Evaluation of the Acoustic Noise Performance of a Switched Reluctance Motor Under Different Current Control Techniques

Abstract

1. Introduction

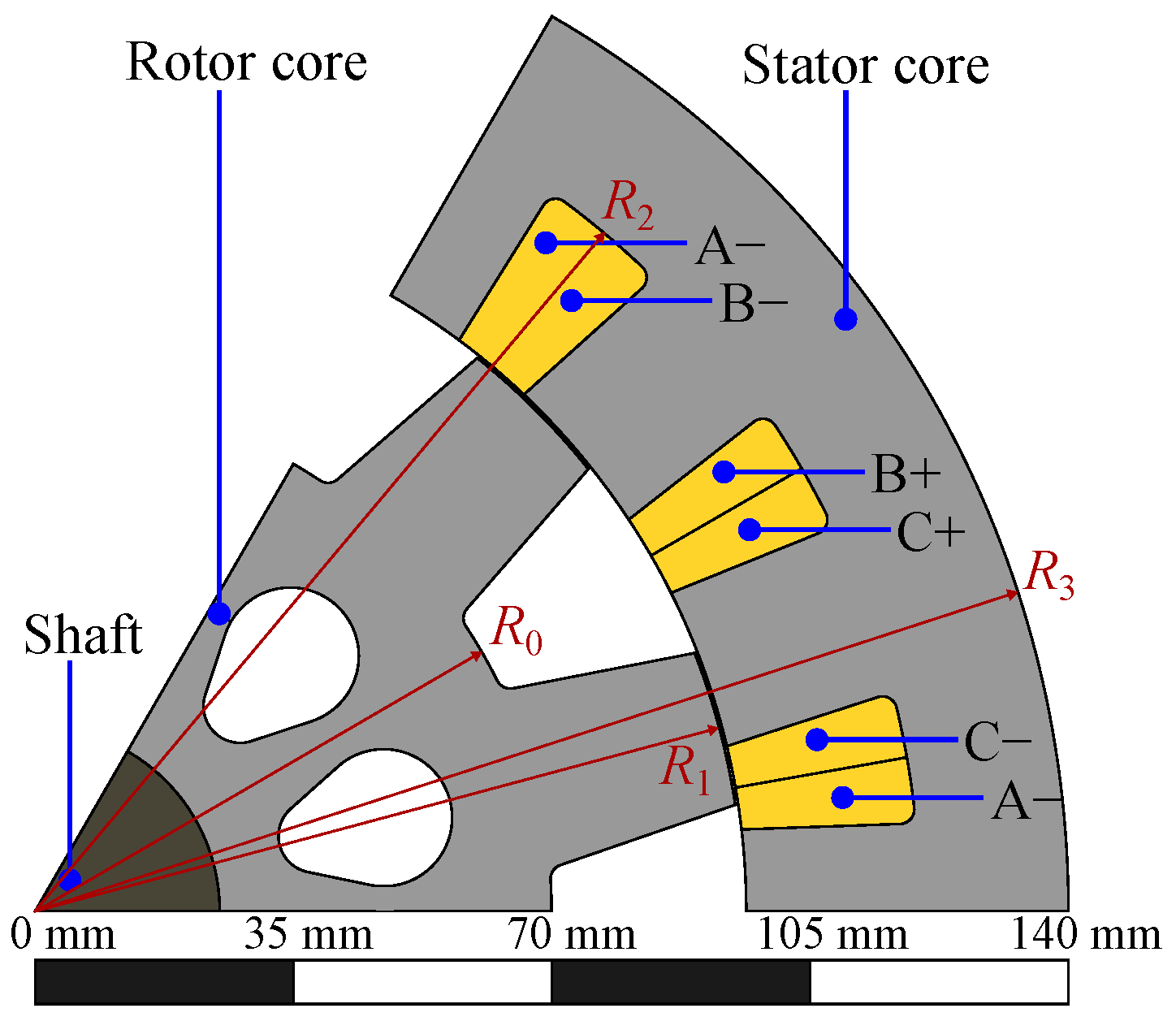

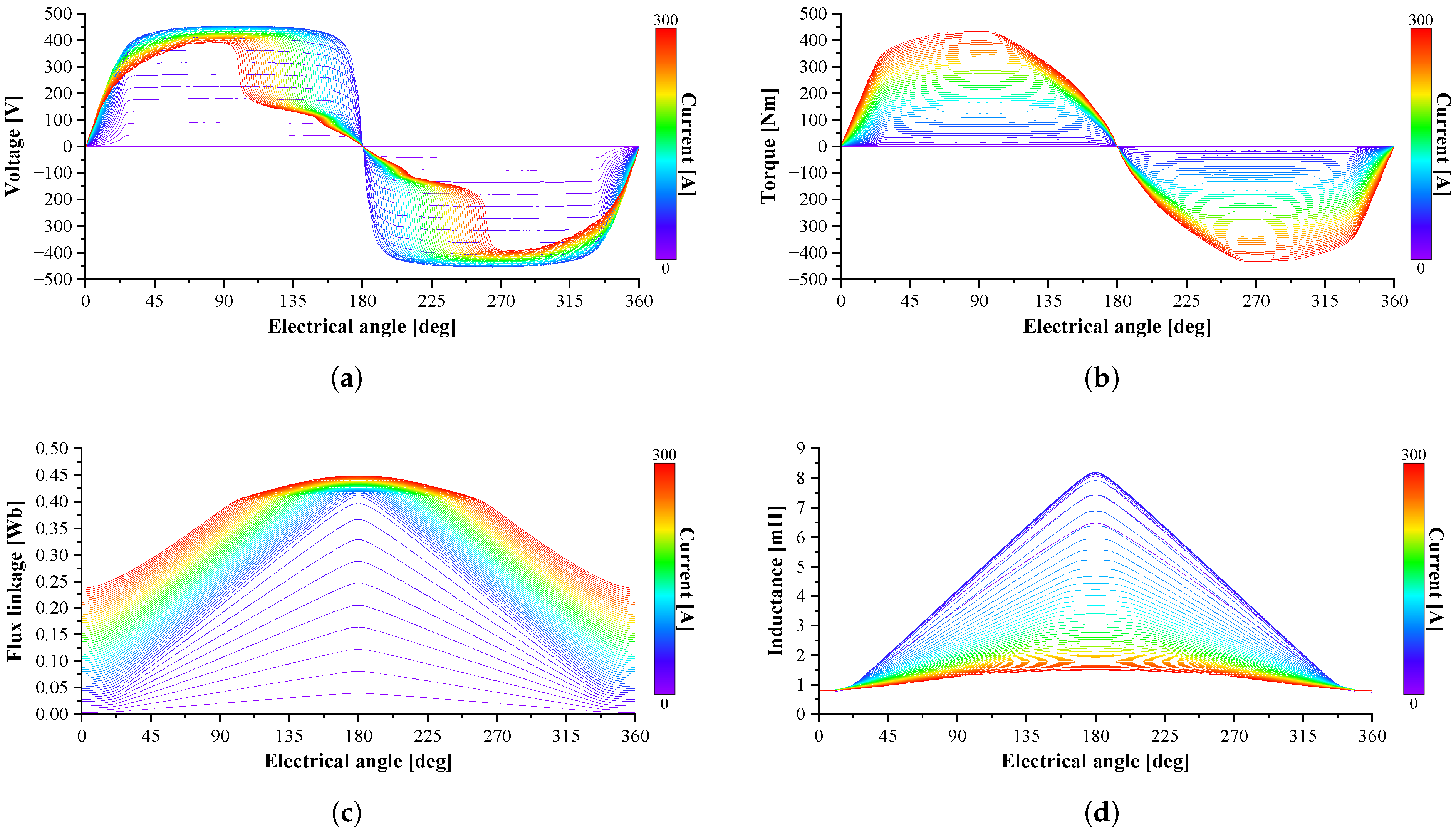

2. Electrical and Mechanical Characteristics of the Switched Reluctance Motor Under Study

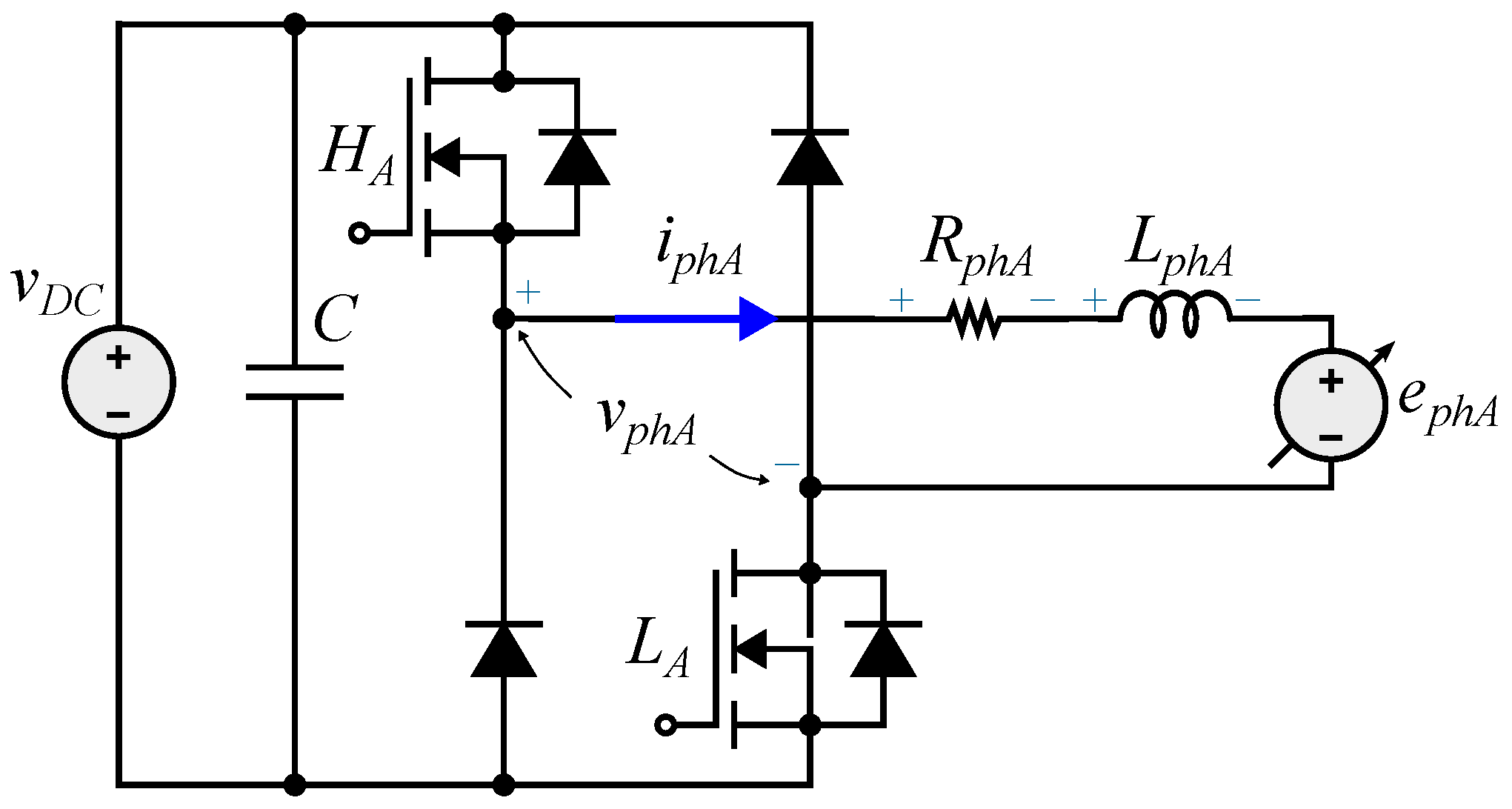

3. Mathematical Models of the Asymmetric Bridge Converter

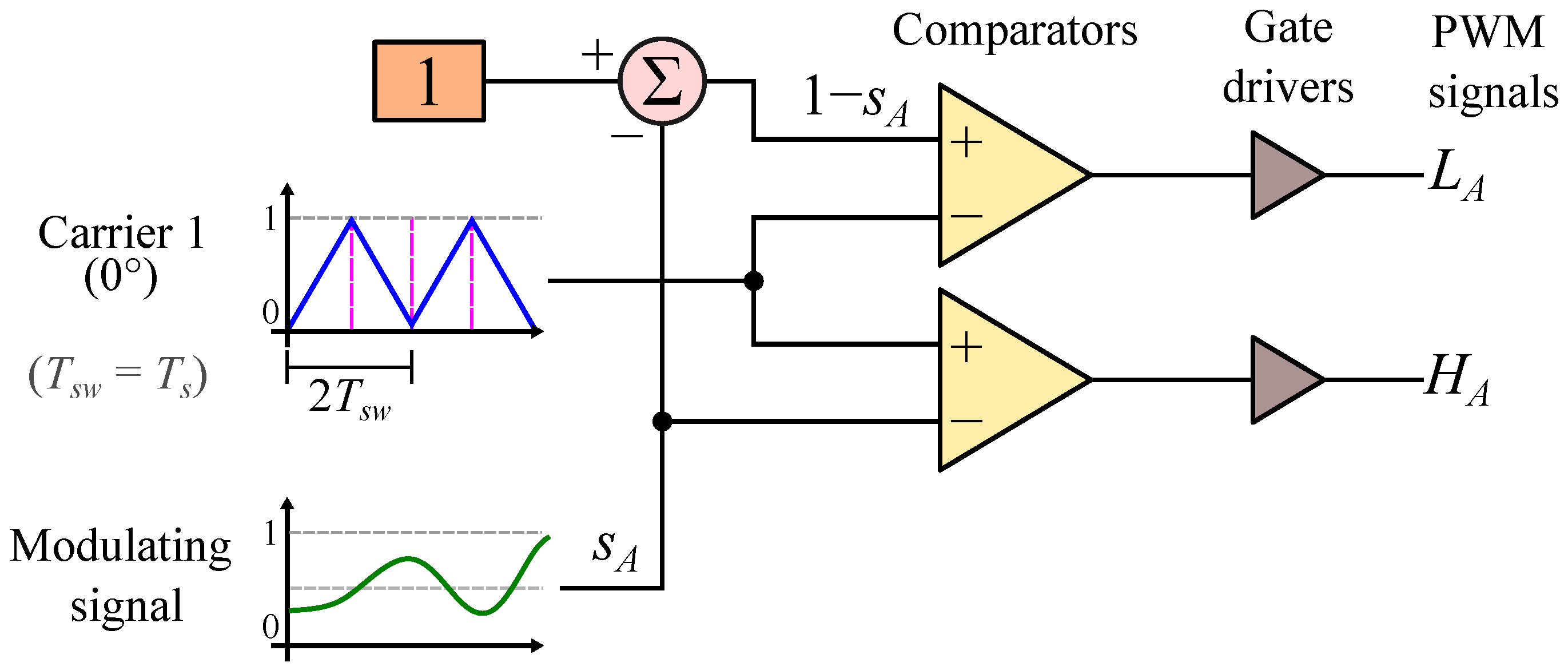

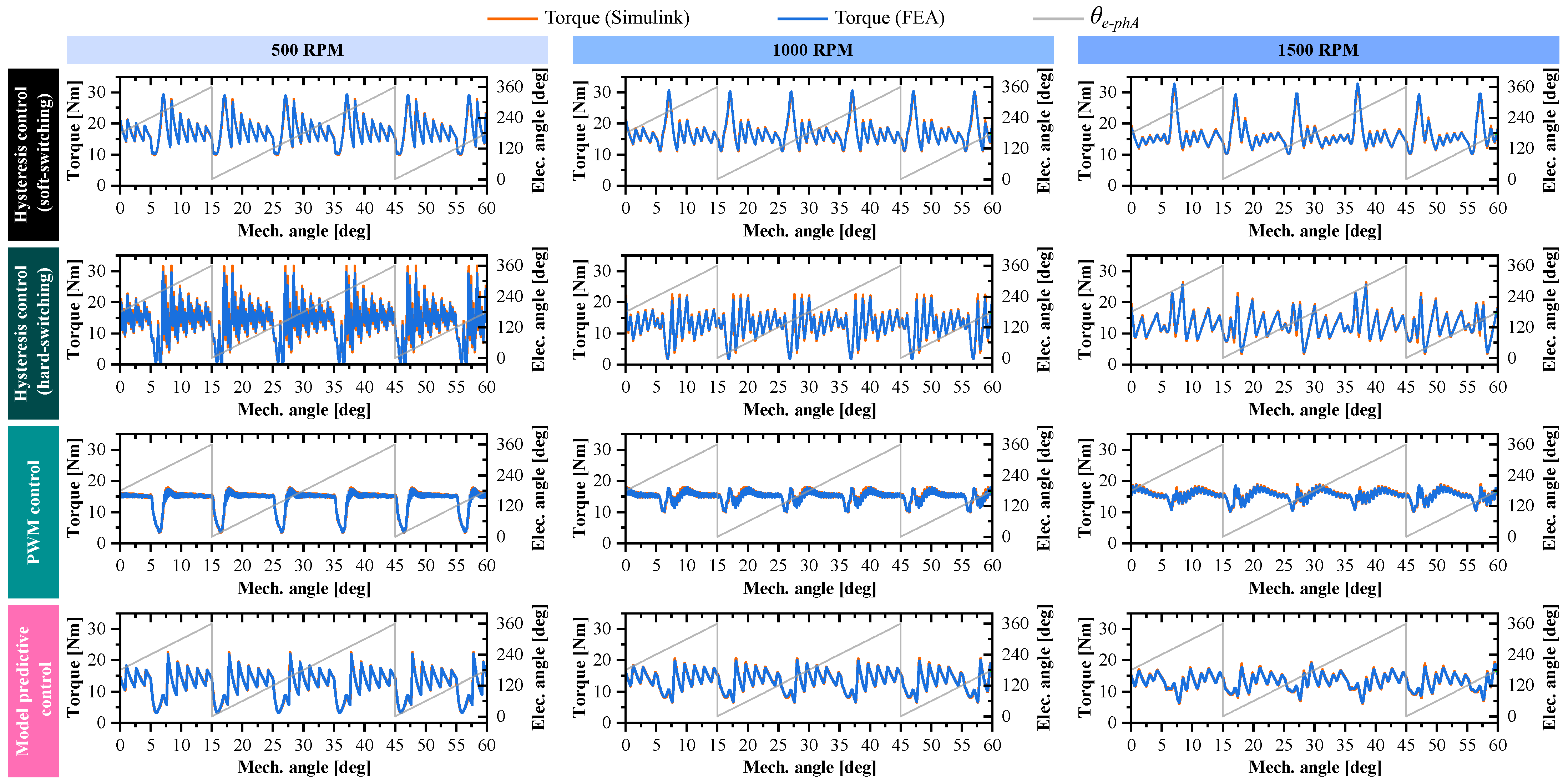

4. Current Control Techniques

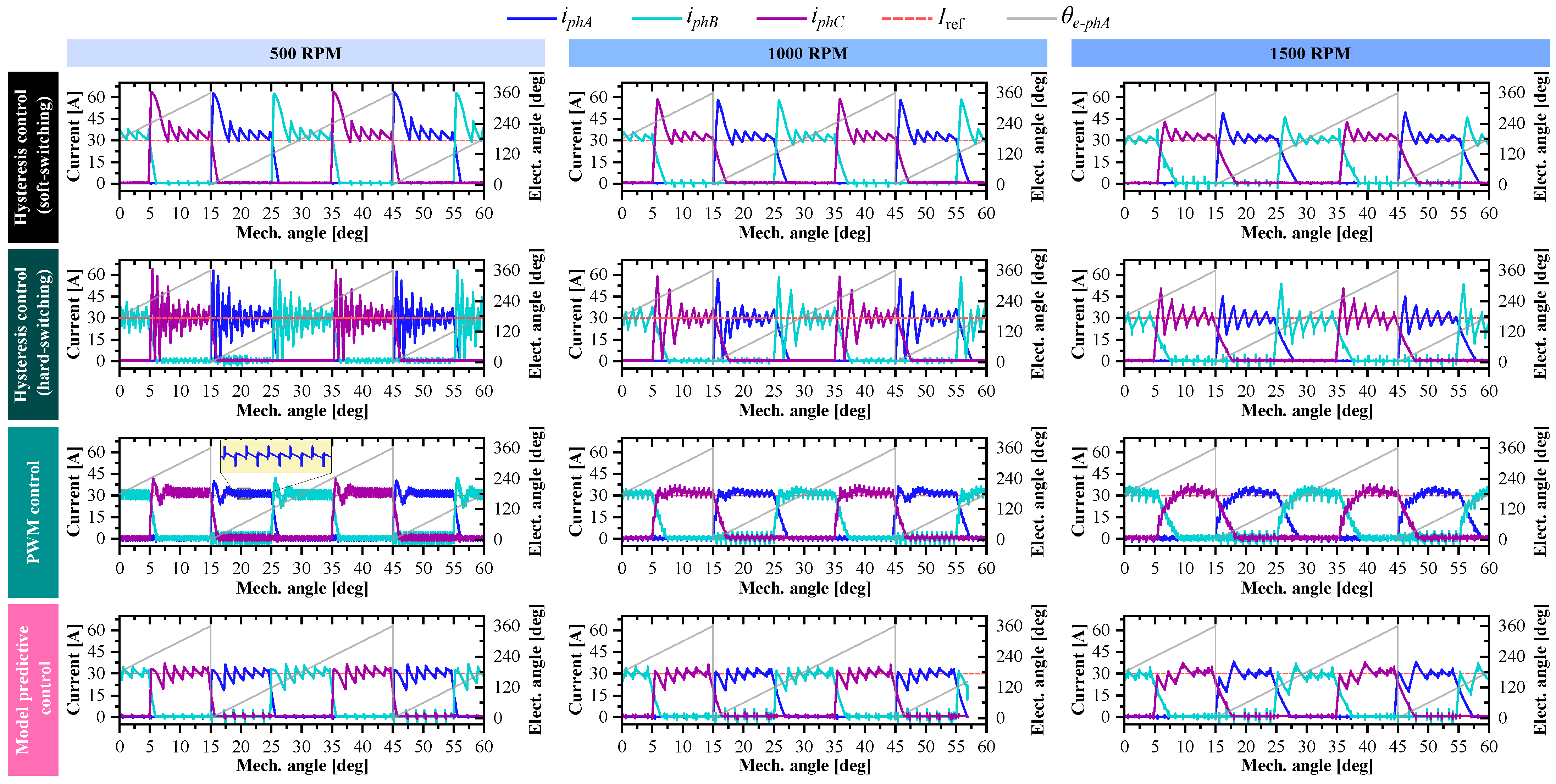

4.1. Current Control Implementation Details

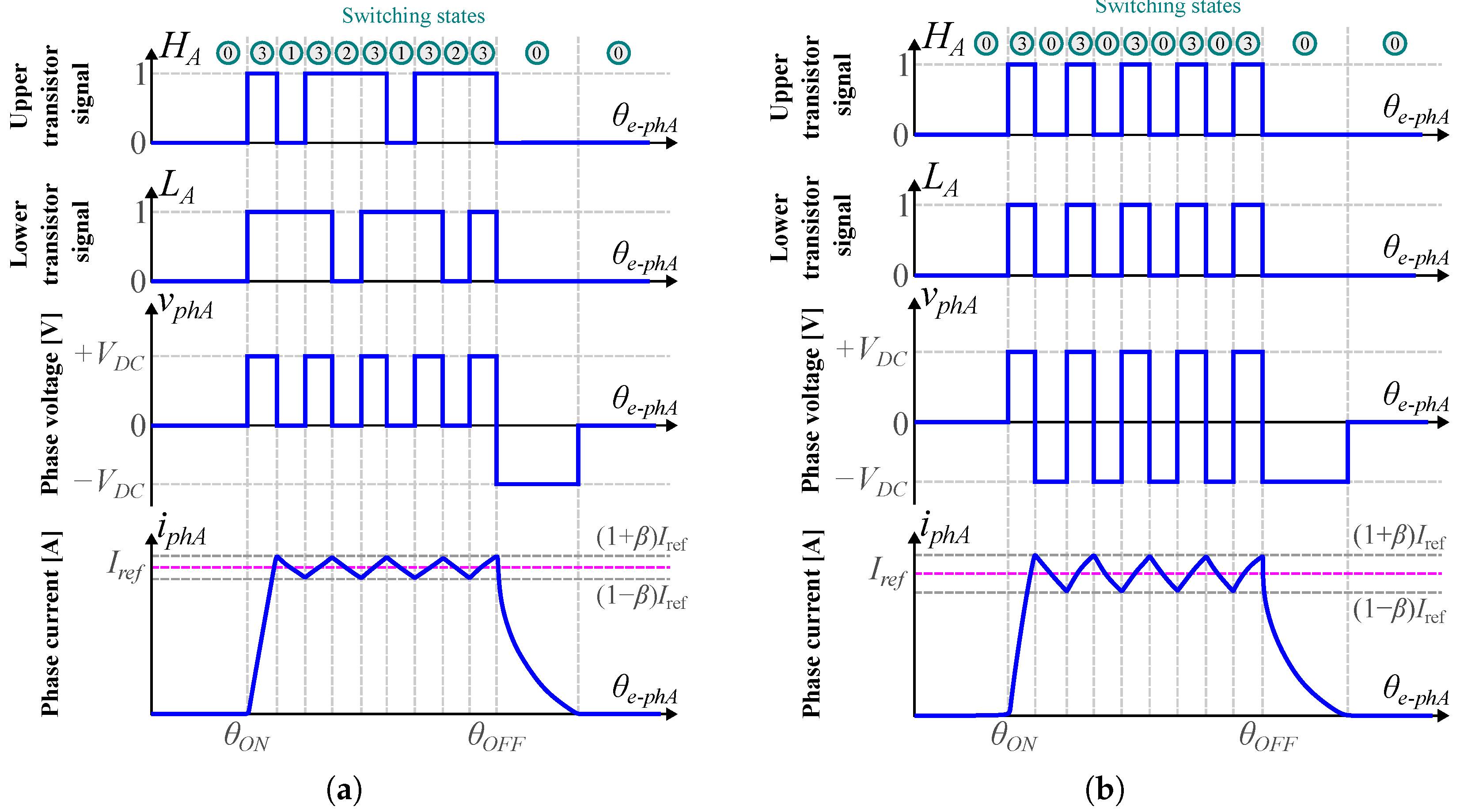

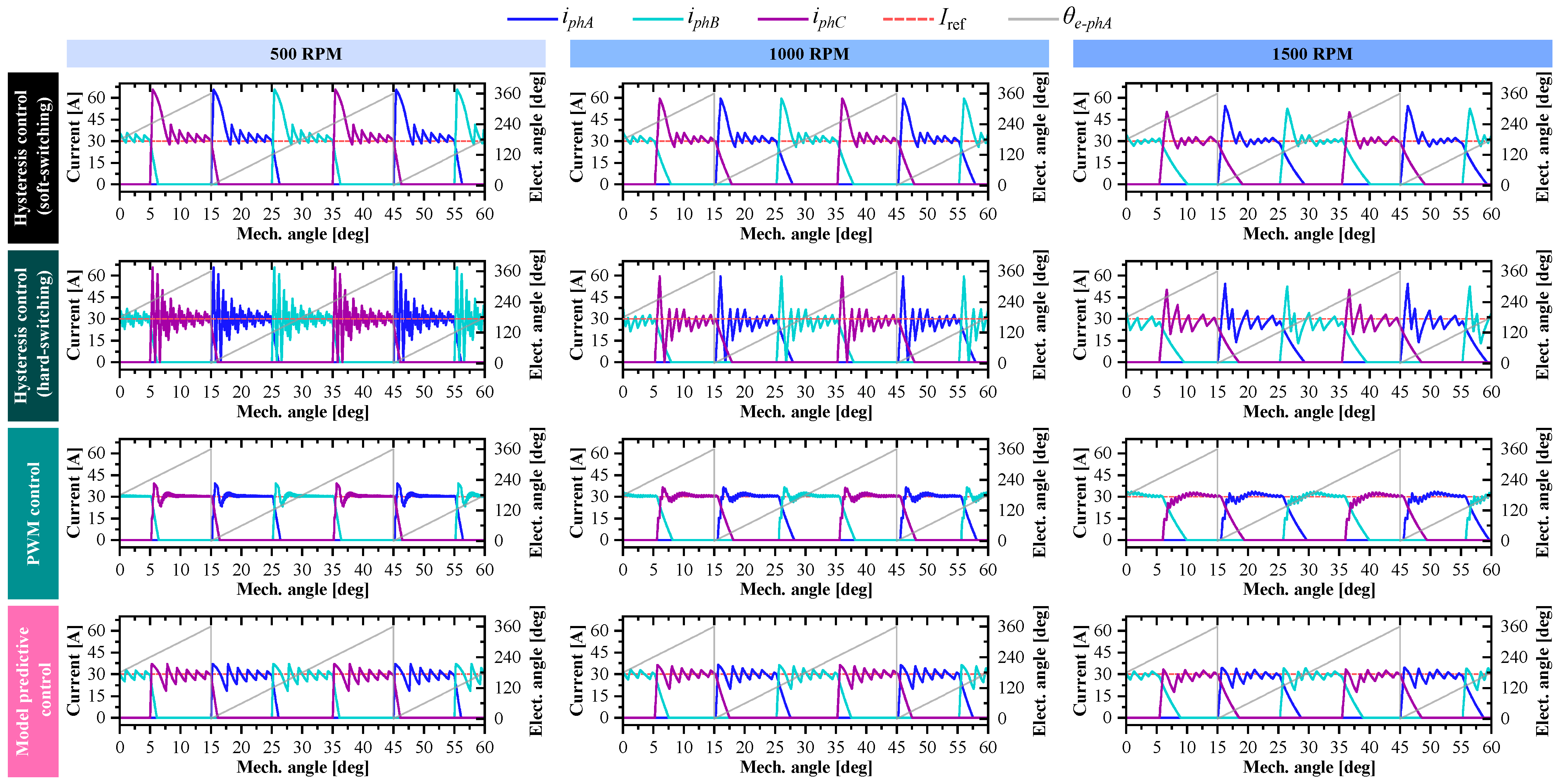

4.2. Hysteresis Control (Soft Switching)

4.3. Hysteresis Control (Hard Switching)

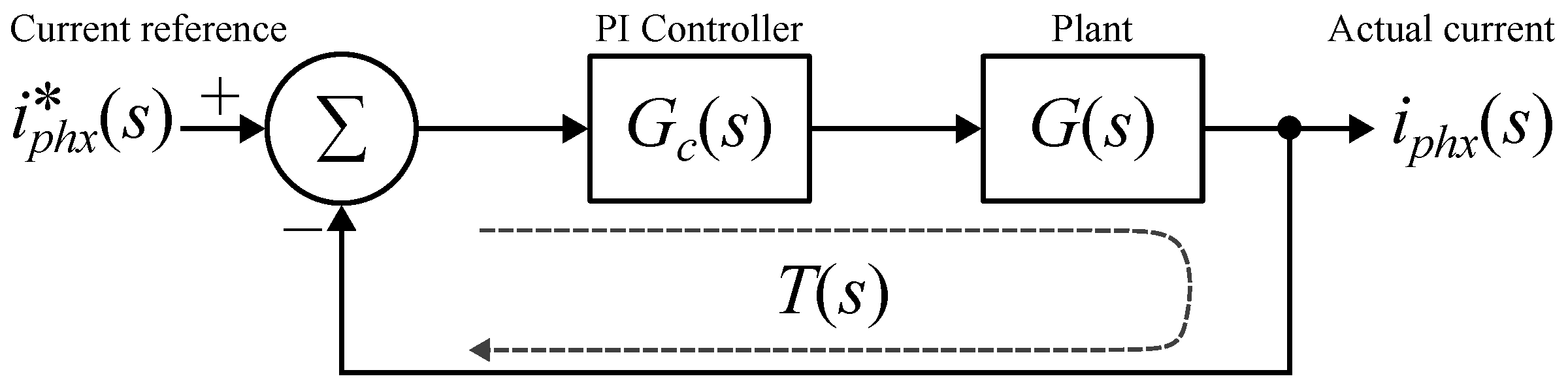

4.4. PWM Control

4.5. Model Predictive Control

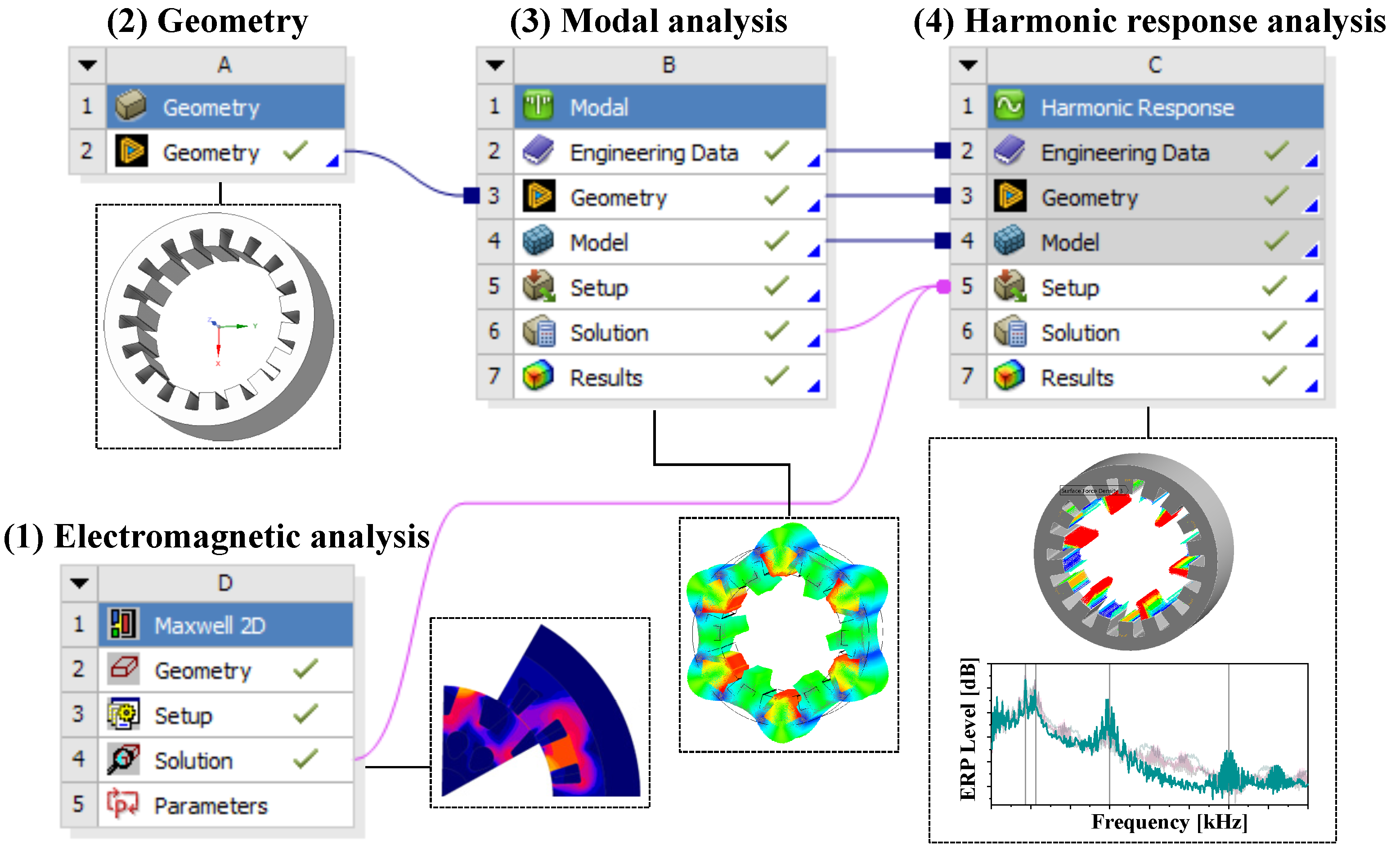

5. Acoustic Noise Modeling and Analysis of the Motor

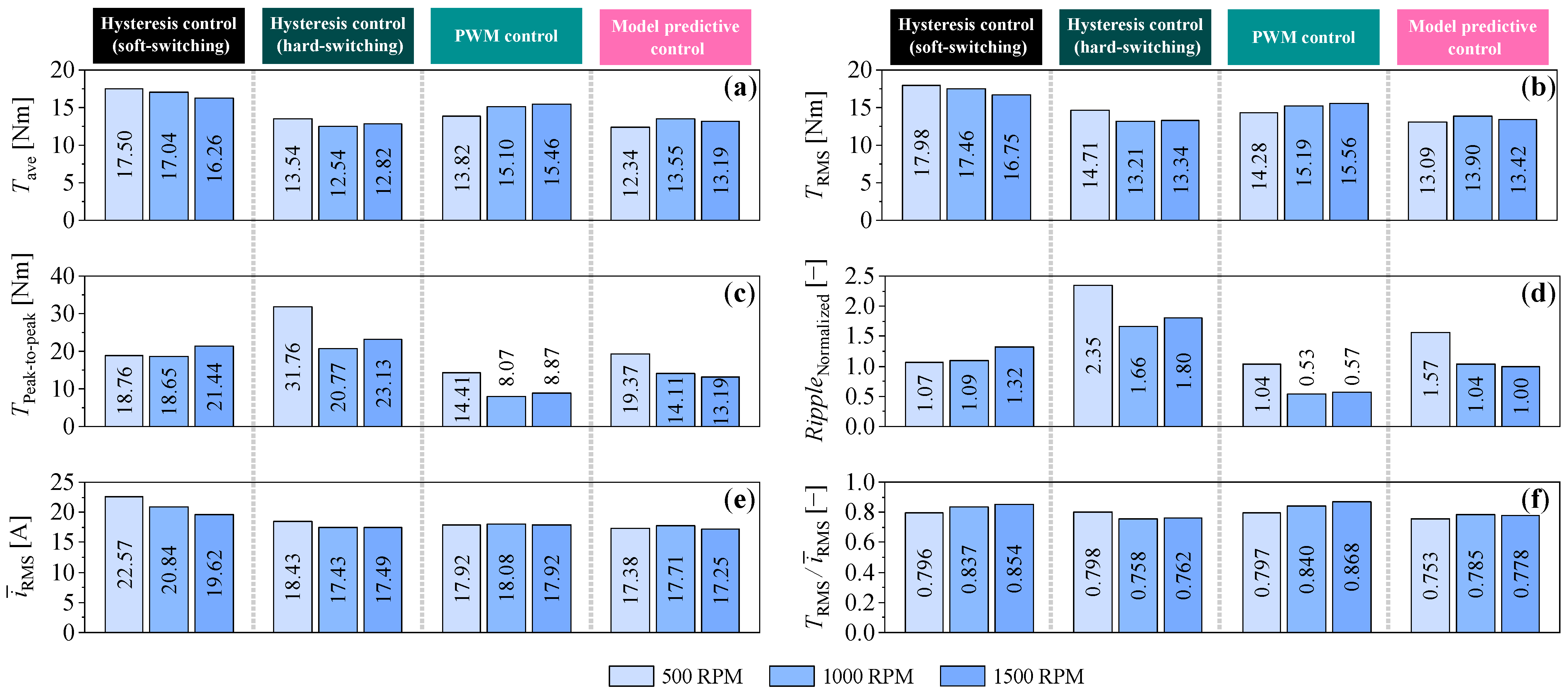

5.1. Electromagnetic Analysis

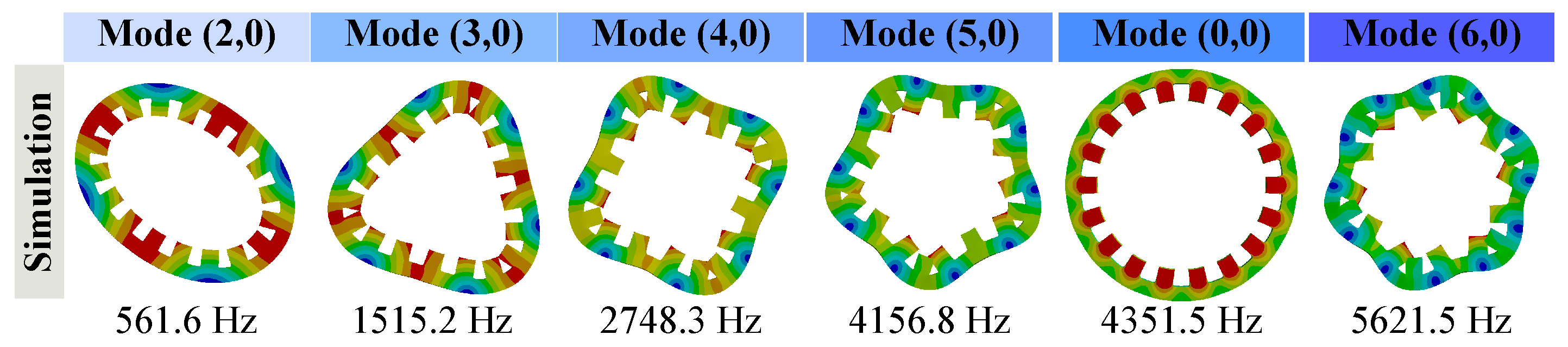

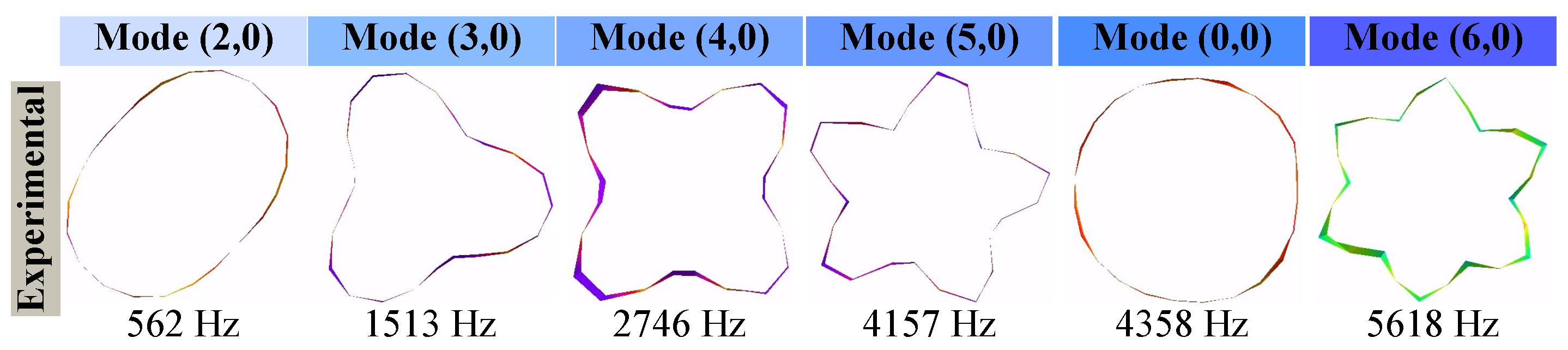

5.2. Modal Analysis

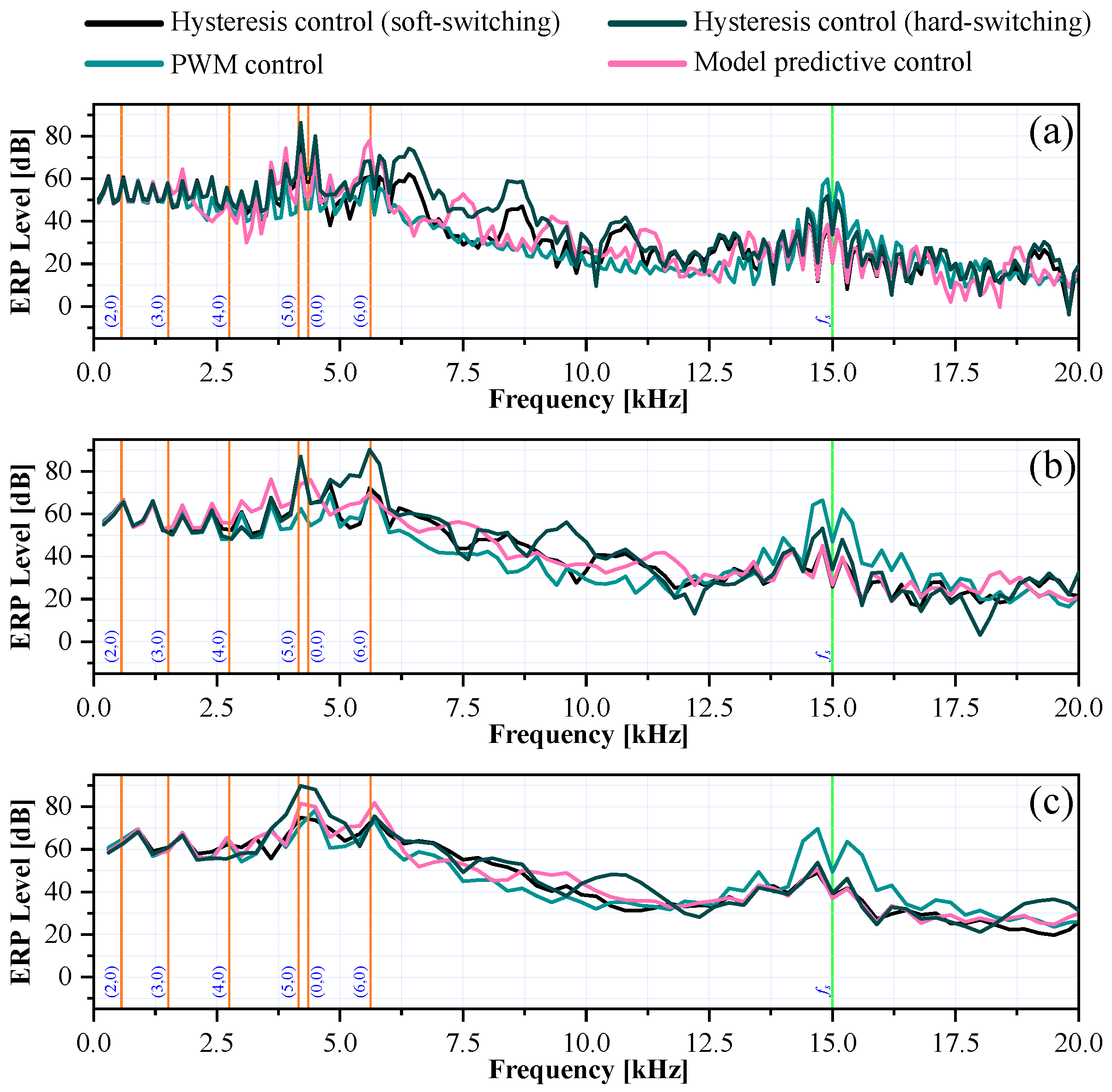

5.3. Harmonic Response Analysis

