Understanding Smart Governance of Sustainable Cities: A Review and Multidimensional Framework

Abstract

Highlights

- Smart governance is a critical driver of sustainable urban development, enhancing operational efficiency, service delivery, and participatory decision-making.

- The effectiveness of smart governance is shaped by key enablers and barriers, including digital infrastructure, data governance, citizen participation, and institutional capacity.

- A multidimensional framework that integrates governance, technology, and sustainability provides a comprehensive lens for understanding and guiding urban transformation.

- Policymakers must prioritize digital inclusion, robust data governance, and institutional innovation to build inclusive, secure, and resilient smart cities.

- Strategically aligning smart governance initiatives with the sustainable development goals (SDG)—particularly SDG 11—can support the creation of equitable and sustainable urban futures.

Abstract

1. Introduction and Background

2. Literature Review

2.1. Dimensions and Challenges of Smart Governance

2.2. Sustainable Development Goals and Smart Governance

| Study | Definition | Domain |

|---|---|---|

| Aguilera et al. [38] | A model exploring how corporate governance drives the environmental sustainability initiatives, with a focus on influencing ownership, boards of directors, CEOs, top management teams, and employees in shaping a company’s environmental outcomes. | Corporate governance and environmental sustainability |

| Ahvenniemi et al. [39] | A comparison of sustainable and smart cities through an evaluation of 16 city assessment frameworks, highlighting the stronger focus on technology in smart cities and recommending the inclusion of sustainability considerations in smart city models. | Urban sustainability and smart city frameworks |

| Akmentina [40] | An exploration of public engagement strategies in urban planning across 12 Baltic cities, shedding light on the enhancement of citizen involvement through e-participation and proposing blended and iterative participatory approaches for effective urban planning. | Urban planning and e-participation |

| Allam et al. [56] | An examination of emerging trends in smart urban governance using bibliometric analysis, focusing on how smart technologies such as IoT, e-governance, and data analytics contribute to urban governance, while highlighting the importance of citizen participation and inclusivity. | Smart urban governance and ICT |

| Al-Nasrawi et al. [57] | Posits intelligence as an active process for positive change in the context of cities, leveraging technologies to facilitate innovative solutions aimed at optimizing urbanism in the broad context of sustainable development goals. | Smart sustainable cities |

| Alonso [58] | An assessment of the role of e-participation in local governance in a European city, questioning whether new information and communication technologies effectively increase civic involvement, and examining the challenges faced in achieving genuine democratic engagement. | Local governance and e-democracy |

| Angelidou et al. [59] | An investigation into how smart city applications can enhance sustainable urban development, through an examination of open-source and proprietary smart city tools, identifying gaps and opportunities for integrating smart solutions to achieve environmental sustainability goals. | Smart cities and sustainable urban development |

| Baud et al. [60] | An interdisciplinary approach and tool for analyzing urban development decision-making and decision outcomes by providing insights into how configurations of governance of urban systems unfold in the context of sustainability transitions through the incorporation of discourses, actor networks, knowledge, and materiality. | Urban governance and sustainability transitions |

| Benites and Simoes [41] | An analytical framework including a smart city services sustainability taxonomy that will facilitate the application of ICTs in smart cities in ways that convey an economic development perspective, together with other aspects of sustainability, such as environmental, social, institutional, and cultural. | Smart city services and urban sustainable development |

| Bibri & Krogstie [42] | To develop a vision for smart sustainable cities in the future: backcasting of sustainable city principles and big data technologies to overcome the embeddedness of sustainable and smart city frameworks and improving their overall sustainability. | Smart sustainable cities and big data technologies |

| Biermann et al. [15] | Substantive policy findings from the Earth System Governance Project pointing to the necessity for radical reforms at the structural level in the governance of the Earth’s systems, therefore urging for stronger institutions, improved international treaties, and better management of the conflicts between various sustainability policies. | Global governance and sustainability transformation |

| Bowen et al. [19] | A review of the prospects for governance problems in the process of implementing the SDGs, understanding the potential problems such as collective action, dilemmas of trade-offs, and accountability that may hinder sustainable development across various sectors, and proposing an idea of how to overcome these difficulties. | Sustainable development goals and governance challenges |

| Castelnovo et al. [43] | Supporting a detailed methodology for evaluating aspects of smart city governance on citizens’ involvement, policy reporting, and the challenges of co-creation and co-delivery of public services for social value creation. | Smart city governance and policy evaluation |

| Clune & Zehnder, [33] | Three Pillars of Sustainability model, showing the sustainability solutions that work due to a coalition of technology, laws, and governance, with economics in concert generating laws toward furtherance of technological and economic development. | Sustainability solutions and governance |

| Colding et al. [61] | A critique questioning whether the smart city model is sustainable in real-life situations, as it may be subject to the law of diminishing returns on sustainability due to the growth in energy consumption and dependency upon technology. | Smart cities and sustainability critique |

| Connor [62] | The “Four Spheres” model focuses on the interdependence among economic, social, environmental, and political spheres toward making any solution sustainable and argues that governance plays a huge role in regulating the interactions among these spheres. | Sustainability and governance frameworks |

| Da Cruz et al. [63] | An exploration of new urban governance themes, emphasizing the need for empirical research on governance strategies for urban challenges, and calling for more comparative and systematic data to inform governance practices. | Urban governance and policy research |

| Das [64] | Interdependence of the four dimensions of digital transformation, IT infrastructure, and service delivery, as well as governance, is analyzed, but the authors write that these must work together to turn a city into an intelligent, sustainable entity. | Digital transformation and smart sustainable cities |

| Estevez & Janowski [65] | The conceptual framework EGOV4SD (electronic governance for sustainable development) centered around the usage of ICT in the support of SDGs by enhancing internal government operations, service delivery, and citizen participation. | Electronic governance and sustainable development |

| Ferreira & Ritta Coelho [66] | The research study of e-participation in smart cities discovered important findings at the motivational, technological, institutional, and cultural levels affecting citizens’ engagement in participative processes. | E-participation and citizen engagement |

| Fu & Zhang [67] | A bibliometric analysis of the evolution of urban sustainability concepts over 35 years, exploring how different city models such as smart cities, eco-cities, and sustainable cities have developed and intersected over time. | Urban sustainability concepts & evolution |

| Grossi & Welinder [68] | A conceptual model that looks at smart cities using public governance perspectives and explaining how digital governance, collaborative governance, and network governance can assist in attaining SDGs in the social, environmental, and economic context. | Smart cities and public governance paradigms |

| Haarstad & Wathne [69] | A study on the relationship linking smart city projects with urban energy sustainability, investigating how smart city initiatives across European cities catalyze urban energy sustainability and the potential of cross-sectoral integration for sustainability. | Smart cities and urban energy sustainability |

| Haarstad [70] | Mapping the position of audience within the frameworks of the trace: a critical consideration of how sustainability is embedded into the “smart city” discussions through the case of Stavanger, Norway, in the context of smart city initiatives, innovation, technology, and economic entrepreneurialism. | Smart cities and sustainability discourse |

| He et al. [71] | A review of the legal governance structures in the smart cities of China, identifying the challenges such as data security, public data sharing, and the necessity of improved legal frameworks to guide smart city development in a digital economy. | Legal governance and smart city development |

| He et al. [72] | An exploration of e-participation’s role in promoting environmental sustainability in Chinese cities, highlighting the ways ICTs can enable public participation in decision-making and raise awareness of environmental issues. | E-participation and environmental sustainability |

| Herdiyanti et al. [73] | A model for evaluating smart governance performance within Indonesia’s smart city program, presenting indicators for assessing how smart governance supports urban digitization and effective service delivery. | Smart governance and performance evaluation |

| Huovila et al. [74] | A comparison of standardized indicators employed in smart sustainable cities, providing insights into how different indicator frameworks can guide decision-making, monitoring, and achieving SDGs. | Smart sustainable cities and indicator frameworks |

| Ibrahim et al. [75] | A roadmap for transforming cities into smart sustainable cities (SSCs), introducing the concept of readiness for change and a logic model that captures the transformation journey, guiding city planners and stakeholders in SSC development. | Smart sustainable cities and urban transformation |

| Jiang, 2021 [76] | An argument for the need for smart urban governance that emphasizes sociotechnical approaches, advocating for a shift away from technocratic, corporate-led smart governance towards more context-based and inclusive urban governance strategies. | Smart urban governance and sociotechnical approaches |

| Kato & Takizawa [77] | An examination of urban transformation in old New Towns in the Osaka Metropolitan Area, using the XGBoost algorithm to analyze the correlation between population decline and transformation into healthcare facilities. | Urban transformation and population decline |

| Lange et al. [78] | Examining ways in which governance can be understood in relation to politics, polity, and policy to give it a multi-faceted perspective. | Sustainability governance |

