1. Introduction

In light of the diversity of rural heritage, the rural built space acquires social, identity and affective meanings related to the relationship of communities with their past [

1,

2]. From this standpoint, rural built heritage is defined not solely by architectural landmarks but also by structures imbued with memory, image and symbol [

3,

4].

Rural cultural heritage is defined as the embodiment of a community’s way of life, comprising both material and immaterial elements and values, with historical evidence serving as a crucial corroboration of these claims [

5]. The notion of “heritage” (from Latin “patrimonium”, meaning “inheritance”) quantifies the totality of ancestral assets, while the concept of “derelict” (from English “derelict”) designates abandoned spaces whose original function has been lost over time. Thus, derelict rural heritage is defined as the heritage in a state of isolation and helplessness in the face of a threatening destiny in the rural environment [

6].

The Mureș Valley, one of the most important axes of Romania, crosses regions with a high density of historical and cultural vestiges, constituting a true corridor of civilisation. Since the medieval period, the valley has functioned as a site of interaction, exchange and synthesis between the East and the West, between the Austro-Hungarian noble world and local Romanian traditions. The region has been distinguished by the construction of numerous castles, mansions and summer residences, many of which were commissioned by prominent noble families such as Mocioni, Teleki, Salbek and Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen. These edifices, which are often strategically located on the smooth or hilly banks of the Mureș, functioned not only as aristocratic residences but also as centres of decision-making, culture and social representation. However, in the contemporary era, a significant proportion of these figures have been consigned to oblivion, resulting in a dissolution of their historical significance. From the perspective of a geographer, these places can be regarded as dusty gems in the Romanian rural landscape, representing vestiges of a bygone era, yet still bearing meanings that await exploration. The three castles forming the subject of this work, namely Bulci, Căpâlnaș and Petriș, delineate a symbolic arc, denoting a transition from the glory of the past to the uncertainty of the present. Each castle or mansion possesses a distinct narrative; collectively, they present a unified interpretive perspective on the intertwined themes of heritage, landscape and collective memory within the Mureș Valley region. The valley thus becomes not only a physical space but also a page of an outdated manuscript, in which layers upon layers of memories overlap.

The present study aims to analyse the three imposing buildings of Inferior Mureș Valley, Romania from the point of view of the relationship between memory, space and identity, and then to correlate the territorial dimension with the thoughts and feelings of the locals. The selection of the study area was not solely based on subjective criteria; rather, it was chosen due to its strategic importance in terms of the development of the region as a whole. These areas are recognised for their significant potential in contributing to the enhancement of the region’s prestige and international recognition. The objective is to ascertain the most plausible opinions in order to raise the community through the utilisation of long-gone vestiges in sustainable planning.

Our work contributes to the current literature on rural heritage spaces and derelict spaces by identifying the current negative aspects but also the positive aspects of tourism and local memory [

7,

8], being a pioneering study in Romania on the analysis of the perception of derelict rural castles. Our study is innovative theoretically as we are not aware of any previous studies on rural heritage of derelict castles.

This work is structured into several sections. The first section endeavours to delineate the theoretical and conceptual framework of the research, with a particular focus on the notion of derelict heritage in the context of contemporary cultural geography. The second section delineates the research methodology and adheres to the objectives and hypotheses that formed the basis of the work, as well as the methods used in collecting and interpreting data. The subsequent section is dedicated to the geographical framing of the three castles analysed, with a focus on how their positioning within the territory influences their cultural, functional and landscape value. The results of the study are based on the applied analysis from the field, by interpreting the interviews conducted with local stakeholders. Thematic analysis of the interviews reveals a focus on local memory, local stories and perspectives for revitalisation. The study concludes with a discussion of the findings and the formulation of conclusions.

2. Theoretical Framework: Rural Heritage, Derelict Spaces, Local Identity and Memories

In the context of the emerging interest in geographies of memory [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], there have been few debated memory issues connected to rural castles. Analysis of memories of local stakeholders is useful for better understanding how post-socialist societies remember the past and gives related insights into potential “uses” of such places as future museums see [

14,

15].

Place-based memories are those memories closely connected to place [

9,

10,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Such memories could be relevant by those who experienced past traumas [

18] or as simply memories coming back from histories. The memory work that local stakeholders undertake through their encounters with the past events are important drivers in remembering the political function of rural forgotten spaces. Memories are transmitted inter-generationally [

11], and the younger generation holds specific post-memories or frames of memories from their ancestors [

21], which could work nowadays for the rejuvenation of derelict rural spaces.

Heritage is understood not only as a collection of valuable objects or buildings but also as a form of spatialised memory that reflects the social, political and symbolic relationships of a community with its past [

22,

23]. Critical approaches do not merely engage in superficial aesthetic or historical assessments; rather, they delve into examining aspects such as exclusion, degradation and oblivion [

24,

25]. The concept that heritage is the outcome of a social and political process of selection, as opposed to an objective given, was proposed by Lynch [

26], who emphasised that the temporal perception of space plays an essential role in the formation of community identity. He draws attention to the risk that some elements of the built landscape, once significant, may be erased from memory with the loss of functionality or political reconfigurations. Consequently, spatial forgetting can be conceptualised as a form of symbolic amputation. This concept is further elaborated upon by Huyssen [

27], who proposes a theoretical framework delineating a spatial organisation characterised by the influence of memory, yet concomitantly susceptible to resignation or oblivion.

Derelict heritage is the result of an imbalance between collective memory and official narrative [

27], in which buildings that no longer serve dominant ideologies are gradually removed from the visible and conceptual landscape of the city or region [

28]. Morisset [

29] highlights that heritage is a matter of recognition and power. She argues that what is not validated by institutions or communities and left adrift becomes derelict not through a lack of value but through a lack of institutional and narrative attention. In this sense, derelict heritage becomes an invisible category of collective memory, a grey area between recognition and oblivion.

