Synchrotron X-Ray Techniques for In Situ or Microscopic Study of Passive Films on Industrial Alloys: A Mini Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

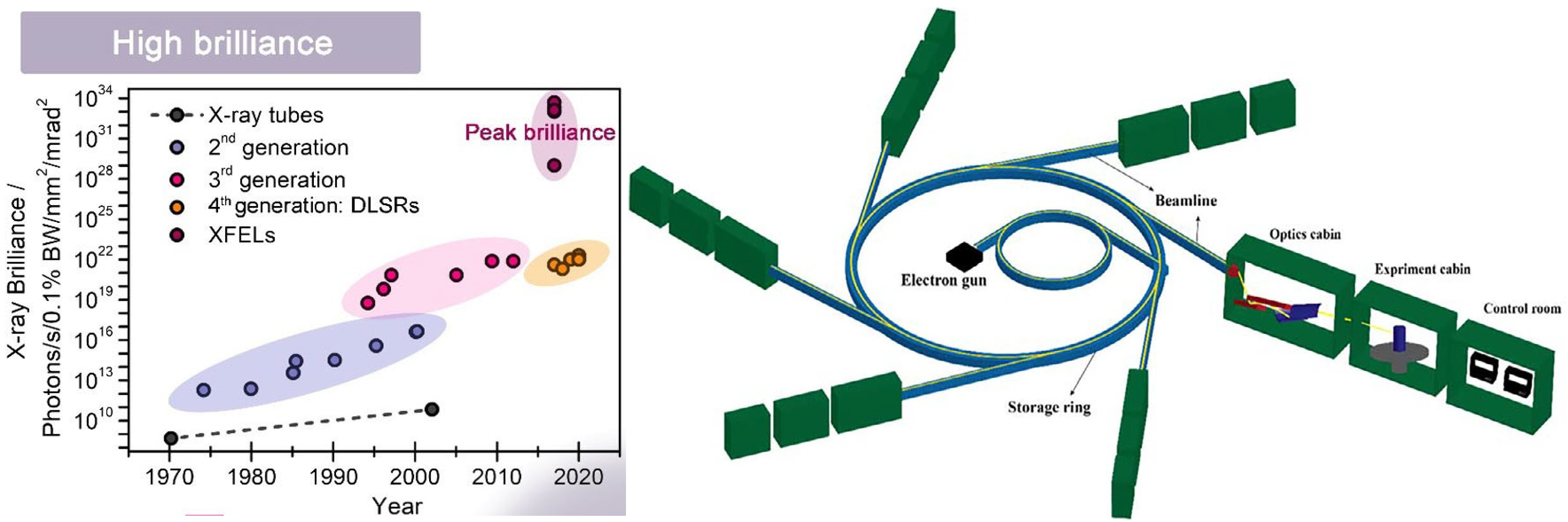

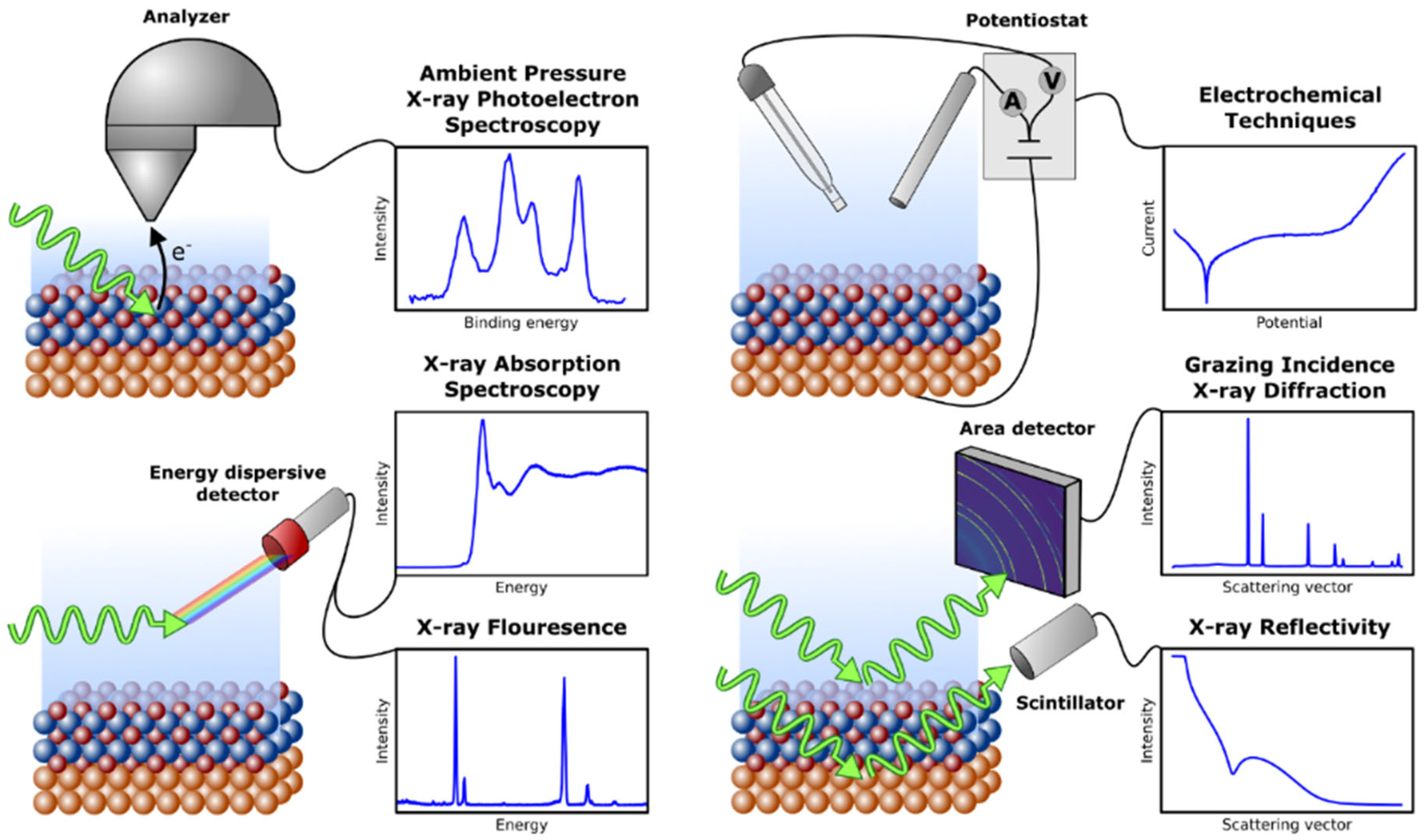

2. Synchrotron X-Ray Techniques for the Study of Corrosion Processes

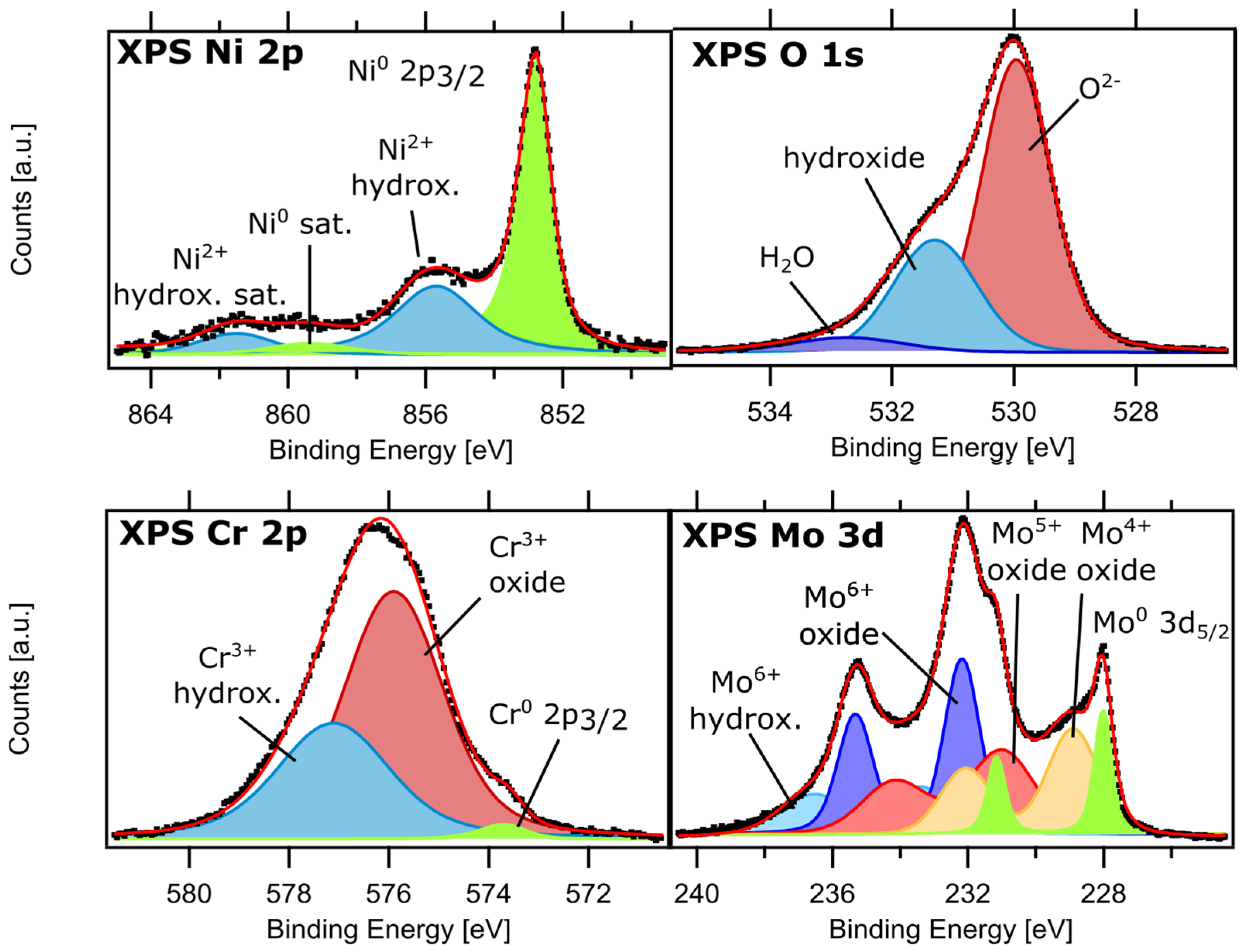

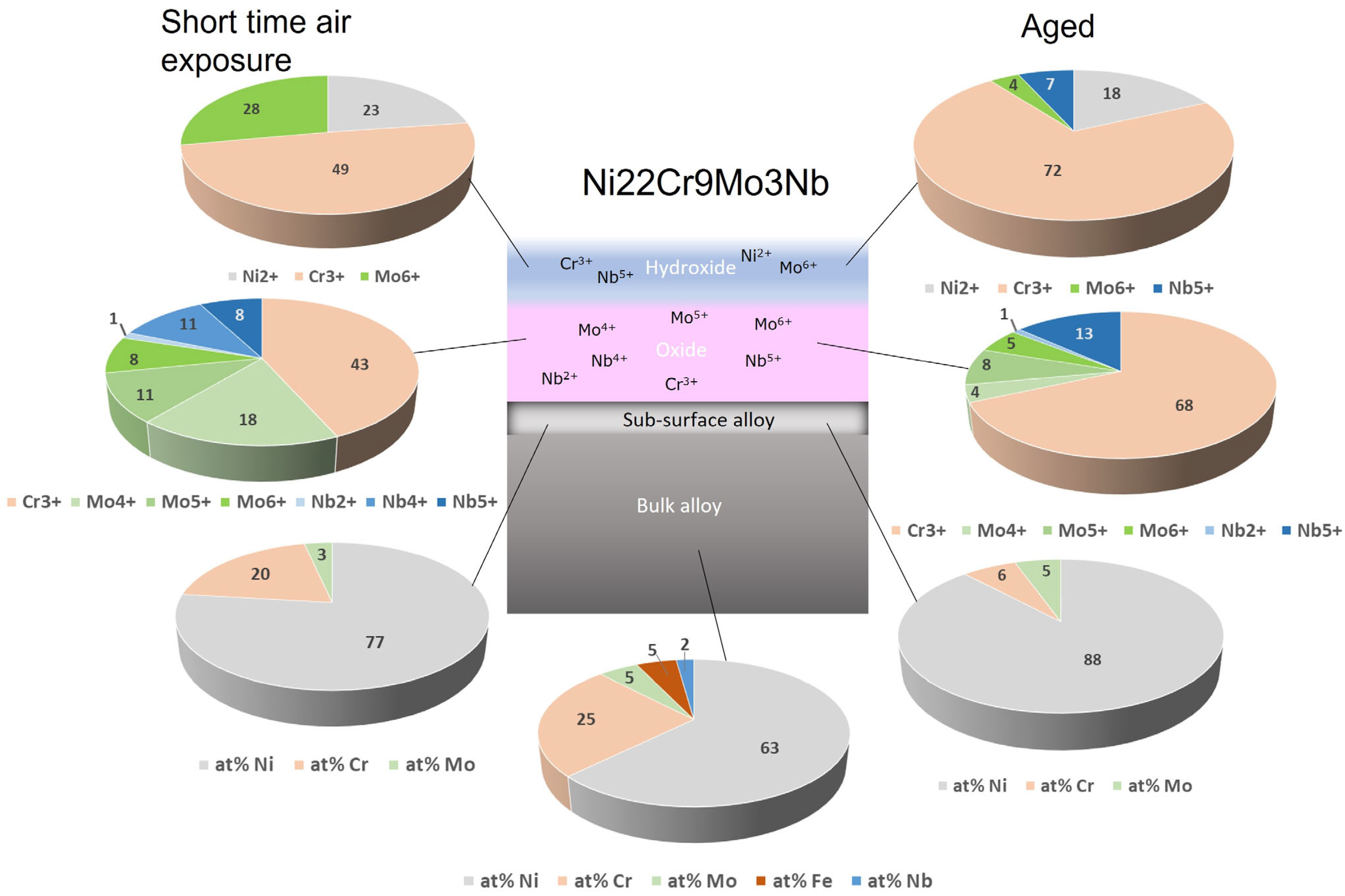

3. Synchrotron X-Ray Photoemission Techniques for Analysis of Passive Films

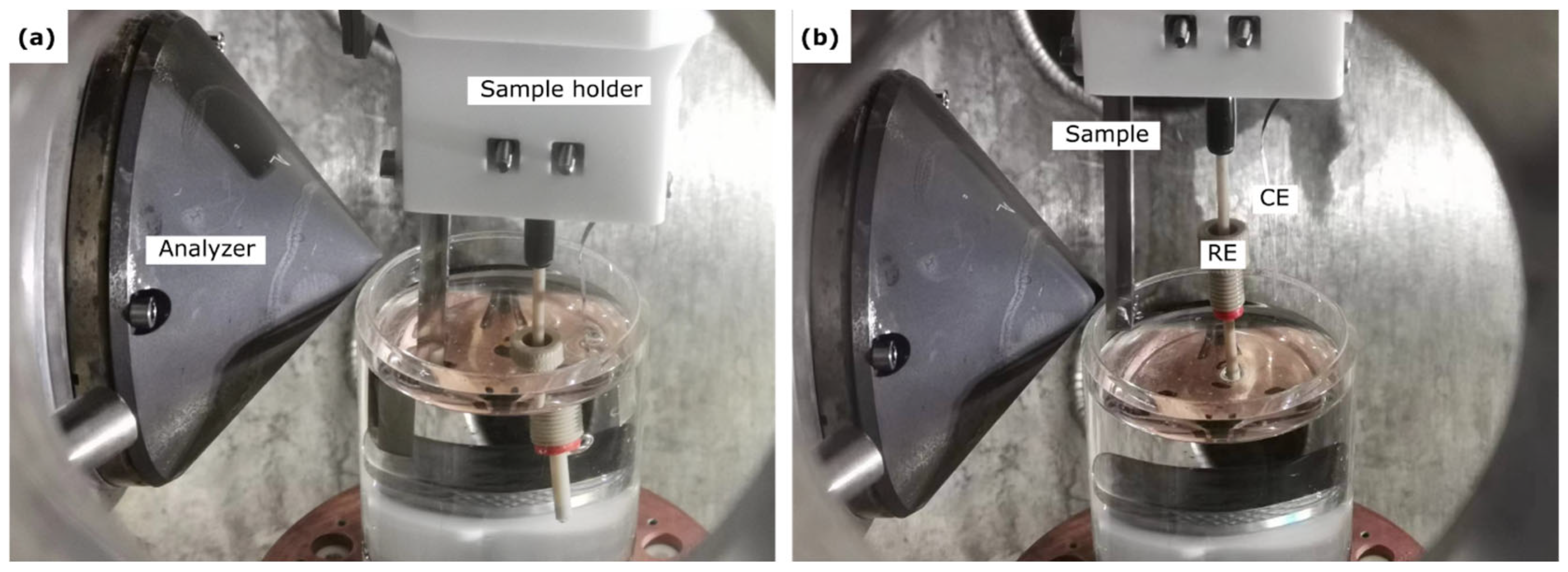

4. In Situ Synchrotron AP-XPS Analysis of Passive Films—Electrochemical Systems

5. HAXPEEM Mapping of Passive Films on Heterogeneous Industrial Alloys

6. Combined Synchrotron X-Ray Techniques for Operando Study of Passive Film Degradation

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Macdonald, D.D. Passivity—The key to our metals-based civilization. Pure Appl. Chem. 1999, 71, 951–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultze, J.W.; Lohrengel, M.M. Stability, reactivity and breakdown of passive films. Problems of recent and future research. Electrochim. Acta 2000, 45, 2499–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuki, P. From Bacon to barriers: A review on the passivity of metals and alloys. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2002, 6, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, C.O.A.; Landolt, D. Passive films on stainless steels—Chemistry, structure and growth. Electrochim. Acta 2003, 48, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehblow, H.-H.; Maurice, V.; Marcus, P. Passivity of Metals. In Corrosion Mechanisms in Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Marcus, P., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2011; pp. 235–326. [Google Scholar]

