Empty Shelves: Tracking the Flow of Goods During Ancient Climate Crises in Central Anatolia

Abstract

1. Introduction

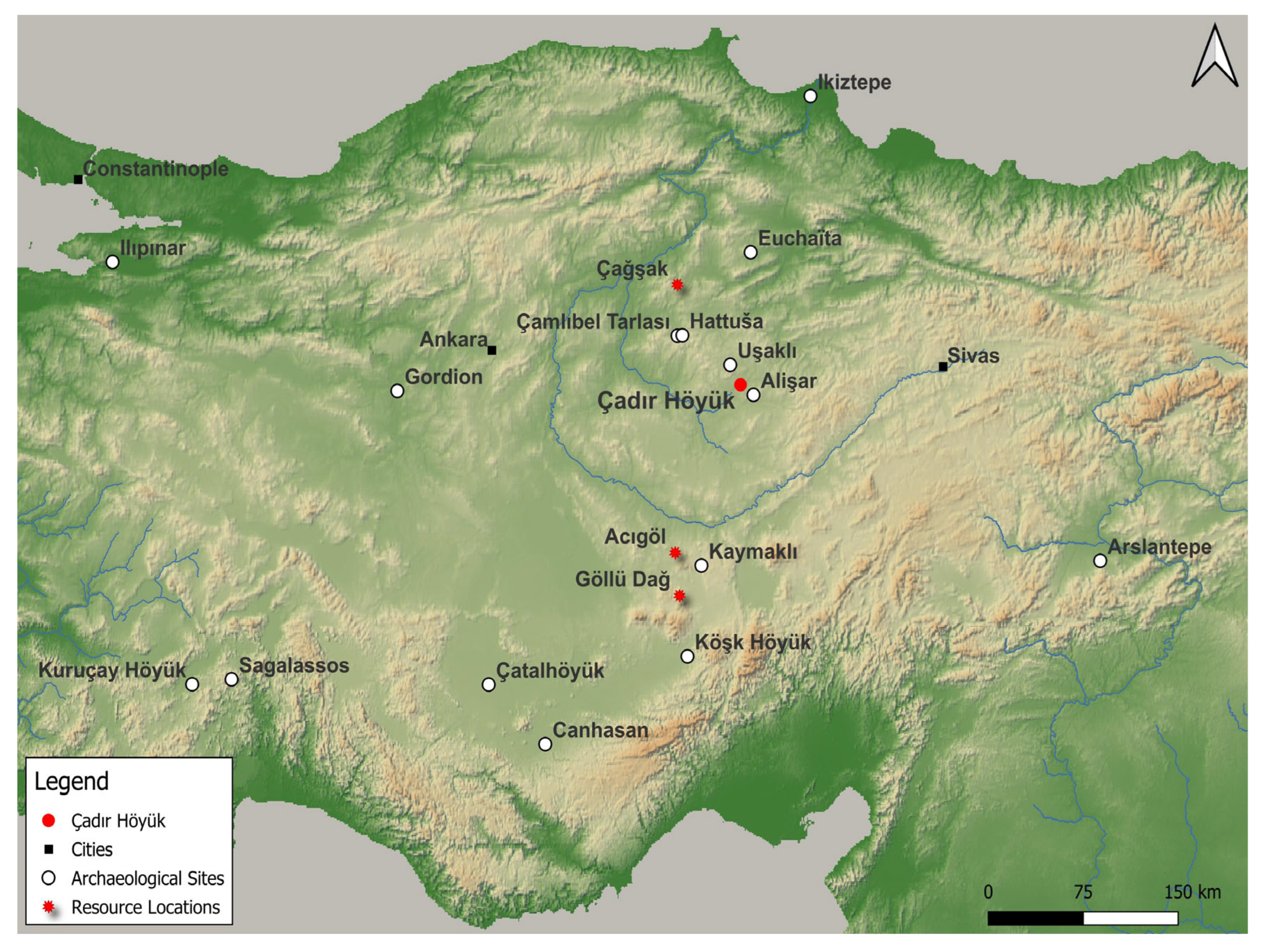

2. Climate Events and Subsistence Adjustments at Ancient Çadır Höyük

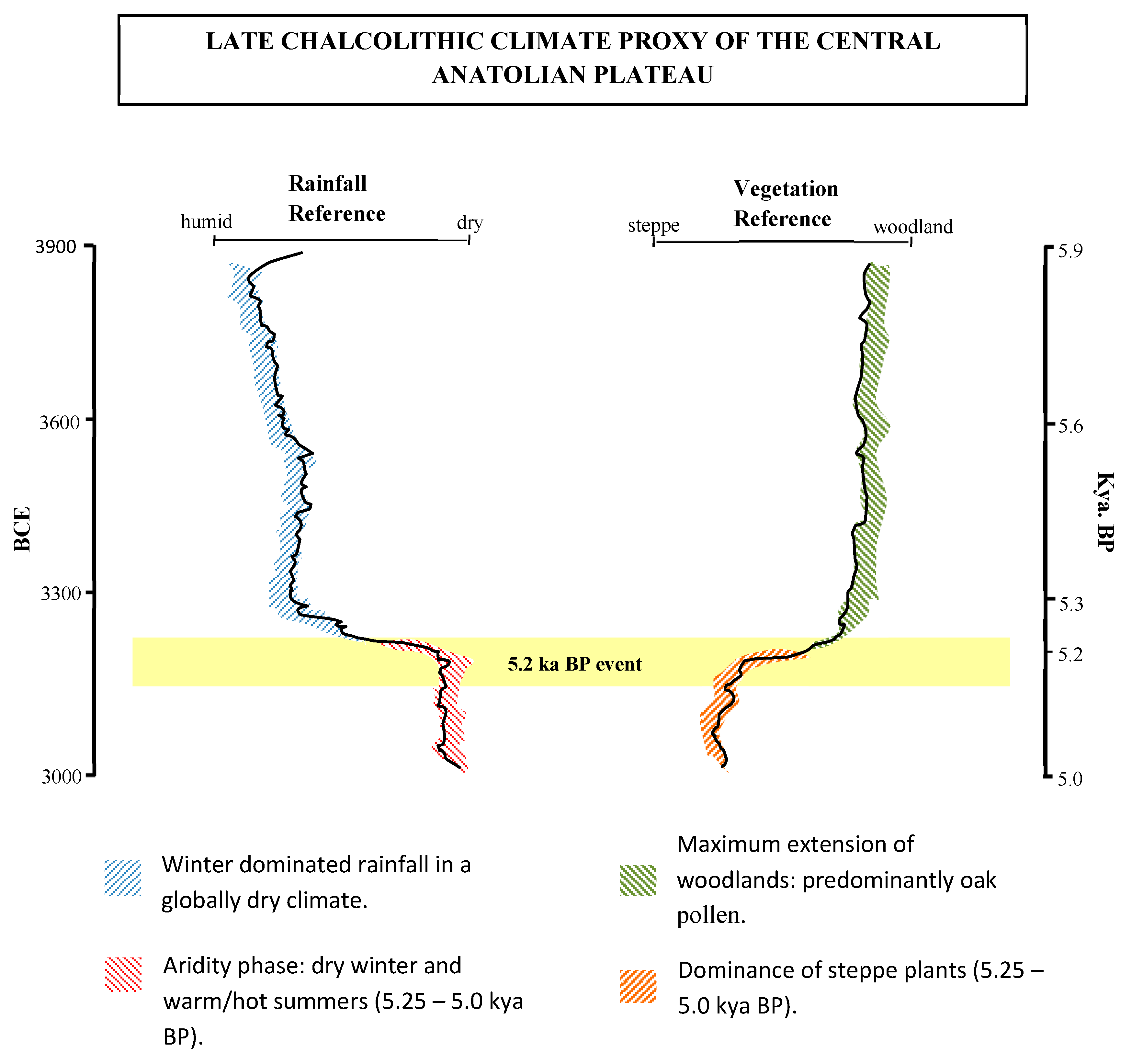

2.1. The 5.2 ka Climate Event

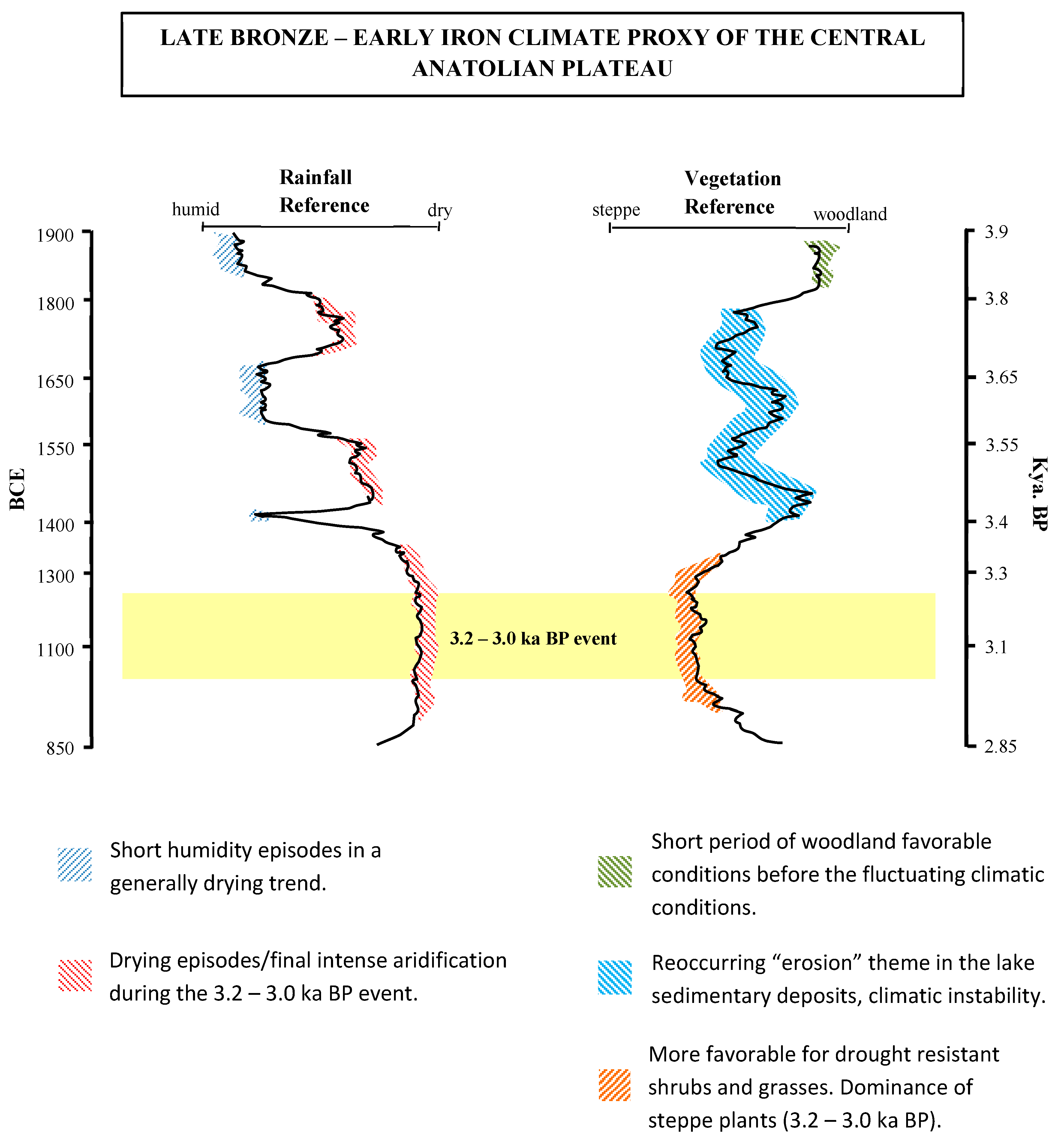

2.2. The 3.2 ka Event

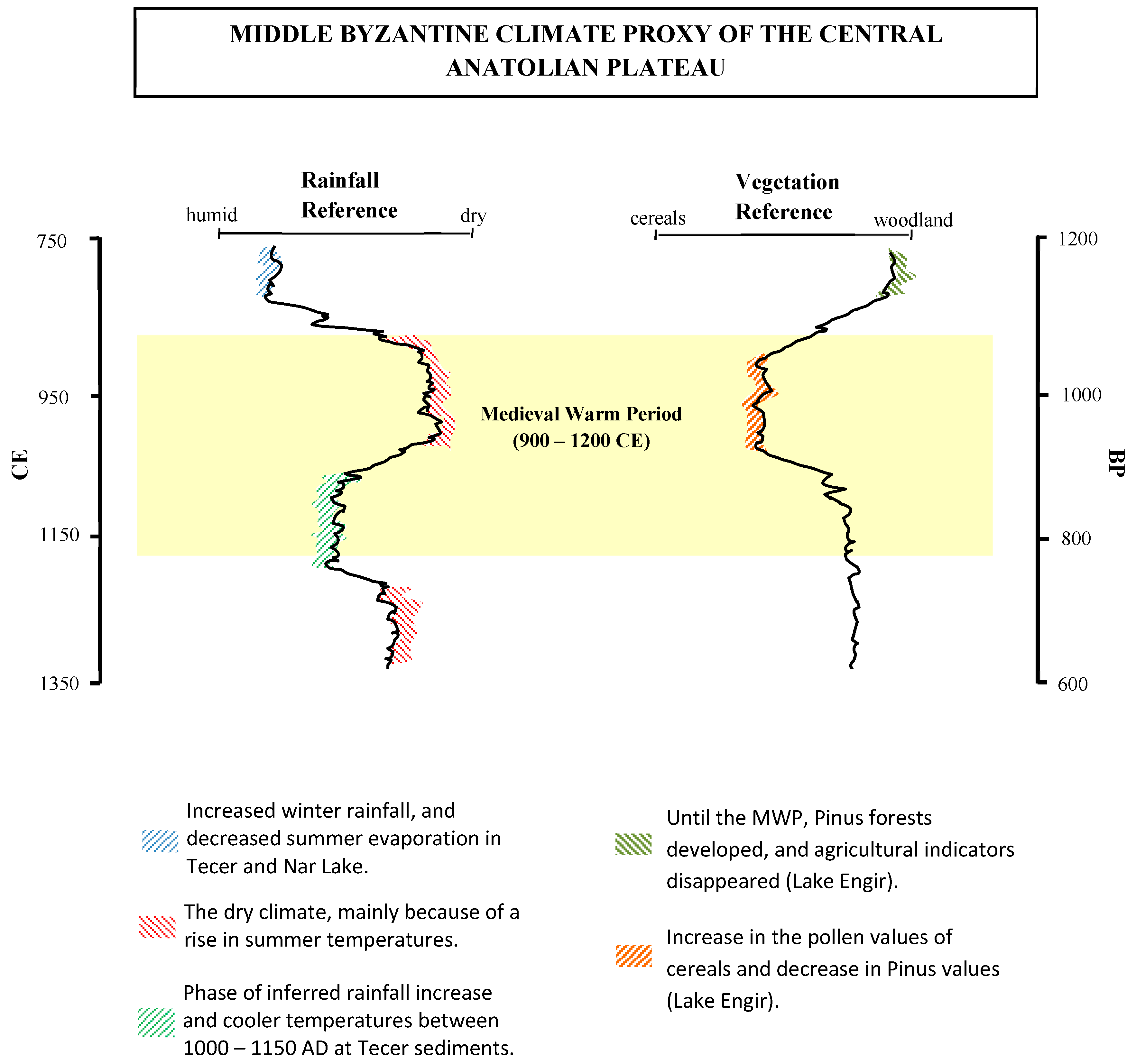

2.3. The Medieval Warm Period

2.4. Summary

3. The 4th Millennium Late Chalcolithic

3.1. Occupational Phases: Description

3.2. Trade During the Late Chalcolithic 5.2 ka Event

3.3. Lithics

3.4. Metals

3.5. Textiles

3.6. Summary

4. The Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age

4.1. Occupational Phases: Description

4.2. Trade in the Age of the 3.2 ka Event

4.3. Summary

5. The Late Roman and Medieval Period

5.1. Contextualizing the Late Roman and Medieval Period on the Plateau

5.2. The Late Roman and Byzantine Era at Çadır Höyük

5.3. Summary

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eastwood, W.J.; Leng, M.J.; Roberts, N.; Davis, B. Holocene Climate Change in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Comparison of Stable Isotope and Pollen Data from Lake Gölhisar, Southwest Turkey. J. Quat. Sci. 2007, 22, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontugne, M.; Kuzucuoğlu, C.; Karabiyikoğlu, M.; Hatté, C.; Pastre, J.-F. From Peniglacial to Holocene: A 14C Chronostratigraphy of Environmental Changes in the Konya Plain, Turkey. Quat. Sci. Rev. 1999, 18, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.; Brayshaw, D.; Kuzucuoğlu, C.; Perez, R.; Sadori, L. The Mid-Holocene Climatic Transition in the Mediterranean: Causes and Consequences. Holocene 2011, 21, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Matthews, M.; Ayalon, A. Mid-Holocene Climate Variations Revealed by High-Resolution Speleothem Records from Soreq Cave, Israel, and Their Correlation with Cultural Changes. Holocene 2011, 21, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.; Brooks, N.; Banning, E.B.; Bar-Matthews, M.; Campbell, S.; Clare, L.; Cremaschi, M.; di Lernia, S.; Drake, N.; Gallinaro, M.; et al. Climatic Changes and Social Transformations in the Near East and North Africa During the ‘Long’ 4th Millennium BC: A Comparative Study of Environmental and Archaeological Evidence. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 136, 96–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giamali, C.; Koskeridou, E.; Antonarakou, A.; Ioakim, C.; Kontakiotis, G.; Karageorgis, A.P.; Roussakis, G.; Karakitsios, V. Multiproxy Ecosystem Responses of Abrupt Holocene Climatic Changes in the Northeastern Mediterranean Sedimentary Archive and Hydrologic Regime. Quat. Res. 2019, 92, 665–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miebach, A.; Niestrath, P.; Roeser, P.; Litt, T. Impacts of Climate and Humans on the Vegetation in Northwestern Turkey: Palynological Insights from Lake Iznik since the Last Glacial. Clim. Past. 2016, 12, 575–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Baeyer, M.; Şerifoğlu, T.E. Stability through Crisis: Cultural Resilience in the Face of Climatic Fluctuation from 3500 to 1300 CE at Çadır Höyük. In Winds of Change: Environment and Society in Anatolia; Roosevelt, C.H., Haldon, J., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021; pp. 