Historic Approaches to Sonic Encounter at the Berlin Wall Memorial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

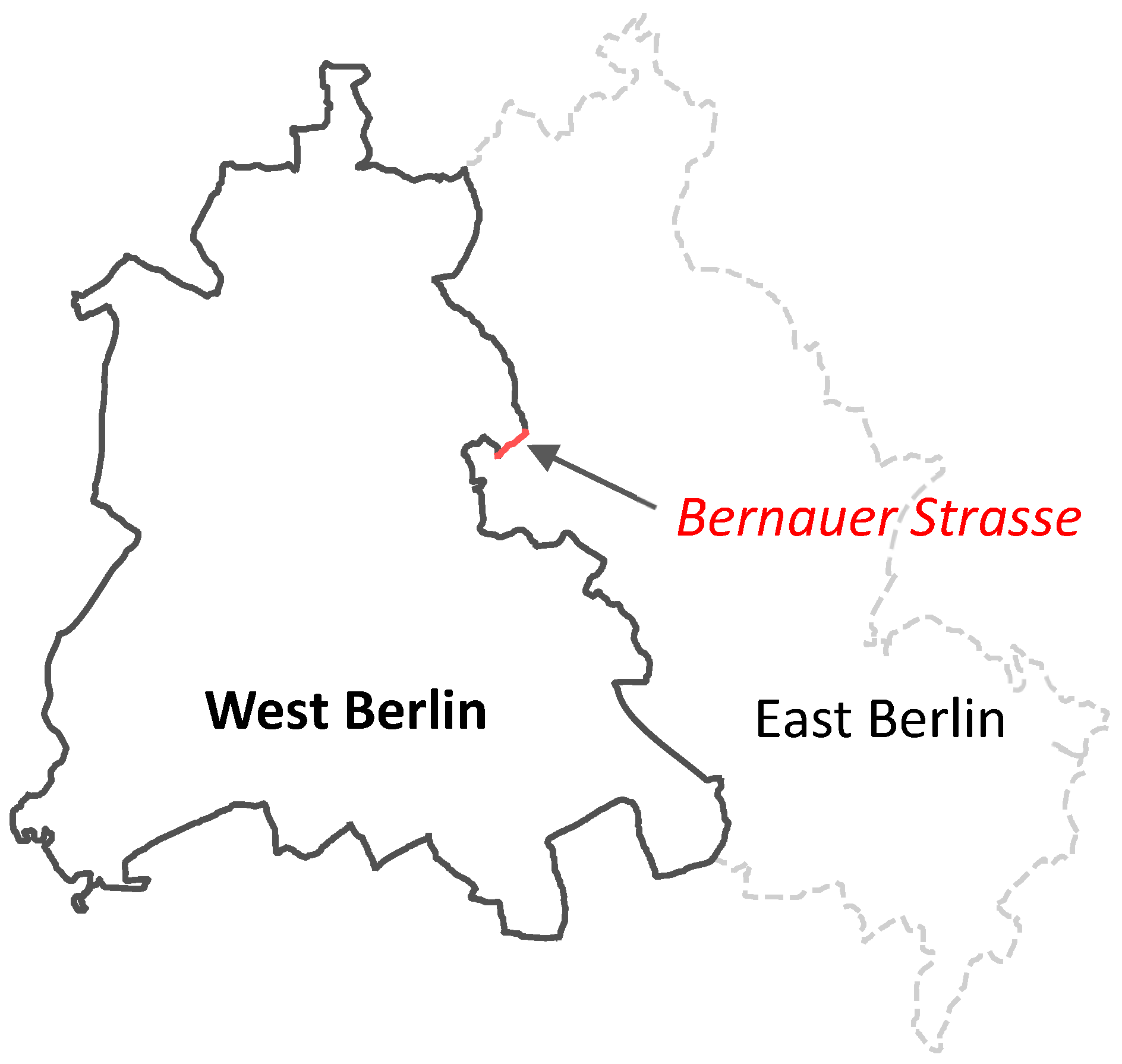

2.1. The Memorial Today

2.2. Sources and Methods of Historic Context Assessment

“Particularly on weekends it was such that the street [Bernauer Straße] was entirely a tourist mile. […] The car horn choruses were awful. People would beep well into the night as a form of protest. For the locals who lived here and for the patients that I dealt with, it was, of course, catastrophic.”…

…“Because of this length of wall, because of this no-man’s-land, the quiet allowed plants as well as animals to develop and settle in the cemetery. […] There was also a nightingale that practically enjoyed total silence on the one side”—Nurse at Lazarus Hospital, lived on Bernauer Straße (Interview with G. Malchow, page 1.f (first paragraph) and 24).

