A Combined Experimental and Analytical Analysis of the Prediction of the Bonding Strength in Corroded Reinforced Concrete Through Half-Cell Potential Measurements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Preparation of Concrete Specimens

2.2. Accelerated Corrosion and Steel Mass Loss Measurement

2.3. Half-Cell Potential Measurements

2.4. Pull-Out Test and Bonding Strength Evaluation

3. Numerical Simulation

3.1. Principle and Physics

3.2. Model Geometry and Input Parameters

3.3. Half-Cell Potential and Steel Mass Loss

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Corrosion and Bonding Strength

4.2. HCP and Bonding Strength

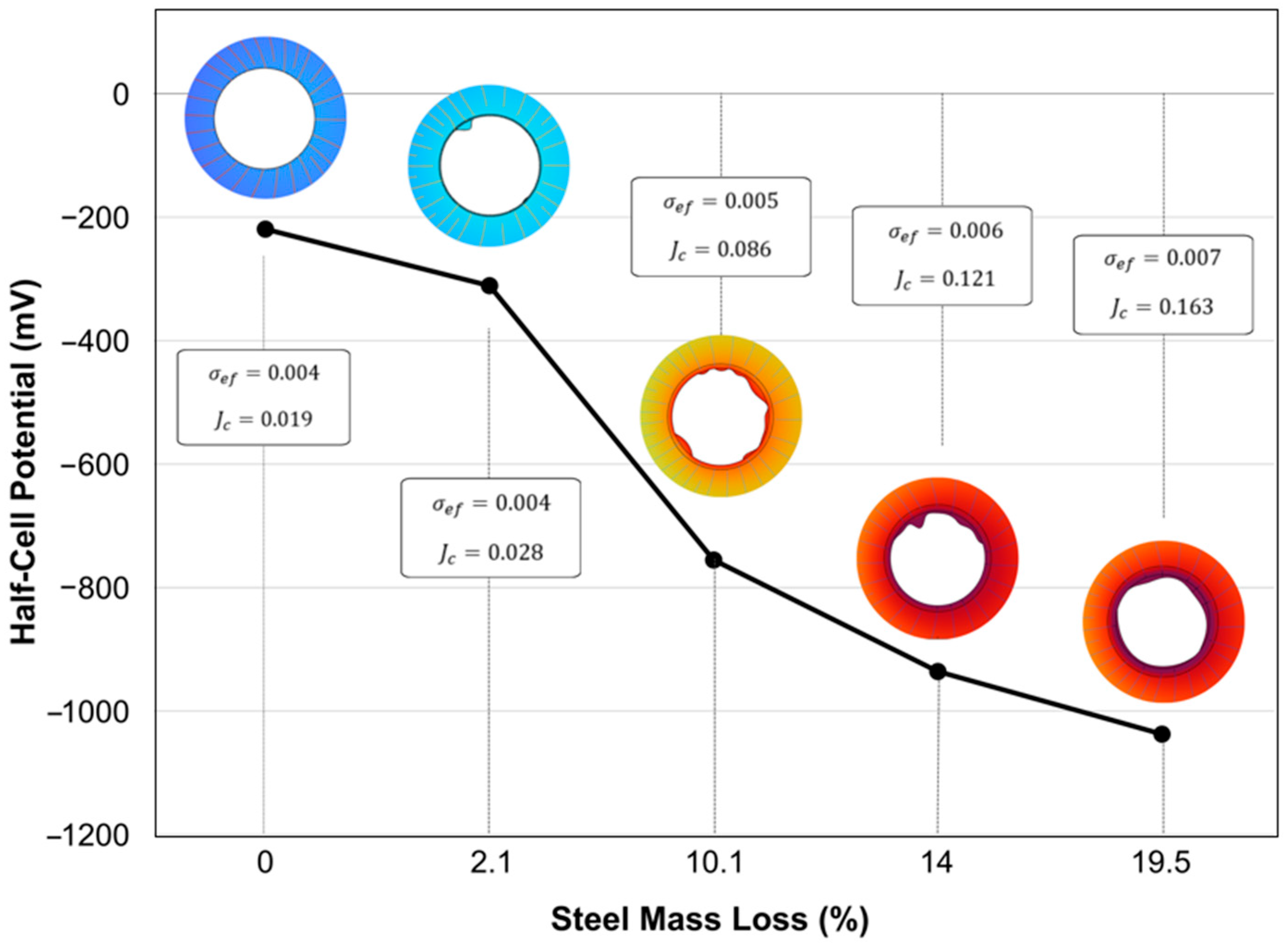

4.3. Numerical Simulation Visualization of HCP and Corroded Specimens

4.4. Summary and Practical Applications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguirre-Guerrero, A.M.; de Gutiérrez, R.M. Assessment of corrosion protection methods for reinforced concrete. In Eco-Efficient Repair and Rehabilitation of Concrete Infrastructures; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2018; pp. 315–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, K.P.V.; Gucunski, N.; Kee, S.H. Evaluation of steel corrosion-induced concrete damage using electrical resistivity measurements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Kanavaris, F.; Das, B.B.; Idrees, M. Decarbonising cement and concrete production: Strategies, challenges and pathways for sustainable development. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannuzzi, M.; Frankel, G.S. The carbon footprint of steel corrosion. npj Mater. Degrad. 2022, 6, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, G.H.; Brongers, M.P.H.; Thompson, N.G.; Virmani, Y.P.; Payer, J.H. Corrosion Costs and Preventive Strategies in the United States. In Handbook of Environmental Degradation of Materials; William Andrew: Norwich, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Syll, A.S.; Kanakubo, T. Impact of Corrosion on the Bond Strength between Concrete and Rebar: A Systematic Review. Materials 2022, 15, 7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidari, O.; Singh, B.K.; Maheshwari, R. Effect of corrosion on bond between reinforcement and concrete—An experimental study. Discov. Civ. Eng. 2024, 1, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Qiao, X.; Guan, H.; Zhou, Z.; Song, D. Research Progress in Corrosion Behavior and Anti-Corrosion Methods of Steel Rebar in Concrete. Metals 2024, 14, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemor, M.F.; Simões, A.M.P.; Ferreira, M.G.S. Chloride-induced corrosion on reinforcing steel: From the fundamentals to the monitoring techniques. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2003, 25, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, M.; Carusi, V.; Forte, A.; Lavorato, D.; Raoli, G.; Santini, S. A probabilistic interpretation of corrosion state through half-cell potential and electrical resistivity measures: The Flaminio Bridge in Rome. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leelalerkiet, V.; Kyung, J.W.; Ohtsu, M.; Yokota, M. Analysis of half-cell potential measurement for corrosion of reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2004, 18, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, D.; Gunasekaran, J.S.; Iyappan, K.; Mani, G. Corrosion assessment study using half cell potentiometer with different electrodes. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2912, 020011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsener, B.; Andrade, C.; Gulikers, J.; Polder, R.; Raupach, M. Half-cell potential measurements—Potential mapping on reinforced concrete structures. Mater. Struct. 