Abstract

After the war, there was a general understanding of reverberation time (RT), including how to measure it and its significance, as well as its link to a state of diffusion. Reverberation refers to a property of late sound; there was an appreciation that early sound must be significant, but in what way? Research had begun in the 1950s using simulation systems in anechoic chambers, with the Haas effect of 1951 being the most prominent result. Thiele’s Deutlichkeit, or early energy fraction, was important from 1953 and indirectly found expression in Beranek’s initial time delay gap (ITDG) from 1962. The 1960s produced a possible explanation for RTs in halls being shorter than calculations predicted, the importance of early sound for the sense of reverberation (EDT), the nature of directional sensitivity, conditions for echo disturbance, and the importance of early lateral reflections. Much of the research in the 1960s laid the foundations for research investigating the relative importance of the various subjective effects for concert hall listening. Important concert halls built during the period include Philharmonic Hall, New York (1962); Fairfield Hall, Croydon, London (1962); the Philharmonie, Berlin (1963); and De Doelen Hall, Rotterdam (1966). The parallel-sided halls of the past were rarely copied, however, due to architectural fashion. These various halls will be discussed as they make a fascinating group.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

A couple of years ago I was asked to summarize the state of acoustic knowledge in the 1960s, at the time when a famous concert hall was being designed. This was the time when I was beginning my life in acoustics and it seemed that others might be interested in what was happening 50 years ago. There is the interesting question: how would you design a concert hall with this limited information?

For more detail on research activity, Cremer and Müller [1] is an extensive resource. For world concert halls, Beranek’s books are comprehensive [2,3].

1.2. Research

Obviously there was less work being conducted in acoustics in the 1950s, though enough to support two journals which still survive: Journal of the Acoustical Society of America (since 1927), and Acustica (since 1951). The Journal of Sound and Vibration followed in 1964. Acustica printed papers in English, French, and German. While the degree of activity in acoustics may have been less, the problems to be resolved were often fundamental.

Sabine’s pioneering work on reverberation time (RT) [4] required various developments to make RT prediction and measurement reliable processes: the ability to plot sound level against time, a catalogue of measured absorption coefficients of common materials, and RT criteria for relevant spaces. By the 1950s, these requirements had been largely satisfied, yet in several concert halls the measured RT was found to be significantly shorter than predicted, most famously in England in 1951 with the case of the Royal Festival Hall, London.

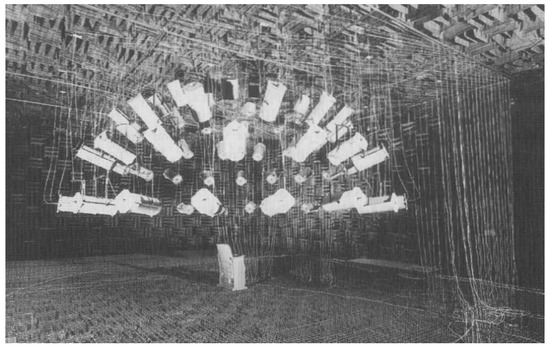

Another realization was that reverberation time alone was not sufficient to fully describe the acoustics of a space, as a space with the optimum RT could still be judged as having disappointing acoustics. It was this that stimulated the main thrust of research begun in the 1950s. The fundamental research tool was a simulation system constructed in an anechoic chamber using an array of loudspeakers around the subject (Figure 1). Reflections were simulated using (magnetic tape) delays and reverberation by a reverberation plate. Key early investigations were conducted in Göttingen, with the first major result being the Haas effect in 1951 [5] (Haas was in fact using a cruder equipment system than the one described above). The Haas effect allows short-delayed reflections louder than the direct sound to assist direct sound for speech without losing localization on the actual sound source, a particularly valuable phenomenon for public address systems.

Figure 1.

Simulation system at Göttingen University around 1960.

One of the goals of research with simulation systems is to establish new measures linked to subjective effects. Starting with the impulse response, there are several possible ways in which our hearing systems might interpret these effects, according to:

- The delay of the first reflection

- The number of reflections within a certain time period

- The order of reflections from different directions

- Measures based on acoustic energy (pressure squared)

Of these, the last has proved most fruitful and was the basis of Thiele’s proposal in 1953 for Deutlichkeit (definition) [6]. With suitable equipment with just a direct and reverberant sound, it is easy to demonstrate the continuum between fully clear (no reverberation) and poor clarity with no direct sound. But what is the role of early reflections, which exist in practice? Thiele proposed that the energy of early reflections should be added to that of the direct sound. Deutlichkeit is the early energy fraction with early defined as the first 50 ms; this time period was based on evidence linked to the Haas effect.