| Lim & Yigitcanlar [10] | Examines participatory governance in smart cities, analyzing how e-platforms contribute to smart city realization, emphasizing e-decision-making, e-consultation, and e-information. | Smart city governance |

| Martin et al. [79] | Intends to improve the overall performance and management of the urban world by proposing a fresh concept of smart sustainability as a technology-environmental initiative based on entrepreneurial approaches to the operation of urban governments. | Urban sustainability |

| Meuleman & Niestroy [80] | Proposes “common but differentiated governance” to establish the framework for fulfilling SDGs through a metagovernance approach, which brings different styles of governance together in a manner most suitable for certain situations. | Sustainable development |

| Mooij [29] | An exploration of the concept of SMART governance in Andhra Pradesh, India, examining the state’s reform process and analyzing its governance strategies, including efforts to separate politics from policy implementation, centralize policymaking, enhance performance, and improve transparency and accountability. The study discusses the challenges and contradictions in the state’s attempts to adopt SMART governance principles. | SMART governance and policy implementation in Andhra Pradesh |

| Mutiara et al. [3] | Evaluates the state of e-governance in Indonesian cities, focusing on transparent governance and open data as indicators used for initiating smart governance and smart cities. | Smart city governance |

| Ochara [81] | Argues on the desperate need for grassroots participation towards sustainable e-governance in Africa and underlines the role of community involvement in e-government. | E-governance sustainability |

| Palacin et al. [82] | Proposes six e-participation sub-dimensions within the context of the United Nations E-Participation Index, where the various digital engagements by people and e-governments help in attaining sustainable development in line with the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. | E-participation and sustainable development |

| Paskaleva, 2009 [83] | Explores how e-governance can assist cities in decision-making and engagement with citizens, emphasizing the role of collaborative digital environments to foster smart city governance through integrated e-services and knowledge networks. | Smart city governance |

| Patterson et al. [84] | Covers the issues of governance and politics of change for sustainability, pertinent social technologies, social-ecological systems, sustainability transitions, and transformative adaptation. | Sustainability governance |

| Rahman et al. [85] | Discusses the transition in concept from e-governance to smart governance, and then presents how digital governance, smart city, innovation, and improved quality of public service contributed to the UAE’s change. | Digital governance |

| Rochet & Belemlih [86] | Considers smart cities as complex, citizen-centric systems that evolve through bottom-up dynamics, emphasizing the role of social emergence and integration for sustainable smart city governance. | Smart city governance |

| Tewari & Datt [87] | The way towards Fog of Things-grounded architecture in governance, changing e-governance into smart governance. | E-governance and smart governance |

| Toli & Murtagh [88] | Reviews the present definitions of smart cities and discusses their perspectives on sustainability; identifies the shared features of the smart city frameworks that incorporate environmental, economic, and social sustainability; and offers a new definition for smart cities. | Smart city sustainability |

| Turnheim et al. [89] | Suggests a conceptual approach for combining systems modeling, socio-technical transition approaches and learning from initiatives when managing the difficulties related to sustainability transition pathways. | Sustainability transitions |

| Yahia et al. [90] | Discusses smart cities from the governance perspective and more specifically regarding sustainable collaborative networks and provides structures for the enhancement in performance and participation of the stakeholders in smart governance. | Collaborative governance |

| Yigitcanlar & Kamruzzaman [32] | Argues that the correlation between city smartness and sustainability is not a direct one, noting the need for more efficient integration of smart city initiatives with sustainability objectives. Assesses the impact of smart city policy on urban sustainability using carbon dioxide emissions data from 15 cities within the UK. | Urban sustainability |

| Zachary & Jared [91] | Characterizes e-governance levels and the use of ICT in enhancing participation, transparency, and accountability, emphasizing how e-governance improves service delivery, access to information, and citizen engagement. | E-governance |

| Zhu et al. [92] | Develops a typology for smart cities in China, categorizing them into five types: knowledge-technocratic, holistic, green, equipment-technocratic, and emerging smart cities, based on characteristics such as input, throughput, and output of smart city practices. | Smart city typology |

