Indigenous Underwater Cultural Heritage Legislation in Australia: Still Waters?

Abstract

1. Introduction

31.1 Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.

31.2. In conjunction with indigenous peoples, States shall take effective measures to recognize and protect the exercise of these rights.

- The ability of Traditional Owners to make decisions regarding their cultural heritage in an offshore, including underwater, context;

- The scope under existing national and international law for the legislative decision-making ability to extend to intangible aspects of Traditional Owners’ underwater cultural heritage.

2. Jurisprudence Regarding the Nature of IUCH

[Nunn and Reid, 2016] recorded Indigenous stories of sea level rise and coastal inundation from 21 locations around Australia. Identifying the temporal depth to Aboriginal memories of inundation, they cross reference transgenerational histories with palaeoclimatological data of postglacial inundation.

They combine ways of knowing Sea Country to produce a narrative of human experience, linked to sea level rise, that stretches back through a foreseeable 7000–18,000-Year period, and calculated ‘the minimum water depth (below the present sea level) needed for the details of the particular group of local-area stories to be true’. For each of the 21 locations this was ‘compared with the sea-level envelope for Australia’ and the ‘maximum and minimum ages for the most recent time that these details could have been observed are calculated’ (Nunn & Reid, 2016, p. 11). [They] thus dedicate effort to dating historical memory, by linking oral tradition to scientific data and temporal episodes of postglacial sea level rise, mobilising these as touchpoints for verification of narrative accuracy.

The Deep History of Sea Country project was the first Australian research program to record ancient submerged cultural heritage on the seabed in a marine context. Those findings elicited debate and discussion, particularly for the material found in the shallow waters just below the intertidal zone …. Those criticisms were met with a straightforward rebuttal to the assertions expressing doubts about the authenticity and age of this underwater material…The new archaeological evidence presented from the 2022 surveys further demonstrates that the archaeological landscape extends under water onto now drowned land surfaces in Murujuga.

Another key piece of evidence that supports the interpretation of these features as water holes comes from the Indigenous knowledge holders who describe these features as part of a known Songline, which refers to the location of waterholes in the landscape as part of a complex geographic and ecological documentation of Murujuga country (Kearney et al., 2023). This case highlights the immense value that traditional and local knowledge can bring to under water cultural heritage studies. Having reconstructed these palaeo-landscapes and environments with confirmed stone artefacts therein, it is now possible to consider the archaeological implications and a direct association between the material culture and natural features.

…identifies and privileges expertise over other forms of knowledge and practice in the management and curation of heritage places and objects. In particular, the AHD identifies the authority of archaeology, architecture and art history as those disciplines best suited to act as stewards of a nation’s heritage.

“Underwater cultural heritage” means all traces of human existence having a cultural, historical or archaeological character which have been partially or totally under water, periodically or continuously, for at least 100 years…”

3. The Commonwealth IUCH Legislative Regime

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth).

- Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth).

- Coastal Waters (State Powers) Act 1980 (Cth).

- Coastal Waters (Northern Territory) Powers Act 1980 (Cth).

- Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth).

- Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

- Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act 2021 (Cth).

- Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Regulations 2024 (Cth).

- Protection of Movable Cultural Heritage Act 1986 (Cth).

- Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018 (Cth).

- Underwater Cultural Heritage Rules 2018 (Cth).

3.1. Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act

- (a)

- Ecosystems and their constituent parts, including people and communities;

- (b)

- Natural and physical resources;

- (c)

- The qualities and characteristics of locations, places and areas;

- (d)

- Heritage values of places;

- (e)

- The social, economic and cultural aspects of a thing mentioned in paragraph (a), (b), (c), or (d).

