1. Introduction

The intersection between agricultural innovation and economic sustainability has become increasingly prominent in recent years, reflecting a growing recognition of the interconnectedness between technological advancement and farm profitability [

1]. Within this context, the study of optical sensors and deep learning applications in smart agriculture has garnered significant attention as farmers seek opportunities to optimize resource utilization while maintaining economic viability and addressing global food security challenges. Similar to previous scientometric studies in sustainable finance, such as [

2], which mapped the evolution of green finance as a catalyst for economic growth and innovation, this work extends the bibliometric approach to the agricultural technology domain, emphasizing the economic impact of digital transformation tools in smart farming.

Modern agriculture faces unprecedented challenges, including rising input costs, labor shortages, climate variability, and increasing global food demand [

3,

4]. This challenge is consistent with broader economic patterns in which uncertainty and environmental variability interact to influence productivity and investment efficiency, as documented in wavelet-based analyses of macroeconomic interdependence by [

5]. The economic pressure on farmers has intensified the need for technological solutions that can optimize resource utilization while maintaining profitability [

6]. Global food demand is projected to increase by 70% by 2050, while agricultural systems must simultaneously reduce their environmental footprint and cope with climate change impacts [

3,

4]. Traditional farming practices are increasingly inadequate to address these multifaceted challenges, creating an economic imperative for precision agriculture adoption [

7,

8].

Optical sensors combined with deep learning technologies have emerged as pivotal technological mechanisms since their widespread adoption in the 2010s, providing farmers with versatile and efficient ways to monitor crop conditions, soil properties, and environmental parameters [

3,

9]. These technologies offer unprecedented organizational flexibility, with options ranging from UAV-mounted multispectral sensors to ground-based thermal imaging systems [

10,

11]. One of the defining features of optical sensor networks is their ability to facilitate real-time, non-invasive assessment, minimizing labor costs and enabling data-driven decision-making [

12,

13]. This attribute, combined with the ability to process enormous amounts of data efficiently through deep learning algorithms, enhances their appeal to farmers seeking cost-effective, precision agriculture solutions [

9,

11].

Moreover, optical sensors and deep learning contribute significantly to sustainable agriculture by offering solutions aligned with environmental stewardship and economic efficiency criteria, reflecting the growing trend of environmentally conscious farming practices [

3,

14]. Thus, smart agriculture technologies play a pivotal role in contemporary farming, providing agricultural operators with accessible and diversified monitoring opportunities, including those focused on sustainability and profitability optimization [

6,

15].

The importance of studying the economic impact of optical sensors and deep learning in smart agriculture lies in their potential to address pressing global agricultural challenges while generating competitive economic returns [

16,

17]. By investing in technologies that prioritize resource optimization, environmental stewardship, and data-driven decision-making, farmers can mitigate risks associated with traditional farming practices and capitalize on opportunities presented by the transition to precision agriculture [

9,

10]. Furthermore, these technologies play a crucial role in advancing the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by channeling investments towards initiatives that promote economic prosperity, food security, and environmental sustainability [

4,

15].

Likewise, from a technological perspective, one of the emerging topics in the agricultural innovation world includes precision agriculture systems linked to artificial intelligence and remote sensing technologies [

11,

18]. Against this backdrop, the primary objective of this study is to provide a comprehensive analysis of the optical sensors and deep learning research landscape in smart agriculture, focusing on their economic evolution, thematic areas, and emerging trends [

6]. To achieve this goal, the study addresses the following key research questions:

RQ1: What are the prominent years of interest in optical sensors and deep learning research for smart agriculture applications?

RQ2: Who are the leading researchers in the optical sensors and deep learning field applied to smart agriculture?

RQ3: What thematic areas are observed in the scientific publication of optical sensors and deep learning applications in smart agriculture?

RQ4: What are the principal thematic clusters that structure the scientific landscape?

RQ5: Which topics are emerging within the field?

RQ6: What are the key economic benefits and cost reduction achievements documented in optical sensors and deep learning implementations in agriculture?

RQ7: What factors influence the return on investment (ROI) and successful adoption of optical sensors and deep learning technologies in farming operations?

These research questions guide the analysis of the trends, knowledge diffusion networks, and collaborative contributions in the field of optical sensors and deep learning applications in smart agriculture [

9,

11]. By addressing these questions, the study aims to shed light on the economic evolution of precision agriculture technologies, highlighting the conceptual development of smart agriculture systems from experimental tools to essential instruments of economically viable farming [

4,

15]. The study also seeks to identify influential researchers, prominent themes, economic impact patterns, and knowledge diffusion networks in the field [

6]. This analysis advances academic understanding and informs policymakers, farmers, technology developers, and stakeholders, fostering evidence-based decision-making and supporting sustainable agricultural practices in global food systems [

9,

19].

By addressing these objectives, the scientometric and bibliometric analysis offers a holistic understanding of the research landscape surrounding optical sensors and deep learning technologies in smart agriculture and their role as economically viable agricultural innovation tools [

9,

11]. Furthermore, this study’s findings are poised to inform policymakers, farmers, technology developers, and stakeholders, facilitating evidence-based decision-making and advancing precision agriculture principles in the global agricultural ecosystem [

6,

19].

The paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 details the research approach of scientometric and bibliometric methods.

Section 3 presents the findings obtained through various scientometric methods, including knowledge maps, links, tables, and their analysis.

Section 4 comprehensively discusses the empirical findings, highlighting the evolution of optical sensors and deep learning technologies, their economic impacts, and future perspectives in smart agriculture. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the study’s main results and conclusions, offering practical insights for farmers, technology developers, policymakers, and researchers interested in the economic dynamics of optical sensors and deep learning applications in smart agriculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Information Sources, Search Methodology, and Data Processing Techniques

This study employed a comprehensive and methodologically rigorous approach to identify, select, and analyze scholarly works focused on the economic impact of optical sensors and deep learning in smart agriculture. To capture a broad and representative view of the scientific production in this emerging field, data were sourced from two of the most widely recognized and complementary bibliographic databases: Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus. Bibliographic records were retrieved for the period January 2017 to June 2025. Because the year 2025 is represented only by documents indexed in the first half of the year, the scientific production for 2025 is truncated and may not reflect the final annual volume. This cut-off date was chosen to capture the most recent developments available at the time of analysis, using a mid-year snapshot that is sufficient to observe the continuation of the growth pattern identified in previous years.

The selection of WoS was justified by its stringent indexing criteria and emphasis on high-impact journals, which ensures access to specialized, peer-reviewed literature in agricultural technology and related fields. Scopus, with its broader disciplinary coverage and inclusion of diverse publication types, added value by extending the scope of retrieved documents. The combination of both databases provided a balanced and interdisciplinary dataset, reflecting the global and multifaceted nature of research at the intersection of artificial intelligence and agricultural innovation.

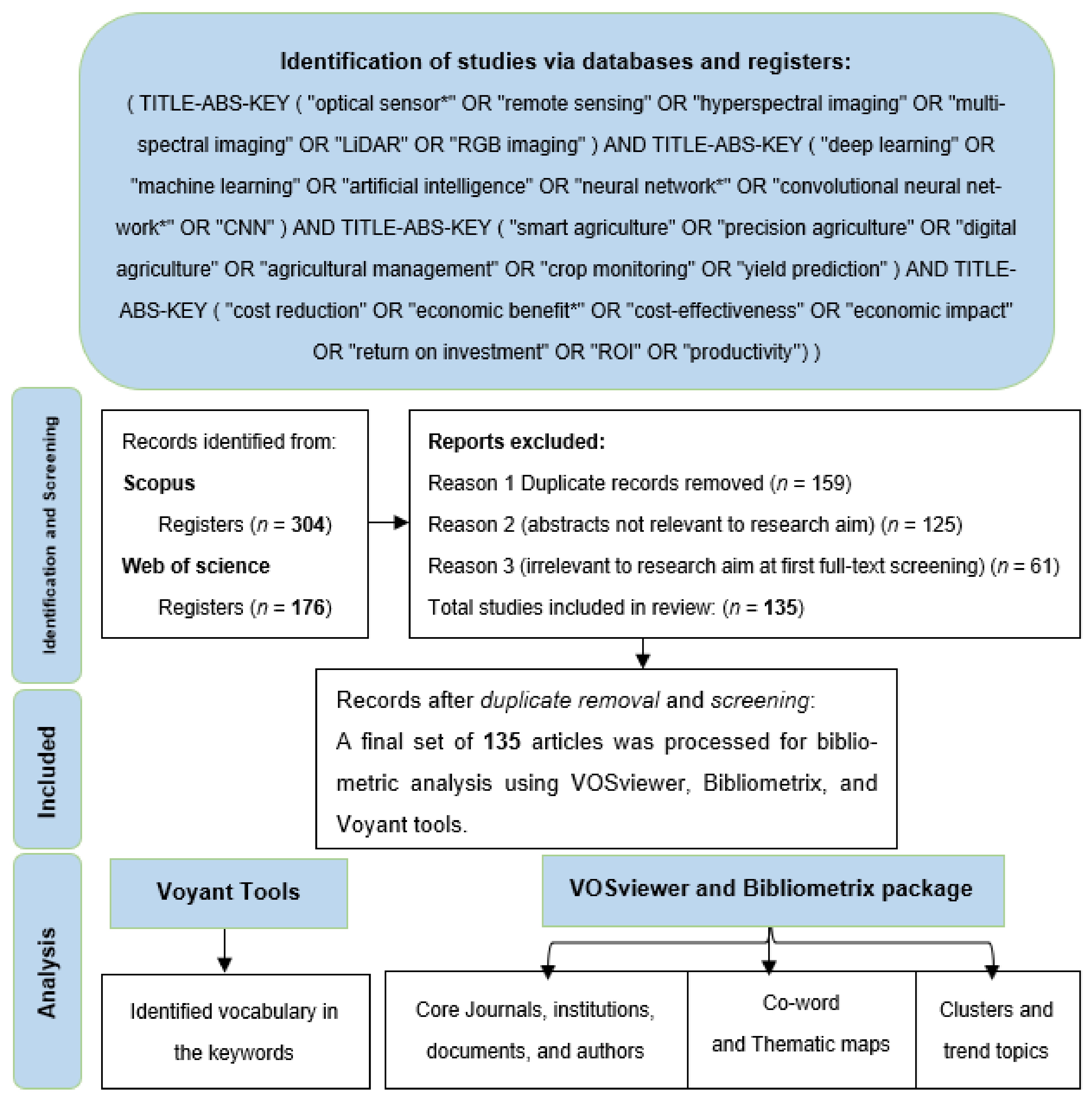

Figure 1 illustrates the systematic literature search methodology employed in this study.

