Exploring the Delineation Methods for Buffer Zones of Historical and Cultural Villages from a Perspective of Cultural Geography: A Case Study of Huitong Village in Zhuhai, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Delineation of Cultural Heritage Buffer Zones Urgently Requires Mature Theories and Methods

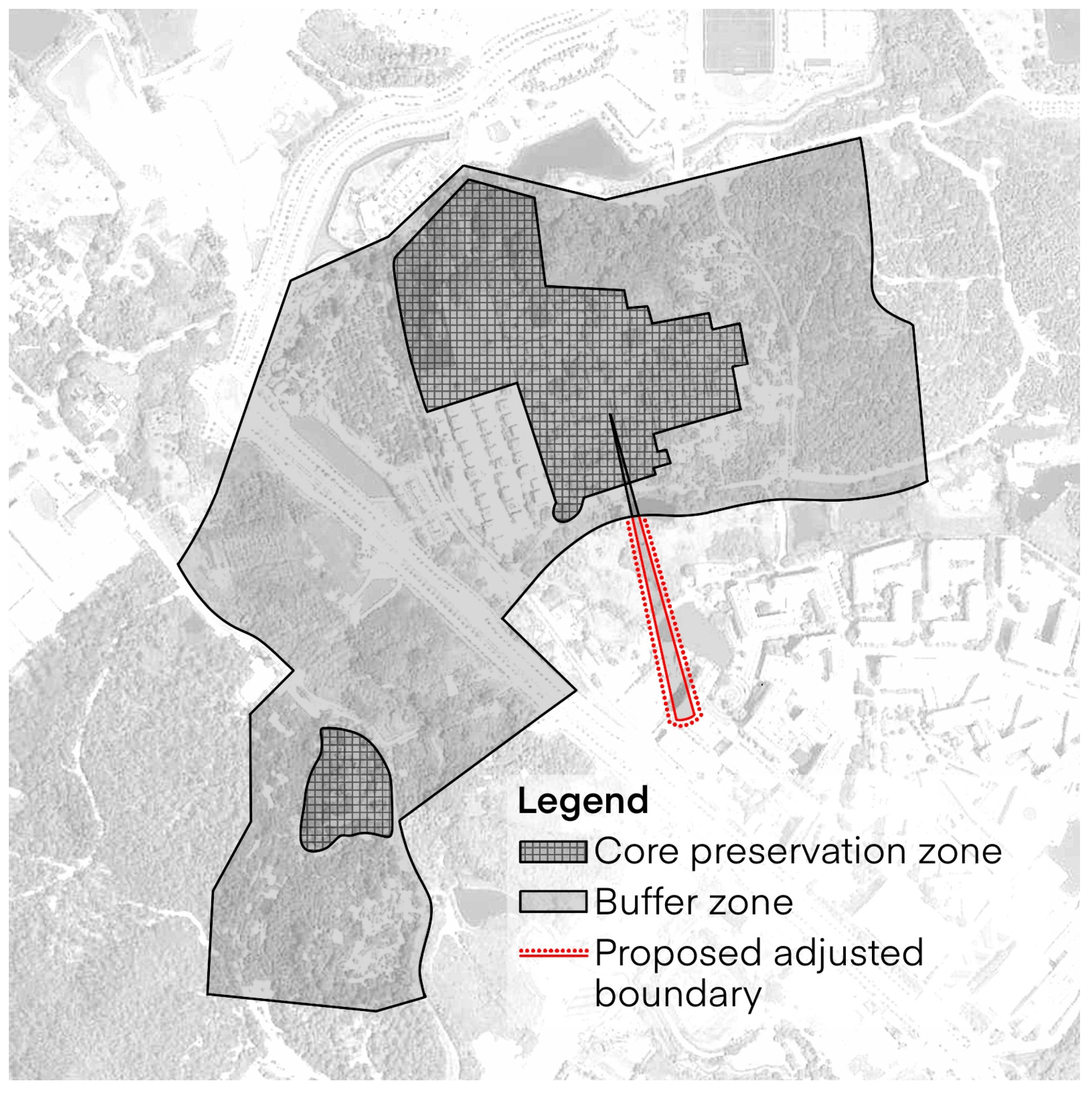

1.2. The Perspective of Cultural Geography in the Buffer Zones’ Delineation Methods Has Its Advantages

2. Research on the Delineation of Buffer Zone for Historical and Cultural Heritage

2.1. “Inward”—The Research on Buffer Zone Supporting the Protection of Core Area

2.2. “Outward”—The Research on the Buffer Zones Promoting the Transition Between the Core Areas and Other Areas