3.2. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act

The general structure of ATSIHPA is that the Minister (currently for the Environment) may receive an application (“orally or in writing”) “by or on behalf of an Aboriginal or group of Aboriginals seeking the preservation or protection of a specified area from injury or desecration”.4 A 30-day emergency declaration under s 9 can be made if the Minister is satisfied the area is indeed a significant Aboriginal area and under serious and immediate threat of injury or desecration. A potentially ongoing s 10 declaration can be made if the Minister is again satisfied the area is a significant Aboriginal area and under threat of injury or desecration and has received and considered a report going to the various matters set out in subsections (3) and (4). Contravention of the provisions of a declaration is an offence [29] (22). Declarations are disallowable by parliament [29] (15), and can only be made after consultation with the relevant state or Territory Minister [29] (13). Under s 12 a declaration can also be made regarding a significant Aboriginal object.

The breadth, and the subtlety, of the defined expression “Aboriginal tradition” is …demonstrated by the finding of the Minister… as to cultural connection rendering the Specified Area particularly significant “with a degree of antiquity, involving Aboriginal traditions, observances, customs and beliefs that are passed down from generation to generation through dreaming stories, song lines, spirituality, culture and traditional interaction with the cultural landscape comprised by, and within, the Specified Area”.

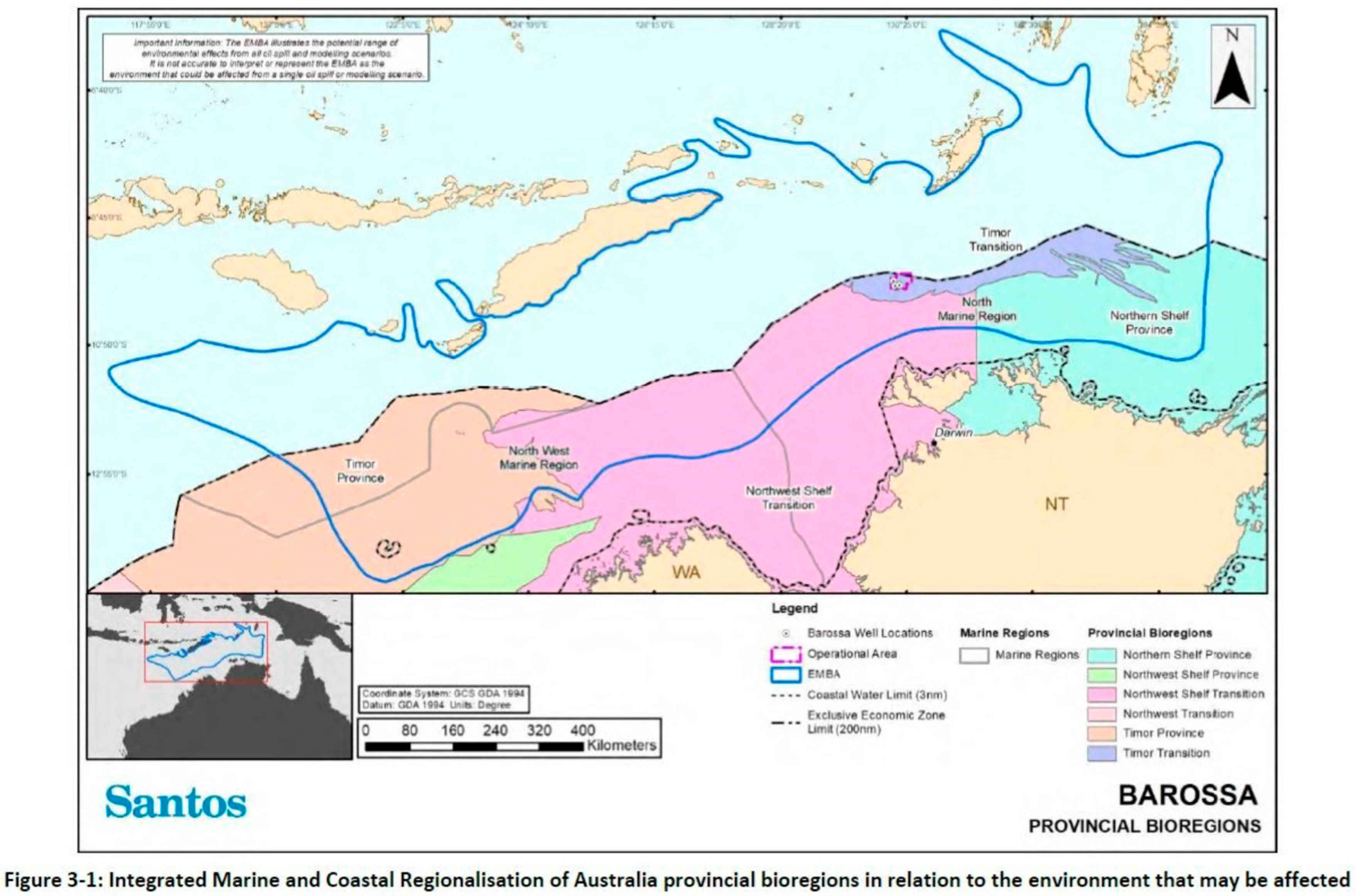

Mr Tipakalippa’s and the Munupi clan’s interests in the EMBA and the marine resources closer to the Tiwi Islands are immediate and direct. Furthermore, they are interests of a kind well known to contemporary Australian law. Thus, interests of this kind, which arise from traditional cultural connection with the sea, without any proprietary overlay, are acknowledged in federal legislation, such as, for example, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth), and have been considered by the courts.

Reference to [ATSIHPA] demonstrates that by this Act the federal Parliament has expressly contemplated the protection of areas of the sea from activities harmful to the preservation of Aboriginal tradition. The Parliament has done so without requiring the existence of particular proprietary interests; rather requiring only the existence of a connection by Aboriginal tradition.

