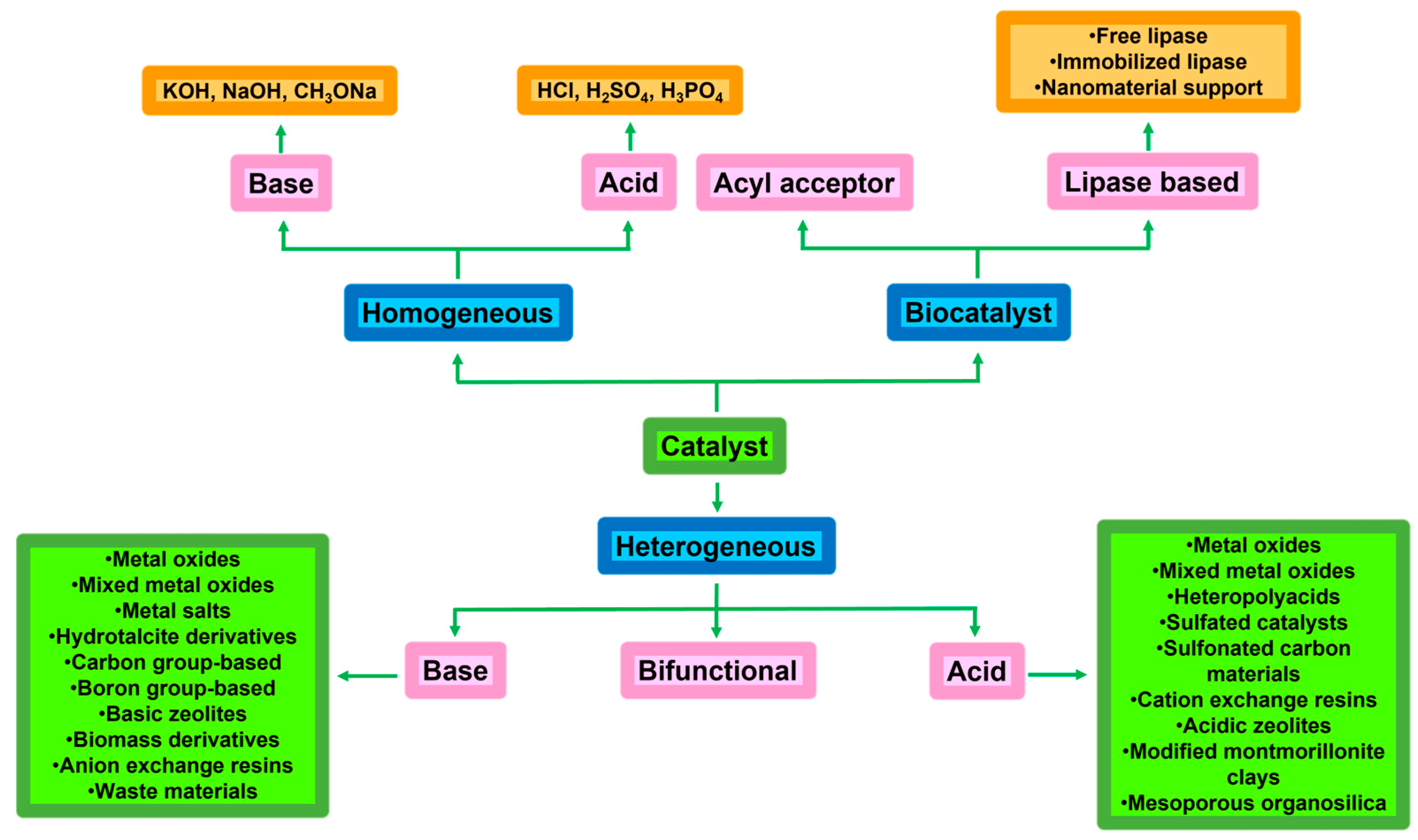

4.1. Biodiesel Production Catalysed by Basic Catalysts

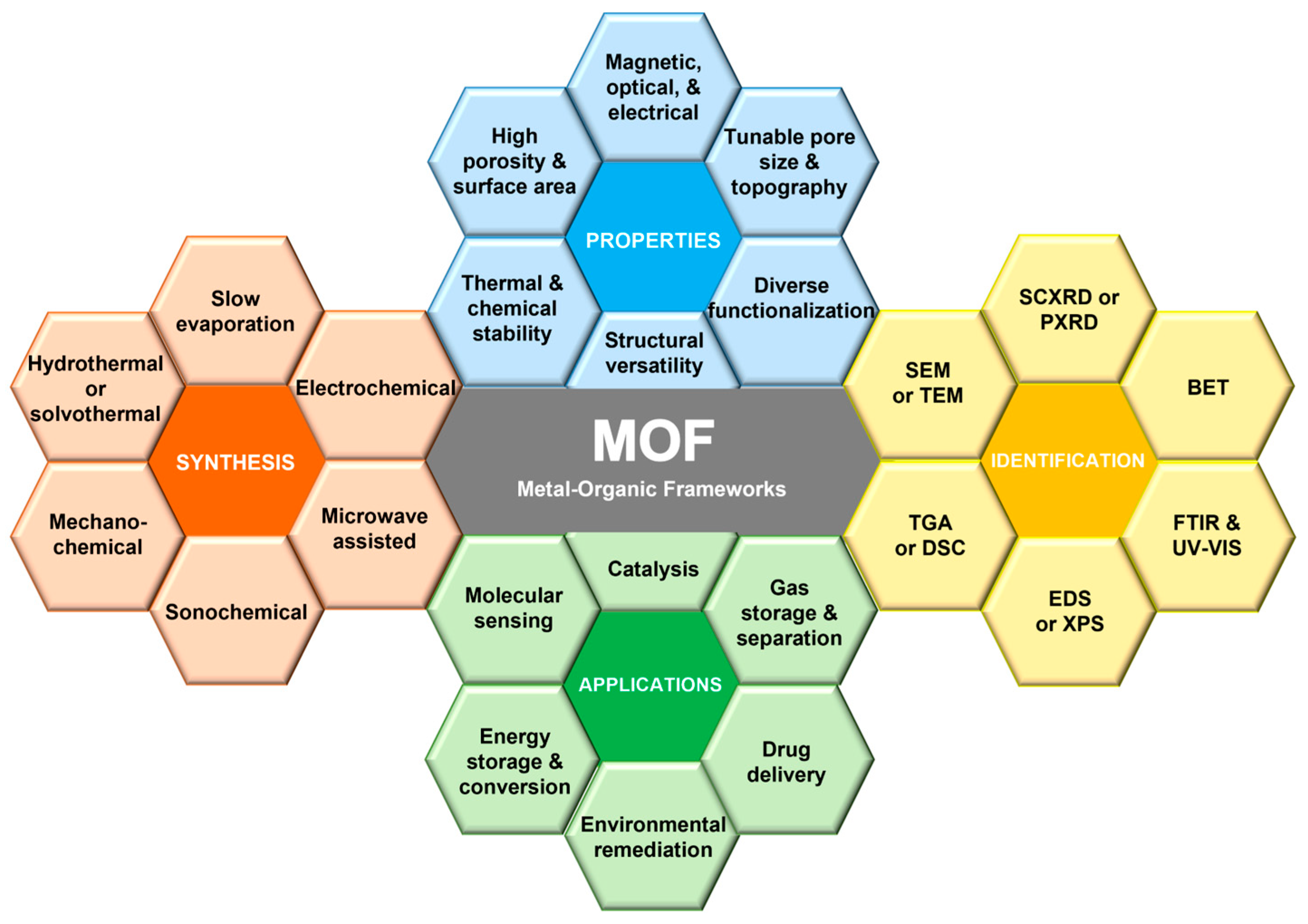

MOF-based basic catalysts provide precise control of structure and functionality at the atomic level, allowing for improved distribution of active sites and greater stability compared to traditional catalysts. Organic ligands containing Lewis bases can be used in these heterogeneous materials, enabling the design of MOFs with basic properties that facilitate biodiesel production. The porosity and high surface area of MOFs allow for improved diffusion and distribution of reactants in the active sites. MOFs maintain fixed active sites, reducing leaching and enabling reuse. The crystalline nature of MOFs allows for controlled geometry, offering predictable molecular interactions for more efficient catalysis.

MOFs are ideal precursors for synthesising novel catalysts with homogeneously arranged active sites and high surface areas. Integrating different MOFs to develop heterostructured bimetallic MOFs using the MOF-on-MOF strategy has become an area of interest. Therefore, Wang et al. (2024) designed a new MOF called CaFe-800-1 utilising this strategy. They placed Ca-BTC on MIL-100(Fe) using the epitaxial growth method. MIL-100(Fe) consists of Fe

3+-O cationic clusters and trimesate anions, while Ca-BTC consists of Ca

2+ cations and trimesate anions. Unlike monometallic MOFs, the MOF-on-MOF strategy improves the catalyst properties due to the synergistic interactions between the two metals at the atomic level. The new bimetallic MOF was used as a precursor to obtain a novel magnetic catalyst based on CaO, which was subsequently applied in the transesterification reaction for biodiesel production. The authors found an optimal calcination temperature of 800 °C and an optimal Ca/Fe mass ratio of 1. These parameters achieve a total basicity of 0.33 mmol/g and a transesterification conversion of 96.45%. The structural properties of CaFe-800-1 with these parameters were: catalyst surface area of 249.04 m

2/g, pore volume of 0.70 cm

3/g, and average pore diameter of 11.66 nm. This new catalyst exhibited a maximum catalytic activity, determined by FT-IR, of 98.53% using 6 wt% catalyst and a methanol/palm oil molar ratio of 12:1 in 1 h at 65 °C. According to the analyses, Ca

2Fe

2O and CaO were the predominant active sites, providing numerous basic transesterification sites. CaFe-800-1 was easily separated from the reaction system by magnetisation, and the resulting biodiesel met EN 14214 [

87] and ASTM D6751 [

88] quality standards. CaFe-800-1 showed good reusability, as the conversion percentage decreased from 98.53% to 92.29% after three cycles and reached 77.03% after six cycles. CaFe-800-1 achieved 86.27% and 85.35% conversions with a water content of 11 wt% and FFAs of 9 wt%, respectively [

89] (

Figure 7).

MIL-100(Fe) is a thermodynamically stable, biocompatible, magnetic, and environmentally friendly MOF with a zeolite-MTN (mordenite, triangle, and nesosilicate) structure that defines the distribution of active sites. Furthermore, CaO is a heterogeneous alkaline compound widely used as a catalyst in transesterification. However, the leaching of CaO decreases its stability, which remains a significant challenge in biodiesel production. Therefore, to improve the catalytic activity of CaO, MIL-100(Fe) was used as a support for Ca(OAc)

2, which was then activated under a nitrogen atmosphere. Adding 10 wt% of Ca(OAc)

2 and an activation temperature of 750 °C led to the production of the catalyst known as CAM750, which exhibited good catalytic activity as determined by FTIR-ATR spectroscopy. CAM750 achieved a maximum conversion of 95.07% with a methanol/palm oil molar ratio of 9:1 and a catalyst loading of 4 wt% at a reaction temperature of 65 °C for 2 h. The active sites of the catalyst are formed by CaFe

3O

5 and Ca

2Fe

2O

5 crystals. CAM750 exhibited a saturation magnetisation of 112 emu/g, making it easily separated from the reaction mixture with a magnet. The high specific surface area (90.01 m

2/g), pore volume (0.24 cm

3/g), and pore diameter (7.61 nm) of CAM750 contribute to its good catalytic activity. Furthermore, the deactivation of CAM750 was induced by blocking the active sites and not by Ca

2+ leaching and deterioration of the CaFe

3O

5 and Ca

2Fe

2O

5 active sites. Oil conversion decreased from 95.07% to 80.09% from the first to the third cycle, reaching 62.51% in the fourth cycle. However, if CAM750, used for four cycles, is isolated, washed, and dried, the conversion rate remains at 93.86% [

90].

