2. The Conference in Copenhagen

The 42nd Dyes in History and Archaeology conference was held in Copenhagen, Denmark, the second to be held in Scandinavia, from 31 October to 2 November 2023, followed by a day of visits on 3 November. Our hosts were the Centre for Textile Research (CTR), University of Copenhagen, in collaboration with the National Museum of Denmark, the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek and the Royal Danish Academy, Institute of Conservation. The conference itself took place across two centres, the Royal Danish Academy and the Centre for Textile Research, based in the University of Copenhagen. This, together with the reception at the Institute of Conservation (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2), part of the Royal Danish Academy but a short distance away by foot or on one of the harbour buses, enabled delegates to see much of the city and the harbour area very easily. The sights they may have seen as they moved between different venues are reflected in the illustrations in this Editorial.

Following the conference, delegates visiting the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek had the luxury of being guided through the polychromy of Roman encaustic paintings, while those visiting the National Museum of Denmark looked even further into the past at an archaeological textile, now discoloured, but still showing the ancient, checked pattern. Visits to Rosenborg Castle (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), built in the seventeenth century by King Christian IV, and the David Collection, with its collections of Islamic art, porcelain, and Danish Golden Age paintings, represented more recent history, but all had some links with papers presented during the conference itself.

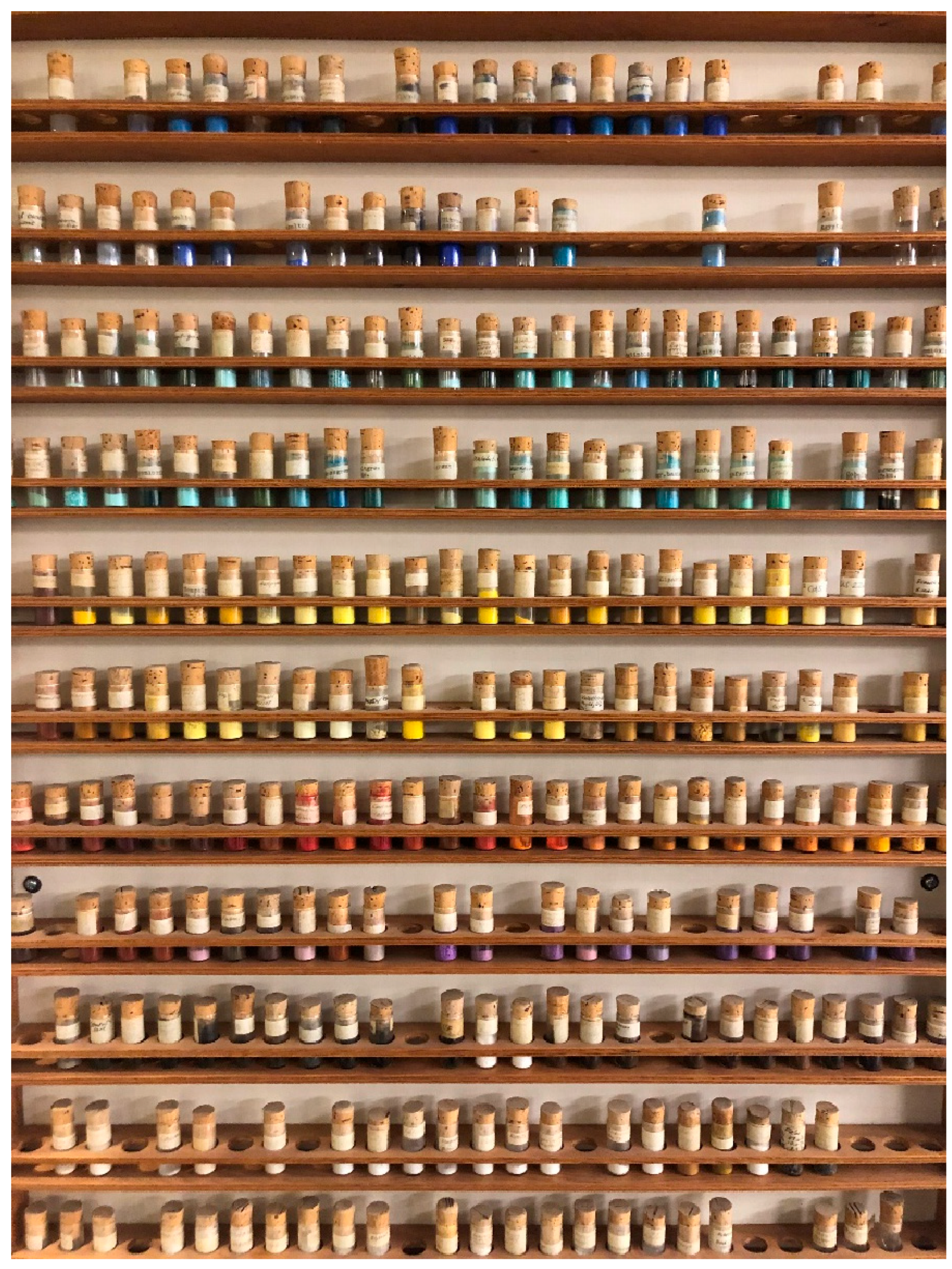

The subjects discussed during the conference included tapestries and waistcoats; blue dyes and red dyes; dyes on unusual substrates; medieval dyeing and eighteenth-century sources on dyeing (

