Abstract

A reliable protocol for comprehensive rice yield data management was established to overcome the heterogeneity and inconsistency inherent in using diverse data sources, measurement conditions, and units. This methodology defines systematic routines for data collection, cleansing, calibration, homogenization, analysis, and visualization. Data were collected over an eight-year period from various yield monitors across extensive cultivated areas within the Axios River Plain, Greece. The protocol relies on a Geographic Information System (GIS) to ensure high data integrity. Following calibration against in-situ weighing records, the data accuracy was confirmed as consistently high, ranging between 91.7% and 96.6% annually. Post-processing revealed a critical finding: the within-field yield variability (approx. 8.6%) was significantly lower than the inherent variability of underlying environmental factors (soil and spectral properties (33–35%)), indicating successful resource management by the farmers. Comparative analysis demonstrated that farms employing site-specific fertilization achieved significantly higher average yields (9.87 t/ha) compared to those using conventional, uniform fertilization (9.11 t/ha). The resulting calibrated yield maps are communicated via a web-based Farm Management Information System (FMIS). The established protocol has since been fully integrated into a commercial precision agriculture service, underscoring its practical efficiency and operational value.

1. Introduction

1.1. Generic

The evolution of agricultural monitoring systems reflects a broader shift toward data-driven farm management. Traditionally, crop yield was monitored very coarsely, relying on simple volume or bulk weight measurements recorded when the commodity was delivered to the buyer, such as a weighed wagon or truckload. Over time, measurement systems have transitioned from these volume-based approaches to more precise weight-based mechanisms. Currently, the most advanced method involves yield monitors, which are integrated into harvesting equipment to continuously estimate the flow of the commodity. These monitors merge flow estimates with crucial supplementary sensor data, such as Global Positioning System (GPS) location and moisture content, to calculate yield on the go and generate valuable spatial data [1].

1.2. The Role of Yield Monitoring in Precision Agriculture

Yield monitoring systems have become a cornerstone of precision agriculture (PA), which is defined as a management practice that meets crop needs through differential applications based on location, time, and processes [2]. The market segment for yield monitoring has grown substantially, highlighting its importance, and reportedly accounted for the largest share of the precision agriculture industry, representing over 42% in 2024 [3]. These systems are now widely available for major global crops, including grains like corn, wheat, and oats, as well as soybeans, cotton, and sugarcane. However, for several other crops—such as peanuts, potatoes, forages, and fruits—the development of robust, commercially available yield monitoring systems remains an active area of research, with many solutions still requiring further field validation and calibration protocols to achieve the accuracy levels of grain monitors [4]. The central benefit of implementing site-specific management techniques, such as adjusting seed rates, pesticide applications, fertilizers, and tillage, is the ability to know the precise yield at every location within a field [5]. This foundational knowledge enables data-driven decision-making, where, for instance, site-specific fertilization can lead to a more efficient use of nutrients, potentially reducing nutrient runoff and greenhouse gas emissions, an increasingly important topic in modern sustainable agriculture [6].

1.3. Data Accuracy and Management Challenges

Yield monitors operate by recording the mass of harvested grain and the area from which it was harvested. Crucially, the accuracy of the calculated yield is highly dependent on how well the moisture and mass or volume sensors are calibrated, as well as the precision of the differential global positioning system (DGPS) receiver [7]. Moreover, the effective area harvested is not fixed but depends on variables like header width and harvester speed, which introduce further complexity. Beyond simple mapping and estimation, accurate yield data provides valuable information for a variety of management purposes [8], including:

- Estimation of the amount of nutrients removed by the harvested crop.

- Economic assessment, such as the estimation of profitability.

- Delineation of site-specific management zones for tailored interventions.

- Analysis of the impacts of different experimental treatments within a field.

- Provision of verifiable, scientific data to farmers, serving as backed proof for low-yielding zones identified previously.

However, despite technological advancements, the integrity of the data hinges on rigorous calibration and inspection. Routine checks are necessary before and during harvest, including visual inspections for equipment damage, sensor tests for accurate moisture detection, and precise calibration to synchronize yield monitor data with actual moisture content and correctly recorded header swath. Proper inspection and calibration are paramount to maintaining yield data consistency and accuracy [9].

1.4. Research Gap and Study Objectives

Despite these essential measures, significant uncertainties in yield data derived from harvesters remain, often due to sensor drift, incorrect calibration, or environmental factors [10]. Therefore, for reliable information on yield performance—either at the field scale or site-specifically—the integration of additional data sources (such as harvest weighing, remote sensing, and farmer records) often becomes necessary. Furthermore, the raw data must frequently undergo post-processing, utilizing various geospatial techniques in order to identify and remove artifacts (data spikes, location errors, etc.), thus ensuring the integrity of the final yield map [11].

