 37, pp. 15233–15241. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Yu, J.; Huang, Y. Infrared adversarial patches with learnable shapes and locations in the physical world. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2024, 132, 1928–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Li, J.; Hu, X. Infrared Adversarial Car Stickers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 24284–24293. [Google Scholar]

- Lovisotto, G.; Turner, H.; Sluganovic, I.; Strohmeier, M.; Martinovic, I. {SLAP}: Improving physical adversarial examples with {Short-Lived} adversarial perturbations. In Proceedings of the 30th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 21), Virtual Event, 11–13 August 2021; pp. 1865–1882. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, H.; Chang, S.; Zhou, L.; Liu, W.; Zhu, H. OptiCloak: Blinding Vision-Based Autonomous Driving Systems Through Adversarial Optical Projection. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 28931–28944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Shi, W.; Tian, L. Adversarial color projection: A projector-based physical-world attack to DNNs. Image Vis. Comput. 2023, 140, 104861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, R.H.; Lin, J.Y.; Hsieh, S.Y.; Lin, H.Y.; Lin, C.L. Adversarial patch attacks on deep-learning-based face recognition systems using generative adversarial networks. Sensors 2023, 23, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komkov, S.; Petiushko, A. Advhat: Real-world adversarial attack on arcface face id system. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Milan, Italy, 10–15 January 2021; pp. 819–826. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.S.; Hsu, C.Y.; Chen, P.Y.; Yu, C.M. Real-world adversarial examples via makeup. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022—2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 2854–2858. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Huang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yu, J. Unified adversarial patch for cross-modal attacks in the physical world. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 4445–4454. [Google Scholar]

- Nassi, B.; Mirsky, Y.; Nassi, D.; Ben-Netanel, R.; Drokin, O.; Elovici, Y. Phantom of the adas: Securing advanced driver-assistance systems from split-second phantom attacks. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Virtual Event, 9–13 November 2020; pp. 293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. Yolov3: An incremental improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M. Yolov4: Optimal speed and accuracy of object detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.I.; Tian, Q. Adversarial attack and defense of yolo detectors in autonomous driving scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Aachen, Germany, 4–9 June 2022; pp. 1011–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolae, M.I.; Sinn, M.; Tran, M.N.; Buesser, B.; Rawat, A.; Wistuba, M.; Zantedeschi, V.; Baracaldo, N.; Chen, B.; Ludwig, H.; et al. Adversarial Robustness Toolbox v1.0.0. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.01069. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, T.Y.; Dollár, G. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2016, Proceedings of the 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Proceedings, Part I 14; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pautov, M.; Melnikov, G.; Kaziakhmedov, E.; Kireev, K.; Petiushko, A. On adversarial patches: Real-world attack on arcface-100 face recognition system. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Multi-Conference on Engineering, Computer and Information Sciences (SIBIRCON), Novosibirsk, Russia, 21–27 October 2019; pp. 0391–0396. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, M.; Bhagavatula, S.; Bauer, L.; Reiter, M.K. Accessorize to a crime: Real and stealthy attacks on state-of-the-art face recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Vienna, Austria, 24–28 October 2016; pp. 1528–1540. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.A.; Lu, Y.Z.; Chiang, C.K. Generating adversarial examples by makeup attacks on face recognition. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Taipei, Taiwan, 22–25 September 2019; pp. 2516–2520. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, B.; Wang, W.; Yao, T.; Guo, J.; Kong, Z.; Ding, S.; Li, J.; Liu, C. Adv-makeup: A new imperceptible and transferable attack on face recognition. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.03162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Bhupathiraju, S.H.V.; Clifford, M.; Sugawara, T.; Chen, Q.A.; Rampazzi, S. Invisible Reflections: Leveraging Infrared Laser Reflections to Target Traffic Sign Perception. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.03582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.; Mao, X.; Qin, A.K.; Chen, Y.; Ye, S.; He, Y.; Yang, Y. Adversarial laser beam: Effective physical-world attack to dnns in a blink. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 16062–16071. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Tang, D.; Wang, X.; Han, W.; Liu, X.; Zhang, K. Invisible Mask: Practical Attacks on Face Recognition with Infrared. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.04683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Liao, Z.; Zhu, L.; Xu, K.; Du, X. VLA: A practical visible light-based attack on face recognition systems in physical world. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2019, 3, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Hu, X. Fooling thermal infrared pedestrian detectors in real world using small bulbs. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Event, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 3616–3624. [Google Scholar]