- Maurice, V.; Marcus, P. Passive films at the nanoscale. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 84, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehblow, H.-H. Passivity of metals studied by surface analytical methods, a review. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 212, 630–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, V.; Marcus, P. Progress in corrosion science at atomic and nanometric scales. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 95, 132–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, G.S. Pitting corrosion of metals a review of the critical factors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1998, 145, 2186–2198, Correction in J. Electrochem. Soc. 1998, 145, 2970a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, P.; Strehblow, H.-H.; Maurice, V. Localized corrosion (pitting): A model of passivity breakdown including the role of the oxide layer nanostructure. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 2698–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehblow, H.-H.; Marcus, P. Mechanisms of Pitting Corrosion. In Corrosion Mechanisms in Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Marcus, P., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2011; pp. 349–393. [Google Scholar]

- Soltis, J. Passivity breakdown, pit initiation and propagation of pits in metallic materials—Review. Corros. Sci. 2015, 90, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, G.S.; Li, T.; Scully, J.R. Localized corrosion: Passive film breakdown vs. pit growth stability. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, C180–C181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Li, S.H.; Qian, Y.Y.; Zhu, W.K.; Yuan, H.B.; Jiang, P.Y.; Guo, R.H.; Wang, L.B. High-entropy alloys as a platform for catalysis: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 11280–11306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Thomas, S.; Macdonald, D.D.; Birbilis, N. Growth kinetics of multi-oxide passive film formed upon the multi-principal element alloy AlTiVCr: Effect of transpassive dissolution of V and Cr. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 051506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, Q.; Hu, J. High-entropy alloy with Mo-coordination as efficient electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 10808–10817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Sun, S.; Choi, S.; Lee, K.; Jo, S.; Park, K.; Kim, Y.K.; Park, H.B.; Park, H.Y.; Jang, J.H.; et al. Tailored electronic structure of Ir in high entropy alloy for highly active and durable bifunctional electrocatalyst for water splitting under an acidic Environment. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2300091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, A.; Morell, D.; von der Au, M.; Wittstock, G.; Ozcan, O.; Witt, J. Transpassive metal dissolution vs. oxygen evolution reaction: Implication for alloy stability and electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202317058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Carrière, C.; Seyeux, A.; Zanna, S.; Mercier, D.; Marcus, P. XPS and ToF-SIMS investigation of native oxides and passive films formed on nickel alloys containing chromium and molybdenum. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 041503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, B.; Neupane, S.; Wiame, F.; Seyeux, A.; Maurice, V.; Marcus, P. An XPS and ToF-SIMS study of the passive film formed on a model FeCrNiMo stainless steel surface in aqueous media after thermal pre-oxidation at ultra-low oxygen pressure. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 554, 149435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinder, J.W.; Kulbacki, B.; Baer, D.R.; Biesinger, M.; Castle, J.; Castner, D.; Easton, C.; Grant, J.; Greczynski, G.; Harmer, S.; et al. What is in a name? “ESCA” or “XPS”? A discussion of comments made by Kai Siegbahn more than four decades ago regarding the name of the technique. Surf. Interface Anal. 2025, 57, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leygraf, C.; Ekelund, S.; Schon, G. Electron spectroscopy for chemical analysis and electron microscopy studies of oxide films on an 18-8 stainless steel. Scand. J. Metall. 1973, 2, 313. [Google Scholar]

