Religious Cartography as a Segment of Thematic Cartography: A Case Study of the Archdiocese of Đakovo–Osijek

Abstract

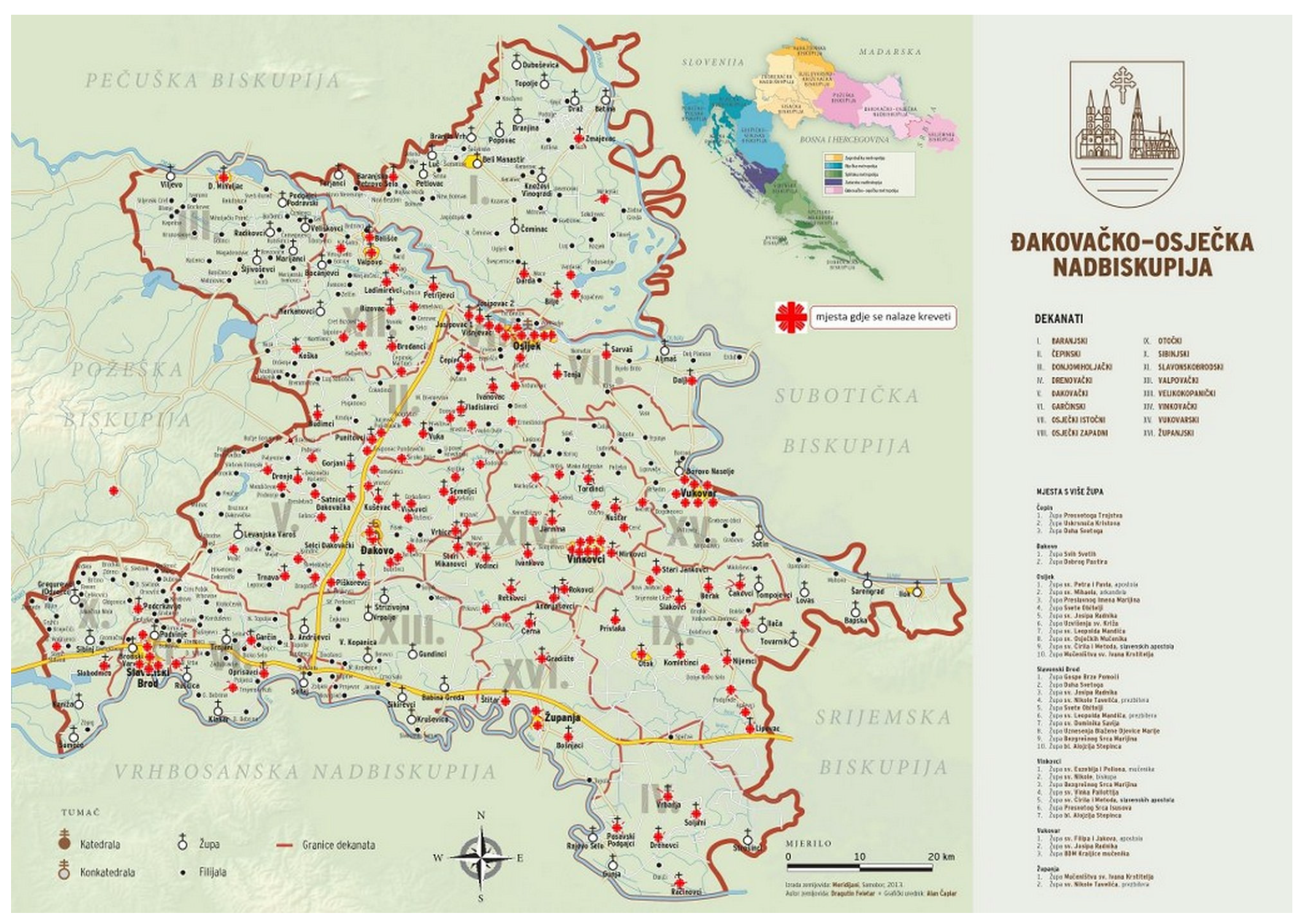

1. Introduction

State of the Art in Thematic Religious Cartography

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Previous Research

- Scanning:

- The map was scanned in September 2016 using a Contex 600, a large-format rotary scanner. The process was supported by the original digitization software WIDEimage. The output resolution was 500 dpi, with 24-bit color depth, producing an image of 11,703 × 8278 pixels. The image was saved in JPEG format for practical manipulation in CAD and GIS software, with a total file size of 63.9 MB.

