Abstract

Geographic Information Systems and the use of thematic maps have become well-established tools in archaeology. However, not all the sectors of archaeology still take advantage of these technologies. One such sector is numismatics, where there are still relatively few works on the implementation of coin spatial databases and the related maps. This can be verified both in academic journals indexed in major scientific databases (such as Scopus, ScienceDirect, and Web of Science) and in broader platforms like Google Scholar. In this paper, in an attempt to begin filling the gap, the methodology and results of the creation of the GIS and the Atlas of Antoniniani in Sicily are presented. The second half of the third century ASD is an interesting period because of the socioeconomic crisis that characterized it. The Atlas serves as a useful tool for providing a fresh new insight into the economy and coin circulation during this time.

1. Introduction

Geographic Information Systems and the Atlas production are consolidated instruments used in recent decades in the archaeological field, because they are great for the cataloguing, the management and the analysis of the data in the sector [1,2,3]. They are able to support each step in the archaeological thinking, research and decision system in the field from the creation of digital catalogues [4], to the analysis and calculation of sensibility archaeological areas [5,6].

However, not every discipline connected to archaeology takes enough advantage from these technologies. This is the case of numismatics. Of course, in the articles and monographs related to the topic, maps are produced and used, but they are not dynamic, digital maps, deriving from spatial databases; instead, they are an “instantaneous” and “static” instrument, used just for visualization. Between maps belonging to this second category, the most diffused are present in the studies concerning the production mints, or they are used with the only scope to list archaeological findings. Consequently, maps are often used as an instrument for the coin visualization, without any type of criticism.

GIS is often used and widely used to produce also static and illustrative maps, however its full potential is in allowing a more analytical and interpretative use of spatial data. In fact GIS, more than improving data visualization gives the opportunity to reuse, share, analyze the data; moreover it facilitates the identification of spatial patterns and relationships between archaeological and environmental elements. In this way, the analytical dimension of GIS helps and supports archaeological reasoning and opens up new opportunities for interdisciplinary research.

There are few papers where the combination of GIS and the analysis of coin distribution is aimed at the intra-site study [7,8,9]. In other studies, GIS is used to analyze monetary discoveries according to stratigraphic sequences [10,11]. Also, there are few studies that use GIS and spatial analysis of coins at territorial scales [12,13].

Moreover, on the internet, there are some interesting interactive digital maps, pointing out that the numismatic world is starting to become aware of the potential of GIS for this discipline. Between these, particularly interesting is the Oxford Roman Economy Project [14], where together with coins and coin hoards, as well many other elements, settlements, and activities of the Roman imperial (between the Republican period and Late Antiquity) economy are georeferenced, shown and quantified in order to find patterns of economic integration, regional specialization and changes in trade networks over time as specified in the works cities in the section of the web site dedicated to the literature produced “Oxford Studies of the on the Roman Economy” (just some examples are [15,16,17]). In this way, the study gives useful information about how the Roman imperial economy worked and changed from the Republican period to Late Antiquity. Another example is the Coinage of the Roman Republic Online project [18,19]; in this case, the portal is simpler compared to the side of the Oxford Project, in fact, it is dedicated only to georeferenced coins, hoard collections and their characteristics. The American Numismatic Society developed the Coin Hoards database [20] (https://coinhoards.org/, accessed on 4 June 2025), is an online resource dedicated to coin hoards (mainly Greek and other coins dated between ca. 650 and 30 BCE). The platform includes mapping tools to visualize findspots and contains information regarding coins’ list, typological descriptions, mints and bibliographical references; this is an online resource dedicated to coin hoards (mainly Greek and other coins dated between ca. 650 and 30 BCE). The platform includes mapping tools to visualize findspots and contains information regarding coins’ list, typological descriptions, mints and bibliographical references. This is a particularly virtuous example since the data are structured and distributed as Linked Open Data. Another interesting project is the FLAME project, which combines a spatial representation of maps with the calculation of finding heatmaps [21] (https://coinage.princeton.edu/). Finally, another webGIS related to coins to be cited is the Sacred Coins project [22,23] on Punic and Neo-Punic coinage.

More commons are instead the already cited “static” maps, even if supported by a rich database, as it happen for the website Monnaies de l’Empire Romain/Roman Imperial Coinage AD 268–276 (https://ric.mom.fr/fr/), where are collected and available for consultation different coin types, with information related to their dating and issue, in particular for the historical period analyzed in this paper.

The use of geoinformatics, in particular through the use of spatial analysis, could also be important to understand the relationships and the economic connectivity between different parts of the Roman Empire. By mapping where coins are found and where they are issued GIS can find patterns of circulation and exchange that show how integrated or isolated provinces are, can reflect economic and military choices or can highlight commercial flows.

The aim of this paper, specifically, is to show the spatial distribution and diffusion of coins of the second half of the third century in Sicily. Moreover, the study aims to demonstrate the potential of GIS to promote a shift from purely descriptive approaches toward more integrated and analytical frameworks.

2. Case Study: The Antoniniani Period

The second half of the third century, before Diocletian’s reign (284–305 A.D.), is considered one of the most troubled periods of the Roman Empire. During that time, the common silver coin was the antoninianus, an alloyed coin introduced by the Roman Emperor Caracalla in 215 A.D., weighing 1/64 of a libra, equivalent to about 5.11 g, originally having a value of two denarii but subject to continuous depreciation of its legal value, weight and metal content. The coin owes its name to the emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, surnamed Caracalla, and it is also defined “radiate” because of the bust of the emperor wearing a radiate crown engraved on its obverse [24,25]. The production of antoniniani was temporarily suspended between 219 and 238 A.D.; from Balbinus and Pupienus’ reign (22 April 238 to 29 July 238 A.D.) they were minted continuously until the reign of Aurelian [25,26]. This Emperor, during the spring of 274 A.D., restored the trimetallic system of gold, silver and bronze giving more importance to his radiate silver coin, the aurelianus or aurelianianus that substituted the antoninianus (its weight equivalent to about 4 g being 1/80 or 1/84 of the Roman libra) [25,27,28,29]. Aurelian’s antoninianus did not result in being very popular as it only circulated in the western part of the Empire until Diocletian’s reform in 294 which introduced a new laureate billion coin, called nummus and a radiate neo-antoniniaus. During the last three decades of the third century, the antoniniani struck before Aurelian’s reform circulated almost until the Tetrarchy (in the first two decades of the fourth century A.D.) together with “radiate imitations”, i.e., regional imitations of official coins, also named “barbarous radiate” (a current detailed bibliography can be found in [25,30]).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Research and Engineering

A large amount of documentation used in this paper comes from historical publications and bibliographic sources, such as journals like AIIN or Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità, monographs or printed catalogues (the complete references are reported in Appendix A). However, most of these sources lack specified stratigraphic sequences. Additionally, a small number of coins that have not yet been listed or are still unpublished are preserved in Museums or Antiquaria. We are conscious that this paper can be enriched with the report of new stray finds or of other coins in Museum or found in archaeological research.

Moreover, third century antoniniani sometimes lose their role as chronological indicators because either they continued circulating for some decades after their being issued or are separated from other archaeological materials thus lacking any contextual information. However, the study of these coins’ circulation could be important to addressing other matters of historical interest, such as the degree of monetization, the use of previous and following currency or the quantification and chronological limits. Thanks to the awareness of the potentials of archaeological contextualization of monetary discoveries, our approach would like to evaluate some data provided by the antoniniani circulating in Sicily.

For the aims of this paper, a spatial database has been created with all the information about different aspects related to the antoniniani in the following fields (Table 1):

Table 1.

Summary diagram of the Antoniniani spatial database.

- Two spatial fields containing the geographic location of the coins. Unfortunately, in many cases detailed coordinates, which would be desirable for GIS-applications, are not available. In fact, there are cases where only very vague information is available and the record refers to the cadastral municipality as find spot, or we should refer to the toponym location.

- The identification number.

- The findspot.

- The toponym.

- The actual Sicilian province.

- The accuracy, in order to indicate whether the coordinates identified are accurate or, as indicated above, refer to a wider area.

- The find type distinguished between survey, archaeological research or stratigraphic context, coin hoard, gift to a museum, private collection or seizure).

- The number of coins. This information is especially important in case of treasures with some coins of the same authority, mint and type.

We have also registered information about:

- The portraits on the Obverse;

- The Reverse type (and if possible, reverse legend);

- The mint;

- The issue; in this field for “barbarous radiates” we have utilized the term “irregular mint”;

- The specific chronology (mint date).

While this database provides a foundation for studying the circulation of Antoniniani in Sicily, it is understood that it represents an ongoing process. As new discoveries are made and further research is conducted, the database can be continually updated to refine our understanding of the economic and historical context of coin use in this period. This approach not only contributes to numismatics but also offers valuable insights into broader archaeological and historical inquiries.

3.2. Kernel Density Estimation (KDE)

For the analysis of the mint distribution, a KDE approach was used. This method is used in very different application fields [31,32,33,34,35,36] as well as in archaeology [5,37,38,39,40]. It allows researchers to obtain a local and smoothed estimate of a probability density for a point pattern distribution. It is defined as a moving three-dimensional function that weights events (points) depending on their mutual and their intensity [32] resumed in expression (1).

