1. Introduction

Merchant vessels comprised the backbone of the war effort during the two world wars, yet their sinkings are overshadowed by grander tales of naval conflict. These types of vessel were those impacted the most in World War II, particularly in the western Atlantic from a U-boat campaign which preferentially targeted tankers and other shipping [

1]. The wrecks of these liquid cargo carriers tell the stories of single-vessel incidents targeted by an unseen enemy lurking just below the surface; their importance, however, is twofold and lies at the nexus between both historical and environmental conservation. Oil tanker wrecks, to a greater extent than other shipwrecks, are significant to our ocean heritage, as they are “both historic sites of cultural significance and pose a threat to the marine environment, a juxtaposition that complicates protecting both cultural resource and marine ecosystems” [

2]. This article presents an overview of the historical development of oil tankers and their losses during the two world wars, followed by a series of case studies illustrating how tanker shipwrecks have been approached archeologically.

Visual documentation and characterization of shipwreck sites is often conducted for archeological purposes, and in some cases, is also performed for environmental purposes. For oil tanker shipwrecks, these investigations parallel one another as researchers document the same aspects of the wreck but with different objectives. This can include seeking information on the damage from the wrecking event, site formation processes, present day condition of the site, and dimensions and artifacts that can help confirm the identity of the vessel. The identity of the wreck matters for environmental concerns, in addition to its historical significance, as the type and amount of cargo carried is critical information for understanding the pollution risks and potential remediation requirements. Through such work, it is possible to address and remediate pollution threats while documenting historic wrecks and limiting impacts to the sites, many of which are war graves. In this way, potentially polluting wrecks (PPWs), as well as actively polluting wrecks, which are often oil tanker shipwrecks, exemplify the cross between cultural heritage and environmental concerns that comprise our shared ocean heritage [

2].

The interaction between shipwrecks and the environment has been a common topic of study in maritime archeology. Keith Muckelroy wrote that there is a “degree of correlation between the quality of the archeological remains and a number of possibly relevant environmental attributes” regarding site formation [

3]. Such lines of inquiry, however, are typically unidirectional, describing how the environment has affected the ship in its process of becoming the modern-day shipwreck. Less so has archeology addressed how the wreck has impacted the environment, aside from being used as hard substrate as a feature of the ecosystem. Toxic wrecks, in general, are rare. A few examples include SS

Richard Montgomery, sunk in shallow water off the Thames and full of unexploded munitions, and U-864, sunk off Norway in 1945 with a cargo of metallic mercury, which has been found to be leaking into the surrounding water [

4,

5]. However, the vast majority of vessels that sink into the marine environment do not damage the environment, and in fact provide nutrients as organic elements of the vessel’s decay, and hard substrate serving as artificial reefs. Muckelroy also wrote about a ship as a “machine” in that it was designed for movement, of people or goods, and as an “element in a military or economic system” [

3]. Tankers function in both systems, as they are always economic and, in many cases, have also had military contexts. Tankers reflect this purpose in their design, but in the case of petroleum products, their cargo not only defines them but also poses an environmental threat that requires remediation in the modern day.

Pollution from the transport of oil is not a new, 21st century problem; the Second World War, especially, already had a great impact on the marine environment. A study was performed in 1977 by researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology that reviewed U-boat campaigns during World War II to establish the possible resultant pollution events. This study reviewed sinking records off the eastern US and estimated that 484,200 metric tons (3.6 million barrels) of petroleum product were sunk by U-boats targeting oil tankers [

6]; some of this petroleum spilled into the ocean and some sank with the vessels. The study analyzed oil tanker vessel sinkings along the U.S. East Coast from 1942 and found that “the area around the thirty-fifth degree of north latitude was the site of the largest weight of spilled oil” [

6], which corresponds to offshore Cape Hatteras, NC, and was chosen for the focus of the study. This was an area where numerous oil tankers were sunk by U-boats during the initial Operation Drumbeat attacks, targeting the crossroads of maritime shipping along the Eastern Seaboard that became known as the Graveyard of the Atlantic or Torpedo Junction [

7,

8]. Tankers sunk here include many on a list of PPWs in US waters compiled by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in 2013, such as

Empire Gem,

William Rockefeller,

Lancing,

Paestum,

E.M. Clark and

Dixie Arrow (

Figure 1). While offshore Hatteras was identified as the major area of potential environmental impact, Jacksonville, FL, Norfolk, VA, and Asbury Park, NJ were additional areas of the East Coast that experienced significant numbers of tankers sunk in 1942.

The 2013 PPW study posed the question of whether a rapid succession of small oil spills would cause more environmental damage than several large spills over a few months, an important, but still unanswered question for present-day potentially polluting wrecks. In addition, the type of petroleum cargo and bunkers, ranging from crude oil to refined and processed products like gasoline, kerosene and lubricating oils, makes a large difference in terms of what the environmental consequences could be. The study found that “the potential for a major environmental calamity existed in the Cape Hatteras area during the first six months of 1942” [

6]. Weather modeling indicated that some oil would have washed ashore and more would have drifted out to sea. Witness interviews indicated that locals recalled small scale oil slicks washing up on beaches north of Cape Hatteras, but much larger amounts washed up to the south. “The general impression was that a sizeable quantity of oil came ashore, particularly on the island of Ocracoke” [

6]. Nevertheless, while the overall impact on the shoreline was considered minor, damage to the deep-water environment is entirely unknown and has only recently become a topic of study due to the Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Only in 2023 was a massive deep-water coral reef discovered off South Carolina on the Blake Plateau [

9] and there are likely numerous other such habitats yet to be discovered, where settling petroleum product in the past could have caused unwitnessed severe damage; it is also a major reason to address potential pollution from World War II wrecks sooner than later.

