1. Introduction

The interpretation and accessibility of cultural heritage sites often remain confined to their physical locations, limiting the ability of remote audiences to engage with their stories. Traditional methods of heritage interpretation, such as guided tours, static images, or textual descriptions, while valuable, do not fully harness the potential of modern immersive technologies. Technologies like 360-degree panoramic tours, virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), mixed or extended reality (XR) and interactive digital twins are transforming how heritage sites are presented and experienced, making them more accessible to a global audience. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the adoption of such technologies, as physical visits to heritage sites became restricted. In response, museums, galleries, and heritage institutions turned to virtual experiences to maintain public engagement and reach a broader audience. In this context, immersive technologies have emerged as a powerful solution for enabling virtual visitation, providing not just visual access but deeper interpretive experiences [

1]. These tools allow users to navigate cultural sites, explore intricate details, and access multimedia content that enriches their understanding of the site’s historical and cultural significance.

This paper explores two case studies where 360-degree panoramic tours and immersive technologies have been implemented to enhance heritage interpretation: the Understory Art and Nature Trail in Northcliffe, Western Australia, and the Subiaco Hotel, a State Heritage Listed building in Perth, Western Australia. The Understory Art Trail project demonstrates how remote art installations can be made accessible to a global audience using 360-degree panoramas, photogrammetry, and AR applications. Similarly, the Subiaco Hotel case study highlights how immersive technology can be used to preserve and interpret built heritage through interactive 360-degree tours.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate how these technologies have been applied in different contexts to improve access, engagement, and interpretation. By examining the workflows, methodologies, and tools used in these projects, this study aims to identify best practices and the long-term impact of immersive technology on heritage tourism and education. A key research gap remains: few studies [

2,

3,

4,

5] have compared different platforms in heritage contexts, especially with attention to diverse audiences and user feedback. To address this, the paper asks: (1) How do different immersive platforms influence accessibility, interactivity, and visitor engagement? (2) What workflows and design choices shape their effectiveness? (3) What lessons can guide sustainable and responsible digital heritage practice? This study contributes by providing comparative evidence across two platforms, situating findings within the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), and offering practical recommendations for heritage practitioners.

2. Background and Related Works

Heritage interpretation has historically relied heavily on physical presence and direct interaction between visitors and cultural sites, typically facilitated through guided tours, textual narratives, static visual displays, and conventional audio guides. While effective within certain contexts, these traditional interpretive approaches inherently limit audience engagement, particularly regarding geographical reach, physical accessibility constraints, and evolving visitor expectations especially among digitally native younger audiences.

Recent global developments, most notably the digital transformation accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, have significantly altered the landscape of cultural heritage management and visitor engagement [

6]. Heritage institutions worldwide faced unprecedented disruptions during this period, highlighting the limitations of in-person-dependent interpretive methods. Closures of physical spaces, coupled with increased public demand for remote and accessible experiences, underscore the necessity for innovative technological solutions capable of bridging geographical barriers and fostering inclusive participation [

7].

Immersive technologies, particularly 360-degree panoramic tours, virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and digital twins, have emerged as powerful tools addressing these challenges [

8]. These technologies offer dynamic, interactive, and richly informative virtual experiences that transcend traditional barriers, engaging diverse and dispersed audiences. Furthermore, immersive platforms align effectively with contemporary visitor expectations for interactive, personalized, and digitally enhanced cultural encounters, thus providing heritage institutions a means to remain relevant and competitive in a rapidly evolving digital era.

2.1. Previous Studies

Existing literature on immersive technologies in heritage interpretation provides valuable insights into their potential benefits yet often lacks rigorous methodological evaluation. For example, Sarkady et al. [

9] highlight significant improvements in visitor engagement facilitated by interactive multimedia elements within virtual tours. However, these conclusions rely heavily on self-reported visitor experiences, introducing subjectivity and potential biases such as social desirability effects, which could skew reported satisfaction and engagement measures [

10,

11].

Similarly, Shehade and Lambert [

12] emphasize the effectiveness of VR and 360-degree tours in enhancing user comprehension of museums and architectural heritage sites. Their study provides valuable qualitative insights into how museum professionals engage with VR and 360-degree tours, contributing significantly to the understanding of professional perspectives. However, because their focus was primarily on museum professionals, the findings may not fully reflect the experiences of broader or less digitally skilled audiences, such as casual visitors. This highlights an opportunity for further research that complements professional viewpoints with diverse visitor perspectives.

Moreover, research by Boukerch et al. [

13] discusses the educational benefits of digital twins combined with AR and VR technologies, underscoring their potential for interaction with fragile or inaccessible artefacts. Yet, their analysis could be enriched through empirical assessments of actual learning outcomes, including comparative studies of digital versus traditional educational methods. Additionally, concerns have been raised about historical accuracy and authenticity in digital representations, as digital reconstructions can inadvertently oversimplify or misrepresent complex cultural narratives [

14].

Champion and Hiriart [

15] further argue that while immersive technologies enhance visual experiences significantly, they often overlook other sensory dimensions critical to comprehensive heritage experiences, such as auditory and tactile feedback. This critique highlights a gap in fully immersive, multisensory experiences, suggesting future research should explore holistic sensory integration within virtual heritage interpretation.

Overall, existing research establishes foundational benefits of immersive technologies, yet methodological rigour remains inconsistent. Comprehensive analyses of long-term impacts, demographic differences, sensory integration, historical accuracy, and objective engagement metrics are essential for a nuanced understanding of their effectiveness and applicability across diverse heritage contexts.

2.2. Expanding on the Research Gap

While existing research broadly acknowledges potential benefits and initial positive responses to immersive technologies, critical gaps remain. One significant limitation is the limited understanding of long-term impacts on visitation rates and broader cultural tourism trends. Most studies concentrate on immediate or short-term reactions, leaving sustained effects largely unexplored [

11,

16].

Additionally, there is a notable scarcity of comparative evaluations between technological platforms, such as 3DVista and Google Street View. Each platform has unique strengths and limitations regarding interactivity, multimedia integration, accessibility, and interface intuitiveness [

17]. However, comparative assessments addressing user experience and satisfaction across these platforms are still relatively rare, leaving an opportunity for future research to provide a stronger evidence base to help heritage institutions [

18].

Furthermore, research on visitor behaviour and perception analytics within virtual heritage experiences remains relatively underdeveloped. Detailed behavioural studies using metrics like navigation patterns, dwell times, content interaction frequencies, and engagement levels remain sparse [

8]. This absence restricts comprehensive insights into visitor interactions and their educational or cultural appreciation outcomes.

2.3. Theoretical Lens—Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

This study applies the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) as a concise theoretical frame. TAM explains why users adopt or reject technologies. The two core constructs are perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) [

19]. PU is the degree to which a system improves outcomes. PEOU is the degree to which it is free of effort. Both shape user attitudes and adoption [

20].

Recent studies demonstrate the relevance of TAM in digital heritage. Kang et al. [

21] applied TAM, incorporating cultural awareness, to study AR-based heritage education. Li et al. [

22] integrated TAM with Generic Learning Outcomes to explain user engagement in cultural exhibitions. Liu and Sutunyarak [

23] applied TAM in combination with flow theory to analyze immersive museum experiences. Jan et al. [

24] extended TAM with cultural dimensions, showing cross-cultural differences in technology acceptance.

In this paper, we adopt TAM as a conceptual framework. Google Street View illustrates high PEOU due to its simple navigation and familiar interface. 3DVista illustrates high PU because it embeds multimedia, drawings, and narratives that enrich interpretation. A full empirical TAM measurement was beyond the scope of this study, but the framework provides context for understanding our results.

2.4. Critical Comparison and Technology-Site Fit

Immersive technologies each offer distinct advantages, and their suitability depends on interpretative needs and site characteristics [

25,

26,

27]. For instance, 360-degree panoramic tours excel at capturing spatial and architectural elements, making them suitable for built heritage environments like the Subiaco Hotel [

17].

Conversely, AR and digital twins effectively enhance interpretation in environments demanding dynamic, interactive contextual experiences, such as the Understory Art Trail. AR allows real-time digital overlays on physical environments, enriching visitor experiences with narrative depth and interpretative layers. Digital twins complement these experiences by offering precise digital replicas for interactive learning. Combining multiple technologies may further enrich visitor experiences by leveraging complementary strengths.

2.5. Depth in Addressing Technological Limitations

While immersive technologies offer substantial benefits, significant technological limitations persist, such as resource constraints among small-scale institutions, usability, inclusivity, and accessibility issues [

12,

25]. Complex interfaces may exclude older visitors or those with limited digital literacy, undermining accessibility goals. Internet accessibility also remains a challenge, especially in rural or remote areas [

28].

Demographic inclusivity and digital literacy concerns are pronounced among digitally disadvantaged groups. Institutions must prioritize inclusive design practices, such as simplified navigation, captioning, voice commands, and multi-language options, effectively bridging digital divides [

11,

29].