85–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bini, M.; Zanchetta, G.; Perşolu, A.; Cartier, R.; Català, A.; Cacho, I.; Dean, J.R.; Di Rita, F.; Drysdale, R.N.; Finnè, M.; et al. The 4.2 ka BP Event in the Mediterranean Region: An Overview. Clim. Past. 2019, 15, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finné, M.; Holmgren, K.; Sundquist, H.S.; Weiberg, E.; Lindblom, M. Climate in the Eastern Mediterranean, and Adjacent Regions, During the Past 6000 Years—A Review. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2011, 38, 3153–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finné, M.; Woodbridge, J.; Labuhn, I.; Roberts, C.N. Holocene Hydro-Climatic Variability in the Mediterranean: A Synthetic Multi-Proxy Reconstruction. Holocene 2019, 29, 847–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, M.; Chen, L. The 4.2 ka BP Climatic Event and its Cultural Responses. Quarternary Int. 2019, 521, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniewski, D.; Van Campo, E.; Guiot, J.; Le Burel, S.; Otto, T.; Bateman, C. Environmental Roots of the Late Bronze Age Crisis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniewski, D.; Marriner, N.; Bretschneider, J.; Jans, G.; Morhange, C.; Cheddadi, R.; Otto, T.; Luce, F.; Van Campo, E. 300-Year Drought Frames Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age Transition in the Near East: New Palaeoecological Data from Cyprus and Syria. Reg. Environ. Change 2019, 19, 2287–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkova, M.A.; Kashuba, M.T.; Agulnicov, S.; Kulkov, A.; Streitsov, M.A.; Vetrova, M.; Zanoci, A. Impact of Paleoclimatic Changes on the Cultural and Historical Processes at the Turn