The question of pollution during the early 1940s from ships sunk during World War II was again addressed in 2019. Andriessen discussed the potential environmental damage from the 1940s in comparison to better-documented oil spills from the late twentieth century. Large oil spills, of which only two can be connected to tankers, included the grounding of

Torrey Canyon off England in 1967, the blowout of the offshore well Ixtoc off Mexico in 1979, the grounding of

Exxon Valdez in 1989, impacts of the First Gulf War in 1991 in the Persian Gulf, and most recently the offshore well Deepwater Horizon [

8]. Responses to some of these earlier spills, like

Torrey Canyon, included using detergents and chalk to disperse and sink the oil, leading to further impacts besides the oil itself. The impacts of oil are multiple, including physical, such as coating marine mammals and birds so they are unable to regulate their body temperatures or fly, and chemical, as oil compound toxicity vastly diminishes shellfish and invertebrate populations [

10]. Following the

Exxon Valdez spill, for example, the toxic impacts lasted for more than a decade. The toxicity itself comes from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), which disrupt “development, immunity, reproduction, growth and survival of aquatic organisms” [

10]. The spills can negatively affect all levels of biological communities and lead to higher risks of mortality, cancer, smothering, changes in abundance and recruitment, and disruptions in predator/prey interactions. The greatest factor is the “altered trophic relationships through the disproportionate loss of smaller organisms” [

11].

When it comes to tankers sunk by enemy action in wartime, most of these sinkings occurred further offshore, so slicks and localized impacts likely went unnoticed, masking the true impact [

8]. The worst-case scenario is a tanker wreck losing its structural integrity due to corrosion and catastrophically releasing its cargo into the environment all at once. As will be discussed later, this has been reported with the World War I wreck SS

Derbent, so the potential for World War II wrecks to do so in the near future is reason for concern. As these wrecks approach 80 years underwater, there could be multiple such events yearly.

What is the scale of the pollution threat from PPWs? An oil tanker cargo is an isolated amount, not like a blown well such as Deepwater Horizon. Let us take, for example, a T2-SE-A1 tanker from World War II like SS

Bloody Marsh. At full cargo capacity, these standard-built tankers could carry 141,200 barrels of oil, which is equal to nearly 6 million gallons (

Figure 2).

Exxon Valdez, one of the worst oil spills in U.S. history, released 10.8 million gallons of oil into Prince William Sound, which spread to cover 1300 miles of Alaskan coastline from a surface slick spanning more than 11,000 square miles [

12,

13]. If a T2 tanker were sunk with minimal release of its oil cargo during the sinking event, a worst-case catastrophic collapse discharge could inject more than half of the

Exxon Valdez spill into the marine environment at once from a single shipwreck. As there are hundreds of oil tanker wrecks from World War II, many of which have not been located, never examined or assessed for the hull’s condition, and many of these are likely to have more than half their oil remaining on board, the urgency of this problem becomes clearer.

2. Development of Oil Tankers

The advent of the age of petroleum in the late nineteenth century led to the development of specialized methods and vessels to transport petroleum products. The earliest “tankers” were sailing vessels modified to carry oil in cases and casks. The first recoded transport of oil by ship was

Elizabeth Watts, a 224-ton wooden brig hired by the Philadelphia firm of Peter Wright & Sons to haul barrels of oil to London [

14]. Early in the twentieth century, some of the sailing ships were modified to transport oil, with the last surviving example afloat being the four-masted steel ship

Falls of Clyde. Built in 1878, the ship was modified in 1907 to serve as a sailing oil tanker for the Associated Oil Company of California, with ten riveted steel bulk liquid tanks built into the hold, five to a side, and separated into two levels with larger tanks at the lower level and smaller “summer” tanks atop them. These were ventilated by expansion trunks that ran to the deck, and a small steam boiler was added behind an oil-proof bulkhead to power a 10-inch horizontal reciprocating oil cargo pump that connected to the tanks through a steel-pipe network. In addition to oil and crude,

Falls of Clyde also carried molasses in the tanks, and heated the tanks with separate pipelines when transporting molasses or crude oil [

15]. It operated under sail until 1922, when it was sold and turned into a floating oil barge.

The first steamship built specifically to transport petroleum products was

Zoroaster, which was launched in 1878 [

14]. The first modern bulk oil tanker was the German-built

Glückauf, launched in 1886, which wrecked off Long Island in 1893 [

16]. Its remains lie in several meters of water off Fire Island National Seashore, shrouded by sand, but it has never been archeologically studied. The first American-built bulk oil steamer, SS

Standard, was a product of the John Roach & Sons of Philadelphia and was launched in 1888. A general vessel type emerged, so that by 1943 it could be asserted that tankers had not undergone any “fundamental change except in equipment and details in construction,” while at the same time “the financial advantages of carrying oil in bulk had finally become fully recognized” [

14]. From a small fleet of steam tankers numbering twelve in 1886, the number climbed ten-fold within five years.

The first large output of steam-powered steel tankers to a single design were built in World War I as part of the Emergency Fleet Corporation’s (EFC) program. The EFC, formed by the USSB ten days after the U.S. entered World War I on 16 April 1917, was a corporate entity focused on building a merchant fleet. All ships being built in American yards at the time were requisitioned, and the EFC proceeded to issue contracts for a series of uniformly designed steamers following the steel steam schooner model [

17]. In all, some 1,400 contracts were issued to build ships for the EFC. Of these, thirteen Design 1041, steel-hulled tankers, six Design 1045 tankers, and twenty-eight 1047 Design tankers were built and entered service, with some lasting through the 1950s and out of the wartime and postwar fleet of EFC designs that totaled 316 tankers [

18].