- Initial Processing:

- 4.

- Georeferencing:

- 5.

- Accuracy Assessment:

- 6.

- Vectorization:

- 7.

- Overlay and Comparison:

2.2. Study Area and Historical Context

2.2.1. Boundaries of the Archdiocese

2.2.2. Ecclesiastical Content on the Map

2.3. Data Collection in the Process of Creating the New Map

- Digital Orthophoto Map (DOF5)—State Geodetic Administration (DGU):Data Extracted: High-resolution aerial imagery used for visual verification of the position of churches, roads, rivers, and administrative borders.

- Format: Raster (GeoTIFF).

- Scale: 1:5000.

- Reference: State Geodetic Administration [23].

- Croatian Base Map (HOK):

- Data Extracted: Base map elements including transportation networks, hydrography, and settlement structure.

- Format: Vector and raster (official layers in HTRS96/TM).

- Reference: State Geodetic Administration [23].

- Digital Cadastral Plan (DKP) and Register of Spatial Units (RPJ):

- Data Extracted: Precise cadastral boundaries, names of settlements, and spatial hierarchy.

- Access Method: WFS (Web Feature Service).

- Reference: State Geodetic Administration [23].

- Register of Geographical Names (RGI)—DGU:

- Data Extracted: Toponyms of settlements, parishes, protected areas, and geographic entities.

- Format: Point vector layer (shapefile).

- Reference: State Geodetic Administration [24].

- OpenStreetMap (OSM):

- Data Extracted: Vector layers for roads, rivers, and settlement layouts.

- Usage: Supplemental data where official sources were lacking; filtered for thematic simplification.

- Reference: OpenStreetMap contributors [25].

- DIVA-GIS—Administrative Boundaries:

- Data Extracted: National- and diocesan-level boundaries for Croatia; used for defining deanery divisions.

- Format: Shapefile.

- Reference: DIVA-GIS [26].

- Official Website of the Đakovo–Osijek Archdiocese:

- Historical Map of the Diocese of Bosna or Đakovo and Srijem (Görög & Lipszky, 1826):

- Google Maps and Address-Based Coordinate Extraction:

- Data Extracted: Geolocation of churches and church institutions using postal addresses and satellite view.

- Usage: Positional accuracy of point features.

- Reference: Manual extraction using Google Maps API.