2.6. Synopsis

This literature review underscores the transformative potential and critical importance of immersive technologies in reshaping heritage interpretation, emphasizing their capacity to enhance visitor engagement, accessibility, and educational value significantly. Nevertheless, this study also highlights substantial methodological and analytical limitations, including reliance on subjective assessments, limited demographic consideration, insufficient comparative analyses, and an overall scarcity of objective metrics. Bridging these gaps requires rigorous, methodologically sound investigations incorporating mixed-method approaches, practical implications, and user studies.

This paper critically examines how two specific heritage sites in Western Australia, the heritage-listed Subiaco Hotel in Perth and the outdoor Understory Art and Nature Trail in Northcliffe. It has leveraged 360-degree panoramic tours and immersive technologies to enhance heritage interpretation, accessibility, and visitor engagement. By analyzing these cases, the research will try to explore the effectiveness of platforms such as 3DVista and Google Street View, considering their unique impacts and limitations within indoor and outdoor heritage contexts. While reviewing the findings, this study will provide practical insights and recommendations for heritage institutions aiming to adopt similar digital innovations.

3. Research Design and Methods

This study applies 360-degree panoramic tours to two distinct heritage sites: the Understory Art and Nature Trail and the Subiaco Hotel. By detailing the workflows and technological processes, this section outlines the step-by-step approach used to document, interpret, and virtually present these sites.

3.1. Workflow of 360-Degree Panoramic Tours

The workflow for both projects followed a systematic approach, with slight variations in specific tools used for post-processing and tour development. Below is the step-by-step methodology:

Detailed planning was conducted to determine which areas of each site would be captured and documented using 360-degree panoramic photography. For the Understory Trail, locations with high foot traffic and significant art installations were prioritized. For the Subiaco Hotel, key architectural spaces were chosen to showcase the hotel’s heritage features.

For the Understory Trail, A Ricoh Theta Z1 camera was used to capture more than 250 high-resolution (8K), 360-degree images of the trail and the surrounding environment. Two GPS tracking devices (Garmin eTrex) were used to obtain precise positions under dense foliage. These images were linked together to create a virtual walking tour. For the Subiaco Hotel, A Ricoh Theta X camera (with in-built GPS) was used to document the hotel. Photos were taken at intervals, with HDR settings enabled to capture vivid colours and details.

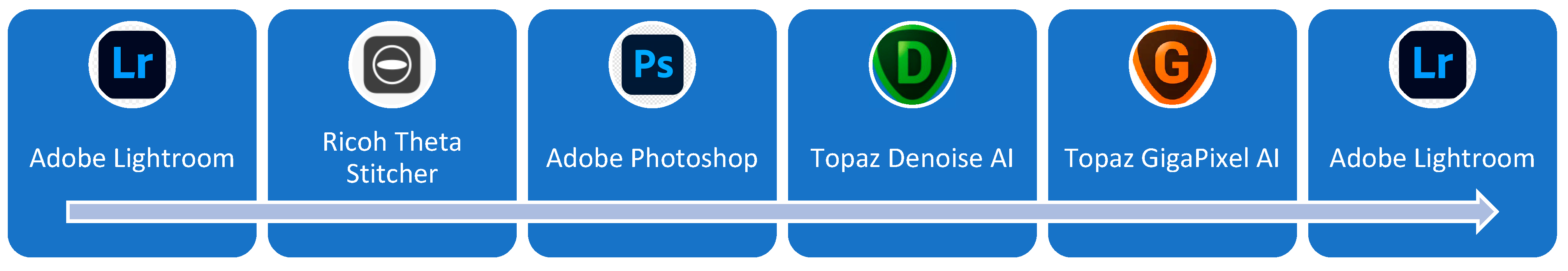

Image post-processing was performed through following a sequence as illustrated in

Figure 1. The panoramic images were processed in Adobe Lightroom for colour correction and exposure adjustments. Adobe Photoshop was used for stitching images, removing tripods, and enhancing details. For noise reduction and upscaling—Topaz Denoise AI was used to reduce image noise, followed by upscaling to 8K resolution using Topaz GigaPixel AI. This ensured that the final images were sharp and detailed, suitable for high-resolution VR tours.

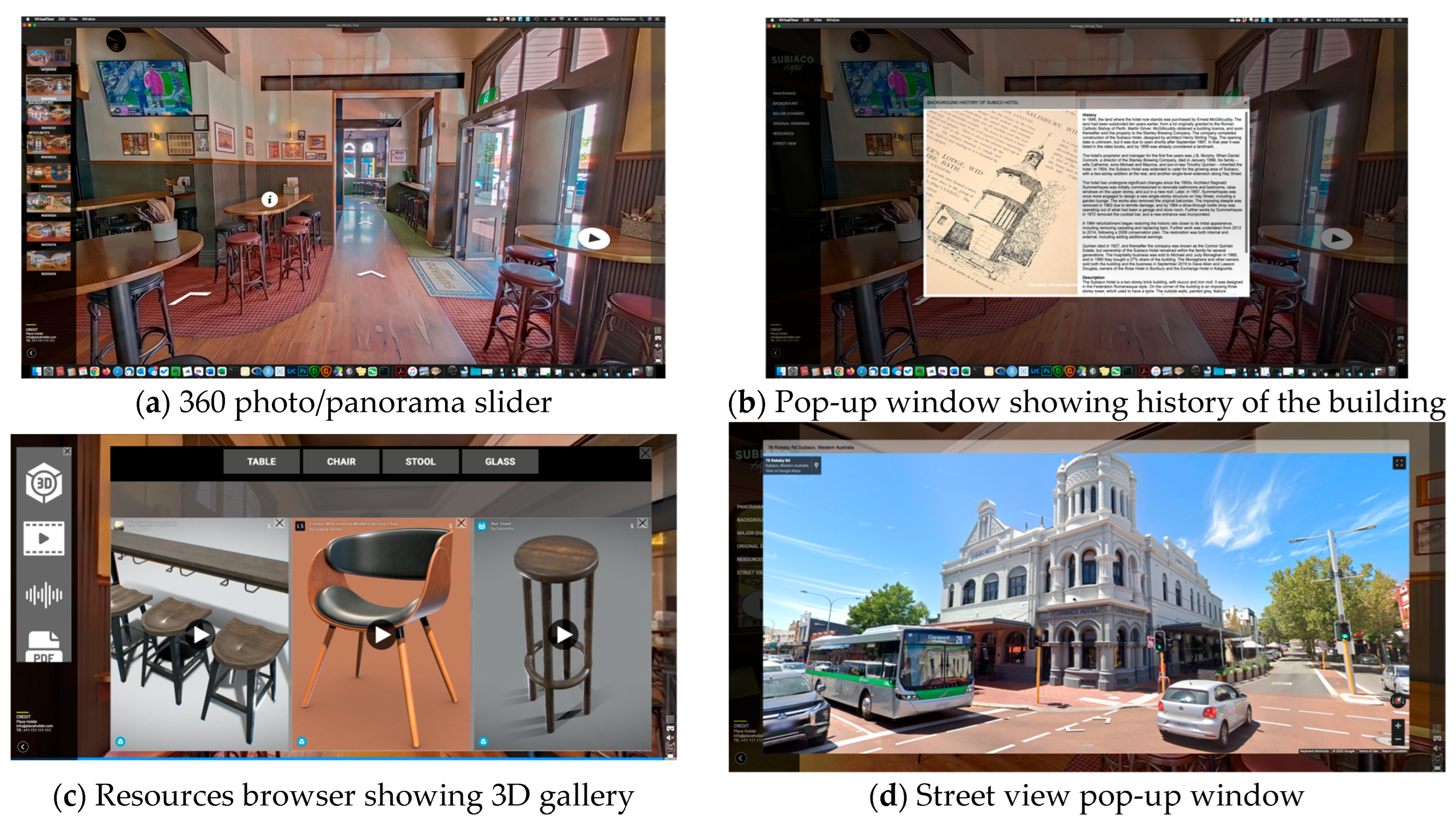

Primarily 360 panoramic photos are integrated with GSV for online public access. For the Subiaco hotel architectural drawings, historical photographs, and videos were embedded into the 360-degree tour using 3DVista. Hotspots were created at key locations, allowing users to click on various points to learn more about the site’s history and architecture. In addition to panoramic photos, the interactive AR booklet and online 3D models exhibit were created for Understory Trail.

The virtual tours were hosted on two platforms: Google Street View for both the Understory Trail and Subiaco Hotel, making them accessible to a wider audience. A dedicated server was selected to offer a customized user experience built through 3DVista for the Subiaco Hotel.