- Has the operational scope to provide protection and through the terms of a declaration a management structure around IUCH.

- Contains broad definitions of “significant Aboriginal [and Torres Strait Islander] area” and of “threat of harm or desecration” that are clearly potentially applicable to both tangible and intangible IUCH.

- Has decision-making structures around the issue of determination of significance and decisions, as to whether to issue a declaration, that operate to completely disempower Indigenous peoples. Further, the ability for “any” Aboriginal (or Torres Strait Islander) person to make a declaration application operates to further disempower the actual Traditional Owners of the cultural heritage in question.

3.3. Underwater Cultural Heritage Act

- A ministerial declaration pursuant to s 17: Under the current Act, (tangible) IUCH can be (but is not automatically) the subject of a s 17 declaration in relation to UCH (that is not the remains of a vessel or an aircraft). This declaration can be made in Commonwealth waters (i.e., Australian waters beyond the coastal waters of a state–s 13).

- Protected Zone declaration pursuant to s 20: If the UCH (including IUCH) was physically within the area of a “protected zone”, declared by the Minister under s 20, it would also be protected. A protected zone declaration can be made in Australian waters “outside the limits of a state”–s 20(2) (i.e., including the coastal waters of a state).

- (a)

- The need to protect underwater cultural heritage that is of particular national or international significance, is rare, or is subject to an international treaty or agreement (however described);

- (b)

- The need to limit access to environmentally, socially, or archaeologically sensitive underwater cultural heritage;

- (c)

- The need to protect underwater cultural heritage that is under threat of interference, damage, destruction, or removal;

- The limited definition of UCH, which arises from the terms of the UCH convention.

- The geographic limitation to the operation of the Act, which excludes the “coastal waters of a state” with respect to a s 17 declaration.

- The complete exclusion of Traditional Owners from both nomination and determination processes.

4. UNDRIP and the UCH Convention

4.1. UNDRIP—Status

4.2. UNDRIP—Content

- Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired.

- Indigenous peoples have the right to own, use, develop and control the lands, territories and resources that they possess by reason of traditional ownership or other traditional occupation or use, as well as those which they have otherwise acquired.

