Abstract

Cultural heritage in insular regions faces increasing challenges due to overtourism, seasonal economies, and insufficient protection frameworks. This study investigates the adaptive reuse of Sarakina Mansion, a deteriorated 18th-century estate on the island of Zakynthos, as a model for integrating cultural heritage preservation with sustainable tourism. The research addresses the gap in localized strategies for heritage-led development in the context of islands with overtourism. Through a qualitative case study methodology—including site analysis, archival research, and stakeholder interviews—this paper explores how abandoned cultural assets can be reactivated to foster community engagement and diversify tourism models. Two distinct SWOT analyses were conducted as follows: one at the territorial level (Zakynthos Island) and another focused on the island’s cultural heritage. The findings highlight key obstacles such as environmental degradation and policy fragmentation, but they also reveal opportunities for adaptive reuse grounded in local identity and sustainable practices. The proposed reuse scenario for Sarakina promotes partial structural stabilization and community-driven cultural programming, aiming to create a hybrid open-air cultural hub. This study contributes a replicable framework for reimagining neglected heritage assets in overtourism-affected areas, aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

1. Introduction

Cultural heritage significantly supports sustainable development by fostering social cohesion, economic growth, and environmental sustainability while encompassing both tangible and intangible elements that shape the identity and continuity of societies []. Tangible and intangible cultural resources strengthen local identity, encourage community participation [,], and support sustainable tourism and the creative economy []. Eco-friendly preservation methods contribute to ecological and landscape conservation. Integrating cultural heritage into development strategies promotes resilient, innovative societies through both direct (economic alignment) and indirect (relational values) benefits []. Aligned with the UN 2030 Agenda, cultural heritage preservation is connected to multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), involving education, infrastructure, resource management, and peaceful coexistence []. Across the world, historic buildings, monuments, and traditional settlements serve as living testimonies of the past, fostering social cohesion, economic growth, and environmental sustainability. However, in many cases, these cultural assets face significant threats due to neglect, urban expansion, and, paradoxically, the pressures of mass tourism []. This challenge is particularly acute in insular regions, where rapid tourism-driven development often leads to the deterioration of heritage sites, environmental degradation, and the loss of local cultural identity []. Consequently, overtourism in “sea–sun” destinations [] defines the local economy that is usually characterized by high seasonality, high permanent accommodation costs, and overdependence on the tertiary sector of the economy [].

Zakynthos, a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, illustrates the fragile balance between cultural preservation and tourism growth. Once known for its Venetian-influenced architecture and historic estates, much of its built heritage was destroyed by the 1953 earthquake. In the aftermath, unchecked tourism development overshadowed conservation efforts, leaving many historic structures neglected. Among them is Sarakina Mansion, an 18th-century estate that remains a poignant symbol of the island’s architectural and social history. Despite its significance, it has suffered from structural decay, looting, and lack of protection—highlighting broader heritage challenges in the context of islands with overtourism.

This study explores the adaptive reuse of Sarakina Mansion as a model for integrating heritage conservation with sustainable tourism in Zakynthos. It considers the roles of community engagement, sustainable policy, and innovative conservation in revitalizing abandoned sites. Ultimately, it advocates for an approach that preserves heritage while fostering local participation, education, and diverse tourism models that support the long-term resilience of island culture.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cultural Heritage and Insularity

Insularity refers to the combination of natural, economic, social, and cultural characteristics that define the unique identity of islands []. These regions often exhibit distinct geomorphological features and geographical isolation [], which shape their economic and social development. This isolation commonly results in limited connectivity with mainland areas, leading to high transportation costs and restricted access to essential goods and services [,]. Island economies typically rely on a narrow range of sectors—most notably tourism and fisheries—due to limited natural resources and small domestic markets. This dependence makes them particularly vulnerable to external shocks, such as environmental crises or fluctuations in global tourism demand [,]. Additionally, challenges like seasonal employment, import dependency, and limited access to services such as healthcare and education contribute to structural inequalities between islands and mainland regions.

Despite these vulnerabilities, islands maintain strong cultural identities shaped by historical trajectories, environmental constraints, and close-knit social structures []. This cultural richness positions heritage as a potential driver for sustainable development []. However, the dominance of mass tourism in many island economies has led to negative impacts, including environmental degradation, the over-commercialization of heritage, and the erosion of local traditions. Addressing the challenges of insularity requires a holistic approach that integrates cultural heritage conservation into sustainable tourism policies. Such integration can help ensure the long-term resilience of island communities—economically, socially, and environmentally [,]. The case of Sarakina Mansion in Zakynthos illustrates how the pressures of insularity—particularly overdependence on tourism, environmental fragility, and loss of traditional identity—can be addressed through heritage-led revitalization. As a rural architectural landmark now in ruins, Sarakina embodies the cultural and historical richness that is often sidelined in favor of mass tourism. Its adaptive reuse could offer a tangible opportunity to mitigate the socio-economic vulnerabilities of insular regions by fostering community-based tourism, educational engagement, and cultural continuity.

2.2. Overtourism in Correlation with Cultural Heritage Revealing

Given these conditions, the rise of tourism as a dominant economic force in island contexts introduces a new set of challenges. Chief among them is overtourism, which exerts pressure not only on environmental systems but also on cultural heritage itself. The development of tourism in island regions significantly influences not only economic structures and infrastructural expansion but also the stewardship of cultural heritage. As tourism intensifies, it plays a formative role in shaping how cultural assets are interpreted, preserved, and presented—generating opportunities for local economic development and cultural promotion, while simultaneously raising concerns regarding the erosion of authenticity and the commodification of heritage resources []. These dynamics are particularly evident in insular territories such as Zakynthos, where the tourism sector exerts substantial pressure on both ecological systems and cultural identity. In response to these challenges, there is a growing recognition of the need for strategic heritage management frameworks grounded in environmental impact assessments, long-term planning, and principles of sustainability. Alternative tourism models—including heritage tourism [], eco-cultural tourism [], and community-based tourism []—offer pathways for achieving more resilient and inclusive development. These models prioritize the integration of cultural heritage into tourism practices while actively involving local communities in decision-making processes, thereby aligning economic objectives with cultural preservation imperatives [,].

Nevertheless, the quantification of tourism’s impact remains methodologically complex. No single metric exists to definitively assess the degree of tourism development in a given area. However, a suite of indicators—such as the Tourist Density Index (TDI), Accommodation Capacity Index (ACI), Seasonality Index (SI), and Tourism GDP Share (TGS)—can serve as valuable tools for monitoring tourism intensity and informing evidence-based policy decisions [,,]. These measures are particularly pertinent in the context of overtourism, defined by the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) as the excessive impact of tourism on a destination that adversely affects residents’ quality of life and the visitor experience []. Zakynthos provides a compelling case study in this regard. The island’s tourism trajectory closely aligns with Butler’s “Tourism Area Life Cycle” (TALC) model [], which outlines a staged evolution of tourist destinations—from exploration and involvement to development, consolidation, and ultimately stagnation or rejuvenation. In the early phases, tourism is characterized by small-scale visitation and limited infrastructure. As the destination gains popularity, local communities begin to participate more actively, offering basic services and accommodations. This is followed by large-scale development, often driven by external investors and public authorities. While such growth can increase economic output, it frequently leads to the marginalization of local actors, spatial congestion, and a loss of cultural specificity. During the consolidation stage, mass tourism typically dominates, accelerating pressures on local ecosystems and communities. Without corrective interventions, destinations may enter a phase of stagnation or decline, although recovery remains possible through sustainable reinvention and adaptive strategies [].

Within this evolution, the role of the local community is frequently reduced to that of a passive recipient of top-down changes, with “community” often understood solely in geographic terms. However, sustainable tourism requires a more nuanced conceptualization of community—as a socially and culturally interconnected network defined by shared values, experiences, and aspirations [,,]. In this context, cultural heritage, encompassing both tangible and intangible elements, functions as a critical component of communal identity. It demands a collective ethic in which individual interests are aligned with the broader well-being of the group and where mutual trust supports cooperative decision-making processes [,,].