The time 0 ms corresponds here to the arrival of the direct sound at the listener. Boré in 1956 showed that Deutlichkeit was linked to speech intelligibility [7]. In the case of music, Thiele recorded that Deutlichkeit determined the ability to pick out individual musical instruments in orchestral performance.

Traditionally the question of musical clarity had been “dealt with” as part of the optimum reverberation time; if the RT is too long, clarity becomes unacceptable. Thiele’s proposal suggests that clarity is also linked to early sound (direct sound and early reflections) relative to the later reverberant sound level, while with “typical” numbers of early reflections, the RT is probably a sufficient criterion. However, there are many situations where there are insufficient reflecting surfaces close to the source and/or receiver, resulting in inadequate early reflections and poor subjective clarity. This condition of inadequate early reflected energy can occur in larger halls, where in order to satisfy the RT criterion reflecting surfaces become too remote.

Thiele’s result was a symptom of a shift of interest to the early impulse response, though impulse responses themselves are difficult to interpret. Nowadays, as a measure of clarity the early-to-late sound index is generally used, with a time limit of 80 ms for music.

The question of the state of diffusion was another concern in the past. Reverberation theory requires the sound field to be diffuse, leading to a linear decay. The necessary state of diffusion for listeners had not been established, but it was assumed to be desirable for good acoustics. Thiele [6] also looked at the directional distribution at listener positions in auditoria, discovering that it varies considerably. A statement by Thiele clarifies the understanding at the time: “the frequent use of scattering surfaces shows that the resulting increase of directional diffusion is beneficial for the acoustic quality. More directional diffusion is linked to increased fullness of tone” (rough translation).

An interesting casual remark by the Göttingen group was published in 1952 which commented on the subjective effect of a lateral reflection: “… the presence of a secondary loudspeaker creates an apparent enlargement of the spatial extent of the primary source and with a delay of some 10 ms also a certain “reverberance”” (translation from German, Meyer and Schodder [8]). It was to be 15 years before the significance of this effect was proposed quite independently by Marshall!

The early work in Göttingen has been summarized in English by Richardson and Meyer [9]. With hindsight one can see that many of the Göttingen experiments were directed at solving the basic problem: how far can the complex impulse responses found in rooms be simplified without changing audible impression?

Echo disturbance is a potential fault in auditoria, particularly where there are concave surfaces that produce focusing. The conditions for disturbance had been resolved in the 1950s by Nickson et al. [10] and others. A reflection has to arrive later than 50 ms to be heard as an echo, while Dubout [11] proposed the following criterion: an echo is detected if its envelope lies above the envelope of the original sound. Disturbance by a later reflection is, however, much reduced by adding an earlier reflection. Overall disturbance is influenced by the signal (musical tempo), delay, and reverberation time.

1.3. Concert Hall Design before 1960

Before 1914, concert halls were predominantly parallel-sided and conformed to a shoebox shape. A less popular form came from opera houses and theatres, as exemplified by Carnegie Hall in New York (1891). Surface treatment in this period was often highly decorated, beneficial acoustically as scattering. With the arrival of the Modern Movement in architecture, parallel-sided halls with decorated wall surfaces became anathema. Acousticians appear not to have realized the merits of forms from the previous century. In addition, the influence of acousticians on designs was often limited compared with that of the architects.

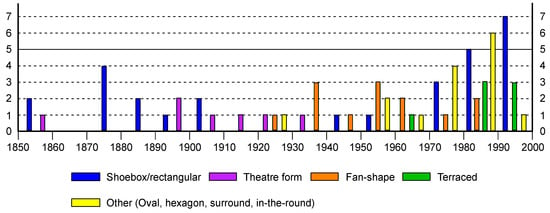

Figure 2 shows the plan forms of 70 important concert halls built between 1850 and 2000. The halls represented are listed in Table A1 and Table A2 in the Appendix. The choice of halls for Figure 2 is far from complete and no doubt somewhat personal. However, the overall conclusions drawn here are unlikely to be influenced by the individual choices made. Many of these halls are to be found in Beranek [3] and Barron [12]. The absence of parallel-sided halls between 1910 and 1960 is clear. A new favorite plan form during this period was the fan-shape, a form that works well for cinemas, which were being built in large numbers at the time.

