The Evolution and Impact of Glacier and Ice-Rock Avalanches in the Tibetan Plateau with Sentinel-2 Time-Series Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

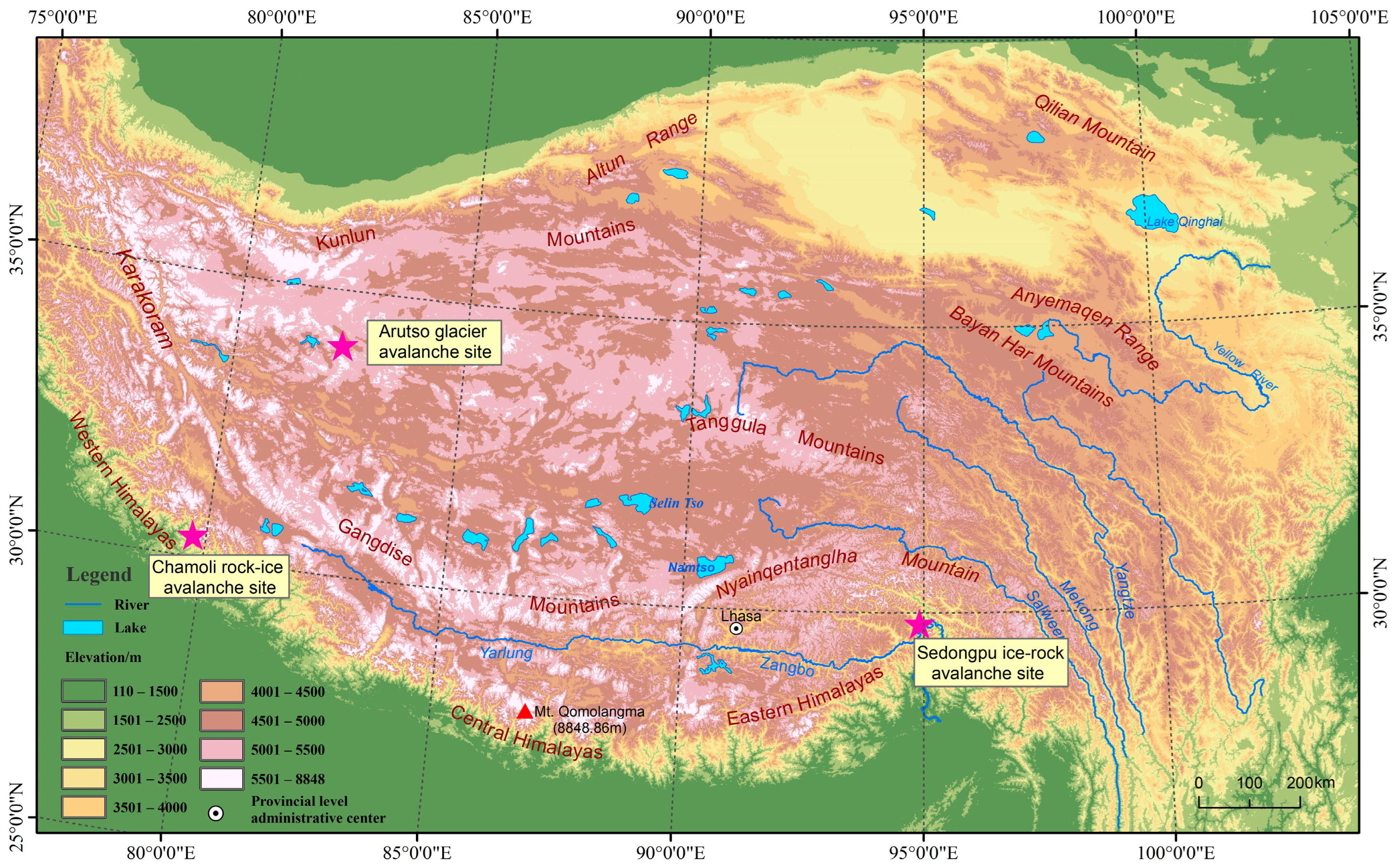

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Satellite Data

2.3. Methods

3. Results

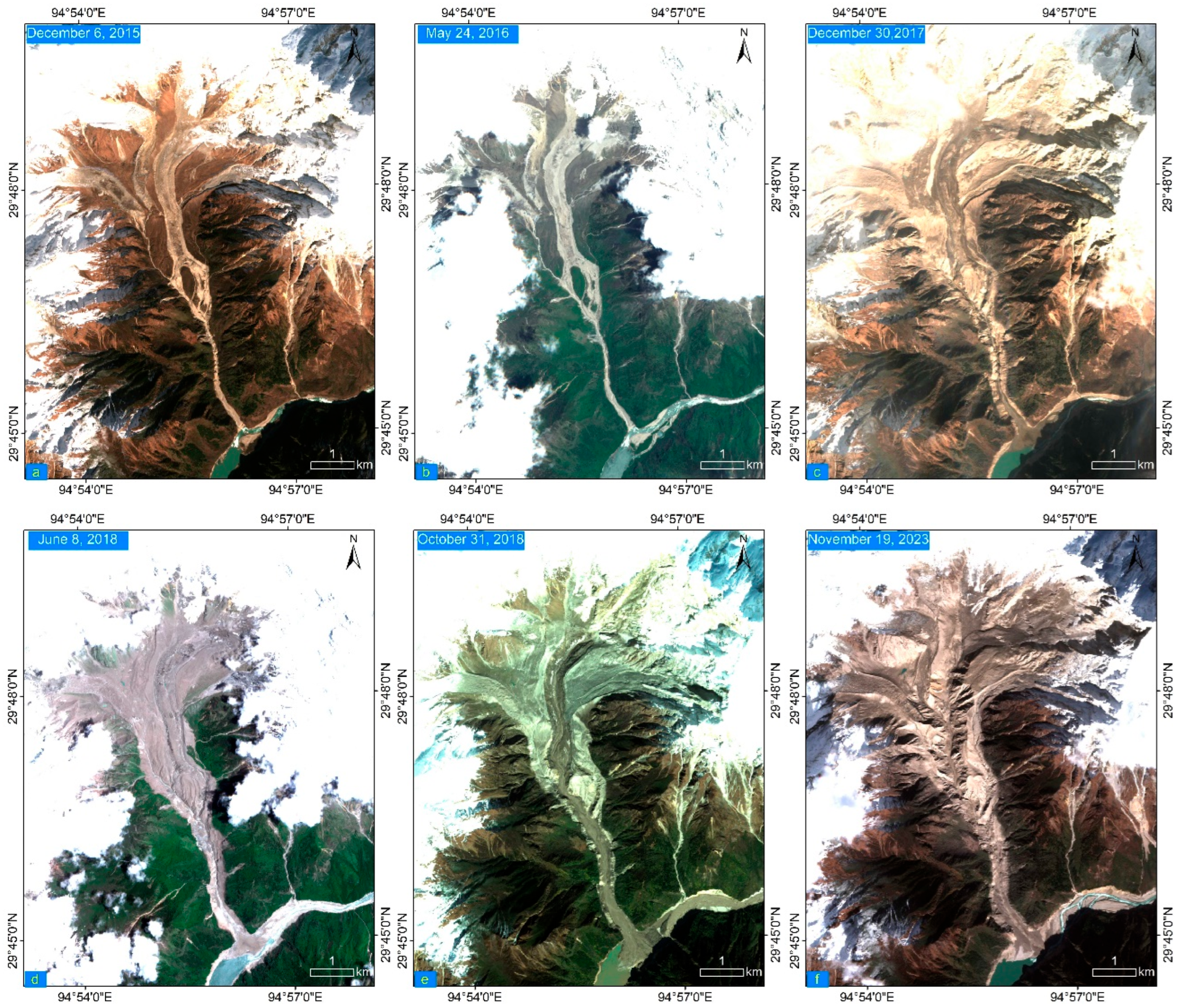

3.1. Arutso Glacier Avalanche

3.1.1. Review of the Event

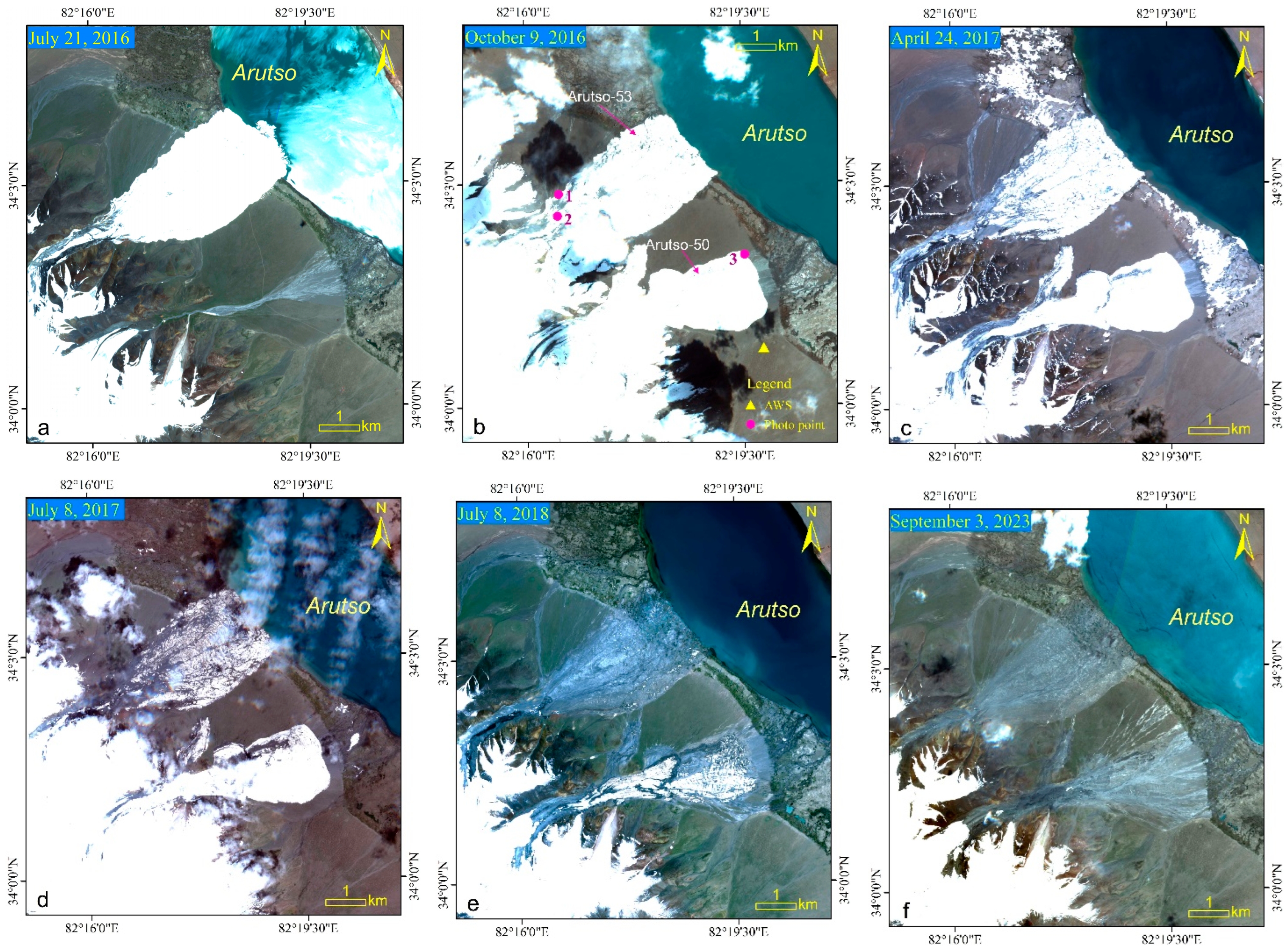

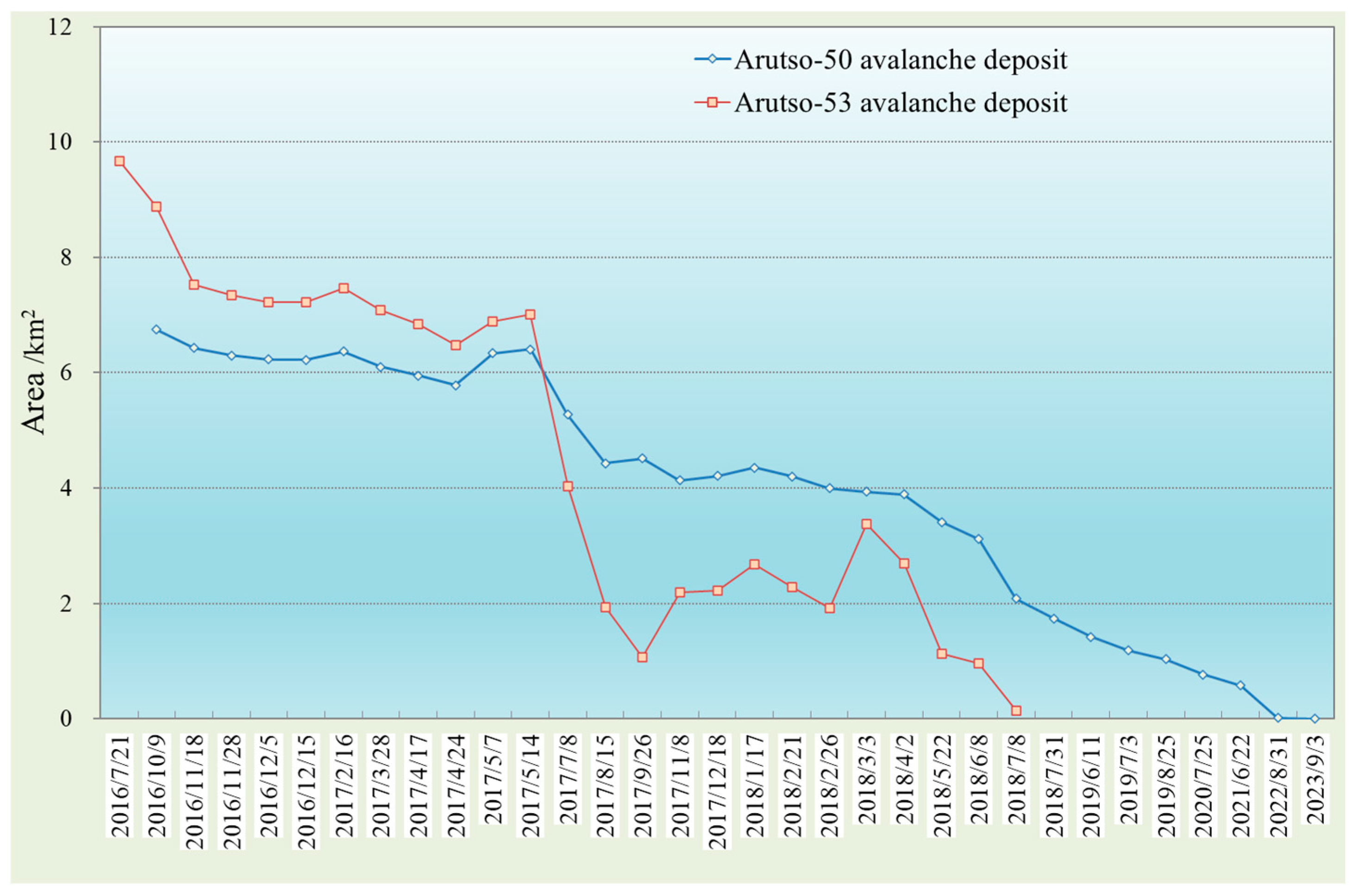

3.1.2. Satellite Observation

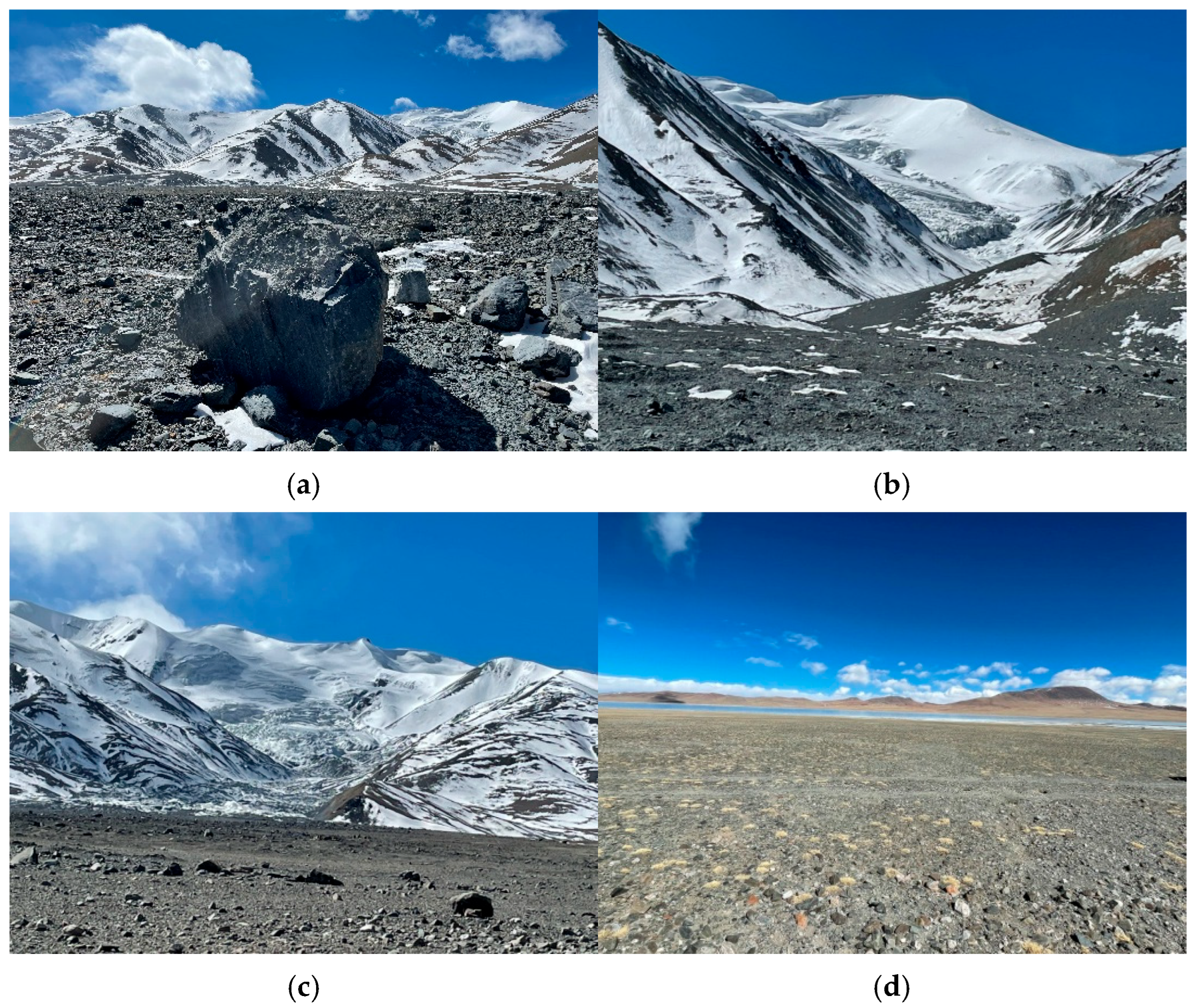

3.1.3. Field Investigation

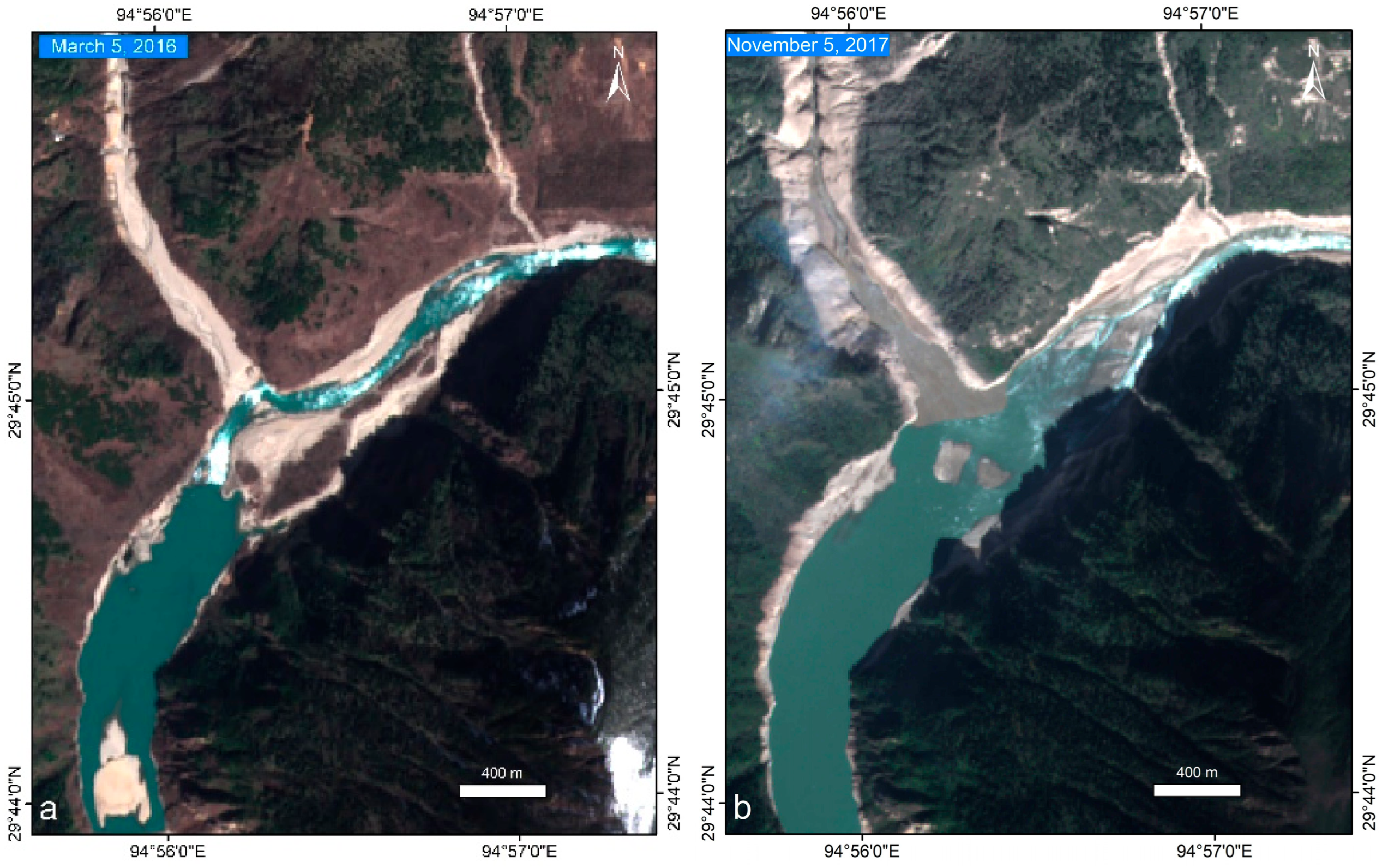

3.2. Sedongpu Ice-Rock Avalanches

3.2.1. Satellite Observation

3.2.2. Field Investigation

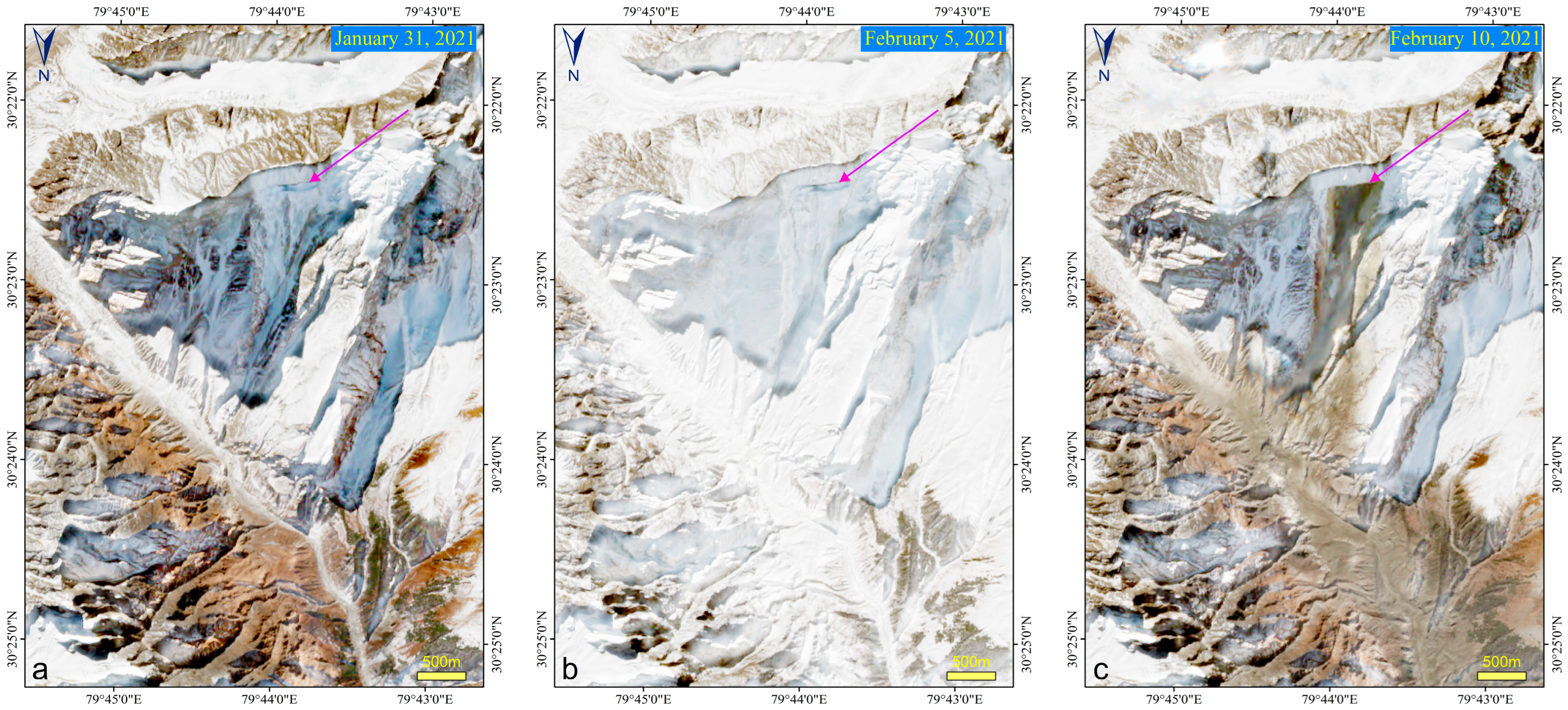

3.3. Chamoli Rock-Ice Avalanche

3.3.1. Review of the Event