2003, 36, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, K.P.V.; Yee, J.J.; Gucunski, N.; Kee, S.H. Calibrating electrical resistivity measurements in reinforced concrete with rebar effects and practical guidelines. Measurement 2025, 244, 116542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C876-15; Standard Test Method for Corrosion Potentials of Uncoated Reinforcing Steel in Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- Yodsudjai, W.; Pattarakittam, T. Factors influencing half-cell potential measurement and its relationship with corrosion level. Measurement 2017, 104, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, K.P.V.; Yee, J.J.; Gucunski, N.; Kee, S.H. Hybrid data-driven machine learning approach for evaluating steel corrosion in concrete using electrical resistivity and documented concrete performance indicators. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 489, 142154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chansuriyasak, K.; Wanichlamlart, C.; Sancharoen, P.; Kongprawechnon, W.; Tangtermsirikul, S. Comparison between half-cell potential of reinforced concrete exposed to carbon dioxide and chloride environment. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2010, 32, 461–468. [Google Scholar]

- Tefera, B.B.; Tarekegn, A.G. Non-Destructive Testing Techniques for Condition Assessment of Concrete Structures: A Review. Am. J. Civ. Eng. 2025, 13, 10–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almashakbeh, Y.; Saleh, E.; Al-Akhras, N.M. Evaluation of Half-Cell Potential Measurements for Reinforced Concrete Corrosion. Coatings 2022, 12, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hao, H.; Hao, Y.; Cui, J. Experimental study of dynamic bond behaviour between corroded steel reinforcement and concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 356, 129272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.B.; Zheng, S.S.; Dong, L.G.; Zheng, Y. Bond behavior of corroded reinforcements in concrete: An experimental study and hysteresis model. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2023, 23, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Alami, E.; Fekak, F.-E.; Garibaldi, L.; Moustabchir, H.; Elkhalfi, A.; Scutaru, M.L.; Vlase, S. Numerical Study of the Bond Strength Evolution of Corroded Reinforcement in Concrete in Pull-Out Tests. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, N.; Sharma, A. Pull-Out Test for Studying Bond Strength in Corrosion Affected RC Structures—A Review. Otto-Graf-J. 2019, 18, 259–272. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, K. Machine learning prediction and interpretability of bond strength in corroded reinforced concrete under high temperatures. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 46, 112630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, K.P.; Kee, S.-H. Numerical simulation of the interference between a surface breaking crack and electrical potential field in concrete. Archit. Inst. Korea 2021, 41, 455–456. Available online: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE11025005 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- ASTM G1-03; Standard Practice for Preparing, Cleaning, and Evaluating Corrosion Test Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM C876-91; Standard Test Method for Half-Cell Potentials of Uncoated Reinforcing Steel in Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1999.