Recent studies in cultural geography and spatial anthropology have begun to direct particular attention towards the subject of modern ruins [

30]. These ruins are being examined not only as architectural forms but also as indicators of the relationship between time, functionality and identity [

31,

32,

33,

34]. Edensor [

35] begins his analysis with abandoned industrial sites in the UK, but subsequently develops concepts that are applicable more widely. For example, he proposes the idea that ruins are not seen as a sign of failure but rather as a different form of expression of the landscape, where memory is preserved informally, outside of the circuits of tourism and institutions [

36,

37,

38]. Edensor [

35] identifies these spaces as “places of productive ambiguity” that have the capacity to generate new forms of understanding of the past, even in the absence of traditional conservation. In this respect, the relationship between space and identity is fundamental to understanding heritage [

39,

40]: the rural castle is not merely an isolated building, but rather part of a socio-spatial ecosystem that encompasses the estate, the village, the forests, and auxiliary structures (chapel, stables, arboretum). It is therefore the product of a relationship between multiple temporalities and visions, and in the case of rural castles, the temporal poles represented by the nobility, communism and transition coexist in unresolved tension [

41,

42].

Rural castles represent a distinctive component of the European heritage landscape. While large urban royal residences have been the beneficiaries of constant attention, conservation and enhancement, castles in rural areas have often been subject to systematic neglect [

43]. In the geographical and socio-political context of Central and Eastern Europe, castles have become symbols of a fragmented past, marked by historical ruptures, regime changes and policies of marginalisation. In Central and Eastern Europe, including Transylvania and Banat, these structures were constructed in the 18th and 19th centuries, reflecting both Western cultural tastes (Baroque, Neo-Gothic, Eclectic) and the social domination of the noble elites over the local rural population. Rady [

44] has noted that such residences functioned not only as private spaces but also as centres of political and economic authority, from which control over surrounding villages, agricultural resources, and often churches was exercised.

The widespread nationalisation in communist Romania led to the expropriation of the elites [

45] and the transformation of rural castles into utilitarian spaces, such as sanatoriums, hospitals or headquarters for communist agricultural cooperatives. This transformation catalysed a symbolic revolt; thus, from prestigious monuments, they became simple functional buildings, disconnected from their aristocratic past. It is therefore often the case that rural ruins become victims of a policy of oblivion, in which the state, communities and even historiography prefer to ignore uncomfortable aspects of the past. In this sense, the rural castle becomes a space of identity ambiguity [

46], respected by some and rejected by others, but rarely coherently integrated into the national heritage landscape [

47].

In Romania, similar themes are evident in the works of Ion [

48], who provides both visual documentation and a critique of aristocratic neglect. Although the research primarily addresses the presentation of buildings, many heritage structures in regions such as the Mureș Valley have been omitted from conservation policies. As a result, these buildings are experiencing a systematic process of deterioration. The decline of noble heritage is attributed to institutional neglect, historical discontinuity and a lack of collective identity. Without a coherent policy for their preservation, many castles have become derelict heritage sites. These sites currently lack defined functions but possess potential for sustainable development through cultural tourism or community engagement. In the Mureș Valley, examples such as the Royal Castle in Săvârșin, Mocioni Castle in Bulci, Mocioni-Teleki Castle in Căpâlnaș and Salbek Castle in Petriș exemplify the intersection of rural context, heritage and collective memory within a culturally complex landscape.

It should be noted that the term “castle” will be used in this article, despite the existence of alternative terms in English that would be appropriate for these structures, such as “country house”, “mansion” or “manor”. However, in the common language of the region under discussion, they are referred to as castles. Indeed, a rural castle can be defined as an aristocratic residence located outside cities, with residential, economic and symbolic functions. Montclos [

49] contends that these castles should not be confused with medieval fortified citadels, but rather with residential complexes representative of the landed elites of the modern era.

3. Materials and Methods

The first step of our research focused on bibliographic documentation, focusing on the one hand on the specialized literature devoted to derelict rural heritage, and on the other hand on the historical evolution of the castles studied. Following this documentation, we defined the objectives, hypotheses and research tools (see

Table 1).

In order to achieve the first objective, a series of field trips were undertaken, in addition to the photographic documentation of the current state of the castles, in comparison with historical photographs. The latter are available online on the Hungarian heritage website Hungaricana [

50] and on the Romanian nobility heritage website [

51].

To achieve the second objective, an analysis was conducted of the position of the castles on historical maps of the 18th-century Josephine topographical surveys, which are available online on the Hungarian archives website Hungaricana [

50]. The following step involved the use of ArcGis Pro 2.8 software for the purpose of mapping all castles in the Mureș Valley, with the objective of producing cartographic materials.

The next and most consistent step was to conduct semi-structured interviews with relevant interlocutors from the communes where the three castles analysed are located. The interview comprised 17 questions pertaining to the history, current state and future prospects of these castles. The initial inquiries addressed respondents’ recollections of these castles, the emotions they associate with them and their perceptions of the evolution of these structures over time. The ensuing inquiries pertain to the respondents’ personal experiences and interactions with the castles. The subsequent inquiries delve into subjects pertaining to the contemporary condition of the castles and prospective strategies for their revitalisation.

The interviews were conducted in person, purposively, between March and May 2025. The selection criteria for interviewees were established based on several levels of representativeness. Firstly, relevant stakeholders in the localities where these castles are located were identified, with a professional connection to them being established (i.e., mayors, castle administrators, tour guides, priests, teachers, doctors, lawyers, forestry technicians). Secondly, we sought to identify individuals with a history of involvement with the castles, such as former administrators, caretakers or former medical practitioners who had served in these institutions. Thirdly, we sought to identify individuals residing in close proximity to the castles, observing their evolution on a daily basis. Finally, we were interested in elderly people in the locality who observed the evolution of the castles over many years, but who also have memories passed down from previous generations. The objective was to ensure that each of these groups accounted for approximately 25% of the total sample. The majority of interviews exceeded 30 min in duration and were meticulously recorded to facilitate accurate transcription. The demographic structure of the interviewees is delineated in

Table 2. Prior to participation, all respondents were informed about the entire research process and about the anonymisation of their responses, and they gave their consent to participate in the study. The research was ethically validated by the Scientific Council of University Research and Creation of the West University of Timișoara (no. 4558/29.01.2025).

The interviews were meticulously transcribed, ensuring the preservation of nuances such as pauses, laughter and sighs. Initial attempts to transcribe the interviews using semi-automated software were unsuccessful due to a high number of errors. These were caused by two main factors. Firstly, background noise was present in some of the interviews. Secondly, some respondents used regionalisms, proper names or place names that the computer systems were not able to recognise.

