Optimized RT-DETRv2 Deep Learning Model for Automated Assessment of Tartary Buckwheat Germination and Pretreatment Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

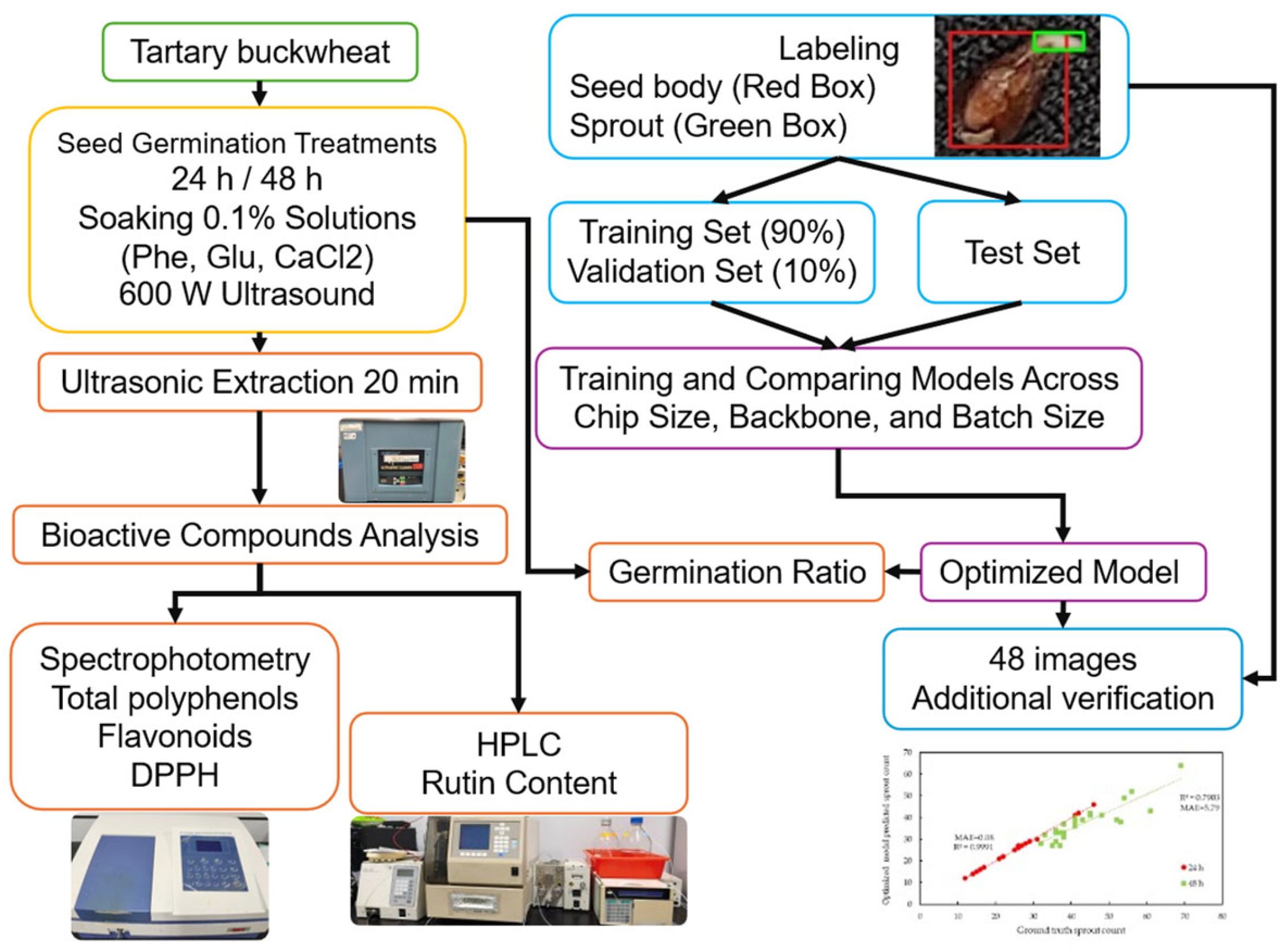

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Germinated Tartary Buckwheat with Various Soaking Solutions