The need for standardised procedures for post-harvesting yield data management has been addressed by several studies up until now; specifically: (a) Lyle et al. (2019) established an essential multi-step filtering and cleaning protocol to address data uncertainty (e.g., zero values, speed errors, sharp turns) for maize and soybean [7]; (b) Clarke at al. (2024) proposed a framework for statistical cleaning and accuracy assessment by comparison with recorded yields from trailer weigh cells, towards identification of management zones across an entire farm using fuzzy clustering [12]; (c) Vega et al. (2020) proposed standardized procedures for yield map corrections [13]. In addition to the above studies, several instructive booklets can be found on the web; specifically: (a) for ingestion, cleansing, and rasterisation of row crop yield data in QGIS [14]; and (b) for ingestion, cleansing, rasterisation, and analysis of row crop yield data in ArcGIS Pro 3.6 [15].

Rice cultivation—a globally critical staple crop and a notable agricultural activity in regions like the Axios River Plain, Greece—presents unique data management and water management challenges due to specific harvesting equipment and flooded paddy practices. These challenges include efficient irrigation, water-level control, and remote monitoring to optimize yield and reduce resource use [16].

The critical need for a structured and reliable approach to collecting, validating, and processing rice yield data highlights a clear gap in standard protocols. The overall aim of this work was thus to establish a protocol for comprehensive rice yield data management, specifically addressing the challenges within the Greek paradigm. More specific objectives include:

- Identifying all possible sources of rice yield data, e.g., yield monitors, field measurements, remote sensing, institutional reports, etc.

- Assessing the reliability and accuracy of rice yield data obtained directly from harvesters.

- Exploring the necessity for post-processing rice yield data from harvesters, including cleansing, homogenization, and calibration.

- Developing a methodology for homogenizing rice yield data derived from different harvesters and sources to enable accurate comparisons between fields and across years.

2. Study Area

2.1. Geographic Context and Agricultural Importance

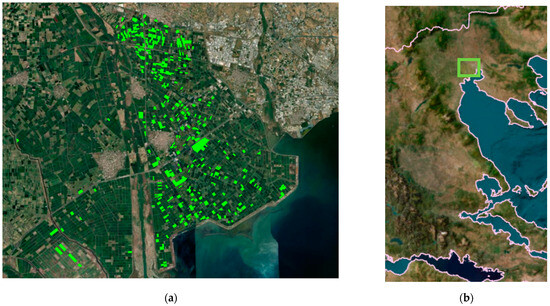

The study area is situated within the Axios River Plain in Northern Greece, a region with a deep historical connection to agriculture where rice cultivation has been recorded since classical times [17] (Figure 1a). This low-lying coastal area, spanning approximately 22,400 hectares, serves as the primary rice production zone in Greece (Figure 1b). Specifically, the rice fields involved in this study are well distributed, primarily throughout the eastern part of the plain. Annually, these fields cover an extent of about 750 hectares, with the majority of the monitored area belonging to eight different rice farmers. The concentration of rice farming and the historical significance of the area make it an ideal paradigm for establishing yield data management protocols.

Figure 1.

(a) Study fields (green polygons), mainly distributed in the eastern part of the Axios River Plain; (b) Axios River Plain (green box), located in the north part of Greece.

2.2. Environmental and Hydrological Conditions

The Axios River Plain experiences a typically Mediterranean climate, characterized by moist, cold winters and dry, warm summers. This temperate summer climate is highly suitable for intensive rice cultivation, even accommodating demanding indica-type genotypes. The area receives a mean annual precipitation of 440 mm, with a mean annual temperature of 15.8 °C [18]. However, due to the high evaporative demand, the mean annual reference evapotranspiration is substantial at 1040 mm [19]. Consequently, irrigation is critical and is supplied from the Axios River dam. Water is distributed to the fields through an extensive, open collective irrigation network, while efficient drainage is maintained by a separate network that discharges water into the Thermaikos Gulf via dedicated pump stations.

The local soils are predominantly alluvial and classified as Typic Xerofluvents, which are recent floodplain soils developed under the prevailing Mediterranean climatic conditions. These soils are mostly silty clay and naturally poorly drained. However, recent experiments have indicated that salinity levels in the area are quite low, suggesting minimal soil degradation hazard. This favorable finding can be attributed to the adequate performance of the regional water management system, specifically the effectiveness of the drainage network in preventing salt accumulation [20].

2.3. Cropping System and Yield Performance

The local agricultural practice is dominated by a monocropping system of rice, though approximately one-quarter of the area is rotated with other cash crops such as maize, alfalfa, or cotton to maintain soil health and interrupt pest cycles. The annual cycle involves sowing carried out in mid-May, followed by harvesting in late September to early October. The precise timing of harvest is determined by grain moisture levels, which ideally must be maintained between 19% and 21% for optimal quality and processing. The region is notable for its high productivity; the Axios River Plain produces an average yield of 10 tonnes per hectare (t/ha), which is the highest recorded in Greece. This figure significantly exceeds the official national yield average of 8.89 t/ha [21] and the lower figure of 7.70 t/ha reported by the Joint Research Centre [22], underscoring the superior performance and management complexity of this specific area.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Overall Methodology

The protocol for the rice yield data management was shaped gradually over the period 2017–2024, through which the entire dataset was acquired. A series of functions was followed consistently every year, including: data acquisition, data ingestion, data corrections, data transformations, data merging, data conversion, data unification, data enhancement, data calibration, data exploration, data classification, and data display.