Thematic analysis was applied to the transcribed interviews (see [

52]). In a first stage, the researchers meticulously and systematically reviewed the interviews. Next, the researchers meticulously documented their observations and delineated the predominant themes that emerged from the aggregate of all the interviews. These themes were then refined into a smaller and more general set. Subsequently, the researchers compared the themes proposed by each of them, and those themes that were proposed by at least two out of three researchers were considered representative. The thematic framework that emerged encompassed local memory, identification of the agents responsible for the state of deterioration and the exploration of perspectives for revitalisation. Each theme was then assigned a colour. The interview text was subjected to a subsequent review, during which a theme was assigned a colour each time it emerged. In the final form, each coloured part of the text was extracted into a separate file, containing quotes from respondents related to that theme. It was imperative that the source, that is to say, the interviewee’s quote, was retained for each quote. This process facilitated a more objective perspective, thereby enhancing the clarity of the analysis.

4. Study Area: Derelict Castles in the Mureș Valley

The three castles analysed in this study are located in western Romania, on the lower course of the Mureș River, in Arad County, approximately 150 kilometres from the border between Romania and Hungary. This region of the valley predominantly features a rural character, with the nearest town being Lipova, which has a population of approximately 10,000 inhabitants [

53]. The county seat, Arad, is situated approximately 100 kilometres away [

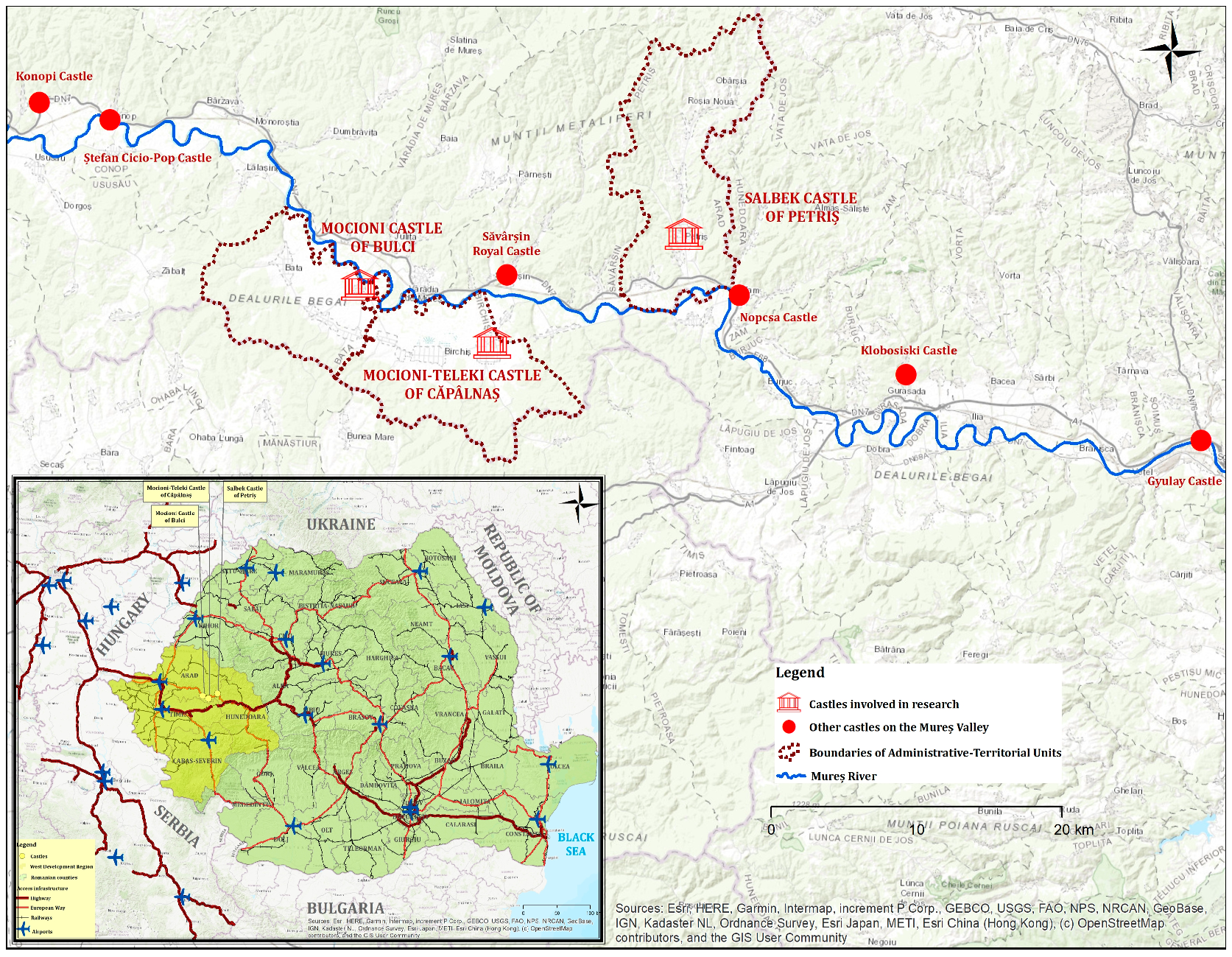

23]. However, the location is highly accessible due to its proximity to major transportation infrastructure. The entire corridor is situated along a significant national and European road (E68) and on a railway line that connects the capital cities of Bucharest and Budapest. The two castles under consideration are located to the south of the Mureș River (Bulci and Căpălnaș), whilst Petriș Castle is situated to the north. In addition to the three castles under scrutiny in this article, there are six other castles in the area, all located within a maximum distance of 5 kilometres from the river (see

Figure 1). These edifices, frequently situated in a strategic manner on the gentle or hilly banks of the Mureș, functioned not only as aristocratic residences but also as centres of decision-making, culture and social representation.

In most cases, these castles were the noble residences of large landowners or bourgeois families in 19th-century Austria-Hungary [

54]. After World War I and the disintegration of Austria-Hungary, the entire region returned to Romania, which brought changes in the ownership of some castles. Moreover, the agrarian reform of that period reduced the size of the estates. The fate of the castles changed abruptly after the advent of communism, when they were nationalized and converted into mental hospitals, schools for disabled children or headquarters for agricultural cooperatives [

48]. The fall of communism was followed by a turbulent period in which the castles continued to deteriorate, and no investment was made due to the uncertainty surrounding ownership. Today, the situation of the owners is largely clear, with the state returning the properties to their legal heirs, but their state of disrepair continues due to the large sums that would need to be invested.