2.2. Analytical Methods for Dried Germinated Tartary Buckwheat

2.2.1. Ultrasonic Extraction

2.2.2. Total Polyphenol Content Determination

2.2.3. Flavonoid Content Determination

2.2.4. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity Determination

2.2.5. Determination of Rutin Content

2.3. Deep Learning-Based Germination Ratio Assessment

2.3.1. Imaging of Germinated Buckwheat Seeds and Sample Labeling

2.3.2. Deep Learning Models

2.4. Germination Ratio Calculation

2.5. Accuracy Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

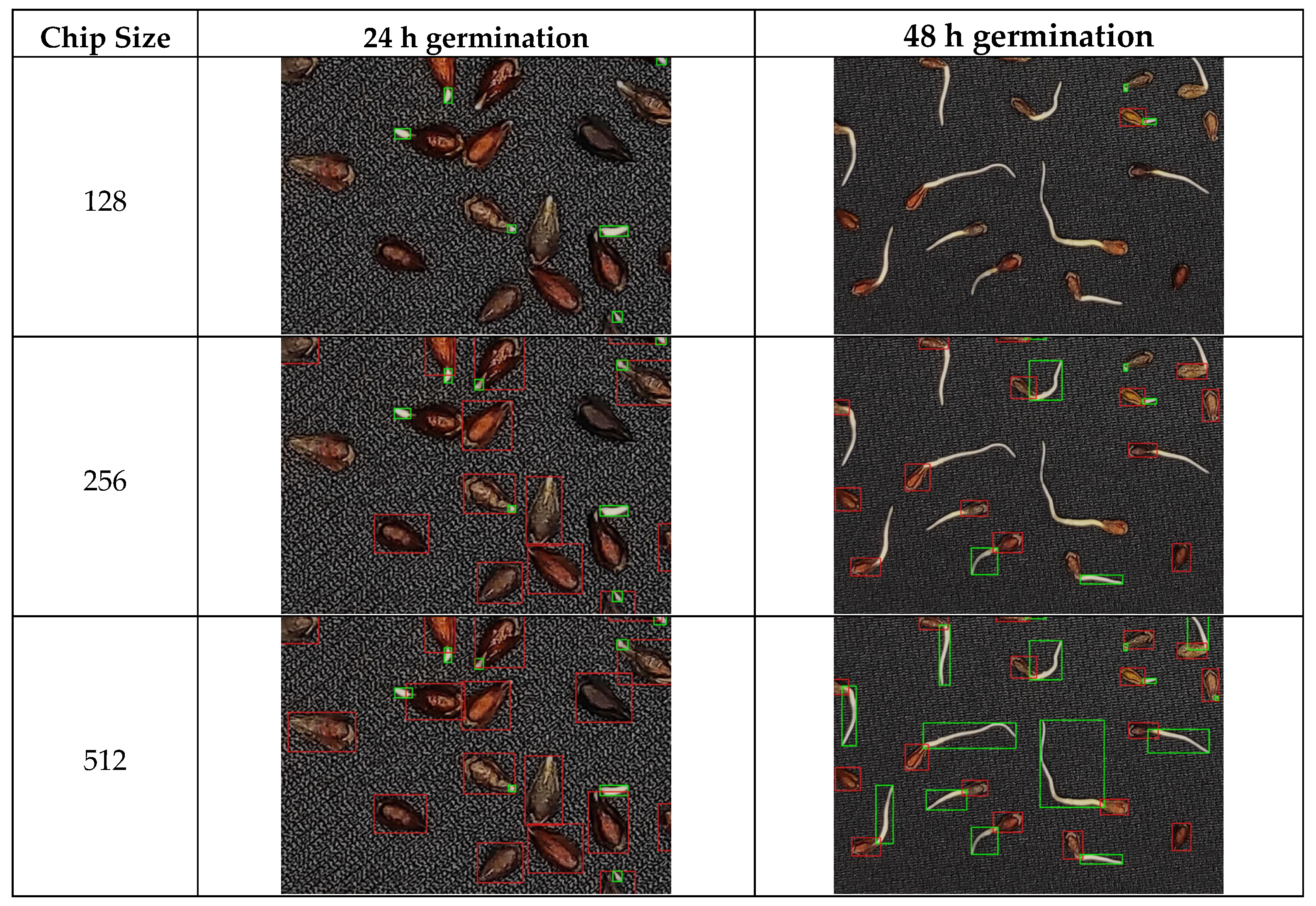

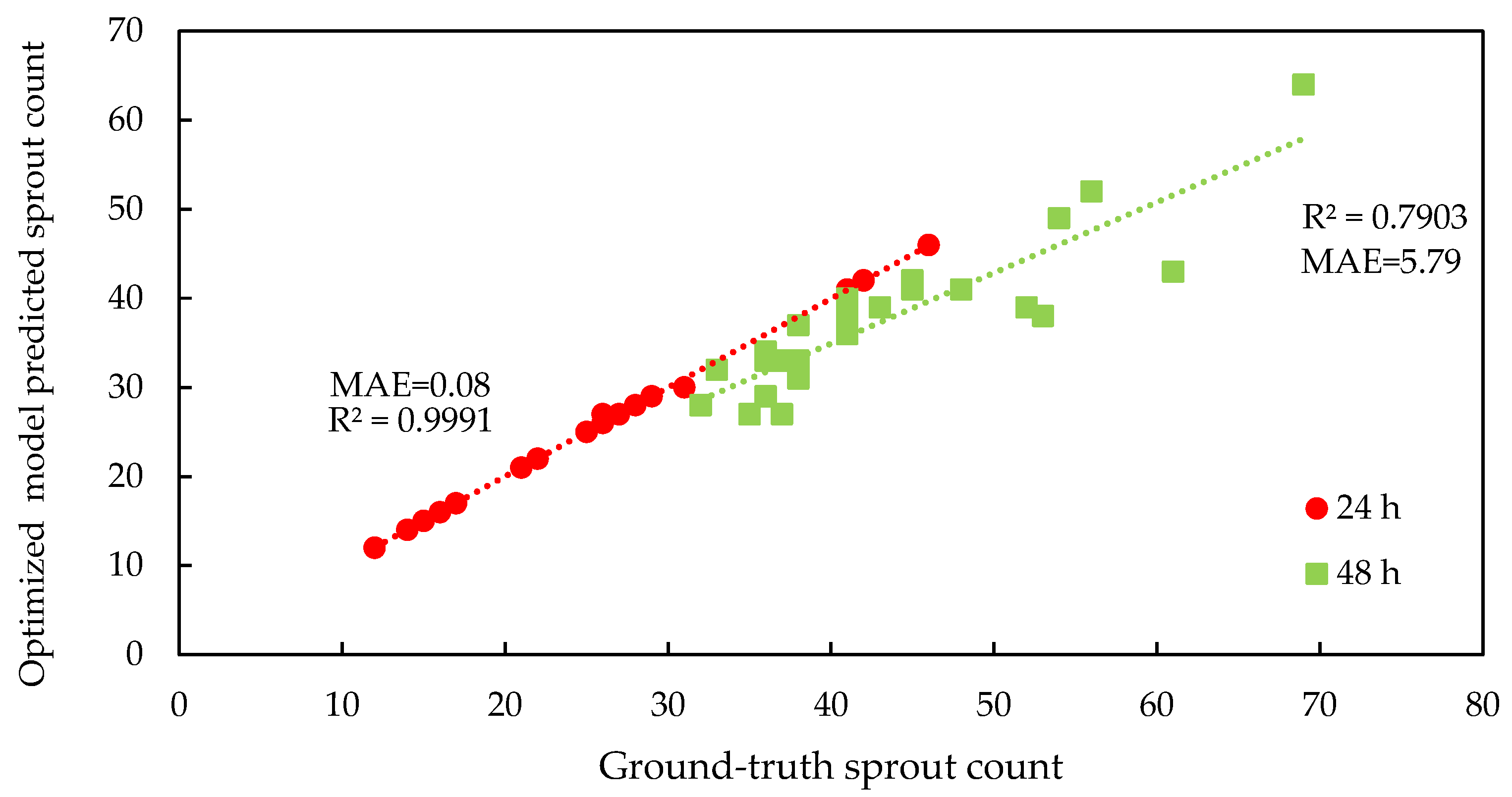

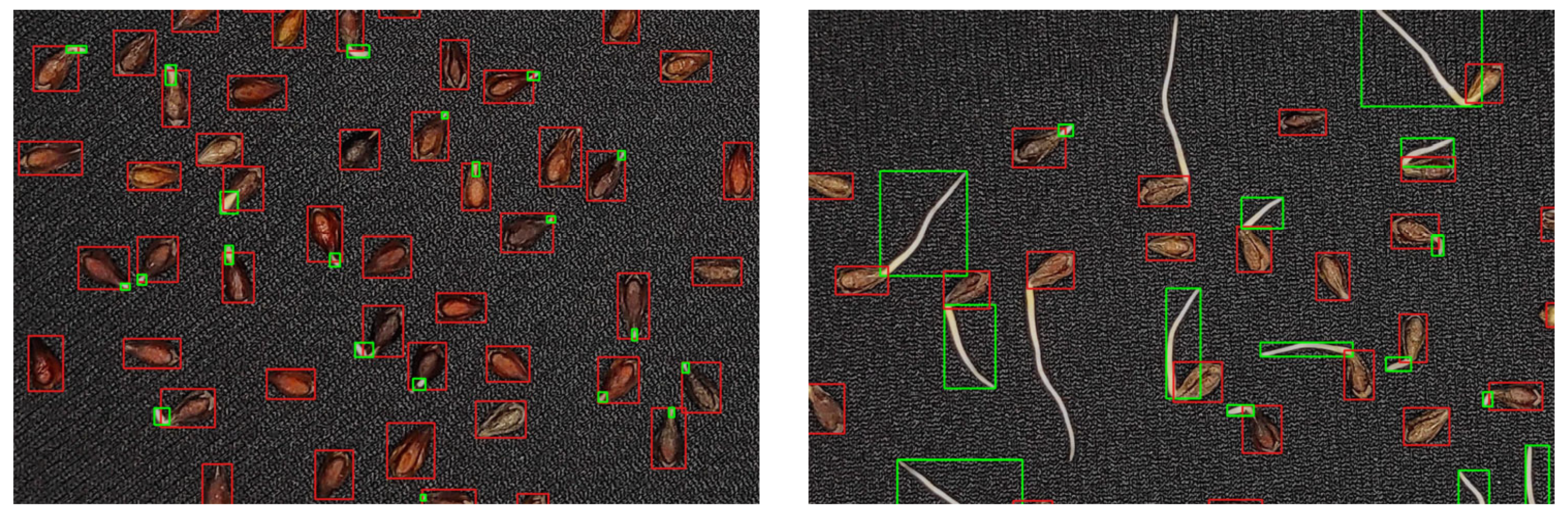

3.1. Deep Learning Model Performance and Parameter Optimization

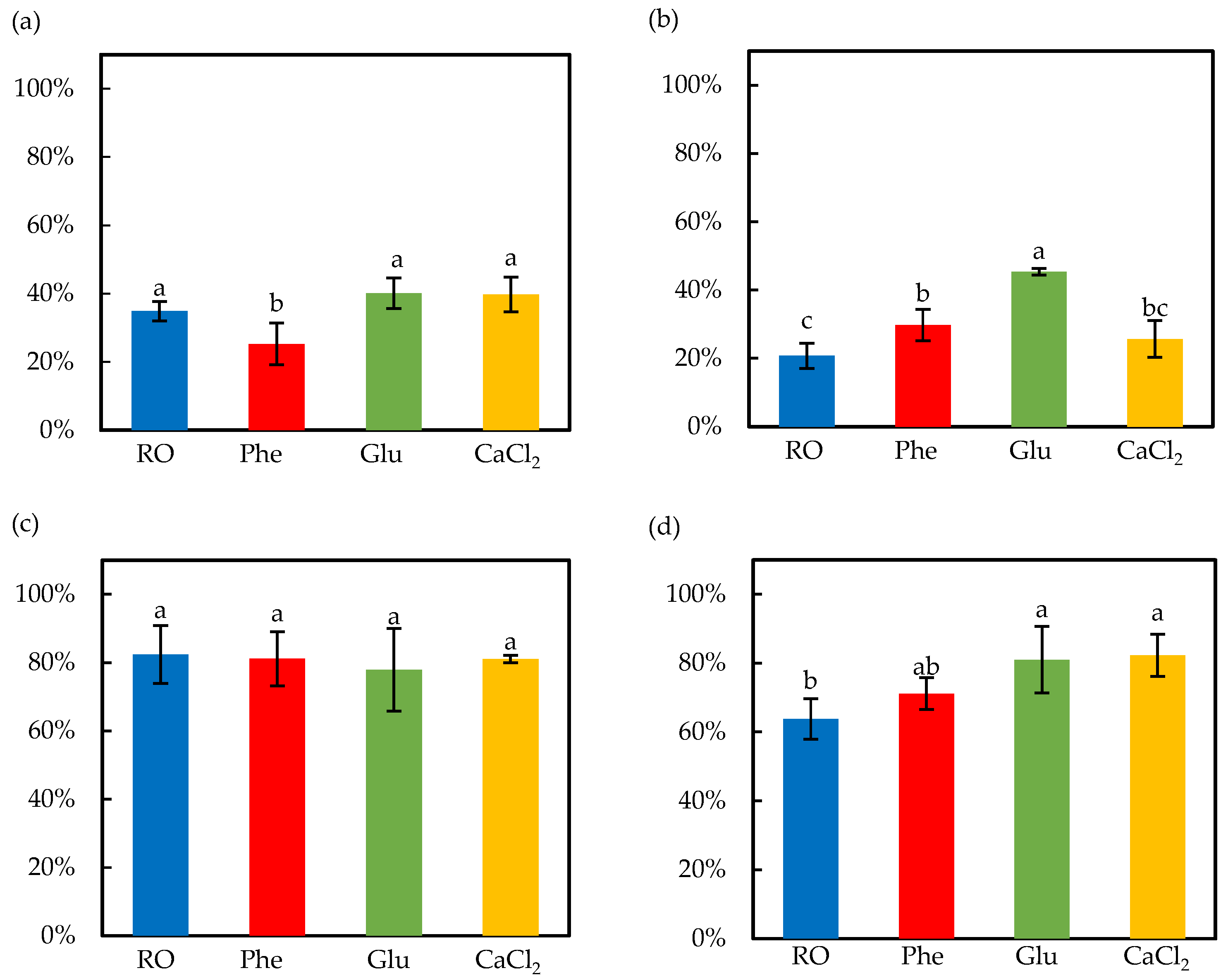

3.2. Effect of Soaking and Ultrasound Treatment on Germination Ratio and Bioactive Compounds

4. Discussion

4.1. Optimization of the RT-DETRv2 Model for Seed and Sprout Detection

4.2. Effects of Pretreatments on Germination and Bioactive Compounds

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonafaccia, G.; Marocchini, M.; Kreft, I. Composition and technological properties of the flour and bran from common and tartary buckwheat. Food Chem. 2003, 80, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamaratskaia, G.; Gerhardt, K.; Knicky, M.; Wendin, K. Buckwheat: An underutilized crop with attractive sensory qualities and health benefits. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 12303–12318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Bian, Z.; Wang, S. Effects of different treatments on the germination, enzyme activity, and nutrient content of buckwheat. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 26, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bian, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L. Effects of ultrasonic waves, microwaves, and thermal stress treatment on the germination of Tartary buckwheat seeds. J. Food Process Eng. 2020, 43, e13494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milivojević, M.; Ripka, Z.; Petrović, T. ISTA rules changes in seed germination testing at the beginning of the 21st century. J. Process. Energy Agric. 2018, 22, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Fan, Q.; Tian, L.; Jiang, H.; Wang, C.; Fu, X.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Evaluation of cucumber seed germination vigor under salt stress environment based on improved YOLOv8. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1447346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-F.; Su, W.-H. The application of deep learning in the whole potato production Chain: A Comprehensive review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, B.; Kang, X.; Ding, Y. Review of Weed Detection Methods Based on Computer Vision. Sensors 2021, 21, 3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Zhou, L.; Pu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Qi, H.; Zhao, Y. Application of deep learning for high-throughput phenotyping of seed: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehoshtan, Y.; Carmon, E.; Yaniv, O.; Ayal, S.; Rotem, O. Robust seed germination prediction using deep learning and RGB image data. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, M.; Mittal, P. A Systematic Review of Deep Learning-Based Object Detection in Agriculture: Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 84, 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 107984–108011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Wang, N.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Bian, Z. Effects of microwave and exogenous l-phenylalanine treatment on phenolic constituents, antioxidant capacity and enzyme inhibitory activity of Tartary buckwheat sprouts. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 32, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, U.; Sung, J.; Lee, H.; Heo, H.; Jeong, H.S.; Lee, J. Effect of calcium chloride and sucrose on the composition of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activities in buckwheat sprouts. Food Chem. 2020, 312, 126075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-Y.; Tang, C.-Y. Determination of total phenolic and flavonoid contents in selected fruits and vegetables, as well as their stimulatory effects on mouse splenocyte proliferation. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.T.; Pao, C.C.; Wu, S.T.; Chang, C.Y. Effect of different germination conditions on antioxidative properties and bioactive compounds of germinated brown rice. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 608761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreft, I.; Fabjan, N.; Yasumoto, K. Rutin content in buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench) food materials and products. Food Chem. 2006, 98, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen BoHan, C.B.; Chen SuDer, C.S. Microwave extraction of polysaccharides and triterpenoids from solid-state fermented products of Poria cocos. Taiwan. J. Agric. Chem. Food Sci. 2013, 51, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarez, R.D. Faster R–CNN, RetinaNet and Single Shot Detector in different ResNet backbones for marine vessel detection using cross polarization C-band SAR imagery. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2024, 36, 101297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krois, J.; Schneider, L.; Schwendicke, F. Impact of Image Context on Deep Learning for Classification of Teeth on Radiographs. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cira, C.-I.; Manso-Callejo, M.-Á.; Alcarria, R.; Iturrioz, T.; Arranz-Justel, J.-J. Insights into the effects of tile size and tile overlap levels on semantic segmentation models trained for road surface area extraction from aerial orthophotography. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskar, N.S.; Mudigere, D.; Nocedal, J.; Smelyanskiy, M.; Tang, P.T.P. On large-batch training for deep learning: Generalization gap and sharp minima. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.04836. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, T.; Chu, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Chu, W.; Chen, J.; Ling, H. CBNet: A Composite Backbone Network Architecture for Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 6893–6906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ma, K.; Zhang, D.; Song, S.; An, X. Classification of soybean seeds based on RGB reconstruction of hyperspectral images. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, G.; Yersaiyiti, H.; Liu, Y.; Cui, J.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; He, X. Modeling analysis on germination and seedling growth using ultrasound seed pretreatment in switchgrass. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Germination Time (h) | Chip Size | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 128 | 0.9223 | 0.2257 | 0.3626 |

| 256 | 0.9747 | 0.9145 | 0.9436 | |

| 512 | 0.964 | 0.9869 | 0.9754 | |

| 48 | 128 | 0.8033 | 0.0655 | 0.1211 |

| 256 | 0.9899 | 0.6524 | 0.7865 | |

| 512 | 0.9929 | 0.9318 | 0.9614 |

| Germination Time (h) | Epoch | Backbone | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 20 | ResNet-18 | 0.9891 | 0.9727 | 0.9808 |