“[Shouts] shattered the quiet that as a general rule prevailed. And when this quiet was interrupted by shouts, warning shots, dogs barking and the like, it was even more unusual”—Resident from eastern side of the Wall (Interview with R. Zausch, page 26).

“[W]e couldn’t see Bernauer Straße. We could only hear it and would … go down to the street to see what was going on. Our police officers were standing down there with pistols drawn to give cover for people who were coming out [of their windows]”—Resident from western side of the Wall) (Interview with K. De, page 18).

- 1961–1962: the initial construction phase, when protests and escape attempts dominated and the initial barbed wire was continually “upgraded” until a West and East Wall enclosed what became known as the death strip;

- 1962–1965: escape attempts continued, protests were common and tourism became prevalent;

- 1965–1975: the sheared-off building facades functioning as the West Wall were replaced by concrete barriers, development on the West rendered the once commercial/residential mix into a purely residential neighborhood, and protest and tourism continued;

- 1975–1989: the “final” version of the Wall was installed, animal life flourished in the cemetery and tourism and protest diminished; and

- 1989–1990: when the Wall “fell” and wall-peckers slowly disintegrated the Wall’s remains for souvenirs day and night.

2.3. Current Context Assessment Approaches

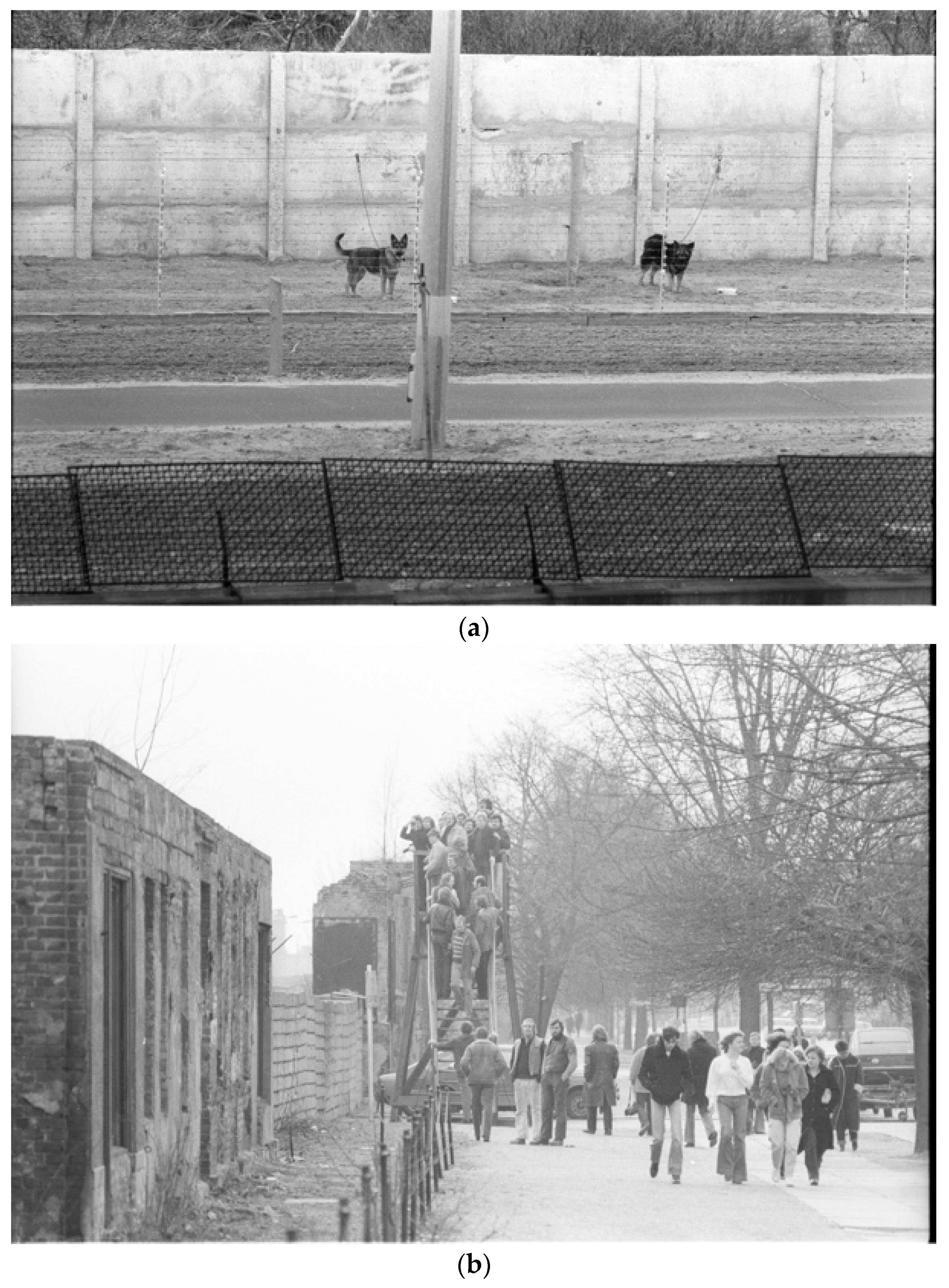

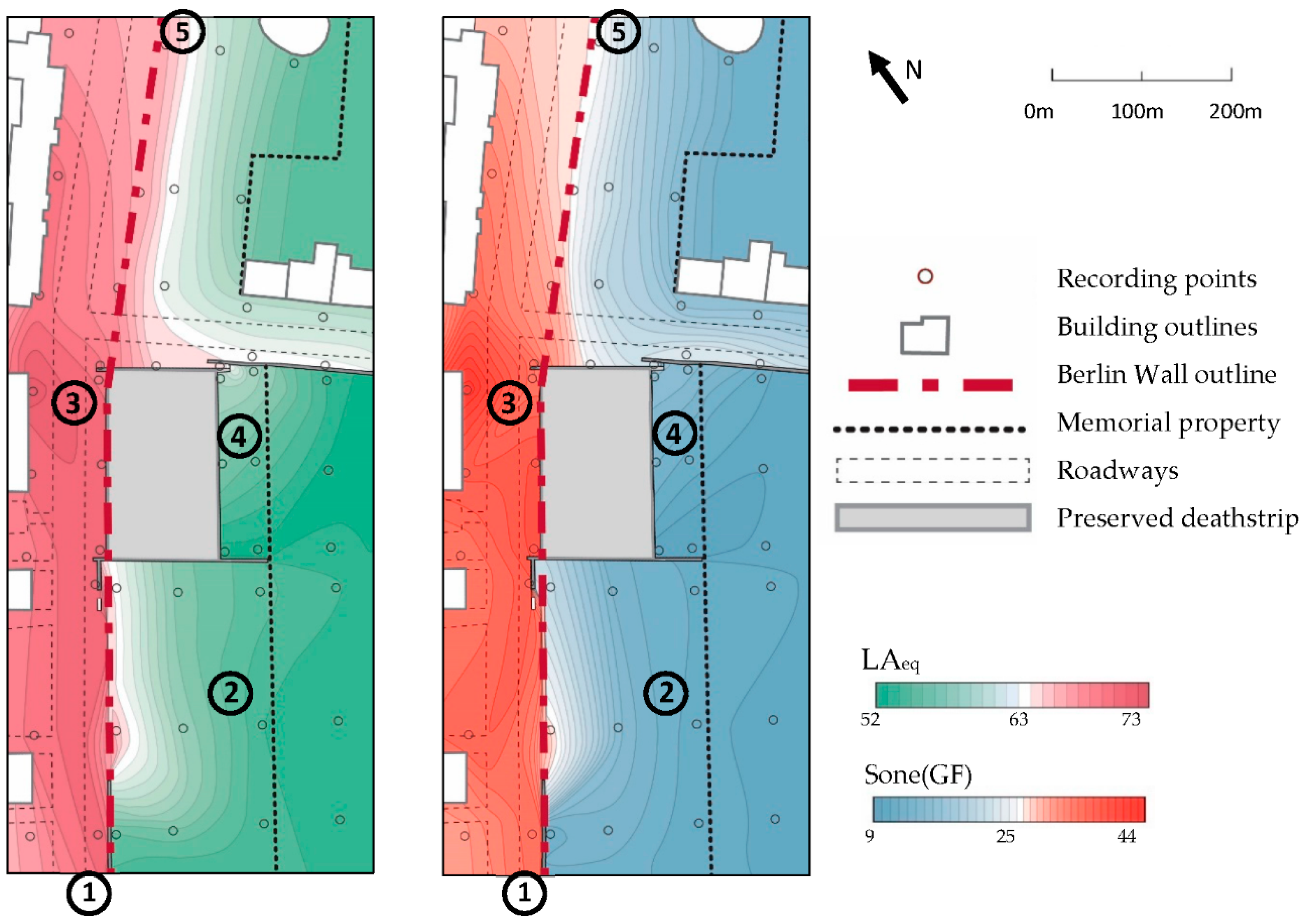

2.3.1. Binaural Recording and Mapping

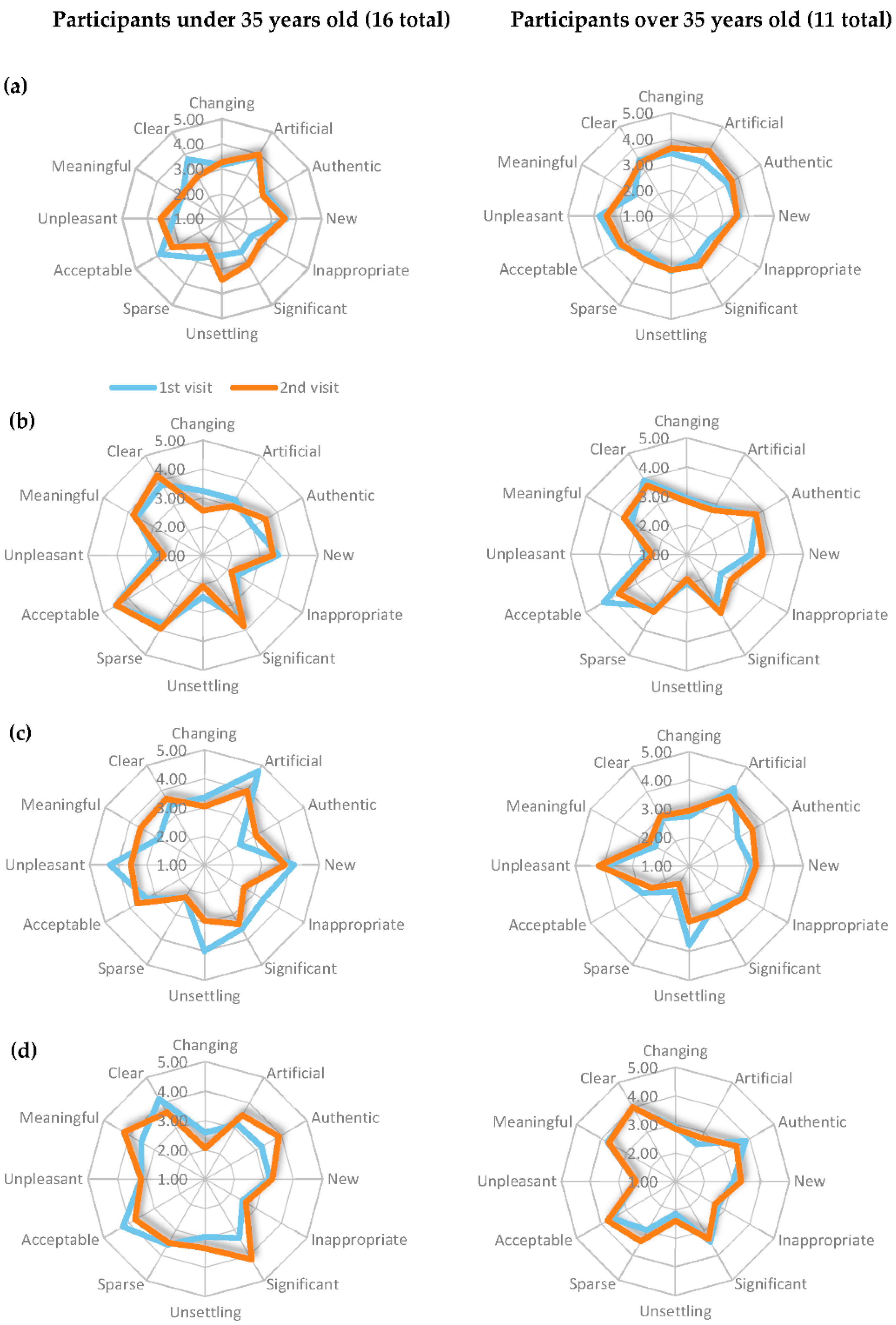

2.3.2. Soundwalks with Custom Surveys

- a.