of the Late Bronze–Early Iron Ages in the Northern Black Sea Region. Heritage 2022, 5, 2258–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, S.W.; Kocik, C.; Lorentzen, B.; Sparks, J.P. Severe Multi-Year Drought Coincident with Hittite Collapse Around 1198–1196 BC. Nature 2023, 614, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N. Boon or Curse? The Role of Climate Change in the Rise and Demise of Anatolian Civilizations. In Winds of Change: Environment and Society in Anatolia (15th International ANAMED Annual Symposium); Roosevelt, C.H., Haldon, J., Eds.; Koç University Press: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2021; pp. 5–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ellenblum, R. The Collapse of the Eastern Mediterranean: Climate Change and the Decline of the East, 950–1072; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haldon, J.; Eastwood, W.; Roberts, N.; Izdebski, A.; Fleitmann, D.; McCormick, M.; Cassis, M.; Doonan, O.; Elton, H.; Ladstätter, S.; et al. The Climate and Environment of Byzantine Anatolia: Integrating Science, History and Archaeology. J. Interdiscip. Hist. 2014, 45, 113–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüning, S.; Schulte, L.; Garcés-Pastor, S.; Danladi, I.B.; Galka, M. The Medieval Climate Anomaly in the Mediterranean Region. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatology 2019, 34, 1625–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, S.R.; Selover, S.; Ross, J.C.; Dinç, E.; Lauricella, A.J.; Hackley, L.D.; Yıldırım, B.; Erdem, D. Rural Farmers, Climate Change, and Continued Archaeological Work at Çadır Höyük (2023–2024). Anatolica 2025, 51, 49–84. [Google Scholar]