- ASTM C234; Standard Test Method for Comparing Concrete on the Basis of Bond Development with Reinforcing Steel. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2002. Available online: https://www.sciepub.com/reference/275778 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Jo, S.-H.; Kee, S.-H.; Yee, J.-J.; Lee, C. Effect of Corrosion Level and Crack Width on the Bond-Slip Behavior at the Interface between Concrete and Corroded Steel Rebar. J. Korea Inst. Struct. Maint. Insp. 2023, 27, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AC/DC Module User’s Guide. 1998. Available online: www.comsol.com/blogs (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- The Electric Currents Interface. Available online: https://doc.comsol.com/5.6/doc/com.comsol.help.acdc/acdc_ug_electric_fields.07.044.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Li, Q.; Lan, J.; Shen, L.; Yang, J.; Chen, C.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, C. A state-of-the-art review on monitoring technology and characterization of reinforcement corrosion in concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, A.R.M. Ohm’s Law: Relationship Between Voltage, Current, and Resistance; Department of Engineering, Shorouk Academy: Cairo, Egypt, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Arbab, A.I.; Alsaawi, N.N. The dual continuity equations. Optik 2021, 248, 168095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocking, D.; Nougués, J.M.; Rodríguez, J.C.; Sama, S. Chapter 3.3: Simulation, design & analysis. Comput. Aided Chem. Eng. 2002, 11, 165–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevtsov, D.S.; Zartsyn, I.D.; Komarova, E.S. Relation between resistivity of concrete and corrosion rate of reinforcing bars caused by galvanic cells in the presence of chloride. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 119, 104026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.G.; Zhang, W.P.; Gu, X.L.; Dai, H.C. Determination of residual cross-sectional areas of corroded bars in reinforced concrete structures using easy-to-measure variables. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 846–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Xia, H.; Yan, F.; Zhang, K.; Guo, R. The Effect of Moisture Content on the Electrical Properties of Graphene Oxide/Cementitious Composites. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xu, J.; Bai, E.; Luo, X.; Chen, H.; Liu, G.; Chang, S. Study on the Effects of Carbon Fibers and Carbon nanofibers on Electrical Conductivity of Concrete. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 267, 032011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuhata, M. Electrical Conductivity Measurement of Electrolyte Solution. Electrochemistry 2022, 90, 102011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ress, J.; Monrrabal, G.; Díaz, A.; Pérez-Pérez, J.; Bastidas, J.M.; Bastidas, D.M. Microbiologically influenced corrosion of welded AISI 304 stainless steel pipe in well water. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 116, 104734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuthalapati, S.; Kee, K.E.; Ismail, M.C.; Jumbri, K.; Pedapati, S.R. Comparative study of corrosion behaviour and microstructural analysis of as-received and sensitized SS304 U-bend samples under perlite thermal insulation using chloride drip test. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 159, 108054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, K.P.V.; Kim, D.W.; Yee, J.J.; Lee, J.W.; Kee, S.H. Electrical Resistivity Measurements of Reinforced Concrete Slabs with Delamination Defects. Sensors 2020, 20, 7113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacuan, C.N.; Abellana, V.Y. Bond Deterioration of Corroded-Damaged Reinforced Concrete Structures Exposed to Severe Aggressive Marine Environment. Int. J. Corros. 2021, 2021, 8847716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akduman, S.; Öztürk, H. Effect of Reinforcement Corrosion on Structural Behavior in Reinforced Concrete Structures According to Initiation and Propagation Periods. Buildings 2024, 14, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabed, A.; Tusher, M.M.H.; Shuvo, M.S.I.; Imam, A. Corrosion of Steel Rebar in Concrete: A Review. Corros. Sci. Technol. 2023, 22, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakakaki, A.; Apostolopoulos, C. The size effect of rebars, on the structural integrity of reinforced concrete structures, which are exposed to corrosive environments. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 188, 03009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morla, P.; Gupta, R.; Azarsa, P.; Sharma, A. Corrosion Evaluation of Geopolymer Concrete Made with Fly Ash and Bottom Ash. Sustainability 2021, 13, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.W.; Saraswathy, V. Corrosion Monitoring of Reinforced Concrete Structures—A Review. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2007, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.W.; Huang, J.Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, Y.W.; Mansour, W.; Kai, M.F.; Qin, S.F.; Wang, P. Steel corrosion induced shear performance deterioration of RC beams: Experimental investigation and numerical simulation. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, K.P.; Kee, S.-H. Experimental Investigation on the Influence of Degree of Saturation to the Effect of Steel Reinforcements to the Electrical Resistivity of Reinforced Concrete. J. Acad. Conf. Korean Concr. Inst. 2022, 34, 391–392. Available online: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE11064809 (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Robles, K.P.; Kee, S.-H. Effects of the Presence of Reinforcing Steel on Electrical Resistivity Measurements in Concrete by Numerical Simulation. Korea Concr. Inst. 2021, 33, 425–426. Available online: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE10665923 (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Robles, K.P.V.; Yee, J.J.; Kee, S.H. Simulation-Based Assessment of the Impact of Internal and Surface-Breaking Cracks on Reinforced Concrete Electrical Resistivity. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Civil Engineering and Architecture, Volume 2, Da Nang, Vietnam, 7–9 December 2024; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering. Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 641, pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z.; Lin, Z.; Pan, H.; Huang, Y.; Tang, F.; Jiang, L. Synergizing empirical and AI methods to examine nano-silica’s microscale contribution to epoxy coating corrosion resistance. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 47172–47191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Niu, D.; Wu, H.; Fu, Q. Study on corrosion characteristics of reinforcing bars in concrete under industrial SO2 environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 135177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Half-Cell Potential with Cu/CuSO4 Electrode (E) [mV] | Corrosion Probability | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| More negative than −350 mV | >90% probability of active corrosion | Indicates a high likelihood of active corrosion. |

