1. Introduction

In a remnant of the Atlantic or temperate rainforest in a highland glen of ancient oaks and birch is a group of ruined buildings known as

Larach à Chrotail in Gaelic, thought to mean the lichen house (

Figure 1). There is little evidence for why this group of buildings is so named, but the Gaelic word

crotal used here does refer to lichens, which were used to dye wool in Scotland in shades of brown. It has been suggested that

Larach à Chrotail may have served as a collection point for lichens for use by local communities in times past. These forests, which ran through the western and central highlands, were home to many plants, whose roots, bark, berries or leaves could produce a range of colours. Lichens were amongst the most useful of these, and two groups of them, known in Gaelic as

crotal and

corcur, were associated with specific colours,

crotal described above and

corcur which could produce a range of red to violet and purple shades (

Figure 2). These were related to an imported dyestuff known as orchil, well known in Europe for dyeing purple on wool and silk [

1] (pp. 485–549). In Scotland, it was also known in the form of a prepared dyestuff named ‘corklitt’ or ‘korklit’ from the noun

corcur and

lit or

litt, a verb meaning to dye in the Scots language, and also in other parts of northern Europe [

2]. Its local use was noticed by Andrew Symson in his history of Galloway (in south-west Scotland) in 1684.

“In the parish of Monnygaffe, there is ane excrescence which is gotten off the Craigs there, which the countrey people make up into balls; but the way of making them I know not; this they call cork-lit, and make use thereof for litting or dying a kind of purple colour”.

It appears that George and Cuthbert Gordon were familiar with this tradition, coming from a Banffshire farming family in north-east Scotland. Apparently, while working at a London dye house, George Gordon noticed how close the preparation of orchil dyes was to those in Scotland. In the mid-18th century, imported lichens from the Canary Islands and the Cape Verde Islands were costly, particularly in times of war when supplies were interrupted. The plans of the Gordon brothers had also been temporarily interrupted as they waited in London for a ship to Antigua to visit a wealthy uncle, also George Gordon, who traded in tobacco in Virginia. Whether growing or importing tobacco was intended to be their principal occupation, early family letters reveal that the younger George Gordon was already planning to collect

corcur lichens in Scotland, sell them to the London orchil makers for a profit, and to use the money to begin a manufacture of purple dye himself [

4].