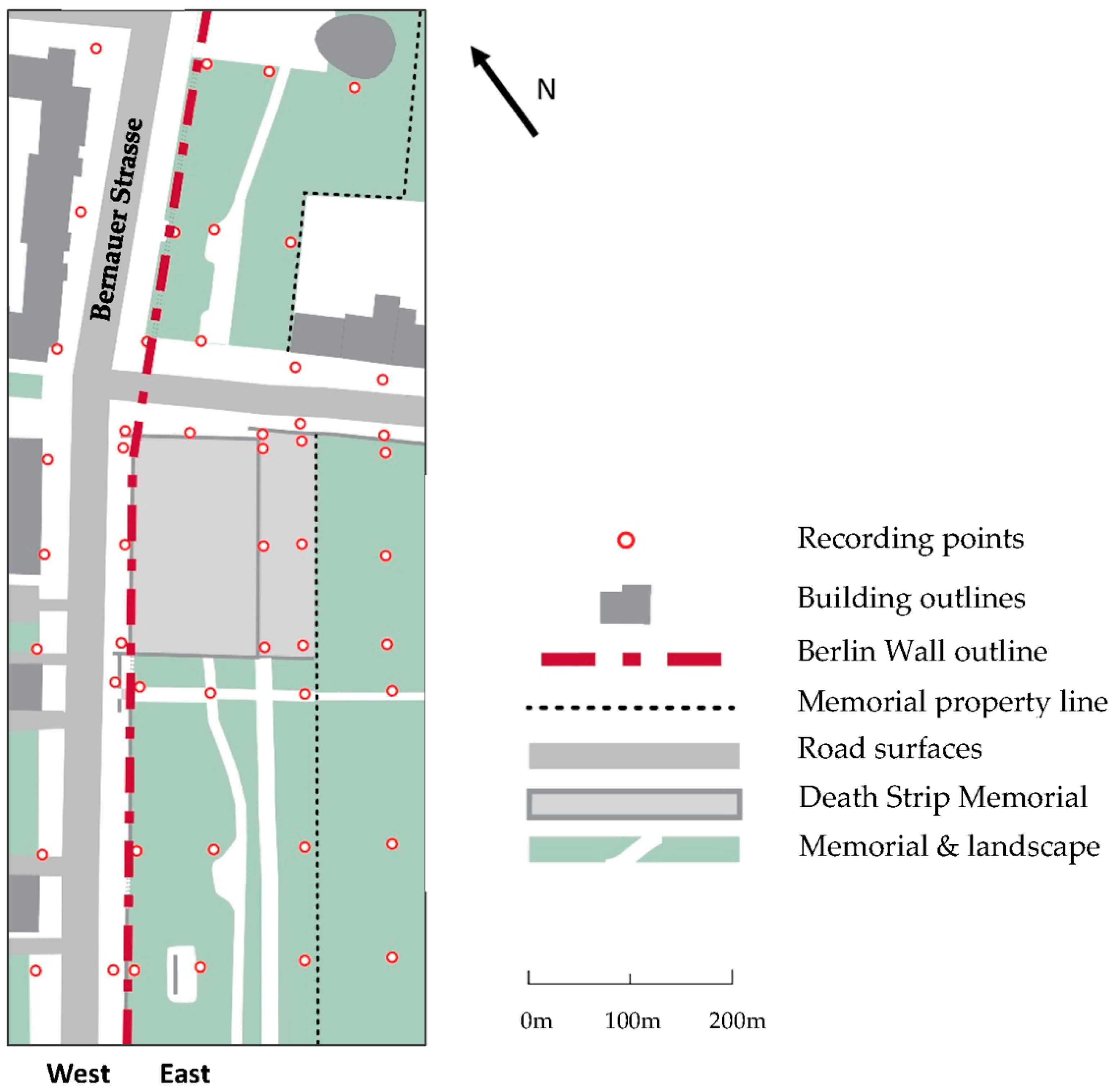

- “Mundt”: Located on the west side of the Wall, today in an open area dominated by traffic noise from the adjacent intersection. Adjacent Wall fragments are not conserved and appear as they looked after the Wallpeckers finished their work in 1990. The Eastern landscape can be seen easily. Historically, this location was a bend in the original Wall where the killing of Ernst Mundt in 1962 (as he tried to escape from the East) became a political flashpoint. It was later a spot where Western residents attempted suicide by crashing their cars into the concrete wall.

- b.

- “Deathstrip”: Located on the East side of the Wall in the midst of the large grassy expanse that dominates the interpreted deathstrip landscape. Generally visually isolated from the West by the original Wall remnants at the street. Historically a part of the original Sophien Parish cemetery that was converted into a denuded area with guard dogs, tripwires, sirens and constant vehicle patrols by the East German guards.

- c.

- “West Wall”: Located on the West, today directly in front of the conserved portion of the concrete West Wall that faces the documentation center on the other side of Bernauer Straße, a major crossroads for tourist circulation and dominated by dense vehicle traffic noise refracting between non-porous surfaces (effectively creating a semi-closed urban canyon). No portion of the East can be seen except the tops of trees and buildings. Historically resembles the Wall as it appeared from 1975 onward. Part of the path along which tourist buses and cars honking in protest would travel while the Wall was in use.

- d.