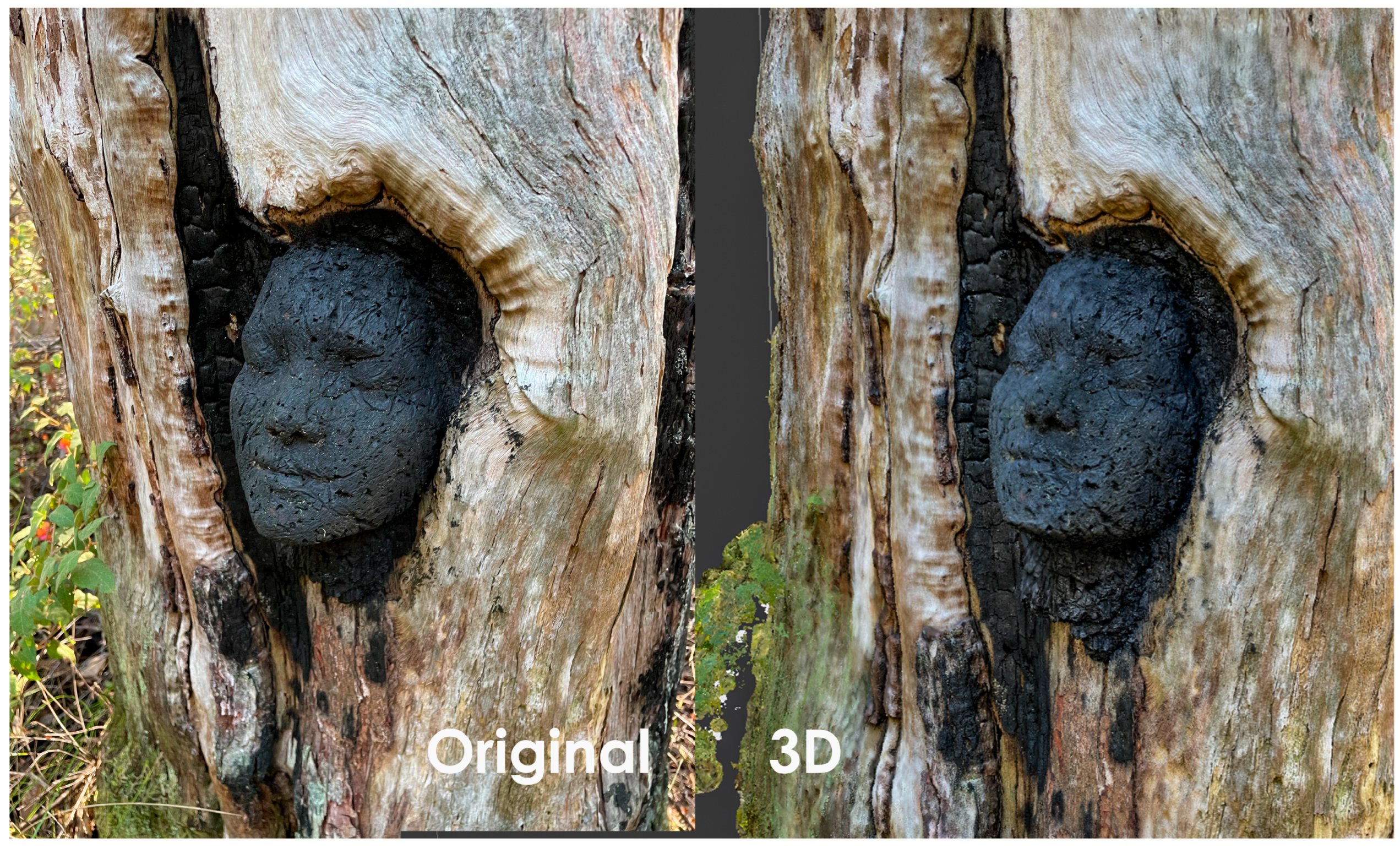

3.2. Augmented Reality and Digital Twin Creation

The Understory Art and Nature Trail utilized AR and digital twin technologies to enhance the user experience. Photogrammetry was employed to create detailed 3D models of selected installations. These digital twins were accessible online 24/7, allowing remote users to interact with the models by zooming and rotating them. Additionally, an AR app was developed using Unity (2020.3.23f1) and Vuforia (engine 10.3), enabling users to visualize 3D models by scanning printed markers. This provided a more immersive and interactive experience for users, aligning with heritage interpretation goals.

3.3. Data Collection and User Feedback

User feedback and visitor metrics were collected for both projects. For the Understory Trail, Google Analytics tracked interactions with the 360-degree tour. Metrics included total visits, average session duration, bounce rates, and hotspot click frequencies. For the Subiaco Hotel, internal platform logs captured similar measures. These metrics were used to identify areas of high engagement and content that retained users’ attention.

To complement usage analytics, guided discussions were conducted with 12 participants, including six cultural heritage professionals and six general users who had interacted with the virtual tours. Each discussion lasted approximately 30~45 min and followed an open-ended format that focused on usability, clarity of embedded multimedia, and perceived interpretive value. The transcripts were examined through thematic analysis to identify recurring patterns and insights, which were then compared across participant groups.

This mixed-method approach, combining quantitative metrics with qualitative insights provided a more holistic evaluation of accessibility, engagement, and interpretation across the two case studies.

4. Case Studies

4.1. The Understory Art and Nature Trail

The Understory Art and Nature Trail is a 1.2 km bushland trail located in Northcliffe, Western Australia, featuring various art installations embedded in nature. The primary goal of this project was to enhance the accessibility of the trail and its artworks through digital and immersive technologies. This was particularly important given the regional and remote nature of the site, which made it difficult for a broader audience to experience the installations in person.

Given the increasing demand for virtual engagement, the project focused on creating a digital experience that allowed remote visitors to explore the trail and interact with the artworks. While COVID-19 travel restrictions accelerated the uptake of such solutions, the longer-term justification lies in broader technological advancements, evolving visitor expectations for interactive heritage, and the particular needs of geographically remote sites such as the Understory Art Trail. A three-step process was developed in consultation with stakeholders, shaped by financial limits, available hardware, and network constraints.

Step one: Study, review, and explore methods and tools

Identify the most suitable digital interpretive methods for the site.

Get approval of the proposed interpretive method from the authority.

Liaison with authority and define phasing of the project based on the budget.

Step two: Testing and development of the workflow

Develop an extensive list of desktop and online 360-degree VR software and platforms.

Identify and list the supporting interactive features (such as embedded text, audio, images, 3D, etc.) suitable for storytelling and interpretation.

Develop an optimized workflow from 360-degree capturing to VR tour development.

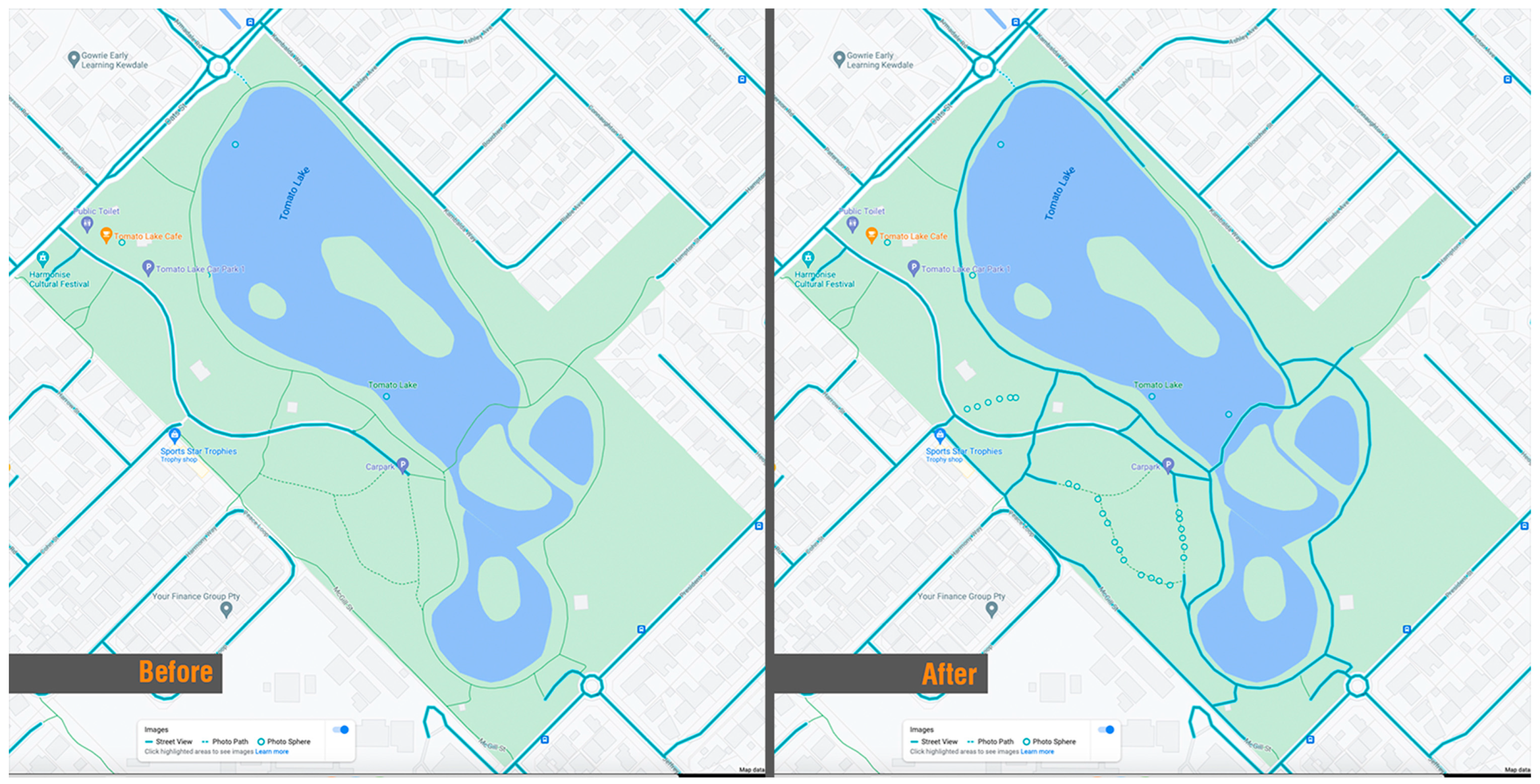

Conduct a pilot study (

Figure 2) and test the workflow at a similar site (Walk trail at Tomato Lake, Belmont, WA, Australia) and integrate the tour at Google Street View.

