1. Introduction

ADV probes provide the opportunity to measure in situ the three-dimensional flow velocity in liquids with a high temporal resolution (up to 200 Hz). This allows evaluating the velocity fluctuations in terms of the turbulent behavior in the flow. The three-dimensional velocity fluctuations

are described as the deviation of the mean value

. The intensity of turbulence is described by the turbulent kinetic energy

k =

, which consists of the diagonal contributions of the Reynolds stress tensor, e.g., [

1].

Especially in natural surface waters like rivers, channels, lakes, and estuaries, near-bottom suspended solids of different concentrations are common. For instance, in the Ems Estuary in the German Bight, Suspended Solid Concentrations (SSC) were measured up to 300 g/L [

2]. Cellino demonstrated that SSC influence the flow behavior within a stream, in particular the vertical structure of turbulence. It was shown that SSC can lead to turbulence damping and decreasing eddy viscosity [

3].

The common method to describe the interaction between concentration and turbulence is to quantify the turbulent Schmidt-number Sc

with

being the turbulent viscosity and

being the turbulent diffusivity. The physical behavior of both quantities is the same, as the diffusivity of particles increases with turbulence. The turbulent Schmidt-number is often used for calibrating experimental and numerical data. Depending on the type of particles, it is given as Sc

= 0.3–1.5 [

4].

Applying the eddy viscosity hypothesis,

can be formulated by means of the extra diagonals of the Reynolds stress tensor

and the vertical gradient of the mean velocity

in the main stream direction:

Following the same principle, is described by the fluctuations of the concentration c and the vertical gradient of the mean concentration.

In order to investigate the interaction of turbulence and particle concentration, it is necessary to measure the velocity and the concentration fluctuations simultaneously. Further, to detect as many turbulent eddies as possible, the measuring frequency should be as high as possible.

Salehi et al. summarized three methods for measuring the particle concentrations in currents [

5]: (1) the extraction of samples at different positions with a suction device and the external analysis of the samples taken; (2) determination of the particle concentration through scattering and reflection of light (OBS); and (3) the concentration measurement by means of the reflection and scattering of an acoustic signal. The intensity of sound is attenuated by the particles within the measurement volume. Furthermore, the reflected signal is superimposed by noise, which is taken into account by the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR).

As mentioned in Equation (

2), for the investigation of the diffusivity coefficient

, measurements of the concentration fluctuations are necessary. Applying the suction method, for instance, no information about the concentration and velocity fluctuations at the same time and location are obtained. Optical measurement devices provide a wide spectrum of recordable concentrations; however, they are not able to measure the velocity. The investigations of Fugate et al. show higher accuracy for SSC measurements in estuaries when using acoustic devices rather than optical instruments [

6]. Acoustic devices, like ADV probes, are used to measure the three-dimensional flow velocities with a sampling frequency

f up to 200 Hz. Additionally, the SNR is recorded, which is affected by the particle concentration in the measurement volume. If it is possible to find a unique function for the SNR with respect to the concentration, then it is possible to measure velocity, turbulence, and concentration synchronously.