After the war, a review of American ship types identified fifty-seven models, nearly all of them working vessels. Among these craft were intercoastal freighters that included tankers, then an emerging type of ship that in carrying “crude oil and refined oil comes in a class by itself” [

19]. These ships included veterans of World War I as well as other tankers that were part of the petroleum industry’s growing fleets as it responded to the shift from coal to oil for industrial purposes and as global markets emerged. By World War II, larger, faster ships were being built, with greater cargo capacity and a trend toward “larger and speedier tankers,” with “welding and lighter compact machinery”. These modern tankers showed an annual carrying capacity of about two and one-quarter times that of tankers built during the period immediately succeeding World War I” [

14]. The advent of welded hull joinery in place of rivets changed tanker construction substantially. “In this type of ship the advantages of welding in attaining and maintaining the degree of watertightness necessary for efficient isolation of various grades of cargo are so outstanding that the process is almost a

sine qua non for the building of tankers” [

20].

The World War II emergency shipbuilding program, and, in particular, the T-2, T-2-A, T2-SE-A1, T2-SE-A2, T2-SE-A3, T-3-S-A1 and T2-A-MC-K steel-hulled large capacity tankers, formed the global fleet of tankers after the war and well into the 1970s. These vessels gave way to the rise of the “super-tanker,” especially as 533 T-2s alone were built during the war [

21]. Postwar, larger capacity tankers began to emerge, as well as after the Suez Canal Crisis of 1967 when ship owners ordered larger tankers in a post-Suez era to avoid the risks of being held hostage to another closure. The role of market forces, a shift to fewer vessels with larger cargoes, and improvements in efficiency drove most changes until 1986. The

Exxon Valdez disaster, which followed other well-publicized tanker wrecks and large oil spills, resulted in the mandate that all tankers be constructed with double bottoms [

22].

3. Tankers in World War I: Convoys and the U-Boat Threat

The importance of petroleum in war became paramount during World War I as “oil drove the changes to naval power that contributed to the arms race that culminated in the outbreak of World War I” [

8]. Therefore, so too did the sinking of tankers carrying oil. By 1900, most machinery and motor vehicles were increasingly fueled by petroleum. Railroads needed oil as a lubricant, and asphalt, which is a residue of oil, became vital in road building. Even explosives such as TNT, grenades and torpedoes required chemicals produced from oil. And yet, only Russia and the United States had high enough domestic oil production to maintain a surplus and provide for other warring states [

23]. German railways for troop transport remained powered by coal, but as the war moved on, motor vehicles became essential on the front line, particularly as the western front began to freeze in late 1914. By 1918, “the mobility of Allied troops almost entirely depended on motor vehicles and therefore on North American Oil” [

23].

Moving oil to the European front was another challenge. The introduction of the U-boat to the naval battlefront nearly ended the war by cutting off supplies from the United States. From 1914 to 1916, the German submarines waged restricted warfare, where they would surface and allow for the crew to escape the ship before sinking it. As the war waged on, unrestricted warfare was initiated by Germany in early 1917 and allowed U-boats to attack merchant vessels without warning. This, in addition to an increase in the number of U-boats operating, led to an increase in ships sunk [

24]. The Allies, in response, turned to the system of convoys to protect merchant shipping of oil and supplies to Britain and the front. During this time, the only method for detecting a submarine was a hydrophone, leaving U-boats able to easily maneuver around vessels unnoticed. Convoys provided a system of defense for multiple merchant vessels and “the increase in the number of ships convoyed resulted in an increase in the number of U-boats destroyed” as the convoys included ships with means for “immediate counterattack” against the submarines [

24]. Within a single year later in the war, 24 U-boats were sunk by convoys. Some merchant vessels, however, continued to sail along coast routes independently without escorts or convoys, resulting in “avoidable losses or merchant ships” in coastal areas [

24], especially in and around Britain where U-boats patrolled heavily.

Nevertheless, the rise of petroleum shifted the parameters of warfare over the course of World War I. Most ships, particularly warships, were fueled by coal at the start of the war. A major impedance in coal-fired ships is fueling; oil is pumped into holding tanks relatively quickly and easily, whereas coal had to be shoveled on board by stokers. Oil also increased vessels’ range, doubling how far they could travel before refueling, enabled vessels to sustain higher speeds for longer, and allowed for refueling at sea [

25]. The engine room crew on a ship fueled by oil was also drastically reduced as it wouldn’t require the constant shoveling of stokers. The global transition from coal to oil in naval strategy began in 1898. Britain and the United States started converting ships in 1911 and Germany in 1915, but the rate of this transition was largely based on oil supply and so many ships during the war remained coal-powered [

26]. Aside from supplies in Russia and the Middle East, which Britain worked on securing, the United States had the largest and most secure supply of oil for the Allies. “Britain’s blockade led to food shortages in Germany, which responded by intensifying submarine warfare against Allied shipping lines [sic] in the Atlantic, including against US oil tankers destined for Britain and France. Thereafter oil-powered cruisers escorted tankers across the Atlantic” [

26].

4. Tankers in World War II: The Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic was the ocean-wide conflict of World War II that consisted of Germany’s all out raid on Allied shipping to cut Great Britain off from deliveries of fuel and supplies from the United States and other allies. The long-running campaign included an Allied blockade of Germany and their counter-blockade. The Kriegsmarine conducted raids on shipping with a variety of weaponry, including new surface warships such as the battleships

Bismarck and

Tirpitz; however, much of the conflict was primarily fought by U-boats targeting merchant ships. Between 1939 and the end of the war in 1945, 3500 merchant ships and 175 Allied warships were sunk compared to the 47 German surface warships and 783 U-boats lost in the same period. Britain had maintained its supremacy in naval warfare during World War I despite Germany’s introduction of the submarine, which nearly ended Britain’s centuries-long naval reign [

27]. While submarines had initially targeted the British Grand Fleet, they were deployed against merchant shipping later in the war, and this tactic, along with Allied anti-submarine warfare, was reinstituted on a broader scale in World War II.