- “East Wall”: Located on the East, today in the back area of the conserved portion of the Wall, dominated by the sound of crushed stone underfoot and echoes from Bernauer Straße. No part of the Western streetscape can be seen except the tops of buildings; the top of a guard tower is visible within the deathstrip area and the deathstrip itself can be viewed through gaps left in the Eastern Wall. Historically resembles the eastern portion of the Wall as it appeared in 1965 (though the aforementioned gaps are a modern intervention) and sits adjacent to the Sophien Parish cemetery that was also present throughout the Wall’s historic use.

- e.

- “Chapel”: Located on the eastern edge of the Wall next to the grassy expanse of the interpreted deathstrip and facing the newly constructed (2000) Chapel of Reconciliation. The West can easily be seen and heard through a modern “Wall” interpretation. Located within the grounds of the Church of Reconciliation foundations (demolished in 1985), next to buildings where people attempted to escape from their windows in the first year of the Wall’s construction and where building facades functioned as the Wall itself for many years before being replaced with concrete slabs in the 1970s.

3. Results

3.1. Soundscape Mapping

3.2. Soundwalk and Surveys

“The information about the sonic history of the site influences the listening to the actual sounds. The noise today seems indifferent; other than the ‘historical noise’ with a certain intention/meaning.”(Memorial staff)

“There’s a gap between my acoustic imagination (gun shots, church bells, protests…) and the actual sounds I can hear. The combination is interesting.”(Memorial staff)

“The wall is silent; the wall produces silence in passersby. It is a powerful thing to sense the wall in such proximity. It is unsettling that it still shapes the space in such powerful ways.”(visitor)