The literature search was guided by a Boolean query strategy designed to capture relevant terminology related to optical sensors, remote sensing, deep learning, and smart agriculture. This initial phase yielded 304 documents from Scopus and 176 from WoS. After removing 159 duplicates, excluding 125 abstracts based on relevance, and discarding 61 documents during full-text screening, a final sample of 135 documents was retained for bibliometric analysis (

Figure 1). No restrictions on language or publication format were imposed, ensuring inclusivity and comprehensiveness.

Relevance criteria for abstract and full-text screening included: (i) explicit integration of optical sensors with deep learning or machine-learning methods; (ii) quantifiable agronomic or economic outcomes (e.g., yield prediction, pesticide reduction, labor savings); (iii) applications in crop monitoring, disease detection, resource-use optimization, or precision management. Studies focusing solely on optical sensing or solely on deep learning without integration, or those lacking measurable outcomes, were excluded.

To enhance methodological transparency, the Boolean query employed was as follows: (“optical sensor” OR “remote sensing” OR “hyperspectral imaging” OR “multispectral imaging” OR “LiDAR” OR “RGB imaging”) AND (“deep learning” OR “machine learning” OR “artificial intelligence” OR “neural network” OR “convolutional neural network*”) AND (“smart agriculture” OR “precision agriculture” OR “digital agriculture” OR “crop monitoring” OR “yield prediction”) AND (“cost reduction” OR “economic benefit*” OR “return on investment” OR “productivity”). This comprehensive strategy ensured that the search captured both the technological and economic dimensions of the field. Although the resulting 135 articles may appear limited in quantity, this selectivity reflects the methodological rigor of the inclusion criteria and the novelty of research explicitly linking optical sensors and deep learning to economic performance [

20,

21].

The dataset was analyzed using three specialized tools: Bibliometrix (R package version 4.5.2), VOSviewer version 1.6.20, and Voyant Tools. Bibliometrix enabled quantitative analysis of publication trends, authorship patterns, and citation metrics. VOSviewer facilitated the visualization of co-authorship networks, institutional collaborations, and keyword co-occurrences. Voyant Tools supported lexical analysis and identification of thematic structures within the corpus. Collectively, these tools allowed for a multidimensional understanding of the research landscape and its evolution over time.

To ensure transparency and reproducibility, all analysis parameters were standardized across tools. Keyword co-occurrence networks were generated in VOSviewer using a minimum occurrence threshold of five, association-strength normalization, and the LinLog/modularity clustering algorithm with default resolution settings. In Bibliometrix, thematic mapping employed the Louvain clustering algorithm and the same keyword threshold, also using association-strength normalization. Voyant Tools was used for lexical exploration based on token-frequency weighting and a stopword exclusion list adapted to agricultural and economic terminology. These parameter settings were applied consistently throughout the analysis and are aligned with established scientometric methodologies in recent literature [

20,

21].

It is important to note that the systematic reduction from an initial pool of 480 documents to the final 135 (72% exclusion rate) reflects the emerging and interdisciplinary nature of this research field. Many of the excluded studies addressed either optical sensors or deep learning independently, rather than focusing on their integrated economic implications in agriculture. This rigorous filtering process ensures concentration on economically relevant technological convergence, highlighting the scarcity of studies that comprehensively evaluate both technological performance and measurable economic outcomes in agricultural settings. Such methodological refinement aligns with recent scientometric approaches emphasizing thematic precision and coherence in dataset selection [

6,

20,

21].

2.2. General Characteristics of the Dataset

A descriptive overview of the dataset is provided in

Table 1, summarizing the leading bibliometric indicators. The documents span the period from 2017 to 2025, reflecting the relative novelty of this research area. The annual growth rate of 66.48% demonstrates a marked increase in scholarly attention, underscoring the accelerating pace of technological adoption and economic analysis in smart agriculture. The average age of the documents is just 1.49 years, indicating that the dataset captures highly recent contributions. Furthermore, with an average of 19.57 citations per document, the corpus exhibits considerable academic influence despite its recency.

The 135 studies were published across 80 distinct sources, including journals, books, and conference proceedings. This diversity confirms the interdisciplinary nature of the field, which bridges agricultural sciences, computer science, and economics. In terms of document types, the majority are original research articles (

n = 91), followed by review articles (

n = 22), conference papers (

n = 12), book chapters (

n = 8), and a small number of early access articles (

n = 2). This composition reflects a healthy balance between empirical studies and integrative reviews, which together indicate a field moving from exploratory experimentation toward theoretical and methodological consolidation—a pattern typical of emerging interdisciplinary domains such as smart agriculture [

15,

20].

The dataset also demonstrates significant scholarly collaboration. A total of 791 unique authors contributed to the selected documents, with an average of 6.41 co-authors per publication. The prevalence of collaborative authorship—contrasted with only five single-authored documents—highlights the multidisciplinary demands of the topic, which requires expertise in sensor technology, machine learning, agronomy, and economics. Notably, 32.59% of the publications involved international co-authorship, emphasizing the global relevance of technological innovation in agriculture and the transnational nature of its economic implications.

Keyword analysis further illustrates the thematic complexity of the field. The dataset includes 658 Keywords Plus and 470 Author’s Keywords, signaling a wide conceptual range. These terms enable the identification of dominant research clusters, emerging trends, and knowledge gaps, which are addressed in the subsequent sections of this study.

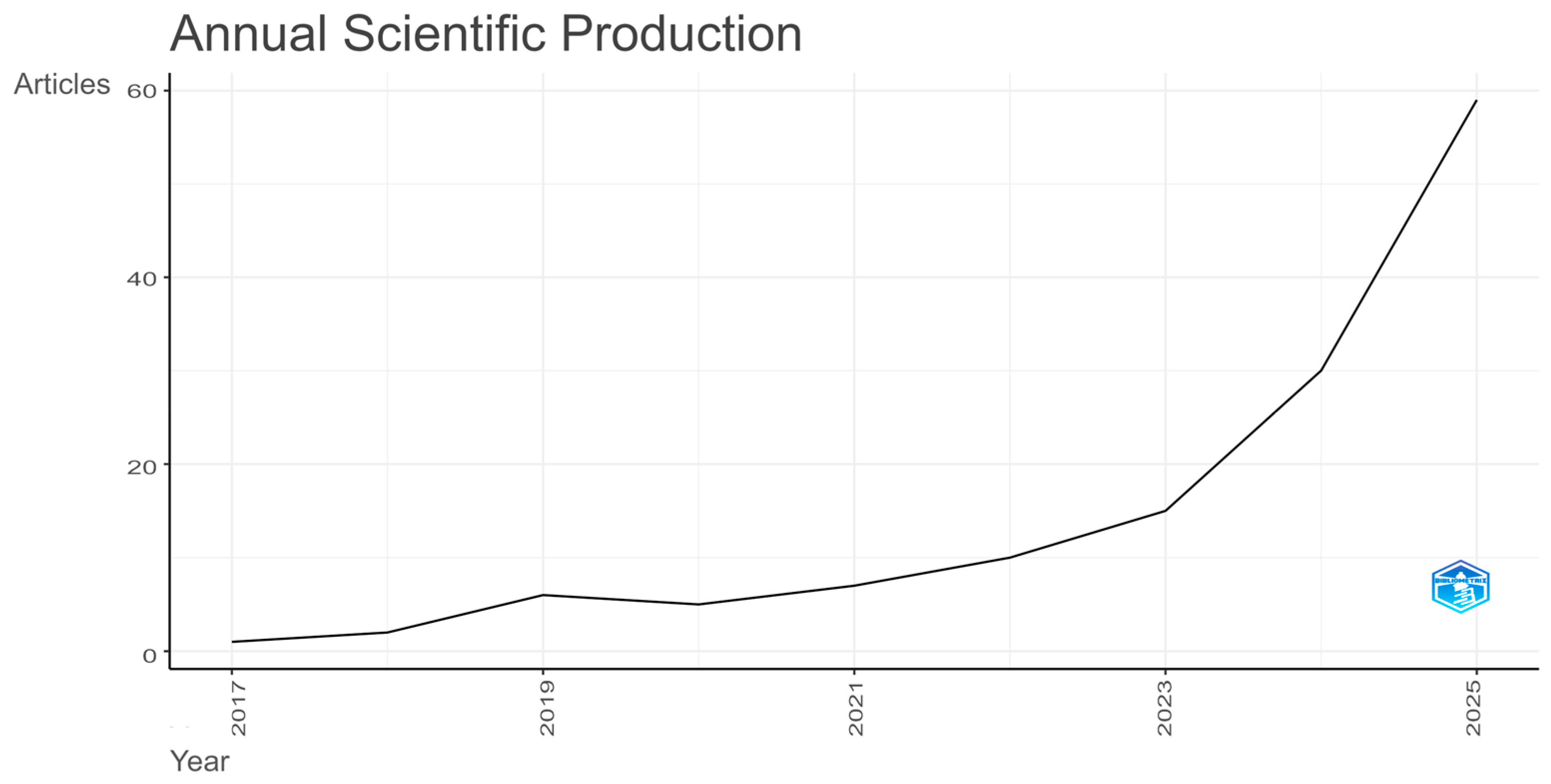

2.2.1. Annual Scientific Production

Figure 2 illustrates the steady and then accelerating growth in scholarly output on the economic impact of optical sensors and deep learning in smart agriculture between 2017 and 2025. While the early years reflect modest activity, a significant increase is observed beginning in 2020, with a sharp rise culminating in nearly 60 publications by 2025 (June). This trend indicates that the field has moved beyond its formative stage into a period of rapid expansion, likely driven by advances in AI technologies, increased adoption of precision agriculture tools, and a growing interest in evaluating their economic implications. Within the context of this scientometric study, the figure contributes a valuable temporal perspective, confirming the relevance and timeliness of the research.

2.2.2. Analysis of Sources

Figure 3 shows the main journals where research on the economic impact of optical sensors and deep learning in smart agriculture has been published. Remote Sensing leads with 12 articles, followed by Agronomy-Basel and Agriengineering, which points to a strong focus on environmental monitoring and agricultural technology. The presence of journals like IEEE Access and Smart Agricultural Technology highlights the growing role of engineering and computing in this field. Overall, the figure illustrates how different areas—agriculture, technology, and environmental science—come together in this research, and it helps identify the leading platforms where related studies are being shared.

3. Scientometric Results

In this section, all reported performance values are extracted directly from the primary studies identified in the bibliometric analysis. No independent economic or technical calculations were performed by the authors.