Figure 2.

Numbers of concert halls of different forms built during decades between 1850 and 2000.

The first large concert hall to be built in Europe after the war was the Royal Festival Hall (RFH) in London in 1951. The choice of plan form has been described by Parkin et al. [13]:

“The main advantage of the fan shape is that the length of the hall is less than that of a rectangular hall seating the same number and of the same width at the orchestra end. The main disadvantage is that the rear wall, balcony front and seat risers are all curved causing a serious risk of echoes. The rectangular hall is almost free from this risk, and in addition has the possible advantage that there is more cross-reflection between parallel walls which may give added ‘fullness’. These two considerations, plus the weight of tradition, led to the adoption of the rectangular shape for the RFH, although of course the arguments are not conclusive. To overcome the main disadvantage of a rectangular hall—its large width at the orchestra end—the seating at the front part of the RFH was made fan-shaped at the orchestra level.”

In the event, the main problem of the Festival Hall has been its short reverberation time, caused by inadequate volume. Other halls from the 1950s, the Alberta Jubilee Halls, Canada, Frederic Mann, Tel Aviv, and the Beethovenhalle, Bonn, were all fan-shaped in plan. The Herkulessaal, Munich, on the other hand, was rectangular. The Beethovenhalle is interesting for its high proportion of scattering surface, responding to the possibility that acoustic excellence of classical shoebox halls might be due to the highly decorated surfaces of 19th century halls.

2. Auditorium Acoustics in the 1960s

2.1. Research in the 1960s

2.1.1. Absorption by Seating and Audience

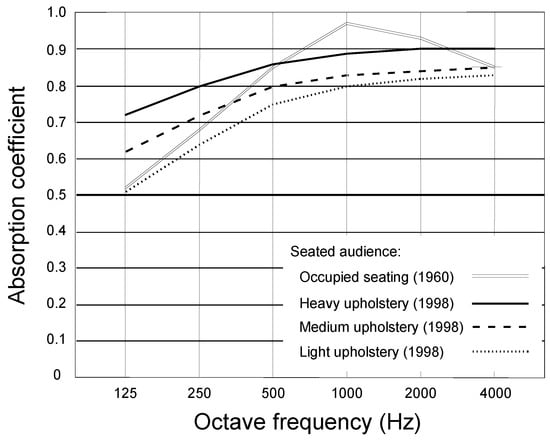

When confronted with the question of how to deal with absorption of seating and audience, Sabine was uncertain whether to treat it on the basis of per seat or by area. With little evidence either way, he chose the former. Beranek observed that in several recent halls (such as the Royal Festival Hall in London, the Jubilee halls in Edmonton and Calgary, and the Beethovenhalle in Bonn) calculations overestimated measured reverberation times; he investigated whether using absorption per area was more reliable. His results were first published in 1960 but were included in his groundbreaking book of 1962 [2]. The area method proved to be more dependable; he also proposed increasing seating area by a 0.5 m wide strip around the edges of a seating block to account for diffraction effects and exposed edges. The main reason for underestimation of seating/audience absorption was the increasing seating standard, or area per seat, in auditoria at the time. Beranek revisited the problem in 1969 [14] and again in 1998 with Hidaka [15]. Figure 3 shows the proposed absorption coefficients for seated audiences in 1960 and 1998; an additional parameter of the degree of upholstery was added in 1998.

Figure 3.

Proposed absorption coefficients for seated audiences by Beranek in 1960 [2] and 1998 [15].

2.1.2. Music, Acoustics, and Architecture

The consultancy firm Bolt, Beranek, and Newman initiated an acoustic survey of world concert halls and opera houses in the late 1950s. On gaining the consultancy of Philharmonic Hall, New York (discussed below), the survey was accelerated and the results published in Beranek’s 1962 book “Music, Acoustics and Architecture”. This book represented several firsts, including investigating 54 concert halls and opera houses, with architectural plans at a uniform scale and photographs of the interiors. Available acoustics (RTs) and physical data were also included. Beranek managed to dispense with several myths, such as that auditorium acoustics improve with age. He conducted a subjective survey using musicians and conductors, correlating the results with the available objective information.

