Photocatalytic and Photo-Fenton-like Degradation of Methylene Blue Using Green-Synthesized Phosphate-Doped ZnO Under Visible LED Light

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Substances

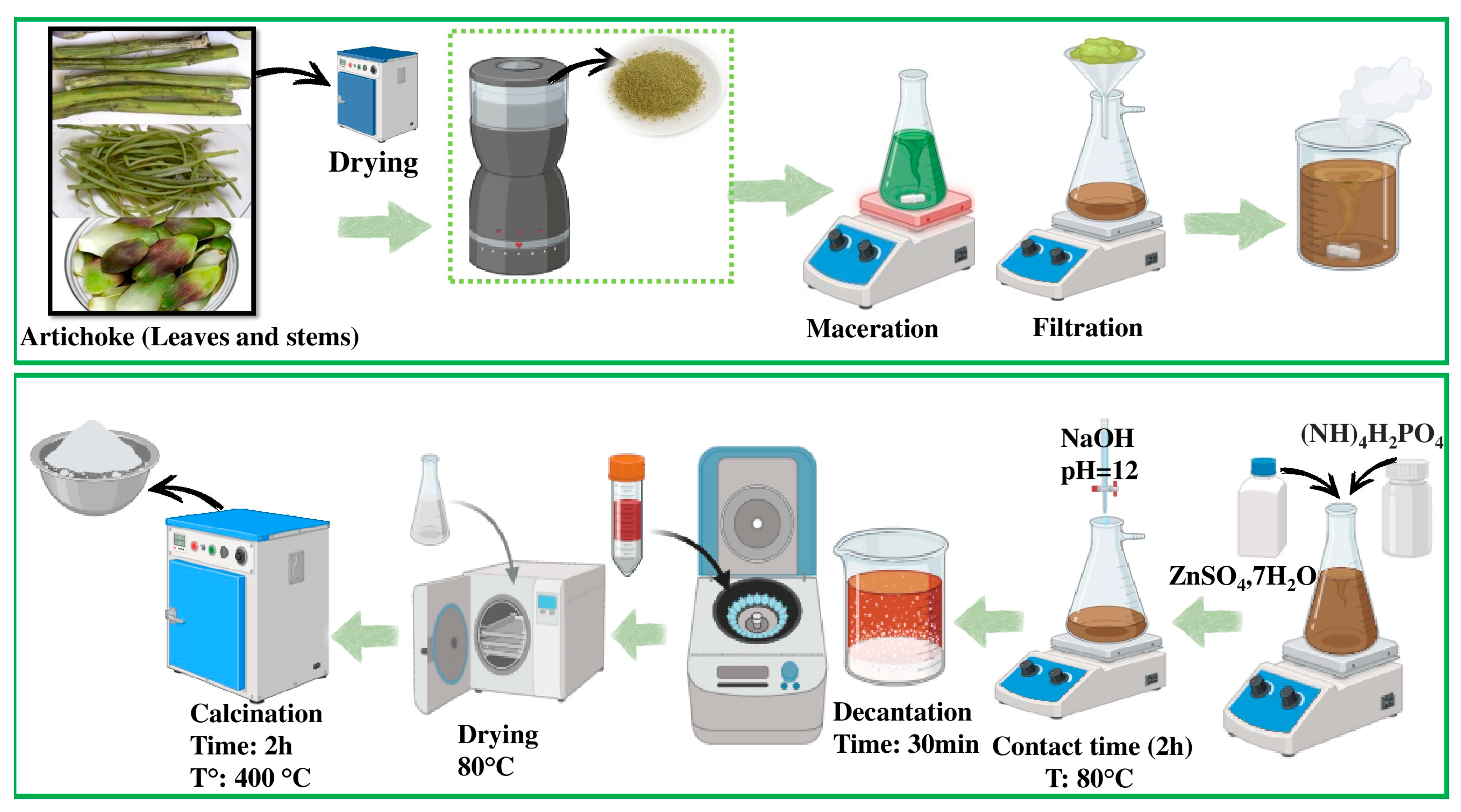

2.2. Preparation Procedure of P-ZnO

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Investigation of Photocatalytic and Photo-Fenton-like Catalytic Properties