- Leygraf, C.; Hultquist, G.; Ekelund, S.; Eriksson, J.C. Surface composition studies of the (100) and (110) faces of monocrystalline Fe0·84Cr0·16. Surf. Sci. 1974, 46, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leygraf, C.; Hultquist, G.; Olefjord, I.; Elfström, B.-O.; Knyazheva, V.M.; Plaskeyev, A.V.; Kolotyrkin, Y.M. Selective dissolution and surface enrichment of alloy components of passivated Fe18Cr and Fe18Cr3Mo single crystals. Corros. Sci. 1979, 19, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecznski, G.; Hultman, L. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: Towards reliable binding energy referencing. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2020, 107, 100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroux, A.; Duguet, T.; Ducommun, N.; Nivet, E.; Delgado, J.; Laffont, L.; Blanc, C. Combined XPS/TEM study of the chemical composition and structure of the passive film formed on additive manufactured 17-4PH stainless steel. Surf. Interface 2021, 22, 100874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Huang, S.; Liu, Z.; Du, C. Investigations on the passive and pitting behaviors of the multiphase stainless steel in chlorine atmosphere. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 28, 3365–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Kelly, R.G.; Birbilis, N. On the origin of passive film breakdown and metastable pitting for stainless steel 316L. Corros. Sci. 2024, 230, 111911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.X.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Y.T.; Chen, Z.Y.; Li, X.L.; Ma, X.L. Transpassivation-induced structural evolution of oxide film on 654SMO super austenitic stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 2024, 232, 112030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice, V.; Marcus, P. Molybdenum effects on the stability of passive films unraveled at the nanometer and atomic scales. npj Mater. Deg. 2024, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Henderson, J.D.; Filice, F.P.; Zagidulin, D.; Biesinger, M.C.; Sun, F.; Qian, B.; Shoesmith, D.W.; Noël, J.J.; Ogle, K. The contribution of Cr and Mo to the passivation of Ni22Cr and Ni22Cr10Mo alloys in sulfuric acid. Corros. Sci. 2020, 176, 109015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkoua, C.; Esvan, J.; Tribollet, B.; Basseguy, R.; Blanc, C. Combined electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy analysis of the passive films formed on 5083 aluminium alloy. Corro. Sci. 2023, 221, 11337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, S.K.; Kumar, S.; Maulik, O.; Pillai, G.M.; Kumar, V.; Ahn, B. XPS study on passivation behavior of naturally formed oxide on AlFeCuCrMg1.5 high-entropy alloy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2024, 841, 141171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Li, Y.; Cao, F.; Qiu, D.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Ying, T.; Ding, W.; Zeng, X. Towards development of a high-strength Mg alloy with Al-assisted growth of passive film. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eda, Y.; Hanawa, T.; Chen, P.; Ashida, M.; Noda, K. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy-based valence band spectra of passive films on titanium. Surf. Interface Anal. 2022, 54, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yu, M.; Han, C.; Zhao, Z.; Jia, X.; Zhao, M.; Li, S.; Liu, J. Evolution and corrosion resistance of passive film with polarization potential on Ti-5Al-5Mo-5V-1Fe-1Cr alloy in simulated marine environments. Corros. Sci. 2023, 221, 111334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaha, I.; Alves, A.C.; Chirico, C.; Pinto, A.M.; Tsipas, S.; Gordo, E.; Bondarchuk, O.; Deepak, F.L.; Toptan, F. Atomic–scale investigations of passive film formation on Ti-Nb alloys. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 615, 156282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Li, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Guo, F.; Liu, D. Electrochemical behavior, passive film characterization and in vitro biocompatibility of Ti-Zr-Nb medium-entropy alloys. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laïk, B.; Richet, M.; Emery, N.; Bach, S.; Perrie, L.; Cotrebil, Y.; Russier, V.; Guillot, I.; Dubot, P. XPS Investigation of Co−Ni Oxidized Compounds Surface Using Peak-On-Satellite Ratio. Application to Co20Ni80 Passive Layer Structure and Composition. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 40707–40722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Han, J.; Sun, F.; Ogle, K. The spontaneous passivation of multi principal element alloys II: The effect of Mn in the CoCrFeNiMn family. Corros. Sci. 2025, 244, 112642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, B.; Jin, B.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, N.; Zuo, X. Effects of polarization potential on the passive film properties of CoCrFeNi high-entropy alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1032, 181061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shard, A.G. Practical Guides for X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: Quantitative XPS. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2020, 38, 041201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greczynski, G.; Hultman, L. A step-by-step guide to perform x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 132, 011101, Correction in J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 132, 129901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grecznski, G.; Hultman, L. Binding energy referencing in X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2025, 10, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, W.; Liu, Z. Recent progress on synchrotron-based in-situ soft X-ray spectroscopy for energy materials. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 7710–7729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mino, L.; Borfecchia, E.; Segura-Ruiz, J.; Giannini, C.; Martinez-Criado, G.; Lamberti, C. Materials characterization by synchrotron x-ray microprobes and nanoprobes. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018, 90, 025007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimabadi, P.S.; Khodaei, M.; Koswattage, K.R. Review on applications of synchrotron-based X-ray techniques in materials characterization. X-Ray Spectrom. 2020, 49, 348–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketenoglu, D. A general overview and comparative interpretation on element-specific X-ray spectroscopy techniques: XPS, XAS, and XRS. X-Ray Spectrom. 2022, 51, 422–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X.; Cheng, L.; Singer, A.; Shpyrko, O.G.; Xin, H.L.; Tamura, N.; Tian, C.; Weng, T.-C.; et al. Synchrotron X-ray analytical techniques for studying materials electrochemistry in rechargeable batteries. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 13123–13186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagus, P.S.; Freund, H.-J. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy as a useful tool to study surfaces and model systems for heterogeneous catalysts: A review and perspective. Surf. Sci. 2024, 745, 122471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Liao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Dai, W.; Huang, T. Advanced XPS-based techniques in the characterization of catalytic materials: A mini-review. Catalysts 2024, 14, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barawi, M.; Mesa, C.A.; Collado, L.; Villar-Garcia, I.J.; Oropeza, F.; O’Shea, V.A.d.l.P.; Garxia-Tecedor, M. Latest advances in in situ and operando X-ray-based techniques for the characterisation of photoelectrocatalytic systems. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 23125–23146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Sun, S.; Bao, J. Synchrotron radiation based X-ray absorption spectroscopy: Fundamentals and applications in photocatalysis. ChemPhysChem 2024, 25, e202300939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wei, S.; Cao, D.; Sheng, B.; Chu, Y.; Chen, S.; Song, L.; Liu, X. Understanding solid-gas and solid-liquid interfaces through near ambient pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2025, 41, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-C.; Lin, Y.-R.; Peng, C.-K.; Lin, Y.-D.; Lin, Y.-C.; Huang, S.-C.; Chen, H.M.; Lin, Y.-G. Glimpsing the dynamics at solid–liquid interfaces using in situ/operando synchrotron radiation techniques. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2025, 6, 2500029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Walsh, F.C. In situ Synchrotron radiation X-ray techniques for studies of corrosion and protection. Corros. Sci. 1993, 35, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, M.; Shimizu, T.; Konishi, H.; Mizuki, J.; Uchida, H. Structure and protective performance of atmospheric corrosion product of Fe–Cr alloy film analyzed by MÖssbauer spectroscopy and with synchrotron radiation X-rays. Corros. Sci. 2003, 45, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayment, T.; Davenport, A.J.; Dent, A.J.; Tinnes, J.-P.; Wiltshire, R.J.K.; Martin, C.; Clark, G.; Quinn, P.; Mosselmans, J.F.W. Characterisation of salt films on dissolving metal surfaces in artificial corrosion pits via in situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction. Electrochem. Commun. 