Iconography in the Mural Paintings of the Santa Catalina Convent as a Symbolic Element in Cusco’s Viceroyal Architecture

Abstract

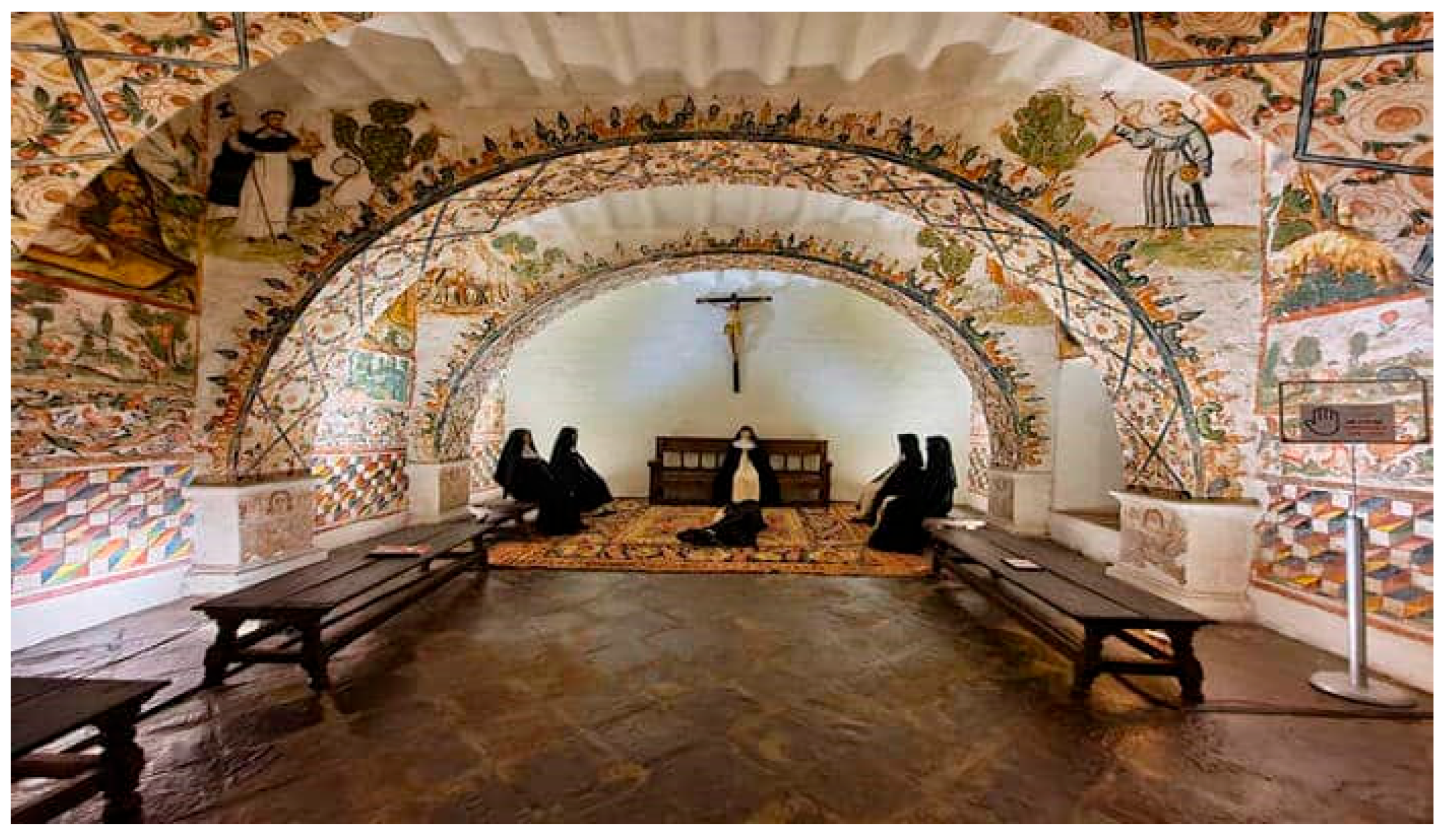

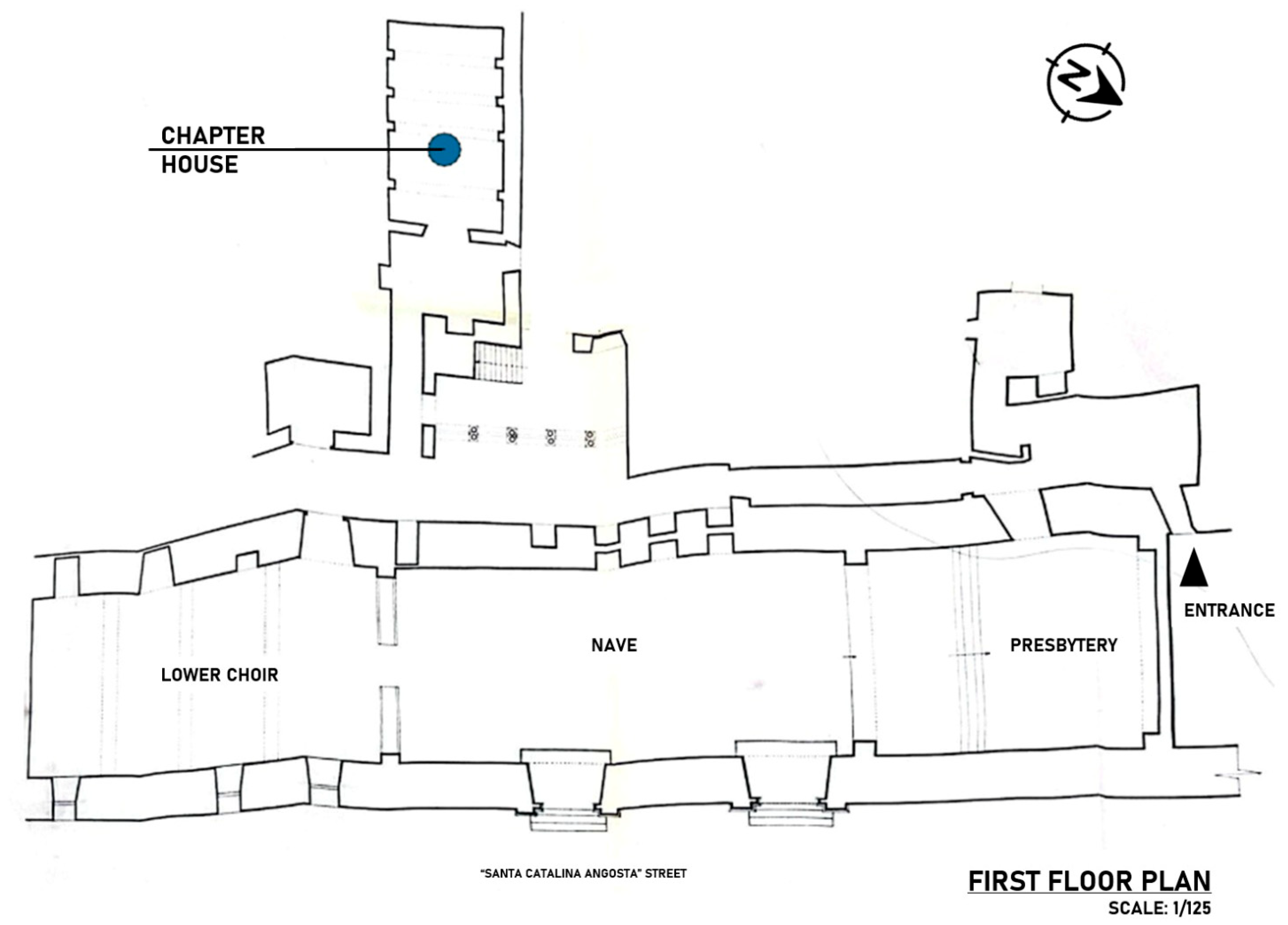

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Analysis Indicators

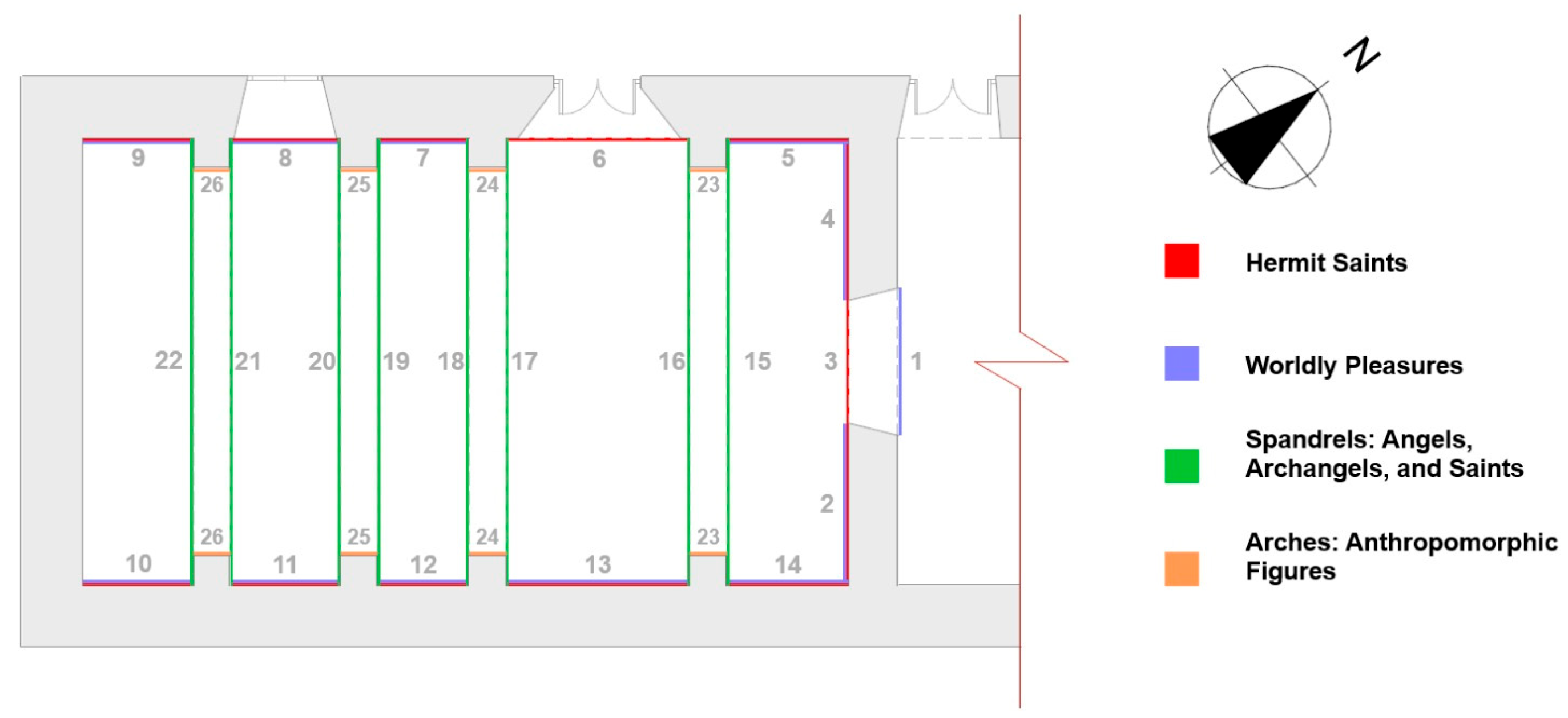

3. Results

3.1. Symbolic and Iconographic Interpretation of the Scenes

3.1.1. Mundane Scene of a Carriage Journey (See Figure 4)

- Methodological Approach of Erwin Panofsky: The mural painting titled “Carriage Ride” from the Monastery of Santa Catalina in Cusco allows, at its descriptive iconographic level, the identification of a profane scene of a customary nature composed of a caravan led by a rider dressed in a red jacket mounted on a white horse, followed by a closed carriage pulled by a pair of horses driven by a uniformed coachman. The interior of the vehicle reveals barely outlined female silhouettes, while on the lateral edges, characters wearing tricorn hats, lush vegetation, rural roads, and peripheral constructions can be observed; the entire composition is framed by an ornamental motif of polychrome scrolls that accentuates its decorative character. The technical treatment, characterized by linear strokes and earthy chromatics, corresponds to the popular pictorial styles of the 18th century.

- Iconological Analysis: The scene does not simply represent an excursion or a playful moment of the colonial aristocracy, but rather embodies a visual discourse on the vice-regal social order and its hierarchies. The carriage symbolizes elevated status and the separation between the privileged interior and the servile exterior, while the idyllic landscape suggests a domestication of nature in accordance with colonial authority. The ornamental frame of acanthus leaves and scrolls, more than just a decoration, functions as a symbolic boundary that separates the represented world from the conventual space, thus channeling a visual experience that naturalizes the hierarchical structure of the social body. The scene projects the Baroque ideal of order as a reflection of the divine cosmos, where each element has its assigned place according to a higher logic that legitimizes power and privilege.

- Classical Theological Approach: This image could be interpreted as a symbolic representation of the soul’s passage through the temporal world. In the Thomistic view, the carriage and its movement suggest the vital process ordered by divine providence, where each person, according to their state, fulfills a function established by God. The division between figures inside and outside the carriage alludes to the