1. Introduction

Animals’ use of forage and harvesting through grazing have a direct impact on the productive performance of ruminants raised in grazing systems. The conversion of ingested plant material into animal products is affected by the animal’s genetic characteristics, particularly its digestive capacity, but mainly by canopy-related aspects such as structure, availability, and nutritional value. These factors are influenced by grazing management and the plant’s vegetative stage. Therefore, understanding and predicting forage quality, particularly digestibility, is essential to support decision-making in livestock systems and improve animal production efficiency [

1,

2].

The digestibility of the forage harvested by animals provides insight into the fermentation and digestion process [

3]. However, grazing is a dynamic process. The adopted forage management strategy is one of the factors influencing canopy structure and harvesting behavior [

1]. Different grass growth forms require basic knowledge of their growth dynamics [

4]. Ipyporã grass (BRS RB331 Ipyporã) is an interspecific hybrid (

Brachiaria ruziziensis ×

Brachiaria brizantha) with a high leaf-to-stem ratio, high nutritional value, and resistance to pasture spittlebugs [

5,

6].

Monitoring forage quality is challenging from the outset, as fieldwork (grass sampling) and experiments require significant time and manual labor. Furthermore, traditional laboratory methods for evaluating forage digestibility, such as in vitro and in situ assays, are laborious, destructive, and time-consuming, requiring extensive sample collection, chemical analysis, and specialized laboratory infrastructure. These costly limitations restrict the frequency and scale of forage quality monitoring, especially under grazing conditions. Techniques that enable result prediction, such as digestibility estimation, are crucial for supporting decision-making in livestock systems [

7]. Machine learning is an ideal tool for this, as it is capable of learning from collected data and forecasting future outcomes without requiring additional material collection or extensive sample processing.

In agriculture, ML has been successfully applied to predict feed quality [

8], forage mass [

7], and nutrient content in different crops [

9]. The use of non-destructive methods contributes to the development of predictive models and aids in ruminant production [

10], demonstrating their potential to replace traditional analytical procedures and support precision livestock management.

However, few studies have applied ML techniques to estimate the digestibility of tropical forage grasses under field conditions using integrated datasets that combine pasture management and chemical composition variables. Exploring these datasets can reveal which type of information most effectively predicts digestibility and which ML algorithms perform best.

The proposed hypothesis is that machine learning can be used to predict forage grass digestibility using different input data sources. Therefore, this study aimed to compare the performance of several ML models in predicting the in vitro digestibility of leaf and stem components of Brachiaria hybrid cv. Ipyporã, based on pasture management and chemical composition data. The findings provide insights into the efficiency of ML-based prediction of forage nutritional quality and its potential applications in precision livestock systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Animals and Experimental Design

The dataset used in this study was obtained from an experiment conducted at Embrapa Gado de Corte, Campo Grande, MS (20°27′S and 54°37′W, at an altitude of 530 m), between December 2014 and September 2016. According to Köppen’s classification, the region’s climate is classified as tropical savanna (Aw subtype), characterized by seasonal rainfall distribution. The soil in the experimental area is classified as a Dystrophic Red Latosol with a clayey texture [

11].

The original field experiment was carried out between December 2014 and September 2016 using BRS Ipyporã grass (Brachiaria ruziziensis × B. brizantha) under intermittent stocking. The experimental design was a randomized complete block design with two nitrogen fertilisation levels (100 and 200 kg N ha−1 yr−1) and three replications. Each block was divided into two modules (0.75 ha) subdivided into four paddocks (0.19 ha). Nitrogen was applied as ammonium sulphate and urea during the rainy season, split into two or four applications depending on the treatment.

Pastures were managed to maintain a target sward height based on Light Interception (LI), within the range of 90–95% LI, which corresponded to a canopy entry height of 30 cm. The exit target was set when the canopy reached 15 cm. Brangus steers (1/2

Bos indicus × 1/2

Bos taurus) were used as grazers, and the put-and-take method [

12] was used to adjust the stocking rate. These animals, with an initial average weight of 200 ± 23 kg and an average age of 9 ± 2 months, were randomly distributed (four animals per module) across the experimental units, ensuring similar body weights at the beginning of the study.

2.2. Data Collection and Composition of the Dataset

The dataset comprised measurements from multiple grazing cycles over two years, representing both seasonal variation and nitrogen levels. Each record corresponded to a specific paddock and evaluation period.

The management and production variables recorded included the Forage mass (FM, kg ha−1) and its morphological composition were estimated in one paddock per module for each grazing cycle. Forage masses were estimated by collecting nine samples at ground level, each with an area of 1 m2 per paddock, at representative points of the canopy. After collection, the samples were weighed and divided into two subsamples. One sub-sample was dried in an oven at 65 °C until it reached a constant weight to determine dry matter (DM). The other was separated into leaf (leaf blade), stem (sheath and stem), and dead material. The components were dried in an oven at 55 °C until they reached a constant weight and then weighed.