Figure 2.

The pilot study of adding VR accessibility (blue lines) at Google Street View, Tomato Lake Park, Belmont, WA, Australia.

Figure 2.

The pilot study of adding VR accessibility (blue lines) at Google Street View, Tomato Lake Park, Belmont, WA, Australia.

Step three: Implementation of the workflow and future planning

Digitize the art gallery and the 1.2 km long trail with 360-degree panoramic photographs and 360-degree videos.

Develop and host the interactive 360-degree virtual tours at a dedicated server.

Link/embed the VR tours and 360-degree panoramas with Google Maps and Google Street View.

Digitize selected artwork, develop prototype apps, and propose interpretation strategies for the next phase of the project.

4.1.1. Implementation and Online Access

More than 250 high-resolution photographs (360-degree) have been captured along the trail. GPS location of each camera position has been triangulated with another two GPS tracking devices (Garmin eTrex devices) to get the most accurate point under the high foliage and trees. Each photograph has been processed, stitched, colour-corrected, optimized, and finally connected as a 360-degree VR tour through a six-step workflow with five different software (mentioned in

Section 3.1).

4.1.2. Public Engagement (Training)

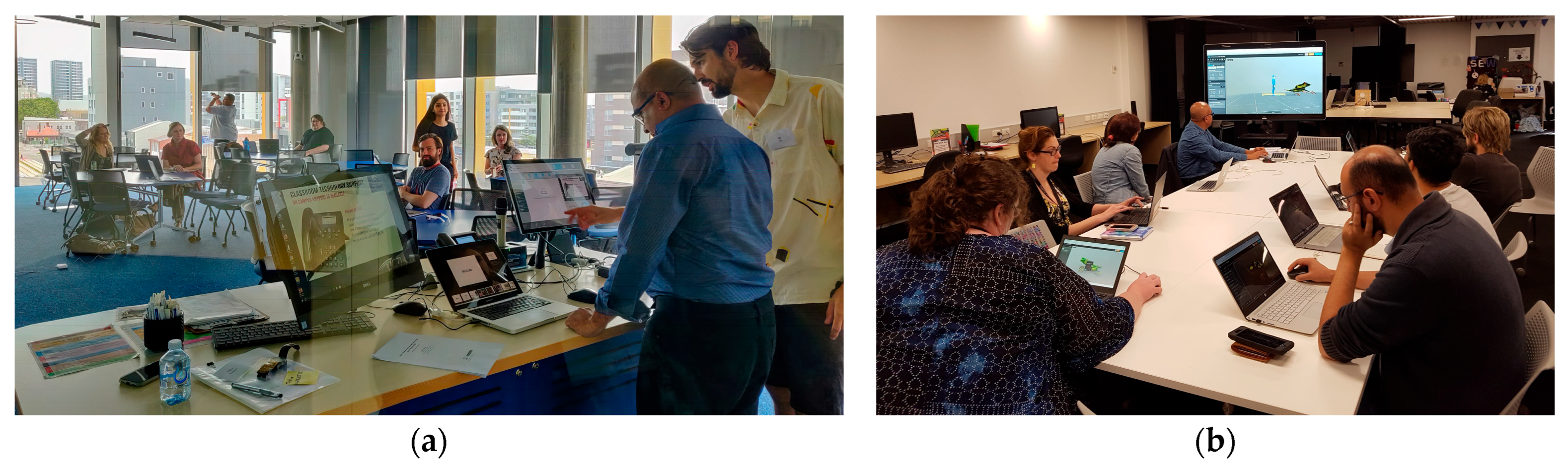

We conducted two workshops at Library Makerspace, Curtin University (Perth, Western Australia) and the University of Newcastle New South Wales) on 360-degree VR tour and 3D modelling/photogrammetry (

Figure 5). We are updating the course materials and related digital assets to support hands-on activities for a larger public workshop.

4.1.3. User Engagement (Online, Understory Art and Nature Trail)

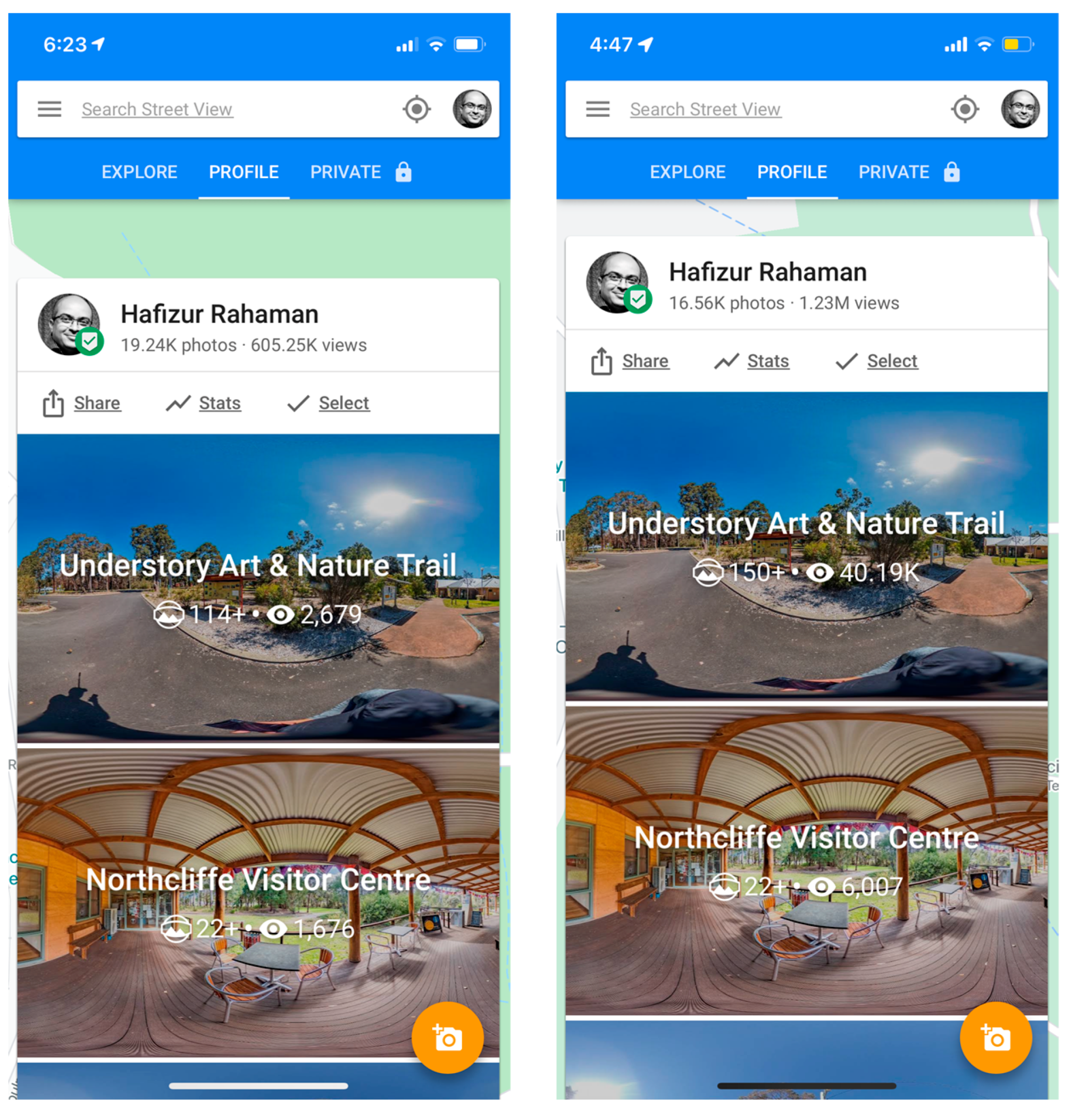

Since the Painted Tree Gallery (Visitor Centre) and the Understory Art in Nature Trail became virtually accessible through Google Street View (

Figure 6), they have proved highly successful in reaching the online audience. Within the first month of their arrival in Google Maps and Google Street View, they received 1676 and 2679 online viewers, respectively. Within 11 months, they received 6007 and 40,19 000 visitors (more at

Section 5.4).