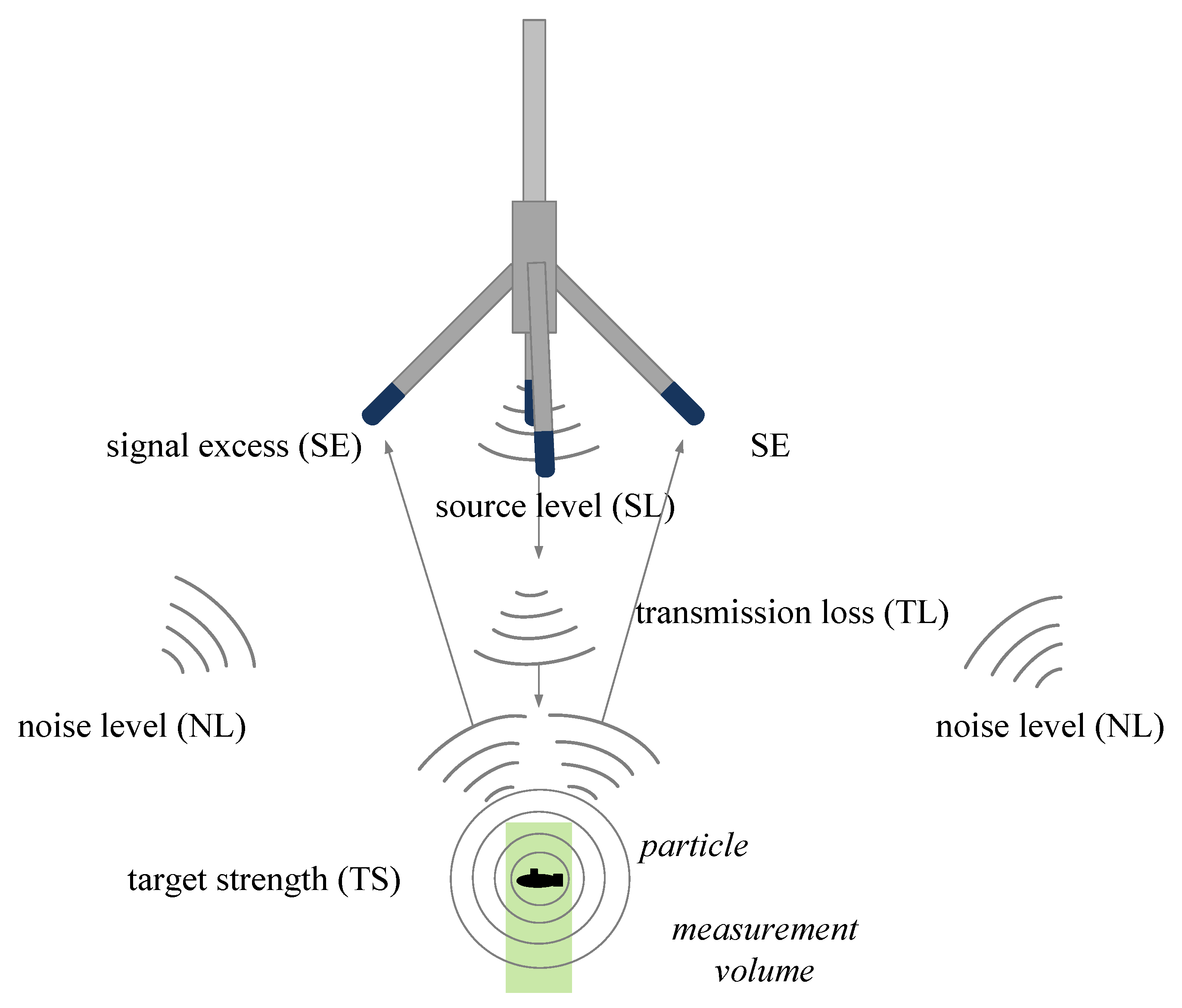

The foundation of the acoustic method is the sonar theory, which was first applied for small particles by Urick in 1948 [

7]. Urick investigated the absorption behavior of kaolin and fine silt while using a quartz crystal to send acoustic pulses. After ADV measurements became a standard technique for velocity measurements, the acoustic scattering theory again was applied for concentration measurements [

8]. Thorne et al. gave a summary of the advantages of acoustic methods for concentration measurements since optical devices reached their working range at this time [

9]. Jay et al. described difficulties when calibrating the SNR for natural rivers, since the reflected signal was strongly dependent on the particle’s material, shape, and size [

10]. Hoitink et al. were able to calibrate the SNR for concentrations up to 1 g/L [

11]. However, neither study, from Jay et al. and Hoitink et al., considered the sound absorption on particles; that is why their methods are only valid up to approximately 1 g/L.

The acoustic method for concentration measurement can be applied at laboratory conditions with a homogeneous particle distribution and known sediment properties. Ha et al. and Salehi et al. presented laboratory experiments for calibrating the reflected signal intensity and the particle concentration [

5,

12]. Nevertheless, they neglected the sound attenuation on particles, although it is a crucial parameter. Decrop et al. presented an experimental setup to measure concentrations up to 10 g/L with an ADV probe while considering sound attenuation on particles. Their measurements were conducted with a measurement frequency of 25 Hz [

13]. To investigate the interaction of turbulent concentration and velocity fluctuations, higher sampling frequencies are required to resolve turbulent flow behavior.

In order to investigate the interaction of turbulence and concentration, different experimental studies were realized. Best et al. conducted a laboratory experiment to measure velocities and concentrations with a Laser Doppler Anemometer (LDA). However, the application of their optical method was restricted to low concentrations [

14]. Cellino used a self-constructed acoustic particle flux profiler for measuring the concentration and velocity with a frequency of 16 Hz [

15]. A part of his research was to investigate the decay of turbulence with increasing suspended sediment concentration in a laboratory flume [

3].

Moreover, Hurther et al. showed the development of an Acoustic Concentration and Velocity Profiler (ACVP), which was able to measure the two-dimensional velocity field and the concentration over a vertical profile of 25 cm [

16]. This device was applied by Revil-Baudard et al. for laboratory experiments on investigations of sheet-flow processes [

17]. They reported about maximum concentration measurement frequencies of 4.9 Hz.

The necessity of simultaneously measuring flow velocity and concentration is presented by means of the Ems Estuary (Germany, North Sea) as an example. In the Ems Estuary, simultaneous measurements of flow velocity and concentration are needed in order to describe the dynamics of fluid mud layers. Fluid mud is a high concentrated mud suspension, which has huge impacts on the maintenance of rivers and estuaries, since navigation can be impeded [

18]. Recently, Becker et al. showed concentration and velocity measurements of the fluid mud layers in the Ems Estuary and highlighted the unsteady and complex behavior of the mud layers with tide. Within this measurement campaign, velocity and concentration were measured by different devices. Furthermore, no turbulence measurements were presented [

19]. Having a measurement device that would be able to measure velocity, concentration, and turbulence simultaneously, the unsteady dynamics of such fluid mud layers could be investigated in more detail.