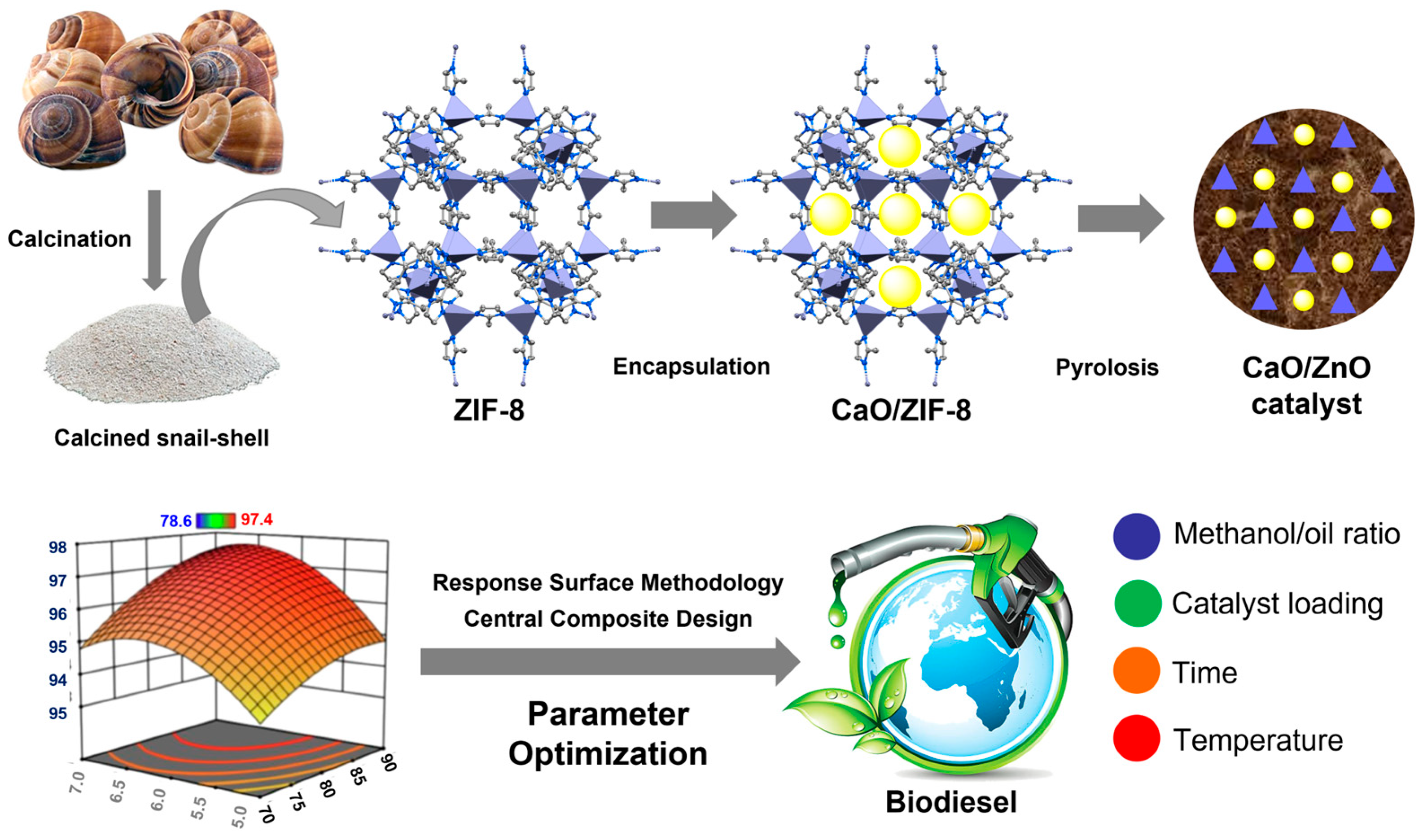

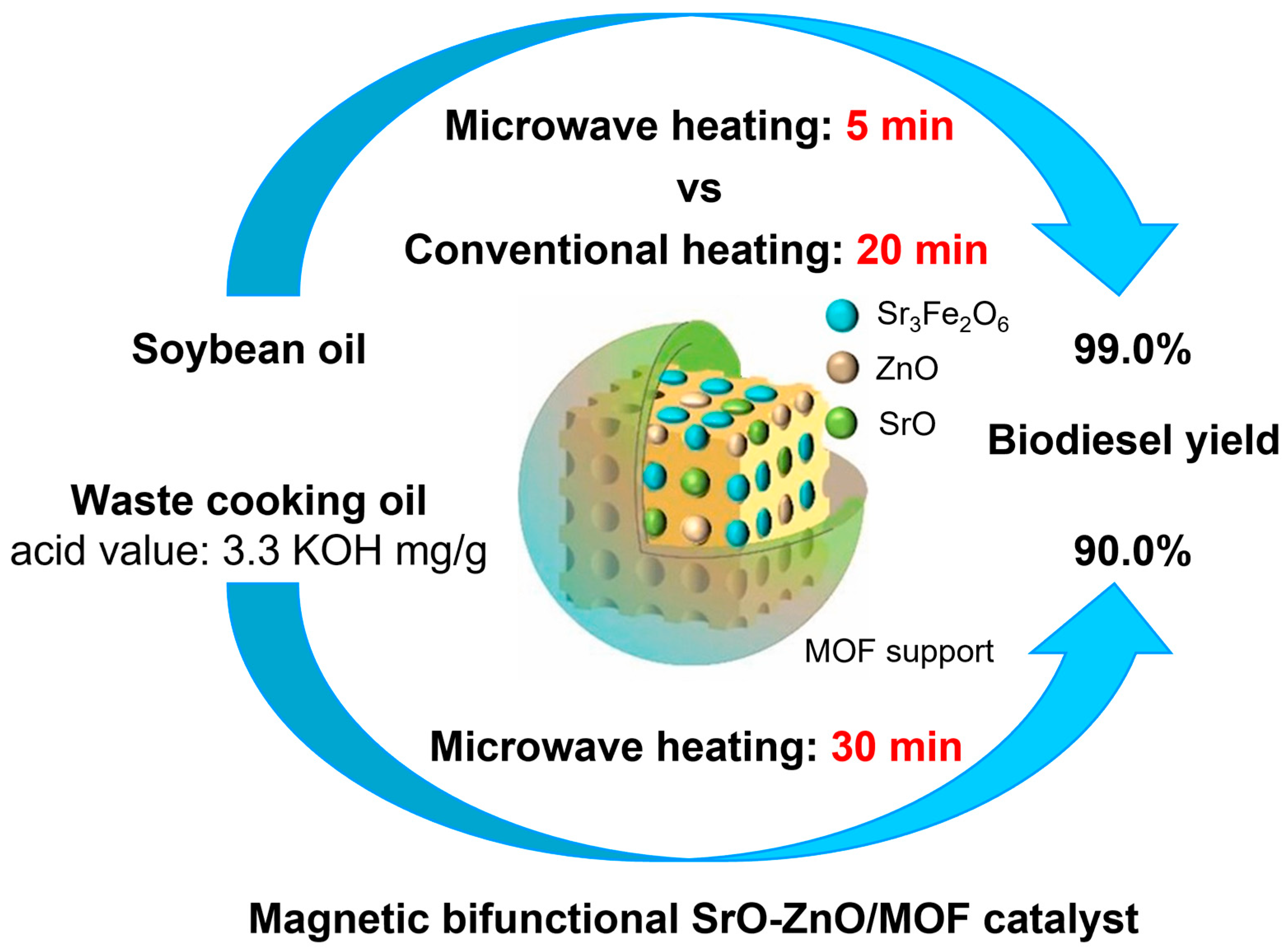

Microwave irradiation has also been used in biodiesel production, as it is cost-effective, energy-efficient, and environmentally friendly. Based on this, Ruatpuia et al. (2023) developed a synthetic approach for the synthesis of CaO/ZnO nanocomposites obtained from CaO, obtained from biomass waste (snail shell), and ZIF-8, by pyrolysis at 800 °C for 2 h. ZIF-8 is a catalyst comprising 2-methylimidazolate anions (organic ligands) and Zn

2+ cations (metal nodes). The nitrogen atoms in ZIF-8 promote the immobilisation of calcium(II) precursors, such as Ca(OH)

2, while the microporosity of ZIF-8 limits the subsequent development of CaO nanoparticles. This novel catalyst containing CaO and ZnO was used to convert soybean oil to biodiesel, optimising the transesterification variables using a response surface methodology (RSM) and a central composite design (CCD). The 20:1 methanol/soybean oil molar ratio and 7 wt% of CaO/ZnO loading led to a catalytic efficiency of 97.4% after transesterification for 50 min at 90 °C.

1H NMR data confirmed the conversion of soybean oil to biodiesel, while GC-MS spectra provided the chemical composition of the biodiesel obtained. Furthermore, it was shown that CaO/ZnO obtained by this technique exhibited higher catalytic activity than its physically mixed counterpart, indicating the synergic effect between the CaO and ZIF-8 precursors and the CaO/ZnO product. After calcining for 2 h at 500 °C, the catalyst was used for five more catalytic cycles. The catalyst’s fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) yield decreased from 97.4% in the first cycle to 81.6% in the fifth cycle [

91] (

Figure 8).

Currently, the poor pore structure of CaO and the leaching of Ca

2+ ions represent an obstacle to biodiesel production. On the other hand, UiO-66(Zr) is a highly thermally and chemically stable MOF, as it is based on terephthalate anions and Zr

4+ cations, specifically on the octahedral units Zr

6O

4(OH)

4. Therefore, Li et al. (2022) used this MOF to support Ca(OAc)

2 and prepare the CaO/ZrO

2 catalyst, which was subsequently activated in a nitrogen atmosphere (UCN) or air (UCA). FT-IR results revealed that the catalyst activated in a nitrogen atmosphere and calcined at 650 °C (UCN650) and the catalyst activated in an air atmosphere and calcined at 700 °C (UCA700) exhibited the best catalytic yields. UCN650 exhibited a percentage of catalytic activity of 96.99% with 6 wt% catalyst and a methanol/palm oil molar ratio of 9:1 in 60 min at 65 °C. UCA700 exhibited a catalytic activity of 92.94% with 8 wt% catalyst and a methanol/palm oil molar ratio of 9:1 in 60 min at 65 °C. These results are because UCN650 exhibits a specific surface area of 24.06 m

2/g (pore volume of 0.027 cm

3/g and pore diameter of 4.43 nm), which contains CaO and Ca

xZr

yO

x+2y active sites within it. In comparison, UCA700 had a smaller specific surface area of 3.44 m

2/g (pore volume of 0.0079 cm

3/g and pore diameter of 9.20 nm). After three cycles, UCN650’s conversion decreased from 96.99% to 92.76%, while UCA700’s conversion decreased from 92.94% to 90.54%. This study provided a new strategy to improve the catalytic activity of CaO in transesterification to produce biodiesel compliant with EN 14214 [

92].

Metal oxides are frequently combined to design new heterogeneous catalysts, in which each species works synergistically to increase catalytic yield. Metal oxides can be immobilised on suitable supports, such as MOFs, to eliminate their weaknesses and improve their stability. In this vein, Gouda et al. (2022) used CaO derived from biomass (snail shell) and supported it on ZrO

2, creating a new heterogeneous catalyst (CaO-ZrO

2) for the production of biodiesel from soybean oil. For this purpose, UiO-66 was used as a ZrO

2 precursor and a CaO template, providing a synergistic effect due to the basicity of CaO and the amphoteric nature of ZrO

2. UiO-66 is composed of Zr

6O

4(OH)

4 nodes and terephthalate ligands. Statistical optimisation of the transesterification parameters under microwave irradiation was carried out using an RSM. In addition, a CCD determined the effect of input variables (methanol/oil ratio, catalyst loading, reaction temperature, reaction time, and their interactions) on conversion and yield. After statistical optimisation, the maximum yield was 97.22 ± 0.4% and the maximum conversion was 98.03 ± 0.7% starting from a methanol/oil ratio of 9.7 wt%, a catalyst loading of 6.5 wt%, a reaction temperature of 73.2 °C, and a reaction time of 66.2 min. GC-MS and

1H and

13C NMR were used to analyse the biodiesel obtained, and it was verified that it met the physicochemical properties established by ASTM standards. After each cycle, the catalyst was activated by calcining it at 500 °C. After five transesterification cycles, the catalytic conversion decreased from 98.03% to 85.44%. The authors mention that the high basicity of the catalyst (3.9 mmol/g) triggered the transesterification of the soybean oil, resulting in a successful conversion [

93].

MIL-100(Fe) is an inexpensive material composed of cationic groups [Fe

3O(OH)(H

2O)

2]

6+ bonded by trimesate anions. This MOF is easy to synthesise and has high chemical stability, a large surface area, and excellent magnetic properties. Furthermore, its organic bonds are readily decomposed by calcination to form carbon and the corresponding metal oxides, maintaining a porous structure that prevents the aggregation of other particles. Therefore, MIL-Fe(100) was used as a precursor to Fe@C, a mesoporous magnetic material obtained by carbonisation at 600 °C in a nitrogen atmosphere. Subsequently, the SrO was loaded onto the Fe@C support using in situ titration, yielding the heterogeneous basic catalyst called Fe@C-Sr. The optimal parameters for catalyst synthesis were an activation temperature of 900 °C and 30% SrO (total basicity of 7.94 mmol/g). Under these conditions, the catalyst had a surface area of 68.93 m

2/g, a pore volume of 0.12 cm

3/g, and an average pore diameter of 7.07 nm. The optimal parameters to achieve 98.12% catalytic activity in the transesterification were a catalyst loading of 4 wt%, a methanol/palm oil molar ratio of 9:1, and a reaction temperature and time of 65 °C and 30 min. After the reaction, Fe@C-Sr was recovered using an external magnetic field, and FTIR-ATR determined oil conversion to biodiesel. Fe@C-Sr showed good recyclability, reaching 80.59% in the fourth cycle. In addition, the Fe@C-Sr used in the fourth cycle was magnetically separated, washed in hexane, and dried at 100 °C for 6 h, achieving a conversion of 97.52% [

94].

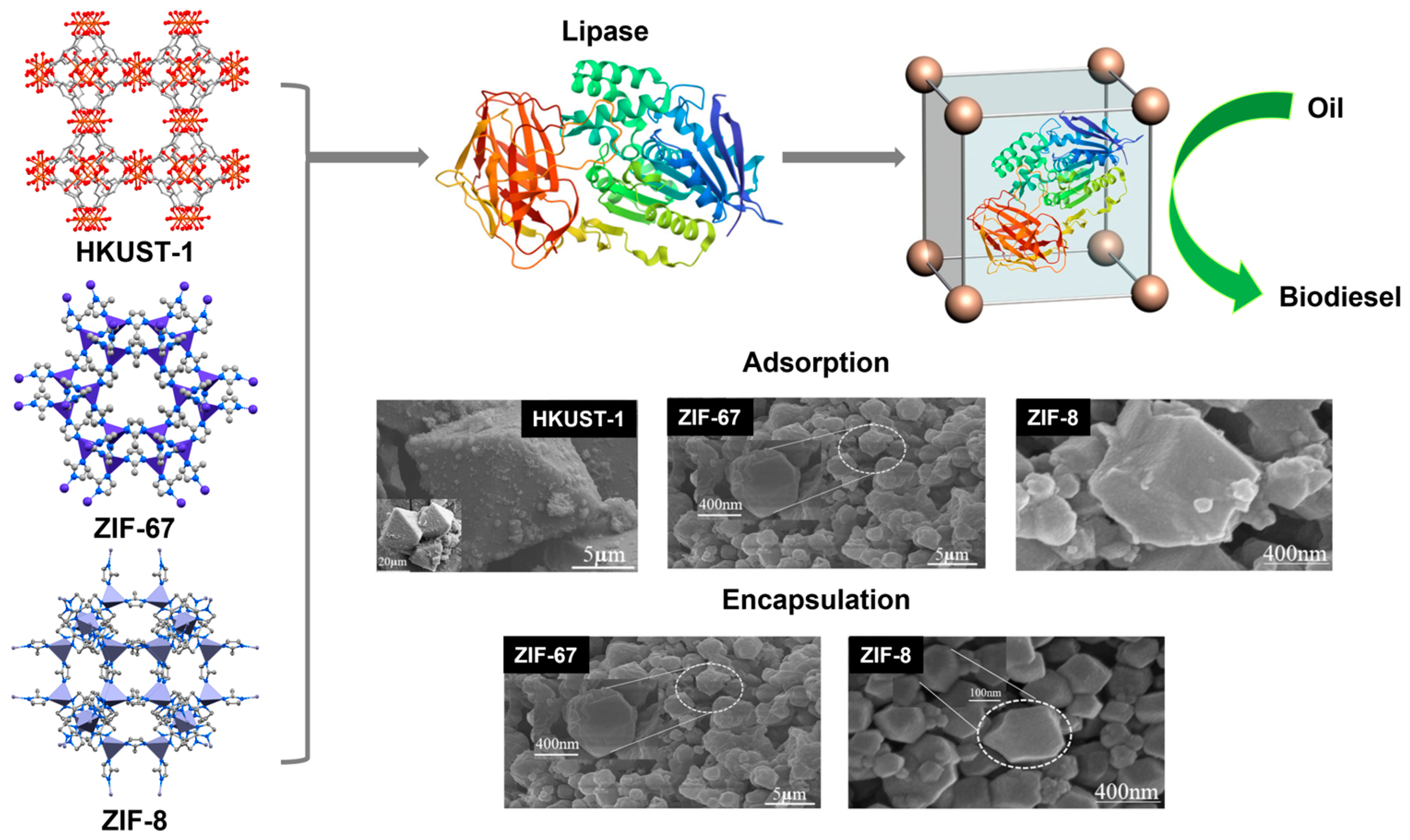

Functionalized ionic liquids (ILs) are commonly used as catalysts in organic synthesis. However, their viscosity makes it difficult to recover, limiting their application in catalysis. Therefore, using ILs supported on porous materials is an attractive and viable approach for designing efficient heterogeneous catalysts. Along these lines, Xie et al. (2018) fabricated a magnetically reusable solid catalyst for biodiesel production. To do so, they designed a magnetically responsive core–shell material called Fe

3O

4@HKUST-1 using a layer-by-layer assembly technique. This hybrid nanocomposite comprises a magnetic core (Fe

3O

4) coated with a porous structure (HKUST-1). In turn, HKUST-1, also known as MOF-177, is composed of Cu

2+ ions and trimesic acid, while the Fe

3O

4 magnetic nanoparticles, also known as magnetite, are composed of mixed iron oxide (Fe

2+ and Fe

3+). Before forming Fe

3O

4@HKUST-1, the magnetite was functionalized using mercaptoacetic acid (MAA) to obtain carboxyl-modified magnetite (MAA-Fe

3O

4). Subsequently, the amino-functionalized basic ionic liquid-Imidazole (ABIL-Im) was encapsulated within Fe

3O

4@HKUST-1, obtaining a hybrid solid catalyst called Fe

3O

4@HKUST-1-ABILs. It is important to note that ABIL-Im was previously prepared from 1-methylimidazole, 2-bromoethylamine hydrobromide, and imidazole. This nanocomposite enabled transesterification with a catalytic conversion of 92.3% in 3 h at the methanol reflux temperature (64.7 °C) using a catalyst loading of 1.2 wt% and a methanol/soybean oil molar ratio of 30:1 (evaluated by GC). The catalyst exhibited superparamagnetic behaviour. It was recovered by simple magnetic decantation with an external magnetic field. Fe

3O

4@HKUST-1-ABILs was reused five times without significantly decreasing its catalytic activity (>80%) [

95] (

Figure 9).