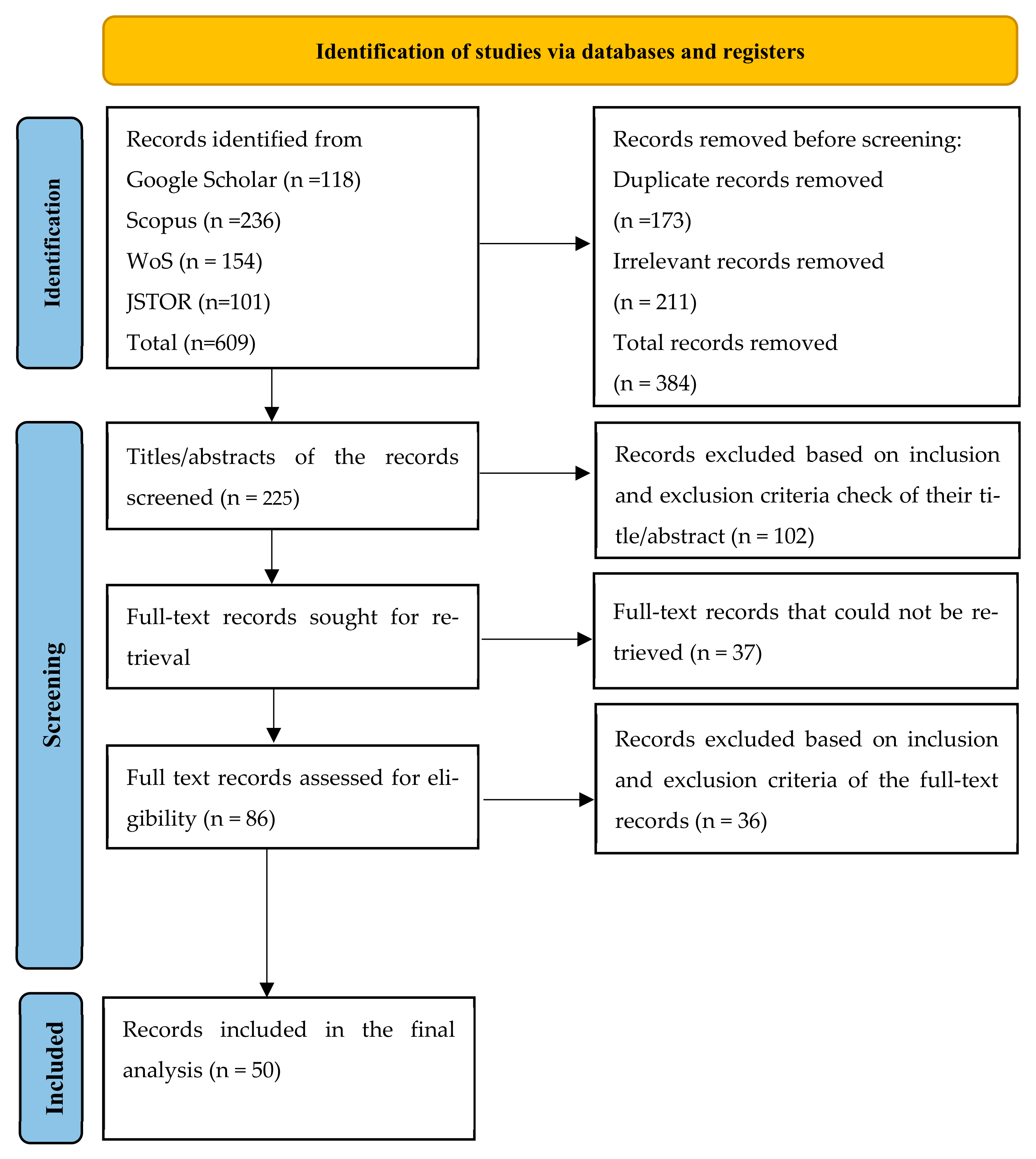

3. Research Design

Article Selection Process

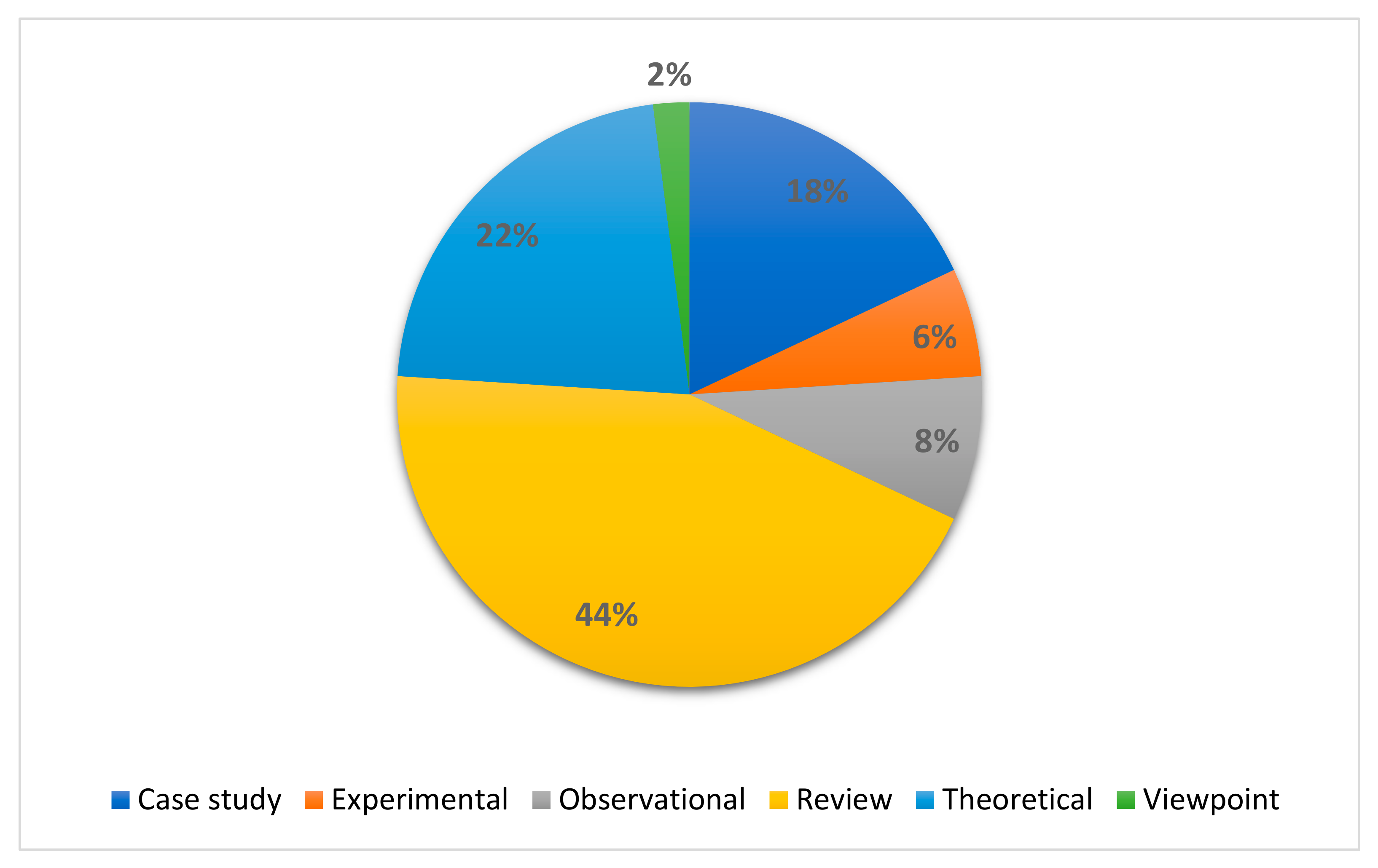

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. General Observations

- Smart governance frameworks in practice: This theme focuses on the integration of advanced technologies such as AI, IoT, and blockchain into governance models and includes 14 papers.

- Governance challenges and barriers: This theme addresses issues such as the digital divide, access for marginalized populations, and privacy concerns in technology-centered models, encompassing 12 papers.

- Case studies of successful smart governance: This theme covers instances where grassroots participation has led to positive governance outcomes (includes 13 papers).

- Technocentric vs. human-centric governance approaches: This theme compares technology-driven methods with those emphasizing grassroots participation. It includes 11 papers.

- Towards a multidimensional framework: This theme integrates insights from all 50 papers, aiming to create a comprehensive approach that balances technological, social, and governance aspects.

4.2. Smart Governance Frameworks in Practice

4.3. Challenges and Barriers to Smart Governance

4.4. Smart Governance Best Practices

4.5. Technocentric and Human-Centric Governance Models

4.6. Towards a Multidimensional Framework

5. Findings and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study | Title | Journal | Aim | Challenge | Critique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguilera et al. [38] | “The Corporate Governance of Environmental Sustainability: A Review and Proposal for More Integrated Research” | Journal of Management | Analyze how corporate governance influences environmental sustainability. | Lack of consistent and comparable metrics for measuring corporate sustainability efforts. | The paper offers a broad review but lacks actionable strategies for corporations to integrate sustainability effectively. |

| Ahvenniemi et al. [39] | “What Are the Differences Between Sustainable and Smart Cities?” | Cities | Compare sustainable and smart city paradigms. | Lack of standardized frameworks for assessing smart cities’ sustainability. | The study lacks practical case studies, assumes technology neutrality, overlooks integration complexities, provides limited focus on social sustainability, and treats paradigms as static rather than evolving. |

| Akmenti [40] | “E-Participation and Engagement in Urban Planning: Experiences from the Baltic Cities” | Urban Research & Practice | Examine how e-participation functions in Baltic cities’ urban planning procedures. | Engaging citizens in meaningful participation remains a significant barrier. | The study highlights successful cases but fails to address the lack of digital infrastructure in less developed regions. |

| Allam et al. [56] | “Emerging Trends and Knowledge Structures of Smart Urban Governance” | Sustainability | Discuss the technological advancements in smart governance for urban sustainability. | Technological adoption barriers and resistance from legacy systems. | Fails to adequately examine how citizens’ involvement and local governments contribute to the adoption of new technologies. |

| Al-Nasrawi et al. [57] | “Smartness of Smart Sustainable Cities: a Multidimensional Dynamic Process Fostering Sustainable Development” | Fifth International Conference on Smart Cities, Systems, Devices | Develop a multidimensional model to assess the smartness of sustainable cities. | Defining and standardizing “smartness” as a measurable concept remains a challenge. | The paper proposes a novel model but lacks real-world case studies to validate its effectiveness. |

| Alonso [58] | “E-Participation and Local Governance: A Case Study” | Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management | Examine the impact of digital tools on citizen participation in local governance. | Low engagement of citizens despite digital tools. | Emphasizes the role of socio-economic factors but underplays the technological limitations of e-participation tools. |

| Angelidou et al. [59] | “Enhancing Sustainable Urban Development Through Smart City Applications” | Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management | Explore how smart city applications contribute to sustainable urban development. | Implementing smart city technologies requires large-scale investment and skilled labor. | Focuses primarily on technological solutions but does not sufficiently address socio-economic issues that may hinder implementation. |

| Baud et al. [60] | “The Urban Governance Configuration: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Complexity and Enhancing Transitions to Greater Sustainability in Cities” | Geography Compass | Propose a framework for conceptual analysis and comparison of urban governance arrangements and their dynamics in relation to sustainability transitions. | Various governance configurations within and between cities; how complex decision-making is combined in a specific time and space to produce decisions and outcomes based on a variety of knowledge; and how urban governance could change to more sustainable, inclusive forms of urban development. | In a complex world, this framework makes it possible to integrate key elements (discourses, actor networks, knowledge, and material processes) that influence urban development decisions and results in their social, economic, and environmental domains. |

| Benites and Simoes [41] | “Assessing Urban Sustainable Development Strategy: An Application of Smart City Sustainability Taxonomy” | Ecological Indicators | Develop a taxonomy for assessing smart city sustainability using ICT tools. | Inconsistent data quality and collection methods across cities. | The proposed taxonomy lacks flexibility for adaptation to diverse city structures and governance models. |

| Bibri and Krogstie [42] | “Generating a Vision for Smart Sustainable Cities of the Future: A Scholarly Backcasting Approach” | European Journal of Futures Research | Create a backcasting model for smart, sustainable cities of the future. | Integrating long-term goals with immediate urban policy demands presents challenges. | The backcasting approach is innovative, but practical examples are limited, raising concerns about the scalability of the proposed vision. |

| Biermann et al. [15] | “Transforming Governance and Institutions for Global Sustainability: Key Insights from the Earth System Governance” | Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability | Examine governance challenges in addressing global environmental change. | Overlapping international and national governance systems. | The paper offers innovative frameworks but lacks practical solutions for integrating multiple governance systems. |

| Bowen et al. [19] | “Implementing the ‘Sustainable Development Goals’: Towards Addressing Three Key Governance Challenges—Collective Action, Trade-Offs, and Accountability” | Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability | Identify three significant governance issues that are essential to achieving the SDGs: (i) fostering collective action by establishing inclusive decision-making forums for stakeholders from various sectors and scales; (ii) focusing on equity, justice, and fairness while making difficult trade-offs; and (iii) making sure that there are systems in place to hold societal actors accountable for their actions, investments, decisions, and results. | One of the biggest challenges facing sustainability science, civil society, and government is achieving the SDGs, which aim to minimize ecological harm, eliminate inequality, and provide resilient lifestyles. | The significance of the connections among these three governance challenges is emphasized, along with each of these challenges’ potential solutions. |