Despite the lessons learned in the first war, Hitler had not planned on a naval battle and had not built up a fleet of U-boats prior to 1939. Initially hoping to avoid war on the water with Britain until the European mainland was subdued, the German naval fleet initially adhered to the limitations implemented upon it by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. Therefore, when Britain entered the war in 1940, Germany stepped up “production of submarines from 4 per month to between 20 and 25. Plans were approved by which 300 submarines would be in operation by 1942 and more than 900 by the end of 1943” [

27]. Although these numbers were never met, it explains why the U-boat war began slowly and reached its peak in 1942 and 1943. U-boats were deployed initially against merchant fleets in and around the British Isles and France through early 1940 and expanded to the eastern Atlantic from Iceland to Africa into 1941 with great successes. British destroyer escort numbers were low due to losses and damage during early engagements, thereby making “the summer of 1940… the U-boats’ greatest harvest season of the war. Although the total destruction that they wrought was far less than in 1942, the average tonnage sunk per submarine was almost ten times as great” [

27].

Still, the war on the water began slowly, with only a handful of ships sunk by U-boats in 1939. The Admirals of the Kriegsmarine, Erich Raeder and Karl Dönitz, became frustrated with the amount of contraband being moved through the North Sea in neutral ships and so they pushed to relax the rules of engagement for U-boats [

28]. As the war moved into 1940, British coastal convoys in the North Sea took a hit from the loss of 15 in the Norway and Dunkirk campaigns with another 27 damaged; this paved the way for the June 1940 “Happy Time” for U-boat commanders [

28]. Over the next year, U-boats began expanding their range farther out into the Atlantic, including a patrol line southwest of Iceland. Numerous ships on the Atlantic crossing were sunk in April 1941. The British were “stunned to learn of U-boats attacking so far west” [

28].

The war on the water expanded to the entire North Atlantic as the United States accelerated supplying Britain with fuel and goods. Fuel was especially critical to the Allied war effort, and therefore oil tankers were especially targeted by U-boats. During the American oil boom, the major producers were oil fields in Texas and Louisiana which shipped fuel to refineries on the east coast. Shipping via sea proved to be more economical than by railroad and so 95 percent of fuel oil came by ship [

28]. Therefore, the targeting of tankers carrying crude oil northbound along the east coast was a major disruptor in the fuel supply provided to the Allied front. The Roosevelt administration knew that the supply of oil, and its movement, would be critical, and thus named Harold I. Ickes the head of the Petroleum Administration for War, tasking him to expand interior petroleum infrastructure. However, by the time America entered the war in late 1941, about 260 tankers were engaged in moving crude oil from the Gulf to the Eastern Seaboard along sea lanes simultaneously used by British tankers moving product from the Caribbean [

28]. Nevertheless, before the end of the war, 61 tankers were sunk in American waters [

1], and globally, more than 860 tankers were sunk during World War II [

29].

January 1942 saw the initiation of Operation Drumbeat (Operation Paukenschlag) by German U-Boats against American shipping and the movement of merchant ships coastwise in American waters. This followed Hitler’s declaration of war against the United States on December 11 after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and an order to attack the U.S. on December 12. Type IX U-boats were used because the smaller types did not have the range to reach North America and operate. Kapitänleutnant Reinhard Hardegen of U-123 arrived off New England in mid-January and sank the freighter

Cyclops on January 12 off Nova Scotia, followed by two tankers off Long Island:

Norness on the 14th and

Coimbra the following night. The first wave of five submarines conducted attacks over nine days, sinking 27 ships, before returning to port in Germany in early February [

7,

28].

The devastation to merchant shipping in the first few months of 1942 was staggering. The Tanker Committee of the Petroleum industry War Council worried that the supply of oil would “sink to levels ‘intolerable’ both for the domestic economy and for any projected continuation of the war effort” if U-boat attacks remained unchecked, and if merchant seamen were reluctant to take positions, especially in engine rooms on tankers [

7]. The committee put forth a series of recommendations, including installing swinging guns on all tankers and suppressing shore lights showing seaward that helped silhouette ships for U-boats to spot. One of the first tankers armed with a four-inch 50 SP Mark IX Mod Gun was the new tanker SS

Gulfamerica. Soon after, it was sunk on its maiden voyage from Port Arthur by U-123 in early April off Jacksonville, Florida, the lights of which allowed the U-boat to spot the vessel.

What led to the end of the U-boat domination was the re-implementation of convoys from World War I.

“The convoy system that developed as a result of the U-boat threat changed the way goods were moved in order to minimize the chances of being sunk. Ocean going merchant ships, typically freighters and tankers, supplied and fueled the Allied war effort and were vital to the success of strategic campaigns that led to the war’s end. The Allied merchant vessel shipwrecks are significant due to their role as a link between war time goods being produced back home and troops fighting on the front line” [

1].

Early transatlantic convoys in “1939–1941 consisted of 45 to 60 merchant ships in nine to twelve columns” [

27]. Battleships and heavy cruisers were abandoned as protection for convoys early on, as they were of little use against submarines, and the German capital ships rarely appeared to attack convoys. Instead, destroyer escorts, armed with sound gear and depth charges, become the primary defense for the merchant ship columns. Zigzagging was “advised for fast convoys, or for small ones with a narrow front; but large or slow convoys must follow a straight course, because zigzagging diminished the distance made good, caused confusion and straggling, and had proven ineffective in avoiding submarines” [

27]. Merchant ships traveling unescorted did benefit from steaming in a zigzag pattern, while those that did not were easily picked off by U-boats.