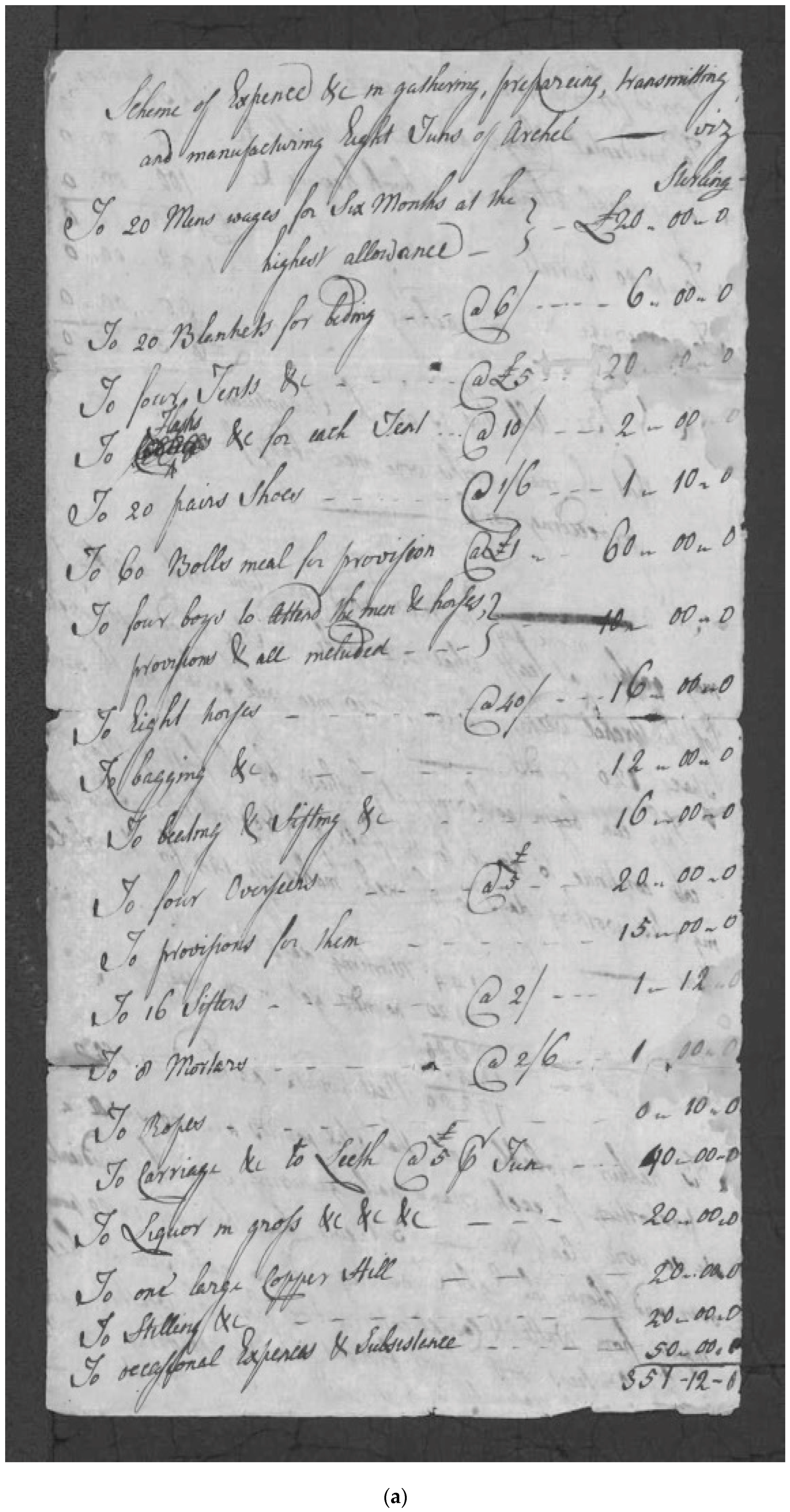

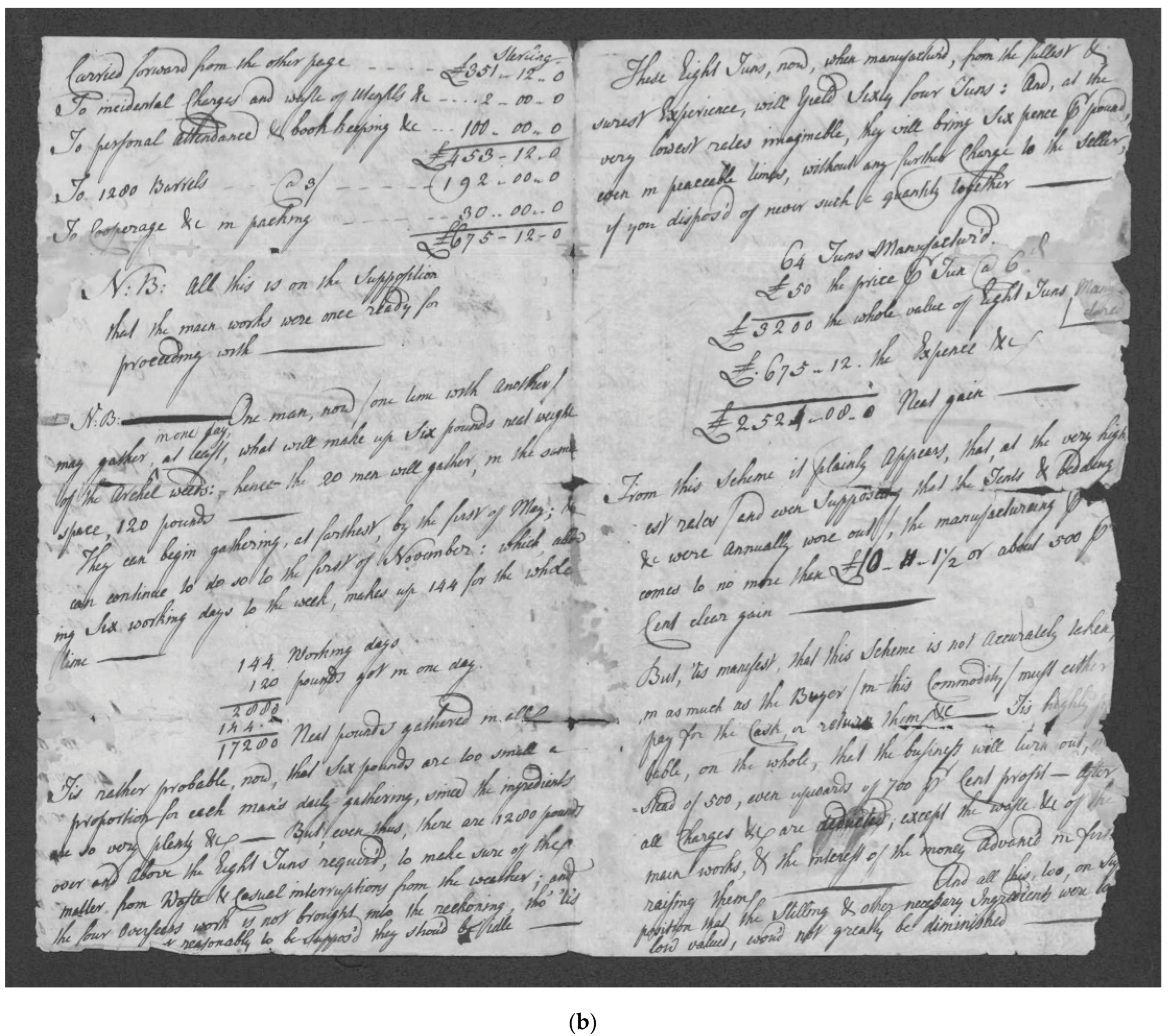

To ensure a steady supply of lichens, the brothers applied to the Board of Commissioners for the Annexed Estates, the sequestered estates of Scots who had been supporters of the Jacobite risings in the 1740s, to take leases of several Highland farms where the soil was poor and where lichens were plentiful. Described as a project of improvement, they undertook this venture at their own risk, and if successful, planned to take on more farms after four years. In return, they would be allowed all the profits from the business for the following eleven years [

5]. A recently discovered “Scheme of Expense etc in gathering, preparing, transmitting and manufacturing Eight Tuns of Archel” (orchil), not dated but probably circa 1757, gives much information about how this business would be organised (

Figure 3). It details projected costs and expected profits. Amongst the lowest costs were wages for twenty men working “for Six Months at the highest allowance £20 Sterling”. In good weather and accounting for wastage of materials, it was estimated that one man could collect 6 lbs of real weight of lichens in a day. A team of twenty men working six days a week could collect 720 lbs of lichens, at least, and working from May until the first of November, they would be able to collect nearly eight tons of lichens. This would amount to 64 tons when manufactured into a dyestuff now to be called Cudbear. The collectors were to be housed in tents during the summer months, gathering lichens from boulders and from older specimens of oak and birch trees in mountainous areas and forests, which were often impassable. Horses would transport equipment and provisions and also carry the bags of harvested lichens back to the Leith manufactory at £ 5 Sterling a ton. Listed in the expenses are a number of ‘Sifters’ and ‘Mortars’, which suggest some preparation of the collected plants, though whether any of this was to take place at various collecting points before the lichens were delivered to the manufactory is not clear [

6]. Also included was the cost of 1280 barrels at three shillings per barrel, probably to contain the finished Cudbear dye in Leith. The brothers spent a year experimenting with combinations of lichens, trying out the results with dyers in Aberdeen, who thought the colours they obtained were better than those from the imported orchil. This encouraged them to move ahead with plans to manufacture the dye themselves.

