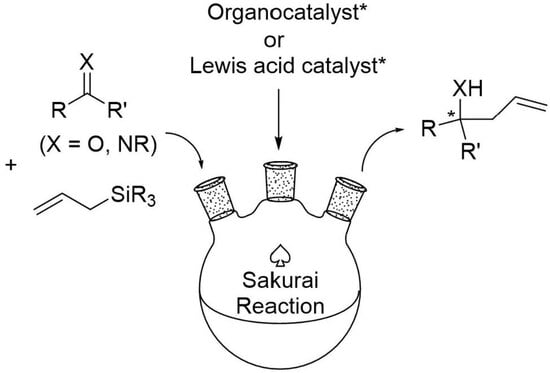

Recent Developments in the Catalytic Enantioselective Sakurai Reaction

Abstract

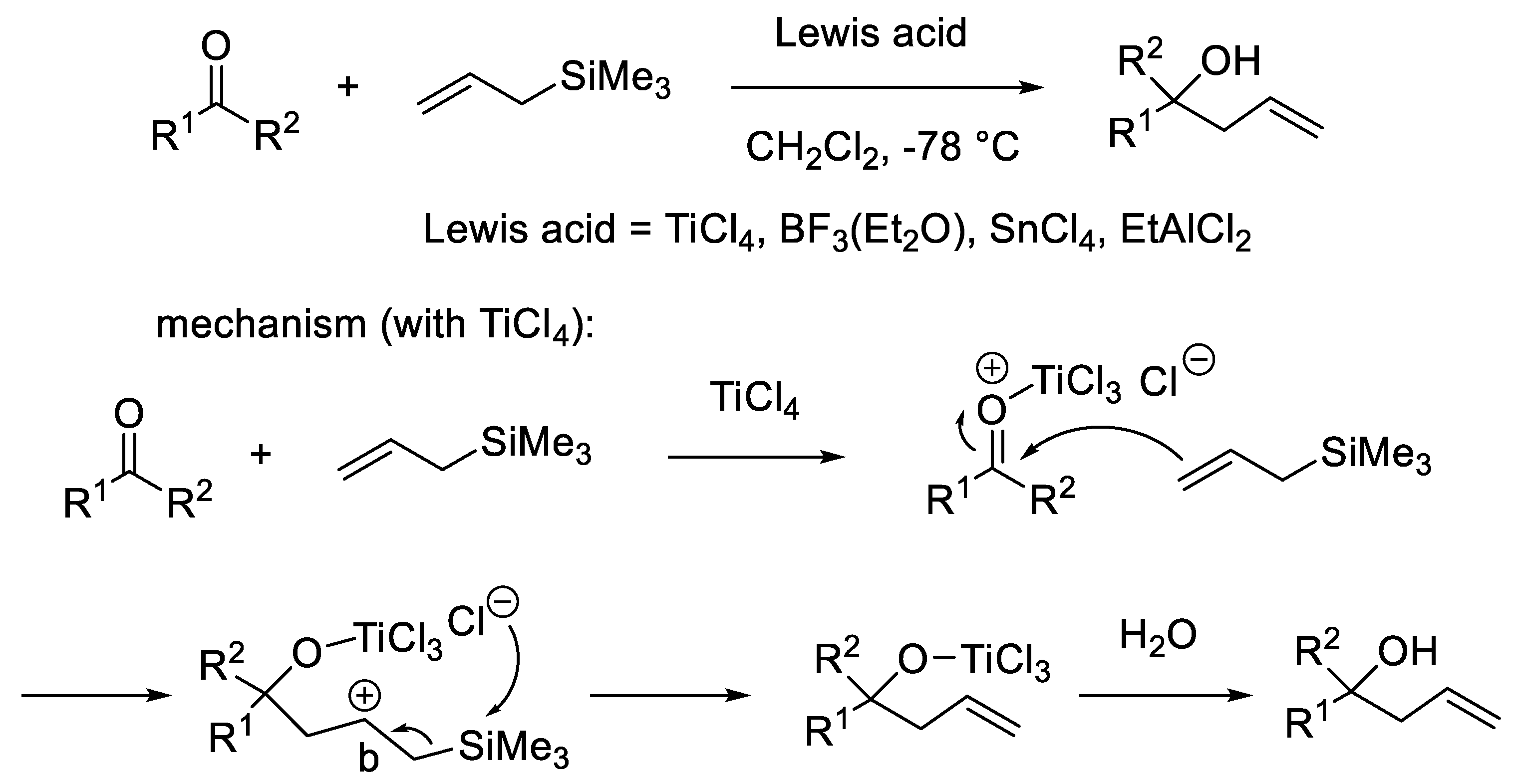

1. Introduction

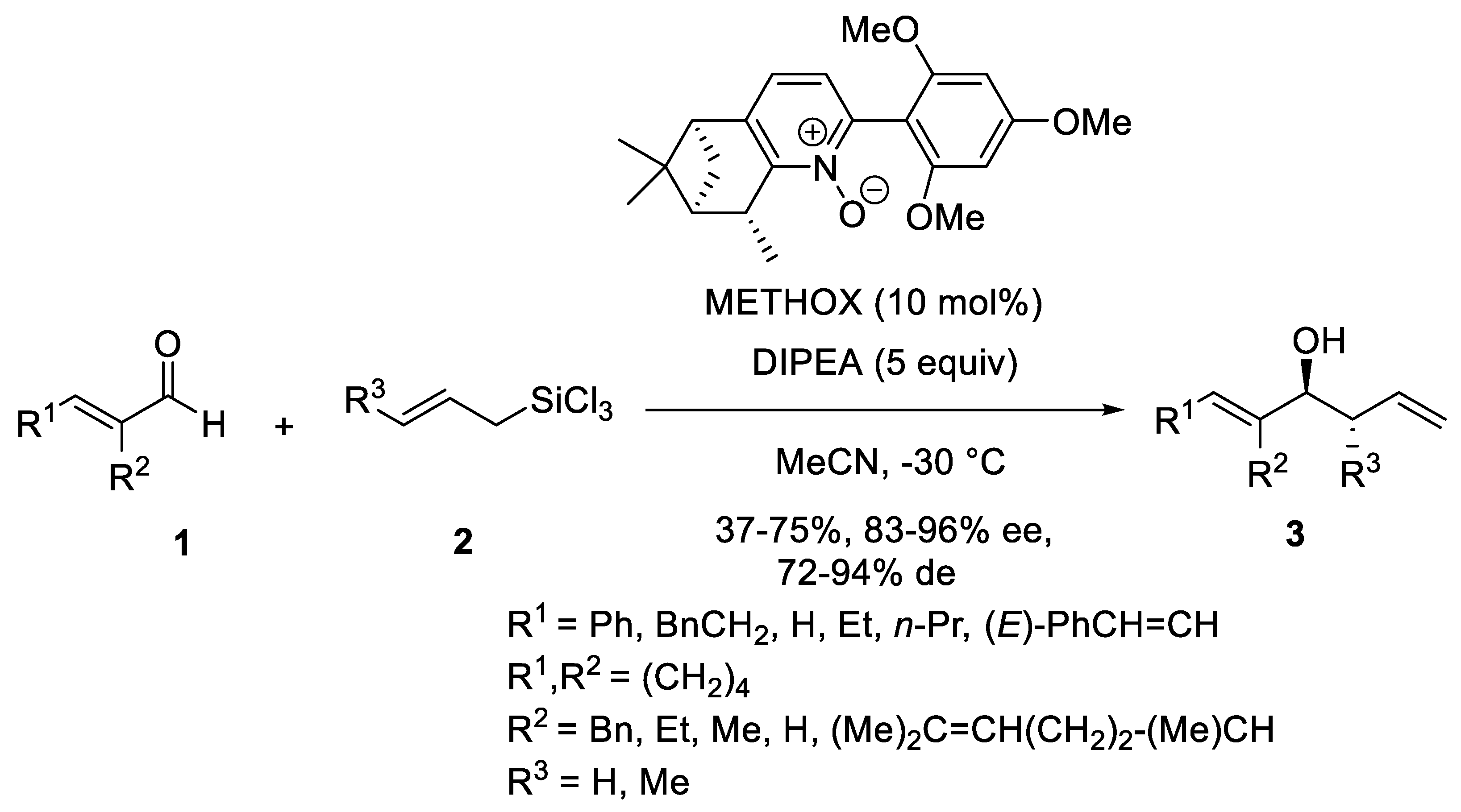

2. Enantioselective Organocatalytic (Aza)-Sakurai Reactions

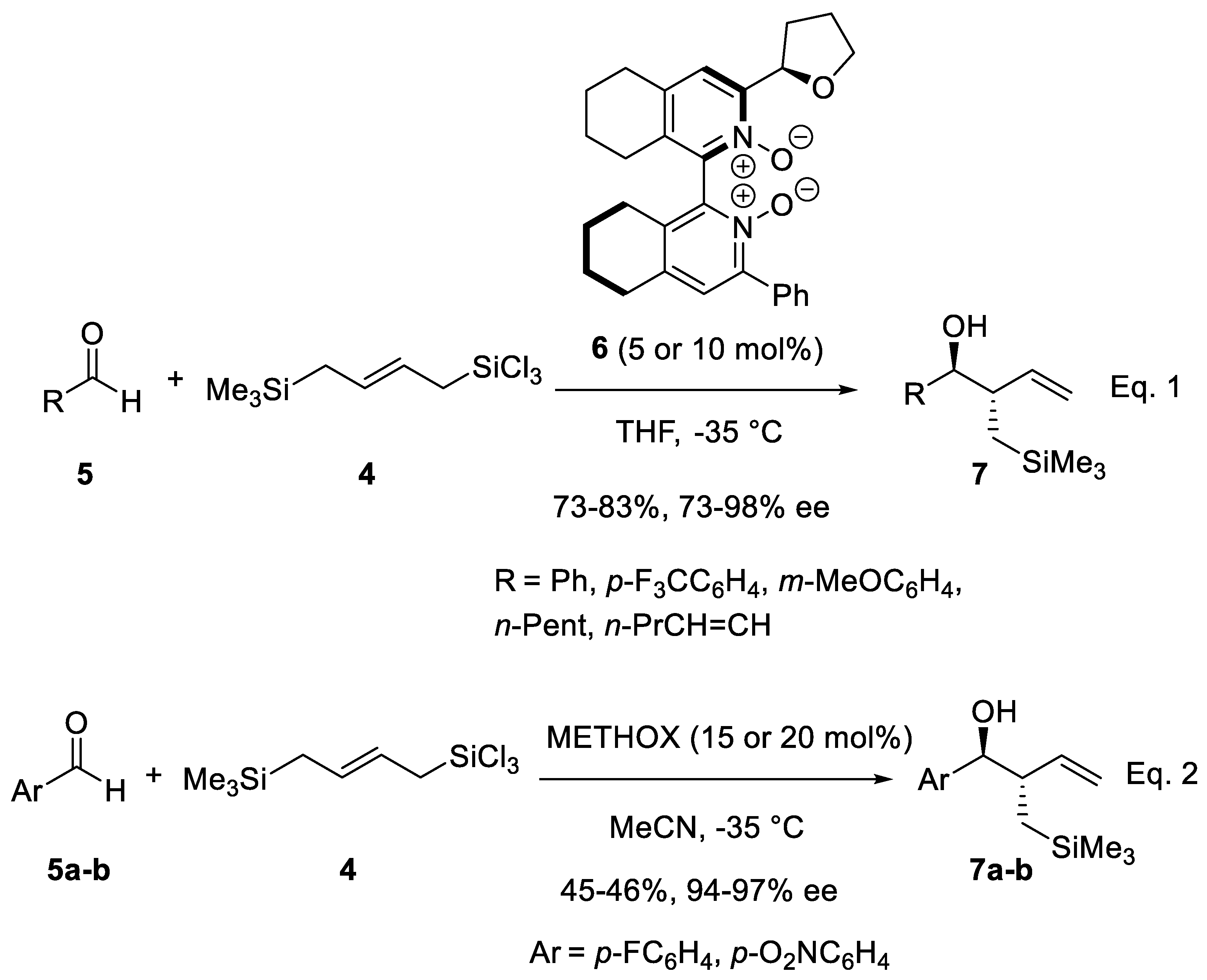

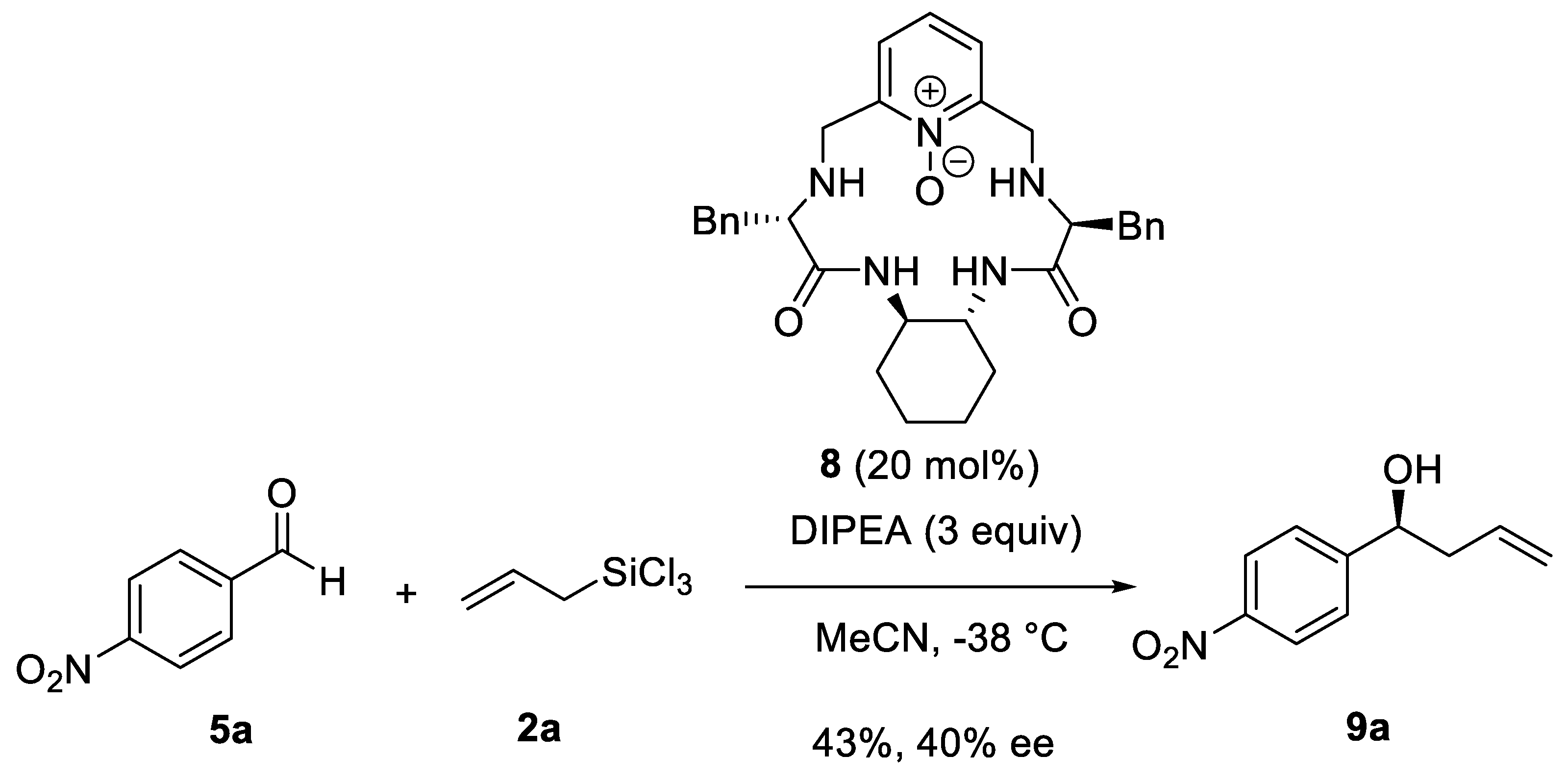

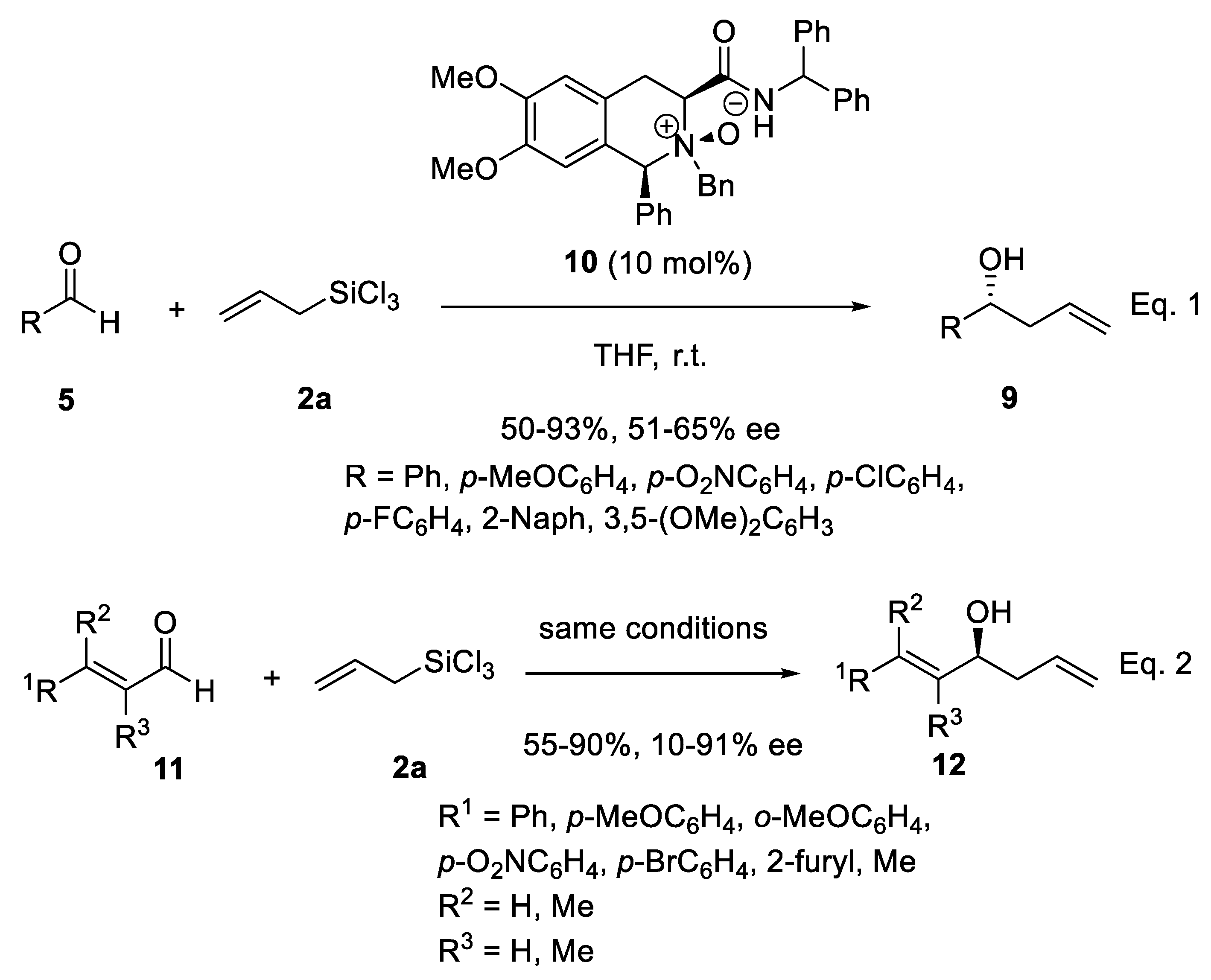

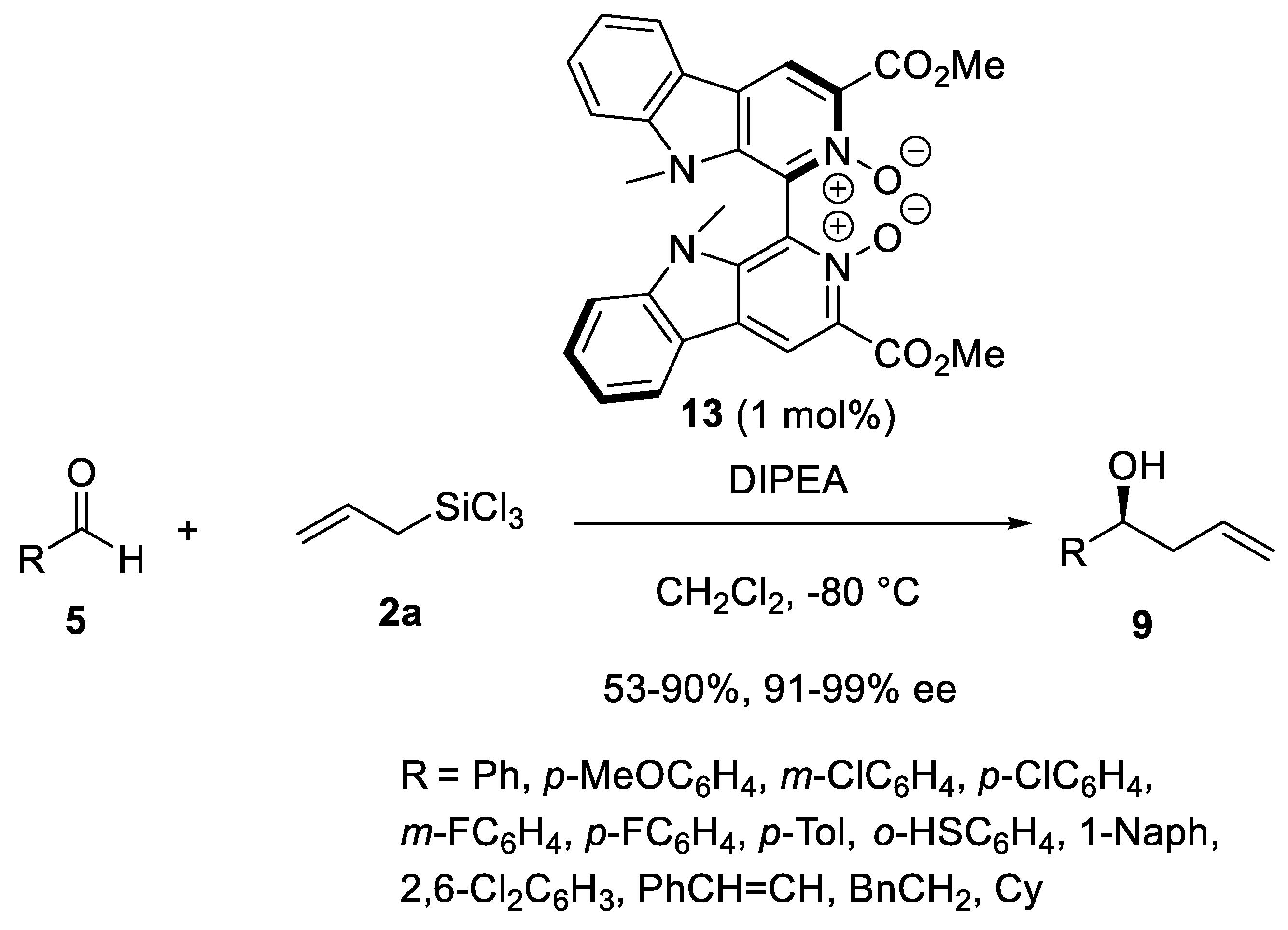

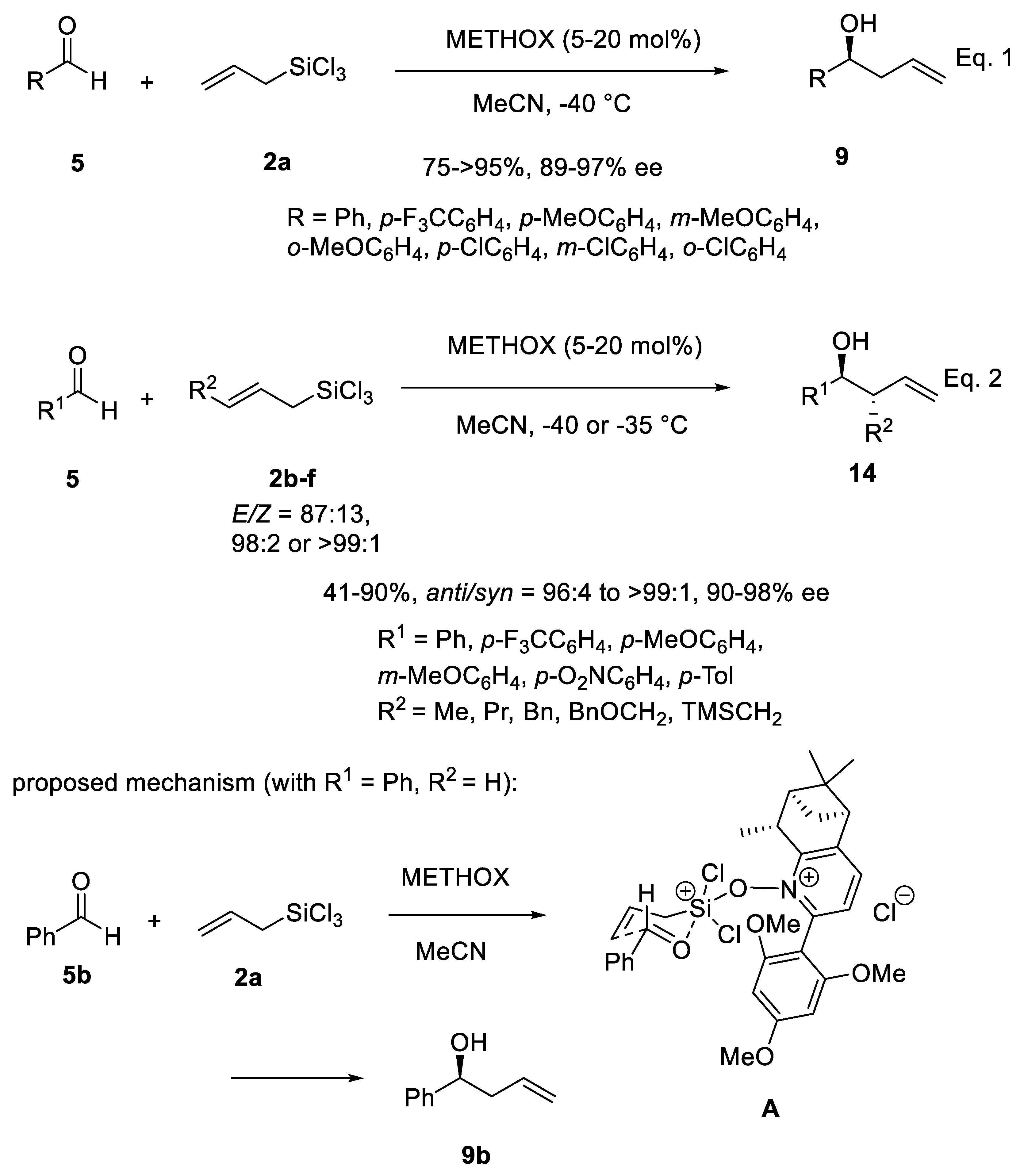

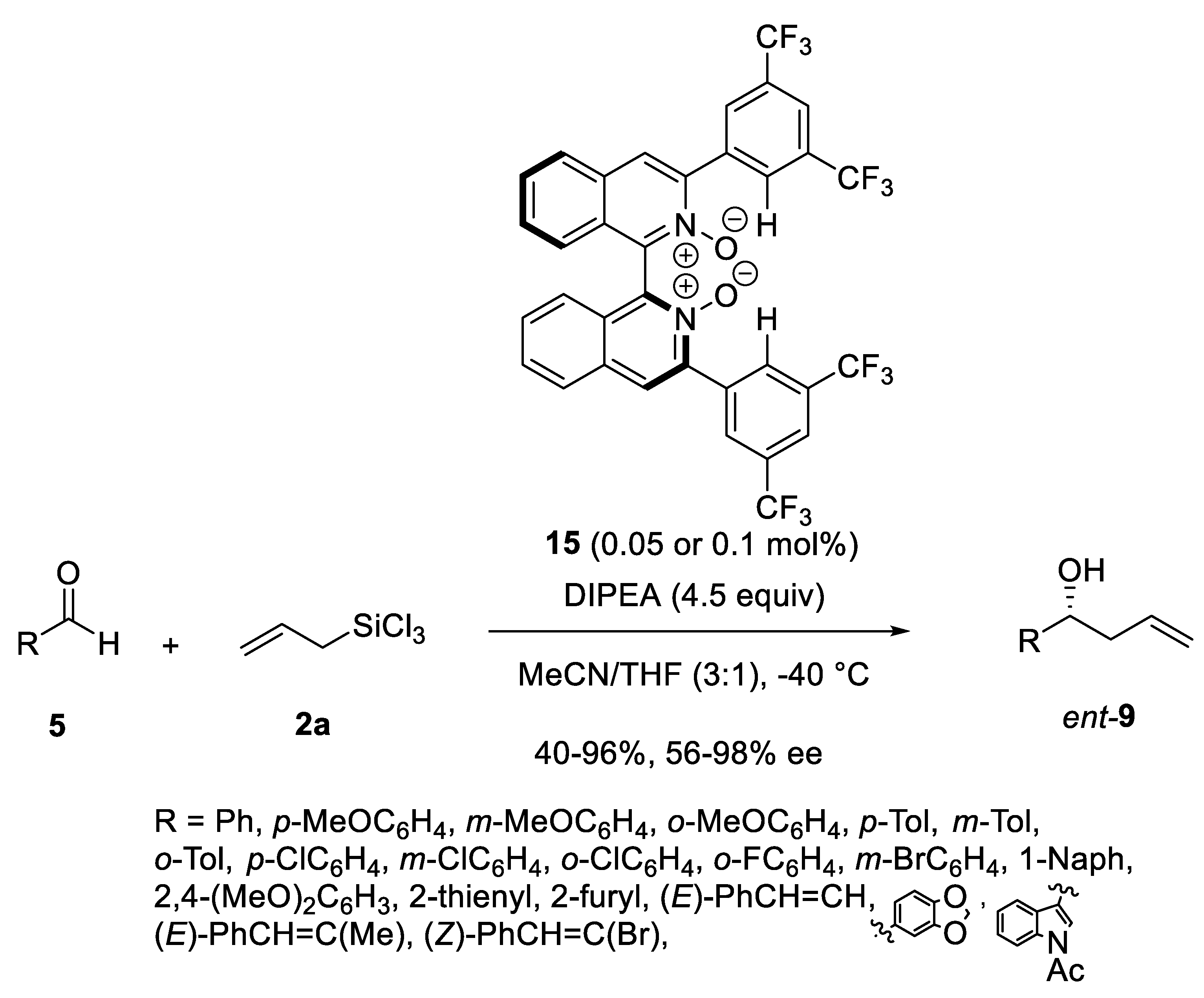

2.1. N-Oxide Catalysts in Enantioselective Sakurai Reactions of Aldehydes

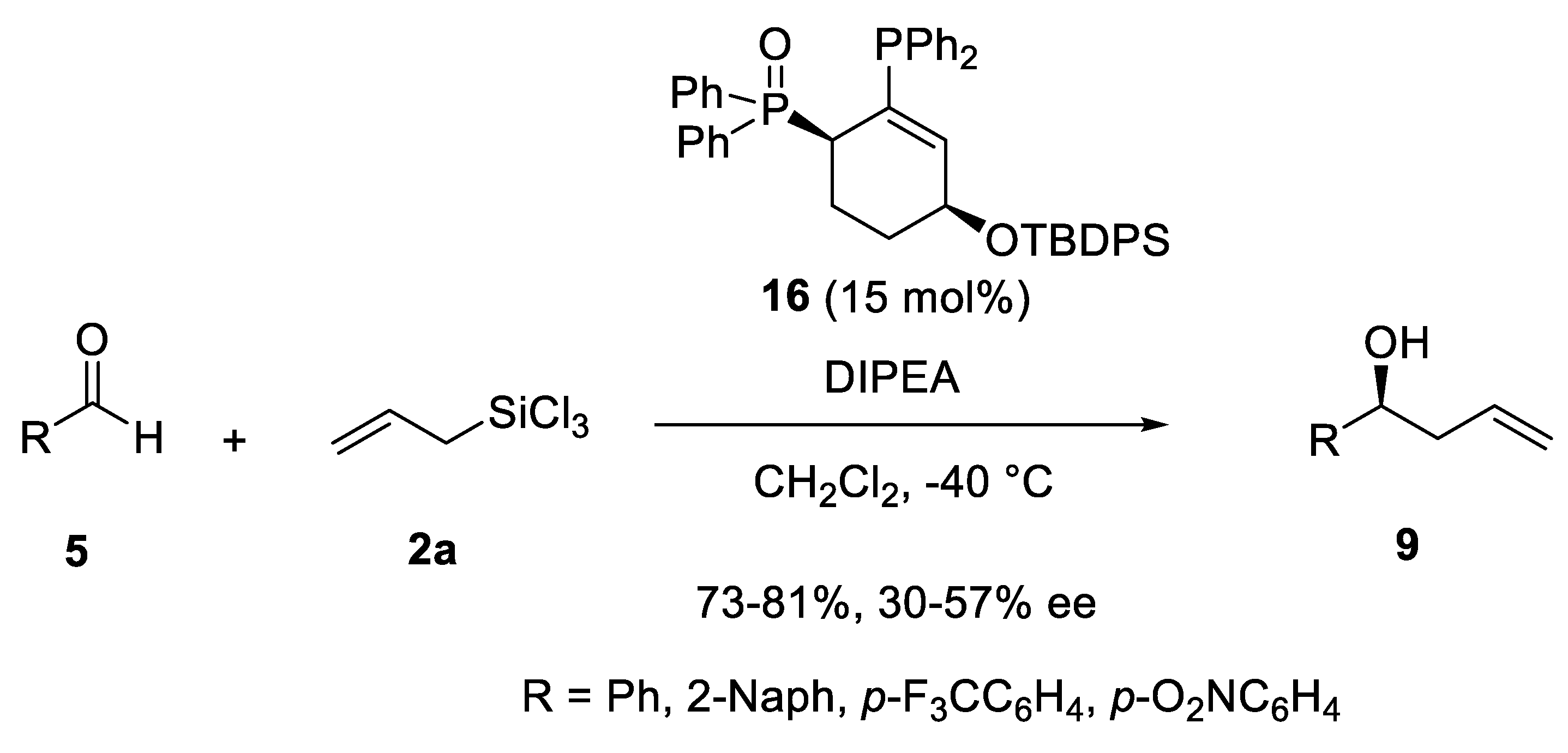

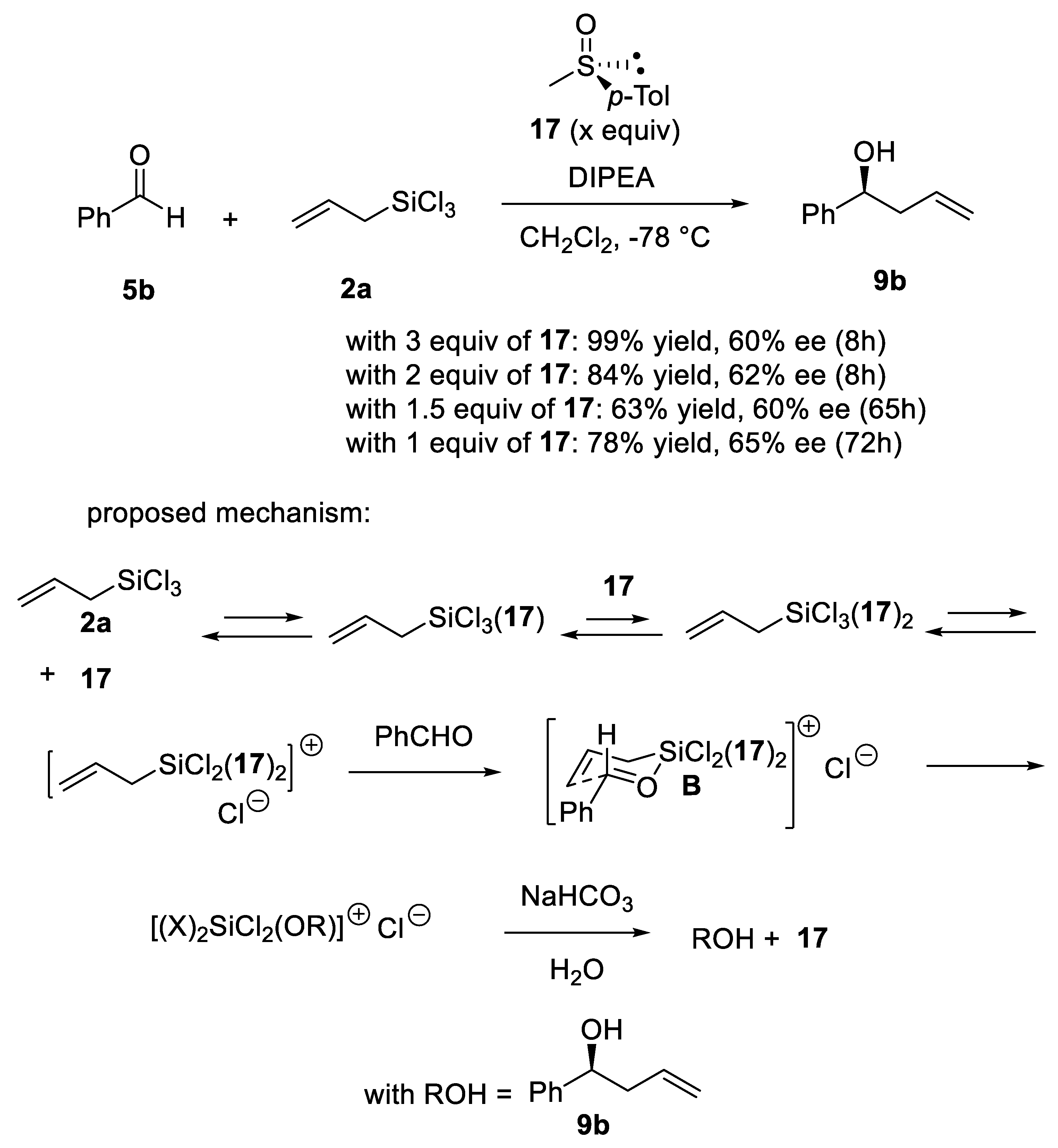

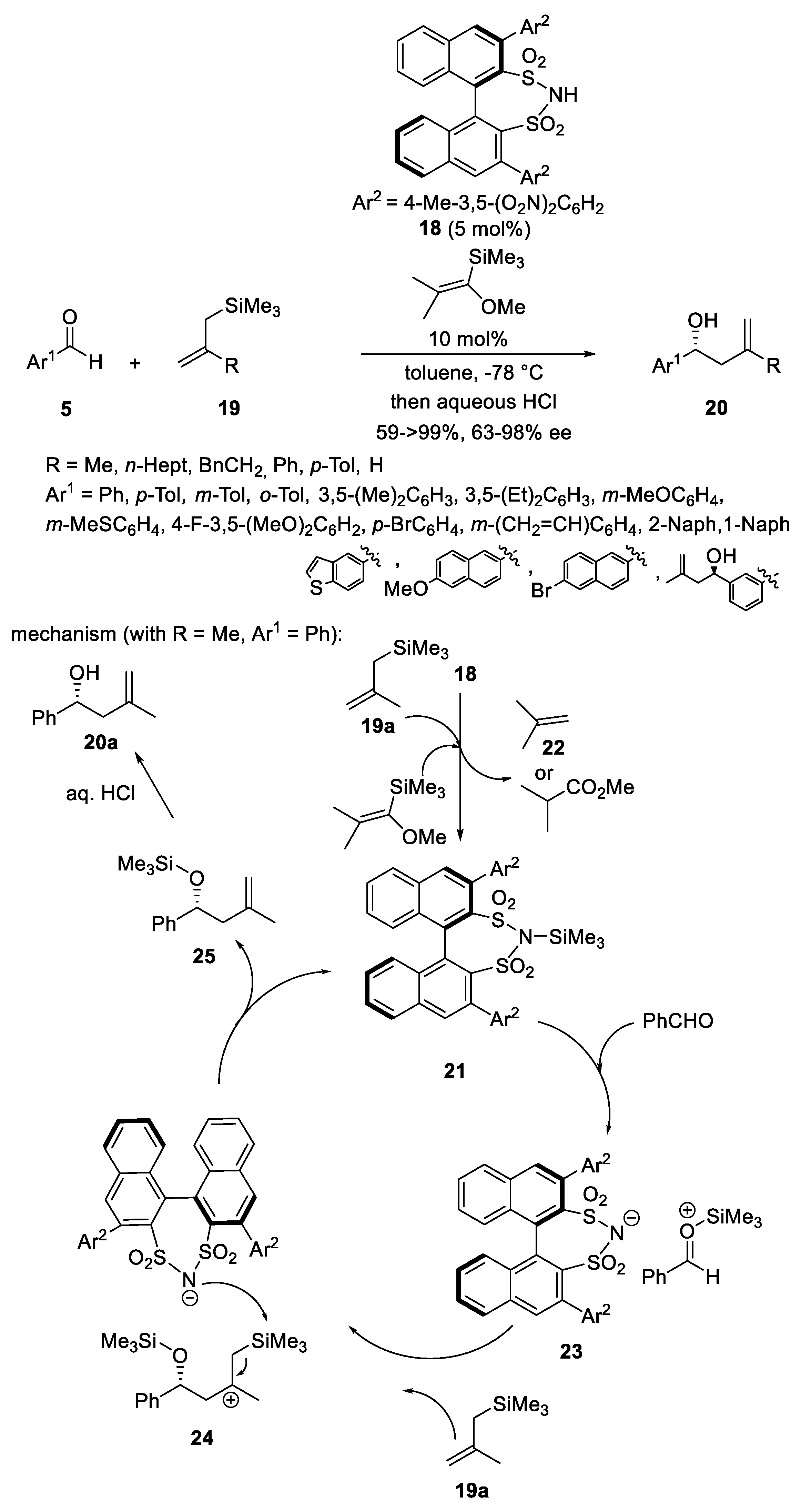

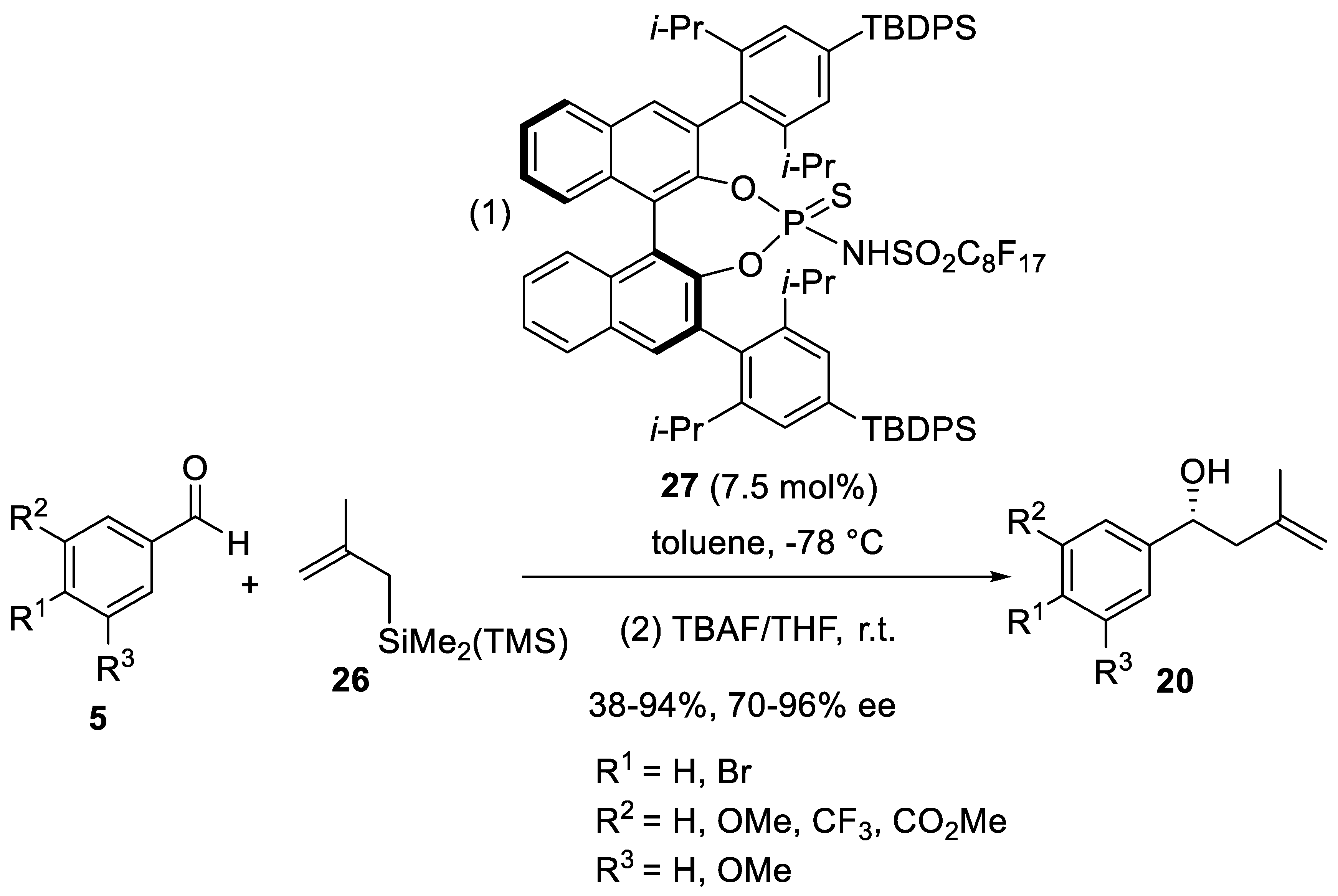

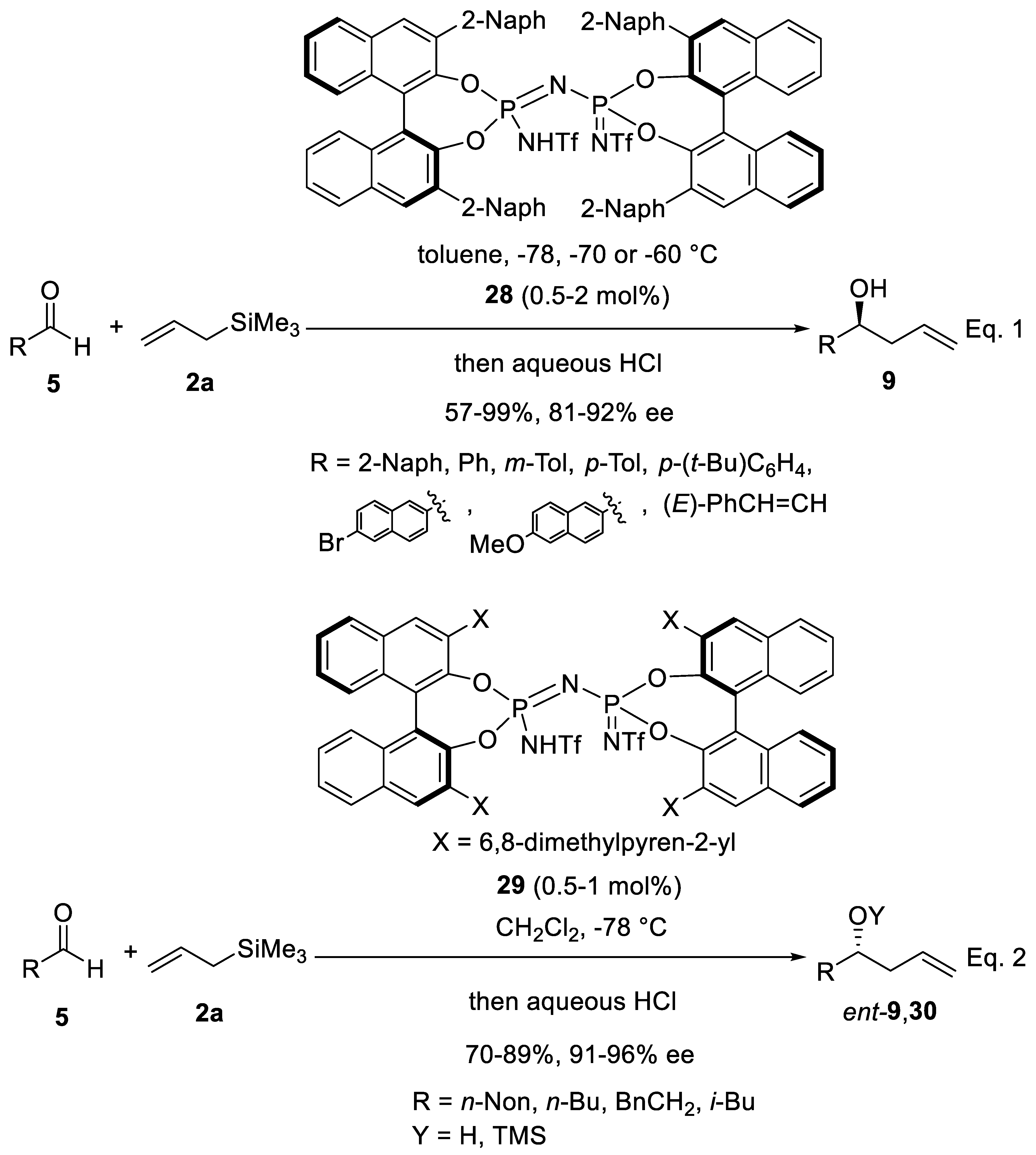

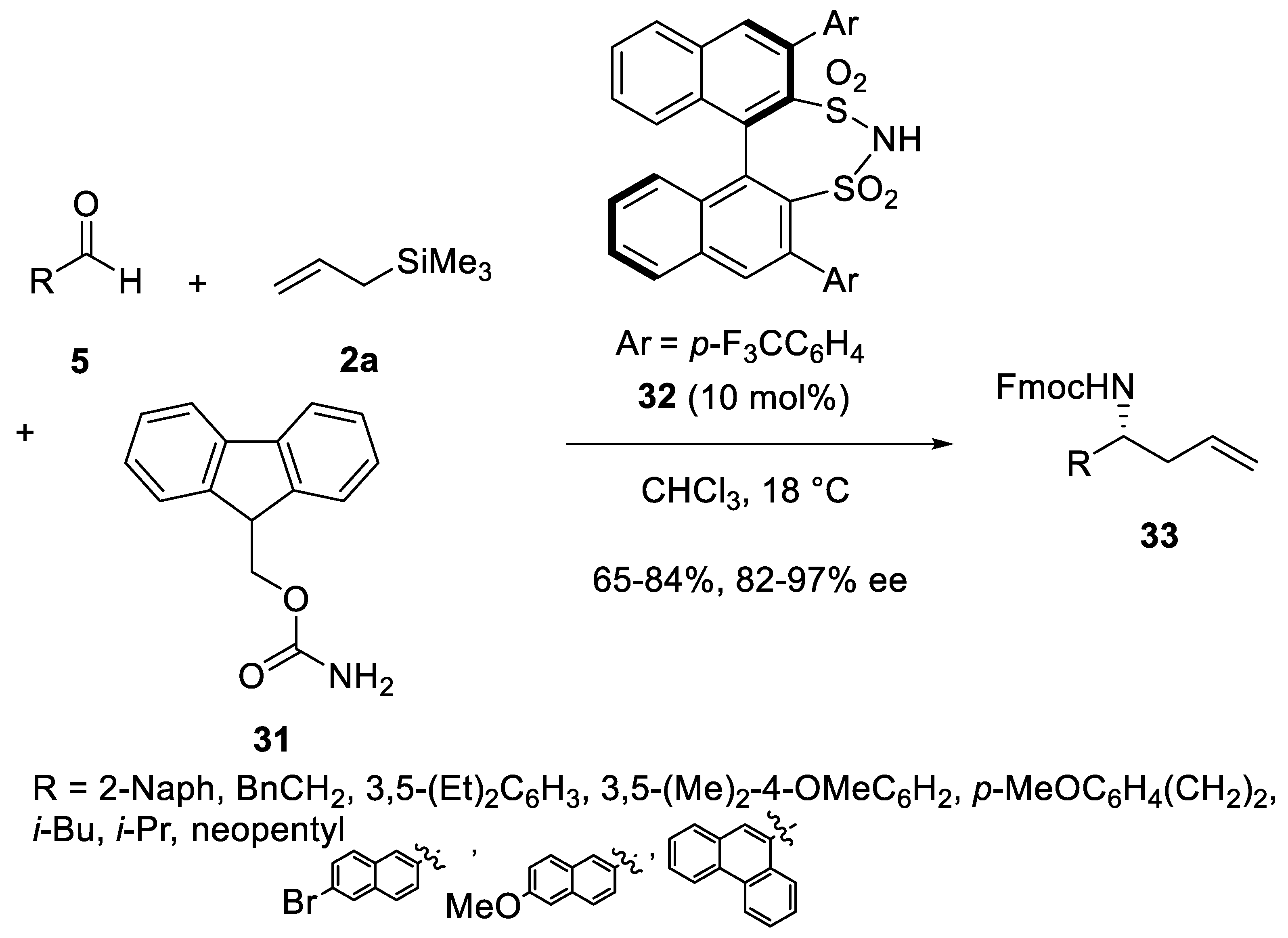

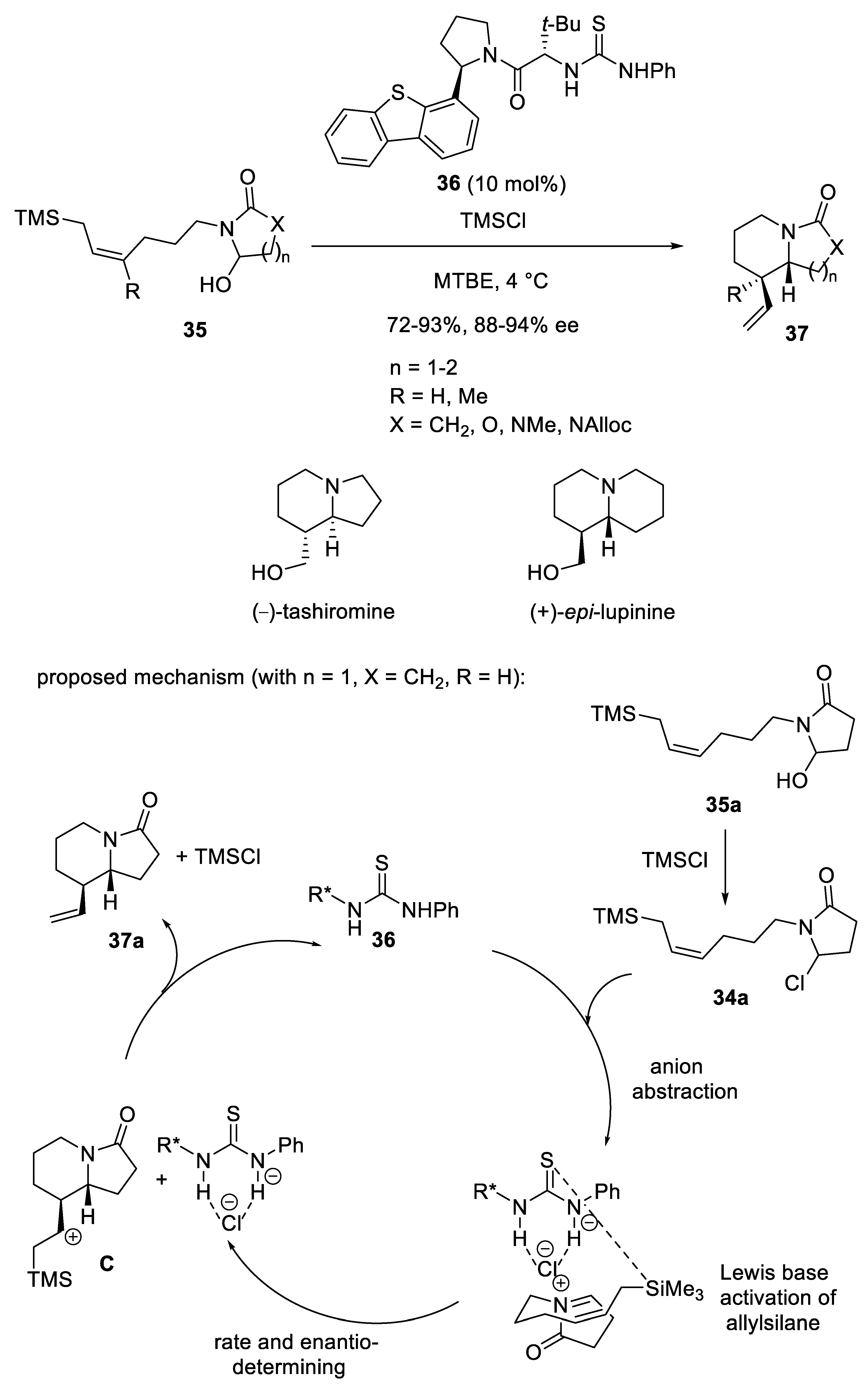

2.2. Other Organocatalysts in Enantioselective (Aza-)Sakurai Reactions

3. Enantioselective Metal/Boron-Catalyzed Sakurai Reactions

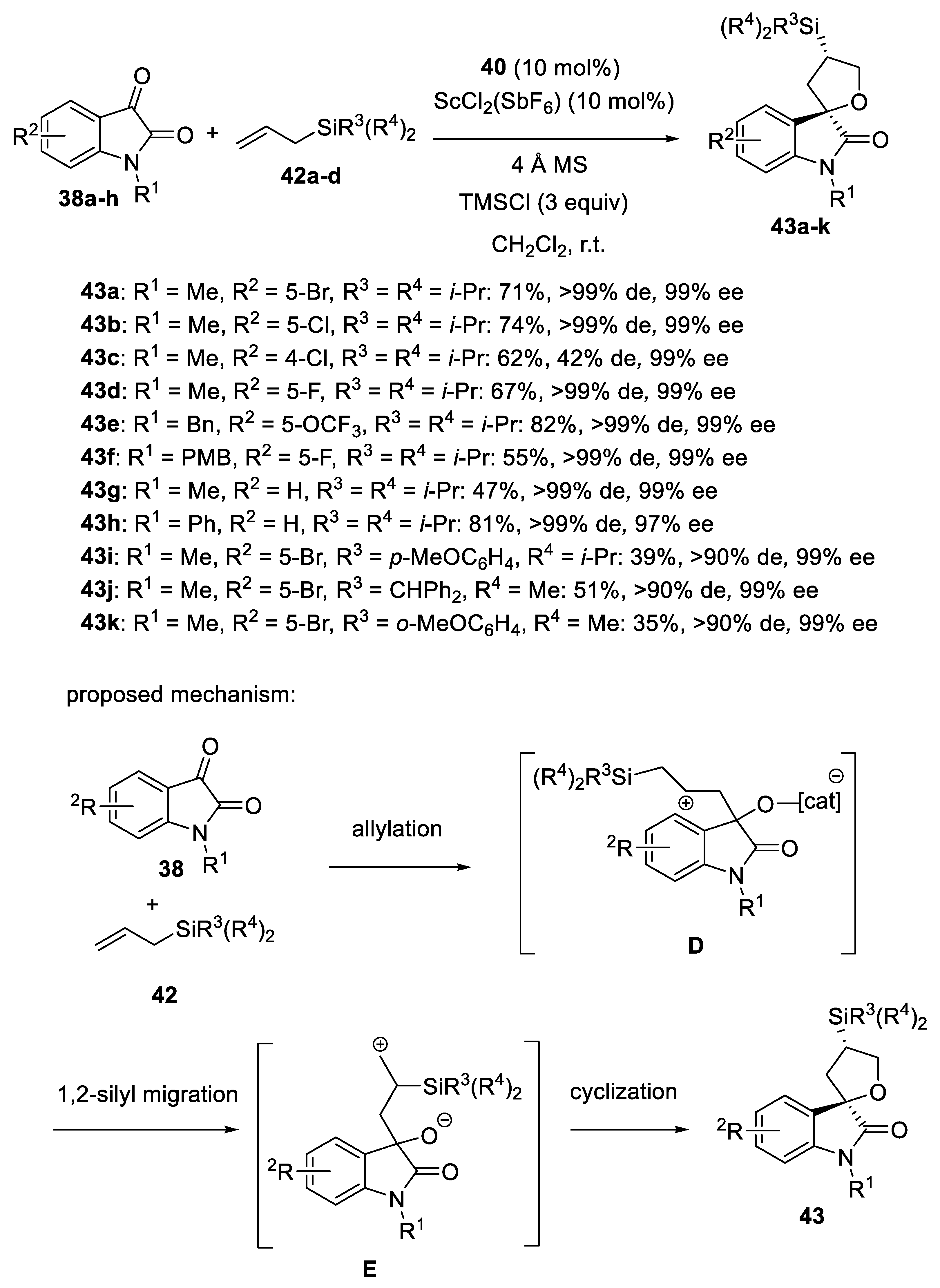

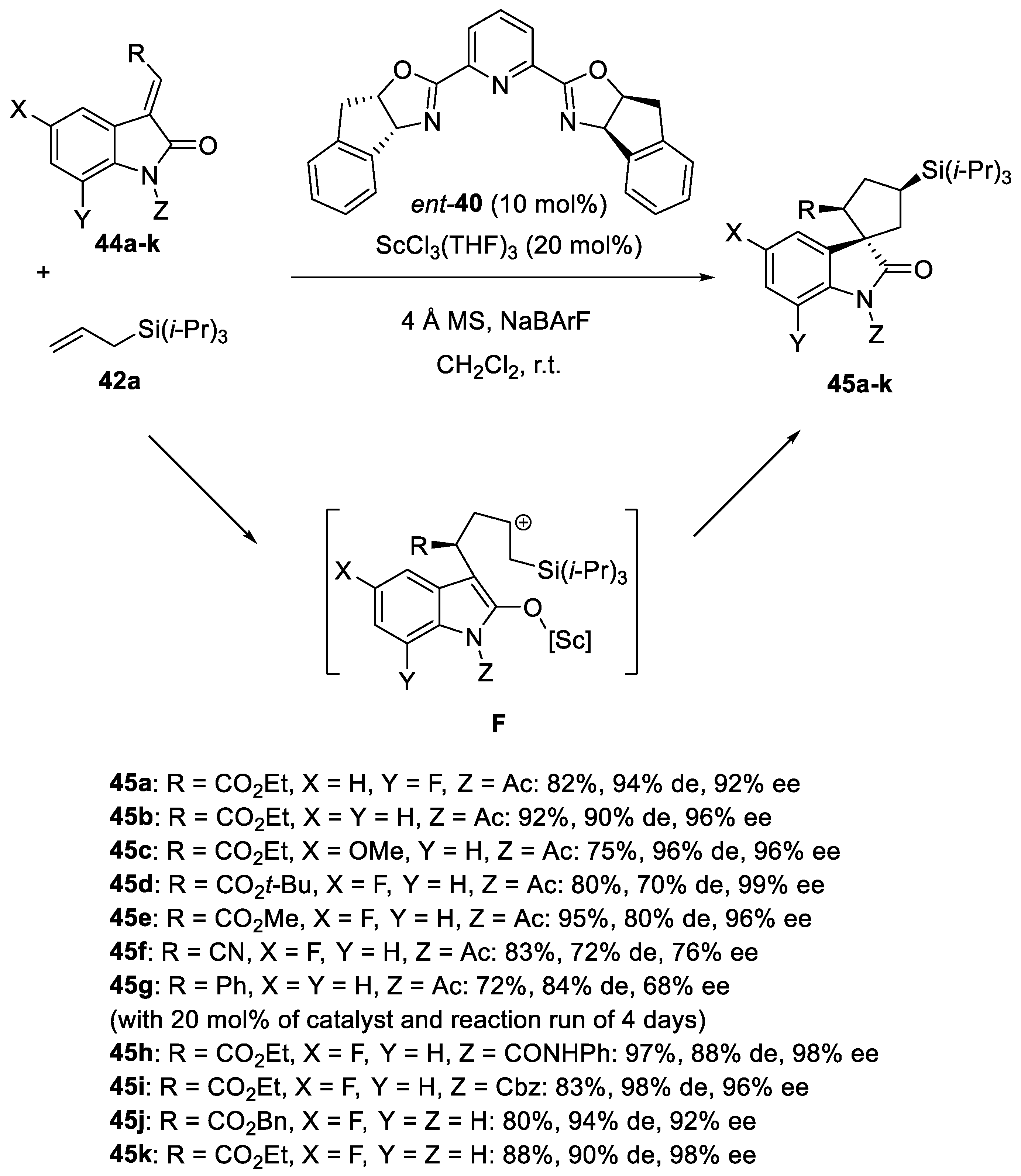

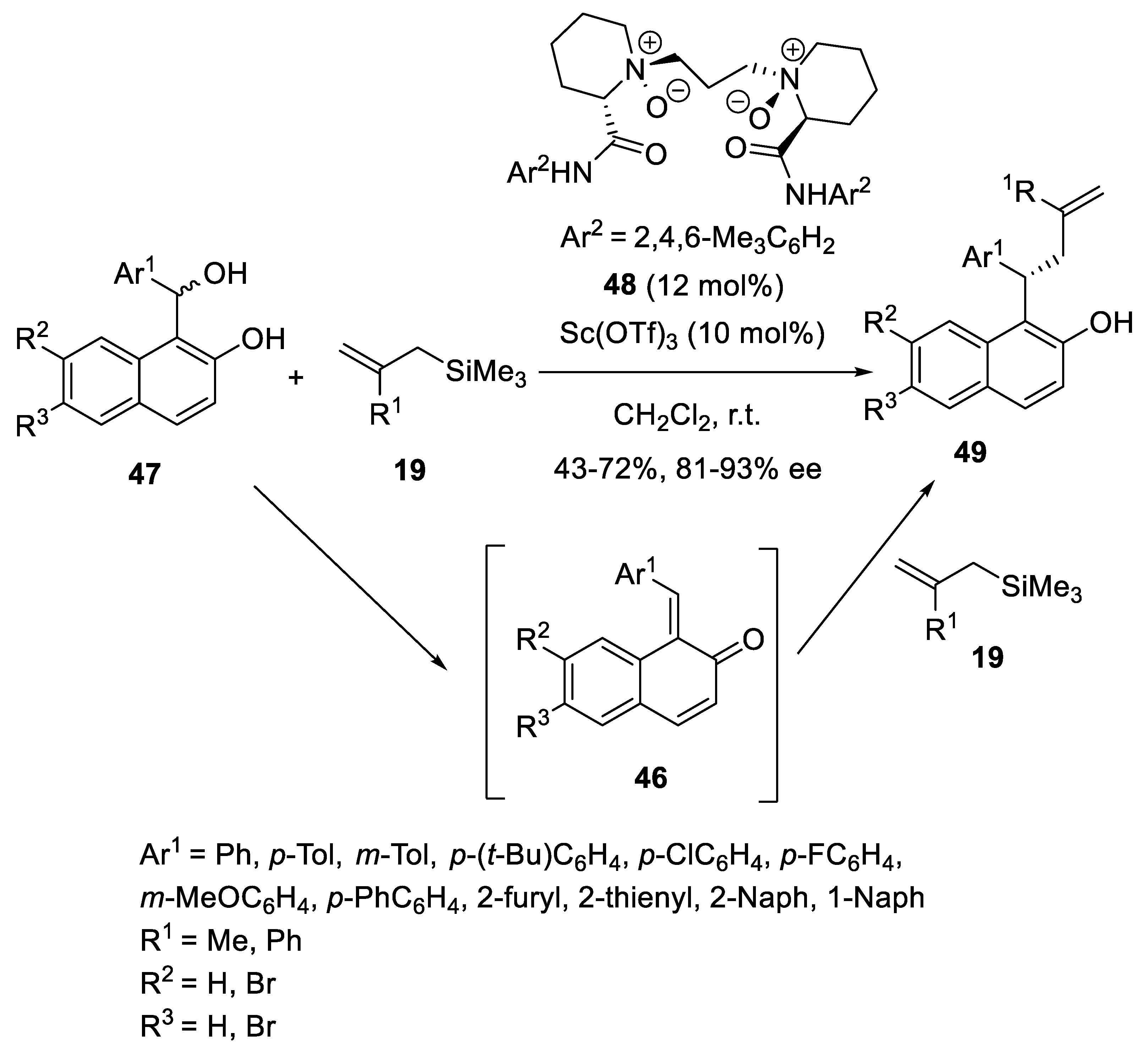

3.1. Scandium Catalysts in Enantioselective Sakurai Reactions of Ketones

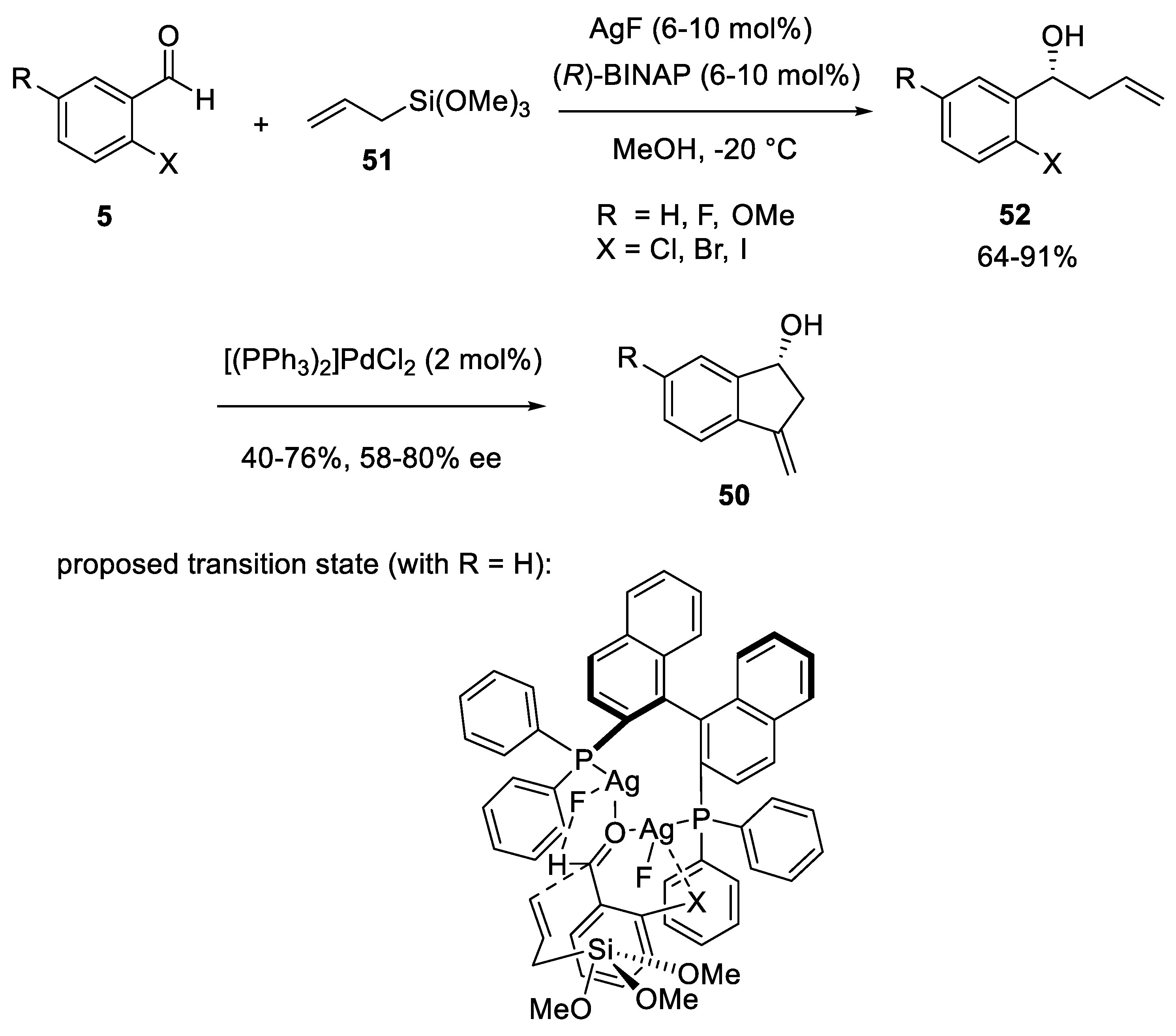

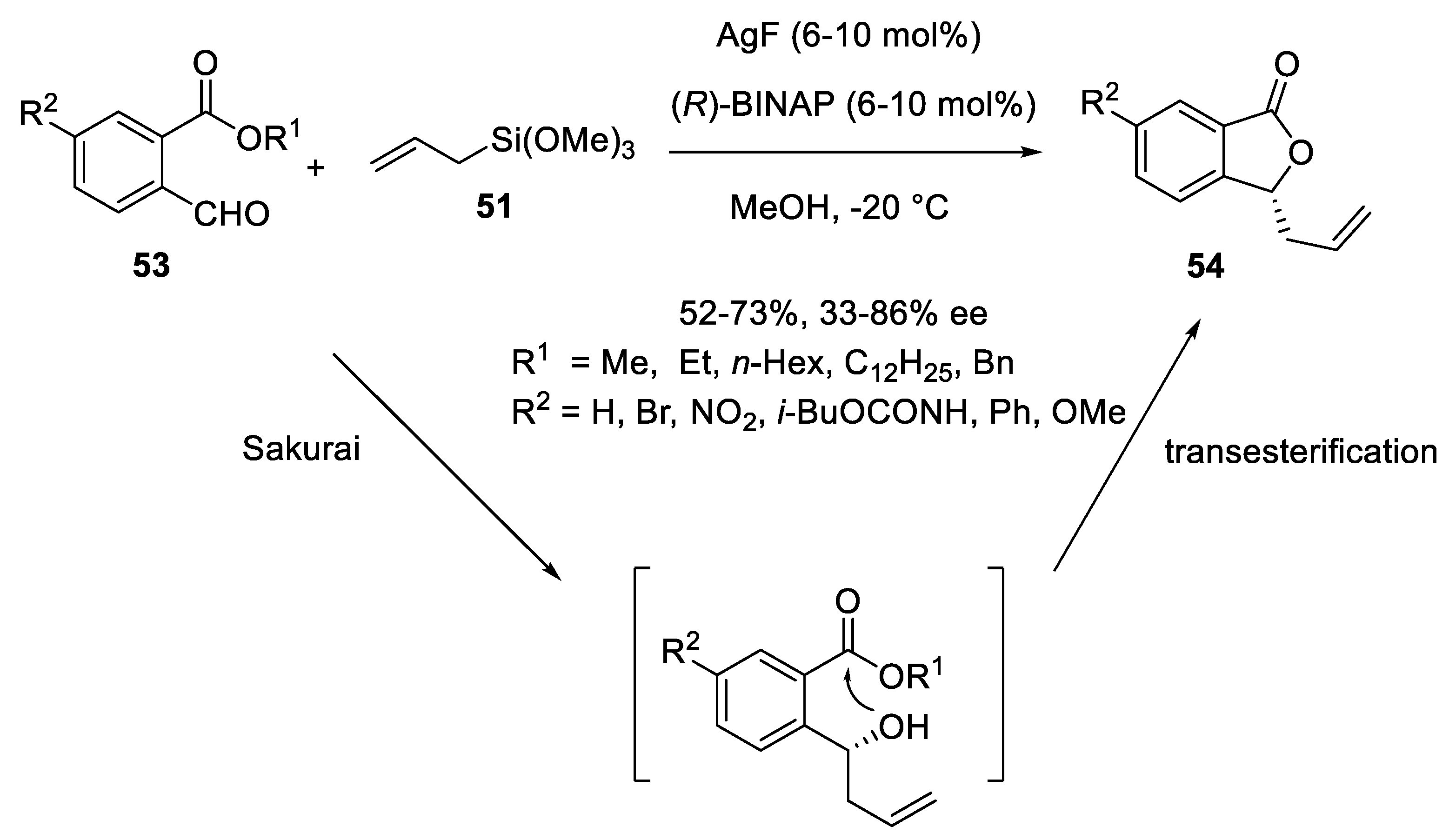

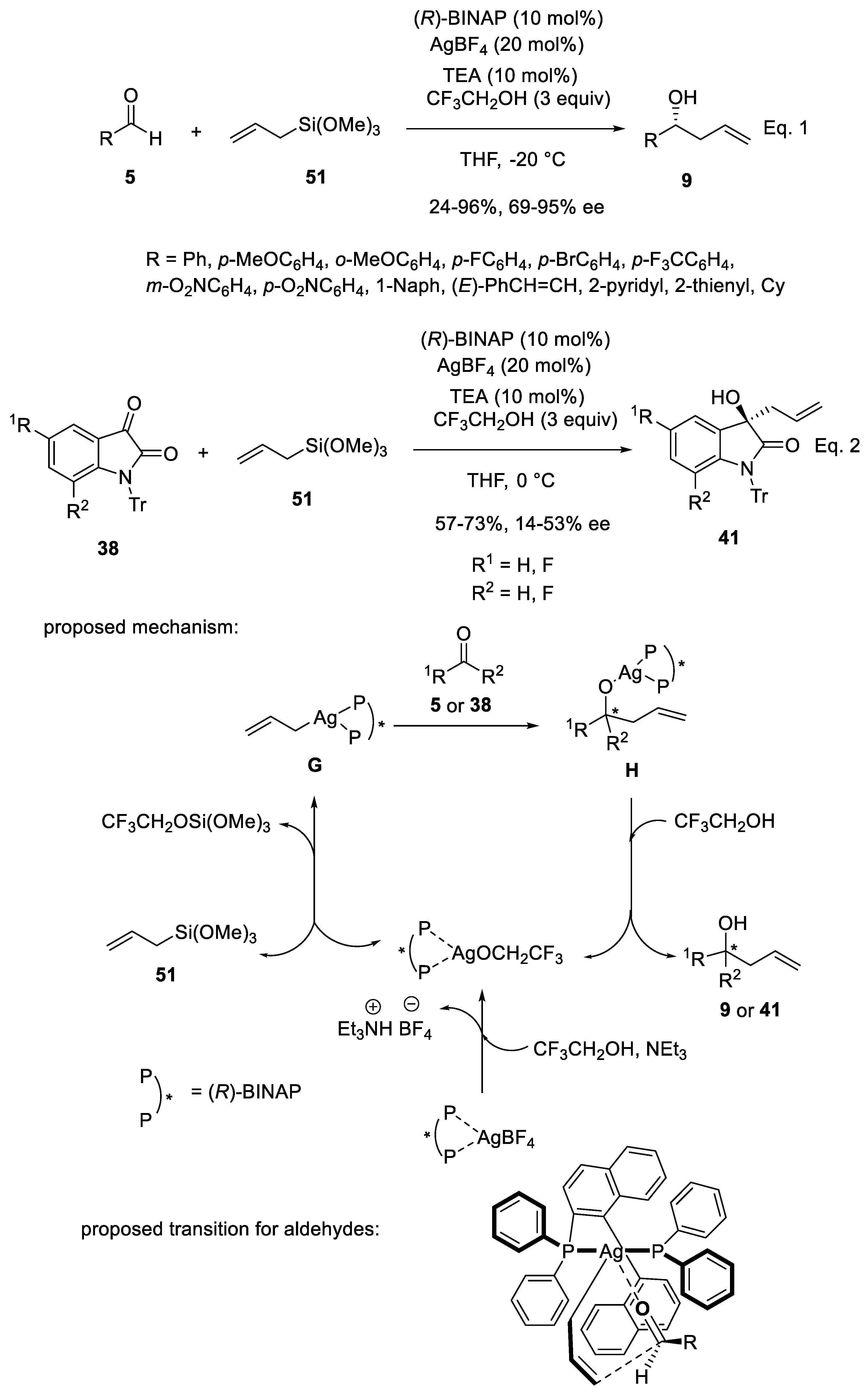

3.2. Silver Catalysts in Enantioselective Sakurai Reactions of Aldehydes and Isatins

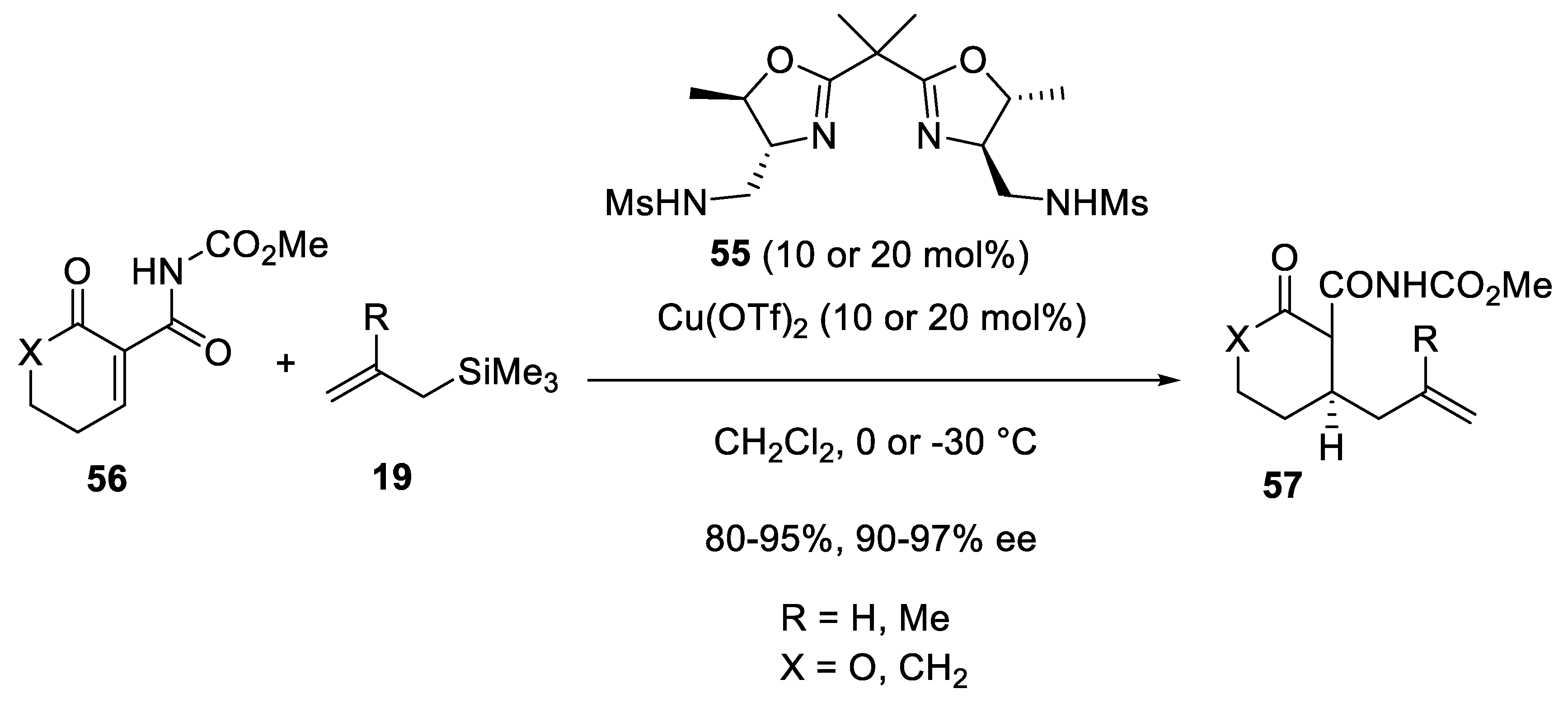

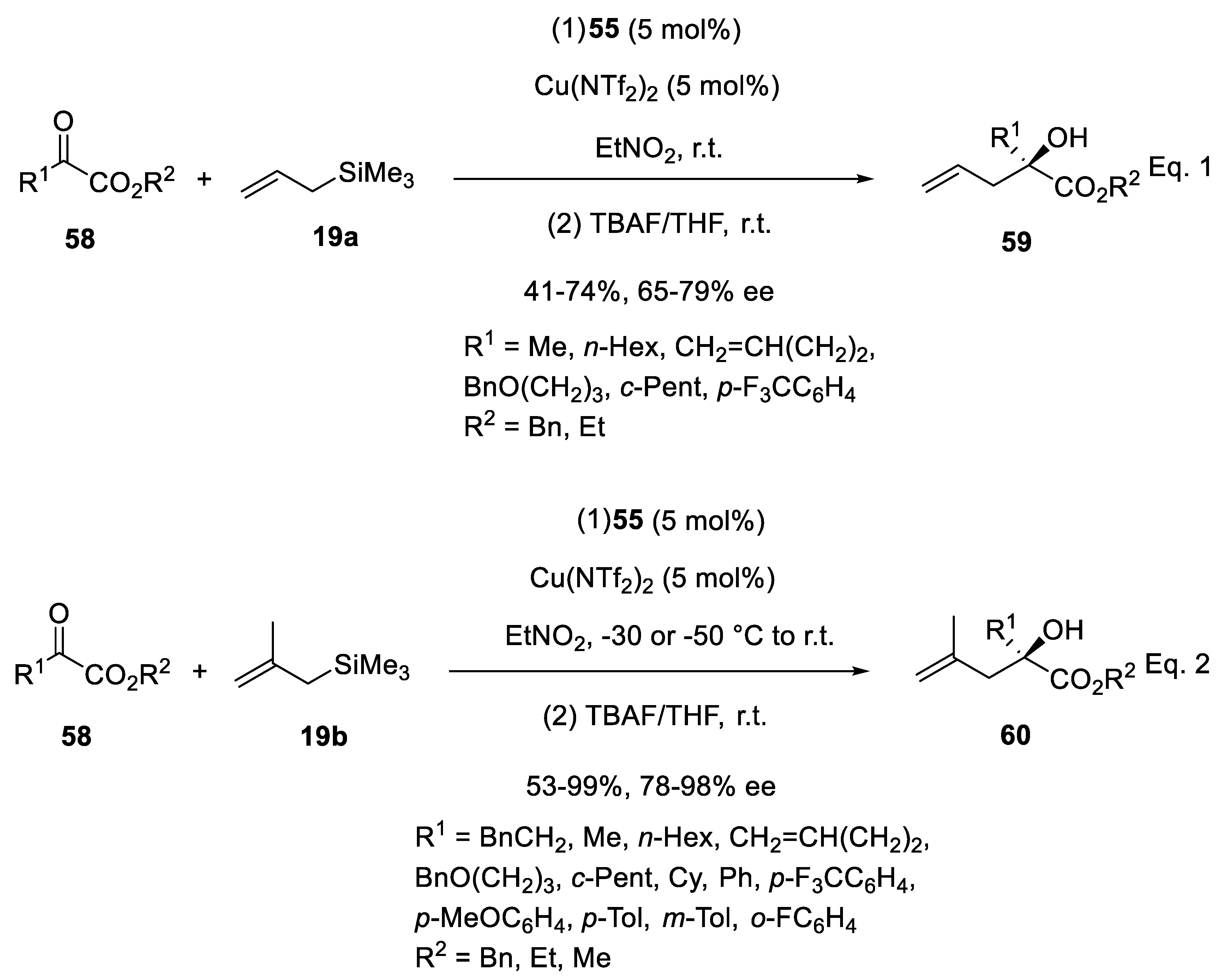