The end of the first six months of 1942 left almost 400 vessels on the bottom of the ocean along the East Coast, Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. It had nearly spelled disaster for the Allies, particularly because much of the cargo lost consisted of petroleum products that could not easily or quickly be replenished [

7]. While Admiral Doenitz boasted that the submarines were operating close to American shores, by mid-summer 1942, “The sinkings had ceased. Convoys had been instituted” [

24]. Convoys not only protected merchant ships by discouraging U-boat attacks, but they also allowed for fast and efficient hunting of submarines. The convoys were equipped with enough ships to take the offensive against submarines that exposed themselves during an attack. While the U-boat was designed to be elusive, it was ineffective when it came to periscope depth and fire, drawing depth-charge laden destroyers upon it quickly. Following this turn of the tide, while individual ships continued to be lost to submarines, the numbers were far fewer, and supplies began reaching the Allied front again.

The ships sunk as part of the Battle of the Atlantic and Operation Drumbeat are listed in the National Register of Historic Places in the multiple property nomination, “World War II Shipwrecks Along the East Coast and Gulf of Mexico,” completed in 2013. “The vessels engaged in the Battle of the Atlantic, including those sunk as victims of the U-boats represented a variety of ages and types as well as nationalities, but many of them fit into the increasingly specialized types of craft and vessels that resulted from scientific principles of naval architecture and industrialized shipbuilding practices which had emerged in the late 19th century and which took root in the early 20th century” [

1].

5. Potentially Polluting Wrecks

The U.S. Coast Guard, which would coordinate and often contract for the remediation of polluting wrecks, is required under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) to consider adverse effects to these historic properties [

30]. In an emergency response situation, there is often insufficient time to adequately comply with the NHPA to determine if a wreck warranted mitigation because it was listed in, or was eligible, for the National Register of Historic Places. What was needed was a proactive approach that streamlined the process.

The 2013 study by NOAA on potentially polluting wrecks consisted of a systematic approach to identify and assess the threat of oil pollution stemming from shipwrecks in US waters. This began with a comprehensive database of shipwrecks in US waters using historical records and maritime archives, called the Remediation of Underwater Legacy Environmental Threats (RULET) database. The wrecks included in the database were then evaluated based on their potential to leak oil or other hazardous materials. Factors taken into consideration included the type of cargo, amount of bunker fuel on board, structural integrity of the wreck, and proximity to environmentally sensitive areas. The list was narrowed down to 87 highest priority wrecks based on their risk of causing pollution events [

31].

Table 1 lists the World War II oil tanker wrecks on the PPW list including their status. Note that many have never been located.

With these 87 historic wrecks identified as the highest pollution risk, NOAA proposed a best practices approach through a multiple property submission that encompassed the entirety of the geographic and temporal span of the Battle of the Atlantic [

30]. This was proposed to “proactively test and refine the potential NRHP eligibility well in advance of any oil spill incident” [

30]. Following meetings with the Keeper of the National Register, who agreed with this approach for the largest nomination ever proposed and undertaken in the history of the National Register, the project proceeded.

The desktop PPW study was limited in what it could determine because many of the wrecks deemed potential polluters had yet to be found, and as

Table 1 shows, remain unfound to this day. However, the study put forth a large amount of good historical and environmental information that assisted in informing later remediations, such as

Coimbra in 2019 and

Munger T. Ball in 2021 [

32]. The limitations of the research required that some assumptions be made about wrecks, some of which hold true, and some that have been challenged by recent work on other sites.

A Coast Guard investigation report from 1967, following the grounding of the tanker

Torrey Canyon, indicated that ships that settle upright on the seabed will lose oil cargo and fuel oil through vents and piping over time. The report suggested that oil would escape through the vessels’ ventilation systems gradually and over an extended period, so much of that which escaped would be assimilated and biodegraded in the environment. The study concluded that “there is indication that a cargo will probably be lost from tanks thru [sic] ventilation or other fittings before plating and other structure corrodes away” [

33], and that “this project indicates that tankers sunk during World War II do not present a potential pollution threat to the American coastline” [

33]. Using this information, the PPW study further indicated that “ongoing research strongly suggests that deepwater shipwrecks tend to settle upright on the bottom” [

34].

This assumption was put to the test with the wreck of SS

Montebello off Monterey Bay, California. The tanker was carrying a cargo of 75,346 barrels of crude oil plus 8400 barrels of bunkers when it was struck near the bow by a torpedo from Japanese submarine I-21. The wreck was explored in 1996 at a depth of 268 m and was found to be sitting upright on the seabed with the bow section about 100 feet from the wreck. Initial assessments of the wreck suggested that, because the cargo was an asphalt-based crude that was nearly solid at cold temperatures on the seafloor, the fuel would have congealed and not moved, and that removal of the fuel would require heating [

35]. However, a later neutron backscatter assessment of the hull found little oil remaining on the wreck, indicating that, despite no breached tanks from the torpedo attack and the highly viscous nature of the fuel, the oil must have slowly escaped through vents and piping [

31].

Another assumption in the study was that shipwrecks broken into multiple pieces would have a lower risk of polluting due to the release of oil from the breached tanks and other damage sustained during the sinking event. “Structural Breakup… this risk factor takes into account how many pieces the vessel broke into during the sinking event or since sinking… even vessels broken in three large sections can still have significant pollutants on board if the sections still have some structural integrity” [

31]. The risk factors were categorized as Medium if the vessel was in two to three pieces and low if in more than three. While oil is inevitably lost during torpedo-attack sinking events, as Campbell and Andriessen have previously written, it is not a strong reason to write off a wreck as low pollution risk. A set of case studies presented below will challenge these assumptions.