In order to contextualize these castles within a national framework, it is important to note that their quantification is challenging due to the classification system employed by the Romanian Ministry of Culture. Specifically, certain castles are designated as class A, indicating national importance, while others are classified as class B, signifying local importance. Additionally, there are castles that remain unclassified. However, an association concerned with heritage [

51] mapped a large part of Romania’s castles approximately a decade ago and found that of the 744 castles surveyed, 326 are in poor or average condition, 59 are in a state of pre-collapse, 30 are in ruins, 226 have been maintained and are in good condition, and 101 have been recently rehabilitated or are in the process of being rehabilitated. The geographical distribution of the castles indicates that the majority of Class A monuments are located in central Romania, particularly in Transylvania. Class B monuments are predominantly located in the eastern region of the country, with smaller concentrations also present in the northwest and south. The western region of the country is distinguished by a significant number of monuments that have disappeared, and a considerable portion of the western landscape is characterised by castles that have not been designated as monuments.

Mocioni Castle, located in the village of Bulci (see

Figure 2), is situated a few hundred meters from the southern bank of the Mureș River and is a former residence of the noble Mocioni family, who built it in the mid-19th century. The complex covered an area of 9 hectares, including an arboretum, and consisted of the main building and a greenhouse, garages, stables and servants’ quarters [

55]. During the communist period, the castle was nationalized and converted into a hospital for tuberculosis until the early 2000s, when it fell into disrepair and entered a state of advanced deterioration. Today, the castle is owned by the Arad City Hall and is on the national list of historical monuments under code AR-II-a-B-00593, along with the complex and park [

56].

The Mocioni-Teleki Castle in Căpâlnaș (see

Figure 3) was built in the second half of the 19th century by the Mocioni family, modelled after the Petit Trianon in Versailles, in the middle of an 8 hectare estate [

48]. After the establishment of communism, the castle became a psychiatric hospital until 2025. The castle grounds also include a memorial site with the burial crypts of members of the noble family. Today, the castle is owned by descendants of the noble families, is listed on the national list of historical monuments under code AR-II-a-A-00594 [

56], and has been up for sale for several years.

Salbek Castle in Petriș (see

Figure 4) was built in the first half of the 19th century and is located in the centre of the village of Petriș, north of the Mureș River. The castle was owned by Count Salbek and other Hungarian noble families until the end of World War I. After the region was integrated into Romania, the castle became the property of the General Bank of Romania, and in the 1930s it was bought by a lawyer from Bucharest. After the advent of communism, the castle was nationalized and turned into a camp for the children of workers at the Arad sugar factory, after which it was taken over by the Ministry of Health and converted into a sanatorium for sick children. After the fall of communism, the castle became a school for children with special educational needs and a foster home for abandoned children. In 2006, the castle was returned to the descendants of the former owners, who sold it to the current Romanian owners, who want to completely revitalize it and turn it into a cultural and artistic complex [

57]. The castle, park and estate are listed on the national list of historical monuments under code AR-II-a-A-00642 [

56].

5. Results

5.1. Analysis of the Local Community’s Memory Regarding Castles

Castles, even in a state of disrepair, continue to be a central element of community memory. A review of the extant literature reveals that local residents ascribe a wide variety of emotions to the ruins, including pride, nostalgia, frustration and guilt. Despite the abandonment or dilapidation of numerous castles following the socio-political transformations of the 20th century, their significance has not diminished; rather, it has undergone a metamorphosis, transitioning from the tangible realm to that of collective memory and identity.

As for Mocioni Castle in Bulci, once an imposing noble residence in the rural landscape, it remains an important landmark in the memory of the local community, despite its current state of disrepair. Interviews with locals reveal a series of personal memories or stories passed down through generations, which paint a vivid and complex picture of the estate. Most of the inhabitants of Bulci or the surrounding village were involved in the work at the castle, benefiting from the fact that they perhaps had a different status in society. At the time, they were proud of what the noble family had to offer, but that former glory has faded over time. The families in Bulci made a living from working in the garden, the animal stables, the greenhouse and the estate’s kitchen: “women from the village were hired. They were trained as nurses... But everyone in the village was involved... my uncle was the administrator, I had an uncle who worked in the greenhouse” (I20); “My grandparents, great-grandparents, relatives, all of them were employed at the castle in Bulci. My grandmother was a cook. My uncle, my grandmother’s brother, was the maintenance mechanic for the castle’s power plant, another uncle of mine was the horse groom, and everyone in Bulci worked for the castle... everyone had something to do there” (I21).

Serving at the castle, the residents had the opportunity to be around the royal family, as they visited Bulci quite often. I20 recounts how her grandmother set the table for the nobles in the castle courtyard, receiving congratulations from Queen Elena of Romania herself: “my grandmother, when she set the table... they only had silver cutlery and silverware and a table service set... how the hunting dogs were being prepared... was the first plate. The second plate showed how the hunting horses were being prepared. The last plate was with rabbits and pheasants. And when the king’s mother came, she was very pleased. And then she called my grandmother and congratulated her. She had the honour of shaking hands with the king’s mother and the king!” (I20).

Among the stories recalled by the stakeholders are the good deeds that the Mocioni family did during the holidays, “during the holidays, all the children received gifts, and the servants too” (I21), and on special occasions or when they simply noticed that some of the employees were in need, “my grandmother’s mother was a war widow... and when she married her daughter, being poor, the count gave her all the dowry a girl needed to get married... and a pair of piglets as a wedding gift” (I21). Then “the Mocioni family gave property to a number of their servants whom they considered essential, whom they needed [...] they received white flour from the baron during times of famine in Romania and wood for heating...” (I21). The bohemian life at the court aroused admiration and respect among the villagers, and the property and the noble family were viewed favourably by them. I21 confesses that she was impressed by the estate: “in the morning we woke up to the chirping of birds in the park, with the beautiful smell of trees and flowers in the castle park. I remember that they also had birds, peacocks that lived for many years after the owners left the castle, and it was truly a special life, and I think that the entire population was emancipated thanks to the life they led alongside these special people.” I23 remembers from the stories of some neighbours that “the locals, after Sunday service, had a habit of going for a walk in the park,” and the grace and charm of that era is easily noticeable.

Another interviewee recalls with fascination how his uncle, who transported people by raft on the Mureș River, was frightened by the king’s plane. After a conversation they had, the king wanted to grant the old man’s wish, so he took him on a helicopter ride over the village, “gave him a helmet, gave him everything he needed and put him up in the plane. And the old man saw the village from above. That was his wish, to see the village. And alongside King Michael!” (I20).