3. Research Area and Research Methods

3.1. Information About Huitong Village in This Study

3.2. Research Methods

4. Analysis

4.1. Determine the Spatial Base Points for Delineating the Buffer Zone of Huitong Village

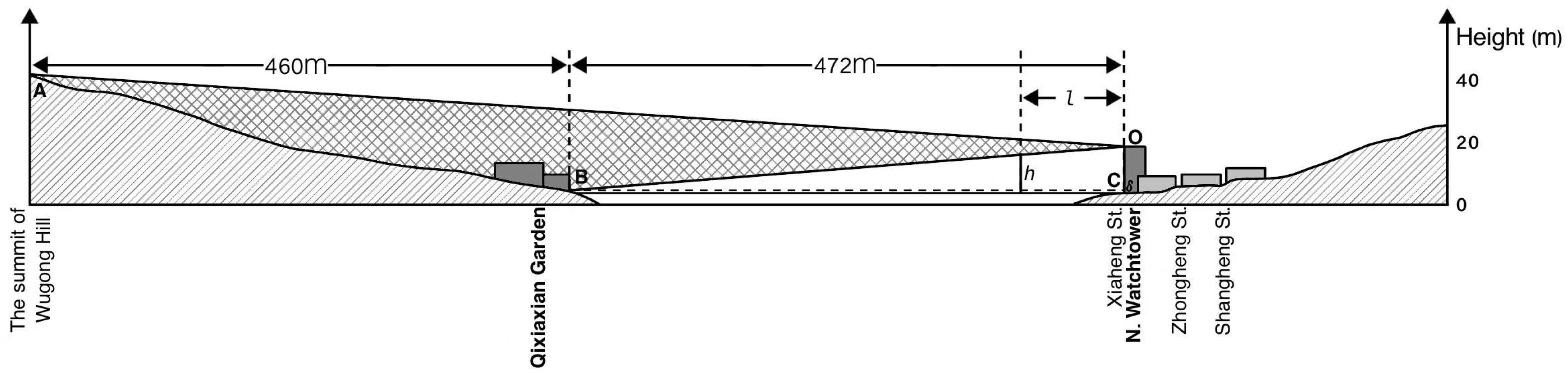

4.2. The Adjustment Proposal of the Buffer Zone Boundary Based on Visual Corridors

4.3. The Adjustment Proposal of the Buffer Zone Boundary Based on Water System Integrity

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. The Operational Guidelines for the World Heritage Committee. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide77a.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Yang, Y. Research on Buffer Zone Design of Luoyang Southeast and Southwest Historical Block D; Jiangnan University: Wuxi, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. World Heritage and Buffer Zones. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/series/25/ (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Jin, C.; Ma, F. From the Perspective of Holistic Protection of Historical Blocks Research on the Concept and Theory of “Buffer Zone”. Archit. Cult. 2023, 8, 129–131. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, B.; Li, B.; Dou, J. Analysis on the Delimitation Basis of Cultural Relics Protection Division. Intell. Build. Smart City 2020, 11, 120–121. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Y. Several Thoughts on the Protection Zoning of Cultural Relics Units. Identif. Apprec. Cult. Relics 2021, 12, 97–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, X.; You, T. Construction Control Zones Delineation Based on Visibility Analysis: A Case Study of Three Cultural Relics Protection Units in Baoji City. In Proceedings of the Annual National Planning Conference 2014, Haikou City, China, 13–15 September 2014; Urban Planning Society of China, Ed.; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2014; pp. 314–325. [Google Scholar]

- National People’s Congress Standing Committee. Urban and Rural Planning Law of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.npc.gov.cn/zgrdw/npc/xinwen/lfgz/zxfl/2007-10/28/content_373842.htm (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China. Urban Purple Line Management Measures. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2004/content_62888.htm (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- ICOMOS. Charter for the Preservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas. Available online: https://people.utm.my/lylai/wp-content/uploads/sites/630/2017/06/Washington-charter.1.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Hettner, A. Die Geographie, Ihre Geschichte, Ihr Wesen und Ihre Methoden; Wang, L., Translator; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2009; p. 135. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, C.O. The Morphology of Landscape. In Land and Life: A Selection from the Writings of Carl Ortwin Sauer; Leighly, J., Ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2024; pp. 315–350. [Google Scholar]

