1. Introduction

Clay is a common type of layered silicate mineral, consisting of alternating arrayed layers of silicon-oxygen tetrahedra and aluminum-oxygen octahedra interconnected by hydrogen bonds or other weaker van der Waals forces [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. As we know, the characteristics of the clay/electrolyte interface play a critical role in numerous processes of various applications [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The surface of clay minerals is typically negatively charged, forming a double-layer structure with ions in the electrolyte solution. At the clay/electrolyte interface, water molecules and ions can enter and be adsorbed within the interlayer spaces of clay minerals, leading to the expansion or contraction of the clay [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Some ions undergo non-specific adsorption with the clay surface through electrostatic attraction, while others form specific adsorption at active surface sites, even resulting in chemical bonding [

16,

17,

18]. In the field of petroleum extraction, waterflooding is a commonly used EOR technique, where the adsorption and ion exchange behavior of clay minerals significantly influence the stability of the reservoir and the flow characteristics of the fluids during the waterflooding process. Studies have shown that the interaction between electrolyte solutions and clay minerals during waterflooding can affect the efficiency of the process, particularly by altering the surface properties and dispersion characteristics of the clay minerals. This can effectively improve the mobility of water, thereby enhancing the oil recovery from the reservoir.

It has been reported that the interaction between clay minerals and electrolyte solutions was significantly influenced by layered structure, surface charge, and porosity of clay minerals, as well as the concentration and ion types in electrolyte solutions. For example, it has been found that the exchange of cations with different valence states in montmorillonite exhibits distinct selectivity, in which divalent cations typically exhibit more stable associations formed within the interlayers of clay minerals compared to monovalent cation [

19,

20,

21]. Some researchers highlight the significance of hydrated ions in the interactions between clay minerals and electrolyte solutions, revealing the crucial role of hydration degree and ionic radius in the ion exchange process [

22,

23]. It has been revealed that elevated temperatures accelerate mineral dissolution and cation migration, significantly altering the stability of mineral structures and their adsorption capacity [

24,

25,

26]. Despite some advance in interaction mechanisms between clay minerals and electrolyte solutions, the specific processes and influencing factors of these mechanisms still require further in-depth study. Especially, the electrolyte solutions commonly used are mixed electrolyte solutions in petroleum extraction. Although there has been extensive research on the interaction between single ions and clay minerals, these studies predominantly rely on single experimental methods, lacking a multidimensional and systematic analysis [

27,

28,

29]. Further studies are needed to uncover the complex interaction mechanisms involved.

Herein, we investigated the adsorption behavior and thermodynamic properties of montmorillonite, illite, and kaolinite in different cationic solutions, for the first time combining adsorption isotherms and immersion enthalpy to provide a systematic quantitative comparison. The results showed that the adsorption capacity of all three clay minerals increases with the concentration of cations, with montmorillonite exhibiting the highest adsorption capacity. The adsorption capacity of the different cations follows the order: K+ > Na+ > Ca2+ > Mg2+. Additionally, cation adsorption leads to significant changes in the surface morphology and surface groups of the clay minerals, primarily owing to that the strong interactions between the cations and the mineral surfaces altered the crystal morphology of the minerals. These quantitative principles provide a theoretical foundation for interface optimization in engineering processes such as oil and gas development and environmental remediation.

3. Results and Discussion

Montmorillonite, illite, and kaolinite are typical clay minerals commonly found in oil reservoirs, each possessing distinct interlayer structures and surface characteristics. Their interactions with electrolyte solutions play a significant role in influencing the oil displacement efficiency during waterflooding processes. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to analyze the distinct microstructural characteristics of montmorillonite, illite and kaolinite, revealing their unique crystalline structures. As shown in

Figure 1, montmorillonite exhibits a layered, plate-like morphology with noticeable interlayer spaces. The plates are stacked together through face-to-face, face-to-edge, and edge-to-edge interactions, with the average particle size ranging from 1~10 μm. Illite exhibits relatively smaller and more aggregated particles with a rougher surface and appears less stratified compared to montmorillonite. The particles display an irregular, angular sheet-like and fine flaky crystalline form, with individual layer thicknesses ranging from approximately 50~100 nm. Kaolinite demonstrates a well-organized plate-like structure with tightly stacked layers and minimal interlayer spacing, resulting in a densely packed arrangement. The observed smooth and flat surfaces of the plates suggest a structurally stable mineral, with the diameter ranges from approximately 1~3 μm. As shown in

