Effect of Acetic Acid on Morphology, Structure, Optical Properties, and Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2 Obtained by Sol–Gel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. TiO2 Synthesis

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Rietveld Refinement

2.5. Photocatalytic Activity

3. Results and Discussion

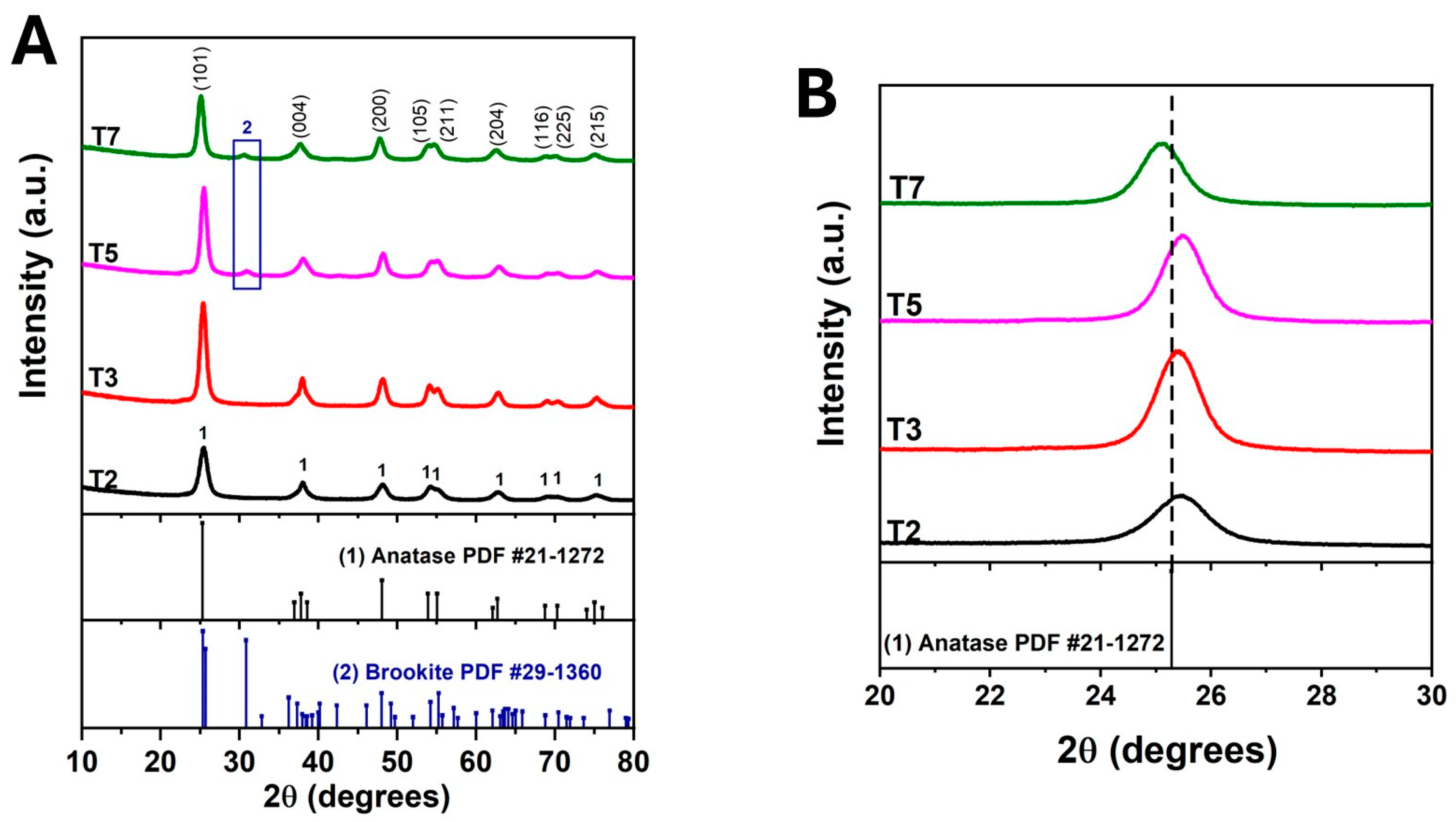

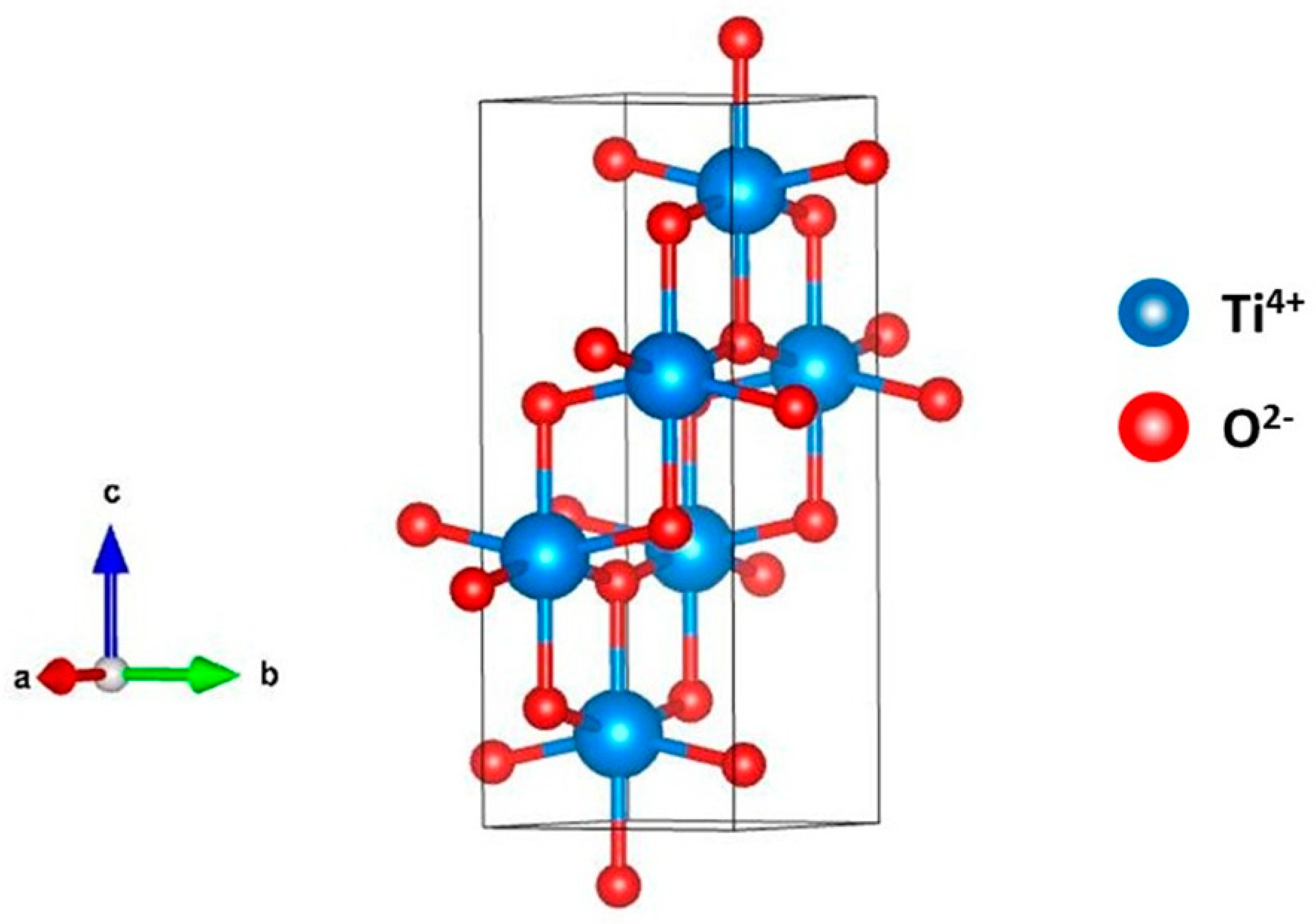

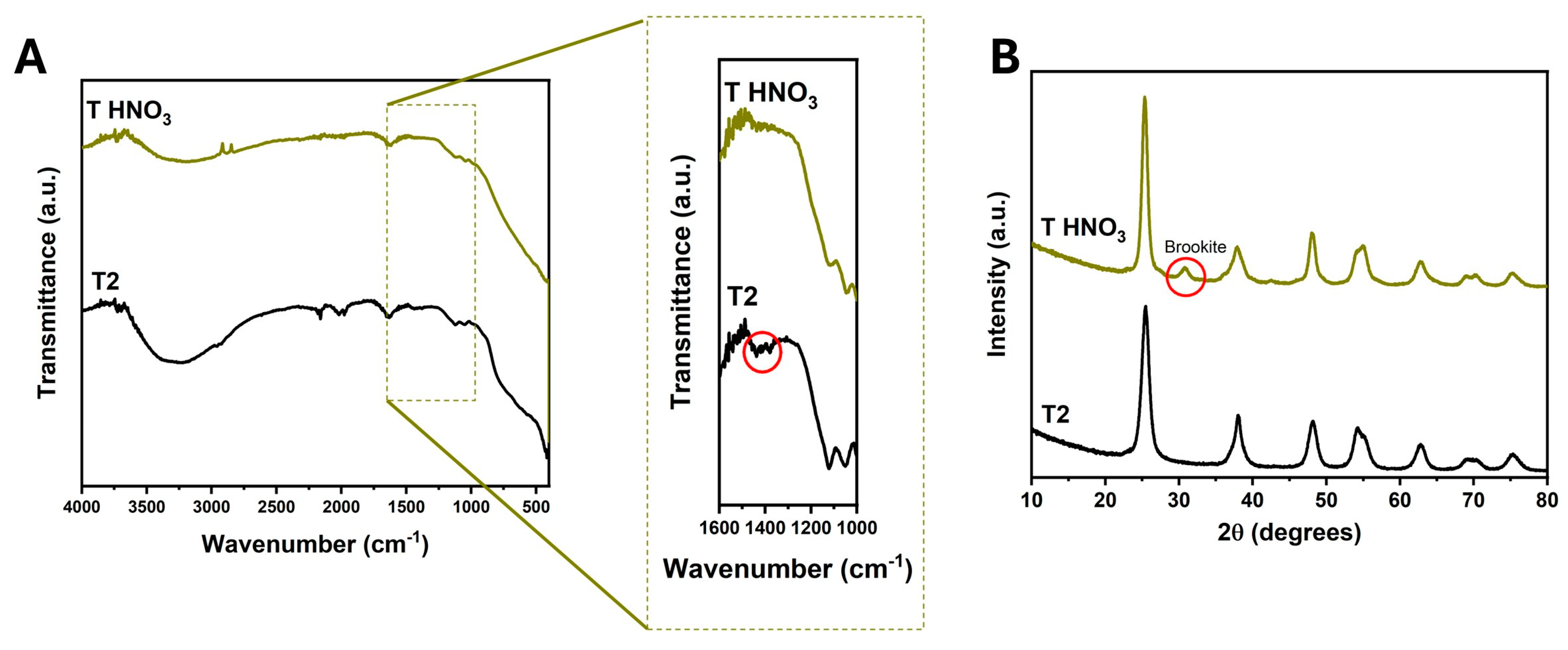

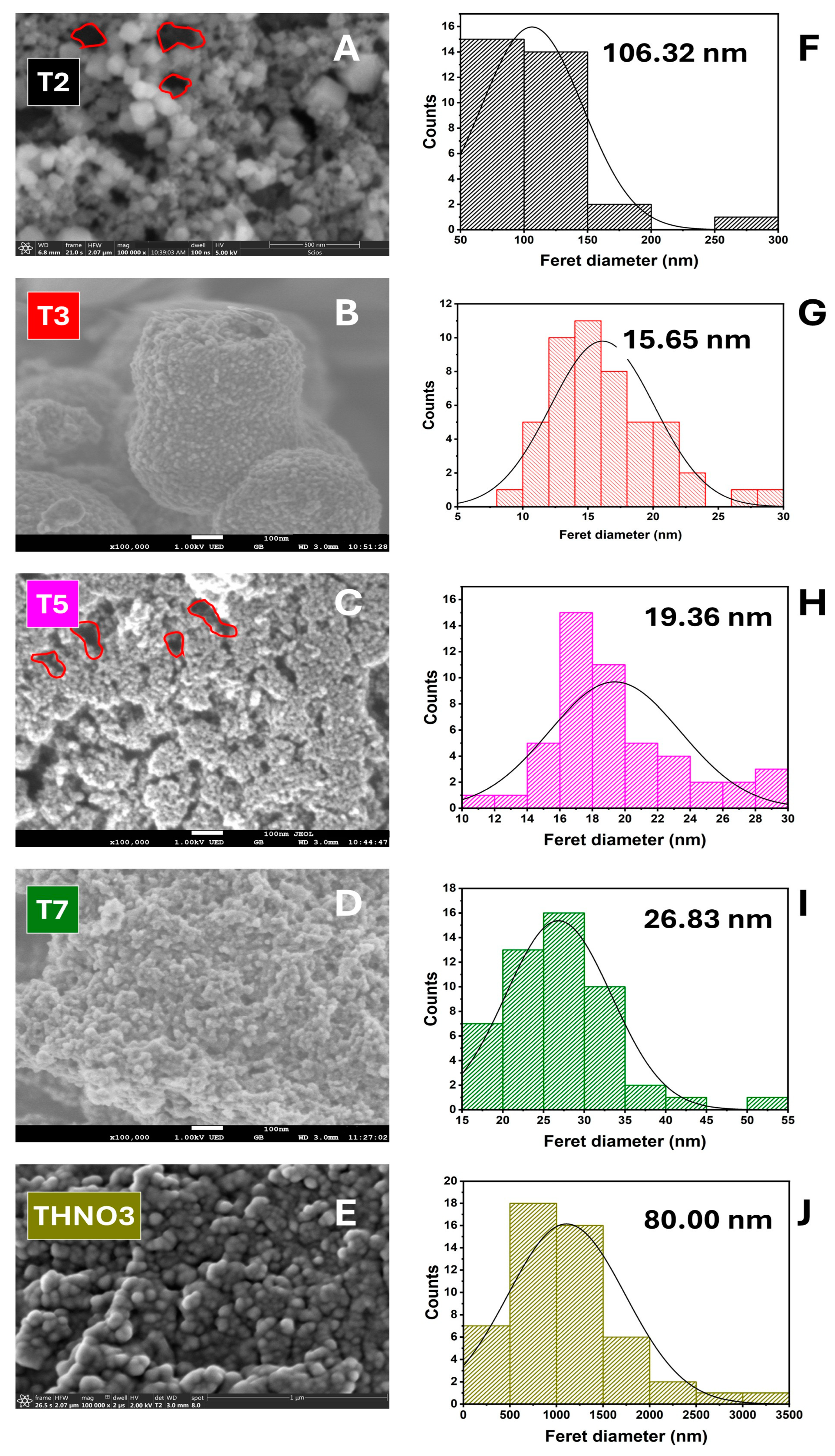

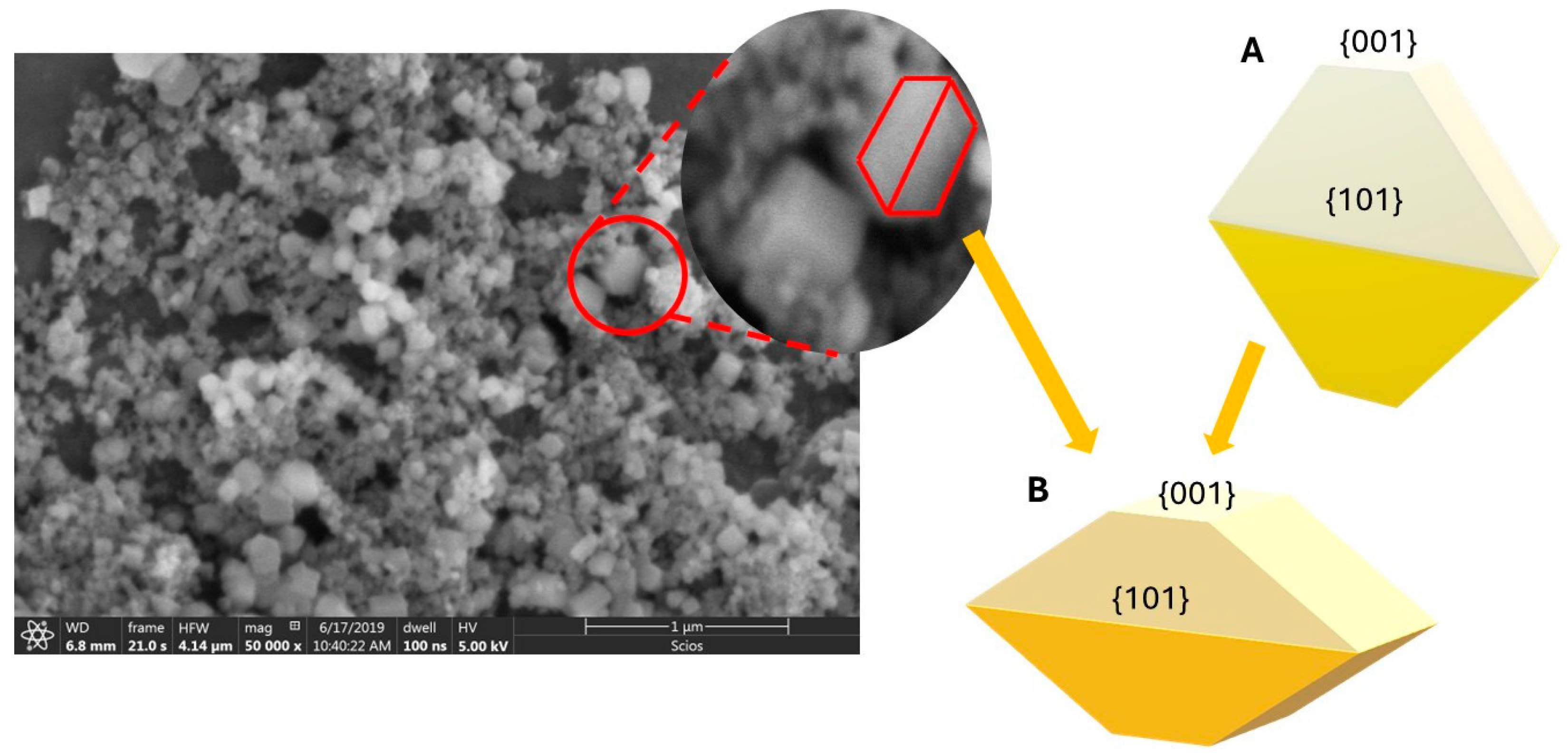

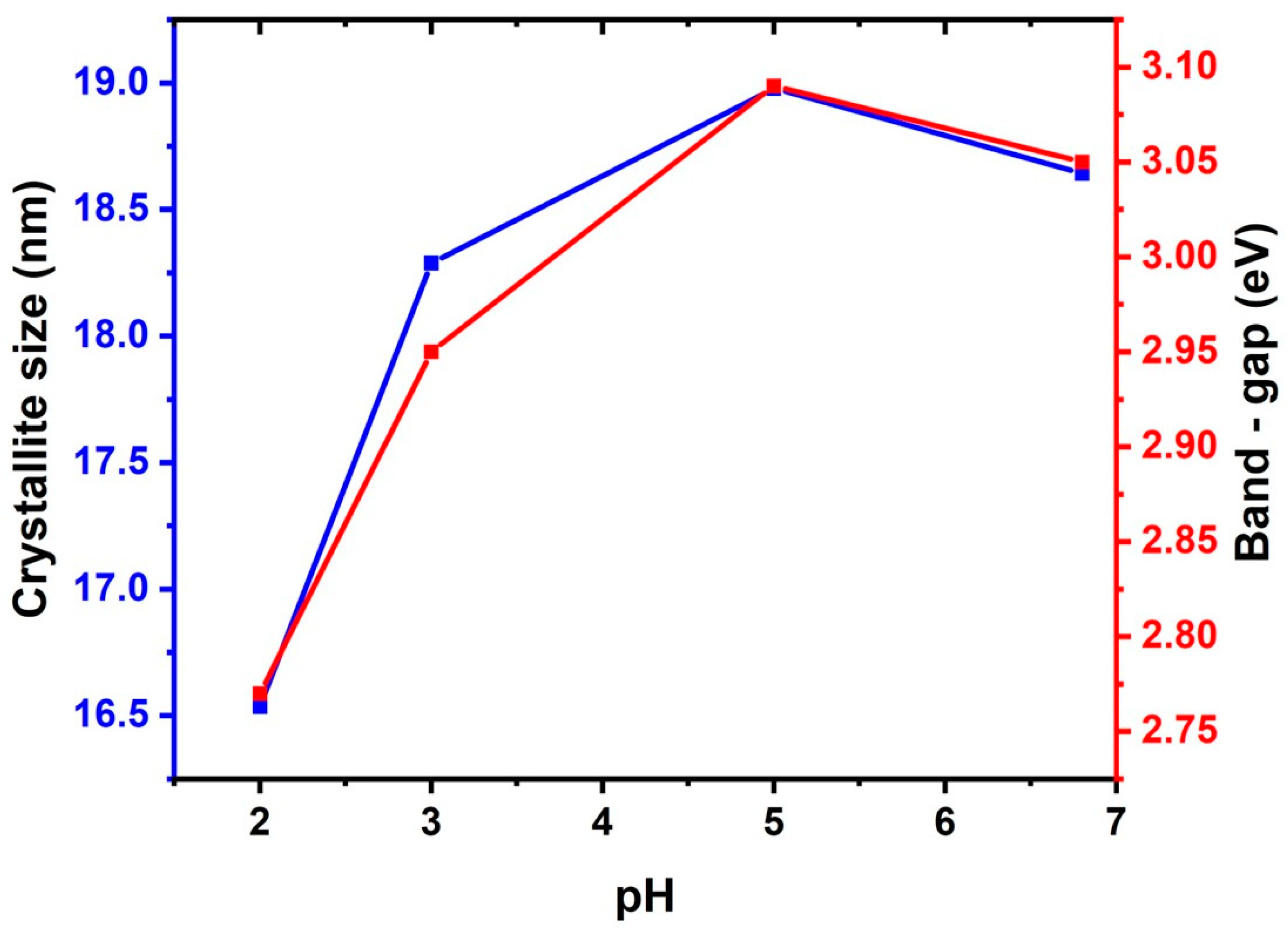

3.1. Effect of Acetic Acid on the Structure and Morphology of TiO2

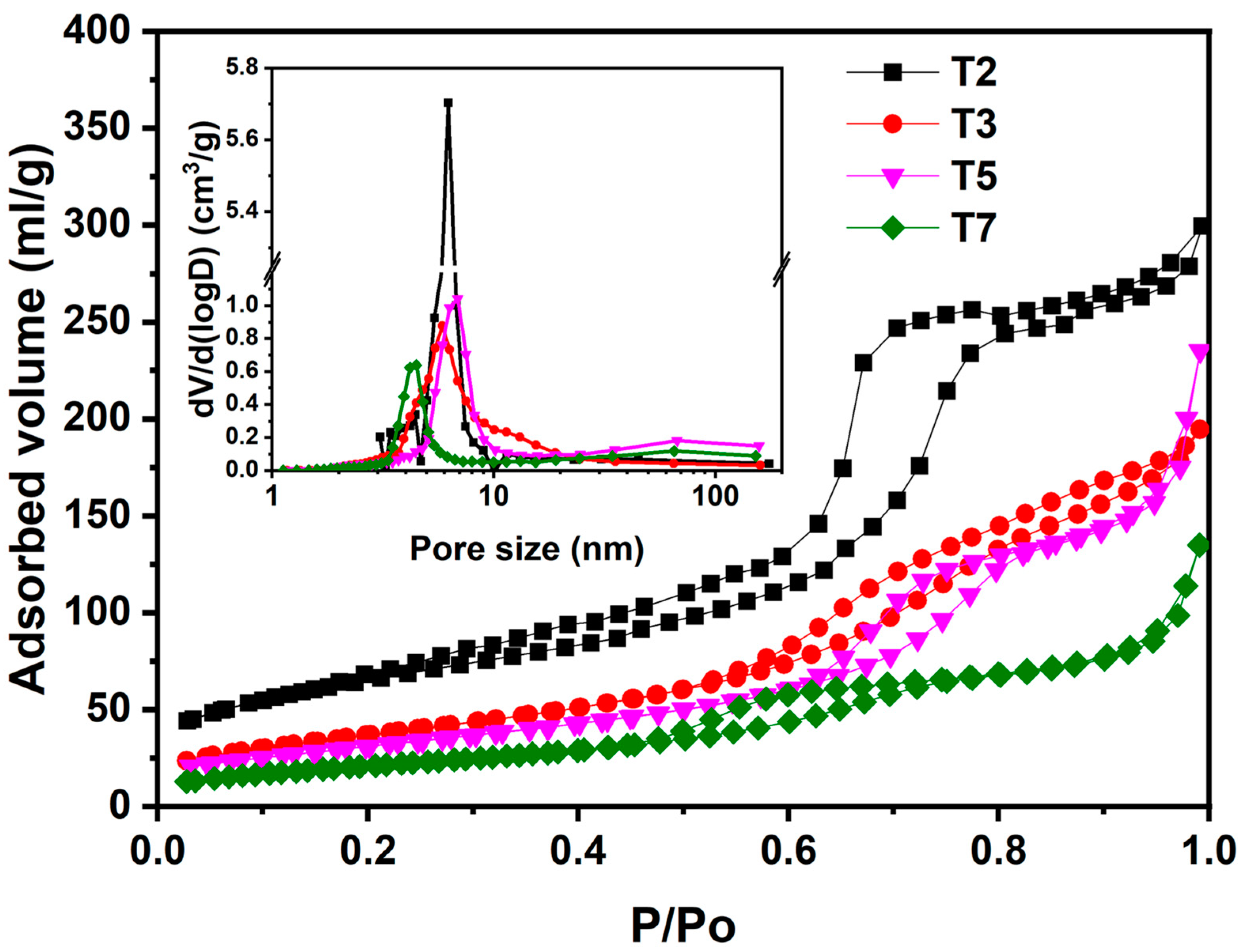

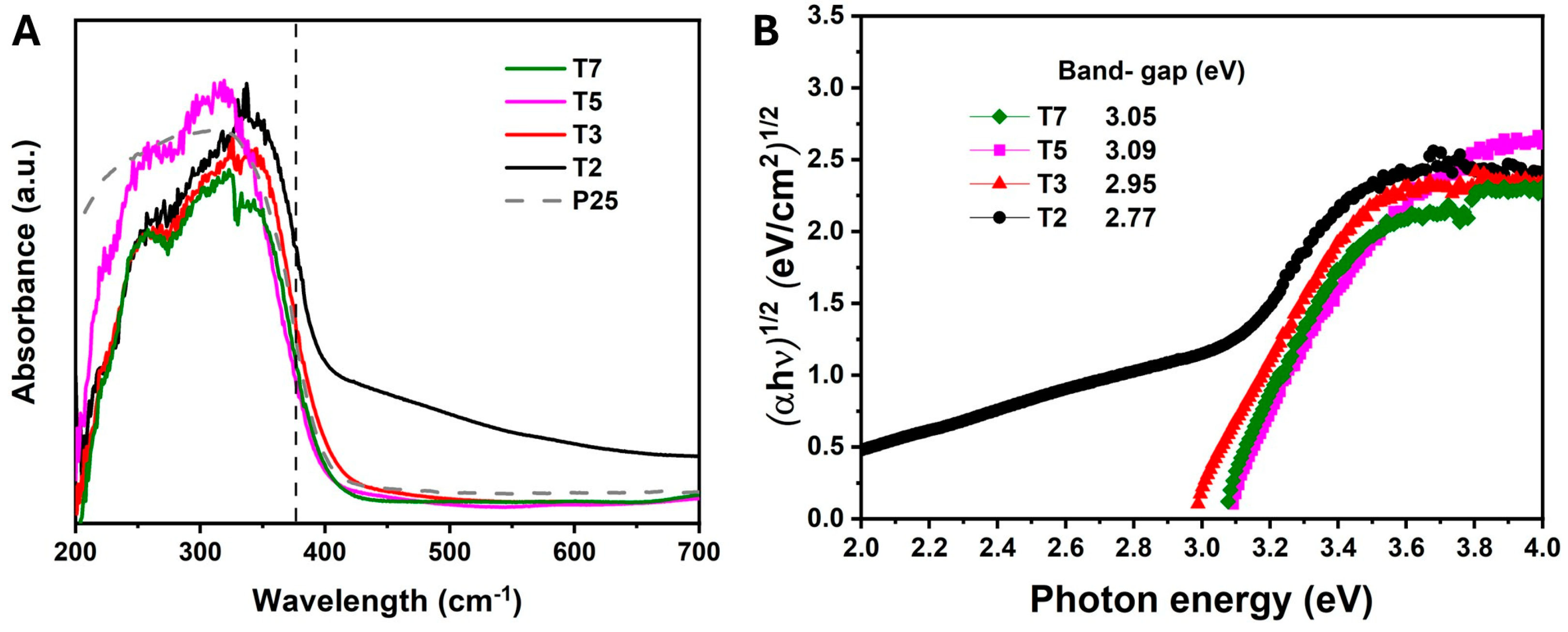

3.2. Effect of Acetic Acid on the Texture and Optical Properties of TiO2

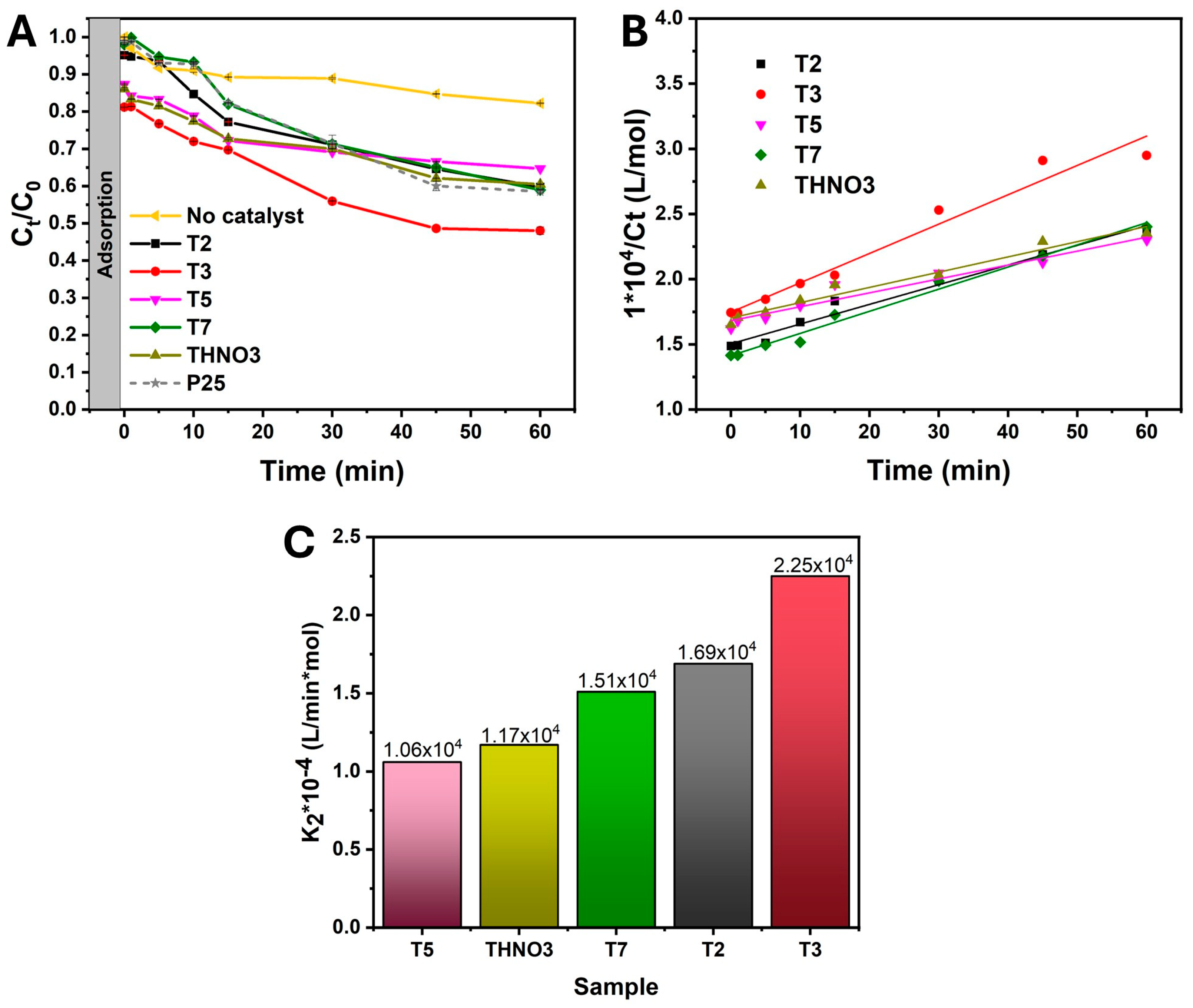

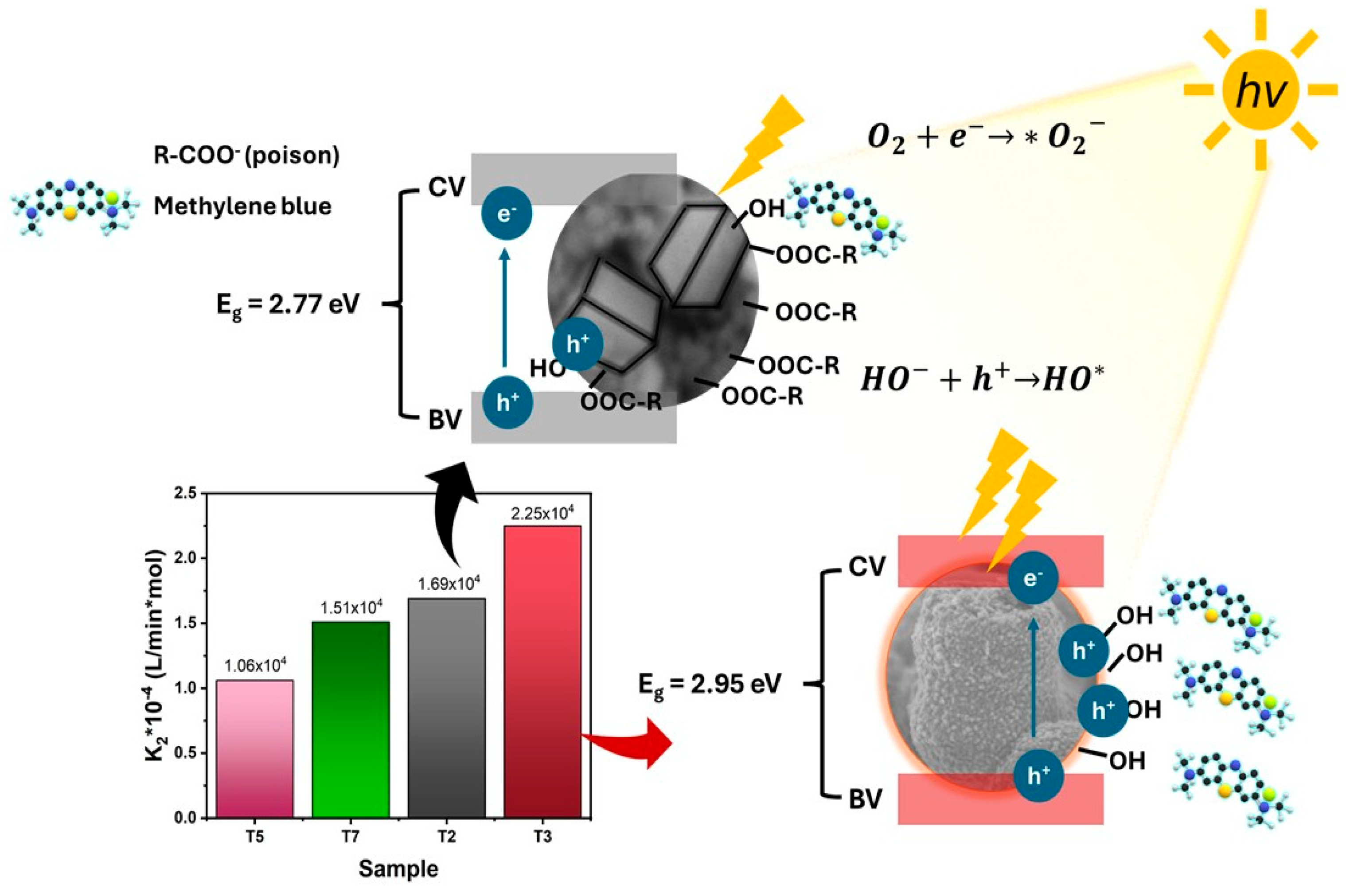

3.3. Effect of Acetic Acid on the Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nam, S.H.; Boo, J.H. Fabrication of moth-eye patterned TiO2 active layers for high energy efficiency and current density of dye-sensitized solar cells. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Tian, Z.; Yao, J. Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell Based on TiO2 Anode Thin Film with Three-Dimensional Web-like Structure. Materials 2022, 15, 5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejazi, S.; Killian, M.S.; Mazare, A.; Mohajernia, S. Single-Atom-Based Catalysts for Photocatalytic Water Splitting. Catalyst 2022, 12, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundarya, T.L.; Jayalakshmi, T.; Alsaiari, M.A.; Jalalah, M.; Abate, A.; Alharthi, F.A.; Ahmad, N.; Nagaraju, G. Ionic Liquid-Aided Synthesis of Anatase TiO2 Nanoparticles: Photocatalytic Water Splitting and Electrochemical Applications. Crystals 2022, 12, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, N.; Chen, P.; Wang, Y.; Li, K.; Huo, S.; Cheng, P.; Peng, P.; Zhang, R.; et al. Photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants using TiO2-based photocatalysts: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 121725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Driel, B.A.; Kooyman, P.J.; van den Berg, K.J.; Schmidt-Ott, A.; Dik, J. A quick assessment of the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 pigments—From lab to conservation studio! Microchem. J. 2016, 126, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.A. A surface science perspective on TiO2 photocatalysis. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2011, 66, 185–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Tachikawa, T.; Moon, G.H.; Majima, T.; Choi, W. Molecular-level understanding of the photocatalytic activity difference between anatase and rutile nanoparticles. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 14036–14041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Li, H.; Muhammad, S.; Wu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Jiao, Q. Surfactant-assisted hydrothermal synthesis of TiO2/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites and their photocatalytic performances. J. Solid State Chem. 2017, 253, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, K.M.S.; El-Khatib, R.M.; Ali, T.T.; Mahmoud, H.A.; Elsamahy, A.A. Titania nanoparticles by acidic peptization of xerogel formed by hydrolysis of titanium(IV) isopropoxide under atmospheric humidity conditions. Powder Technol. 2013, 245, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellardita, M.; Di Paola, A.; Megna, B.; Palmisano, L. Absolute crystallinity and photocatalytic activity of brookite TiO2 samples. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Environ. 2016, 201, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payormhorm, J.; Chuangchote, S.; Laosiripojana, N. CTAB-assisted sol-microwave method for fast synthesis of mesoporous TiO2 photocatalysts for photocatalytic conversion of glucose to value-added sugars. Mater. Res. Bull. 2017, 95, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamine, S.; Sasaoka, E. Synthesis of nanostructured titania templated by anionic surfactant in acidic conditions. J. Porous Mater. 2002, 9, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Flores, S.; Martínez-Luévanos, A.; Perez-Berumen, C.M.; García-Cerda, L.A.; Flores-Guia, T.E. Relationship between morphology, porosity, and the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 obtained by sol–gel method assisted with ionic and nonionic surfactants. Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Vidr. 2020, 59, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuenyongsuwan, J.; Nithiyakorn, N.; Sabkird, P.; O’Rear, E.A.; Pongprayoon, T. Surfactant effect on phase-controlled synthesis and photocatalyst property of TiO2 nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 214, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassaignon, S.; Koelsch, M.; Jolivet, J.P. Selective synthesis of brookite, anatase, and rutile nanoparticles: Thermolysis of TiCl4 in aqueous nitric acid. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 6689–6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Guo, Q.; Li, J. A facile method for the structure control of TiO2 particles at low temperature. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 355, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.; Guo, Q.; Li, J. Size-controlled synthesis of dispersed equiaxed amorphous TiO2 nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 9057–9062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primet, M.; Pichat, P.; Mathieu, M.-V. Infrared study of the surface of titanium dioxides. J. Phys. Chem. 1971, 75, 1216–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martra, G. Lewis acid and base sites at the surface of microcrystalline anatase. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2000, 200, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Zhang, Y.; He, L.; An, R.; Li, B. Facile synthesis of amino-functionalized mesoporous TiO2 microparticles for adenosine deaminase immobilization. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 239, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, L.; Boerio-Goates, J.; Woodfield, B.F. High Purity Anatase TiO2 nanocrystals: near room-temperature synthesis, grain growth kinetics, and surface hydration chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 8659–8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorai, T.; Chakraborty, M.; Pramanik, P. Photocatalytic performance of nano-photocatalyst from TiO2 and Fe2O3 by mechanochemical synthesis. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 8158–8164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, R.; Góes, M.S.; Castro, M.S.; Longo, E.; Bueno, P.R.; Varela, J.A. Reaction pathway to the synthesis of anatase via the chemical modification of titanium isopropoxide with acetic acid. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, V. Comparison of size-dependent structural and electronic properties of anatase and rutile nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2009, 113, 6367–6380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussaoui, R.; Elghniji, K.; ben Mosbah, M.; Elaloui, E.; Moussaoui, Y. Sol–gel synthesis of highly TiO2 aerogel photocatalyst via high temperature supercritical drying. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2017, 21, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, P.; Viruthagiri, G.; Mugundan, S.; Shanmugam, N. Structural, optical and morphological analyses of pristine titanium di-oxide nanoparticles-synthesized via sol-gel route. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 117, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, B.A.; Cristóvão, R.O.; Djellabi, R.; Loureiro, J.M.; Boaventura, R.A.R.; Vilar, V.J.P. Photocatalytic reduction of Cr (VI) over TiO2 -coated cellulose acetate monolithic structures using solar light. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 203, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Porras, C.; Toxqui-Teran, A.; Vega-Becerra, O.; Miki-Yoshida, M.; Rojas-Villalobos, M.; García-Guaderrama, M.; Aguilar-Martínez, J.A. Low-temperature synthesis and characterization of anatase TiO2 nanoparticles by an acid assisted sol-gel method. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 647, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, S.; Termehyousefi, A.; Do, T.O. Photocatalytic pathway toward degradation of environmental pharmaceutical pollutants: Structure, kinetics and mechanism approach. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 4548–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, W.-J.; Tan, L.-L.; Chai, S.-P.; Yonga, S.T.; Mohamed, A.R. Highly Reactive {001} Facets of TiO2-Based Composites: Synthesis, Formation Mechanism and Characterizations. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 1946–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, A.; Majeed, I.; Malik, R.N.; Idriss, H.; Nadeem, M.A. Principles and mechanisms of photocatalytic dye degradation on TiO2 based photocatalysts: A comparative overview. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 37003–37026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, S.; Mehta, S.K.; Umar, A.; Kansal, S.K. The visible light-driven photocatalytic degradation of Alizarin red S using Bi-doped TiO2 nanoparticles. New J. Chem. 2014, 38, 3127–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutuma, B.K.; Shao, G.N.; Kim, W.D.; Kim, H.T. Sol-gel synthesis of mesoporous anatase-brookite and anatase-brookite-rutile TiO2 nanoparticles and their photocatalytic properties. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 442, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, R.; Gómez, R. Band-gap energy estimation from diffuse reflectance measurements on sol—Gel and commercial TiO2: A comparative study. J. Sol.-Gel. Sci. Technol. 2012, 61, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Zhao, R.; Xia, M. A facile approach to synthesis carbon quantum dots-doped P25 visible-light driven photocatalyst with improved NO removal performance. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Zhang, W.; Lan, T.; Xie, J.; Xie, W.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wei, M. Anatase TiO2 quantum dots with a narrow band gap of 2.85 eV based on surface hydroxyl groups exhibiting significant photodegradation property. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, R.; Zeng, Y.; Xia, X.; Liu, Y.; Luo, S. Facile synthesis of bird’s nest-like TiO2 microstructure with exposed (001) facets for photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 391, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T2 Sample | T3 Sample | T5 Sample | T7 Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | I41/AMD | I41/AMD | I41/AMD | I41/AMD |