2008, 10, 855–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, J.; Duda, L.-C.; Olsson, A.; Schmitt, T.; Andersson, J.; Nordgren, J.; Hedberg, J.; Leygraf, C.; Aastrup, T.; Wallinder, D.; et al. System for in situ studies of atmospheric corrosion of metal films using soft x-ray spectroscopy and quartz crystal microbalance. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2007, 78, 083110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowsett, M.; Adriaens, A.; Martin, C.; Bouchenoire, L. The use of synchrotron X-rays to observe copper corrosion in real time. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 4866–4872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowsett, M.-G.; Adriaens, A. Cell for simultaneous synchrotron radiation X-ray and electrochemical corrosion measurements on cultural heritage metals and other materials. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 3360–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adriaens, A.; Dowsett, M. The coordinated use of synchrotron spectroelectrochemistry for corrosion studies on heritage metals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, R.D.; Jiang, Z.-T.; Pejcic, B.; Poinen, E. An in situ synchrotron radiation grazing incidence X-ray diffraction study of carbon dioxide corrosion. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2005, 152, B389–B392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingham, B.; Ko, M.; Kear, G.; Kappen, P.; Laycock, N.; Kimpton, J.A.; Williams, D.E. In situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction study of surface scale formation during CO2 corrosion of carbon steel at temperatures up to 90 °C. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 3052–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.; Ingham, B.; Laycock, N.; Williams, D.E. In situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction study of the effect of chromium additions to the steel and solution on CO2 corrosion of pipeline steels. Corros. Sci. 2014, 80, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, M.; Ingham, B.; Laycock, N.; Williams, D.E. In situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction study of the effect of microstructure and boundary layer conditions on CO2 corrosion of pipeline steels. Corros. Sci. 2015, 90, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haratian, S.; Gupta, K.K.; Larsson, A.; Abbondanza, G.; Bartawi, E.H.; Carla, F.; Lundgren, E.; Ambat, R. Ex-situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction study of CO2 corrosion-induced surface scales developed in low-alloy steel with different initial microstructure. Corros. Sci. 2023, 222, 111387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahari, M.; Krouse, D.; Laycock, N.; Rayment, T.; Padovani, C.; Stampanoni, M.; Marone, F.; Moksoe, R.; Davenport, A.J. Synchrotron X-ray radiography studies of pitting corrosion of stainless steel: Extraction of pit propagation parameters. Corros. Sci. 2015, 100, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.S.; Williams, J.J.; Stannard, T.J.; Xiao, X.; de Carlo, F.; Chawla, N. Measurement of localized corrosion rates at inclusion particles in AA7075 by in situ three dimensional (3D) X-ray synchrotron tomography. Corros. Sci. 2016, 104, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, B.J.; Horner, D.A.; Fox, S.J.; Davenport, A.J.; Padovani, C.; Zhou, S.; Turnbull, A.; Preuss, M.; Stevens, N.P.; Marrow, T.J.; et al. X-ray microtomography studies of localized corrosion and transitions to stress corrosion cracking. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2006, 22, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoell, R.; Xi, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, X.; Yu, Z.; Kenesei, P.; Almer, J.; Shayer, Z.; Kaoumi, D. In situ synchrotron X-ray tomography of 304 stainless steels undergoing chlorine-induced stress corrosion cracking. Corros. Sci. 2020, 170, 108687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stannard, T.J.; Williams, J.J.; Singh, S.S.; Singaravelu, A.S.S.; Xiao, X.; Chawla, N. 3D time-resolved observations of corrosion and corrosion-fatigue crack initiation and growth in peak-aged Al 7075 using synchrotron X-ray tomography. Corros. Sci. 2018, 138, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ahn, K.; Kim, G.; Song, S.-W. Synchrotron X-ray fluorescence imaging study on chloride-induced stress corrosion cracking behavior of austenitic stainless steel welds via selective corrosion of δ-ferrite. Corros. Sci. 2023, 218, 111176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenbach, C.; Schnatterer, C.; Mercado, U.A.; Suuronen, J.-P.; Zander, D.; Requena, G. Synchrotron-based holotomography and X-ray fluorescence study on the stress corrosion cracking behavior of the peak-aged 7075 aluminum alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 817, 152722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawane, K.; Liu, X.; Gakhar, R.; Woods, M.; Ge, M.; Xiaog, X.; Lee, W.-K.; Halstenberg, P.; Dai, S.; Mahurina, S.; et al. Visualizing time-dependent microstructural and chemical evolution during molten salt corrosion of Ni-20Cr model alloy using correlative quasi in situ TEM and in situ synchrotron X-ray nano-tomography. Corros. Sci. 2022, 195, 109962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadley, C.S. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: Progress and perspectives. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 2010, 178–179, 2–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, S.P. X-Ray Spectroscopy with Synchrotron Radiation: Fundamentals and Applications, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martensson, N.; Föhlisch, A.; Svensson, S. Uppsala and Berkeley: Two essential laboratories in the development of modern photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2022, 40, 043207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, D.R.; Sherwood, P.M.A. Perspective on the development of XPS and the pioneers who made it possible. Front. Anal. Sci. 2025, 4, 1509438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmeron, M.; Schlögl, R. Ambient pressure photoelectron spectroscopy: A new tool for surface science and nanotechnology. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2008, 63, 169–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Bluhm, H.; Andersson, K.; Ketteler, G.; Ogasawara, H.; Salmeron, M.; Nilsson, A. In situ x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy studies of water on metals and oxides at ambient conditions. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 184025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoerzinger, K.A.; Hong, W.T.; Crumlin, E.J.; Bluhm, H.; Shao-Horn, Y. Insight into electrochemical reactions from ambient pressure photoelectron spectroscopy. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2976–2983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, W.; Malmgren, S.; Gustafsson, T.; Gorgoi, M.; Edström, K. Full depth profile of passive films on 316L stainless steel based on high resolution HAXPES in combination with ARXPS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karri, M.; Verma, A.; Singh, J.B.; Bonagani, S.K.; Goutam, U.K. Role of chromium in anomalous behavior of the passive layer in Ni-Cr-Mo alloys in 1 M HCl solution. Corrosion 2022, 78, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A.; D’Acunto, G.; Vorobyova, M.; Abbondanza, G.; Lienert, U.; Hegedüs, Z.; Preobrajenski, A.; Merte, L.R.; Eidhagen, J.; Delblanc, A.; et al. Thickness and composition of native oxides and near-surface regions of Ni superalloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 895, 162657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A.; Gericke, S.; Grespi, A.; Koller, V.; Eidhagen, J.; Yue, X.; Frampton, E.; Appelfeller, S.; Generalov, A.; Preobrajenski, A.; et al. Dynamics of early-stage oxide formation on a Ni-Cr-Mo alloy. npj Mater. Degrad. 2024, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidhagen, J.; Larsson, A.; Preobrajenski, A.; Delblanc, A.; Lundgren, E.; Pan, J. Synchrotron XPS and Electrochemical Study of Aging Effect on Passive Film of Ni Alloys. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2023, 170, 021506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Chen, D.; Krishnan, A.; Tidesten, M.; Larsson, A.; Tong, H.; Gloskovskii, A.; Schlueter, C.; Scardamaglia, M.; Shavorskiy, A.; et al. In depth analysis of the passive film on martensitic tool alloy: Effect of tempering temperature. Corros. Sci. 2024, 234, 112133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlueter, C.; Gloskovskii, A.; Ederer, K.; Schostak, I.; Piec, S.; Sarkar, I.; Matveyev, Y.; Lömker, P.; Sing, M.; Claessen, R.; et al. The new dedicated HAXPES beamline P22 at PETRAIII. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2054, 040010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Scardamaglia, M.; Kundsen, J.; Sankari, R.; Tarawneh, H.; Temperton, R.; Pickworth, L.; Cavalca, F.; Wang, C.; Tissot, H.; et al. HIPPIE: A new platform for ambient-pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy at the MAX IV Laboratory. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2021, 28, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