- Yufeng, L.; Fengyu, Y.; Qi, L.; Jiangtao, L.; Chenhong, C. Light can be dangerous: Stealthy and effective physical-world adversarial attack by spot light. Comput. Secur. 2023, 132, 103345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yao, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Hao, P.; Zhu, T. I can see the light: Attacks on autonomous vehicles using invisible lights. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Virtual Event, 15–19 November 2021; pp. 1930–1944. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, E.; Tramer, F.; Pellegrino, G. Sentinet: Detecting localized universal attacks against deep learning systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW), San Francisco, CA, USA, 21 May 2020; pp. 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Levine, A.; Lau, C.P.; Chellappa, R.; Feizi, S. Segment and complete: Defending object detectors against adversarial patch attacks with robust patch detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 14973–14982. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, G.; Zhou, S.; Tang, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Yuan, D. Self-Supervised Visual Tracking via Image Synthesis and Domain Adversarial Learning. Sensors 2025, 25, 4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Tan, K.; Yuan, D.; Liu, Q. Progressive Domain Adaptation for Thermal Infrared Tracking. Electronics 2025, 14, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attack | Target Detector | Scenario | Target Objects | Avg. Conf. Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPatch | YOLOv3 | Non-Adversarial |  |  |  |  |  | 0.96 |

| Digital Learning - Digital Application |  |  |  |  |  | 0.55 | ||

| Digital Learning - Physical Application |  |  |  |  |  | 0.88 | ||

| Robust DPatch | Faster R-CNN | Non-Adversarial |  |  |  |  |  | 0.98 |

| Digital Learning - Digital Application |  |  |  |  |  | 0.77 | ||

| Digital Learning - Physical Application |  |  |  |  |  | 0.93 | ||

| Camera Model | Patch | (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZED2i | #1 | 15,770.25 | 221 | 99.42 |

| #2 | 17,249.71 | 213 | 99.50 | |

| #3 | 13,635.54 | 207 | 99.39 | |

| iPhone 16 | #1 | 11,087.62 | 197 | 99.17 |

| #2 | 11,329.53 | 204 | 99.06 | |

| #3 | 12,847.78 | 236 | 99.30 | |

| YI Dash Camera | #1 | 15,779.49 | 231 | 99.39 |

| #2 | 16,285.12 | 239 | 99.40 | |

| #3 | 13,981.11 | 242 | 99.46 | |

| Average | 14,218.46 | 221.11 | 99.34 | |

| Camera Model | Previous Image | Current Image | (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZED2i |  |  | 10,371.30 | 45 | 89.69 |

|  | 9981.69 | 85 | 89.59 | |

|  | 9844.01 | 87 | 89.22 | |

| iPhone 16 |  |  | 4595.37 | 33 | 79.23 |

|  | 4075.02 | 35 | 68.28 | |

|  | 5970.31 | 78 | 73.33 | |

| YI Dash Camera |  |  | 10,340.12 | 125 | 71.85 |

|  | 9762.41 | 96 | 71.78 | |

|  | 9439.34 | 88 | 71.35 | |

| Average | 8264.40 | 74.67 | 78.26 | ||

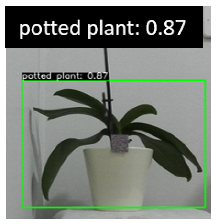

| Target Object | Tested Detector | Conf. Diff. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DL-DA | PL-PA | ||