| 60 | ResNet-18 | 0.9845 | 0.9834 | 0.9840 | |

| 100 | ResNet-18 | 0.9834 | 0.9869 | 0.9852 | |

| 20 | ResNet-101 | 0.9640 | 0.9869 | 0.9754 | |

| 60 | ResNet-101 | 0.9596 | 0.9881 | 0.9737 | |

| 100 | ResNet-101 | 0.9617 | 0.9846 | 0.9730 | |

| 48 | 20 | ResNet-18 | 0.9957 | 0.9278 | 0.9606 |

| 60 | ResNet-18 | 0.9986 | 0.9305 | 0.9633 | |

| 100 | ResNet-18 | 0.9971 | 0.9305 | 0.9627 | |

| 20 | ResNet-101 | 0.9929 | 0.9318 | 0.9614 | |

| 60 | ResNet-101 | 0.9971 | 0.9332 | 0.9641 | |

| 100 | ResNet-101 | 0.9971 | 0.9291 | 0.9619 |

| Germination Time (h) | Batch Size | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 1 | 0.9927 | 0.9679 | 0.9802 |

| 2 | 0.9903 | 0.9751 | 0.9826 | |

| 4 | 0.9916 | 0.9798 | 0.9857 | |

| 8 | 0.9891 | 0.9727 | 0.9808 | |

| 16 | 0.9843 | 0.9703 | 0.9773 | |

| 48 | 1 | 0.9913 | 0.9184 | 0.9535 |

| 2 | 1.0000 | 0.9305 | 0.9640 | |

| 4 | 0.9986 | 0.9278 | 0.9619 | |

| 8 | 0.9957 | 0.9278 | 0.9606 | |

| 16 | 0.9830 | 0.9265 | 0.9539 |

| Germination Time (h) | Batch Size | Backbone | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 2 | ResNet-18 | 0.9903 | 0.9751 | 0.9826 |

| 2 | ResNet-34 | 0.9952 | 0.9857 | 0.9905 | |

| 2 | ResNet-50 | 0.9845 | 0.9798 | 0.9821 | |

| 2 | ResNet-101 | 0.9810 | 0.9810 | 0.9810 | |

| 8 | ResNet-18 | 0.9891 | 0.9727 | 0.9808 | |

| 8 | ResNet-34 | 0.9976 | 0.9941 | 0.9958 | |

| 8 | ResNet-50 | 0.9728 | 0.9786 | 0.9757 | |

| 8 | ResNet-101 | 0.9640 | 0.9869 | 0.9754 | |

| 48 | 2 | ResNet-18 | 1.0000 | 0.9305 | 0.9640 |

| 2 | ResNet-34 | 0.9957 | 0.9305 | 0.9620 | |

| 2 | ResNet-50 | 0.9971 | 0.9332 | 0.9641 | |

| 2 | ResNet-101 | 0.9986 | 0.9305 | 0.9633 | |

| 8 | ResNet-18 | 0.9957 | 0.9278 | 0.9606 | |

| 8 | ResNet-34 | 0.9943 | 0.9291 | 0.9606 | |

| 8 | ResNet-50 | 0.9901 | 0.9318 | 0.9601 | |

| 8 | ResNet-101 | 0.9929 | 0.9318 | 0.9614 |

| Germination Time (h) | Soaking Solution | Total Polyphenols (mg GAE/g) | Total Flavonoids (mg QCE/g) | Scavenging DPPH (%) | Rutin (mg/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | N | 3.52 ± 0.16 d | 2.20 ± 0.19 c | 65.13 ± 0.08 h | 3.07 ± 0.04 e | |