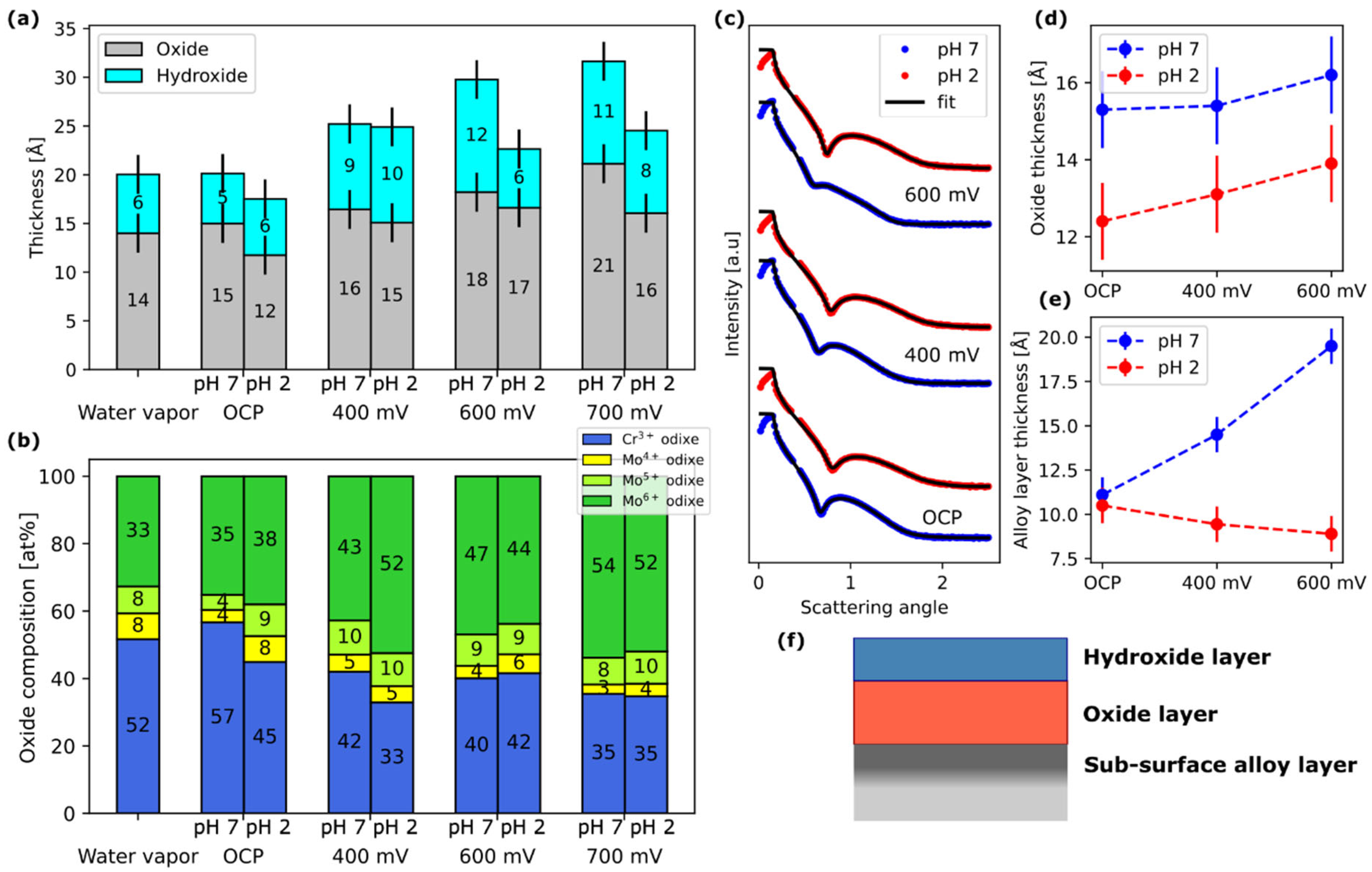

- Larsson, A.; Simonov, K.; Eidhagen, J.; Grespi, A.; Yue, X.; Tang, H.; Delblanc, A.; Scardamaglia, M.; Shavorskiy, A.; Pan, J.; et al. In situ quantitative analysis of electrochemical oxide film development on metal surfaces using ambient pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: Industrial alloys. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 611, 155714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwalina, K.L.; Ha, H.M.; Ott, N.; Reinke, P.; Birbilis, N.; Scully, J.R. In operando analysis of passive film growth on Ni-Cr and Ni-Cr-Mo alloys in chloride solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, C3241–C3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidhagen, J.; Hättestrand, M.; Kivisäkk, U.; Andersson, J.; Lautrup, L.; Yue, X.; Larsson, A.; Grespi, A.; Scardamaglia, M.; Shavorskiy, A.; et al. Passive film evolution on Ni-Cr-Mo alloys in acidic chloride solution during anodic polarization. Corros. Commun. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