| a (Å) | 3.7798(4) | 3.7829(3) | 3.7798(4) | 3.7850(2) |

| c (Å) | 9.474(1) | 9.4930(9) | 9.472(1) | 9.482(9) |

| V (Å3) | 135.353 | 135.847 | 135.325 | 136.207 |

| Z | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Ti (4b) Byssus, Oc | (0, 1/4, 3/8) 0.2523, 1 | (0, 1/4, 3/8) 0.177, 1 | (0, 1/4, 3/8) 0.691, 1 | (0, 1/4, 3/8) 0.465, 1 |

| O (8e) Byssus, Oc | (0, 1/4, 0.16508(15)) 0.623, 1 | (0, 1/4, 0.1658(1)) 0.250, 1 | (0, 1/4, 0.1658(1)) 0.193, 1 | (0, 1/4, 0.1613(1)) 0.316, 1 |

| Rp, Rwp, Rexp | 8.26, 8.97, 5.43 | 8.30, 9.13, 4.34 | 3.67, 4.75, 2.80 | 9.86, 10.4, 5.19 |

| x2 | 2.73 | 4.43 | 2.88 | 4.06 |

| % Brookite | 0 | 0 | 11.4 | 15.61 |

| Sample | SBET (m2g−1) | Average Pore Size (nm) | Average Pore Volume (cm3g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T2 | 232.02 | 3.18 | 0.46 |

| T3 | 138.70 | 5.86 | 0.30 |

| T5 | 118.90 | 12.72 | 0.36 |

| T7 | 79.50 | 10.52 | 0.20 |

| Sample | K2 (L/min·mol) | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| T2 | 1.69 × 104 | 0.9763 |

| T3 | 2.25 × 104 | 0.9665 |

| T5 | 1.06 × 104 | 0.9446 |

| T7 | 1.51 × 104 | 0.9872 |

| THNO3 | 1.17 × 104 | 0.9664 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Estrada-Flores, S.; Flores-Guia, T.E.; Pérez-Berumen, C.M.; García-Cerda, L.A.; Robledo-Cabrera, A.; Aguilera-González, E.N.; Martínez-Luévanos, A. Effect of Acetic Acid on Morphology, Structure, Optical Properties, and Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2 Obtained by Sol–Gel. Reactions 2026, 7, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions7010005

Estrada-Flores S, Flores-Guia TE, Pérez-Berumen CM, García-Cerda LA, Robledo-Cabrera A, Aguilera-González EN, Martínez-Luévanos A. Effect of Acetic Acid on Morphology, Structure, Optical Properties, and Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2 Obtained by Sol–Gel. Reactions. 2026; 7(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions7010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleEstrada-Flores, Sofía, Tirso E. Flores-Guia, Catalina M. Pérez-Berumen, Luis A. García-Cerda, Aurora Robledo-Cabrera, Elsa N. Aguilera-González, and Antonia Martínez-Luévanos. 2026. "Effect of Acetic Acid on Morphology, Structure, Optical Properties, and Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2 Obtained by Sol–Gel" Reactions 7, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions7010005

APA StyleEstrada-Flores, S., Flores-Guia, T. E., Pérez-Berumen, C. M., García-Cerda, L. A., Robledo-Cabrera, A., Aguilera-González, E. N., & Martínez-Luévanos, A. (2026). Effect of Acetic Acid on Morphology, Structure, Optical Properties, and Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2 Obtained by Sol–Gel. Reactions, 7(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions7010005