Data Collection

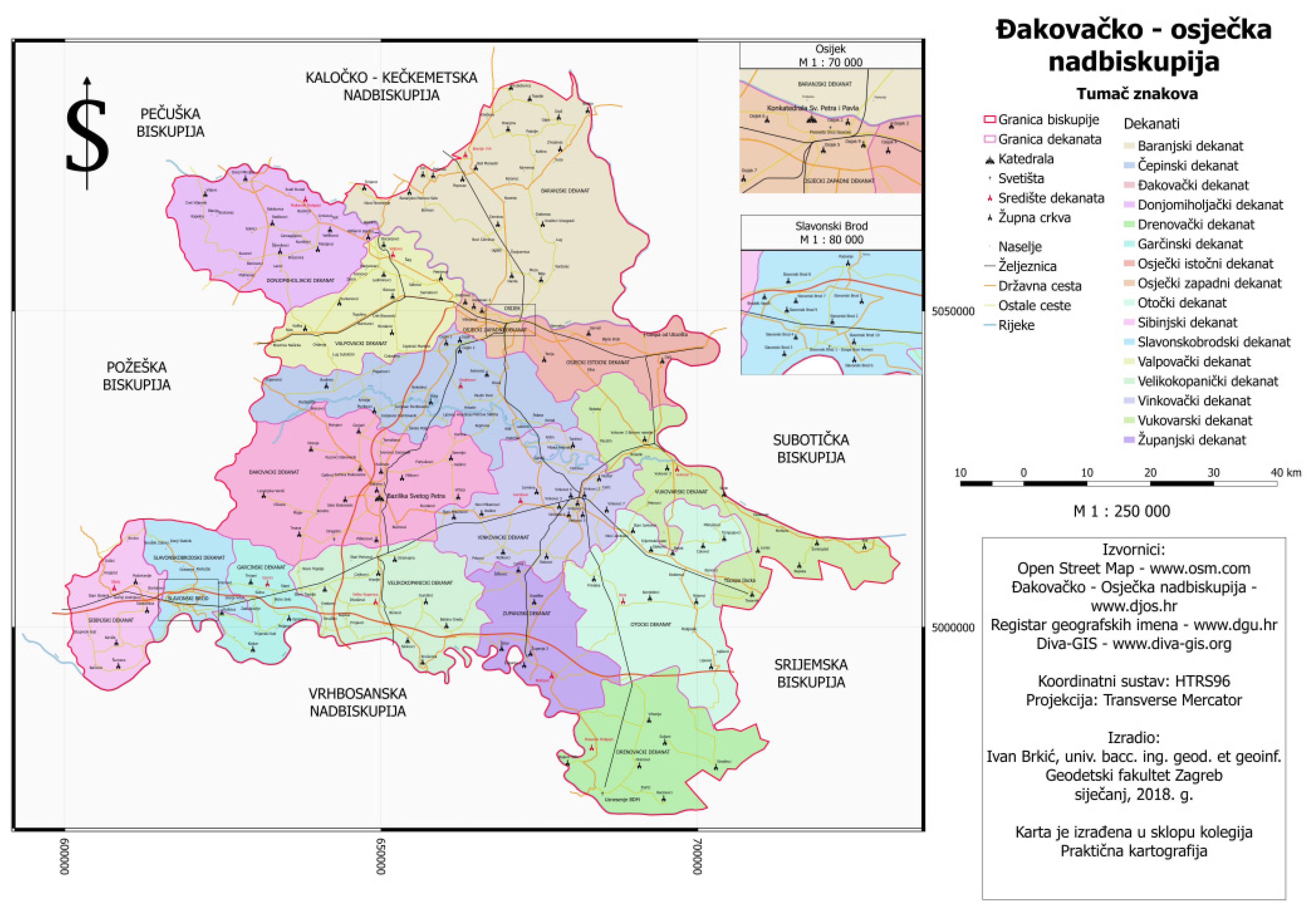

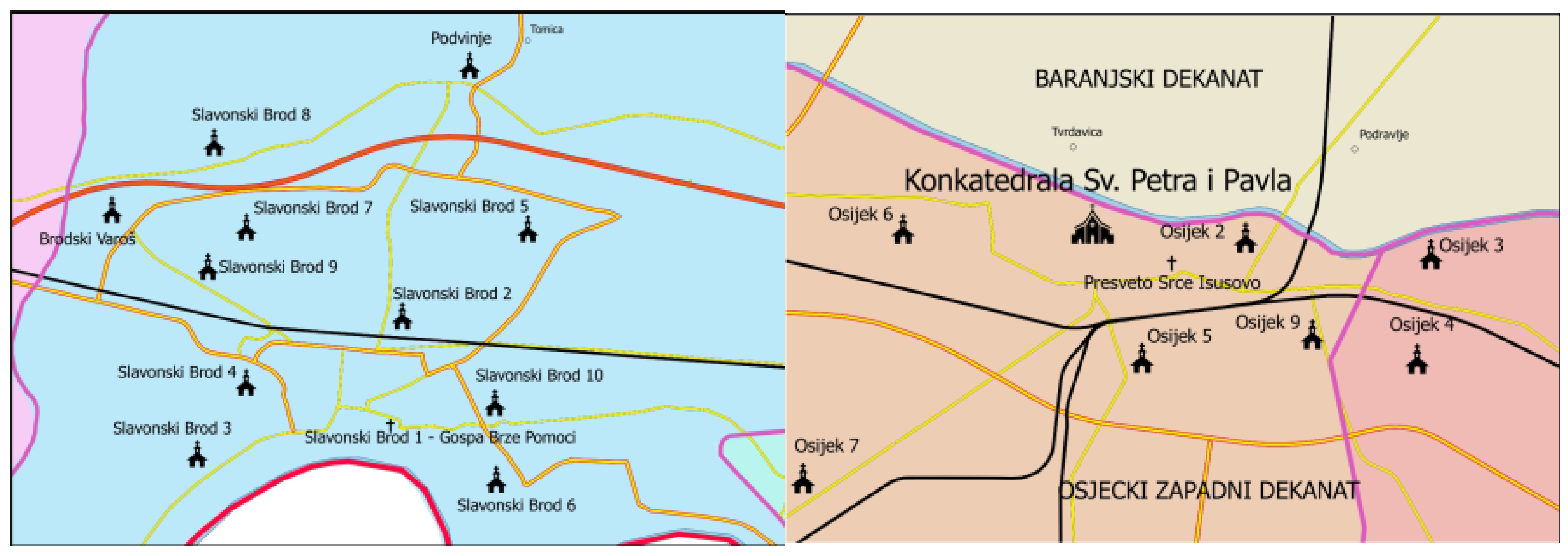

2.4. Creating a New Map

2.4.1. The Coordinate System and Scale

2.4.2. Data Processing

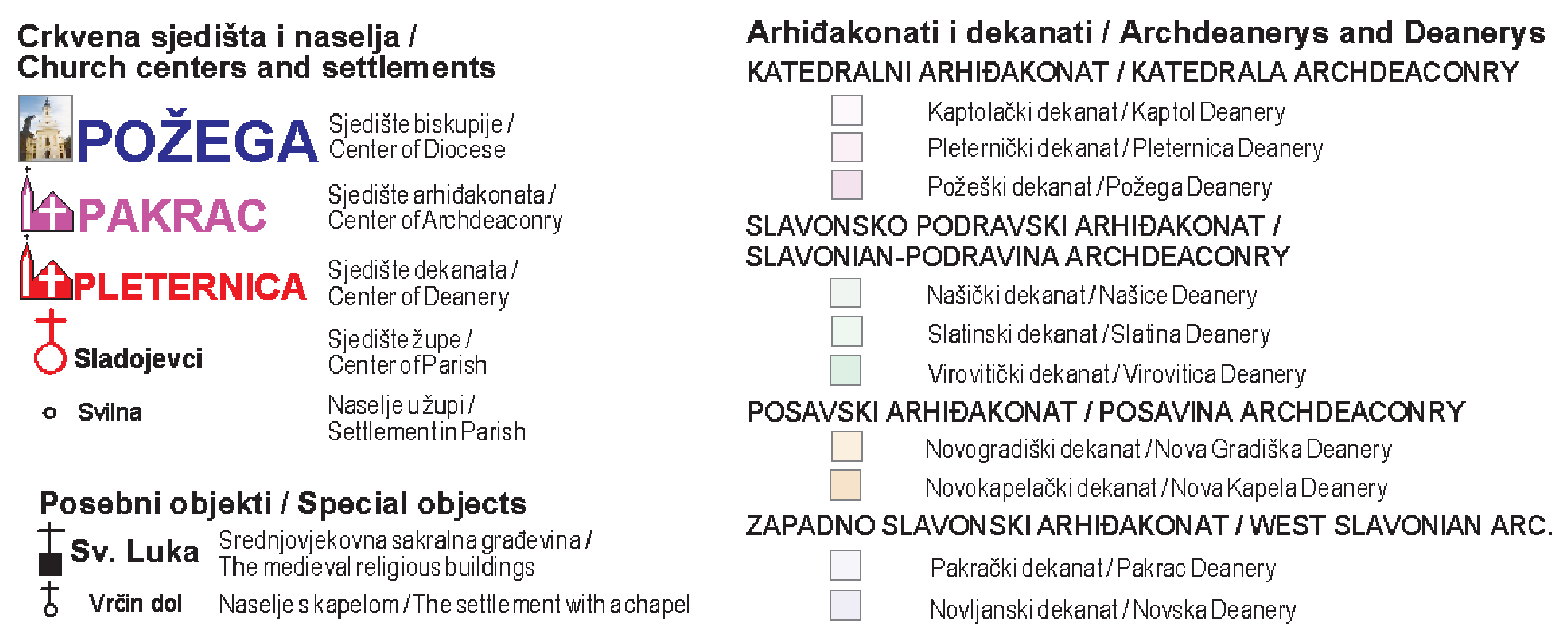

2.4.3. Cartographic Design

2.4.4. Creating the Final Map

2.4.5. Integration of Historical and Contemporary Data

2.4.6. Cartographic Design Process and Symbolization Inserted

2.4.7. Readability Testing and Review Workflow

2.5. Historical GIS and Spatial Humanities Context

- Ref. [40] emphasizes methodologies for temporal and spatial precision in HGIS projects, including the challenge of aligning historical boundaries with modern coordinate systems;