3.3. Copper Catalysts in Enantioselective Sakurai Reactions of Ketones

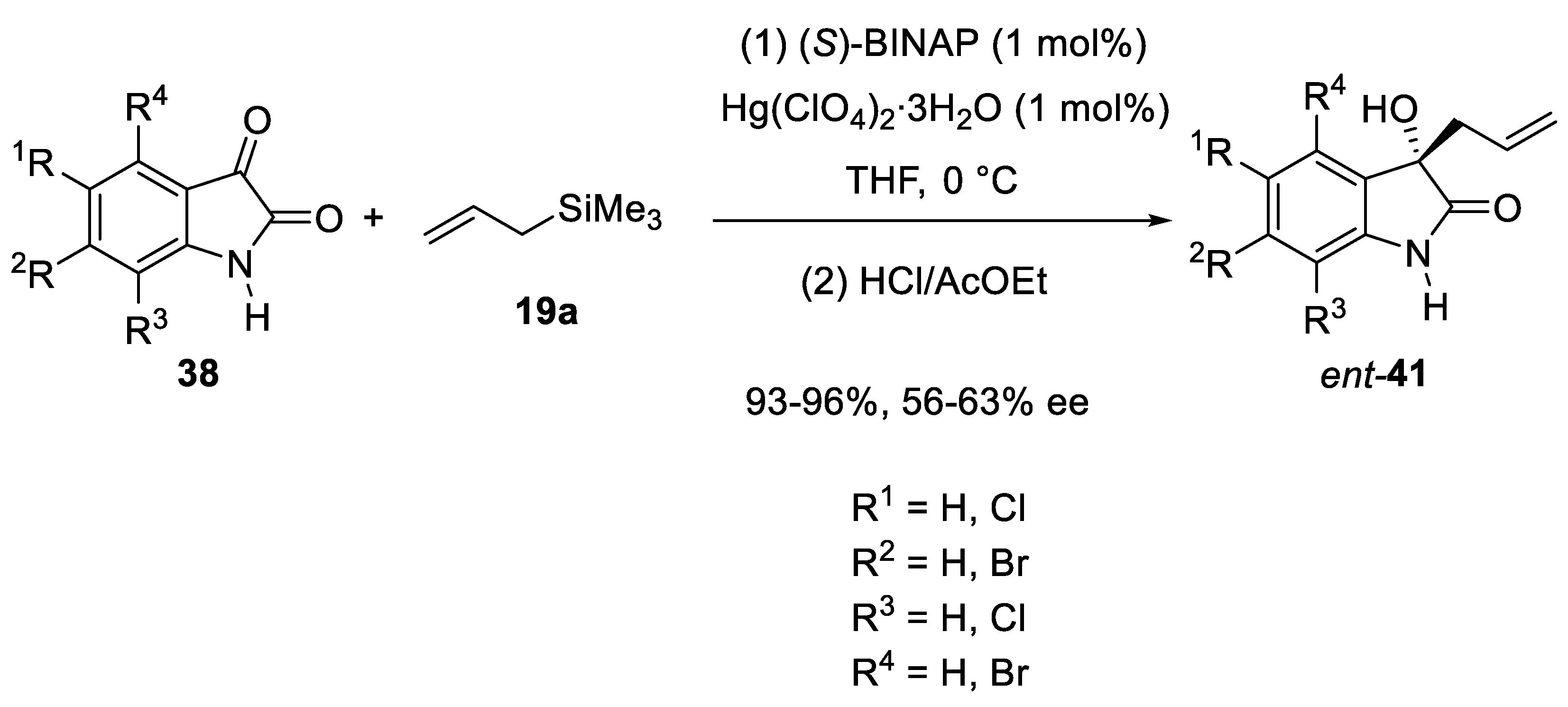

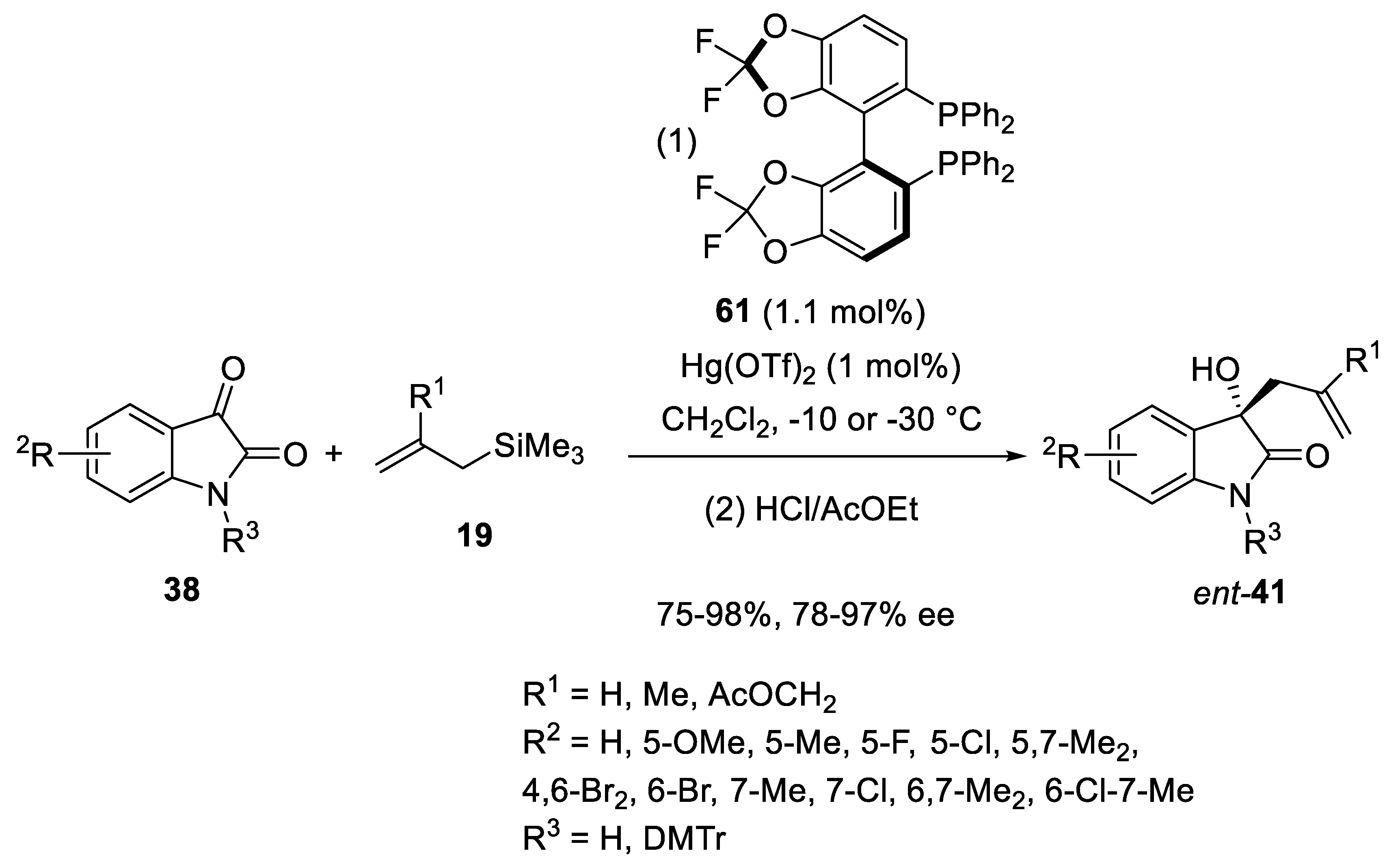

3.4. Mercury Catalysts in Enantioselective Sakurai Reactions of Isatins

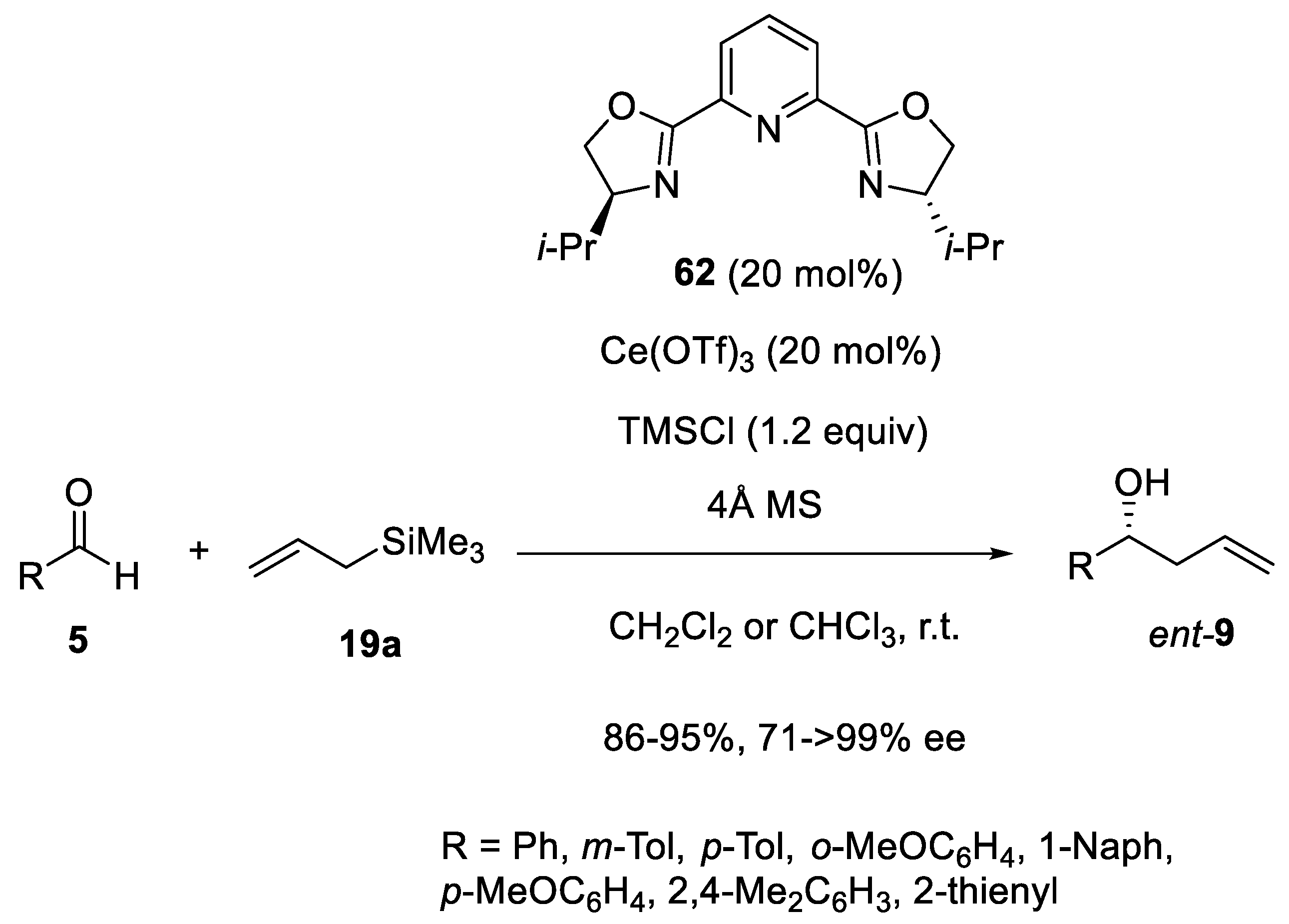

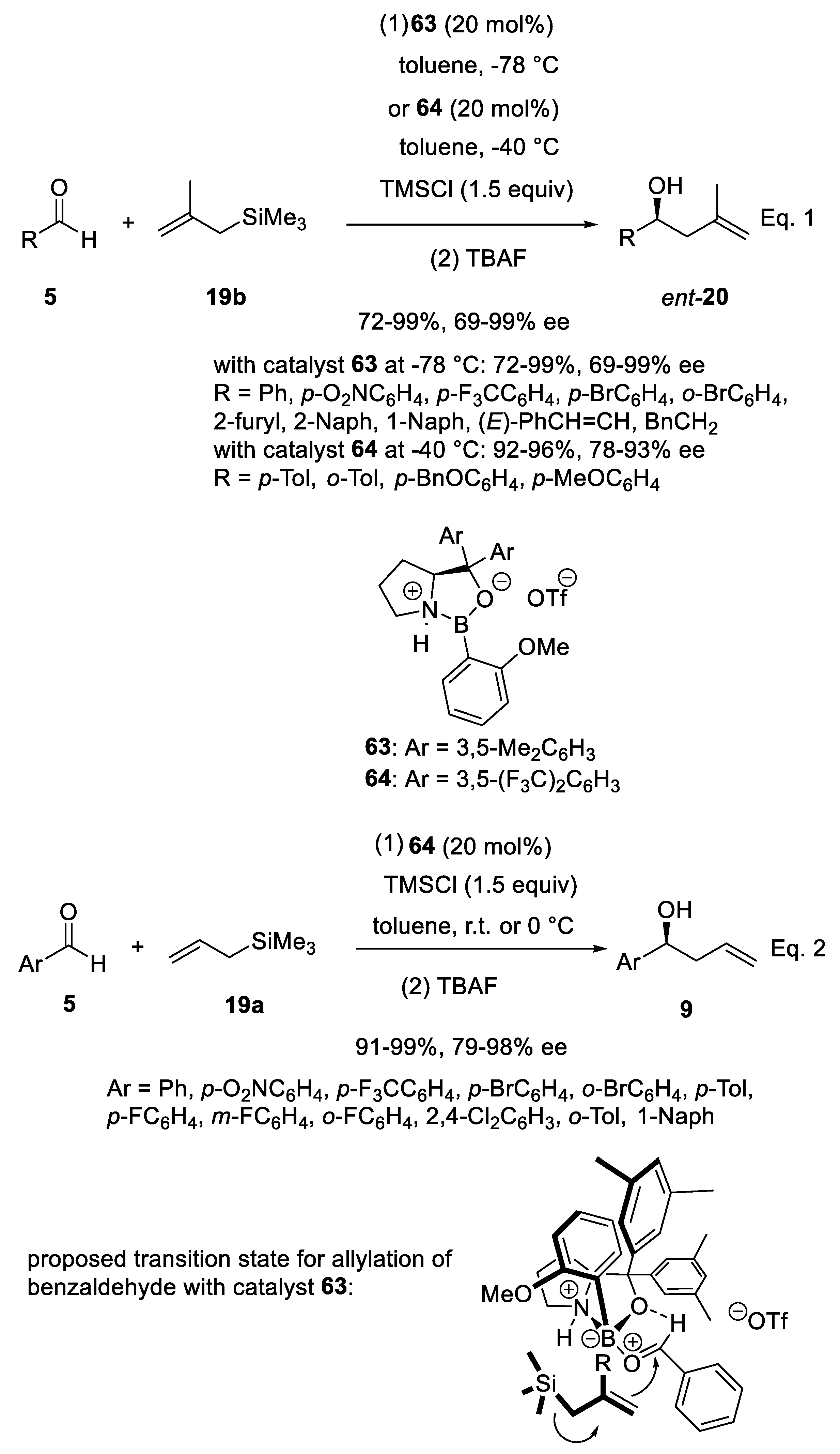

3.5. Other Catalysts in Enantioselective Sakurai Reactions of Aldehydes

4. Enantioselective Multicatalyzed (Aza)-Sakurai Reactions

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Alloc | allyloxycarbonyl |

| Ar | aryl |

| BArF | tetrakis(3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl) borate |

| BINAP | 2,2’-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1’-binaphthyl |

| BINOL | 1,1’-bi-2-naphthol |

| Bn | benzyl |

| Cbz | benzyloxycarbonyl |

| Cy | cyclohexyl |

| DCE | dichloroethane |

| de | diastereomeric excess |

| DIPEA | diisopropylethylamine |

| DMF | dimethylformamide |

| DMTr | di(p-methoxyphenyl)phenylmethyl |

| ee | enantiomeric excess |

| FMOC | 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl |

| Hept | heptyl |

| Hex | hexyl |

| LED | light emitting diode |

| Mes | mesityl |

| Ms | mesyl |

| MS | molecular sieves |

| MTBE | methyl tert-butyl ether |

| Naph | naphthyl |

| Pent | pentyl |

| pin | pinacolato |

| PMB | para-methoxybenzyl |

| r.t. | room temperature |

| SET | single electron transfer |

| TBAF | tetra-n-butylammonium fluoride |

| TBDPS | tert-butyldiphenylsilyl |

| TEA | trimethylamine |

| TES | triethylsilyl |

| Tf | trifluoromethanesulfonyl |