mystical body of the Church, where the visible hierarchy does not deny the spiritual equality of all the faithful but rather reflects the natural order inscribed in creation. From St. Augustine’s perspective [24], the scene could also evoke the soul’s pilgrimage through the earthly city toward the heavenly city. Meanwhile, for John Calvin [25], although distant from ornamental use, the narrative clarity and symbolic restraint of the image align with a moral pedagogy that avoids explicit sacredness while maintaining a visual didactic structure.

3.1.2. Scene of the Genealogical Tree of Dominican Saints (Left) and the Guzmán Family (Right), Center, Virgin of the Rosary with Saint Catherine and Saint Rose of Lima (See Figure 5)

- Methodological approach of Erwin Panofsky: The scene represents an allegorical composition centered on the Virgin of the Rosary, surrounded by two Dominican religious figures (Virgin of the Rosary with Saint Catherine) in a posture of supplication and by angels extending their protective mantle. On both sides, genealogical trees are arranged, with branches populated by busts of ecclesiastical and religious figures, identifiable as members of the Order of Preachers, dressed in the Dominican habit. At the bottom, scenes of gardens, archway architectures, and human figures engaged in festive and recreational activities can be seen, while in the upper left appears a representation of hell that contrasts with the beatific surroundings of the rest of the mural. The scene combines figurative, vegetal, and architectural elements within a hierarchical structure that organizes the reading from the earthly lower part to the celestial upper part.

- Iconological Analysis: This painting is presented as a symbolic representation of Marian protection over the Dominican spiritual family and, by extension, over the female convent for which this iconography was intended. The Virgin’s central position, with her mantle extended and crowned figure, alludes to her role as Queen of Heaven and mediator of graces, according to the rosarian tradition that was intensely promoted during the viceroyalty period. The trees with fruits and figures arranged in their branches refer to the spiritual and doctrinal lineage of the Order, reinforcing its historical and charismatic legitimacy. The contrast between the earthly paradise and the infernal scene at the bottom suggests an allegory of the eschatological judgment and salvation through belonging to a religious life governed by contemplation, obedience, and devotion to Mary, which is part of a Baroque catechetical program aimed at the emotional and moral instruction of the nuns and visitors.