In the case of Zakynthos, the island’s apparent transition into the stagnation phase of the tourism lifecycle has had profound implications for both environmental integrity and cultural continuity. A prominent illustration of these tensions is the abandoned Sarakina Mansion—a neglected heritage asset that has been overshadowed by infrastructure catering to mass tourism. Yet this site also presents a strategic opportunity for sustainable intervention. The adaptive reuse of Sarakina, framed within a broader cultural regeneration initiative, could reposition heritage as a central element of the island’s tourism strategy. Rather than serving as a decorative backdrop, cultural heritage could be reconceptualized as an active agent of community engagement, education, and socio-economic renewal. Such an approach aligns with broader goals of sustainable development, offering a pathway for Zakynthos to move beyond extractive tourism models and toward a more balanced, culturally embedded future.

2.3. Adaptive Reuse of Neglected Heritage

In response to these pressures, the adaptive reuse of neglected cultural heritage sites is an essential strategy for preserving historical identity while responding to contemporary social, environmental, and economic needs []. Many heritage sites, especially those in rural or peripheral regions, fall into disrepair due to a lack of formal protection, limited funding, or disconnection from mainstream tourism and development agendas []. Adaptive reuse provides a sustainable alternative to abandonment or demolition by reintegrating these sites into the life of the community []. Through sensitive restoration and thoughtful reinterpretation, neglected buildings can regain relevance—serving as cultural centers, educational hubs, or creative spaces that honor the past while meeting present needs [,,].

Beyond preservation, adaptive reuse contributes significantly to local resilience and regeneration. It fosters cultural continuity, revitalizes surrounding areas, and often activates local economies by generating jobs, attracting tourism, and supporting small businesses. Moreover, adaptive reuse typically requires fewer resources than new construction and promotes ecological responsibility by reducing waste and conserving materials []. Importantly, when projects engage local stakeholders in planning and implementation, they also reinforce community identity and pride. In this way, adaptive reuse transforms forgotten heritage into dynamic assets that enrich both place and people—bridging memory and innovation in a way that pure conservation or commercial redevelopment rarely achieves []. Achieving these outcomes requires an interdisciplinary, participatory approach involving both local stakeholders and broader institutional collaboration [].

In this context, the adaptive reuse of Sarakina—restoring the building while preserving its historical integrity—would allow it to be reintegrated into the island’s cultural and social fabric. This process would safeguard a significant architectural asset while advancing sustainable, experience-based tourism practices by shifting emphasis from extractive visitor practices toward experiential, place-based engagement. In this context, Sarakina’s revival through adaptive reuse represents more than preservation; it becomes a strategic act of cultural regeneration aligned with long-term sustainability goals.

3. Materials and Methods

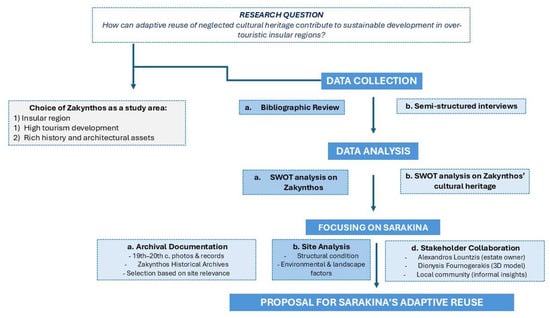

This study adopts a qualitative case study methodology to investigate how the adaptive reuse of neglected cultural heritage can foster sustainable development in overtouristic island settings (Figure 1). Using the Sarakina Mansion on Zakynthos as the central case, the research is guided by the following question: How can the adaptive reuse of neglected cultural heritage contribute to sustainable development in overtouristic insular regions?

Figure 1.

Methodological approach of this study.

To address this question, the analysis began with a bibliographic review of materials from local archives to contextualize Zakynthos’ cultural and developmental landscape. Additional data collection included an academic literature review, archival research, field observations, and stakeholder engagement.

Stakeholder engagement played a central role in the research. In July 2022, thirty semi-structured interviews were conducted with individuals representing diverse age groups, professions, and regions of the island. The interview protocol was designed with criteria to ensure rigor, including conceptual clarity, coherence, structuring, and appropriate length. Interview data were manually coded using qualitative techniques such as highlighting, thematic clustering, and spreadsheet-based categorization. This allowed for the identification of key themes related to sustainability, cultural identity, and tourism impacts.

Data analysis combined thematic analysis, SWOT analysis, and comparative case study methods. Thematic analysis was used to identify recurring patterns across the qualitative dataset, focusing on topics such as tourism pressure, cultural heritage preservation, and sustainable planning. Two parallel SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analyses were conducted to support strategic evaluation. The first, at the territorial level, examined Zakynthos’ development dynamics—natural and cultural assets, tourism dependency, infrastructure capacity, and governance challenges—offering a macro-level perspective. The second, focused specifically on the cultural heritage sector, assessed internal factors such as asset richness, conservation practices, and institutional resources, alongside external variables like tourism demand, environmental pressures, and funding availability. These combined analyses informed the selection of Sarakina Mansion as a focal point for deeper investigation.

An analysis of Sarakina Mansion was also carried out. Bibliographic and archival research drew on academic publications and historical records, including 19th- and 20th-century photographs from the Lountzis family archive. These were cross-referenced with secondary sources to construct a narrative of the mansion’s historical and cultural value. In April 2023, a site analysis was conducted to assess the building’s structural condition, material integrity, landscape context, and environmental vulnerabilities. Field observations and photographic documentation were undertaken, although access to certain interior areas was restricted due to safety concerns. These assessments informed evaluations of restoration needs and adaptive reuse potential. Further depth was added through key stakeholder interviews. Alexandros Lountzis, co-owner of the estate, provided historical insights, reflections on past conservation efforts, and perspectives on future reuse. In parallel, Dionysis Fournogerakis contributed technical expertise through his independent geometric documentation and 3D modeling of the mansion, supporting restoration planning with measurable data.

Based on these findings, the study proposes the adaptive reuse of Sarakina Mansion as a multifunctional cultural and environmental heritage center. This proposal aligns with opportunities identified through the SWOT analyses and responds to the island’s broader need for sustainable cultural infrastructure. Through sensitive restoration and active community engagement, Sarakina could serve as a replicable model of heritage-led sustainable development in Zakynthos and comparable island settings.

The main limitations of the study include restricted physical access to parts of the site, the absence of quantitative data (e.g., tourist traffic statistics), and budget constraints preventing full implementation. Nonetheless, the findings provide a foundation for future work, including participatory design processes, environmental and social impact assessments, and the broader application of adaptive reuse strategies in tourism-saturated regions. Sarakina is positioned as a test case for how cultural heritage can be repurposed to support resilient, community-centered development in insular environments.

4. Study Area Analysis

4.1. The Case of Zakynthos Island

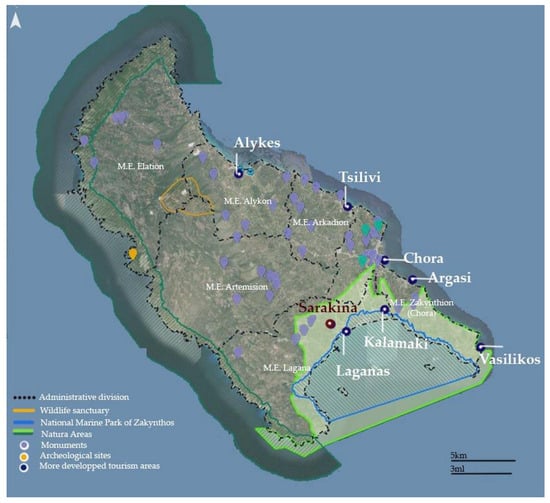

Zakynthos is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea. It is the third largest of the Ionian Islands, with an area of 405.55 km2 and a coastline 123 km in length with 41,180 inhabitants. The island has an international airport and also features two ports, the main port located in the capital, and another in the village of Agios Nikolaos (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Location of the study area.

Zakynthos presents a geographically diverse landscape, with a mountainous western plateau, fertile eastern plains, and distinct peninsulas enclosing the Bay of Laganas. The capital, Zakynthos town, located on the northeast coast, serves as a transportation hub, while protected Natura 2000 zones exist along the western and northeastern coasts []. The island is administratively divided into six municipal units and forty-six communities, reflecting a complex spatial organization. Land use is heavily shaped by tourism, which often conflicts with agriculture due to unregulated construction of rental accommodations. This scattered development, especially in areas like Vasilikos and the eastern coastline, has led to the erosion of farmland and a disordered built environment [,]. The lack of spatial planning, rapid tourism expansion, and over-reliance on tourism pose significant threats to the island’s natural and cultural assets, undermining long-term sustainability.