“[I am] more aware of hum of park--wind in trees, and birds. … I have a very different attention now that I have more narratives about the space.”(visitor)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bruce, N.S.; Davies, W.J. The effects of expectation on the perception of soundscapes. Appl. Acoust. 2014, 85, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Wang, X.L.; Liu, F.; Yao, C.; Deng, Z. Soundscape and its influence on tourist satisfaction. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 38, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 12913-1:2014—Acoustics—Soundscape Part 1: Definition and Conceptual Framework; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 12913-2:2018—Acoustics—Soundscape Part 2: Data Collection and Reporting Requirements; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Truax, B. Sound, listening and place: The aesthetic dilemma. Organ. Sound 2012, 17, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, R.M. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World, 2nd ed.; Destiny Books: Rochester, VT, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, P. Soundscapes in historic settings—A case study from ancient Greece. In Proceedings of the INTER-NOISE 2016—45th International Congress and Exposition on Noise Control Engineering: Towards a Quieter Future, Hamburg, Germany, 21–24 August 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holter, E.; Muth, S.; Schwesinger, S. Sounding out Public Space in Late Republican Rome. In Sound and the Ancient Senses, 1st ed.; Butler, S., Nooter, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Stoever-Ackerman, J. Splicing the Sonic Color-Line. Soc. Text 2010, 28, 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte-Fortkamp, B.; Jordan, P. When soundscape meets architecture. Noise Map. 2016, 3, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klausmeier, A.; Schmidt, L. Wall Remnants—Wall Traces: The Comprehensive Guide to the Berlin Wall, 1st ed.; Westkreuz-Verlag Gmbh: Berlin/Bonn, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gedenkstätte-Berliner-Mauer, Stiftung Berliner Mauer Zieht Positive Bilanz. 2017. Available online: https://www.berliner-mauer-gedenkstaette.de/de/presse-17,250,16.html (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- SenStadtWohn, 06.06 Population Density. 2016. Available online: https://www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de/umwelt/umweltatlas/ekm606.htm (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- Baker, F. The Berlin Wall: production, preservation and consumption of a 20th-century monument. Antiquity 1993, 67, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheyen, D. Commemorating a Vanishing Monument. In United City, Divided Memories? Cold War Legacies in Contemporary Berlin; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2008; pp. 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Gröschner, A.; Messmer, A. Aus Anderer Sicht/The Other View; Hatje Cantz: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, S.S. A scale for the measurement of a psychological magnitude: loudness. Psychol. Rev. 1936, 43, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicker, E.; Fastl, H. Psychoacoustics: Facts and Models, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.; Brown, A.L. Soundscapes and environmental noise management. Noise Control Eng. J. 2010, 58, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.L.; Gjestland, T.; Dubois, D. Acoustic Environments and Soundscapes. In Soundscape and the Built Environment, 1st ed.; Kang, J., Schulte-Fortkamp, B., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Aletta, F. A soundscape approach to exploring design strategies for acoustic comfort in modern public libraries: a case study of the Library of Birmingham. Noise Map. 2016, 3, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielbo, F.L.; Steele, D.; Guastavino, C. Investigating Soundscape Affordances through Activity Appropriateness. In Proceedings of the Meetings on Acoustics (ICA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 2–7 June 2013; Volume 19, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, P. Valuing the soundscape—Integrating heritage concepts in soundscape assessment. In Proceedings of the INTER-NOISE 2017—46th International Congress and Exposition on Noise Control Engineering: Taming Noise and Moving Quiet, Hong Kong, China, 27–30 August 2017; pp. 5694–5702. [Google Scholar]

- Toepoel, V.; Das, M.; Van Soest, A. Design of web questionnaires: The effect of layout in rating scales. J. Off. Stat. 2009, 25, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Murdock, B.B., Jr. The serial position effect of free recall. J. Exp. Psychol. 1962, 64, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botteldooren, D.; Andringa, T.C.; Aspuru, I.; Brown, A.L.; Dubois, D.; Guastavino, C.; Kang, J.; Lavandier, C.; Nilsson, M.E.; Preis, A.; et al. From Sonic Environment to Soundscape. In Soundscape and the Built Environment, 1st ed.; Kang, J., Schulte-Fortkamp, B., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Raimbault, M. Qualitative Judgements of Urban Soundscapes: Questionning Questionnaires and Semantic Scales. Acta Acust.United Acust. 2006, 92, 929–937. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen, K.B.B. Sound propagation over grass covered ground. J. Sound Vib. 1981, 78, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, M.; Horn, H.; Koenig, T.; Stein, M.; Federspiel, A.; Meier, B.; Michel, C.; Strik, W. Sex Differences in Semantic Processing: Event-Related Brain Potentials Distinguish between Lower and Higher Order Semantic Analysis during Word Reading. Cereb. Cortex 2007, 17, 1987–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Fiebig, A. Cognitive Stimulus Integration in the Context of Auditory Sensations and Sound Perceptions. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, M.R. Sound preferences of the dense urban environment: Soundscape of Cairo. Front. Archit. Res. 2014, 3, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassina, L.; Fredianelli, L.; Menichini, I.; Chiari, C.; Licitra, G. Audio-Visual Preferences and Tranquillity Ratings in Urban Areas. Environments 2017, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M. The preference of the various sounds in environment and the discussion about the concept of the soundscape design. J. Acoust. Soc. Jap. 1993, 14, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miller, N. Understanding Soundscapes. Buildings 2013, 3, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carles, J.L.; Barrio, I.L.; de Lucio, J.V. Sound influence on landscape values. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1999, 43, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Chourmouziadou, K.; Sakantamis, K.; Wang, B.; Hao, Y. (Eds) COST Action: TD0804—Soundscape of European Cities and Landscapes; Soundscape-COST: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Filipan, K.; Boes, M.; De Coensel, B.; Lavandier, C.; Delaitre, P.; Domitrovic, H.; Botteldooren, D. The Personal Viewpoint on the Meaning of Tranquility Affects the Appraisal of the Urban Park Soundscape. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Butler, R.; Airey, D. Links between Tourists, Heritage, and Reasons for Visiting Heritage Sites. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Aletta, F.; Gjestland, T.T.; Brown, L.A.; Botteldooren, D.; Schulte-Fortkamp, B.; Lercher, P.; van Jamp, I.; Genuit, K.; Fiebig, A.; et al. Ten questions on the soundscapes of the built environment. Build. Environ. 2016, 108, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Aletta, F. The Impact and Outreach of Soundscape Research. Environments 2018, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Acceptable | Unacceptable |