The rest period (RP, days) defined as the number of days required for the paddock to reach the target entry condition again; grazing period (GP, days), calculated as the number of days the animals took to graze the pasture down to 15 cm.

For chemical composition analysis, leaf and stem samples were utilized from the FM cuts. The samples were ground in a Wiley mill (1 mm sieve) and analyzed for crude protein (CP, %), neutral detergent fiber (NDF, %), acid detergent lignin (LDA, %), and in vitro organic matter digestibility (DIVMO, %).

2.3. Measurement of Parameters Considered in the Model

The prediction of leaf and stem digestibility was carried out using three input datasets for all models: (1) management/production data, (2) chemical composition data, and (3) a combination of both sets.

The first dataset (Production) consisted of management and production data: nitrogen dose (N), rest period (RP), grazing period (GP), and forage mass (FM). The second dataset (Composition) included values for chemical composition: crude protein (CP), neutral detergent fiber (NDF), and lignin (LDA). Finally, a third dataset (Whole) combined all variables from both the management and production set and the chemical composition set as input variables for predicting the in vitro digestibility (output variable) of the leaf and stem.

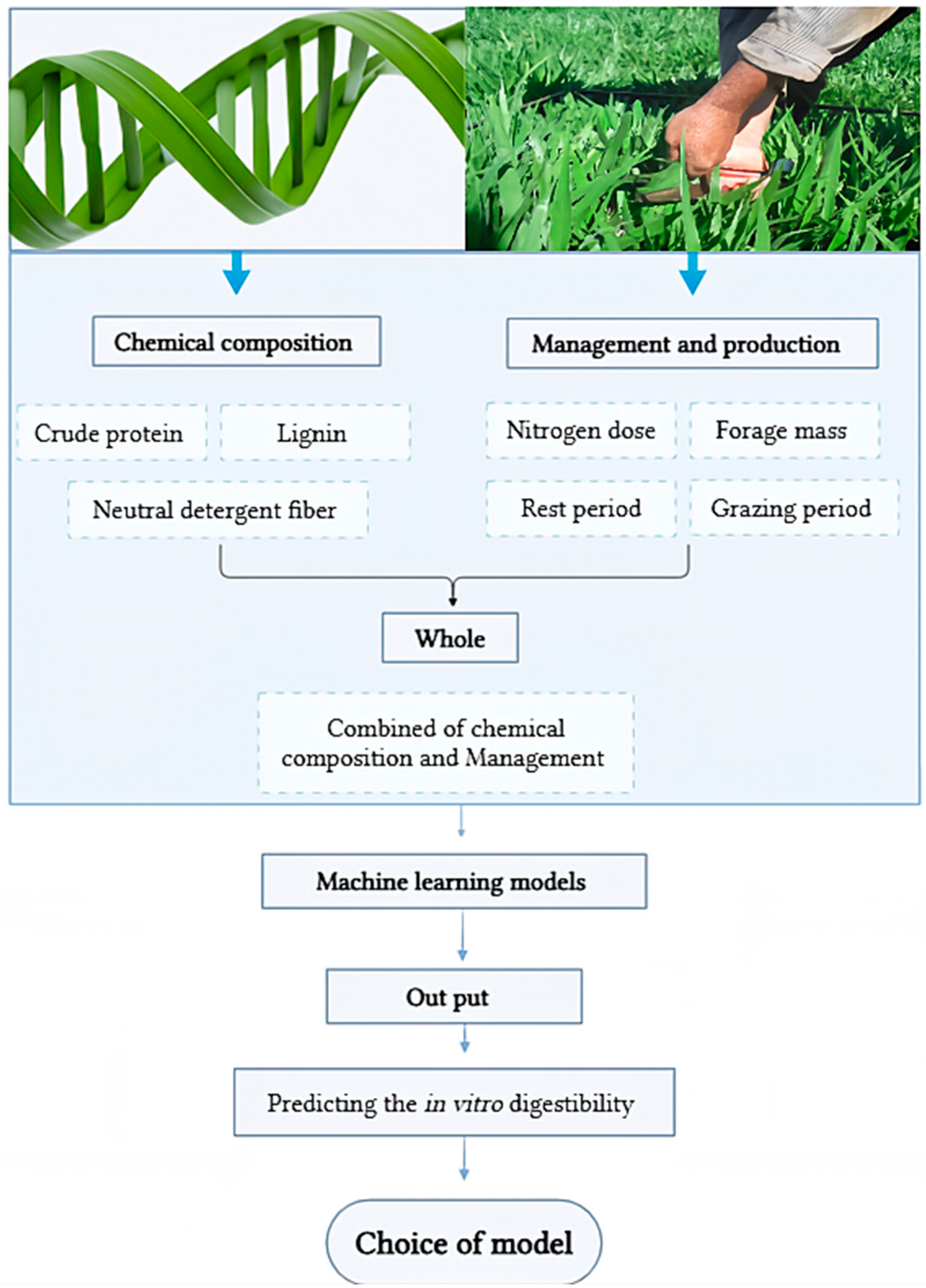

Five models were evaluated: an artificial neural network, the multilayer perceptron (MLP); two decision tree algorithms: REPTree and M5P; Random Forest (RF); and a traditional technique: Multiple Linear Regression (LR) for predicting the in vitro digestibility of Ipyporã grass leaf and stem (

Figure 1). Analyses were conducted using WEKA 3.8.6 software.

The MLP is an effective and powerful algorithm for classification, recognition, prediction, and pattern approximation. Here, we used an artificial neural network (ANN) consisting of three layers: input, output, and one hidden layer. Similar to a feedforward network in an MLP, data flows directly from the input layer to the output layer. The neurons in the MLP are trained using the backpropagation learning algorithm [

13]. The M5P model is a decision tree learner for regression problems, which uses linear regression models to define the input-output relationship based on dividing the data parameter space into several subspaces [

14].

A decision tree can also be created by other algorithms, such as REPTree. Since Reduced Error Pruning (REP) is used to improve the pruning phase, it is considered an extension of C45 [

15]. The RF model creates numerous decision trees randomly from a classification and regression dataset [