In it, k is the kernel, which is the shape of the weighting function; s is the point intensity or a quantity identifying event strength; τ or bandwidth is the most important parameter in KDE and defines the width of the weighting function and consequently also how many events are weighted together. For an in-depth study on KDE, see [41].

In this work, the Epanechnikov kernel was used, in order to limit locally the density estimation, as intensity the number of mint was introduced in the calculation and for the definition of the bandwidth a consolidated method used in the literature is used, the 1st order nearest-neighbor average observed distance between events [41].

4. Results

The analysis of numismatic data about the second half of the third century Sicily in a GIS allowed to visualize and explore different kinds of information with the help of several approaches to management of data and spatial analysis. The generated maps, in addition to showing the spatial distribution of the antoniniani on the island, is useful as analytical tools that aid in the interpretation of patterns and densities that may not be apparent from the raw data alone.

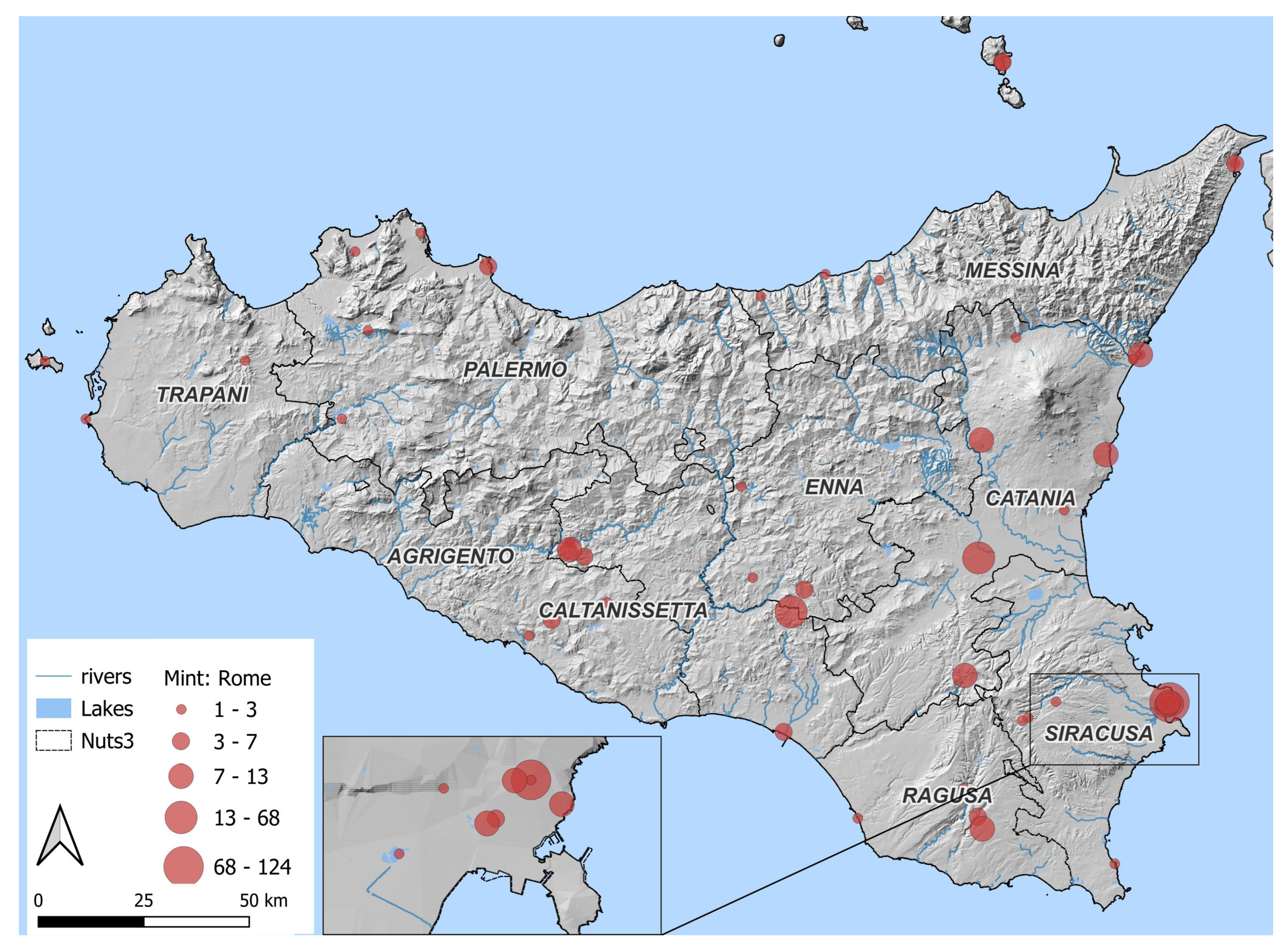

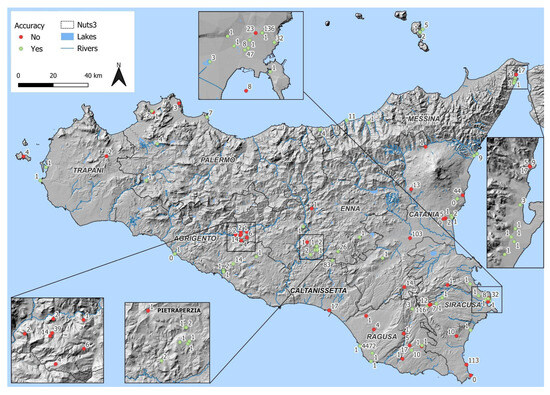

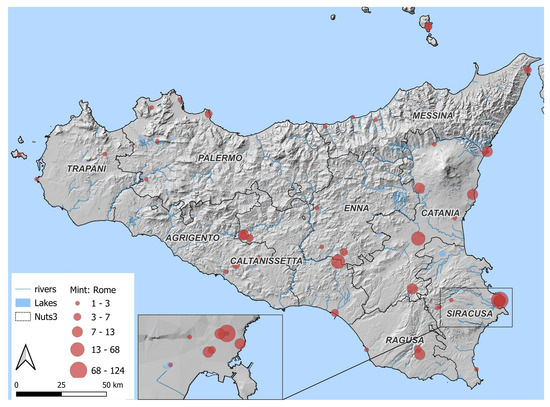

The number of coin finds which have been found in Sicily has a great relevance; the results are 107 sites of finding and a total of 1149 antoniniani found there (Figure 1); in a few cases we have only the report of the antoniniani discovered in archaeological sites but without the total number of specimens or the attribution to an authority. We also add, in the maps, 4472 coins which came from the shipwreck in the bay of Camarina even if this big amount of antonianiani constitutes a special case; it is indeed uncertain where the ship of the “six emperors’ coin hoard” was headed, Sicily or other mediterranean harbors, so his story is different from the other kinds of finding [25].

Figure 1.

Data Accuracy map.

In addition, the data accuracy map enables us to visualize the distribution of findings, concentrated in eastern and central-southern Sicily, especially near Syracuse and Ragusa, along the natural rivers and waterways. These data can offer possibilities to search relations with other archaeological elements, such as infrastructures (e.g., Roman roads) or settlements, and with the topographic features existing in the area and surroundings in a broader interpretative framework. The elevated concentration of coin finds in particular areas could be accounted for by the importance of the places concerned during the second half of the third century.

The first map (Figure 1) distinguishes between accurate and inaccurate data; in particular, it shows how only some records show more accurate information of the place of finding. GIS data are visualized even if we do not have perfect geographic references because the coordinates sometimes are not detailed or they refer to a somewhat vaster area. In the majority of cases, the inaccurate data refer to coins seized or belonging to private collections from the last century; in a few cases, we also consider inaccurate data owing to the absence of particular references to official archeological investigations, even if the area of coin finding, albeit vast, is known.

A more widespread penetration of radiate coins would seem, at the current state of research, to be found in the hinterland of the current provinces of Syracuse and Ragusa and in some investigated archaeological sites of central Sicily as, in particular, in the fourth century Villa Romana del Casale or in the hinterland of Milena (CL). An interesting coin hoard, of 304 AE coins dated from the emperor Adrian to Constantius II, was found in the site of Sofiana, identified as the statio or mansio Philosophiana; it includes over 80 antoniniani, several of which are issued by irregular mints [42,43].

Most of the radiate coins recovered in Syracuse come from the cemeterial area of Vigna Cassia, from the hypogeum Trigilia and from the archeological surveys in Piazza Adda. Palazzolo Acreide (the greek Akrai, in the Iblei mountains) provides an important amount of antoniniani from stratigraphic units. The radiates from the province of Raguse are, unfortunately, in many cases coins from seizures carried out in its territory. For the north-eastern area of the island we can include several specimens from hoards and archaeological excavations in Naxos.

The comparison of chronological distributions of antoniniani provides a more complete overview; however, one is aware that the period of circulation of the coins does not coincide with the time of their issue. Many specimens recovered in Sicilian territory certainly circulated for several decades until the end of the third century A.D., if not even until the following two centuries, as in the case of some antoniniani hoarded together with later coins (e.g., Siracusa–Ortigia, [44] or Naxos [45]).