2.5. Surface Charge Analysis: pHpzc Measurement

3. Results and Discussion

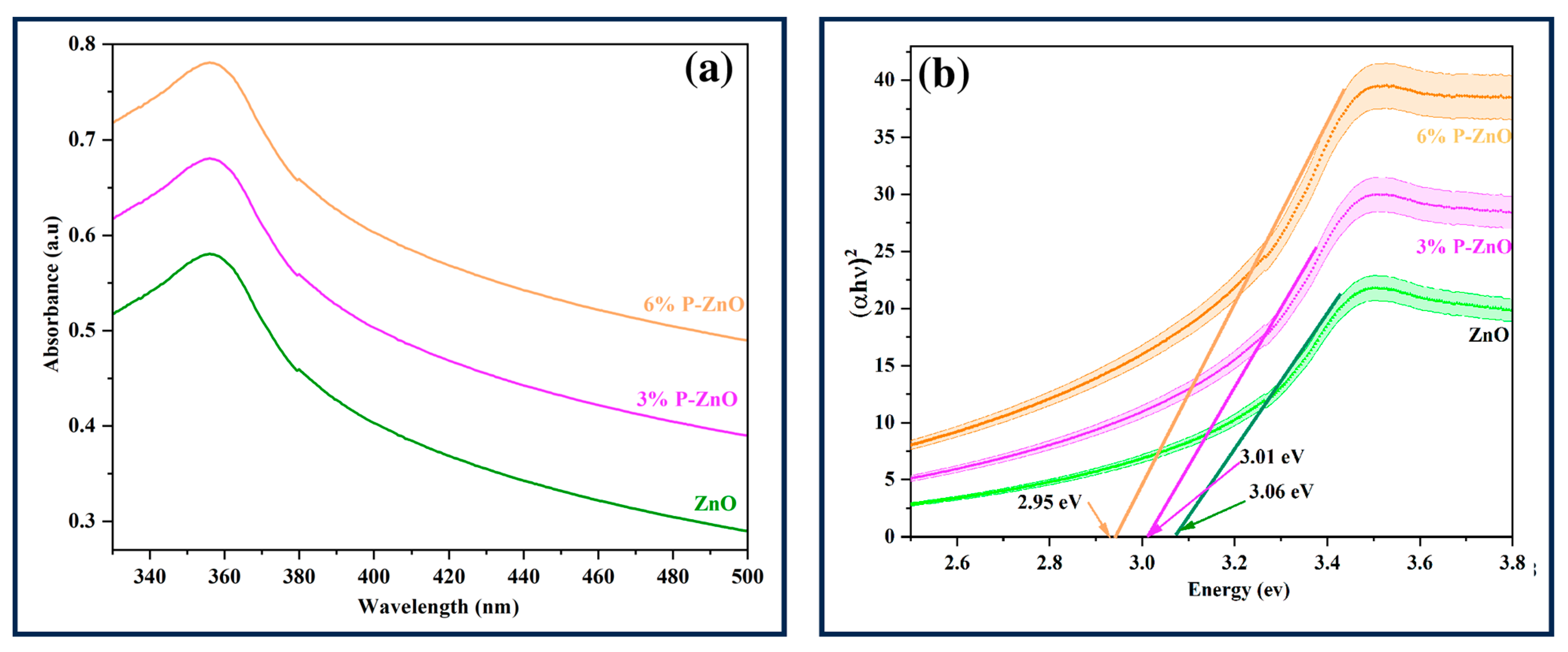

3.1. Optical Properties of Phosphate-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles

3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Profiling

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

3.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy Study

3.5. FTIR Investigation of Functional Groups

3.6. Effect of Phosphorus Doping on the pHpzc of ZnO Nanoparticles

3.7. Catalytic Performance of Phosphorus-Doped ZnO

3.8. Photocatalytic Efficiency of the Photo-Fenton-like Process

3.9. Effect of Catalyst Loading on the Photo-Fenton-like Activity of P-ZnO

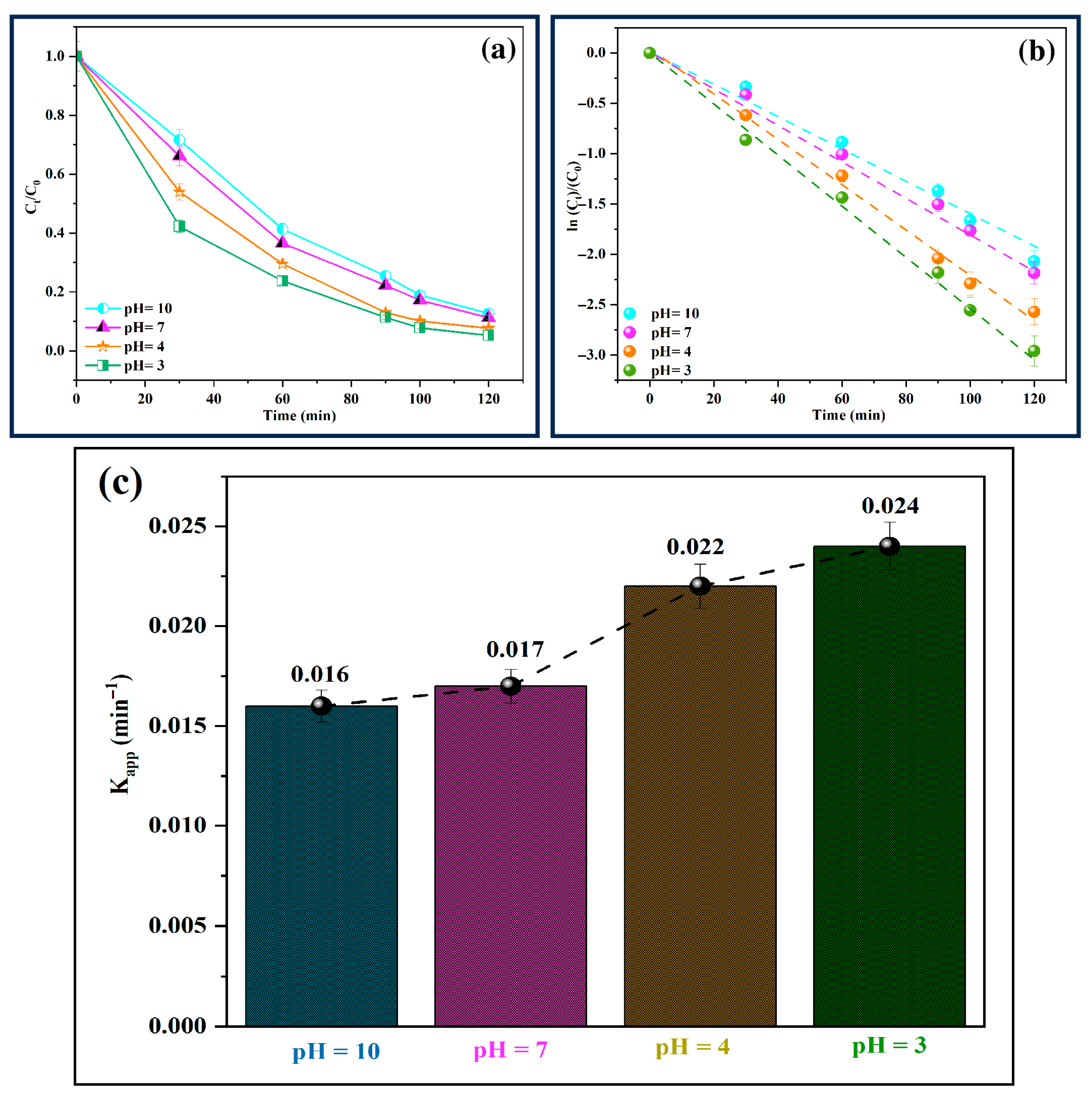

3.10. Effect of pH on the Photo-Fenton-like Degradation of MB

3.11. Impact of the Initial Dye Concentration

3.12. Proposed Mechanism for Photo-Fenton–like Processorm

3.13. Catalyst Durability and Reusability

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du Plessis, A. Persistent Degradation: Global Water Quality Challenges and Required Actions. One Earth 2022, 5, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ali, M.; El Hazzat, M.; Flayou, M.; Moussadik, A.; Belekbir, S.; Sifou, A.; Dahhou, M.; Kacimi, M.; Benzaouak, A.; El Hamidi, A. Advanced Kinetic and Thermodynamic Analysis of Sewage Sludge Combustion: A Study of Non-Isothermal Reaction Mechanisms and Energy Recovery. FirePhysChem 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sathishkumar, K.; Zhang, H.; Saxena, K.K.; Zhang, F.; Naraginti, S.; Anbarasu, K.; Rajendiran, R.; Rajasekar, A.; Guo, X. Frontiers in Environmental Cleanup: Recent Advances in Remediation of Emerging Pollutants from Soil and Water. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 16, 100461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, S.M.; Ray, A.K.; Barghi, S. Water Pollution and Agriculture Pesticide. Clean Technol. 2022, 4, 1088–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkhaya, S.; Harfi, S.E.; Harfi, A.E. Classifications, Properties and Applications of Textile Dyes: A Review. Appl. J. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2017, 3, 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ali, M.; Benzaouak, A.; Tangarfa, M.; Abrouki, Y.; Belekbir, S.; Hazzat, M.E.; El Hamidi, A.; Abdelouahed, L. Multi-Response Optimization of the Adsorption Properties of Activated Carbon Produced from H2SO4 Activated Sludge: Effects of Washing with HCl. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2025, 11, 101219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtaoui, Y.; Ben Ali, M.; Ouakki, M.; El Khattabi, O.; El Azzouzi, N.; Srhir, B. Efficient Adsorption of Methylene Blue onto Raw Olive Pomace from Moroccan Industrial Oil Mills: Linear and Nonlinear Isotherm and Kinetic Modeling with Error Analysis. Next Mater. 2025, 9, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tohamy, R.; Ali, S.S.; Li, F.; Okasha, K.M.; Mahmoud, Y.A.-G.; Elsamahy, T.; Jiao, H.; Fu, Y.; Sun, J. A Critical Review on the Treatment of Dye-Containing Wastewater: Ecotoxicological and Health Concerns of Textile Dyes and Possible Remediation Approaches for Environmental Safety. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 231, 113160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Adhikary, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Roy, D.; Chatterjee, S.; Chakraborty, A.; Banerjee, D.; Ganguly, A.; Nanda, S.; Rajak, P. Contamination of Textile Dyes in Aquatic Environment: Adverse Impacts on Aquatic Ecosystem and Human Health, and Its Management Using Bioremediation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, A.; Gouda, S. Eco-Friendly Dye Removal: Impact of Dyes on Aquatic and Human Health and Sustainable Fungal Treatment Approaches. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 2025, 29, 2733–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ali, M.; Bakhtaoui, Y.; Flayou, M.; El Hazzat, M.; Sifou, A.; Dahhou, M.; Kacimi, M.; Benzaouak, A.; El Hamidi, A. Adsorption of Brilliant Cresyl Blue Using NaOH-Activated Biochar Derived from Sewage Sludge. E3S Web Conf. 2025, 601, 00087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ali, M.; Flayou, M.; Boutarba, Y.; El Youssfi, M.; Bakhtaoui, Y.; El Hazzat, M.; Sifou, A.; Dahhou, M.; Kacimi, M.; Benzaouak, A.; et al. Conversion of Urban Sludge into KOH-Activated Biochar for Methylene Blue Adsorption. Moroc. J. Chem. 2024, 12, 1852–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sadaawy, M.M.; Agib, N.S. Removal of Textile Dyes by Ecofriendly Aquatic Plants From Wastewater: A Review on Plants Species, Mechanisms, and Perspectives. Blue Econ. 2024, 2, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.S.; Teixeira, A.R.; Jorge, N.; Peres, J.A. Industrial Wastewater Treatment by Coagulation–Flocculation and Advanced Oxidation Processes: A Review. Water 2025, 17, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmana, H.; Bellahsen, N.; Pantoja, F.; Hodur, C. Adsorption and Coagulation in Wastewater Treatment—Review. Progress 2021, 17, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahmatkesh, S.; Karimian, M.; Chen, Z.; Ni, B.-J. Combination of Coagulation and Adsorption Technologies for Advanced Wastewater Treatment for Potable Water Reuse: By ANN, NSGA-II, and RSM. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Kansha, Y. Comprehensive Review of Industrial Wastewater Treatment Techniques. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 51064–51097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishat, A.; Yusuf, M.; Qadir, A.; Ezaier, Y.; Vambol, V.; Ijaz Khan, M.; Ben Moussa, S.; Kamyab, H.; Sehgal, S.S.; Prakash, C.; et al. Wastewater Treatment: A Short Assessment on Available Techniques. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 76, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khader, E.H.; Muslim, S.A.; Saady, N.M.C.; Ali, N.S.; Salih, I.K.; Mohammed, T.J.; Albayati, T.M.; Zendehboudi, S. Recent Advances in Photocatalytic Advanced Oxidation Processes for Organic Compound Degradation: A Review. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 318, 100384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, U.; Spahr, S.; Lutze, H.; Wieland, A.; Rüting, S.; Gernjak, W.; Wenk, J. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water and Wastewater Treatment—Guidance for Systematic Future Research. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ali, M.; Benzaouak, A.; Valentino, L.; Moussadik, A.; El Hazzat, M.; Abdelouahed, L.; El Hamidi, A.; Liotta, L.F. Copper-Decorated Biochar Derived from Sludge as Eco-Friendly Nano-Catalyst for Efficient p-Nitrophenol Reduction. Catal. Today 2025, 459, 115421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaya, U.I.; Abdullah, A.H. Heterogeneous Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Contaminants over Titanium Dioxide: A Review of Fundamentals, Progress and Problems. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2008, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Preparations and Applications of Zinc Oxide Based Photocatalytic Materials. Adv. Sens. Energy Mater. 2023, 2, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscetta, M.; Ganguly, P.; Clarizia, L. Solar-Powered Photocatalysis in Water Purification: Applications and Commercialization Challenges. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Zeid, S.; Leprince-Wang, Y. Advancements in ZnO-Based Photocatalysts for Water Treatment: A Comprehensive Review. Crystals 2024, 14, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Mohanty, D.L.; Divya, N.; Bakshi, V.; Mohanty, A.; Rath, D.; Das, S.; Mondal, A.; Roy, S.; Sabui, R. A Critical Review on Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Properties and Biomedical Applications. Intell. Pharm. 2025, 3, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Pathak, S.; Srivastava, A.K.; Prawer, S.; Tomljenovic-Hanic, S. ZnO Nanomaterials: Green Synthesis, Toxicity Evaluation and New Insights in Biomedical Applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 876, 160175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saadony, M.; Fang, G.; Yan, S.; Alkafaas, S.; El Nasharty, M.; Khedr, S.; Hussien, A.; Ghosh, S.; Dladla, M.; Elkafas, S.S.; et al. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Preparation, Characterization, and Biomedical Applications—A Review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 12889–12937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel Olugbenga, O.; Goodness Adeleye, P.; Blessing Oladipupo, S.; Timothy Adeleye, A.; Igenepo John, K. Biomass-Derived Biochar in Wastewater Treatment- a Circular Economy Approach. Waste Manag. Bull. 2024, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Wang, Y.; Conte, A.J.; Zhang, S.; Ryu, J.; Wie, J.J.; Pu, Y.; Davison, B.H.; Yoo, C.G.; Ragauskas, A.J. Applications of Biomass-Derived Solvents in Biomass Pretreatment—Strategies, Challenges, and Prospects. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 368, 128280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Cheng, S. Recent Trends and Advancements in Green Synthesis of Biomass-Derived Carbon Dots. Eng 2024, 5, 2223–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoriello, T.; Mellara, F.; Ruggeri, S.; Ciorba, R.; Ceccarelli, D.; Ciccoritti, R. Artichoke By-Products Valorization for Phenols-Enriched Fresh Egg Pasta: A Sustainable Food Design Project. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-darwesh, M.Y.; Ibrahim, S.S.; Mohammed, M.A. A Review on Plant Extract Mediated Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Biomedical Applications. Results Chem. 2024, 7, 101368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagrán, Z.; Anaya-Esparza, L.M.; Velázquez-Carriles, C.A.; Silva-Jara, J.M.; Ruvalcaba-Gómez, J.M.; Aurora-Vigo, E.F.; Rodríguez-Lafitte, E.; Rodríguez-Barajas, N.; Balderas-León, I.; Martínez-Esquivias, F. Plant-Based Extracts as Reducing, Capping, and Stabilizing Agents for the Green Synthesis of Inorganic Nanoparticles. Resources 2024, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanoja-López, K.A.; Cedeño-Muñoz, J.S.; Rivadeneira-Mendoza, B.F.; Vergara-Romero, A.; Luque, R.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.M. Agricultural Residues to High-Value Nanomaterials: Pathways to Sustainability. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2025, 25, 200243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarou, R.; Brahmia, O.; Haya, S.; Sahmetlioglu, E.; Kılıç Dokan, F.; Hidouri, T. Starch-Assisted Eco-Friendly Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles: Enhanced Photocatalytic, Supercapacitive, and UV-Driven Antioxidant Properties with Low Cytotoxic Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, A.; Siddique, M.; Panchal, S. A Review of Visible-Light-Active Zinc Oxide Photocatalysts for Environmental Application. Catalysts 2025, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raha, S.; Ahmaruzzaman, M. ZnO Nanostructured Materials and Their Potential Applications: Progress, Challenges and Perspectives. Nanoscale Adv. 2022, 4, 1868–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulqodus, A.N.; Abdulrahman, A.F.; Mostafa, S.H.; Kareem, A.A.; Hamad, S.M.; Ahmed, S.M.; Almessiere, M.A.; Shaikhah, D. Green Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles: Effect of pH on Morphology and Photocatalytic Degradation Efficiency. Appl. Phys. A 2025, 131, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, S.; Tian, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, L.; Duan, G.; Yang, W.; Jiang, S. Enhanced Visible Light Photocatalytic Efficiency of La-Doped ZnO Nanofibers via Electrospinning-Calcination Technology. Adv. Powder Mater. 2022, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohzadi, S.; Maleki, A.; Bundschuh, M.; Vahabzadeh, Z.; Johari, S.A.; Rezaee, R.; Shahmoradi, B.; Marzban, N.; Amini, N. Doping Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Nanoparticles with Molybdenum Boosts Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine b (RhB): Particle Characterization, Degradation Kinetics and Aquatic Toxicity Testing. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 385, 122412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Luan, X.; Cui, L.; Lu, X.; Pan, Y.; Jiang, Y. Ag-Doped ZnO Nanocomposites for High-Performance Hydrogen Sensing: Synergistic Enhancement via Structural and Electronic Modulation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 165, 150839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Khan, D.; Al-Anazi, A.; Ahmad, W.; Ullah, I.; Shah, N.S.; Khan, J.A. Non-Metal Doped ZnO and TiO2 Photocatalysts for Visible Light Active Degradation of Pharmaceuticals and Hydrogen Production: A Review. Appl. Catal. O Open 2025, 204, 207043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Xia, C.; Yan, J.; Wang, K.; Wei, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M. Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants via Black Phosphorus-Mediated Electron Transfer in g-C3N4/BiOI: Degradation Mechanisms and Biotoxicity Assessment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aihemaiti, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Qi, K.; Ma, Y.; Tao, K.; Simayi, M.; Kuerban, N. Effective Prevention of Charge Trapping in Red Phosphorus with Nanosized CdS Modification for Superior Photocatalysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, S.; Kumar, V.; Purohit, L.P. Solar Light Driven Enhanced in Photocatalytic Activity of Novel Gd Incorporated ZnO/SnO2 Heterogeneous Nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzarti, Z.; Saadi, H.; Abdelmoula, N.; Hammami, I.; Fernandes Graça, M.P.; Alrasheedi, N.; Louhichi, B.; Seixas De Melo, J.S. Enhanced Dielectric and Photocatalytic Properties of Li-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles for Sustainable Methylene Blue Degradation with Reduced Lithium Environmental Impact. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 47170–47184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, M.A.; Bello, I.T.; Shittu, H.A.; Sivaprakash, P.; Adedokun, O.; Arumugam, S. Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Application of Silver Doped Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles. Clean. Mater. 2022, 3, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyoud, S.H.; Abdullah, C.A.C.; Ashames, A.; Hassan, N.; Yahia, I.S.; Zyoud, A.H.; Zahran, H.Y.; Qamhieh, N.; Makhadmeh, G.N.; AlZoubi, T. Superior Photocatalytic Degradation of Pharmaceuticals and Antimicrobial Features of Iron-Doped Zinc Oxide Sub-Microparticles Synthesized via Laser-Assisted Chemical Bath Technique. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 102875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akir, S.; Barras, A.; Coffinier, Y.; Bououdina, M.; Boukherroub, R.; Omrani, A.D. Eco-Friendly Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles with Different Morphologies and Their Visible Light Photocatalytic Performance for the Degradation of Rhodamine B. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 10259–10265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas-Fuentes, A.; Edith Castellano, L.; Rafael Vilchis-Nestor, A.; Alfredo Luque, P. Sustainable and Environmentally Friendly Synthesis of ZnO Semiconductor Nanoparticles from Bauhinia Forficata Leaves Extract and the Study of Their Photocatalytic and Antibacterial Activity. Clean. Mater. 2024, 13, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Sarvothaman, V.P.; Skillen, N.; Wang, Z.; Rooney, D.W.; Ranade, V.V.; Robertson, P.K.J. Kinetic Modelling of the Photocatalytic Degradation of Diisobutyl Phthalate and Coupling with Acoustic Cavitation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 444, 136494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, A.H.; Mubarak, N.S.A.; Ishak, M.A.M.; Ismail, K.; Nawawi, W.I. Kinetics of Photocatalytic Decolourization of Cationic Dye Using Porous TiO2 Film. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2016, 10, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.; Shahat, A.; El-Didamony, A.; El-Desouky, M.G.; El-Bindary, A.A. Equilibrium, Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies of Adsorption of Cationic Dyes from Aqueous Solution Using ZIF-8. Mor. J. Chem. 2020, 8, 627–637. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmoun, H.B.; Boumediene, M.; Ghenim, A.N.; Da Silva, E.F.; Labrincha, J. Coupling Coagulation–Flocculation–Sedimentation with Adsorption on Biosorbent (Corncob) for the Removal of Textile Dyes from Aqueous Solutions. Environments 2025, 12, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y. Synthesis and Optical Properties of Phosphorus-Doped ZnO Nanocombs. Solid State Commun. 2010, 150, 1911–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed Al-Nidawi, A.J.; Amin Matori, K.; Mohd Zaid, M.H.; Ying Chyi, J.L.; Sin Tee, T.; Sarmani, A.R.; Ahmad Khushaini, M.A.; Md Zain, A.R.; Rahi Mutlage, W. Effect of High Concentration of ZnO on the Structural and Optical Properties of Silicate Glass System. Results Opt. 2024, 14, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, M.; Sharma, P.; Ram, C. Optical, Structural Properties and Photocatalytic Potential of Nd-ZnO Nanoparticles Synthesized by Hydrothermal Method. Results Opt. 2023, 10, 100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzez-Ferndez, J.; Pinz-Moreno, D.D.; Neciosup-Puican, A.A.; Carranza-Oropeza, M.V. Green Method, Optical and Structural Characterization of ZnO Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Leaves Extract of M. Oleifera. J. Renew. Mater. 