3.3.2. Satellite Observation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Recommendation

- (1)

- Arutso twin glacier avalanches occurred after the lower part of the glaciers detached on the slope of the mountains, and these are typical low-angle glacier detachments in the high mountain region. The Arutso-53 avalanche deposit completely melted away in July 2018 in 2 years, while the Arutso-50 avalanche deposit melted by the end of August 2023 after lasting for 7 years. With mass accumulation and development, the Arutso-53 glacier is likely to occur again in the future.

- (2)

- In 2017 and 2018, four large-scale ice-rock avalanches and debris flows in the Sedongpu basin not only had a significant impact on the landscape and geomorphological conditions in the basin, but also resulted in disaster chains in the basin and downstream. Another catastrophic mass flow in the southern slope of the Himalayas cannot be ruled out for the future.

- (3)

- There is no single triggering factor for glacier and ice-rock avalanches in the TP, which are caused by temperature anomalies, heavy precipitation, climate warming, seismic activity, topography, thermal conditions of the ice body, etc., and are the combined effect of several factors.

- (4)

- Under continuous global climate warming and the overall warming and wetting environment in the TP, cryospheric hazards tend to intensify. With more human activities in the high mountain regions, relevant hazard risk and losses tend to increase. Monitoring the characteristics and evolutionary processes of mass flow and related hazard chains are important for hazard prevention and reduction. This study highlights that science and technology advances should support remote and vulnerable mountain communities and make them suffer less from natural hazards through mountain hazard detection and early warning systems.

- (5)

- To reduce potential hazard risks of the mountain cryosphere in the future, it is recommended to carry out comprehensive hazard risk surveys in the high mountain regions in the TP and surroundings, strengthen transboundary cooperation and enhance remote sensing and ground-based observations, and build monitoring and early warning systems. In the future, the high mountain regions in the southeastern Tibet and southern Himalayas remain the primary focus for cryospheric hazards, such as ice-rock avalanches, avalanches, and glacial lake outbursts, which will be research priorities.