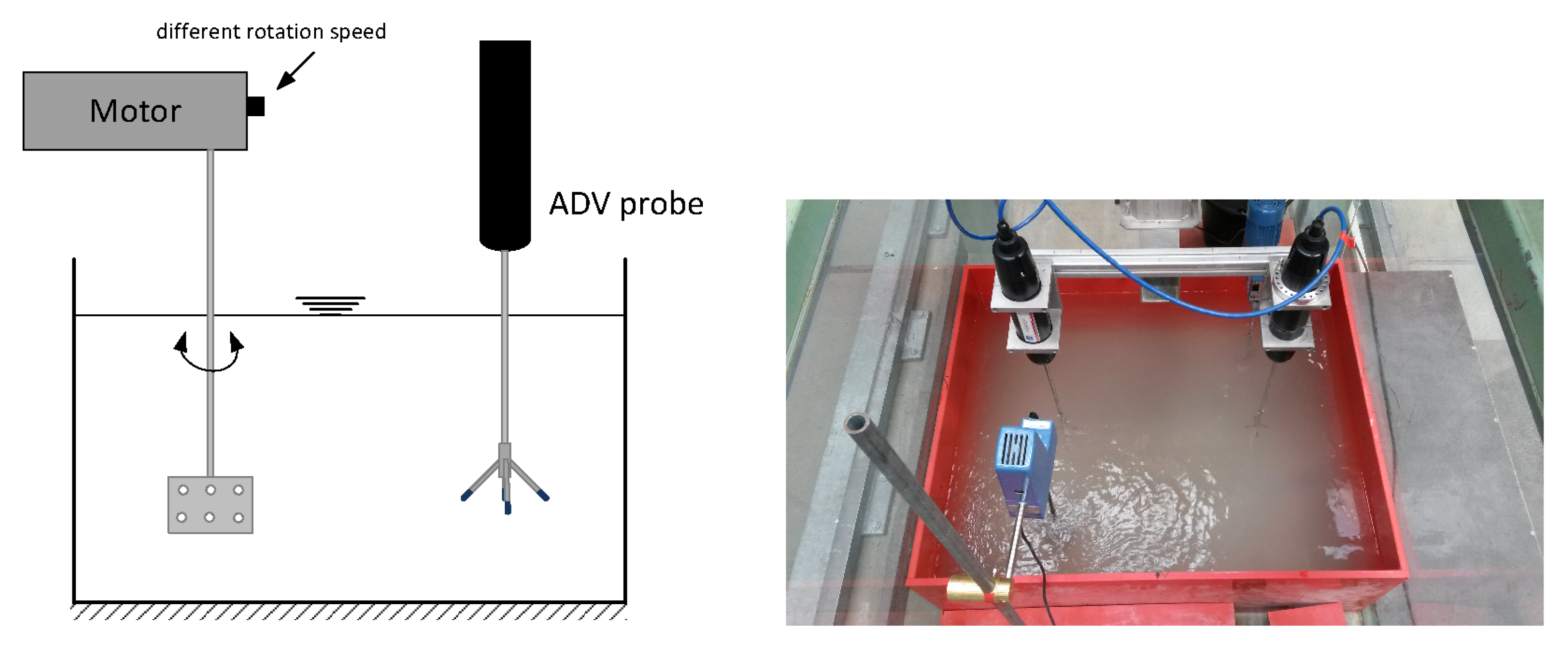

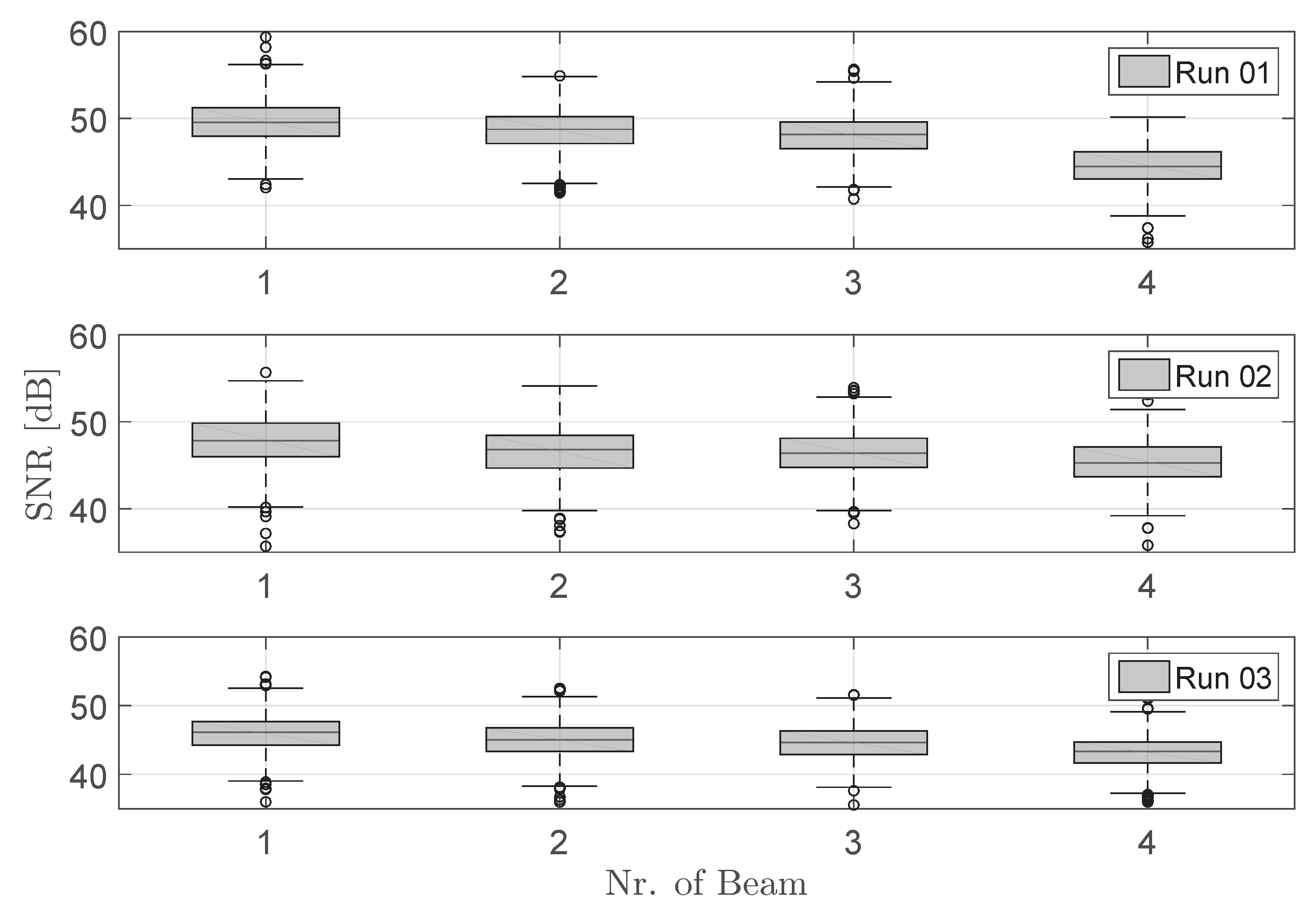

With developing measuring techniques, more accurate turbulence results are expected when using measurement devices with sampling frequencies as high as possible. In this case, small eddies are able to be resolved, which could not be recognized from the measurement device in former studies. Therefore, a Vectrino Profiler (Nortek, Norway) was used with a sampling frequency of 100 Hz. The Nortek Vectrino Profiler was launched in 2010 and consists of a single central transceiver and four passive receivers at an angle of 30

towards the transceiver. A detailed description of the probe was given by Craig et al. and by Thomas et al. [

20,

21].

Within this paper, a method is presented to model the concentration of different suspended materials by means of the SNR with a modern ADV probe (Vectrino Profiler). The acoustic model is based on the well-known sonar theory approach, and it is applied for artificial and natural river sediments. The authors show how sound attenuation is considered in water and on sediment particles within the sonar theory-based model. In experimental studies for cohesive sediment dynamics, quartz powder, metakaolin, and Chinafill are often used [

13,

22,