- Abrar, N. Contextuality and Design Approaches in Architecture: Methods to Design in a Significant Context. Int. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 294–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hebbert, M. Figure-ground: History and Practice of a Planning Technique. Town Plan. Rev. 2016, 87, 705–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yuichi, F.; Morris, M. Study on the buffer zone of a Cultural Heritage site in an urban area: The case of Shenyang Imperial Palace in China. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 9, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chizfahm Daneshmandian, M.; Behzadfar, M.; Jalilisadrabad, S. The Efficiency of Visual Buffer Zone to Preserve Historical Open Spaces in Iran. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 52, 101856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarihan, E. Visibility Model of Tangible Heritage. Visualization of the Urban Heritage Environment with Spatial Analysis Methods. Heritage 2021, 4, 2163–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi, H.; Homa, I.B.; Shokoohi, S.; Shokoohi, S. Perceptual buffer zone: A potential of going beyond the definition of broader preservation areas. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 3, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zheng, L.; Chen, Y.; Feng, J.; Zheng, J. Recognition of Damage Types of Chinese Gray-Brick Ancient Buildings Based on Machine Learning—Taking the Macau World Heritage Buffer Zone as an Example. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbey, V. Sümela Manastırı Kültürel Mirası için Tanımlanması Gereken Miras Alanı ve Tampon Bölgesine Yönelik Öneriler. Selçuk Üniversitesi Edeb. Fakültesi Derg. 2021, 45, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Gao, H. Analysis of the Delimitation Principles and Management Strategies for the Buffer Zone of the World Heritage Site Hailongtun. China Cult. Herit. 2018, 2, 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.P.; Mendonça, P.; Ramísio, P.J. Heritage Buildings as a Contribution to the Contemporary City: The Relocation of Braga’s District Archive. J. Archit. Urban. 2020, 1, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, M.; Noor, S.M.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Perception of young local residents toward sustainable preservation programmes: A case study of the Lenggong World Cultural Heritage Site. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causevic, A.; Salihbegovic, A.; Rustempasic, N. Integrating New Structures with Historical Constructions: A Transparent Roof Structure above the Centrally Designed Atrium. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 11, 112102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tian, M. The Annals of Xiangshan County; Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2015; p. 1331. [Google Scholar]

- XU, X. Protection and Revitalization of Traditional Ancient Village Based on Landscape Gene Recognition and Expression: Taking Huitong Village in Zhuhai as an Example. Urban Archit. Space 2023, 11, 75–77. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Peng, C. Spatial Form of Traditional Village in the Pearl River Delta in Syntactical View: A Case Study of Nancun Village in Panyu, Guangzhou. Archit. Cult. 2023, 8, 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Li, X. Study on the Public Space Form of Traditional Cantonese Village: The Case of Guangzhou Panyu. South Archit. 2013, 4, 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S. Discussion on the “113445” Framework in the Textbook of Human Geography. China Univ. Teach. 2018, 8, 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Kong, D. Urban historic heritage buffer zone delineation: The case of Shedian. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Coming Home to China; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2007; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- China Science and Technology Terminology Committee. Chinese Terms in Urban and Rural Planning; Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2021; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. The Control of Urban Fifth Façade Based on Visual Corridor: A Case Study of Beijing. In Proceedings of the Annual National Planning Conference 2021, Chengdu, China, 25–27 September 2021; Urban Planning Society of China, Ed.; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2021; pp. 539–549. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, C.; Wu, L. Zheng Gongren’s Epitaph: Several Aspects of Social Life in Lingnan. Root Explor. 2020, 2, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. A Study on Rural Women in Guangdong Amid Regional Social Changes During the Ming and Qing Dynasties; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2016; pp. 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Li, J. A Case Study on Guangfu Village: The Figures and Buildings during Modern Rural Constructions in Huitong Village, Xiangshan County. New Archit. 2021, 06, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Xu, Y. Modern Village Planning in Jinding Town, Zhuhai City: Research on the Protection and Development of Huitong Village. Collect. Pap. Archit. Hist. 2002, 2, 226–237+294. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, C.; Wu, L. Study on Qixiaxian Garden, a Dilapidated Western-Style Mansion in Zhuhai. Root Explor. 2021, 3, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation Concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000158388 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Foucault, M. Of other spaces: Utopias and heterotopias (1967). In The Semiotic Challenge; Barthes, R., Ed.; Hill and Wang: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 420–426. [Google Scholar]