The surprising result which emerged was that reverberation time was not the primary parameter. On the other hand, Beranek proposed that the initial time delay gap (ITDG, the delay of the first reflection relative to the direct sound) was the dominant factor; he linked this quantity to the sense of “intimacy”. A review of this result will be omitted here, since other authors such as Hyde [16] discuss in detail the development and use of the ITDG.

2.1.3. The Sense of Reverberation or Reverberance

The standard method for measuring reverberation time is to measure the slope of the decay between −5 and −35 dB relative to the maximum using an interrupted noise signal. This gives T30; an alternative when the dynamic range is less is T20 (−5 to −25 dB). Schroeder [17] made a very valuable contribution when he demonstrated that reverberant decay could be derived by integrating the squared impulse response in reverse time.

In continuous music, the late sections of decays can seldom be heard. Experiments by Atal, Schroeder, and Sessler [18] showed that listeners used a much shorter time period to establish a sense of reverberation or “reverberance” for continuous music. For simulated decays, a period of 160 ms after the direct sound was found to work best, whereas for decays measured with music recorded in real halls, the decay rate over the first 15 dB was best correlated to reverberance. Schroeder’s new method for measuring reverberation time allowed these short times to be measured. Jordan (1969) [19] summarizing these results, proposed that the slope over the first 10 dB be used as a measure of reverberance, expressed as the early decay time (EDT), so that the numerical value would be identical to the RT for a linear decay.

2.1.4. Requirements for Subjective Diffuseness

One feature of pleasing sound in a space for music is hearing reverberant sound from all directions, but this raises the question of how sensitive we are to directional distribution. This was resolved by Damaske in Göttingen [20], who asked subjects to record from where they heard reverberant sound. A key result was that sound is perceived with almost full apparent coverage with just four loudspeakers arranged orthogonally. Subsequently, with regards to direct sound, Evjen et al. [21] demonstrated that sound from each side is adequate.

2.1.5. Directions of Early Reflections

In 1966/7 two publications pointed to the possible value of early reflections from the side: Marshall [22], who referred to the quality as “spatial responsiveness”, observed that the situation of unmasked lateral reflections was present in some concert halls and not others and that the former were preferred. West [23] reported that there was a good correlation between the ratio of height to width of a hall and Beranek’s subjective ratings [2]; this ratio represents the ratio of travel times for reflections off the ceiling and walls for positions on the center line of a rectangular hall. By 1968, Marshall had already worked out the design implications of providing early lateral reflections [24].

This author began subjective experiments in 1968 in Southampton looking into this phenomenon, which is often now called “spatial impression” [25]. It is the dominant subjective effect of a single lateral reflection, almost independent of delay. The eventual conclusion was that the degree of spatial impression was well correlated with the early lateral energy fraction, with the time limit for early energy being 80 ms [26]. The effect can be measured in a laboratory as an apparent source width (ASW). Others have used the maximum of the interaural cross-correlation function for early sound as a correlate of ASW, though the sound level is also significant [27].

2.1.6. Acoustic Modelling

Acoustic scale modelling was first investigated by Spandöck in the 1930s [28]. By the 1960s, several laboratories were using scale modelling to aid auditorium design [29]. Scale factors 1:10 and 1:20 were commonly used. Because of the fact that frequency transposition is in line with the scale factor, air absorption in ambient conditions is excessive in a scale model. This can be compensated by drying the air in the model or replacing it with a nitrogen atmosphere. Tests can be either objective, i.e., delivering numerical values, or subjective, that is, where anechoic music is “played” through the scale model and assessed subjectively. While the techniques involved in scale modelling were resolved by the 1960s, effective use of scale models in a real design program requires careful planning.

In 1968, the first paper was published proposing computer prediction of sound fields in auditoria [30]. Reflections were assumed to be specular; the analysis compared behavior of a parallel-sided hall with that of a fan-shaped hall. As well as being unable to accommodate scattering (diffusing) room surfaces, the program was unable to include any diffraction effects. Nowadays, the designs of most new auditoria are tested with programs that have been developed to be much closer to actual sound behavior; advances in computers make this a straightforward procedure with personal computers.

2.2. Auditoria from the 1960s

Not many large concert auditoria were built during the 1960s, but three were very significant: Philharmonic Hall, New York (1962), the Philharmonie, Berlin (1963), and De Doelen, Rotterdam (1966). Their designs were very different, as were their acoustic reputations.