- von Baeyer, M.; Smith, A.; Steadman, S.R. Expanding the Plain: Using Archaeobotany to Examine Adaptation to 5.2 ka Climate Change Event During the Anatolian Late Chalcolithic at Çadır Höyük. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021, 36, 102806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Baeyer, M.; Steadman, S.R.; Arbuckle, B.S. Rural Fortitude at Çadır Höyük: Tracing Recovery after the 5.9 and 5.2 ka Climate Events on the Anatolian Plateau. In Tracing Transitions and Connecting Communities in the Archaeology of Western Asia: Papers Presented to Roger Matthews at the Occasion of His 70th Birthday; Glatz, C., Fernández, M.P., Richardson, A., Saymour, M., Eds.; Sidestone Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cassis, M.; Lauricella, A.J.; Tardio, K.; von Baeyer, M.; Coleman, S.; Adcock, S.E.; Arbuckle, B.S.; Smith, A. Regional Patterns of Transition at Çadır Höyük in the Byzantine Period. J. East. Mediterr. Archaeol. Herit. Stud. 2019, 7, 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, S.R.; Arbuckle, B.S.; McMahon, G. Pivoting East: Çadır Höyük, Transcaucasia, and Complex Connectivity in the Late Chalcolithic. Doc. Praehist. 2018, 45, 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ross, J.C.; McMahon, G.; Heffron, Y.; Adcock, S.E.; Steadman, S.R.; Arbuckle, B.S.; Smith, A.; von Baeyer, M. Anatolian Empires: Local Experiences from Hittites to Phrygians at Çadır Höyük. J. East. Mediterr. Archaeol. Herit. Stud. 2019, 7, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, S.R.; McMahon, G.; Ross, J.C. Chalcolithic, Iron Age, and Byzantine Investigations at Çadır Höyük: The 2017 and 2018 Seasons. In The Archaeology of Anatolia, Volume III: Recent Discoveries (2017–2018); Steadman, S.R., McMahon, G., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Press: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2019; pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; von Lampe, M.; van Tongeren, F. Climate Change and Trade in Agriculture. Food Policy 2011, 36 (Suppl. 1), S9–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Martínez, A.; Esteve-Pérez, S.; Gil-Pareja, S.; Llorca-Vivero, R. The Impact of Climate Change on International Trade: A Gravity Model Estimation. World Econ. 2023, 46, 2624–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northey, S.A.; Mudd, G.M.; Werner, T.T.; Jowitt, S.M.; Haque, S.; Yellishetty, M.; Weng, Z. The Exposure of Global Base Metal Resources to Water Criticality, Scarcity and Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Change 2017, 44, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocakoğlu, F.; Çilingiroğlu, Ç.; Potoğlu Erkara, I.; Ünan, S.; Dinçer, B.; Akkiraz, M.S. Human-Climate Interactions Since the Neolithic Period in Central Anatolia: Novel Multi-Proxy Data from the Kureyşler area, Kütahya, Turkey. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2019, 213, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şenkul, Ç.; Memiş, T.; Eastwood, W.J.; Doğan, U. Mid-to Late-Holocene Paleovegetation Change in Vicinity of Lake Tuzla (Kayseri), Central Anatolia, Turkey. Quarternary Int. 2018, 486, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayewski, P.A.; Rohling, E.E.; Stager, J.C.; Karlén, W.; Maasch, K.A.; Meeker, L.D.; Meyerson, E.A.; Gasse, F.; van Kreveld, S.; Holmgren, K.; et al. Holocene Climate Variability. Quat. Res. 2004, 62, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzucuoğlu, C.; Dörfler, W.; Kunesch, S.; Goupille, F. Mid-to-Late Holocene Climate Change in Central Turkey: The Tecer Lake Record. Holocene 2011, 21, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ön, Z.B.; Akçer-Ön, S.; Özeren, M.S.; Eriş, K.K.; Greaves, A.M.; Çağatay, M.N. Climate Proxies for the Last 17.3 ka from Lake Hazar (Eastern Anatolia), Extracted by Independent Component Analysis of µ-XRF Data. Quarternary Int. 2018, 486, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodbridge, J.; Roberts, C.N.; Palmisano, A.; Bevan, A.; Shennan, S.; Fyfe, R.; Eastwood, W.J.; Labuhn, I. Pollen-inferred Regional Vegetation Patterns and Demographic Change in Southern Anatolia Through the Holocene. Holocene 2019, 29, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arıkan, B. Modeling the Paleoclimate (ca. 6000–3200 cal BP) in Eastern Anatolia: The Method of Macrophysical Climate Model and Comparisons with Proxy Data. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015, 5, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcock, S.L. Long-term Socio-environmental Dynamics and Adaptive Cycles in Cappadocia, Turkey During the Holocene. Quarternary Int. 2017, 446, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaniewski, D.; Guiot, J.; Van Campo, E. Drought and Societal Collapse 3200 Years Ago in the Eastern Mediterranean: A Review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2015, 6, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzucuoğlu, C. The Rise and Fall of the Hittite State in Central Anatolia: How, When, Where, Did Climate Intervene? In La Cappadoce Méridionale de la Préhistoire à l’époque Byzantine; Tibet, A., Henry, O., Beyer, D., Eds.; Institut Français D’études Anatoliennes: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2012; pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xoplaki, E.; Fleitmann, D.; Luterbacher, J.; Wagner, S.; Haldon, J.F.; Zarita, E.; Telelis, I.; Toreti, A.; Izdebski, A. The Medieval Climate Anomaly and Byzantium: A Review of the Evidence on Climatic Fluctuations, Economic Performance and Societal Change. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 136, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, A.; Eastwood, W.J.; Roberts, C.N.; John, F.; Haldon, J.F.; Turner, R. Historical Landscape Change in Cappadocia (Central Turkey): A Palaeoecological Investigation of Annually-Laminated Sediments from Nar Lake. Holocene 2008, 18, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, B. Chalcolithic Caprines, Dark Age Dairy, and Byzantine Beef: A First Look at Animal Exploitation at Middle and Late Holocene Çadır Höyük, North Central Turkey. Anatolica 2009, 35, 179–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, B. Animals and Inequality in Chalcolithic Central Anatolia. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2012, 31, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernoff, M.C.; Harnischfeger, T.M. Preliminary Report on Botanical Remains from Çadır Höyük (1994 Season). Anatolica 1996, 22, 159–175. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. Plant Use at Çadır Höyük, Central Anatolia. Anatolica 2007, 33, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardio, K.S.; Adcock, S.E.; Arbuckle, B. Corralled Cattle: Faunal Remains from the Late Roman and Byzantine Phases of Çadır Höyük, Turkey. In Archaeozoology of Southwest Asia and Adjacent Areas XIV; Alcantara, R., Saña Segui, M., Tomero, C., Eds.; BAR International Series: Oxford, UK, 2024; pp. 235–252. [Google Scholar]