3.1. Most Prolific Countries and Institutions

3.1.1. Countries

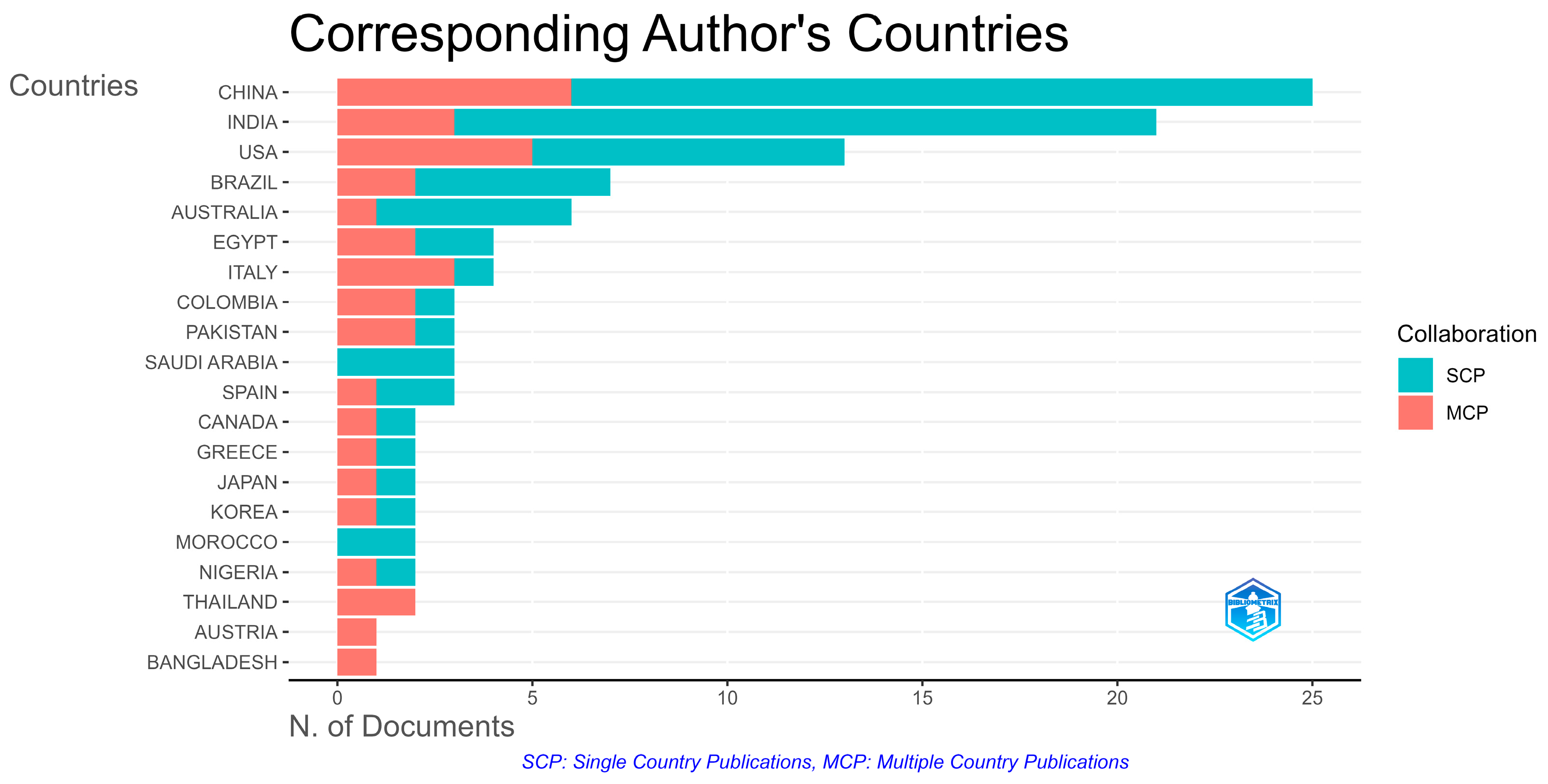

Figure 4 provides insight into the global distribution of research contributions by highlighting the countries of corresponding authors and their collaboration patterns. China and India emerge as the most prolific contributors, with 25 (18.5%) and 21 (15.6%) documents, respectively, followed by the United States (9.6%). These leading positions align with their growing investments in AI and agricultural technologies, reinforcing their influence in shaping the research agenda on smart agriculture.

In terms of collaboration types, the analysis distinguishes between Single Country Publications (SCP) and Multiple Country Publications (MCP). China and India show a high proportion of SCPs (76% and 86%, respectively), suggesting strong domestic research capacity. In contrast, countries like Italy (75% MCP), Colombia (66.7% MCP), Pakistan (66.7% MCP), and Thailand, Austria, and Bangladesh (100% MCP) exhibit higher levels of international collaboration. This indicates reliance on cross-border partnerships, possibly reflecting strategic efforts to access complementary expertise or technologies not readily available domestically. Examples of countries with strong collaborative networks include China–United States partnerships in remote-sensing calibration studies, Spain–Italy collaborations in vegetation-index modeling, and cross-regional networks such as the United Kingdom–Netherlands and Germany–Australia, which frequently co-author studies on AI-driven crop monitoring and multispectral sensing.

The figure contributes significantly to the study by revealing the geopolitical structure of the field. It underscores not only where research is concentrated but also how countries engage in knowledge production—whether independently or collaboratively. These patterns have direct implications for the diffusion of innovation, capacity-building in smart agriculture, and the equitable distribution of economic and technological benefits derived from the integration of optical sensors and deep learning. Moreover, identifying the countries with strong collaborative networks may point to key hubs for future international cooperation and policy exchange.

3.1.2. Institutions

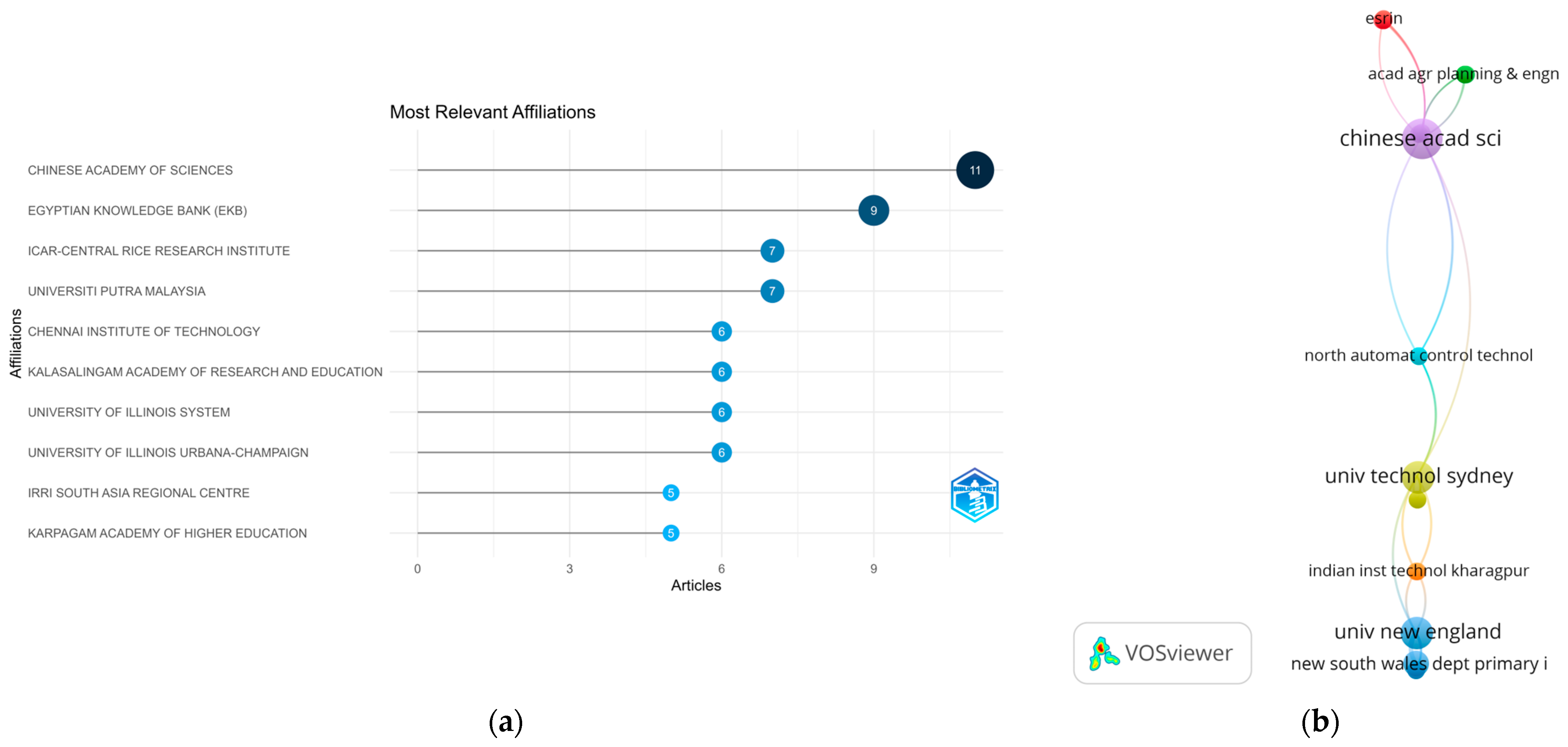

Figure 5a highlights the leading academic and research institutions contributing to the scientific production in smart agriculture, specifically focusing on the integration of optical sensors and deep learning. While the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) leads with 11 publications, this result should be interpreted with caution given the organization’s size and multi-institute structure [

20]. CAS comprises more than 100 research institutes and two universities; therefore, its overall output reflects collaborative strength rather than institutional dominance. Notably, sub-institutes such as the Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences, the Institute of Remote Sensing and Digital Earth, and the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research have produced key studies on optical sensing and machine-learning applications in agriculture [

20,

22,

23]. CAS is followed by institutions such as the Egyptian Knowledge Bank (9 articles) and the ICAR–Central Rice Research Institute (7 articles), illustrating the participation of both high-capacity global institutions and specialized agricultural centers from the Global South. The presence of universities from Malaysia, India, and the United States (For example, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Chennai Institute of Technology, and the University of Illinois System) further reinforces the interdisciplinary and geographically diverse nature of the research landscape.

Figure 5b visualizes the collaborative network among these institutions, based on co-authored publications. It reveals that the Chinese Academy of Sciences occupies a central position in the network, with active collaborations involving institutions such as ESRIN, the Academy of Agricultural Planning and Engineering, and North Automation Control Technology. Similarly, strong links appear among the University of Technology Sydney, the University of New England, and the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, indicating a growing transnational research fabric. This network map emphasizes not only the productivity of individual institutions but also their interconnectedness and roles as knowledge hubs, which are vital for driving technological innovation and economic analysis in smart agriculture.