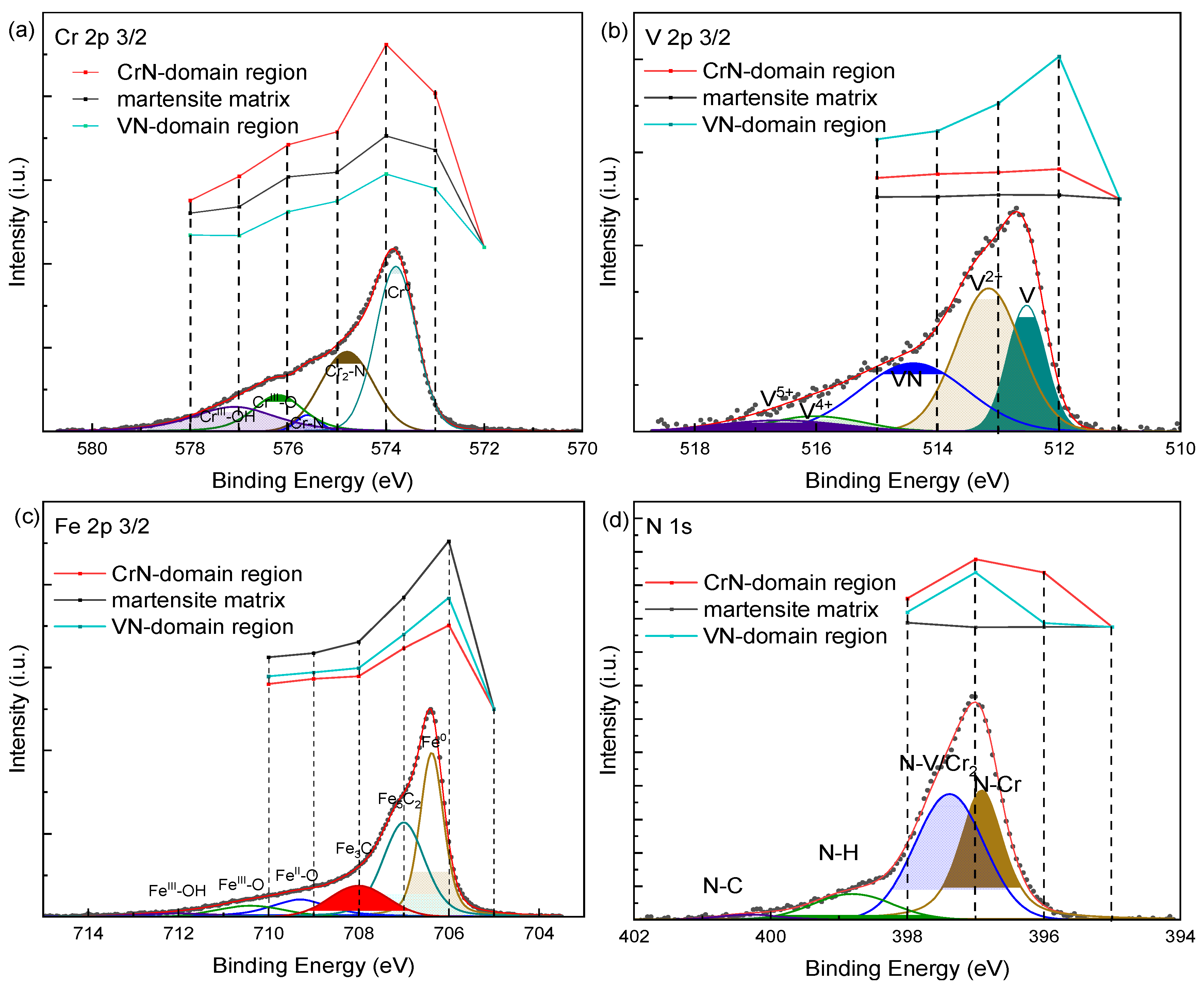

- Yue, X.; Larsson, A.; Tang, H.; Grespi, A.; Scardamaglia, M.; Shavorskiy, A.; Krishnan, A.; Lundgren, E.; Pan, J. Synchrotron-based near ambient-pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and electrochemical studies of passivation behavior of N- and V-containing martensitic stainless steel. Corros. Sci. 2023, 214, 111018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J. Studying the passivity and breakdown of duplex stainless steels at micrometer and nanometer scales—The influence of microstructure. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignal, V.; Delrue, O.; Heintz, O.; Peultier, J. Influence of the passive film properties and residual stresses on the micro-electrochemical behavior of duplex stainless steels. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 7118–7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignal, V.; Krawiec, H.; Heintz, O.; Mainy, D. Passive properties of lean duplex stainless steels after long-term aging in air studied by EBSD, AES, XRS, and local electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Corros. Sci. 2013, 67, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, X.Q.; Li, X.G. Electrochemical behavior and compositions of passive films formed on the constituent phases of duplex stainless steel without coupling. Electrochem. Commun. 2015, 57, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardin, E.; Zanna, S.; Seyeux, A.; Allion-Maurer, A.; Marcus, P. Comparative study of the surface oxide films on lean duplex stainless steel and corresponding signal phase stainless steels by XPS and ToF-SIMS. Corros. Sci. 2018, 143, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patt, M.; Wiemann, C.; Weber, N.; Escher, M.; Gloskovskii, A.; Drube, W.; Merkel, M.; Schneider, C.M. Bulk sensitive hard x-ray photoemission electron microscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2014, 85, 113704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Långberg, M.; Örnek, C.; Zhang, F.; Cheng, J.; Liu, M.; Grånäs, E.; Wiemann, C.; Gloskovskii, A.; Matveyev, Y.; Kulkarni, S.; et al. Characterization of native oxide and passive film on austenite/ferrite phases of duplex stainless steel using synchrotron HAXPEEM. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, C3336–C3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stierle, A.; Keller, T.F.; Noei, H.; Vonk, V.; Roehlsberger, R. DESY NanoLab. J. Large-Scale Res. Facil. 2016, 2, A76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Långberg, M.; Zhang, F.; Grånäs, E.; Örnek, C.; Cheng, J.; Liu, M.; Wiemann, C.; Gloskovskii, A.; Keller, T.; Schlueter, C.; et al. Lateral variation of the native passive film on super duplex stainless steel resolved by synchrotron hard X-ray photoelectron emission microscopy. Corro. Sci. 2020, 174, 108841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

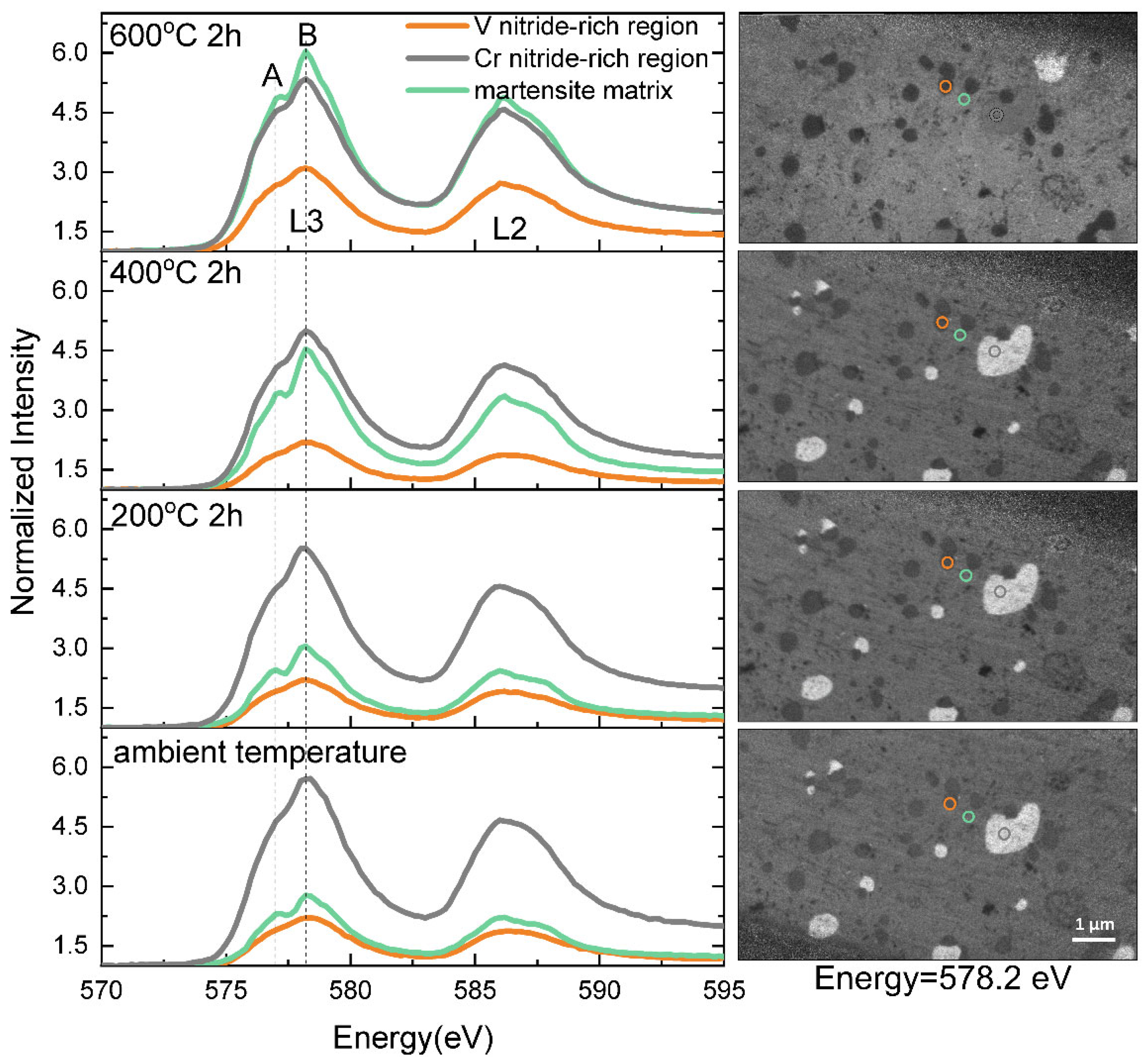

- Yue, X.; Chen, D.; Krishnan, A.; Lazar, I.; Niu, Y.; Golias, E.; Wiemann, C.; Gloskovskii, A.; Schlueter, C.; Jeromin, A.; et al. Unveiling nano-scale chemical inhomogeneity in surface oxide films formed on V- and N-containing martensite stainless steel by synchrotron X-ray photoelectron emission spectroscopy/microscopy and microscopic X-ray absorption spectroscopy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 205, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