| THF | tetrahydrofuran |

| TMS | trimethylsilyl |

| Tol | tolyl |

References

- Hosomi, A.; Sakurai, H. Syntheses of γ,δ-unsaturated alcohols from allylsilanes and carbonyl compounds in the presence of titanium tetrachloride. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 17, 1295–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Asao, N. Selective Reactions Using Allylic Metals. Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 2207–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bols, M.; Skrydtrup, T. Silicon-Tethered Reactions. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 1253–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langkopf, E.; Schinzer, D. Uses of Silicon-Containing Compounds in the Synthesis of Natural Products. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 1375–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denmark, S.E.; Almstead, N.G. Modern Carbonyl Chemistry; Otera, J., Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2000; pp. 299–401. [Google Scholar]

- Dilman, A.D.; Ioffe, S. Carbon–Carbon Bond Forming Reactions Mediated by Silicon Lewis Acids. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 733–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, I.; Langley, J.A. The Mechanism of the Protodesilylation of Allylsilanes and Vinylsilanes. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1981, 1, 1421–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lade, J.J.; Pardeshi, S.D.; Vadagonkar, K.S.; Murugan, K.; Chaskar, A.C. The Remarkable Journey of Catalysts from Stoichiometric to Catalytic Quantity for Allyltrimethylsilane Inspired Allylation of Acetals, Ketals, Aldehydes and Ketones. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 8011–8033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, T.; Hoffmann, R.W. Enantioselective Synthesis of Homoallyl Alcohols via Chiral Allylboronic Esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1978, 17, 768–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H. Use of the Hosomi-Sakurai Allylation in Natural Product Total Synthesis. Tetrahedron 2020, 76, 131356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, I.; Trost, B.M. (Eds.) Comprehensive Organic Synthesis; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1991; pp. 563–593. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, M.A. Silicon in Organic, and Polymer Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, J.; Krische, M.J. Asymmetric Synthesis: More Methods and Applications; Christmann, M., Bräse, S., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2012; pp. 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Yus, M.; Gonzalez-Gomez, J.C.; Foubelo, F. Diastereoselective Allylation of Carbonyl Compounds and Imines: Application to the Synthesis of Natural Products. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5595–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yus, M.; Gonzalez-Gomez, J.C.; Foubelo, F. Catalytic Enantioselective Allylation of Carbonyl Compounds and Imines. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 7774–7854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denmark, S.E.; Fu, J. Catalytic Enantioselective Addition of Allylic Organometallic Reagents to Aldehydes and Ketones. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 2763–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino, P.; Tejero, T.; Delso, J.I.; Mannucci, V. Stereoselective Allylation Reactions of Imines and Related Compounds. Curr. Org. Synth. 2005, 2, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevich, K.S.; Cook, M.J. The Hosomi-Sakurai Allylation in Carbocyclization Reactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2023, 121, 154415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akwensi, J.; Kumah, R.T.; Osei-Safo, D.; Amewu, R.K. Application of Hosomi-Sakurai Allylation Reaction in Total Synthesis of Biologically Active Natural Products. Front. Chem. 2025, 13, 1527387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Nishio, K. Facile and Highly Stereoselective Allylation of Aldehydes using Allyltrichlorosilanes in DMF. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 3453–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denmark, S.E.; Coe, D.M.; Pratt, N.E.; Griedel, B.D. Asymmetric Allylation of Aldehydes with Chiral Lewis Bases. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 6161–6163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, M.; Saito, M.; Shiro, M.; Hashimoto, S. Enantioselective Ring Opening of Meso-Epoxides with Tetrachlorosilane Catalyzed by Chiral Bipyridine N,N′-Dioxide Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 