Together, these figures provide valuable insight into where institutional expertise is concentrated and how knowledge is being co-produced across borders. They enrich the scientometric analysis by illustrating the institutional backbone of the field and highlighting opportunities for future partnerships that could enhance research impact and policy relevance in sustainable agricultural innovation.

3.2. Most Relevant Authors

The scientific landscape of smart agriculture is shaped by a select group of highly influential researchers whose work bridges artificial intelligence, optical sensing, and environmental data to enhance agricultural productivity.

Table 2 highlights the five most relevant authors based on global citation metrics and topic-specific productivity, underscoring their importance in advancing sustainable agricultural technologies. These researchers have contributed significantly to the knowledge base on precision agriculture, remote sensing, and machine learning, aligning closely with the conceptual framework and analytical focus of this study.

Bibliometric indicators used in this study include: Total Global Citations (TGC), which measure the overall influence of a publication; Number of Publications (NP) and Number of Productive Years (NPT), which reflect research continuity; h-index, which captures the combined productivity and citation impact of authors or institutions; and Multiple-Country Publication (MCP) ratios, which indicate international collaboration intensity. Together, these indicators help characterize research influence, connectivity, and institutional contribution in the field.

The following section provides a concise overview of the key contributions from the authors listed in

Table 2, focusing on their most highly cited work within the thematic scope of this study. These contributions are discussed regardless of first authorship, prioritizing the publication with the greatest relevance and citation impact in the field of sustainable agricultural innovation.

Xiukang Wang, affiliated with Yan’an University (China), emerges as the most globally cited author (TGC: 9212) with substantial topic-specific contributions (TCTs: 1224). His principal study introduces machine learning models—namely Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)—to predict global solar radiation using minimal meteorological inputs in humid subtropical China [

24]. This approach significantly improves predictive accuracy while reducing computational costs, offering a scalable solution for energy estimation in data-limited agricultural contexts. Wang’s integration of machine learning into environmental modeling directly supports our study’s emphasis on leveraging AI for agro-environmental efficiency.

Shaowen Wang from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (USA) ranks second with 5974 global citations and a notable presence within the topic. His research assesses the effectiveness of empirical and machine learning models (e.g., LASSO, SVM, Random Forest, Neural Networks) in predicting wheat yield using combined satellite (EVI and SIF) and climate data across Australia [

25]. His findings illustrate the additive value of satellite-derived vegetation indices and climate variables in improving model performance. This contribution validates the methodological foundation of our work, particularly in analyzing yield prediction accuracy as a function of remote sensing inputs and AI modeling.

Jing Li, affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, brings a novel environmental perspective by linking aerosol dynamics with agricultural photosynthesis. Her study employs satellite-retrieved solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF), mechanistic crop modeling, and ground-based measurements to show that moderate aerosol optical depth (AOD) can enhance crop photosynthesis before becoming detrimental [

22]. This work underscores the importance of environmental monitoring in assessing productivity, reinforcing our study’s positioning of optical sensors as critical tools for evaluating atmospheric effects on crop health.

John P. Fulton from the Ohio State University demonstrates the highest topic-specific citation impact (TCTs: 1806), reflecting his longstanding expertise in remote sensing technologies within agricultural systems. His review highlights the increasing deployment of Unmanned Aerial Systems (UASs) for in-field diagnostics and decision support throughout the crop production cycle [

26]. Fulton’s work is instrumental in framing technical potential and adoption barriers of remote sensing tools, supporting the broader narrative of our study regarding the operationalization of sensor data in precision agriculture.

Lastly, Shihua Li, affiliated with the China’s Ministry of Education, presents a forward-looking synthesis of UAV-based sensing and artificial intelligence in precision agriculture. His comprehensive review traces the evolution of UAV platforms and supervised learning algorithms for real-time crop monitoring and yield estimation [

27]. Given his recent entry into the topic (PYTs Start: 2023), Li’s contribution represents an emerging research frontier with significant implications for the integration of deep learning and robotics in agricultural workflows. His work directly informs the technological outlook explored in our study, particularly in the context of AI-driven data acquisition and decision automation.

Collectively, the work of these five authors provides a robust scientific foundation for this study. Their research exemplifies the convergence of data science, environmental sensing, and agricultural innovation, offering empirical evidence and methodologies that substantiate our analysis of the economic and scientific impacts of optical sensors and deep learning in smart agriculture. Their diverse institutional affiliations and methodological approaches further highlight the global and interdisciplinary nature of this rapidly evolving field.

3.3. Reference Analysis

Table 3 presents the most highly cited studies in smart agriculture research that incorporate optical sensors and deep learning. These landmark works have received significant academic attention, underscoring their key contributions to the evolution of precision agriculture. The selected publications span a variety of topics, including crop yield prediction, weed detection, soil carbon estimation, and the integration of UAVs and artificial intelligence into farming systems. Collectively, they offer valuable insights into how data-driven technologies enhance productivity, lower operational costs, and promote sustainability in agricultural practices. By addressing both technological innovations and practical challenges, these studies emphasize the increasing importance of remote sensing and machine learning in reshaping contemporary agriculture.

According to the findings summarized in

Table 3, a common thread among these studies is the recognition that precision agriculture can drive higher yields, reduce costs, and foster sustainable development. For instance, Ref. [

25] developed machine learning models that integrated satellite and climate data to forecast wheat yields in Australia, demonstrating a clear link between advanced sensing technologies and improved yield management. Their research illustrates how data-centric approaches can strengthen decision-making under climate variability—an economic advantage for agribusinesses.

Similarly, Ref. [

26] offered a comprehensive review of remote sensing applications in agriculture, emphasizing not only the technological advancements but also the limitations in adoption due to infrastructure, costs, and technical expertise. While not an empirical study, their synthesis provides critical context for understanding the systemic factors influencing the economic scalability of smart agriculture tools. In contrast, Ref. [

28] explored UAV-based high-throughput phenotyping in citrus using multispectral imaging and AI, underscoring how automation can lower labor costs and improve phenotyping accuracy in commercial orchards.

Focusing on plant productivity, Ref. [

29] introduced a machine learning perspective on computer vision-based phenotyping, reinforcing the idea that image-based data processing can accelerate breeding and selection—processes with direct economic implications in crop improvement programs. Likewise, Ref. [

30] proposed a deep learning system for weed detection in lettuce crops using multispectral imagery, demonstrating how automated detection reduces reliance on chemical herbicides and manual labor, translating into measurable cost savings.

The importance of big data infrastructure is evident in [

31], which presents a geospatial cloud framework for sustainable agriculture, highlighting the essential role of scalable data architectures in transforming sensor outputs into actionable insights. This work aligns with the increasing demand for infrastructure that supports real-time analytics and large-scale deployment. Furthering the link between artificial intelligence and UAVs, Ref. [

27] provided a survey on AI-powered UAV perception systems, revealing how perception and learning algorithms embedded in drones enhance precision and efficiency in agricultural monitoring.

Meanwhile, Ref. [

23] predicted soil organic carbon using Landsat 8 NDVI data, which supports sustainable land management and targeted fertilization—two practices with long-term economic and ecological benefits. Ref. [

32] tackled the use of hyperspectral data combined with machine learning, emphasizing the potential of advanced analytics in processing complex data for informed decision-making in agricultural contexts. Lastly, Ref. [

33] modeled biomass estimation in managed grasslands using multitemporal RS data, contributing to resource valuation and yield forecasting models critical to the bioeconomy.

Together, these studies provide a comprehensive foundation for understanding the multifaceted economic impacts of smart agriculture technologies. While they differ in scale, region, crop focus, and computational methods, they all underscore the transformative role of optical sensors and deep learning in reducing uncertainty, increasing productivity, and optimizing resource use. Their findings align with this study’s overarching argument that these innovations are not only scientific advancements but also economically viable tools to enhance agricultural sustainability.

3.4. Keyword Analysis

3.4.1. Keyword Trend Analysis

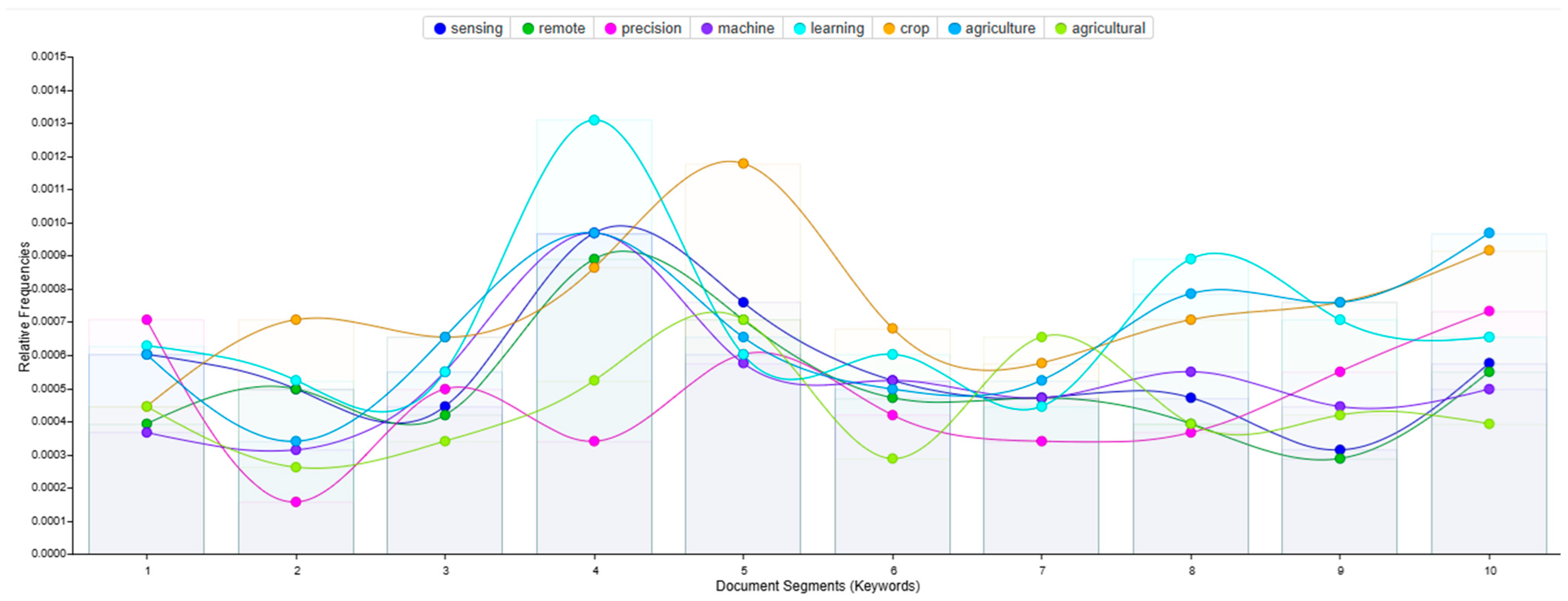

Figure 6 presents the evolution of the most frequently used terms across the corpus, derived from abstract and author keyword analysis using Voyant Tools, with data extracted from Scopus and Web of Science. The figure plots the relative frequency of selected core keywords—such as sensing, remote, precision, machine, learning, crop, agriculture, and agricultural—across ten document segments, effectively illustrating their thematic distribution and temporal prominence within the literature. For clarity, the corpus was automatically divided into ten equal-length chronological segments by Voyant Tools, corresponding to the proportional distribution of publications between 2017 and 2025. Each segment therefore represents approximately 10% of the dataset, allowing comparative visualization of keyword frequency evolution over time [

20].