Figure 5); archaeological textiles; and early Modern fashion. The scope was broadened by the posters on display, which included topics such as textiles in a buried early medieval hoard in Scotland, late Iron Age children’s clothing in Finland, and the logwood ink used by the painter Vincent van Gogh in France. Delegates had ample opportunity to study these during breaks and the dedicated poster sessions, so were able to discuss the contents with the authors. This broad range of subjects is typical of Dyes in History and Archaeology conferences, which foster questions, possible answers, and lively debate. (The book of abstracts is available at

https://www.dyesinhistoryandarchaeology.com/past-meetings.php, accessed on 15 July 2025.)

3. Survey of the Articles in This Special Issue

The ten papers included in this Special Issue are representative of this variety of topics. In addition, they reveal some interesting trends. One is the discussion of dyes used on substrates that are not textiles; another is the study of textiles that are not the most expensive or precious but were owned by middle-class people or peasants. A third is the surprising amount of information that can be gathered about dyes used on artefacts, even when valuable invasive techniques such as high-performance liquid chromatography linked to diode array or mass spectrometric detection (HPLC-PDA or HPLC-MS) are unavailable. However, perhaps the most significant of these trends is the ethical connection or conflict between modern investigation methods and traditional practices. This has been recognised and increasingly handled with tact and delicacy in the museum and conservation communities for some time, but is less well known to many research workers, including scientists, in other disciplines. An example is the desire to study dyes used by an indigenous people and with a long history that may still be in use today but are poorly understood or, indeed, unknown to researchers outside those communities. Tantalising for a research team—but how should they handle such a situation?

This was the state of affairs facing Thiago Sevilhano Puglieri and Laura Maccarelli in their study of the blue pigments used in the decoration of masks used by the Tikuna/Magüta people of the Amazon forest as part of female initiation rituals [

1]. The use of a blue plant colourant had been mentioned by an ethnologist working with the Tikuna/Magüta people in the 1940s, but scientific examination of masks dating from this period, with the permission of this community, only identified inorganic blue pigments and indigo, all widely available during this decade. The authors were very aware of the great cultural importance of colour and its use to the Tikuna/Magüta people, perhaps particularly blue, a colour which has an almost universal significance. They were also very sensitive to the fact that community engagement and participation in any research carried out were absolutely essential; the balance of the Tikuna/Magüta people with their surroundings must not be compromised, and their permission was obtained before any results were published. The authors decided to proceed with further study through community-based participatory research, whereby the community are fully involved with the project from the design of the research to the dissemination of the results, and their spiritual and cultural needs are given priority rather than the immediate research priorities of the scientists. Both parties benefit from such an approach.

At first sight, the investigation carried out by Elisa Palomino and co-authors might appear somewhat similar to the study of the aforementioned unknown blue pigment in that they were examining a practice that is poorly known in general: the dyeing of fish skins, or fish leather [

2]. However, these materials have been used and dyed by local populations in Arctic regions of Alaska, Siberia, Northeast China, Northern Japan, Scandinavia and Iceland for centuries and are still used today. The skins are tanned using naturally occurring materials such as galls or barks, or industrially using chromium-containing agents or industrial vegetable tanning. A survey by the authors across these regions revealed the use of a great variety of plant and lichen dyes to give a range of colours, particularly browns, greens, golds and yellows, but also pinks and purplish colours. A wider range of colours was found in Northern Japan, where sources of indigo blue, sappanwood reds or pinks, and lac dye pinks and purples were available. The results suggest that traditional tanning and dyeing techniques (not only for fish leather) could provide environmentally friendly and sustainable alternatives to industrial production methods if suitably adapted.