6419–6420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkov, A.V.; Bell, M.; Castelluzzo, F.; Kočovský, P. METHOX: A New Pyridine N-Oxide Organocatalyst for the Asymmetric Allylation of Aldehydes with Allyltrichlorosilanes. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 3219–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkov, A.V.; Barlog, M.; Jewkes, Y.; Mikusek, J.; Kočovský, P. Enantioselective Allylation of α,β-Unsaturated Aldehydes with Allyltrichlorosilane Catalyzed by METHOX. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 4800–4804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkov, A.V.; Kysilka, O.; Edgar, M.; Kadlcikova, A.; Kotora, M.; Kočovský, P. A Novel Bifunctional Allyldisilane as a Triple Allylation Reagent in the Stereoselective Synthesis of Trisubstituted Tetrahydrofurans. Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 7162–7166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veitía, M.S.-I.; Joudat, M.; Wagner, M.; Falguières, A.; Guy, A.; Ferroud, C. Ready Available Chiral Azapyridinomacrocycles N-Oxides; First Results as Lewis Base Catalysts in Asymmetric Allylation of p-Nitrobenzaldehyde. Heterocycles 2011, 83, 2011–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naicker, T.; Arvidsson, P.I.; Kruger, H.G.; Maguire, G.E.M.; Govender, T. Tetrahydroisoquinoline-Based N-Oxides as Chiral Organocatalysts for the Asymmetric Allylation of Aldehydes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2011, 