The subject of potentially polluting wrecks has received recent and renewed interest through an international effort, Project Tangaroa, funded and organized by the Lloyd’s Register Foundation and The Ocean Foundation. This project has held three workshops with archeologists, maritime historians, government representatives, and salvage industry experts to develop a framework for the standards and strategic approaches used to take proactive action against possible pollution threats, emphasizing proactive rather than reactive responses. This effort also produced an academic volume published by Springer, Threats to Our Ocean Heritage: Potentially Polluting Wrecks, that outlines a series of case studies and methodologies for addressing PPWs (Brennan 2024) [

2]. The book concludes with remarks that highlight that the “resources, technical and financial, will only become available at the level required once there is a clear and widely accepted roadmap to better governance and optimised interventions”, a directive that the project is moving toward [

36].

Efforts to establish global standards for the management of ocean heritage, including protections for both underwater cultural heritage and the surrounding marine environment, are critical to mitigating pollution risks. One example is the North Sea Wrecks project, a multinational initiative addressing the extensive number of shipwrecks and dumped munitions dating to the First and Second World Wars. The project characterizes these sites as “marine slow disasters,” as chemicals and pollutants continue to leak into the marine environment due to ongoing corrosion of their hulls [

37]. These efforts align with broader United Nations initiatives under the Decade of Ocean Science, and more specifically with the Ocean Decade Heritage Network, which seeks to integrate maritime archeology and heritage into ocean science frameworks [

38]. Although oil tanker wrecks constitute only a subset of the environmental threats posed by the material remnants of war, they represent a disproportionate share of potential pollution risk. At the same time, they form a distinctive category of shipwreck that reflects both the petroleum-fueled logistics of modern warfare and the experiences of the merchant mariners who operated them, positioning these vessels within a unique niche of ocean heritage.

6. The Archeology of Oil Tanker Shipwrecks

The question of archeology and archeological significance of oil tanker shipwrecks has been partly addressed in practice but not in theory [

1]. The archeology of oil tanker shipwrecks “is unusual in the discipline of maritime archeology because the construction of the vessels and the manner in which they sank is generally known” [

32]. I have previously written on the archeology of discard as it relates to the sinking of old warships following World War II, particularly in terms of Operation Crossroads and the irradiated ships from the nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll [

39]. This attitude toward sinking old material into the deep sea has changed in recent times, and it is reflected in the out of sight, out of mind mentality that removed liquid cargoes from Allied access by the Kriegsmarine. Due to this outlook of generations past, we are now stuck today with the environmental consequences resulting from this laissez-faire method of warfare; shipwrecks are not lost forever once they sink beneath the waves, and the hazardous materials they carried persist in the modern marine environment. “Oil tanker wrecks fit into the maritime cultural landscape of war, and a landscape of environmental hazards we now face due to the attitude toward maritime assets at the time” [

32]. The status of these wrecks as war losses and war graves instill a military lens onto merchant vessel wrecks, adding further complexity and significance to these wreck sites around the world.

Archeological projects involving tanker wrecks have focused on identification of wrecks as part of larger surveys; an early example is the 1930 wreck of the Richfield Oil Company tanker

Richfield in the waters of Point Reyes National Seashore and Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, which was relocated and briefly examined in a Phase I Reconnaissance Survey in 1982. The preliminary history of the vessel, built originally as SS

Brilliant in 1913, noted its transitional nature as a “modern” tanker with longitudinal framing and bracing, which was introduced after other tankers without that feature had suffered structural failure [

40,

41]; The site was described as “tons of broken, jagged metal wedged in the rocks of the reef” [

40]. The same approach has been applied by other U.S. agencies with mandates for comprehensive cultural resource surveys. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) has performed this in American coastal waters, notably in the Gulf of Mexico but also along the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts [

42].

NOAA’s Maritime Heritage Program has assessed a number of World War II losses, including the tanker

Montebello, which was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine off California’s southern coast. Most notably, the program has also studied several U-boats and their victims, including tankers, off the coast of North Carolina as part of a larger Battle of the Atlantic submerged battlefield study [

43]. Archeologists from USS

Monitor National Marine Sanctuary and partners have also studied the wreck of the WWI tanker, SS

Merak, lost to a submarine attack in 1918, and the tanker

Kyzikes. Originally a 1900-built bulk freighter and converted into a tanker in 1901 for Sun Oil,

Kyzikes was sold in 1927 to Greek owners, renamed, and wrecked in December 1927 on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, with its first initial study taking place in 1996 by East Carolina University. World War II tanker wrecks documented by the NOAA team off North Carolina include the tankers

Ario,

Askkhabad,

Atlas,

Australia,

British Splendour,

Byron D. Benson,

Dixie Arrow,

E.M. Clark,

Empire Gem,

Esso Nashville,

F.W. Abrams,

Naeco,

Panam,

Papoose,

San Delfino,

Tamailipas, and

W.E. Hutton (

Figure 3). Many of these are shallow wrecks frequented by recreational divers and site assessments have determined that they are not a pollution risk.

Empire Gem and

Panam, however, are among those on the PPW list and are thus considered a threat [

31].