| Castelnovo et al. [42] | Smart Cities Governance: The Need for a Holistic Approach to Assessing Urban Participatory Policy Making | Social Science Computer Review | Investigate the need for flexible governance models in smart cities. | Balancing technological progress with citizen engagement. | While insightful, the paper does not adequately address how smaller cities with fewer resources can implement these models effectively. |

| Clune and Zehnder [33] | The Three Pillars of Sustainability Framework: Approaches for Laws and Governance | Journal of Environmental Protection | Analyze the role of governance in shaping sustainability laws and frameworks. | Resistance from stakeholders to adopt sustainability-focused laws. | The paper critiques existing legal frameworks but fails to propose a unified global approach to sustainability governance. |

| Colding et al. [61] | “The Smart City Model: A New Panacea for Urban Sustainability or Unmanageable Complexity?” | Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science | Explore whether smart cities genuinely lead to sustainability or create unmanageable complexity. | Lack of proper theories to address the complexity of smart city systems. | The paper questions the sustainability of smart cities but does not propose solutions for managing the growing complexity and potential energy costs. |

| Connor [62] | “The “Four Spheres” Framework for Sustainability” | Ecological Complexity | Propose a “Four Spheres” framework integrating economic, social, environmental, and political spheres. | The challenge of balancing economic activity with environmental and social goals. | Provides a thorough conceptual framework but lacks empirical evidence on the effectiveness of applying this framework in real-world governance. |

| Da Cruz et al. [63] | “New Urban Governance: A Review of Current Themes and Future Priorities” | Journal of Urban Affairs | To review contemporary themes and priorities in urban governance, highlighting governance networks and institutional structures. | Challenges include navigating complex and often conflicting urban policies, diverse stakeholder interests, and institutional reforms. | The study emphasizes the need for empirical backing in understanding urban governance while also acknowledging the limitations of purely technocratic approaches. |

| Das [64] | “Exploring the Symbiotic Relationship between Digital Transformation, Infrastructure, Service Delivery, and Governance for Smart Sustainable Cities” | Smart Cities | Discuss the role of technology in transforming urban governance towards sustainability. | Barriers to technology adoption in legacy governance systems. | The paper fails to fully account for socio-political challenges that hinder the adoption of smart technologies in urban governance. |

| Estevez and Janowski [65] | “Electronic Governance for Sustainable Development—Conceptual framework and state of research” | Government Information Quarterly | Explore the role of electronic governance (e-governance) in promoting sustainable development. | Challenges in integrating e-governance solutions across diverse governance frameworks. | The framework is well-defined but requires real-world application to validate its efficacy in diverse urban contexts. |

| Ferreira and Ritta Coelho [66] | “Factors of Engagement in E-Participation in a Smart City” | ICEGOV 2022 Conference | Investigate the -factors that contribute to citizen participation in e-Governance platforms. | Low engagement rates are due to cultural and technological barriers. | The study provides good insights but does not suggest actionable solutions to overcome cultural barriers that hinder e-participation. |

| Fu and Zhang, 2017 [67] | “Trajectory of Urban Sustainability Concepts: A 35-Year Bibliometric Analysis” | Cities | Review the evolution of urban sustainability concepts over 35 years using bibliometric methods. | Many sustainability concepts are abstract and difficult to implement. | The paper provides an excellent historical review but lacks forward-looking perspectives on the future of urban sustainability initiatives. |

| Grossi and Welinder [68] | “Smart Cities at the Intersection of Public Governance Paradigms for Sustainability” | Urban Studies | Investigate how smart city governance intersects with public governance paradigms for sustainability. | Balancing technological innovations with governance models remains a significant challenge. | The paper introduces a novel framework but does not fully explore how this can be practically implemented in lower-income or less technologically advanced cities. |

| Haarstad and Wathne [69] | “Are Smart City Projects Catalyzing Urban Energy Sustainability?” | Energy Policy | Examine the links among smart cities and energy sustainability. | Measuring energy efficiency in smart city initiatives is difficult due to a lack of standardized metrics. | The paper emphasizes the potential of smart city initiatives but highlights that energy savings are not adequately measured or quantified. |

| Haarstad [70] | “Constructing the Sustainable City: Examining the Role of Sustainability in the ‘Smart City’ Discourse” | Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning | Examine how sustainability is framed within smart city initiatives, with a focus on European cities. | The concept of “smart cities” remains vague and is often driven by corporate interests. | The paper offers a critical perspective but could expand on actionable recommendations for policymakers to ensure sustainability plays a central role in smart city agendas. |

| He et al. [71] | “E-Participation for Environmental Sustainability in Transitional Urban China” | Sustainability Science | Analyze how ICT can unlock the full potential of e-governance strategies. | Limited access to ICT infrastructure in developing countries. | While the analysis is comprehensive, the paper does not sufficiently address the long-term sustainability of ICT projects in less developed regions. |

| He et al. [72] | “Legal Governance in the Smart Cities of China: Functions, Problems, and Solutions” | Sustainability | Explore legal governance issues and propose solutions to support China’s smart city governance. | Legal frameworks often lag technological advancements in smart city contexts. | The article provides useful insights but fails to address the broader international implications of China’s governance model. |

| Herdiyanti et al. [73] | “Modelling the Smart Governance Performance to Support Smart City Program in Indonesia” | Procedia Computer Science | Compare seven smart city standards and evaluate their applicability in Indonesian cities. | Customizing global standards to local contexts remains a major challenge. | The study presents valuable comparative insights but lacks practical guidance on localizing smart city standards. |

| Huovila et al. [74] | “Comparative Analysis of Standardized Indicators for Smart Sustainable Cities: What Indicators and Standards to Use and When?” | Cities | Analyze and compare indicators used to assess smart sustainable cities across urban contexts. | Ensuring consistency in data collection across different cities remains difficult. | The paper highlights the need for a flexible framework that allows for adaptation to different urban environments. |

| Ibrahim et al. [75] | “Smart Sustainable Cities Roadmap: Readiness for Transformation towards Urban Sustainability” | Sustainable Cities & Society | Propose a roadmap for city planners and decision-makers for transforming traditional cities into SSCs. | Readiness for change in cities is often underestimated, leading to implementation failures. | The roadmap is useful for guiding city transformations, but the study lacks empirical validation through case studies. |

| Jiang [76] | “Smart urban governance in the ‘smart’ era: Why is it urgently needed?” | Cities | Analyze the characteristics and urgency of smart urban governance, providing a framework for understanding how smart governance can be implemented effectively. | Challenges include integrating technology with urban planning, addressing technocratic governance issues, and achieving citizen engagement. | While the study effectively highlights the importance of context-based smart urban governance, it could benefit from practical examples or case studies for real-world application. |

| Kato and Takizawa [77] | “Urban Transformation and Population Decline in Old New Towns in the Osaka Metropolitan Area” | Cities | To study the nonlinear relationship between population, decline, and urban transformation in old New Towns using XGBoost analysis. | Challenges include addressing the aging population, land use changes, and the effectiveness of urban planning strategies. | While the study provides valuable insights into the transformation process, it could consider more policy-oriented solutions to address the identified issues. |

| Lange et al. [78] | “Governing Towards Sustainability—Conceptualizing Modes of Governance” | Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning | Explore governance models that conceptualize sustainability transitions in urban contexts. | Conflict between short-term political cycles and long-term sustainability goals. | The study offers a comprehensive review but does not provide actionable solutions for overcoming political inertia. |

| Lim and Yigitcanla [10] | “Participatory Governance of Smart Cities: Insights from E-Participation of Putrajaya and Petaling Jaya, Malaysia” | Smart Cities | Examine how citizen participation can improve smart city governance in Penang and Puchong, Malaysia. | Engaging marginalized communities remains a significant barrier. | The article offers valuable insights but fails to address issues of accessibility and inclusivity in citizen participation strategies. |

| Martin et al. [79] | “Smart-Sustainability: A New Urban Fix?” | Sustainable Cities & Society | Explore the potential of smart sustainability as a fix for urban economic, environmental, and social issues. | The smart sustainability concept is often driven by corporate interests, limiting its transformative potential. | The paper critiques the over-reliance on technological solutions and advocates for a more balanced approach to sustainability and governance. |

| Meuleman and Niestroy [80] | “Common But Differentiated Governance: A Metagovernance Approach to Make the SDGs Work” | Sustainability | Develop a metagovernance framework for achieving SDGs in cities. | Achieving consensus among diverse stakeholders is often difficult. | The metagovernance framework is promising but lacks concrete examples of successful implementation in complex urban environments. |

| Mooij [29] | “Smart Governance? Politics in the Policy Process in Andhra Pradesh, India” | Overseas Development Institute | Investigate the role of politics in the implementation of smart governance in Andhra Pradesh. | Lack of transparency and high levels of political interference in governance structures. | The study effectively analyzes political barriers but lacks specific recommendations on how to overcome them. |