6923–6932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Shen, L.; Ren, J.; Zhu, H.J. Chiral Biscarboline N,N’-Dioxide Derivatives: Highly Enantioselective Addition of Allyltrichlorosilane to Aldehydes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkov, A.V.; Stoncius, S.; Bell, M.; Castelluzzo, F.; Ramirez-Lopez, P.; Lada Biedermannova, L.; Langer, V.; Rulisek, L.; Kočovský, P. Mechanistic Dichotomy in the Asymmetric Allylation of Aldehydes with Allyltrichlorosilanes Catalyzed by Chiral Pyridine N-Oxides. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 9167–9185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reep, C.; Morgante, P.; Peverati, R.; Takenaka, N. Axial-Chiral Biisoquinoline N,N′-Dioxides Bearing Polar Aromatic C-H Bonds as Catalysts in Sakurai-Hosomi-Denmark Allylation. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 5757–5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.R.; Bell, M.; Dunne, K.S.; Kelly, B.; Stevenson, P.J.; Malone, J.F.; Allen, C.C.R. Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of a Mixed Phosphine–Phosphine Oxide Catalyst and its Application to Asymmetric Allylation of Aldehydes and Hydrogenation of Alkenes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 1388–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, G.; Vignes, C.; De Piano, F.; Bosco, A.; Massa, A. Chiral Sulfoxides in the Enantioselective Allylation of Aldehydes with Allyltrichlorosilane: A Kinetic Study. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 9650–9659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