Zakynthos has been inhabited since prehistoric times, with Mycenaean cemeteries found in Keri and Tragaki. It prospered as a classical city-state, later falling under Roman rule in 150 BC and facing subsequent invasions. Christianity spread early, with local tradition linking it to Mary Magdalene. The island passed through Byzantine, Orsini, Neapolitan, and Tocco control before becoming Venetian in 1485. Under Venice, it served as a military base but faced pirate raids and unrest. Later ruled by the French, Russians, and British, Zakynthos played a key role in the Greek War of Independence and was united with Greece in 1864. The 20th century brought political conflict, WWII occupation, and a strong local resistance movement [,].

The island has experienced numerous devastating earthquakes throughout its history. Major quakes occurred in 1469, 1514 (causing a land gap between Bochali Hill and Agios Elias), and 1622 (separating Cape Agios Sostis from the main island). A prolonged earthquake in 1742 shook the island for a year, followed by destructive quakes in 1768, 1809, 1820, 1840, 1893, and 1912. The most catastrophic earthquake struck on 12 August 1953, with a magnitude of 7.2, leveling nearly all buildings except a few earthquake-resistant structures. This led to strict building regulations requiring reinforced concrete frameworks. Consequently, later earthquakes in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2006 caused minimal damage to modern buildings [].

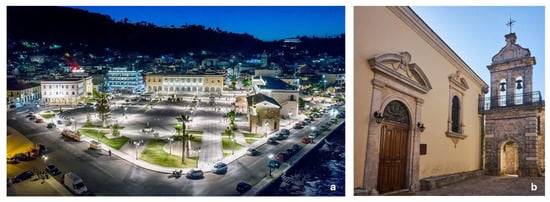

In general, the island’s architecture differs from that of the other Ionian Islands due to its unique historical conditions. To understand the distinctiveness of Zakynthian architecture, one must consider the various phases of its history. The occupation of the Ionian Islands by the Franks and Venetians for over seven centuries played a crucial role in shaping the Ionian architectural style [,]. These Western European architectural influences were inevitably assimilated by the Ionian islanders, who adopted Renaissance architecture and later Neoclassicism. Zakynthos’ architecture developed over the last few centuries, as the colonial presence of the Venetians, French, and British significantly influenced the island’s cultural sector. A key factor shaping the island’s urban layout and architecture was the devastating earthquakes, particularly that of 1953. This earthquake leveled most of the island, destroying buildings and monuments of significant historical value. Afterward, the town was almost entirely rebuilt, with efforts made to restore its traditional style. However, poverty and lack of planning did not allow for complete reconstruction in the desired manner [] (Figure 3).

The mansions in Zakynthos, mostly three-story structures with firebrick facades, have mostly disappeared, though countryside mansions remain notable for their complexity, large facades, and many rooms, following a medieval Venetian model. Urban and folk houses were influenced by these mansions, often featuring overhanging upper floors. Public buildings, characterized by arches, reflect Venetian architectural influence, creating picturesque arcades typical of the Ionian style. Traditional rural houses, particularly in the villages of “Riza” and mountainous areas, are stone-built with tiled roofs, symmetrical facades, and open arcades, blending Western stylistic elements adapted by local craftsmen. A key feature of Zakynthian churches is their bell towers, often located beside the churches and typically small, as no churches follow the Byzantine style. Three-aisled basilicas like the Catholic Monastery of Anafonitria and Saint Mary in Maries were introduced after the 1953 earthquakes. Monasteries outside the city are important examples of Byzantine art, many of which were preserved or restored after the earthquake and feature battlements for defense against invaders [,,,,,,,] (Figure 4).

In Zakynthos, there are thirteen museums, one Mycenean archeological site in Gyri, and almost thirty declared monuments, mostly churches, with three Venetian towers among them and five private buildings. The majority of them are located in the central and southern part of the island. These are not registered in the Greek intangible heritage database and none of the island’s settlements are under a protective framework as traditional. However, there are numerous valuable traditional buildings within the settlements of the island that are abandoned and mostly unknown [,], (Figure 4).

Zakynthos’ Tourism Development

Zakynthos’ economy is primarily driven by tourism and agriculture, with tourism accounting for approximately 68% of local economic activity. Agriculture contributes around 12%, with key products including olives, currants, and regional specialties like ladotyri cheese and Verdea wine. However, tourism has led to a nearly 20% reduction in arable land, and the agricultural sector faces challenges such as limited irrigation infrastructure. The secondary sector remains small and focused on processing agricultural goods, often through family-run businesses [].

Tourism is the most significant economic activity in Zakynthos today. Over the past four decades, mass tourism has grown rapidly, leading to issues such as uncontrolled construction, business congestion, and excessive exploitation of natural resources. Tourism is the driving force of the island’s economy, with the tertiary sector’s contribution to the Gross Regional Product increasing steadily. According to the Tourist Density Index (TDI) and Accommodation Capacity Index (ACI) indicators, Zakynthos could be characterized as an overtouristic island (TDI = 24.5, ACI = 0.61). The tourism boom began in the 1980s and continues to this day, spurring infrastructure development and rapid growth in local markets. The prevalence of “all-inclusive” hotel packages has negatively impacted small tourism-related businesses, particularly in the food and beverage sector []. Economically, tourism is the backbone of the island, making it highly dependent on global tourism trends. Any downturns in international tourism directly impact Zakynthos [,]. The majority of tourism activity on the island is focused on Laganas, Argasi, Kalamaki, Alykes, Tsilivi, and Vasilikos (Figure 4). Zakynthos attracts a large share of tourists visiting the Ionian Islands. However, key challenges continue to affect the sustainability of Zakynthos’s tourism industry. One major issue is high seasonality, as the tourist season typically spans only five months (from May to October), leaving the local economy largely inactive during the rest of the year. The prevailing mass tourism model offers limited opportunities for extending this season. Additionally, there is a strong dependence on a narrow range of source markets, particularly the United Kingdom. Large tour operators dominate the industry by leasing accommodations annually, which not only restricts local control over the tourism flow but also drives down rental prices, reducing overall profitability for local tourism businesses [].

Figure 3.

Characteristic examples of Zakynthos’ architecture: (a) Chora. (b) The mountainous traditional settlement of Loucha in the northern part of the island.

Figure 4.

Map of Zakynthos depicting the cultural and environmental points of interest in the island as well as the settlements characterized by high tourism development.

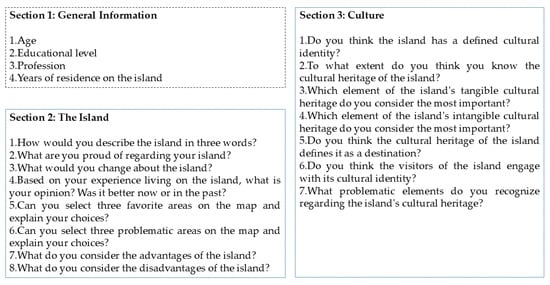

4.2. Investigation of the Opinions of Zakynthos’ Residents About the Island

To understand Zakynthos from the residents’ point of view, thirty semi-structured interviews across groups, professions, and regions of the island were conducted. The interviews were structured in three sections as follows: the first section had to do with general information, the second with the opinions of the residents about the island, and the third section was focused on Zakynthos’ residents’ opinions about the island’s cultural heritage (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Questions for the semi-structured interviews.

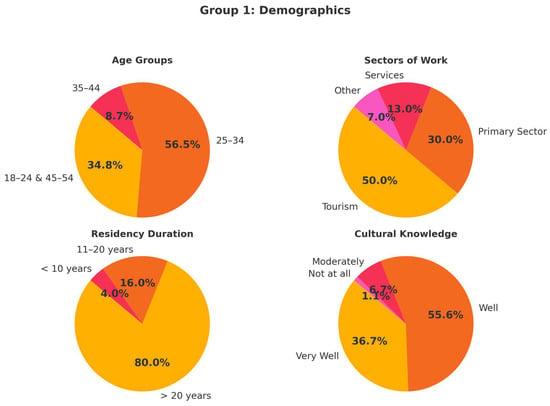

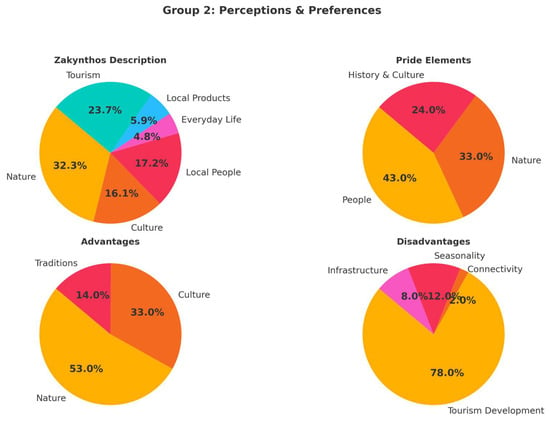

Five participants belonged in the age group 18–24 and 45–54 (16%), eight in the age group 25–34 (26%), and four in the age group 35–44 (4%). Half of them work in tourism (50%), nine in the primary sector (30%), four of them in services (13%), and one in other sectors of the economy (7%). Most of them have stayed on the island for more than twenty years (80%), five participants from eleven to twenty years (16%), and one participant for less than ten years (4%), (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Pie diagrams: Demographics of the informants.