23]. Therefore, the following artificial sediments were investigated: quartz powder, bentonite, metakaolin, and Chinafill. Afterwards, the results were compared with those of natural sediments from the Ems Estuary on the German Coast, Lake Altmühl, and Lake Eixendorf, both located in Bavaria, Germany. The experimental setup and the proceeding measurements are presented. Furthermore, the authors describe the analysis of the results of different sediments in order to specify the model’s applicability in nature. Furthermore, it is shown that concentrations can be measured up to 50 g/L depending on the type of sediment.

This paper describes a method for simultaneously measuring velocity, turbulence, and concentration, which can be applied in laboratory investigations, as well as in rivers, estuaries, or lakes. The characteristics of the method are presented in detail, and indications are given for practical use in nature. The results of this study provide a contribution for further investigations of turbulence and diffusivity equally in the laboratory and for use in nature.

4. Modeling the Signal-to-Noise Ratio

In this section, we describe the methodology of fitting the sonar equation parameters (Equation (

13)) into the measurements. Doing so, the influence of

is considered. Furthermore, we show how the sonar model is applied to compute the concentration by means of the SNR. In the end, we evaluate and compare the results of different kinds of sediment.

4.1. Application of the Sonar Equation

When rearranging Equation (

13), the SNR is described as:

with the three unknown parameters:

,

=

·

·

C and

.

is interpreted as an empirical correction factor of

.