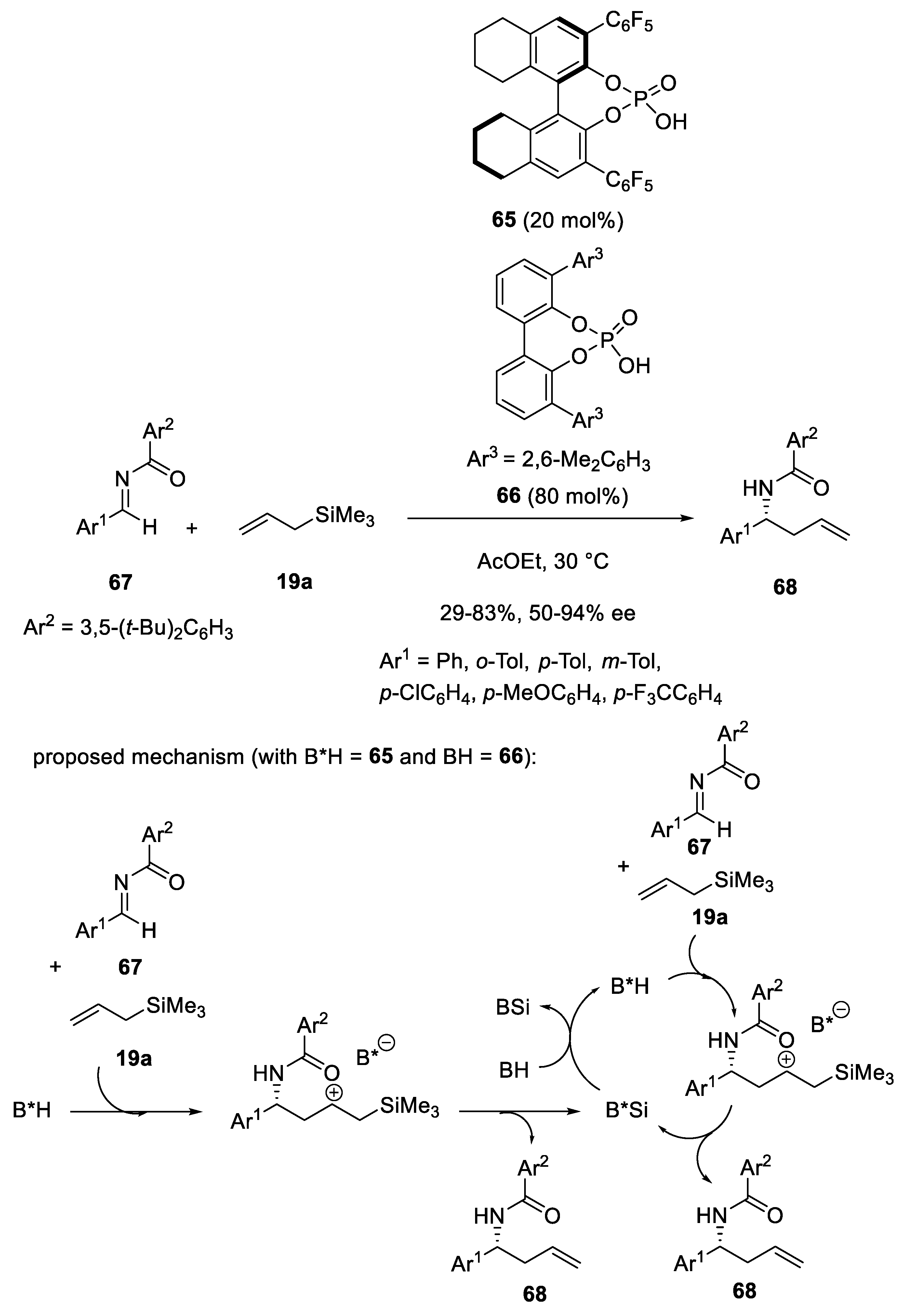

- Mahlau, M.; Garcia-Garcia, P.; List, B. Asymmetric Counteranion-Directed Catalytic Hosomi-Sakurai Reaction. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 16283–16287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, M.; Yamamoto, H. Chiral Brønsted Acid as a True Catalyst: Asymmetric Mukaiyama Aldol and Hosomi–Sakurai Allylation Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 7091–7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreyer, L.; Properzi, R.; List, B. IDPi Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 12761–12777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaib, P.S.J.; Schreyer, L.; Lee, S.; Properzi, R.; List, B. Extremely Active Organocatalysts Enable a Highly Enantioselective Addition of Allyltrimethylsilane to Aldehydes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 13200–13203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, S.; List, B. Catalytic Asymmetric Three-Component Synthesis of Homoallylic Amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2573–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.; Schindler, C.S.; Jacobsen, E.N. Enantioselective Aza-Sakurai Cyclizations: Dual Role of Thiourea as H-Bond Donor and Lewis Base. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 14848–14851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellissier, H. Recent Developments in Enantioselective Scandium–Catalyzed Transformations. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 313, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanhan, N.V.; Tang, Y.C.; Tran, N.T.; Franz, A.K. Scandium(III)-Catalyzed Enantioselective Allylation of Isatins Using Allylsilanes. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 2218–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galliford, C.V.; Scheidt, K.A. Pyrrolidinyl-Spirooxindole Natural Products as Inspirations for the Development of Potential Therapeutic Agents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 8748–8758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietze, L.F. Domino Reactions in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietze, L.F.; Brasche, G.; Gericke, K. Domino Reactions in Organic Synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Enders, D.; Grondal, C.; Hüttl, M.R.M. Asymmetric Organocatalytic Domino Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 1570–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellissier, H. Recent Developments in Asymmetric Organocatalytic Domino Reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 237–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellissier, H. Stereocontrolled Domino Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 442–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tietze, L.F. Domino Reactions—Concepts for Efficient Organic Synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pellissier, H. Recent Developments in Enantioselective Metal-Catalyzed Domino Reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016, 358, 2194–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellissier, H. Recent Developments in Enantioselective Metal-Catalyzed Domino Reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2019, 361, 1733–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellissier, H. Recent Developments in Enantioselective Domino Reactions. Part A: Noble Metal Catalysts. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2023, 365, 620–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellissier, H. Recent Developments in Enantioselective Domino Reactions. Part B: First Row Metal Catalysts. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2023, 365, 768–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanhan, N.V.; Ball-Jones, N.R.; Tran, N.T.; Franz, A.K. Catalytic Asymmetric [3+2] Annulation of Allylsilanes with Isatins: Synthesis of Spirooxindoles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 989–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball-Jones, N.R.; Badillo, J.J.; Tran, N.T.; Franz, A.K. Catalytic Enantioselective Carboannulation with Allylsilanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 9462–9465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, C. Allylsilane Reagent-Controlled Divergent Asymmetric Catalytic Reactions of 2-Naphthoquinone-1-methide. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 14173–14180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabdolbaghi, R.; Dudding, T. A Catalytic Asymmetric Approach to C1-Chiral 3-Methylene-Indan-1-Ols. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 1988–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabdolbaghi, R.; Dudding, T. A synthetic Route to Chiral C(3)-Functionalized Phthalides via a Ag(I)-Catalyzed Allylation/Transesterification Sequence. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 3287–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, A.; Yang, N.; Bamba, K. Asymmetric Allylation of Carbonyl Compounds Catalyzed by a Chiral Phosphine–Silver Complex. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 6614–6618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orimoto, K.; Oyama, H.; Namera, Y.; Niwa, T.; Nakada, M. Catalytic Asymmetric 4 + 2 Cycloadditions and Hosomi–Sakurai Reactions of α-Alkylidene β-Keto Imides. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niwa, Y.; Miyake, M.; Hayakawa, I.; Sakakura, A. Catalytic enantioselective Hosomi–Sakurai Reaction of α-Ketoesters Promoted by Chiral Copper(II) Complexes. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 3923–3926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Z.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, C.-B.; Zhou, J. Hg(ClO4)2·3H2O Catalyzed Sakurai–Hosomi Allylation of Isatins and Isatin Ketoimines Using Allyltrimethylsilane. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 6398–6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.-Y.; Jiang, J.-S.; Zhou, J. A Highly Enantioselective Hg(II)-Catalyzed Sakurai–Hosomi Reaction of Isatins with Allyltrimethylsilanes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 5500–5504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhanga, K.; Du, T. A Ce(OTf)3/PyBox Catalyzed Enantioselective Hosomi–Sakurai Reaction of Aldehydes with Allyltrimethylsilane. New J. Chem. 2015, 77, 7734–7737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Jeong, H.-M.; Venkateswarlu, A.; Ryu, D.H. Highly Enantioselective Allylation Reactions of Aldehydes with Allyltrimethylsilane Catalyzed by a Chiral Oxazaborolidinium Ion. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 5198–5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momiyama, N.; Nishimoto, H.; Terada, M. Chiral Brønsted Acid Catalysis for Enantioselective Hosomi–Sakurai Reaction of Imines with Allyltrimethylsilane. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2126–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

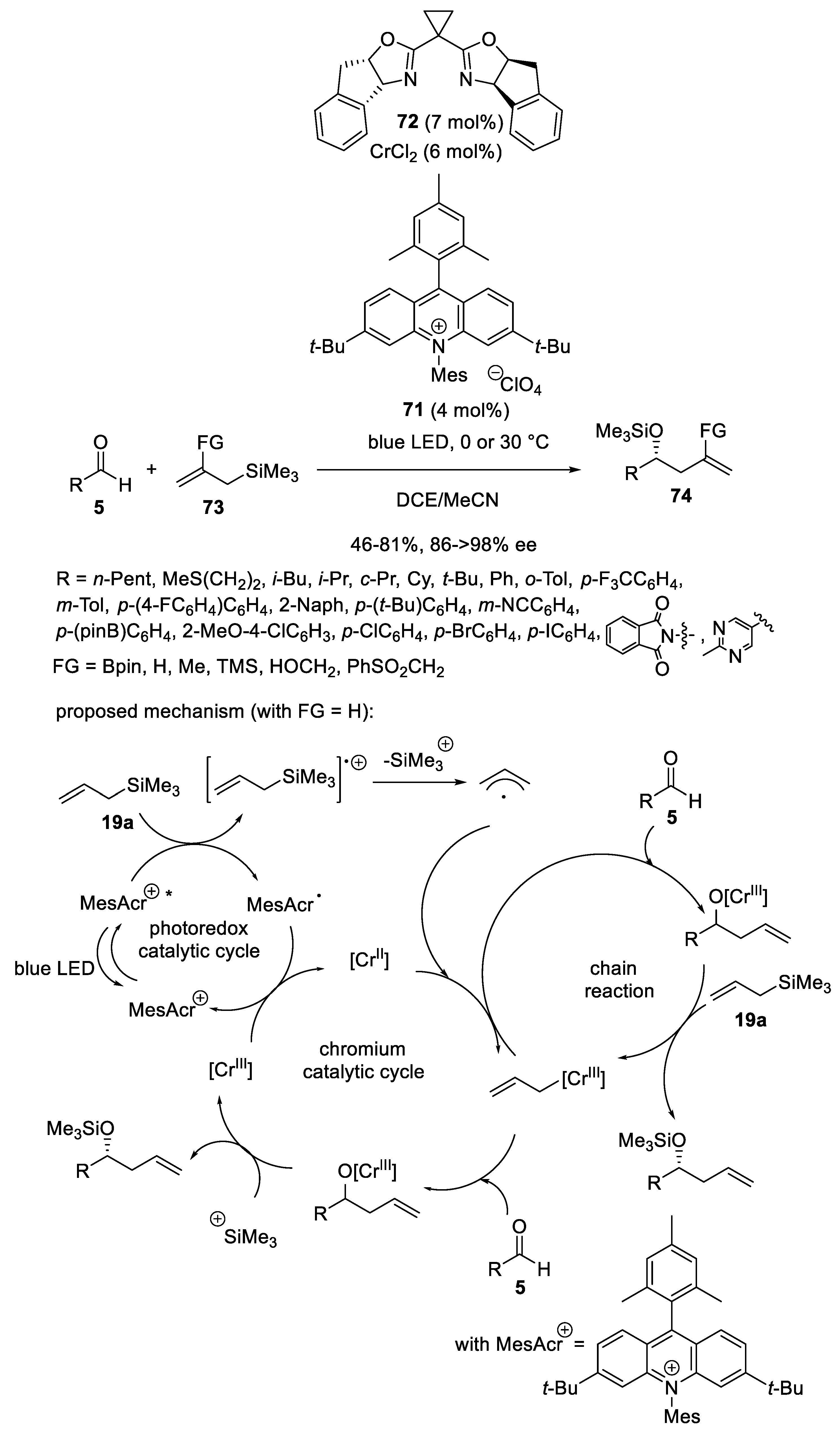

- Schäfers, F.; Dutta, S.; Kleinmans, R.; Mück-Lichtenfeld, C.; Glorius, F. Asymmetric Addition of Allylsilanes to Aldehydes: A Cr/Photoredox Dual Catalytic Approach Complementing the Hosomi–Sakurai Reaction. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 12281–12290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pellissier, H. Recent Developments in the Catalytic Enantioselective Sakurai Reaction. Reactions 2026, 7, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions7010006

Pellissier H. Recent Developments in the Catalytic Enantioselective Sakurai Reaction. Reactions. 2026; 7(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions7010006

Chicago/Turabian StylePellissier, Hélène. 2026. "Recent Developments in the Catalytic Enantioselective Sakurai Reaction" Reactions 7, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions7010006

APA StylePellissier, H. (2026). Recent Developments in the Catalytic Enantioselective Sakurai Reaction. Reactions, 7(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions7010006