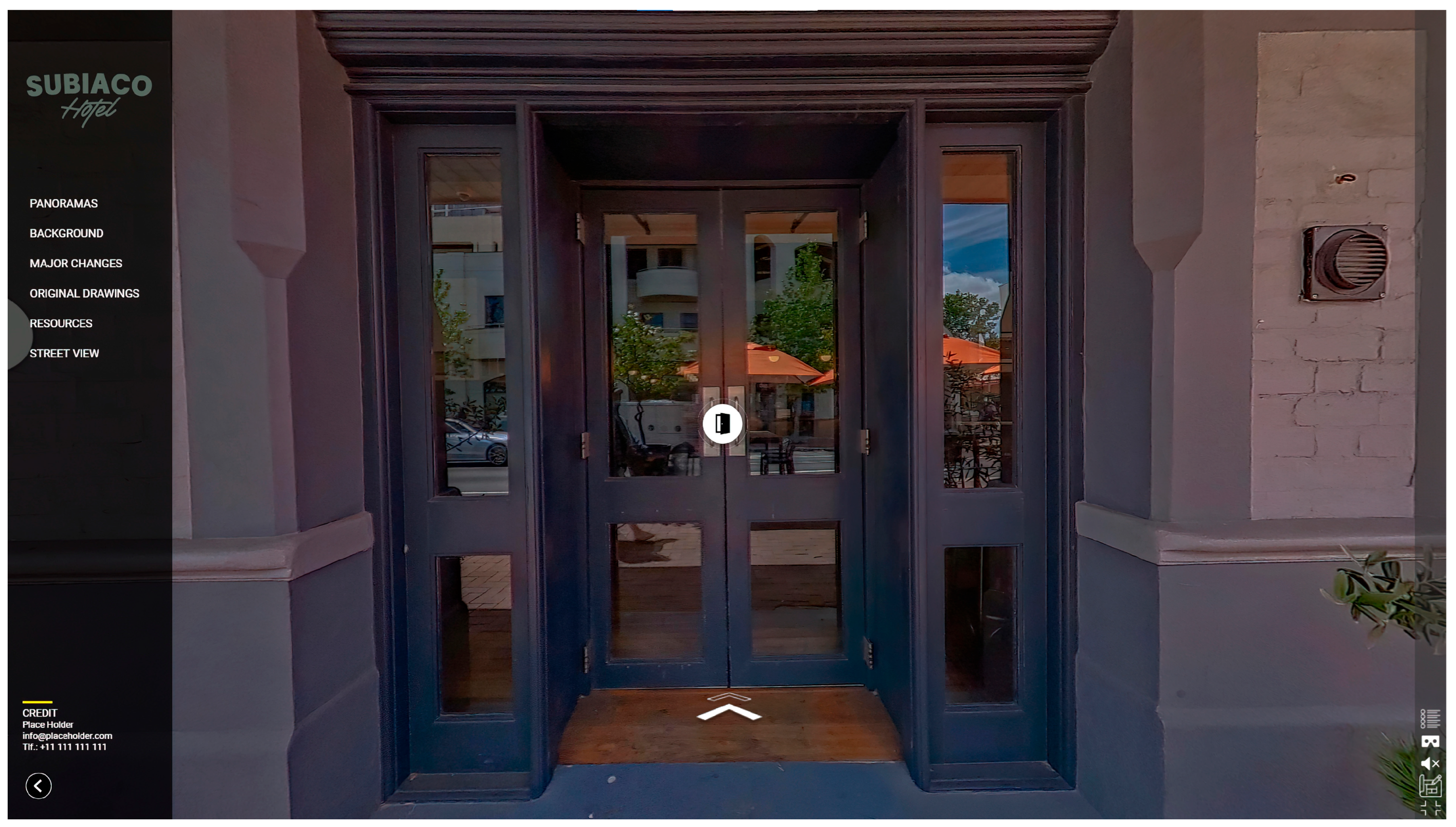

4.2. The Subiaco Hotel

The Subiaco Hotel is a heritage-listed building in Perth, Australia, known for its architectural significance. Designed by Summerhayes Architecture in the late 19th century, the hotel has served as a social and cultural hub for the local community. The objective of this project was to document and preserve the hotel’s architectural features through a 360-degree panoramic tour, making the building accessible to a global audience while preserving its heritage digitally. The project also aimed to enhance visitor interpretation by embedding historical data, architectural drawings, and multimedia into the tour. Unlike the Understory Trail, the focus here was on built heritage, emphasizing the intricate design features and historical evolution of the hotel.

A three-step work process was implemented based on the requirements of the Australian Cultural Data Engine (

https://www.acd-engine.org, accessed on 12 September 2025), financial constraints, accessible historic information and documents.

Step one: Study, review, and explore methods and tools

Identify the most suitable digital interpretive methods for the site.

Get approval of the proposed interpretive method from the authority.

Liaison with research collaborators and hotel authority about phasing and access to the site and contents.

Step two: Testing and development of the workflow

Cooperative study and list desktop and online 360-degree VR software and platforms.

Identify and list the supporting interactive features (such as embedded text, audio, images, 3D, etc.) suitable for storytelling and interpretation.

Develop an optimized workflow from 360-degree capturing to VR tour development.

Step three: Implementation of the workflow

4.2.1. Implementation and Online Access

The immersive 360-degree tour of the Subiaco Hotel highlighted key architectural spaces, such as the grand entryway, main dining area, and detailed exterior façade. Interactive hotspots were placed within the tour, linking to historical photographs, architectural drawings, and detailed descriptions of the hotel’s design and history. This allowed users to gain a deeper understanding of the hotel’s evolution over time. The 360 panoramas were upscaled to 8K resolution, ensuring that users could zoom in on details such as ornate plasterwork, stained glass, and balustrades, which are key features of the hotel’s architectural style.

4.2.2. User Engagement (Online, Subiaco Hotel)

Twenty linked panoramic 360 photos were uploaded (August 2022) to Google Street View. Within four months some of them reached more than 2500 views, while one reached more than 7000 views (

Figure 10). The prototype was demonstrated to group of five colleagues in the area and their general user feedback was collected. Overall, users had a positive impression of the 360-panoramic tours of historic buildings.

5. Results and Key Insights

Both the Understory Art and Nature Trail and the Subiaco Hotel projects successfully used immersive technologies to enhance accessibility, visitor engagement, and storytelling. However, their approaches reflected the distinct nature of each site outdoor art in a natural setting versus an indoor built heritage space. To highlight how context shapes digital heritage strategies, the table below (

Table 1) compares the two projects across key dimensions such as platform, technology, audience, and interactivity.

5.1. Interpretation Methods: Art Trail Versus Built Heritage

The Understory Art and Nature Trail and Subiaco Hotel illustrate distinct yet complementary approaches to heritage interpretation through immersive technologies. The Art Trail employed 360-degree panoramas and augmented reality (AR), supplemented by photogrammetry-based digital twins, to expand access to remote outdoor installations, enabling detailed exploration of artworks in their natural context. Conversely, the Subiaco Hotel’s 360-degree tour emphasized the site’s architectural and historical narratives, integrating multimedia elements like historical images, architectural drawings, and audio narratives to convey the hotel’s esthetic and community significance. Both approaches successfully combined immersive spatial exploration with enriched interpretive content, demonstrating effective strategies for enhancing accessibility and engagement with diverse heritage environments.

5.2. Technology Utilization: Tools and Platforms

Both the Understory Art Trail and Subiaco Hotel utilized 360-degree panoramic photography for their virtual tours, but the choice of platforms and associated technologies reflected differing priorities and limitations. The Understory Trail leveraged Google Street View effectively for broad accessibility and ease of navigation; however, this approach sacrificed some control over multimedia integration and user experience. While the project successfully incorporated augmented reality (AR) and photogrammetry to deliver interactive 3D digital twins of the artworks, this required additional user effort through printed markers and dedicated AR apps, potentially limiting user engagement. Conversely, the Subiaco Hotel’s use of high-resolution panoramas and 3DVista software provided deeper multimedia integration and narrative richness, yet the lack of AR diminished opportunities for user interactivity and immersive engagement. These contrasting technological decisions underscore the need to carefully balance accessibility, interactivity, and interpretative depth when employing immersive tools in heritage interpretation.

5.3. Audience Engagement and Reach

The two projects demonstrated contrasting approaches to audience engagement, reflecting differing strategies and platforms. The Understory Art Trail targeted a global, general audience by leveraging Google Street View, significantly increasing accessibility for users unable to physically visit the remote site. This strategy successfully attracted over 40,000 virtual visitors in its first 11 months, supported by the use of augmented reality (AR) and digital twins, that strongly appealed to younger digital audiences. However, this global approach may have compromised depth of interpretation and tailored engagement with more specialized audiences.

In contrast, the Subiaco Hotel project specifically targeted heritage professionals, historians, and architectural enthusiasts, prioritizing detailed educational content over mass appeal. While highly valued within its niche audience for its comprehensive narrative and historical richness, this approach inevitably limited its broader reach, resulting in comparatively lower overall visitor numbers.