Internationally, PPW examples include the wreck of SS

Conch, a British-built 1892 tanker and lost in 1903. The wreck had been assessed by the Sri Lanka Maritime Archeology Unit but was noted “as one of the world’s first oil tankers,” and, “while it is believed to have no archeologically significant artifacts now–having been stripped of all portable items… a systematic study can yet yield archeologically significant information about the ship as a whole” [

44]. The WWI tanker

Darkdale, sunk in 1941 at St. Helena, was where a detailed archeological assessment in advance of oil remediation discovered “much… about her role and the impact of this loss on the wider war effort,” as well as aspects of the vessel’s construction, trading pattern “and even the chemical composition of the fuel she was carrying,” and though this, “the gaps in the historical record became very apparent…and whilst it is assumed that these gaps exist for earlier wrecks, the extent of the missing information for a relatively recent wreck was surprising” [

45]. Numerous tankers were sunk over the course of World War II, including many in the Pacific that were lost in deep water after attacks by Japanese submarines and have yet to be located. Others include the three tankers sunk in Chuuk Lagoon in 1944:

Fujisan Maru,

Hoyo Maru and

Shinkoku Maru. These wrecks have been extensively dived and documented, and “have the potential to carry up to 32,000 tons of oil” [

46]; however, in addition to these, there are many other wrecks of pollution concern at Chuuk. USNS

Mission San Miguel, a T2 tanker which ran aground on Maro Reef in the northwestern Hawaiian Islands in 1957 and was relocated in 2015, was listed as a PPW in the 2012 study. Archeological investigation of the site found that the hull was badly broken up and no longer contained any oil [

47].

What has begun to emerge is a growing recognition that these sites hold multiple, overlapping values. They represent not only the risk of potentially polluting the marine environment—and, in some cases, actively doing so—but also derive significance from their status as gravesites, memorials, fish-friendly artificial reefs, dive tourism destinations, historic landmarks, and archeological resources. The cultural aspects of significance, as reflected by the criteria for listing in the National Register of Historic Places, are recognized, and through that mechanism are legally required to be considered by federal agencies. These aspects have been applied through the previously mentioned multiple property submissions. Spanning the Eastern Seaboard of the U.S. to the Gulf of Mexico and limited to waters within the United States Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), including State waters, 187 shipwrecks could potentially be included. 163 of them could be merchant vessels, lost between 13 January 1942 and 6 May 1945. To date, eighteen wrecks have been listed in the National Register, and as part of that listing, each vessel has required separate documentation and an argument for its context, significance, and how it meets the criteria for listing [

1].

Therefore, the context for remediation, especially where federal funding or actions are involved, triggers the necessity for consultation with, and adherence to, the National Historic Preservation Act. The historic and archeological aspects inherent in listing also reflect research-design-based investigations into not only individual vessels but the broader maritime cultural landscape. In most cases, these wrecks are studied through battlefield archeology, especially given that the Battle of the Atlantic was the largest and longest-running battle of World War II. However, research-design driven archeology is not the primary focus of mitigation, in line with historic preservation law and policy, when a mitigation is required for a potentially polluting wreck.

Locating and identifying oil tanker wrecks is essential to properly assessing and potentially mitigating any environmental hazard. Incorrect identification could lead to inappropriate remediation methods if, for example, different petroleum products were carried on board in cargo tanks at different spacing. Archival and historical research can inform archeological documentation and characterization of a site and lead to a positive identification. Research can also lead to the correction of previously assigned identity, as was performed on the

Munger T. Ball shipwreck off Key West, Florida, originally believed to be that of

Joseph M. Cudahy [

32]. Extensive multibeam mapping and GIS database analysis has also led to the correction of tanker wreck identities in the Irish Sea, including

British Viscount,

Rotula, RFA

Osage, and RFA

Vitol [

48].

9. Conclusions

While the main driver for locating and assessing oil tanker shipwrecks is to determine pollution potential, their archeological significance extends beyond possible oil spills. These wrecks are the remnants of merchant vessels and grave sites that may not contain military personnel, but were intrinsically linked to the war effort, and are wartime losses due to naval action. This niche of maritime archeology therefore lies solidly within the concept of ocean heritage at the nexus of protecting historic resources and the marine environment. For the merchant vessels sunk during the Battle of the Atlantic, “the shipwreck remains are part of the larger maritime battlefields and cultural landscapes of America’s participation in World War II which includes waters close to home” [

1]. World War II spanned nearly the entire globe, and merchant vessels carried supplies, particularly oil, to any location that ships were deployed to. This global maritime landscape is now reflected on the seabed; however, the buoyant liquid cargoes retained in their hulls will not remain in place permanently.

While NOAAs PPW study from 2013 was a much needed first step, along with other such desktop studies, it must be noted that making risk assessments of wreck sites that have yet to be located or documented is not only problematic but impossible. The case studies presented above show the essential information required to assess each wreck’s pollution potential. Obtaining such critical information requires archeological characterization and assessment of each wreck site to avoid assumptions based on broad generalizations that may not apply to individual cases. This highlights the type of data that standardized documentation at PPW sites can help address. For example, the wreck of

Bloody Marsh illustrated that sinking in deep water does not guarantee that a vessel will settle upright; instead, the vessel is overturned, trapping its petroleum cargo against the hull, which was found to be remarkably intact [

50]. This result was contrary to the assumptions made in the PPW assessment of

Bloody Marsh, which were based on historic documents rather than the, at the time, undiscovered wreck [

34]

Recent efforts have advanced the discussion around polluting shipwrecks, with new international coalitions working to develop standards and tackle the primary challenge in managing PPWs: funding. Project Tangaroa is contributing to these efforts by establishing a framework to enable funding for the cleanup of PPWs. There is urgency to the matter, however. The case of the World War I tanker SS Derbent shows that these hulls can collapse catastrophically after a century corroding in the marine environment. Thankfully in that case, the oil had leaked out long ago and there was not a major release of oil. However, there are far more World War II tankers on the seabed and span a much larger area of the globe. If tanker wrecks along the Florida and Carolina coasts, for example, start catastrophically failing like the wreck of Derbent did, and do so in close succession, the southeastern coast could face repeated oiling for decades, causing persistent environmental damage to marshes, coastlines, and the tourism industry, and result in costly cleanup. The density of wrecks off the US east coast, as well as in areas of the South Pacific and North Sea, is such that pollution from shipwrecks could become a significant and long-lasting environmental and economic burden.