The acoustic consultants for Philharmonic Hall—Bolt, Beranek, and Newman—had proposed a rectangular hall; however, changes during the design phase were expected to compromise the acoustics. The consultants’ solution was to introduce an extensive suspended reflector array over the stage and most of the stalls audience [2]. Complaints about the acoustics began soon after the opening of the hall and several attempts were subsequently made to improve listening conditions. In 1976 the auditorium was demolished and replaced by a rectangular hall much closer to the proposal by the original consultants. There is no definitive analysis of what was wrong with the design of the hall when it opened; analyzing the available accounts led this author to the conclusion that it was a case of a subdivided sound field [12]. One of the problems with the original hall, the inability to hear the bass in stalls seating, led to the discovery of the seat dip effect [31].

The lovers of harmony in Berlin were more fortunate. The architect of the hall, Hans Scharoun, was critical of the performer-audience relationship in the classical rectangular hall and proposed placing the stage in the center of the audience area. The acoustic consultant, Lothar Cremer, was worried that several musical instruments were directional, particularly the singing voice; he managed to persuade the architect to move the stage towards one end. A second concern was that large uninterrupted areas of audience limit the number of early reflections; by invoking the vertical dimension and subdividing the audience area into smaller seating blocks, surfaces between the seating blocks became available to provide early sound reflections. In these ways the first vineyard terraced hall was created, which has inspired a whole series of similar designs.

The De Doelen concert hall has the basic plan form of an elongated hexagon, with a secondary hexagon surrounding the stage and front stalls seating. It has a high degree of scattering surface. This combination has resulted in a concert hall with a good acoustic reputation.

3. Auditorium Acoustics after the 1960s

3.1. Research after 1970s

An important conceptual framework for subjective listening to music in concert halls appeared in 1971 in a paper by Hawkes and Douglas [32]. Questionnaires completed at actual concerts were analyzed using a variant of factor analysis. Put simply, the experience is a multi-dimensional one, with most listeners able to identify individual elements, such as clarity.

A technical development from the 1960s proved extremely valuable in elucidating the important subjective dimensions and important objective measures for concert hall listening. This was the dummy head, which had the shape of a typical head with ears reproduced containing microphones. When listening to a binaural recording through such a head, one gets a convincing reproduction of what it sounds like to hear the sound environment at the position of the head during recording. By making recordings in actual concert halls, it is possible to investigate the subjective dimensions and preferences in concert hall listening. Two important studies were undertaken: one in Göttingen and the other in Berlin. The techniques used and results achieved were different, but a consensus view can be gleaned from the two studies [33]. The principal subjective dimensions were clarity, reverberance, envelopment (or spatial impression), and loudness. The last of these was a new result, almost too obvious to mention, but sensitivity of listeners to sound level was found to be much greater than suspected. The objective quantity is known as strength, which is the level due to an omni-directional source on stage relative to the direct sound at 10 m. It was also discovered from the Berlin study that different individuals place different weightings on the individual elements when it comes to overall preference, with in their case some listeners preferring loudness above all else and for some listeners clarity being the over-riding concern.

3.2. Auditoria after the 1960s

Concert hall design in the 1970s continued to be eclectic and design during the whole period from the 1960s to the early 1980s could be referred to as experimental. Three parallel-sided halls are included in Figure 2 from the 1970s (Washington, Minneapolis, and the replacement of the New York Philharmonic). Other plan forms from this period [3] were fan-shaped (Helsinki), elliptical (Christchurch, New Zealand), an elongated hexagon (Sydney), surround sound (Denver), and in-the-round (Utrecht). The logic behind these designs was various: in Helsinki as part of a sequence of fan-shaped halls designed by Alvar Aalto, in Christchurch a hall with large suspended reflectors to provide early lateral reflections and in Sydney responding to constraints imposed by the famous roof shape.

The fan-shaped plan was gaining a reputation for disappointing acoustics but among the other halls some were more successful than others. At the end of the 1980s, there was a major shift back to parallel-sided halls, with several linked to the acoustician Russell Johnson of Artec. The other precedent to emerge has been the terraced hall, liked by many architects because it creates a better sense of the shared experience between performers and audience.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The accounts in Section 1.2, Section 2.1, and Section 3.1 of developments in research are probably well known, with the 1960s being part of an on-going process that relied predominantly on simulation systems. By the early 1980s a series of quantities were available to measure and modelling possibilities available to test out designs. However, translating preferred values of objective measures into a 3-dimensional concert hall design is far from trivial.

