1. Introduction

Palm oil (

Elaeis guineensis) is one of the most widely used vegetable oils in the world, extracted from the ripened mesocarp of the oil palm fruit. This ancient tropical plant originates from West Africa and has been utilized for centuries as both food and medicine [

1]. Rich in palmitic acid,

-carotene, and vitamin E, palm oil can be fractionated into liquid palm olein and solid palm stearin, diversifying its applications [

1,

2]. Historically, palm oil played a significant role in the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans. It was included in food rations for enslaved Africans during their forced displacement to the Americas, but its future as a global commodity was consolidated by the increase in demand in Europe [

2], as shown in

Figure 1. Over time, it became a key component in food production, cosmetics, biodiesel, and various industrial applications. Initially embedded in religious and communal life, palm oil’s traditional uses have since become commodified on a global scale, often to the detriment of the communities that preserved them. This tension between industrial demand and cultural heritage highlights the complex interplay between economic growth and social resilience. This commodification shifted palm oil from a communal product of a sacred nature in West African societies, where it was tied to rituals and medicinal uses, to a global commodity that drives environmental degradation, deforestation, and social inequalities [

3]. Scholars on cultural appropriation argue that traditional plant products often become decoupled from their cultural contexts in global trade systems, marginalizing the communities of origin while creating wealth elsewhere [

4,

5]. Studies on global trade impacts highlight how demand for palm oil in Europe and Asia undermined traditional stewardship systems and intensified inequalities in producer countries [

6,

7,

8].

European demand surged after the abolition of the enslaved Africans trade (post-1807), with exports rising from 0.8 kt in 1815 to 20 kt by 1840. During the Industrial Revolution, palm oil became a key ingredient in soaps, lubricants, and candles, replacing whale oil. Plantation systems in British Malaya and the Congo expanded supply in the early 20th century. Globally, production grew from 2 Mt in 1970 to 80 Mt by 2020, while European imports peaked at 8.3 Mt in 2020 before declining to 2.8 Mt by 2024 due to biofuel regulation changes [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Five countries lead global palm oil production today: Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Colombia, and Nigeria. Among oil-producing crops, the oil palm tree stands out for its exceptional efficiency, yielding the highest amount of oil per unit of cultivated land, with an annual output of approximately 76.26 million metric tons (MT) in 2023/2024 [

1,

14]. Over the last two decades, worldwide production has steadily expanded, representing nearly one-third of the 220 million tons of vegetable oil produced globally [

15]. Indonesia and Malaysia dominate the industry, contributing 85% of the total supply, while Thailand, Colombia, Nigeria, and Ecuador also play important roles. In 2018, around 35% of the palm oil imported by Europe was used in food, animal feed, and industrial sectors, including cosmetics. However, despite its widespread application, palm oil remains a subject of intense debate, particularly concerning its health effects, given its high saturated fat content, which has been linked to cardiovascular disease, as well as the environmental challenges associated with large-scale cultivation [

13,

16,

17,

18,

19].

In comparison, Brazil currently ranks 10th globally in palm oil production, with an estimated output of 570,000 metric tons (MT) in 2022/2023, marking a 4% increase (20,000 MT) over the previous year [

20,

21]. The total harvested area is estimated at 190,000 hectares, reflecting a 3% annual expansion [

20], with a national average yield estimated at 3.0 mt/ha. This national production is geographically concentrated and defined by two contrasting trends: The state of Pará is the dominant production hub, accounting for 82% of the total national production in 2021. This region has experienced rapid growth, with the harvested area increasing by over 200% in the last decade, expanding from 54,000 to 189,000 hectares [

20,

22]. Furthermore, a new frontier for industrial palm oil production is emerging in the Amazonian state of Roraima [

23], though current data on this expansion remains scant. Conversely, Bahia, historically the other main producing state (contributing 16% of the total production in 2021), has seen a significant decline in acreage, which dropped from 54,000 to 13,000 hectares over the last six years [

20].

In Brazil, palm oil’s significance transcends economic value. Known locally as

azeite de dendê, the term “

dendê” derives from the Kimbundu word

ndendê, meaning “oil” or “to drip” [

24]. In Bahia,

azeite de dendê represents not only a culinary staple but also a symbol of historical memory and sensory heritage. The distinct aroma and flavor of

azeite de dendê transcend religious, racial, and social boundaries, forming an integral part of Bahian culinary traditions and everyday life.

Unlike the large-scale, agroindustrial monocultures found in other palm oil-producing regions, Bahia’s palm oil production remains rooted in a biodiverse cultural landscape. In contrast to the Brazilian Amazon, where state-sponsored initiatives since 2010 have promoted industrial palm oil cultivation for biodiesel and economic development [

25], Bahia’s

azeite de dendê is cultivated through traditional methods passed down over generations. Recognizing its historical importance, Bahia’s Secretary of Culture and Tourism officially designated the region as the “

dendê Coast” (

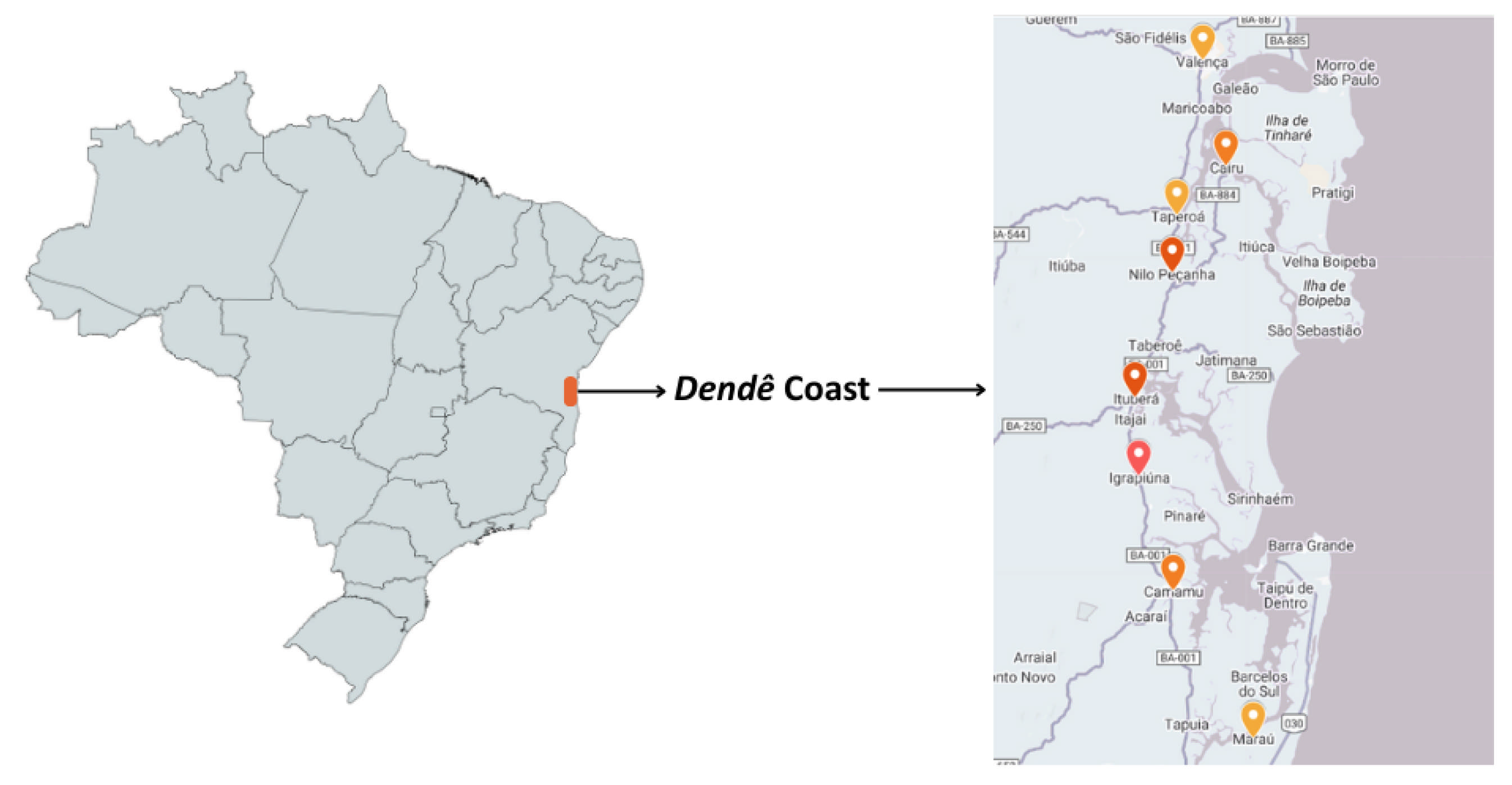

Costa do dendê) in 1993,

Figure 2, reinforcing its deep ties to Afro-Brazilian heritage [

26,

27]. However, despite this acknowledgement, Bahia’s traditional palm oil economy and culture has long been marginalised, receiving little attention from colonial authorities or modern development programs [

25].

Palm oil was introduced to Brazil during the colonial period, becoming essential to Afro-Brazilian cuisine and religious practices. Its vibrant color, rich flavor, and unmistakable aroma define

comidas de azeite, a category of dishes that have as its characteristic mark the rich flavour of palm oil like

acarajé,

vatapá and

moqueca baiana, which survived Portuguese influences and reflect cultural resilience by preserving African culinary traditions under colonial pressures. This resilience is expressed in how these foods became symbols of Afro-Brazilian identity and continuity despite centuries of marginalization [

28,

29]. Beyond its economic and culinary value,

azeite de dendê carries cultural and symbolic significance. The preparation and consumption of

comidas de azeite are embedded in ritual, tradition, and identity, making palm oil a vital component of Bahia’s intangible heritage [

30]. Although not formally listed by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage, these practices meet its criteria: they are transmitted across generations, rooted in communal practices, and hold symbolic value. Oral traditions, festivals, and the transmission of culinary knowledge from elders to younger generations demonstrate how these cultural practices fulfill UNESCO’s definition. They are deeply embedded in Afro-Brazilian cultural life and sustain identity and community cohesion [

31].