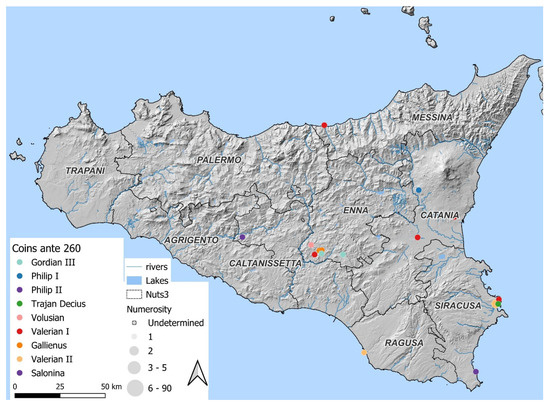

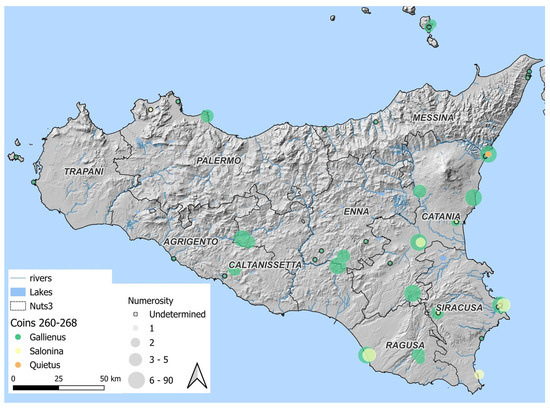

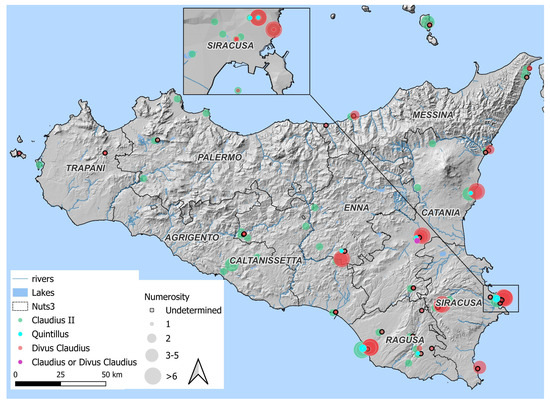

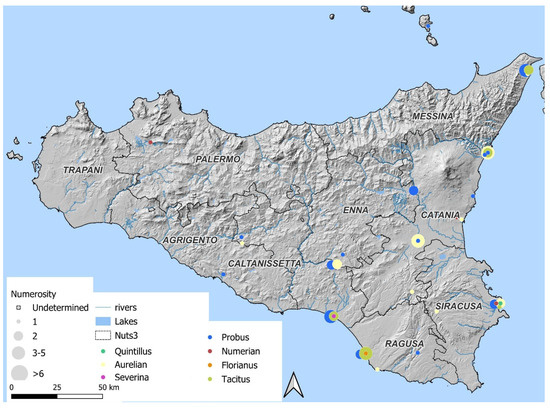

Taking into account the years of issue of antoniniani found so far, and the bust of the authorities on the coins’ obverse, we preferred to identify four chronological periods: before 260 A.D. with only just over ten coins; the years of Gallienus’ sole reign, A.D. 260–268; the period of Claudius II’s reign, including his commemorative antoniniani, A.D. 268–270; post-270 A.D., from Quintillus to Tacitus. The following four maps (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5) let us understand in particular the higher presence, in the island, of antoniniani struck under the sole reign of Gallienus, about two hundreds coins in total, and that of his successor Claudius II Gothicus, with an important diffusion of coins, commemorative of his deification after death. This last group is the most representative of the third century A.D., mainly spread in the area of south-eastern Sicily; we just have to remember again that antoniniani, in Sicily, had to circulate some decades after their minting, probably until the beginning of the following century.

Figure 2.

Coin distribution: ante 260.

Figure 3.

Coin distribution: 260–268.

Figure 4.

Coin distribution: 268–270.

Figure 5.

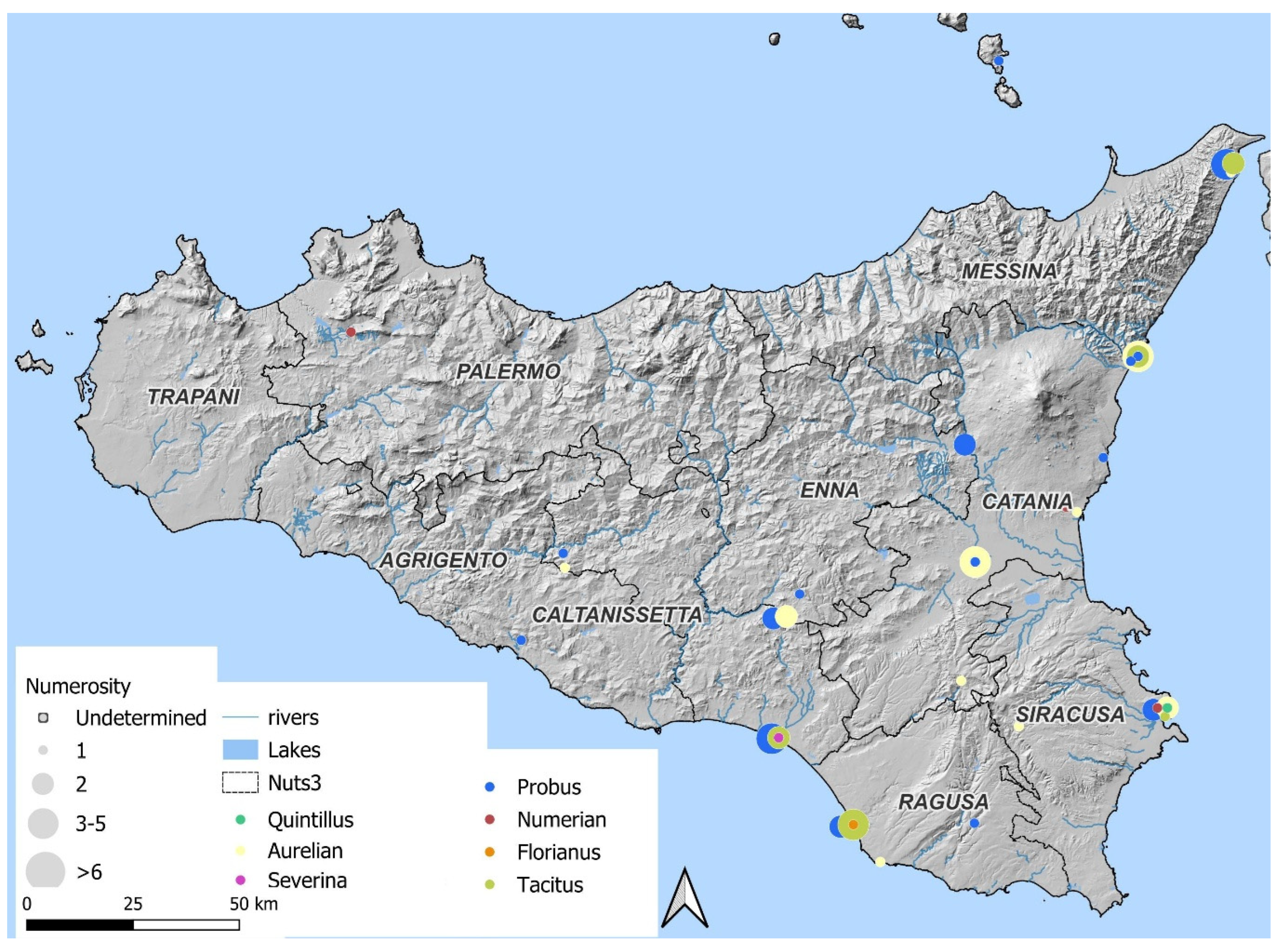

Coin distribution: post 270.