- Adcock, S.E. Collapse, Complexity, and Caprines: Zooarchaeological Investigations of the Hittite State and its Afters. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2022, 68, 101465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, S.R.; Ross, J.C.; Baumgartner, R.; Martinez, J.; Arbuckle, B.S.; Stoj, K.; McMahon, G.; Smith, A.; von Baeyer, M.; Schack, F. Learning from the Past: Managing Climate Change in the Fourth and Second Millennia BCE at Çadır Höyük. In Studies in Honour of Prof. Dr. Ayşe Tuba Ökse; Engin, A., Aykurt, A., Türkcan, A.U., Zimmermann, T., Yaşin Meier, D., Gedik Zimmermann, S., Can, Ş., Çiftçi, Ş., Ekinbaş Can, Ö., Kekeç, E., Eds.; Ege Yayınları: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, S.R.; Ross, J.C.; McMahon, G.; Gorny, R.L. Excavations on the North-Central Plateau: The Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age Occupation at Çadır Höyük. Anatol. Stud. 2008, 58, 47–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, S.R.; McMahon, G.; Arbuckle, B.S.; von Baeyer, M.; Smith, A.; Yıldırım, B.; Hackley, L.D.; Selover, S.; Spagni, S. Stability and Change at Çadır Höyük in Central Anatolia: A Case of Late Chalcolithic Globalisation? Anatol. Stud. 2019, 69, 21–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, S.R.; Hackley, L.D.; Selover, S.; Yıldırım, B.; von Baeyer, M.; Arbuckle, B.; Robinson, R.; Smith, A. Early Lives: The Late Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age at Çadır Höyük. J. East. Mediterr. Archaeol. Herit. Stud. 2019, 7, 271–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, S.R.; McMahon, G. The 2015–2016 Seasons at Çadır Höyük on the North Central Anatolian Plateau. In The Archaeology of Anatolia, Volume II: Recent Discoveries (2015–2016); Steadman, S.R., McMahon, G., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Press: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2017; pp. 94–116. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, S.R.; McMahon, G.; Ross, J.C.; Cassis, M.; Geyer, J.D.; Arbuckle, B.; von Baeyer, M. The 2009 and 2012 Seasons of Excavation at Çadır Höyük on the Anatolian North Central Plateau. Anatolica 2013, 39, 113–167. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman, S.R.; McMahon, G.; Ross, J.C. The Late Chalcolithic at Çadır Höyük in Central Anatolia. J. Field Archaeol. 2007, 32, 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selover, S.; Hackley, L.D.; Steadman, S.R. ‘Work/Life Balance’ in Late Chalcolithic Anatolia: Household Activities and Spatial Organization at Çadır Höyük. In No Place Like Home: Ancient Near Eastern Houses and Households; Battini, L., Brody, A., Steadman, S.R., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 112–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hackley, L.D.; Yıldırım, B.; Steadman, S.R. Not Seeing is Believing: Ritual Practice and Architecture at Chalcolithic Çadır Höyük, Anatolia. Religions 2021, 12, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, B.; Hackley, L.D.; Steadman, S.R. Sanctifying the House: Child Burial in Prehistoric Anatolia. Near East. Archaeol. 2018, 81, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, S.R.; Şerifoğlu, T.E.; Selover, S.; Hackley, L.D.; Yıldırım, B.; Lauricella, A.J.; Arbuckle, B.S.; Adcock, S.E.; Tardio, K.; Dinç, E.; et al. Recent Discoveries (2015–2016) at Çadır Höyük on the Anatolian North Central Plateau. Anatolica 2017, 43, 203–250. [Google Scholar]

- Massa, M. Networks Before Empires: Cultural Transfers in West and Central Anatolia During the Early Bronze Age. Ph.D. Dissertation, Institute of Archaeology, University College London, London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Branting, S.A. The Alişar Regional Survey 1993–1994: A Preliminary Report. Anatolica 1996, 22, 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sagona, A. Wagons and Carts of the Trans-Caucasus. In Essays in Honour of M. Taner Tarha; Tekin, O., Sayar, M.H., Konyar, E., Eds.; Ege Yayınları: İstanbul, Türkiye, 2013; pp. 277–298. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle, B.; (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA). Personal Communication, 2025.