2022, 10, 833–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony Lilly Grace, M.; Veerabhadra Rao, K.; Anuradha, K.; Judith Jayarani, A.; Arun Kumar, A.; Rathika, A. X-Ray Analysis and Size-Strain Plot of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles by Williamson-Hall. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 92, 1334–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redjili, S.; Ghodbane, H.; Tahraoui, H.; Abdelouahed, L.; Chebli, D.; Ola, M.S.; Assadi, A.A.; Kebir, M.; Zhang, J.; Amrane, A.; et al. Green Innovation: Multifunctional Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Quercus Robur for Photocatalytic Performance, Environmental, and Antimicrobial Applications. Catalysts 2025, 15, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, C.; Mahmud, S.A.; Abdulla, S.M.; Mirzaei, Y. Green Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles Using the Aqueous Extract of Euphorbia Petiolata and Study of Its Stability and Antibacterial Properties. Mor. J. Chem. 2016, 5, 476–484. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, F.; Asghar, M.; Mahmood, K.; Raja, M.Y.A.; Nawaz, A.; Warsi, M.F. Characterization of Phosphorus-Doping in Zinc Oxide Pellets Using Solid State Reaction Method. J. Ovonic Res. 2015, 11, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.S.; Fallert, J.; Lotnyk, A.; Scholz, R.; Pippel, E.; Senz, S.; Kalt, H.; Gösele, U.; Zacharias, M. Growth and Optical Properties of Phosphorus-Doped ZnO Nanowires. Solid State Commun. 2007, 143, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, M.; Aslam, U.; Khalid, B.; Chen, B. OPEN Green Route to Synthesize Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Using Leaf. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polsongkram, D.; Chamninok, P.; Pukird, S.; Chow, L.; Lupan, O.; Chai, G.; Khallaf, H.; Park, S.; Schulte, A. Effect of Synthesis Conditions on the Growth of ZnO Nanorods via Hydrothermal Method. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2008, 403, 3713–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifácio, M.A.R.; Lira, H.D.L.; Neiva, L.S.; Kiminami, R.H.G.A.; Gama, L. Nanoparticles of ZnO Doped With Mn: Structural and Morphological Characteristics. Mat. Res. 2017, 20, 1044–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahy, B.; Bahadur, D. P-Type Phosphorus Doped ZnO Nanostructures: An Electrical, Optical, and Magnetic Properties Study. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghoul, J.; All, N.A. Synthesis and characterizations of phosphorus doped ZnO nanoparticles. J. Optoelectron. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 14, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddahi, P.; Shahtahmasebi, N.; Kompany, A.; Mashreghi, M.; Safaee, S.; Roozban, F. Effect of Doping on Structural and Optical Properties of ZnO Nanoparticles: Study of Antibacterial Properties. Mater. Sci.-Pol. 2014, 32, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, S.; Ghosh, O.S.N.; Sathishkumar, S.; Jayaramudu, J.; Ray, S.S.; Viswanath, A.K. Investigation of Physicochemical Properties of Ag Doped ZnO Nanoparticles Prepared by Chemical Route. Appl. Sci. Lett. 2015, 1, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, P.G.; Velu, A.S. Synthesis, Structural and Optical Properties of Pure ZnO and Co Doped ZnO Nanoparticles Prepared by the Co-Precipitation Method. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 2016, 10, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffari, R.; Shariatinia, Z.; Jourshabani, M. Synthesis and Photocatalytic Degradation Activities of Phosphorus Containing ZnO Microparticles under Visible Light Irradiation for Water Treatment Applications. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 259, 113902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Dassi, R.; Chamam, B.; Méricq, J.P.; Heran, M.; Faur, C.; El Mir, L.; Tizaoui, C.; Trabelsi, I. Pb Doped ZnO Nanoparticles for the Sorption of Reactive Black 5 Textile Azo Dye. Water Sci. Technol. 