Acarajé, for instance, was documented in the Vilhena letters 200 years ago as a street food delicacy in Salvador and has been closely linked to Candomblé religious practices since the early 19th century [

28].

“It is remarkable to see that from the most opulent houses of this city, where major contracts and negotiations take place, eight, ten, or more Black men and women go out to sell on the streets, calling out the most insignificant and humble goods: various kinds of delicacies such as mocotós, cow’s feet, carurus, vatapás, porridge, pamonha, canjica (that is, corn puddings), acaçá, acarajé, ubobó, coconut rice, coconut beans, angu, rice sponge cake, corn sponge cake, sugarcane rolls, and burnt sugar sweets, eight for a vintém, and endless kinds of sweets—many of them clean enough to be used as emetics; and what is even more scandalous, a dirty water made with honey and certain mixtures, called aloá, which serves as lemonade for the Black population.”—Luis Dos Santos Vilhena [

32]

Though closely tied to Afro-Brazilian culture and religions such as Yoruba and Candomblé, palm oil’s significance extends far beyond these religious contexts, permeating the collective identity of Bahia. Introduced as part of colonial trade networks, palm oil became an important economic commodity during the transatlantic enslaved Africans trade. On enslaved Africans ships during the Middle Passage, it was used to nourish captives and to “make them look smooth, sleek, and young” before being sold at auction, as noted in an early 18th-century account [

33]. By the 18th century, commercial networks were importing palm oil in bulk from West and Central Africa into Bahia, alongside textiles and kola nuts, embedding it as a foundational element in Afro-Brazilian culinary, aesthetic, and religious practices [

3]. As transatlantic trade declined in the late 19th century, demand for locally produced palm oil increased, consolidating Bahia’s regional

dendê cultures and markets. Initially an economic product during colonization, palm oil gradually replaced peanut oil in the African-inspired culinary traditions practiced by enslaved Africans people in Brazil. Over centuries, its role expanded beyond food and religion to encompass industrial, economic, social, and cultural dimensions.

Bahian cuisine is not merely a collection of recipes; it reflects the historical processes of resistance, adaptation, and cultural negotiation that define Afro-Brazilian identity [

29]. The sensory experience of its flavours, textures, and aromas embodies the legacy of the African diaspora, maintaining ancestral ties through food and ritualistic preparation. This symbolic power is also evident in the

Baianas do Acarajé, street vendors who have historically played a matriarchal role in preserving and transmitting culinary traditions across generations. Their iconic

tabuleiros are not just food displays or market stalls [

30]; they are living, dynamic expressions of Bahian culture. These stands serve as showcases of culinary tradition, where every interaction with customers becomes an opportunity to highlight the richness and resilience of Bahian heritage. More than just a tourist symbol, the

baianas and their

tabuleiros act as a bridge between culture as written in books and culture lived and experienced, passed down through generations of Bahians.

This article argues that Bahia’s palm oil heritage embodies a multifaceted heritage, spanning religious, economic, ecological, and cultural dimensions, that remains under-recognized and vulnerable. Drawing from UNESCO’s framework of intangible cultural heritage, the study offers evidence of how these practices are transmitted across generations and explores the consequences of their neglect. According to UNESCO, intangible cultural heritage includes traditions, social practices, and knowledge systems inherited from ancestors and passed down through generations. These cultural expressions are vital for sustaining diversity in the face of globalization. In Bahia, this is reflected in traditions such as the preparation of

comidas de azeite and dendê-based ritual foods; social practices including the Lavagem do Bonfim procession and the offerings at the Festa de Iemanjá; and knowledge systems such as ethnobotanical cultivation techniques and low-waste compounding of local aromatics. Beyond the tangible manifestations of such traditions, their value lies in the inter-generational knowledge and skills they embody [

31].

Despite its historical and cultural significance, Bahia’s traditional palm oil as a heritage component is under threat. The expansion of agroindustrial palm oil production in the Amazon has shifted focus and resources away from Bahia’s long-standing production systems, further marginalizing traditional

dendezeiros. Additionally, deforestation, declining production, and industrialization pose serious risks to the biodiversity and sustainability of Bahia’s palm oil landscapes. While policymakers often prioritize large-scale monocultures, they overlook the complex agroecological knowledge and sustainable practices that have defined Bahia’s palm oil economy for centuries [

25]. This paper argues that the critical failure to protect the entire

dendê production system (from cultivation to consumption) risks losing a vital, proven blueprint for sustainability rooted in Afro-Brazilian cultural continuity.

Central to this study is the argument that the marginalization of Afro-Brazilian traditions threatens not only cultural vitality, but also a proven, place-based model for sustainable palm oil production. This culture has been preserved by people who are fragile and marginalized in society. Historically, the transmission of these practices across generations is demonstrated primarily through the matriarchal culinary lineage and the maintenance of ritual foodways by the Baianas do Acarajé, since they have been one of the main vehicles of safeguarding of these practices. This paper explores how we can learn from ancestral knowledge and practices around the palm oil and their communities to help us solve modern industrial problems, and, still, safeguard these practices from cultural erosion.

Building on this premise, the paper advances three core contributions. First, it analyzes the environmental and social performance of artisanal practices relative to industrial operations, highlighting resource efficiency, circular uses of by-products, and community livelihoods. Second, it proposes a transferable framework that links these heritage domains to concrete sustainability design criteria and governance levers, showing how place-based knowledge can inform low-impact value chains. Third, it outlines actionable pathways for policy and industry, including procurement guidelines that privilege community-produced oils, partnership models that ensure fair remuneration, and indicators to monitor cultural vitality and ecological outcomes. Together, these contributions position local communities not only as heritage holders but as co-designers of solutions to contemporary sustainability challenges.

2. Methodology

The present study adopts an interdisciplinary research design, which started with collaborative group discussions to integrate diverse perspectives on the complex historical, ecological, and cultural dimensions of Bahia’s dendê heritage. The main goal of these initial discussions was to harmonize and equalize disciplinary approaches to address the two core research questions: “How can ancestral knowledge and practices be leveraged to solve modern industrial sustainability problems?” and “How can this critical heritage be safeguarded from cultural erosion?”. Specifically, the discussions focused on defining integrated research guidelines by synthesizing methodologies from anthropology, ethnography, geography, heritage sciences, and engineering.

Following the establishment of a unified argument and research guidelines, the study proceeded with a systematic literature review and archival analysis. This phase involved reviewing extensive academic literature, non-academic sources, historical documents, and official records to firmly establish the socio-historical and cultural context for the study. Based on the non-academic sources, key stakeholders were systematically identified, filtered, and subsequently engaged.

Primary qualitative data was gathered through dedicated field trips to Salvador, Bahia, in January 2025, supplemented by online interviews, yielding rich qualitative data, including recorded videos and audios. This qualitative approach was designed by adapting structured methods from sensory panel assessments, commonly used in flavor and perfume analysis, and tailoring them to the context of cultural heritage and social ethnography. The interviews were carefully structured to elicit detailed qualitative measures: personal history, memories, knowledge, community participation, sensorial analysis of dendê (flavor and aroma), and point of view regarding the crisis facing the industry.

An iterative process between the literature review and stakeholder engagement was established, continuously guided by interdisciplinary group discussions. Concurrently, the technical expertise of the co-authors was integrated, primarily through quantitative data analysis and synthesis to evaluate the environmental and social performance of the artisanal systems. This technical evaluation included calculating yield estimates for polyculture systems and analyzing comparative data on resource efficiency and ecological resilience, such as observed microbial diversity gains in agroforestry models.

A key element of this technical rigor involved applying fundamental engineering principles, such as the Material Balance concept, to quantify the efficiency of ancestral production methods. The mass balance, rooted in the conservation of mass, tracks the input and output of materials in a system to ensure the total mass remains constant. In the most general sense, any balance equation for a conserved quantity is defined in Equation (

1) [

34].

The conservation of mass in any process is the fundamental indicator in thermodynamic analysis. The mass balance equation can be defined as follows:

where m and

are the mass and mass flow rate, respectively, subscripts

i and

e are the inlet and outlet flow conditions, and subscript

is the control volume.

The conservation of mass is a fundamental indicator in thermodynamic analysis. This simple engineering concept, when associated with available ecological and biological data from the literature, was deployed (as detailed in

Section 6) to quantitatively illustrate the productivity and comparative potential of the ancestral production methods against modern industrial processes.

The definitive strength of this investigation lies in its explicit, intentionally designed collaborative process, a necessity imposed by the research complexity, which effectively demolishes the disciplinary silos common in complex sustainability studies. Critical to this rigor was the implementation of sequential data validation. The ethnographic findings were not treated in isolation, but served as the qualitative hypotheses driving the technical analysis (e.g., the

Baianas’ concerns over fading aroma became the impetus to analyze how industrial processing alters oil characteristics). Conversely, technical data proving the viability and efficiency of polyculture systems was instrumental in validating the sustainability claims rooted in historical and cultural research. This robust, integrated methodology (

Figure 3), formalized through a collaborative writing and editing process that mirrors the inclusive development strategies the paper advocates, guarantees that all collected data forms are coherently integrated and synthesized. The result is a holistic analysis that is simultaneously deeply rooted in Afro-Brazilian cultural context and analytically rigorous in its derived policy recommendations.