Following the questions about the island, 30% of the answers about the description of Zakynthos had to do with nature, 15% of them had to do with culture, 16% of them had to do with local people, 4,5% of them had to do with everyday life, 5,5% had to do with local products and 22% of them had to do with tourism. The elements of Zakynthos that make its residents proud of the island are its people (43%), its nature (33%), and its history and culture (24%), and the majority of them feel that life on the island was better in the past (62%). The majority of them prefer locations in the northern part of the island, mostly because of the natural beauty and architectural assets (75%), whereas 80% of the residents feel that the worse area of the island is Laganas, mostly due to uncontrolled tourism development. For the residents, the main advantages of the island are its nature (53%), its culture (33%), and its traditions (14%). The main disadvantages are tourism development (78%) and the difficulties in connectivity (2%), seasonality (12%), and infrastructure (8%), (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Pie diagrams: Opinions of the informants about Zakynthos.

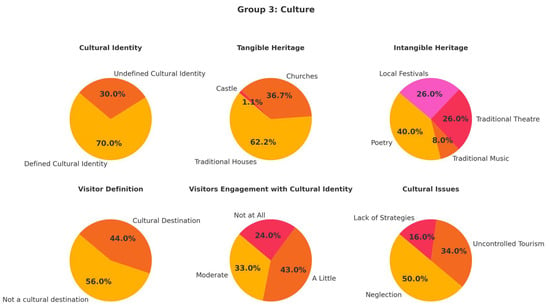

Focusing on questions related to culture, 70% of the residents feel that the island has a defined cultural identity. Ten of the participants feel that they know the island’s cultural heritage very well (33%), half of them well (50%), three of them moderately (6%), and only one of them not at all (1%). Seventeen of the participants feel that the traditional houses/architecture (56%) are the most important elements of the tangible cultural heritage of the island, twelve of them pointed out the churches (33%), and one of them the island’s castle (1%). The intangible elements of Zakynthos’ cultural heritage referenced were poetry (40%), traditional music (8%), traditional theater (26%), and local festivals (26%). More than half of the participants feel that the visitors of the island do not define it as a destination (56%), and ten of them feel that visitors engage with the island’s cultural heritage from moderately (33%) to little (43%). Finally, the major issues they pointed out about the island’s cultural heritage are neglect (50%), uncontrolled tourism (34%), and the lack of proper preservation strategies (16%), (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Pie diagrams: Opinions of the informants about Zakynthos’ culture.

4.3. SWOT Analysis of Zakynthos and Zakynthos’ Cultural Heritage

Following the study area analysis, the Greek Tourism 2030 Action Plan: Ionian Islands [] and the investigation of Zakynthos’ residents’ opinions, two SWOT analyses were conducted to demonstrate the most important strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats to Zakynthos and Zakynthos’ cultural heritage.

The tables below demonstrate the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats to Zakynthos (Table 1) and its cultural heritage (Table 2), respectively.

Table 1.

SWOT analysis of Zakynthos.

Table 2.

SWOT analysis of Zakynthos’ cultural heritage.

The SWOT analysis for Zakynthos highlights its strong natural beauty, rich cultural heritage, and well-developed tourism infrastructure as key strengths that attract international visitors. However, the island faces significant weaknesses, including a heavy dependence on seasonal tourism, environmental degradation, and overcrowding during peak months. Despite these challenges, Zakynthos has substantial opportunities to diversify its tourism model by promoting sustainable practices, off-season activities, and niche markets such as wellness and cultural tourism. At the same time, it must confront pressing threats like climate change, economic uncertainty, and growing competition from other Mediterranean destinations. Addressing these issues through strategic planning and infrastructure investment is essential to ensuring the long-term sustainability of tourism on the island.

The SWOT analysis of Zakynthos’ cultural heritage reveals a strong foundation rooted in its rich historical legacy, vibrant local traditions, and celebrated literary and artistic figures, such as Dionysios Solomos. Cultural festivals and a wealth of historical architecture provide significant potential for cultural tourism. However, key weaknesses include the underutilization and inadequate maintenance of heritage sites, limited year-round cultural offerings, and a general lack of visitor awareness. These challenges are compounded by threats such as overtourism focused on beaches, the erosion of traditional practices, neglect of lesser-known sites, and climate-related damage to historical structures. Nevertheless, opportunities exist to revitalize the island’s cultural profile through targeted promotion, restoration initiatives, educational programs, and international collaborations—enhancing both the visibility and sustainability of Zakynthos’ unique cultural identity.

The SWOT analyses of both Zakynthos as a tourist destination and its cultural heritage landscape reveal critical challenges and untapped potential, which the Sarakina Mansion proposal directly addresses. In a context where overtourism and beach-centric, seasonal models dominate—particularly with the overtouristic area of Laganas nearby—Sarakina offers an opportunity to shift focus towards cultural and heritage-based tourism, an area that remains underutilized despite the island’s rich historical and literary assets. While older residents are familiar with the island’s cultural history, younger generations may lack this connection, underscoring the need for initiatives like Sarakina that help preserve and pass on this heritage.

As a prime example of Zakynthos’ rural architecture, Sarakina embodies the island’s historical continuity and identity, aligning with broader goals of heritage preservation and sustainable development. Its adaptive reuse as a cultural space—hosting workshops, exhibitions, and educational activities—can boost off-season visitation, engage the local community, and diversify the tourism offering. Furthermore, the restoration of Sarakina will not only safeguard the building but also serve an educational purpose, helping to raise awareness about the importance of heritage conservation among both locals and visitors. Through restoration and conservation efforts, the project will address threats like neglect and climate degradation. Sarakina thus serves as both a unique intervention and a replicable model for integrating cultural heritage into the island’s strategic tourism planning, bridging the gap between policy, place, and people.

The proposal emerged from the following key observations: the over-dependence on sea–sun tourism, which contributes to environmental degradation; the lack of a protective framework for traditional buildings and settlements that survived the 1953 earthquake; and the survival of local identity, albeit on a small scale, amidst mass-tourism pressures, particularly in areas where overtourism pressure is critical.

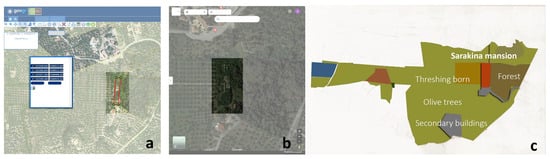

4.4. Focusing on Sarakina

Sarakina is located in the village of Pantokratoras in Zakynthos, at the site with the same name. The current state of the Sarakina Mansion building is shown in the aerial photographs below (Figure 9). There is no precise topographic survey of the building. The total area of the Sarakina estate, according to the decision of the Zakynthos Forestry Directorate, is 238,657 square meters. The land uses of the area are presented in Figure 9c. As shown in the relevant diagram, the majority of the estate is covered by olive groves, extending westward from the mansion and perpendicular to the slope of the hill. To the east of the building lies a dense woodland. The newer structures within the estate are located south of the mansion, without any functional or spatial connection to it. The main access to the mansion was through Maïstra, to the west, which connected the estate to Pantokratoras (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Sarakina’s aerial depictions from: (a) the national cadaster, (b) forest maps, and (c) a diagram of Sarakina’s land uses.