3.2. Data Acquisition and Preparation

This initial phase focuses on the data collection and data ingestion of raw yield information from diverse sources, ensuring that the data is in a usable format and consistent coordinate system.

3.2.1. Source Data Acquisition

The foundational rice yield data were recorded by four different types of yield monitors mounted on commercial harvesters operating in the study area: a Claas 600, a Claas Lexion 8700 TT, a John Deere S7-70, and a New Holland. The data were then extracted from the yield monitors, typically in shapefile format, either through a direct export from the harvester’s onboard computer to a USB drive or via download from the respective vendor’s web platforms. Subsequently, these heterogeneous data sets were imported field by field into the study’s Geographic Information System (GIS).

3.2.2. Coordinate System Unification

A crucial initial step (part of data conversion and data unification) involved resolving projection inconsistencies. Some of the recorded yield layers were already projected in the WGS84 coordinate system, while others lacked a defined projection (reported as an “unknown system”). To facilitate accurate spatial comparisons and subsequent geospatial functionalities, all yield layers were uniformly projected to the WGS84 system in the GIS environment, a prerequisite for any comparative spatial analysis [23].

3.2.3. Data Type Normalization

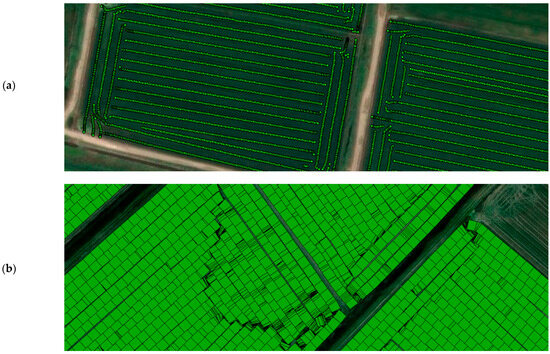

Upon visualization, the raw data exhibited two primary types: point-type data and polygon-type data (Figure 2). The polygon data generally covered the entire field surface with quasi-equally sized parallelograms (approx. 50 m2 each), whereas the point data consisted of continuous recordings along the harvesters’ routes, typically spaced about one meter apart along the track and seven meters apart between passes. The specific arrangement and level of detail for each data set were dictated by the industrial standards and task setup of each individual yield monitor. As anticipated, the regular arrangement for both data types was disrupted by irregular maneuvers, turns, or speed changes performed by the harvesters [8].

Figure 2.

Vector data types of yield recordings after their ingestion into the study’s GIS (both representations at the same mapping scale): (a) Point data type (green dots); (b) Polygon data type (green polygons).

3.3. Data Cleansing and Preprocessing

This phase encompasses several critical steps of data corrections and data transformations necessary to remove noise and ensure the scientific validity of the yield measurements.

3.3.1. Geometry Repair and Filtering

For the polygon-type yield data, the layers were first repaired for geometry errors to address common topological errors such as self-intersections. Following this, a crucial filtering step was applied: features smaller than 30 m2 were systematically removed, as they were deemed unrealistic measurements or “noise,” typically generated during turns or sudden stops. In most cases, this process successfully cleared noisy features, leading to yield values that closely fit a quasi-normal frequency distribution pattern (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(a) Clearing of polygon-type yield data by filtering out features smaller than 30 m2 (removed data in red; cleared data in green); (b) The frequency distribution of the cleared data.

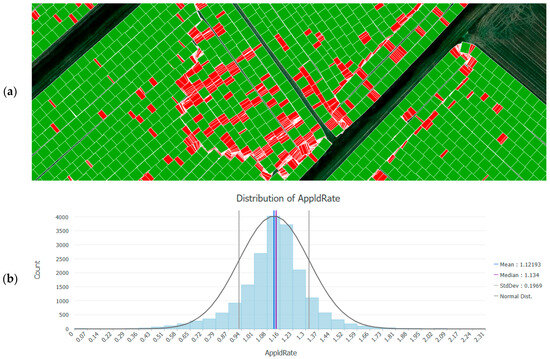

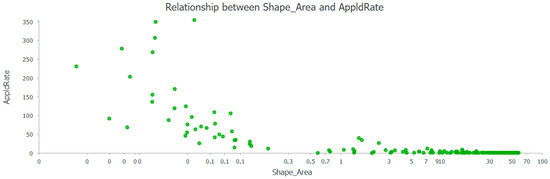

The value of 30 m2 was selected as a threshold, by observing the yield vs. area scatter plots, in which abnormally high yield values appeared only below this value (Figure 4). The selection of the threshold was verified through a trial-and-error approach, in which the frequency distributions of the yield values contained in the resulting polygons were checked for their quasi-normality.

Figure 4.

Scatter plot of yield (“AppldRate”) vs. area (“Shape_Area”), in which a 30 m2 area-value appears to be the low threshold for normal yield values.