3. Palm Oil: Origins and Global Importance

Archaeological findings indicate that as early as 5000 BCE, palm oil was a staple in parts of West and Central Africa, with evidence suggesting it was both cultivated and integrated into local diets as a cooking fat, as well as used in ceremonial and medicinal contexts [

35]. Far from being imposed by colonial trade, palm oil already held deep cultural and nutritional significance across African societies before it entered transatlantic commerce [

33].

The Industrial Revolution marked a turning point, establishing palm oil’s role in global commerce due to its unique chemical properties. Its high content of saturated fats gives it oxidative stability, making it resistant to rancidity and ideal for soap, lubricants, and detergents [

36]. These attributes, combined with its semi-solid state at room temperature, enabled it to replace animal fats like tallow in industrial processes and food manufacturing.

The commercial expansion of palm oil accelerated in the 19th century, with West African nations, particularly Ghana, becoming major exporters. By the 1880s, palm oil accounted for 75% of Ghana’s international trade. Plantations were later established in Central Africa, including the Belgian-controlled Congo, where Sir William Lever, founder of Unilever, set up large-scale production in 1935 [

36]. However, the industry’s global center shifted after World War II, when palm oil cultivation expanded dramatically in Southeast Asia, particularly in Malaysia and Indonesia. The development of high-yield hybrid varieties, such as

tenera (a cross between

dura and

pisifera palms), further increased production efficiency, making these two countries the dominant producers, supplying 85% of the world’s palm oil today.

Botanically, the oil palm tree belongs to the family

Arecaceae, and its fruits (

Figure 4) grow in dense, spiky bunches. Each fruit consists of a fibrous outer shell (exocarp), a pulp-rich mesocarp, and a hard inner kernel, as shown in

Figure 5. The mesocarp, which contains between 56% and 70% oil, is the primary source of crude palm oil (CPO), while the kernel yields palm kernel oil (PKO). Oil extraction methods vary, ranging from traditional hand-pressing techniques to large industrial-scale milling, with modern mechanical screw presses achieving 75–90% extraction efficiency [

37]. The introduction of the pollinating weevil (

Elaeidobius kamerunicus) to Southeast Asia in 1981 improved fruit set and contributed to higher oil yields.

Table 1 presents the varieties of palm oil trees based on morphological characteristics. It is important to note that

pisifera is considered a shell-less (bare) fruit, while

dura is more profitable when processing the kernel. However, in terms of oil extracted from the pulp,

tenera represents the ideal balance and is the most productive variety overall. Additionally, these three types (

dura,

tenera, and

pisifera) can exhibit variations in external traits such as the presence or absence of anthocyanins, carotenoids, and additional carpels.

As palm oil cultivation expanded, so did its economic significance. Today, it is the most produced vegetable oil globally, with annual production exceeding 76.26 million metric tons, making up nearly one-third of the world’s total vegetable oil output [

14]. The top-producing countries have transformed palm oil into a cornerstone of their agricultural economies [

16]. In Brazil, production is concentrated in the states of Pará and Bahia, where plantations are dominated by the

dura variety, which yields less oil than the high-performing

tenera hybrids cultivated in Asia. Although Brazil contributes only a small fraction to global production, palm oil assumes a distinct cultural and economic role in Bahia.

Azeite de dendê functions not merely as an agricultural product but as a central element in Afro-Brazilian culinary traditions and religious practices, forming a key component of the region’s cultural identity.

Approximately 90% of global production is used in food applications, including cooking oils, frying oils, processed foods, and margarine, while the remaining 10% is used in soap and oleochemical industries [

1]. Due to its unique fatty acid composition, palm oil is a preferred ingredient in food manufacturing, providing a 50:50 ratio of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. It is also naturally rich in

-carotene, vitamin E (600–1000 ppm), coenzyme Q10 (18–25 mg/kg), and sterols (325–365 mg/kg). In warm climates, palm oil is semi-solid and can be fractionated into two primary components [

40]:

Palm Olein—the liquid fraction, rich in unsaturated fatty acids, widely used for frying and cooking.

Palm Stearin—the solid fraction, rich in saturated fatty acids, used in margarine, shortening, and industrial applications

Despite its industrial importance, palm oil is at the center of heated debates concerning environmental sustainability and health concerns. Its large-scale cultivation has led to widespread deforestation, biodiversity loss, and greenhouse gas emissions, particularly in Southeast Asia [

25]. Studies indicate that as much as 30 million hectares are used for palm oil plantation. As plantations expand, tropical forests are cleared, threatening faunal diversity and ecosystem stability. Non-governmental organizations warn that this process is jeopardizing fragile environments in Malaysia, Indonesia, and other tropical regions [

37]. While 85% of global palm oil production is concentrated in Asia, Latin America, especially Brazil and Colombia, is emerging as a key frontier for expansion [

25].

In addition to environmental concerns, palm oil has faced scrutiny regarding human health impacts. In addition to environmental concerns, palm oil has faced scrutiny regarding human health impacts as reported in the literature [

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, palm oil remains a preferred option in many food industries due to its stability in frying and synergistic antioxidant properties, provided by

-carotene and tocotrienols [

1,

37]. Some manufacturers blend palm oil with other vegetable oils to optimize both nutritional and functional benefits.

While palm oil’s history is deeply intertwined with global trade and economic development, its future depends on balancing production with sustainability. As the world’s most produced vegetable oil, its cultivation presents both opportunities and challenges. Governments, environmental organizations, and industry leaders are working toward solutions that promote responsible sourcing, sustainable farming practices, and deforestation-free supply chains.

The rapid industrial expansion of palm oil has brought severe environmental and social consequences. Large-scale plantations in Southeast Asia have driven deforestation, biodiversity loss, and greenhouse gas emissions, and similar dynamics are emerging in parts of Latin America [

25]. Yet within this global context, traditional palm oil systems in Bahia stand in sharp contrast: they reflect centuries-old practices that sustain local ecosystems and embody cultural resilience. Crucially, the growing industrial importance of palm oil has overshadowed these cultural dimensions, marginalizing the communities who have maintained them and excluding them from broader conversations about sustainability and industry reform.

4. Palm Oil in Brazil: A Bridge from Africa

Dendê’s journey to Brazil is inseparable from the larger history of the transatlantic enslaved Africans trade, which forcibly brought nearly five million Africans to Brazil between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries [

41]. Enslaved Africans, primarily from the Yoruba-speaking regions of West Africa, brought not only their physical labor but also seeds, culinary knowledge, and religious traditions. This transfer of cultural practices ensured the preservation and transformation of Yoruba foodways in Brazil.

The Yoruba, Fon, and Bantu peoples, among others, carried not only their knowledge of palm oil cultivation and use but also the seeds of the Elaeis guineensis tree itself. While colonial authorities later encouraged the use of dendê as a cheap source of nutrition for enslaved Africans, palm oil was not an imposed foreign element. On the contrary, it was deeply rooted in the cultural, religious, and culinary traditions of West African societies long before their forced displacement. The transatlantic enslaved Africans trade did not introduce dendê as a new practice but rather transplanted it into a new ecosystem, where it became a vital tool of cultural preservation and survival. Historical evidence suggests that oil palms were growing in Bahia by at least the late 17th century, likely propagated by Afro-descendant communities who recognized its importance and actively cultivated it. In this way, the colonial system unintentionally reinforced the use of dendê, as enslaved Africans relied on familiar elements of their heritage to maintain identity, community, and resilience. The continued significance of dendê in Afro-Brazilian traditions today stands as a testament to this cultural continuity under oppression.

African oil palms had acclimatized along the Brazilian coast and became essential to both the culinary and religious landscapes, particularly along the

Costa do dendê [

25]. In the Baixo Sul region of Bahia, this unique, dense, and productive palm oil landscape stands as the only one of its kind outside its African homelands. As reconstructed by Castañeda (2022) [

42], the region’s historical, geographical, and political–ecological development shows that agroecological niches such as mangrove ecosystems provided ideal conditions for dendê to thrive. Yet, its success was not solely due to environmental suitability: human cultivation worked in synergy with animal dispersers, most notably vultures, which spread palm seeds and contributed to complex, biodiverse landscapes. Vultures, deeply significant in West African spirituality, together with the proliferation of palm groves, forged a sacred transatlantic and cosmological connection [

3,

24].

Despite the prominence of palm oil in West African cultures and early Atlantic economies, the botanical introduction of Elaeis guineensis to Brazil remains fragmentary and ambiguous. Historical records indicate that Portuguese colonial authorities attempted to cultivate oil-bearing palms in Brazil as early as the 1610s. However, it was not until 1699 that English privateer William Dampier documented the presence of African oil palms growing “plentifully” in Bahia. He referred to them as “Dendees”, derived from the Kimbundu term “dendê,” spoken in Angola. This suggests that dense palm groves had been established decades earlier, likely through Afro-descendant communities propagating the species.

Unlike sugarcane, which was introduced and cultivated primarily under the direction of Portuguese colonial authorities for export profits, dendê was largely maintained by Afro-descendant communities. enslaved Africans and free Africans planted, harvested, and processed palm oil, ensuring its survival and integration into the local food system. While Portuguese administrators initially showed little interest in its economic potential, focusing instead on sugarcane and tobacco, the Afro-Brazilian population continued to cultivate dendê for both culinary and religious purposes. By the 18th century, palm oil production was concentrated along the dendê Coast, a stretch of land south of Salvador where the tree thrived in the tropical climate. Despite its economic significance for local communities, colonial authorities did not develop large-scale plantations, allowing palm oil production to remain an autonomous Afro-Brazilian industry. By the 18th century, the dendê Coast had become a major center of manioc and palm oil production, although colonial authorities largely dismissed its economic potential.