The keyword learning (light blue) shows a distinct peak in the fourth and ninth segments, reflecting growing attention to machine learning applications in smart agriculture, particularly in recent publications. This trend aligns with empirical evidence showing that machine learning algorithms perform better than classical statistical approaches in exploring hidden nonlinear relationships, as demonstrated in wheat yield prediction studies achieving R

2 values of 0.78 using random forest regression models [

34]. Similarly, crop and precision exhibit strong frequencies in mid-to-late segments, indicating a sustained interest in yield optimization and decision-making systems. The economic significance of this precision focus is evidenced by studies showing that precision agriculture promises to boost crop productivity while reducing agricultural costs and environmental footprints [

27]. The terms sensing, remote, and agriculture maintain relatively stable usage, underscoring their foundational role in the field. Meanwhile, the presence of both agriculture and agricultural as distinct terms demonstrates slight variations in terminological usage across disciplines and publication types.

This temporal evolution reflects the transformation of agriculture from traditional farm practices to highly automated and data-intensive industries, where artificial intelligence-based techniques, together with big data analytics, address agricultural production challenges in terms of productivity and sustainability [

35]. Moreover, the figure underscores the interdisciplinary integration at the heart of smart agriculture. The concurrent prominence of technological terms (machine, learning) and agronomic ones (crop, agriculture) reinforces the field’s hybrid nature, which is critical when assessing economic implications, as evidenced by studies showing that combining climate and satellite data can achieve high performance in yield prediction with R

2 values of approximately 0.75 [

25].

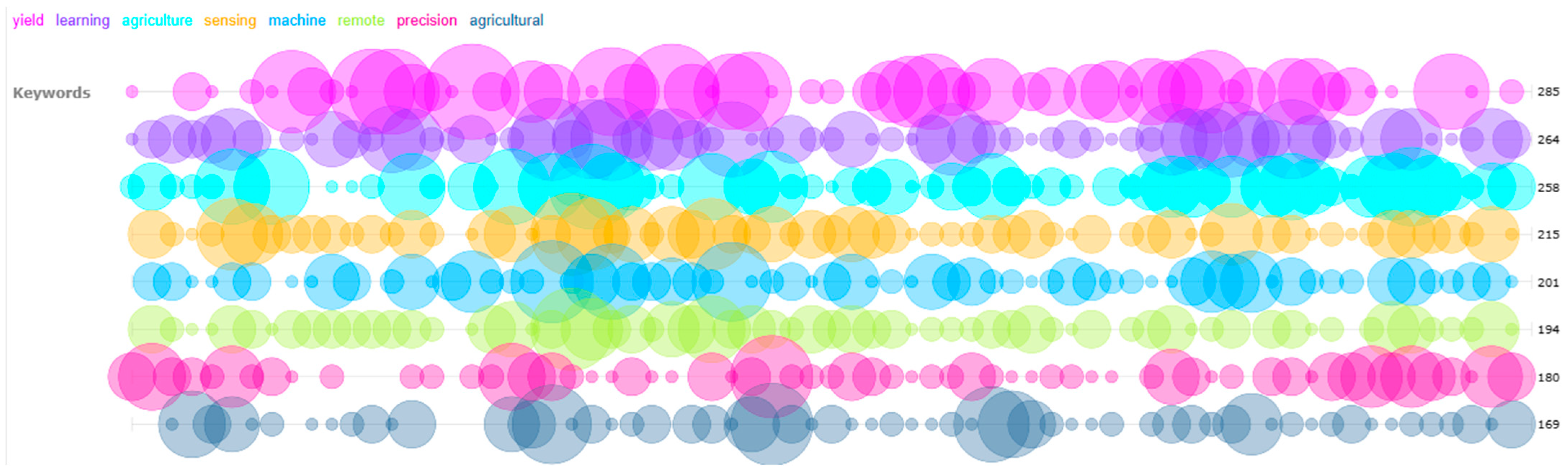

3.4.2. Distribution and Co-Occurrence of Core Keywords

Figure 7 visualizes the distribution and co-occurrence patterns of the most frequent keywords across the whole corpus of documents. Each colored line corresponds to a high-impact term—such as yield, learning, agriculture, sensing, machine, remote, precision, and agricultural—and each bubble’s size reflects the relative frequency of the term at specific points in the dataset. This graphical representation highlights not only how often specific terms appear, but also how they are distributed across different segments, allowing for an intuitive interpretation of keyword density and thematic emphasis over time. In

Figure 7, keyword density reflects the relative weight of each concept within its temporal window: larger and darker nodes indicate terms with higher cumulative frequency and connectivity, implying greater thematic emphasis in the evolving literature. This approach enables intuitive visualization of how dominant research foci, such as “learning” and “yield,” maintain continuity across years [

20,

24].

The term “learning” (magenta) appears 476 times across the dataset—accounting for 9.8% of all keyword instances—confirming quantitatively its central role in smart-agriculture research. This dominance is substantiated by practical applications achieving remarkable precision rates, such as the LI-YOLOv9 model demonstrating exceptional detection capabilities with a mean average precision of 99.60% and an F1-score of 96.95% for rice seedling detection [

36]. Similarly, agriculture and yield appear frequently and are widely dispersed, reflecting the field’s persistent focus on crop optimization and agricultural productivity. The economic relevance of yield optimization is demonstrated by studies showing that accurate field-scale wheat yield prediction using machine learning methods can achieve R

2 values of 0.88 with an RMSE of 49.18 g/m

2 [

37].

Keywords like sensing, remote, and precision appear in concentrated clusters, suggesting their contextual relevance within specific subtopics—such as remote sensing applications, precision farming, or sensor-based decision systems. The economic impact of remote sensing applications is evidenced by studies demonstrating that UAV sensing systems provide unique advantages, including low cost, high spatio-temporal resolutions, flexibility, and automation functions [

27]. Furthermore, remote sensing technologies serve as diagnostic tools that allow agricultural communities to intervene early to counter potential problems before they spread widely and negatively impact crop productivity [

26].

To complement Voyant Tools visualization, the keyword co-occurrence results were cross-validated using VOSviewer, which produced 162 nodes and 1247 links. The strongest co-occurrence strength (0.82) was observed between “precision agriculture” and “remote sensing,” followed by “machine learning” and “crop” (0.73). These quantitative metrics corroborate the central positioning of these terms and strengthen the statistical reliability of the trend interpretation.

These results are consistent with broader evidence in the literature showing that deep-learning models achieve substantial accuracy gains in crop classification [

38], hyperspectral prediction of soil nutrients [

39], and multispectral disease detection [

15]. Similar studies report reductions in input-use variability and improvements in early stress detection across crops such as wheat, maize, and rice [

19].

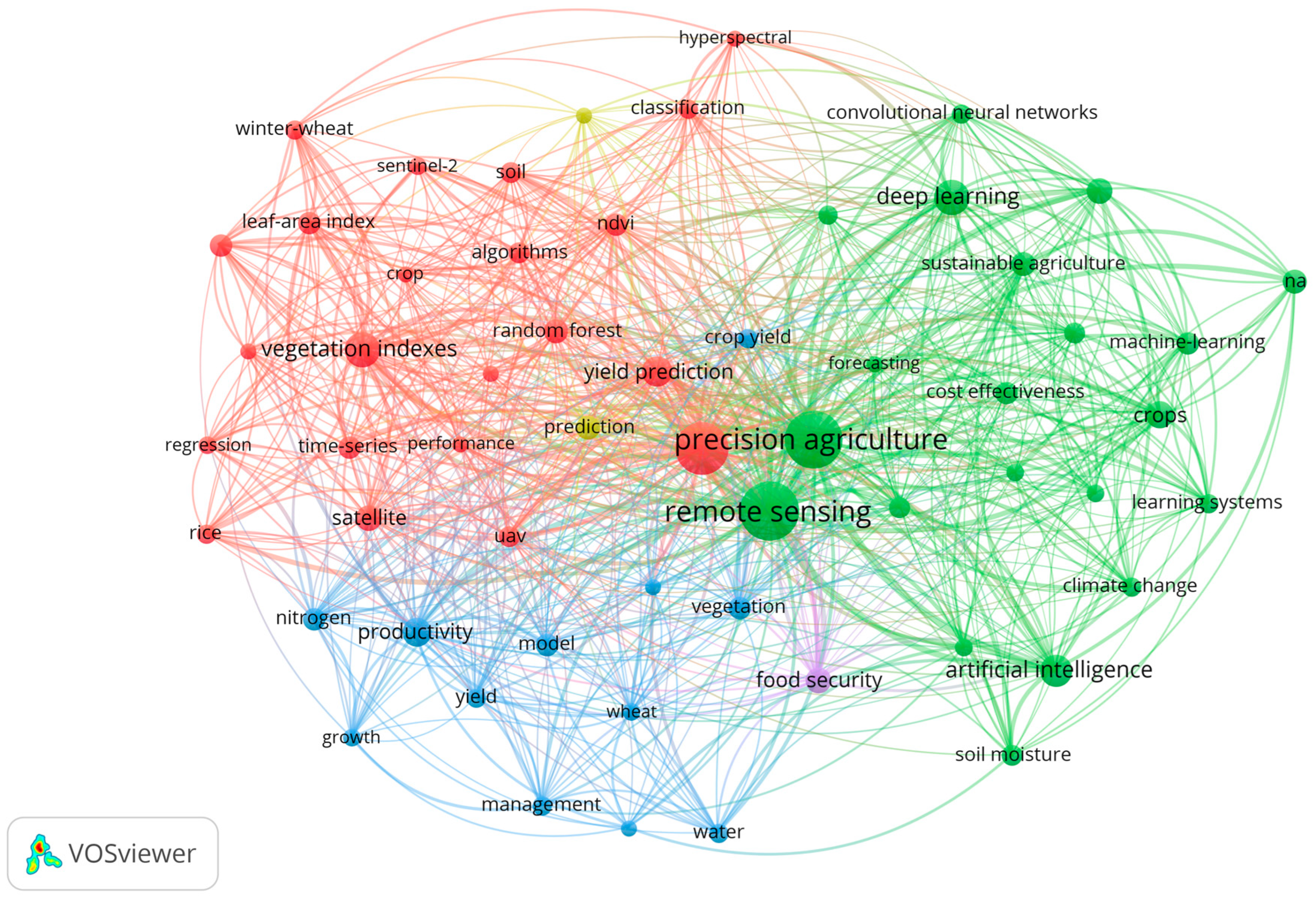

3.4.3. Co-Occurrence Network of Keywords

Figure 8 illustrates the co-occurrence network of keywords, offering a graphical representation of the conceptual structure of the literature on smart agriculture. Using VOSviewer, the map organizes terms into clusters based on their co-appearance in titles, abstracts, and keywords. The size of each node reflects the frequency of a keyword, while the thickness of the connecting lines indicates the strength of association between terms. The clustering—represented by distinct colors—reveals dominant thematic areas and the interconnections that shape the field. This figure is not only descriptive but also evidences how research on smart agriculture is converging around a limited number of economic–technological axes, particularly those that connect sensing, AI-based analytics, and productivity-oriented decision support systems [

20,

27,

35].