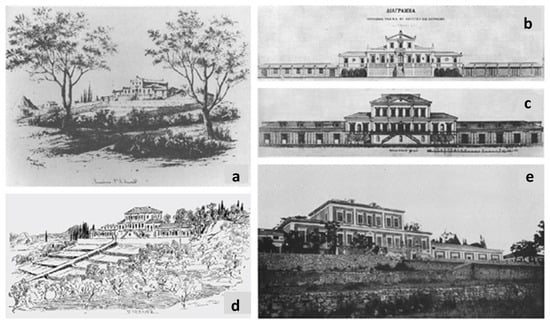

According to bibliographic research, primarily based on the published work of Dionysis Zivas [], the first recorded depiction of Sarakina is a sketch by Anastasios Sartzint (Figure 10a), dated between 1855 and 1857. This suggests that the building was constructed some years earlier. As Zivas also notes, a major reconstruction of the building was decided in the late 19th century, giving it more imposing characteristics (Figure 10b,c), as depicted in a sketch by Archduke Salvator, who visited Sarakina in 1900 (Figure 10d). The building’s form largely remained the same until the 1953 earthquake, as seen in a 1928 photograph (Figure 10e). However, it is worth mentioning that the historical documentation and precise recording of the building’s construction phases remain an independent and unexplored subject, and there is no exact depiction of Sarakina before 1953.

Figure 10.

Depictions of Sarakina (Lountzis’ family archive): (a) The first recorded depiction of Sarakina is a sketch by Anastasios Sartzint; (b) Unnamed Sketch of Sarakina in 19th; (c) Unnamed Sketch of Sarakina in 19th century; (d) Archduke Salvator’s depiction of Sarakina; (e) Photo of Sarakina in 1928.

Sarakina was a characteristic example of Zakynthian rural mansion architecture—considered by Dionysis Zivas to be the most important one. The influence of Venetian architecture, particularly the typology of the Renaissance villa, is evident in most rural mansions on Zakynthos, reflected in their symmetry, layout, building program, and morphology. These estates typically had a dual character, serving as both secondary residences and agricultural centers [,,]. In Zakynthos, despite their simplified forms, rural mansions stood out due to their deliberate monumental appearance and strategic location. They were designed from the outset with a form and volume that not only met functional needs but also established them as landmarks, ensuring their social, historical, and architectural significance.

The Sarakina Mansion has overall exterior dimensions of 11.6 m × 85.50 m and is situated on a 30 m × 130 m plot (Figure 11). The central two-story section and its adjacent raised single-story wings housed the main residential areas. The ground floor, symmetrically arranged around the central passageway (“portego”), contained reception and living spaces, while the upper floor was dedicated to bedrooms. Flanking these were two elongated single-story wings used for essential agricultural and storage functions. The two long façades—the western side facing the maïstra (main access route) and the eastern side facing the woodland—featured a corresponding neoclassical design. According to Zivas, the western façade presented the mansion’s public image toward the village, while the eastern side maintained a more private character. Baroque decorative elements, such as the double columns in the courtyard, paired pilasters, and ornate lintels, combined with the building’s distinctive red walls, gave Sarakina a striking grandeur [].

Figure 11.

Diagrammatic representation of the remaining parts of the building according to the onsite measurements. The remaining parts of the building are the ones in the red frames. (April 2023).

The building’s masonry is mixed, combining brickwork and stonework—primarily at the corners and around openings. Wooden and iron reinforcements contribute to the structural integrity of the mansion. The exterior surfaces are plastered, while the architectural elements are made of carved limestone or porous stone. The remaining staircase is also covered with limestone. The windows feature relieving arches made of brickwork, while some have stone three-part lintels or single wooden lintels for interior doors. The cornices are crafted from molded plaster. Unfortunately, there is no available information regarding the building’s foundation.

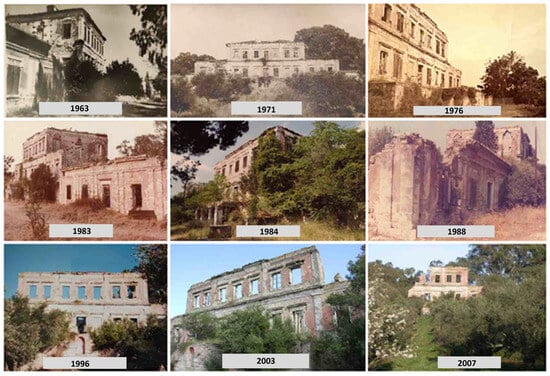

The Sarakina Mansion ceased to be inhabited after the 1953 earthquake, which caused severe damage but did not destroy it. However, due to the lack of immediate restoration efforts, subsequent earthquakes and weather conditions led to its current ruined state (Figure 11). From the last indicative site survey conducted by D. and A. Vlachopoulos, K. Zampas, and Ch. Papakonstantinou in March 2006 to the most recent visit in April 2023 [], it was observed that the building’s already significant deterioration has worsened.

The results of the most recent site visit confirm the previously described condition. Further collapse of the two-story section was observed on both the eastern and western façades, along with a general deviation of the exterior walls from the vertical axis. Additionally, the geometry of most openings has been altered, making the immediate placement of frames impossible, as it would be both dangerous and ineffective given the current state of the structure.

A major issue limiting both the documentation process and the development of a comprehensive restoration plan is accessibility. Even preliminary measurements could only be conducted on the ground-level sections of the southern façade, which are in a relatively better condition, and only partially on the eastern and western façades (Figure 11 and Figure 12). Beyond the building, the woodland on the eastern side forms an impressive yet wild natural landscape. The pathways that, according to the owners, once existed can now only be identified in certain areas as faint traces.

Figure 12.

Sarakina over the years (Lountzis’ family archive).

In 2004, the Lountzis family proposed its reconstruction to the Benaki Museum. This led to the formation of the “Friends of Sarakina Zakynthos” Association, chaired by the late professor Dionysis Zivas, aiming to restore the building as a cultural center. Despite studies and efforts, financial challenges halted the project by 2009 during Greece’s financial crisis. However, the vision of reviving Sarakina as a hub for Ionian history and culture remains relevant and may have a second chance for realization [].

Additionally, according to the officially posted forest maps, the estate is not classified as forest land. The Sarakina building is not under any special protection status—it is neither designated as a monument by the Ministry of Culture (ΥΠΠOA) nor as a preserved building by the Ministry of Environment (ΥΠΕΝ).

4.5. Proposal Scheme for Sarakina

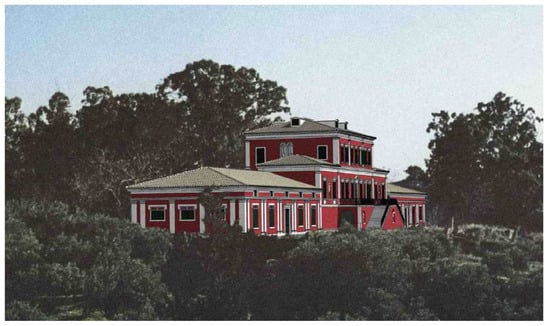

The purpose of the preliminary study conducted was to explore ways to reveal Sarakina while recognizing its historical, architectural, and social significance as a monument. Given the current condition of the structure, the proposed actions fall into three categories of increasing intervention as follows: minimal intervention, limited to necessary demolitions and fencing to ensure visitor safety; structural stabilization, preserving and reinforcing the remaining parts of the building; and full reconstruction, rebuilding the estate in its entirety.

The restoration of the Sarakina Mansion to its original pre-1953 condition is unfeasible due to extensive deterioration and the impracticality of full reconstruction. Instead, the proposal adopts a structural stabilization strategy that preserves the architectural footprint and key elements, reimagining the site as an open-air cultural space. This adaptive reuse approach respects the building’s historical and spatial legacy while integrating minimal new structures to support flexible uses such as exhibitions, events, and educational activities. These interventions aim to maintain the site’s authenticity and visual coherence, enabling visitors to understand its original agricultural and residential functions. While full reconstruction is unattainable, the proposed approach offers substantial cultural, social, and educational value.

More broadly, the initiative responds to the long-standing neglect of historical landmarks in Zakynthos, intensified by the 1953 earthquakes and decades of tourism-driven development. In recent years, shifting attitudes toward heritage preservation and sustainable tourism have opened new possibilities. Sarakina has the potential to become a model for this transition—bridging past and present, revitalizing collective memory, and enriching the island’s cultural identity. It offers a scalable framework for adaptive reuse across the Ionian Islands and beyond. Recent cultural revitalization efforts in Zakynthos include the return of musical and theatrical events, the restoration of historic buildings into functional spaces such as wineries and organic olive mills, and the creation of mountain hiking trails that enhance eco-tourism. New constructions increasingly reflect traditional stone architecture, aligning modern development with local aesthetics and environmental sensitivity.