- Bașıbüyük, Z. Mineralogical, Geochemical, and Gemological Characteristics of Silicic Gemstone in Aydıncık (Yozgat-Turkey). Arab. J. Geosci. 2018, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öksüz, N. Geochemical Characteristics of the Eymir (Sorgun-Yozgat) Manganese Deposit, Turkey. J. Rare Earths 2011, 29, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öksüz, N.; Okuyucu, N. Mineralogy, Geochemistry, and Origin of Buyukmahal Manganese Mineralization in the Artova Ophiolitic Complex, Yozgat, Turkey. J. Chem. 2014, 2014, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, S.; Carter, T.; Geyer, J. Obsidian Sourcing at Chalcolithic–Bronze Age Çadır Höyük (Central Anatolia). In Proceedings of the Poster presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, San Antonio, TX, USA, 23 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Massa, M.; McIlfatrick, O.; Fidan, E. Patterns of Metal Procurement, Manufacture and Exchange in Early Bronze Age Northwestern Anatolia: Demircihüyük and Beyond. Anatol. Stud. 2017, 67, 51–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.H.; Stos-Gale, S.A.; Gilmore, G. Alloy Types and Copper Sources of Anatolian Copper Alloy Artifacts. Anatol. Stud. 1985, 35, 143–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, J.W.; Yener, K.A. Organization and Specialization of Early Mining and Metal Technologies in Anatolia. In Archaeometallurgy in Global Perspective; Roberts, B.W., Thornton, C.P., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 529–557. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, D.L.; Kuijpers, E.P. Stratiform Copper Deposit, Northern Anatolia, Turkey: Evidence for Early Bronze I (2800 B.C.) Mining Activity. Science 1974, 186, 823–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaptan, E. Findings Related to the History of Mining in Turkey. Bull. Miner. Res. Explor. 1990, 111, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Yalçin, Ü.; Maass, A. Prähistorische Kupfergewinnung in Derekutuğun, Anatolien. In Anatolian Metal VI. Der Anschnitt, Zeitschrift für Kunst und Kultur im Bergbau; Yalçin, Ü., Ed.; Deutsches Bergbau-Museum: Bochum, Germany, 2013; pp. 153–194. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, G.A.; Öztunalı, Ö. Prehistoric Copper Sources in Turkey. In Anatolian Metal I. Der Anschnitt, Zeitschrift für Kunst und Kultur im Bergbau; Yalçin, Ü., Ed.; Deutsches Bergbau-Museum: Bochum, Germany, 2000; pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Yalçin, Ü.; Yalçin, H.G. The Prehistoric Mining Kindlings from Derekutuğun. SDÜ Fen-Edeb. Fakültesi Sos. Bilim. Dergisi. 2019, 47, 116–129. [Google Scholar]

- Schoop, U.-D. Çamlıbel Tarlası: Late Chalcolithic Settlement and Economy in the Budaközzü Valley (North-Central Anatolia). In The Archaeology of Anatolia: Recent Discoveries (2011–2014), Volume I; Steadman, S.R., McMahon, G., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 2015; pp. 46–68. [Google Scholar]

- Schoop, U.-D. Çamlıbel Tarlası, ein metallverarbeitender Fundplatz des vierten Jahrtausends v. Chr. im nördlichen Zentralanatolien. In Anatolian Metal V; Yalçın, Ü., Ed.; Deutsches Bergbau Museum: Bochum, Germany, 2011; pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, B. Geoarchaeology of the Human Landscape at Boğazköy-Ḫattuša. Archäologischer Anz. 2010, 6, 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Rehren, T.; Radivojević, M. A Preliminary Report on the Slag Samples from Çamlıbel Tarlası. Archäologischer Anz. 2010, 2010, 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Stroud, E.; Bogaard, A.; Charles, M. A Stable Isotope and Functional Weed Ecology Investigation into Chalcolithic Cultivation Practices in Central Anatolia: Çatalhöyük, Çamlıbel Tarlası and Kuruçay. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021, 38, 103010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.C.; Steadman, S.R.; McMahon, G.; Adcock, S.E.; Cannon, J.W. When the Giant Falls: Endurance and Adaptation at Çadır Höyük in the Context of the Hittite Empire and Its Collapse. J. Field Archaeol. 2019, 44, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.C. Çadır Höyük: The Upper South Slope 2006–2009. Anatolia 2010, 36, 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, A.; Orsi, V. Preliminary Report on the 2018 Excavation Season at Uşaklı Höyük (Yozgat). Kazı Sonuçları Toplantısı 2020, 41, 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni, S.; D’Agostino, A.; Orsi, V. Exploring a Site in the North Central Anatolian Plateau: Archaeological Research at Ușaklı Höyük (2013–2015). Asia Anteriore Antica 2019, 1, 57–142. [Google Scholar]

- von der Osten, H.H. The Alishar Hüyük Seasons of 1930–32. Part I–III (OIP 28–30); University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1937. [Google Scholar]

- Gorny, R.L. The 2002-2005 Excavation Seasons at Çadır Höyük. The Second Millennium Settlements. Anatolica 2006, 32, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.C.; Steadman, S.R. The Middle to Late Bronze Age Transition at Çadır Höyük: Dis/Continuity. In Proceedings of the American Schools of Overseas Research, Boston, MA, USA, 22 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarosano, M. Hittite Local Cults; SBL Press: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Košak, S. Hittite Inventory Texts (CTH 241–250); Carl Winter: Heidelberg, Germany, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Siegelová, J. Hethitische Verwaltungspraxis im Lichte der Wirtschafts- und Inventardokumente; Praha, Národní Muzeum v Praze: Praha, Czech Republic, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, J.W. Painted Ceramic Traditions and Rural Communities in Hittite Anatolia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Beran, T. Die Hethitische Glyptik von Boğazköy; Gebr. Mann Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Seeher, J. After the Empire: Observations on the Early Iron Age in Central Anatolia. In Ipamati Kistmati Pari Tumatimis: Luwian and Hittite Studies Presented to J. David Hawkins on the Occasion of His 70th Birthday; Singer, I., Ed.; Tel Aviv University: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2010; pp. 220–229. [Google Scholar]

- Orsi, V. The Transition from the Bronze to the Iron Age at Uşaklı Höyük: The Ceramic Sequence. In Anatolia Between the 13th and the 12th Century BCE; de Martino, S., Devecchi, E., Eds.; LoGisma Editore: Vicchio, Italy, 2020; pp. 273–316. [Google Scholar]