User feedback insights further reinforce these dynamics. Heritage professionals noted that the Subiaco Hotel tour “offered a level of architectural detail I could not have appreciated even during an on-site visit,” underscoring the value of rich multimedia integration. Conversely, casual users exploring the Understory Trail highlighted its immersive appeal, with one participant remarking that it “felt surprisingly like walking in the bush while sitting at home.” At the same time, some participants suggested enhancements such as multi-language options to broaden accessibility.

These perspectives illustrate how quantitative visitor statistics were complemented by qualitative experiences, highlighting the inherent trade-off between broad accessibility and specialized interpretive depth in digital heritage initiatives.

5.4. Online Visitor Count

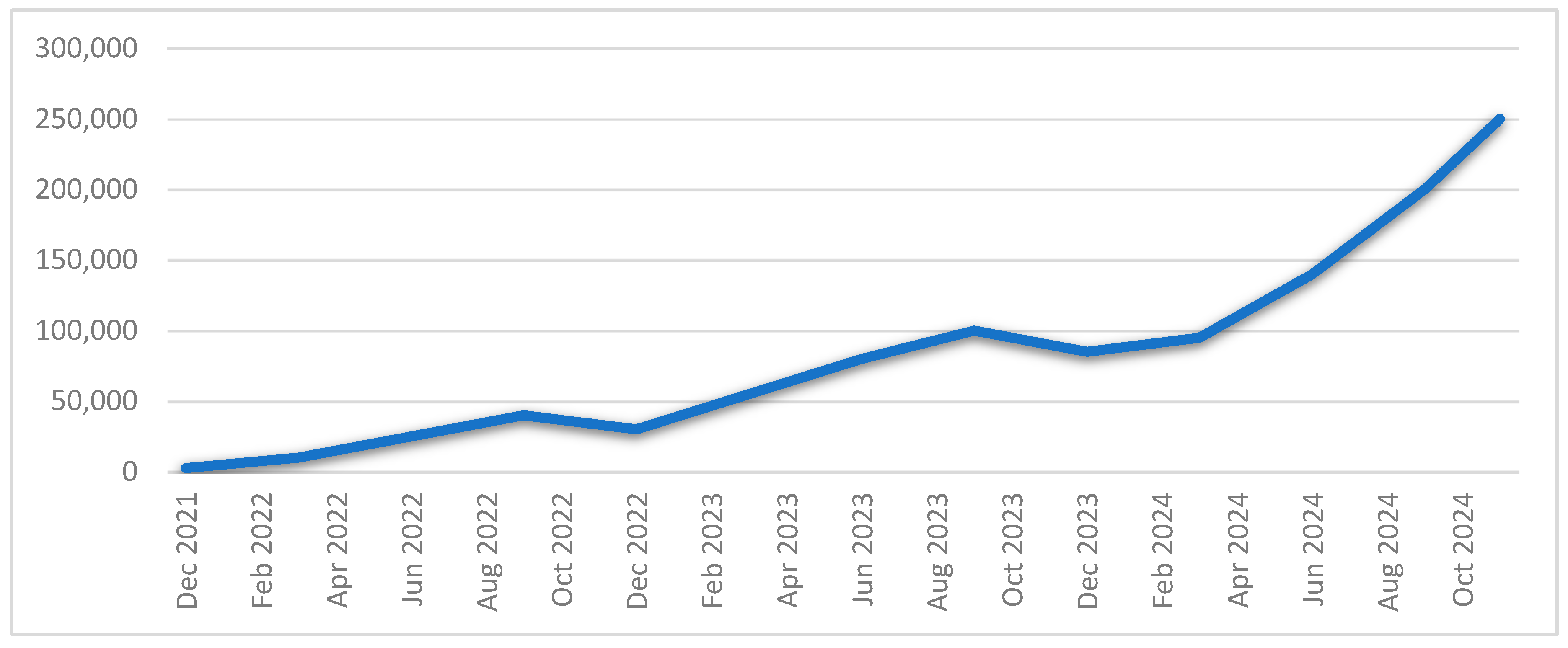

The Understory Art and Nature Trail and Subiaco Hotel projects exemplify how virtual platforms Google Street View and 3DVista can transform heritage tourism, though with markedly different trajectories. As shown in

Figure 11, the Understory Trail began with just 2679 virtual visitors in December 2021, but surged past 250,000 by November 2024, largely due to targeted digital campaigns and global interest in nature-based heritage. While this rapid growth highlights the power of online promotion, it also raises questions about the depth and sustainability of such engagement.

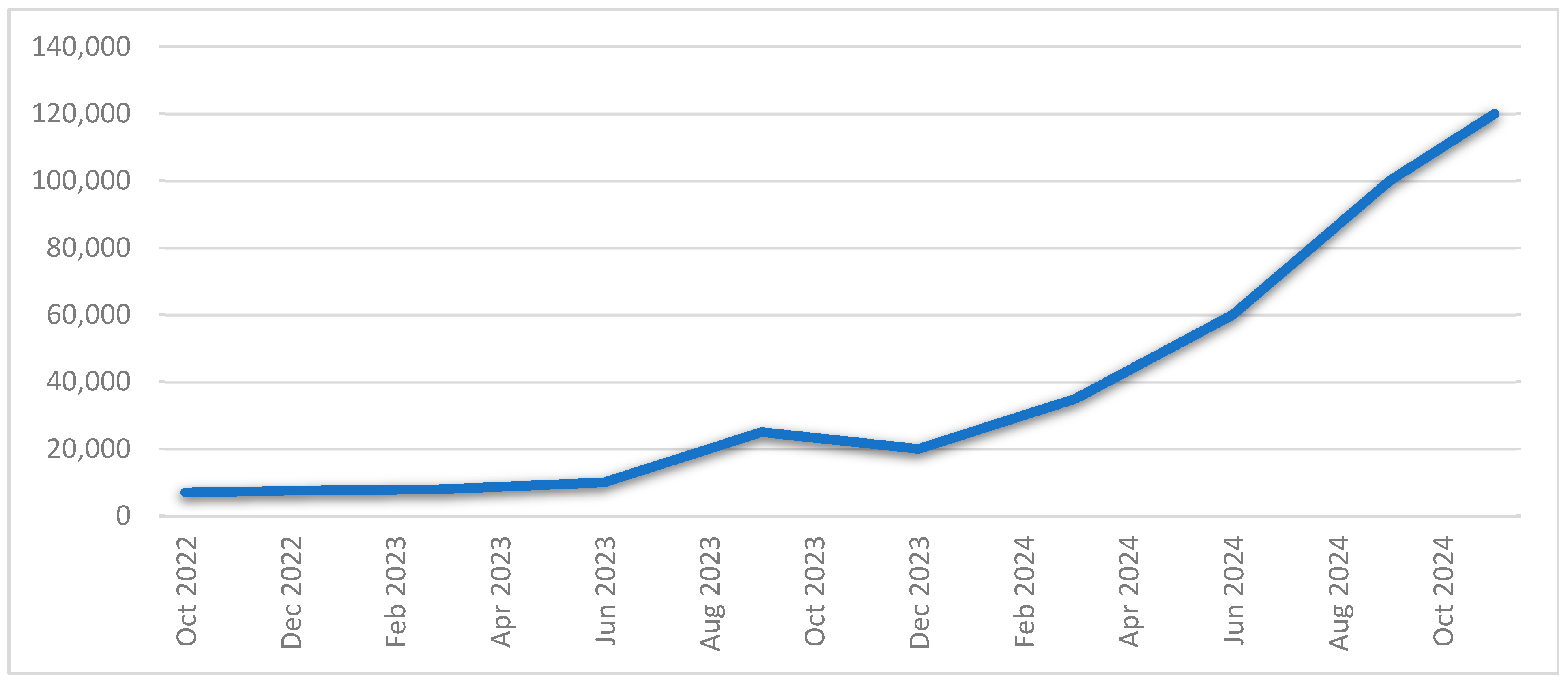

In contrast, the Subiaco Hotel project, illustrated in

Figure 12, experienced steady but more modest growth: from 7000 visitors at launch in August 2022 to 120,000 by November 2024. This pattern reflects its focused outreach to heritage professionals and enthusiasts, with notable increases linked to strategic collaborations and event-driven campaigns. Together, these trends reveal the contrasting dynamics of audience reach and engagement across different heritage contexts, emphasizing the ongoing challenge of balancing broad visibility with meaningful digital participation.

5.5. Challenges and Limitations

Both projects encountered significant challenges shaped by technological constraints and site-specific contexts. For the Understory Art and Nature Trail, technical obstacles in capturing high-quality 360-degree images and generating digital twins outdoors were pronounced. Variability in lighting, weather, and natural obstructions often compromised image consistency, while intermittent GPS connectivity complicated precise geolocation of 360-degree photographs within Google Street View. The team also faced continual adjustments due to evolving Google Street View policies, and the limited resources of a regional art trail necessitated a reliance on affordable, do-it-yourself solutions rather than advanced professional platforms. Uploading and linking high-resolution images resulted in superior visual quality; however, this process was significantly more labour-intensive and technically demanding than simply capturing and uploading 360-degree video, particularly given the limited technical expertise available.