2020, 82, 2576–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etefa, H.F.; Nemera, D.J.; Etefa, K.T.; Kumar, E.R. Evaluation of Physicochemical Properties of Zinc Oxide and Indium-Tin Oxide Nanoparticles for Photocatalysis and Biomedical Activities. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2024, 67, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayu, D.G.; Gea, S.; Andriayani; Telaumbanua, D.J.; Piliang, A.F.R.; Harahap, M.; Yen, Z.; Goei, R.; Tok, A.I.Y. Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Using N-Doped ZnO/Carbon Dot (N-ZnO/CD) Nanocomposites Derived from Organic Soybean. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 14965–14984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkahoui, Y.; Abahdou, F.-Z.; Ben Ali, M.; Alahiane, S.; Elhabacha, M.; Boutarba, Y.; El Hajjaji, S. Photocatalytic and Photo-Fenton-like Degradation of Cationic Dyes Using SnFe2O4/g-C3N4 Under LED Irradiation: Optimization by RSM-BBD and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs). Reactions 2025, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennasraoui, B.; Ighnih, H.; Haounati, R.; Rhaya, M.; Malekshah, R.E.; Alahiane, S.; Ouachtak, H.; Jada, A.; Addi, A.A. Enhanced Solar-Driven Photocatalytic Decomposition of Ciprofloxacin Antibiotic and Orange G Dye Using Innovative g-C3N4/BiOCl/Ag2MoO4 Nanocomposites: Experimental and Monte Carlo Simulation Studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 429, 127476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhaya, M.; Ighnih, H.; Oualid, H.A.; Ennasraoui, B.; Haounati, R.; Ouachtak, H.; Jada, A.; Addi, A.A. Synthesis of Ag3PO4/g-C3N4/CuO Ternary Nanocomposite for Photocatalytic Reduction of Cr(VI) and Photocatalytic Degradation of Orange G Dye. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1338, 142333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, J.P.A.; Gross, E.C.; Sears, T.J.; Hall, G.E. Investigating the Photodissociation of H2O2 Using Frequency Modulation Laser Absorption Spectroscopy to Monitor Radical Products. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2018, 711, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigarroa-Mayorga, O.E. Enhancement of Photocatalytic Activity in ZnO NWs Array Due to Fe2O3 NPs Electrodeposited on the Nanowires Surface: The Role of ZnO-Fe2O3 Interface. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.U.; Latief, U.; Ahmad, I.; Khan, Z.; Ali, J.; Khan, M.S. Novel NiO/ZnO/Fe2O3 White Light-Emitting Phosphor: Facile Synthesis, Color-Tunable Photoluminescence and Robust Photocatalytic Activity. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 23137–23152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nami, M.; Sheibani, S.; Rashchi, F. Photocatalytic Performance of Coupled Semiconductor ZnO–CuO Nanocomposite Coating Prepared by a Facile Brass Anodization Process. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2021, 135, 106083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mehta, S.K.; Kansal, S.K. N Doped ZnO/C-Dots Nanoflowers as Visible Light Driven Photocatalyst for the Degradation of Malachite Green Dye in Aqueous Phase. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 699, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drhimer, F.; Rahmani, M.; Regraguy, B.; El Hajjaji, S.; Mabrouki, J.; Amrane, A.; Fourcade, F.; Assadi, A.A. Treatment of a Food Industry Dye, Brilliant Blue, at Low Concentration Using a New Photocatalytic Configuration. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyoud, S.H.; Yahia, I.S.; Shahwan, M.; Zyoud, A.H.; Zahran, H.Y.; Abdel-wahab, M.S.; Daher, M.G.; Nasor, M.; Makhadmeh, G.N.; Hassan, N.; et al. Fast and Excellent Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Methylene Blue Using Silver-Doped Zinc Oxide Submicron Structures under Blue Laser Irradiation. Crystals 2023, 13, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasmari, A.; Alresheedi, N.; Alzahrani, M.; Aldosari, F.; Ghasemi, M.; Ismail, A.; Aboraia, A. High-Performance Photocatalytic Degradation—A ZnO Nanocomposite Co-Doped with Gd: A Systematic Study. Catalysts 2024, 14, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lattice Parameters | ZnO | P (3 wt%) Doped ZnO | P (6 wt%) Doped ZnO |