| Between −200 mV and −350 mV | Intermediate probability | Corrosion potential is uncertain and require further assessment. |

| More positive than −200 mV | <10% probability of active corrosion | Suggests a very low likelihood of active corrosion. |

| Mix | Design Strength (MPa) | w/c Ratio | Porosity * (%) | Unit Weight (kg/m3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | C | G | S | AE | ||||

| Mix 1 | 18 | 0.585 | 8.38 | 168 | 287 | 898 | 957 | 2.58 |

| Mix 2 | 24 | 0.507 | 7.59 | 170 | 335 | 956 | 870 | 2.5 |

| Mix 3 | 40 | 0.346 | 8.01 | 166 | 480 | 993 | 720 | 4.32 |

| HCP | Bond Strength Degradation (%) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ≤−200 mV | ~0–5% | Negligible corrosion |

| −200 mV < x < −350 mV | ~5–20% | Moderate corrosion |

| ≥−350 mV | ~20–50% | Severe corrosion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Serwelas, J.P.M.; Kee, S.-H.; Monjardin, C.E.F.; Robles, K.P.V. A Combined Experimental and Analytical Analysis of the Prediction of the Bonding Strength in Corroded Reinforced Concrete Through Half-Cell Potential Measurements. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2025, 6, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040064

Serwelas JPM, Kee S-H, Monjardin CEF, Robles KPV. A Combined Experimental and Analytical Analysis of the Prediction of the Bonding Strength in Corroded Reinforced Concrete Through Half-Cell Potential Measurements. Corrosion and Materials Degradation. 2025; 6(4):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040064

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerwelas, John Paulo M., Seong-Hoon Kee, Cris Edward F. Monjardin, and Kevin Paolo V. Robles. 2025. "A Combined Experimental and Analytical Analysis of the Prediction of the Bonding Strength in Corroded Reinforced Concrete Through Half-Cell Potential Measurements" Corrosion and Materials Degradation 6, no. 4: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040064

APA StyleSerwelas, J. P. M., Kee, S.-H., Monjardin, C. E. F., & Robles, K. P. V. (2025). A Combined Experimental and Analytical Analysis of the Prediction of the Bonding Strength in Corroded Reinforced Concrete Through Half-Cell Potential Measurements. Corrosion and Materials Degradation, 6(4), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040064