3.3.2. Outlier Detection and Removal

During the process of data ingestion (data corrections), it was immediately apparent that many yield monitors were not switched off between fields, resulting in numerous records of zero values during movement. Furthermore, many abnormally high yield values were also observed (e.g., 249,010 t/ha), which severely violate the expected yield range. Although such abnormal values may be filtered by onboard systems for real-time visualization, they were often retained in the exported or downloaded raw numerical files.

The removal of these abnormal values was essential for sound analysis. The specific thresholds were determined using a trial-and-error approach to approximate a quasi-normal distribution. An upper threshold was generally set at 20 tonnes per hectare (t/ha). Notably, the initial filtering of small polygon features (those less than 30 m2) had already partially addressed the high-value outliers in the polygon data set. The determined upper threshold of 20 t/ha was verified by local historic data and the experience of the farmers. These findings are also in accordance with the globally reported theoretic and achieved figures, which all are found below 20 t/ha [24].

3.4. Data Analysis and Application

The final phase involves data merging, data calibration, data exploration, and data classification to derive meaningful conclusions and facilitate practical application for farmers.

3.4.1. Spatial Interpolation and Calibration

The preprocessed and cleaned point-grid data for every year were converted into continuous raster yield surfaces using the Inverse Distance Weighted (IDW) interpolation technique. Raster surfaces are the most appropriate data type for smoothed, homogenised, easily comparable spatial datasets, which also can easily be subjected to numerical and statistical operations.

Subsequently, the yield surfaces underwent a vital calibration step based on available in situ weighing data provided by the farmers (Figure 5). This process addressed inherent inaccuracies in the yield monitors. The observed discrepancies between monitor-recorded data and in situ weighting data ranged from 3.4% to 9.3% annually, with extremes from 0.7% to 27.8%. These variations underscore the expected effect of a lack of or insufficient calibration of the yield monitors for specific cultivar characteristics or moisture levels prior to recording [7].

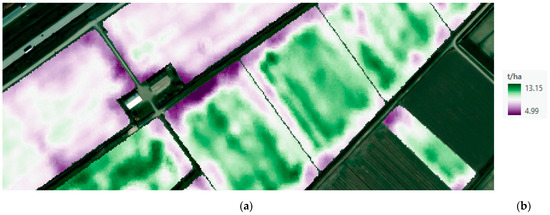

Figure 5.

Raster yield mapping from cleared point data with IDW interpolation in GIS at 5 m spatial resolution (before calibration): (a) Map abstract; (b) Legend.

3.4.2. Comparative Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics were calculated across three distinct farmer groups, allowing robust data exploration and comparative analysis:

- PrecAg: Farmers implementing precision fertilization practices in the Axios River Plain (data derived from yield monitors, 2017–2024).

- Non-PrecAg: Farmers not implementing precision fertilization in the Axios River Plain (data derived from yield monitors, 2020–2024).

- JRC: The generic group of rice farmers across Greece, as reported by the JRC/MARS (data estimated via remote sensing and local reporting, 2014–2024).

3.4.3. Heterogeneity and Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

The spatial structure of the data was examined through spatial autocorrelation by applying the Moran’s Index to the cleared point-grid data, while the within-field heterogeneity was examined separately for the PrecAg and Non-PrecAg groups using the Coefficient of Variation (CV) measure.

To detect local variance, a segmentation methodology was employed. Segmentation is defined as the process of surface division into spatially continuous, disjoint, and homogeneous regions [25], which minimizes within-zone variation while maximizing between-zone variation.

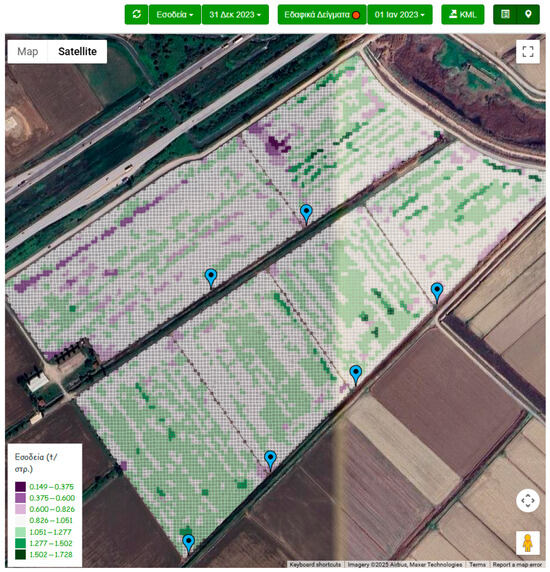

3.4.4. Data Display and Application

Since 2022, the cleared and calibrated yield maps have been regularly communicated to the participating farmers for practical precision agriculture use through a module embedded in a cloud-based Farm Management Information System (FMIS), namely ifarma [26]. Within this platform, the data are displayed as classified maps using the equal interval algorithm (Figure 6). The integration of this yield mapping module (namely, PreFer) into ifarma allows registered users to leverage yield information alongside other map types (soil, nutrient needs, satellite monitoring) for holistic farm management [27].

Figure 6.

Visualization of yield maps in PreFer module of the ifarma FMIS platform (Greek version; yield units represent t onnes per 10−1 hectares).