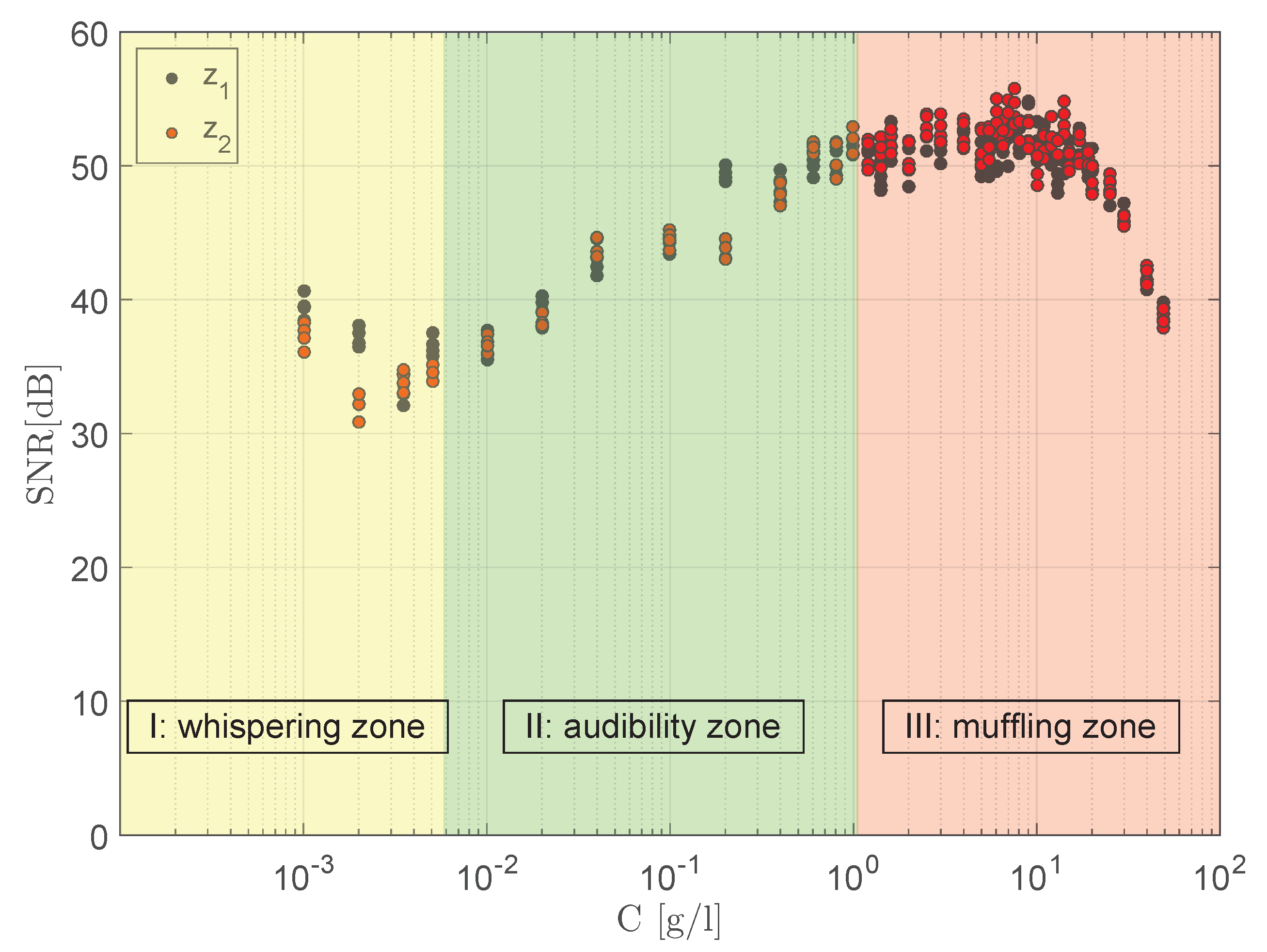

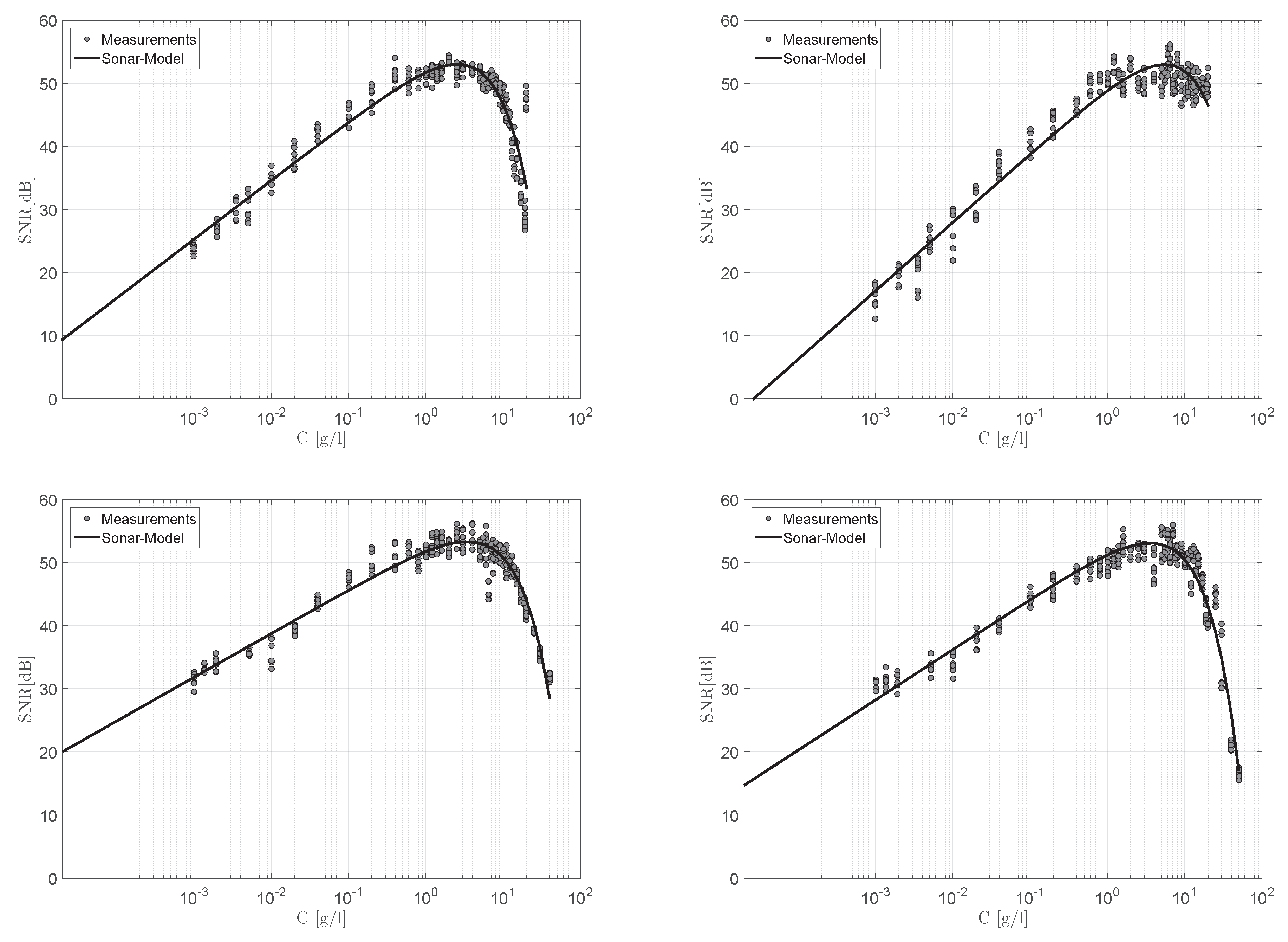

Figure 6 describes the experimental data in comparison to the parametrized sonar function, which is based on Equation (

14). The parameterization of the sonar equation was done with a non-linear least-squares method in the MATLAB

® Curve-Fitting-Tool. It can be seen that the fit function and the measurements are in good agreement. The unknown parameters were found as

= 1.712,

= 4.34, and

= 42.08 dB. We mention that the analytical solution of the Urick-coefficient gave

= 1.727 m

/kg, which deviated in comparison to

=

·

= 7.43 m

/kg. Furthermore, we mention that

is a transformation coefficient of the SNR (see Equation (

13)), which is expected to be close to 1.

When considering the region of high concentrations, the sonar model describes a flattening followed by a decrease of SNR. This behavior is explained by the absorption coefficient in the sonar equation. Even if the influence of remains small in low concentrations, the more particles are in the flow, the higher is the scattering cross-section , which increases the influence of . At a certain concentration, the influence of becomes dominant and leads to a signal damping, resulting eventually in a decrease of the SNR function. Especially, SNR measurements at higher concentrations depict this effect. A sudden decrease of SNR data was regarded for all tested sediments. The “turning point” of SNR differed with the type of sediment, thus it was expected to be material dependent.

4.2. Evaluation of the Sonar Model for Different Sediments

Next, with respect to quartz powder, we conducted measurements of three other artificial sediments, namely bentonite, metakaolin, and Chinafill. All artificial sediments were used as dry powders so that no drying or sediment preparation was necessary. In order to testify to our methodology for natural sediments, we repeated the measurements for coastal sediments from the Ems Estuary (North Sea, Germany) and for freshwater sediments from Lake Altmühl and Lake Eixendorf (Bavaria, Germany). Before using the natural sediments, they needed to be dried, crushed, and sieved (<25 mm) in order to gain the necessary powder.