- States shall give legal recognition and protection to these lands, territories and resources. Such recognition shall be conducted with due respect to the customs, traditions and land tenure systems of the indigenous peoples concerned.

- Indigenous peoples have the right to determine and develop priorities and strategies for the development or use of their lands or territories and other resources.

- States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilisation, or exploitation of mineral, water, or other resources.

- States shall provide effective mechanisms for just and fair redress for any such activities, and appropriate measures shall be taken to mitigate adverse environmental, economic, social, cultural, or spiritual impact. (Emphasis added)

- First, although there is no specific mention of Indigenous rights in offshore waters, it is clear from the references to “lands territories and resources” that the more general provisions of UNDRIP would also extend to offshore waters. This would include the Article 31 references to control of cultural heritage and Article 32 references to the need for the free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) of Indigenous peoples to developments affecting their traditional lands and resources (Traditional Owners).

- Second, the collective rights (rights of Indigenous peoples) to control of their cultural heritage and natural resources are exercised through a representative institution of the nature described in Article 18.

- Third, as noted earlier in the investigation, the references to “cultural heritage”—specifically in Article 31 and to the elements of cultural heritage in the other articles reproduced above—clearly indicate that “cultural heritage” for the purposes of UNDRIP contemplates the inclusion of intangible aspects of cultural heritage.

4.3. UCH Convention Outline

The Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH Convention) is the first comprehensive treaty on underwater cultural heritage (UCH). Key elements include the protection and preservation of UCH that has been underwater continuously or periodically for at least 100 years (Art 1 (1) (a)), preferably in situ (in the original place) (Art 2 (5)), including through the cooperation between States Parties (Art 19). The UCH Convention encourages States Parties to sign up to bilateral, regional, or multilateral agreements on UCH and adopt rules and regulations to ensure its protection (Art 6 (1)). The UCH Convention contains provisions relating to public awareness of UCH, (Art 20) education (See for example Art 18 (4), 22 (1)), research (See for example Art 22 (1)), training in underwater archaeology (Art 21), and the exchange of technology (Art 21). Further, the UCH Convention contains an Annex of Rules concerning activities directed at UCH (Annex Rules)

All objects of an archaeological and historical nature found in the Area shall be preserved or disposed of for the benefit of mankind as a whole, particular regard being paid to the preferential rights of the state or country of origin, or the state of cultural origin, or the state of historical and archaeological origin.

In coordinating consultations, taking measures, conducting preliminary research, and/or issuing authorizations pursuant to this Article, the Coordinating State shall act for the benefit of humanity as a whole, on behalf of all States Parties. Particular regard shall be paid to the preferential rights of States of cultural, historical or archaeological origin in respect of the underwater cultural heritage concerned.

4.4. UCH Convention Consideration

While the definition of what is to be protected lacks some clarity, and profers the possibility of introducing a significance requirement in some States’ interpretations, it generally provides a sufficiently wide net to catch the most of what is regarded as archaeologically and historically valuable that is found beneath the oceans[42] (10).

…the issue of whether the underwater cultural heritage of Indigenous peoples should be included in the draft was raised, particularly by Australia since, for this country, issues of underwater cultural heritage involve Aboriginal subaquatic archaeology. However, the Convention finally did not include any mention to their heritage[43] (31).

5. Conclusions

- IUCH is manifest around the Australian continent in both tangible and intangible forms. There is archaeological evidence to suggest that often (but not necessarily always) intangible IUCH is co-extant with areas of pre-inundation human habitation that are likely to also contain elements of tangible ICH.

- The connection between Traditional Owners and their tangible and intangible IUCH is recognised in Australian jurisprudence as giving rise to rights recognised at law.