The role of

dendê in Bahian cuisine is one of the most striking examples of African cultural retention in Brazil. Many of the dishes prepared with palm oil today closely resemble those made in West Africa, particularly in Yoruba and Fon traditions.

Acarajé,

Figure 6, a black-eyed pea fritter fried in

dendê, is perhaps the most iconic example. Other staple dishes such as

vatapá,

caruru, and

moqueca also owe their existence to African culinary traditions, with their use of

dendê providing a direct link to the foodways of West Africa, with one key adaptation:

acarajé in Bahia is exclusively fried in palm oil, whereas in Africa, peanut oil was sometimes used [

28].

Anthropologist Manuel Querino categorized Bahian food into two groups: those influenced by Portuguese traditions and those he termed “purely African,” which retained the form, constitution, and name of African dishes, predominantly of Yoruba origin [

28]. Many

dendê-based dishes fall into this second category, including:

Vatapá—a rich paste of bread, peanuts, dried shrimps and dendê.

Moqueca (

Figure 7)—a seafood stew flavored with coconut milk and

dendê.

Caruru—a thick okra-based dish.

The presence of dendê in these foods not only reflects the continuity of West African culinary techniques but also serves as a symbol of cultural resistance. While many other elements of Yoruba cuisine, such as amala (yam flour dough) or ewedu (jute leaf soup) were not preserved in the Bahian context, dendê provided a durable and adaptable thread through which displaced communities could maintain and transmit key aspects of their identity. In this way, dendê became more than an ingredient: it functioned as a conduit for cultural survival and cohesion under displacement and oppression.

Beyond food, dendê holds profound significance in Afro-Brazilian religious traditions. In Candomblé, palm oil is used in rituals, offerings, and liturgics ceremonies. It is an essential ingredient in ebós (ritual foods), and its deep red color symbolizes life force, energy, and religious power. The connection between dendê and Yoruba religious traditions is so strong that many rituals performed in Brazil today are nearly identical to those practiced in Nigeria and Benin, reinforcing the continuity of African religiosity across the Atlantic. Women have played a crucial role in maintaining the cultural and economic presence of dendê in Bahia.

The presence of dendê in Bahian daily life is most visible in the baianas de acarajé, street vendors dressed in traditional white clothing, selling acarajé, vatapá, and abará. These women not only preserved African culinary traditions but also created a space for economic independence in a society that marginalized Afro-Brazilian communities. Their culinary knowledge is passed down through generations, ensuring that traditional food preparation remains an act of cultural preservation and resistance.

Industrial Heritage of the Palm Oil

The process of extracting and producing palm oil in Bahia represents an important element of Brazil’s industrial heritage, encompassing both tangible and intangible cultural legacies. Unlike large-scale industrial systems developed in Southeast Asia, Bahian palm oil production evolved through a combination of traditional African techniques and locally adapted innovations. For centuries, the process relied on manual labor and small-scale extraction methods, such as the pilão (mortar and pestle), which were used to process palm fruit in bulk within Afro-descendant communities.

As demand for

azeite de dendê increased during the colonial and postcolonial periods, technological innovations like the

rodão (

Figure 8), an animal-powered mill inspired by Mediterranean olive oil presses, were introduced to Bahia. These mills dramatically boosted production capacity while maintaining reliance on community-based labor systems [

25]. The

rodão became a hallmark of regional economies, serving as a hybrid innovation that blended imported mechanical principles with Afro-Brazilian agricultural knowledge.