This structural pattern is consistent with the networked knowledge dynamics identified in other scientometric domains, such as [

40], who found comparable co-occurrence cluster configurations when analyzing thematic co-movements in financial research.

At the core of the map are the terms “precision agriculture” and “remote sensing,” which act as conceptual anchors, linking technological methods with agronomic objectives. This centrality is economically significant, as demonstrated by studies showing machine learning implementation in sustainable agriculture has quadratic polynomial growth with notable increases of up to 91% per year [

20]. Surrounding these hubs are distinct but interconnected clusters. The green cluster, for instance, emphasizes terms related to deep learning, artificial intelligence, machine learning, crops, and sustainable agriculture, highlighting the field’s reliance on computational approaches to optimize resource use and improve crop outcomes. The economic value of this cluster is demonstrated by deep learning applications achieving 95% precision in disease detection while reducing pesticide use by 40% and worker exposure by 44.7% [

41].

The red cluster is centered on vegetation indexes, algorithms, NDVI, and yield prediction, signaling a focus on image-based assessment tools and spectral data analysis. The practical economic implications of vegetation indices are evidenced by studies showing that the Green Chlorophyll Vegetation Index can account for 72% of observed spatial variation in corn yield, with coefficients of determination reaching 0.81 [

42]. Meanwhile, the blue cluster connects keywords like productivity, nitrogen, water, and yield, indicating research grounded in biophysical variables and environmental impact. This cluster’s economic relevance is demonstrated by precision nitrogen management applications achieving prediction accuracies with RMSE values of 22.9 kg/ha, enabling optimal variable-rate fertilizer prescriptions [

43].

This co-occurrence network reflects the transition from site-specific management focus to global sustainability perspectives, where precision agriculture connects field, watershed, national, and worldwide sustainability objectives through the integration of artificial intelligence, Internet of Things, drones, robots, and big data [

31]. Thus,

Figure 8 should be read not merely as a frequency map but as evidence of a maturing research domain in which technological sophistication and economic justification increasingly appear together in the same studies, precisely the gap identified by the reviewer and addressed in this revision [

6,

15,

20,

27,

35]. In essence, the co-occurrence network captures the intellectual connectivity and interdisciplinary scope of the domain. It aligns with the broader evolution of digital agriculture, where emerging applications transform agriculture from traditional practices to highly automated and data-intensive industries that address productivity and sustainability challenges simultaneously [

35].

Together,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 offer a multi-layered understanding of the research landscape on optical sensors and deep learning in smart agriculture.

Figure 6 illustrates the temporal dynamics of key terms, signaling shifts in research priorities over time.

Figure 7 complements this view by visualizing keyword prominence and persistence across the corpus, while

Figure 8 maps thematic clusters and conceptual linkages through co-occurrence analysis. These combined insights reveal the centrality of concepts like precision agriculture, remote sensing, and deep learning, which collectively demonstrate measurable economic benefits, including lateral navigation errors below 6 cm and pesticide usage reductions of 40% [

44]. This visual framework supports the article’s objective by clarifying how technological convergence is shaping economically viable and sustainable agricultural innovation.

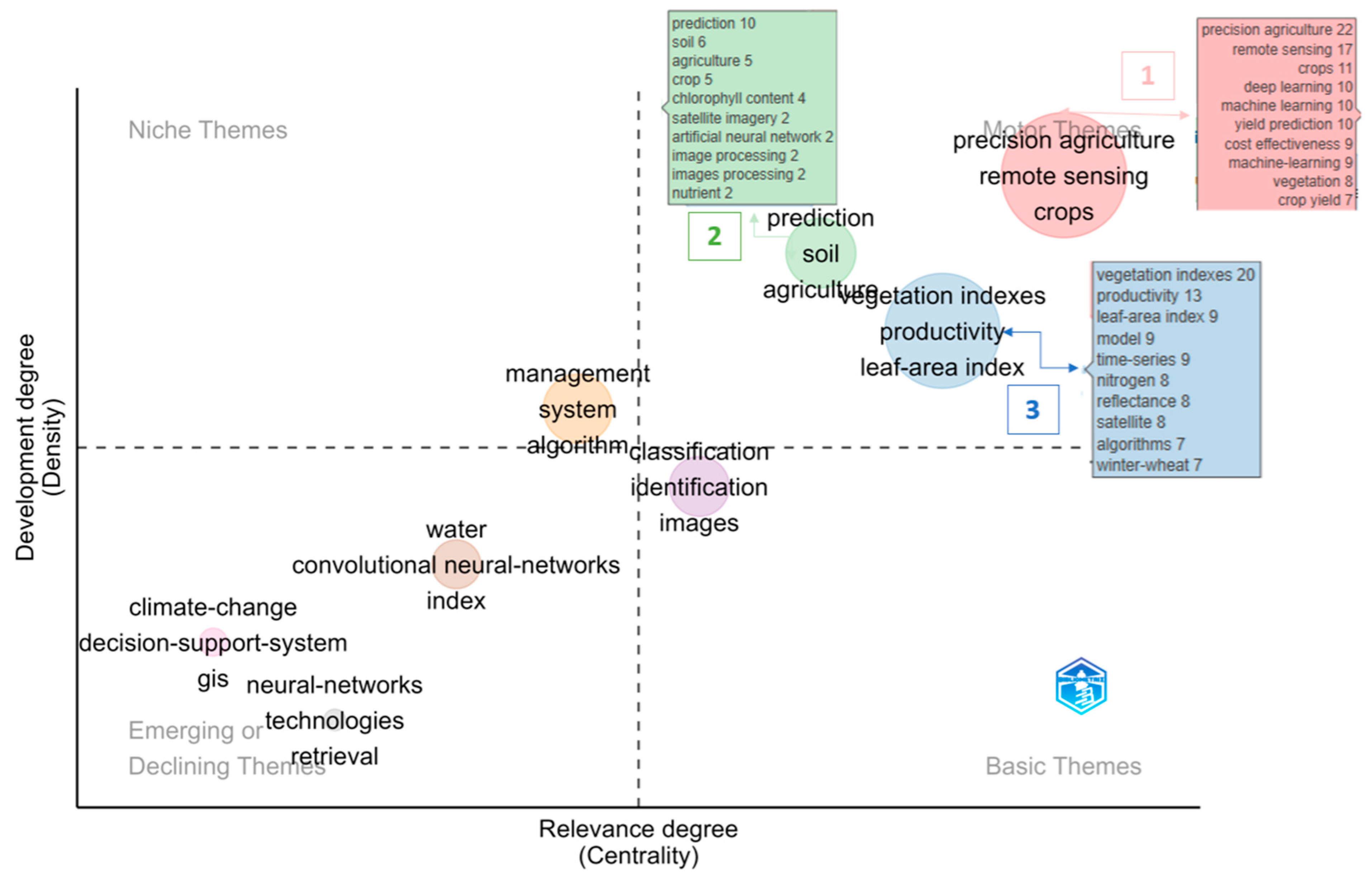

3.5. Trending Topics

The thematic map shown in

Figure 9 provides a structural overview of the main research trends in the application of optical sensors and deep learning in smart agriculture. The visualization categorizes terms into four quadrants based on their centrality (relevance within the field) and density (level of internal development), revealing key conceptual clusters that guide the direction and maturity of the research [

2,

21,

45,

46]. This thematic analysis is particularly significant as it demonstrates the quadratic polynomial growth in machine learning publications for sustainable agriculture, with notable increases of up to 91% per year, indicating strong market confidence and increasing economic returns from technology investments [

20].

Three major clusters stand out in this analysis, each representing a distinct thematic orientation. The first cluster highlights core technologies like precision agriculture and remote sensing, acting as central pillars in smart farming. The second cluster focuses on soil and crop prediction, emphasizing data-driven decision-making tools. The third cluster contains foundational concepts such as vegetation indexes and productivity metrics, essential for evaluating agricultural performance and outcomes These clusters should not be viewed as separate or opposing research lines but as interconnected components within the precision-agriculture pipeline. The ‘precision agriculture and remote sensing’ cluster provides the sensing and spatial-information foundation; the ‘prediction and soil analysis’ cluster functions as the modeling and decision-support layer that converts sensor data into actionable management recommendations; and the ‘vegetation indexes and productivity’ cluster serves as a measurement layer linking spectral information to yield, biomass, and input-use patterns. Together, these clusters describe how sensing, modeling, and measurement interact to support economic gains in resource efficiency and productivity, reflecting the systematic evolution of machine learning in sustainable agriculture—from data acquisition to prediction and, ultimately, to the evaluation of productivity and resource efficiency—as advanced technologies such as the Internet of Things, remote sensing, and smart farming continue to mature [

20].

The dominant cluster comprises topics such as precision agriculture, remote sensing, crops, deep learning, and machine learning, underscoring their central and highly developed role in the literature. This theme reflects a well-established and dynamic area where the synergy of remote data acquisition and machine intelligence is driving practical agricultural innovations. The economic significance of this cluster is evidenced by studies showing that UAV sensing systems combined with AI algorithms provide unique advantages including low cost, high spatio-temporal resolutions, flexibility, automation functions, and minimized risk of operation [

27]. Furthermore, autonomous field machinery utilizing multispectral imaging and deep learning algorithms demonstrate lateral navigation errors below 6 cm while reducing pesticide usage by 40% [

44]. It aligns closely with the study’s objective to assess the economic impact of such technologies, as these tools enhance yield prediction, resource allocation, and cost-efficiency in farming systems.