| Mutiara et al. [3] | “Smart Governance for Smart City” | IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science | Examine the status of smart governance in Indonesian cities. | A lack of transparency and limited public participation in local governance structures. | The paper provides a strong analysis of e-governance but lacks empirical data on actual improvements in public service delivery. |

| Ochara [81] | “Grassroots Community Participation as a Key to e-Governance Sustainability in Africa” | The African Journal of Information and Communication | Explore how grassroots community participation enhances the sustainability of e-governance initiatives. | Limited technological infrastructure and digital literacy in African communities. | The study emphasizes community participation but underplays the technological challenges faced in rural areas. |

| Palacin et al. [82] | “Reframing E-Participation for Sustainable Development” | ICEGOV | Investigate the role of e-participation in achieving sustainable urban development. | Engaging marginalized communities in e-participation platforms remains difficult. | The paper highlights the potential of e-participation but lacks concrete examples of successful implementation in marginalized communities. |

| Paskaleva [83] | “Enabling the Smart City: The Progress of City E-Governance in Europe” | International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development | Analyze how e-governance can improve decision-making and citizen engagement in European cities. | E-governance adoption varies significantly across different European cities, limiting overall progress. | The paper provides comprehensive insights but lacks detailed case studies on cities with advanced e-governance. |

| Patterson et al. [84] | “Exploring the Governance and Politics of Transformations Towards Sustainability” | Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions | Explore how governance can facilitate transitions toward sustainability, particularly in urban settings. | Aligning political agendas with long-term sustainability goals is challenging. | The study provides a thorough theoretical framework but lacks real-world policy recommendations. |

| Rahman et al. [85] | “From E-Governance to Smart Governance: Policy Lessons for the UAE” | Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance | Provide policy recommendations for transitioning from e-governance to smart governance in the UAE. | Limited integration of technology across different government sectors remains a key challenge. | The paper provides insightful policy suggestions but does not explore potential cultural barriers to adoption. |

| Rochet and Belemlih [86] | “Social Emergence, Cornerstone of Smart City Governance as a Complex Citizen-Centric System” | Handbook of Smart Cities | Explore how social emergence plays a key role in smart city governance models. | Balancing technological advancement with citizen participation remains difficult. | The article presents a well-rounded framework but lacks empirical evidence on the real-world impacts of social emergence on governance. |

| Tewari and Datt [87] | “Towards FoT (Fog-of-Things) enabled Architecture in Governance: Transforming E-Governance to Smart Governance” | International Conference on Intelligent Engineering and Management (ICIEM) | Propose a FoT-based architecture for transforming e-Governance to smart governance. | High latency and security issues in IoT-based e-Governance. | The solution is promising but requires more real-world testing to address scalability and security concerns. |

| Toli and Murtagh [88] | “The Concept of Sustainability in Smart City Definitions” | Frontiers in Built Environment | Review existing smart city definitions, focusing on their sustainability dimensions and propose an updated definition. | The lack of a consistent, universally accepted definition of “smart city” across the literature. | The review is thorough but lacks empirical case studies to test the proposed definition’s effectiveness in practice. |

| Turnheim et al. [89] | “Evaluating Sustainability Transitions Pathways: Bridging Analytical Approaches to Address Governance Challenges” | Global Climate Change | Create an integrated systems model that addresses the complexities of sustainability transitions. | Managing the complexity of multiple systems within environmental and social transitions. | The model is comprehensive but may be too complex to apply in practical policymaking without significant adaptation. |

| Yahia et al. [90] | “Towards Sustainable Collaborative Networks for Smart Cities Co-Governance” | International Journal of Information Management | Explore how collaborative networks of informatics can be leveraged for effective governance in smart cities. | The challenge of integrating diverse informatics systems across multiple governance levels. | The study provides valuable insights but lacks a clear roadmap for the real-world implementation of these collaborative networks. |

| Yigitcanlar and Kamruzzaman [32] | “Does Smart City Policy Lead to Sustainability of Cities?” | Land Use Policy | Investigate the policies that support smart cities and their role in promoting urban sustainability. | Difficulty in translating policy into effective on-the-ground sustainability improvements. | The paper presents a strong policy analysis but lacks examples of successful implementation in varied urban contexts. |

| Zachary and Jared [91] | “Characterizing E-Participation Levels in E-Governance” | International Journal of Scientific Research and Innovative Technology | Analyze the role of ICT in enhancing citizen participation in e-governance and assess e-participation levels. | Balancing the accessibility of ICT with equitable citizen participation. | While the study highlights important factors in e-governance, it doesn’t address how to overcome the digital divide that may limit participation. |

| Zhu et al. [92] | “How Different Can Smart Cities Be? A Typology of Smart Cities in China” | Cities | Examine and classify the diverse characteristics of smart cities in China, using a comprehensive framework. | Addressing the varied nature of smart city development and differences in regional contexts within China. | The study provides an in-depth classification but might benefit from broader comparisons with global smart cities to understand China’s unique positioning. |

| Study | City | Governance Model | Key Technologies | Impact on Sustainability | Citizen Engagement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chia [95] | Singapore | Smart nation initiative | AI, IoT, blockchain | Improved service delivery, enhanced urban mobility, sustainable urban planning | Public engagement via digital platforms |

| Hao et al. [108] | Kenya | Enhancing public participation in governance | ICT, AI | Strengthened public engagement, enhanced decision-making and transparency | Grassroots participation, digital services for marginalized communities |

| Müller [31] | Leuven City | Smart city initiatives | Digital platforms, AI | Enhanced business processes, simplified public services | Active engagement through e-platforms |

| Pieterse [106] | Johannesburg | Urban governance and spatial transformation ambitions | Digital platforms, GIS | Focuses on reducing urban fragmentation and supporting sustainable development | Grassroots-level public participation, local councils (baraza and indaba) |

| Sarv & Soe [100] | Tallinn, Estonia | Unified smart city model | e-government platforms, AI | Increased efficiency in public service delivery | Public participation through e-governance portals |

| Vatsa & Chhaparwal [101] | Estonia | E-government and participatory governance | Digital platforms, blockchain | Transparency in public services, enhanced citizen-government interactions | High levels of digital participation |

| Yigitcanlar & Bulu [27] | Istanbul, Turkey | Knowledge-based urban development | Digital platforms, AI, urban analytics | Increased competitiveness and sustainable economic development | Community involvement through digital platforms |

| Study | City | Governance Model | Key Features | Advantages | Challenges | Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chia [95] | Singapore | Smart nation | AI, IoT, big data analytics | High efficiency, real-time decision-making | Risks citizen disengagement, digital divide | Technocentric |

| Vatsa & Chhaparwa [101] | Estonia | E-government | Blockchain, e-participation platforms | Increased transparency, digital efficiency | Access for marginalized populations | Technocentric |

| Aragón et al. [96] | Barcelona | Decidim (participatory) | E-participation, community-driven policies | High citizen engagement, inclusive decision-making | Slower decision-making, reliance on consultation | Human-centric |

| Corburn et al. [97] | Medellín | City for Life | Community involvement, grassroots participation | Social cohesion, reduction in crime, inclusivity | Resource-intensive, slower response times | Human-centric |

| Ylipulli & Luusua [113] | Helsinki | Citizen-centric smart city | AI-driven services with public feedback mechanisms | Balances technology with public needs | Ensuring equal access to digital platforms | Balanced |

| Huh et al. [121] | Songdo | Technological infrastructure focus | IoT, big data, automated systems | Fully integrated infrastructure, optimized services | Limited citizen participation, corporate-driven | Technocentric |

| Griffiths & Sovacool [122] | Masdar | Sustainable tech-centric governance | IoT, energy-efficient technologies | Environmentally sustainable, energy-efficient | Top-down approach, limited public engagement | Technocentric |

| Putra & van der Knaap [25] | Amsterdam | Smart city framework | IoT, data platforms, urban dashboards | Efficient mobility, smart infrastructure | Integrating citizen feedback with technological systems | Balanced |

| Study | Title | Journal | Framework | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguilera et al. [38] | “The Corporate Governance of Environmental Sustainability: A Review and Proposal for More Integrated Research” | Journal of Management | Governance and policy frameworks | Identifies research gaps in governance roles for sustainability, proposing solutions for comprehensive frameworks and future studies. |

| Ahvenniemi et al. [39] | “What Are the Differences Between Sustainable and Smart Cities?” | Cities | Smart cities and sustainability frameworks | Smart city frameworks emphasize technology, while sustainable frameworks focus more on environmental aspects. Suggests merging both models. |

| Akmentina [40] | “E-Participation and Engagement in Urban Planning: Experiences from the Baltic cities” | Urban Research & Practice | E-participation and citizen-centric governance frameworks | Highlights how ICT tools improve transparency and public engagement but notes challenges in meaningful citizen involvement. |