- Ref. [41] explores case studies in Historical GIS and emphasizes the importance of integrating textual sources with spatial layers;

- Ref. [6] stresses the interpretive dimension of Historical GIS, noting that spatial representations are not merely technical products but narratives embedded with meaning;

- Ref. [42] discusses the reconstruction of religious and administrative geographies in Europe using parish-level historical data and spatial interpolation.

- Coordinate Transformation: Aligning historical non-metric maps to modern reference systems;

- Uncertainty Assessment: Documenting historical inaccuracy and positional imprecision;

- Metadata Enrichment: Linking digitized map elements with archival records and ecclesiastical registries.

3. Results

3.1. Data Collection and Processing Workflow

- Phase 1: Definition of Cartographic Scope and Thematic Focus

- Objective: Define the geographic extent and religious content to be represented (archdiocesan boundaries, deaneries, parishes, significant churches).

- Method: Literature review; consultation with ecclesiastical sources.

- Phase 2: Collection of Contemporary Spatial Data

- Objective: Acquire geospatial layers for base map construction.

- Method: Download of official geodata and crowdsourced content.

- Sources:

- Phase 3: Historical Map Processing and Georeferencing

- Objective: Digitize and georeference the 1826 historical map for temporal comparison.

- Methods:

- High-resolution scanning (500 dpi, 24-bit).

- Georeferencing in QGIS using first-order affine transformation (RMSE = 12.4 m).

- Vectorization of archdeaconries, deaneries, and ecclesiastical symbols.

- Sources:

- Phase 4: Extraction and Validation of Ecclesiastical Content

- Objective: Identify and locate current churches, sanctuaries, and deanery centers.

- Methods:

- ○

- Manual extraction of coordinates using Google Maps;

- ○

- Data verification via orthophoto overlays (DOF5);

- ○

- Consultation with pastoral offices.

- Sources:

- Phase 5: Integration, Generalization, and Symbolization

- Objective: Create a readable, thematically accurate map product.

- Methods:

- ○

- Integration of all layers in QGIS 3.28;

- ○

- Filtering of thematic content (e.g., major roads only);

- ○

- Generalization of linear and point features to match map scale (1:250,000);

- ○

- Design of thematic symbols and legend elements.

- Outcome: Finalized map suitable for both digital and print distribution.

3.1.1. Objectives and Rationale

3.1.2. Methodological Framework

3.1.3. Data Source Justification

3.1.4. Digitization Process

3.1.5. GIS Integration and Layer Logic

3.1.6. General Geographic Elements (Rivers, Roads, Settlements)

3.1.7. Visual Validation and Internal Peer Review

3.2. Comparative Reflection with Similar Case Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lovrić, P. Opća Kartografija; Sveučilišna naklada Liber: Zagreb, Croatia, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Župan, R.; Frangeš, S. Map of the Diocese of Požega (Dioecesis Posegana). J. Maps 2015, 11, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Biskupije—Hrvatska Biskupska Konferencija. Available online: https://hbk.hr/home-2-2/nad-biskupije/ (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Malić, B.; Frangeš, S. The Map of the Bosnia or Đakovo and Syrmia Diocese. Teh. Vjesn. 2019, 26, 801–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- File: Map of Roman Catholic Dioceses in Croatia.svg—Wikimedia Commons. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=150828545) (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Bodenhamer, D.J.; Corrigan, J.; Harris, T.M. (Eds.) Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Görög, D.; Lipszky, J. Mappa Dioecesium Bosnensis seu Diakovariensis et Syrmiensis; Pest, Hungarian; Museum of Slavonia: Osijek, Croatia, 1826; (inventory number P-1404). [Google Scholar]