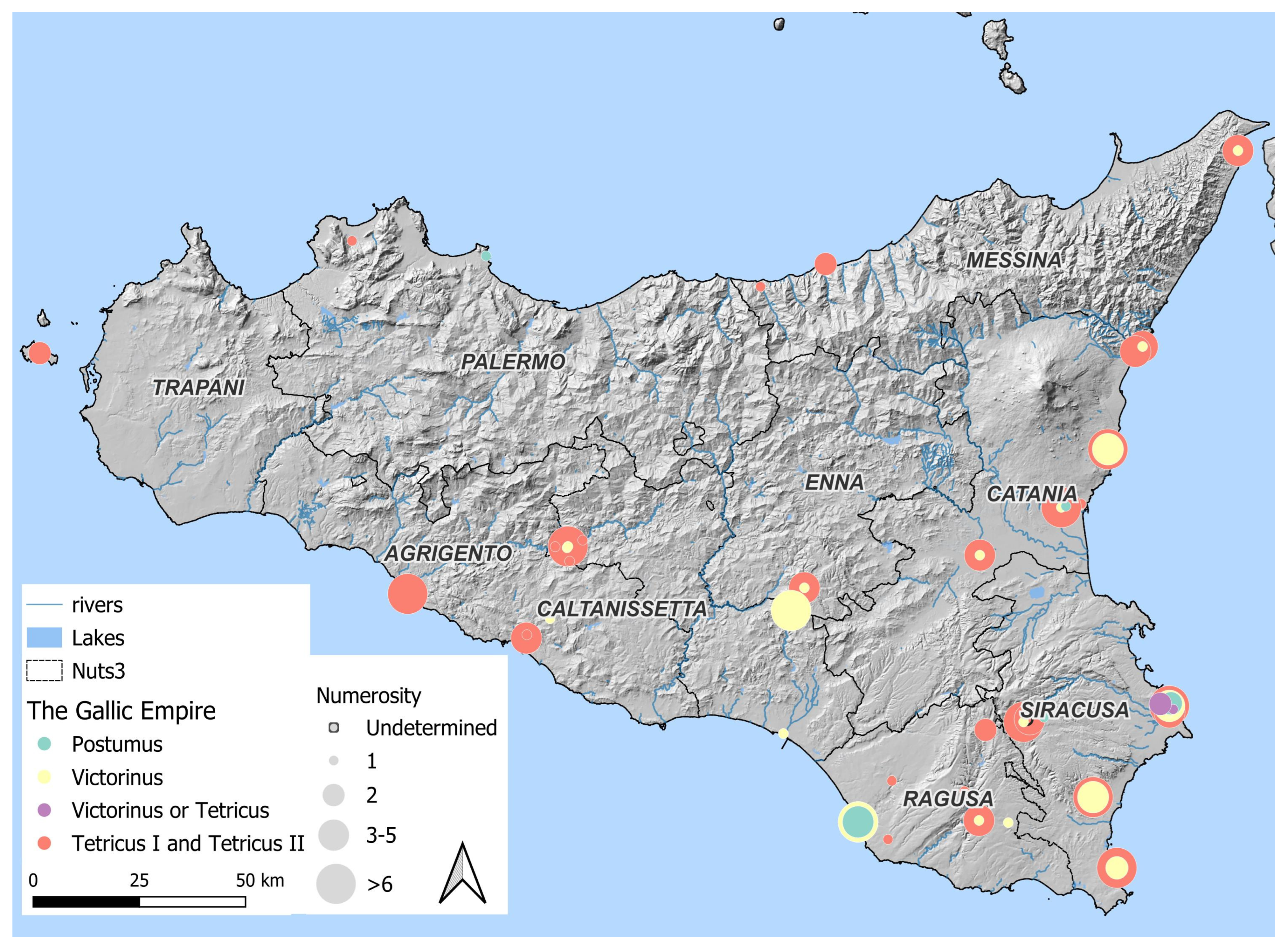

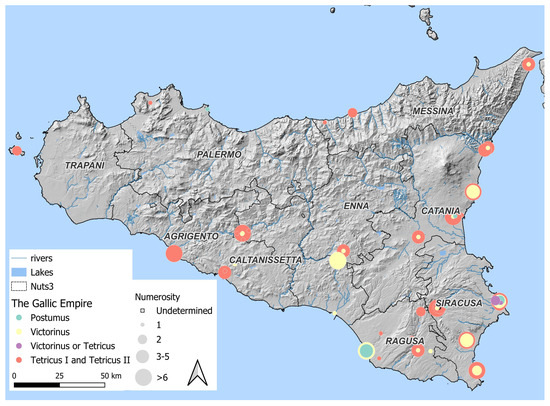

A particular case in Sicily is constituted by the coins minted under the emperors of the Imperium Galliarum (from 260 to 273 A.D.) and the imitations of their types (Figure 6); the few coins with the bust of Postumus (260–268 A.D.) are followed by those of Victorinus (268–271 A.D.) and by the even more numerous ones of the Tetricus I and his son (271–274 A.D.). The area of greatest circulation of the coins of the Gallic Empire coincides with that of the emperors of the Central Empire.

Figure 6.

Coin distribution of the Gallic Empire.

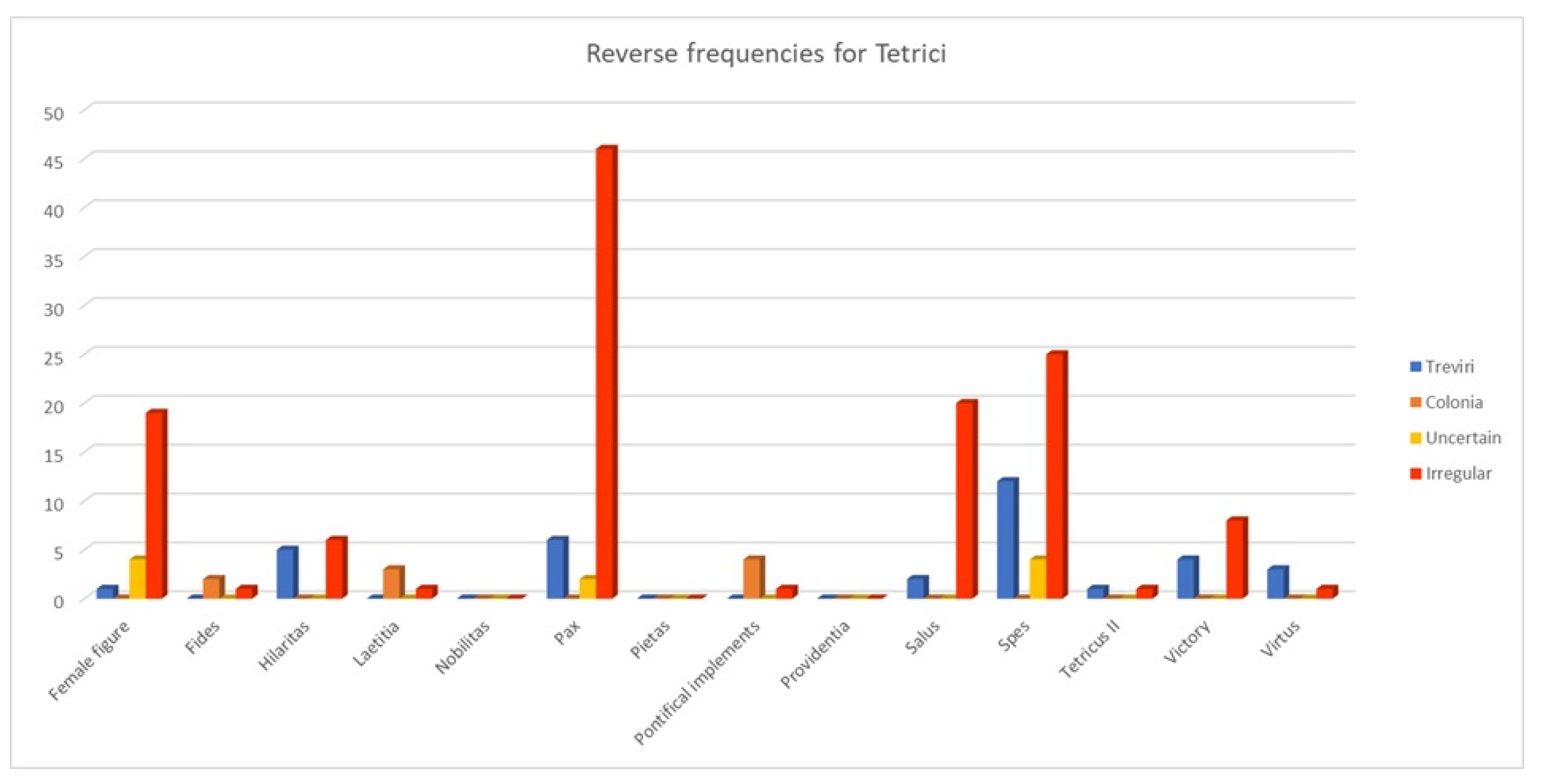

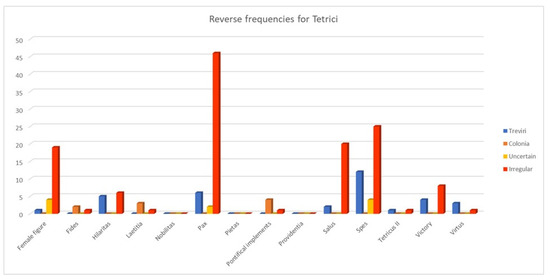

The comparison, by means of a histogram (Figure 7), between the types of the most representative reverses of the Tetrici found on Sicilian territory and issued by the two official mints, Treviri and Colonia (=Cologne), and by irregular mints, provides a more indicative picture of circulation in recent decades of the century. On the island, according to the current state of research and from available data, it would seem that slightly more than half of about 300 antoniniani are imitation coins. This suggests that Sicily may have provided landing points or constituted a transit area for trafficking and vessels from Gaul. A relevant case is the conspicuous number of specimens from the so-called “treasure of the six emperors” found in Camarina (see [30]) not taken in count in the histogram due to his particular specificity. The most representative Reverse’s types of the Gallic usurpers, Pax, Spes and Salus, arrive in far higher percentages than the official issue prototypes (as if to show a precise destination towards this area of the Mediterranean). These types are mostly or almost exclusively imitations of official Tetricus I’s coins struck by the mint of Trier (III–V issues, 272–274 A.D.); it is also noteworthy that the number of barbarous radiates exceeds that of the official coins, as in the case of Pax and Salus.

Figure 7.

Reverse frequencies for the Tetrici’s coins.