In 1966 Marshall was asked to comment on the acoustic suitability of a group of designs for a new concert hall in Christchurch, New Zealand [34]. He quickly realized that there was no rational basis in the literature for the selection of one shape over another. The dominant result at the time due to Sabine specified a particular auditorium volume but is notoriously silent on the effect of room shape. On the other hand, there was a substantial preference in the literature for narrow rectangular designs. But why should this be the case? This dilemma proved to be the background to his theory about the desirability of early lateral reflections, as described above.

Two further issues influencing design require mentioning. The first is the relative status of the architect and the acoustician. Traditionally the architect’s view held sway, yet this was often influenced by the fashion of the time. The acoustics of a concert hall on the other hand relate directly to the purpose of the space and experience has shown that it is often difficult to remedy faults. Architects now pay more attention to their acousticians.

The second issue concerns seat capacity. In England three halls were built in 1951 (London, Bristol, and Manchester), with in each case the client specifying large seat capacities approaching 3000. In each hall the design was compromised by excessive balcony overhangs. A similar trend in audience numbers can be seen in the Appendix for halls in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s compared with the present day. The current norm is not to allow acoustic compromises to be caused by excessive audience capacity.

There are currently still unknowns in auditorium design, in particular relating to the amount of scattering surface to introduce and where. Conditions for performers is another aspect yet to be fully resolved.

To conclude, much of the ground work in terms of understanding the listener experience dates back to the 1960s. However, this has still left a significant time gap before successful implementation (the Christchurch hall being an exception here as the hall was completed only 5 years after its guiding principle was published). It has taken many years to establish what values to aim for with objective measures and what behavior is to be expected in actual auditoria. What we did not know then was what was important and what was not. For instance, was this proposal about the value of early lateral reflections, something that a designer ought to attend to? The subsequent developments in concert hall acoustics are discussed in [12]. Providing acoustic excellence throughout the whole seating area, rather than just a small region of it, remains a very demanding requirement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The list of concert halls represented in Figure 2 is divided into two here. Table A1 contains halls which can be categorized as rectangular, shoe-box-shaped halls. Some are referred to as parallel-sided, in most cases because the ends are not flat and not at right-angles to the walls. In all cases these halls can be considered as descendants of the 19th century rectangular halls.

Table A2 contains halls of all other forms. The listed plan forms will in some cases seem inappropriate to individual readers, but this is unlikely to alter the main conclusions drawn.

Table A1.

Halls derived from the 19th century shoebox halls.

Table A1.

Halls derived from the 19th century shoebox halls.

| Concert Hall | Date | Plan Form | Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool | 1849–1933 | Rectangular | 2100 |