14]. To predict new values, it employs a voting system among all the trees learned [

16]. Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) is a simple tool commonly used in the scientific community due to its ability to estimate values between two correlated variables. The equation generated from these variables allows for the measurement of initially unobserved values.

During the experimental phase, parameter adjustments were evaluated to improve the performance of each model. For leaf digestibility prediction, the default configuration of the Weka 3.8.6 software was used for the M5P and LR models, while the RepTree model was configured with tree pruning, and for RF, the attribute importance measurement from the algorithm was used. The MLP model consisted of a multilayer perceptron using a backpropagation algorithm to adjust the neural network connection weights, with a learning rate of 0.1, two hidden layers with 15 neurons each, and 500 epochs. For stem models, the default configuration was used, except for the MLP, which had 600 epochs. All models were performed using stratified cross-validation with k-fold = 10 and ten repetitions (100 executions for each model). Model performance was assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r), mean absolute error (MAE), and root mean absolute error (RMAE).

2.4. Data Analysis

The input data for both leaf and stem were tested with three configurations: (1) management and production (Production), with data (N dose, FM, RP, GP) and chemical composition data (CP, NDF, and LDA); (2) Chemical composition (Composition), consisting only of chemical composition data (CP, NDF, and LDA); and (3) Management, production data and chemical composition (Whole), (N dose, FM, RP, GP, CP, NDF, and LDA). The performance of the machine learning models was evaluated using the following performance metrics: Pearson correlation (r), mean absolute error (MAE), and root mean absolute error (RMAE) between predicted and observed values. An analysis of variance was conducted to test the significance of the inputs, ML techniques, and their interaction using the Scott-Knott test at a 5% probability level, employing the R software (version 4.3.2). When the interaction was significant, boxplots were constructed with the means of the 10 repetitions used (folds) for each accuracy metric using the ggplot2 and ExpDes.pt packages from R. Prediction analyses were performed using Weka 3.8.6 on an Intel® Core™ i5 CPU with 8 Gb of RAM. To study the interrelationship between input and output variables (digestibility), the data were standardized and subjected to principal component analysis (PCA), which was carried out using R software, version 4.3.2.

