Structural and Catalytic Assessment of Clay-Spinel-TPA Nanocatalysts for Biodiesel Synthesis from Oleic Acid

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Catalyst Preparation

2.3. Catalyst Characterization

2.4. Catalyst Test

2.5. Catalyst Reusability

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Assessing the Divalent Cation Type in the Spinel Structure of the Composite Structure and Performance

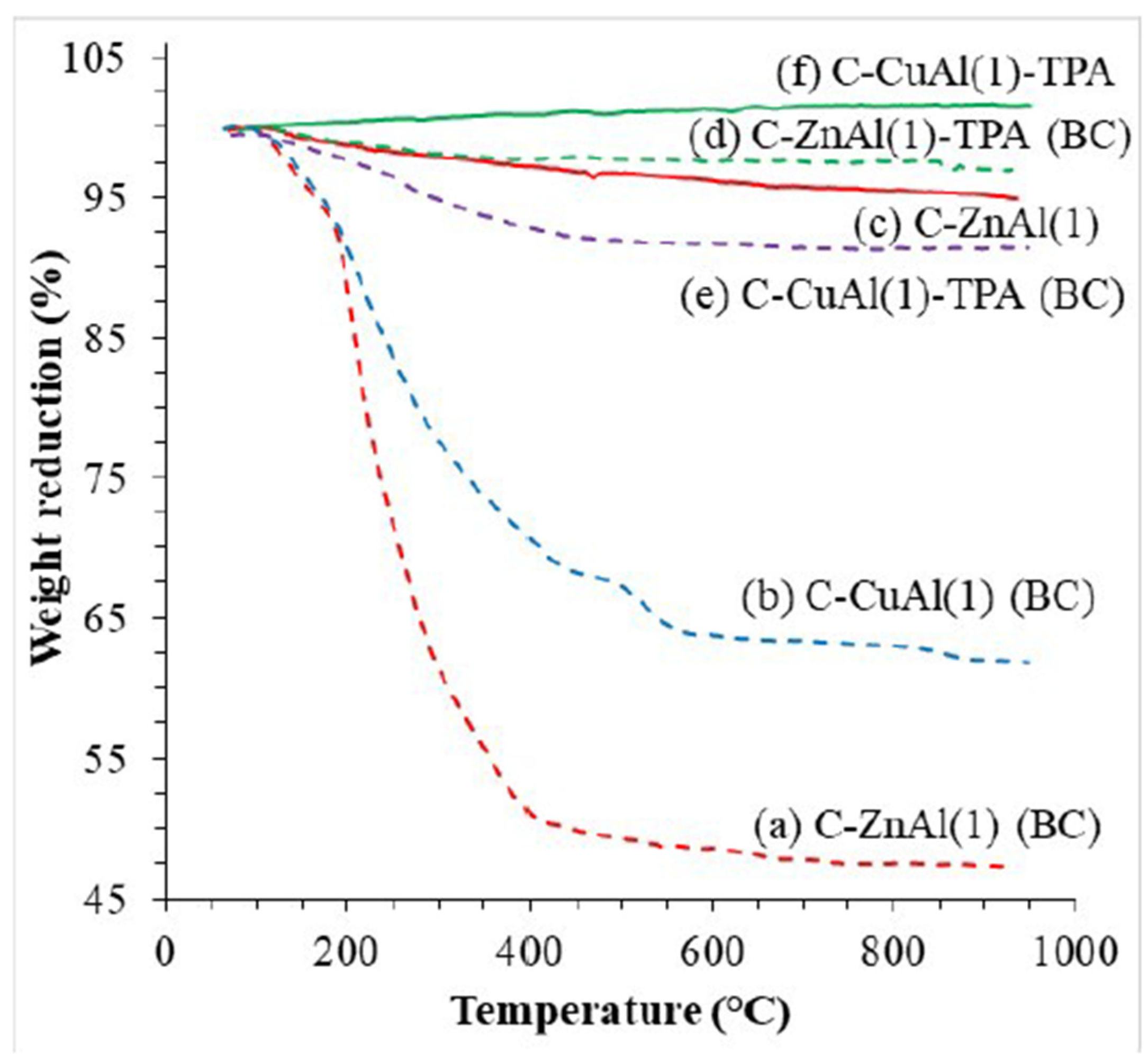

3.1.1. TG Analysis

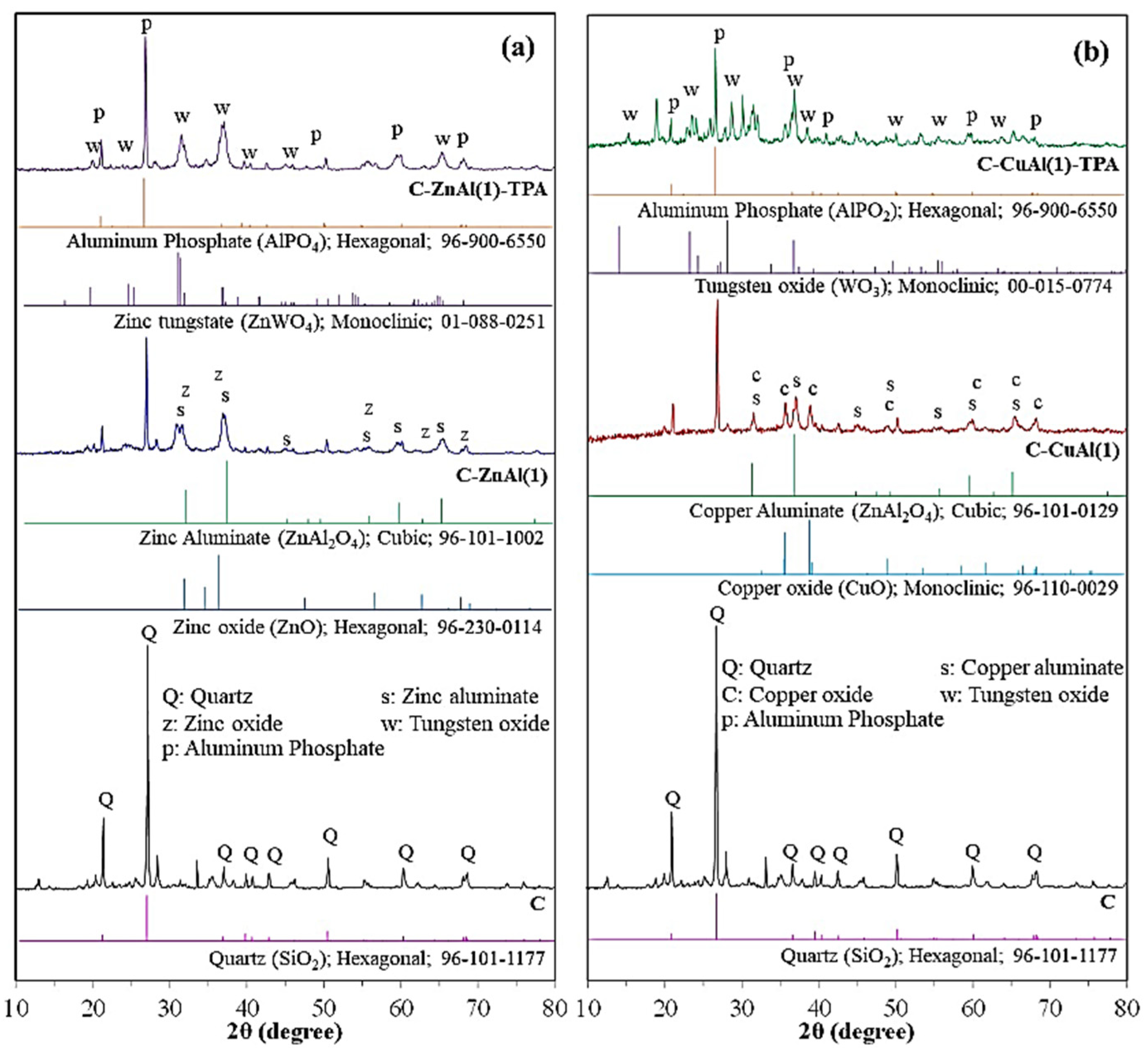

3.1.2. XRD Analysis

3.1.3. FTIR Analysis

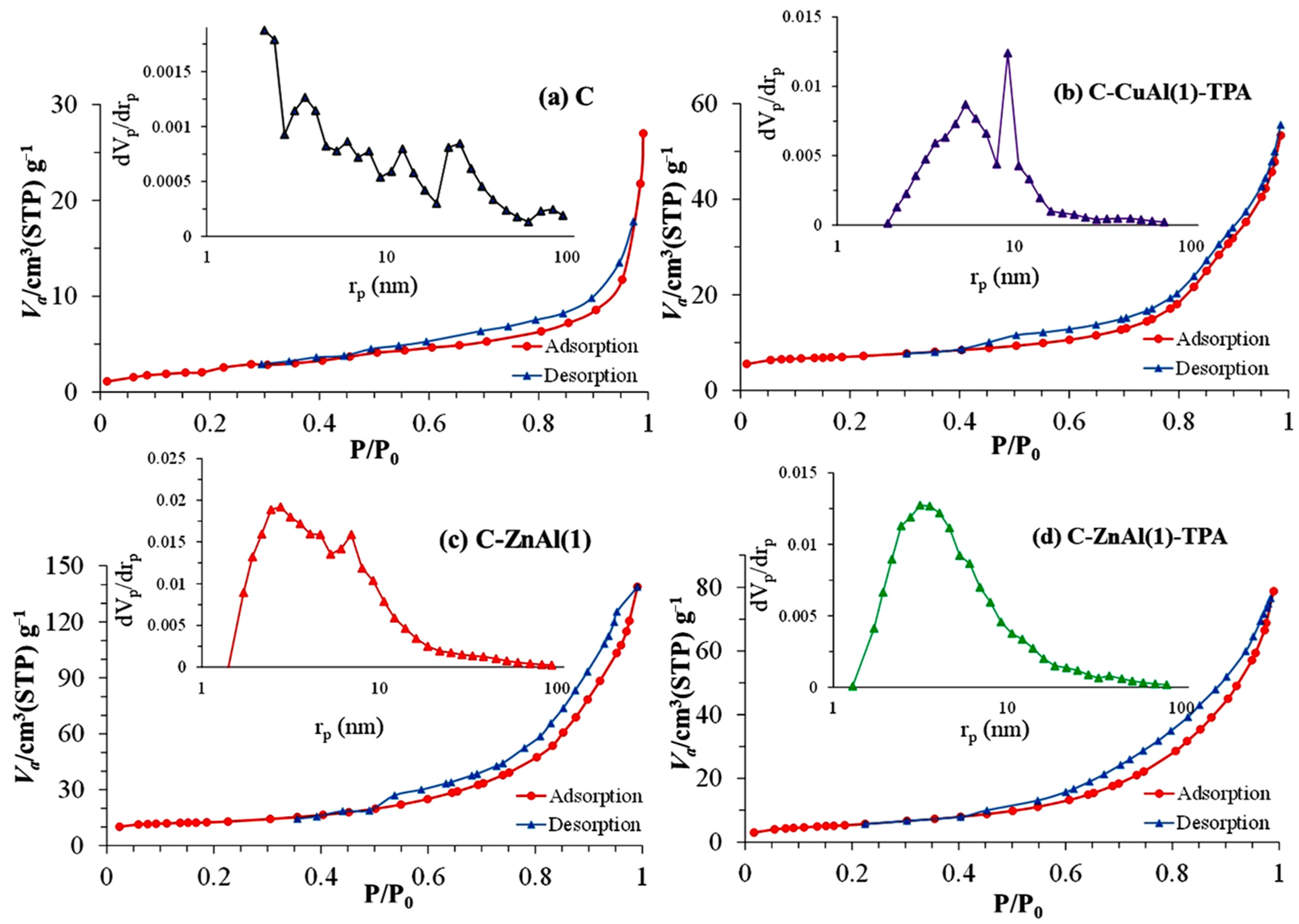

3.1.4. BET Analysis

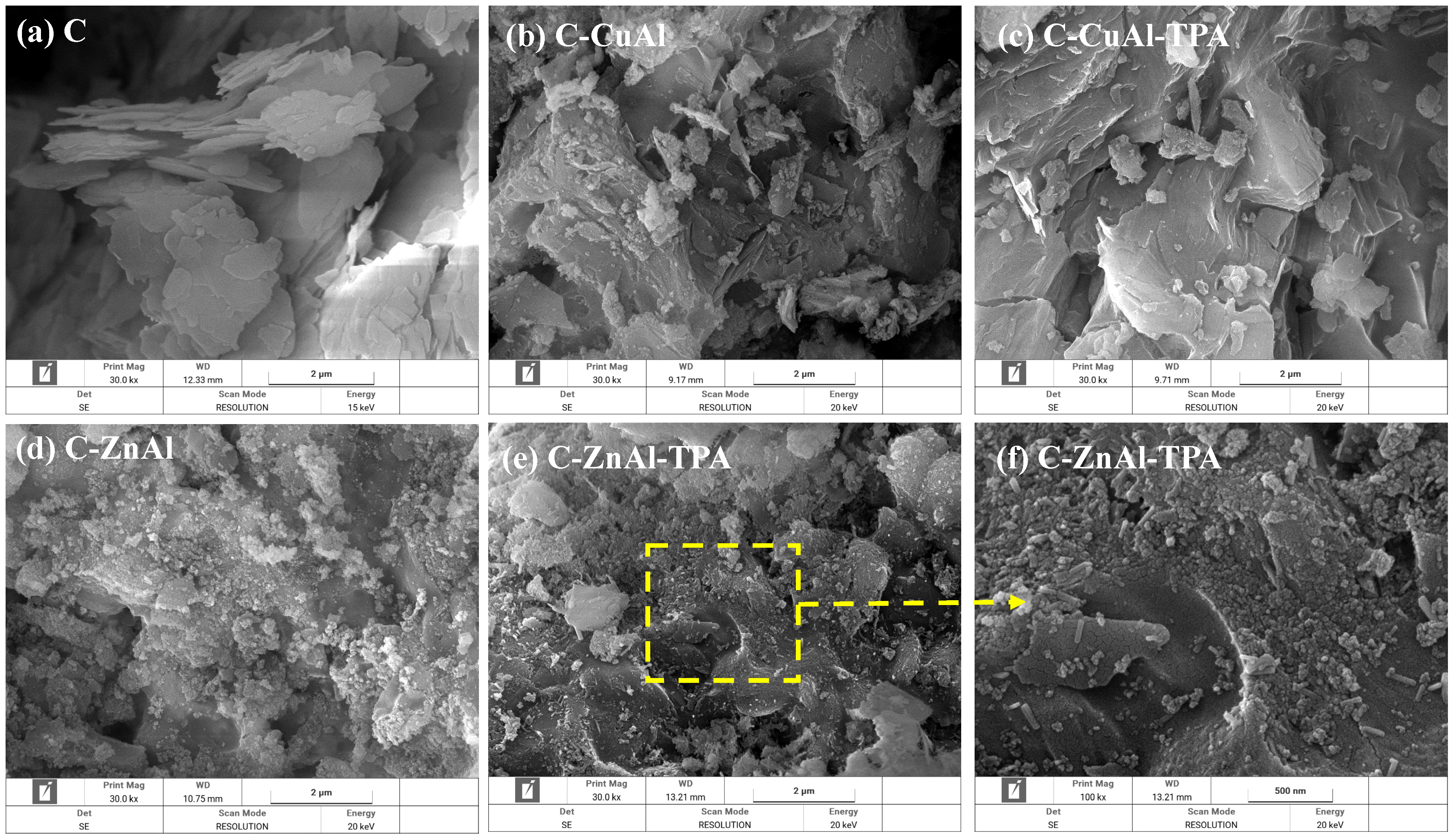

3.1.5. FESEM Analysis

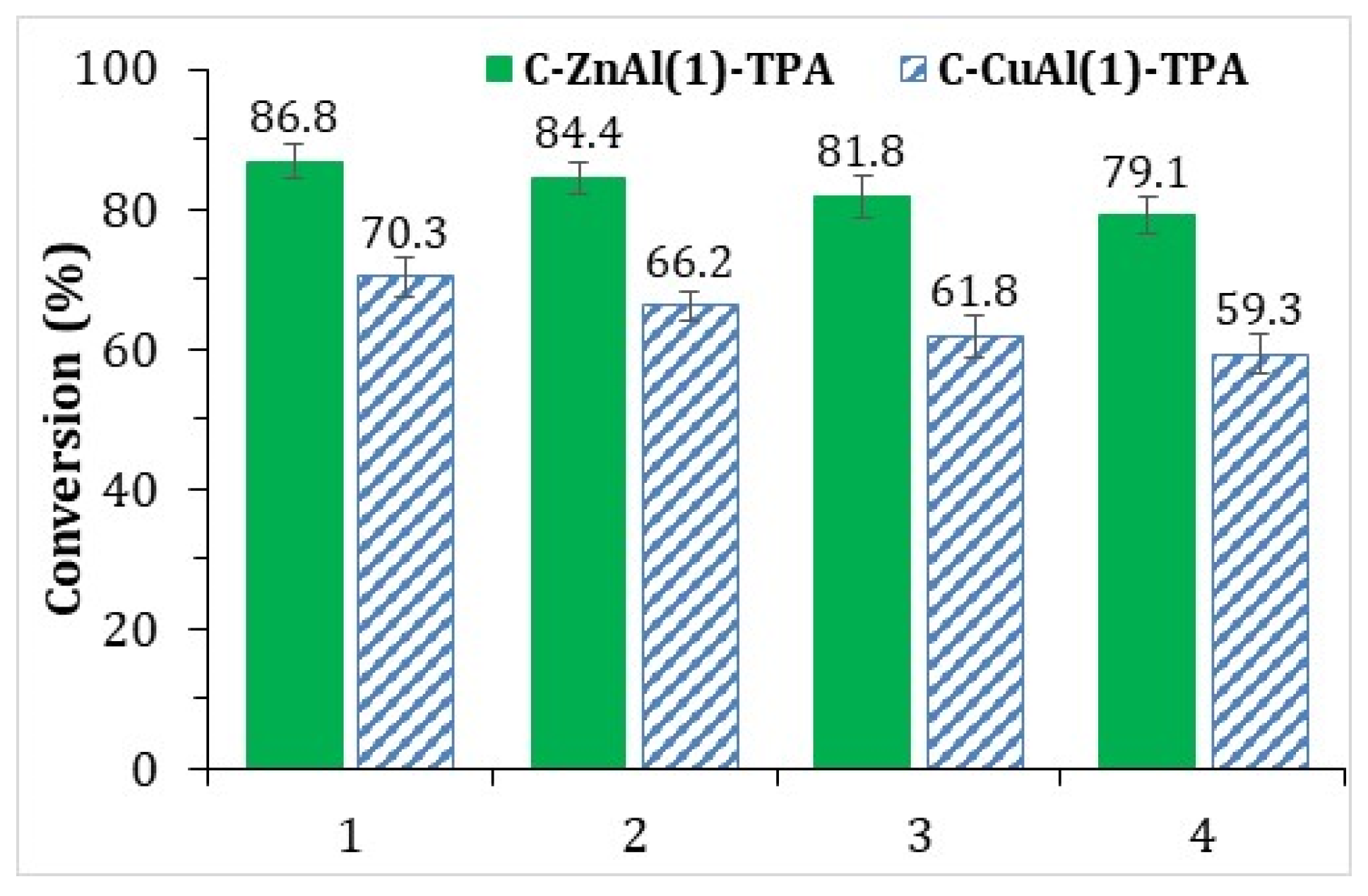

3.2. Catalyst Activity and Reusability Assessment