2. The Dye Works in Leith

To raise money for the manufacture, the Gordon brothers formed a partnership with their uncle in Maryland and an Edinburgh merchant and banking house, William Alexander and Sons. It is said that Messrs Alexander purchased land to erect specific buildings for the dye works based at the Yard Heads at the foot of Leith Walk, Port of Leith, near Edinburgh. Cuthbert and George applied for a patent in 1758 to protect their dye, which they named Cudbear, with production having started the previous year. The patent set out the method for obtaining the dye from a mixture of three local lichens. These were only partially described but were principally

Lecanora tartarea (Ochrolechia tartarea L. Massal), with the other two later identified as

Cladonia pyxidata and

Lecanora calcarea [

7].

“…When these three Ingredients are gathered, cleanse them from all their filth, by laying them severally in cold water, changing the water daily so long as any filth remains about them. Then dry and pound them in a mortar and dilute them with the spirit of urine & spirit of soot, to which add quick lime. Digest them together for fourteen days, and they will produce the Cudbear fitt for Dyers use. A more solid kind of which may be obtained by continued Digestion of the several Ingredients for fourteen days more when it will grow into a kind of paste and harden like Indigo …”

The dye was sold either moist in sealed casks or after longer steeping as a ground powder. In its solid state, Cudbear was not unlike the corcur used in Ireland and described by the botanist William Withering in 1801:

“It dies wool of a brown reddish colour, or a dull but durable crimson or purple, paler but more lasting than that of Orchil. It is prepared by the country people in Ireland by steeping it in stale urine, adding a little salt to it, and making it up into balls with lime. Wool dyed with it and then dipped in the blue vat becomes of a beautiful purple …”

In Scottish accounts, corklit is often mentioned in association with indigo dye. It could reduce costs by cutting down the amount of indigo needed to produce a dark blue shade. It was also used to counteract the greenish tinge which indigo sometimes displayed.