Fish skin is one of the more unusual dyeing substrates discussed in Copenhagen; the other is perhaps a little better known: feathers. Renée Riedler, from the Weltmuseum Wien in Vienna, along with colleagues from Vienna and Mexico, discusses an unusual project in which the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City wished to commission a replica of a rare sixteenth-century featherwork insignia in the Weltmuseum Wien collection [

3]. The replica, needed for didactic purposes, was to be as close to the original as possible, bearing in mind the fact that featherworking techniques used today are somewhat different to those used in sixteenth-century New Spain. Research into the account of the technique and the use of cochineal dye to give the intense red colour required, described in detail in the

Historia General de las cosas de Nueva España by Bernardino de Sahagún (1575–7), as well as careful study of the feathers using Fibre Optic Reflectance Spectroscopy (FORS) and Multiband Imaging (MBI), enabled the team to commission an accurate reproduction of the insignia, made using appropriate, sustainably available feathers and easily reproducible dyeing methods.

The work carried out on the insignia is an example of what can be achieved with careful use of non-invasive methods together with historical documentary evidence. Another example is provided by the examination of Japanese folk textiles dating from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth centuries, discussed by Ludovico Geminiani and colleagues [

4]. These were not the luxurious silk textiles usually examined; in this case, all the kimonos and other textiles were cotton, produced for a lower-class clientele. They were examined using Visible Reflectance Spectroscopy and External Reflection Fourier Transfer Infrared Spectroscopy (ER-FTIR), with the aid of a substantial purpose-made database of samples, including traditional Japanese colourants, synthetic materials and mixtures of materials, all in different concentrations and painted on Fabriano paper. Clearly, there are limitations to the identifications possible when a more diagnostic technique, but one requiring sampling, is unavailable, but, as the authors explain, it is still possible for identifications to be made, either of the colourant itself or of its class. The identification of water-based animal skin glue or rice starch paste in areas decorated using resist printing techniques and hand colouring, as well as conventional dyeing with indigo and Prussian blue, means that the textiles will require careful cleaning and conservation treatment.

A very different and humbler example of peasant clothing is described by Anete Karlsone: orange-yellow aprons worn by Latvian women during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, documented by the writer and cultural historian Johan Christoph Brotze (1742–1823) [

5]. According to this and other contemporary sources, the aprons were dyed with

Orlean, or annatto, from the seeds of the shrub

Bixa orellana L., then available as a medium-priced dye and imported into the region in quite large quantities in the early decades of the nineteenth century. From studying the use of other plant dyes, the author was able to obtain orange- and orange-yellow-coloured textiles, as illustrated by Brotze.

Dyeing aprons is a very typical example of the sort of work that could be carried out at home and is described in innumerable small manuals and other ‘books of secrets’ produced all over Europe from the medieval period onwards. On a larger scale, dyers’ workshops and companies would have been busy dyeing goods for middle- and lower-class clients. A rare example of a book of recipes and accounts from a late eighteenth-century Antwerp dyer is described by Emile Lupatini and Natalia Ortega Saez [

6]. Although the identity of the dyer is unknown, the authors have been able to suggest a site for the premises in the city and, from the dyes used—for example, cochineal for more expensive wool fabrics and soluble redwood dyes on cheaper, coarser cloths—they suggest the status of the clientele. The work of the establishment is set against the economic context of late eighteenth-century Antwerp, during a period described by the authors as one of economic stagnation, contextualisation which is particularly valuable for the reader.

The more expensive and precious side of the dyeing trade is elucidated by Irina Petroviciu and co-authors in their account of liturgical embroideries dating from the late fourteenth to the nineteenth centuries in the National Museum of Art of Romania, Bucharest [

7]. The textiles, described as Byzantine, Moldavian, Wallachian, Greek, Russian, of Viennese origin, or from Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), were studied as part of a programme to document them within the museum collection: in effect, part of the museum cataloguing programme. The sample sites available were thus limited to damaged areas of the supporting silk fabric and, to some extent, embroidery threads visible on the back of the textiles. However, it was possible to show developments in the use of different dyes over time, including the consistent use of indigotin-containing blue dyes, weld and dyer’s broom as yellow dyes, and, importantly, a carminic acid-containing red dye in the red satin supports of embroideries dating from the later decades of the sixteenth century onwards. This is typical of a very common European pattern of dye usage. Earlier liturgical textiles examined in other projects had been found to contain a more varied range of red dyes, but the invariable use of carminic acid-containing dye from about 1570 confirms the quite rapid spread of American cochineal usage right across Europe following its introduction.

Another precious, and indeed royal association is linked to an example of a rarely examined group of textiles: knitted silk waistcoats. One of the two examined by Jane Malcolm-Davies and co-authors is said to have been worn by King Charles I of England at the time of his execution, although it has not been possible to confirm this [

8]. The other, from Drummond Castle, Crieff, Scotland, is said to have been worn by one of the Earls of Perth. Both are pale greenish-blue in colour and damask-knitted. Although analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS) was used, the waistcoats were also examined by the non-invasive methods of confocal micro-Raman spectroscopy and molecular fluorescence in the visible region of the spectrum, crucially aiming to build up a bank of reference data to help in the examination of other items, particularly knitted items, where sampling is impossible. This combination of methods enabled the identification of indigotin in both waistcoats and a yellow dye constituent, daphnetin, in the Scottish waistcoat, which would thus have originally been pale green in colour.