- Existing Commonwealth legislation, through the EPBC, ATSIHPA and the UCH Act, can operate to protect IUCH. In the case of the UCH Act, this is restricted to tangible IUCH. However, both the EPBC and ATSIHPA are reactive legislation, in the sense that protection only arises in response to a development proposal.

- None of the Australian legislation identified satisfies expectations contained within UNDRIP regarding the ability of Traditional Owners, through their representative institutions, to determine the identity of and act to protect and manage their cultural heritage.

- Perhaps because of this, none of the key pieces of legislation considered has been (reported to be) used to protect IUCH.

- The UCH Convention does have potential application to tangible IUCH but similarly denies Traditional Owners any role in the identification or management of their UCH.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- (1)

- Underwater cultural heritage means any trace of human existence that

- (a)

- Has a cultural, historical or archaeological character;

- (b)

- Is located underwater.

- (2)

- For the purposes of subsection (1), a trace of human existence includes the following:

- (a)

- Sites, structures, buildings, artefacts, and human and animal remains, together with their archaeological and natural context;

- (b)

- Vessels, aircraft and other vehicles or any part thereof, together with their archaeological and natural context;

- (c)

- Articles associated with vessels, aircraft, or other vehicles, together with their archaeological and natural context.

- (3)

- For the purposes of paragraph (1) (b), a trace of human existence is located underwater:

- (a)

- Whether partially or totally underwater;

- (b)

- Whether underwater periodically or continuously.

- (a)

- The significance of the article in the course, evolution, or pattern of history;

- (b)

- The significance of the article in relation to its potential to yield information contributing to an understanding of history, technological accomplishments, or social developments;

- (c)

- The significance of the article in its potential to yield information about the composition and history of cultural remains and associated natural phenomena through examination of physical, chemical, or biological processes;

- (d)

- The significance of the article in representing or contributing to technical or creative accomplishments during a particular period;

- (e)

- The significance of the article through its association with a community in contemporary Australia for social, cultural, or spiritual reasons;

- (f)

- The significance of the article for its potential to contribute to public education;

- (g)

- The significance of the article in possessing rare, endangered, or uncommon aspects of history;

- (h)

- The significance of the article in demonstrating the characteristics of a class of cultural articles.

| 1 | Frequently in Australia the terms “First Nations” or “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander” will be used to describe the original peoples of the continent. In this article the term Indigenous is used to the currency of this term at international law. The term “Traditional Owner” is also used in contexts where the ownership of land and sea country and elements of cultural heritage is being specified. |

| 2 | Essentially the “EMBA” equates to the area that may be affected by a “spill” from the applicant’s operations. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | These provisions are common in ss 9 and 10 and in similar terms in s 12 in the context of a declaration in respect of an Aboriginal object. |

| 5 | (Original footnotes incorporated into the text). |

| 6 | Although this has often been the subject of debate. See, Productivity Commission (Cth), Mineral and Energy Resource Exploration, Report No 65 (Government Report, 2013) [46]. |

| 7 | UNDRIP recognises a limitation on this determinative authority pursuant to Article 46 (2). |

References

- 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity; 1760 UNTS 79, 31 ILM 818; 1992. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/information/parties.shtml (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, Paris, France, 29 September–17 October 2003; [2006] 2368 UNTS 3. UNESCO: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; Adopted 16 November 1972, 1037 UNTS 151, 27 UST 37, 11 ILM 1358; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Disko, S. Indigenous Cultural Heritage in the Implementation of UNESCO’s World Heritage Convention: Opportunities, Obstacles and Challenges. In Indigenous Peoples Cultural Heritage; Xanthaki, A., Valkonen, S., Heinämäki, L., Kristiina Nuorgam, P., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 39–77. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. United Nations Declaration of the Rights on Indigenous Peoples; GA/res/61/295 Ann. 1; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2007.

- Joint Standing Committee on Northern Australia, Parliament of Australia. Never Again: Inquiry into the Destruction of 46,000 Year Old Caves at the Juukan Gorge in the Pilbara Region of Western Australia; Hereinafter “Government Juukan Response”; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2022.