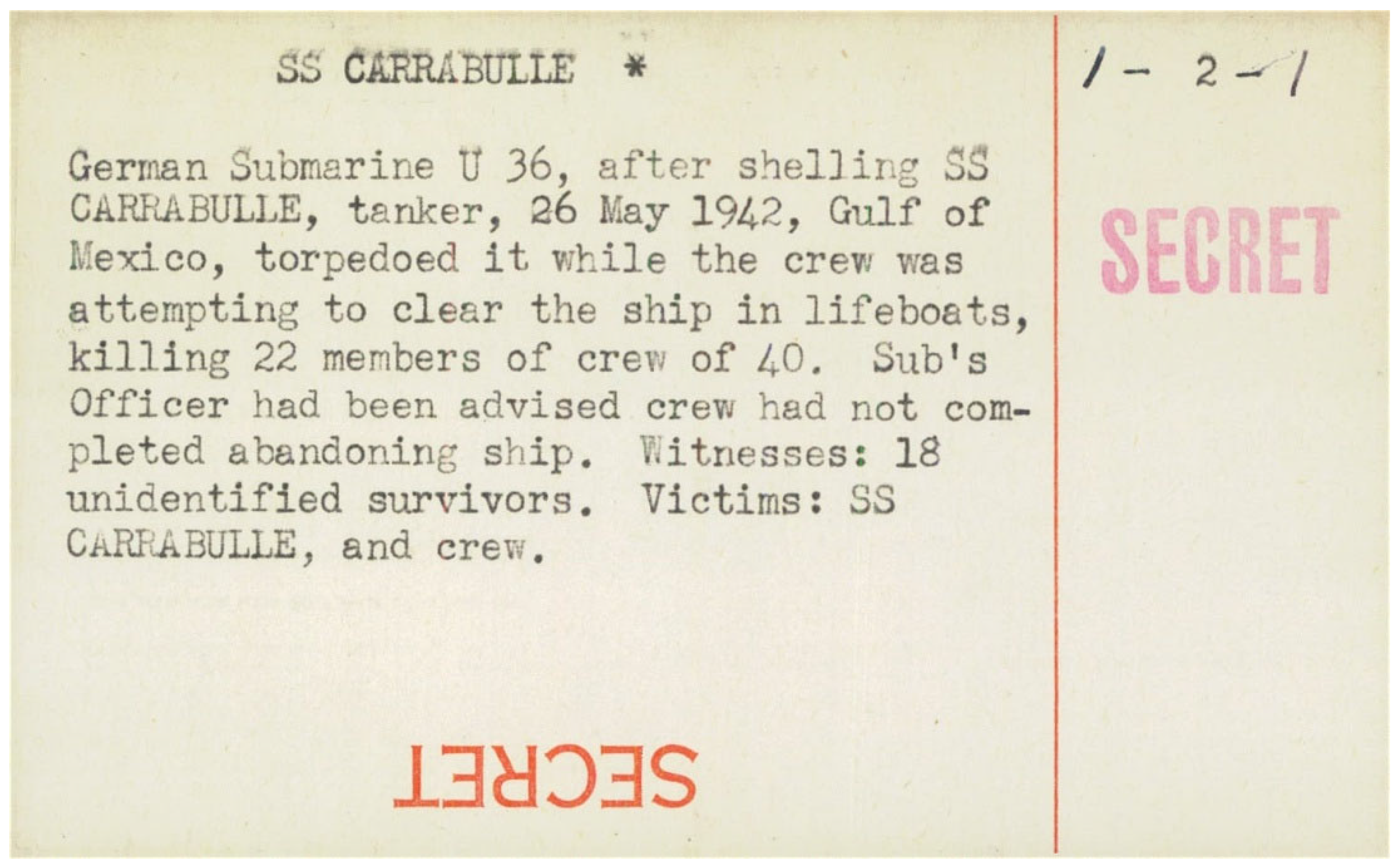

There are additional reasons beyond pollution to find and document these wrecks. Many represent historically significant wartime losses and serve as grave sites for merchant marine sailors. While there may not be an urgent need to find and assess wrecks like

Carrabulle, its unusual cargo and location, tied with its notorious sinking event, makes it a historically significant site. The same can be said for the recently identified wreck of SS

Rawleigh Warner off South Pass, Louisiana, which suffered a complete loss of life after being attacked by a U-boat [

65]. The maritime history of these merchant ships alone justifies efforts to locate these wrecks and tell their stories. The pollution risk they may or may not pose adds urgency to the situation, cultural significance aside.

Setting funding needs aside, a similar challenge is expanding ocean exploration to locate sunken tankers and merchant vessels that still pose pollution risks. Comprehensive review of ocean surface satellite imagery data, broad deep-water autonomous underwater vessel (AUV) survey, and ROV investigations to visually document and assess these wrecks are paramount. This work must be completed before any remediation or pollution mitigation efforts can be considered. Visual inspection has confirmed that many wrecks no longer pose a pollution risk, as they have been found broken up, resting upright on the seabed, or badly corroded. But this initial baseline inspection is essential. Without locating these wrecks in deeper water and obtaining critical data on them, mystery spills with no indications of origin, oil type, or potential extent of spill could become a more regular destructive problem.