- Classical Theological Approach: From the theological perspective founded on the Summa Theologica of Saint Thomas Aquinas [24], this scene visually expresses the notion of intercession and spiritual hierarchy in the economy of salvation. The Virgin, as co-redemptrix, acts according to Thomistic doctrine as a privileged instrument of mediation between God and humanity, and her extended mantle visualizes the divine grace dispensed through her intercession. The spiritual genealogy symbolized in the trees reflects the providential action of the Spirit in the history of the Church, while the harmonious order of the mural refers to the principle of formal reason that, for Aquinas, structures all creation according to the good. Saint Augustine, in his treatise De Trinitate, emphasizes the function of memory, understanding, and will as Trinitarian reflections in the human soul [26]. This mural articulates these principles through a symbolic language that invites the viewer to contemplate the Marian model as a path toward mystical union. From a Calvinist perspective, although the exaltation of Mary is theologically problematic, the clarity of symbolism, the use of ordered figures, and the iconographic subordination to a doctrinal discourse can be understood as a pedagogical expression compatible with a reading that prioritizes moral edification and the centrality of grace over human merit.

3.1.3. Scene of Saint Jerome the Penitent, a Feast in the Midst of a Garden, Floral Designs of Roses and Foliage, and Geometric Patterns (See Figure 6)

- Methodological approach of Erwin Panofsky: the mural scene identified in the Monastery of Saint Catherine represents an iconography composed of several narrative registers. At the top, a hermit is observed in a penitent attitude, possibly Saint Jerome, enclosed in a cave that symbolizes withdrawal from the world and spiritual ascension through asceticism; he holds a cross, a skull, and an open book, which reinforces his role as a scholar, penitent, and witness to the transition between temporal and eternal life. The red tunic envelops his body, symbolizing sacrifice, while around him a harmonious natural landscape is depicted, contrasting with his severe and meditative expression. In the lower registers, banquet scenes, gardens, and figures in playful or contemplative attitudes are observed, suggesting an alternation between worldly life and the call to conversion, arranged in horizontal sequences that favor the narrative reading of spiritual life.

- Iconological Analysis: This composition embodies the tension between the active life and the contemplative life, one of the fundamental dilemmas of colonial Christian thought. The image of the hermit saint serves as an allegory for the detachment necessary to attain wisdom and holiness, representing the monastic ideal that articulates the inner life as a path toward divine truth. The skull at his feet operates as a symbol of vanitas, a reminder of death, while the open book alludes to revealed knowledge and the need to integrate faith and reason in spiritual practice. In contrast, the lower scenes, with their courtly setting, ornamental fountains, and characters gathered around tables and gardens, create an atmosphere of sensory delight that the mural proposes to transcend through inner contemplation. The decorative framework of floral scrolls and optical geometry reinforces the intention to visually organize the transition from the material to the spiritual within the architectural space of the convent.

- Classical Theological Approach: The thought of Saint Thomas Aquinas allows us to interpret this scene as a visual expression of moral order and the hierarchy of knowledge. The asceticism of Saint Jerome aligns with Thomistic doctrine, which posits that the soul must govern the senses through virtue to direct its will toward God, the supreme principle of good. The cross held by the saint represents Christ’s redemptive act, while the idealized natural environment suggests that creation is a reflection of divine order. From an Augustinian perspective, the scene represents the memory of sin, the intelligence illuminated by grace, and the will oriented toward conversion—three dimensions of the soul that Saint Augustine identifies as an image of the Trinity. For John Calvin, although extreme asceticism was less valued, the silent contemplation of the Word through Scripture is compatible with the attitude of the holy hermit, as long as the image does not usurp the place of the Word.

3.1.4. Scene of the Conversion of Saint Paul (See Figure 7)

- Methodological Approach of Erwin Panofsky: The scene represents an intense military confrontation that can be interpreted on two complementary levels. From a descriptive iconography perspective, armed male figures with spears, swords, and shields are identified, mounted on steeds in a combat stance, while they fall defeated to the ground with expressions of anguish. The arrangement of the bodies and the fall of the warriors reinforce the idea of a violent defeat; in the background, in the celestial space and in stark contrast to the earthly scene, the figure of an angelic being is manifested, suspended in the clouds. Its elevated position and benevolent gesture suggest a transcendental authority; this celestial character, adorned in flowing garments and with a contemplative attitude, indicates the presence of the divine as a guiding element in the human conflict, establishing a vertical axis between the spiritual and the material planes. The color palette, dominated by ochre, reddish, and white tones, helps to emphasize the drama of the scene while reinforcing the separation between the sacred and the profane.

- Iconological Analysis: The combat does not merely represent a historical or allegorical scene but is projected as a symbol of the struggle between good and evil in the theological and political context of the Andean viceroyalty. The downfall of the warriors, likely Moors or heretical figures, suggests the defeat of error in the face of Christian truth. This visual discourse aligns with the evangelizing and disciplining project of the Catholic Church in colonial territories, where mural painting served as visual catechesis for a predominantly indigenous and illiterate population. In this sense, the representation of the angel not only mediates between the two worlds but also acts as a manifestation of divine judgment that legitimizes the victory of the Catholic faith. The scene, therefore, conveys a worldview in which the supernatural regulates human history in accordance with the providentialist vision that permeated Cusco’s viceroyal art.

- Classical Theological Approach: In light of the fundamental theological sources of the Christian tradition, the image can be interpreted from a deeper doctrinal framework. According to the Summa Theologica by Saint Thomas Aquinas, the supreme good is linked to the rational order imposed by God upon creation, thus the downfall of the enemies represents the restoration of divine order in the face of the corruption of sin; this scene also engages with the Augustinian ideas presented in De Trinitate, where it is argued that the true battle is internal and spiritual, with external enemies serving as an allegory for the soul’s struggle against passions. In this sense, the mural iconography becomes a dramatization of the inner purification necessary to attain grace; on the other hand, the work of John Calvin, Institutiones Christianae Religionis, although not influential in the Cusco Catholic context, offers a valuable contrast by insisting on the absolute sovereignty of God in human salvation, an element also visible in the figure of the angel as the executor of divine will.

3.1.5. Scene of Saint Paul the Hermit, Hunting Scene, Floral Designs of Roses and Foliage, and Geometric Patterns (See Figure 8)

- Methodological approach of Erwin Panofsky: The scene presents a vertical narrative structure that articulates different levels of meaning, which should be analyzed through a dual iconographic approach. In the upper plane, a hermit is distinguished, kneeling in a posture of prayer, likely Saint Jerome, within a cave framed by a rugged landscape and lush trees. The figure holds a crucifix while contemplating an open book that hangs from a branch next to a stone, attributes linked to penance and ascetic retreat; the presence of a raven descending with food refers to the hagiographic passage of the saint being miraculously fed in the desert. The middle scene represents a bucolic landscape in which a peasant guides a yoke of oxen in front of a colonial building, while trees and birds surround the environment. The lower level contains ornamental decoration of floral garlands, followed by a geometric pattern in perspective, composed of polychromatic cubes that simulate a three-dimensional effect.

- Iconological Analysis: Based on medieval and patristic theological sources, the mural acquires a deeper dimension that transcends the narrative. According to Saint Thomas Aquinas, knowledge and contemplative life constitute the highest form of union with God; thus, the figure of the hermit embodies the perfection of the intellect illuminated by grace. The open book and the crucifix refer to the dual source of theological knowledge: written revelation and redemptive incarnation, elements that enable the attainment of divine truth. In line with Saint Augustine, the cave symbolizes the soul’s retreat inward, where the true encounter with the Trinity occurs. The raven that brings food is presented as an allegory of divine providence, acting in history to sustain the just on their path of purification. The middle band, with its representation of agricultural life, can be linked to the doctrine of man’s natural vocation as a cooperator in creation, which is also reaffirmed by Calvin in his exaltation of work as a sign of obedience to God.