In the case of the Subiaco Hotel, the primary challenge lay in ensuring historical accuracy amid incomplete archival records; the occasional reliance on placeholder images risked diminishing the authenticity of the virtual experience. Logistical constraints further complicated the image-capture process, as photography was restricted to periods outside hotel operating hours and indoor environments inhibited GPS-based positioning. The decision to develop a custom virtual tour platform with 3DVista introduced further complexities, including the demand for specialized technical skills, higher costs associated with private server hosting, and ongoing concerns regarding server reliability. Integrating diverse multimedia content and maintaining image quality required significant time and financial investment. Collectively, these limitations underscore the persistent tension between technological ambition, resource availability, and the practical realities of digital heritage interpretation.

6. Discussion and Interpretation

6.1. Key Findings

Both the Understory Art and Nature Trail and Subiaco Hotel projects yielded significant insights into the use of immersive technologies for heritage interpretation, accessibility, and engagement. While each project had distinct objectives, the overall results demonstrated the powerful potential of 360-degree panoramic tours and AR in enhancing both the virtual and in-person visitor experience.

One of the most impactful results of both projects was their ability to dramatically increase accessibility to the heritage sites. The Understory Art and Nature Trail, a regional, physically remote site, gained global visibility through its 360-degree panoramic tour integrated with Google Street View. In the first 11 months, the project attracted over 40,000 online visitors, far surpassing the number of physical visitors it would typically receive. This was especially important during the COVID-19 pandemic, when travel restrictions limited physical visitation. This finding aligns with Shehade and Lambert [

6], who noted that mainstream platforms expand reach but limit interpretive customization. Our results similarly show that Google Street View provided broad accessibility but constrained narrative depth, supporting earlier observations about trade-offs between access and interpretation [

11].

The Subiaco Hotel project, while catering to a more specialized audience, provided accessibility in a different form, allowing those interested in architectural heritage, local history, and conservation to explore a building that they may not have been able to visit physically. Although the overall visitor count was lower than the Understory Trail, feedback from heritage professionals and academics indicated that the 360-degree tour was a valuable educational tool. This reflects earlier findings that custom-built virtual environments often privilege depth of interpretation over broad reach [

29].

The Subiaco Hotel project focused more on embedding historical context within the 360-degree panoramic tour. This multimedia approach (with integrated architectural drawings, photos, and videos) helped users engage with the site’s historical significance in ways that a standard virtual tour could not and was especially valued by heritage professionals. However, the additional content required heavier processing, leading to longer loading times and less seamless navigation for some users. By contrast, the Understory Art and Nature Trail was built with Google Street View (GSV). This platform offered less interactivity but was directly linked with Google Maps, making it widely accessible to a global audience through a familiar interface. As a third-party, open platform, GSV provided ease of use and immediate reach but gave the project team less control over customization and interpretive depth.

Analytics and user feedback reflected these differences. For the Understory Trail, Google Analytics showed that hotspots with images were accessed more frequently than text-based descriptions, while the average time spent on the trail was influenced by the simplicity of navigation. In the Subiaco Hotel tour, feedback emphasized its interpretive depth: one heritage professional commented that the virtual experience “offered a level of architectural detail I could not have appreciated even during an on-site visit”.

Together, these insights demonstrate how platform design and feature choice shaped engagement. The Understory Trail highlighted the future potential of augmented reality and digital twins, enabling remote interaction with artworks. The Subiaco Hotel emphasized the richness of layered multimedia for specialist audiences, but with less interactivity. In line with Champion and Hiriart [

15], our analysis of 3DVista demonstrates how custom platforms enhance interpretive richness but require higher technical and financial investment. These results converge with prior research showing that interactivity drives casual engagement, while depth attracts specialist audiences [

23].

Both projects potentially contributed to education and outreach, though in different ways. The Subiaco Hotel tour became a resource for architecture and heritage students, providing detailed insights into the design and construction techniques of historic buildings. The ability to zoom in on architectural features and explore historical documents made the tour an important tool for learning and research. The Understory Trail, by contrast, offered an engaging and accessible platform for art lovers and casual visitors to explore contemporary art in a natural setting. This finding adds to earlier observations that immersive environments support informal learning when interactivity is accessible and intuitive [

22].

Findings align with TAM. Ease of use was critical for casual users, who valued the simple controls and fast loading of Google Street View. This matches the construct of PEOU. In contrast, heritage professionals valued the rich multimedia in 3DVista. They highlighted its usefulness for education and interpretation. This matches the construct of PU. Our two case studies show that platform design shifts the balance between PEOU and PU. This explains why Street View attracted a broad general audience, whereas 3DVista appealed more to specialists. These patterns are consistent with other TAM-based heritage studies [

21,

22,

23]. By extending TAM into applied heritage contexts, the study confirms how platform design mediates adoption, echoing findings in other cultural technology studies [

24].

The primary emphasis of this study was on project design, stakeholder engagement, and the technical implementation of immersive technologies. While visitor statistics and preliminary user feedback were collected to evaluate accessibility and engagement, a systematic assessment of educational or cultural outcomes was beyond its scope. Even so, this work addresses several research gaps identified in

Section 2.2. While earlier studies noted the absence of systematic visitor evaluations [

21,

22], our inclusion of user feedback provides offers preliminary insights into how diverse audiences experience immersive heritage tours. By comparing two platforms, namely Google Street View and 3DVista, across different heritage contexts, it contributes to the relatively underexplored area of comparative platform evaluation. The integration of visitor statistics with qualitative feedback also helps fill the gap in engagement analytics noted in earlier research. However, important limitations remain. Long-term impacts, demographic diversity, and large-scale behavioural data are still open areas, requiring future studies through longitudinal and cross-cultural approaches.

6.2. Recommendations for Future Projects

Drawing on the challenges, successes, and lessons from the Understory Art Trail and Subiaco Hotel case studies, the following key recommendations are proposed for future immersive heritage initiatives:

Select Platforms Strategically: Carefully match digital platforms to project goals and available resources. For projects with limited budgets or technical expertise, mainstream platforms such as Google Street View offer broad accessibility and intuitive navigation. Custom platforms (e.g., 3DVista) enable deeper, tailored engagement but require greater technical capacity and investment.

Integrate Multi-layered Interactivity: Go beyond static panoramas by embedding interactive features such as augmented reality (AR), clickable hotspots, and multimedia annotations. Combining panoramic tours with interactive 3D models or digital twins can enhance user engagement and provide richer interpretive experiences, especially for diverse or remote audiences.

Emphasize Robust Geolocation Practices: Accurate GPS tagging is essential for spatially aligning 360-degree imagery and creating coherent virtual tours, particularly for outdoor heritage sites. Managing large volumes of photographs without reliable geolocation data can significantly hinder post-processing and user navigation. It is therefore recommended to employ GPS triangulation methods supplemented by auxiliary tracking devices to ensure spatial accuracy. Additionally, teams should thoroughly test all GPS-enabled equipment and geolocation workflows prior to full-scale documentation to identify and resolve technical issues in advance, thereby streamlining the integration of spatial metadata and minimizing data gaps.

Prioritize User-Centric Design: Ensure seamless user experiences through intuitive interfaces, efficient loading times, and high-resolution imagery. Incorporate accessibility features, such as captions, keyboard navigation, and multilingual support, to broaden audience reach and meet inclusive design standards.

Plan for Long-term Digital Preservation: Treat immersive documentation as part of heritage conservation, not just interpretation. Establish robust digital archiving protocols for 360-degree imagery and 3D models, aligned with international standards (e.g., UNESCO, CyArk), to secure assets for future restoration, education, and research.

Ethical Considerations: While the focus of this study is on technical and interpretive outcomes, it is important to acknowledge ethical concerns when using third-party platforms such as Google Street View. Hosting heritage content on commercial services raises questions of data ownership, long-term access, and privacy, particularly where individuals may be inadvertently captured. The ethics of digital reproduction also demand care to ensure cultural narratives are represented authentically and respectfully. While these issues did not present major concerns in the present study, acknowledging them is critical for guiding sustainable and responsible digital heritage practices.

Build Scalable and Standardized Systems: For complex or media-rich projects, invest in scalable infrastructure such as dedicated or cloud-based hosting. At the same time, adopt modular and standardized workflows for image capture, annotation, content integration, and testing. Where appropriate, apply AI tools for automating metadata creation, content tagging, or image enhancement. These practices ensure reliability, efficiency, and long-term scalability while reducing dependence on highly specialized expertise.

Enhance Spatial Accuracy and Storytelling: Leverage GPS and spatial metadata to strengthen realism, enable geolocated storytelling, and support future integration with mapping or AR platforms. Accurate geotagging is particularly important for outdoor sites, ensuring precise placement of content and opening opportunities for layered digital experiences. AI-powered geospatial analysis and automated 3D reconstruction can further improve accuracy and enrich interpretive storytelling.