- Peterca, M.; Milisavljević, S.; Radošević, N.; Racetin, F. Kartografija; Izdanje Vojnogeografskog Instituta (Published by the Military Geographical Institute): Belgrade, Serbia, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Barbalić, I. Granice Crkvenih Teritorijalnih Jedinica u Hrvatskoj (The Boundaries of Ecclesiastical Territorial Units in Croatia). Unpublished Seminar Thesis in Master Study, Faculty of Geodesy, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lovrić, P.; Čanković, D.; Babić, B. Prilog poznavanju Szemanove karte Zagrebačke biskupije. Geod. List 1990, 10–12, 301–314. [Google Scholar]

- Dadić, Ž. Povijest Egzaktnih Znanosti u Hrvata I/II; Sveučilišna naklada Liber: Zagreb, Croatia, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Marković, M. Descriptio Croatiae; Naprijed: Zagreb, Croatia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Moačanin, F. Prilog dataciji Szemanove karte zagrebačke županije. Arh. Vjesn. 1988, 32, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pandžić, A. Pet Stoljeća Zemljopisnih Karata Hrvatske: Izložba Povijesnog Muzeja Hrvatske; Muzej za Umjetnost i Obrt: Zagreb, Croatia, 1988; pp. 112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Lapaine, M.; Kljajić, I. Hrvatski Kartografi. Biografski Leksikon; Golden Marketing-Tehnička knjiga: Zagreb, Croatia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Senđerđi, J. Prvi zemaljski-jozefinski premjer. Geod. List 1558, XII, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Vujić, A. (Ed.) Szeman, Josip. In Hrvatski Leksikon I-II; Leksikografski Zavod: Zagreb, Croatia, 1997; p. 507. [Google Scholar]

- Magaš, D. Population and settlements of Croatia. In The Geography of Croatia; Feletar, D., Ed.; Edition: Manualia Universitatis Studiorum Jadertinae, Biblioteka Geographia Croatica: Book 46; University of Zadar, Department of Geography, Meridijani: Zadar, Samobor, Croatia, 2015; pp. 302–350. [Google Scholar]

- Karta-Kreveta_1024x717.jpg. Available online: https://djos.hr/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Karta-kreveta_1024x717.jpg (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Povijest Đakovačko-Osječke Nadbiskupije. Available online: https://djos.hr/povijest-dakovacko-osjecke-nadbiskupije/ (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Povijesni Orisi Đakovačko-Osječke Nadbiskupije i Srijemske Biskupije. Available online: https://www.vjeraidjela.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Povijesni-orisi-Đakovačko-osječke-nadbiskupije-i-Srijemske-biskupije.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Đakovačko-Osječka Nadbiskupija—Hrvatska Enciklopedija. Available online: https://www.enciklopedija.hr/clanak/djakovacko-osjecka-nadbiskupija (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- State Geodetic Administration. Registar Prostornih Jedinica Državne Geodetske Uprave; State Geodetic Administration: Zagreb, Croatia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Registar Geografskih Imena—Mrežna Stranica. Available online: https://rgi.dgu.hr/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- OpenStreetMap. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=7/44.523/16.460 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Home—DIVA-GIS. Available online: https://diva-gis.org/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Zakon o Područjima Županija, Gradova i Općina u Republici Hrvatskoj. National Gazette. 1992. Available online: http://www.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeno/1992/2333.htm (accessed on 30 December 2013).

- Zakon o Izmjenama i Dopunama Zakona o Područjima Županija, Gradova i Općina u Republici Hrvatskoj. National Gazette. 1997. Available online: http://www.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeno/1998/0815.htm (accessed on 30 December 2013).

- Zakon o Područjima Županija, Gradova i Općina u Republici Hrvatskoj. National Gazette. 1997. Available online: http://www.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeno/1997/0151.htm (accessed on 30 December 2013).