Hybrid compounds based on MOFs and graphene allow the integration of the properties of both components, enabling the design of materials with unique properties. Therefore, Fazaeli et al. (2015) reported the catalytic activity of the nanostructured composite KNa/ZIF-8@GO in the transesterification of soybean oil for biodiesel production. KNa/ZIF-8@GO was hydrothermally synthesised and doped with potassium and sodium. Graphene oxide (GO) was obtained using the modified Hummers method, and ZIF-8@GO was prepared by adding GO to the ZIF-8 in a programmable furnace. KNa/ZIF-8@GO was obtained from a mixture of ZIF-8@GO and an alkaline solution of NaOH and KOH (9:1 molar ratio) in a Teflon-lined autoclave. Spectroscopic data showed the successful immobilisation of pristine ZIF-8 between the GO sheets. Regarding the transesterification quantification by GC, it was observed that a potassium loading of 0.05 wt% produced a maximum conversion of 98%. This process involved using 8 wt% of catalyst, a methanol/oil molar ratio of 18:1, a reaction time of 3 h, and a reaction temperature of 100 °C. The solid catalyst can be reused for at least three cycles under mild reaction conditions (yield ≈ 90%) after calcination at 300 °C [

96].

ZIFs combine the advantages of both conventional MOFs and zeolites. Nonetheless, there are few reports on catalytic studies of ZIFs in the literature. In this regard, Saeedi et al. (2016) tested the nanostructured composite KNa/ZIF-8 in the transesterification reaction for biodiesel production. To do so, they prepared ZIF-8 from Zn(NO

3)

2·6H

2O and 2-methylimidazole in a programmable furnace. They subsequently added a 10 M solution of NaOH and KOH in a 9:1 molar ratio, obtaining KNa/ZIF-8 in an ultrasonic bath. The catalytic activity of KNa/ZIF-8 in the transesterification of soybean oil was evaluated by GC, speculating that increasing the basicity would improve the catalytic performance. A 0.08 wt% potassium loading was determined to provide 98% conversion using a 10:1 methanol/oil molar ratio and 8 wt% of catalyst at 100 °C after 3.5 h. After calcination at 300 °C, the catalyst showed no significant loss of catalytic activity after three cycles (yield ≈ 95%). The results show that KNa/ZIF-8 has good catalytic activity due to its many basic sites, uniform elemental composition, high surface area, and intrinsic stability [

97].

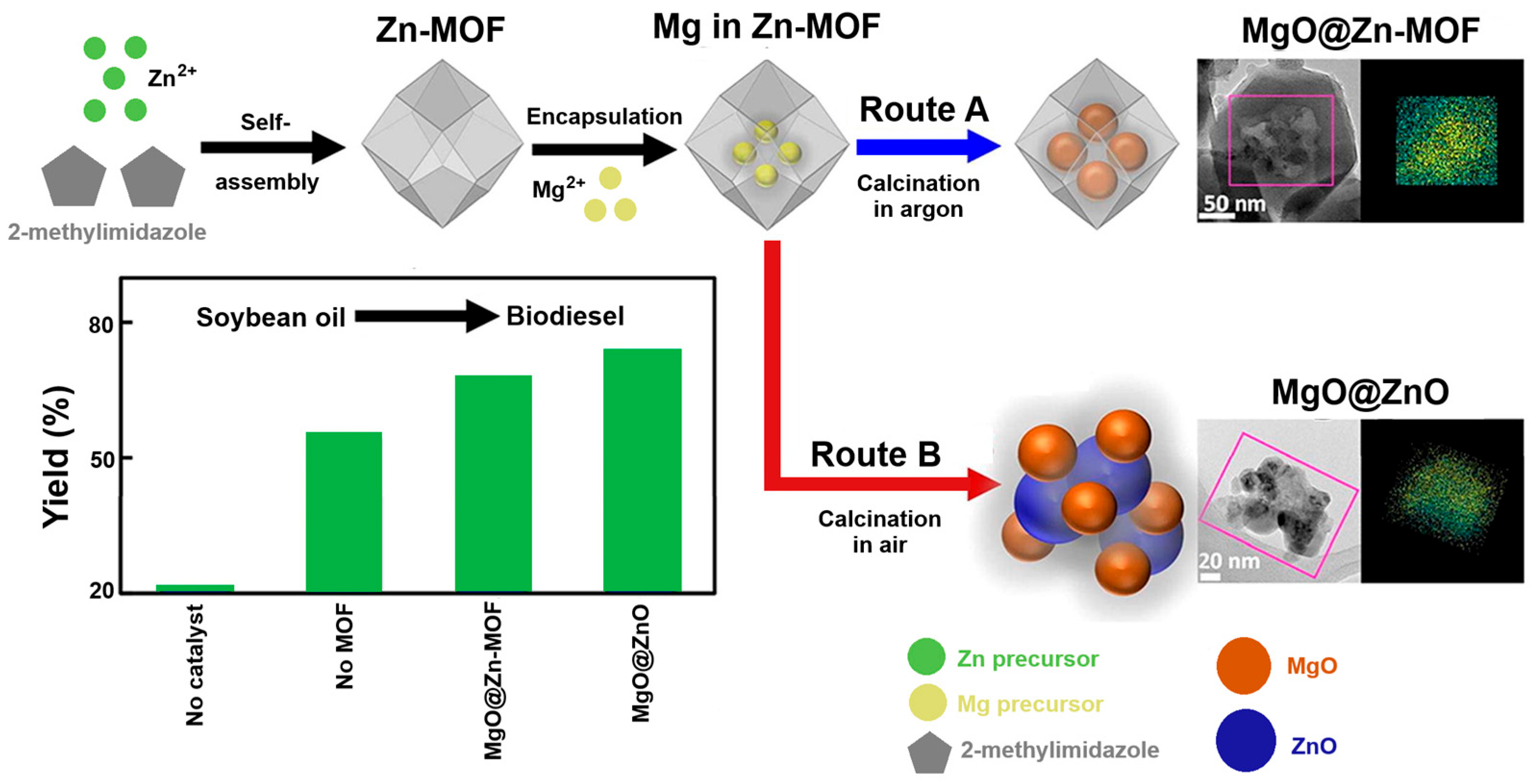

As we have seen, MOF-based hybrid nanomaterials have been used as efficient catalysts in biodiesel production; however, their mechanistic understanding has been poorly explored. Based on this, Yang et al. (2022) fabricated hybrid nanostructures derived from magnesium and zinc, which served as efficient catalysts in transesterifying soybean oil to biodiesel. Specifically, two hybrid nanostructures derived from the oxides of these two metals were obtained, which were named MgO@Zn-MOF and MgO@ZnO. On the one hand, MgO@Zn-MOF was obtained from the selective decomposition of the precursor Mg(OAc)

2·4H

2O, homogeneously encapsulated in the clusters of Zn-MOF nanocrystals by a modified incipient moisture impregnation method, where the precursor Mg(OAc)

2·4H

2O was thermally decomposed into MgO without destroying the structure of the Zn-MOF by calcination in an argon atmosphere. On the other hand, MgO@ZnO was obtained using the same technique, but calcination was carried out in an air atmosphere, causing simultaneous thermal decomposition of the Mg(OAc)

2·4H

2O precursor and the Zn-MOF, so that the MgO nanoparticles were uniformly positioned on top of the ZnO nanoparticles. In this study, the Zn-MOF refers to ZIF-8 (zeolitic imidazolate framework-8), a MOF composed of Zn

2+ ions and 2-methylimidazolate ligands. Furthermore, MgO nanoparticles (≈10 nm in MgO@ZnO and < 5 nm in MgO@Zn-MOF) were the active component of both nanostructures due to their high leaching resistance and basicity. The catalytic activity for transesterification was carried out at a methanol/soybean oil molar ratio of 3:1, 1 wt% catalyst, and analysed by GC with a flame ionisation detector. The FAME yield defined the transesterification activity. After a 2 h activity test, the FAME yield showed a value of 67.6 ± 6.2 using 20-MgO@Zn-MOF-370 (20 is the mass fraction of MgO in the catalyst and 370 is the calcination temperature). The FAME yield under the same conditions for 20-MgO@ZnO-400 (20 being the mass fraction of MgO in the catalyst and 400 being the calcination temperature) showed a value of 73.3 ± 1.3. This value was considerably higher than that obtained for the sample synthesised using the liquid phase (41-MgO/ZnO-400, 55.1%), indicating that the MOF-based synthesis promoted the formation of active sites for catalysis. For 20-MgO@Zn-MOF-370, the total pore volume was 0.73 cm

3/g and the specific surface area was 1048.5 m

2/g. For 20MgO@ZnO-400, the total pore volume was 0.14 ± 0.04 cm

3/g, and the specific surface area was 32 ± 10.4 m

2/g. The FAME yields over three cycles for 20-MgO@Zn-MOF-370 (total basicity 0.77 mmol/g) were 68.4% for the second and 67.7% for the third, slightly higher than the first cycle (67.6%). The FAME yields over three cycles for 20-MgO@ZnO-400 (total basicity 1.20 mmol/g) were 70.3% for the second and 67.4% for the third, slightly lower than the first cycle (73.3%). Therefore, these hybrid nanostructures have a catalytic activity comparable to, or even higher than, that of other MgO-based catalysts under similar conditions [

98] (

Figure 10).

SrO exhibits limitations in catalysis due to its porous structure and low reusability. Therefore, MOFs are often used to support SrCO

3 and are calcined in an inert atmosphere to obtain the corresponding catalyst. Li et al. (2019) used MIL-Fe to support SrCO

3 (20 wt%). Then, they calcined in an inert atmosphere at 900 °C to obtain the new magnetic catalysts called ST-SrO and MM-SrO. MIL-Fe is composed of trimesate anions and Fe

3+ cations in these hybrid materials. The nature of iron(III) in MIL-Fe offers several advantages, including its low cost, low toxicity, and low environmental impact. The advantages of SrO and MIL-Fe were successfully employed in the catalysis of palm oil and methanol transesterification. To this end, in situ titration (ST-SrO) and mechanical mixing (MM-SrO) methods were used to compare their reusability with pure SrO. MM-SrO showed a maximum conversion of 96.19% at a methanol/palm oil molar ratio of 12:1, adding 8 wt% of catalyst at 65 °C in 30 min. For the third cycle, the conversion was 82.49%. The catalyst was easily separated from the reaction mixture by applying an external magnetic field. The results are due to the mesoporous structure of MM-SrO and its strong basicity (2.21 mmol/g), and it presents a surface area of 66.88 m

2/g, a pore volume of 0.14 cm

3/g, and an average pore diameter of 8.91 nm [

99].

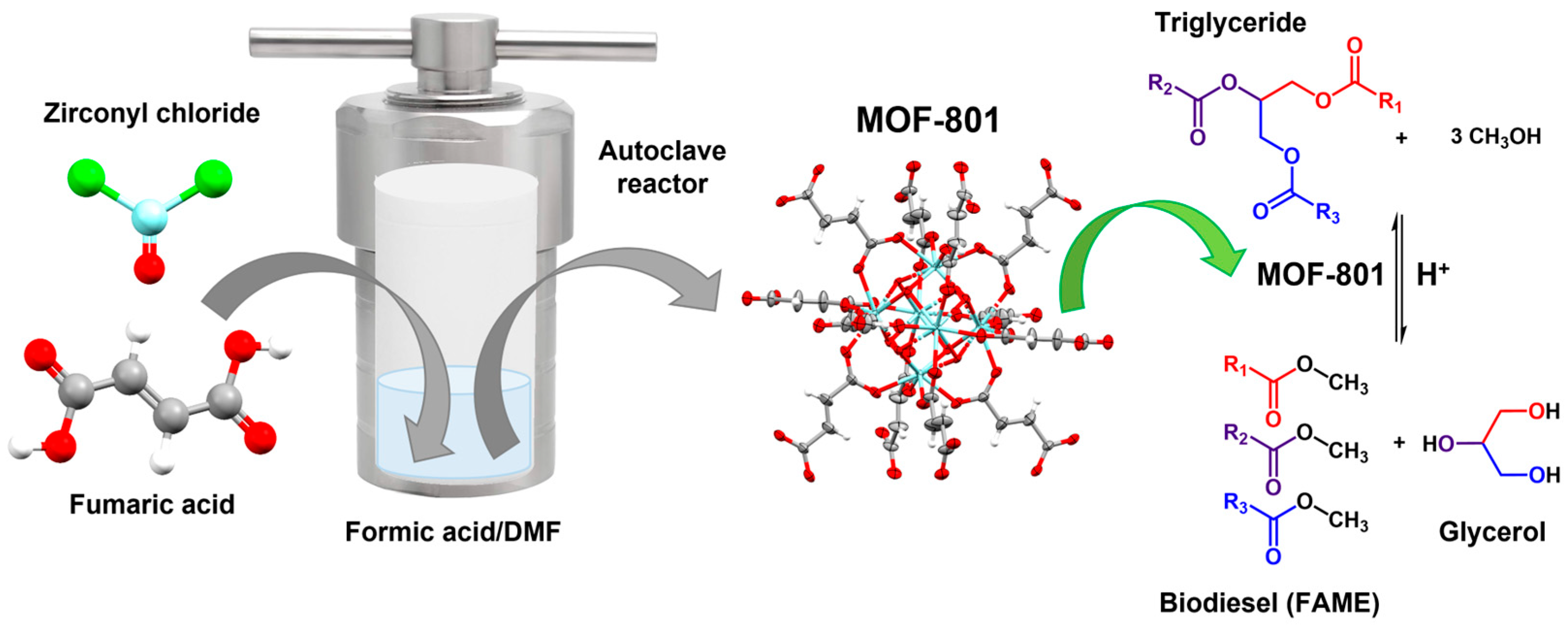

Several zirconium-based MOFs have been applied in various catalytic reactions, primarily UiO-66. However, there are some other MOFs whose catalytic potential has not yet been investigated, such as MOF-801, also known as Zr-fumarate MOF. This MOF features a microporous three-dimensional structure consisting of Zr

4+ cations connected by fumarate anions. Therefore, Shaik et al. (2022) applied MOF-801 as a heterogeneous catalyst in the transesterification of used vegetable oil (UVO) to obtain biodiesel. The authors analysed different reaction conditions, varying the methanol/oil molar ratio from 30:1 to 60:1, the catalyst loading from 5 to 20 wt%, the reaction time from 2 to 8 h and the temperature from 140 to 200 °C. This catalyst demonstrated moderate catalytic activity with a conversion of 59.8% using a catalyst loading of 10 wt% and a methanol/oil molar ratio of 50:1. The transesterification was carried out at 180 °C for 8 h and analysed by

1H NMR. Furthermore, MOF-801 exhibited adequate reusability, with a yield decrease of approximately 10% after three cycles. According to the authors, the catalyst’s activity can be attributed to the cationic (Zr

4+) and anionic (O

2−) sites, which are catalytically active in the crystal structure. Additionally, the Zr

4+ cations in MOF-801 facilitate electron transfer to O

2− anions, increasing their electron density. Therefore, these highly negative sites are susceptible to nucleophilic attack and function as Brønsted bases [

100] (

Figure 11).