- Classical Theological Approach: The geometric pattern that encloses the composition should not be read as a mere ornament, but rather as a visual formulation of order and proportion, principles that in Christian theology refer to the divine rationality imprinted in creation. This visual regularity can be interpreted in light of the Augustinian notion that all earthly beauty is a reflection of trinitarian harmony. In this sense, the painting becomes a microcosm where the aesthetic, ethical, and mystical converge. The mural scene, therefore, offers not only an instructive representation of ascetic life but also a comprehensive visual model of the economy of salvation, intended to educate the soul on its journey from the temporal to the eternal.

3.1.6. Scene of Saint Mary of Egypt and Saint Francis of Paula (See Figure 9)

- Methodological approach of Erwin Panofsky: This image is broken down into two complementary levels. On the iconographic plane, the identification of the elements allows us to link the scene with known hagiographic episodes from Christian tradition, particularly with the Golden Legend and its dissemination in the Andean viceroyalty context; Mary of Egypt, depicted in her penitent form, was one of the most widely represented female models in colonial religious art, associated with conversion and the redemptive power of grace. The hermit, by offering her the chalice, visually updates the sacrament of the Eucharist as a channel of salvation.

- Iconological Analysis: This scene expresses a pedagogy of repentance and individual redemption, key in the Counter-Reformation spirituality that underpinned the architecture and viceroyal art of Cusco. The mural proposes a visual narrative that articulates the ideal of soul purification through withdrawal, bodily pain, and sacramental mediation; in the political and cultural context of the time, this representation also served as a visual catechetical tool for the women confined in the monastery, reaffirming the model of Mary of Egypt as a paradigm of spiritual transformation through obedience and penance.

- Classical Theological Approach: The image can be understood as an allegory of the soul redeemed by grace. For Aquinas, the reception of the sacraments in a state of sincere contrition produces a real effect on the soul, which is represented here by the receptive gesture of the penitent before the chalice. The scene thus symbolizes the transition from guilt to forgiveness, a process that depends not only on external acts but also on an internal disposition oriented towards the divine good. In Augustinian theology, the retreat to the desert serves as a metaphor for the inner journey, in which the soul, torn by sin, encounters the mercy of God in the solitude of the heart. The dark background of the cave and the brightness of the natural surroundings can be interpreted as a symbolic opposition between overcome sin and the new life of grace. Calvin, with his emphasis on the centrality of faith and the life-giving power of the Spirit, would have viewed this image as a representation of God’s regenerating work in the life of the believer, transcending mere bodily works, although the Catholic context of the mural does not reflect his rejection of sacramental intermediaries. The painting thus synthesizes a mystical vision of the human soul in its process of conversion, where repentance and contact with the sacred (through the Eucharist and contemplative isolation) restore the fallen being’s original dignity.

3.1.7. Scene of the Holy Hermit, a Scene of a Stroll in an Orchard of Fruit Trees, a Water Fountain, and Four Characters, Floral Designs of Roses and Foliage, and Geometric Patterns (See Figure 10)

- In the scene, a compositional structure is clearly distinguished, divided into four registers that articulate a visual program of devotional and doctrinal content. The upper section depicts a bearded man, possibly Saint Jerome or an anonymous hermit, in a contemplative pose before three open books, framed by a natural grotto and architectural elements in the background. This image, from a descriptive iconography perspective, refers to the ideal of an ascetic life centered on theological meditation, where the books represent the Sacred Scriptures or fundamental patristic texts. Through iconological analysis, the scene is linked to the Counter-Reformation’s valuation of study as a means of salvation, integrating the landscape as a symbol of spiritual retreat and divine revelation.

- The second register introduces a central fountain surrounded by human figures in a leisurely or conversational posture, within an ornamented garden featuring fruit trees, flowers, and winding paths. This representation creates a locus amoenus that alludes to the lost Paradise and, in a Christological key, to the restoration of grace through baptism. According to the Summa Theologica, the fountain is identified with the flow of divine grace that cleanses and revitalizes the soul, while for Saint Augustine, the emanation from a single point into multiple streams refers to the consubstantial Trinity. The coexistence of figures without hierarchical or narrative distinction highlights the universal value of redemption and the unity of the mystical body of Christ as a renewed spiritual community.

- At the bottom, the floral and geometric ornamental bands do not merely serve as decorative divisions; instead, they form a symbolic system that reinforces the theological message of the upper registers. The vegetal frieze alludes to the fertility of the regenerated soul and the beauty of the divine order manifested in creation, while the perspective cube pattern represents the stability of faith and the celestial architecture of theological knowledge. In light of De Trinitate, this mathematical structure becomes a metaphor for the trinitarian order, where visual harmony reveals divine intelligence in visible form. The entire composition unfolds a spiritual narrative that integrates doctrine, contemplation, and visual pedagogy within the cultural context of the Andean viceroyalty.

3.1.8. Scene of San Pedro de Alcántara, Geometric Patterns, Worldly Scene, Ornamental Motifs and Decorative Elements (See Figure 11)

- A monk is depicted kneeling at the doors of a wooden cell, in a posture of prayer, accompanied by an open book where the inscription “Soli tibi Domine” is clearly visible. Through Panofsky’s iconographic approach, this image corresponds to an eremitic figure (likely Saint Francis of Assisi or Saint Anthony the Abbot) set in a carefully structured natural environment that includes fruit trees, birds, and a crucifix planted next to a prayer book. From the descriptive iconography, there is an intention to reinforce the model of a life dedicated to contemplation and penance, while from the iconology, a visual narrative emerges centered on renunciation of the world and the pursuit of inner solitude, a central idea in the counter-reformist discourse promoted in Andean conventual spaces.

- In the second register, the visual program shifts to a garden of cultivated trees where children or adolescents gather fruit under the watchful eye of female figures, one of whom appears to direct the scene. To the left, a classical facade is depicted, suggesting the entrance to a hortus conclusus or closed garden, a space that in patristic tradition symbolizes both the soul and the virginal womb of Mary. In Thomistic terms, this cultivated garden represents the soul in a state of grace where will and reason work in harmony with faith to bear virtuous works. Saint Augustine would interpret the act of harvesting as a metaphor for the acquisition of divine knowledge that matures over time through the illumination of the Spirit, while from a Calvinist perspective, it serves as a representation of divine providence guiding man towards the fulfillment of his earthly vocation.

- In the lower ornamental registers, the visual language used in the other mural panels is maintained: a vegetal strip of intertwined flowers, followed by an acanthus border in reddish tones, and finally a geometric pattern of intertwined cubes that simulate depth. This structural base serves a dual function: on one hand, it reinforces the aesthetic unity of the whole, and on the other, it provides a symbolic reading anchored in the theology of the Trinity, where the intertwined forms refer to the interrelation of the three divine persons. The compositional rigor of the geometric pattern can also be interpreted as a reflection of the rational order of the created universe, a statement that aligns with the Thomistic view of the cosmos as an intelligible manifestation of the Creator. Thus, the mural articulates a symbolic system that connects personal mystical experience with the collective dimension of spiritual life, expressed through symbols that are legible both to the monastic community and to the educated New Hispanic public familiar with visual catechesis.