| Appropriate | Inappropriate |

| Authentic | Altered |

| Clear | Confusing |

| Comfortable | Uncomfortable |

| Constant | Changing |

| Dense | Sparse |

| Meaningful | Meaningless |

| Natural | Artificial |

| Old | New |

| Pleasant | Unpleasant |

| Significant | Insignificant |

| Semantic Scale 1 | Mundt | Deathstrip | West Wall | East Wall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | Changing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Natural | Artificial | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| Altered | Authentic | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| Old | New | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| Appropriate | Inappropriate | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Insignificant | Significant | 2 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Comfortable | Unsettling | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Dense | Sparse | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Unacceptable | Acceptable | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Pleasant | Unpleasant | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Meaningless | Meaningful | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Confusing | Clear | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Female (19 Total) | Male (6) | Other (2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semantic Scale 1 | 1st Visit | 2nd Visit | 1st Visit | 2nd Visit | 1st Visit | 2nd Visit | |

| Constant | Changing | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Natural | Artificial | 10.5% | 17.1% | 4.2% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Altered | Authentic | 23.7% | 18.4% | 4.2% | 0% | 37.5% | 37.5% |

| Old | New | 15.8% | 10.5% | 12.5% | 4.2% | 0% | 0% |

| Appropriate | Inappropriate | 17.1% | 15.8% | 4.2% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Insignificant | Significant | 8.8% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Comfortable | Unsettling | 0% | 0% | 0% | 4.2% | 0% | 0% |

| Dense | Sparse | 2.9% | 0% | 0% | 12.5% | 0% | 0% |

| Unacceptable | Acceptable | 13.2% | 13.2% | 4.2% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Pleasant | Unpleasant | 1.5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Meaningless | Meaningful | 2.9% | 0% | 0% | 4.2% | 0% | 0% |

| Confusing | Clear | 1.5% | 0% | 4.2% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| The Value of at Least Half of Semantic Scales: | Mundt | Deathstrip | West Wall | East Wall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shifted by 25%+ | 14 | 12 | 10 | 12 |

| Shifted by 0–12% | 5 | 7 | 9 | 6 |

| No change | 4 | 1 | 6 | 1 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jordan, P. Historic Approaches to Sonic Encounter at the Berlin Wall Memorial. Acoustics 2019, 1, 517-537. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics1030029

Jordan P. Historic Approaches to Sonic Encounter at the Berlin Wall Memorial. Acoustics. 2019; 1(3):517-537. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics1030029

Chicago/Turabian StyleJordan, Pamela. 2019. "Historic Approaches to Sonic Encounter at the Berlin Wall Memorial" Acoustics 1, no. 3: 517-537. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics1030029

APA StyleJordan, P. (2019). Historic Approaches to Sonic Encounter at the Berlin Wall Memorial. Acoustics, 1(3), 517-537. https://doi.org/10.3390/acoustics1030029