Exploring recyclable solid-based catalysts for developing efficient processes remains a significant challenge. Micro- and mesoporous crystalline hybrid materials like MOFs have recently received considerable attention in heterogeneous catalysis. Chen et al. (2014) obtained amine-functionalized MOFs by post-synthetic dative modification of the metal sites on the secondary building units (SBUs) of MOF-5 and IRMOF-10. For this purpose, ethylenediamine (ED) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) were used, yielding MOF-5-ED, IRMOF-10-ED, MOF-5-DMAP, and IRMOF-10-DMAP. Additionally, covalent post-synthetic modification of the organic bonds of MIL-53(Al)–NH

2 with 2-dimethylaminoethyl hydrochloride was used to obtain MIL-53(Al)–NH–NMe

2. MOF-5, also known as IRMOF-1, and IRMOF-10 contain Zn

2+ ions connected by terephthalate and biphenyl-4,4′-dicarboxylate anions, respectively, while MIL-53(Al)-NH

2 contains Al

3+ ions connected by 2-aminoterephthalate anions. The authors reported the liquid-phase transesterification of glyceryl triacetate (1) and glyceryl tributyrate (2) at a methanol/triglyceride molar ratio of 29:1 using 30 mg of the aforementioned catalysts. For (1), the reaction mixture was heated at 50 °C for 3–4 h; for (2), the reaction mixture was heated at 60 °C for 6 h. GC performed product quantification, and MS was used to identify the product. MOF-5-ED, IRMOF-10-ED, and MIL-53(Al)–NH–NMe

2 showed conversions greater than 99% in model reactions with triglycerides, essential for biodiesel production. Furthermore, a linear relationship was reported between the catalytic activity and the basicity of the MOFs in transesterification. Therefore, catalysis under these conditions provides porous networks that allow the adsorption and diffusion of molecules such as triglycerides, and basicity that can be tuned through post-synthetic modification [

101].

Abdelmigeed et al. (2021) studied magnetised NaOH/ZIF-8 as a potential heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production using ethanol (ethanolysis). Using the coprecipitation technique, they synthesised magnetite nanoparticles (Fe

3O

4) from ferrous and ferric chlorides (FeCl

2/FeCl

3). ZIF-8, obtained from zinc(II) nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO

3)

2·6H

2O) and 2-methylimidazole, was added to the magnetite nanoparticles. The magnetised ZIF-8 was impregnated in a NaOH solution. This new catalyst was studied in the ethanolysis of vegetable oil (a mixture of refined sunflower and soybean oil) for biodiesel production. The ethanolysis conditions were optimised using a 2

n statistical design approach, reducing the number of experiments. This resulted in a conversion of 70% using a catalyst loading of 1 wt%, an ethanol/oil molar ratio of 21:1, a temperature of 75 °C, and a reaction time of 90 min. The ethanolysis fit the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, and the activation energy and pre-exponential Arrhenius constant revealed adequate kinetics. The physical properties of the biodiesel obtained were within ASTM ranges, while also revealing a higher cetane number. Upon reuse, the conversion decreased from 70% in the first cycle to approximately 50% in the second. The decrease in catalytic activity is due to catalyst leaching, despite magnetite nanoparticles facilitating their separation after the reaction [

102].

Recently, it was reported that magnetised NaOH/ZIF-8 catalysed the ethanolysis reaction for biodiesel production with a maximum conversion close to 70%. Furthermore, this catalyst substantially reduced its catalytic activity upon reuse due to NaOH leaching into the reaction mixture. Therefore, Abdelmigeed et al. (2021) evaluated magnetised NaOH/ZIF-8 in the methanolysis reaction by optimising the parameters to improve catalytic performance. The feedstock was mixed virgin vegetable oil containing sunflower and soybean oils in a 1:1 mass ratio. The chemical composition of the methyl esters obtained after transesterification was determined by GC. The authors used an RSM and a factorial design to determine the optimal methanol/oil ratio and catalyst loading for the oil conversion. In just 1 h at 65 °C and 600 rpm, the maximum conversion is close to 100% when the methanol/oil molar ratio is 21:1 and the catalyst loading is 3 wt% of the oil. The kinetic study demonstrated that the pseudo-second-order model fits the experimental methanolysis data. The Arrhenius equation showed a higher pre-exponential factor and lower activation energy for methanolysis than ethanolysis, revealing faster and more efficient kinetics. Finally, the esters produced under these conditions meet ASTM standards and could be used as sustainable fuels. Magnetised NaOH/ZIF-8 showed a 70% conversion in the second cycle of methanolysis. Calcination of NaOH/magnetised ZIF-8 at 200 °C in an inert atmosphere for 4 h showed a conversion close to 90% in the second cycle. Direct impregnation of NaOH onto ZIF-8 without magnetite loading showed a conversion close to 100% in both cycles. These two modifications reduced the leaching rate of NaOH from the catalyst during methanolysis, which improved its reusability [

103].

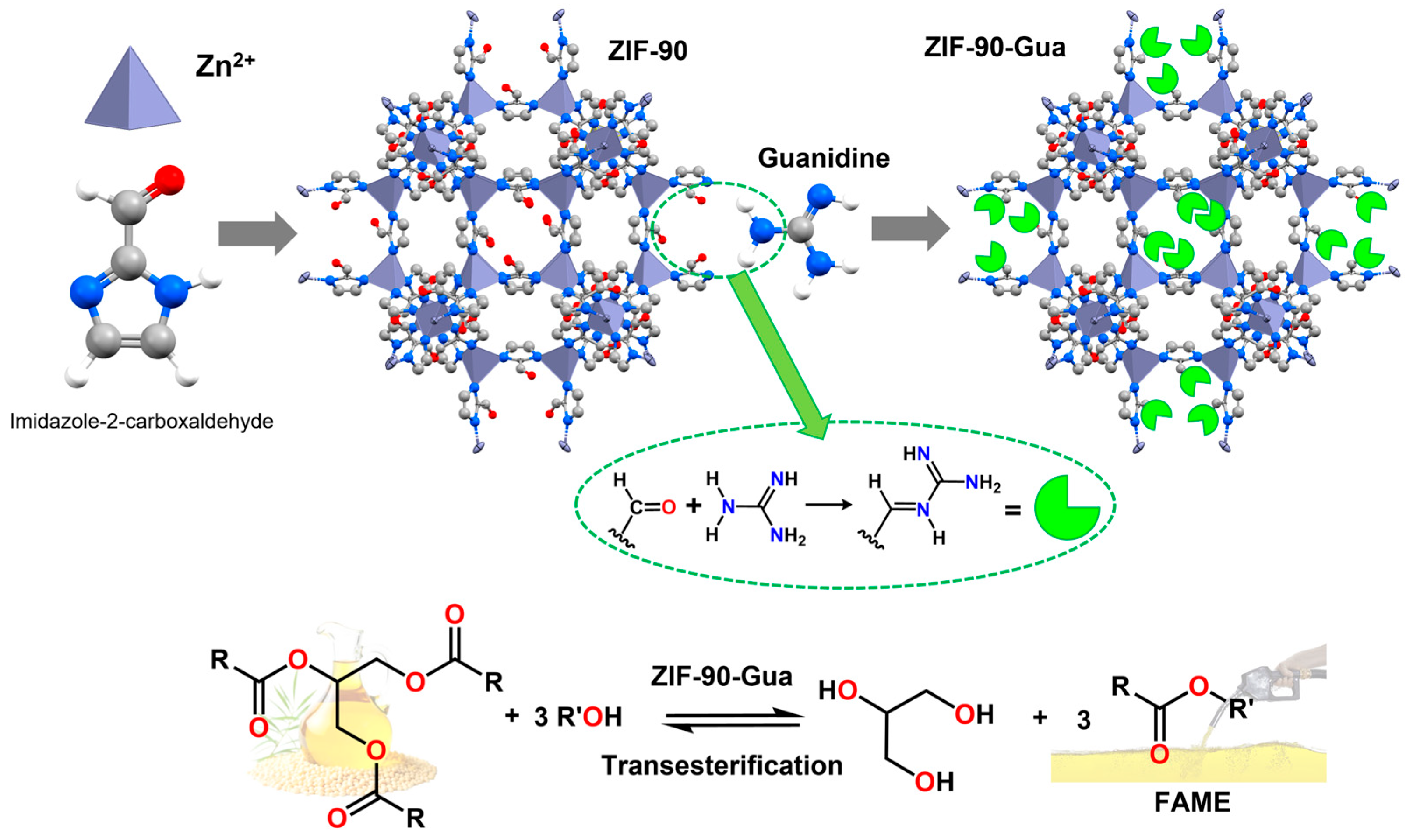

On the one hand, ZIF-90 is a MOF composed of tetrahedral Zn

2+ clusters coordinated with imidazole-2-carboxaldehyde ligands. The free aldehyde groups can be used as additional post-functionalization sites. On the other hand, guanidine is an organic base that can be easily anchored to ZIF-90. Both compounds form a novel hybrid solid catalyst (ZIF-90-Gua) via an imine condensation reaction. ZIF-90-Gua exhibited high surface basicity (1.56 mmol/g with an initial guanidine content of 24 mmol/g), resulting in competitive catalytic performances in heterogeneous transesterification for biodiesel production. Furthermore, ZIF-90-Gua exhibited strong covalent bonding between ZIF-90 and guanidine, resulting in a heterogeneous, efficient, and recyclable solid catalyst. This catalyst achieved a maximum soybean oil-to-biodiesel conversion of 95.4% at a reaction temperature of 65 °C after 6 h, with a ZIF-90-Gua loading of 1 wt% and a methanol/oil molar ratio of 15:1. GC determined oil conversion. The recovered catalyst was filtered, washed, and dried at 80 °C before reuse. Reuse tests showed that the conversion remained 82.6% after five cycles [

104] (

Figure 12).

MOF-based basic catalysis attempts to harness the activity of basic sites during transesterification while combating their inherent instability and intolerance to low-cost, high-FFA feedstocks. This section identifies three main design strategies: impregnation, intrinsic functionalization, and sacrificial precursor. These three strategies represent an evolutionary path in the design of heterogeneous materials. The most straightforward approach is to use a MOF (often magnetic or on a carbon support) as a sponge capable of supporting a conventional strong base. This technique achieves promising initial activity but suffers from leaching of the active component, which decreases its long-term stability. One solution is making the MOF the basic catalyst by covalently functionalizing the organic ligand with strong basic groups (such as amines or guanidine). By anchoring the active sites to the structure, the leaching problem is solved, resulting in much more stable catalysts. The most advanced strategy is to use the MOF as a sacrificial template, where the MOF is synthesised and then pyrolysed, creating a second-generation material (a nanostructured mixed oxide or doped carbon) that inherits the atomic dispersion and high surface area of the precursor, but with superior chemical and thermal stability. This is the most promising route to creating catalysts at the industrial level. Despite the growing development in basic catalyst design, none of the articles analysed successfully solve the problem of catalysis in the presence of high levels of FFA (

Table 1).

4.2. Biodiesel Production Catalysed by Acid Catalysts

MOF-based acidic catalysts are porous and versatile materials with metal centres in their structure that act as Lewis acids, as they can accept the electron density of the reactive molecules, thus facilitating the reaction. The MOF structure can host and disperse these active sites homogeneously, which is essential for heterogeneous catalysis. These materials offer tuneable porosity and a large surface area, improving active site distribution and catalytic efficiency in transesterification/esterification.

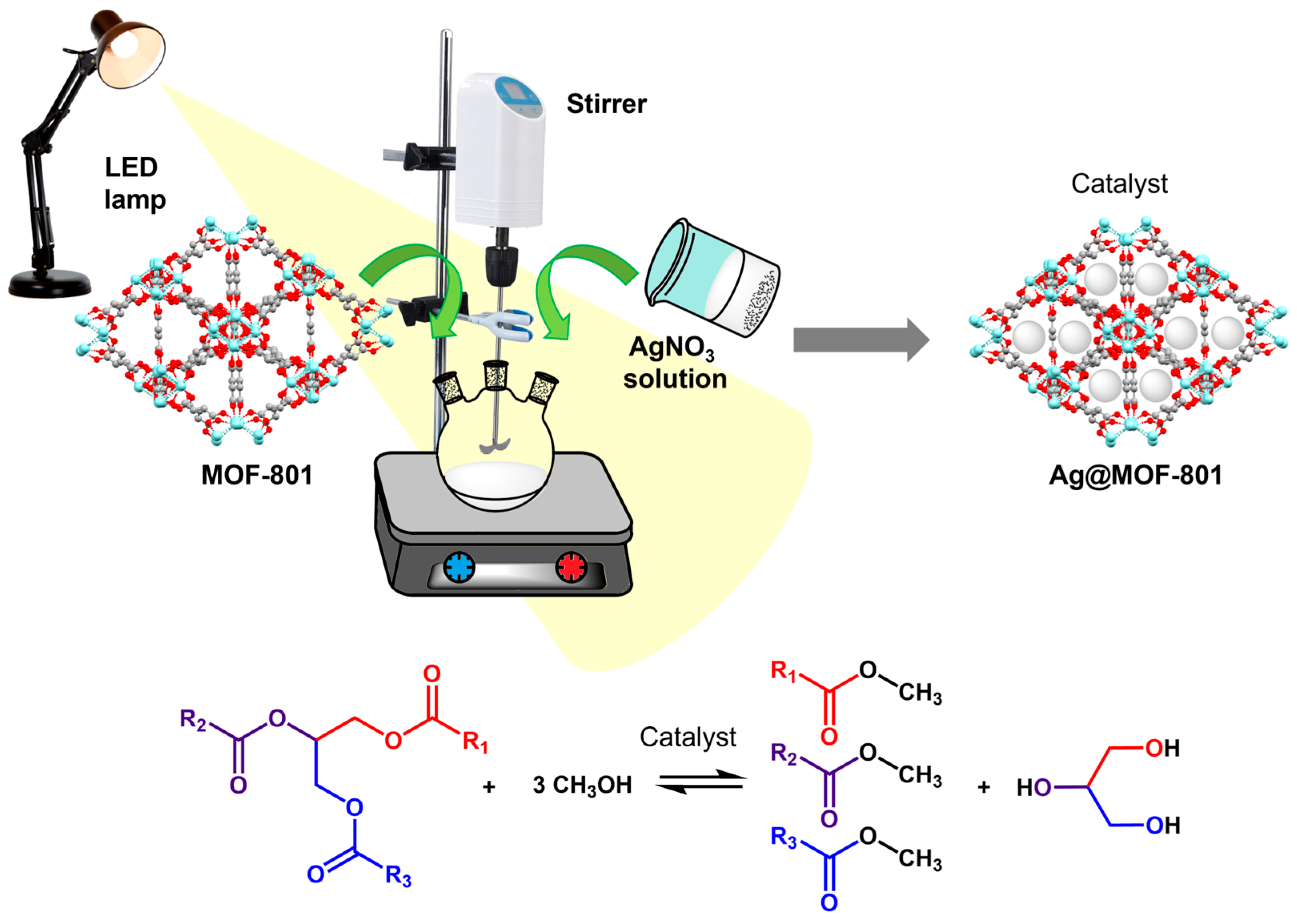

Alduhaish et al. (2022) synthesised a hybrid material based on silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and MOF-801. This MOF, containing Zr

4+ cations linked by fumarate anions, formed a hybrid material with AgNPs through a photocatalytic method. In this process, the photocatalytic properties of zirconium facilitated the formation and deposition of AgNPs on the MOF surface by visible light irradiation. Ag@MOF-801 was successfully used as a heterogeneous catalyst in UVO transesterification, and according to the authors, its performance is due to the synergistic interaction between its components. The experimental conditions used in the transesterification reaction were a methanol/oil ratio of 50 wt%. They varied the catalyst ratio from 5 to 20 wt% (0.075–0.300 g) relative to the oil weight, a reaction temperature from 140 to 200 °C, and a reaction time from 2 to 8 h. A maximum conversion of 70.1% was obtained, calculated by

1H-NMR, under the conditions of 10 wt% catalyst, 8 h of reaction, and at a temperature of 180 °C. In addition, reusability tests were performed, which showed an 8% reduction after three reaction cycles. It is worth mentioning that the authors performed the same experiment with pristine MOF-801, obtaining a maximum conversion of 60% with the same amount of catalyst, indicating that the presence of AgNPs increases catalytic activity, which was attributed to the increased surface area of the hybrid material. Additionally, with the addition of HCl (10%

v/

v), the yield increased to 73.1%, which could be due to the inherent catalytic activity of HCl in the transesterification [

105] (

Figure 13).