3.3. Assessing the Effect of the Clay/Spinel Ratio on the Structure and Activity of the Composite

3.3.1. XRD Analysis for C-ZnAl-TPA Composite

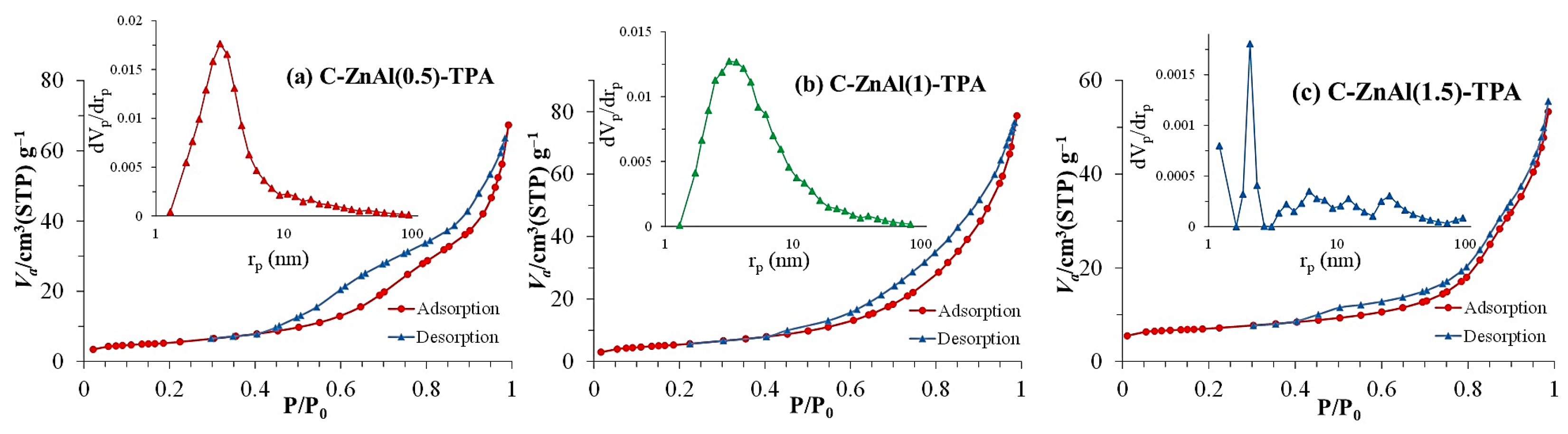

3.3.2. BET-BJH Analysis

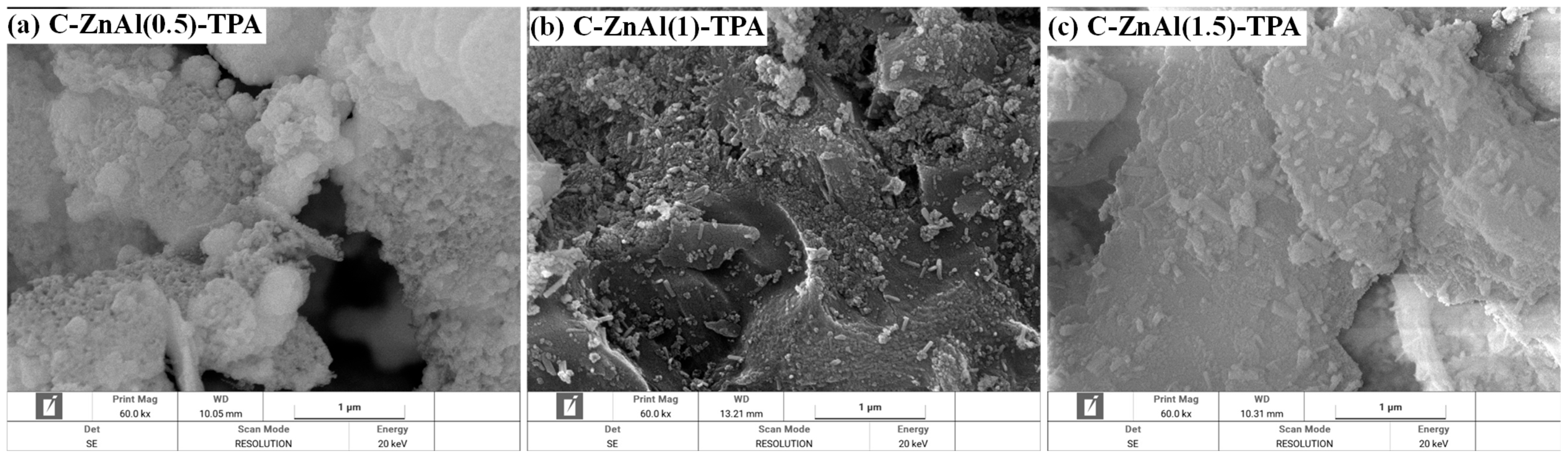

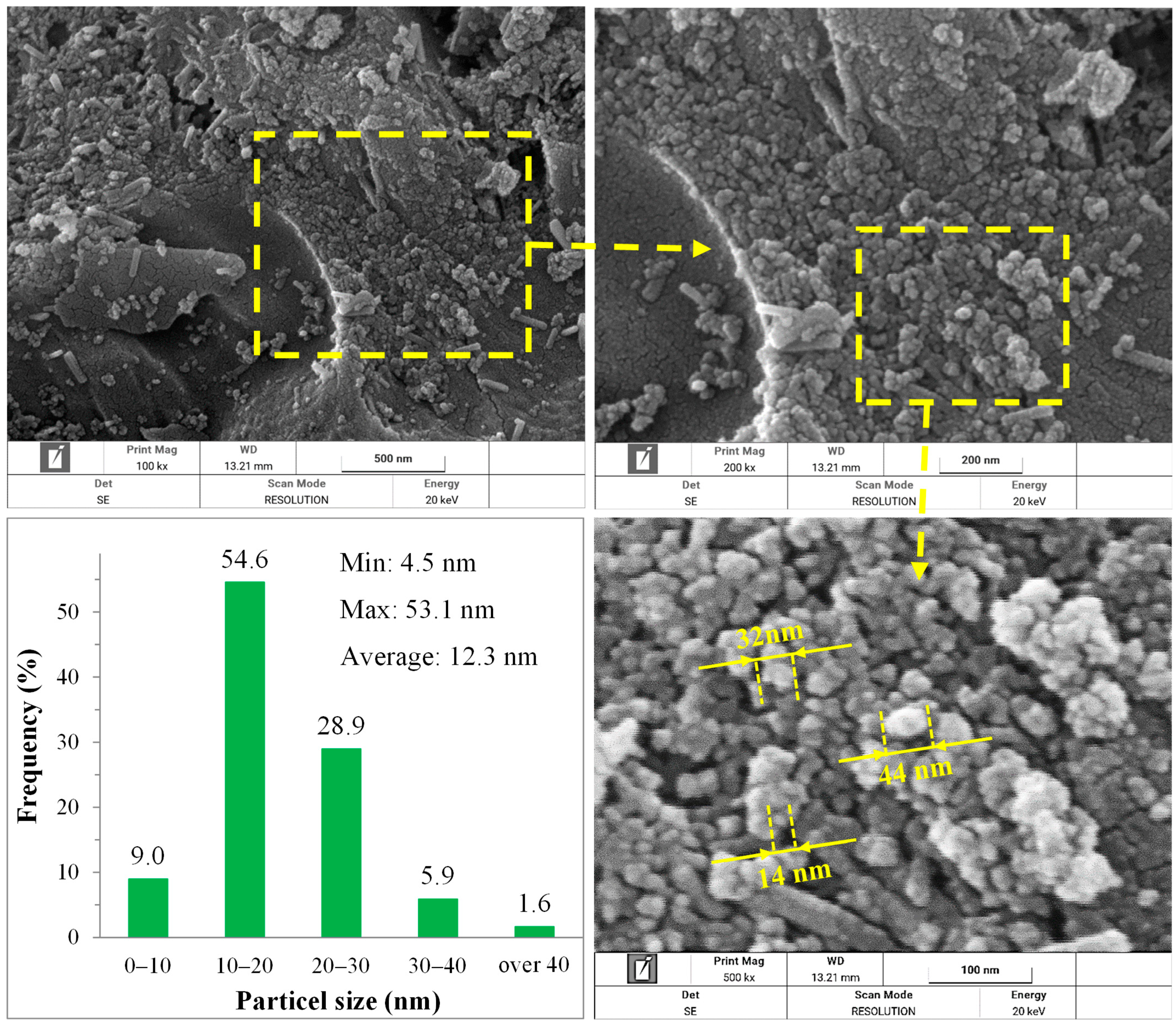

3.3.3. FESEM Analysis for C-ZnAl-TPA Composite

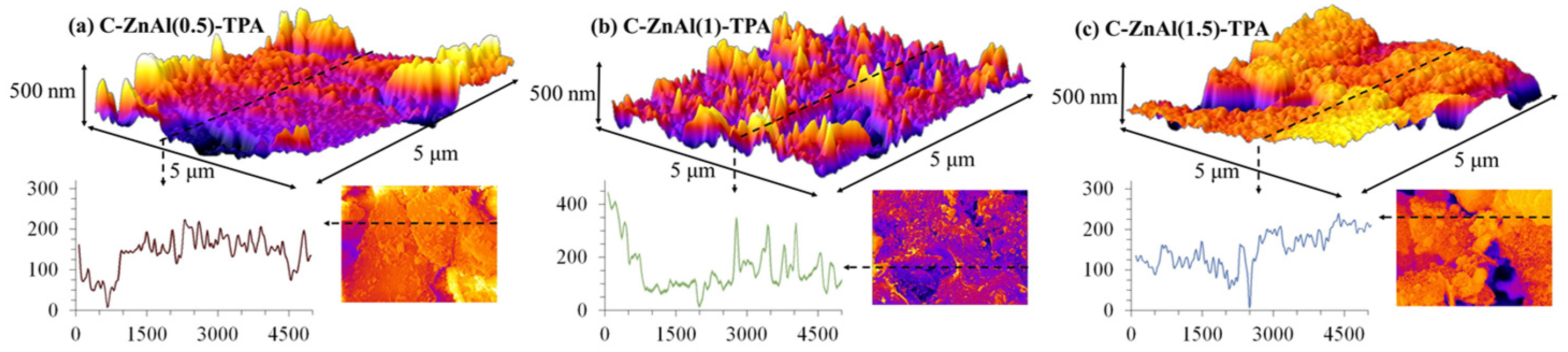

3.3.4. Three-Dimensional Surface Roughness Analysis