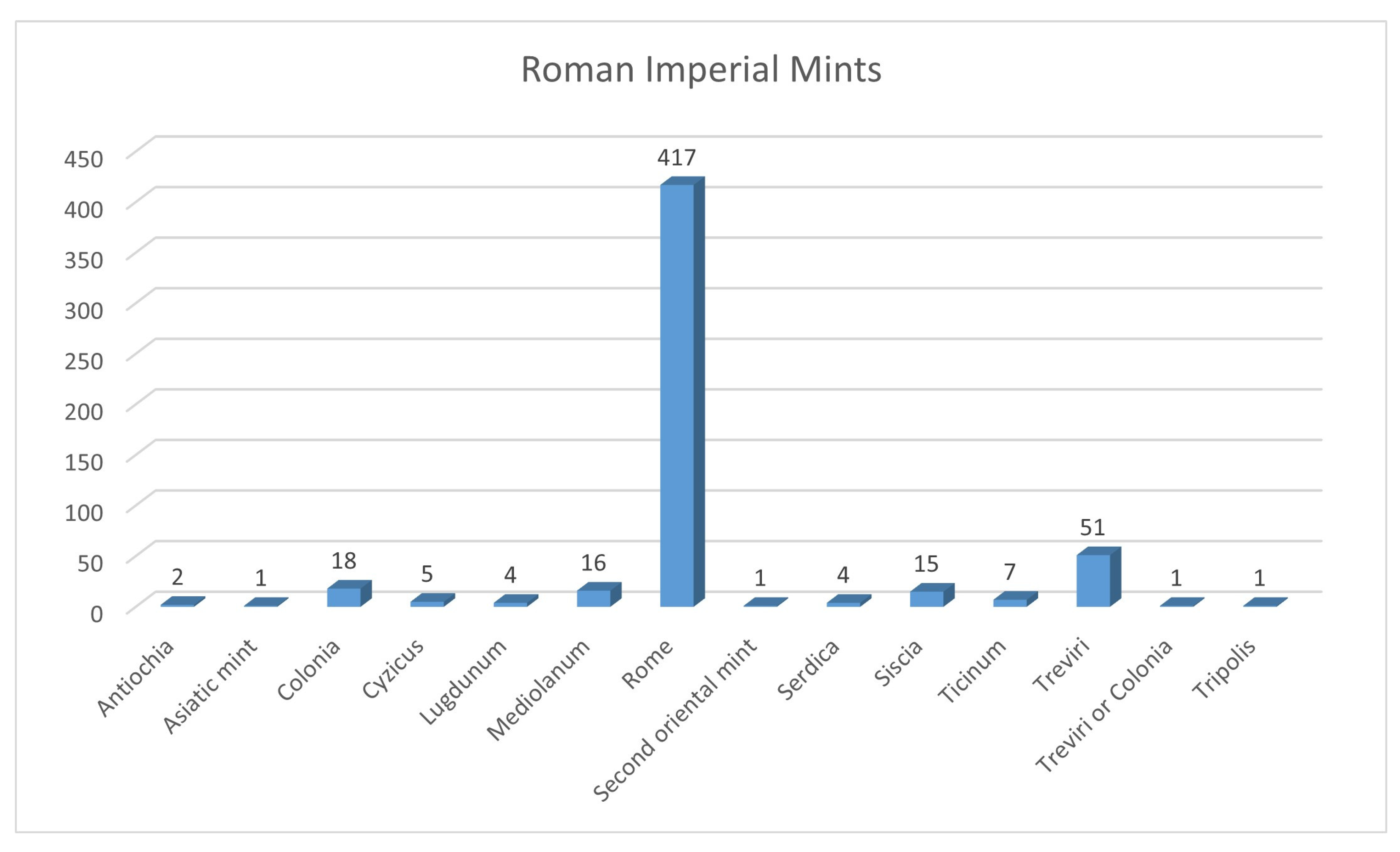

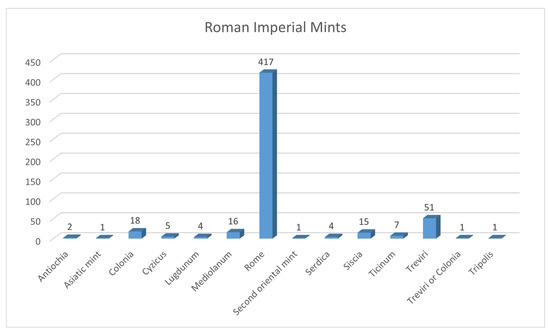

The second histogram (Figure 8) proposed here, relating exclusively to antoniniani struck by official mints of the Empire, helps to better understand the predilection and contacts of the island with particular areas of the Roman Empire, as well as the commercial circuit to which it must have belonged. The relevant percentage of antoniniani issued by the mint of Rome, with 417 specimens, is almost exclusively attributable to issues in the name of Gallienus (260–268) and Claudius II the Gothic (268–270), together with several specimens with the DIVO CLAUDIO legend (post-270 A.D.). Their presence could be noticed, mainly, in the central-southern and eastern areas of the island (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Frequencies for Roman Imperial Mints.

Figure 9.

Coin distribution of the Roman mint coins.

It is also significant the number of issues from the Gallic mints of Colonia and, mostly, Treviri; somewhat insignificant is, conversely, the presence of coins issued by other mints of the Roman Empire, with the sole exclusion of the mints of Mediolanum and Siscia.