3. Results

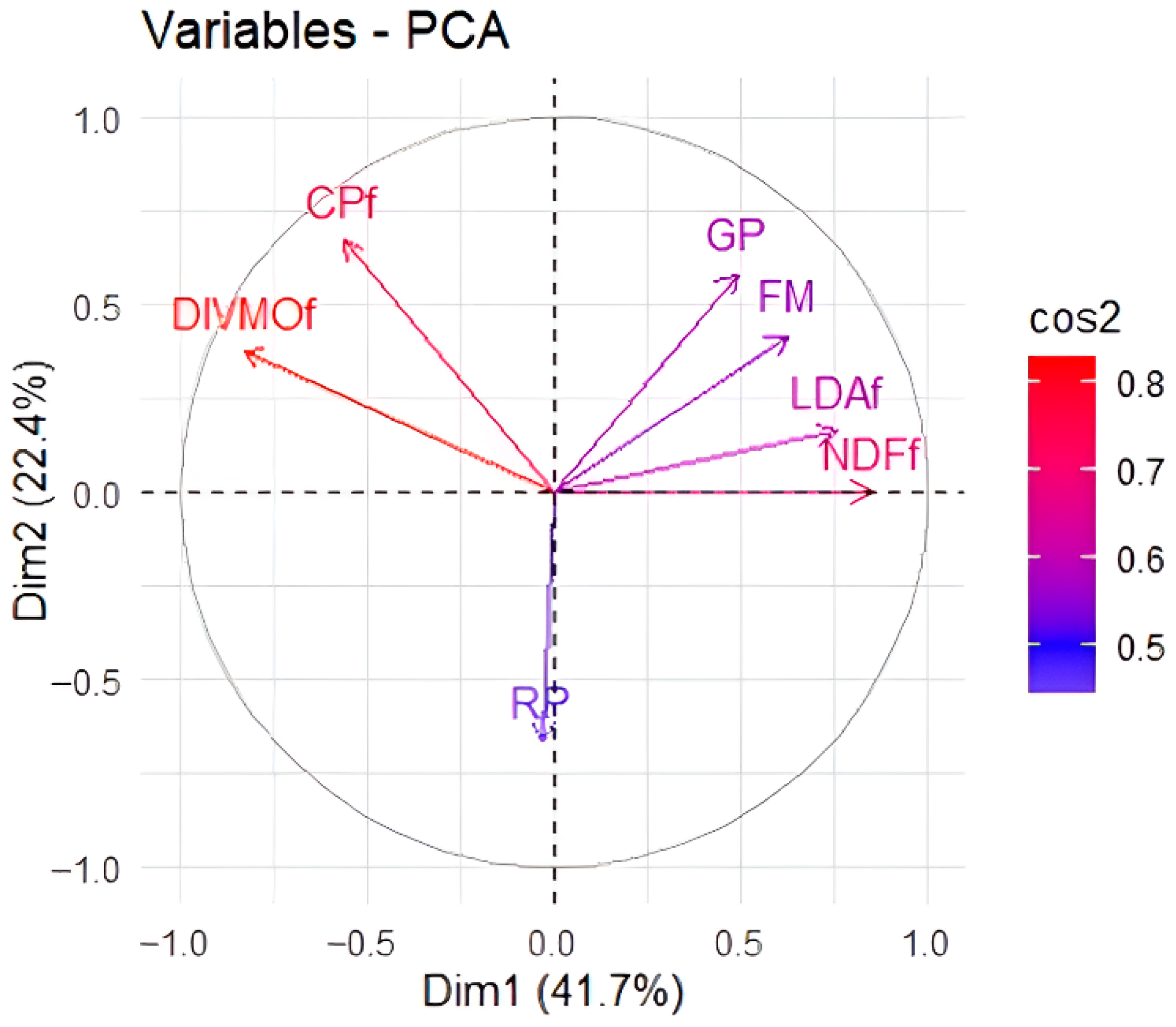

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) highlights the strong association between in vitro organic matter digestibility (DIVMO) and crude protein content. In the first component, a high correlation between digestibility and protein content in Ipyporã grass leaves can be observed (

Figure 2). Other associations observed include chemical components such as lignin and NDF, which were closely linked to the grazing period and forage mass. The pasture rest period was not associated with any variable.