| Allam et al. [56] | “Emerging Trends and Knowledge Structures of Smart Urban Governance” | Sustainability | Analytical and comparative frameworks | Shows increasing focus on citizen participation and technology adoption in urban governance, identifying future research directions. |

| Al-Nasrawi et al. [57] | “Smartness of Smart Sustainable Cities: a Multidimensional Dynamic Process Fostering Sustainable Development” | Fifth International Conference on Smart Cities, Systems, Devices | Smart cities and sustainability frameworks | Demonstrates the reciprocal relationship between smartness and sustainable development goals. |

| Alonso [58] | “E-Participation and Local Governance: A Case Study” | Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management | E-participation and citizen-centric governance frameworks | Demonstrates both potential and limitations of e-participation; points to political marketing risks outweighing real participation. |

| Angelidou et al. [59] | “Enhancing Sustainable Urban Development through Smart City Applications” | Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management | Smart cities and sustainability frameworks | Identifies fragmentation in smart city approaches and recommends policy improvements to promote sustainable urban growth. |

| Baud et al. [60] | “The Urban Governance Configuration: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Complexity and Enhancing Transitions to Greater Sustainability in Cities” | Geography Compass | Governance and policy frameworks | Offers insights into improving urban governance through more inclusive and sustainable strategies, focusing on knowledge management. |

| Benites & Simoes [41] | “Assessing Urban Sustainable Development Strategy: An Application of Smart City Sustainability Taxonomy” | Ecological Indicators | Analytical and comparative frameworks | Identifies a shift towards economic-focused smart city solutions, recommending broader inclusion of social and environmental indicators. |

| Bibri & Krogstie [42] | “Generating a Vision for Smart Sustainable Cities of the Future: A Scholarly Backcasting Approach” | European Journal of Futures Research | Smart cities and sustainability frameworks | Proposes strategic pathways to combine technology with sustainability, addressing long-term urban challenges and smart city evolution. |

| Biermann et al. [15] | “Transforming Governance and Institutions for Global Sustainability: Key Insights from the Earth System Governance” | Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability | Governance and policy frameworks | Advocates for transformative global governance to address sustainability challenges, emphasizing institutional reform. |

| Bowen et al. [19] | “Implementing the ‘Sustainable Development Goals’: towards addressing three key governance challenges—collective action, trade-offs, and accountability” | Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability | Governance and policy frameworks | Highlights governance challenges in SDG implementation and suggests solutions to overcome institutional barriers. |

| Castelnovo et al. [43] | “Smart Cities Governance: The Need for a Holistic Approach to Assessing Urban Participatory Policy Making” | Social Science Computer Review | Governance and policy frameworks | Promotes citizen engagement and participatory governance as essential for evaluating smart city policies’ impact. |

| Clune & Zehnder [33] | “The Three Pillars of Sustainability Framework: Approaches for Laws and Governance” | Journal of Environmental Protection | Conceptual and development-oriented frameworks | Emphasizes the importance of integrated approaches for successful sustainability efforts across various domains. |

| Colding et al. [61] | “The Smart City Model: A New Panacea for Urban Sustainability or Unmanageable Complexity?” | Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science | Smart cities and sustainability frameworks | Warns about the risks of excessive urban complexity and energy consumption, suggesting thoughtful ICT integration. |

| Connor [62] | “The ‘Four Spheres’ Framework for Sustainability” | Ecological Complexity | Conceptual and development-oriented frameworks | Provides a governance model emphasizing interconnected systems to achieve sustainability through balanced decision-making. |

| Da Cruz et al. [63] | “New Urban Governance: A Review of Current Themes and Future Priorities” | Journal of Urban Affairs | Analytical and comparative frameworks | Identifies governance challenges such as fiscal autonomy, political engagement, and citizen participation. |

| Das [64] | “Exploring the Symbiotic Relationship between Digital Transformation, Infrastructure, Service Delivery, and Governance for Smart Sustainable Cities” | Smart Cities | Conceptual and development-oriented frameworks | Emphasizes the need for synchronized governance and infrastructure to achieve smart and sustainable cities. |

| Estevez & Janowski [65] | “Electronic Governance for Sustainable Development—Conceptual Framework and State of Research” | Government Information Quarterly | Conceptual and development-oriented frameworks | Highlights the role of ICT in facilitating sustainable development through better governance practices. |

| Ferreira & Ritta Coelho [66] | “Factors of Engagement in E-Participation in a Smart City” | ICEGOV 2022 Conference | E-participation and citizen-centric governance frameworks | Identifies challenges in maintaining citizen engagement through ICT platforms and offers suggestions for improvement. |

| Fu & Zhang [67] | “Trajectory of Urban Sustainability Concepts: A 35-Year Bibliometric Analysis” | Cities | Analytical and comparative frameworks | Shows how concepts like smart cities and sustainable cities overlap and evolve, promoting integrated frameworks for urban sustainability. |

| Grossi & Welinder [68] | “Smart Cities at the Intersection of Public Governance Paradigms for Sustainability” | Urban Studies | Analytical and comparative frameworks | Demonstrates how smart city governance can achieve social, economic, and environmental sustainability outcomes. |

| Haarstad & Wathne [69] | “Are Smart City Projects Catalyzing Urban Energy Sustainability?” | Energy Policy | Analytical and comparative frameworks | Smart city projects increase ambition for energy sustainability but face challenges in accountability. |

| Haarstad [70] | “Constructing the Sustainable City: Examining the Role of Sustainability in the ‘Smart City’ Discourse” | Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning | Analytical and comparative frameworks | Highlights the weak focus on sustainability within smart city strategies, driven by economic priorities. |

| He et al. (2017) [71] | “E-Participation for Environmental Sustainability in Transitional Urban China” | Sustainability Science | E-participation and citizen-centric governance frameworks | Emphasizes the role of ICTs in empowering public engagement but notes barriers to participation in China. |

| He et al. (2022) [72] | “Legal Governance in the Smart Cities of China: Functions, Problems, and Solutions” | Sustainability | Governance and policy frameworks | Identifies challenges in data governance, recommending improved legal frameworks to support smart city development. |

| Herdiyanti et al. [73] | “Modelling the Smart Governance Performance to Support Smart City Program in Indonesia” | Procedia Computer Science | Analytical and comparative frameworks | Provides insights into challenges of implementing smart city initiatives in Indonesia without standardized frameworks. |

| Huovila et al. [74] | “Comparative Analysis of Standardized Indicators for Smart Sustainable Cities: What Indicators and Standards to Use and When?” | Cities | Analytical and comparative frameworks | Offers practical recommendations for selecting appropriate indicators based on urban sustainability goals. |

| Ibrahim et al. [75] | “Smart Sustainable Cities Roadmap: Readiness for Transformation towards Urban Sustainability” | Sustainable Cities & Society | Smart cities and sustainability frameworks | Proposes phases to assess city readiness for change, considering local challenges and opportunities. |

| Jiang [76] | “Smart Urban Governance in the ‘Smart’ Era: Why Is It Urgently Needed?” | Cities | Governance and policy frameworks | Advocates for a shift from technology-driven to demand-pulled governance, focusing on urban issues. |

| Kato & Takizawa [77] | “Urban Transformation and Population Decline in Old New Towns in the Osaka Metropolitan Area” | Cities | Conceptual and development-oriented frameworks | Highlights the shift in New Towns from child-centric to elderly-centric urban structure. |

| Lange et al. [78] | “Governing Towards Sustainability—Conceptualizing Modes of Governance” | Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning | Governance and policy frameworks | Suggests multi-dimensional governance focusing on politics, policy, and polity aspects. |

| Lim & Yigitcanla [10] | “Participatory Governance of Smart Cities: Insights from E-Participation of Putrajaya and Petaling Jaya, Malaysia” | Smart Cities | E-participation and citizen-centric governance frameworks | Identifies political and institutional challenges in achieving effective participatory governance in Malaysia. |

| Martin et al. [79] | “Smart Sustainability: A New Urban Fix?” | Sustainable Cities & Society | Smart cities and sustainability frameworks | Critiques smart-sustainability initiatives as amplifying ecological modernization without true transformation. |

| Meuleman & Niestroy [80] | “Common But Differentiated Governance: A Metagovernance Approach to Make the SDGs Work” | Sustainability | Governance and policy frameworks | Recommends situationally appropriate governance to enhance SDG implementation efforts. |

| Mooij [29] | “Smart Governance? Politics in the Policy Process in Andhra Pra-desh, India” | Overseas Development Institute | Conceptual and development-oriented frameworks | Highlights contradictions in governance reform and policy implementation in Andhra Pradesh. |

| Mutiara et al. [3] | “Smart Governance for Smart City” | IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science | Smart cities and sustainability frameworks | Evaluates the effectiveness of e-governance and public information disclosure laws in Indonesia. |