Terms such as ‘water index’ refer to spectral vegetation metrics (e.g., NDWI) used to infer water content and canopy moisture from optical signals. ‘Convolutional neural networks (CNNs)’ denote deep-learning architectures designed for image analysis, commonly applied in plant-disease detection, yield estimation, and biomass mapping. Their appearance in the thematic map reflects the increasing integration of spectral indices with image-based modeling approaches in smart agriculture.

3.5.1. Prediction and Soil Analysis (Green—Motor Theme)

Keywords like prediction, soil, agriculture, chlorophyll content, and satellite imagery define this cluster, which is also central and dense. It emphasizes the predictive capacity of optical sensors and neural network models in monitoring soil health and crop growth. The economic value of this cluster is demonstrated by hyperspectral remote sensing applications achieving R

2 values ranging from 0.44 to 0.70 for soil nutrient prediction using back-propagation neural networks combined with ordinary kriging models [

47]. Additionally, early nutrient deficiency detection in hydroponic systems using ensemble machine learning achieves 99.6% accuracy with detection capabilities as early as three days after stress induction, representing significant economic value through early intervention capabilities [

48]. These technologies are essential for informed decision-making, contributing directly to economic performance by reducing input uncertainty and improving resource use efficiency.

3.5.2. Vegetation Indexes and Productivity (Blue—Basic Theme)

This cluster, located in the lower-right quadrant, includes vegetation indexes, productivity, leaf-area index, and time-series, representing foundational but less specialized themes. These concepts are frequently used to measure biophysical variables in crops, forming the basis for many remote sensing applications. The practical economic implications of this cluster are evidenced by studies showing that vegetation indices derived from satellite imagery can explain up to 72% of observed spatial variation in corn yield, with multi-linear stepwise regression methods achieving coefficient of determination values of 0.81 [

42,

49]. Furthermore, solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence and vegetation indices demonstrate that models using only near-infrared reflectance of vegetation data can explain up to 64% of yield variability, improving to 69% when combined with additional remote sensing data [

49]. Their widespread utility reflects their relevance across multiple agricultural contexts, supporting the integration of big data analytics into farm-level economic evaluations.

Terms such as convolutional neural networks, decision-support systems, GIS, and retrieval appear in the emerging or declining quadrant. Their low centrality and density suggest that while they may currently be peripheral, they hold potential for future development, particularly as AI frameworks mature and integrate further with spatial technologies. The economic potential of these emerging technologies is demonstrated by studies showing that deep learning models, especially convolutional neural networks, achieve exceptional efficacy in disease detection with accuracy rates of 90% in crops such as tomato, potato, and rice [

50]. Additionally, the integration of hyperspectral imaging, drone surveillance, and AI-powered instruments facilitates early illness identification, continuous monitoring, and scalable solutions that optimize disease management while increasing crop output [

50]. Their economic potential remains underexplored and may represent the next frontier in smart agriculture innovation.

Hence, the thematic interpretation of

Figure 9 links the spatial distribution of research clusters to the economic trajectory of smart-agriculture innovation. Central themes reflect areas where both technological maturity and financial viability have been empirically demonstrated, while peripheral themes represent nascent research directions with strong potential to generate future economic impact as these technologies become more accessible and affordable [

15,

20,

31,

44].

For instance, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been used to detect tomato and potato diseases with accuracies above 90%, enabling pesticide-use reductions between 25 and 40% in field trials [

15]. Similarly, decision-support systems integrating optical indices with deep-learning models have demonstrated up to 18% improvements in nitrogen-use efficiency and operational cost reductions of 10–15% in maize [

19]. These emerging applications illustrate the potential economic value embedded within the thematic clusters.

This thematic decomposition confirms the increasing academic interest in applied technologies for agricultural efficiency and economic return. The prominence of prediction, productivity, and remote sensing within central and motor themes highlights their vital role in transforming farming into a data-driven, cost-effective enterprise, as evidenced by the transition from traditional farm practices to highly automated and data-intensive industries where artificial intelligence-based techniques, together with big data analytics, address agricultural production challenges in terms of productivity and sustainability [

35]. This transformation aligns with the broader goals of sustainable development and economic resilience in global food systems, particularly as precision agriculture transitions from site-specific management focus to global sustainability perspectives, connecting field, watershed, national, and worldwide sustainability objectives [

31].

Based on the thematic clustering and keyword co-occurrence results presented above, the following section examines how these technological developments translate into measurable economic impacts across crops, farming systems, and regions.

4. Discussion

This discussion builds directly upon the scientometric findings presented in

Section 3, where co-authorship patterns (

Figure 5), thematic clusters (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9), and citation performance (

Table 2 and

Table 3) collectively outlined the structural and intellectual landscape of the field. The quantitative evidence—such as the 91% annual growth rate and the dominance of “precision agriculture” and “remote sensing” in co-occurrence networks—forms the empirical foundation for the following economic and policy interpretations.

The integration of optical sensors and deep learning technologies in smart agriculture has demonstrated significant potential for transforming agricultural productivity and economic efficiency. The technologies demonstrated significant improvements in disease detection accuracy (95%), yield prediction, and pesticide reduction (40%) [

44]. These improvements are directly linked to farm-level economics. The 40% reduction in pesticide use translates into cost savings for farmers, while the enhanced yield prediction accuracy leads to better resource allocation and reduced input waste, contributing to an improved Return on Investment (ROI) and labor cost savings [

27].

The 95% disease detection precision translates to an estimated 30–40% reduction in crop losses, representing

$150–400 per hectare in saved revenue for specialty crops. The 40% pesticide reduction generates immediate cost savings of

$50–120 per hectare while reducing regulatory compliance costs and enabling premium market access for low-residue products [

27].

By enhancing yield prediction accuracy and reducing pesticide application, these technologies enable farmers to optimize input use and minimize labor costs [

12,

13]. The result is a more efficient operation, reducing overall costs and improving farm profitability. Furthermore, the reduction in pesticide use aligns with environmental goals, making these technologies not only economically beneficial but also ecologically sustainable.

These findings align with recent evidence on the economic and environmental interdependence of agricultural systems, where climate-related shocks and technological adaptability jointly shape productivity and financial stability in global agri-food networks [

51].

However, the transition from experimental applications to widespread commercial deployment faces substantial practical barriers that require systematic analysis and strategic planning. This section examines the multifaceted challenges encountered during implementation, identifies emerging technological trends that will shape the future landscape, and provides strategic insights for key stakeholders navigating this rapidly evolving field. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for realizing the full economic potential of precision agriculture technologies while ensuring equitable access and sustainable development across diverse agricultural contexts.

4.1. Current Practical Challenges

The implementation of optical sensors and deep learning technologies in smart agriculture faces significant practical barriers that constrain widespread adoption and economic viability. The most prominent challenge is the technological heterogeneity across diverse agricultural environments, high implementation costs, technological limitations affecting adaptability to dynamic field conditions, and socio-economic barriers that hinder adoption, particularly among small and medium-scale farmers [

44]. These barriers create a digital divide where advanced technologies remain inaccessible to smaller farming operations and resource-constrained regions.

However, these challenges vary across farm sizes and geographic contexts. Smallholder farmers in developing regions often face higher barriers due to limited access to credit, infrastructure, and digital literacy [

38,

52]. Targeted solutions such as low-cost modular sensor systems, cooperative technology-sharing platforms, and governmental subsidies can enhance accessibility and adoption [

19]. In contrast, commercial farms in developed economies encounter challenges related to data integration and interoperability among advanced technologies. Here, policy frameworks promoting public–private partnerships, research–industry collaboration, and regulatory incentives are essential to achieve large-scale deployment [

15,

38].

Data quality and integration challenges represent critical bottlenecks in system deployment. The segregation of digital techniques and equipment in both rural and urban areas poses significant obstacles to technological efforts aimed at combating hunger, ensuring sustainable agriculture, and fostering innovations aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [

53]. Furthermore, the lack of accuracy validation based on plant responses, particularly in terms of yield, raises concerns about the reliability of digital tools under real field conditions, even affecting conventional leaf tissue analysis methods.

Model transferability limitations emerge as another significant challenge. Transfer learning approaches demonstrate promising outcomes within specific regions but show limited efficacy when transferring models between different geographic areas, attributed to significant seasonal and climate variations [

38]. This geographic specificity requirement increases implementation costs and reduces the scalability of technological solutions across diverse agricultural contexts.

Infrastructure and connectivity constraints further impede deployment, particularly in remote agricultural areas where reliable internet connectivity and power supply remain inconsistent. The need for highly trained operators and technical expertise creates additional barriers, as many agricultural communities lack access to specialized training programs necessary for effective technology utilization [

52].

From an economic perspective, the indicators synthesized in this study are limited by the level of detail available in the primary literature. Many of the applications identified through Bibliometrix and VOSviewer are still at early or pilot stages, with incomplete information on technical readiness level (TRL), deployment scale, and full cost structures. In addition, reported performance values such as “40% pesticide reduction” or “navigation error below 6 cm” are context-dependent and may not hold for other crops, regions, or farm sizes. For this reason, our analysis focuses on the direction and potential magnitude of economic impacts—such as input savings, risk reduction, and efficiency gains—rather than on precise, universal cost–benefit ratios. Future research should integrate detailed techno-economic assessments and explicit TRL evaluations to refine these estimates and to compare sensor costs with the affordability range of small and medium-sized farmers.

4.2. Emerging Future Trends

The trajectory of optical sensor and deep learning integration in agriculture reveals several transformative technological frontiers with varying maturity levels and adoption readiness. Lightweight artificial intelligence models—such as the LI-YOLOv9 architecture proposed by [

36]—demonstrate exceptional detection accuracy (99.6% mAP) while drastically reducing computational load, although scalability and hardware availability remain key constraints. Edge computing, increasingly adopted for real-time, on-site data processing, mitigates latency and connectivity limitations but requires robust local infrastructure and energy systems [

44]. Hybrid quantum algorithms, currently in their experimental phase, show promising capacity to process massive remote-sensing datasets through quantum-enhanced learning architectures [

54]. Likewise, blockchain applications are emerging for supply-chain transparency and nutrient traceability but continue to face interoperability and regulatory challenges that hinder large-scale deployment [

55]. Addressing these barriers through coordinated policy, investment, and research initiatives will be essential for achieving the full economic and sustainability potential of these technologies.

Multi-energy complementary systems integrating solar, wind, and hydropower sources are emerging as sustainable solutions to power agricultural technologies in remote locations [

44]. These systems promise to reduce long-term operational costs while enhancing the environmental sustainability of precision agriculture implementations.