Table S1, montmorillonite, kaolinite, and illite are all aluminosilicate minerals. Montmorillonite contains small amounts of Na

+ and Mg

2+, indicating it is a sodium-based montmorillonite. Kaolinite is a pure aluminosilicate, while illite contains small amounts of K

+.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was employed to further characterize the structure and composition of the three types of clay minerals (

Figure 2a). The standard reference cards (PDF) were used for comparison analysis to confirm the diffraction peaks of each mineral and calibrate the experimental data. By comparing with the standard reference cards (PDF#00-029-1498, PDF#00-006-0221, PDF#00-026-0911), the main characteristic diffraction peaks of montmorillonite, kaolinite, and illite were identified, and their positions were marked on the XRD pattern. The standard cards provide precise crystallographic information, ensuring the accurate identification of the mineral compositions. The XRD pattern of montmorillonite shows relatively broad diffraction peaks, with the characteristic diffraction peak of the (001) facet at 7.1° (

d001 = 12.44 Å), indicating that montmorillonite has a large interlayer spacing and a certain degree of structural disorder (JCPDS 00-029-1498). In contrast, the XRD patterns of illite and kaolinite exhibit strong and distinct diffraction peaks, reflecting their smaller interlayer spacing and higher degree of crystallinity. The dioctahedral structure of kaolinite is demonstrated by its characteristic diffraction peaks at 12.3° and 24.9°, corresponding to the (001) and (002) facets (

d001 = 7.19 Å;

d002 = 3.57 Å), respectively (JCPDS 00-006-0221), while the characteristic diffraction peaks of illite at 8.8° (

d001 = 10.04 Å) and 26.7° (

d003 = 3.34 Å) suggest its trioctahedral layered structure (JCPDS 00-026-0911). Although the XRD patterns predominantly correspond to the analyzed clay minerals, some minor peaks were observed, which may correspond to trace impurities such as quartz or feldspar.

Furthermore, the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) was used to analyze the molecular structures and chemical compositions of clay minerals (

Figure 2b). Montmorillonite and illite show broad absorption bands around 3620 cm

−1 for sharp O-H stretching vibrations, indicating the presence of hydroxyl groups, which are typically associated with interlayer water or surface hydroxyl groups. Kaolinite is distinctive for multiple sharp O-H stretching bands around 3695, 3650, 3620, and 3600 cm

−1, indicating its well-ordered structure and inner-surface hydroxyl groups. Additionally, the observed 1000–1100 cm

−1 region should be ascribed to Si-O stretching vibrations, while the Al-O-H bending vibration appeared at approximately 910 cm

−1 for the three clay minerals.

Table S2 presents the specific surface area and average pore size data of different clay minerals obtained through N

2-BET analysis. The results indicate that illite exhibits the highest specific surface area (28.933 m

2/g), followed by montmorillonite (12.105 m

2/g) and kaolinite (12.434 m

2/g). In contrast, montmorillonite has the largest average pore size (18.423 nm), while illite and kaolinite have average pore sizes of 14.811 nm and 16.395 nm, respectively. In order to investigate the swelling properties of different clay minerals, we measured the swelling capacity of three clay minerals. The results show that montmorillonite has the highest swelling capacity, approximately 52.3 mL/g, indicating strong hydration due to the readily available sodium ions between the layers. Illite exhibits a swelling capacity of 21.6 mL/g, which is lower than that of sodium montmorillonite, as potassium ions are less effective at promoting hydration. Pure kaolinite has the lowest swelling capacity, only about 7.2 mL/g, suggesting minimal swelling behavior, likely due to its stable structure and the lack of ions capable of significant hydration between its layers. This indicates that the swelling behavior of clay minerals is heavily influenced by their ionic composition and structural characteristics. These results provide a foundation for further investigation into the adsorption properties of different clay minerals.