| Ochara [81] | “Grassroots Community Participation as a Key to e-Governance Sustainability in Africa” | “The African Journal of Information and Communication” | E-participation and citizen-centric governance frameworks | Emphasizes the need for community involvement in e-governance to reduce digital divides |

| Palacin et al. [82] | “Reframing E-Participation for Sustainable Development” | “ICEGOV” | E-participation and citizen-centric governance frameworks | Demonstrates how e-participation supports sustainable development and aligns with the 2030 Agenda. |

| Paskaleva [83] | “Enabling the Smart City: The Progress of City e-Governance in Europe” | International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development | Conceptual and development-oriented frameworks | Highlights the need for integrated e-services and partnerships to support smart governance. |

| Patterson et al. [84] | “Exploring the governance and Politics of Transformations Towards Sustainability” | Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions | Governance and policy frameworks | Identifies challenges in sustainability transitions and emphasizes the importance of political alignment. |

| Rahman et al. [85] | “From E-Governance to Smart Governance: Policy Lessons for the UAE” | Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance | Governance and policy frameworks | Analyzes the UAE’s success and challenges in adopting smart governance practices, with policy recommendations for improvement. |

| Rochet & Belemlih [86] | “Social Emergence, Cornerstone of Smart City Governance as a Complex Citizen-Centric System” | Handbook of Smart Cities | E-participation and citizen-centric governance frameworks | Highlights how bottom-up dynamics drive smart governance, using Barcelona and Medellín as case studies. |

| Tewari & Datt [87] | “Towards FoT (Fog-of-Things) Enabled Architecture in Governance: Transforming e-Governance to Smart Governance” | International Conference on Intelligent Engineering and Management (ICIEM) | Conceptual and development-oriented frameworks | Proposes a decentralized architecture for smart governance to enhance efficiency and real-time decision-making. |

| Toli & Murtagh [88] | “The Concept of Sustainability in Smart City Definitions” | Frontiers in Built Environment | Smart cities and sustainability frameworks | Identifies inconsistencies in smart city definitions and suggests aligning them with sustainability goals. |

| Turnheim et al. [89] | “Evaluating Sustainability Transitions Pathways: Bridging Analytical Approaches to Address Governance Challenges” | Global Climate Change | Conceptual and development-oriented frameworks | Offers a holistic approach to evaluate sustainability transitions and overcome governance challenges. |

| Yahia et al. [90] | “Towards Sustainable Collaborative Networks for Smart Cities Co-Governance” | International Journal of Information Management | Analytical and comparative frameworks | Identifies organizational structures promoting robust and sustainable collaboration among stakeholders. |

| Yigitcanlar & Kamruzzaman [32] | “Does Smart City Policy Lead to Sustainability of Cities?” | Land Use Policy | Smart cities and sustainability frameworks | Reveals that the link between smart cities and reduced CO2 emissions is not linear, recommending better policy alignment. |

| Zachary & Jared [91] | “Characterizing E-Participation Levels in E-Governance” | International Journal of Scientific Research and Innovative Technology” | E-participation and citizen-centric governance frameworks | Highlights gaps in citizen engagement and offers recommendations to improve transparency and accountability. |

| Zhu et al. [92] | “How Different Can Smart Cities Be? A Typology of Smart Cities in China” | Cities | Smart cities and sustainability frameworks | Provides a typology identifying five distinct types of smart cities based on governance and technological approaches. |