4. Results

The application of a standardized rice yield data management process resulted in a clear, comprehensive protocol comprising five distinct functional descriptors. This framework serves not only as the procedural guide for this work but also as the primary structural result, providing a consistent and replicable approach to handling heterogeneous yield data.

4.1. The Five-Descriptor Protocol Framework

The protocol organizes the complex sequence of geospatial functions into a structured framework, where each descriptor corresponds to a major sub-process or phase of rice yield data management (Table 1). These functions were executed primarily within a GIS environment.

Table 1.

The descriptors corresponding to major sub-processes of rice yield data management.

4.2. Quantitative Yield Performance Results

Applying the protocol framework allowed for the robust quantification and comparison of yield performance across three defined farmer groups. The Data Homogenization and Data Analysis descriptors were key in generating the following outcomes:

4.2.1. Yield Discrepancy and Calibration

A critical finding during the Data Homogenization phase was the confirmation of significant inaccuracies in raw yield monitor data. Discrepancies between the yield monitor recordings and the farmer-provided in situ weighing data ranged from 3.4% to 9.3% annually, highlighting the mandatory need for the calibration step within the protocol. This variability underscores that non-calibrated monitor data cannot reliably serve as the basis for precision agriculture applications.

4.2.2. Comparative Yield Averages

The Data Analysis descriptor provided clear evidence of yield differentiation among the farmer groups, during the period of 2020–2024, where yield data were available for both groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Post-calibration average rice yield values for the PrecAg and the Non-PrecAg groups (derived from yield monitors mounted on harvesters); for comparison, the national average in Greece (derived from JRC/MARS reports).

- The PrecAg (Precision Agriculture) group, utilizing site-specific fertilization, achieved the highest average yield at 9.87 t/ha.

- The Non-PrecAg group, using conventional methods, had a lower average of 9.11 t/ha.

- Both groups significantly outperformed the broader national average of 7.68 t/ha (reported by JRC/MARS).

This difference confirms that, under the established protocol, rice fields employing precision fertilization consistently demonstrated higher average productivity. The difference of the annually weighted average between the two groups’ yields was calculated to 8.4%. It was also noticed that the PrecAg group achieved higher stability of yield performances between years than the Non-PreAg group (3.1% vs. 4.1% variation).

4.3. Characterization of Within-Field Variability

The protocol enabled detailed within-field heterogeneity analysis using measures of both global and local variance, which is essential for delineating management zones.

4.3.1. Global Variance (Coefficient of Variation—CV)

The analysis of the global variability across fields demonstrated that the Non-PrecAg group exhibited a higher degree of field-scale variation (average CV = 9.8%) compared to the PrecAg group (average CV = 8.6%). The 14% lower CV in the precision agriculture group suggests that the site-specific management practices may be contributing to greater yield uniformity across the field, effectively managing the major sources of spatial variability.

4.3.2. Local Variance and Spatial Structure

Through the Data Analysis descriptor, segmentation using the Segment Mean Shift algorithm successfully identified locally homogeneous yield zones, suitable for management zone delineation. Furthermore, the analysis of spatial autocorrelation using Moran’s Index confirmed the non-random spatial distribution of rice yield, with the overall data set exhibiting a clearly clustered pattern (Moran’s Index: 0.543). This outcome validates the premise of precision agriculture: that variability exists in predictable, clustered patterns rather than randomly across the field.

4.4. Visualization

The final result of the protocol, enabled by the Data Visualization descriptor, is the seamless transfer and display of the processed, cleared, and calibrated yield maps on the ifarma FMIS platform in near real time (Figure 6). The active communication of the maps to the farmers allows them to enter the assessment procedure from very early, thus demonstrating the protocol’s direct application and practical value in operational farm management.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Protocol as a Validated Data Management Framework

The central outcome of this work is the establishment of a robust protocol for managing heterogeneous rice yield data. This framework systematically addresses the challenges inherent in merging data from various sources, conditions, and units—comprising distinct steps for data collection, cleansing, calibration, homogenization, filtering, analysis, and visualization. The core functional technologies employed, namely the Geographic Information System (GIS) for visualization, editing, and analysis, and the Farm Management Information System (FMIS) for communication (ifarma), proved highly effective in processing real-world, extensive, and diachronic data sets from the Axios River Plain. Crucially, because all data used were sourced from various rice fields and different varieties, the protocol was developed and validated simultaneously against genuine operational constraints.

Although the necessity of yield data post-processing has been addressed earlier [7] and GIS/FMIS integration has been recognized as best practice in precision agriculture research [28], the current study provides the first published, validated, multi-step protocol applied specifically to rice cultivation under the unique Greek operational and environmental conditions, thereby addressing a specific gap in the literature.

5.2. Low Yield Variability Versus High Environmental Variability

One of the most significant findings derived from applying the protocol is the unexpected difference in spatial variability between yield data and underlying environmental factors. When compared to the inherent variability of a representative subject area (approx. 120 hectares), the within-field yield variability was found to be significantly lower on average:

- Soil Properties (derived from sampling and interpolation): approx. 33.7% average within-field variability [29].