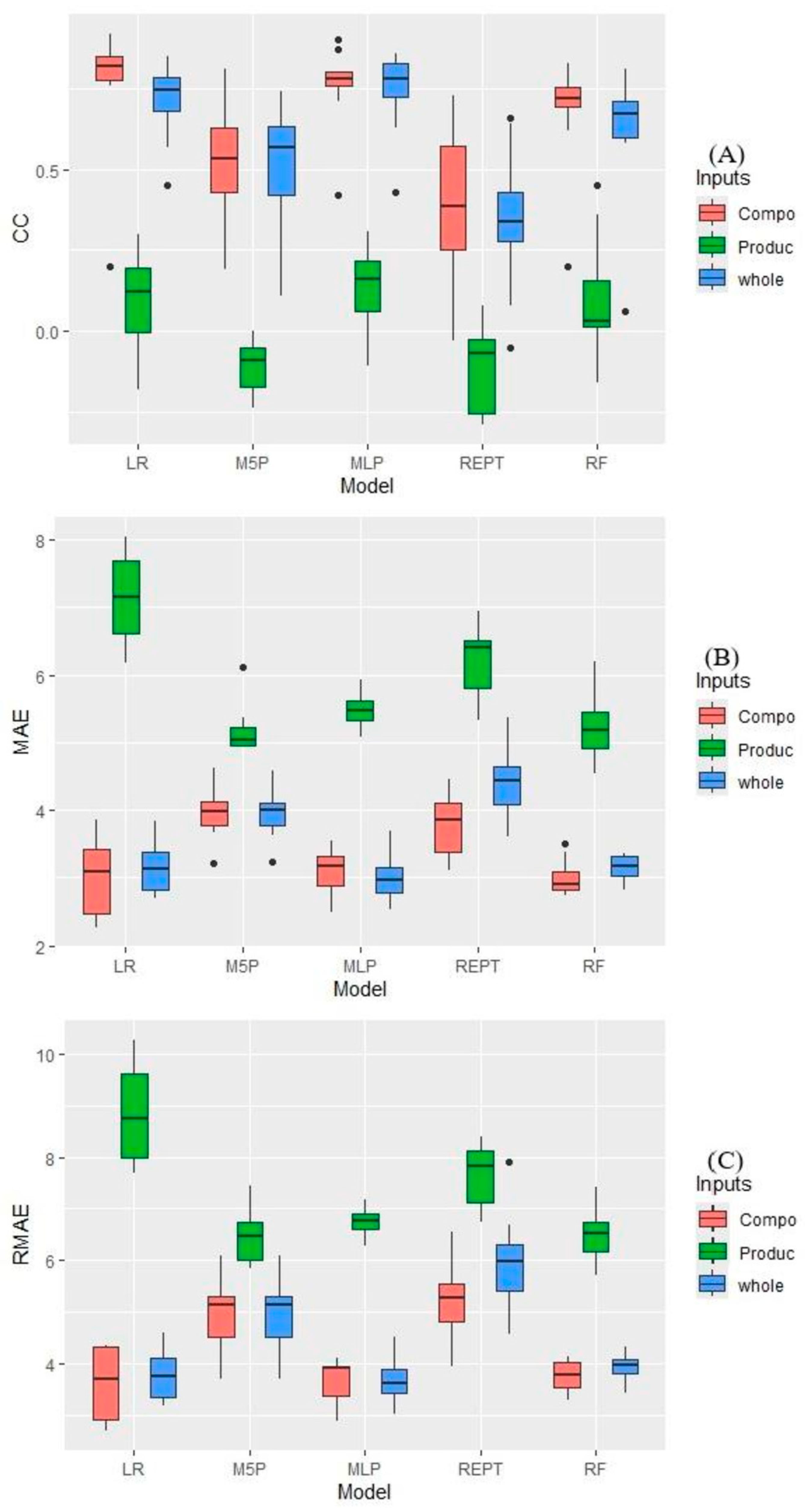

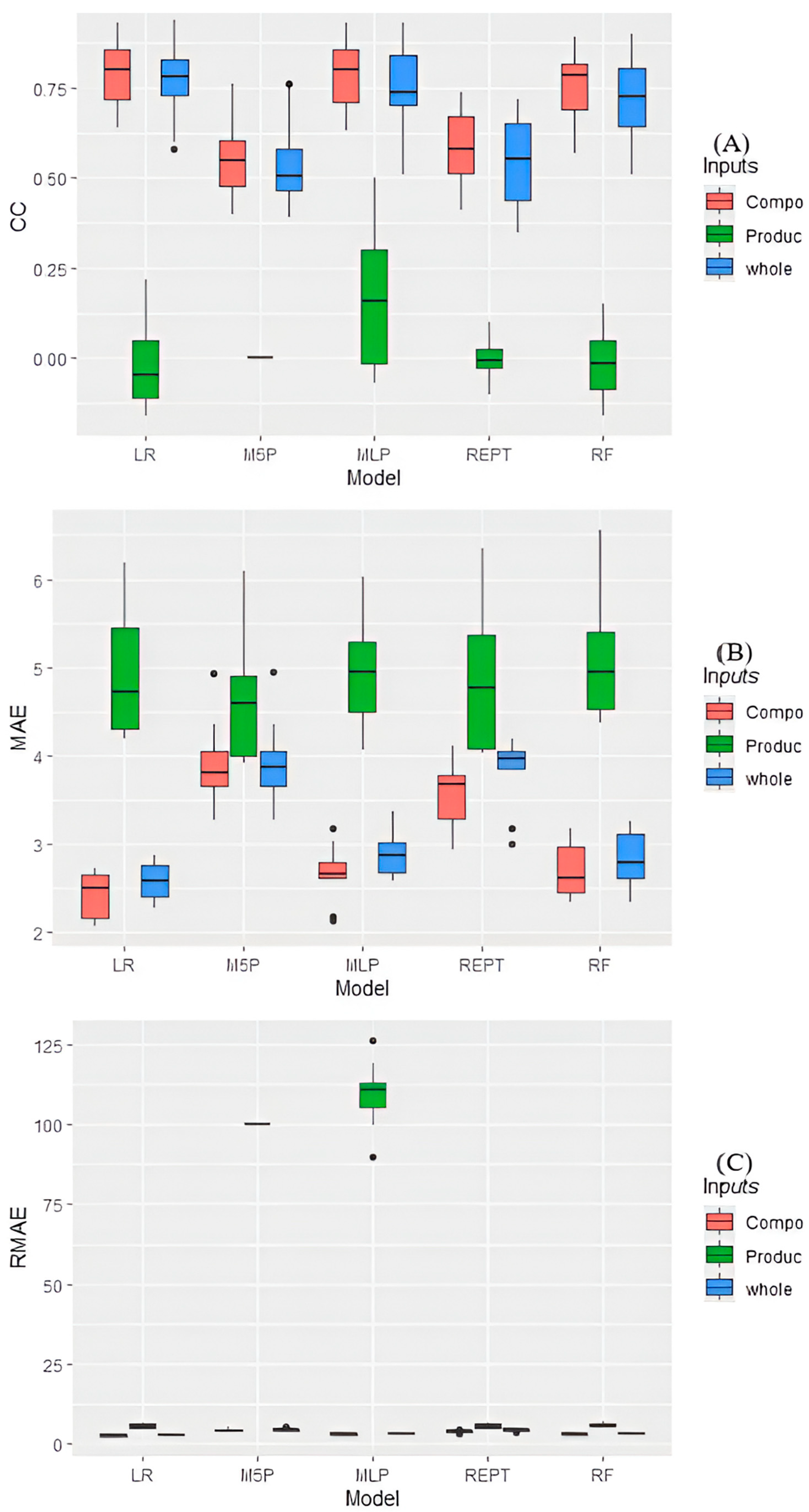

Regarding the tested models and input variables, there was an interaction (

p < 0.05) for MAE and RMAE in the prediction of leaf digestibility, while the correlation coefficient (r) showed no significant interaction (

p = 0.78366) (

Figure 3).

The best performances for predicting the in vitro digestibility of Ipyporã grass leaf were observed in the MLP, LR, and RF models, which did not differ from each other, mean prediction of 0.50 correlation coefficient, while REPTree exhibited the lowest predictive ability with 0.20 correlation coefficient (

Figure 3A). As for the evaluated inputs, there was no significant difference between the whole (management and chemical composition) (r = 0.58) and the chemical composition data (r = 0.62), with the lowest value observed for the input using only management data (r = 0.01). The r for the MLP and LR models using only composition data was 0.76.

The means of MAE and RMAE showed the same behavior (

Figure 3B,C). The management data presented the highest error among the input variables evaluated, regardless of the tested model. When testing all data as input in the models and only the composition data, similar results were observed, except for REPt, which presented the lowest average when using only the composition data. Lower MAE and RMAE indices were observed when using the full and composition data in the LR, MLP, and RF models.