Due to the need for cleaner and greener alternatives, Xie et al. (2019) synthesised a reusable hybrid organic-inorganic catalyst for one-step biodiesel production from low-cost feedstocks. UiO-66-2COOH is an MOF based on ZrCl

4 and 1,2,4,5-tetrabenzene carboxylic acid (H

4BTEC). This MOF was modified with three keggin-type polyoxometalate (POM) acids: 12-tungstophosphoric acid (HPW), silicotungstic acid (HSiW), and phosphomolybdic acid (HPMo) functionalized with [SO

3H-(CH

2)

3-HIM][HSO

4]. The latter compound is a sulfonated acidic ionic liquid (AIL) made of imidazole, 1,3-propanesultone, and H

2SO

4. These AILs/POM/UiO-66-2COOH catalysts combine the advantages of Lewis and Brønsted acids with the heterogeneous microenvironment of MOFs. GC determined the catalyst performance comparison in the soybean oil transesterification process. The esterification experimental conditions evaluated were a methanol/oil molar ratio of 20:1–45:1, a catalyst loading of 4–12 wt%, a reaction temperature of 80–130 °C, and a reaction time of 2–10 h with stirring at 750 rpm. The AILs/HPW/UiO-66-2COOH catalyst showed the best catalytic performance, achieving a conversion of 95.8% at a methanol/oil molar ratio of 35:1, a catalyst loading of 10 wt%, and a reaction temperature of 110 °C in 6 h. This solid catalyst has a high surface area (8.63 m

2/g) and acidity, allowing for simultaneous transesterification and esterification reactions. The catalyst could be reused five times with a slight catalytic loss, showing approximately 80% residual activity [

106] (

Figure 14).

Peña-Rodríguez et al. (2018) obtained a heterogeneous catalyst based on a cobalt(II) MOF, which was synthesised by hydrothermal reaction of Co(NO

3)

2·6H

2O, 1,2-di-(4-pyridyl)-ethylene, and 5-nitroisophthalic acid. The hydrothermal synthesis of the Co-MOF was carried out in H

2O, heating at 160 °C for 72 h. The transesterification reaction was carried out in a glass tube with a Teflon stopper, adding 1 g of oil, 10 mL of methanol, and 25 mg of catalyst. Subsequently, to improve the interaction between oil, methanol, and the catalyst, the reaction was ultrasonicated for 12 h at 60 °C. At the end of the reaction, a conversion of 80% was achieved. In addition, five methyl esters were identified and quantified by GC: methyl stearate 37.24%, methyl linoleate 21.30%, methyl palmitate 15.24%, methyl oleate 4.76% and methyl arachidate 0.98%, so this new catalyst efficiently allowed the production of biodiesel from

Erythrina mexicana oil [

107].

Jafari et al. (2024) fabricated an efficient and novel MOF by hydrothermal synthesis using Cr(NO

3)

3∙9H

2O and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) as the organic ligand. They dissolved 0.5 mmol of EDTA in 1 mL of H

2O for synthesis. Subsequently, they added 1 mmol of the chromium(III) salt dissolved in 7.5 mL of DMF and maintained stirring at 70 °C and a pH of 9 for 25 min. Consequently, they transferred the reaction mixture to an autoclave and kept it at 160 °C for 24 min. This catalyst, called Cr-EDTA-MOF, was successfully used for the esterification of oleic acid and palmitic acid. To this end, in each experiment, they varied the methanol/oil molar ratio from 4:1 to 15:1, the amount of NaOH from 0.03 to 0.09 g, and the reaction temperature from 35 to 60 °C, maintaining the reaction time at 5 h. The products obtained were analysed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC), FT-IR,

13C and

1H NMR. The best yields obtained were 91% for oleic acid and 94% for palmitic acid, both under the same reaction conditions: 0.05 g of catalyst, 0.07 g of NaOH, a temperature of 60 °C, a methanol/oil molar ratio of 11:1, and a reaction time of 5 h. Recycling tests yielded 91% in the first cycle and 89% in the fourth (oleic acid). The resulting Cr-EDTA-MOF is considered a Brønsted-Lewis acid catalyst, as it demonstrated a potent and efficient capacity for the esterification of oleic and palmitic acids under near-ideal conditions. Furthermore, it performed well with a low catalyst dosage, easy centrifugal separation, adequate stability, and a simple synthesis methodology [

108] (

Figure 15).

Traditional homogeneous catalysts are nonbiodegradable and challenging to separate, which affects profitability and creates environmental problems due to waste generation. Therefore, Javed et al. (2023) designed a new heterogeneous catalyst based on a biomaterial-modified MOF named Bio-MOF. This MOF is composed of Zn(OAc)

2, 1,1′-biphenyl-2,2′,5,5′-tetracarboxylic acid, and adenine. It was also complexed with an IL called [HMIM][HSO

4]. 1-Methylimidazole hydrogen sulphate ([HMIM][HSO

4]) was prepared from 1-methylimidazole and H

2SO

4. The hybrid material named [HMIM][HSO

4]/Bio-MOF was obtained by the wet impregnation method with 50% loading of [HMIM][HSO

4] slowly added onto the Bio-MOF. The Bio-MOF provides more active sites, and [HMIM][HSO

4] provides greater reactivity. A kinetic analysis was performed, which suggests that biodiesel production occurs at the vapour/liquid interface of the microalgae oil. The authors evaluated biodiesel production by varying the methanol/oil molar ratio from 5:1 to 20:1, catalyst loading from 0.25 to 1.00 wt%, reaction time from 5 to 50 min, and temperature from 70 to 100 °C. The best conversion obtained was 92 ± 4% at a methanol/oil molar ratio of 15:1, catalyst loading of 0.5 wt%, and a temperature of 70 °C reached in 30 min. The catalyst was reused four times, maintaining 82% conversion, and on the seventh, the conversion dropped to 63%. The study demonstrates that [HMIM][HSO

4]/Bio-MOF increases biodiesel conversion as measured by GC by integrating mass transfer mediated by microbubbling technology. Therefore, the increased reactivity, surface area, rate, and conversion are attributed to the excess methanol at the interface and the simultaneous water removal from the reactor [

109].

Hao et al. (2023) synthesised a heterogeneous catalyst named ILe@Cu@MOF from CuSO

4∙5H

2O, terephthalic acid and

L-isoleucine (ILe). The latter component improved the processability and optimisation of transesterification for biodiesel production from

Xanthoceras sorbifolium Bunge oil. The parameters used for biodiesel production were 10 g of oil, with a catalyst weight ranging from 1 to 5 wt%, a methanol/oil ratio from 15:1 to 35:1, a reaction temperature from 50 to 90 °C and a reaction time from 1 to 5 h. The best conditions for biodiesel production led to a yield of 82.85%, with a catalyst content of 3 wt%, a methanol/oil molar ratio of 35:1, a reaction temperature of 50 °C, and a reaction time of 4 h. Catalyst recycling tests showed that a catalytic activity of 73.40% could be maintained after five cycles. The transformation of the

Xanthoceras sorbifolium Bunge oil was confirmed by GC-MS,

13C and

1H NMR, reporting the presence of methyl oleate (45.41%), linoleic acid (38.64%), methyl palmeate (4.65%), methyl erucate (4.17%), and methyl stearate (2.21%). SEM micrographs showed that the Cu@MOF surface adhered to a layered ILe structure, confirming successful functionalization. Furthermore, they determined a specific surface area of 19.687 m

2/g with an average pore size of 31.74 nm [

110].

Liu et al. (2020) designed a stable and economical sulfonated catalyst called MF–SO

3H, based on MIL-100(Fe) functionalized with the sulfonic acid group. MIL-100(Fe) was obtained from Fe(NO

3)

3·9H

2O and trimesic acid, and MF–SO

3H was obtained from MIL-100(Fe) and dilute H

2SO

4. The optimal parameters of H

2SO

4 concentration (0.9 mol/L), H

2SO

4 volume (25 mL), sulphonation temperature (160 °C), and sulphonation time on catalyst preparation (10 h) were investigated. On the other hand, the esterification of methanol and oleic acid was analysed by varying the methanol/oleic acid ratio from 4:1 to 12:1 wt%, the reaction temperature from 50 to 90 °C, and the catalyst loading from 4 to 12 wt%. In addition, they determined the reaction time with the effect of sulphonation on temperature, and determined that the highest catalytic activity was obtained at 2 h. The maximum conversion of 95.86% was achieved with a methanol/oleic acid molar ratio of 10:1, a catalyst amount of 8 wt%, and a temperature of 70 °C for 2 h. The catalyst was reused seven times; up to the fifth cycle, it maintained a yield of 88.50%. In the sixth, it dropped to 75.83%. In the last, it reached 58.34%. Therefore, it is considered that there was a considerable loss of activity, but not significant, until the fifth cycle. MF-SO

3H maintains the structure of the initial MOF after successful anchoring of the –SO

3H group and has a high content of Brønsted and Lewis acidic sites, recorded at 70 °C [

111].

Recently, chemical synthesis has used microwave irradiation as an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional heating. In this regard, AbdelSalam et al. (2020) synthesised a magnesium(II) MOF from Mg(NO

3)

2∙6H

2O and terephthalic sites using microwave irradiation (Mg-MOF or Mg

3(bdc)

3(H

2O)

2). This same radiation produced biodiesel from oleic acid and methanol esterification. The conversion of oleic acid to methyl oleate was quantified by titration. The authors tested various reaction conditions, including reaction times of 1–10 min, a methanol/oleic acid molar ratio of 1:5–1:25 wt%, a catalyst loading of 0.05–0.20 wt%, and a power of 100–200 watts at a temperature of 65 °C. The optimal conditions under which they obtained a 97% yield were a methanol/oleic acid ratio of 15:1, a reaction time of 8 min, a microwave power of 150 watts, and a catalyst loading of 0.15 wt%. Switching from microwave irradiation to conventional heating (3 h, 70 °C) led to an 83% conversion. The remaining catalytic activity was analysed over five cycles, with a reduction from 97% to 92% in the fifth cycle. The vacant sites, metal clusters, pore size (mesopores), and surface area (162 m

2/g) of the Mg

3(bdc)

3(H

2O)

2 nanosheets are responsible for their catalytic activity. The acidic nature of Mg

3(bdc)

3(H

2O)

2 derives from the vacant sites created by the removal of solvent molecules (Lewis acid) and from the metal clusters, which are another source of intrinsic acidity (Brønsted acid) [

112].

Recently, some scientists have sought new heterogeneous catalysts capable of producing biodiesel efficiently, significantly, and ecologically sustainably. Therefore, Putro et al. (2024) synthesised MIL-53(Al) by hydrothermal synthesis from Al(NO

3)

3·9H

2O and terephthalic acid. This pristine MOF generated biodiesel from waste cooking oil (WCO). MIL-53(Al) has a surface area of 645 ± 1.54 m

2/g, an average pore size of 44 ± 0.24 nm, and an average pore volume of 148 ± 0.47 cm

3. The transesterification and esterification processes were carried out using subcritical conditions. To achieve optimal conditions, the authors designed a study incorporating three independent variables using multilevel factorial design, RSM, CCD, and a three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). To do this, they varied the temperature from 83 to 167 °C, the time from 3.2 to 36.8 min and the methanol/WCO molar ratio from 13.7:1 to 84.3:1. In this study, a catalyst concentration of 3 wt% and a pressure of 45 bar were used, focusing on an economically and technologically viable process. Statistical analysis indicated that FAME conversion reached a maximum of 91.96% at a temperature of 150 °C, a time of 30 min, and a molar ratio of 28:1. Under experimental conditions, FAME conversion reached a maximum of 92.34% with a catalyst loading of 3 wt%. Therefore, the statistical and experimental reciprocity correlates the calculated and actual catalyst performance. GC indicated that the FAMEs obtained had a purity of 96.9%, meeting the ASTM D6751 standard. After four cycles, the catalyst reduced its catalytic capacity to 72%. Temperature-programmed desorption of NH

3 (NH

3-TPD) demonstrated that the catalyst exhibits weak acidic properties due to Brønsted acidic sites. Furthermore, FT-IR suggests a small amount of unreacted terephthalic acid confined within the MIL-53(Al) cavities [

113].