The colour purple also has some regal associations, particularly in the period before the time of Charles I and his waistcoat, although in medieval Europe the use of the exotic and expensive shellfish purple was no longer current: overdyeing a blue-dyed textile with a red dye or the lichen purple dye orchil was the method commonly used. This method was described by Pauline Claisse and co-authors in their study of a late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century tapestry in the Musée de Cluny, Paris [

9].

La vue—Sight, one of six

Lady and the Unicorn millefleurs tapestries—was examined using the non-invasive methods of Hyperspectral Imaging Spectroscopy and LED μ-Spectrofluorimetry (LEDμSF) after conservation treatment had shown that, on the back of the tapestry, the Lady’s skirt, now light blue, retained some purple coloration. A complete set of dyed wool samples was prepared for a comparison of the various possible dyes present and for light ageing using indigo extracted from woad; red anthraquinone dyes extracted from madder, kermes and cochineal; and orchil dye from the lichen

Lasallia pustulata (L.) Mérat (1821). Comparison of the different dyed samples, before and after ageing, with the tapestry itself indicated that the purple colour had been obtained using indigo and orchil, not one of the anthraquinone red dyes. HPLC-PDA examination of a sample of purple wool taken from the back of the tapestry during conservation treatment identified the indigo, but not the purple dye constituent, presumably because the dye in the region sampled was too degraded.

Not all lichen colours are purple. Orchil lichens, in which the dye is extracted using alkali, give the characteristic purple dye, but another group of lichens, in which the dye is extracted using boiling water, gives yellows and browns. These lichens have been widely used, but in more recent centuries; until now, their use in the medieval period has not been identified. During their study of one of the

Heroes tapestries,

Julius Caesar, in The Cloisters Collection of the Metropolitan Museum, New York, Rachel Lackner and co-authors examined a sample of brown wool using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionisation–quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-qToF-MS) [

10]. They identified chlorinated xanthone derivatives, including thiophanic acid, which are metabolites of lichens such as the Mediterranean species

Lecanora sulphurea (Hoffm.) Ach. (1810). This species was used as a comparative sample for the analysis as its population is sufficiently large and stable. The results provide evidence for the use of boiling-water extraction of a non-orchil type (or crottle-type) of lichen dye in fifteenth-century France or the Southern Netherlands, although it is not possible to say which lichen was actually used.

4. Conclusions

The range of subjects covered in this Special Issue is interesting in several ways. The decision to proceed with community-based participatory research in a proper partnership with the Tikuna/Magüta people to investigate the unknown blue plant colourant they used in the past, and perhaps still use, should not be anything out of the ordinary; in fact, in heritage conservation in general, it is not unusual. This is not the case in every area of research, but its importance will gradually be recognised more widely.

It is particularly encouraging to see results of the study of textiles not owned by the nobility, or the rich and famous in general. It is true that higher-class textiles are more likely to have survived, but this is where documentary research can be so helpful, such as that represented in this collection by the recipe and accounts book of the eighteenth-century dyer in Antwerp. An understanding of the historical and economic context during which a particular range of dyes were used serves to increase our understanding of an earlier time, but one that is still informing and contributing to our world today.

Today, non-invasive examination methods are certainly more powerful and versatile than used to be the case. Their use, backed up by a well-designed database of carefully constructed standard samples, has been amply demonstrated by several of the papers in this collection: on Japanese textiles, on feathers and on tapestry dyes, for example. It is interesting that, in each case, the range of dyes likely to be present was to some extent limited by traditional practice or by availability. Of course, other possible dyes should not be ruled out, but if there is no evidence whatsoever for their availability in that area of the world at that time, then the range selected as standard samples is at least a reasonable starting point. The non-invasive examination can also provide information towards the selection of an appropriate sampling area if a future opportunity to analyse a sample by a chromatographic separation technique arises.

It is also worth noting that the majority of investigations of historical and archaeological artefacts, like those described in this Special Issue, begin within the walls of a museum, gallery, or private collection. Without collaborations between disciplines and institutions to bring in a wider range of expertise, valuable, intriguing and perhaps unexpected information about our recent or long distant past would remain unrecognised and perhaps lost. The value of such collaborations is perhaps particularly significant in the fields exemplified by this collection of papers and it was given visible form by the conference participants themselves, from so many different countries and disciplines, talking and moving from venue to venue (

Figure 6).