3.3.5. Particle Size Distribution

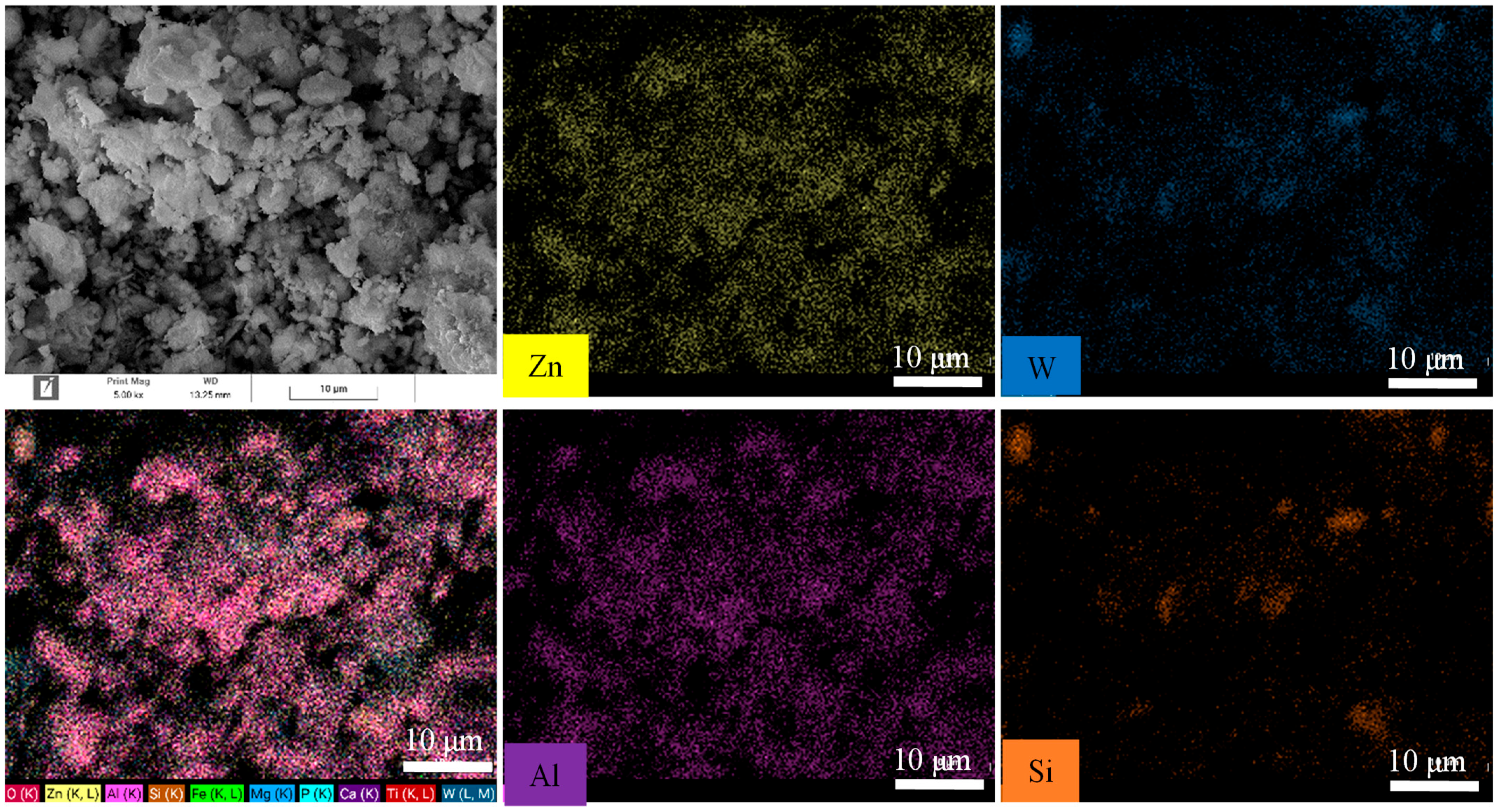

3.3.6. EDS and Dot-Mapping Analysis

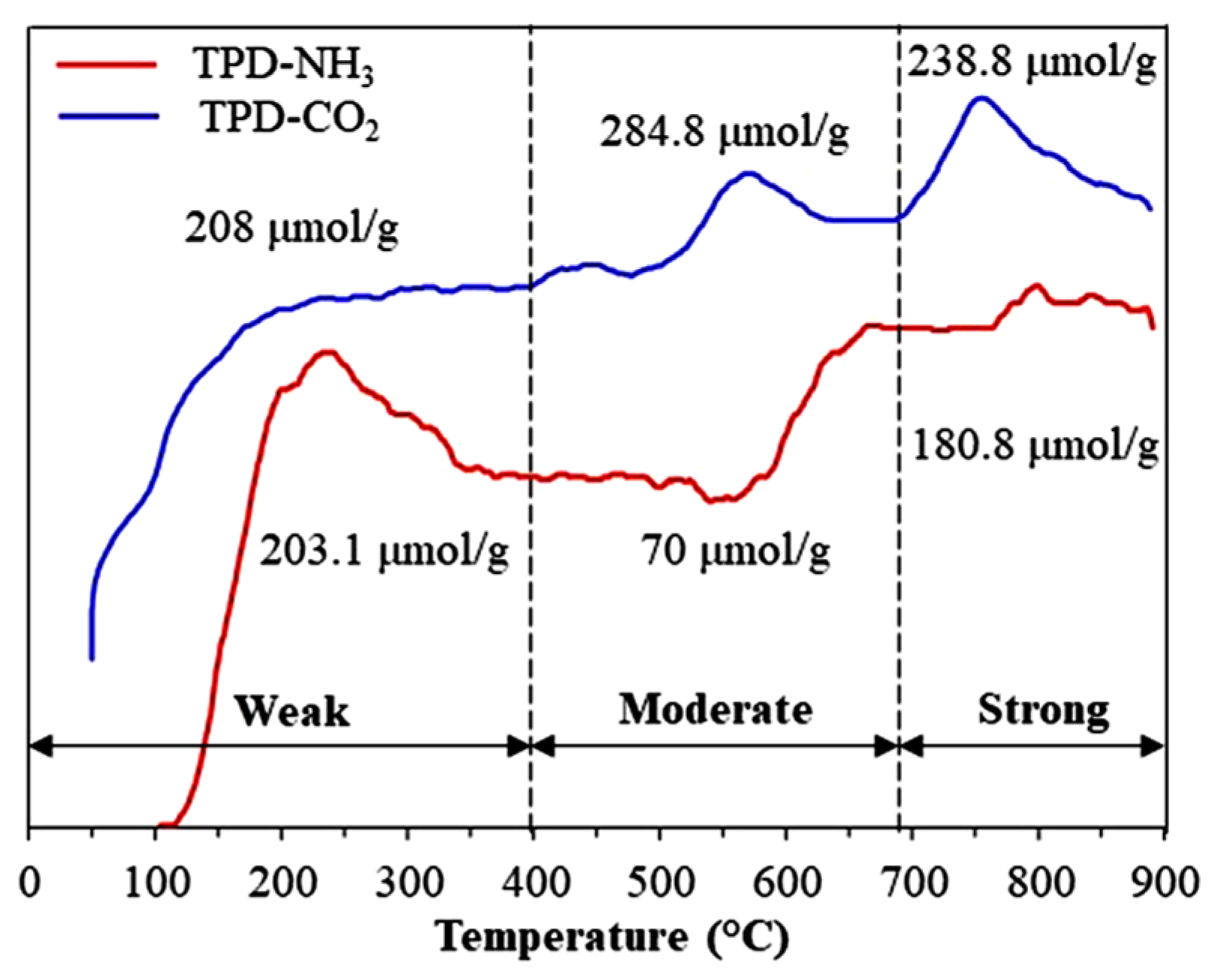

3.3.7. TPD-CO2 and TPD-NH3 Analyses

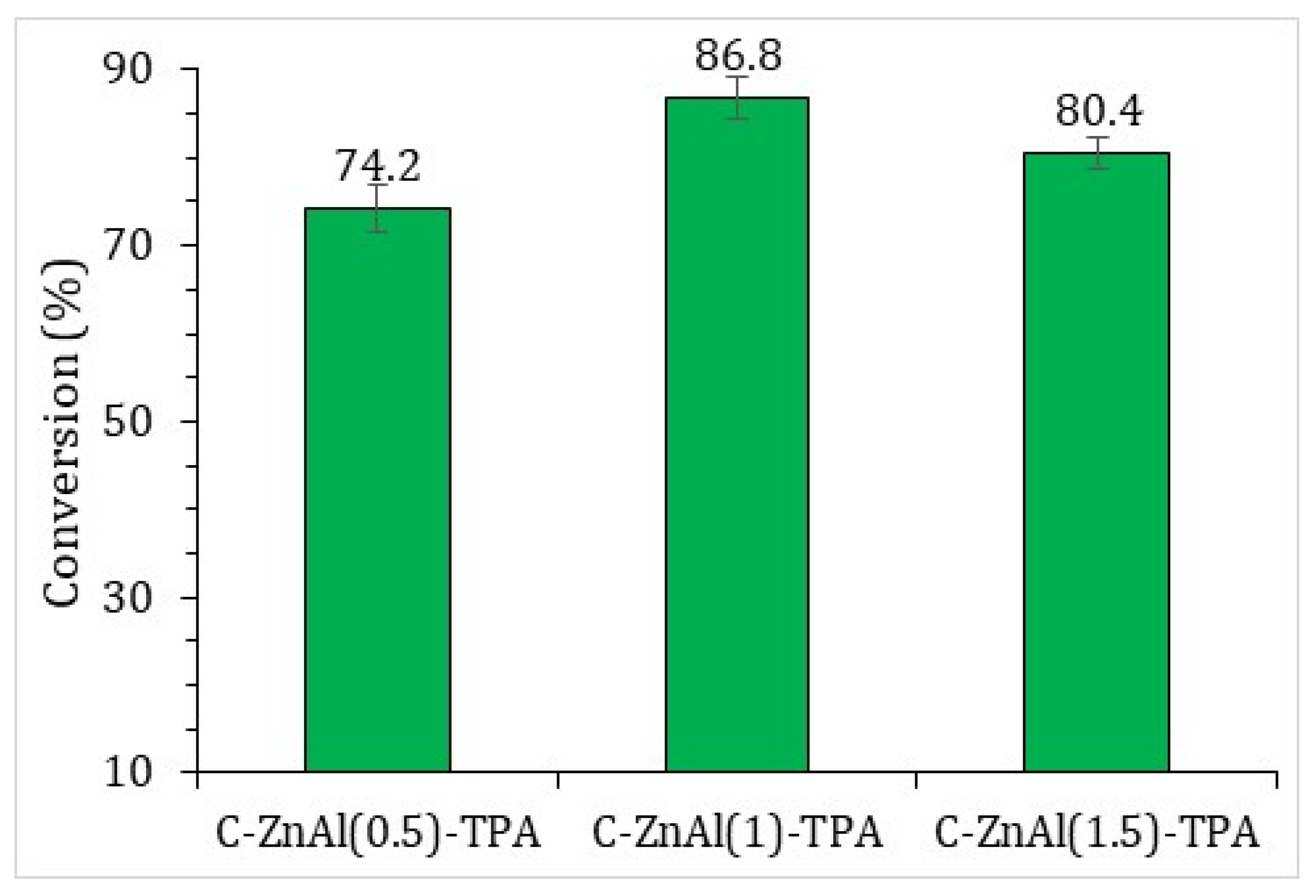

3.4. Catalyst Activity

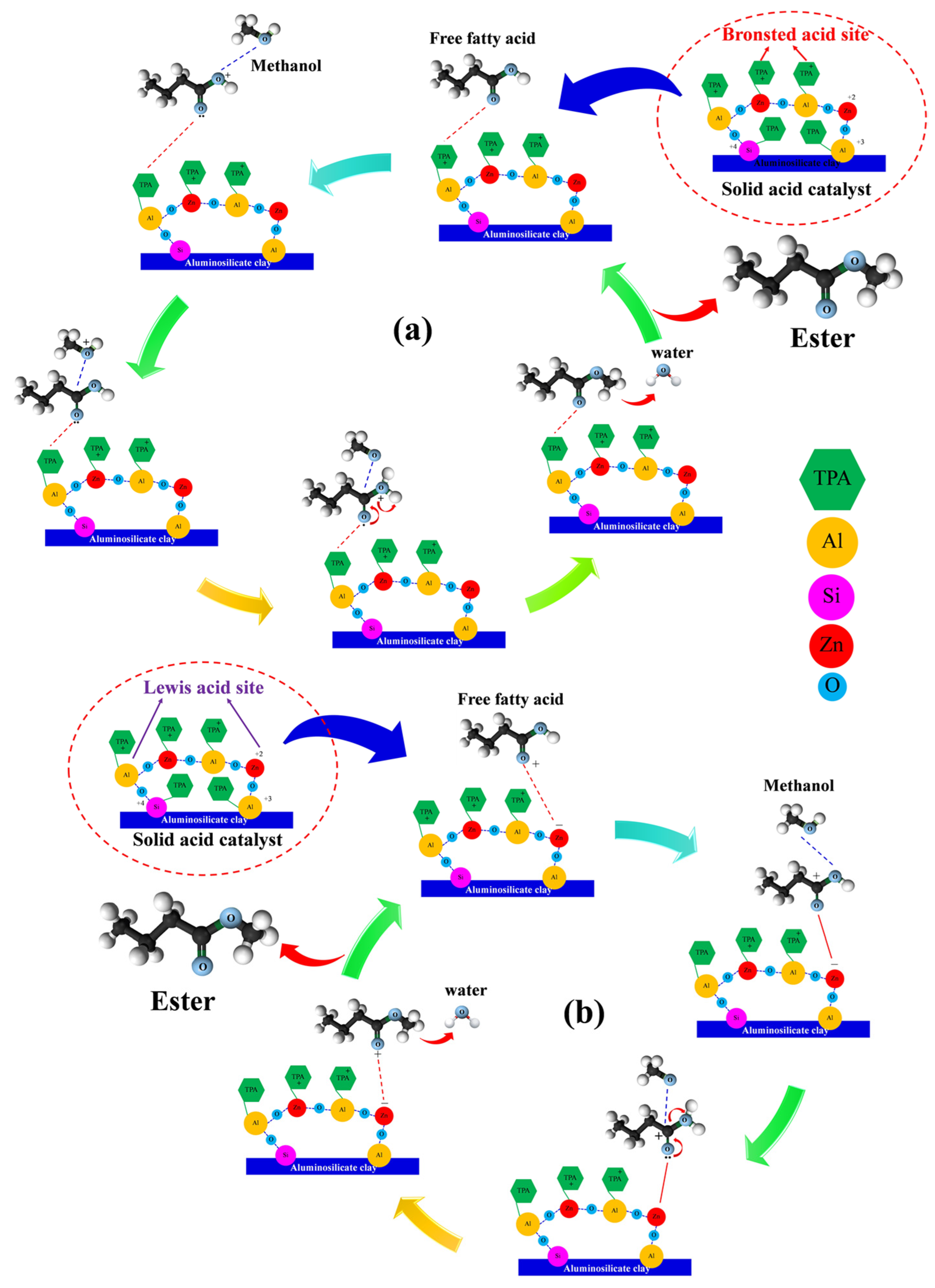

3.5. Reaction Mechanism

3.6. Comparison of the Results

| Sample | Feedstock | Reaction Conditions | Conv. | Reus. | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp. (°C) | MOR | Cat. (wt%) | Time (h) | |||||

| Ca-Clay | Jatropha oil | 65 | 12 | 3 | 4 | 97 | 5 | [36] |

| SO42−/Clay | Oleic acid | 55 | 12 | 6 | 2 | 80.8 | 0 | [74] |

| Acidized MMT | Oleic acid | 120 | 30 | 10 | 3 | 99 | 1 | [75] |

| ZnAl2O4 | Oleic acid | 180 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 94 | 4 | [50] |