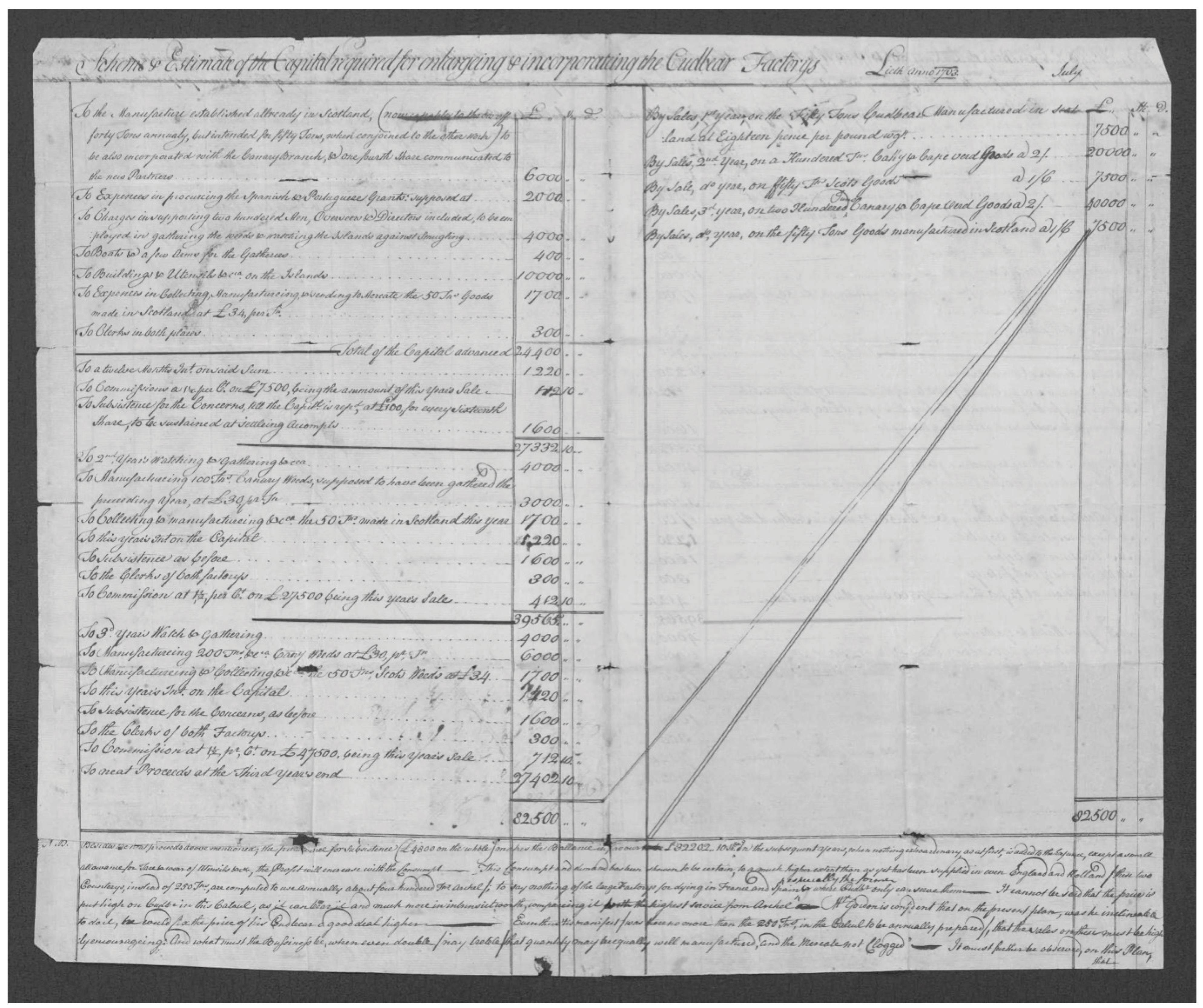

It seems the Scottish lichens were plentiful enough for Cudbear to achieve early commercial success, and anticipating a larger market, the partners drew up a second proposal in 1763, entitled a ‘Scheme & Estimate of the Capital required for enlarging & incorporating the Cudbear Factorys’ [

9] (

Figure 4). This was a three-year plan which recommended the creation of a new company and the combination of two sources of lichens, fifty tons from Scotland annually and one hundred increasing to two hundred tons from the Canaries and Cape Verde islands. It was likely that the lichens coming from the islands were species of

Roccella, the fruticose lichens often known

as ‘weeds’, as opposed to the

Lecanora lichens, the crustose form common in Scotland. The sourcing of these lichens would put the Gordon brothers into direct competition with well-established dealers in orchil in Europe, and later accounts record Cuthbert’s struggles with these merchants. The plan included both a Scottish factory and what was described as the ‘Canary factory’, a much larger venture than their original business. Expenses included a large sum for buildings and utensils as well as costs “To Charges in supporting two hundred Men, Overseers & Directors included to be employed in gathering the weeds & watching the Islands against smuggling—£4.000”. This was a significant investment and it is not clear how many of the men would have been islanders or enslaved people, nor whether the overseers and directors would have been Scots based there, but £ 400 Sterling was set aside for “Boats & a few Arms for the Gatherers”. In the view of the partners, there was an untapped future demand for Cudbear—England and Holland were using at least 440 tons of Archel (orchil) annually, “to say nothing of the large Factory’s for dying in France and Spain especially the former where Cudr (Cudbear) only can serve them”.

A letter published in the London Chronicle, dated 4–7 May 1765 written by a dyer to his customer, a clothier, claimed Cudbear to be a valuable invention which would be of great benefit to British wool manufacturers overseas. Comparing it to orchil, he wrote the following:

“When I use it for rousing blues, I have a finer colour, and I save at least as much Indigo as I save by using Orchill; add to this that Orchill gives no standing colour, whereas Cudbear strieks (sic) a variety of beautiful pinks, purples &c. I at first lost too much time in pounding it, but now I find that all I have to do is order my servants at night to pour some warm water upon the quantity which I am to use next day and I have it in a liquid state next morning”.

He also claimed that in solid or powdered form, Cudbear preserved its dyeing qualities for several years, while orchil was susceptible to rot. How much investment this project attracted is not clear, nor how far it was able to proceed, for George Gordon died suddenly in Leith in 1764, and when the Cudbear patent expired in 1772, the company was found to be in debt. William Alexander and Sons tried to sequester the buildings and equipment of the works in Leith, though the bank subsequently collapsed, and Cuthbert, who had continued to manage the works himself, was obliged to declare bankruptcy [