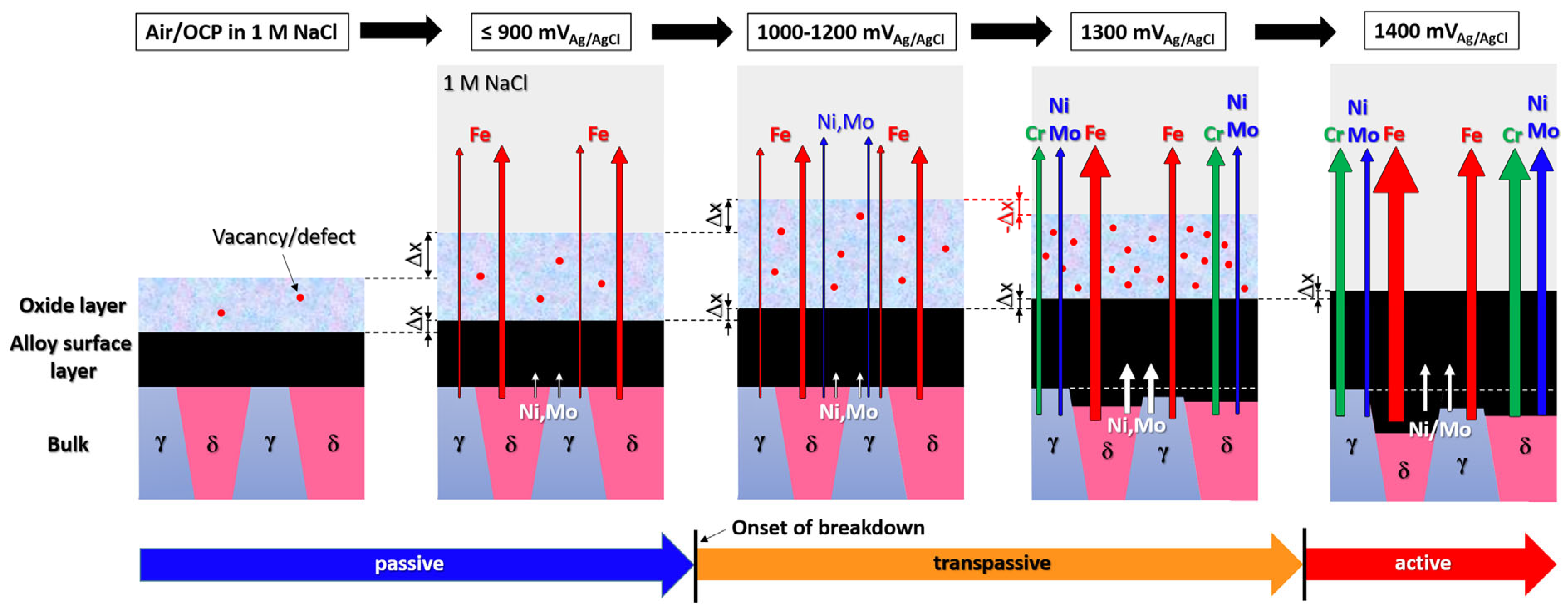

- Långberg, M.; Örnek, C.; Evertsson, J.; Harlow, G.S.; Linpé, W.; Rullik, L.; Carlà, F.; Felici, R.; Bettini, E.; Kivisäkk, U.; et al. Redefining passivity breakdown of super duplex stainless steel by electrochemical operando synchrotron near surface X-ray analysers. npj Mater. Degrad. 2019, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örnek, C.; Långberg, M.; Evertsson, J.; Harlow, G.; Linpé, W.; Rullik, L.; Carlà, F.; Felici, R.; Bettini, E.; Kivisäkk, U.; et al. In-situ synchrotron GIXRD study of passive film evolution on duplex stainless steel in corrosive environment. Corros. Sci. 2018, 141, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örnek, C.; Långberg, M.; Evertsson, J.; Harlow, G.; Linpé, W.; Rullik, L.; Carlà, F.; Felici, R.; Kivisäkk, U.; Lundgren, E.; et al. Influence of surface strain on passive film formation of duplex stainless steel and its degradation in corrosive environment. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, C3071–C3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

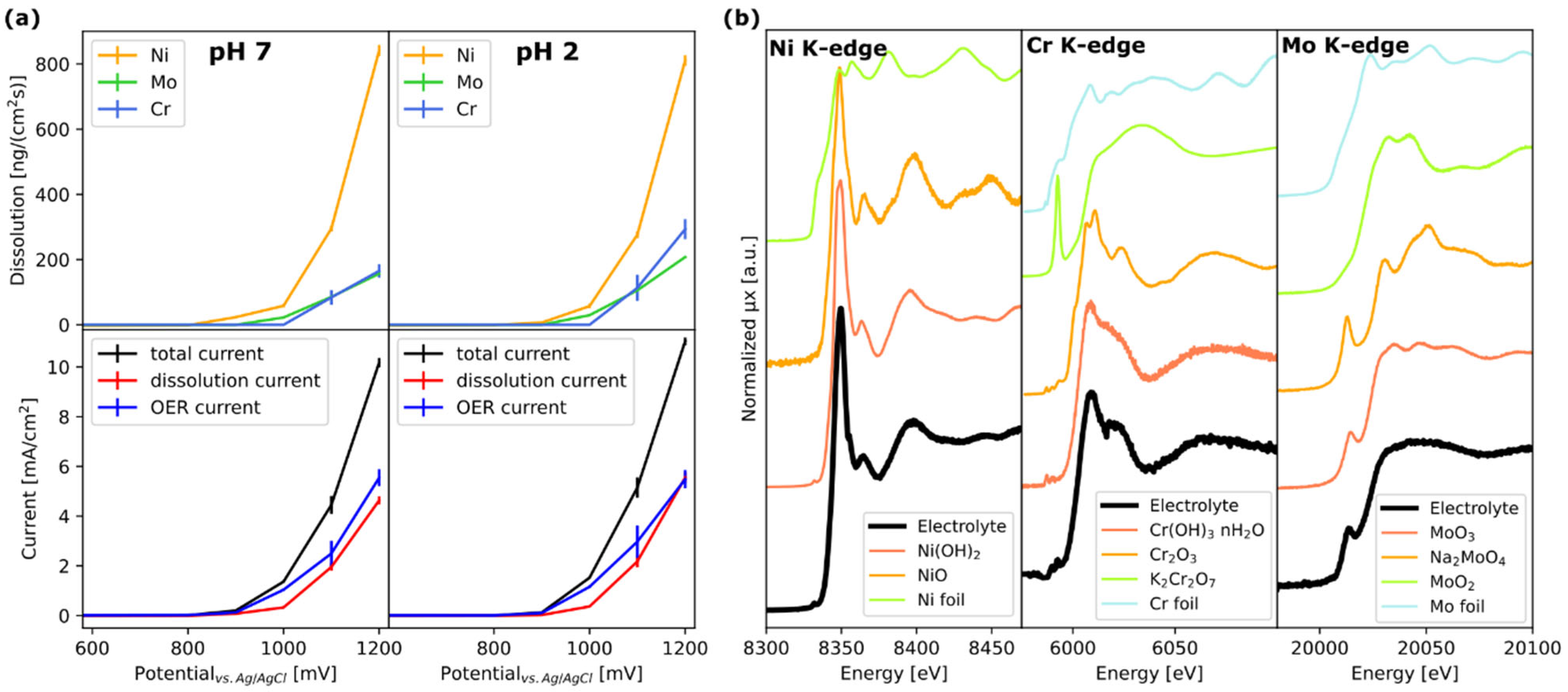

- Larsson, A.; Grespi, A.; Abbondanza, G.; Eidhagen, J.; Gajdek, D.; Simonov, K.; Yue, X.; Lienert, U.; Hegedüs, Z.; Jeromin, A.; et al. The oxygen evolution reaction drives passivity breakdown for Ni–Cr–Mo alloys. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2304621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, J. Synchrotron X-Ray Techniques for In Situ or Microscopic Study of Passive Films on Industrial Alloys: A Mini Review. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2025, 6, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040056

Pan J. Synchrotron X-Ray Techniques for In Situ or Microscopic Study of Passive Films on Industrial Alloys: A Mini Review. Corrosion and Materials Degradation. 2025; 6(4):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040056

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Jinshan. 2025. "Synchrotron X-Ray Techniques for In Situ or Microscopic Study of Passive Films on Industrial Alloys: A Mini Review" Corrosion and Materials Degradation 6, no. 4: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040056

APA StylePan, J. (2025). Synchrotron X-Ray Techniques for In Situ or Microscopic Study of Passive Films on Industrial Alloys: A Mini Review. Corrosion and Materials Degradation, 6(4), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmd6040056