- (6)

- In addition to Sentinel-2 data, the application of commercial satellite data is an important option for the global environmental and hazard monitoring and emergency response. Among these, the U.S. Planet Company has the world’s largest commercial fleet of Earth observation satellites, providing users with rapidly updated, customized high-resolution commercial satellite imagery. Planet Company came up with “using space to help life on Earth” and its mission is to “image the entire Earth every day, and make global change visible, accessible, and actionable”.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shugar, D.H.; Jacquemart, M.; Shean, D.; Bhushan, S.; Upadhyay, K.; Sattar, A.; Schwanghart, W.; Mcbride, S.; Vries, M.; Mergili, M.; et al. A massive rock and ice avalanche caused the 2021 disaster at Chamoli, Indian Himalaya. Science 2021, 373, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargel, J.S.; Leonard, G.J.; Shugar, D.H.; Haritashya, U.K.; Bevington, A.; Fielding, E.J.; Fujita, K.; Geertsema, M.; Miles, E.S.; Steiner, J.; et al. Geomorphic and geologic controls of geohazards induced by Nepal’s 2015 Gorkha earthquake. Science 2015, 351, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, L.; Purves, R.S.; Huggel, C.; Noetzli, J.; Haeberli, W. On the influence of topographic, geological and cryospheric factors on rock avalanches and rockfalls in high-mountain areas. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, R.; Rasul, G.; Adler, C.; Cáceres, B.; Gruber, S.; Hirabayashi, Y.; Jackson, M.; Kääb, A.; Kang, S.; Kutuzov, S.; et al. High Mountain Areas. In IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 131–202. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, T.; Xue, Y.; Chen, D.; Chen, F.; Thompson, L.; Cui, P.; Koike, T.; William, K.; Lettenmaier, D.; Mosbrugger, V.; et al. Recent third pole’s rapid warming accompanies cryospheric melt and water cycle intensification and interactions between monsoon and environment: Multidisciplinary approach with observations, modeling, and analysis. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 2019, 100, 423–444. [Google Scholar]