Previous studies have been reported that the adsorption capacity of clay minerals is mainly determined by their own characteristics, such as structure type, specific surface area, and surface charge. Cation exchange capacity (CEC) is an important parameter reflecting the adsorption capacity of clay minerals. Through the ammonium chloride-absolute ethanol method, the CEC values of montmorillonite, illite, and kaolinite were determined to be 72.23 ± 3.39 mmol·(100 g)

−1, 26 ± 2.17 mmol·(100 g)

−1, and 8.61 ± 0.72 mmol·(100 g)

−1, respectively. The adsorption of different metal ions on clay minerals is shown in

Figure 3. It can be observed that the equilibrium adsorption capacity of clay minerals for cations increases with the initial concentration of cations, which is primarily attributed to the dynamic equilibrium between the unsaturated active adsorption sites in clay and the cation concentration. The adsorption characteristics of clay minerals for different cations referred from the saturation adsorption values of these isotherms are summarized as follows: (1) For the same cation, the adsorption capacity of the three clay minerals follows the order: montmorillonite > illite > kaolinite; (2) For the same clay mineral, the adsorption capacity for cations is ranked as K

+ > Na

+ > Ca

2+ > Mg

2+. Clearly, the adsorption trends observed in the data align with the CEC results, suggesting that the adsorption capacity of clay minerals is closely related to their cation exchange capacity. This indicates that the adsorption behavior is largely driven by ion exchange processes. Montmorillonite, which contains sodium ions (Na

+) and has a higher CEC, demonstrates a stronger affinity for cations, particularly divalent ions such as Ca

2+ and Mg

2+. In contrast, illite, which contains potassium ions (K

+), exhibits a lower cation exchange capacity and, consequently, a weaker adsorption affinity for other cations. The presence of sodium and potassium ions in montmorillonite and illite further influences their ability to adsorb other cations through ion exchange, underscoring the significant role of ion exchange in the adsorption process.

To further analyze the adsorption data, the Langmuir adsorption model was applied to fit the experimental results and estimate the key parameters. The Langmuir adsorption model is expressed by the following equation:

where

qe is the amount of adsorbate adsorbed per unit mass of the adsorbent at equilibrium (units: mmol/g);

qmax is the maximum adsorption capacity (units: mmol/g), which represents the amount of adsorbate when the adsorption sites are fully saturated;

KL is the Langmuir constant (units: L/mmol), which indicates the affinity of the adsorbent for the adsorbate;

Ce is the concentration of the adsorbate in the solution at equilibrium (units: mmol/L).

The resulting parameters are presented in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4, and the experimental data were successfully fitted to the Langmuir adsorption model, with the Langmuir coefficient

R2 close to 1 for all cases, indicating a strong correlation and excellent agreement between the experimental data and the Langmuir isotherm. This suggests that the adsorption of metal cations on the clay minerals follows a monolayer adsorption process, where all the adsorption sites are equivalent and have the same adsorption affinity. Additionally, the fitted maximum adsorption capacity parameters (

qmax) were found to be generally consistent with the experimentally determined maximum adsorption capacities, further validating the reliability of the model. These results highlight the suitability of the Langmuir model in describing the adsorption behavior of clay minerals for metal cations.

The measured immersion enthalpies of clay minerals in pure water and different electrolyte solutions at 25 °C are listed in

Table 5. The immersion enthalpies of montmorillonite, illite, and kaolinite in pure water are 16.13 J/mol, 5.36 J/mol, and 9.92 J/mol, respectively. These results reflect the discrepancy in thermodynamic behavior of various minerals upon contact with water, which are mainly influenced by factors such as their surface properties and interlayer interactions. Montmorillonite has strong surface hydrophilicity, which can be evidenced by the lowest water contact angle among the three types of clay minerals (

Figures S1–S3). Additionally, the interlayer spacing of montmorillonite is relatively large, as evidenced by XRD characterization, which reveals a characteristic diffraction peak with a d

001 value of 1.26 nm. These characteristics endow montmorillonite with strong adsorption capacity and hydration ability for water molecules, resulting in intense interactions with water and the release of considerable heat. Although kaolinite exhibits some degree of hydrophilicity, its interlayer spacing (d

001 = 0.53 nm) is smaller than that of montmorillonite, resulting in relatively weaker water absorption and a lower immersion enthalpy. Illite has relatively poor hydrophilicity and a more compact structure, with an interlayer spacing of 0.79 nm, resulting in weak water adsorption. Consequently, the interaction between water and illite is minimal, making its immersion enthalpy the lowest among the three clay minerals.