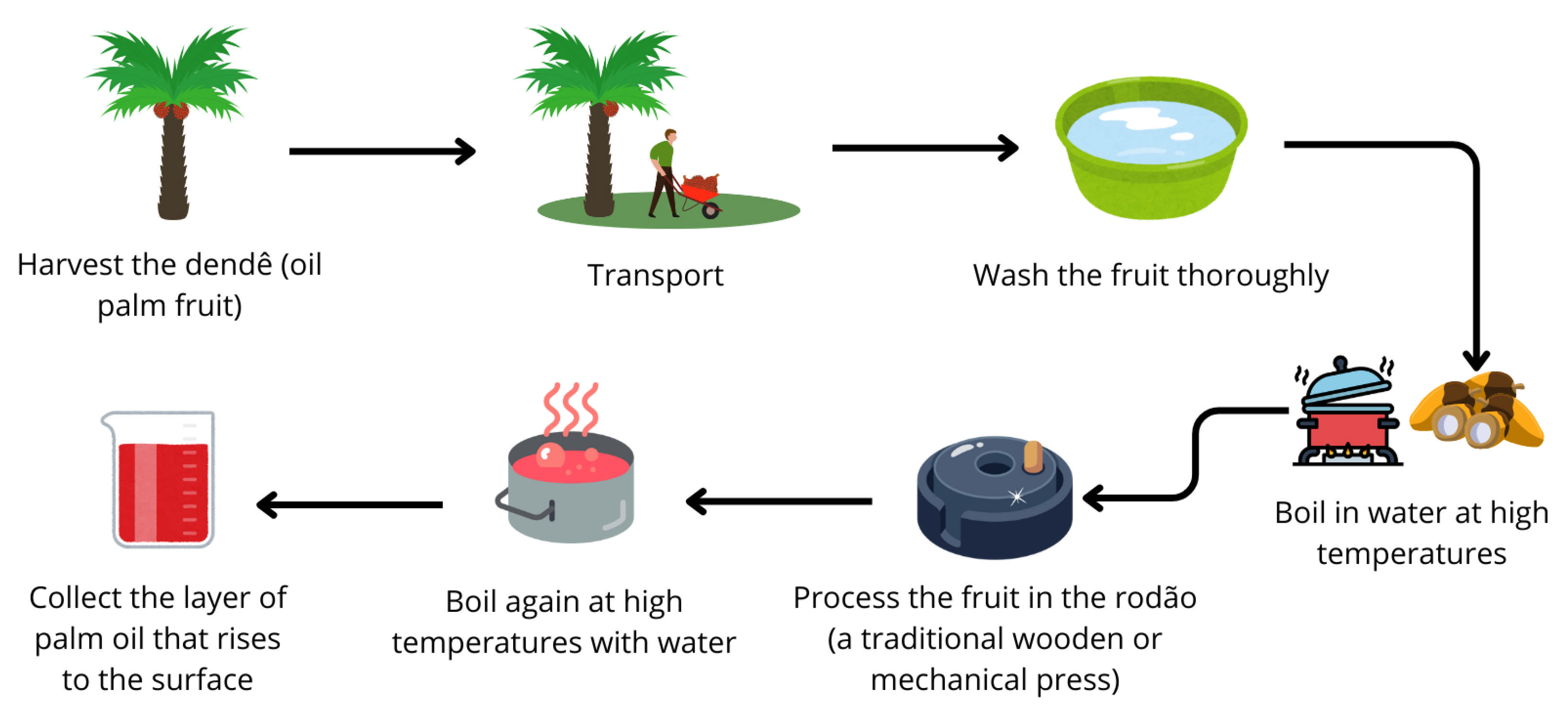

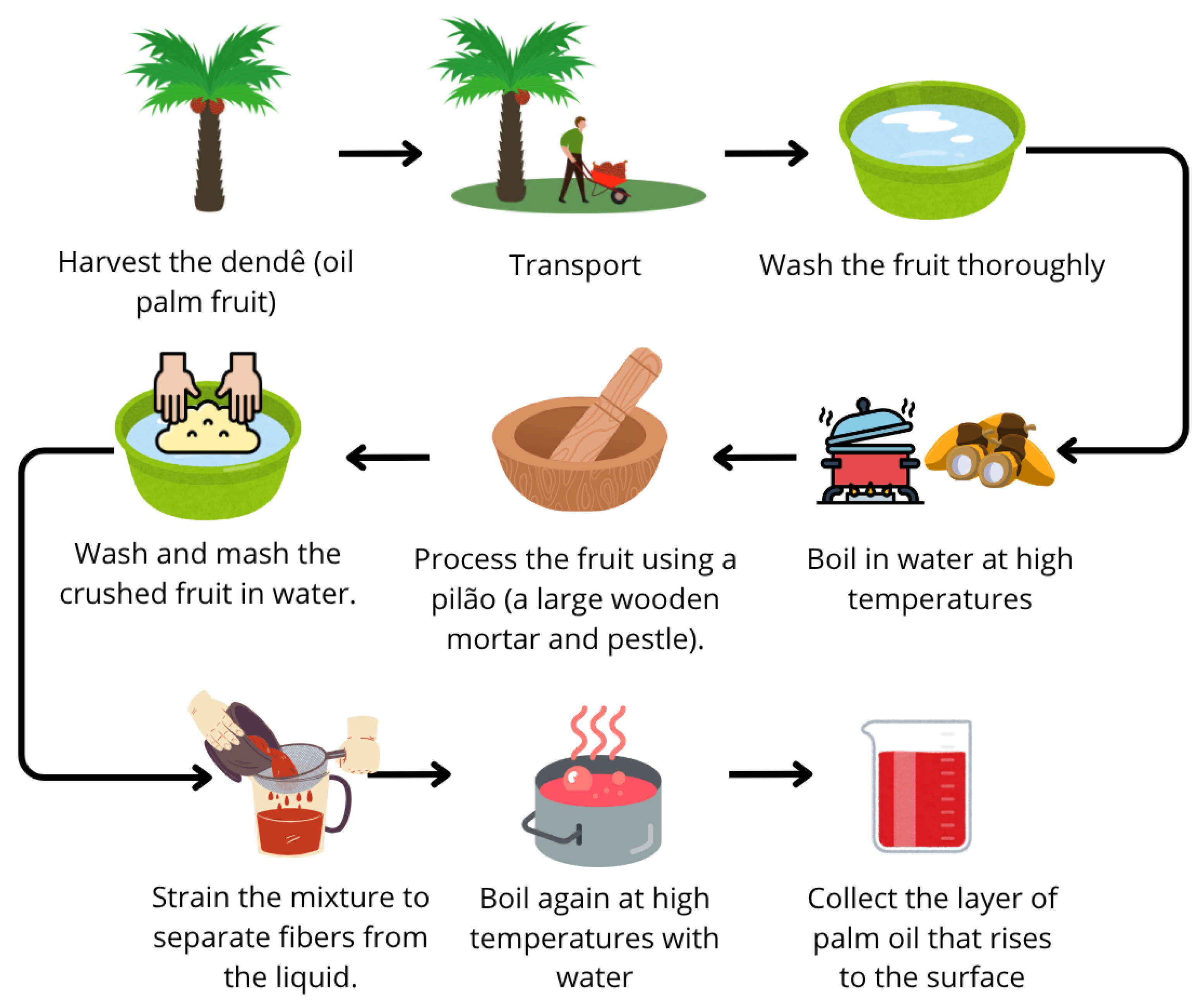

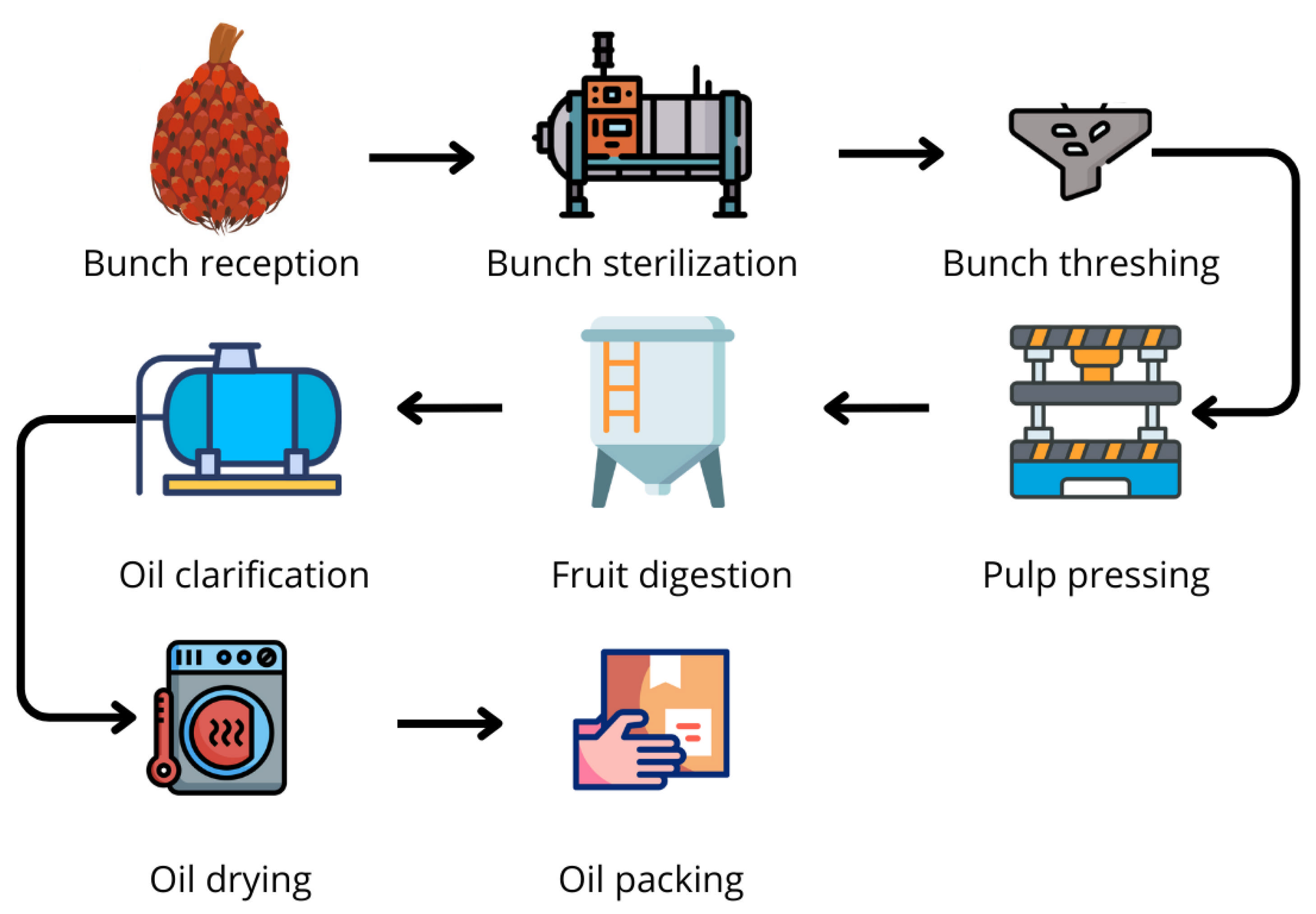

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 illustrate the different processing methods used in

dendê oil production.

Figure 9 depicts the

rodão method, a traditional technique involving mechanical extraction.

Figure 10 showcases the

pilão (mortar and pestle) method, which relies on manual processing. In contrast,

Figure 11 outlines the large-scale industrial production process.

By the mid-20th century, small palm oil mills had become important regional economic engines, employing diverse labor forces, including harvesters, collectors, and lavadoras de azeite, women responsible for hand-pressing oil from digested fruit fiber. This female-dominated labor system highlights the gendered dimension of Bahian dendê production, where women’s technical expertise and work practices formed a critical part of the intangible cultural heritage of palm oil. This network of small-scale producers played a crucial role in sustaining local economies and preserving traditional extraction methods.

Modernization efforts in Bahia’s palm oil sector began in the 1940s during World War II, when disruptions in global trade prompted increased interest in domestic production. French scientists introduced hybrid varieties like the high-yield

tenera, which were intended to replace traditional polycultures with monocultures and increase efficiency. However, these interventions had limited ecological and cultural penetration. By the late 20th century,

tenera hybrids had been adopted primarily in industrial plantations and experimental plots operated by companies like Opalma, covering only a small fraction of Bahia’s total palm oil-growing area. In contrast, much of the region’s palm oil landscape continued to be shaped by “subspontaneous” groves and traditional agroforestry systems, where oil palms grow alongside cacao, bananas, and native forest species. These diverse systems, maintained by smallholders, resisted full-scale conversion to monocultures due to cultural preferences, economic constraints, and ecological advantages such as soil fertility and pest control. Studies in southern Bahia suggest that even today, over 70% of oil palm stands remain integrated into multi-crop systems, illustrating the persistence of Afro-Brazilian agricultural knowledge despite industrial pressures [

3,

25].

By the 1950s and 60s, Bahia saw a surge in palm oil production, reflecting both small-scale and industrialized methods. Companies like Opalma began planting

tenera hybrids and applying chemical fertilizers and mechanized processors while also sourcing raw materials from local suppliers. This hybrid approach stimulated local production and created rural jobs. However, small-scale producers remained vital to Bahia’s palm oil economy, supplying both domestic markets and local religious communities [

25].

Today, the material traces of Bahia’s palm oil heritage are at risk of disappearing. Many rodões, once central to local economies and cultural identity, now lie abandoned and in advanced states of deterioration. These structures stand as silent monuments to Afro-Brazilian labor history and technical knowledge, embodying the overlooked industrial heritage of dendê production. Their decay reflects broader patterns of cultural erosion, as traditional knowledge and practices are increasingly displaced by modern industrial systems. The expansion of palm oil production has had complex effects on local communities. While industrialization created new job opportunities in large-scale plantations and processing facilities, smallholder farmers often struggled to compete with industrial producers. Many responded with resilience, forming cooperatives, sharing resources, and diversifying income sources to sustain their livelihoods. This persistence highlights the deep cultural significance of dendê in Bahia’s Afro-descendant communities, where traditional extraction methods and small-scale production continue to survive despite mounting economic and social pressures. The industrial heritage of palm oil in Bahia thus extends beyond physical mills and tools to encompass intangible skills, work practices, and social relationships that sustained these communities for generations. Recognizing and preserving this heritage is essential, not only for understanding the history of industrialization in Brazil but also for exploring alternative models of sustainable and community-centered production in the present.

5. Dendê as Resistance and Cultural Identity

The arrival of enslaved Africans in Brazil, spanning nearly 350 years, brought not only new people but also new religious and culinary traditions. Despite enduring unimaginable hardships, these individuals carried with them deep-rooted knowledge of food and agriculture, along with physical remnants of their homeland, including sorghums, yams, plantains, bananas, watermelon, okra, malagueta pepper, and oil palm trees. While these food traditions evolved through adaptation and improvisation in the Americas, they retained strong links to African cultural heritage [

43].

Afro-descendants played a crucial role in shaping the Americas, despite the oppressive structures of colonialism and enslaved African slavery. Their contributions, though made under severe restrictions, represent enduring acts of resistance to colonial rule. Scholars have described this resistance along a spectrum of “negotiation and conflict,” emphasizing how enslaved Africans people were not passive victims but rather active agents who used both direct and subtle forms of defiance. Food, agriculture, and daily practices became powerful means of resistance against colonial violence and governance [

25].

The emergence of Bahia’s palm oil economy is a direct result of Afro-Brazilian ingenuity and adaptation. Unlike the monocultures imposed by colonial authorities (such as sugar), the cultivation and use of dendê followed African traditions, forming a critical part of Afro-Brazilian identity and resistance. This everyday form of defiance was crucial in sustaining Bahia’s palm oil landscapes and economy. The processing of palm oil itself became a symbol of both cultural preservation and economic autonomy, allowing Afro-Brazilian communities to maintain a degree of self-sufficiency within an oppressive colonial system. This autonomy in production reinforced dendê’s role as a marker of cultural survival.