Dry densities of the sediments were measured with a gas pycnometer (Pycnomatic ATC, Porotec), and mean particle diameters were calculated from grain size distributions measured with a particle sizer (partica LA-950, Horiba). A list of the resulting material constants

,

, and

A is given in

Table 2.

After repeating the calibration experiment for different sediments, the sonar model was fitted to the measurements. The results for the artificial sediments (quartz powder, bentonite, metakaolin, and Chinafill) are plotted in

Figure 7. It can be seen that the sonar model was capable of reproducing the experimental datasets.

In the case of artificial sediments, it is recognizable that there was some deviation between the model and the experimental data in the log-linear regime (II: audibility zone). However, with increasing concentration, the deviations become smaller. When the concentration was sufficiently high, a decrease of the SNR was observed. The conditions to pass from increasing to decreasing SNR response (III: muffling zone) differed with the type of sediment.

In comparison to the artificial sediments, the natural sediments from Lake Eixendorf, Lake Altmühl, and the Ems Estuary are presented in

Figure 8. The resulting fit parameters are summarized in

Table 3 for all measurements. Additionally,

is given as the square of the correlation between the fitted and the measured values.

Even for natural sediments where the composition of sediment is far more complex compared to artificial sediments, our sonar model was able to reproduce the experimental data. Furthermore, it seems that natural sediments rather follow a log-linear approach in the low concentration regime (II: audibility zone) than artificial sediments. For natural sediments, the slope of the modeling results in the log-linear regime does not differ as much as for the artificial sediments. In the opinion of the authors, this effect is not surprising since natural sediments likely consist of similar sediment partitions.

For natural sediments, the vertices of the modeled SNR were located very close to each other, whereas the variation was greater for artificial sediments. Out of this, we conclude that there exists a sediment- and device-specific critical concentration, which separates the increasing and decreasing SNR response.