11,

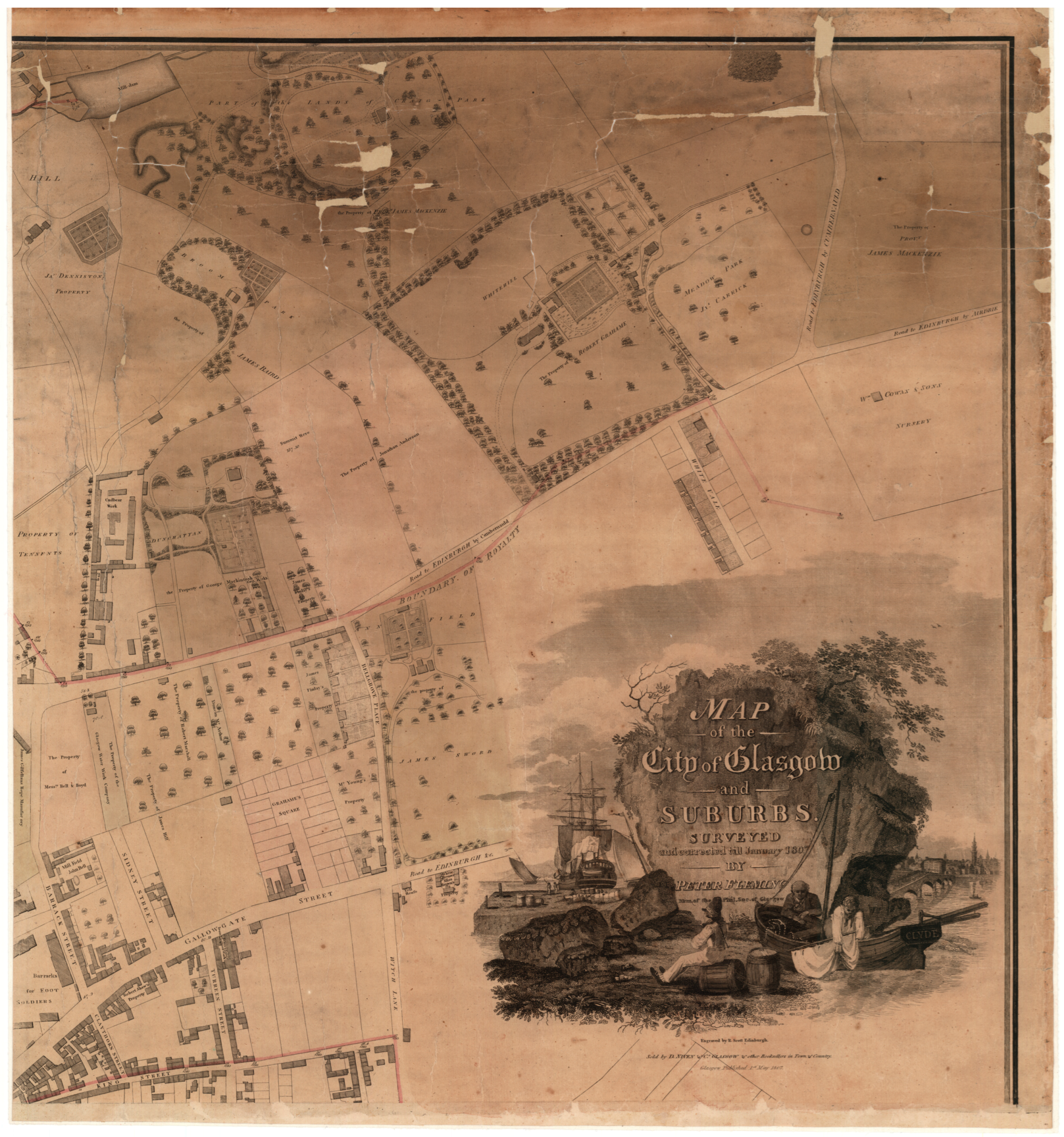

12]. Despite this setback a group of merchants with Atlantic trading connections in Glasgow were prepared to put up sufficient capital to form a new partnership which included John Glassford, John Robertson and George Macintosh, all with well-established businesses in the city. Also involved was the dyer, Adam Grant, Cuthbert Gordon himself, as a consultant, and a younger brother James.

4. Later Experiments on Dye Plants—Reds, Blacks and Drabs

Although Cuthbert Gordon was associated with the new Cudbear works as a consultant, he did not derive any financial benefit from the expansion of the manufacture. The market for Cudbear, however, prompted him to look at other native plants which historically had produced stable colours. He later wrote of his belief that most if not all indigenous plants were capable of producing colours or capable of improvement by cultivation in the soil and climate of Great Britain. Using the classification system of Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, the French botanist and widely travelled collector of plants, for reference, he began a series of experiments on plants which he hoped to find useful for the British economy [

15].

From the 1750s, there was renewed interest in cultivating madder and woad as substitutes for imported madder and indigo. Scientific and agricultural bodies then active in London, Dublin and Edinburgh offered prizes for raising madder. For example, in 1756, the Select Society in Edinburgh awarded £3 Sterling to Archibald Malcolm, a surgeon in Dalkeith in Midlothian, for “the greatest quantity of madder, not under ten pound weight, dressed and cured for the market”. When tried by dyers, it was judged to be as good as the high-quality madder then imported in large quantities from Holland [

16]. Cuthbert Gordon’s own interest was in

Galium verum as a substitute for madder, a plant which he claimed was both plentiful in the wild and capable of cultivation.

“The rearing of it, therefore, to supply the demands of Trade besides producing a cheap and elegant substitute for Madder, which takes from us yearly some hundred thousand pounds in favour of the Dutch, it would be the means of employing thousands of our indigent fellow Subjects, and enabling them to subsist by an honest and useful industry”.