Maroon communities, known as mocambos and later quilombos, were established throughout Bahia by escaped enslaved Africans who sought freedom outside colonial control. These settlements frequently launched raids on plantations, inflicting economic damage on Portuguese landowners. Persistent insurrections led by Afro-descendants, Amerindians, and others marginalized groups forced many small farmers to abandon their fields, leading to the depopulation of rural areas. As a result, abandoned lands provided ideal conditions for African oil palms to spread and thrive.

During the colonial period, African religions were repressed by Portuguese authorities. Catholicism was mandated, and African rituals were often criminalized. However, enslaved Africans maintained their religious traditions through indirect means. Cuisine, especially that involving palm oil, became a powerful tool for safeguarding religious practices. Foods like acarajé, used in offerings to the orixás, were prepared in domestic settings and public spaces, making religious expression nearly invisible to colonial scrutiny while ensuring its survival. Remarkably, despite efforts to suppress African religious traditions, many of these dishes, rich in flavor and complexity, were eventually embraced by the broader colonial society, illustrating how Afro-Brazilian cuisine not only preserved sacred knowledge but also reshaped the dominant culture from within.

In Candomblé,

dendê holds complex religious meanings. It is considered an item of privileged use in offerings and initiatory rites. Palm fronds (màrìwò) are used to decorate the entrances of

terreiros (places of worship), and palm oil itself plays a vital role in rituals, particularly as an offering to the orisha Exu (Yoruba) or Legba (Fon). Historical records of early Candomblé

terreiros, such as the

Tuntum Olukotun on Itaparica Island and Salvador’s renowned

Alaketu and

Engenho Velho da Federação religious communities, reveal a deep connection between Afro-Brazilian religious traditions and palm oil cultivation [

25]. The act of cooking with palm oil, then, is not just culinary, it is cosmological.

Beyond its ritual significance, Candomblé embodies a complex system of religious syncretism, where African traditions merged with Catholic elements due to centuries of imposition and restriction of the colonial government. The formation of Candomblé in Brazil during the 19th century was a collective effort by African-born enslaved men and women, freedmen, and their Brazilian-born descendants. The Yoruba influence on Candomblé is particularly strong. The transformation of these beliefs into Candomblé reflects the resilience of Afro-Brazilian religiosity. Over time, the worship of orishas extended beyond direct descendants, integrating into broader Afro-Brazilian religious practices [

44].

Within Yoruba traditional religions, dendê carries multiple layers of symbolism. One of the most profound is its representation as “the lubricant of life”, the substance that allows existence to function smoothly, preventing friction, obstacles, and discord. Additionally, dendê is deeply tied to feminine mystic power (linked to Iyami Oxorongá, the Great Mothers) and to Exu, a foundational deity. The theological significance of these powerful spiritual forces being intrinsically linked to dendê underscores its religious importance, embodying movement, vitality, and transformation.

Dendê’s integration into Brazilian cuisine was significantly influenced by enslaved Africans cooks working in Portuguese households. These individuals introduced African techniques and ingredients, transforming Brazilian culinary traditions. According to Manuel Querino, African cooks played a pivotal role in shaping Bahian cuisine by introducing essential elements such as palm oil, dried shrimp, malagueta pepper, and coconut milk. He argued that the incorporation of

dendê revolutionized Bahian cuisine, elevating it to one of Brazil’s most distinguished culinary traditions [

24].

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 depict the São Joaquim Market in Salvador, where traditional ingredients are readily available. Most vendors are local producers, contributing to the preservation of regional food culture.

Dendê’s journey from a mere ingredient to a cultural symbol reflects broader shifts in how Afro-Brazilian traditions have been perceived. Despite their cultural prominence, Afro-Brazilian traditions remain vulnerable. Ongoing acts of religious intolerance, including attacks on terreiros and efforts to secularize or rename foods like acarajé, reflect persistent racism and cultural erasure. Once stigmatized due to racism and class-based discrimination, Bahian food, including its distinctive use of dendê, has been reclaimed as a fundamental part of Brazilian cultural heritage. Today, it is celebrated as a unique regional cuisine that embodies the intersection of European, Indigenous, and African culinary traditions. However, what sets Bahian cuisine apart is its unmistakable African influence, which has been preserved and adapted through generations.

While IPHAN has recognized the craft of the

baiana de acarajé as intangible cultural heritage, the broader system of

dendê-based foodways, including traditional processing methods, remains unprotected [

45]. Effective legal protection would require expanding heritage status to include recipes for ritual uses, and the raw materials involved in this cultural system. Without such measures, these expressions remain at risk.

Food is more than sustenance; it is a powerful expression of identity. Across cultures, communal eating reinforces social bonds and preserves local traditions, shaping group identities through shared culinary practices [

43]. In Bahia,

dendê-based dishes are not everyday meals but are reserved for special occasions, such as religious ceremonies and Catholic observances like Good Friday, when traditional foods seasoned with palm oil are commonly prepared. While many popular restaurants offer

dendê-infused dishes only on specific days, Afro-Brazilian households remain the true guardians of this culinary heritage. In Bahia, it is a long-standing tradition to serve Bahian food, particularly

dendê-based dishes, on Fridays and during special celebrations, underscoring the deep connection between food, culture, and daily life.

6. Sustainability and Cultural Knowledge: Lessons from Bahia’s Dendê Landscapes

As global demand for palm oil rises, driven by its widespread use in food, cosmetics, and biofuels, the environmental costs of industrial expansion have become increasingly visible. Industrialized palm oil plantations, particularly in Southeast Asia and increasingly in the Brazilian Amazon, have contributed to deforestation, biodiversity loss, and carbon emissions [

46,

47]. In contrast, Bahia’s

dendê landscapes have historically maintained a lower environmental footprint through small-scale, polycultural practices rooted in Afro-Brazilian traditions, preserving biodiversity and maintaining soil fertility [

48]. Unlike in Malaysia and Indonesia, where large-scale monocultures have devastated ecosystems [

49,

50], Bahia’s traditional approach to

dendê cultivation offers a model for balancing economic development with environmental stewardship.

Brought to Brazil through the transatlantic enslaved Africans trade, the cultivation of

dendê was not simply a transplanted crop but a transferred system of knowledge. Enslaved Africans, particularly from Yoruba, Fon, and Bantu communities, introduced palm oil processing methods and agricultural models adapted to tropical forest conditions. Afro-Brazilian farmers historically cultivated

Elaeis guineensis not as monoculture, but as part of a diversified and adaptive agroforestry system [

3]. These systems integrated oil palms with cassava, yam, banana, okra, and medicinal plants, fostering biodiversity and minimizing soil depletion. This polycultural approach not only preserved soil fertility and biodiversity but also increased food security and economic resilience by allowing families to harvest multiple products from the same plot of land [

51].

The traditional cultivation of

dendê followed a rotational system that allowed palm groves to regenerate naturally [

3]. Fruit was harvested manually, often by climbing the palms or using long-handled sickles, avoiding the need for heavy machinery and minimizing soil compaction.

dendê palms grew spontaneously within these polycultures, often without artificial inputs or clearing of native vegetation. Tools such as the

roçado,

rodão, and stone mills allowed for decentralized production, with women, especially

lavadoras de azeite, playing a crucial role in the oil’s extraction and refinement.

Each stage of traditional

dendê production reflects a sustainable and symbolic relationship with the environment. The cultivation was not just economic but embedded in a wider system of social organization, ancestral memory, and ecological ethics. This model contrasts with the large-scale monocultures now expanding in Brazil under public-private incentives, where hybrid varieties like

tenera dominate, and traditional producers face marginalization due to limited access to credit, land titles, and policy support. The story of

dendê in Bahia is ultimately one of cultural survival, adaptation, and sustainability, offering insights that could help address the global palm oil crisis while safeguarding cultural heritage and ecological integrity [

24,

44].

Even as modernization reshapes agriculture and food production in Brazil, dendê remains central to Bahian identity. While industrialized palm oil production has shifted to the Amazon, Bahia’s dendê culture persists through religious practices, culinary heritage, and the commitment of small-scale producers.

This interplay of tradition and innovation highlights broader themes of cultural resilience and adaptation. By preserving ancestral knowledge and embracing sustainable practices, Bahia’s Afro-descendant communities ensure that

dendê remains a living symbol of their heritage, enriching both local traditions and global discussions on sustainable palm oil production [

24,

44].

Local communities, particularly in regions like Bahia, have cultivated palm oil for centuries using traditional, sustainable methods that prioritize biodiversity, soil health, and economic resilience. By learning from these heritage practices, modern agricultural systems may discover more environmentally and economically sustainable approaches that benefit both global markets and local producers. Recognizing the value of traditional knowledge, indigenous expertise, and agroecological farming methods could offer a path forward, one that balances global demand with ethical and ecological responsibility.

Learning from Bahia’s dendê culture means embracing a broader definition of sustainability, one that includes cultural continuity, economic inclusion, and ecological regeneration. Traditional practices, far from being relics of the past, offer blueprints for addressing some of the most pressing agricultural challenges of the present. Recognizing and supporting these community-driven models could lead to a more just and resilient future for palm oil production, not only in Bahia but in tropical regions across the globe.

Traditional Systems as Blueprints for Palm Oil Sustainability

Recent research demonstrates that the principles of Afro-Brazilian agroecology can be successfully transferred to other biomes. The SAF

dendê project led by World Agroforestry (ICRAF), Embrapa, Natura, and CAMTA, demonstrates that oil palm can be cultivated profitably and sustainably when integrated into biodiverse farming systems. Contrary to corporate claims that intercropping reduces yields, field trials in Tomé-Açu reported higher productivity in agroforests, with 180 kg of fruit bunches per palm annually, compared to 139 kg in conventional monocultures [

52].