- Immerzeel, W.W.; Van Beek, L.P.H.; Bierkens, M.F.P. Climate change will affect the Asian water towers. Science 2010, 328, 1382–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherji, A.; Sinisalo, A.; Nüsser, M.; Garrard, R.; Eriksson, M. Contributions of the cryosphere to mountain communities in the Hindu Kush Himalaya: A review. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2019, 19, 1311–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, G.; Allen, S.K.; Bao, A.; Ballesteros-Cánovas, A.J.; Huss, M.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Yuan, Y.; Jiang, L.; Yu, T.; et al. Increasing risk of glacial lake outburst floods from future Third Pole deglaciation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 411–417. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, T.; Bolch, T.; Chen, D.; Gao, J.; Immerzeel, W.; Piao, S.; Su, F.; Thompson, L.; Wada, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. The imbalance of the Asian water tower. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Guo, W.; Qiu, B.; Xue, Y.; Hsu, P.; Wei, J. Influence of Tibetan Plateau snow cover on East Asian atmospheric circulation at medium-range time scales. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Yu, W.; Wu, G.; Xu, B.; Yang, W.; Zhao, H.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; Wang, N.; Li, Z.; et al. Glacier anomalies and relevant disaster risks on the Tibetan Plateau and surroundings. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2019, 64, 2770–2782. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Yao, T.; Wang, W.; Zhao, H.; Yang, W.; Zhang, G.; Li, H.; Yu, W.; Lei, Y.; Hu, W. Glacial hazards on Tibetan Plateau and surrounding alpines. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2019, 34, 1285–1292. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, A.; Immerzeel, W.; Shrestha, A.; Bierkens, M. Consistent increase in High Asia’s runoff due to increasing glacier melt and precipitation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z. Snow cover on the Tibetan Plateau and topographic controls. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Lu, X.; Walling, D.E.; Zhang, T.; Steiner, J.F.; Wasson, R.J.; Harrison, S.; Nepal, S.; Nie, Y.; Immerzeel, W.W. High Mountain Asia hydropower systems threatened by climate-driven landscape instability. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D. Remote Sensing of Land Use and Land Cover in Mountain Region; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Xiao, C. Global cryospheric disaster at high risk areas: Impacts and trend. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2019, 64, 891–901. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, B.; Gao, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhao, C.; Liu, X. Remote sensing interpretation of development characteristics of high-position geological hazards in Sedongpu gully, downstream of Yarlung Zangbo River. Chin. J. Geol. Haz. Control 2021, 32, 33–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chai, B.; Tao, Y.; Du, J.; Huang, P.; Wang, W. Hazard assessment of debris flow triggered by outburst of Jialong glacial lake in Nyalam County, Tibet. Earth Sci. 2020, 45, 4630–4639. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Qin, J.; Li, Y. Distribution and risk of ice avalanche hazards in Tibetan Plateau. Earth Sci. 2022, 47, 4447–4462. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huggel, C.; Zgraggen-Oswald, S.; Haeberli, W.; Kääb, A.; Polkvoj, A.; Galushkin, I.; Evans, S.G. The 2002 rock/ice avalanche at Kolka /Karmadon, Russian Caucasus: Assessment of extraordinary avalanche formation and mobility, and application of QuickBird satellite imagery. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2005, 5, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kääb, A.; Wessels, R.; Haeberli, W.; Huggel, C.; Kargel, J.S.; Khalsa, S.J. Rapid imaging facilitates timely assessment of glacier hazards and disasters. Eos Trans. Amer. Geophys. Union. 2003, 84, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P. Inventory of rock glaciers in Himachal Himalaya, India using high-resolution Google Earth imagery. Geomorphology 2019, 340, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhambri, R.; Hewitt, K.; Kawishwar, P.; Pratap, B. Surge-type and surge-modified glaciers in the Karakoram. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farinotti, D.; Immerzeel, W.W.; Kok, R.J.; Quincey, D.J.; Dehecq, A. Manifestations and mechanisms of the Karakoram glacier anomaly. Nat. Geosci. 2020, 13, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goerlich, F.; Bolch, T.; Paul, F. More dynamic than expected: An updated survey of surging glacier in the Pamir. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 3161–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhambri, R.; Watson, C.S.; Hewitt, K.; Haritashya, U.; Kargel, J.; Shahi, A.; Chand, P.; Kumar, A.; Verma, A.; Govil, H. The hazardous 2017–2019 surge and river damming by Shispare Glacier, Karakoram. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhakpa, D.; Fan, Y.; Cai, Y. Continuous Karakoram glacier anomaly and its response to climate change during 2000–2021. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazai, N.A.; Cui, P.; Carling, P.A.; Wang, H.; Hassan, J.; Liu, D.; Zhang, G.; Jin, W. Increasing glacial lake outburst flood hazard in response to surge glaciers in the Karakoram. Earth Sci. Rev. 2021, 212, 103432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kääb, A. Monitoring high-mountain terrain deformation from repeated air-and spaceborne optical data: Examples using digital aerial imagery and ASTER data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2002, 57, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, W.; An, B.; Wei, L. Enhanced glacial lake activity threatens numerous communities and infrastructure in the Third Pole. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yao, T.; Tian, L.; Sheng, Y.; Zhu, L.; Liao, J.; Zhao, H.; Yang, W.; Yang, K.; Berthier, E. Response of downstream lakes to Aru glacier collapses on the western Tibetan Plateau. Cryosphere 2021, 15, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Liu, S.; Xu, J.; Wu, L.; Shangguan, D.; Yao, X.; Wei, J.; Bao, W.; Yu, P.; Liu, Q. The second Chinese glacier inventory: Data, methods and results. J. Glaciol. 2015, 61, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolch, T.; Kulkarni, A.; Kääb, A.; Huggel, C.; Paul, F.; Cogley, F.G.; Frey, H.; Kargel, J.S.; Fujita, K.; Scheel, M. The state and fate of Himalayan Glaciers. Science 2012, 336, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Thompson, L.; Yang, W.; Yu, W.; Gao, Y.; Guo, X.; Yang, X.; Duan, K.; Zhao, H.; Xu, B.; et al. Different glacier status with atmospheric circulations in Tibetan Plateau and surroundings. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lü, J.; Tong, L.; Chen, H.; Liu, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Tu, J. Research on glacial/rock fall-landslide-debris flows in Sedongpu basin along Yarlung Zangbo River in Tibet. Geol. Chin. 2019, 46, 219–234. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- An, B.; Wang, W.; Yang, W.; Wu, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, H.; Gao, Y.; Bai, L.; Zhang, F.; Zeng, C.; et al. Process, mechanisms, and early warning of glacier collapse-induced river blocking disasters in the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon, southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 816, 151652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, L.; Tu, J.; Pei, L.; Guo, Z.; Zheng, X.; Fan, J.; Zhong, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, S.; He, P.; et al. Preliminary discussion of the frequently debris flow events in Sedongpu Basin at Gyalaperi peak, Yarlung Zangbo River. J. Eng. Geol. 2018, 26, 1552–1561. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Sam, L. Reconstruction and characterisation of past and the most recent slope failure events at the 2021 rock-ice avalanche site in Chamoli, Indian Himalaya. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Mehta, M.; Mishra, A.; Trivedi, A. Temporal fluctuations and frontal area change of Bangni and Dunagiri glaciers from 1962 to 2013, Dhauliganga basin, central Himalaya, India. Geomorphology 2017, 284, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drusch, M.; Del Bello, U.; Carlier, S.; Colin, O.; Fernandez, V.; Gascon, F.; Hoersch, B.; Isola, C.; Laberinti, P.; Martimort, P.; et al. Sentinel-2: ESA’s optical high-resolution mission for GMES operational services. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschbacher, J.; Milagro-Pérez, M.P. The European Earth monitoring (GMES) programme: Status and perspectives. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baetens, L.; Desjardins, C.; Hagolle, O. Validation of Copernicus Sentinel-2 cloud masks obtained from MAJA, Sen2Cor, and FMask processors using reference cloud masks generated with a supervised active learning procedure. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, R.; Louis, J.; Berthelot, B. Sentinel-2 MSI–Level 2A Products Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document; VEGA Space GmbH: Darmstadt, Germany, 2011; pp. 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, M.; Moreno, J.; Johannessen, J.A.; Levelt, P.F.; Hanssen, R.F. ESA’s sentinel missions in support of Earth system science. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagolle, O.; Huc, M.; Pascual, D.V.; Dedieu, G. A multi-temporal method for cloud detection, applied to FORMOSAT-2, VENµS, LANDSAT and SENTINEL-2 images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 1747–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, S.; Woodcock, C.E. Improvement and expansion of the FMask algorithm: Cloud, cloud shadow, and snow detection for Landsats 4-7, 8, and Sentinel 2 images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 159, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.K.; Riggs, G.A.; Salomonson, V.V. Theoretical Basic Document (ATBD) for the MODIS Snow and Sea Ice-Mapping Algorithms. 2001. Available online: http://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/data/atbd/atbd_mod10.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Hall, D.K.; Riggs, G.A.; Salomonson, V.V. Development of methods for mapping global snow cover using Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer data. Remote Sens. Environ. 1995, 54, 27–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.K.; Riggs, G.A.; Salomonson, V.V.; DiGirolamo, N.E.; Bayr, K.J. MODIS snow-cover products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Yao, T.; Gao, Y.; Thompson, L.; Thompson, E.M.; Muhammad, S.; Zong, J.; Wang, C.; Jin, S.; Li, Z. Two glaciers collapse in western Tibet. J. Glaciol. 2017, 63, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kääb, A.; Leinss, S.; Gilbert, A.; Bühler, Y.; Gascoin, S.; Evans, S.G.; Bartelt, P.; Berthier, E.; Brun, F.; Chao, W. Massive collapse of two glaciers in western Tibet in 2016 after surge-like instability. Nat. Geosci. 2018, 11, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, J.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, K. Glacier variations at Arutso in western Tibet from 1971 to 2016 derived from remote-sensing data. J. Glaciol. 2018, 64, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhao, B.; Xu, Q.; Xu, Q.; Scaringi, G.; Lu, H.; Huang, R. More frequent glacier-rock avalanches in Sedongpu gully are blocking the Yarlung Zangbo River in eastern Tibet. Landslides 2022, 19, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, T.; He, J. Barrier lake bursting and flood routing in the Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon in October 2018. J. Hydrol. 2020, 583, 124603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Yang, W.; Westoby, M.; An, B.; Wu, G.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Dunning, S. An approximately 50 M m3 ice-rock avalanche on 22 March 2021 in the Sedongpu valley, southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Cryosphere 2022, 16, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Pritchard, H.D.; Liu, Q.; Hennig, T.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Nepal, S.; Samyn, S.; Hewitt, K.; et al. Glacial change and hydrological implications in the Himalaya and Karakoram. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, K.B.; Evans, S.G. The 2000 Yigong landslide (Tibetan Plateau), rockslide-dammed lake and outburst flood: Review, remote sensing analysis, and process modelling. Geomorphology 2015, 246, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.L.; Rittger, K.; Brodzik, M.J.; Racoviteanu, A.; Barrett, A.P.; Khalsa, S.; Raup, B.; Hill, A.F.; Khan, A.L.; Wilson, A.M.; et al. Runoff from glacier ice and seasonal snow in High Asia: Separating melt water sources in river flow. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2019, 19, 1249–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S.; Tian, L. Changes in the ablation zones of glaciers in the western Himalaya and the Karakoram between 1972 and 2015. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 187, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaijenbrink, P.D.A.; Stigter, E.E.; Yao, T.; Immerzeel, W.W. Climate change decisive for Asia’s snow meltwater supply. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, Y.; Gao, X. Increase in occurrence of large glacier-related landslides in the high mountains of Asia. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kääb, A.; Jacquemart, M.; Gilbert, A.; Leinss, S.; Girod, L.; Huggel, C.; Falaschi, D.; Ugalde, F.; Petrakov, D.; Chernomorets, S.; et al. Sudden large-volume detachments of low-angle mountain glaciers–more frequent than thought? Cryosphere 2021, 15, 1751–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, B.; Yang, X. Glaciers in Tibet; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1986. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.J. Identification of glaciers with surge characteristics on the Tibetan Plateau. Ann. Glaciol. 1992, 16, 168–172. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Li, B.; Gao, Y.; Gao, H.; Yin, Y. Massive glacier-related geohazard chains and dynamics analysis at the Yarlung Zangbo River downstream of southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y. Dynamic processes of 2018 Sedongpu landslide in Namcha Barwa-Gyala Peri massif revealed by broadband seismic records. Landslides 2020, 17, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. Study on the barrier lake event for landslide-river blocking of Sedongpu valley on Yarlung Zangbo River in Tibet of China. J. Hebei Geo Univ. 2020, 43, 31–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chu, D.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Nie, Y.; Zhang, Y. Snow avalanche hazards and avalanche-prone area mapping in Tibet. Geosciences 2024, 14, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Band Number | Central Wavelength/nm | Bandwidth/nm | Spatial Resolution/m | Main Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band 1—Coastal and aerosol | 443 | 20 | 60 | Atmospheric correction |