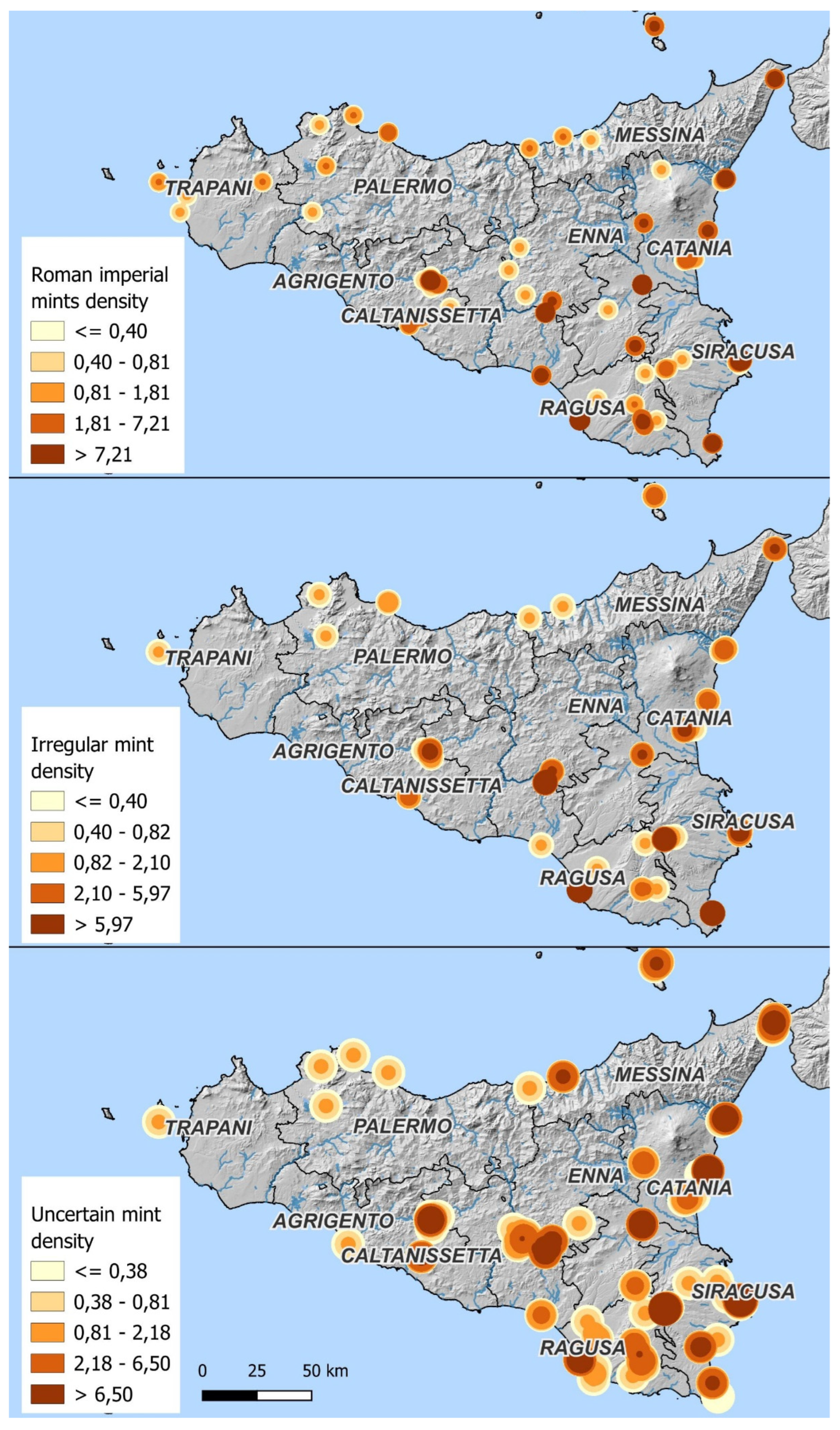

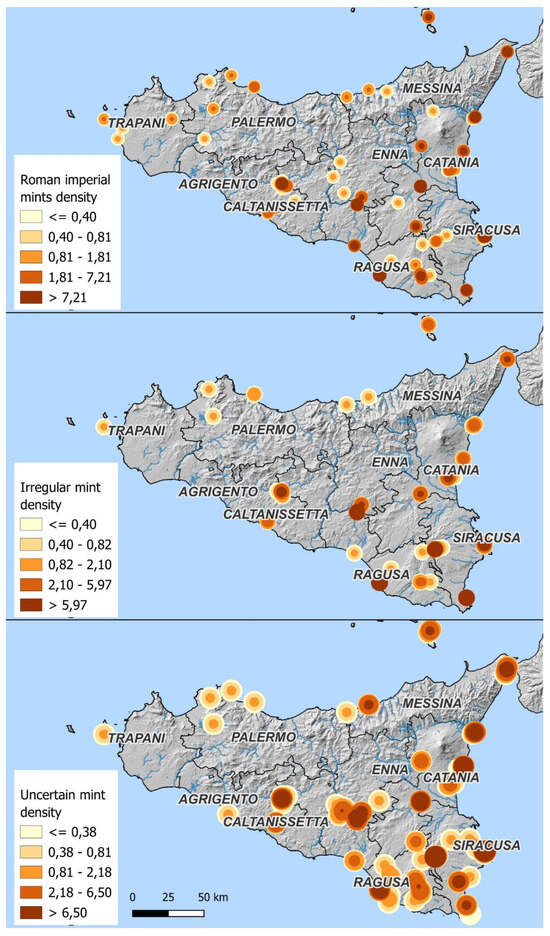

Although in this first experimental phase of data collection regarding the presence of antoniniani in Sicilian territory seems to obtain mainly static maps, a different use of GIS applied to numismatics could be the application of the Kernel Density Estimation method. As seen from the description in Section 3.2, the transformation of data into a continuous surface representing the density of distribution, in this case of coins, makes it possible to identify areas of greater or lesser probability of monetary presence and circulation. In this particular case, the idea was to estimate and compare data on the density and probability of the presence and penetration of radiate coins in the Sicilian territory on the basis of the issuing mints. In this way, it is possible to have an idea, albeit a hypothetical one, of the circulation of the antoninianus with respect to the simple place of discovery. In this specific case, above all, the use of the KDE makes it possible to identify territorial areas in which the coin may have had a greater penetration and circulation.

The distribution and KDE of antoniniani according to the mints of issue is well understood by comparing the three maps (in Figure 10). A negative fact is immediately apparent from the comparison of the last map relative to coins for which the mint of issue is unknown with the first two relative to official antoniniani and their imitations. The number of coins for which the mint cannot be determined is higher, as mentioned above, due to the lack of precise data in the publication sites or the poor state of conservation of the specimens.

Figure 10.

KDE of coin mint.

Particularly interesting is the comparison between the distribution of coins minted by imperial mints, with that of Rome being most represented, and the distribution of barbarous radiates; the antoniniani and their regional imitations circulated in the same places, especially in southern and central-eastern Sicily. The likelihood of coinage penetration in these areas of the island, at the present time of available data, would seem to have been almost capillary based on the assumed density.

Although the imitations constitute approximately 20% of the coins found in the island, and the official mint coins about 47%, the first arrived in Sicily and were most likely accepted as official ones; several of them were also kept in coin hoards, as in Sofiana hoard or in a coin hoard from an unknown site of Syracuse’s province almost entirely composed of barbarous radiates [46].

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This research could contribute to demonstrating the potential of interdisciplinary collaboration between geographical information science and numismatics. It could be used to provide new inputs for the interpretation of coin finds and to boost greater accuracy. In many cases, in fact, the accuracy and the precision of numismatic datasets in this case is not as high as would be desirable for a GIS to build significant large scale models with a high resolution. Despite these limitations, this study focused on spatial distribution rather than chronological analysis. This decision does not imply that spatial data are inherently more reliable than temporal data—both dimensions present significant challenges. However, while the minting date of a coin is usually identifiable, the moment when it was lost or hidden remains sometimes uncertain. For future improvements, the use of other spatio-temporal analysis would strengthen the model and should be considered.

This work is intended to be a preliminary approach toward a broader application of GIS in the territory of Sicily and almost a sort of spur to map the finds on the island in order to have a clearer idea of the monetary distribution at a particular time for the Roman Empire, a period often considered to be in crisis but which for the island shows a very different picture, that of a period characterized by an important movement of men and goods, by an important commercial liveliness, noticeable mainly from the years of the reign of the Tetrici onwards, as demonstrated by the recoveries of imitation coins found all over the island. Important monetary flows would have affected Sicily, a point of passage or even landing on Mediterranean trade routes [25,47,48].

This study investigates other possibilities of the deployment of GIS methods in numismatics and would highlight the distribution of the coins from their place of minting to the places of finding and especially the reasons for which those coins arrived in the island.

However, the results depend on the quality of the data source; we hope that more importance will be given to the protection of data regarding numismatic findings which, in any case, are subjected to greater risks of being introduced into the black market because of their size and sometimes their value. It is also hoped that areas that currently appear to be without numismatic finds or of which we are currently unaware will provide new data that will complete the picture sketched so far for Sicily in the second half of the third century.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, M.D. and M.A.V.S.; software, M.D. and N.M.; validation, M.A.V.S.; data curation, M.D. and M.A.V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D. (Section 1, Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 5), M.A.V.S. (Section 1, Section 2, Section 3.1, Section 4 and Section 5) and N.M. (Section 1, Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 5); writing—review and editing, M.D., M.A.V.S. and N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request partially, because they are part of a study still in the development phase.

Acknowledgments

Authors are very grateful to Giuseppe Guzzetta, former Professor of Ancient Numismatics at the University of Catania, for kindly providing suggestions and insightful remarks. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Artificial Intelligence, limited in a few parts of the text, for the purposes of improving the English quality. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GIS | Geographical Information System |

| KDE | Kernel Density Estimation |

Appendix A

In this appendix we listed the complete references used as sources for the antoniniani GIS.

- Ampolo, C.; Carandini, A.; Pucci, G.; Pensabene, P. La villa del Casale a Piazza Armerina. Problemi, saggi stratigrafici ed altre ricerche. Mélanges de l’Ecole française de Rome 1971, 83, 141–281.

- Buttrey, T.; Erim, K.; Groves, T.; Holloway, R.R. Morgantina Studies 2. The Coins (Princeton, NJ 1989) 1989.

- Carbé, A. Catalogo. In Un percorso archeologico attraverso gli scavi, Bacci, G.M.T., G., Ed.; Messina, 2001; pp. 96–97.

- Carbé, A. Considerazioni sulla circolazione monetale a Messina alla luce dei materiali degli scavi recenti. In Da Zancle a Messina. Un percorso archeologico attraverso gli scavi, Bacci, G., Tigano G, Ed.; Messina, 2002; Volume II, pp. 71–85.

- Carbé, A. Le monete. In Apollonia. Indagini archeologiche sul Monte di San Fratello 2003–2005, Bonanno, C., Ed.; Roma, 2008; pp. 63–73.

- Carbé, A. Brevi note sui rinvenimenti monetali dalla necropoli tardoantica di Halaesa. In Alaisa-Halaesa. Scavi e ricerche (1970–2007), Scibona G, T.G., Ed.; Messina, 2009; pp. 191–199.

- Carettoni, G. Tusa (Messina). Scavi di Halaesa (seconda relazione). Notizie degli Scavi di Antichità 1961, 15, 266–321.

- Castellana, G. Ricerche nel territorio agrigentino. Kokalos 1988, 34–35, 503–540.

- Chowaniec, R.; Więcek, T.; Guzzardi, L. “ Akrai” greca e” Acrae” romana. I rinvenimenti monetali degli scavi polacco-italiani 2011–2012. Annali (Istituto Italiano di Numismatica) 2013, 59, 237–269.

- Cultrera, G. Siracusa. Scoperte nel Giardino Spagna. Notizie degli scavi di antichità 1943, 33–126.

- Daehn, H.-S. Die Gebäude an der Westseite der Agora von Iaitas; E. Rentsch: 1991; Volume 3.

- Di Stefano, G. Scavi e ricerche a Camarina e nel Ragusano (1988–1992). Kokalos 1993, 39–40, 1367–1421.

- Fiorentini, G. La basilica e il complesso cimiteriale paleocristiano e proto bizantino presso Eraclea Minoa. In Proceedings of the Atti del I congresso internazionale di archeologia della Sicilia bizantina (Palermo)[Byzantino-Sicula IV], Corleone, 28 July–2 august, 2002; pp. 223–241.

- Gandolfo, L. Intervento. Kokalos 1987, XXXIII, 284–285.

- Gandolfo, L. Note sulla circolazione monetaria soluntina. In Proceedings of the Quarte giornate internazionali di studi sull’area elima. Atti, Erice, 1–4 December 2000, 2003; pp. 549–555.

- Garraffo, S. Su alcuni rinvenimenti monetari nell’area cimiteriale della ex Vigna Cassia a Siracusa. Rivista di Archeologia Cristiana Roma 1981, 283–324.