- OpenStreetMap—Wikipedia. Available online: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/OpenStreetMap (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- GEOFABRIK//Home. Available online: https://www.geofabrik.de/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Bajić, V.; Husak, M.; Kosina, S.; Savin, M. Datoteka Centroida Naselja Hrvatske (Centroid Datafile of the Settlements in Croatia). Student Work in Master Study—On the Occasion of the University Day; Faculty of Geodesy, University of Zagreb: Zagreb, Croatia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lapaine, M.; Tutić, D. New Oficial Map Projection of Croatia—HTRS96/TM. KiG Kartogr. I Geoinformacije 2007, 6, 34–53. [Google Scholar]

- Državna Geodetska Uprava—Novi Projekcijski Koordinatni Referentni Sustav Republike Hrvatske (HTRS96/TM). Available online: https://dgu.gov.hr/novi-projekcijski-koordinatni-referentni-sustav-republike-hrvatske-htrs96-tm/5245 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- GK—Glas Koncila. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20160323071009/http://www.glas-koncila.hr/portal.html?catID=5350 (accessed on 30 December 2013).

- Brkić, I. Izrada Karte Đakovačko-Osječke Nadbiskupije (Creation of a Map of the Đakovo-Osijek Archdiocese). Seminar Thesis in Master Study, Department of Cartography, Faculty of Geodesy, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia, 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Spatial without Compromise—QGIS Web Site. Available online: https://www.qgis.org/ (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Landek, I.; Pahić, D.; Bosiljevac, M.; Frangeš, S.; Marjanović, M.; Vilus, I.; Lemajić, S. Zbirka Kartografskih Znakova; Državna Geodetska Uprava: Zagreb, Croatia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ColorBrewer: Color Advice for Maps. Available online: https://colorbrewer2.org/#type=sequential&scheme=BuGn&n=3 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Gregory, I.N.; Ell, P.S. Error-sensitive historical GIS: Identifying areal interpolation errors in time-series data. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2006, 20, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, A.K.; Hillier, A. (Eds.) Placing History: How Maps, Spatial Data, and GIS Are Changing Historical Scholarship; ESRI Press: Redlands, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Máté-Tóth, A.; Hajdú, Z. The Region of Central and Eastern Europe: A Geography and Religious Studies. Focus on Religion in Central and Eastern Europe: A Regional View; (Religion and Society Book 68); Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Faričić, J. Geografija Sjevernodalmatinskih Otoka; Sveučilište u Zadru, Školska knjiga: Zagreb, Croatia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Affek, A. Georeferencing of historical maps using GIS, as exemplified by the Austrian Military Surveys of Galicia. Geogr. Pol. 2013, 86, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.D. Relations between church and state: Catholic developments in Spanish-ruled Italy of the counter-reformation. Hist. Eur. Ideas 1988, 9, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Archdeaconry | Deanery | Parish | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cathedral | Đakovo | ||

| Osijek | |||

| Kopanica | 3 | 22 | |

| Brod | Brod | 1 | 12 |

| Upper Srijem | Vinkovci | ||

| Tovarnik | 2 | 25 | |

| Lower Srijem | Mitrovica | ||

| Posavina | |||

| Petrovaradin | 3 | 22 | |

| Total | 9 | 81 | |

| Cartographic Symbol |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Deanery | Parish Church | Chapel with a Church | Chapel without a Church | Monastery | Convent | Orthodox Denomination | Greek Catholic Denomination | Lutheran Denomination | Calvinist Denomination | Synagogue |

| Layer | Source | Format | Purpose | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parish Churches | Archdiocese website | CSV/Point | Point features | 2024 |

| Administrative Boundaries | DIVA-GIS | Shapefile | Polygon deaneries | 2023 |

| Historical Deaneries | Görög & Lipszky, 1826 | Raster and digitized vector | Comparative analysis | 1826/2016 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frangeš, S.; Malić, B.; Župan, R. Religious Cartography as a Segment of Thematic Cartography: A Case Study of the Archdiocese of Đakovo–Osijek. Heritage 2025, 8, 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090356

Frangeš S, Malić B, Župan R. Religious Cartography as a Segment of Thematic Cartography: A Case Study of the Archdiocese of Đakovo–Osijek. Heritage. 2025; 8(9):356. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090356

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrangeš, Stanislav, Brankica Malić, and Robert Župan. 2025. "Religious Cartography as a Segment of Thematic Cartography: A Case Study of the Archdiocese of Đakovo–Osijek" Heritage 8, no. 9: 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090356

APA StyleFrangeš, S., Malić, B., & Župan, R. (2025). Religious Cartography as a Segment of Thematic Cartography: A Case Study of the Archdiocese of Đakovo–Osijek. Heritage, 8(9), 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090356