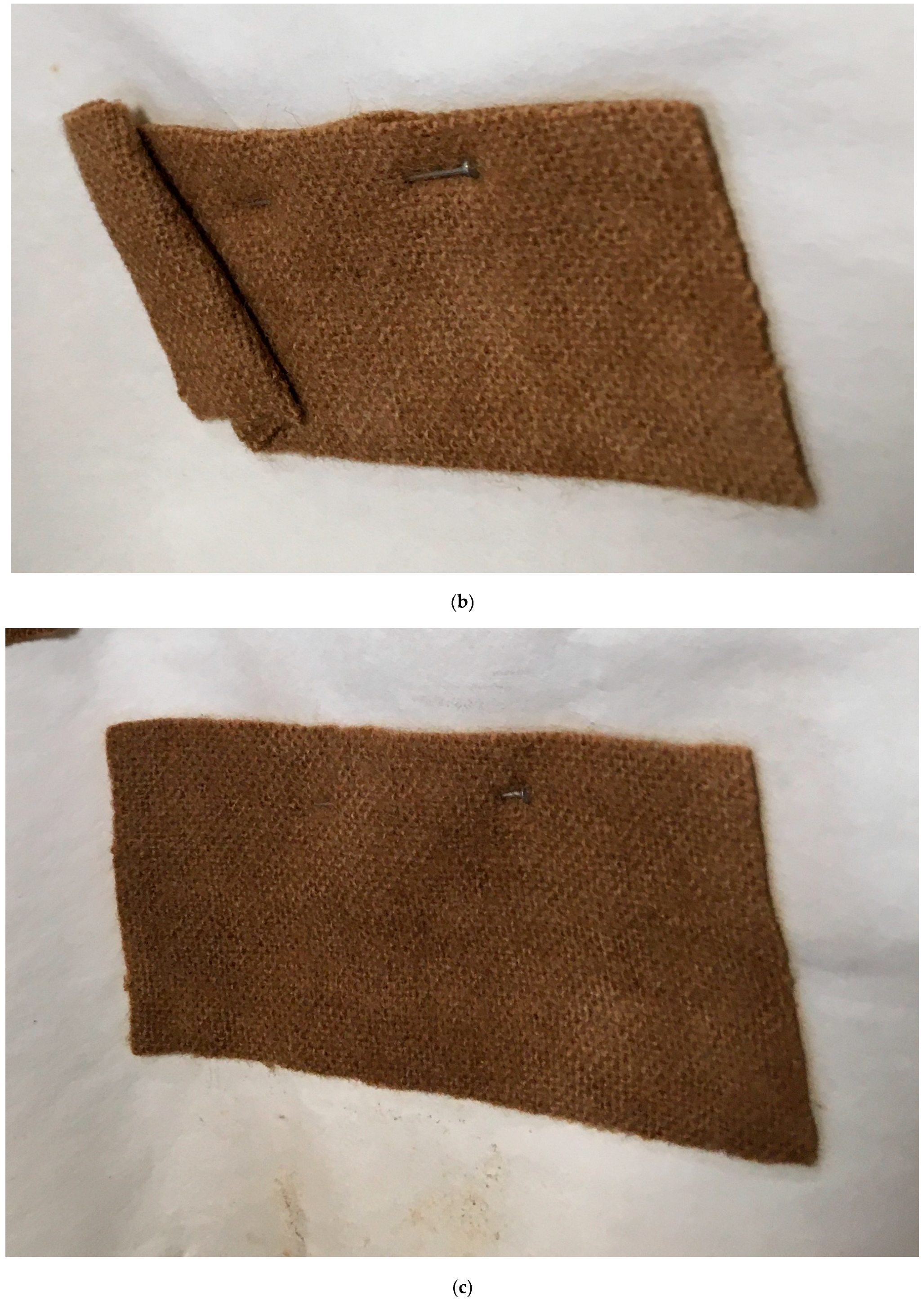

Gordon directed experiments at Nursery Grounds in Bow in Middlesex and Stockwell in Surrey, both near London, which proved promising, anticipating a yield of upwards of three tons weight per acre of cultivated plants, their roots ‘upwards of a foot in length, and about the thickness of a crow’s quill’ in the first year of growth [

18]. Samples of dyed wool have survived in a letter to the Lords of the Committee of Privy Council for Trade which shows the results of trials on

Galium compared to the colours of madder and cochineal (

Figure 6). The first pair of colours compares the red of

Galium with madder on coarse cloth, used for soldiers’ uniforms. The second pair compares

Galium with the ‘scarlet of cochineal’ both on superfine cloth. The colours from

Galium are unfaded (having been stored away from light) and are clear and bright red, the madder on the coarse-milled cloth being red with a brownish tinge, and the cochineal on the fine cloth being red with a crimson tinge. All were passed through a soap scour after dyeing. Gordon’s own note claims that the

Galium retained its beauty and lustre in comparison to cochineal. However he also commented that in early trials, he added ‘certain quantities’ of Red Saunders to the

Galium, and it is not clear whether he continued to use both in the final dyestuff. Red Saunders, also known as Red Sandalwood, was an imported insoluble redwood dye which was more light fast and resistant to soaping than for example brazilwood and may have been added to the dye bath to improve fastness [

1] (pp. 289).

Gordon had earlier turned his attention to the difficulty of obtaining a fast bright red on linen or cotton using Cudbear, convinced that it could be modified to produce a scarlet red on vegetable substances.

“This last property in Cudbear viz. the being Capable to have its parts so modified as to strike on vegetable Substances, I only found out of Late when attempting to concentrate its colouring particles in order to be able to stand the Action of the Aq R (Aqua Regia) and Tin, and thus produce a Scarlet—The Scarlet indeed I have not found, but sure I am it is there; and somebody will find it to be so, though perhaps it may escape my researches, as the other property has done for these Two and Twenty years past; for so long have I had the Subject under my Eye”.

This was eventually found, not on Cudbear but with madder and initially with the assistance of a French dyer brought to Glasgow by George MacIntosh. Under the name of Turkey Red, it was used extensively on plain-weave calico, spun and woven by George Macintosh and David Dale for the Scottish printfields and for export. The results of Cuthbert Gordon’s own experiments with Cudbear on cotton were gathered together in a series of sample books which apparently contained many hundreds of “beautiful and elegant dyes all struck upon cotton”. If in fact they were finished, these samples would have revealed some of the difficulties dyers faced while attempting to achieve ‘fixed’ colours on vegetable fibres so early in the expansion of the cotton trade, but they have not so far been traced.

Perhaps one of his most interesting series of trials was carried out on black wool, which was often complained about in England for its brownish or rusty hue and compared poorly to the blacks of France and Holland. This ‘New Black’, as Gordon called it, was dyed with a native lichen or ‘moss’ upon a deep blue foundation. The plant is not named, but described as ‘The substance employed chiefly in striking the Black, is a Species of the Lichens. It abounds almost everywhere, and can always be had at pleasure with little other trouble than that of collecting it’, the resulting dye a ‘mild vegetable tincture, unassisted by the addition of any corrosive ingredient whatever’ [

17,

20]. Twelve small samples in

Figure 7 show an example of it at the top left compared with the best French black commissioned for the experiment to the right. The recipe is not given, but an admired contemporary French black included logwood and sumac on an indigo base. Part of each sample was also treated by boiling for three minutes with half an ounce of alum in half a pint of pure water after dyeing. Below are samples of the best English blacks in current use on dressed and undressed cloth. The English dyer James Haigh, author of

The Dyers Assistant, described the difficulty of dyeing black without damaging the cloth and quoted one of the best and most lively English blacks made with logwood, elder bark, sumac and copperas [

21]. The bottom two samples show the different shades possible with the New Black. When this dye was trialled by groups of clothiers in the principal wool manufacturing areas of Britain, however, there were some reservations. Merchants in Leeds agreed that the blacks were fixed and permanent “but the Colour scarcely so good, and the Expense more than double”, which meant that it was not profitable to use on coarse goods. They also called for further experiments to determine if the dye would work for higher-quality worsteds. However a testimonial from Messrs Desanges and Mills in London was more enthusiastic: “Dr Gordon’s Discovery in the article of fixed Blacks, conjoined with the superior fabrication of English Cloths, will make the Manufactures of England unrivalled in Foreign Markets”. Their charges for dyeing black on superfine cloth were one shilling per yard for a colour which was not fixed, and one shilling and eight pence a yard for a fixed black [

22]. A contemporary example of the corrosion, which occurred on black yarn dyed with an iron mordant, is shown on a mid-18th-century Axminster carpet (

Figure 8) at Dumfries House, Ayrshire [

23].