6. Experimental Validation of Switched Reluctance Motor Current Control Techniques

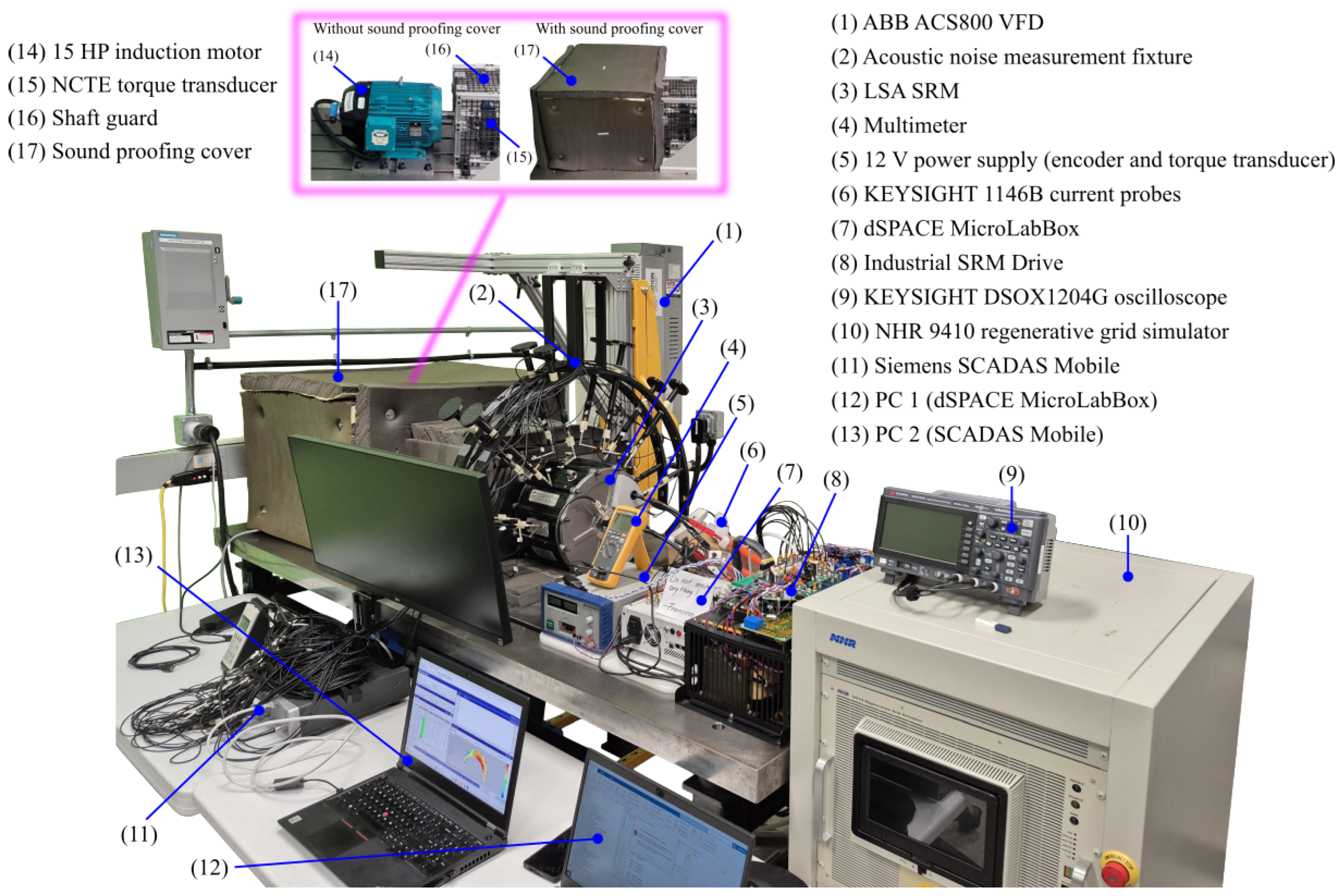

6.1. Hardware and Software Setup

6.2. Dynamometer Testing

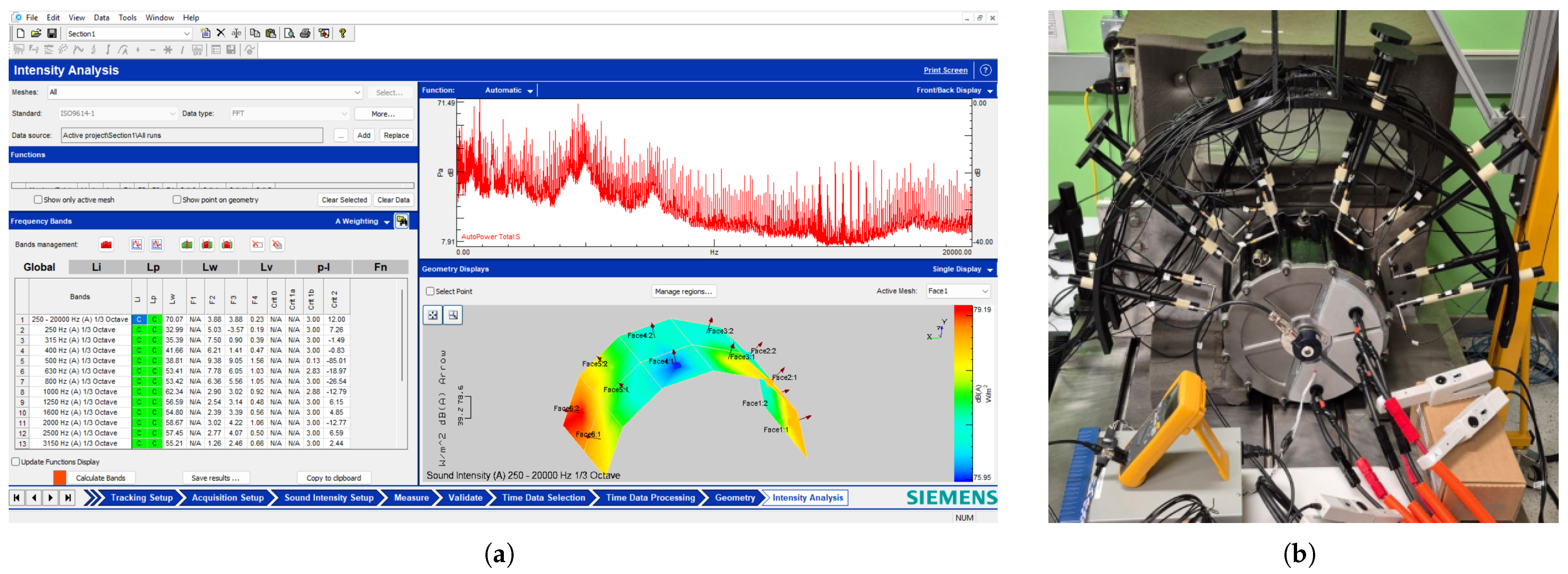

6.3. Experimental Modal Testing

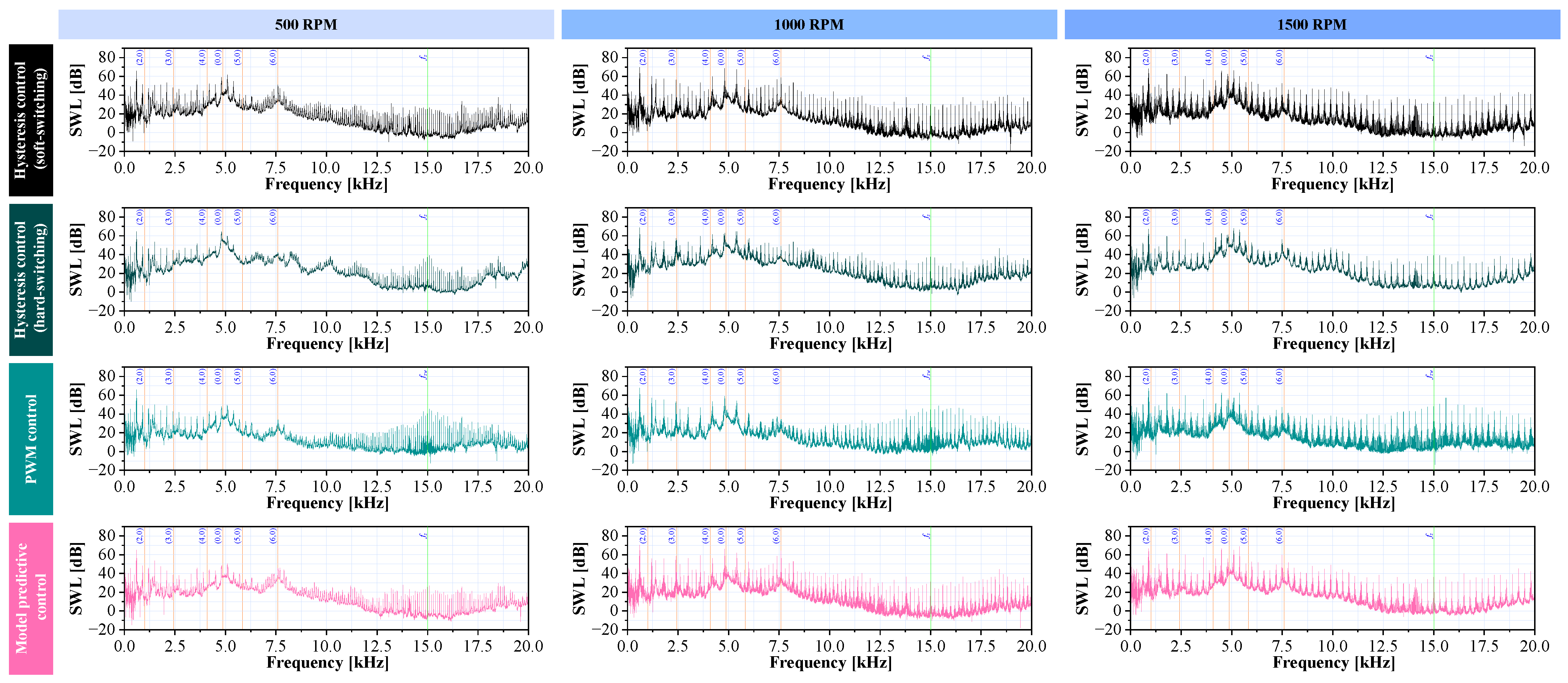

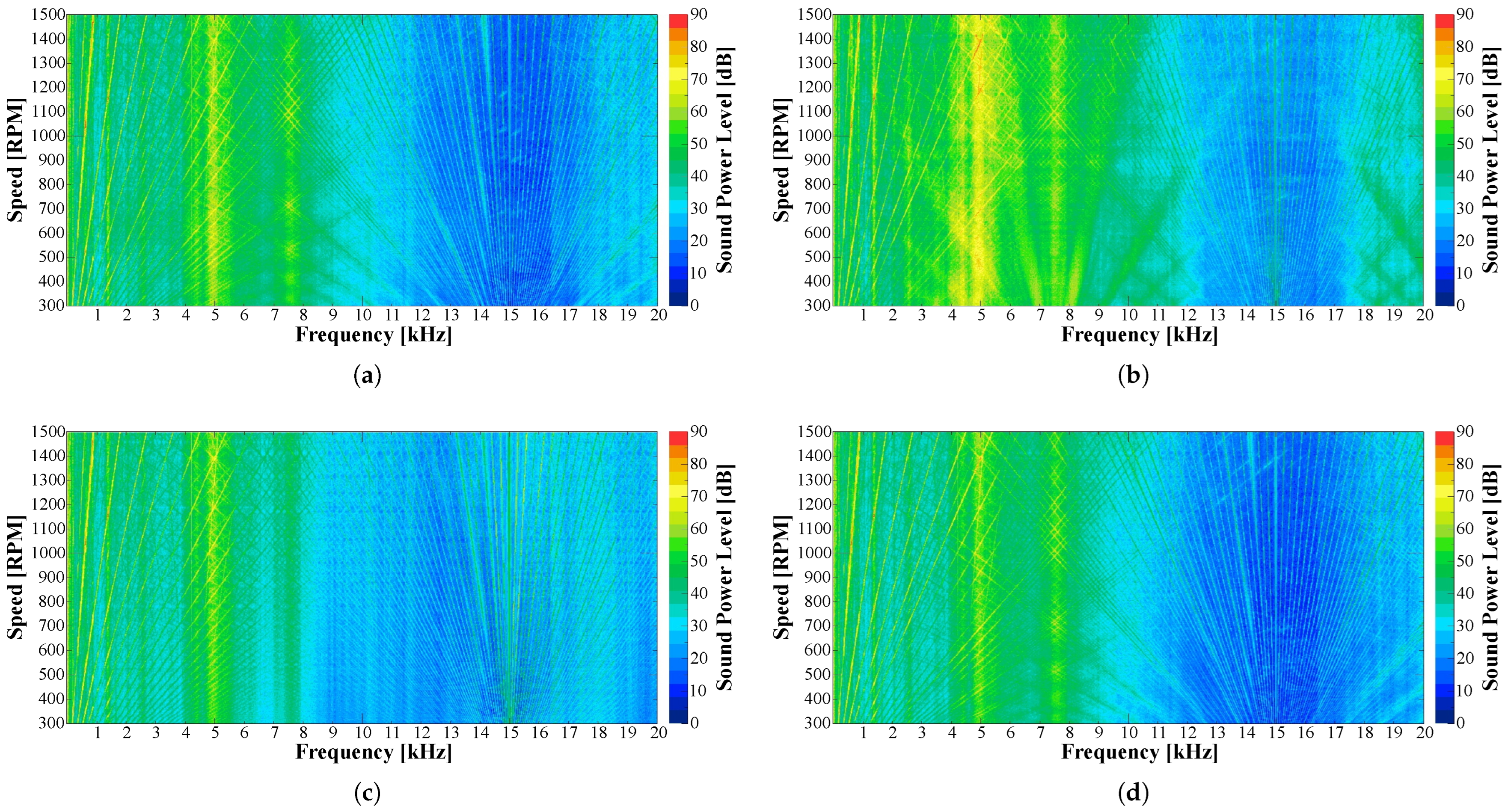

6.4. Acoustic Noise Characterization

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ERP | Equivalent Radiated Power |

| FCS | Finite Control Set |

| FEA | Finite Element Analysis |

| LUT | Lookup Table |

| MAPDL | Mechanical ANSYS Parametric Design Language |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| NVH | Noise Vibration and Harshness |

| PWM | Pulse-Width Modulation |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| SPL | Sound Pressure Level |

| SRM | Switched Reluctance Motor |

| SWL | Sound Power Level |

| TPA | Torque Per Ampere |

References

- Cakal, G.; Sarlioglu, B. Two-phase immersion cooling of high-performance electric traction motors. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 6866–6874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Shi, W.; Qiu, Y.; Li, B.; Gan, Y. Enhanced efficiency of direct-drive switched reluctance motor with reconfigurable winding topology. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 62976–62990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouannou, A.; Brouri, A.; Giri, F.; Kadi, L.; Oubouaddi, H.; Hussien, S.A.; Alwadai, N.; Mosaad, M.I. Parameter identification of switched reluctance motor SRM using exponential swept-sine signal. Machines 2023, 11, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.-W.; Lukman, G.F. Switched reluctance motor: Research trends and overview. CES Trans. Electr. Mach. Syst. 2018, 2, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Wang, H.; Li, M.; Shen, S.; Feng, Y.; Zheng, J. Torque ripple reduction for switched reluctance motor with optimized PWM control strategy. Energies 2018, 11, 3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, K.; Sun, X.; Bramerdorfer, G.; Li, G.; Wang, Q.; Wu, L. A novel analytical design theory for switched reluctance motors incorporating nonlinear characteristics. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 6775–6785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriushchenko, E.; Kallaste, A.; Mohammadi, M.H.; Lowther, D.A.; Heidari, H. Sensitivity analysis for multi-objective optimization of switched reluctance motors. Machines 2022, 10, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, P.; Kumar, R. Design of two-phase switched reluctance motor (SRM) for two-wheel electric vehicle and torque-density based comparison with three-phase SRM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 3912–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferková, Ž.; Bober, P. Influence of the rotor geometry on efficiency and torque ripple of switched reluctance motor controlled by optimized torque sharing functions. Machines 2023, 11, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Scalcon, F.P.; Xiao, D.; Vieira, R.P.; Gründling, H.A.; Emadi, A. Advanced control of switched reluctance motors (SRMs): A review on current regulation, torque control and vibration suppression. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2021, 2, 280–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yao, M.; Sun, X. A review on predictive control technology for switched reluctance motor system. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Benomar, Y.; Deepak, K.; Aksoz, A.; Baghdadi, M.E.; Bostanci, E.; Hegazy, O. Switched reluctance motors and drive systems for electric vehicle powertrains: State of the art analysis and future trends. Energies 2021, 14, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiguna, C.A.; Cai, Y.; Lilian, L.L.S.S.; Furqani, J.; Fujii, Y.; Kiyota, K.; Chiba, A. Vibration and acoustic noise reduction in switched reluctance motor by selective radial force harmonics reduction. IEEE Open J. Ind. Appl. 2023, 4, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Faouri, F.S.; Cai, Y.; Chiba, A. Refinement of analytical current waveform for acoustic noise reduction in switched reluctance motor. IEEE Open J. Ind. Appl. 2024, 5, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimpara, M.L.M.; Reis, R.R.C.; Da Silva, L.E.B.; Pinto, J.O.P.; Fahimi, B. A two-step control approach for torque ripple and vibration reduction in switched reluctance motor drives. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 82106–82118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Faouri, F.S.; Cai, Y.; Fujii, Y.; Chiba, A. Mathematical current derivation for acoustic noise reduction in switched reluctance motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Guo, J.; Mao, S.; Xiao, D.; Zhao, D.; Song, S.; De Doncker, R.W. A composite model predictive control method of SRMs with PWM-based signal for torque ripple suppression. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 2469–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, S.; Kanagaraj, R. Minimizing torque ripple for switched reluctance motor through optimum torque sharing function. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Computing and Communication Technologies (CONECCT), Bangalore, India, 12–14 July 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Masoumi, M.; Bilgin, B. Experimental acoustic noise and sound quality characterization of a switched reluctance motor drive with hysteresis and PWM current control. Machines 2025, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.E.; Zahid, A.; Vaks, N.; Bilgin, B. Switched reluctance motor design for a light sport aircraft application. Machines 2023, 11, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A.; Ravichandran, S.; Indiketiya, T.H.; Sahu, A.K.; Pathirannahalage, S.V.; Yilmaz, B.S.; Howey, B.; Vaks, N.; Abdollahi, M.E.; Bilgin, B. Mechanical design of a switched reluctance motor with small airgap length. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 141108–141123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaabjerg, F.; Kjaer, P.C.; Rasmussen, P.O.; Cossar, C. Improved digital current control methods in switched reluctance motor drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 1999, 14, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Ahn, J.S.; Lee, J. The characteristic analysis of switched reluctance motor considering DC-link voltage ripple on hard and soft chopping modes. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2005, 41, 4096–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, D.F.; Tarvirdilu-Asl, R.; Garcia, C.; Rodriguez, J.; Emadi, A. Vision, challenges, and future trends of model predictive control in switched reluctance motor drives. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 69926–69937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieras, J.F.; Wang, C.; Lai, J.C. Noise of Polyphase Electric Motors; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Masoumi, M.; Selliah, A.; Bilgin, B. Development of an experimental acoustic noise characterization setup for electric motor drive applications. Energies 2024, 17, 5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Center Frequencies and High/Low Frequency Limits for Octave Bands, 1/2- and 1/3-Octave Bands. Available online: https://courses.physics.illinois.edu/phys406/sp2017/Lab_Handouts/Octave_Bands.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