|---|---|---|---|

| a (Å) | 3.220521 | 3.249342 | 3.252586 |

| b (Å) | 3.220521 | 3.249342 | 3.252586 |

| c (Å) | 5.194973 | 5.205055 | 5.207613 |

| c/a | 1.6130846 | 1.6018797 | 1.6010685 |

| Alpha (°) | 90.000000 | 90.000000 | 90.000000 |

| Beta (°) | 90.000000 | 90.000000 | 90.000000 |

| Gamma (°) | 120.000000 | 120.000000 | 120.000000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nehhal, S.; Ben Ali, M.; Abrouki, Y.; Ofqir, K.; Elkahoui, Y.; Labjar, N.; Nasrellah, H.; El Hajjaji, S. Photocatalytic and Photo-Fenton-like Degradation of Methylene Blue Using Green-Synthesized Phosphate-Doped ZnO Under Visible LED Light. Reactions 2025, 6, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040064

Nehhal S, Ben Ali M, Abrouki Y, Ofqir K, Elkahoui Y, Labjar N, Nasrellah H, El Hajjaji S. Photocatalytic and Photo-Fenton-like Degradation of Methylene Blue Using Green-Synthesized Phosphate-Doped ZnO Under Visible LED Light. Reactions. 2025; 6(4):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040064

Chicago/Turabian StyleNehhal, Soukaina, Majda Ben Ali, Younes Abrouki, Khalid Ofqir, Yassine Elkahoui, Najoua Labjar, Hamid Nasrellah, and Souad El Hajjaji. 2025. "Photocatalytic and Photo-Fenton-like Degradation of Methylene Blue Using Green-Synthesized Phosphate-Doped ZnO Under Visible LED Light" Reactions 6, no. 4: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040064

APA StyleNehhal, S., Ben Ali, M., Abrouki, Y., Ofqir, K., Elkahoui, Y., Labjar, N., Nasrellah, H., & El Hajjaji, S. (2025). Photocatalytic and Photo-Fenton-like Degradation of Methylene Blue Using Green-Synthesized Phosphate-Doped ZnO Under Visible LED Light. Reactions, 6(4), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040064