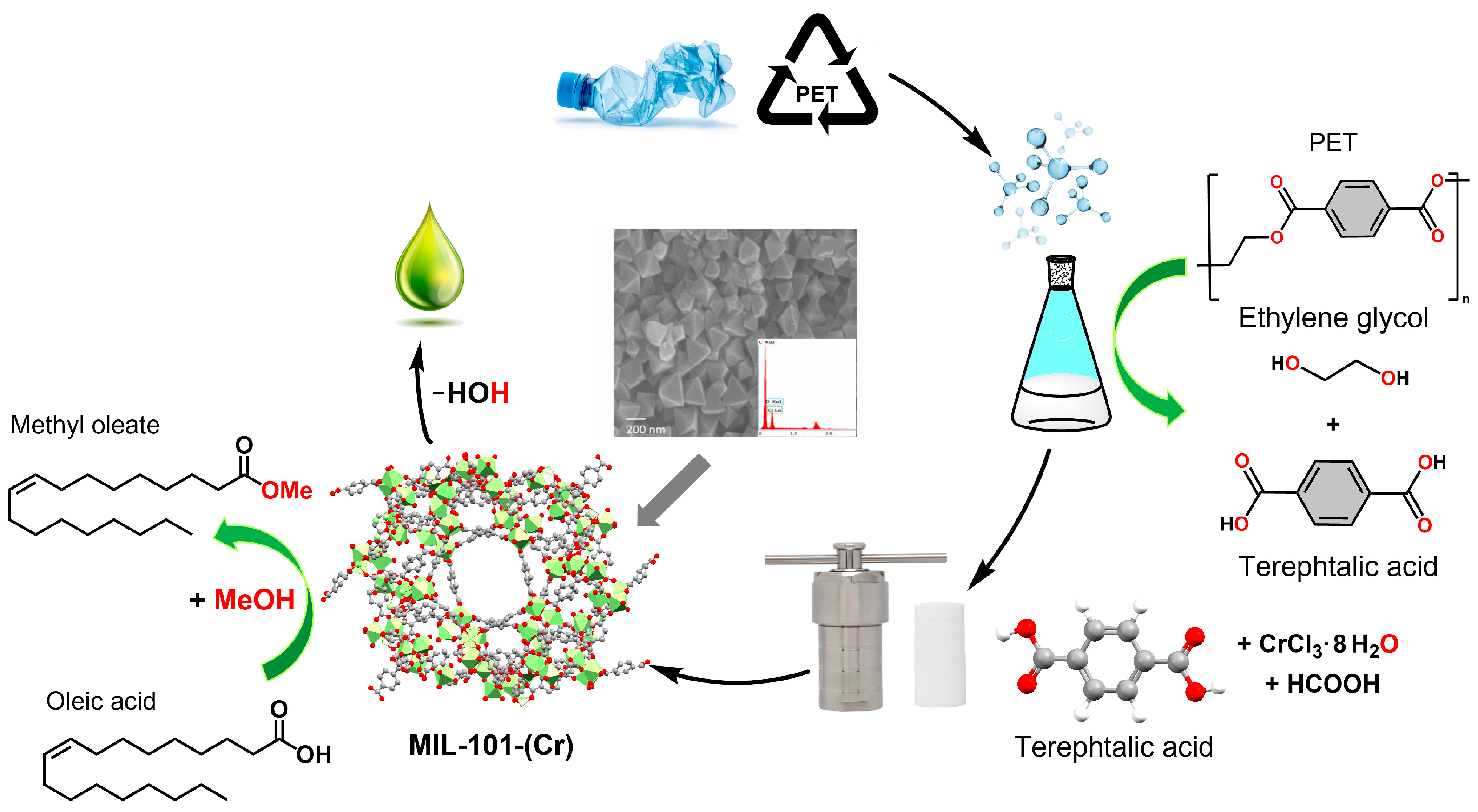

Recently, several studies have focused on reusing terephthalic acid in polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles, reducing waste generation and environmental problems. In this context, Abou-Elyazed et al. (2024) used CrCl

3·6H

2O and recovered and commercial terephthalic acid for the synthesis of MIL-101(Cr)

PET-recovered and MIL-101(Cr)

PET-commercial, respectively. These two heterogeneous catalysts were used in the esterification of oleic acid with methanol to produce biodiesel (methyl oleate). The authors used different reaction conditions, such as stirring at 1000 rpm, a methanol/oleic acid molar ratio of 8:1 to 39:1, a catalyst loading of 2 to 10 wt%, a reaction temperature of 25 to 65 °C, and a reaction time of 1 to 6 h. The highest biodiesel yields were achieved at a molar ratio of 39:1, a catalyst loading of 6 wt%, a reaction time of 4 h, and a reaction temperature of 65 °C. 80% and 86.9% yields were obtained for MIL-101(Cr)

PET-recovered and MIL-101(Cr)

PET-commercial, respectively. According to the authors, in reuse experiments, catalytic efficiency (>70%) is maintained after three cycles for MIL-101(Cr)

PET-recovered and after five cycles for MIL-101(Cr)

PET-commercial. MIL-101(Cr)

PET-recovered has a surface area of 1673 m

2/g and a pore volume of 1.03 cm

3/g, while MIL-101(Cr)

PET-commercial has a surface area of 2618 m

2/g and a pore volume of 1.42 cm

3/g. NH

3-TPD analysis indicated that both catalysts have two types of acid sites: medium acidic sites associated with Cr-OH

2 and Cr-OH centres (Brønsted acidic sites), and strong acidic sites, related to unsaturated chromium metal nodes (Lewis acidic sites) [

114] (

Figure 16).

Han et al. (2018) synthesised a novel heterogeneous catalyst based on MIL-101(Cr) (Cr(NO

3)

3·6H

2O and terephthalic acid) functionalized with ILs called MBIAILs or [SO

3H-(CH

2)

3-HMBI] [HSO

3] (2-mercaptobenzimidazole, 1,3-propanesultone, and H

2SO

4). The results obtained show that the post-synthetic modification was successfully carried out by immobilising MBIAILs on the surface of MIL-101(Cr) via the dative S–Cr bonds. The catalytic activity of MIL-101(Cr)@MBIAILs were evaluated by oleic acid esterification. Tests were conducted under different reaction conditions, for example, methanol/oleic acid molar ratios ranged from 2:1 to 12:1, catalyst loading ranged from 0.5 to 18 wt%, reaction temperature ranged from 38 to 97 °C, and reaction time ranged from 0.5 to 6 h. GC determined oleic acid conversion. The best experimental conditions showed a maximum conversion of 91.0% when the molar ratio was 10:1, catalyst loading was 11 wt%, reaction time was 4 h, and reaction temperature was 67 °C. This conversion was reduced to 82.1% after six reuse cycles, demonstrating that this catalyst has superior catalytic performance, excellent reusability, and stability [

115].

Ben-Youssef et al. (2021) first used MOF-5, based on Zn(NO

3)

2∙6H

2O and terephthalic acid, as a heterogeneous acid catalyst in the simultaneous transesterification/esterification of WVO (Waste Vegetable Oil) and

Jatropha curcas oil. Two non-edible vegetable oils with high FFA content. They designed experiments using a CCD and an RSM to obtain the optimal experimental conditions. The mathematically evaluated conditions were a methanol/oil molar ratio of 3:1 to 45:1, a reaction time of 1 to 15 h, a reaction temperature of 118 to 152 °C, and a catalyst loading of 0.1 to 0.9 wt%. The optimal experimental conditions were a methanol/oil molar ratio of 36:1, a reaction temperature of 145 °C, and a catalyst loading of 0.75 wt%. For WCO, they obtained a maximum biodiesel yield of 90.8% with a 93.3% decrease in FFA as measured by

1H NMR.

Jatropha curcas oil obtained a maximum biodiesel yield of 88.3% with a 94.8% decrease in FFA as measured by

1H NMR. The reaction time for WCO was 12 h, and for

Jatropha curcas oil, it was 9.59 h. The biodiesel produced meets the ASTM D6751 quality standard. Under optimal conditions, the catalyst could only be reused with WVO once, reaching a catalytic yield of 82% in the first cycle, and 41.2% in the second cycle. One-step esterification/transesterification offers technical and economic advantages during biodiesel production [

116].

One strategy for converting microalgal lipids into biodiesel is using catalysts with hierarchical porous structures and many defects that create active sites. For this reason, Qian et al. (2023) improved the coordination of trimesic acid with ZrOCl

2⋅8H

2O by modulating the basicity of

N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) with formic acid (HCOOH). This approach created functional defects in MOF-808-R by varying the DMF/HCOOH ratio (R = 3/1, 2/1, 1/1, 1/2, and 1/3). These defects increased the pore diameter, pore volume, specific surface area, and acidity of the MOF-808-R. The catalytic performance of MOF-808-R was evaluated using a methanol/algal oil ratio of 20:1, a catalyst loading of 3 wt%, and a reaction temperature of 180 °C. Catalysts with R = 1/1, 2/1, and 3/1 showed catalytic efficiency of 87.89%, 90.24%, and 92.60%, respectively, while the others were inefficient for catalytic conversion. Therefore, variations in experimental conditions were evaluated for MOF-808-3/1, such as catalyst concentrations of 1–7 wt%, reaction temperatures of 60–200 °C, and reaction times of 0.5–3 h, while maintaining a methanol/algal oil ratio of 20:1. Finally, a catalytic yield of 96.24% was obtained with a catalyst concentration of 2 wt%, a reaction temperature of 200 °C, and a reaction time of 1 h. Catalytic efficiency decreased slightly to 93.78% after six cycles [

117] (

Figure 17).

Molybdenum catalysts are widely recognised for this metal’s ability to exist on solid surfaces in different oxidation states. Therefore, Ghorbani-Choghamarani et al. (2022) synthesised a molybdenum(VI)-based MOF from Na

2MoO

4 and 4-piperidinecarboxylic acid using a solvothermal method. The Mo-MOF was used as a catalyst in the esterification reaction to produce biodiesel from palmitic acid and oleic acid. This catalyst demonstrated thermal stability above 300 °C and a surface area of 56 m

2/g. The experiment used 1 mol of oil and 60–300 mg of Mo-MOF using a methanol/oil ratio of 3:1 to 15:1 and a reaction temperature of 25–60 °C. The optimal conditions were 300 mg of catalyst, a methanol/oil ratio of 13:1, a temperature of 60 °C and a time of 4 h. The authors obtained a maximum conversion yield of 95% for oleic acid and 90% for palmitic acid. The same yields were obtained when the methanol/oil molar ratio was 15:1. The Mo-MOF could be easily recovered by centrifugation and reused up to four times, showing a slight decrease while retaining 92% (oleic acid) of its catalytic activity. The biodiesel obtained by this method meets ASTM standards [

118].

Dai et al. (2021) synthesised a Brønsted acid ionic liquid (PSH, [HSO

3-pmin]

+[HSO

4]

−) from 1,3-propylsultone, 1-methylimidazole, and H

2SO

4. PSH was loaded onto three zirconium(IV)-based MOFs (UiO-66, UiO-66-NO

2, and UiO-66-NH

2) using the impregnation method. The three new hybrid materials (PSH/UiO-66, PSH/UiO-66-NO

2, and PSH/UiO-66-NH

2) were used as heterogeneous catalysts for biodiesel production from Jatropha oil. To this end, a preliminary test was conducted using a methanol/Jatropha oil ratio of 30:1, a catalyst dosage of 3 wt%, a reaction temperature of 70 °C, and a reaction time of 5 h. Under these conditions, PSH/UiO-66, PSH/UiO-66-NO

2, and PSH/UiO-66-NH

2 achieved conversion rates of 66.21%, 96.69%, and 77.02%, respectively. PSH/UiO-66-NO2 achieved the highest conversion rate, so the optimal reaction conditions were investigated using an orthogonal test. The optimal conditions were a methanol/Jatropha oil ratio of 25:1, a catalyst dosage of 4 wt%, a reaction temperature of 70 °C, and a reaction time of 4 h. Thus, under optimal conditions, PSH/UiO-66-NO

2 achieved a conversion rate of 97.57%. PSH/UiO-66-NO

2 exhibits a surface area of 11.53 m

2/g, a pore volume of 0.0094 cm

3/g, and an average pore diameter of 10.06 nm, favouring transesterification. Reusing the catalyst under optimal conditions showed that in the third cycle, the conversion rate decreased to 77.14% [

119].

Using heterogeneous solid catalysts for obtaining biodiesel from oils and fats represents a viable and sustainable strategy. Among the most promising catalytic supports, MOFs stand out for their aforementioned characteristics. Along these lines, using an impregnation technique, Kalita et al. (2024) synthesised a novel nanocomposite called UiO-66@HAp. This hybrid material consists of hydroxyapatite (HAp = Ca

10(PO

4)

6(OH)

2) supported on UiO-66 (a MOF of cationic Zr

4+ and anionic terephthalate). The catalytic activity of UiO-66@HAp was evaluated in the transesterification of palm oil for biodiesel production.

1H and

13C NMR, FTIR, and GC-MS confirmed the formation of FAME. The reaction conditions evaluated were a methanol/palm oil molar ratio of 3:1 to 12:1, catalyst loading of 2 to 8 wt%, reaction temperatures of 60 to 100 °C, and reaction time of 0.5 h to 1.5 h. The transesterification conditions that allowed a maximum yield of 97% were a 6:1 molar ratio, a catalyst loading of 6 wt%, a temperature of 70 °C, and a time of 1 h. Furthermore, UiO-66@HAp had a surface area of 83.78 m

2/g, a pore size of 0.068 cm

3/g, and a pore diameter of 38.36 nm. The catalyst showed high stability and reusability after five cycles; in the third cycle, it remained above 90% and in the fifth, above 85%, with minimal deactivation. UiO-66@HAp acts as an acid catalyst; the presence of Ca

2+ in HAp converts it into a Lewis acid, increasing the intrinsic acidity of UiO-66 [

120].

The conversion of oils with high FFA content into biodiesel under mild conditions remains a challenge, making the development of highly efficient heterogeneous acid catalysts key. Therefore, Li et al. (2024) used 2,5-dimercaptoterephthalic acid as the organic ligand (instead of terephthalic acid) in the synthesis of UiO-66-(SH)

2, preserving its original structure (UiO-66-(Zr)). The sulfhydryl catalyst UiO-66-(SH)

2 was oxidised in situ with H

2O

2 and acidified with H

2SO

4, thus generating the sulfonic catalyst UiO-66-(SO

3H)

2. This modification increased the number of acidic sites, raising the total acidity from 0.02 mmol/g to 2.28 mmol/g, improving catalytic efficiency. The surface area of the UiO-66-(SO

3H)

2 catalyst was 32.18 m

2/g, the pore volume was 0.15 cm

3/g, and the average pore size was 10.53 nm. Various esterification conditions were tested, including a methanol/oleic acid ratio of 5:1 to 25:1, catalyst loading of 5 to 15 wt%, reaction temperature of 60 to 100 °C, and reaction time of 2 to 6 h. Under optimal conditions (methanol/oleic acid molar ratio of 15:1, catalyst loading of 10 wt%, reaction temperature of 90 °C, and reaction time of 4 h), a maximum conversion of 86.21% was achieved in the esterification of oleic acid to biodiesel. Comparatively, UiO-66-(SH)

2 achieved a catalytic conversion of 65.25% with a methanol/oleic acid molar ratio of 10% by weight, a catalyst loading of 8% by weight, at 70 °C for 4 h. The catalyst demonstrated high stability, water resistance (up to 10 wt%), and excellent reusability, with a conversion decrease of only 3.54% after four consecutive cycles. The resulting biodiesel complies with the EN 14214 standard, making it suitable as a transport fuel [

121] (

Figure 18).

Lunardi et al. (2021) solvothermally synthesised Zn

3(BTC)

2 from ZnSO

4 7H

2O and trimesic acid to catalyse the production of FAME or biodiesel. This study used degummed palm oil (DPO) and methanol’s one-step esterification and transesterification reaction. Zn

3(BTC)

2 exhibits a specific surface area of 1175.81 m

2/g, a pore volume of 0.81 cm

3/g, and thermal stability up to 300 °C. Furthermore, it shows a hierarchical macro/microporous architecture that simplifies the transport of reactive molecules to the Lewis acid (Zn

2+) metal sites responsible for catalytic activity and product desorption. The optimal conditions to maximise conversion efficiency were determined using an RSM via the Box–Behnken design (BBD), evaluating the following parameters: a methanol/DPO molar ratio of 4:1 to 8:1, a catalyst loading of 0.5 to 5 wt%, a reaction temperature of 45 to 65 °C, and a reaction time of 1.5 to 4.5 h. The optimal conditions identified were a 6:1 molar ratio, a temperature of 65 °C, a time of 4.5 h, and a catalyst loading of 1 wt%, thus achieving a maximum biodiesel yield of 89.89%, which is consistent with the quadratic polynomial model’s prediction of 89.96%. Biodiesel and FAME yields were determined using GC with a flame ionisation detector (FID). Finally, Zn

3(BTC)

2 was evaluated under optimal conditions during five reaction cycles. The catalytic conversion was maintained between 85 and 90% in the first three cycles, 80% in the fourth cycle, and 75% in the fifth. The resulting biodiesel met international quality specifications ASTM 6751 and SNI 7182-2015 [

122].