During the communist period, when the castle was nationalized and turned into a tuberculosis hospital, the space took on a slightly different appearance, as the former elegance disappeared due to the circumstances of the time, but memories of that period still remain. Romances even blossomed against this backdrop, and one of the interviewees recounts how the hospital nurses got married in Bulci itself: “we became friends with the nurses and even my cousins and friends got married [...] three of them got married in the village” (I20). On the other hand, I21 recalls that while the hospital was in operation, he felt fear and repulsion towards the people admitted there “two people from the hospital [...] one who always carried a whip with him. And when we went to the castle, we were always scared that they would catch us” (I21). In addition, he remembers very well that the castle had the only telephone in the village, and when the locals needed to make a call, they would go there.

Many of the memories recounted from the Mocioni-Teleki Castle in Căpâlnaș indicate the presence of the heir, Eugen Teleki, who led a hard life after the castle was nationalized: “Teleki was left alone, living in train stations, on the mercy of people... They said that when he was the owner, they lived well in the village” (I27). And I30 reports that “my grandmother knew Teleki [...] from her voice I could tell how sorry she was that he had ended up in that state.” It seems that after the owners were dispossessed of the castle by the communists, they began to have health problems: “She was a sick woman. She probably fell ill when she was evicted in 1947... I think it was due to stress, because she wasn’t crazy, she went mad” (I27).

During the communist period, the castle grounds had several uses after the nobles left Căpâlnaș. A series of balls and dance parties were held in the main hall of the castle, “balls were organized... I was little, my young parents went to dance....” (I27), and later it became a hospital for various health problems, “in ‘86, my grandmother was hospitalized for a short time and I came to visit her and I remember something extremely surreal, the sick were hospitalized in a castle” (I29).

Moving on to the Salbek Castle in Petriș, the memories recounted by the interviewees are largely related to the life the castle took on after the nobles no longer had anything to do with it. Thus, in recent decades, a special school for children from disadvantaged backgrounds operated there, and they remember various activities they did together: “in this castle there was a children’s sanatorium and later a special school. During the time of the nobles, there was a lake on the Salbek estate where they used to go boating, and a sports field, which has since become a playground for children. I32 remembers the estate’s forest and the moments when he would escape there: “We played there in our free time, we went to the forest, the area is very large, about 18 hectares around the castle.

However, memories are also linked to the Salbek family, who had several centuries-old trees in the castle courtyard that they used as a place of judgment. The lord of the house also acted as judge, and all the problems that arose in the community were debated and analysed in the shade of these trees, under which the judgment chairs were placed. “Our grandparents told us... he judged and condemned them. They had to pay, work at the castle... he gave them punishments. And physical punishment... they had cells somewhere around there... they deprived them of their freedom” (I33). I34 mentions that he found documents in the town hall archives attesting to the presence of the Austro-Hungarian army in the area and that it killed several civilians in Petriș “the Austro-Hungarian army, in 1918, when it withdrew, shot several locals, 18 or 20 [...] the cause of death is written as “shot by the army””. The current owner of Salbek Castle in Petriș does not necessarily have any memories of this monument, as he is not originally from the area, but he found out about this impressive mansion during his research, wanting to restore a building with a historical past. “We called a company that also operates in Romania and has such properties for sale... We saw several castles [...] this one was easier to access and we were able to visit everything.”

5.2. Divergent Views on the Physical and Moral Deterioration of Castles

Looking at the current state of the castles, each stakeholder had an opinion on who was to blame for this complex process, but the main ideas that emerged from the discussions focused on local authorities, heirs and the passage of time. Many complain that although the heritage is officially recognized, administrative mechanisms are proving ineffective, delayed or completely absent when it comes to the conservation and rehabilitation of these monuments.

The advanced state of disrepair of Mocioni Castle in Bulci is the result of a complex set of historical, institutional and political factors, but above all of a crisis of responsibility. Although no official “accusation” is systematically formulated, the interviews indicate a plurality of guilt, in which public institutions, political parties, and even local communities are perceived as responsible for the abandonment of this historical monument.

The Arad City Hall is undoubtedly the main institution criticized for the condition of the castle; “the castle looks very bad, it looks pitiful...” (I20), says one interviewee, suggesting a chronic lack of interest on the part of the public administration. The castle was under the administration of the TB hospital for a long time, and interviewees clearly state that after its closure in 2011, “absolutely nothing has been done” (I20). Despite the fact that the estate remained the property of the Arad City Hall, it did not initiate any conservation or restoration measures, “as if deliberately allowing it to fall into ruin” (I21), as another respondent bitterly remarks. Another serious example of inaction is the refusal to return the castle to its rightful heir, Michael Stîrcea, despite the precedent set by the restitution of the castle in Căpâlnaș. “The Arad City Hall did not want to return it... but did absolutely nothing for this castle” (I21). This decision, perceived as arbitrary and abusive, has blocked any possible intervention in favour of restoration for two decades.

The interviews also highlight the lack of European funding, a considerable missed opportunity. Although Romania has been a member of the European Union since 2007, “absolutely nothing has been done” (I20) in this regard. One respondent puts it bluntly but realistically: “It’s probably not the EU’s fault, it’s probably our fault, those of us who don’t attract the funds” (I20). However, this self-deprecation is more a form of disappointment with a passive bureaucracy that does not formulate projects or take action.

Responsibility is diluted between the Arad City Hall, the County Council and the Banat Museum, which “comes and films how much the castle has deteriorated” (I21), but also other institutions that “only promise and do nothing” (I21). Another recurring theme in the stakeholders’ discourse is the hypocrisy of political parties and unfulfilled election promises. Several interviewees emphasize that before each election, politicians visit the castle and include its renovation in their program, but “none of them did anything, absolutely nothing” (I21).

The only notable initiative was the temporary intervention of the “Ambulance for Monuments” association in 2020, which began cleaning up the area around the former greenhouse of the castle. Although they were greeted with enthusiasm by the community, “the villagers immediately wanted to reward them with pies” (I21), these volunteers did not return. The action remains a symbol of failed good intentions, without institutional continuity or logistical support from the authorities.