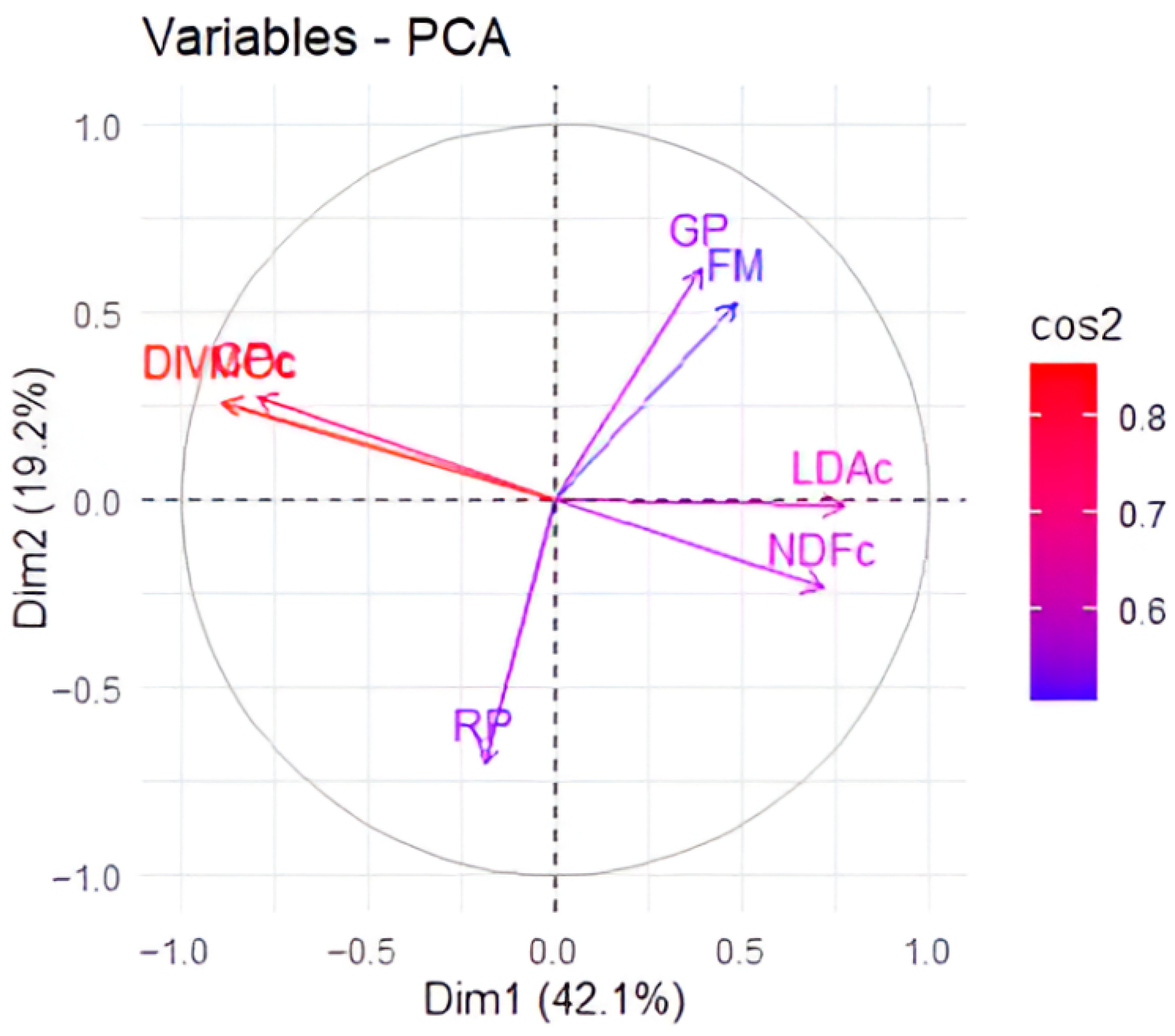

The PCA results showed that the majority of the variance in the dataset (61.3%) was explained by just two principal components (

Figure 4). Digestibility showed a strong association with crude protein content and an antagonistic relationship with lignin and NDF data. Forage mass and grazing period were highly correlated and negatively associated with the rest period.

The

Figure 5 presents the

p-values obtained by ANOVA for the r, MAE, and RMAE considering the different models and ML inputs for stem digestibility. There was a significant interaction (

p < 0.05) between the tested models and the input variables for all three evaluated variables. The r for the models that used only the production data was lower than 0.2. The only model that did not present negative values was the MLP model (r = 0.16) (

Figure 5A).

Statistically, there was no difference between the R of the models when using complete data (management and composition) and when only composition data were used (

p > 0.05) (

Figure 5A). However, when testing the models using only composition data, numerically higher R values were observed, which was the opposite of what was observed for the MAE and RMAE, where composition data showed lower numerical values, although statistically similar to the complete data, and both indices were lower than those obtained with only the management data. The best model algorithms were observed in LR, MLP, and RF, with higher r and lower MAE and RMAE (

Figure 5).

The r data between M5P and LR were very close, whether using the complete data or only the composition data. The MAE and RMAE (

Figure 5) also presented similar numerical results.

4. Discussion

The digestibility of leaf and stem components of Ipyporã grass can be predicted using machine learning (ML) techniques, but model performance depends critically on the nature and range of the input data. The dataset used for training and validation encompassed multiple grazing cycles under two nitrogen fertilization levels (100 and 200 kg N ha−1) and two seasons (rainy and dry), which provided a realistic range of field variation. For leaves (n = 42 observations), in vitro organic matter digestibility (IVOMD) ranged from 61.70% to 91.18% (mean = 72.43%, SD = 6.61). For stems (n = 42), IVOMD ranged from 54.76% to 76.46% (mean = 65.79%, SD = 5.44).

Chemical composition of leaves showed substantial heterogeneity: crude protein (CP) ranged roughly from 9.3% to 16.6% (mean = 12.4%), neutral detergent fiber (NDF) from 64.5% to 76.5% (mean = 71.2%), and acid detergent lignin (ADL) from 1.8% to 2.7% (mean = 2.3%). Stems had lower mean CP and slightly higher fibre and lignin content. Productive variables also varied widely (forage mass 1515–4237 kg ha−1; grazing period 8–32 days; rest interval 28–98 days), reflecting the combined effects of seasonality and N supply on canopy structure and composition. These ranges show that the models were trained on a dataset with realistic biological variability, but they also underscore nonlinearity and interactions among predictors that complicate prediction.