3.1.9. Scene of Saint Hermit, Worldly Scene and Ornamental Motifs (See Figure 12)

- The scene presents a composition structured around the figure of a standing Franciscan monk, likely Saint Francis of Assisi, holding two open books before the vision of another kneeling friar in front of an altar set within a rustic chapel. Through the panofskian lens, the upper register reveals a clear articulation between devotional iconography and the exaltation of the eremitic ideal, symbolized in the natural surroundings filled with vegetation, wildflowers, and birds, as well as in the arrangement of the altar oriented toward an intimate interior. The gesture of the saint in a teaching posture and the presence of books reinforce the doctrinal dimension of the image, suggesting a spiritual transmission that goes beyond the verbal toward a direct experience of the divine, as was promoted in the reformed spirituality of the 17th and 18th centuries in the monastic spaces of the Viceroyalty of Peru.

- In the second register, a pastoral scene unfolds, depicting two young people engaged in play, pursued by a female figure holding an instrument in her hand. The space is enclosed by a vegetal architecture reminiscent of the labyrinths found in convent gardens, suggesting a symbolic order laden with moral significance. From a Thomistic perspective, this space can be understood as an image of the created world where the human soul, even in a state of innocence, navigates between sensory delight and the ethical vigilance that Christian pedagogy deems necessary to avoid falling. From an Augustinian viewpoint, the scene presents an allegory of the fluctuating will of man, who seeks the good but often becomes distracted by the trivial, needing to be redirected by grace towards the path of inner recollection and contemplation of the eternal.

- The lower decorative registers reinforce the theological narrative through a series of visual codes. The vegetal strip that includes intertwined acanthus, fruits, and birds evokes spiritual fertility and the abundance promised to the soul that remains on the path of the Lord. Meanwhile, the lower geometric pattern, formed by interwoven cubes of multiple colors, suggests a structure of trinitarian order. Symbolically, the impossible geometry alludes to the mystery of the coexistence of unity and plurality in God, and can be understood, in light of Augustine’s De Trinitate, as a material reflection of the internal dynamism of the Trinity acting in the visible world.

3.1.10. Scene of Saint Mary Magdalene Penitent, Worldly Scene and Ornamental Motifs (See Figure 13)

- The scene presents a sequence of overlapping registers that begins with the image of a female figure identifiable as Mary Magdalene, recognized by her long hair, her penitential attitude, and the presence of traditional iconographic attributes such as the skull, the open book, and the hair shirt. Her location within a cave refers to the theme of eremitic retreat and meditation on death, while the background landscape with castles and paths introduces a contrast between contemplative life and the outside world. In the intermediate register, a pastoral scene is observed that, although seemingly bucolic, contains elements that invite allegorical interpretation, such as dance and hunting, classic symbols of worldly distraction and sin, thus articulating a visual narrative that flows from penitence to the temptations of the sensible world.

- From the Panofskian iconological perspective, the mural sequence suggests a pedagogical intention consistent with the evangelizing mission of the viceroyal monastic environment. The representation of Mary Magdalene not only refers to her model of redemption but also positions her as a paradigm of spiritual transformation, embodying the ideal of conversion proposed to women within the colonial Christian social order. The intermediate scene with its dancing figures and hunters is inscribed within the moralizing tradition of Christian painting, where nature and the body function as battlegrounds between the soul and the senses. The lower geometric design, with its illusion of depth and order, can be understood as an allusion to the divinely structured cosmos, establishing a visual connection between the disorder of sin and divine harmony.

- From a theological perspective, the mural establishes an allegorical reading of the economy of salvation articulated through mystical experience. The figure of Mary Magdalene, whose conversion has been profoundly elaborated by Augustine of Hippo in his reflections on grace, symbolizes the transformative action of divine love in the fallen human soul. The contrast between the scene of retreat and pastoral mundanity can be linked to the doctrine of the redeemed will according to Thomas Aquinas, where the choice of good requires an active detachment from passions. The geometric foundation of the mural can be interpreted as a Trinitarian image in a Calvinist key, where clarity, structure, and rationality represent the divine order established by the Logos, anticipating the restoration of the soul through the knowledge of God revealed in Christ.

3.1.11. Scene of Saint Onuphrius, Secular Scene, Ornamental Motifs (See Figure 14)

- From the methodological approach of Erwin Panofsky, the mural scene located in the Monastery of Santa Catalina presents, at its descriptive iconographic level, the figure of Saint Onuphrius in the upper register, depicted as an ascetic with a naked body covered only by foliage, with a long beard, emaciated face, and a praying posture before a cave. Beside him rest a staff and an open book, symbols of sacred knowledge and his condition as a penitent hermit. In the intermediate register, a secular scene is observed showing a group of musicians with instruments, alongside a figure reclining on a covered table, possibly asleep or deceased, in a wooded setting that suggests a festive or ambiguously funerary space. These elements are framed by bands of floral ornamentation and a lower frieze of illusionistic geometry that simulates architectural depth, thus completing a pictorial program that articulates hagiographic narrative, scenes of secular life, and symbolic decoration.

- On the iconological level, the image of Saint Onuphrius alludes to the absolute renunciation of the world, to the hermitic life as a path to union with God, and to the abandonment of the body as a means of spiritual elevation. His figure embodies the ideal of the desert as a space of purification, where the soul confronts the void of the created to contemplate the Creator. In contrast, the worldly scene that accompanies him introduces a moral critique of vanity and excess, showcasing a musical banquet that becomes an image of dissipation and the forgetfulness of death, emphasized by the presence of the reclining figure. This tension between spiritual retreat and worldly life is inscribed within the Baroque discourse that dramatizes the conflict between body and soul, between the eternal and the ephemeral. The ornamental motifs reinforce this symbolic structure by representing the sensory beauty that can elevate or distract, depending on the inner order of the soul, thus shaping a visual discourse of warning and meditation.

- From a theological perspective, the thought of Saint Thomas Aquinas considers that the soul attains the beatific vision through contemplation and the exercise of virtue, which is reflected in the figure of Saint Onuphrius as a symbol of holiness acquired through asceticism and grace. His stance and the attributes surrounding him manifest a state of total abandonment to God, in accordance with Thomistic doctrine on the subordination of the senses to reason illuminated by faith. For his part, Saint Augustine interprets this type of representation as an expression of the soul that, stripped of all earthly distractions, recognizes itself as finite and surrenders to the memory of God. In contrast, the mundane scene can be understood as an image of the soul distracted by fleeting pleasures, which ignores the urgency of conversion. For John Calvin, while he rejects the veneration of images, he would admit that these representations serve a didactic function when subordinated to the Word, and in this case, the visual duality offers the viewer a moral reflection on the fate of the soul. Therefore, the mural as a whole not only articulates aesthetic resources but also constructs a symbolic architecture of salvation aimed at moving and teaching through the image.

3.1.12. Scene of Saint Anthony of Abbot, Worldly Scene and Ornamental Motifs (See Figure 15)

- The scene depicts a hermit saint, easily identifiable as Saint Anthony Abbot, who is shown seated in front of a cave, wrapped in a dark cloak with an open book on his lap, in a posture of contemplative reading. He is accompanied by a tau cross and a staff, unmistakable symbols of his monastic identity, while a raven brings him food and a boar present itself gently at his feet, alluding to medieval hagiographical accounts. In the distance, buildings and a vegetative environment create a space for retreat, contrasting with the dynamism of the lower scene, where a hunt is depicted with armed horsemen chasing animals in a forest. Below this narrative scene, a decorative vegetal frieze and a multicolored geometric pattern unfold, harmoniously and visually structuring the composition.

- From the Panofskian perspective, the scene articulates a narrative of ascetic life contrasted with the frenzy of worldly existence. The image of Saint Anthony the Abbot in his retreat refers to the pedagogical function of monasticism as a model of stability, obedience, and inner conversion, promoted in the Virreinal visual discourse as an ideal for women’s religious life. The contrast with the hunting scene suggests an allegory of spiritual struggle, in which the senses, represented by the horsemen, chase after the beast, while the saint, in his stillness, embodies the victory of the spirit over the flesh. The ornamental frieze and geometric design reinforce the symbolic dimension of the divine order that underlies the entire narrative structure of the mural, integrating the levels of contemplation, action, and cosmological harmony.