| Mechanics Hall, Worcester, Mass | 1857 | Rectangular | 1280 |

| Grosser Musikvereinssaal, Vienna | 1870 | Rectangular | 1680 |

| Music Hall, Troy, NY | 1875 | Rectangular | 1255 |

| Stadt Casino, Basel | 1876 | Rectangular | 1400 |

| St. Andrew’s Hall, Glasgow | 1877–1962 | Rectangular | 2130 |

| Neues Gewandhaus, Leipzig | 1884–1944 | Rectangular | 1560 |

| Concertgebouw, Amsterdam | 1888 | Rectangular | 2205 |

| Grosser Tonhallesaal, Zurich | 1895 | Rectangular | 1550 |

| Symphony Hall, Boston | 1900 | Rectangular | 2630 |

| Palau de la Musica Catalana, Barcelona | 1908 | Parallel-sided | 1970 |

| Town Hall, Watford, UK | 1940 | Rectangular | 1590 |

| Herkulessaal, Munich | 1953 | Rectangular | 1290 |

| Kennedy Center, Concert Hall, Washington, DC | 1971 | Rectangular | 2450 |

| Orchestra Hall, Minneapolis | 1974 | Rectangular | 2450 |

| Avery Fisher Hall, New York | 1976 | Rectangular | 2740 |

| Alte Oper, Grosser Konzertsaal, Frankfurt | 1981 | Rectangular | 2500 |

| Konzerthaus, Berlin | 1986 | Rectangular | 1600 |

| Dr. Anton Philips Hall, The Hague | 1987 | Rectangular | 1900 |

| McDermott Concert Hall, Dallas | 1989 | Parallel-sided | 2065 |

| Orchard Hall, Tokyo | 1989 | Parallel-sided | 2150 |

| Symphony Hall, Birmingham, UK | 1991 | Parallel-sided | 2210 |

| Seiji Ozawa Hall, Tanglewood, Lenox, Mass. | 1994 | Rectangular | 1180 |

| Concert Hall, Kyoto | 1995 | Rectangular | 1830 |

| Opera City Concert Hall, Tokyo | 1997 | Rectangular | 1630 |

| Winspear Centre for Music, Edmonton | 1997 | Parallel-sided | 1960 |

| Benaroya Hall, Seattle | 1998 | Rectangular | 2500 |

| Culture and Congress Centre, Lucerne | 1998 | Rectangular | 1840 |

Table A2.

Non-rectangular halls.

Table A2.

Non-rectangular halls.

| Concert Hall | Date | Plan Form | Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy of Music, Philadelphia | 1857 | Opera form | 2980 |

| Carnegie Hall, New York | 1891 | Theater form | 2760 |

| Queen’s Hall, London | 1893–1941 | Theater form | 2050 |

| Orchestra Hall, Chicago | 1904 | Theater form | 2580 |

| Usher Hall, Edinburgh | 1914 | Theater form | 2550 |

| Eastman Theatre, Rochester, NY | 1923 | Theater form | 3340 |

| Salle Pleyel, Paris | 1927 | Fan-shape | 2400 |

| Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels | 1929 | ‘Oval’ | 2150 |

| Severance Hall, Cleveland | 1931 | Theater form | 1890 |

| Konserthus, Gothenburg | 1935 | Segmented fan | 1370 |

| Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool | 1939 | Fan-shape | 1970 |

| Kleinhans Music Hall, Buffalo, NY | 1940 | Fan-shape | 2840 |

| Royal Festival Hall, London | 1951 | Wide rectangular | 2900 |

| Colston Hall, Bristol | 1951 | Extended rect’lar | 2020 |

| Alberta Jubilee Halls, Calgary and Edmonton | 1957 | Fan-shape | 2700 |

| Frederic Mann Auditorium, Tel Aviv | 1957 | Fan-shape | 2710 |

| Beethovenhalle, Bonn | 1959 | Fan-shape | 1400 |

| Festspielhaus, Salzburg | 1960 | Fan-shape | 2160 |

| Philharmonic Hall, New York | 1962–1976 | Fan-shape | 2650 |

| Philharmonie, Berlin | 1963 | Terraced | 2340 |

| De Doelen Concert Hall, Rotterdam | 1966 | Elongated hexagon | 2230 |

| Finlandia Concert Hall, Helsinki | 1972 | Fan-shape | 1750 |

| Town Hall, Christchurch, New Zealand | 1972 | Elliptical | 2660 |

| Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House | 1973 | Elongated hexagon | 2700 |

| Boettcher Concert Hall, Denver | 1978 | Surround | 2750 |

| Muziekcentrum Vredenburg, Utrecht | 1979 | In-the-round | 1550 |

| Louise Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco | 1980 | Surround | 2740 |

| Neues Gewandhaus, Leipzig | 1981 | Terraced | 1900 |

| Roy Thomson Hall, Toronto | 1982 | Surround | 2800 |

| Barbican Concert Hall, London | 1982 | Fan-shape | 1920 |

| Symphony Hall, Osaka | 1982 | Wide rectangular | 1700 |

| Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, Baltimore | 1982 | Surround | 2470 |