The Sarakina project builds on this momentum. It envisions a site that preserves the original geometry—potentially through transparent reconstructions—while transforming the surrounding landscape into an open-air venue for concerts, lectures, workshops, and seminars. Community participation is central, ensuring the space reflects local values and aspirations. More than restoration, the project repositions Sarakina as a symbol of Zakynthos’ evolving identity, where heritage and innovation intersect. By engaging with themes like environmental awareness, digital culture, and remote learning, it seeks to remain socially relevant while grounded in history. To ensure long-term sustainability, the envisioned Cultural Center will pursue financial autonomy through partnerships with academic institutions, public and nonprofit entities, and private actors aligned with its mission.

4.5.1. Exhibition and Conference Space Within Sarakina

The proposed Sarakina Cultural Center envisions a dynamic exhibition space both within the stabilized ruins and under lightweight shelters, showcasing historical and architectural documentation of the building, including ongoing 3D modeling research [] (Figure 13 and Figure 14). It will complement existing museums in Zakynthos by offering a broader interpretation of Ionian cultural heritage. In addition to permanent exhibits, Sarakina will host rotating displays from regional institutions and international contributors, particularly from Italy, exploring themes of continuity, reuse, and artistic innovation. A small, architecturally respectful covered structure will support these diverse activities, allowing Sarakina to become an active cultural node for both historical reflection and contemporary artistic engagement.

Figure 13.

Geometric documentation and 3D model production of Sarakina, proposed to be part of the digital representation of the monument.

Figure 14.

Collage of the graphic representation of the original form of Sarakina and the monument at its current state of preservation proposed to be part of the digital representation of the monument.

A central focus of the project is education. The site aims to host outdoor educational programs for students and visitors, fostering cultural awareness through hands-on experiences. A key proposal is the development of “visible” scientific and artistic workshops, allowing research and creative processes to take place on-site in real time. With its structural features made accessible, Sarakina could serve as an open, interdisciplinary lab for studying Zakynthos’ largely overlooked pre-earthquake architectural heritage. These programs would not only revive the island’s cultural legacy but also create an inclusive space where learning, creativity, and public participation intersect—redefining the role of heritage in contemporary Zakynthian life.

4.5.2. Multifunctional Farm—Recreation

Sarakina’s long history as a productive rural estate can be meaningfully revived through the integration of recreational and educational activities into its surrounding landscape. Complementing the Cultural Center’s core functions, features such as walking trails through the historic olive grove and the Loggos forest, outdoor dining focused on local products, and hands-on environmental learning experiences can help reestablish Sarakina as a living cultural landmark. The abandoned village Palia Vlachata in Kefalonia could serve as a useful example since the “Saristra Festival” is successfully organized every year within the ruins of the village’s houses (Figure 15). These landscape-based components—ranging from exhibitions on traditional craftsmanship to guided tours and olive oil tastings—create a multifunctional space where agriculture, heritage, and recreation intersect. Leveraging the success of the existing Sarakina Organic Estate [], the project aligns with global interest in Mediterranean diet products and draws inspiration from similar cultural-agricultural models, like those in Tuscany, to foster knowledge-sharing and community engagement

Figure 15.

Photos from the Saristra festival in the abandoned village of Palea Vlahata in Kefalonia.

Sarakina’s privileged location—perched on a hill with panoramic views of the sea and surrounding mountains, nestled among olive groves and forests—offers exceptional potential as a destination that appeals to diverse audiences. Its proximity to Zakynthos’ well-established tourism infrastructure further enhances its viability as a multifunctional site. Just a 10 min drive from Zakynthos International Airport and blessed with a mild climate suitable for hosting outdoor events much of the year, the estate holds significant historical, architectural, and landscape value that can attract high-end visitors. The proposal for a multifunctional farm operating in synergy with the Cultural Center leverages this unique setting. Activities hosted on the estate could be managed either directly by the Sarakina Cultural Center or in collaboration with external professionals, and these may operate independently of the main cultural program. This flexible structure allows visitors to engage selectively while also ensuring a steady revenue stream to support the long-term sustainability of the broader initiative.

4.5.3. Community and Stakeholders’ Involvement

Community participation is a cornerstone of the Sarakina Mansion’s adaptive reuse, ensuring its long-term sustainability and meaningful integration into local life. Engaging the Zakynthian community in the restoration process fosters a sense of ownership and pride, transforming Sarakina from a neglected ruin into a shared cultural asset. Local residents can contribute through restoration initiatives, storytelling events, and craft workshops, reviving traditional skills while actively shaping the site’s future. Moreover, the project can create economic opportunities by training community members as cultural guides, hosting local artisan markets, and developing sustainable tourism experiences that benefit small businesses. Educational programs in collaboration with schools and universities can further strengthen the connection between younger generations and their heritage, promoting awareness and preservation efforts. To ensure inclusive decision-making, a Community Heritage Council could be established, allowing locals to participate in governance and planning. By embedding Sarakina within the social and economic fabric of Zakynthos, the project not only safeguards a historical landmark but also reinforces community resilience, cultural continuity, and sustainable development (Table 3).

Table 3.

Local community’s involvement in the Sarakina project.

5. Discussion

The relationship between culture and tourism is widely seen as having significant potential to benefit all parties involved, as well as to support local cultural preservation and overall sustainability [,]. However, it is broadly recognized that, so far, the considerable potential for cultural sustainability in the study area remains largely untapped. Overtourism on Greece’s islands [,] has significantly impacted local identities, leading to cultural dilution and environmental degradation. In destinations like Zakynthos, the surge in visitors has overwhelmed infrastructure, resulting in overcrowded streets and strained public services. This influx has also driven up living costs, threatening the prosperity of residents, like in similar Greek study cases [,]. Coping with the results of overtourism [,] demands the redefinition of the destination’s identity in a participatory process involving local communities, stakeholders, and professionals to balance the positive and negative aspects of tourism development [,].

However, the preservation and revealing of cultural heritage, even in over touristic areas, should not be considered as a cause long lost. Cultural identity elements, before managed as products for even the sustainable tourism economy [], should be first known, respected, and understood by the local communities [,]. Understanding the continuity of cultural heritage and its importance at a local level [] should be the core issue of the preservation process []. In this framework, adaptive reuse could efficiently serve this purpose, providing financial, environmental and social benefits [,,].

In line with the United Nations 2030 Agenda, the adaptive reuse of Sarakina directly contributes to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), underscoring the relevance of cultural heritage within the global sustainability discourse []. Most notably, it advances SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) by safeguarding cultural and natural heritage in a region where overtourism threatens local identity and spatial integrity. The project’s focus on educational outreach and community engagement supports SDG 4 (Quality Education) by promoting heritage-based learning and fostering intergenerational knowledge transfer. Through its integration of local craft, cultural programming, and sustainable agritourism, the initiative contributes to SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), creating pathways for responsible economic development rooted in cultural continuity. Furthermore, the environmentally sensitive restoration approach and emphasis on landscape integration align with SDG 13 (Climate Action), demonstrating how cultural heritage can play an active role in mitigating tourism-related ecological pressures. By addressing these interconnected goals, Sarakina could serve as a model of heritage-led sustainability, positioning culture as both a beneficiary and driver of resilient development.

This study reveals key patterns in the mismanagement of cultural heritage within overtouristic island settings, particularly the widespread neglect of rural and architectural sites that fall outside mainstream tourism circuits or lack formal protection [,]. Sarakina’s deterioration reflects a broader trend across Greece’s islands, where long-term cultural value is often sacrificed for short-term economic gain. Contributing factors include weak policy enforcement, fragmented institutional coordination, and decades of tourism-driven land use changes. Additionally, the absence of strategic planning and insufficient community involvement has led to the erosion of intangible heritage and delayed restoration efforts, as seen in the stalled rehabilitation of Sarakina after 2009.