Further investigation reveals that the contribution of cations to the immersion enthalpy of clay minerals varies and is influenced by the properties of the cations (e.g., ionic radius, charge, solvation characteristics). Among all cations, the K+ ion showed the highest immersion enthalpy, which can be ascribed to the moderate ionic radius of K+ ion, facilitating strong electrostatic attraction with the negatively charged interlayer of clay. Additionally, K+ ion has relatively low solvation energy, which allows its hydration shell to be more easily stripped away, enabling direct interaction with the negative charges in the clay interlayer and thereby releasing more energy. The immersion enthalpies of divalent cations are higher than that of Na+ ion but lower than that of K+ ion. This is because divalent cations exhibit stronger interactions with clay due to their higher charge density compared to monovalent cations. However, their stronger solvation makes it more difficult to remove their hydration shell compared to K+, resulting in slightly lower immersion enthalpies. Na+ ion gave the lowest immersion enthalpy, which is due to its smaller ionic radius and higher solvation energy, making its hydration shell harder to remove, and thereby suppressing its direct interaction with clay.

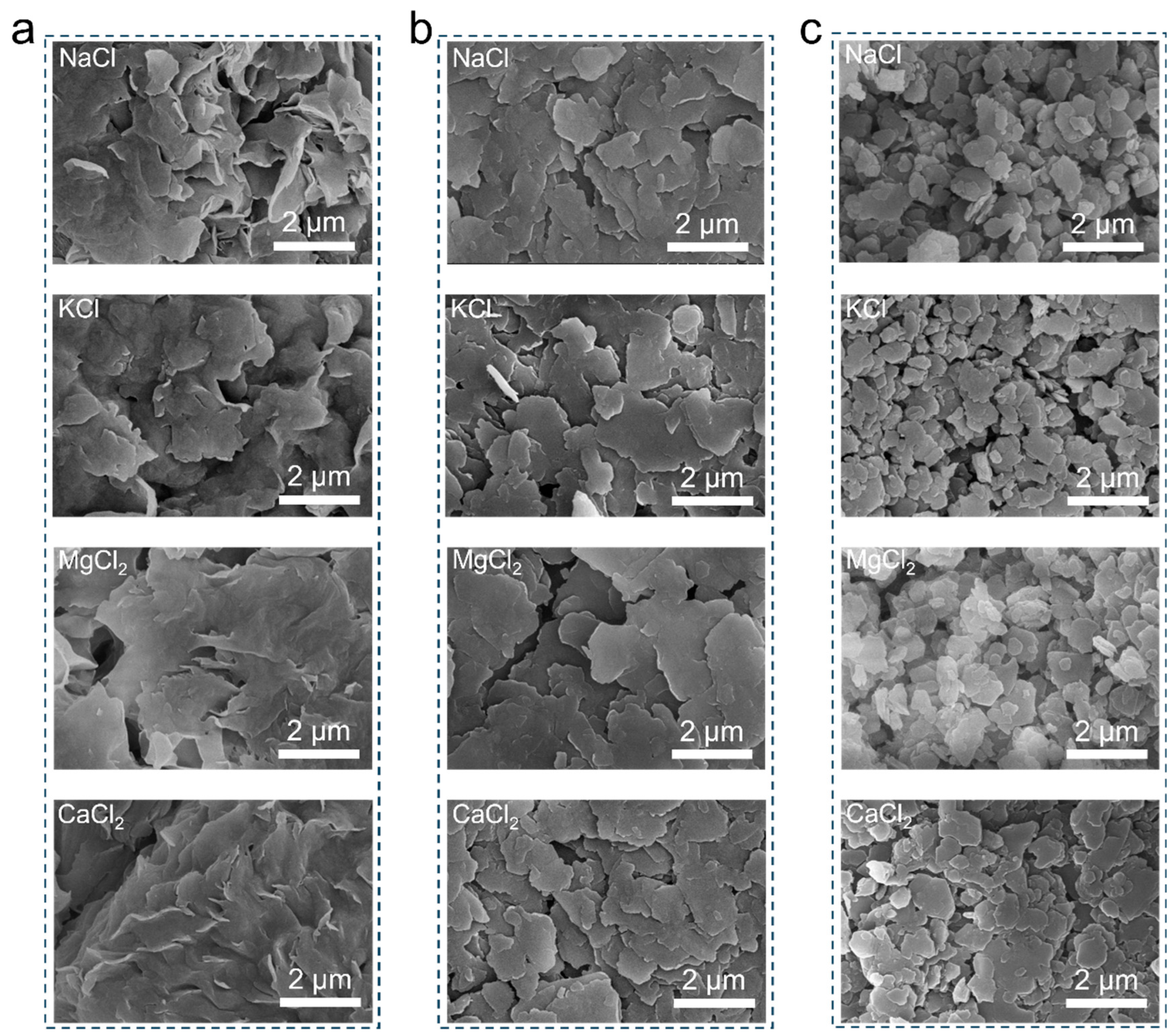

The surface morphology of clay minerals underwent significant changes after being immersed in electrolyte solutions. As shown in