- Joint Standing Committee on Northern Australia, Parliament of Australia. A Way Forward: Final Report into the Destruction of Indigenous Heritage Sites at Juukan Gorge; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2021.

- Australian Government. Australian Government’s Response to the Joint Standing Committee on Northern Australia’s: “A Way Forward: Final Report into the Destruction of Indigenous Heritage Sites at Juukan Gorge”; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2021.

- United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tipakalippa v National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (No 2) [2022] FCA 1121 (“Tipakalippa”). Available online: https://www.judgments.fedcourt.gov.au/judgments/Judgments/fca/single/2022/2022fca1121 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd v Tipakalippa [2022] FCAFC 193 (“Santos FFC”). Available online: https://www.fedcourt.gov.au/services/access-to-files-and-transcripts/online-files/santos-v-tipakalippa (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Munkara v Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd (No 3) [2024] FCA 9. Available online: https://www.judgments.fedcourt.gov.au/judgments/Judgments/fca/single/2024/2024fca0009 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- The Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas (Environment) Regulations 2023 (Cth). (Hereinafter “the Regulations”). Available online: https://classic.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/cth/num_reg/opaggsr2023202300998709/ (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Commonwealth v Yarmirr [2001] 208 CLR 1; HCA 56 (“Yarmirr”) and Akiba v Commonwealth (2013) 250 CLR 209. Available online: https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/cases/cth/HCA/2001/56.html?stem=0%253D0%253Dtitle%2528Commonwealth%2520and%2520Yarmirr%2520%2529 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Nunn, P.D.; Reid, N.J. Aboriginal Memories of Inundation of the Australian Coast Dating from More than 7000 Years Ago. Aust. Geogr. 2016, 47, 11–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, A.; O’Leary, M.; Platte, S. Sea Country: Plurality and knowledge of saltwater territories in Indigenous Australian contexts. Geogr. J. 2023, 189, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, M.J.; Paumard, V.; Ward, I. Exploring Sea Country through high-resolution 3D seismic imaging of Australia’s NW shelf: Resolving early coastal landscapes and preservation of underwater cultural heritage. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2020, 239, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, K. Ownership and use of the seas: The Yolngu of north-East Arnhem Land. Anthropol. Forum 1984, 5, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunn, P.D. Geohazards and Myths: Ancient Memories of Rapid Coastal Change in the Asia-Pacific Region and their Value to Future Adaptation. Geosci. Lett. 2014, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, J.; O’Leary, M.; McCarthy, J.; Reynen, W.; Chelsea Wiseman, C.; Leach, J.; Bobeldyk, S.; Buchler, J.; Kermeen, P.; Langley, M.; et al. Stone artefacts on the seabed at a submerged freshwater spring confirm a drowned cultural landscape in Murujuga, Western Australia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2023, 313, 108190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcombe, P.; Ross, P.J.; Fandry, C. Applying geoarchaeological principles to marine archaeology: A new reappraisal of the “first marine” and “in-situ” lithic scatters, Murujuga (Dampier Archipelago), NW Australia. Geomorphology 2025, 468, 109494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Ethics or Social Justice? Heritage and the Politics of Recognition. Aust. Aborig. Stud. 2010, 2, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. A History of Aboriginal Heritage Legislation in South-Eastern Australia. Aust. Archaeol. 2000, 50, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offshore Constitutional Settlement a Milestone in Cooperative Federalism. Available online: https://www.ag.gov.au/international-relations/publications/offshore-constitutional-settlement-milestone-cooperative-federalism (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Coastal Waters (State Powers) Act 1980 (Cth). Available online: https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdb/au/legis/cth/consol_act/cwpa1980315/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972 (WA). Available online: https://www.legislation.wa.gov.au/legislation/prod/filestore.nsf/FileURL/mrdoc_46659.pdf/$FILE/Aboriginal%20Heritage%20Act%201972%20-%20%5B04-l0-01%5D.pdf?OpenElement (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act 2006 (Q). Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/vic105822.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Storey, M. The Right to Enjoy Cultural Heritage and Australian Indigenous Cultural Heritage legislation. Nord. J. Hum. Rights 2023, 41, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. Available online: https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdb/au/legis/cth/consol_act/alrta1976444/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- BHP Billiton Nickel West v KN (Tjiwarl and Tjiwarl 2 [2018] FCAFC 8 (North, Dowsett and Jagot JJ). Available online: https://aiatsis.gov.au/ntpd-resource/1706 (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (Hereinafter “EPBC”). Available online: https://www.cms.int/saiga/sites/default/files/document/cms_nlp_aus_epbc_act_2_1999.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth) (Hereinafter “ATSIHPA”). Available online: https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdb/au/legis/cth/consol_act/aatsihpa1984549/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Clark v Minister for the Environment [2019] FCA 2027. (Hereinafter “Clark”). Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/INFORMIT.20211005054506 (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Viduka, A.; Luckman, G. The Australian Management of Protected Underwater Cultural Heritage Artifacts in Public and Private Custody. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 2022, 10, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Law Association. Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In Proceedings of the 75th Conference, ILA Resolution No 5/2012, Sofia, Bulgaria, 30 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. To Bind or Not to Bind: The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Five Years on. Aust. Int. Law J. 2012, 17, 17–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzerini, F. Implementation of the UNDRIP Around the World: Achievements and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2019, 23, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, Parliament of Australia. Inquiry into the Application of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Australia; Final Report; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2023.