- Spectral Properties (derived from satellite imagery): approx. 35.3% average within-field variability [29].

- Processed Yield Data (derived from yield monitors): approx. 8.6% average within-field variability.

These findings strongly indicate that the rice farmers in the study area are successfully managing cultivation resources (soil, water, fertilizers, etc.) toward promoting yield uniformity through appropriate and generally effective farming practices. The processed yield data also exhibited a clearly clustered character (Moran’s Index: 0.543), which aligns with low variability figures; variability, while present, is confined to distinct, manageable zones rather than being randomly distributed across the field.

5.3. Impact of Precision Agriculture on Yield and Uniformity

The comparative analysis facilitated by the protocol provided quantitative evidence supporting the benefits of precision agriculture (PA) practices. The average yield for the PrecAg group was significantly higher than the Non-PrecAg group, demonstrating the positive impact of site-specific fertilization on overall productivity.

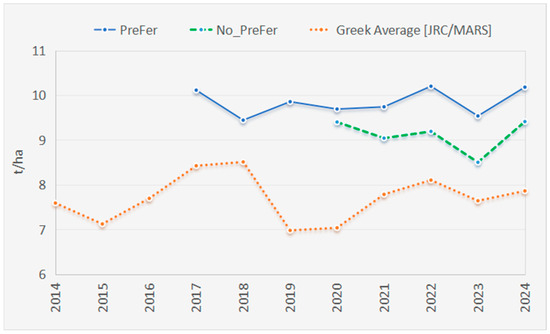

The results clearly indicated that for the common period (2020–2024), the PrecAg group maintained a significantly higher average yield 9.87 t/ha than both the Non-PrecAg group (9.11 t/ha) and the national JRC/MARS average (7.68 t/ha). This observation, while outside the scope of detailed attribution in this study, strongly suggests the positive impact of precision management on rice productivity [2] (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Yield average values plotted against years for different farmer groups: PrecAg (implementing precision fertilization), Non-PrecAg (not implementing precision fertilization), and the Greek average (as reported by JRC/MARS).

However, the analysis of spatial heterogeneity revealed that the within-field uniformity (CV) in the PA fields was only slightly higher than in the non-PA fields. This result, combined with the higher average yields in the PrecAg group, suggests a crucial implication: precision agriculture methodologies contribute to the improvement of low-performance and high-performance zones equally. PA is not merely about maximizing the best areas but is effective in managing variability across the entire field, leading to both higher mean yield and sustained uniformity.

5.4. Application in Predictive Modeling and Variation Interpretation

The quantitative, extensive, and diachronic nature of the yield data sets, validated and cleaned through this protocol, proved instrumental for advanced applications. Specifically, these data served as essential input for the development of fertilization predictive algorithms [30]. The authors successfully leveraged the yield data alongside soil, satellite imagery, climatic, and farming practice information to develop a machine learning model for optimal N-rate recommendations, demonstrating the direct scientific value of a reliable yield management protocol [31].

Furthermore, the study confirmed that yield variability is influenced by a range of factors beyond fertilization. Localized low-yield spots are often linked to non-systematic factors identified through farmer observations [32], including:

- Soil mechanics: Poor tillage, tractor traces causing compaction or crust formation.

- Hydrology: Rapidly drained (sandy soils) or persistently flooded locations (ground lowering).

- Obstacles and Wildlife: Physical obstacles (power columns) or the destructive presence of protected birds (flamingos in the Ramsar site).

- Pest Management: Weed infestations or collateral damage from spraying of weed management substances.

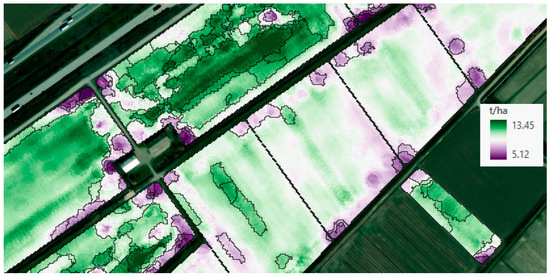

5.5. Methodological Choices for Zone Delineation

In the context of practical PA application, the study concluded that simple methods like clustering and unsupervised classification were inappropriate for reliable management zone delineation due to their sensitivity to random management or application abnormalities. Instead, segmentation—specifically the Segment Mean Shift algorithm—is validated and recommended (Figure 8). Segmentation is demonstrably superior as it corresponds better to inherent variation factors like soil properties or chronic problematic areas, thereby refining and improving the original soil sampling scheme [29].

Figure 8.

Extract of a rice yield map after segmentation with the Segment Mean Shift algorithm (embedded in ArcGIS Pro 3.6) (produced segments are outlined by thin black lines).

Finally, the visualization of the processed yield data on a cloud-based platform (like ifarma) is a critical factor for the protocol’s success, as it promotes farmers’ education, training, and the perceived value of the precision agriculture services. This reinforces the perspective that PA technology is a social process that fundamentally changes how farmers interact with their land and external experts, not merely a matter of technology adoption [33].