Gordon had initially selected the lichen which he had used for blacks, for compound colours known as ‘drabs’. These were a large class of intermediate shades which were very commonly used, for “they make a much greater part of the wear of all ranks of people than all the other colours put together”. Drabs were colours lacking in brightness which did not require much dye but were often made from a palette of cheaper dyestuffs, some of which were not fast. Gordon claimed that his drab shades had a fullness and fixity of colour, which in present practice could not be achieved, especially in the gradations of shades he was able to produce. They are often found in nineteenth-century furnishings, particularly carpets [

24]. Annette Kok, in her

Short History of Orchil Dyes, describes several drab recipes from a dyers’ pattern book of carpet wools dating from the mid-19th century which were used by David Hindley in Yorkshire, all including Cudbear. One of them, called ‘oak’, was a light pink-brown shade, using fustic, madder, Cudbear and copperas, and another, was mauvish-grey in tone, with alum, logwood and Cudbear [

25]. Other surviving yarn sample books show that Cudbear was widely used on Scotch carpets, a popular flat-weave floor covering in which detailed designs could be built up by using coarse multi-coloured weft yarns where single threads of different colours were placed together across the carpet.

“…the weaver has often a warp of two colours only, such as white and maroon: across the white he may throw white, drab, fawn, light-green, and yellow, to form a fancy or shaded ground. With the maroon warp he may use two or three different shades of weft consisting of full greens, scarlets, crimsons, blues and olives …”

These carpets remained popular well into the twentieth century and have been recreated in historic houses in Britain and particularly in the United States. The modern example in

Figure 9 shows typical lichen colours such as warm brown drabs and pale mauve and pink, although woven with synthetic dyes. The design is based on an early Victorian carpet, also shown, made by the Louth Carpet Manufactory in Lincolnshire. A second surviving fragment of carpet from this company shows drab shades highlighted with a narrow stripe of the more expensive scarlet (

Figure 10). A later grey shade on a fine wool twill for a dress, shown in James Napier’s

A Manual of Dyeing and Dyeing Receipts, was made using alum, tartar, indigo extract, Perkin’s mauve, cochineal, Cudbear and fustic [

27].

Drab shades taken from commonly found lichens, plant roots and tree bark shown in Professor Patterson’s sample book of 1917 were still in use by the rural population in the Scottish Highlands at that time. In an accompanying typescript,

‘The Dyeing Properties of Some Scottish Lichens and of a Few other Materials’, Patterson compared the shades he was able to produce in the laboratory to the colours associated with those plants in the countryside [

28]. His samples were small, in some cases 5 g, and the material was given a brief cleansing and then boiled for up to five hours in an ammoniacal solution. The root of the Ash tree gave a greyish shade, Alder bark (‘a fairly dark brownish-green’), but on the sample itself, Patterson commented, ‘said to dye black with copperas’. Birch bark gave ‘a warm brown shade’, and on the sample, he wrote ‘said to dye Fawn’. Amongst the roots of plants were common Dock, ‘quite a satisfactory warm brown’, and Bramble root, ‘a somewhat lighter brown’, on which he commented ‘said to dye Yellow’. Iris root gave ‘a colder brown’ and was ‘said to be used in the Hebrides as a grey dye’. Bracken root gave ‘a rather greenish fawn colour’ but was ‘said to dye yellow’ (

Figure 11). Most of Patterson’s samples were obtained from an expedition to the central highlands to look for colour-producing lichens undertaken by Edward Stewart, Fellow of the Botanical Society of Edinburgh, in the summer of 1916, part of a government enquiry into the restoration of rural crafts to the Highlands and Islands at a time of high levels of depopulation [

29]. Stewart’s ‘

Notes on Occurrence and Distribution in Scotland of Dye-producing Lichens. Supplementary to Report on Occurrence of Lecanora tartarea Ach.’ which accompanies Patterson’s sample book describes many lichens capable of producing the drab shades, classifying the plants variously as plentiful and easy to obtain, those that might be gathered but not in commercial quantities, and those where there was not enough to consider collection [

30]. The habitats of these plants were also recorded.

5. Discussion

The value of Cudbear lay in the palette of shades from reds to purples, vivid pinks and lilacs which, although not truly light fast, could invigorate and reduce the cost of imported colours. Adam Grant and William Young, Deacons of the Incorporation of Dyers in Glasgow, found in December 1779 that three pounds of indigo at 7 shillings per pound dyed 48 yards of cloth ‘a good deep blue’, but two pounds of indigo with a penny worth of Cudbear to each yard saved the dyer fifteen per cent of his costs and dyed the cloth ‘equally deep, and much more beautiful, or of a finer lustre’ [