- Australian Government. Australian Underwater Cultural Heritage Intergovernmental Agreement: An Agreement that Establishes Roles and Responsibilities for the Identification, Protection, Management, Conservation and Interpretation of Australia’s Underwater Cultural Heritage; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2010.

- Parliament of Australia, Joint Standing Committee on Treaties. Report No 207 Australia Iceland Double Taxation, Underwater Cultural Heritage; Government Report; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2023.

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Montego Bay, 10 December 1982) [1994] ATS 31. (Hereinafter “UNCLOS”). Available online: https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetailsIII.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXI-6&chapter=21&Temp=mtdsg3&clang=_en (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Forrest, C.J.S. Defining Underwater Cultural Heritage. Int. J. Naut. Archaeol. 2002, 31, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perez-Alvaro, E. Indigenous rights and underwater cultural heritage: (De)constructing international conventions. Marit. Stud. 2023, 22, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, C. Underwater cultural heritage in Asia Pacific and the UNESCO convention on the protection of the underwater cultural heritage. Int. J. Asia Pac. Stud. 2021, 17, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konso, K. Heritage as a Socio-Cultural Construct: Problems of Definition. Balt. J. Art Hist. 2013, 6, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthaki, A.; Valkonen, S.; Heinämäki, L.; Kristiina Nuorgam, P. (Eds.) Indigenous Peoples Cultural Heritage; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Productivity Commission (Cth). Mineral and Energy Resource Exploration; Report No 65 (Government Report); Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Elizabeth, E. Review of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984; Report by the Hon Elizabeth Evatt AC, Commonwealth of Australia; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 1996.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Storey, M. Indigenous Underwater Cultural Heritage Legislation in Australia: Still Waters? Heritage 2025, 8, 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070289

Storey M. Indigenous Underwater Cultural Heritage Legislation in Australia: Still Waters? Heritage. 2025; 8(7):289. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070289

Chicago/Turabian StyleStorey, Matthew. 2025. "Indigenous Underwater Cultural Heritage Legislation in Australia: Still Waters?" Heritage 8, no. 7: 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070289

APA StyleStorey, M. (2025). Indigenous Underwater Cultural Heritage Legislation in Australia: Still Waters? Heritage, 8(7), 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8070289