In contrast to institutional passivity, the local community, especially those who have left but remain emotionally attached to Bulci, are trying to mobilize through civic initiatives. The recent petition addressed to the authorities is an expression of an emotional memory: “they have left Bulci, but their hearts remain there” (I20). This form of involvement, although still weak in terms of resources, is an indication of local historical awareness, which perceives the castle not only as a building but as a landmark of identity. And yet, disappointment persists: “no one wants to take on a role... if it is not remunerated in any way, no one will do it pro bono” (I22). This observation puts its finger on a systemic wound. In the absence of a mechanism for legal or financial accountability, no one intervenes.

Stakeholders point very clearly to a serious lack of clarity regarding the legal status of the castle and the surrounding land: “The park is listed as belonging to the County Hospital. The castle is listed as belonging to the town hall. The town hall is actually at the Arad Local Council” (I23). In this bureaucratic tangle, responsibility is lost, and inaction is justified by a vicious circle of institutional formalism. No funds can be allocated because it is not clear who owns it, its use cannot be changed because the Ministry of Health does not approve, and in the meantime, the deterioration continues. “The first sign of protecting a monument is repairing the roof” (I23), says one of the respondents, emphasizing what is basic technical knowledge in heritage management. The lack of even minimal preventive conservation measures is seen as a criminal act of omission: “someone must be held criminally responsible” (I23).

The lack of a long-term development vision on the part of local authorities, dominated by electoral thinking and focused strictly on personal or symbolic gains during their short terms in office, is also cited. One of the most powerful rhetorical images comes from an interviewee who compares the castle to “an unpolished gem” (I23) that local authorities ignore or even reject as a burden. There are accusations of fear of responsibility, lack of strategy and incompetence in transforming heritage into a resource for development: “you have to be crazy as a community to give it up...” (I23).

In addition, there is a clear opinion that the state is not only inefficient but also lacks the minimum will to act: “the state is the worst administrator” (I24). Although it has the potential to mobilize greater resources than a private entity, the state is paralyzed by passivity, lack of initiative and interest. No attempt has even been made to attract European funds or sell the castle to entities capable of intervening. “A little more and there will be wolves, foxes, snakes...” (I24), says one interviewee, metaphorically summarising the state of complete abandonment.

These statements add new layers of pain, clarity and anger to the already bleak landscape surrounding the castle in Bulci. Although there are people who want to get involved, who understand the heritage, historical and community value of this place, there is no functional mechanism through which these intentions can be turned into action. Institutional indifference, legal obstacles, political irresponsibility and civic resignation form an ecosystem of slow and irreversible degradation.

Moving on, the Mocioni-Teleki Castle in Căpâlnaș is perceived by the community as a building that, despite the passage of time, has been saved from degradation by its institutional function, first as a sanatorium and then as a psychiatric hospital. I30 emphasizes that “if it hadn’t been a sanatorium, it wouldn’t be here,” indicating a pragmatic view of heritage conservation, not so much on the initiative of any cultural authority, but rather out of the practical need of the healthcare system for functional spaces.

The interviewees mention an ambiguous overlap between public institutions and private property, specific to the post-communist transition. The castle was owned by the Ministry of Health, then leased by the County Council from the heirs, and today it is under the same contractual arrangement. The perception is that only the presence of the Arad County Council has saved something, and if the patients were moved to another building outside the domain, the heirs must find a solution: “if the County Council is no longer there... they have to sell it” (I28).

Although there is recognition of an inevitable decline, “I don’t think it was evolution... rather involution” (I29), minimal maintenance—“painting, putting a tile, adding a brick if it falls, mowing the grass” (I24)—has allowed the appearance of stability to be maintained. Compared to other castles such as the one in Bulci, Căpâlnașul is seen as an example of passive rescue, but the fact that it was inhabited and used guaranteed its survival, but not its restoration. The idea emerges that the heirs do not have the necessary means to manage the castle: “I don’t know if the family has the financial means to provide security” (I29). Thus, the castle remains suspended between the impotence of the state, the disinterest of investors and the deadlock of the owners who “care too much about the price... If you’re not using it, just leave it for a while, let whoever comes along come, so they have the money to restore it or do whatever needs to be done with it” (I30).

The interviewees point to a lack of systemic vision, rooted in post-war communism, considered “the cataclysm that interrupted aristocratic continuity” (I29). The communist regime is perceived not only as responsible for material degradation but also for erasing the memory of noble families: “they wanted to denigrate its history and the family that owned it” (I31).

After 1989, the lack of a national plan to reactivate the returned heritage is critically highlighted: “the Romanian state should have invested in the immediate post-revolutionary years... even if it was not the owner” (I30). Frustration also arises at the lack of national leadership in the field of heritage: “we do not know how to appreciate our values and we do not know how to develop tourism” (I30). At the same time, the lack of local entrepreneurial spirit is also invoked: “there are rich people in the area who do not see the potential” (I30). It is suggested that in a country such as Germany, “these buildings would have been exploited to the full for tourism” (I30), highlighting a crisis of vision and collective involvement.

The Mocioni-Teleki Castle in Căpâlnaș is an example of “institutional survival” rather than conscious restoration. Its function as a sanatorium has preserved its structure but not its historical dignity. Restored but not exploited; inhabited but not integrated into tourism; maintained but in danger of abandonment, the castle reflects the major dilemmas of Romania’s post-communist heritage.

Salbek Castle in Petriș is in a state of partial disrepair, especially the outbuildings, which have been affected by the weather and lack of maintenance: “discovered them and some even look very bad” (I34). The main body of the building has fared better because, over time, it has housed various institutions (sanatorium, school, foster care centre), which ensured the minimum necessary maintenance, including consolidation work and keeping the roof in working order. At present, the castle is no longer used by any state institution, as ownership was returned to the descendants of the former owners and then sold to a company that intended to restore it and develop a cultural and tourist project. This plan was abandoned due to Brexit and the impossibility of attracting European funds. The estate has now been bought by someone else, who wants to invest in a unique cultural and tourist space with a large-scale project.

The establishment of the communist regime was a turning point for many of Romania’s imposing buildings, and Salbek Castle was no exception to the rule: “Whether you liked it or not, it was a situation where no one asked you if you wanted it or not. They took it by force” (I33). “The communists came, nationalized it, and made some interventions to consolidate it. The architectural specificity of the building was not taken into account. The evolution of the castle seems to mirror the historical evolution of Romania” (I34). After 1990, the heirs initiated proceedings to reclaim the property, as was the case with many other estates in Romania. With the resumption of the restitution process and the loss of state control, activities in the castle were halted because “no one was willing to invest money in something that was not sure to work” (I32).