| S/ZnAl2O4–ZrO2 | Oleic acid | 65 | 25 | 5 | 8 | 87 | 2 | [76] |

| S/ZA-Kao | Oleic acid | 65 | 25 | 5 | 8 | 70.1 | 4 | [65] |

| C-ZnAl (1)-TPA | Oleic acid | 120 | 12 | 6 | 4 | 86.6 | 4 | This study |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Osman, W.N.A.W.; Rosli, M.H.; Mazli, W.N.A.; Samsuri, S. Comparative review of biodiesel production and purification. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.M.; Wang, W.; Bujold, J. Biodiesel production and comparison of emissions of a DI diesel engine fueled by biodiesel–diesel and canola oil–diesel blends at high idling operations. Appl. Energy 2013, 106, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, M.A.; Wu, S.; Zhu, J.; Krosuri, A.; Khan, M.U.; Ndeddy Aka, R.J. Recent development of advanced processing technologies for biodiesel production: A critical review. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 227, 107120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babadi, A.A.; Rahmati, S.; Fakhlaei, R.; Barati, B.; Wang, S.; Doherty, W.; Ostrikov, K. Emerging technologies for biodiesel production: Processes, challenges, and opportunities. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 163, 106521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duan, L.; Esmaeili, H. A review on biodiesel production using various heterogeneous nanocatalysts: Operation mechanisms and performances. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 158, 106356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, P.R.; Mohapatra, A. Calcium-Based Nanocatalysts in Biodiesel Production. In Nano- and Biocatalysts for Biodiesel Production; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, G.; González-Carballo, J.M.; Tosheva, L.; Tedesco, S. Synergistic catalytic effect of sulphated zirconia—HCl system for levulinic acid and solid residue production using microwave irradiation. Energies 2021, 14, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lani, N.S.; Ngadi, N.; Inuwa, I.M.; Opotu, L.A.; Zakaria, Z.Y.; Haron, S. A cleaner approach with magnetically assisted reactor setup over CaO-zeolite/Fe3O4 catalyst in biodiesel production: Evaluation of catalytic performance, reusability and life cycle assessment studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 138329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lani, N.S.; Ngadi, N. Highly efficient CaO–ZSM-5 zeolite/Fe3O4 as a magnetic acid–base catalyst upon biodiesel production from used cooking oil. Appl. Nanosci. 2022, 12, 3755–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, I.; Yanti, I.; Suharto, T.E.; Sagadevan, S. ZrO2-based catalysts for biodiesel production: A review. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 143, 109808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, I.; Fadillah, G.; Sagadevan, S.; Oh, W.C.; Ameta, K.L. Mesoporous Silica-Based Catalysts for Biodiesel Production: A Review. ChemEngineering 2023, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, B.; Esmaeili, H. Application of Fe3O4/SiO2@ZnO magnetic composites as a recyclable heterogeneous nanocatalyst for biodiesel production from waste cooking oil: Response surface methodology. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 11452–11463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costarrosa Morales, L.; Leiva-Candia, D.E.; Cubero-Atienza, A.J.; Ruiz, J.J.; Dorado, M.P. Optimization of the Transesterification of Waste Cooking Oil with Mg-Al Hydrotalcite Using Response Surface Methodology. Energies 2018, 11, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; You, J.; Liu, B. Preparation of mesoporous silica supported sulfonic acid and evaluation of the catalyst in esterification reactions. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2019, 128, 493–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qaysi, K.; Nayebzadeh, H.; Saghatoleslami, N. Comprehensive Study on the Effect of Preparation Conditions on the Activity of Sulfated Silica–Titania for Green Biofuel Production. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 3999–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Delbari, S.A.; Sabahi Namini, A.; Le, Q.V.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, D.; Varma, R.S.; Jang, H.W.; T.-Raissi, A.; Shokouhimehr, M.; et al. Recent developments in solid acid catalysts for biodiesel production. Mol. Catal. 2023, 547, 113362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmi, F.; Borugadda, V.B.; Dalai, A.K. Heteropoly acids as supported solid acid catalysts for sustainable biodiesel production using vegetable oils: A review. Catal. Today 2022, 404, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroi, C.; Dalai, A.K. Review on Biodiesel Production from Various Feedstocks Using 12-Tungstophosphoric Acid (TPA) as a Solid Acid Catalyst Precursor. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 18611–18624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemzadeh, B.; Matin, A.A.; Habibi, B.; Ebadi, M. Cotton/Fe3O4@SiO2@H3PW12O40 a magnetic heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production: Process optimization through response surface methodology. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 181, 114806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Wang, X.M.; Gao, D.; Wang, F.P.; Zeng, Y.N.; Li, J.G.; Jiang, L.Q.; Yu, Q.; Ji, R.; Kang, L.L.; et al. Efficient production of biodiesel at low temperature using highly active bifunctional Na-Fe-Ca nanocatalyst from blast furnace waste. Fuel 2022, 322, 124168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamjidi, S.; Esmaeili, H.; Moghadas, B.K. Performance of functionalized magnetic nanocatalysts and feedstocks on biodiesel production: A review study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 305, 127200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Qu, T.; Niu, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Geng, J.; Yang, Z.; Abulizi, A. Preparation and characterization of a novel bifunctional heterogeneous Sr–La/wollastonite catalyst for biodiesel production. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 26, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latchubugata, C.S.; Kondapaneni, R.V.; Patluri, K.K.; Virendra, U.; Vedantam, S. Kinetics and optimization studies using Response Surface Methodology in biodiesel production using heterogeneous catalyst. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2018, 135, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshbin, R.; Naeimi, M.; Alikhani, F.M.; Hashemi, M.S.; Moradi, H. Novel approach for synthesis of highly active nanostructured MgO/ZnAl2O4 catalyst via gel-combustion method used in biofuel production from sunflower oil: Effect of mixed fuel. Adv. Powder Technol. 2023, 34, 104226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, E.; Ozaltin, K.; Spagnuolo, D.; Bernal-Ballen, A.; Piskunov, M.V.; Di Martino, A. Biodiesel from rapeseed and sunflower oil: Effect of the transesterification conditions and oxidation stability. Energies 2023, 16, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, I.; Qamar, O.A.; Jamil, F.; Hussain, M.; Inayat, A.; Rocha-Meneses, L.; Akhter, P.; Musaddiq, S.; Karim, M.R.A.; Park, Y. Comparative study of enhanced catalytic properties of clay-derived SiO2 catalysts for biodiesel production from waste chicken fat. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 40, 2683–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.; Ahmad, M.; Rehan, M.; Saeed, M.; Lam, S.S.; Nizami, A.S.; Waseem, A.; Sultana, S.; Zafar, M. Production of high quality biodiesel from novel non-edible Raphnus raphanistrum L. seed oil using copper modified montmorillonite clay catalyst. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeyta, K.P.; da Silva, M.L.A.; Silva, C.L.S.; Pontes, L.A.M.; Teixeira, L.S.G. Clay-based catalysts applied to glycerol valorization: A review. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 40, 101641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohadesi, M.; Aghel, B.; Gouran, A.; Razmehgir, M.H. Transesterification of waste cooking oil using Clay/CaO as a solid base catalyst. Energy 2022, 242, 122536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olutoye, M.A.; Hameed, B.H. A highly active clay-based catalyst for the synthesis of fatty acid methyl ester from waste cooking palm oil. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2013, 450, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.H. An overview on strategies towards clay-based designer catalysts for green and sustainable catalysis. Appl. Clay Sci. 2011, 53, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.H.; Chen, B.H.; Lee, D.J. Application of kaolin-based catalysts in biodiesel production via transesterification of vegetable oils in excess methanol. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 145, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altalhi, A.A.; Mohamed, E.A.; Morsy, S.M.; Abou Kana, M.T.H.; Negm, N.A. Sustainable biofuel production from non-edible oils utilizing modified montmorillonite based porous clay heterostructures. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2022, 44, 9956–9973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchuessa, E.B.H.; Ouédraogo, I.W.K.; Richardson, Y.; Sidibé, S.D.S. Production of Biodiesel by Ethanolic Transesterification of Sunflower Oil on Lateritic Clay- based Heterogeneous Catalyst. Catal. Lett. 2023, 153, 2443–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño, Y.; Faba, L.; Díaz, E.; Ordóñez, S. Biodiesel production from sewage sludge using supported heteropolyacid as heterogeneous acid catalyst. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Muhammad, Y.; Yu, S.; Fu, T.; Liu, K.; Tong, Z.; Hu, X.; Zhang, H. Preparation of Ca-and Na-Modified Activated Clay as a Promising Heterogeneous Catalyst for Biodiesel Production via Transesterification. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmi, M.; Ghadiri, M.; Tahvildari, K.; Hemmati, A. Biodiesel synthesis using clinoptilolite-Fe3O4-based phosphomolybdic acid as a novel magnetic green catalyst from salvia mirzayanii oil via electrolysis method: Optimization study by Taguchi method. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Wang, J.; Lu, C.; Xu, M.; Lv, J.; Wu, X. Esterification for biofuel synthesis over an eco-friendly and efficient kaolinite-supported SO42−/ZnAl2O4 macroporous solid acid catalyst. Fuel 2018, 234, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Yang, G.; Li, L.; Yu, J. Esterification of Oleic Acid to Produce Biodiesel over 12-Tungstophosphoric Acid Anchored Two-dimensional Zeolite. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2021, 37, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, S.; Manikandan, V.; Albeshr, M.F.; Dixit, S.; Song, K.S.; Lo, H.M. Utilizing Cs-TPA/Ce-KIT-6 solid-acid catalyst for enhanced biodiesel production from almond and amla oil feedstocks. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 185, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, F.; Gonzalez-Cortes, S.; Mirzaei, A.; Xiao, T.; Rafiq, M.A.; Zhang, X. Solution combustion synthesis: The relevant metrics for producing advanced and nanostructured photocatalysts. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 11806–11868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Niu, S.; Lu, C.; Gong, Z.; Hu, X. Catalytic performance of NaAlO2/γ-Al2O3 as heterogeneous nanocatalyst for biodiesel production: Optimization using response surface methodology. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 203, 112263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, J.S.; Mora, J.R. Metal Oxide/Sulphide-Based Nanocatalysts in Biodiesel Synthesis. In Advanced Nanocatalysts for Biodiesel Production; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 93–119. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, M.; Sharma, Y.C. Process optimization and catalyst poisoning study of biodiesel production from kusum oil using potassium aluminum oxide as efficient and reusable heterogeneous catalyst. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.Y.; Shih, K.; Leckie, J.O. Formation of copper aluminate spinel and cuprous aluminate delafossite to thermally stabilize simulated copper-laden sludge. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 181, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemzehi, M.; Saghatoleslami, N.; Nayebzadeh, H. Microwave-assisted solution Combustion Synthesis of Spinel-type mixed Oxides for Esterification Reaction. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2016, 204, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshani, R.; Tadjarodi, A.; Ghaffarinejad, A. The effect of annealing temperature on the structure and supercapacitive properties of copper tungstate. Mater. Lett. 2021, 293, 129644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Gao, D.; Li, Y.; Dong, H.; Zhou, W.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y. Fabrication of novel CuWO4 nanoparticles (NPs) for photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue in aqueous solution. SN Appl. Sci. 2018, 1, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffar, A.; Ahangar, H.A.; Aghili, A.; Hassanzadeh-Tabrizi, S.A.; Aminsharei, F.; Rahimi, H.; Kupai, J.A. Synthesis of the novel CuAl2O4–Al2O3–SiO2 nanocomposites for the removal of pollutant dye and antibacterial applications. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2021, 47, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Xu, M.L.; Liu, B.; Wang, X.F.; Wang, S.H.; Sun, T. Preparation of zinc tungstate nanomaterial and its sonocatalytic degradation of meloxicam as a novel sonocatalyst in aqueous solution. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 61, 104815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, H.L.; Tijani, J.O.; Abdulkareem, S.A.; Mann, A.; Mustapha, S. A review on the applications of zinc tungstate (ZnWO4) photocatalyst for wastewater treatment. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.C.; Harriott, P. The effect of crystallite size on the activity and selectivity of silver catalysts. J. Catal. 1975, 39, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandiyanto, A.B.D.; Zaen, R.; Oktiani, R. Correlation between crystallite size and photocatalytic performance of micrometer-sized monoclinic WO3 particles. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 1283–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.; Raghupathi, K.R.; Pierre, J.S.; Zhao, D.; Koodali, R.T. Tuning of the Crystallite and Particle Sizes of ZnO Nanocrystalline Materials in Solvothermal Synthesis and Their Photocatalytic Activity for Dye Degradation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 13844–13850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, N.J.; Bharali, D.J.; Sengupta, P.; Bordoloi, D.; Goswamee, R.L.; Saikia, P.C.; Borthakur, P.C. Characterization, beneficiation and utilization of a kaolinite clay from Assam, India. Appl. Clay Sci. 2003, 24, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tironi, A.; Trezza, M.A.; Irassar, E.F.; Scian, A.N. Thermal Treatment of Kaolin: Effect on the Pozzolanic Activity. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2012, 1, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Hu, H.; Meng, Z.; Zhu, X.; Gu, R.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, D.; Gan, H.; Wang, J.; et al. Characterization and Hemostatic Potential of Two Kaolins from Southern China. Molecules 2019, 24, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallakpour, S.; Jarahiyan, A. Surface treatment of copper (II) oxide nanoparticles using citric acid and ascorbic acid as biocompatible molecules and their utilization for the preparation of poly(vinyl chloride) novel nanocomposite films. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2017, 30, 1267–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, A.; Maddahfar, M. Synthesis and characterization of novel samarium-doped CuAl2O4 and its photocatalytic performance through the modified sol–gel method. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 3341–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, T.L.; Maia, G.A.R.; Gonçalves, L.F.; Viomar, A.; Banczek, E.D.P.; Rodrigues, P.R.P. Study of the Nb2O5 Insertion in ZnO to Dye-sensitized Solar Cells. Mater. Res. 2019, 22, e20180864. [Google Scholar]