We have seen that biodiesel can be obtained from oleic acid through the esterification reaction using heterogeneous MOF-based catalysts. Along these lines, Zulys et al. (2024) studied two monometallic MOFs (La-BTC and Zr-BTC) and one bimetallic MOF (Zr/La-BTC) using ZrCl

4, La(NO

3)

3·6H

2O, and trimesic acid. The surface areas of Zr-BTC, La-BTC, and Zr/La-BTC are 12.328 m

2/g, 167.101 m

2/g, and 4.764 m

2/g. Zr/La-BTC converted 78.11% under the following conditions: a methanol/oleic acid molar ratio of 60:1, a catalyst loading of 5 wt%, a reaction temperature of 65 °C, and a reaction time of 4 h. The presence of methyl oleate, methyl palmitate, oleic acid, and palmitic acid in the biodiesel was confirmed by GC-MS. Zr/La-BTC showed higher catalytic activity (72.42%) compared to Zr-BTC (62.74%) and La-BTC (60.42%) under the following parameters: 60:1, 1 wt%, 65 °C, and 4 h. Their Lewis acidity determines the catalytic efficiency of the three MOFs. Zr

4+ is more acidic than La

3+. Therefore, the conversion percentage of Zr-BTC was higher than that of La-BTC. MOFs, particularly ZIFs, represent an area of opportunity in the search for potential heterogeneous catalysts in biodiesel production [

123].

Oghabi et al. (2023) synthesised a ZIF-8-based nanocatalyst obtained solvothermally from Zn(NO

3)

2·6H

2O, 2-methylimidazole, and ammonia. It was subsequently modified by a sulfation process using Na

2SO

4, obtaining the nanocatalyst called 4S. The authors evaluated the performance of 4S in the esterification reaction of FFAs under different reaction conditions. To do this, they used a mixture of oleic (66%), palmitic (16%), and linoleic (15%) acids to carry out the esterification, evaluating a methanol/FFA ratio from 10:1 to 40:1, a catalyst loading from 1 to 7 wt%, a reaction temperature from 100 to 190 °C, and a reaction time from 4 to 10 h. The optimal transesterification conditions led to a 97% FFA conversion and included a methanol/acid mixture ratio of 10:1, a catalyst loading of 3 wt%, a temperature of 160 °C, and a reaction time of 6 h. 4S showed a good surface area (995.6 m

2/g), good acidity, a reasonable degree of sulfation (4 cm

3/g), and high hydrophobicity, which allowed for a high FFA conversion. This nanocatalyst showed a conversion reduction of only 8% after six cycles [

124].

MOF-based acidic catalysis focuses on the rational design of catalytic sites applied in esterification and transesterification. The development of these heterogeneous catalysts has evolved from using intrinsic Lewis acidic sites to designing novel active sites. This includes post-synthesis modification, defect engineering, and the design of bimetallic MOFs to create synergistic effects. An alternative is the creation of multifunctional hybrid materials, using the MOF as a support to immobilise other catalytically active components, such as ionic liquids, metallic or ceramic nanoparticles, etc. Recent research explores using sustainable and inexpensive precursors, such as ligands derived from PET waste or common ligands like EDTA. Optimal performance is achieved using microwave heating or subcritical conditions, consolidating these as up-and-coming alternatives. In this section, many studies report high catalytic performances under industrially unfeasible conditions, such as high temperatures, long times, and very high molar ratios. Some reports show both the loss of catalytic activity after a single cycle and the leaching of the active component, omitting stability data (

Table 2).

4.3. Biodiesel Production Catalysed by Bifunctional Catalysts

Bifunctional MOF-based catalysts combine the high surface area and porous structure of MOFs with the ability to carry out two or more catalytic functions simultaneously, enabling cascade reactions for more efficient processes, such as biodiesel production. MOFs have an ideal structure for incorporating and homogeneously distributing two or more catalytic sites with different functional groups to catalyse multiple consecutive reactions in a single step. In these reactions, a bifunctional catalyst allows the product of one reaction to become the reactant in the next without isolating the intermediates, simplifying processing and increasing process efficiency.

Bifunctional MOF catalysts play a crucial role in biodiesel production by integrating acidic and basic functionalities into a single porous structure. These dual catalysts enhance transesterification by simultaneously activating alcohol and triglyceride molecules. The bases enhance nucleophilicity, while the acids facilitate the electrophilicity of the carbonyl group. The porous structure of MOFs allows for a precise distribution of the active sites trapped within their structures, thus preserving their structural integrity. Acidic and basic centres are incorporated into the same material through covalent and ionic interactions to drive complex reactions, with additional properties such as electron delocalisation and interfacial dipoles that further accelerate the conversion to biodiesel [

78,

79].

Incorporating acidic sites using polyoxometalates presents a robust and versatile strategy for integrating the advantages of Brønsted and Lewis acids into MOF architectures. A representative example is the bifunctional catalyst AIL/HPMo/MIL-100(Fe), which was synthesised via a hydrothermal route starting with MIL-100(Fe) as a support structure, followed by a postsynthetic modification with Keggin-type HPMo. An AIL was subsequently immobilized on HPMo/MIL-100(Fe) by ion exchange of 1-(propyl-3-sulfonato)imidazolium hydrogen sulfate [SO

3H-(CH

2)

3-IM][HSO

4] with HPMo. This dual-acid catalyst exhibited synergistic catalytic behaviour, enabling efficient one-step esterification and transesterification of FFA and acidic soybean oil. The conversion of soybean oils to biodiesel was 92.3%, and the complete conversion of FFA to FAME. This process involved using methanol/acid oil at a molar ratio 30:1 under optimised conditions of 120 °C for 8 h. Furthermore, catalytic performance was maintained over five consecutive cycles [

125].

One strategy to increase the number of acid-base active sites in heterogeneous catalysts is the post-synthetic introduction of functionalities, thereby improving the bifunctional catalysis of lipids to biodiesel. In this context, arginine (Arg) and phosphotungstic acid (PTA) were incorporated into ZIF-8, composed of Zn

2+ and 2-methylimidazolate ions. The resulting hybrid material, Arg

2PTA/ZIF-8, integrated the Brønsted acidity of PTA and the Lewis basicity of Arg into the heterogeneous microenvironment of ZIF-8. Various reaction conditions were studied in the simultaneous one-step esterification and transesterification to evaluate catalytic efficiency. In addition, an acidic lipid model was used by mixing insect lipids (90 wt%) and oleic acid (10 wt%). For the catalyst, the optimal conditions were an Arg/PTA molar ratio of 2:1 and an Arg

2PTA/ZIF-8 weight ratio of 3:1. For the catalytic process, the optimal conditions were a reaction temperature of 60 °C, a catalyst loading of 3 wt%, a methanol/acidic lipid model molar ratio of 9:1, and a stirring speed of 500 rpm for 4 h. With these parameters, a maximum conversion of 94.15% was achieved. Recycling studies showed a conversion of 91% over four consecutive cycles [

126].

As we have seen, there is great interest in designing active, stable, and selective heterogeneous catalysts that enable efficient biodiesel production. In this context, Duan et al. (2024) simultaneously incorporated Ce

3+ and Cr

3+ ions (Ce(NO

3)

3⋅6H

2O and CrCl

3) into the ZIF-8 structure (Zn(NO

3)

2·6H

2O and 2-methylimidazole) during the crystallisation process, obtaining a nanocomposite called Ce-Cr/ZIF-8. The successful integration of the two cations influenced the growth of the MOF and introduced new properties to ZIF-8. The ratio of the two cations (Ce/Cr) and the ratio relative to ZIF-8 (Ce+Cr/Zn) were determining factors in the interconnection of the hybrid material. The authors evaluated biodiesel production using Ce-Cr/ZIFs-8 to catalyse the conversion of insect lipids. To do so, they explored a methanol/insect lipids molar ratio from 1:1 to 1:16, a catalyst loading from 1.5 to 3.5 wt%, a reaction temperature from 50 to 70 °C, and a reaction time from 6 to 10 h. The best biodiesel yield was 92.06% when the methanol/insect lipids molar ratio was 10:1 and the catalyst loading was 2.5 wt% at 65 °C for 8 h. The optimal catalyst conditions to achieve the best results were a Ce/Cr molar ratio of 2:1 and a Ce+Cr/Zn molar ratio of 20:1. The regenerated catalyst showed good catalytic potential after being reused four times, achieving a conversion of 75.66%. The biodiesel produced from insect lipids meets ASTM standards. The comparison of ZIFs-8 and Ce-Cr/ZIFs-8 demonstrates that exposed metal sites play a key role in converting lipids to biodiesel [

127].

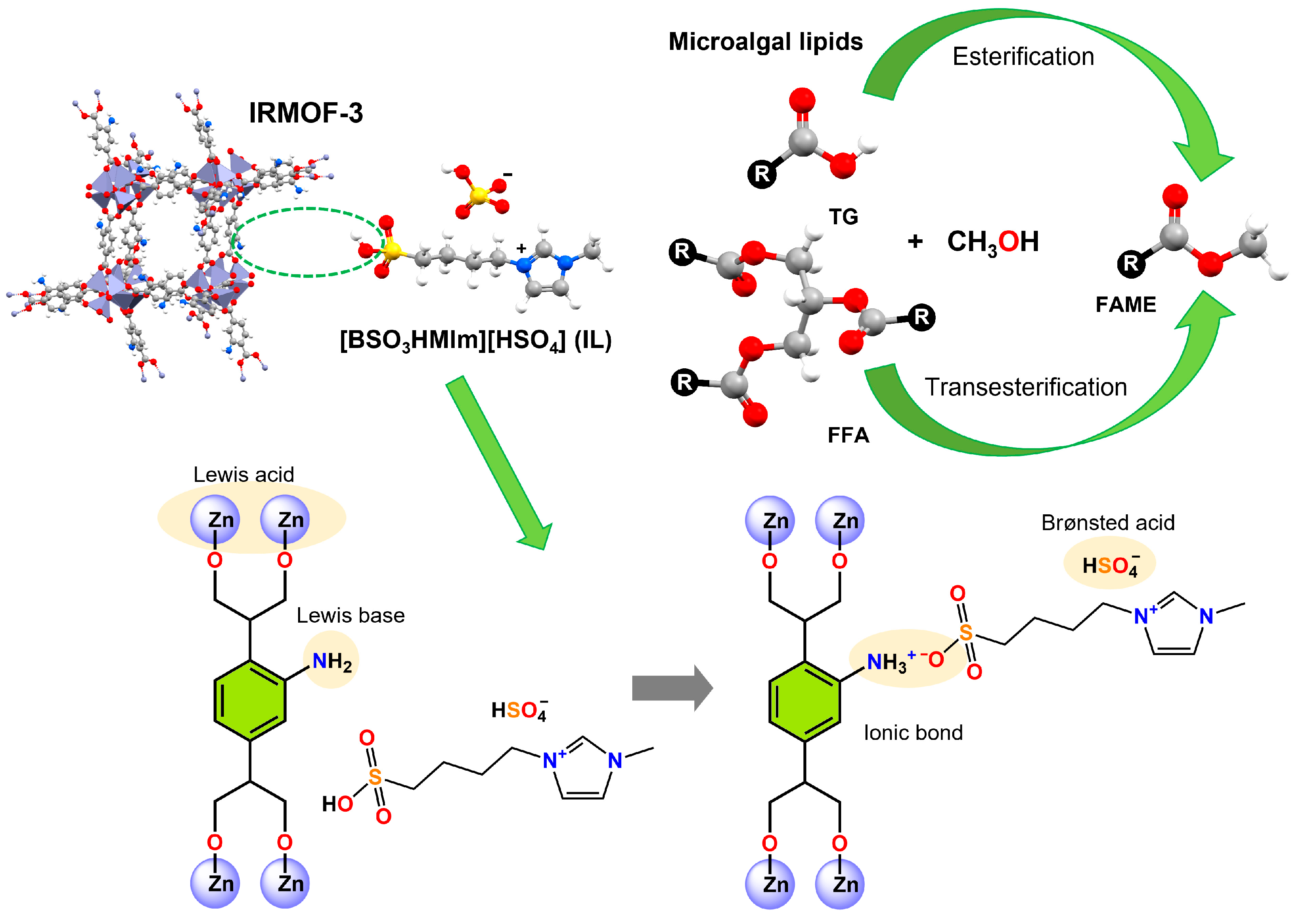

In a parallel approach, Brønsted acid ILs, such as 1-butylsulfonato-3-methylimidazolium bisulfate [BSO

3HMIm][HSO

4] with Brønsted acid functionalities, have been used to enhance the active catalytic sites of IRMOF-3. This MOF comprises octahedral units [Zn

4O(−COO)

6] and 2-amino-1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid molecules. The authors mention that IL was immobilised on IRMOF-3 by the acid-base reaction between the amino group of IRMOF-3 and the sulfonic acid group of the IL. The bifunctional catalyst (IL/IRMOF-3) demonstrated synergistic acid-base catalysis and was used in the esterification and transesterification of microalgal lipids containing 17% FFAs. The reaction was carried out at a methanol/lipid molar ratio of 20:1 with a catalyst loading of 3 wt% at 190 °C for 2 h. The system generated a biodiesel yield of 98.2%, and durability evaluations revealed sustained catalytic activity, with a conversion efficiency of 85.5% maintained after six successive reuse cycles.

Figure 19 illustrates the Lewis basic sites via the -NH

2 groups, the Lewis acidic sites via the Zn

2+ centres, and the incorporation of Brønsted acidic sites via (ILs to increase biodiesel production [

128].

Dual functionality within MOFs can be strategically designed by incorporating an additional Brønsted acid moiety into the porous architecture. In this synergistic configuration, the Lewis acid metal nodes in the MOFs act as electron-pair acceptors. In contrast, the Brønsted acidic sites contribute protons (H

+), increasing the overall catalytic performance in reactions such as transesterification. The bifunctional catalyst [(CH

2COOH)

2IM]HSO

4@H-UiO-66 was developed by bidentally coordinating a -COO- functionalized IL onto the unsaturated Zr

4+ ions of H-UiO-66, synthesised by a combination of hydrothermal treatment and propionic acid etching. The optimal conditions obtained using an RSM for the esterification of oleic acid with methanol were a molar ratio of 10.39:1, a reaction temperature of 80 °C, a reaction time of 5 h, and a catalyst loading of 6.28 wt%. The calculated biodiesel yield reached 93.71%, while the experimental value was 93.82%. Furthermore, the Brønsted-Lewis catalyst demonstrated good reusability, maintaining a conversion efficiency of 90.95% after five consecutive cycles [

129].

Harnessing the intrinsic basicity of some organic ligands, such as imidazole or 2-methylimidazole, commonly used in the construction of MOFs, along with the incorporation of Brønsted acidic sites, has proven to be an effective strategy for improving transesterification processes. Following this rationale, a robust bifunctional heterogeneous catalyst was synthesised by chemically incorporating a Keggin-type heteropolyacid (HPA) onto the zeolitic structure imidazolate-8 (ZIF-8). This new hybrid material (HPA/ZIF-8 or HZN-2) features a hierarchical nanometric core–shell structure, which confers high interconnectivity and surface area due to the thin layer of HPA placed on the surface of ZIF-8. Therefore, HPA/ZIF-8 is a bifunctional acid-base catalyst that enhances high-efficiency biodiesel production through the transesterification of rapeseed oil with methanol. This acid-base cooperativity enabled efficient transesterification at a methanol/rapeseed oil molar ratio of 10:1, carried out at >200 °C for 2 h with a catalyst loading of 4 wt%. The optimised catalyst achieved an exceptional FAME conversion of 98.02%, with stable catalytic performance over five consecutive reuse cycles [

130].