5.3. Proposals for Revitalizing the Castles in the Mureș Valley

The local community in Bulci is exploring various scenarios to give the castle a new lease of life. One of the major proposals is to transform it into a space dedicated to the care of vulnerable people, given the benefits of the local climate: “I would give it a purpose, as we have children with disabilities or elderly people with lung problems... the air is very ozone-rich there” (I20). This approach could create jobs and ensure sustainable use of the estate. From an economic point of view, financing such a project would require a self-financing model: “either a sanatorium... these would be the only ones that could... that could also be self-financing, otherwise it’s not possible, because... the park alone is 9 hectares... it costs money to maintain it” (I22). The rehabilitation of such a large castle requires significant investment, which complicates the search for an investor willing to take on this challenge.

Mocioni Castle in Bulci is not only a historical monument but also a focal point of the local community’s identity, with the potential to influence both the economy and the social life of the village. As one of the stakeholders states, “people left the village because the village has no life anymore, they only knew how to work... on the castle grounds. There is no other... place to work” (I21). This statement highlights the negative impact of the castle’s deterioration on the village, turning it into an almost abandoned place, where houses remain uninhabited but are not sold because “they are tied to them... their parents are in the cemetery [...] they don’t dare to sell their properties” (I21).

One of the stakeholders, looking for alternative ways to put the castle in a more favourable situation, understood that there is an external risk that the estate could be taken over by NGOs specializing in heritage from across the border, so it would no longer end up in local hands, expressing his concern that “there are NGOs, for example, in Hungary, specialising in the recovery of castles and properties in Romania [...] we will wake up at some point and find that they have taken them back” (I23). Although there are some fears about the loss of national heritage, international cooperation could bring funds and expertise for the restoration of the castle. Another idea proposed by the community is to create a shareholding structure or a joint initiative to transform the castle into an event and tourism centre: “I was actually thinking about starting an NGO to take over the castle as a kind of community with a purpose” (I23). Such a project could generate income from organizing events, supporting the long-term maintenance of the estate. A unique feature of the castle in Bulci is its greenhouse, a distinctive curved glass structure that could be converted into a restaurant or event space: “The greenhouse could be converted into a restaurant or a really cool event hall” (I23). This reuse could attract visitors and create an additional point of interest. Tourism development through the organisation of festivals and cultural events is another possibility discussed: “This folk festival in the village, if it were held in the castle park, would be better...” (I23). Initiatives of this kind could help promote the castle and attract tourists. Revitalizing Mocioni Castle in Bulci requires identifying a sustainable development model that combines tourism, culture and economic benefits for the community. “If we could find a hundred people, we could already raise some money” (I23).

The future of the Mocioni-Teleki Castle in Căpâlnaș depends largely on the intentions of the owner and the interest of investors. As one stakeholder notes, “I can’t know the intentions of those who claimed it... they want to live there, they want to build a hotel, they want to build an event hall. In the end, it is the owner who decides” (I24). This highlights the difficulties of protecting heritage when buildings of historical value are privately owned. From a tourist point of view, the castle has considerable potential: “it is a monument of art that can be visited by many foreigners, because there are not many left, even in the country” (I25). The building, together with the arboretum and the old crosses in the middle of the estate, could become a major point of interest for the area.

Among the solutions proposed for revitalisation, transforming the castle into a hotel or guest house is one of the most discussed “with minor repairs, it can be fixed up properly” (I28). Such an investment would generate jobs and could contribute to the local economy, “to make something out of it [...] to give work to the people of Căpâlnaș” (I27). This aspect is essential for the long-term sustainability of the project. At the same time, there is also interest in transforming the castle into a hunting centre or an agritourism venue “well, it would work for agritourism, it would work, I know, hunting, since it’s an area with a lot of game” (I28). The proximity of forests and the Mureș River would facilitate the development of such activities, attracting visitors who are passionate about nature and adventure. Another respondent emphasizes the need to find an investor with sufficient resources: “First of all, we need to find an investor willing to spend around 5-6-10 million euros” (I30). This statement highlights the financial challenges associated with restoring a heritage monument. The potential is huge, but its future depends on the owner’s willingness, the involvement of the authorities and the identification of a suitable investor. “It must return to the tourist circuit” (I31).

Salbek Castle in Petriș is in the middle of an ambitious restoration and revitalisation project, with the aim of turning this place into a renowned tourist attraction. As one stakeholder states, “to put it on the map, not only of Romania, but also of Europe” (I32). Another stakeholder emphasizes that “if this castle comes to life, the entire commune, the community, will benefit and gain” (I34).

The current owners’ initiative is aimed at opening the estate to visitors and creating a large-scale cultural and recreational space. One of the projects already implemented is the organisation of classical music masterclasses, where internationally renowned artists offer courses to young musicians: “There have been masterclasses, classical music courses where internationally renowned soloists have taught here” (I34). These cultural events contribute to promoting the castle and strengthening its image as a place of artistic excellence. Future plans include the development of an Ayurvedic and balneotherapy centre, a unique concept in Romania, inspired by similar models in the Czech Republic. “The Ayurveda centre [...] is a unique program in Romania” (I35). Thus, the castle will not only be a tourist attraction but also an exclusive health and relaxation centre.

As for the structure of the castle, the original elements, such as the semi-basements and brick vaults, will be preserved: “the semi-basements, basements, brickwork, vaults, and so on, which we want to keep” (I35). This approach ensures that the restoration will respect the architectural authenticity of the monument. Another innovative aspect is the catering system proposed for future visitors: “for what we are doing there, it is a system that is a little different from the normal public catering system” (I35). Menus will be set in advance, allowing for the preparation of sophisticated dishes tailored to the needs of those who choose to stay for treatments and extended stays.

The restoration plans are well structured and are being carried out in stages “We are starting in April to rebuild the castle with the three buildings for which we had building approval. And I hope that by the end of the year we will also have approval for the rest of the buildings” (I35). Estimates indicate that the restoration will be completed by 2028, at which point the estate will be fully functional. One of the attractions will be the relaxation area, which will include a swimming pool, massages and anti-aging treatments. “We are creating a pool area, a relaxation area, a massage area, and all kinds of top-of-the-line and anti-aging treatments” (I35). These facilities position the castle as a place dedicated to exclusivity and physical and mental regeneration.