These systems incorporate up to 35 species, including açaí, cupuaçu, ipê, and nitrogen-fixing trees like gliricidia. Agroforestry not only diversifies farmer income and enhances food security, but also improves soil carbon stocks, supports native wildlife, and reduces reliance on herbicides and pesticides. Most importantly, they offer climate-resilient alternatives: lower pest pressure, richer microbial diversity, and improved water retention were all observed. According to Miccolis and Mongabay reporting [

52], agroforests demonstrated up to 238% greater microbial diversity than monocultures and produced higher soil carbon content, underscoring their potential for climate mitigation.

Supporting this perspective, reports from Natura and the SAF

dendê consortium highlight how integrating

dendê with species like andiroba, jatobá, cumaru, and passionfruit has delivered both ecological and economic benefits. The polyculture system can also be implemented using native and selected exotic hardwood species to generate natural fertilizers, contributing further to soil regeneration and nutrient cycling. Despite occupying only 180 hectares currently, these systems offer farmers income diversification, reduce pest and market dependency, and open the door for carbon credits due to enhanced soil fertility and land restoration [

53].

From a spatial planning perspective, the triangular planting scheme of nine by nine by nine meters, widely used in Nigeria, ensures optimal resource distribution and intercropping feasibility. With 140 to 150 palms per hectare, this layout supports agroforestry while maintaining sunlight, water, and nutrient access per tree [

54].

A model based on these parameters reveals that polyculture systems can match industrial yields. Considering palm morphology and yield assumptions of

tenera, each fruit measures approximately four centimeters in length and 2.5 cm in diameter. Each palm tree produces approximately four bunches per year, with about 500 fruits per bunch, resulting in an estimated fruit weight per palm per year of approximately 240 kg in a good year. With an oil content of 30% of the fresh fruit weight and a planting density of 145 palms per hectare, this translates into a total fruit mass of 3480 kg per hectare annually. Consequently, the oil yield reaches approximately 3480 kg or about 3910 L of oil per hectare per year [

39,

55].

The oil yield is calculated as:

where:

: trees per hectare

: bunches per tree annually

: fruits per bunch

: kg per fruit (accounting for shell thickness, volume, and density)

: oil content fraction

This yield rivals that of industrial monocultures, which range from 3500 to 5000 L per hectare per year, proving that agroecological systems are both productive and scalable.

According to Confins [

56],

dendê is the world’s most oil-efficient crop, yielding up to ten times more oil per hectare than soybean while occupying just five percent of global oil crop land. Additionally, oil palm supports one farmer per five to ten hectares year-round, highlighting its potential for rural employment and agrarian reform. Research also confirms that hybrid varieties can mimic native forest biogeochemical cycles, reduce erosion and water runoff, and rehabilitate degraded lands [

56].

Furthermore, companies like Natura have shown that transitioning to agroforestry-based palm oil systems can support biodiversity and improve farmer livelihoods. The regenerative practices employed since 2008 resulted in soil carbon levels significantly above those found in monocultures. By promoting polyculture with crops like andiroba, jatobá, and cumaru, the system ensures a more resilient and diversified agricultural model [

53].

Ultimately, these findings demonstrate that agroforestry systems based on Afro-Brazilian traditions are capable of meeting the productivity requirements of modern palm oil markets. The adoption of regenerative agroecological practices does not merely reflect a cultural legacy but offers concrete environmental, social, and economic advantages. These systems challenge the dominant narrative that monoculture is the only path to high yield, showing instead that sustainable methods rooted in tradition can guide the future of palm oil production.

7. The Baianas do Acarajé: Guardians of Tradition Across Generations

To answer the core research question “How can we safeguard these practices around palm oil from cultural erosion?” we must first go back and understand how the tradition has survived through the centuries in a way that is still so alive and relevant to a whole community.

The transmission of traditional dendê practices and associated agro-ecological knowledge across generations is achieved primarily through a matriarchal culinary lineage and the persistent maintenance of ritual foodways. As previously discussed, the maintenance of the foodways was a way of soft revolution that lasted over the years by the marginalized people.

However, there is a very clear symbol of this tradition being safeguarded. Through this matriarchal culinary lineage, the Baianas do Acarajé stand as the paramount custodians, serving as the cultural and economic vessels that embed this centuries-old knowledge, from cultivation to oil processing, into daily life and religious practice. Their role is not merely symbolic; it is the essential, continuous mechanism by which this critical heritage survives, often sustained by women marginalized within the larger social structure.

Historically, the palm oil industry in Bahia was heavily shaped by women’s labor. While the enslaved Africans trade was dominated by men, the processing, transportation, and trade of palm oil became a female-dominated industry [

57]. Women played crucial roles in harvesting, processing, and selling palm products, a tradition that continues today. The

baianas de acarajé, in particular, maintain a vital link between past and present, embodying the syncretic blending of African, Indigenous, and European influences that define Bahian culture.

The

Baianas do Acarajé play a crucial role in preserving Bahia’s culinary heritage. Throughout this article, their presence has been mentioned multiple times, but who are these cultural icons of Bahia? Oral histories suggest that in earlier times, only women initiated in the religion were permitted to sell

acarajé. The income generated from food sales helped support the

terreiros and sustain religious practices. This tradition, which began in the 16th century, has evolved over time, and today

acarajé vendors, known as

baianas, have become cultural icons throughout Bahia and beyond [

58].

According to Rita Santos, president of ABAM (Associação das Baianas de Acarajé, Mingau, Receptivo e Similares do Estado da Bahia), a true Baiana do Acarajé is a resilient woman, deeply connected to her ancestors and traditions. This testimony was given during an interview conducted by the NTNU research team on 6 January 2025, via Microsoft Teams platform. At the start of the conversation, she granted explicit consent for the recording and for the use of her words in this research, in line with ethical protocols.

“A Baiana de Acarajé is a strong woman, who has dendê running through her veins, who preserves the knowledge passed down by our ancestors. This craft has existed for over 300 years. She is a cultural and national heritage, officially recognized in Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, and Recife. These women safeguard ancestral knowledge, which has traditionally been passed down through generations. Today, things are changing—many want to be a Baiana de Acarajé, and entrepreneurs are trying to commercialize the dish. However, there are still Baianas who come from the fifth or sixth generation of Acarajé vendors—these are the true Baianas de Acarajé.”

Recognizable by their distinctive

tabuleiros (trays),

Baianas do Acarajé are an integral part of Salvador’s urban landscape. Over the past fifty years, their portable kitchens have become strategically placed throughout the city. Initially, vendors carried the trays on their heads, lowering them only when serving customers [

28].

Beyond their culinary expertise, many

Baianas are celebrated for their charisma and for embodying the traditions of Afro-Brazilian religious communities. A gastronomic map of Salvador has emerged through oral tradition, guiding locals and tourists to the best Baianas, based on taste, cleanliness, and hospitality [

29].

The image of the Bahian woman has become a national symbol, often depicted wearing 18th-century-style frilly white dresses, sitting on street corners frying

acarajé and preparing traditional sweets made from coconut and sugar. She represents roots, resilience, and purity, reflecting her African heritage, her ability to sustain others with minimal resources, and her immaculate appearance despite the challenges of deep-frying food in hot palm oil. Over time, Bahian dishes such as

acarajé,

moqueca,

bobó,

caruru, and

vatapá have gained popularity not only across Brazil but internationally. This culinary identity has traveled far, reinforcing Bahia’s distinct cultural identity [

59].

The use of dendê in these dishes is not incidental, it is the defining ingredient that connects the Baianas do Acarajé to a longer continuum of Afro-Brazilian cultural survival. Their mastery of dendê-based cooking, passed down over generations, embodies a deep agro-ecological knowledge rooted in West African traditions. While men historically dominated oil palm cultivation in colonial Brazil, it was women who processed, cooked, and ritualized dendê, making it central to both domestic economies and liturgical practices. Today, dendê remains the cornerstone of the tabuleiro, anchoring the Baianas’s role as culinary artisans and agents of cultural and religious preservation of African values. A Baianas do Acarajé must be perseverant, resilient, and committed to her craft. As Rita Santos explains:

“A Baiana must smile despite any hardships at home because her customers are not responsible for her troubles. She must honor and preserve the traditions passed down by our ancestors, who suffered greatly but left us this legacy.”

The

tabuleiro,

Figure 14 should feature a variety of traditional delicacies, including

vatapá,

caruru, shrimp, salad,

abará,

acarajé,

cocada,

bolinho de estudante, and

queijadas. In the past, it also included

pé-de-moleque,

bolo-de-folha,

moda, and

farinha-da-vovó, a mixture of flour and sugar toasted over fire.

Food not only unites communities but also distinguishes them. Ethnic cuisine reflects historically and geographically defined eating communities, yet, like ethnicity itself, culinary traditions evolve over time. Once established, they strengthen national and ethnic identities, with discussions and writings about food further solidifying these cultural narratives [

58].

In 2004, the ofício (craft) of the Baianas do Acarajé was officially recognized as part of Brazil’s cultural heritage by the National Institute of Historical and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN). The practice was defined as the traditional preparation and sale of Bahian foods, made with palm oil (dendê) and deeply connected to orixá worship, particularly in candomblé houses.

Today, the Baianas continue to organize through ABAM and, to a lesser extent, the National Federation of Afro-Brazilian Worship (Federação Nacional do Culto Afro-Brasileiro - Fenacab). While ABAM advocates for labor rights, food hygiene certification, and access to municipal space, Fenacab emphasizes religious legitimacy, traditionally accepting only filhas-de-santo into its ranks. Both organizations operate with limited government funding and continue to demand formal support mechanisms, including subsidies for traditional ingredients and simplified licensing procedures, that reflect their dual role as workers and culture bearers.