| Band 2—Blue | 490 | 65 | 10 | Sensitive to vegetation and aerosol scattering |

| Band 3—Green | 560 | 35 | 10 | Green peak, sensitive to total chlorophyll in vegetation |

| Band 4—Red | 665 | 30 | 10 | Max chlorophyll absorption |

| Band 5—Vegetation red edge 1 | 705 | 15 | 20 | Vegetation detection |

| Band 6—Vegetation red edge 2 | 740 | 15 | 20 | Vegetation detection |

| Band 7—Vegetation red edge 3 | 783 | 20 | 20 | Vegetation detection |

| Band 8—NIR | 842 | 115 | 10 | Leaf Area Index (LAI) |

| Band 8a—Narrow NIR | 865 | 20 | 20 | Used for water vapor absorption reference |

| Band 9—Water vapor | 940 | 20 | 60 | Water vapor absorption atmospheric correction |

| Band 10—SWIR-cirrus | 1375 | 30 | 60 | Detection of thin cirrus for atmospheric correction |

| Band 11—SWIR1 | 1610 | 90 | 20 | Snow and cloud detection |

| Band 12—SWIR2 | 2190 | 180 | 20 | AOT (aerosol optical thickness) determination |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chu, D.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z. The Evolution and Impact of Glacier and Ice-Rock Avalanches in the Tibetan Plateau with Sentinel-2 Time-Series Images. GeoHazards 2026, 7, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010010

Chu D, Liu L, Wang Z. The Evolution and Impact of Glacier and Ice-Rock Avalanches in the Tibetan Plateau with Sentinel-2 Time-Series Images. GeoHazards. 2026; 7(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Duo, Linshan Liu, and Zhaofeng Wang. 2026. "The Evolution and Impact of Glacier and Ice-Rock Avalanches in the Tibetan Plateau with Sentinel-2 Time-Series Images" GeoHazards 7, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010010

APA StyleChu, D., Liu, L., & Wang, Z. (2026). The Evolution and Impact of Glacier and Ice-Rock Avalanches in the Tibetan Plateau with Sentinel-2 Time-Series Images. GeoHazards, 7(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/geohazards7010010