- Gentili, G.V. Siracusa: scoperte nelle due nuove arterie stradali, la Via di Circonvallazione, ora Viale P. Orsi, e la Via Archeologica, ora Viale FS Cavallari; Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei: 1951; Volume V.

- Gentili, G.V. BARRAFRANCA (Enna) – Scoperte di tombe; Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei: 1956; Volume X.

- Gentili, G.V. Soprintendenza alle Antichità della Sicilia Orientale. AIIN 1956, 3, 224–227.

- Gentili, G.V. La villa romana di Piazza Armerina Palazzo Erculio; Libreria dello Stato: 1999; Volume II.

- Giustolisi, V. Alla ricerca dell’antica Hykkara. Kokalos 1971, XVII, 105–123.

- Guzzetta, G. Rinvenimenti monetali da Marina di Recanati (Naxos). AIIN 1980–1981, 27–28, 259–286.

- Guzzetta, G. Le monete da Kaukana. In itinere fra le più antiche testimonianze cristiane degli Iblei. In Proceedings of the Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi, Ragusa-Catania, 3–5 aprile 2003, 2005.

- Guzzetta, G. Un tesoretto (?) della metà del IV secolo da Cava Ispica. Archivum Historicum Mothycense 2005, 11, 5–15.

- Guzzetta, G. La documentazione monetale dalle aree funerarie di contrada Mirio di S. Croce Camerina. In Proceedings of the Atti del IX Congresso Nazionale di Archeologia Cristiana, Agrigento, 2007; pp. 1557–1564.

- Guzzetta, G. Le monete della necropoli. In La necropoli tardoromana di Treppiedi a Modica, Di Stefano, G., Ed.; Palermo, 2009; pp. 34–42.

- Guzzetta, G. Le monete dall’abitato e dalla necropoli di contrada Monachella. In Priolo romana, tardo romana e medievale. Documenti, paesaggi, cultura materiale, Malfitana, D.C., G., Ed.; 2011; Volume I, pp. 187–191.

- Guzzetta, G. Il tesoro dei sei imperatori dalla baia di Camarina. 4472 antoniniani da Gallieno a Probo. 2014.

- Guzzetta, G. Monete dagli scavi 2014–2015 nel teatro antico di Catania. In Catania antica. Nuove prospettive di ricerca, F, N., Ed.; Palermo, 2015; pp. 351–358.

- Guzzetta, G. Monete dagli scavi del 2015 a nord della Rotonda a Catania. In Catania antica. Nuove prospettive di ricerca, F, N., Ed.; Palermo, 2015.

- La Lomia, M.R. Ricerche archeologiche nel territorio di Canicatti: Vito Soldano. Kokalos (Roma) 1961.

- Lanteri, R. Gruzzolo monetale dall’ipogeo Trigilia a Siracusa. Archivio Storico Siracusano, s. III, IX 1995, 40–57.

- Libertini, G. Nuova esplorazione del rudero di Casalotto. NSA 1922, XIX, 498–499.

- Li Gotti, A. Barrafranca (Enna). Rinvenimenti nel territorio. NSA 1959, XII, 357–365.

- Lo Monaco, V. Schede di catalogo. In Il “Tesoro dei sei imperatori” dalla baia di Camarina. 4472 antoniniani da Gallieno a Probo, Guzzetta, G., Ed.; Catania, 2014; pp. 182–205, 281–379.

- Di Stefano, T.; Lucchelli, G. Monete dall’agorà di Camarina. Campagne di scavo 1983–1995; Milano, 2004.

- Macaluso, R. Le monete. Kokalos 1986, XXXII, 322–324.

- Macaluso, R. Le monete della collezione civica di Favignana. Studi sulla Sicilia Occidentale in onore di Vincenzo Tusa 1993, 112–118.

- Macaluso, R. Le monete. In Agrigento. La necropoli paleocristiana sub divo, N., B., Ed.; 1995; pp. 303–323.

- Mammina, G. Catalogo. AIIN 1999, 271–279.

- Manganaro, G. La collezione numismatica della Zelantea di Acireale. M. Rendic. Accad. Sci. Lett. B. Arti Acireale 1970, X, 271–318.

- Martorana, I. Monete dagli scavi dell’Ottocento di Solunto. University of Catania, 2008–2009.

- Mastelloni, M. Tesoretto di antoniniani da Reggio Calabria, frazione Ravagnese, Soprintendenza Archeologica della Calabria. AIIN 1990, 37, 307–323.

- Mastelloni, M. Il ripostiglio di Bova Marina loc. Pasquale: brevi note sui rinvenimenti monetali nell’era dello Stretto. Mélanges de l’école française de Rome 1991, 103, 643–665.

- Mastelloni, M. Monete e imitazioni in un piccolo ripostiglio tardoantico. Rivista Italiana di Numismatica 1993, XCV, 505–528.

- Mastelloni, M. Le monete. In Meligunìs Lipára, Bernabó Brea, L.C., M., Ed.; Palermo, 1998; Volume IX, pp. 333–351.

- Mastelloni, M. Le monete rinvenute nello scavo. In Meligunìs Lipára, Bernabó Brea, L.C., M.; Villard, F., Ed.; Palermo, 2001; Volume XI, pp. 763–778.

- Musumeci, M. Indagini Archeologiche a Belvedere e Avola. 1993–1994, XXXIX-XL, 1353–1366.

- Orsi, P. Catania. Ipogeo cristiano dei bassi tempi rinvenuto presso la città. NSA 1893, 385–390.

- Orsi, P. Ripostiglio monetale del basso impero e dei primi tempi bizantini rinvenuto a Lipari. RIN 1910, 23, 353–359.

- Orsi, P. Messana: la necropoli romana di S. Placido e di altre scoperte avvenute nel 1910–1915; MAL: 1916; Volume XXIV, pp. 121–218.

- Puglisi, M. Un tesoretto monetale tardo-antico. In Naxos di Sicilia in età romana e bizantina ed evidenze dai Peloritani. Catalogo della Mostra Archeologica (Museo di Naxos, 3 December 1999 – 3 January 2000), Lentini, M., Ed.; Edipuglia: Bari, 1999; pp. 63–78.

- Rizzo, M.S.; Modica, M. Saggio 9 L. In Agrigento romana. Scavi e ricerche nel Quartiere Ellenistico Romano. Campagna 2013, Pacarello, M.C., Rizzo, M.S., Eds.; Caltanissetta, 2015; pp. 73–88.

- Salinas, A. GIRGENTI – Necropoli Giambertone a s. Gregorio. NSA 1901, 29–39.

- Santangelo, S. Il tesoretto di bronzi da Sofiana (CL). AIIN 2002, 49, 105–154.

- Santangelo, S. La circolazione monetaria nel territorio di Scicli in età greca e romana. In Scicli: archeologia e territorio [Kasa 6], Palermo: Officina di StudiMedievali, Militello, P., Ed.; Palermo, 2008; pp. 293–312.

- Sole, L. Museo Archeologico Regionale di Gela. Sequestri di monete da Gela e il suo territorio. AIIN 2004, 49, 285–320.

- Tusa Cutroni, A. Le monete. NSA 1966, 12–14, 348–352.

- Tusa Cutroni, A. Le monete. In Mozia – II. Rapporto preliminare della Missione archeologica della Soprintendenza alle Antichità della Sicilia occidentale e dell’Università di Roma, Ciasca, A., Forte, M., Garbini, G., Tusa, V., Cutroni, T., Verger, A., Eds.; Roma, 1966; Volume 12–14, pp. 155–156.

- Tusa Cutroni, A. Vita dei medaglieri. Soprintendenza alle antichità per le province di Palermo e Trapani. AIIN 1965–1967, 12–14, 224–232.

- Vicari Sottosanti, M.A. Second and third century Roman Coin Hoards in the ‘P. Orsi’ Museum in Syracuse. In Proceedings of the 16 th Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology (SOMA), Florence, Italy, 1–3 March 2012, 2013.

- Vicari Sottosanti, M. Schede di catalogo. In Il “Tesoro dei sei imperatori” dalla baia di Camarina. 4472 antoniniani da Gallieno a Probo, Guzzetta, G., Ed.; Catania, 2014; pp. 155–181, 206–281-383.