The organizations celebrates the

Baiana’s role as a cultural symbol, as seen in the commemoration of the “Day of the

Baiana de Acarajé” on 25 November, a recognition of their historical significance in Salvador [

44].

Originally referred to as “

preta do acarajé,” (Black woman of the

acarajé), these women not only sold food but also played a key role in sustaining candomblé communities. The sale of

acarajé helped

filhas-de-santo support their obligations to their

orixás, particularly Xangô and Iansã. Over time, different foods became associated with specific

orixás, for instance, those dedicated to Ogun sold beef offal, while those connected to Omolú specialized in

sarapatel and fish stew. Despite its low profitability, selling

acarajé was often preferred to domestic work, as it provided greater independence and evoked memories of self-sufficiency during and after African slavery [

44].

Acarajé,

Figure 15, was introduced not only in Bahia but also in Rio de Janeiro and Recife, brought by enslaved African women. In Rio, it was preserved for a long time at Quinta da Boa Vista, where these women were called

ganhadeiras or

quituteiras. In Recife, however, the practice did not flourish as it did in Bahia, where it was embraced and institutionalized, transforming the

ganhadeiras into

Baianas do Acarajé, likely as a tribute to Bahia’s dedication to preserving the tradition.

These women, dressed in traditional attire, as shown in

Figure 16 with their trays full of delicacies, became an emblem of Salvador. Like the city’s historic monuments, the

Baianas have come to symbolize Bahia’s cultural identity. However, little is known about their daily lives beyond their public image. It is widely observed that the tradition of selling acarajé has evolved from a primarily religious practice into an important source of income, particularly for lower-income women [

60].

Over time, the number of

Baianas has increased dramatically. In 1975–1976, Salvador had 166 officially registered

Baianas. By 2007, that number had surged to 2700, with an estimated 5000 including unregistered vendors [

61]. Today, ABAM reports 8000 registered

Baianas.

Despite being officially recognized by IPHAN as Brazilian intangible cultural heritage,

Baianas face challenges, particularly regarding their right to sell in public spaces. Historically, each

Baiana chose her selling location, often near public elevators, civic squares, and beaches. However, municipal regulations have repeatedly limited their presence [

29].

One major conflict occurred in 2013, when FIFA initially banned

Baianas from selling near the Arena Fonte Nova, a major football stadium in Salvador that hosted matches during the Confederations Cup. Citing commercial exclusivity rules, the organization attempted to displace traditional vendors. The decision sparked widespread protest in Brazil and abroad, leading to a negotiated return of the

Baianas for both the 2013 and 2014 World Cup events [

58].

Since gaining heritage recognition, the profession of the Baianas de Acarajé has undergone a dual process of institutionalization and commercialization. Tourism industries and city branding campaigns have increasingly adopted their image, often reducing complex religious and social histories to visual folklore. In response, many Baianas have enrolled in training programs supported by NGOs or municipal agencies, focusing on food safety, entrepreneurship, and cultural heritage law. Politically, their advocacy intensified, culminating in the 2012 recognition of their craft as an Immaterial Cultural Heritage of Bahia.

As Luiz Fernando de Almeida, then-president of IPHAN, noted in the official dossier:

“The official registration of the Ofício das Baianas de Acarajé as Cultural Heritage of Brazil, in the Book of Knowledge (Livro dos Saberes), is a public act of recognition of the importance of the legacy of African ancestors in the historical formation of Brazilian society, as well as the heritage value of a complex cultural universe, one that is also expressed through the knowledge of those who keep this tradition alive.”

The recognition emphasized that the tradition is not merely culinary, but a living expression of Afro-Brazilian symbolic universes. As detailed in the same dossier, the ambulant food trade practiced by the baianas traces back to the West African coast, where it represented a form of women’s economic autonomy that often positioned them as family providers. The dossier also makes a clear call for policies that not only honor the cultural value of the craft but provide concrete support for its preservation. It recommends cultural incentive laws, simplified access to public funding, and targeted legal and institutional support for ABAM’s organization and the enforcement of protective decrees. It also proposes dialogue with health surveillance agencies and integration with broader educational programs on gender, religion, and associated intangible heritage.

Despite these recommendations, key gaps remain. The recognition formally protects only the figure of the Baiana, the performance, attire, and ritual-culinary expertise, while excluding broader structural elements such as the production of high-quality dendê, the liturgical associations embedded in food preparation, and the right to public vending. In legal terms, baianas are still classified simply as “cooks,” erasing the specificity and depth of their cultural role. As it stands, the legal framework affirms the importance of the craft but fails to ensure conditions for its sustainable transmission and protection.

One rare exception is found in Municipal Decree No. 12.175, issued on 25 November 1998, which contains a clause reinforcing the intergenerational nature of this tradition:

“In the case of the license-holder’s death, a new authorization may be granted to the legally qualified heir, provided that public interest remains for such concession.”

This provision not only reflects the heritage-like transmission of knowledge within families but also reinforces the view of the Baiana de Acarajé as a cultural institution, one whose survival depends on policy, protection, and the continued agency of those who embody and transmit it. Despite these two major recognitions, the implementation and enforcement are inconsistent, and remains symbolically strong but materially weak.

According to Rita dos Santos, this recognition is not just symbolic, it is a fight for space, visibility, and rights, emphasizing the historical and social importance of Afro-Brazilian women who have long been marginalized [

61]. The urgency of this crisis is captured in the words of Rita Santos, president of ABAM—

Associação Nacional das Baianas de Acarajé, Mingau, Receptivos da Bahia:

“Twenty years ago, in Salvador, when you passed by places like Iguatemi (now Shopping da Bahia, central commercial center in the city) or Avenida Sete de Setembro (September 7th Street) in the late afternoon, the air was filled with the smell of dendê. Even if you were far from a baiana, you could recognize its presence by the aroma alone. Today, even standing next to a baiana, you rarely smell it anymore. That smell is disappearing.”

Santos highlights the diminishing presence of traditional, high-quality azeite de dendê. The rare dendê de pilão, manually processed and rich in aroma and flavor, has become unaffordable for most Baianas do Acarajé, costing between 40 and 60 reais (BRL) per liter. Meanwhile, the raw materials and production structures that sustain traditional palm oil production, such as roldons (processing units), are being abandoned due to lack of support and investment. Although Baianas do Acarajé have been recognized as cultural heritage by federal and state governments, Santos laments that this recognition remains largely symbolic, lacking concrete measures to support preservation efforts. With the decline in the quality of the main ingredient, the disappearance of traditional production methods threatens not only the craftsmanship behind it but also drives up the price of the original product, making it inaccessible to the local population. Coupled with the lack of governmental interest in protecting the people who sustain this tradition, Bahia’s intangible heritage faces the risk of fading away.

However, Baianas still face persistent socio-economic challenges. They continue to advocate for the formal recognition of their profession, not simply as “cooks,” but as Baianas de Acarajé, a designation that reflects their cultural, historical, and religious roles. Their work is deeply intertwined with public space, heritage, and identity. Far more than food vendors, they are custodians of a centuries-old Afro-Brazilian tradition rooted in resilience and reverence.

Their fight for recognition, space, and dignity continues, ensuring that the cultural and historical significance of acarajé and its makers remain an enduring part of Bahian and Brazilian identity.

This legacy is inseparably tied to dendê. From the women who once cultivated, harvested, and processed palm oil in colonial Bahia to the contemporary baianas who fry acarajé in the same red-gold oil, dendê serves as a living thread connecting generations. It carries not only flavor but memory, sacred meaning, and cultural identity. As such, dendê is not merely an ingredient, it is a symbol of continuity and a pillar of Afro-Brazilian heritage, especially for communities historically excluded from power. Recognizing and supporting the Baianas de Acarajé is thus a vital step toward preserving this displaced heritage and affirming the value of the cultural practices they continue to nourish.

8. Threats to Bahia’s Palm Oil Heritage

The tradition of palm oil (dendê) production in Bahia is facing multiple threats, including deforestation, industrialization, government neglect, and cultural shifts. Once a cornerstone of Bahian agriculture, economy, and identity, local dendê production has been increasingly replaced by large-scale monoculture plantations in the Amazon. This shift not only threatens traditional farming practices but also endangers the livelihoods of small-scale producers and the cultural heritage associated with palm oil.

8.1. Deforestation and Declining Production

Environmental degradation has severely impacted Bahia’s

dendê industry, reducing local production while increasing reliance on imports. In 2010, the Brazilian government launched the Program of Sustainable Palm Oil Production on Amazon (

Programa de Produção Sustentável do dendê na Amazônia), aiming to diversify the crop base for biodiesel [

62]. This program integrated national energy and development policies with international climate goals, promoting palm oil as a renewable energy source while attempting to regulate deforestation.

To prevent further environmental damage, the program established agro-ecological zones, allowing palm oil plantations only in areas deforested before 2008. Additionally, the initiative aimed to create employment opportunities for agricultural workers and expand market access for smallholders, thereby fostering development in impoverished rural areas.

By producing biodiesel from palm oil, Brazil sought to contribute to climate change mitigation through carbon sequestration and reduced

emissions. However, despite these goals, most government-backed palm oil cultivation has been concentrated in Pará, in the Amazon region, rather than in Bahia [

62].

The National Agricultural Research Institute (Embrapa) identified 5.5 million hectares of land suitable for palm oil in Pará. By 2013, the total plantation area had tripled from 50,000 hectares to 150,000 hectares [

62]. Meanwhile, in that same year, Bahia has seen a sharp decline in its

dendê plantations, producing only 1.5% of the palm oil it needs to meet local demand [

63].