- The People’s Government of Panyu District, Guangzhou City. The Protection Plans for the Two Historical and Cultural Villages (Daling Village and Tanshan Village) Were Reviewed and Approved by the Municipal Committee for Historic Cities. Available online: https://www.panyu.gov.cn/zwgk/zfxxgkml/xxgkml/zwdt/bmdt/sghhzrzyjfzqfj/content/post_9950254.html (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Schlee, B.M. The role of buffer zones in Rio de Janeiro urban landscape protection. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 7, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuhai Natural Resources Bureau. The Protection Plan of Huitong Village in Zhuhai Joint Protection Plan for Historical and Cultural Blocks in Guangdong Province (2021–2035). Available online: https://zrzyj.zhuhai.gov.cn/ywxx/ndjh/content/post_3777618.html (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Wang, X. The Role of Buffer Zones in World Heritage preservation: A Case Study of the Liangzhu Site. China Cult. Herit. 2020, 6, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Crvera, J.C. De lo faínadé a lo efímero la arquitectura moderna ante el paso del tiempo. In Criterios de Intervención en el Patrimonio Arquitectónico del siglo XX: Conferencia Internacional CAH20thC, Madrid, 14, 15 y 16 de Junio de 2011 = Intervention Approaches in the 20th Century Architectural Heritage: International Conference CAH20thC; Madrid, Spain, 14–16 June 2011, Domingo, M., Muíña, I., Eds.; Ministerio de Cultura: Madrid, Spain, 2011; pp. 259–264. [Google Scholar]

| Name | Main Damage Phenomena |

|---|---|

| Single-arch bridge 1,3 | It has been modified recently |

| The North Gate 1,3 | Its wall is dry and alkaline, its door panel and latch are missing, and recently it has been fixed with a steel structure |

| Diaomei Ancestral Temple 1,3 | It has been modified recently |

| Huitong Ancestral Hall 1,3 | It has been renovated recently and the wall surrounding the North Watchtower is missing |

| The North Watchtower 1,3 | It is basically in good condition, and its internal stairs are damaged |

| Mo Families’ Ancestral Hall 1,3 | It has been modified recently |

| Shaolu House 2,3 | It is basically in good condition, and recently its walls were renovated |

| Jilu House 1,3 | It has been modified recently |

| Huitong Academy 1,3 | It is basically in good condition, and its walls were repainted |

| The South Watchtower 1,3 | It is basically in good condition, and its walls have water stains |

| The South Gate 1,3 | Its wall is dry and alkaline, its door panel and latch are missing, and recently it has been fixed with a steel structure |

| Rubin Mo Ancestral Temple 2,3 | It is basically in good condition, with a wire connector on the wall |

| Mo Families’ Mansion 1,3 | It is basically in good condition |

| Qixiaxian Garden 1,3 | It is basically in good condition, and its walls have water stains |

| Altar of God of Land and Grain 4 | It has been modified recently |

| The Ruins of Yangyunshan House 4 | Only its ruins remain, and its internal functions have become a parking place for sanitation facilities such as garbage trucks |

| Shiyang Mo’s former residence 4 | Only its foundation remains, and it completely transforms into public space |

| Ancient village walls 4 | Only a small section of the ruins of it, three or four meters long and 20 cm high, is left, and the damage is so severe that it may collapse at any time, with traces of modern people fixing it. |

| Temple of Zhangwangye 4 | There are no sites or visual and written materials; only the words of it remain as oral history |

| Wenchang Pavilion 4 | There are video and written materials about it |

| Element | Order Number | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Hui River | ① | Natural runoff sources |

| Drainage ditch | ② | Flood discharge channel modified from natural river |

| The Long Pond | ③ | Collecting slope runoff from the mountains as a source of water for irrigation |

| well | ④ | One of the village’s living water sources in the past (now abandoned) |

| Water outlet | ⑤ | Connecting Hui River, drainage ditch, and the Long Pond |

| Watercourse | ⑥ | The drainage channels in the village are mainly distributed along the streets and alleys |

| sewage disposal system | ⑦ | Treating domestic sewage in the village |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, S.; Zou, Y.; Zang, S. Exploring the Delineation Methods for Buffer Zones of Historical and Cultural Villages from a Perspective of Cultural Geography: A Case Study of Huitong Village in Zhuhai, China. Heritage 2025, 8, 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090394

Zhou S, Zou Y, Zang S. Exploring the Delineation Methods for Buffer Zones of Historical and Cultural Villages from a Perspective of Cultural Geography: A Case Study of Huitong Village in Zhuhai, China. Heritage. 2025; 8(9):394. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090394

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Shangyi, Yusheng Zou, and Siyuan Zang. 2025. "Exploring the Delineation Methods for Buffer Zones of Historical and Cultural Villages from a Perspective of Cultural Geography: A Case Study of Huitong Village in Zhuhai, China" Heritage 8, no. 9: 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090394

APA StyleZhou, S., Zou, Y., & Zang, S. (2025). Exploring the Delineation Methods for Buffer Zones of Historical and Cultural Villages from a Perspective of Cultural Geography: A Case Study of Huitong Village in Zhuhai, China. Heritage, 8(9), 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090394