In contemporary cultural heritage management, adaptive reuse is recognized as a valuable strategy, and as outlined in the literature review [,], approaches vary based on a monument’s significance, location, and structure. In Mallorca, Spain, the La Granja de Esporles project transformed derelict farm buildings into a sustainable farming education center, promoting ecological practices while preserving agricultural heritage []. Similarly, Aldeia da Pedralva in Portugal [,] repurposed an abandoned village into agritourism facilities, preserving the traditional character and reshaping the local tourism profile. In cases of severe deterioration, adaptive reuse has revitalized neglected monuments. The Church of Santa María in Adelantado underwent structural restoration, deep cleaning, and lighting upgrades, becoming a local concert venue []. In England, Kenilworth Castle was stabilized and adapted for historical reenactments, festivals, and educational tours, incorporating interactive features like digital guides and reconstructed models []. At the initiative level, Reuse Italy [] launched by Save The Heritage, promotes the adaptive reuse of abandoned buildings through open design competitions, summer workshops, and academic documentation. This model could inspire similar efforts in Zakynthos and the Ionian Islands, particularly in restoring sites like Sarakina. Likewise, the Greek collective BOULOUKI [] focuses on reviving traditional building techniques through community-based workshops and research, engaging local artisans in sustainable heritage projects. These examples show that when adaptive reuse is community-driven and locally grounded, it can enhance cultural identity, diversify tourism, and strengthen social resilience. Sarakina offers an opportunity to apply these principles in Zakynthos, addressing cultural underuse while serving as a model for balancing heritage, tourism, and community in overtouristed regions. In its dilapidated condition, Sarakina stands as a reminder of Zakynthos’ architectural glory before the major earthquake of 1953; as a landmark of the past social organization remembered by the island’s elder inhabitants; as part of a landscape aggressively threatened by uncontrolled tourism development; and as proof of the deficient cultural protection framework in an island that lost the vast majority of its significant architectural assets in 1953. Even so, the proposal scheme described could preserve and highlight the monument’s historical, architectural, and social values [], while promoting its further study and its adaptive reuse as a contemporary cultural site [,].

The proposed adaptive reuse of the Sarakina Mansion offers a replicable model for integrating cultural heritage into sustainable tourism development in overtouristic island regions. By combining restoration, multifunctional programming, and community involvement, the project demonstrates how neglected heritage assets can be reactivated to diversify the tourism offer, reduce seasonal dependence, and alleviate pressure on overcrowded coastal zones. Its emphasis on cultural authenticity, environmental integration, and local participation presents a holistic framework that can guide similar initiatives in other islands facing the dual challenges of mass tourism and heritage neglect. Moreover, the Sarakina model illustrates how small-scale, culturally anchored projects can contribute to the resilience of local economies while reinforcing the identity and cohesion of island communities, which could be adopted as a prototype for public policy in heritage management.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

This study is subject to several limitations. Physical access to parts of the Sarakina Mansion was restricted due to safety concerns, which limited the completeness of the on-site assessment. The research also lacked quantitative data on visitor flows and tourism economics, which could have strengthened the analysis. Additionally, while stakeholder interviews provided rich qualitative insights, they represent a snapshot in time and may not capture evolving community dynamics. Finally, funding constraints limit the implementation of participatory design workshops that could further validate the proposed reuse model. Future steps of this work are the documentation of Zakynthos’s cultural assets, focusing on the least prominent ones, and the collection of archive materials, documents, and oral narratives aiming to create an interactive geospatial database. The goal is to involve educational institutions [,], local organizations, and stakeholders to preserve and understand various elements that shape local cultural identity [,]. A useful reference example that goes beyond adaptive reuse plans for specific buildings and focuses on the overall enhancement of the historic, ruined building stock at a regional scale is Reuse Italy. The initiative’s activities align with the proposed educational uses of Sarakina, while the process of studying and formulating a proposal for the enhancement of the building itself could serve as a model for a similar initiative in Zakynthos or the Ionian Islands’ region. Having as an example the Reuse Italy corporation, the establishment of a network promoting the study and adaptive reuse of cultural heritage assets could set the foundations for an overall sustainable development strategy that is lacking in Greece’s insular areas.

7. Conclusions

This paper examined the adaptive reuse of the Sarakina Mansion in Zakynthos as a model for linking cultural heritage preservation with sustainable tourism in overtouristic island contexts. By exploring insularity, tourism pressures, and local heritage dynamics, the study underscored the need to diversify tourism models and protect neglected cultural assets. Sarakina’s case illustrates how architectural conservation, community engagement, and multifunctional programming can provide a sustainable alternative to mass tourism. SWOT analyses at both the territorial and heritage levels revealed significant challenges—overtourism, environmental degradation, and underutilized heritage—but also opportunities for strategic cultural investment. The Sarakina project addresses these issues by proposing a culturally rooted, year-round engagement strategy that strengthens identity and resilience.