31]. The results of the experiment were recorded under oath before the Lord Provost in 1788, which suggests that the tests were accurate. The lustre and depth of colour of Cudbear dye are often commented on in contemporary accounts. Complex shades could be created from one plant source, whereas traditional purples and mauves called for mixtures of red and blue dyes, of which indigo and cochineal were by far the most expensive. It could be used without a mordant and was consequently less damaging to the finished cloth in combination with other dyes. This was useful on silks, which were easily damaged, and to create pale shades, more difficult to produce with a lively and even hue. When dyers began to publish their recipes, the ‘prejudices of the practical dyers giving way by degrees’, as Cuthbert Gordon recorded, they often described more than one way of producing a colour, one fast and the second more fugitive according to the cost constraints and the quality of the goods required. Cornelius Molony’s book of dyeing recipes written in the 1830s without the Least Reserve, according to his Practice in Great Britain and America, advertised both a ‘Permanent Lavender’ using an indigo vat and cochineal and ‘Another Lavender’, which was not fast but included Cudbear, suitable for cheaper qualities of cloth [

32]. Later, Antonio Sansone, in his 1888 book on dyeing, showed samples of fine purple wool flannel, which still included Cudbear, dyed by J Marshall and Sons in Leeds, where the Cudbear manufacture is remembered in the name Cudbear Street [

33].

In 1785 nearly thirty years after the patent for Cudbear had been granted, Cuthbert Gordon petitioned the Lords of the Committee of Privy Council for recognition and for support to continue his studies on native British plants. Later, in his “

Brief Statement of Dr. Gordon’s Discoveries in Dying Fixed Colours”, he acknowledged a government reward of £200 Sterling for his work on Cudbear. Included in his memorial were testimonials from leading wool, cotton, linen and silk manufacturers who had been present at experiments he had carried out in person on other plants with tinctorial properties in visits to the major manufacturing districts in Britain. Wool merchants and clothiers in particular were persuaded that he would be able to make further discoveries with public support and called for him to be appointed an inspector of dyes to go from county to county to superintend and instruct manufacturers in the use of new dyes, especially those for fine wool [

34]. Despite many petitions of support, this idea was not taken up, perhaps because of the natural reluctance of dyers to adapt their working recipes, and also because of the dramatic growth of the British cotton industry and the demand for printed cottons in the late 18th century.

In the search for innovation, however, investigations continued on Cudbear in the hope that it might be modified to replace quantities of cochineal in recipes for a fast red. William Wilson and Son, prominent tartan manufacturers based in Bannockburn in the Scottish Borders, were regular customers of George MacIntosh and Co in Glasgow in the early nineteenth century. Their business papers record many receipts for orders of ‘common Cudbear’ at 3/6d per lb, not always found to be of reliable quality. This may have been used in dyes for travelling blankets, coverlets and Scotch carpets, which Wilson manufactured as well as fine tartans. MacIntosh also supplied large quantities of a more expensive ‘Scarlet Cudbear’ at around 5/- per lb, which Wilson initially found difficult to use. A letter in August 1819 urged them to try the dye again, claiming that though the shade was different from a previous order, it contained more colouring matter and would therefore be more advantageous to their customers. They suggested, “perhaps in working; it may require a little more spirits our proof trials were made for 100 lbs cloth, 27 parts dye, 20 spirits (Sulpho muriate Tin) and 15 Tartar, which give a full Scarlet”. This interesting exchange between the dyer and manufacturer suggests a continuing and active experimental approach to the development of new colours [

35]. MacIntosh and Co were also able to supply prepared Lac at 6/-per lb as an alternative red for fine woollen goods. It is noteworthy that George MacIntosh himself had been in regular correspondence with Joseph Black, Professor of Medicine and Chemistry at the University of Edinburgh, during trials to find a fixed and bright red dye on cotton and linen in the 1780s, even sending him samples of cloth which he had attempted to print with Cudbear [

36]. His son Charles, who was a colleague of Cuthbert Gordon, later became a celebrated manufacturer of chemicals in Glasgow. Gordon was awarded an MD from the University of Aberdeen in 1785, and although this may have been more of an administrative gesture on the part of the University, he used his title to urge dyers to experiment in their practice and to stress the importance of chemistry to commerce, a significant aspect of the ‘practical enlightenment’ then sweeping across Scotland. Surviving correspondence and rare examples of dyed fabric samples from this period alert the curator and conservator to the often slow and challenging process of creating new colours. A study of these sources may prove useful to the experimental archaeologist who wishes to recreate historic colours and to those who are responsible for their storage and exhibition.

In the latter part of the 18th century, the manufacture of Cudbear was attempted in other parts of Britain. No longer protected by a patent, dye works were established in London, Bristol, Manchester and Leeds and continued in Leith and Glasgow, the latter finally closing in 1852 [

37]. Success, however, meant the search for new sources of lichens to supply a buoyant market. In this, George MacIntosh and Co, who had expanded the works in Glasgow, had been aided by a network of colonial merchants trading to the Caribbean and the Americas from Atlantic-facing Scottish ports. As highland sources became depleted, quantities of Scandinavian rock moss, the foliose lichen

Lasallia pustulata (L.) Mérat, temporarily contributed to the supply. In 1825, for example, 839 bags of this lichen were imported into the Port of Leith from Norway and Sweden alone [

38].

Over-harvesting and the cutting and clearing of old trees in subsequent years resulted in the loss of many lichens and their vibrant colours in the temperate rainforest. By the time Edward Stewart embarked on his expedition to the central highlands in 1916, there were doubts about whether the skills of dyeing with lichens and other plants could be revived beyond domestic use. Those lichens which had survived were often in remote and mountainous areas on boulders, which were less likely than trees to be disturbed. He suggested, however, that shepherds might collect them while looking after their sheep, filling special bags which could be deposited in designated collecting places, and even that children could act as collectors in the school holidays. Their colours were still considered distinctive enough to be a recognised and admired feature of the Scottish tweed industry and were rediscovered by those who regretted the over-reliance on synthetic dyes in a highly industrialised textile industry, concerns which we continue to debate today.