| RO | 4.15 ± 0.35 ab | 2.59 ± 0.21 ab | 73.65 ± 0.70 g | 3.40 ± 0.05 b | ||

| Glu | 3.96 ± 0.20 bc | 2.74 ± 0.29 a | 81.54 ± 0.08 b | 2.98 ± 0.03 f | ||

| Phe | 3.88 ± 0.17 bcd | 2.57 ± 0.12 ab | 80.57 ± 0.39 c | 3.29 ± 0.06 c | ||

| CaCl2 | 4.35 ± 0.12 a | 2.63 ± 0.11 ab | 85.14 ± 0.05 a | 3.48 ± 0.05 a | ||

| 48 | RO | 3.77 ± 0.15 cd | 2.41 ± 0.13 bc | 78.36 ± 0.12 d | 3.14 ± 0.09 g | |

| Glu | 3.76 ± 0.10 cd | 2.64 ± 0.02 ab | 78.96 ± 0.20 d | 3.24 ± 0.02 d | ||

| Phe | 3.64 ± 0.25 cd | 2.42 ± 0.14 bc | 76.20 ± 0.36 f | 2.81 ± 0.07 g | ||

| CaCl2 | 2.49 ± 0.25 e | 1.90 ± 0.06 d | 75.41 ± 0.28 e | 2.22 ± 0.05 h | ||

| Germination Time (h) | Soaking Solution | Total Polyphenols (mg GAE/g) | Total Flavonoids (mg QCE/g) | Scavenging DPPH (%) | Rutin (mg/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | N | 3.52 ± 0.16 e | 2.20 ± 0.19 d | 65.13 ± 0.08 g | 3.07 ± 0.04 d | |

| RO + US | 4.77 ± 0.13 c | 3.10 ± 0.12 a | 78.33 ± 0.05 e | 3.61 ± 0.05 a | ||

| Glu + US | 5.39 ± 0.38 b | 3.10 ± 0.42 a | 78.22 ± 0.08 e | 3.24 ± 0.02 c | ||

| Phe + US | 4.90 ± 0.12 c | 2.72 ± 0.20 bc | 83.91 ± 0.08 a | 3.47 ± 0.19 b | ||

| CaCl2 + US | 6.42 ± 0.39 a | 2.80 ± 0.11 ab | 81.64 ± 0.12 c | 3.65 ± 0.02 a | ||

| 48 | RO + US | 3.77 ± 0.11 e | 2.45 ± 0.09 cd | 80.20 ± 0.21 d | 3.25 ± 0.03 c | |

| Glu + US | 3.61 ± 0.24 e | 2.17 ± 0.11 d | 82.17 ± 0.21 b | 2.96 ± 0.01 d | ||

| Phe + US | 3.88 ± 0.13 e | 2.11 ± 0.05 d | 75.99 ± 0.40 f | 2.59 ± 0.05 e | ||

| CaCl2 + US | 4.24 ± 0.11 d | 2.12 ± 0.09 d | 81.41 ± 0.24 c | 2.50 ± 0.01 e | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, J.-D.; Chung, C.-H.; Lai, H.-Y.; Chen, S.-D. Optimized RT-DETRv2 Deep Learning Model for Automated Assessment of Tartary Buckwheat Germination and Pretreatment Evaluation. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120414

Lin J-D, Chung C-H, Lai H-Y, Chen S-D. Optimized RT-DETRv2 Deep Learning Model for Automated Assessment of Tartary Buckwheat Germination and Pretreatment Evaluation. AgriEngineering. 2025; 7(12):414. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120414

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Jian-De, Chih-Hsin Chung, Hsiang-Yu Lai, and Su-Der Chen. 2025. "Optimized RT-DETRv2 Deep Learning Model for Automated Assessment of Tartary Buckwheat Germination and Pretreatment Evaluation" AgriEngineering 7, no. 12: 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120414

APA StyleLin, J.-D., Chung, C.-H., Lai, H.-Y., & Chen, S.-D. (2025). Optimized RT-DETRv2 Deep Learning Model for Automated Assessment of Tartary Buckwheat Germination and Pretreatment Evaluation. AgriEngineering, 7(12), 414. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120414