Figure 4a, montmorillonite exhibited a clear difference in surface morphology before and after adsorption of different cations. Before adsorption, montmorillonite appeared as a flake aggregate with relatively flat plates, while the plates presented a disordered stacking pattern with the increased curvature after adsorption. Similarly to montmorillonite, illite also underwent a transformation from an aggregated structure to a disordered stack of plate-like structures after cation adsorption. As shown in

Figure 4b, kaolinite experienced a reduction in plate-like structures to varying degrees after the adsorption of cations, with a clear increase in fragmentation. These above structural changes are mainly due to the fact that the increased net charge on the clay aggregates leads to repulsive interactions between the plates in the aggregate after cation adsorption, causing them to become more dispersed and stacked in a more disordered manner. Additionally, cations can strongly interact with the surface structure of the minerals, resulting in the detachment of layers or the disruption of the crystal morphology, in which the effect extent follows the order: K

+ > Na

+ > Mg

2+ > Ca

2+. This is in the reverse order of the hydrated ionic radius of the cations. In principle, a higher cation charge density enhances the electrostatic attraction to the negatively charged clay surface. However, in aqueous suspensions the measured exchange enthalpy is governed by a competition between clay–cation electrostatics and the energy required to disrupt the cation hydration shell. Therefore, the observed enthalpy sequence suggests that the weaker hydration and lower desolvation penalty of K

+ and Na

+ outweigh the stronger but more highly hydrated divalent cations under the present conditions. To further elucidate the influence of different electrolyte environments on clay surface charge, we measured the zeta potentials of montmorillonite, illite, and kaolinite in pure water as well as in 100 mmol/L NaCl, KCl, MgCl

2, and CaCl

2 solutions (

Figure S4). The results reveal clear and systematic trends governed by both cation valence and hydration characteristics. Montmorillonite, which carries the highest layer charge among the three clays, shows the strongest response to electrolyte addition. Its zeta potential increases monotonically from a highly negative value in pure water to progressively less negative values in monovalent (Na

+, K

+) and then divalent (Mg

2+, Ca

2+) electrolyte solutions. This trend reflects the efficient charge screening and electrostatic neutralization provided by higher-valence cations. In contrast, illite and kaolinite exhibit much lower intrinsic surface charge, and therefore their zeta potentials change within a narrower range. Nevertheless, both minerals follow the same hierarchy: Na

+ produces only slight shifts toward less negative values, K

+ induces a marked increase resulting in a positive zeta potential, and Mg

2+ and Ca

2+ lead to further enhancement. Ca

2+ consistently generates the most positive values, consistent with its lower hydration energy and stronger affinity for clay surfaces relative to Mg

2+.

Figure 5 presented the FT-IR spectra of montmorillonite after the adsorption of cations. Compared with that of pristine samples, there are distinct differences in relative peak intensities: (1) A slight decrease in the relative intensity of the O-H stretching vibration peak of structural water at 3640 cm

−1 after adsorption, suggesting the binding of cations to the structural O-H of clay reduces the amount of structural O-H. The order of decrease in intensity among different cations is K

+ > Na

+ > Mg

2+ > Ca

2+, which is basically consistent with the amount of cation adsorption; (2) An increase in the relative intensity of the O-H stretching vibration absorption peak (3435 cm

−1) of water molecules adsorbed on montmorillonite, and a corresponding enhancement of the bending vibration absorption peak at 1635 cm

−1, implying the large amount of water bound to the cations adsorbed on montmorillonite. The enhancement order among different cations is Mg

2+ > Ca

2+ > Na

+ > K

+, which is consistent with the ability of binding water molecules; (3) A significant decrease in the relative intensity of the Si-O stretching vibration peak (1020 cm

−1) and Al-OH bending vibration peak (937 cm

−1), indicating that the interaction between cations and montmorillonite alters the relative quantities of functional groups on montmorillonite. Similarly to montmorillonite, the absorption peaks for structural water in illite and kaolinite decreased in intensity after cation adsorption, while the absorption peaks for adsorbed water increased significantly. The Si-O bending vibration peak and Al-OH bending vibration peak also showed a notable decrease. However, compared to montmorillonite, the change in the absorption peaks of the two samples is less pronounced owing to its weaker cation adsorption capacity.