| Potted Plant | Faster R-CNN | 18.0% | 41.6% |

| SSD | 13.4% | 3.0% | |

| RetinaNet | 16.1% | 40.4% | |

| YOLOv3 | 0% | 0% | |

| YOLOv11 | 40.8% | 100.0% | |

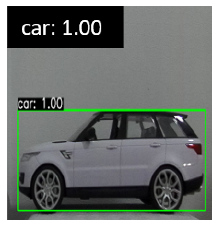

| Car | Faster R-CNN | 15.4% | 100.0% |

| SSD | 39.2% | 100.0% | |

| RetinaNet | 0% | 23.9% | |

| YOLOv3 | 100.0% | 47.1% | |

| YOLOv11 | - | - | |

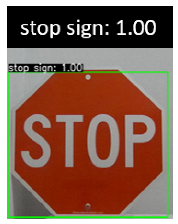

| Stop Sign | Faster R-CNN | 28.5% | 14.9% |

| SSD | 45.8% | 100.0% | |

| RetinaNet | 5.2% | 0.1% | |

| YOLOv3 | 0% | 32.7% | |

| YOLOv11 | 38.3% | 33.3% | |

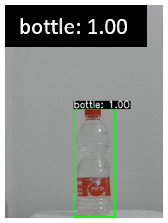

| Cup | Faster R-CNN | 59.6% | 100.0% |

| SSD | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| RetinaNet | 100.0% | 44.9% | |

| YOLOv3 | 22.9% | 13.8% | |

| YOLOv11 | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Average Percentage Confidence Difference | 39.1% | 52.4% | |

| Target Object | Tested Detector | Conf. Diff. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DL-DA | PL-PA | ||

| Potted Plant | YOLOv3 | 21.8% | 71.0% |

| SSD | 0% | 0% | |

| RetinaNet | 6.3% | 19.3% | |

| Faster R-CNN | 7.2% | 14.2% | |

| YOLOv11 | 32.9% | 100.0% | |

| Car | YOLOv3 | 16.5% | 84.3% |

| SSD | 0% | 4.3% | |

| RetinaNet | 12.3% | 17.2% | |

| Faster R-CNN | 1.3% | 0.1% | |

| YOLOv11 | - | - | |

| Stop Sign | YOLOv3 | 12.1% | 100.0% |

| SSD | 0% | 0% | |

| RetinaNet | 0% | 0% | |

| Faster R-CNN | 0% | 0% | |

| YOLOv11 | 4.5% | 31.4% | |

| Cup | YOLOv3 | 57.3% | 84.1% |

| SSD | 100.0% | 21.5% | |

| RetinaNet | 4.0% | 24.9% | |

| Faster R-CNN | 0% | 3.9% | |

| YOLOv11 | 100.0% | 100.0% | |

| Average Percentage Confidence Difference | 19.8% | 35.6% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Biton, D.; Shams, J.; Koda, S.; Shabtai, A.; Elovici, Y.; Nassi, B. Towards an End-to-End (E2E) Adversarial Learning and Application in the Physical World. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2025, 5, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp5040108

Biton D, Shams J, Koda S, Shabtai A, Elovici Y, Nassi B. Towards an End-to-End (E2E) Adversarial Learning and Application in the Physical World. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy. 2025; 5(4):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp5040108

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiton, Dudi, Jacob Shams, Satoru Koda, Asaf Shabtai, Yuval Elovici, and Ben Nassi. 2025. "Towards an End-to-End (E2E) Adversarial Learning and Application in the Physical World" Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 5, no. 4: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp5040108

APA StyleBiton, D., Shams, J., Koda, S., Shabtai, A., Elovici, Y., & Nassi, B. (2025). Towards an End-to-End (E2E) Adversarial Learning and Application in the Physical World. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, 5(4), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcp5040108