References

- Alajmi, M.; Mohammadian, M.; Talukder, M. The Determinants of Smart Government Systems Adoption by Public Sector Organizations in Saudi Arabia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, Z.R.M.A. Smart Governance for Smart Cities and Nations. J. Econ. Technol. 2024, 2, 216–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutiara, D.; Yuniarti, S.; Pratama, B. Smart Governance for Smart City. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, A.; Bolívar, M.P.R. Governing the Smart City: A Review of the Literature on Smart Urban Governance. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2015, 82, 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomor, Z.; Albert, M.; Ank, M.; Geertman, S. Smart Governance for Sustainable Cities: Findings from a Systematic Literature Review. J. Urban Technol. 2019, 26, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repette, P.; Sabatini-Marques, J.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Sell, D.; Costa, E. The Evolution of City-as-a-Platform: Smart Urban Development Governance with Collective Knowledge-Based Platform Urbanism. Land 2021, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A.I. Building Urban Resilience Through Smart City Planning: A Systematic Literature Review. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotta, M.J.R.; Sell, D.; dos Santos Pacheco, R.C.; Yigitcanlar, T. Digital Commons and Citizen Co-Production in Smart Cities: Assessment of Brazilian Municipal E-Government Platforms. Energies 2019, 12, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.B.; Malek, J.A.; Yussoff, M.F.Y.M.; Yigitcanlar, T. Understanding and Acceptance of Smart City Policies: Practitioners’ Perspectives on the Malaysian Smart City Framework. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Yigitcanlar, T. Participatory Governance of Smart Cities: Insights from E-Participation of Putrajaya and Petaling Jaya, Malaysia. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Li, R.; Beeramoole, P.; Paz, A. Artificial Intelligence in Local Government Services: Public Perceptions from Australia and Hong Kong. Gov. Inf. Q. 2023, 40, 101833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalki, F.A.; Alsamhi, S.; Sahal, R.; Hassan, J.; Hawbani, A.; Rajput, N.; Saif, A.; Morgan, J.; Breslin, J. Green IoT for Eco-Friendly and Sustainable Smart Cities: Future Directions and Opportunities. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2023, 28, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przeybilovicz, E.; Cunha, M.A. Governing in the Digital Age: The Emergence of Dynamic Smart Urban Governance Modes. Gov. Inf. Q. 2024, 41, 101907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, C.; Bibri, S.E.; Longchamp, R.; Golay, F.; Alahi, A. Urban Digital Twin Challenges: A Systematic Review and Perspectives for Sustainable Smart Cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Abbott, K.; Andresen, S.; Bäckstrand, K.; Bernstein, S.; Betsill, M.M.; Bulkeley, H.; Cashore, B.; Clapp, J.; Folke, C.; et al. Transforming Governance and Institutions for Global Sustainability: Key Insights from the Earth System Governance Project. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Zhang, Y.; Jeon, G.; Lin, W.; Khosravi, M.R.; Qi, L. A Blockchain–and Artificial Intelligence–Enabled Smart IoT Framework for Sustainable City. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 6493–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, H.; Mittal, M. Adoption of Artificial Intelligence in Smart Cities: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Verma, A.K.; Mirza, A. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Governance Systems: Smart Cities and Smart Governance. In Digital Transformation, Artificial Intelligence and Society. Frontiers of Artificial Intelligence, Ethics and Multidisciplinary Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, K.J.; Cradock-Henry, N.A.; Koch, F.; Patterson, J.; Häyhä, T.; Vogt, J.; Barbi, F. Implementing the “Sustainable Development Goals”: Towards Addressing Three Key Governance Challenges—Collective Action, Trade-Offs, and Accountability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, L.-M.; Newig, J. Governance for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: How Important Are Participation, Policy Coherence, Reflexivity, Adaptation and Democratic Institutions? Earth Syst. Gov. 2019, 2, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regona, M.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Hon, C.; Teo, M. Artificial Intelligence and Sustainable Development Goals: Systematic Literature Review of the Construction Industry. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 108, 105499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Allam, Z.; Bibri, S.E.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R. Smart Cities and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Systematic Literature Review of Co-Benefits and Trade-Offs. Cities 2024, 146, 104659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A.I.; Sharifi, A.; Aina, Y.A.; Ahmad, S.; Mora, L.; Leal Filho, W.; Abubakar, I.R. Charting Sustainable Urban Development through a Systematic Review of SDG11 Research. Nat. Cities 2024, 1, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovik, S.; Giannoumis, G.A. Linkages between Citizen Participation, Digital Technology, and Urban Development. In Citizen Participation in the Information Society; Hovik, S., Giannoumis, G.A., Reichborn-Kjennerud, K., Ruano, J.M., McShane, I., Legard, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, Z.D.W.; van der Knaap, W. 6-A Smart City Needs More Than Just Technology: Amsterdam’s Energy Atlas Project. In Smart City Emergence: Cases from Around the World; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, K. Development of a Citizen-Centric E-Government Model for Effective Service Delivery in Namibia. Master’s Thesis, Namibia University of Science and Technology, Windhoek, Namibia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Bulu, M. Dubaization of Istanbul: Insights from the Knowledge-Based Urban Development Journey of an Emerging Local Economy. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2015, 47, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komninos, N. Intelligent Cities: Innovation, Knowledge Systems and Digital Spaces; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooij, J. Smart Governance? Politics in the Policy Process in Andhra Pradesh; Working Paper 228; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Van Assche, K.; Beunen, R.; Verweij, S.; Evans, J.; Gruezmacher, M. Policy Learning and Adaptation in Governance: A Co-Evolutionary Perspective. Adm. Soc. 2021, 54, 1226–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.P.R. Chapter 13: Citizens Engagement in Policy Making: Insights from an E-Participation Platform in Leuven, Belgium. In Engaging Citizens in Policy Making; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Kamruzzaman, M. Does Smart City Policy Lead to Sustainability of Cities? Land Use Policy 2018, 73, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clune, W.H.; Zehnder, A.J.B. The Three Pillars of Sustainability Framework: Approaches for Laws and Governance. J. Environ. Prot. 2018, 9, 211–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Geertman, S.; Witte, P. Smart Urban Governance: An Alternative to Technocratic “Smartness”. GeoJournal 2022, 87, 1639–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Buys, L.; Ioppolo, G.; Sabatini-Marques, J.; da Costa, E.M.; Yun, J.J. Understanding “Smart Cities”: Intertwining Development Drivers with Desired Outcomes in a Multidimensional Framework. Cities 2018, 81, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.N.; Wu, M.; Hossin, M.A. Smart Governance through Big Data: Digital Transformation of Public Agencies. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Big Data (ICAIBD), Chengdu, China, 26–28 May 2018; pp. 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandt, J.; Batty, M. Smart Cities, Big Data and Urban Policy: Towards Urban Analytics for the Long Run. Cities 2021, 109, 102992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Marano, V.; Tashman, P. The Corporate Governance of Environmental Sustainability: A Review and Proposal for More Integrated Research. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1468d1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahvenniemi, H.; Huovila, A.; Pinto-Seppä, I.; Airaksinen, M. What Are the Differences Between Sustainable and Smart Cities? Cities 2017, 60, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akmentina, L.E. Participation and Engagement in Urban Planning: Experiences from the Baltic Cities. Urban Res. Pract. 2022, 16, 624–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benites, A.J.; Simoes, A.F. Assessing the Urban Sustainable Development Strategy: An Application of a Smart City Services Sustainability Taxonomy. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 127, 107734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.E.; Krogstie, J. Generating a Vision for Smart Sustainable Cities of the Future: A Scholarly Backcasting Approach. Eur. J. Futures Res. 2019, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelnovo, W.; Misuraca, G.; Savoldelli, A. Smart Cities Governance: The Need for a Holistic Approach to Assessing Urban Participatory Policymaking. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2016, 34, 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three Pillars of Sustainability: In Search of Conceptual Origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskaleva, K.; Evans, J.; Martin, C.; Linjordet, T.; Yang, D.; Karvonen, A. Data Governance in the Sustainable Smart City. Informatics 2017, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Degirmenci, K.; Butler, L.; Desouza, K.C. What Are the Key Factors Affecting Smart City Transformation Readiness? Evidence from Australian Cities. Cities 2022, 120, 103434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underdal, A. Complexity and Challenges of Long-Term Environmental Governance. Glob. Environ. Change 2010, 20, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G.V.; Parycek, P.; Falco, E.; Kleinhans, R. Smart Governance in the Context of Smart Cities: A Literature Review. Inf. Polity 2018, 23, 143–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Dhunny, Z.A. On Big Data, Artificial Intelligence and Smart Cities. Cities 2019, 89, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Raeei, M. The Smart Future for Sustainable Development: Artificial Intelligence Solutions for Sustainable Urbanization. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 33, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, A.L.C.; Thomé, A.M.T.; Scavarda, A.J. Sustainable Urban Infrastructure: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 128, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Pisani, J.A. Sustainable Development–Historical Roots of the Concept. Environ. Sci. 2006, 3, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, J. Sustainable Development: Meaning, History, Principles, Pillars, and Implications for Human Action: Literature Review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1653531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Tracking Progress towards Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements; SDG 11 Synthesis Report—High Level Political Forum; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sdg-11-synthesis-report (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Song, K.; Chen, Y.; Duan, Y.; Zheng, Y. Urban Governance: A Review of Intellectual Structure and Topic Evolution. Urban Gov. 2023, 3, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Sharifi, A.; Bibri, S.E.; Chabaud, D. Emerging Trends and Knowledge Structures of Smart Urban Governance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nasrawi, S.; Adams, C.; El-Zaart, A. Smartness of Smart Sustainable Cities: A Multidimensional Dynamic Process Fostering Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Smart Cities, Systems, Devices and Technologies (SMART 2016), Valencia, Spain, 22–26 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, A.I. E-Participation and Local Governance: A Case Study. Theor. Empir. Res. Urban Manag. 2009, 4, 49–62. Available online: https://um.ase.ro/no12/4.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Angelidou, M.; Psaltoglou, A.; Komninos, N.; Kakderi, C.; Tsarchopoulos, P.; Panori, A. Enhancing Sustainable Urban Development Through Smart City Applications. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2018, 9, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baud, I.; Jameson, S.; Peyroux, E.; Scott, D. The Urban Governance Configuration: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Complexity and Enhancing Transitions to Greater Sustainability in Cities. Geogr. Compass 2021, 15, e12562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colding, J.; Colding, M.; Barthel, S. The Smart City Model: A New Panacea for Urban Sustainability or Unmanageable Complexity? Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2018, 47, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, M. The “Four Spheres” Framework for Sustainability. Ecol. Complex. 2006, 3, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cruz, N.F.; Rode, P.; McQuarrie, M. New Urban Governance: A Review of Current Themes and Future Priorities. J. Urban Aff. 2018, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.K. Exploring the Symbiotic Relationship between Digital Transformation, Infrastructure, Service Delivery, and Governance for Smart Sustainable Cities. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 806–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez, E.; Janowski, T. Electronic Governance for Sustainable Development—Conceptual Framework and State of Research. Gov. Inf. Q 2013, 30, S94–S109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.C.L.D.; Ritta Coelho, T. Factors of Engagement in E-Participation in a Smart City. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance (ICEGOV ‘22), New York, NY, USA, 4–7 October 2022; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, X. Trajectory of Urban Sustainability Concepts: A 35-Year Bibliometric Analysis. Cities 2017, 60, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, G.; Welinder, O. Smart Cities at the Intersection of Public Governance Paradigms for Sustainability. Urban Stud. 2024, 61, 2011–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarstad, H.; Wathne, M.W. Are Smart City Projects Catalyzing Urban Energy Sustainability? Energy Policy 2019, 129, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarstad, H. Constructing the Sustainable City: Examining the Role of Sustainability in the “Smart City” Discourse. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2016, 19, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Boas, I.; Mol, A.P.J.; Lu, Y. E-Participation For Environmental Sustainability in Transitional Urban China. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Li, W.; Deng, P. Legal Governance in the Smart Cities of China: Functions, Problems, and Solutions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdiyanti, A.; Hapsari, P.S.; Susanto, T.D. Modelling the Smart Governance Performance to Support Smart City Program in Indonesia. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 161, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huovila, A.; Bosch, P.; Airaksinen, M. Comparative Analysis of Standardized Indicators for Smart Sustainable Cities: What Indicators and Standards to Use and When? Cities 2019, 89, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; El-Zaart, A.; Adams, C. Smart Sustainable Cities Roadmap: Readiness for Transformation Towards Urban Sustainability. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H. Smart Urban Governance in the “Smart” Era: Why Is It Urgently Needed? Cities 2021, 111, 103004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Takizawa, A. Urban Transformation and Population Decline in Old New Towns in the Osaka Metropolitan Area. Cities 2024, 149, 104991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, P.; Driessen, P.P.; Sauer, A.; Bornemann, B.; Burger, P. Governing Towards Sustainability—Conceptualizing Modes of Governance. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2013, 15, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Evans, J.; Karvonen, A.; Paskaleva, K.; Yang, D.; Linjordet, T. Smart-Sustainability: A New Urban Fix? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 45, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, L.; Niestroy, I. Common But Differentiated Governance: A Metagovernance Approach to Make the SDGs Work. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12295–12321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochara, N.M. Grassroots Community Participation as a Key to E-Governance Sustainability in Africa: Section I: Themes and Approaches to Inform E-Strategies. Afr. J. Inform. Commun. 2012, 12, 26–47. [Google Scholar]

- Palacin, V.; Zundel, A.; Aquaro, V.; Kwok, W.M. Reframing E-Participation for Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance (ICEGOV ’21), Athens, Greece, 6–8 October 2021; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskaleva, K.A. Enabling the Smart City: The Progress of City E-Governance in Europe. Int. J. Innov. Reg. Dev. 2009, 1, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.; Schulz, K.; Vervoort, J.; Van Der Hel, S.; Widerberg, O.; Adler, C.; Hurlbert, M.; Anderton, K.; Sethi, M.; Barau, A. Exploring the Governance and Politics of Transformations Towards Sustainability. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2017, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]