- From a theological perspective, the representation of Saint Anthony is linked to the Augustinian doctrine of the soul, which, only in solitude, is prepared to hear the voice of God, away from the sensory distractions of the external world. The reading of the book refers to the meditation of the Scriptures as spiritual nourishment, corresponding with the raven that delivers bread, a sign of divine providence according to Thomas Aquinas. The domesticated wild boar alludes to the redemption of the wild through grace, illustrating the possibility of transforming sin into virtue. The hunting scene, understood from a Calvinist viewpoint, represents humanity’s persistent fall into error without the intervention of grace, reaffirming the need for withdrawal and purification to attain the beatific vision, symbolically reflected in the geometric harmony that crowns the entirety of the visual program.

3.1.13. Scene of the Trumpeting Angel (Left and Right) and Ornamental Motifs Zoomed in (See Figure 16)

- The scene depicts a winged angel in motion playing a trumpet while holding a floating band that waves with strong symbolic significance. Its figure is dressed in a short tunic, tied at the waist with a cord, which emphasizes its dynamic and messenger character. The outspread wings, the elevated gesture of the arm, and the forward position of its legs suggest an urgent call, framed by ornamental scrolls that visually connect this image with the rest of the mural program of the monastery. The trumpet, a recurring visual element in colonial sacred art, refers to the eschatological announcement and divine judgment, integrating this celestial character into the rhetoric of the apocalyptic and redemptive.

- From Panofsky’s iconographic perspective, the trumpeting angel can be read as a symbol of divine revelation, articulating the moment of the final call that precedes the manifestation of eternal truth. Its bodily disposition conveys a theatricality that responds to the visual language of Andean Baroque, where movement dramatizes the celestial message. This type of figure is formally linked to representations of the Apocalypse and the Last Judgment, indicating not only a prophetic end but also an act of proclaiming divine glory. Within the viceregal framework of Cusco, its presence inside a monastic space like Santa Catalina also serves an educational function, reminding the nuns of the constant call to spiritual vigilance.

- The theological reading allows us to understand the trumpet as an instrument of the divine logos, for Augustine of Hippo, the Word is manifested in audible signs that awaken the soul from earthly slumber. Thomas Aquinas reaffirms this function of angels as ministers of Providence, executors of divine will in history, which gives meaning to the active role of the angel as a herald of judgment. For Calvin, the image also refers to the moment when the Lord will separate the righteous from the wicked, sounding His voice like a trumpet through His heavenly servants. The angel depicted in the mural is not merely a visual ornament, but a visual echo of the Apocalypse, a trinitarian symbol of fulfilled time and the urgency of inner conversion that structures the entire monastic theology of contemplative life.

3.1.14. Scene of Saint Michael the Archangel, Archangel Gabriel, Ornamental Motifs (See Figure 17)

- The representation of the Virgin of the Rosary in the mural cycle articulates a devotional discourse that reflects her role as a mediator and intercessor before Christ. This function, in the Dominican context, is closely linked to the defense of faith and the spiritual victory over evil. Her iconography (composed of the rosary, the crown, and the central placement in the mural program) reinforces her status as the protector of the monastic community, thereby integrating doctrinal and emotional aspects into a single visual resource of great persuasive effectiveness.

- In light of the systematic theology of Aquinas, Calvin, and Augustine, this scene condenses a trinitarian vision of salvation: the archangel’s battle reflects the action of the Word against sin, the Virgin’s intercession represents the mediation of grace and the prayer of the soul, while the human couple refers to the fallen nature that longs for its redemption. Augustine would have seen in the shield of Saint Michael a manifestation of God’s ordered love, which does not allow evil to prevail in history, while Aquinas re-evaluates the role of angels as instruments of divine justice. For Calvin, the presence of the Virgin does not contradict the centrality of Christ, but can be interpreted as a figure of the Church, adorned with virtue, that accompanies the believer in their spiritual pilgrimage toward the heavenly city.

3.1.15. Scene of the Guardian Angel, Archangel Saint Raphael, and Ornamental Motifs (See Figure 18)

- The scene depicts, at the ends of an arch, two angels dressed in ornate robes, from whose mouths and hands emanate gestures of proclamation and announcement. Both are framed by fruit trees with lush foliage and birds in flight, elements that, from the descriptive iconography of Panofsky, refer to a symbolically Edenic and spiritual space. The angel on the left appears to point at the viewer with a gesture of authority, while the angel on the right holds an unfurled ribbon, suggesting a divine message or proclamation. The symmetry of the scene and the decorative vegetal style reinforce the idea of a cosmos ordered according to celestial principles.

- From an iconological perspective, this representation acquires a profound meaning by placing the angels as heralds of a sacred truth in a space that combines the ornamental with the liturgical. The use of lush foliage and curvilinear forms expresses a Baroque vision of paradise as an ideal of spiritual beauty and divine harmony. In the context of the Cusco viceroyalty, the function of the angels transcends the decorative and communicates the evangelizing message that is inscribed in the architecture of the convent as a permanent reminder of the presence of the divine in the everyday. The fact that they are positioned above a passageway underscores their role as guardians of a threshold between the earthly world and the sacred realm. The prominence of color ranges Y–Y50R and their correspondence with Andean theological and cultural meanings fulfills objective (ii) by linking color choices with the symbolic construction of the message.

- In light of the theological treatises of Thomas Aquinas, Calvin, and Augustine, angels can be interpreted as personifications of God’s action in the world, manifestations of His providence, and agents of His Word. According to Aquinas, angels fulfill intellectual and executive functions within the divine order, which is reflected here in their communicative attitude and their integration with the natural environment. Augustine would understand them as pure intelligences in constant praise of the Trinity, and their placement in a high realm reinforces this theological interpretation. For Calvin, the message of the angels must focus on the authority of the Scriptures and the sovereignty of God, elements suggested by the gesture of proclamation that points toward a revealed truth that transcends the visible.

3.1.16. Scene of the Trumpeting Angel (Left and Right) and Ornamental Motifs (See Figure 19)

- The scene depicts two angels playing trumpets, symmetrically positioned over an arch adorned with botanical motifs in Andean Baroque style. Each figure is shown in an upward movement, with wings spread and tunics fitted to the body, suggesting dynamism and solemnity. From the descriptive iconography, the trumpet is a symbol of celestial announcement and divine judgment, an instrument associated with the apocalyptic passages of the New Testament, particularly the Book of Revelation, where the angels announce the end of times and the fulfillment of the Kingdom of God. The serene faces, firm postures, and elevated positioning reinforce their status as divine messengers.

- By applying an iconological analysis using Panofsky’s methodology, this image is embedded within a visual discourse of warning and revelation that articulates the mystical with the pedagogical. In the context of the colonial Cusco, the trumpeting angels not only refer to the Last Judgment but also serve as visible doctrinal elements for a predominantly Indigenous and mestizo audience, inviting reflection on the salvation of the soul and the imminence of Christ’s second coming. The symmetry and visual language employed in the clothing and gestures create an aesthetic that blends European and local elements, reinforcing the evangelizing role of conventual mural art.

- From the scholastic and reformed theology, the use of the trumpet as an instrument of revelation can be interpreted as an allusion to the active Word of God that breaks into history to restore spiritual order. According to Thomas Aquinas, angels, as purely intellectual beings, act under divine will and communicate eternal judgment without deviation, while for Calvin, these celestial heralds reinforce God’s sovereignty over human destiny without the need for earthly mediation. In Augustine’s view, the sound of the trumpet is an echo of eternity that calls the elect to the bosom of the Trinity, alluding to the final communion between the divine and the created.