5. Discussion

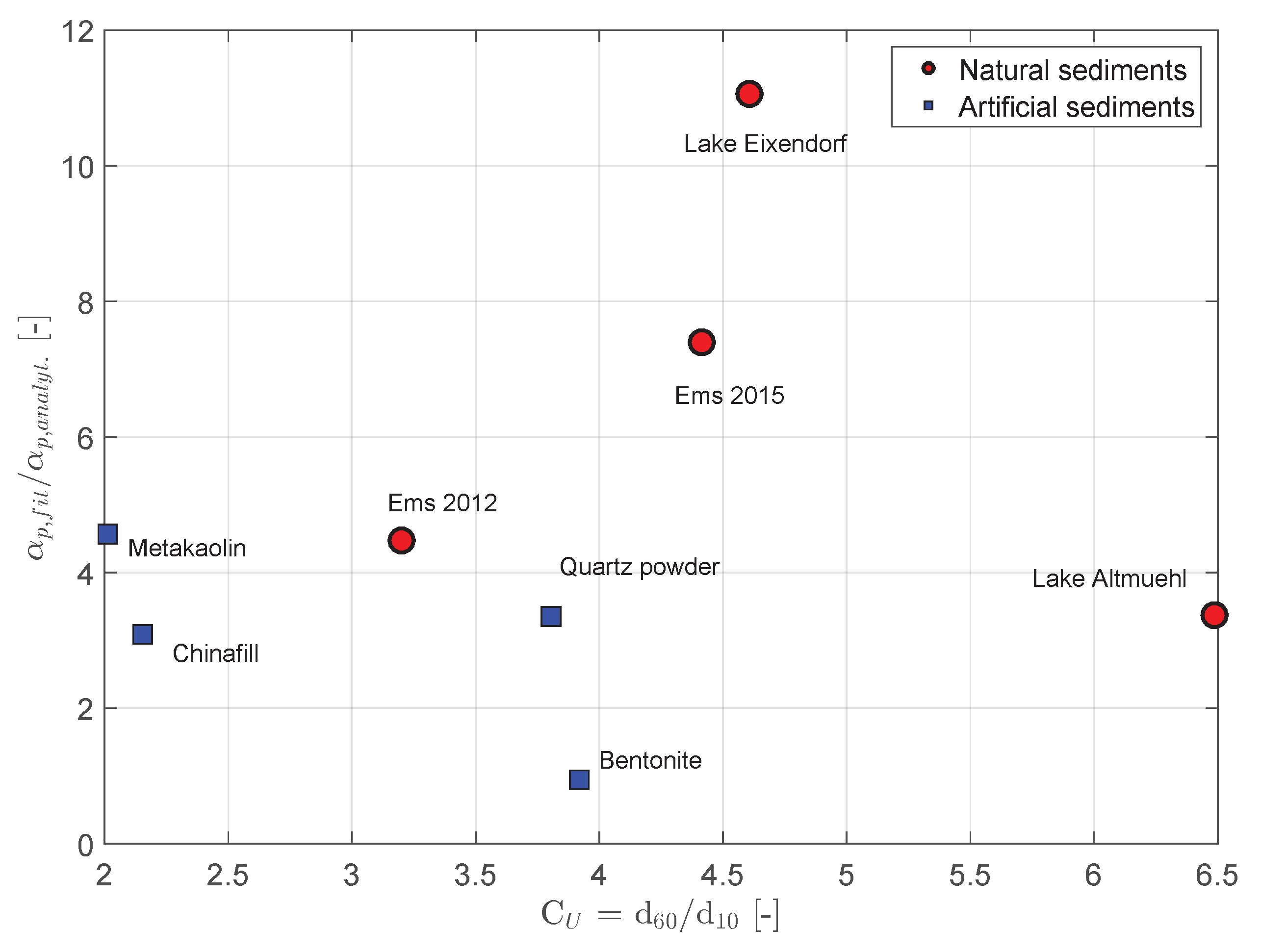

We analyzed the fit parameters

and

and separated the data into artificial sediments (quartz powder, bentonite, metakaolin, and Chinafill) and natural sediments (Ems Estuary, Lake Eixendorf, and Lake Altmühl). Knowing that the mentioned artificial sediments are natural materials, but artificially processed, we use this terminus to distinguish between the sediments extracted from nature. When reading the fit parameters in

Table 3, differences between

and

can be observed. Furthermore, it can be seen that

and

can be separated into artificial and natural sediments. This is shown in

Figure 9 for

and in

Figure 10 for

.

is described through

/

, which is the coefficient of the fitted and the analytically-calculated particle absorption coefficient. A value close to one would imply perfect agreement between the modeled sound absorption on particles and the value based on Urick’s formula in Equation (

12).

Artificially-processed sediments are characterized by a very homogeneous grain size distribution, which is not or to a negligible extent contaminated by other sediments or particle diameters. The grading curve therefore is steeper than for sediments extracted from nature. The uniformity coefficient

=

/

is a dimensionless number to describe the uniformity of a sediment sample. The diameters

and

correspond to 60% and 10% sieve passage, respectively. The sediment samples’ uniformity coefficients

are shown in

Table 2. The grading curves of the artificial sediments result in lower

-values than for natural sediments. The formula of Urick (Equation (

12)), which is implemented in the model, is based on the assumption of homogeneous particle diameters [

7]. In Salehi and Strom, it is mentioned that the particle size distribution also affects

[

5]. In the case of ideal sediment, where all particles have the same size,

would be equal to one. This was not the case, no matter which sediment we used. However, in

Figure 9, it is shown that

/

is lower when using artificial sediments with lower

values. However, as the data for “Ems 2012” show,

is not the only parameter that leads to a decrease of

/

. “Ems 2012” with

= 3.2 results in

/

= 4.47, which is greater than the values of quartz powder and bentonite.