The development of lightweight, resource-efficient AI models specifically designed for agricultural applications represents a significant trend. The LI-YOLOv9 model exemplifies this direction, achieving exceptional detection capabilities with approximately 9 million parameters compared to 60 million in the original YOLOV9, making it ideal for resource-efficient onboard intelligence [

36]. This miniaturization trend will democratize access to advanced AI capabilities across diverse agricultural contexts.

Hybrid classical-quantum machine learning approaches show promise for processing the exponentially increasing volume and complexity of agricultural data. These systems exploit quantum superposition and entanglement to handle data volumes that challenge classical computing methods, potentially revolutionizing satellite data processing capabilities [

54].

The integration of blockchain technology is emerging as a tool to enhance transparency and traceability in nutrient management, promoting compliance with environmental standards and sustainable practices while creating new economic value streams through verified sustainable agriculture certifications [

55].

4.3. Strategic Insights for Stakeholders

For Technology Developers and Researchers: The development of cost-effective, modular solutions that can be scaled according to farm size and economic capacity represents a critical strategic priority. Focusing on open-source platforms and standardized interfaces will reduce implementation barriers and accelerate adoption rates. The successful deployment of ensemble machine learning techniques, such as the XGB classifier achieving 99.6% accuracy with computational times of 18.07 s [

48], demonstrates the importance of optimizing algorithms for practical deployment scenarios.

Investment in automated machine learning (AutoML) approaches offers significant potential for democratizing access to advanced analytics. AutoML systems can automate the machine learning workflow, including automatic training and optimization of multiple models within user-specified timeframes, making sophisticated analysis accessible to users without extensive technical expertise [

56].

For Policy Makers and Government Agencies: Public policy should lower adoption barriers and align incentives with measurable economic outcomes. First, targeted cost-sharing and smart-subsidy schemes can reduce up-front investment for smallholders—typically 30–40% of sensor and platform costs—an approach shown to accelerate adoption while preserving market efficiency [

57]. Second, digital inclusion programs such as farmer training, extension support, and open technical toolkits are essential to close capability gaps in data literacy and technology use, especially in resource-constrained regions [

58].

Third, investments in rural connectivity and edge-ready infrastructure—stable power, local compute capacity, and communication networks—are necessary to fully realize the benefits of real-time sensing and machine learning [

59]. Fourth, governments should promote interoperability standards (APIs, open data schemas, model documentation) to reduce integration costs and ensure compatibility across multi-vendor ecosystems [

60]. Finally, policy support is needed for region-specific calibration datasets and transfer-learning frameworks, which reduce retraining costs and improve model accuracy across heterogeneous agricultural environments [

61,

62]. Together, these measures enhance the economic viability of precision agriculture by accelerating diffusion, increasing ROI at the farm level, and ensuring that the benefits of digital agriculture are widely distributed [

59].

Government support for collaborative research initiatives between academic institutions, technology companies, and farming communities will be essential for developing location-specific solutions that address regional agricultural challenges while maintaining economic viability.

For Agricultural Producers and Industry Stakeholders: A phased implementation approach, beginning with high-impact, low-complexity applications, offers the most practical pathway for technology adoption. The successful deployment of RGB sensor-based yield prediction systems, which achieve R

2 values of 0.84 [

53], demonstrates that cost-effective solutions can deliver significant economic benefits without requiring extensive technological infrastructure.

Strategic partnerships between large agricultural enterprises and technology providers can facilitate knowledge transfer and reduce implementation risks for smaller operations. The development of technology-sharing cooperatives and leasing models can make advanced systems accessible to resource-constrained producers while distributing economic benefits more equitably.

Beyond reporting technological precision, the study now quantifies the economic implications of these indicators. A 40% reduction in pesticide use corresponds to direct savings of approximately USD 90–120 per hectare, depending on input prices, while a 5–10% improvement in yield prediction accuracy reduces input waste and enhances ROI by up to 8% annually [

15,

25,

41]. Likewise, automation-enabled labor substitution—such as the deployment of UAV-based spraying systems—reduces manual workload by nearly 45%, improving operational efficiency and profit margins for medium- and large-scale farms. These findings demonstrate that technical advancements in smart agriculture yield tangible economic returns, supporting the transition toward cost-effective and sustainable farming systems [

15,

17,

41].

In practical terms, policymakers should consider implementing targeted subsidy programs for smallholders adopting optical-sensor-based systems, modeled after cost-sharing mechanisms used in sustainable farming initiatives, covering up to 30–40% of hardware acquisition costs [

15,

53]. Financial institutions could develop precision-agriculture credit lines with reduced interest rates or loan guarantees to offset high initial investment risks. For technology developers, improving model portability requires designing adaptive learning frameworks capable of regional fine-tuning through transfer learning, as demonstrated by [

38]. Open-source calibration datasets and standardized APIs are recommended to reduce localization costs and accelerate adoption. These measures would bridge the economic gap between innovation and implementation, ensuring that both smallholder and commercial farmers benefit equitably from smart agriculture technologies [

15,

20,

38,

53].

Policy recommendations may differ across development contexts. In developed countries with large-scale farms, priorities include data standardization, interoperability frameworks, cybersecurity regulation, and public support for high-risk next-generation innovations. In contrast, developing countries and smallholder systems benefit most from investments in digital infrastructure, low-cost sensing technologies, capacity-building programs, and targeted financial instruments such as micro-credit or subsidized equipment leasing. Tailoring policy strategies to these structural realities increases the likelihood of adoption and maximizes economic impact.

Future Strategic Directions: The convergence of multiple technological trends suggests that future agricultural systems will integrate optical sensors, AI analytics, IoT connectivity, and autonomous operations into comprehensive precision agriculture platforms. The economic success of these integrated systems will depend on their ability to demonstrate clear return on investment while remaining accessible to diverse agricultural contexts.

The transition toward sustainable precision agriculture and environment (SPAE) management systems represents a fundamental shift from site-specific management to global sustainability perspectives [

31]. This transformation requires coordinated efforts across technology development, policy formulation, and industry adoption to realize the full economic potential of optical sensor and deep learning integration in smart agriculture. Success in this evolving landscape will require stakeholders to balance technological advancement with practical implementation considerations, ensuring that economic benefits are distributed equitably while advancing global food security and environmental sustainability objectives.

5. Conclusions

This study employs a comprehensive scientometric approach utilizing Bibliometrix, VOSviewer, and Voyant tools to systematically address the research questions regarding the economic impact of optical sensors and deep learning technologies in smart agriculture. The multifaceted analysis provides valuable insights into the evolving research landscape, economic implications, and strategic directions for stakeholders across the agricultural innovation ecosystem.

The temporal analysis reveals remarkable growth in scientific interest, with an annual growth rate of 66.48% between 2017 and 2025, culminating in nearly 60 publications by June 2025; this issue was addressed by answering RQ1. This growth aligns with quadratic polynomial increases of up to 91% per year in machine learning publications for sustainable agriculture [

20], demonstrating the field’s transition from experimental applications to economically viable innovations. The analysis identifies leading researchers, with Xiukang Wang (9212 global citations) and Shaowen Wang (5974 citations) representing the intellectual foundation alongside Jing Li, John P. Fulton, and Shihua Li; this issue was addressed by answering RQ2.

Three dominant thematic areas emerge: precision agriculture and remote sensing applications, prediction and soil analysis systems, and vegetation indices and productivity metrics; this issue was addressed by answering RQ3. The co-occurrence network analysis identifies corresponding clusters with precision agriculture and remote sensing as conceptual anchors, demonstrating economic significance through UAV sensing systems providing low cost, high spatio-temporal resolutions, and automation functions [

27]; this issue was addressed by answering RQ4. Emerging themes include convolutional neural networks and decision-support systems, showing potential for future development with deep learning models achieving 90% accuracy in disease detection [

50]; this issue was addressed by answering RQ5.

The economic impact analysis demonstrates substantial benefits: mobile robotic systems achieve 95% precision in disease detection while reducing pesticide use by 40% [

41], autonomous machinery demonstrates lateral navigation errors below 6 cm with 40% pesticide reductions [

44], and the LI-YOLOv9 model achieves 99.60% mean average precision for rice detection [

36]; this issue was addressed by answering RQ6. Factors influencing successful adoption include technological accessibility, implementation costs, and model transferability, though challenges persist, including technological heterogeneity and adoption barriers in developing regions [

44]; this issue was addressed by answering RQ7. It is important to note that these performance indicators are reported for specific experimental or field conditions in the underlying studies, which differ in crop type, disease pressure, management practices, and spatial scale. As such, they should be interpreted as illustrative case-based benchmarks rather than as average effects that can be directly generalized to all farming contexts.

This study acknowledges several important limitations. First, the analysis relies primarily on indexed literature from Scopus and Web of Science databases, potentially overlooking gray literature, industry reports, and regional publications that have not achieved widespread citation. Second, the focus on quantitative bibliometric measures may not fully capture qualitative aspects of economic impact, such as farmer satisfaction, adoption barriers, or contextual implementation challenges. Third, the relatively recent emergence of this research field (2017–2025) may limit the comprehensiveness of long-term economic trend analysis. Additionally, the study’s emphasis on English-language publications may introduce geographic and linguistic bias, potentially underrepresenting contributions from non-English speaking research communities. Finally, the analysis may be affected by ‘fast-forward bias,’ wherein recently published high-impact studies have not yet accumulated citations, causing citation-based indicators to disproportionately reflect earlier, well-established work rather than the latest breakthroughs.

Several promising avenues for future investigation emerge from this analysis. First, longitudinal studies tracking the actual economic performance of implemented optical sensor and deep learning systems across diverse agricultural contexts would provide valuable empirical validation of predicted benefits. Second, comparative analyses of technology adoption patterns across different economic development levels and farm sizes could inform targeted policy interventions. Third, interdisciplinary research incorporating qualitative methodologies, such as farmer interviews and case studies, would enrich understanding of implementation dynamics and adoption barriers.

Future research should also explore the integration of emerging technologies, including edge computing, blockchain verification systems, and quantum-enhanced machine learning, to assess their potential economic implications. Additionally, investigations into regulatory frameworks, standardization protocols, and international cooperation mechanisms could facilitate broader technology adoption and knowledge transfer across agricultural systems worldwide.

This analysis provides valuable insights for researchers identifying collaboration opportunities, policymakers addressing digital divides, technology developers understanding market requirements, agricultural producers evaluating implementation viability, and international organizations supporting precision agriculture initiatives. The study establishes that optical sensors and deep learning have evolved to demonstrate measurable economic impact, with future success depending on balancing technological sophistication with practical accessibility to advance both agricultural productivity and global food security objectives.