3.1.17. Scene of Saint Francis of Assisi, Saint Dominic de Guzmán, and Ornamental Motifs (See Figure 20)

- The scene features the figure of a Franciscan saint, iconographically identified as Saint Francis of Assisi, who holds a cross in his right hand and a skull in his left, while a lush tree with birds perched around it rises behind him. From a descriptive perspective, the gray habit typical of the order, the halo of holiness, and the presence of wings stand out, symbolically linking him to the angelic world or to an exalted representation of his spirituality. The skull directly alludes to memento mori, while the tree refers to contemplative life and the restored paradise, elements that merge the message of penance with hope in resurrection.

- The iconological analysis, according to Panofsky’s method, reveals an articulation between Counter-Reformation aesthetics and Franciscan spirituality that permeates Andean viceroyal art. The inclusion of Saint Francis on the walls of the monastery responds to the need to make visible accessible and profoundly human models of holiness for local communities, promoting the imitation of his life of humility, renunciation, and charity. The tree laden with birds also alludes to his famous sermon to the creatures, with a clear intention to highlight his communion with creation, a trait that was intensely valued in the Andean context for its resonance with pre-existing indigenous worldviews, thus favoring a process of visual and doctrinal syncretism. This finding satisfies objective (iii) by allowing a reading that combines European references and local resignifications.

- From a theological perspective, Saint Francis embodies the living manifestation of the imitatio Christi, whose understanding, according to Thomas Aquinas, lies in the total subordination of the human will to the divine order. The cross represents active redemption and voluntary suffering, while the skull expresses disdain for perishable goods, in line with Calvinist doctrine on the mortification of the self. In Augustine’s vision, the unity between the soul and nature resonates with the image of the tree as a symbol of the fruitful soul open to grace, shaping the saint as a mediator between the Creator and His creation, reflecting the Trinity manifested in the harmony between body, spirit, and community.

3.1.18. Scene of Angel with Musical Instrument (Left and Right) and Ornamental Motifs (See Figure 21)

- The scene depicts two musician angels positioned on a mural arch, one playing a violin and the other a guitar, both dressed in robes of warm tones and equipped with outspread wings that enhance their celestial character. From a descriptive iconographic perspective, these figures align with the Baroque visual repertoire that integrates music as a constitutive element of the celestial liturgy, evoking the presence of the divine through sound. The gestures of the angels, along with the decorative vegetation framing the scene, suggest a space symbolically transformed into a stage of praise, where the vibrant colors and instruments reinforce the festive dimension of spiritual glory.

- On an iconological level, according to the Panofskian method, these musician angels not only serve an ornamental function but also embody an allegory of heaven as an eternal choir, resonating with the Counter-Reformation ideals of heightened sensory experience in religious practice. The depiction of European instruments in a viceroyal context also reveals a deliberate cultural mediation that links evangelization with forms of artistic expression already familiar to the Andean population. Thus, these murals become pedagogical vehicles that translate celestial mysteries into accessible languages, projecting a vision of the afterlife that stimulates devotion through the senses.

- From a theological perspective, music is interpreted as one of the purest forms of contemplation of the divine order, as noted by St. Augustine in De Trinitate, where rhythm and harmony reflect the trinitarian structure of the cosmos. Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologica, argues that sacred singing elevates the soul towards God, facilitating the union between the creature and its Creator through ordered beauty. Calvin, although more austere in his approach, acknowledges music as an effective teaching tool as long as it is subordinated to the truth of the Word. Thus, the angels with instruments embody a synthesis of these conceptions, symbolizing the presence of the Spirit that harmonizes the ecclesial body through praise.

3.1.19. Scene of the Divine Shepherd, the Virgin of Monserrate, and Ornamental Motifs (See Figure 22)

- The scene represents two moments of strong symbolic and theological significance: to the left, a female figure, likely the Virgin Mary in a contemplative posture, is framed by rocky formations and lush trees, while to the right, Christ is seen carrying the cross and accompanied by a lamb, both situated beneath trees with rounded foliage. From the descriptive iconography, the first image can be recognized as a possible allegory of the Virgin as the throne of Wisdom or as the New Eve in meditation, and in the second, a representation of Christ as the Good Shepherd or Lamb of God in an attitude of redemptive offering. The natural surroundings reinforce the connection between the sacred and creation, a recurring characteristic of Andean colonial art.

- From an iconological perspective, the association of both characters with trees and landscape elements responds to a visual program of Christianization that merges Catholic doctrine with Andean worldview. In the case of Mary, her placement among rocks can be interpreted as an allusion to her doctrinal firmness, an image that dialogues with the Marian theology promoted at the Council of Trent. Christ, for his part, appears surrounded by trees whose shapes evoke the tree of knowledge, which refers to the parallelism between Adam and the Redeemer, consolidating a visual discourse on redemption through sacrifice. The lamb at his feet reinforces this reading and connects directly with Eucharistic symbolism.

- Theologically, Mary’s presence can be understood from De Trinitate, where St. Augustine highlights her role as a mediator between divinity and humanity in the incarnation of the Word. Thomas Aquinas deepens this idea by situating her as an instrument of grace in the salvific plan, while Calvin, albeit with reservations about her veneration, acknowledges her divine election as the bearer of Christ. The image of Jesus with the lamb aligns with the Augustinian vision of the Son as the perfect offering that reconciles the cosmic order disrupted by sin. Together, this scene proposes a synthesis of compassion and redemptive obedience, framed by a nature that also glorifies the work of the Creator.

3.1.20. Scene of an Angel with a Musical Instrument, an Angel Carrying a Chalice, and Ornamental Motifs (See Figure 23)

- The scene depicts two angels positioned at the ends of an arch, each with attributes that refer to the musical and liturgical realm. On the left, an angel carries a harp, with its strings represented with meticulous linearity, reinforcing its role as a performer of celestial music. On the right, another angel holds an open book that is visually identified as a chant codex or liturgical book, likely an antiphonary or psalter. From a descriptive iconographic perspective, both winged figures wear ornate tunics, with wings spread and hair in golden hues, following European artistic conventions adapted to the local Cusco style.

- From an iconological perspective, the representation of these angels can be understood as an exaltation of the eternal worship that takes place in heaven, paralleling that which is celebrated on earth. In the Counter-Reformation tradition, particularly solidified after the Council of Trent, the use of sacred music was intensely promoted as a means of spiritual elevation, which is reflected here in the presence of the harp as a symbol of praise. The angel with the book symbolizes the transmission of the divine word through liturgical singing, reinforcing the idea of the Word incarnate and perpetuated in choral proclamation. This iconography also acts as a mediator between the architectural space of the convent and the celestial sphere, creating an immersive visual and devotional experience.

- Theologically, according to St. Augustine in De Trinitate, harmonious music reflects divine unity and the structure of the cosmos as an expression of trinitarian order. St. Thomas Aquinas, in the Summa Theologica, argues that angels, as pure intellectual creatures, glorify God through incessant hymns, while for Calvin, singing holds a privileged place when performed in reverence and with doctrinally sound content. Therefore, the presence of these musician angels not only serves a decorative function but also carries a profound doctrinal significance that invites reflection, contemplation, and the soul’s participation in the harmony of the Heavenly Kingdom.

3.1.21. Scene of Arches with Ornamental Motifs and Anthropomorphic Figures (See Figure 24)

- The scene corresponding to the pillars of the cloister of the Monastery of Santa Catalina features a geometric plant decoration composed of symmetrical floral patterns, predominantly white roses set within diamonds crossed by diagonal lines. In terms of descriptive iconography, the repetition of the flower as a central motif can be observed, surrounded by buds in shades of red and green, carefully arranged to emphasize the architectural structure. At the base of the pillars are anthropomorphic figures with stylized wings, identifiable as winged tetramorphs or symbolic representations of the evangelists, whose frontal postures and serene gestures refer to their role in the spiritual support of the building.