- Kealhofer, L.; Grave, P.; Marsh, B. In Search of Tabal, Central Anatolia: Iron Age Interaction at Alişar Höyük. Anatol. Stud. 2023, 73, 69–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kealhofer, L.; Grave, P.; Marsh, B.; Steadman, S.; Gorny, R.L.; Summers, G.D. Patterns of Iron Age Interaction in Central Anatolia: Three Sites in Yozgat Province. Anatol. Stud. 2010, 60, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belke, K. Roads and Routes in Northwestern and Adjoining Parts of Central Asia Minor: From the Romans to Byzantium, with Some Remarks on their Fate during the Ottoman Period up to the 17th Century. Gephyra 2020, 20, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, D. Roman Roads and Milestones of Asia Minor; Milestones, Fasc. 3.2. Galatia; British Institute at Ankara: Ankara, Türkiye, 2012; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, T. An Overview of Land Routes in Byzantine Anatolia (ca. 4th–7th c. CE). Lycus Derg. 2023, 8, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procopius. On Buildings; Dewing, H.B.; Downey, G., Translators; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Haldon, J. The De Thematibus (‘On the Themes’) of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus: Translated with Introductory Chapters and Notes; Liverpool University Press: Liverpool, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Haldon, J. Warfare, State and Society in the Byzantine World 550–1204; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, G. Maurice’s Strategikon: Handbook of Byzantine Military Strategy; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Summers, G.D. Keykavus Kale and Associated Remains on the Kerkenes Dağ in Cappadocia, Central Turkey. Anatolia Antiq. 2001, 9, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldon, J. Roads and Communications in Byzantine Asia Minor: Wagons, Horses, Supplies. In The Logistics of the Crusades; Pryor, J.H., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 131–158. [Google Scholar]

- Haldon, J. A Critical Commentary on the Taktika of Leo VI; Dumbarton Oaks: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Neville, L.A. Authority in Byzantine Provincial Society, 950–1100; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yüksel, Ç.C. Trade and Urban Development in Seljuk Anatolia. J. Art. Des. 2022, 10, 60–73. [Google Scholar]

- Şenyurt, H.K. Sarıkaya Roma Hamamı Tarihçesi ve 2010–2015 Yılı Kazı Çalışmaları Sonuçları, (The History of the Sarıkaya Roman Bath and Results of the 2010–2015 Excavations) Sarıkaya I; Uluslararası Bozok Sempozyumu Bildiri: Yozgat, Türkiye, 2020; pp. 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, S. Early Byzantine Housing. In Secular Buildings and the Archaeology of Everyday Life in the Byzantine Empire; Dark, K.R., Ed.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, C.L. Women of Byzantium; Yale University Press: New Haven, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Whitby, M.; Price, R. Theodore of Sykeon: The “Life” by George and the “Encomium” by Nicephorus; Liverpool University Press: Liverpool, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tatbul, M.N.; Erciyas, D.B. The Potential of Quantified Surface Data in Understanding the Rural Landscapes of Middle Byzantine Komana. J. East. Mediterr. Archaeol. Herit. Stud. 2023, 11, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, G. Three Byzantine Military Treatises; Dumbarton Oaks: Washington, DC, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Beihammer, A. Byzantium and the Emergence of Muslim-Turkish Anatolia, ca. 1040–1130; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vryonis, S. The Decline of Medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor: And the Process of Islamization from the Eleventh through the Fifteenth Century; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Canby, S.R.; Beyazit, D.; Rugiadi, M.; Peacock, A.C.S. Court and Cosmos. The Great Age of the Seljuqs; Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Haldon, J. Euchaïta: From Late Roman and Byzantine Town to Ottoman Village. In Archaeology and Urban Settlement in Late Roman and Byzantine Anatolia: Euchaïta and its Environment; Haldon, J., Elton, H., Newhard, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 210–254. [Google Scholar]

| Climate Event | Calendar Date | Archaeological Period in Anatolia |

|---|---|---|

| 5.9 ka | 3900 BCE | Late Chalcolithic [1,2,3] |

| 5.2 ka | 3200 BCE | Late Chalcolithic [3,4,5] |

| 4.8 ka | 2800 BCE | Early Bronze 1 [6,7,8] |

| 4.2 ka | 2200 BCE | Early Bronze 3 [9,10,11,12] |

| 3.2 ka | 1200 BCE | Late Bronze Age [13,14,15,16,17] |

| Medieval Warm Period | 900-1200 CE | Middle Byzantine [18,19,20] |

| Phase | Subphase | Tentative Dates | Climate Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase III (“BH”) | BH 3 | ca. 3600–3300 BCE | Climatic Stability (Humid Intermission) |

| Phase III (“BH”) | BH 2 | ca. 3300–3200 BCE | Climatic Stability/Variability (Humid Intermission & Lead Up) |

| Phase III (“BH”) | BH 1 | ca. 3200 BCE | Onset of 5.2 ka event |

| Phase II Transitional | Tr 3–1 | ca. 3200–3000 BCE | During/After 5.2 ka |

| Phase I Early Bronze (“EB”) | EB 3–1 | ca. 3000–2800 BCE | After 5.2 ka (Recovery Period) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Steadman, S.R.; Ross, J.C.; Cassis, M.; Lauricella, A.J.; Dinç, E.; Hackley, L.D. Empty Shelves: Tracking the Flow of Goods During Ancient Climate Crises in Central Anatolia. Heritage 2025, 8, 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090354

Steadman SR, Ross JC, Cassis M, Lauricella AJ, Dinç E, Hackley LD. Empty Shelves: Tracking the Flow of Goods During Ancient Climate Crises in Central Anatolia. Heritage. 2025; 8(9):354. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090354

Chicago/Turabian StyleSteadman, Sharon R., Jennifer C. Ross, Marica Cassis, Anthony J. Lauricella, Emrah Dinç, and Laurel D. Hackley. 2025. "Empty Shelves: Tracking the Flow of Goods During Ancient Climate Crises in Central Anatolia" Heritage 8, no. 9: 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090354

APA StyleSteadman, S. R., Ross, J. C., Cassis, M., Lauricella, A. J., Dinç, E., & Hackley, L. D. (2025). Empty Shelves: Tracking the Flow of Goods During Ancient Climate Crises in Central Anatolia. Heritage, 8(9), 354. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8090354