| Parameter | Symbol | Value or Type |

|---|---|---|

| Number of stator poles | 18 | |

| Number of rotor poles | 12 | |

| Number of phases | m | 3 |

| Nominal DC voltage [V] | 450 | |

| Base speed [RPM] | 2600 | |

| Rated average torque [Nm] | 260 | |

| Maximum speed [RPM] | 4000 | |

| Phase resistance [m] | 1 | 73 |

| Rotor inner radius [mm] | 70 | |

| Rotor outer radius [mm] | 96 | |

| Slot inner radius [mm] | 120 | |

| Stator outer radius [mm] | 140 | |

| Air-gap length [mm] | 0.4 | |

| Stack length [mm] | 100 | |

| Electrical steel lamination | − | HIPERCO 50A |

| State | Type | [V] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Active | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | Freewheeling | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | Freewheeling | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | Active | 1 | 1 |

| [RPM] | [rad/s] | [Hz] | [ms] | [ms] | [Hz] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 52.36 | 8.33 | 120 | 10.00 | 100 |

| 1000 | 104.72 | 16.67 | 60 | 5.00 | 200 |

| 1500 | 157.08 | 25.00 | 40 | 3.33 | 300 |

[RPM] | h [−] | [ms] | [µs] | [kHz] | [kHz] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 540 | 20.00 | 18.519 | 54 | 27 |

| 1000 | 270 | 10.00 | 18.519 | 54 | 27 |

| 1500 | 180 | 6.67 | 18.519 | 54 | 27 |

| Mechanical Speed → Control Technique ↓ | 500 RPM () | 1000 RPM () | 1500 RPM () |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyst. control (soft switching) | 84.01 dB | 87.65 dB | 81.60 dB |

| Hyst. control (hard switching) | 88.28 dB | 92.93 dB | 92.46 dB |

| PWM control | 74.13 dB | 77.41 dB | 82.09 dB |

| Model predictive control | 82.39 dB | 82.21 dB | 86.74 dB |

| Control Technique | Mech. Speed | Simulation | Experimental | Absolute Errors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [RPM] | [Nm] | [A] | [Nm] | [A] | [Nm] | [A] | |

| Hysteresis control | 500 | 17.50 | 22.57 | 17.77 | 22.94 | 0.27 | 0.37 |

| (soft switching) | 1000 | 17.04 | 20.84 | 16.94 | 21.03 | 0.10 | 0.19 |

| 1500 | 16.26 | 19.62 | 15.69 | 19.34 | 0.57 | 0.28 | |

| Hysteresis control | 500 | 13.54 | 18.43 | 12.58 | 18.32 | 0.96 | 0.11 |

| (hard switching) | 1000 | 12.54 | 17.43 | 12.72 | 18.58 | 0.17 | 1.15 |

| 1500 | 12.82 | 17.49 | 14.53 | 17.85 | 1.72 | 0.36 | |

| PWM | 500 | 13.82 | 17.92 | 14.96 | 18.53 | 1.15 | 0.61 |

| control | 1000 | 15.10 | 18.08 | 15.03 | 18.54 | 0.07 | 0.46 |

| 1500 | 15.46 | 17.92 | 14.21 | 18.08 | 1.25 | 0.16 | |

| Model predictive | 500 | 12.34 | 17.38 | 11.73 | 17.26 | 0.61 | 0.12 |

| control | 1000 | 13.55 | 17.71 | 11.68 | 16.77 | 1.86 | 0.94 |

| 1500 | 13.19 | 17.25 | 12.00 | 16.90 | 1.19 | 0.35 | |

| Assembly | Vibration Modes and Natural Frequencies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(2,0) [Hz] |

(3,0) [Hz] |

(4,0) [Hz] |

(5,0) [Hz] |

(0,0) [Hz] |

(6,0) [Hz] | |

| Stator core | 562 | 1513 | 2746 | 4157 | 4358 | 5618 |

| Stator + windings | 485 | 1512 | 2787 | 4189 | 4379 | 5653 |

| Stator housing assembly | 1098 | 2405 | 4010 | 5500 | 5090 | 7376 |

| Encapsulated stator housing assembly | 999 | 2432 | 4095 | 5831 | 4870 | 7592 |

| -Octave Bands | Hyst. Control (Soft Switching) | Hyst. Control (Hard Switching) | PWM Control | Model Predictive Control | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

500 RPM |

1000 RPM |

1500 RPM |

500 RPM |

1000 RPM |

1500 RPM |

500 RPM |

1000 RPM |

1500 RPM |

500 RPM |

1000 RPM |

1500 RPM | |

| [Hz] | [dB] | [dB] | [dB] | [dB] | [dB] | [dB] | [dB] | [dB] | [dB] | [dB] | [dB] | [dB] |

| 250 | 25.51 | 24.25 | 30.05 | 24.01 | 27.04 | 33.35 | 23.23 | 21.88 | 31.62 | 22.04 | 24.88 | 31.63 |

| 315 | 45.50 | 28.96 | 35.92 | 44.24 | 28.19 | 40.19 | 42.60 | 29.45 | 40.48 | 42.29 | 27.67 | 38.71 |

| 400 | 35.36 | 38.29 | 38.76 | 34.76 | 39.51 | 40.09 | 33.55 | 39.75 | 39.76 | 32.06 | 41.21 | 38.47 |

| 500 | 42.21 | 37.11 | 37.18 | 41.50 | 42.49 | 42.26 | 40.53 | 38.36 | 36.35 | 37.87 | 38.29 | 37.27 |

| 630 | 66.15 | 69.01 | 53.72 | 65.52 | 68.33 | 59.13 | 66.30 | 67.33 | 52.60 | 65.71 | 69.64 | 52.17 |

| 800 | 50.77 | 42.83 | 67.72 | 48.74 | 49.24 | 67.57 | 47.79 | 43.29 | 66.89 | 46.53 | 41.61 | 66.12 |

| 1000 | 55.02 | 37.15 | 63.38 | 53.31 | 44.77 | 62.63 | 53.89 | 37.32 | 64.46 | 53.33 | 37.43 | 63.97 |

| 1250 | 56.68 | 63.50 | 55.30 | 57.04 | 62.90 | 57.79 | 55.26 | 62.24 | 54.97 | 55.41 | 60.65 | 54.77 |

| 1600 | 56.80 | 47.68 | 52.71 | 60.75 | 56.74 | 56.27 | 56.75 | 48.91 | 53.96 | 60.30 | 47.98 | 53.25 |

| 2000 | 61.29 | 59.51 | 64.21 | 58.67 | 59.99 | 63.44 | 57.48 | 58.90 | 63.91 | 56.46 | 58.12 | 63.23 |

| 2500 | 58.07 | 60.29 | 62.54 | 60.62 | 66.84 | 62.20 | 55.07 | 59.12 | 62.23 | 52.72 | 61.32 | 62.44 |

| 3150 | 55.30 | 53.97 | 52.40 | 63.76 | 61.74 | 56.52 | 50.72 | 54.05 | 52.06 | 51.48 | 59.04 | 51.12 |

| 4000 | 63.61 | 64.25 | 63.48 | 68.33 | 71.57 | 70.83 | 56.78 | 62.36 | 62.27 | 60.27 | 64.10 | 64.26 |

| 5000 | 73.25 | 73.41 | 73.92 | 80.86 | 78.49 | 81.09 | 65.64 | 69.59 | 71.15 | 66.37 | 70.58 | 75.50 |

| 6300 | 58.64 | 61.65 | 61.76 | 65.35 | 69.31 | 68.46 | 51.33 | 53.64 | 56.80 | 56.96 | 58.67 | 61.34 |

| 8000 | 62.83 | 64.06 | 58.16 | 65.68 | 64.49 | 67.48 | 50.56 | 52.92 | 55.46 | 63.22 | 66.87 | 64.46 |

| 10,000 | 47.98 | 49.48 | 54.04 | 55.74 | 58.74 | 59.77 | 39.15 | 43.31 | 46.36 | 46.82 | 49.06 | 54.93 |

| 12,500 | 40.90 | 41.75 | 42.56 | 46.41 | 47.09 | 44.01 | 39.14 | 44.66 | 46.29 | 38.15 | 42.37 | 41.53 |

| 16,000 | 36.87 | 37.34 | 40.05 | 40.28 | 40.86 | 41.51 | 47.46 | 50.71 | 54.41 | 33.31 | 36.52 | 39.83 |

| 20,000 | 40.35 | 40.82 | 43.89 | 47.98 | 47.73 | 48.52 | 37.20 | 40.79 | 42.60 | 37.91 | 41.15 | 44.46 |

| Mechanical Speed → Control Technique ↓ | 500 RPM () | 1000 RPM () | 1500 RPM () |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyst. control (soft switching) | 75.33 | 76.15 | 76.32 |

| Hyst. control (hard switching) | 81.65 | 80.56 | 82.26 |

| PWM control | 70.37 | 73.11 | 74.58 |

| Model predictive control | 71.54 | 75.18 | 77.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Juarez-Leon, F.; Masoumi, M.; Nahid-Mobarakeh, B.; Bilgin, B. Evaluation of the Acoustic Noise Performance of a Switched Reluctance Motor Under Different Current Control Techniques. Acoustics 2025, 7, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics7040077

Juarez-Leon F, Masoumi M, Nahid-Mobarakeh B, Bilgin B. Evaluation of the Acoustic Noise Performance of a Switched Reluctance Motor Under Different Current Control Techniques. Acoustics. 2025; 7(4):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics7040077

Chicago/Turabian StyleJuarez-Leon, Francisco, Moien Masoumi, Babak Nahid-Mobarakeh, and Berker Bilgin. 2025. "Evaluation of the Acoustic Noise Performance of a Switched Reluctance Motor Under Different Current Control Techniques" Acoustics 7, no. 4: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics7040077

APA StyleJuarez-Leon, F., Masoumi, M., Nahid-Mobarakeh, B., & Bilgin, B. (2025). Evaluation of the Acoustic Noise Performance of a Switched Reluctance Motor Under Different Current Control Techniques. Acoustics, 7(4), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics7040077