| St. David’s Hall, Cardiff | 1982 | Terraced | 1950 |

| Philharmonie am Gasteig, Munich | 1985 | Fan-shape | 2490 |

| Suntory Hall, Tokyo | 1986 | Terraced | 2000 |

| Segerstrom Hall, Orange County, California | 1986 | Split fan-shape | 2900 |

| Cultural Centre Concert Hall, Hong Kong | 1989 | Surround | 2020 |

| Royal Concert Hall, Glasgow | 1990 | Surround | 2460 |

| Bridgewater Hall, Manchester, UK | 1996 | ‘Terraced’ | 2360 |

| Waterfront Hall, Belfast | 1997 | Terraced | 2250 |

| Kitara Concert Hall, Sapporo, Japan | 1997 | Terraced | 2010 |

References

- Cremer, L.; Müller, H.A. Principles and Applications of Room Acoustics; Schultz, T.J., Translator; Peninsula Publishing: London, UK, 1982; Volume 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Beranek, L.L. Music, Acoustics and Architecture; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Beranek, L.L. Concert Halls and Opera Houses: Music, Acoustics and Architecture, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sabine, W.C. Collected Papers on Acoustics; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, H. Über den Einfluss eines Einfachechos auf die Hörsamkeit von Sprache. Acustica 1951, 1, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Thiele, R. Richtungsverteilung und Zeitfolge der Schallrückwürfe in Raümen. Acustica 1953, 3, 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kuttruff, H. Room Acoustics, 4th ed.; Spon Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, E.; Schodder, G.R. Über den Einfluss von Schallrückwürfen auf Richtungslocalisation und Lautstärke bei Sprache. Nachr. Akad. Wiss. Gött. Math. Phys. Kl. IIa 1952, 6, 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, E.G.; Meyer, E. Technical Aspects of Sound Vol. III; Elsevier Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Nickson, A.F.B.; Muncey, R.W.; Dubout, P. The acceptability of artificial echoes with reverberant speech and music. Acustica 1954, 4, 447–450. [Google Scholar]

- Dubout, P. Perception of artificial echoes of medium delay. Acustica 1958, 8, 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, M. Auditorium Acoustics and Architectural Design, 2nd ed.; Spon Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Parkin, P.H.; Allen, W.A.; Purkis, H.J.; Scholes, W.E. The acoustics of the Royal Festival Hall, London. Acustica 1953, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beranek, L.L. Audience and chair absorption in large halls, II. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1969, 45, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beranek, L.L.; Hidaka, T. Sound absorption in concert halls by seats, occupied and unoccupied and by the hall’s interior surfaces. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1998, 104, 3169–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, J.R. Discussion of the Relation between Initial Time Delay Gap [ITDG] and Acoustical Intimacy: Documentation of Leo Beranek’s Final Thoughts on the Subject; IOA: Milton Keynes, UK, 2018; Volume 40. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, M.R. New method of measuring reverberation time. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1965, 37, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atal, B.S.; Schroeder, M.R.; Sessler, G.M. Subjective Reverberation Time and Its Relation to Sound Decay; Bell Telephone Laboratories: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, V.L. Acoustical criteria for auditoriums and their relation to model techniques. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1970, 47, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damaske, P. Subjektive Untersuchungen von Schallfeldern. Acustica 1967, 19, 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Evjen, P.; Bradley, J.S.; Norcross, S.G. The effect of late reflections from above and behind on listener envelopment. Appl. Acoust. 2001, 62, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.H. A note on the importance of room cross-section in concert halls. J. Sound Vib. 1967, 5, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.E. Possible subjective significance of the ratio of height to width of concert halls. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1966, 40, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.H. Levels of reflection masking in concert halls. J. Sound Vib. 1968, 7, 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, M. The subjective effects of first reflections in concert halls—The need for lateral reflections. J. Sound Vib. 1971, 15, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, M.; Marshall, A.H. Spatial impression due to early lateral reflections in concert halls: The derivation of a physical measure. J. Sound Vib. 1981, 77, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidaka, T.; Beranek, L.; Okano, T. Interaural cross-correlation, lateral fraction and low- and high- frequency sound levels as measures of acoustical quality in concert halls. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1995, 98, 988–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spandöck, F. Akustische Modellversuche. Ann. Phys. 1934, 20, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, M. Auditorium acoustic modelling now. Appl. Acoust. 1983, 16, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokstad, A.; Strøm, S.; Sørsdal, S. Calculating the acoustical room response by use of a ray tracing technique. J. Sound Vib. 1968, 8, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T.J.; Watters, B.G. Propagation of sound across audience seating. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1964, 36, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, R.J.; Douglas, H. Subjective acoustic experience in concert auditoria. Acustica 1971, 24, 235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, M. Subjective study of British symphony concert halls. Acustica 1988, 66, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A.H.; Barron, M. Spatial responsiveness in concert halls and the origins of spatial impression. Appl. Acoust. 2001, 62, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).