5.6. Future Enhancements

To further enhance the practical utility and scientific robustness of the protocol, future work should focus on formally integrating farmers’ expertise and qualitative data by incorporating objective and quantitative metrics for:

- Identifying specific spots with tillage or compaction issues.

- Mapping irrigation problems (waterlogged or rapidly drained spots).

- Correlating weed and pest outbreaks with low-yield spots.

This integration will allow the system to attribute yield loss more precisely, moving the protocol toward a comprehensive diagnostic tool.

6. Conclusions

The necessity and efficacy of establishing a standardized protocol for managing rice yield data derived from harvesters were unequivocally confirmed. This protocol, anchored by a clear geospatial approach with a Geographic Information System (GIS) at the core of the procedural tier, is essential for robust data handling, analysis, and visualization, enabling the extraction of rational and dependable conclusions about rice cultivation.

6.1. Accomplishment of Specific Objectives

The specific objectives outlined for this work were fully accomplished, leading to several key confirmations: All possible sources of rice yield data were identified, encompassing various types of onboard yield monitors, high-accuracy in situ field measurements (weighing), and aggregated institutional reports (JRC/MARS) based on satellite imagery and communication with farmers.

The reliability of rice yield data recorded by harvesters was assessed as high, exhibiting an annual accuracy ranging between 91.7% and 96.6% after calibration. This high post-calibration accuracy validates the use of yield monitors as a primary data source, provided the developed protocol is consistently applied.

The necessity for comprehensive post-processing was verified. The resulting protocol requires distinct phases—organization, curation, homogenization, analysis, and visualization—to reliably transform raw, heterogeneous data into calibrated, spatially consistent, and usable yield maps.

6.2. Key Contributions and Significance

Beyond meeting the initial objectives, the study yielded three significant conclusions relevant to the application of precision agriculture in rice cultivation: The protocol enabled a direct quantitative comparison that demonstrated the superior performance of precision-managed rice fields. The average yield for the precision agriculture (PrecAg) group was consistently higher than both the non-precision (Non-PrecAg) group and the national average, firmly supporting the economic viability of site-specific fertilization in the region.

The processed yield data revealed a relatively low spatial within-field variability (approx. 8.6%) compared to the high variability of underlying environmental factors (soil and spectral properties (approx. 33–35%)). This finding suggests that current farming practices effectively buffer many sources of environmental variability, with precision agriculture contributing to both higher yields and greater spatial uniformity.

The research strongly endorses spatial segmentation over simple clustering for yield map analysis, establishing it as the appropriate method for delineating operational management zones that correlate with inherent field variations.

In summary, the established protocol provides a validated, high-accuracy framework for managing complex rice yield data, offering a crucial tool for both scientific study and practical farm management. While the current protocol is robust, its utility can be further enhanced by formally incorporating qualitative data derived from farmers’ expertise and field notes, transforming it into a more comprehensive diagnostic and decision-support system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K. and S.M.; methodology, S.M.; software, C.K.; validation, C.K. and M.I.; formal analysis, C.K.; investigation, M.I.; resources, S.M.; data curation, C.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.K.; writing—review and editing, S.M. AND M.I.; visualization, M.I.; supervision, S.M.; project administration, S.M.; funding acquisition, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data may become available upon request.

Acknowledgments

Cordial thanks to all the farmers who permitted the use of their data for this study and particularly to: K. Kravvas, P. & N. Goutas, P. Kipouros, P. Soumparas, D. Fotakidis, C. Fotakidis, A & P. Kravvas, and A. Kampouris.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmad, L.; Mahdi, S.S. Yield Monitoring and Mapping. In Satellite Farming; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karydas, C.; Iatrou, M.; Mourelatos, S. An Innovative Process Chain for Precision Agriculture Services. Computers 2025, 14, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zion Market Research. Precision Farming Market Size, Share, Growth and Forecast 2032. 2025. Available online: https://www.zionmarketresearch.com/report/precision-farming-market#:~:text=The%20yield%20monitoring%20segment%20is%20anticipated%20to%20report,landlord%20negotiations%2C%20and%20track%20records%20for%20food%20safety (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Kabir, M.S.; Gulandaz, M.A.; Ali, M.; Reza, M.N.; Kabir, M.S.N.; Chung, S.-O. Yield monitoring systems for non-grain crops: A review. Korean J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 51, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannsen, C.J.; Carter, P.G. Site-Specific Soil Management. In Encyclopedia of Soils in the Environment; Hillel, D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 497–503. ISBN 9780123485304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, C.; Dalla Marta, A.; Napoli, M.; Orlandini, S.; Verdi, L. Short-term response of greenhouse gas emissions from precision fertilization on barley. Agronomy 2023, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyle, G.K.; Johnson, B.E.; Johnson, A.M.H.; Humburg, C.L. On-the-go data quality control for yield monitors. Trans. ASABE 2019, 62, 939–947. [Google Scholar]