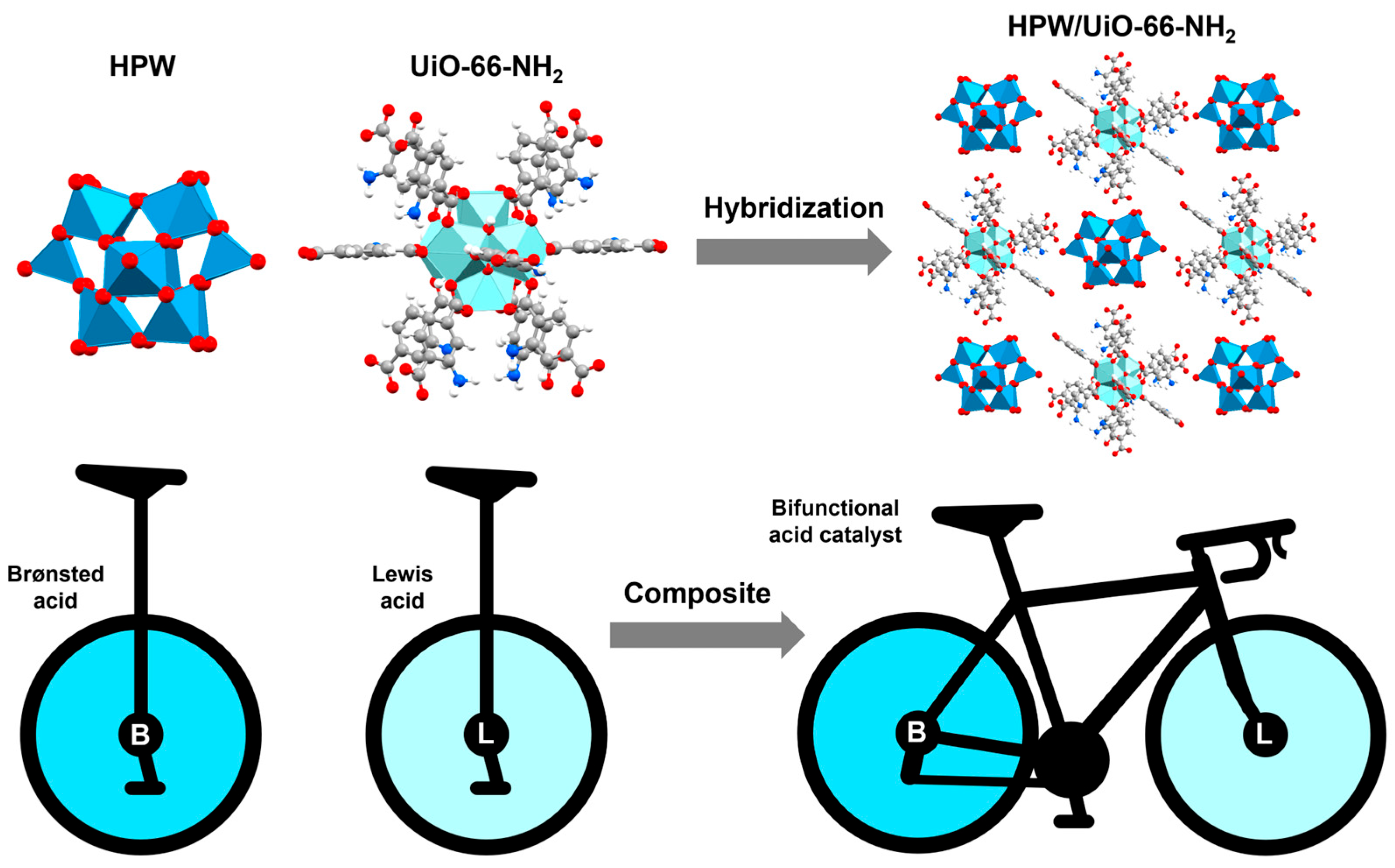

A complementary approach to biodiesel production involves obtaining heterogeneous catalysts that combine HPW (Brønsted acid) with the -NH

2 groups (Lewis base) and Zr

4+ cations (Lewis acid) functionalities present in UiO-66-NH

2. Therefore, HPW/UiO-66-NH

2 is obtained from ZrCl

4 and 2-aminoterephthalic acid, followed by the addition of HPW. HPW/UiO-66-NH

2 is a bifunctional heterogeneous catalyst with synergistic acid-base properties. The conditions obtained by RSM-BBD for the transesterification reaction predicted a biodiesel yield of 98.2% at a methanol/oleic acid molar ratio of 16:1, a reaction temperature of 82 °C for 3.7 h, and a catalyst loading of 3.5 wt%. However, experimentally, HPW/UiO-66-NH

2 allowed the conversion of oleic acid to biodiesel (95.4%) using a methanol/oil molar ratio of 15:1, a reaction temperature of 80 °C for 4 h, and a catalyst loading of 2 wt%. Additionally, HPW/UiO-66-NH

2 allowed the conversion of high-acid

Euphorbia lathyris L. oil to biodiesel (91.2%) using a methanol/oil molar ratio of 40:1, a reaction temperature of 180 °C for 8 h, and a catalyst loading of 3.5 wt%. The catalyst exhibited good reusability, maintaining a conversion efficiency from 97.9% to 91.0% (methanol/oleic acid 15:1, catalyst 2 wt%, 50 °C) after four successive cycles with minimal structural degradation [

131] (

Figure 20).

Hybrid materials formed by mixing several components with specific properties can preserve each component’s attributes in the final composite. In this context, Cheng et al. (2021) effectively immobilised a Brønsted acid component such as HPW onto MOF. ZIF-67 was obtained from Co(NO

3)

2·6H

2O and 2-methylimidazole using ultrasound and centrifugation, followed by adding HPW while maintaining the ultrasound. The resulting composite, HPW/ZIF-67, is a structurally robust material exhibiting synergistic interaction between Brønsted and Lewis acid-base functionalities. The dative Co-N bonds in ZIF-67 decreased due to incorporating HPW, favouring the formation of coordinatively unsaturated Co

2+ cations and external 2-methylimidazolate anions. This bifunctional architecture facilitated the transformation of microalgal lipids, characterised by an FFA content of 17%, into FAMEs via simultaneous esterification and transesterification pathways. The reaction was carried out using a methanol/microalgal lipid molar ratio of 20:1, under optimised conditions of 200 °C for 1.5 h, with a minimum catalyst loading of 1 wt%. Surprisingly, the process achieved a biodiesel yield of 98.5%, and the catalyst exhibited exceptional reusability, maintaining a conversion efficiency of 91.3% over six successive reaction cycles [

132] (

Figure 21).

MOFs possess diverse functional groups with desirable properties that enable post-synthetic modification. For example, basic functional groups can be incorporated into the catalyst design for base-catalysed transesterification. A notable example is the bifunctional material NH

2-MIL-101(Cr)-Sal-Zr, synthesised by hydrothermal assembly of the amino-functionalized MOF (NH

2-MIL-101(Cr)), followed by the condensation of salicylaldehyde (Sal) with the -NH

2 group of the MOF and subsequent coordination with Zr

4+ ions (Zr). This engineered structure integrates acidic (Lewis centres Zr

4+ and Cr

3+) and basic (−NH

2) catalytic sites. The esterification of oleic acid with methanol was performed at a 1:10 molar ratio, using 4 wt% of the catalyst under optimised conditions of 60 °C for 4 h. Under these conditions, the process produced a biodiesel conversion of 74.1%, which was maintained after six consecutive reuse cycles (73.6%). When the temperature was raised to 67 °C, biodiesel conversion increased to 74.8% [

133].

Mechanochemical synthesis is a green technique successfully used to prepare bifunctional catalysts based on UiO-66(Zr) functionalized with various groups, such as -NH

2 or -NO

2. This green approach leads to a UiO-66(Zr) structure with defects that allow esterification and transesterification reactions to produce biodiesel. The order of catalytic activity was UiO-66(Zr)-NH

2 > UiO-66(Zr)-NO

2 > UiO-66(Zr), so we will focus on the results for UiO-66(Zr)-NH

2. This MOF combines Lewis acid zirconium(IV) centres with basic Brønsted functionalities (−NH

2). Its catalytic efficacy was demonstrated in the esterification of methanol with oleic acid at a 39:1 molar ratio, carried out under mild conditions (60 °C, 4 h) with a catalyst loading of 6 wt%. UiO-66(Zr)-NH

2-green achieved a biodiesel yield of 97.3%, maintaining a conversion efficiency greater than 50% after three consecutive reuse cycles. The superior activity of UiO-66(Zr)-NH

2-green confirms the synergy of the amino group (Brønsted base) with the Zr

4+ ion (Lewis acid) [

134] (

Figure 22).

MOFs containing zirconium(IV) bound by terephthalate (UiO-66) or 2-aminoterephthalate (UiO-66-NH

2) ligands are active, stable, and reusable heterogeneous acid catalysts for the esterification of saturated and unsaturated biomass-derived FFAs with ethanol and methanol. In this regard, Cirujano et al. (2015) used these two catalysts to obtain biodiesel (FAEE and FAME). To do so, they started with 1 mmol of lauric acid as the oil source, obtaining yields with methanol of >99% and 94% for UiO-66-NH

2 and UiO-66, respectively; and with ethanol of 99% and 64% for UiO-66-NH

2 and UiO-66, respectively. In both cases, the same conditions were used: an alcohol/oil ratio of 26:1, a catalyst loading of 8 wt%, a reaction temperature of 60 °C (methanol) and 78 °C (ethanol), and a reaction time of 2 h (methanol) and 8 h (ethanol). The lower activity of UiO-66 compared to UiO-66-NH

2 measured by GC-MS indicates a possible cooperative acid-base catalysis for UiO-66-NH

2, leading to a dual activation of both the acid by assisted deprotonation and the coordinatively unsaturated zirconium vacancies. Esterification tests with other oils (linoleic, α-linoleic, stearic, oleic, palmitic) catalysed by these zirconium(IV) MOFs allow the preparation of different compounds of interest [

135].

The in situ synthesis of MOFs with multimetallic centres is essential for constructing materials with diverse properties derived from their multifunctional sites. For this reason, Abou-Elyazed et al. (2022) obtained a bimetallic MOF based on UiO-66(Zr) doped with Ca

2+ ions by direct solvent-free synthesis. The synthesis of UiO-66(Zr) was carried out using ZrOCl

2∙8H

2O and trimesic acid. The MOF was doped using different amounts of Ca(OH)

2 (x = 0–20 wt%), different crystallisation temperatures (y = 130–180 °C), and different crystallisation times (t = 12–48 h). The optimal catalyst (UiO-66(Zr/Ca)x-y-t) was obtained with the addition of 5 wt% of Ca(OH)

2 at 130 °C in 24 h, and was named UiO-66(Zr/Ca)5-130-24. Under these conditions, the bimetallic catalyst showed a specific surface area of 1120 m

2/g and a pore volume of 0.77 cm

3/g. The authors studied the effect of incorporating Ca

2+ ions on the catalytic performance of the esterification of oleic acid with methanol. The optimal reaction conditions were a methanol/oleic acid ratio of 39:1, a catalyst loading of 6 wt%, a temperature of 60 °C, and a reaction time of 4 h. The catalytic performance of UiO-66(Zr/Ca)5-130-24 (98%) was much better than that of the previously reported undoped UiO-66(Zr)

-green catalyst (86%) [

132]. This is due to the increase in acidic and basic active sites and the generation of more defects, which benefit and improve reactivity. After reactivation, UiO-66(Zr/Ca)5-130-24 retained good catalytic performance after five reuse cycles (84%) [

136].

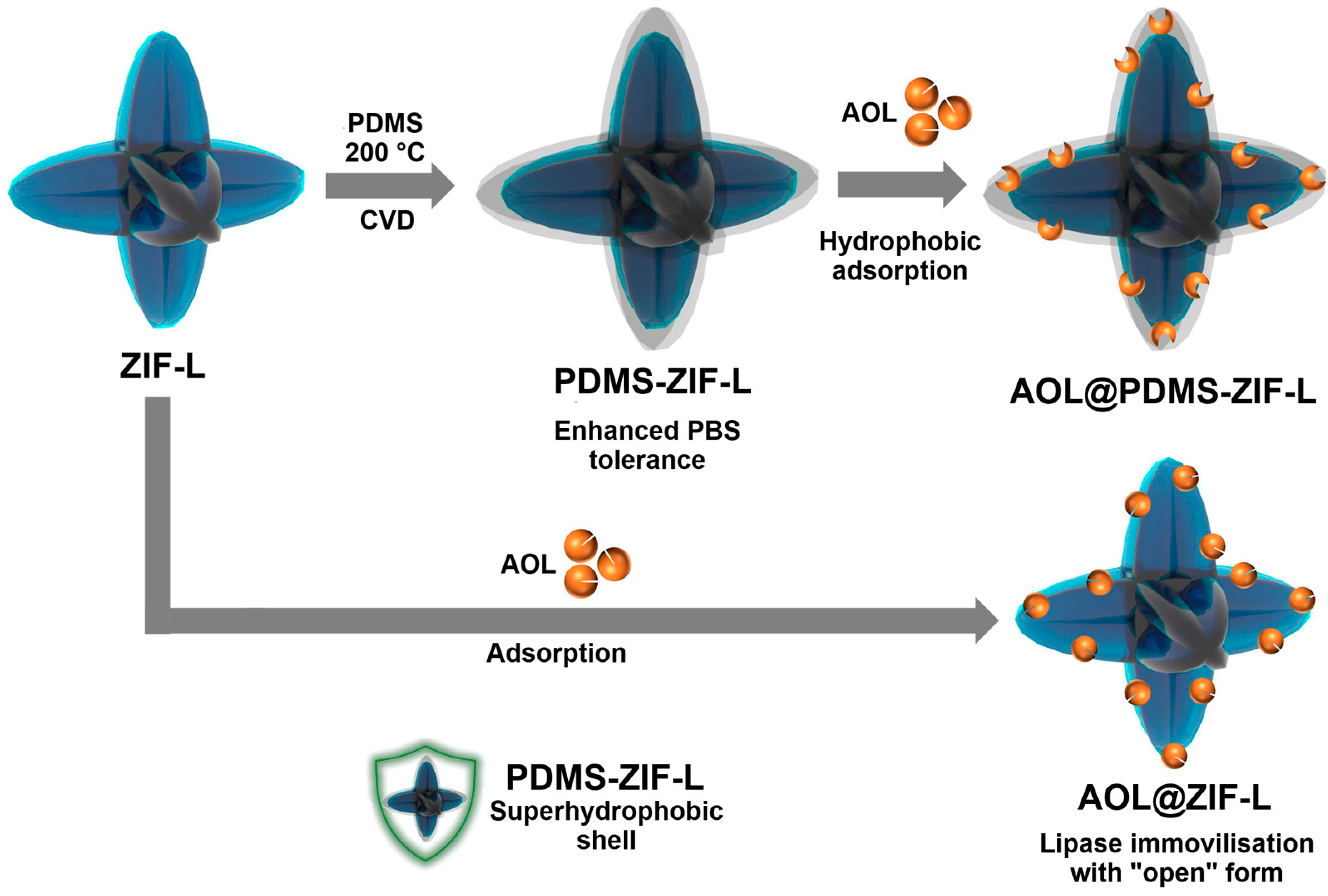

Mao et al. (2023) designed a novel bifunctional catalyst to enhance the conversion of microalgal lipids into biodiesel. For this purpose, ZIF-90 was synthesized from Zn(NO

3)

2·6H

2O and imidazol-2-carboxaldehyde. Subsequently, this MOF was modified with sulfamic acid (SA), which provided protons, broke Zn–N coordination bonds, and formed new imine bonds (C=N), thus increasing the number of Brønsted acidic sites (–NH and SA groups) and Lewis acidic sites (coordinatively unsaturated Zn