- Through iconological analysis, these flowers refer to the Marian imagery extensively developed in Andean colonial art, where the white rose symbolizes the purity and virginity of the Virgin Mary, and its reiteration throughout the cloister reinforces the idea of her immaculate presence as the protector of the conventual space. The geometric shapes that contain these flowers evoke order, harmony, and stability, principles that were essential in counter-reformist thought and visually structured monastic life. The winged infant faces, far from being mere decorations, are understood as symbols of blessed souls or celestial spirits whose mission is to safeguard the walls of the temple, also evoking an angelological reading that supports the idea of communion between heaven and earth.

- From a theological perspective, Saint Augustine interprets the flower not only as a beautiful creature but as an image of the divine manifested in the simple and harmonious. Meanwhile, Saint Thomas Aquinas delves deeper into its symbolism by relating sensible beauty to the perfection of God, asserting that creation reflects divine goodness through order and proportion. Calvin, for his part, emphasizes the importance of visual decency in temples as a manifestation of reverence, avoiding excessive iconography, which is observed here in the balanced integration between ornamentation and architectural structure. Thus, this decoration not only adorns but also instructs and prepares the soul for the contemplation of the Trinitarian mystery contained in floral harmony and the protective spirituality of winged figures. This visual-architectural integration meets objective (iv), demonstrating that the mural program operated as a pedagogical and spiritual device for the conventual community.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Contreras, C. Iconografía de los murales del Monasterio de Santa Catalina de Cusco. Rev. Arch. Gen. Nación Perú 1999, 19, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Farago, C. Imagining art history otherwise. In Global and World Art in the Practice of the University Museum; En, J., Davidson, C., Esslinger, S., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluber, E. Los Monasterios Coloniales del Perú. Rev. Hist. 1951, 30, 120–140. [Google Scholar]

- Zecenarro, G. Arquitectura religiosa en el Cusco virreinal: El caso del Monasterio de Santa Catalina. Bol. Lima 2007, 29, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasini, E.P.; Córdova, M.; Castro, M.A.; García, A.P.; Siracusano, G.P. Identification of 17th–18th Century Pictorial Materials in Church Mural Paintings in the Cuzco Area (Peru) Using Micro-Invasive Analytical Techniques. ChemPlusChem 2025, 90, e202500298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassegue, R.; Letona, H. EvaluAación del estado de conservación de los bienes pictóricos del Monasterio de Santa Catalina. Patrim. Cult. 1983, 5, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas Bustamante, J. La escalera de Soto y la semántica ascendente del convento de San Esteban de Salamanca. Anu. Hist. Arte Esp. 2022, 17, 123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, W.D. De la Hermenéutica y la Semiosis Colonial al Pensar Descolonial; Abya-Yala y Universidad Politécnica Salesiana: Quito, Ecuador, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano, A. Colonialidad del poder, eurocentrismo y América Latina. In La Colonialidad del Saber: Eurocentrismo y Ciencias Sociales. Perspectivas Latinoamericanas; En Lander, E., Ed.; CLACSO: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2000; pp. 201–246. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Suárez, A. Painting Andean Liminalities at the Church of Andahuaylillas, Cuzco, Peru. Colonial Latin Am. Rev. 2013, 22, 369–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, K. Colonial Habits: Convents and the Spiritual Economy of Cuzco, Peru; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, C. Inka Bodies and the Body of Christ: Corpus Christi in Colonial Cuzco, Peru; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA; London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberena, L. Iconografía barroca en el Museo de Arte Religioso Colonial de Panamá. Estud. Vis. 2022, 14, 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Suárez, A. Heaven, Hell, and Everything in Between: Murals of the Colonial Andes; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mesa, J.; Gisbert, T. Historia de la Pintura Cuzqueña; Fundación Augusto N. Wiese: Lima, Peru, 1982; Volume 1–2, p. 830. [Google Scholar]

- Macera, P. Andean Mural Painting: 16th–19th Centuries; Milla Batres: Lima, Peru, 1993; p. 190. [Google Scholar]

- Silverblatt, I. Modern Inquisitions: Peru and the Colonial Origins of the Civilized World; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-8223-3295-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra Fernández, C. La Casa de las Cadenas de Cádiz: Arquitectura e iconografía contrarreformista. Patrim. Soc. 2021, 12, 33–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, C.M. Jerusalén celestial en los Andes: Apropiación iconográfica y autorrepresentación en la pintura mural tardo-colonial; Colonial. Lat. Am. Rev. 2019, 28, 106–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juberías Gracia, M. Relecturas del barroco en la pintura de género decimonónica. An. Hist. Arte 2021, 31, 205–222. [Google Scholar]

- Montes Sánchez, M.; Ramírez González, A. Producción artística femenina en la Real Audiencia de Quito. Cuad. Arte Colon. 2020, 15, 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, N. Estudio de Remodelación e Implementación del Monasterio de Santa Catalina “Museo de Vida Monástica”; Instituto Nacional de Cultura, Departamental Cusco, Dirección de Museos: Cusco, Peru, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, E. Meaning in the Visual Arts; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1955; pp. 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Aquinas, T. The Summa Theologica; Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Translator; Benziger Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Augustine, S. De Trinitate; McKenna, S., Translator; The Catholic University of America Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Calvin, J. Institutes of the Christian Religion; Beveridge, H., Translator; Hendrickson Publishers: Peabody, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, G.A. The Andean Hybrid Baroque: Convergent Cultures in the Churches of Colonial Peru; University of Notre Dame Press: Notre Dame, IN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, T.B.F. Toasts with the Inca: Andean Abstraction and Colonial Images on Quero Vessels; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mujica Pinilla, R. “El Arte y Los Sermones”, en El Barroco Peruano; Colección Arte y Tesoros del Perú, Banco de Crédito del Perú: Lima, Peru, 2002; Volume I, pp. 218–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D. Online video gaming: What should educational psychologists know? Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2010, 26, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vargas Febres, C.G.; Serra Lluch, J.; Torres Barchino, A.; Villagarcía Zereceda, A.V.; Gonzales Martínez, C.D.; Villena Ccasani, O.A. Iconography in the Mural Paintings of the Santa Catalina Convent as a Symbolic Element in Cusco’s Viceroyal Architecture. Heritage 2025, 8, 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090366

Vargas Febres CG, Serra Lluch J, Torres Barchino A, Villagarcía Zereceda AV, Gonzales Martínez CD, Villena Ccasani OA. Iconography in the Mural Paintings of the Santa Catalina Convent as a Symbolic Element in Cusco’s Viceroyal Architecture. Heritage. 2025; 8(9):366. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090366

Chicago/Turabian StyleVargas Febres, Carlos Guillermo, Juan Serra Lluch, Ana Torres Barchino, Angela Verónica Villagarcía Zereceda, Carmen Daniela Gonzales Martínez, and Olga Aylin Villena Ccasani. 2025. "Iconography in the Mural Paintings of the Santa Catalina Convent as a Symbolic Element in Cusco’s Viceroyal Architecture" Heritage 8, no. 9: 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090366

APA StyleVargas Febres, C. G., Serra Lluch, J., Torres Barchino, A., Villagarcía Zereceda, A. V., Gonzales Martínez, C. D., & Villena Ccasani, O. A. (2025). Iconography in the Mural Paintings of the Santa Catalina Convent as a Symbolic Element in Cusco’s Viceroyal Architecture. Heritage, 8(9), 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090366