The estate’s park will also be redesigned and will include a statue area with works of art by Romanian and foreign artists: “my wife bought three large statues for this association because she wants to create a statue park, especially with glass statues” (I35). These elements will enrich the estate visually and culturally, offering visitors a unique artistic experience. However, visits to the castle will be limited: “it will be something to visit, but access will be quite restricted [...] not free, not with an entrance ticket” (I35). Access will only be allowed during special events or for those staying inside the estate, which will help maintain the exclusive character of the place.

Salbek Castle in Petriș is undergoing a complete transformation, and cultural investments and initiatives will consolidate its status as an elite destination: “we must make this wonderful area something that not only the people of Petriș can enjoy, but anyone who comes from anywhere to see what is here” (I32). By combining art, wellness and uniqueness, the estate has the chance to become a landmark in Romanian and European tourism.

By revitalizing these monuments, the region can become an example of integrating cultural heritage into sustainable planning, generating economic, social and environmental benefits. Cultural events, festivals, historical tourism and biodiversity protection initiatives can transform the Mureș Valley into an example of balanced development, where the past and the future meet harmoniously. Thus, these monuments are not just relics of history but bridges to a sustainable future, where heritage conservation becomes an engine of progress. If this process continues, the Mureș Valley can become a model of cultural and economic regeneration, demonstrating that respect for history can be a catalyst for sustainable development.

6. Discussions and Conclusions

The present comparative analysis of the three castles demonstrates the major role of collective memory in the care of heritage, even in cases where the heritage is in a state of dereliction. Moreover, this cultural heritage functions as an anchor for local identity [

31,

39] and as a repository for memory [

4]. This emotional dimension corroborates the extant literature, which emphasises that heritage is not only material but also exists through community resemantisation [

5]. Rural heritage has been identified as a significant catalyst for local development [

3,

58,

59]. The development of castles has been posited as a potential strategy to revitalise rural areas [

60]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that rural communities are characterised by a strong sense of history and local distinctiveness [

61,

62].

In all three cases, the life cycle of the castles was similar: they were constructed in the 19th century, during the Austro-Hungarian period, by nobles and landowners as permanent and secondary residences. Following the conclusion of the First World War and the subsequent integration of the region into Romania, a shift in ownership regime occurred. However, the function of the castles remained unaltered. The most significant development in this regard was the advent of communism and its concomitant nationalisation. The new functions of the institutions primarily encompassed healthcare (sanatoriums, hospitals) and education (camps and schools for disadvantaged children). During this period, the castles were not restored, but they were kept functional. In the aftermath of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a period of considerable confusion ensued, primarily due to ongoing legal disputes concerning ownership. Following the restitution of Bulci Castle to the ownership of Arad City Hall, the other two castles were returned to the heirs of the former owners. Concurrently, the erstwhile educational and healthcare functions of these castles were abolished, and presently, none of the castles are in use. This is also due to the substantial investments required. Despite the Arad City Council’s role as the proprietor, there was no intervention, resulting in the castle’s significant deterioration. In contrast, the castle in Căpâlnaș functioned as a hospital until 2024 and is currently in a satisfactory state of preservation. Nevertheless, the presence of a financially robust proprietor is imperative for the successful realisation of this undertaking. In contrast, the situation in Petriș is more advanced, in that the castle, which has been sold on multiple occasions, is now in the early stages of rehabilitation. There are plans to convert it into a cultural and tourist attraction. A synopsis of the primary conclusions can be found in

Table 3.

The first hypothesis was partially validated, insofar as the existence cycle of these castles was shown to be analogous to that of other heritage elements in the post-communist context. However, they are all in a state of disrepair. A complex set of factors, in addition to political factors, contributed to this situation. The second hypothesis was partially validated, in the sense that there is still a fascination and nostalgia for the castles among the local community, which considers them an anchor for the development of the entire area. The third hypothesis was also validated, in the sense that stakeholders believe that it is not local or national institutions that can save the castles, but financially powerful private investors. This would close a cycle and restore the castles to their original 19th-century purpose as properties of aristocratic families.

Policy recommendations refer to several levels. First, at the national level, support is needed in terms of legal and bureaucratic issues, as well as funding. Even though many castles are privately owned, they represent a common identity asset. Secondly, local authorities and communities would have much to gain from the repurposing of castles. They must therefore work with owners to promote the history and heritage significance of castles more effectively and widely. This group, together with county authorities and NGOs, should also consider cultural and tourist itineraries.

There are currently examples of success in Romania involving various actors. For instance, the mansion in Foeni, western Romania, was renovated with public funds by the County Council, transforming into a cultural space [

63]. Banffy Castle in Transylvania was included in the World Monuments Watch at the initiative of the Transylvania Trust Foundation and was rehabilitated through a combination of public funds, European Union Phare funds and Norwegian funds, and now hosts an international festival [

64]. Other castles (Săvârșin, Bran) were returned to their heirs and renovated by them [

65,

66].

A potential limitation of this study is its focus on only three castles, which precludes the possibility of extrapolating the results to the entire area or country. Instead, the results reflect the local specificity of the noble heritage of the Lower Mureș Valley. However, conducting a study encompassing multiple domains would have necessitated significant logistical challenges. A further limitation is the subjective nature of the interviews, as some interviewees exhibited an emotional attachment to the castles, while others viewed the subject more dispassionately. However, this is a relatively common occurrence in qualitative research, and the aggregate of all interviews provides a coherent and balanced overview. A further limitation is that the analysis reflects a snapshot of the built heritage situation at the time of the interviews, implying that the information is dynamic in nature. Subsequent restoration processes, administrative interventions or functional transformations may occur and alter both the perception of stakeholders and the physical reality of the sites analysed. Moreover, the restricted access to archives and technical documentation hinders the capacity for historical contextualisation and meticulous evaluation of prior interventions [

67]. Finally, a limitation of the study is the heterogeneity of the participants interviewed. Some individuals possessed a remarkable capacity for conversational exchange, demonstrating an ability to formulate comprehensive sentences that could be seamlessly integrated into our results. In other cases, despite the respondents’ views aligning with those of other interviewees, the answers were succinct and concise, which rendered them challenging to incorporate into the text. Consequently, the most substantial and intricate answers were incorporated into the text to ensure clarity for the reader.

Further research could be conducted on several castles throughout the Mureș Valley, especially since each case is unique. Research that evaluates the state of deterioration of the castles in a more objective and technical manner is also necessary. Studies on the urban integration of castles into regional tourist circuits would shed more light on their potential.