Figure 10 presents the fit parameter

with respect to

. Our results show that

is not only a device-specific parameter, which can be kept as constant for every material. We conclude that it is rather a combined device- and sediment-specific parameter. The data for

again can be separated into artificial and natural sediments and were in the range of

= 42–58 dB for quartz powder, bentonite, Chinafill, and metakaolin. On the contrary,

data for natural sediments were in the range of

= 6–39 dB.

To summarize, our results show that the sonar model can be applied for different sediments without losing its qualitative behavior. We also showed that the model parameters clearly indicate the variation of sediment type. It was shown that the sediment absorption coefficients and not only rely on the sediment diameter, but also on the grain size distribution.

Practical Use and Reliability

In order to assess the practical use, applicability, and reliability of measurements in rivers and estuaries, for instance, we highlight some main characteristics of the method.

Due to the model’s dependence on the particle grain size distribution, the user in the field would need to specify the characteristic sediment that occurs at the measurement location. When Urick’s sound absorption coefficient is used, the mean particle radius and the solid density are needed.

Next, with respect to the sediment-specific parameters, knowledge about the measurement device (here: ADV) is necessary. In general, the sonar model can be also applied for ADCP measurements (e.g., [

11,

27]), though within this study, we only discuss ADV measurements. The ADV probe (Nortek, Vectrino Profiler) that was used has a dynamic range of 60 dB. In comparison, the Vectrino+ (Nortek) has a dynamic range of 25 dB. Both probes have an emitter frequency of 10 MHz. When repeating our measurements with the Vectrino+ probe, we could not find any trend between the SNR and the concentration. Therefore, it can be concluded that a certain dynamic range is of importance to resolve the SNR response with respect to the concentration. Furthermore, it is mentioned that the presented parameters are only valid for the Vectrino Profiler with a dynamic range of 60 dB.

Following the SNR function to concentrations lower than 0.1 mg/L, one will perceive that in this case, Equation (

14) predicts negative SNR values. In particular for

C = 3 × 10

g/L, the function crosses the axis of ordinate at SNR = −10 dB. Following the principles of the sonar theory, the SNR has to be positive for particle detection [

25]. Negative values of the SNR would imply that noise is more dominant compared to the particle backscatter signal. Thus, the region of negative SNR values should be neglected for the interpretation of the model function based on sonar theory. Additionally, it can be observed that the experimental SNR data seem to reach a minimum threshold value for concentrations close to zero. This is explained by the SNR definition, which is implemented in the software of the measuring device. Within the ADV probe, the SNR is calculated by the difference of the backscatter signal intensity, which is here called Amp

(dB), and the noise intensity, Amp

(dB):

Each of the two intensities is calculated by the received counts as:

with

counts = 8000 for the used ADV probe [

28]. This formulation leads to a minimum intensity

Amp = −78.062 dB for no detected counts and to a maximum intensity

Amp = 0 dB in the case of reaching the maximum counts. When inserting Equation (

16) into Equation (

15), the SNR is written as:

where

counts includes the counts related to particle backscattering

counts, as well as the noise

counts. In the case of no backscatter intensity (absolutely no scattering particles in the measurement volume), the minimum SNR would be SNR

= 0 dB and fully independent of noise intensity. Indeed, this is a theoretical threshold, because there are always some scattering particles in the measurement volume. Nevertheless, there is a minimum threshold value for the SNR, which cannot be reproduced by the log-linear sonar model.

Assuming well-mixed conditions in the experimental tank, depth and bottom material are not expected to influence the SNR. As the name signal-to-noise ratio says, it describes the sound intensity of the ratio of the received signal and the background noise. In practice, just before measuring, the ADV probe records the noise intensity. Later during the active measurements, this intensity is subtracted from the absolute received signal (amplitude). Of course, depth and bottom material can influence the intensity of noise. However, the SNR is not influenced by this. This makes the SNR a reliable and universal measure for different environments. However, it has to be noted that the device’s technique to determine the SNR is only valid for steady noise intensity. When conducting long-term measurements with frequent changes of noise (ships, wind, etc.) during the data acquisition, the SNR will be falsified.

In our experiments, we tried to avoid flocculation of particles while the suspension was well mixed. In nature, especially in estuaries, various floc populations are observed, e.g., [

29]. Sound attenuation on flocs is expected to be different than on single primary particles. Flocs are a connection of solids and organic substances, which vary in size, density, and elasticity. In order to calibrate the probe for flocculated suspensions, advanced experimental setups are needed where flocs will not be destroyed during the experiment.

Summing up, the sonar model is able to reproduce the experimental data for a number of different sediments. It shows the log-linear increase of SNR with concentration, as well as the vertex behavior and the decrease of SNR for higher concentrations. This particular behavior of the SNR (increase and decrease) expects attention and special treatment when applying such a model for concentration measurements in nature. One SNR value can be assigned to two concentrations, which is a disadvantage of the model and which has to be taken into account. It reduces the measurement range of this method either to the low concentration regime (positive slope of SNR) or to the high concentration regime (negative slope of SNR). While only using the ADV probe for concentration measurements, the user will not be able to assess the appropriate concentration. Especially in nature, the usage of a second concentration measurement device (e.g., OBS, LISST, tuning fork, etc.) would be necessary to specify the concentration regime [

6,

11,

30]. Then, it is possible to utilize an ADV to measure the velocity, the turbulence, and the concentration simultaneously.