Collaborate, Evaluate, and Evolve: Foster multidisciplinary collaboration among heritage interpreters, digital media specialists, spatial technologists, AI researchers, and user experience designers. Partnerships with local stakeholders and academic institutions can bridge skill gaps and sustain innovation. At the same time, implement robust feedback mechanisms and analytics including AI-driven visitor behaviour analysis to monitor engagement, identify technical issues, and guide iterative improvements. These measures will help ensure digital heritage projects remain relevant, accessible, and adaptable over time.

In summary, immersive technologies when thoughtfully deployed, hold considerable promise for transforming heritage interpretation and outreach. However, maximizing their impact requires balancing technical innovation with resource realities, prioritizing user needs, and grounding design in long-term sustainability and cultural authenticity. Future projects should adopt a holistic, flexible approach that integrates ethical awareness, long-term digital preservation, and scalable infrastructure. The strategic use of AI, robust geolocation, and user feedback can further enhance engagement and sustainability. By combining these elements, digital heritage initiatives can remain relevant, accessible, and adaptable to evolving technologies and audience expectations.

7. Conclusions

This study set out to investigate how 360-degree panoramic tours implemented through platforms such as 3DVista and Google Street View can enhance the promotion, accessibility, and visitor engagement of heritage sites. Through the comparative analysis of the Understory Art and Nature Trail and the Subiaco Hotel, the research demonstrated that immersive digital experiences can substantially broaden access to heritage, making both remote and built environments more visible and engaging to diverse audiences.

The findings indicate that Google Street View, when used for the Understory Art and Nature Trail, enabled broad public access and interactive exploration of outdoor art in a natural context, effectively overcoming geographic barriers and attracting a wide online audience. In contrast, the Subiaco Hotel’s 3DVista tour highlighted the potential of richly layered multimedia narratives integrating historical images, architectural drawings, and audio to deepen engagement and foster a nuanced understanding of built heritage among more targeted visitor groups.

The study also identified important challenges, including technical constraints in image capture and geolocation, the need for specialized skills and infrastructure, and the ongoing imperative to maintain historical authenticity in digital interpretation. Addressing these challenges is essential to fully realize the benefits of immersive technologies for heritage promotion and education. Additionally, interpreting the outcomes through TAM clarifies how usefulness and ease of use drive the acceptance of immersive heritage platforms. This theoretical lens strengthens the study’s applied findings and extends TAM into the field of digital heritage, highlighting how platform design mediates adoption.

For practice, the research suggests that heritage practitioners must align platform choice with audience needs. Google Street View demonstrates the value of ease of use and global reach, while 3DVista shows how rich multimedia can support specialist interpretation, though with higher technical demands. Theoretically, the findings show how TAM’s constructs of perceived usefulness and ease of use explain patterns of adoption in heritage contexts. This contributes to ongoing discussions in digital heritage scholarship by bridging applied outcomes with established theoretical perspectives.

This study also addresses several gaps noted in the literature, including comparative evaluation of immersive platforms and the integration of visitor feedback into heritage interpretation research. At the same time, broader issues remain. The long-term sustainability of digital engagement and the inclusivity of diverse demographic groups are still open challenges. Future work should investigate these through longitudinal and cross-cultural studies. The integration of AI for automated content tagging, adaptive interfaces, and visitor behaviour analysis present significant potential to advance both theoretical understanding and practical application.

Ultimately, this research affirms that 360-degree panoramic tours, when thoughtfully adapted to the characteristics and audiences of specific heritage sites, serve as powerful tools for enhancing visibility, accessibility, and educational value. Heritage practitioners are encouraged to leverage these technologies strategically, with careful attention to workflow optimization, audience diversity, and long-term digital preservation.

Author Contributions

H.R.: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—original draft; D.A.M.: Conceptualisation, Investigation, Supervision, Writing—review and editing, Funding acquisition; T.K.: Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review and editing; E.C.: Conceptualisation, Funding acquisition, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Australian Research Council, grant number LE210100021.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted with the support of Curtin University and Southern Forest Arts. We would like to thank the Subiaco Hotel management for access to the hotel, and to Curtin University Library for access to the digital collection of Summerhayes Architecture. We would also like to thank Fiona Sinclair, Artistic Director, Southern Forest Arts for her generous support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zeng, Y.; Liu, L.; Xu, R. The Effects of a Virtual Reality Tourism Experience on Tourist’s Cultural Dissemination Behavior. Tour. Hosp. 2022, 3, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keep, T.J.; Robinson, M.G.P.; Shoobert, J.; Birkett-Rees, J. An Australian Overview: The Creation and Use of 3D Models in Australian Universities. J. Comput. Appl. Archaeol. 2025, 8, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Muñoz, Ó. Analysis of Digitized 3D Models Published by Archaeological Museums. Heritage 2023, 6, 3885–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statham, N. Scientific rigour of online platforms for 3D visualization of heritage. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2019, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storeide, M.S.B.; George, S.; Sole, A.; Hardeberg, J.Y. Standardization of digitized heritage: A review of implementations of 3D in cultural heritage. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehade, M.; Stylianou-Lambert, T. Virtual reality in museums: Exploring the experiences of museum professionals. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lai, I.K.W. How A 360° virtual tour is more effective than photographs on communication effects: The roles of mental imagery processing and a sense of presence. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 26, 3813–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingstone, H. Contemporary History in Panoramas. In Panoramas and Compilations in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Seeing the Big Picture; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 27–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkady, D.; Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Virtual reality as a travel substitution tool during COVID-19. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2021, Proceedings of the ENTER 2021 eTourism Conference, 19–22 January 2021; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 452–463. [Google Scholar]

- Tost, L.P.; Economou, M. Worth a Thousand Words? The Usefulness of Immersive Virtual Reality for Learning in Cultural Heritage Settings. Int. J. Archit. Comput. 2009, 7, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, M.K.; Champion, E.; McMeekin, D.A.; Rahaman, H. The Influence of Collaborative and Multi-Modal Mixed Reality: Cultural Learning in Virtual Heritage. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2021, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehade, M.; Stylianou-Lambert, T. Emerging Technologies and the Digital Transformation of Museums and Heritage Sites: First International Conference, RISE IMET 2021, Nicosia, Cyprus, 2–4 June 2021, Proceedings; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Boukerch, I.; Takarli, B.; Saidi, K.; Karich, M.; Meguenni, M. Development of panoramic virtual tours system based on low cost devices. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, 43, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafar, I.A.; Arif, Z.; Syefudin, S. Systematic Literature Review: Virtual Tour 360 Degree Panorama. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, E.; Hiriart, J. Assassin’s Creed in the Classroom: History’s Playground or a Stab in the Dark? De Gruyter Oldenbourg: Berlin, Germany, 2024; p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- Eiris, R.; Wen, J.; Gheisari, M. iVisit–Practicing problem-solving in 360-degree panoramic site visits led by virtual humans. Autom. Constr. 2021, 128, 103754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, H.; Champion, E.; McMeekin, D. Beyond Google Street View: Expanding Boundaries with Interactive 360-Panorama Heritage Tours. In Proceedings of the 2023 State Heritage Conference Our Shared Heritage: Culture and Continuum, Perth, Australia, 23–24 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Li, X.-Z.; Chen, C.-C. An acceptance model of digital education in intangible cultural heritage based on cultural awareness. Digit. Creat. 2023, 34, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Z.; Chen, C.-C.; Kang, X.; Kang, J. Research on Relevant Dimensions of Tourism Experience of Intangible Cultural Heritage Lantern Festival: Integrating Generic Learning Outcomes With the Technology Acceptance Model. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 943277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Sutunyarak, C. The Impact of Immersive Technology in Museums on Visitors’ Behavioral Intention. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, J.; Alshare, K.A.; Lane, P.L. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in technology acceptance models: A meta-analysis. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2022, 23, 717–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maté-González, M.Á.; Rodríguez-Hernández, J.; Sáez Blázquez, C.; Troitiño Torralba, L.; Sánchez-Aparicio, L.J.; Fernández Hernández, J.; Herrero Tejedor, T.R.; Fabián García, J.F.; Piras, M.; Díaz-Sánchez, C. Challenges and Possibilities of Archaeological Sites Virtual Tours: The Ulaca Oppidum (Central Spain) as a Case Study. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Said, O.; Aziz, H. Virtual tours a means to an end: An analysis of virtual tours’ role in tourism recovery post COVID-19. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 528–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, D. History of VR—Timeline of Events and Tech Development. Virtualspeech. 17 October 2024. Available online: https://virtualspeech.com/blog/history-of-vr (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Vayanou, M.; Katifori, A.; Chrysanthi, A.; Antoniou, A. Cultural Heritage and Social Experiences in the Times of COVID 19. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Advanced Visual Interfaces and Interactions in Cultural Heritage (AVI2CH), Genoa, Italy, 29 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mantell, O.; Torreggiani, A.; Walmsley, B.; Kidd, J.; McAvoy, E.N. The same people seeing more: Audiences’ engagement with culture during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Pandemic Culture; Gilmore, A., O’Brien, D., Walmsley, B., Eds.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2024; pp. 65–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, H.; Champion, E.; McMeekin, D. Outside Inn: Exploring the Heritage of a Historic Hotel through 360-Panoramas. Heritage 2023, 6, 4380–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).