Crucially, this approach also highlights the role of education and institutional collaboration. By involving universities, cultural organizations, and vocational programs, adaptive reuse fosters knowledge exchange, skills training, and public awareness. Although grounded in Zakynthos, the model is transferable; other insular or peripheral regions facing similar pressures can adapt this framework to local conditions. Beyond its local relevance, Sarakina offers a blueprint for heritage-led regeneration with policy potential. Its integration of cultural preservation, education, and sustainable tourism can inform regional planning efforts and serve as a replicable pilot for embedding cultural heritage in sustainable development strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.; methodology, A.V., E.D., A.M. and C.C.; E.D. supervised the overall writing of the paper; A.V. elaborated the results, performed the historical and architectural analysis; conducted the preliminary research on Sarakina, studied the local archives, and illustrated the paper. E.D. and A.V. wrote, reviewed, and edited the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This research has been initiated by Alexandros Lountzis, aiming to achieve Sarakina’ preservation and potential adaptive reuse. The proposal schemes presented were elaborated by him and Anastasia Vythoulka in order to prepare a proposal for the project’s funding addressed to cultural associations in 2023. In this process, the contribution of Dionysis Fournogerakis and his historical and architectural research in progress entitled “Geometric documentation & production of a three-dimensional model of Sarakina” was instrumental. Lastly, the Lountzis family provided valuable depictions and photos of Sarakina from their archive that were invaluable for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ruiz Palacios, M.A.; Villalobos, L.G.; Oliveira, C.P.T.d.; Pérez González, E.M. Cultural Identity: A Case Study in The Celebration of the San Antonio De Padua (Lajas, Perú). Heritage 2023, 6, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throsby, D. The Economics of Cultural Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravanguolo, A.; De Angelis, R.; Iodice, S. Circular Economy Strategies in the Historic Built Environment: Cultural Heritage Adaptive Reuse. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual STS Conference Graz 2019, Critical Issues in Science, Technology and Society Studies, Graz, Austria, 6–7 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Culture and Local Development: Maximising the Impact; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/culture-and-local-development-maximising-the-impact_9a855be5-en.html (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Guzman, P.; Roders, A.P.; Colenbrander, B. Measuring links between cultural heritage management and sustainable urban development: An overview of global monitoring tools. Cities 2017, 60, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vythoulka, A.; Delegou, E.T.; Caradimas, C.; Moropoulou, A. Protection and Revealing of Traditional Settlements and Cultural Assets, as a Tool for Sustainable Development: The Case of Kythera Island in Greece. Land 2021, 10, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouri, M. Merging Culture and Tourism in Greece: An Unholy Alliance or an Opportunity to Update the Country’s Cultural Policy? J. Arts Manag. Law Soc. 2012, 42, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Chen, C.-Y.; Fu, Y.-K. The Sustainable Island Tourism Evaluation Model Using the FDM-DEMATEL-ANP Method. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fafouti, A.E.; Vythoulka, A.; Delegou, E.T.; Farmakidis, N.; Ioannou, M.; Perellis, K.; Giannikouris, A.; Kampanis, N.A.; Alexandrakis, G.; Moropoulou, A. Designing Cultural Routes as a Tool of Responsible Tourism and Sustainable Local Development in Isolated and Less Developed Islands: The Case of Symi Island in Greece. Land 2023, 12, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vythoulka, A.; Kaliakmanis, F.; Delegou, E.; Giannikouris, A.; Kampanis, N.; Alexandrakis, G.; Moropoulou, A.; Chlorokostas, S.; Magkoufis, E.; Kontopoulos, C.; et al. Agritourism as a strategy of remote island’s development: The case study of Kasos. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, A.; Brinklow, L.; Corbett, J.; Kelman, I.; Klöck, C.; Moncada, S.; Mycoo, M.; Nunn, P.; Pugh, J.; Robinson, S.; et al. Understanding “Islandness”. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2023, 113, 1800–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESPON. The Development of the Islands—European Islands and Cohesion Policy (EUROISLANDS); Final Report; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013; Available online: https://archive.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/FinalReport_foreword_CU-16-11-2011.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Luiz-Pérez, M.; Seguí-Pons, J.M.; Salom-Sastre, M. Bibliometric Analysis of Insularity in the European Union. Land 2024, 13, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taglioni, F. Insularity, political status and small insular spaces. Int. J. Res. Isl. Cult. 2011, 5, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royle, S.A. A Geography of Islands: Small Island Insularity; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2001; ISBN 9781857288650. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzola, F.; Pizzuto, P.; Ruggieri, G. Tourism and territorial growth determinants in insular regions: A comparison with mainland regions for some European countries (2008–2019). Pap. Reg. Sci. 2022, 101, 1331–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsi, D.; Lagarias, A.; Stratigea, A. Evidence-Based Exploration as the Ground for Heritage-Led Pathways in Insular Territories: Case Study Greek Islands. Heritage 2022, 5, 2746–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Sustainable Tourism Indicators and Destination Management; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2022; Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/book/10.18111/9789284407262 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Ramazanova, M.; Silva, F.M.; Vaz de Freitas, I. Tourists’ Views on Sustainable Heritage Management in Porto, Portugal: Balancing Heritage Preservation and Tourism. Heritage 2025, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtit, K.; Nijkamp, P.; Suzuki, S. Environmental and Cultural Tourism in Heritage-Led Regions—Performance Assessment of Cultural-Ecological Complexes Using Multivariate Data Envelopment Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, L.A.d.; Walkowski, M.d.C.; Perinotto, A.R.C.; Fonseca, J.F.d. Community-Based Tourism and Best Practices with the Sustainable Development Goals. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitrago, E.M.; Yñiguez, R. Measuring Overtourism: A Necessary Tool for Landscape Planning. Land 2021, 10, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Amaduzzi, A.; Pierotti, M. Is “overtourism” a new issue in tourism development or just a new term for an already known phenomenon? Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 23, 2235–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanassis, A. Over-tourism and anti-tourist sentiment: An exploratory analysis and discussion. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2017, 17, 288–293. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO); Centre of Expertise Leisure, Tourism & Hospitality; NHTV Breda University of Applied Sciences; NHL Stenden University of Applied Sciences. ‘Overtourism’?—Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions, Executive Summary; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwood, S. Planning for Community Based Tourism in a Remote Location. Sustainability 2010, 2, 1909–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C. Revisiting “community” in community-based natural resource management. Community Dev. J. 2005, 40, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brereton, D.J. Community Engagement and Development Booklet; Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, Department of Industry, Tourism and Resources: Brisbane, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Delanty, G. Community; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Henche, B.; Salvaj, E.; Cuesta-Valiño, P. A Sustainable Management Model for Cultural Creative Tourism Ecosystems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilani, P.; Bernini, C.; Mariotti, A. How to cope with dissonant heritage: A way towards sustainable tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1417–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.; Shen, Z.; Bhatta, K.D. Cultural Heritage Deterioration in the Historical Town ‘Thimi’. Buildings 2024, 14, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickard, R. Funding the Architectural Heritage: A Guide to Policies and Examples; Council of Europe Publications: Strasbourg, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Schmit, B. The Island of Zakynthos: Impressions and Experiences; Friends of the Museum of Solomos and Eminent Zakynthians Publications: Athens, Greece, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Aldeia da Pedralva Webpage. Available online: https://www.aldeiadapedralva.com/en/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Available online: https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/kenilworth-castle/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Baker, H.; Moncaster, A.; Al-Tabbaa, A. Decision-making for the demolition or adaptation of buildings. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Forensic Eng. 2017, 170, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravagnuolo, A.; Micheletti, S.; Bosone, M. A Participatory Approach for “Circular” Adaptive Reuse of Cultural Heritage. Building a Heritage Community in Salerno, Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, E.; Robiglio, M. The Transformative Potential of Ruins: A Tool for a Nonlinear Design Perspective in Adaptive Reuse. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: http://www.zakynthos.net.gr (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Available online: http://www.virtualzakynthos.gr/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Strategia, A.; Ladias, C. Directions for the Revision of Regional Frameworks—The Case of the Ionian Islands Region. In The Future of Greece’s Development and Spatial Planning; Ladias, C., Strategia, A., Genitsaropoulos, C., Eds.; University of Central Greece Publications: Lamia, Greece, 2012; pp. 591–611. [Google Scholar]

- Kapsaski, E. Sustainable Tourism Development in Zakynthos. Master’s Thesis, School of Rural and Surveying Engineering, NTUA, Athens, Greece, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Roukana-Abela, M. The Stages of Human Life in Zakynthos; Trimorfo Publications: Zakynthos, Greek, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zivas, A.D. Zakynthos 1953–2003; Periplous Publications: Athens, Greece, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zivas, A.D. The Architecture of Zakynthos from the 16th to the 19th Century; Publication of the Techical Chamber of Greece Athens: Athens, Greece, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Zivas, A.D. Zakynthos Depictions; Trimorfo Publications: Athens, Greece, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sargint, R. Zakynthos Once upon a Time; Friends of the Museum of Solomos and Eminent Zakynthians Publications: Athens, Greece, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dousaki, A. Unexplored Zakynthos; Road Publications: Athens, Greece, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsogiannis, C. Sustainable Tourism Development: The Case of Zakynthos Island. Master’ s Thesis, Department of Spatial Planning and Development Engineering, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ELSTAT. Greek Population Census 2021. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- SETE. Greek Tourism 2030 Action Plan: Ionian Islands. Available online: https://insete.gr/wp-content/uploads/pdf/proorismoi/proorismos-zakunthos.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Lοuntzis, A. Texts and Objects: Design of a cultural centre in the rupture of time (Sarakina, Zakynthos), Diploma thesis, Department of Media and Communication. Master’s Thesis, University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ledermann, F.; Schmalstieg, D. Presenting an Archaeological Site in the Virtual Showcase. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Intelligent Cultural Heritage, Brighton, UK, 5–7 November 2003; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://sarakinaestate.gr/ktima-sarakina (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Mikić, H. Sustainable cultural heritage management in creative economy: Guidelines for local decision makers and stakeholders. In Cultural Heritage & Creative Industries; Rypkema, D., Mikić, H., Eds.; Creative Economy Group Foundation: Belgrad, Serbia, 2015; pp. 9–24. ISBN 978-86-88981-06-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nižić, M.; Ivanović, S.; Drpić, D. Challenges to Sustainable Development in Island Tourism. South East Eur. J. Econ. Bus. 2010, 5, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsartas, P. Tourism Development in Greek Insular and Coastal Areas: Sociocultural Changes and Crucial Policy Issues. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsouris, A. Social learning and sustainable tourism development; local quality conventions in tourism: A Greek case study. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leka, A.; Lagarias, A.; Stratigea, A.; Prekas, P. A Methodological Framework for Assessing Overtourism in Insular Territories—Case Study of Santorini Island, Greece. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Pierotti, M.; Amaduzzi, A. Overtourism: A Literature Review to Assess Implications and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żemła, M. Reasons and Consequences of Overtourism in Contemporary Cities—Knowledge Gaps and Future Research. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayiotopoulos, A.; Pisano, C. Overtourism Dystopias and Socialist Utopias: Towards an Urban Armature for Dubrovnik. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Daumann, F. European Tourism Sustainability and the Tourismphobia Paradox: The Case of the Canary Islands. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Taño, D.; Garau-Vadell, J.B.; Díaz-Armas, R.J. The Influence of Knowledge on Residents’ Perceptions of the Impacts of Overtourism in P2P Accommodation Rental. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuščer, K.; Mihalič, T. Residents’ Attitudes towards Overtourism from the Perspective of Tourism Impacts and Cooperation—The Case of Ljubljana. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żemła, M.; Szromek, A.R. Influence of the residents’ perception of overtourism on the selection of innovative anti-overtourism solutions. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hernández, M.; de la Calle-Vaquero, M.; Chamorro-Martínez, V. Can Overtourism at Heritage Attractions Really Be Sustainably Managed? Lights and Shadows of the Experience at the Site of the Alhambra and Generalife (Spain). Heritage 2023, 6, 6494–6509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padrón-Ávila, H.; Hernández-Martín, R. Preventing Overtourism by Identifying the Determinants of Tourists’ Choice of Attractions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.; Gordon, I.J. Adaptive Heritage: Is This Creative Thinking or Abandoning Our Values? Climate 2021, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G. Circular economy strategies for adaptive reuse of cultural heritage buildings to reduce environmental impacts. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 152, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]