Some management-related factors in pastures can influence their nutritional value, including nitrogen dosage [

17] and conservation methods [

3]. However, pastures alter their growth pattern under stressful conditions [

2], and this plasticity is important for the persistence of grasses. Thus, management techniques may not directly influence the plant’s chemical composition, as observed by Euclides [

5], who used two management heights on Marandu grass and found no difference in the chemical composition of the forage within the same stratum.

The MLP and LR models performed better than the other techniques used, demonstrating strong performance in predicting the in vitro digestibility of grasses. This may be due to the stronger predictive performance observed for models trained on chemical composition (MLP and LR), which is consistent with the PCA results identifying crude protein as the variable most closely associated with IVOMD. Linear regression (LR) is traditionally used in agricultural experimentation for predicting outcomes, especially in studies involving fertilization [

18] or forage development [

19], and it remains a reliable approach when the relationships between variables are predominantly linear, as observed between crude protein and digestibility.

Regardless of the model used and which component (leaf or stem) of the grass was being evaluated, the use of PB, NDF, and lignin values was sufficient to achieve a good correlation. These factors likely influence this response due to their role in the material structure, as an increase in the content of fibrous compounds can reduce the material’s digestibility due to the low degradation potential of fiber compared to the protein fraction [

20].

The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), although relatively new in forage-related studies, has shown promising results for the sector [

21]. Its advantage lies in the ability to model nonlinear patterns and capture subtle interactions among chemical composition variables (CP, NDF, ADL) that influence digestibility. In this study, both MLP and LR achieved comparable performance for leaf prediction (r = 0.76 for composition inputs), confirming that chemical composition provides the main predictive signal for digestibility and that both models are suitable for application in forage systems under similar experimental conditions.

However, REPTree showed the weakest performance. REPTree builds single-tree models using information gain/variance and applies reduced-error pruning. The pruning step can remove branches that capture subtle continuous trends, which leads to loss of information in datasets with high biological variability, multicollinearity and continuous quantitative predictors, exactly the characteristics of forage composition and canopy metrics in our dataset. and moderate sample size likely resulted in over-pruning and underfitting by REPTree. Importantly, REPTree can perform well in contexts where relationships are more deterministic and low-noise, for example, some hydrological or climatic applications [

22], but it is less suited to complex biological systems unless supported by much larger, less noisy datasets or by ensemble variants.

Regarding sample size and limitations: the dataset (n = 42 observations per fraction) is moderate. It is sufficient for training and cross-validation of traditional models (LR) and moderately complex models (MLP), especially when combined with repeated k-fold validation, but it is limited for fully exploiting highly parametric or deep architectures and for ensuring broad external generalization.

Therefore, the models developed in this study should be applied only under conditions similar to those in which the data were collected, that is, for Ipyporã grass managed under nitrogen fertilization levels and grazing regimes. For extrapolation to other cultivars, nitrogen levels, or production environments, additional validation and model retraining are required.

Some sources of prediction error may arise from laboratory measurement variability in IVOMD and chemical analyses, as well as within-paddock heterogeneity in canopy structure. However, the PCA and variable-importance analyses indicate that the dominant predictive signals are crude protein and fibre-related variables, which provides biological interpretability to the models.

From an application standpoint, our results indicate that reliable, low-cost prediction of forage digestibility is feasible when chemical composition is available. Practically, this can reduce reliance on labor-intensive in vitro assays for routine monitoring, support decision-making on fertilization and grazing management, and facilitate screening in breeding programs.

The integration of remote sensing and UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicle) technologies represents a promising advancement for enhancing digestibility prediction [

23]. Combining these non-destructive measurements with chemical composition data can improve model accuracy and enable large-scale monitoring of forage quality under field conditions. Similar approaches have shown strong predictive performance in estimating crop productivity using high-resolution satellite data [

24,

25], highlighting the potential of remote sensing to enhance predictive modeling in agricultural systems.

The wide variability among grass genera and forage management systems prevents broad generalization of the models. However, expanding the dataset to include cultivars of the same species evaluated under different environmental and management conditions could improve model robustness and external applicability. Although the present dataset already reflects relevant field variability, a larger number of collected observations would further enhance model precision and reliability. Models trained with chemical composition data are particularly promising, as they can provide practical and reliable predictions of forage digestibility under comparable conditions. The identification of specific models optimally suited for leaf (MLP and LR) and stem (LR) digestibility predictions advances precision livestock farming by improving feed formulation accuracy.