- Fulton, J.; Hawkins, E.; Taylor, R.; Franzen, A. Yield Monitoring and Mapping. In Precision Agriculture Basics; Shannon, D.K., Clay, D.E., Kitchen, N.R., Eds.; ACSESS Publications: Madison, WI, USA, 2017; pp. 63–78. ISBN 978-0-89118-366-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longchamps, L.; Tisseyre, B.; Taylor, J.; Sagoo, L.; Momin, A.; Fountas, S.; Manfrini, L.; Ampatzidis, Y.; Schueller, J.K. Yield sensing technologies for perennial and annual horticultural crops: A review. Precis. Agric. 2022, 23, 2407–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauci, A.A.; Fulton, J.P.; Lindsey, A.; Shearer, S.A.; Barker, D. Precision of grain yield monitors for use in on-farm research strip trials. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byabazaire, J.; O’Hare, G.M.P.; Collier, R.; Kulatunga, C.; Delaney, D. A Comprehensive Approach to Assessing Yield Map Quality in Smart Agriculture: Void Detection and Spatial Error Mapping. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.E.; Stockdale, E.A.; Hannam, J.A.; Marchant, B.P.; Hallett, S.H. Whole-farm yield map datasets—Data validation for exploring spatiotemporal yield and economic stability. Agric. Syst. 2024, 218, 103972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, A.; Córdoba, M.; Castro-Franco, M.; Balzarini, M. Protocol for automating error removal from yield maps via statistical filtering. Precis. Agric. 2020, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girz, A.; Mattila, T.J. Processing of Combine Harvester Yield Monitor Data in QGIS. Available online: https://files.core.ac.uk/download/586795241.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Murrell, T.S.; Rund, Q.B. Using ArcGIS for Yield Data Analysis (ESRI Paper). Available online: https://proceedings.esri.com/library/userconf/proc03/p0897.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Tripathi, R.; Nayak, A.K.; Shahid, M.; Gautam, P.; Bhattacharyya, P.; Satapathy, B.S. Precision farming technologies for water and nutrient management in rice: Challenges and opportunities. Oryza 2021, 58, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallare, R. The Ecology of the Ancient Greek World; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1993; p. 23. ISBN 0801426154. [Google Scholar]

- Hijmans, R.J.; Cameron, S.E.; Parra, J.L.; Jones, P.G.; Jarvis, A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2005, 25, 1965–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschonitis, V.G.; Papamichail, D.; Demertzi, K.; Colombani, N.; Mastrocicco, M.; Ghirardini, A.; Castaldelli, G.; Fano, E.-A. High-resolution global grids of revised Priestley-Taylor and Hargreaves-Samani coefficients for assessing ASCE-standardized reference crop evapotranspiration and solar radiation. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2017, 9, 615–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litskas, V.D.; Aschonitis, V.G.; Lekakis, E.H.; Antonopoulos, V.Z. Effects of land use and irrigation practices on Ca, Mg, K, Na loads in rice-based agricultural systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 132, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricepedia. Original Source: FAOSTAT. 2017. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200803030706/http://ricepedia.org/index.php/greece (accessed on 18 January 2017).

- Joint Research Centre/Monitoring Agriculture ResourceS (JRC/MARS). 2024. Available online: https://agri4cast.jrc.ec.europa.eu/bulletinsarchive (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Esri. How Segment Mean Shift Works. ArcGIS Pro Documentation. 2023. Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/help/analysis/raster-functions/segment-mean-shift-function.htm (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Sheehy, J.; Mitchell, P.L. Calculating maximum theoretical yield in rice. Field Crops Res. 2015, 182, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaschke, T. Object based image analysis for remote sensing. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2010, 65, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraforos, D.S.; Vassiliadis, V.; Kortenbruck, D.; Stamkopoulos, K.; Ziogas, V.; Sapounas, A.A.; Griepentrog, H.W. Multi-level automation of farm management information systems. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 14, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karydas, C.; Chatziantoniou, M.; Stamkopoulos, K.; Iatrou, M.; Vassiliadis, V.; Mourelatos, S. Embedding a new precision agriculture service into a farm management information system-points of innovation. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 4, 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Emeterio de la Parte, M.; Martínez-Ortega, J.-F.; Hernández Díaz, V.; Lucas Martínez, N. Big Data and precision agriculture: A novel spatio-temporal semantic IoT data management framework for improved interoperability. J. Big Data 2023, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karydas, C.; Iatrou, M.; Iatrou, G.; Mourelatos, S. Management Zone Delineation for Site-Specific Fertilization in Rice Crop Using Multi-Temporal RapidEye Imagery. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatrou, M.; Karydas, C.; Tseni, X.; Mourelatos, S. Representation Learning with a Variational Autoencoder for Predicting Nitrogen Requirement in Rice. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Arendonk, J.; Van, T.C.; Van der Werf, W. Machine learning for crop yield prediction and nitrogen management. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 650519. [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, B.S.; Mahajan, G.; Kumar, V. Integrated weed management in rice cultivation. In Recent Advances in Weed Management; Kang, M.S., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 211–236. [Google Scholar]

- Tsouvalis, J.; Seymour, S.; Watkins, C. Exploring Knowledge-Cultures: Precision Farming, Yield Mapping, and the Expert–Farmer Interface. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2000, 32, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).