- Nakane, T.; Naka, T.; Nakayama, M.; Uchikoshi, T. Direct bottom-up synthesis of ZnAl2O4 nanoparticle via organic ligand dissolution method. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 13269–13278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aher, D.S.; Khillare, K.R.; Chavan, L.D.; Shankarwar, S.G. Tungsten-substituted molybdophosphoric acid impregnated with kaolin: Effective catalysts for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones via biginelli reaction. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 2783–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zhu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, B.; Ma, J. Kaolin supported heteropoly acid catalysts for methacrolein oxidation: Insights into the carrier acidity effect on active components. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2023, 649, 118942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, G.D. Synergism of Clay and Heteropoly Acids as Nano-Catalysts for the Development of Green Processes with Potential Industrial Applications. Catal. Surv. Asia 2005, 9, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San, K.P. A Novel Hydrophobic ZrO2-SiO2 Based Heterogeneous Acid Catalyst for the Esterification of Glycerol with Oleic Acid. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zillillah; Ngu, T.A.; Li, Z. Phosphotungstic acid-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles as an efficient and recyclable catalyst for the one-pot production of biodiesel from grease via esterification and transesterification. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 1202–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.S.; Yogita; Lakshmi, D.D.; Kumari, P.K.; Lingaiah, N. Influence of metal oxide and heteropoly tungstate location in mesoporous silica towards catalytic transfer hydrogenation of furfural to γ-valerolactone. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2021, 5, 3719–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geetha, G.V.; Sivakumar, R.; Sanjeeviraja, C.; Ganesh, V. Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye using ZnWO4 catalyst prepared by a simple co-precipitation technique. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2021, 97, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ede, S.R.; Ramadoss, A.; Nithiyanantham, U.; Anantharaj, S.; Kundu, S. Bio-molecule assisted aggregation of ZnWO4 nanoparticles (NPs) into chain-like assemblies: Material for high performance supercapacitor and as catalyst for benzyl alcohol oxidation. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 3851–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, W.Y.; Aliç, F.; Verberckmoes, A.; Van Der Voort, P. Tuning the acidic–basic properties by Zn-substitution in Mg–Al hydrotalcites as optimal catalysts for the aldol condensation reaction. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 628–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Gu, Z.; Han, M.; Chen, C.; Chen, Z.; Ding, J.; Wang, Q.; Wan, H.; Guan, G. Preparation of heterogeneous interfacial catalyst benzimidazole-based acid ILs@MIL-100(Fe) and its application in esterification. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 608, 125585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Pu, J.; Wu, J.; Liu, H.; Xu, H.; Li, X.; Wang, H. SO42−/ZrO2 as a solid acid for the esterification of palmitic acid with methanol: Effects of the calcination time and recycle method. ACS Omega 2020, 46, 30139–30147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, S.; Kumar, P.S.M.; Arafath, K.A.Y.; Thiruvengadaravi, K.V.; Sivanesan, S.; Baskaralingam, P. Efficient mesoporous SO42−/Zr-KIT-6 solid acid catalyst for green diesel production from esterification of oleic acid. Fuel 2017, 203, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decarpigny, C.; Aljawish, A.; His, C.; Fertin, B.; Bigan, M.; Dhulster, P.; Millares, M.; Froidevaux, R. Bioprocesses for the Biodiesel Production from Waste Oils and Valorization of Glycerol. Energies 2022, 15, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Hart, C.R.; Casadonte, D. Ultrasound-assisted solid Lewis acid-catalyzed transesterification of Lesquerella fendleri oil for biodiesel synthesis. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 88, 106082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, A.; Liao, Y.; Shi, L.; Yang, L. Development of SO42−/ZnAl2O4–ZrO2 composite solid acids for efficient synthesis of green biofuels via the typical esterification reaction of oleic acid with methanol. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2023, 136, 2123–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Components | wt.% | Components | wt.% |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 67.53 | CaO | 0.92 |

| Al2O3 | 14.72 | TiO2 | 0.32 |

| MgO | 4.44 | P2O5 | 0.37 |

| Na2O | 3.5 | K2O | 0.2 |

| Fe2O3 | 2.5 | S | 0.98 |

| Sample | Spinel Phase | RC (%) | Crystalline Size (nm) | Sa (m2/g) | Vp (cc/g) | Sp (nm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21.0° | 26.7° | 31.5° | 36.8° | Average | ||||||

| C | - | - | 57.3 | 50.4 | - | - | 52.3 | 9.08 | 0.040 | 17.6 |

| C-CuAl(1) | CuAl2O4 | 100 | 53.9 | 49.2 | 22.3 | 18.2 | 35.9 | 91.1 | 0.171 | 7.5 |

| C-ZnAl(0.5) | ZnAl2O4 | 70 | 42.5 | 47.2 | 13.1 | 17.4 | 30.1 | - | - | - |

| C-ZnAl(1) | ZnAl2O4 | 97 | 38.8 | 43.2 | 8.9 | 9.4 | 25.1 | 46.23 | 0.213 | 18.5 |

| C-ZnAl(1.5) | ZnAl2O4 | 43 | 44.9 | 40.4 | 10.6 | 14.9 | 27.7 | - | - | - |

| C-CuAl(1)-TPA | CuAl2O4 | 74 | 44.9 | 49.8 | 12.5 | 25.4 | 33.2 | 20.85 | 0.094 | 18.0 |

| C-ZnAl(0.5)-TPA | ZnAl2O4 | 69 | 50.5 | 54.4 | 13.3 | 15.8 | 33.5 | 24.7 | 0.083 | 13.4 |

| C-ZnAl(1)-TPA | ZnAl2O4 | 85 | 47.5 | 52.3 | 11.8 | 10.5 | 30.5 | 19.8 | 0.122 | 24.6 |

| C-ZnAl(1.5)-TPA | ZnAl2O4 | 78 | 67.3 | 71.6 | 22.9 | 12.5 | 43.6 | 19.1 | 0.102 | 21.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Qaysi, K.; Rahimnejad, M.; Rahman-Al Ezzi, A.A. Structural and Catalytic Assessment of Clay-Spinel-TPA Nanocatalysts for Biodiesel Synthesis from Oleic Acid. Reactions 2025, 6, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040063

Al-Qaysi K, Rahimnejad M, Rahman-Al Ezzi AA. Structural and Catalytic Assessment of Clay-Spinel-TPA Nanocatalysts for Biodiesel Synthesis from Oleic Acid. Reactions. 2025; 6(4):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040063

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Qaysi, Khalid, M. Rahimnejad, and Ali Abdul Rahman-Al Ezzi. 2025. "Structural and Catalytic Assessment of Clay-Spinel-TPA Nanocatalysts for Biodiesel Synthesis from Oleic Acid" Reactions 6, no. 4: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040063

APA StyleAl-Qaysi, K., Rahimnejad, M., & Rahman-Al Ezzi, A. A. (2025). Structural and Catalytic Assessment of Clay-Spinel-TPA Nanocatalysts for Biodiesel Synthesis from Oleic Acid. Reactions, 6(4), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040063