References

- Verhagen, P. Spatial Information in Archaeology. Handb. Archaeol. Sci. 2023, 2, 1163–1181. [Google Scholar]

- Conolly, J.; Lake, M. Geographical Information Systems in Archaeology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Conolly, J. Geographical information systems and landscape archaeology. In Handbook of Landscape Archaeology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 583–595. [Google Scholar]

- Biscione, M.; Danese, M.; Masini, N. A framework for cultural heritage management and research: The Cancellara case study. J. Maps 2018, 14, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, M.; Masini, N.; Biscione, M.; Lasaponara, R. Predictive modeling for preventive Archaeology: Overview and case study. Open Geosci. 2014, 6, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Leo, P.; Bavusi, M.; Corrado, G.; Danese, M.; Giammatteo, T.; Gioia, D.; Schiattarella, M. Ancient settlement dynamics and predictive archaeological models for the Metapontum coastal area in Basilicata, southern Italy: From geomorphological survey to spatial analysis. J. Coast. Conserv. 2018, 22, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel, A.M.; Ferrandes, A.F.; Pardini, G. Archeonumismatica. In Analisi e Studio dei Reperti Monetali da Contesti Pluristratificati; Edizioni Quasar di Severino Tognon: Roma, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Asolati, M. Il dato numismatico come contesto archeologico: I rinvenimenti monetali dall’Unità 4 di Kom al-Ahmer (Delta del Nilo, Egitto). In Archeonumismatica. Analisi e Studio dei Reperti Monetali da Contesti Pluristratificati; Esquivel, A.M., Ferrandes, A.F., Pardini, G., Eds.; Proceedings of the Workshop Internazionale di Numismatica, Roma, Italy, 19 September 2018; Sapienza Università Editrice: Roma, Italy, 2023; pp. 445–457. [Google Scholar]

- Breier, M. GIS for Numismatics–Methods of Analyses in the Interpretation of Coin Finds. In Mapping Different Geographies; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Esquivel, A.M. Strumenti per l’analisi spaziale dei rinvenimenti numismatici: Mappe di distribuzione e GIS. Anal. Studio Reper. Monet. Contesti Pluristratificati 2023, 2, 437. [Google Scholar]

- Doménech-Belda, C.; Ruiz, V.A. Spatial analysis in numismatics: GIS and coins. Archeonumismatica Anal. E Studio Dei Reper. Monet. Contesti Pluristratificati 2018, 2023, 459. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, I.; Bost, J.P.; Hiernard, J. Fouilles de Conimbriga, 3: Les monnaies. In Mission Archéologique Française au Portugal; Musée Monographique de Conimbriga: Paris, France, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- García-Bellido, M.P.; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones, C.f. Las legiones hispánicas en Germania: Moneda y ejército. In Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas; Ediciones Polifemo: Madrid, Spain, 2004; p. 354. [Google Scholar]

- University of Oxford. The Oxford Roman Economy Project. Available online: https://oxrep.classics.ox.ac.uk/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Bowman, A.; Wilson, A. Quantifying the Roman Economy: Methods and Problems; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, A.; Wilson, A. The Roman Agricultural Economy: Organization, Investment, and Production; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, A.; Bowman, A. Mining, Metal Supply and Coinage in the Roman Empire. 2010. Available online: https://oxrep.classics.ox.ac.uk/conferences/oxrep_5_mining_metal_supply_coinage_roman_empire/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Ghey, E.; Leins, I.; Crawford, M. A catalogue of the Roman Republican Coins in the British Museum, with Descriptions and Chronology Based on MH Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage (1974); The British Museum: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goligher, W. Coins of the Roman Republic in the British Museum. The English Historical Review, 26, 103, JSTOR 1911, 548–550. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/549846 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Thompson, M.; Mørkholm, O.; Kraay, C.M. An Inventory of Greek Coin Hoards; American Numismatic Society: New York, NY, USA, 1973; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pyzyk, M. Regional bias in late antique and early medieval coin finds and its effects on data: Three case studies. Ukr. Numis. Annu. 2021, 5, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegrini, A.; Benoci, D.; Fontinovo, G.; Mei, A.; Merola, P.; Ricci, C. Il progetto “Sacred Coins”: Costruzione di un geodb, utilizzo del GIS in ambito archeologico e numismatico, struttura del webGIS e del sito web. In Monete sacre. Un WebGIS per le Monete Puniche in Contesti Sacri Mediterranei. Mediterraneo Punico; Allegrini, A., Merola, P., Benoci, D., Eds.; CNR Edizioni: Roma, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Allegrini, A.; Merola, P.; Benoci, D. Monete Sacre: Un WebGIS per le Monete Puniche nei Contesti Sacri Mediterranei; CNR-Istituto di Scienze del Patrimonio Culturale: Naples, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly, H.; Sydenham, E.A. The Roman Imperial Coinage: Pertinax to Geta; Spink & Son: London, UK, 1936; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzetta, G. Il Tesoro dei sei Imperatori dalla Baia di Camarina. 4472 Antoniniani Da Gall. a Probo. Giuseppe Maimone Editore, Catania 2014. p. 444. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/41983905/GIUSEPPE_GUZZETTA_Il_tesoro_dei_sei_imperatori_in_G_GUZZETTA_IL_TESORO_DEI_SEI_IMPERATORI_DALLA_BAIA_DI_CAMARINA_4472_ANTONINIANI_DA_GALLIENO_A_PROBO_CATANIA_2014 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Carson, R. The coinage and chronology of AD 238. In Centennial Publication of the American Numismatic Society; American Numiscatic Society: New York, NY, USA, 1958; pp. 181–199. [Google Scholar]

- Callu, J.-P. La Politique Monétaire des Empereurs Romains de 238 a 311; Ed. de Boccard; Bibliothèque des Ecoles Françaises d’Athenes et de Rome: Paris, France, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Estiot, S. Aureliana. Rev. Numis. 1995, 6, 50–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisafulli, C. La riforma di Aureliano e la successiva circolazione monetale in Italia. In I Ritrovamenti Monetali e i Processi Storico-Economici nel Mondo Antico; Asolati, M., Gorini, G., Eds.; Esedra: Padova, Italy, 2012; pp. 255–282. [Google Scholar]

- Giard, J.-B.; Estiot, S.; Besombes, P.-A. Catalogue des Monnaies de l’Empire Romain: No. 1. D’Aurélian à Florien, 270-276 après J.-C.; La Bibliothèque: Paris, France, 1988; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Chainey, S.; Reid, S.; Stuart, N. When is a hotspot a hotspot? A procedure for creating statistically robust hotspot maps of crime. Innov. GIS 2002, 9, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gatrell, A.C.; Bailey, T.C.; Diggle, P.J.; Rowlingson, B.S. Spatial point pattern analysis and its application in geographical epidemiology. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1996, 21, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.; Fisher, P.; Dykes, J.; Unwin, D.; Stynes, K. The use of the landscape metaphor in understanding population data. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1999, 26, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bracken, I.; Martin, D. Linkage of the 1981 and 1991 UK Censuses using surface modelling concepts. Environ. Plan. A 1995, 27, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, K.R.; Chapman, J.A. Harmonic mean measure of animal activity areas. Ecology 1980, 61, 1040–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worton, B.J. Kernel methods for estimating the utilization distribution in home-range studies. Ecology 1989, 70, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Liu, T.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X.; Qu, S.; Dong, Y. A Study of the Spatial–Temporal Development Patterns and Influencing Factors of China’s National Archaeological Site Parks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, I. Computational approaches towards the understanding of past boundaries: A case study based on archaeological and historical data in a hilly region in Germany. It-Inf. Technol. 2022, 64, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Seong, C. Final Pleistocene and early Holocene population dynamics and the emergence of pottery on the Korean Peninsula. Quat. Int. 2022, 608, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, G.; Auguste, P.; Locht, J.-L.; Patou-Mathis, M. Detecting human activity areas in Middle Palaeolithic open-air sites in Northern France from the distribution of faunal remains. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2021, 40, 103196. [Google Scholar]

- Danese, M.; Lazzari, M.; Murgante, B. Kernel density estimation methods for a geostatistical approach in seismic risk analysis: The case study of Potenza Hilltop Town (Southern Italy). In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications–ICCSA 2008: International Conference, Perugia, Italy,, 30 June–3 July 2008; Proceedings, Part I 8. pp. 415–429. [Google Scholar]

- Orlandini, P.; Adameșteanu, D. Vita dei Medaglieri: Soprintendenza alle Antichità per le Province di Agrigento e Caltanissetta. Gela. AIIN 1955, 2, 214. [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo, S. Il tesoretto di bronzi da Sofiana (CL). AIIN 2002, 49, 105–154. [Google Scholar]

- Vicari Sottosanti, M.A. Dati numismatici dalla Sicilia tardo imperiale: Due complessi monetali del V secolo rinvenuti in Ortigia nel 1896. In Thesaurus Amicorum: Studi in onore di Giuseppe Guzzetta; Crinè, C., Frasca, M., Gentile Messina, R., Palermo, D., Eds.; Quasar: Roma, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Puglisi, M. Un tesoretto monetale tardo-antico. In Naxos di Sicilia in età Romana e Bizantina ed Evidenze dai Peloritani. Catalogo Della Mostra Archeologica (Museo di Naxos, 3 Dicembre 1999–3 Gennaio 2000); Lentini, M., Ed.; Edipuglia: Bari, Italy, 1999; pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Vicari Sottosanti, M.A. Second and third century Roman Coin Hoards in the ‘P. Orsi’ Museum in Syracuse. In Proceedings of the 16th Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology (SOMA), Florence, Italy, 1–3 March 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzetta, G.; Vicari Sottosanti, M.A. La Sicilia e le altre regioni dell’impero romano dal III al V secolo dC: Le testimonianze monetali. Cronache Archeol. 2020, 39, 451–477. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzetta, G.; Vicari Sottosanti, M.A. La Sicilia tardoantica crocevia di commerci mediterranei: Le testimonianze monetali, in Mare Nostrum. I Romani, il Mediterraneo e la Sicilia tra il I e il V secolo d.C. In Proceedings of the XVI Consegno di Studi SiciliAntica, Caltanissetta, Italy, 19 September 2020; pp. 81–94. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).