Abstract

This article carries out an interdisciplinary analysis of five MOOC courses developed by the University of Valladolid and offered on higher education platforms between 2020 and 2024. This research is based on the study of the lexical categories used by the informants participating in these courses, establishing a correlation with the theoretical and practical debates surrounding the definition of heritage and the frameworks of contemporary heritage education. Through a metalinguistic approach, the semantic limits of the emerging lexical categories are examined, paying attention to their ambiguity, polysemy and contexts of use, both from a formal linguistic perspective and from a hermeneutic approach. The analysis is based on natural language processing tools, complemented by qualitative techniques from applied linguistics and cultural studies. This dual approach, both scientific–statistical and humanistically nuanced, allows us to identify recurrent discursive patterns, as well as significant variations in the conceptualization of heritage according to the socio-cultural and geographical profiles of the participants. The results of the linguistic analysis are contrasted with the thematic lines investigated by our research group, focusing on cultural policy, legacy policies, narratives linked to the culture of depopulation, disputed scientific paradigms, and specific lexical categories in the Latin American context. In this sense, the article takes a critical look at discursive production in massive online learning environments, positioning language as a key indicator of the processes of cultural resignification and the construction of legacy knowledge in the Ibero-American context. The findings of my scientific article underscore the pressing need for a multiform liberation of the traditionally constrained concept of heritage, which has long been framed within rigid institutional, legal, and disciplinary boundaries. This normative framework, often centered on materiality, monumentalism, and expert-driven narratives, limits the full potential of heritage as a relational and socially embedded construct. My research reveals that diverse social agents—ranging from educators and local communities to cultural mediators and digital users—demand a more flexible, inclusive, and participatory understanding of heritage. This shift calls for redefining legacy not as a static legacy to be preserved but as a dynamic bond, deeply rooted in affective, symbolic, and intersubjective dimensions. The concept of “heritage as bond”, as developed in contemporary critical theory, provides a robust framework for this reconceptualization. Furthermore, the article highlights the need for a new vehiculation of access—one that expands heritage experience and appropriation beyond elite circles and institutionalized contexts into broader social ecosystems such as education, digital platforms, civil society, and everyday life. This approach promotes legacy democratization, fostering horizontal engagement and collective meaning-making. Ultimately, the findings advocate for a paradigm shift toward an open, polyphonic, and affective heritage model, capable of responding to contemporary socio-cultural complexities.

1. Introduction

The University of Valladolid’s MOOCs—NEP IV through NEP VII and Literacy in Heritage Education—actively promote the construction of heritage concepts by fostering critical, emotional, and participatory engagement with cultural legacy. These courses are grounded in contemporary educational theories that emphasize heritage as a relational and dynamic construct, aligning with the “heritage as bond” perspective. Each MOOC presents multidimensional approaches to legacy, integrating historical, architectural, artistic, and industrial elements while connecting them to broader social, cultural, and emotional frameworks. Through interactive content, video lectures, and collaborative tasks, learners are invited to question traditional views of legacy as static or object-based and instead construct meaning through personal and collective experience. Participants explore concepts such as identity, memory, territory, sustainability, and cultural continuity, which are scaffolded through practical case studies and reflection prompts. The Literacy in Heritage Education course, in particular, enhances learners’ ability to decode heritage narratives, analyze cultural symbols, and understand the role of language in shaping heritage perceptions. By encouraging learner-centered reflection and interdisciplinary dialogue, these MOOCs create a constructivist learning environment where legacy is not merely taught, but co-constructed, negotiated, and re-signified across diverse contexts.

Scientific research in heritage education related to MOOCs has largely focused on content delivery, user engagement, and digital pedagogy, often overlooking the semantic complexity of the term “heritage.” Most studies conceptualize heritage from a conventional perspective, emphasizing its tangible, monumental, and historical dimensions rather than exploring its polysemic and affective layers. For instance, the work by [1] on MOOCs and digital heritage focuses primarily on the digitization of monuments and historical content, without addressing the broader relational and emotional constructs of heritage as lived experience. This limited focus tends to reduce heritage to a cultural product to be transmitted, rather than a dynamic process of identity construction, memory, and social bonding. In contrast, heritage understood as a multiform bond—as conceptualized by [2]—requires acknowledging the subjective, intergenerational, linguistic, and symbolic dimensions of heritage. However, such dimensions are rarely problematized in MOOC-based research, which often prioritizes technological innovation over epistemological reflection. Moreover, the affective, ethical, and civic roles of heritage are frequently underrepresented, as is the critical examination of whose heritage is being taught and for whom. This lack of depth risks reinforcing hegemonic narratives while excluding marginalized or alternative interpretations. Future research must therefore adopt semantic-sensitive methodologies that explore the plural meanings of heritage, especially when analyzing educational discourse in global, open-access platforms such as MOOCs.

The innovation of this scientific article lies in its integrative use of digital language processing tools, specifically Voyant Tools, to analyze semantic patterns in heritage education MOOCs. Unlike traditional content analysis, this approach applies computational linguistics to identify core vocabulary, discursive trends, and emotional markers related to the concept of heritage. The article bridges digital humanities methodologies with pedagogical research, offering a novel way to visualize how heritage is constructed and interpreted by learners in online environments. By using Voyant Tools, the study reveals latent semantic fields, lexical frequencies, and contextual associations, enabling a deeper understanding of how concepts like memory, identity, and cultural value are articulated. This methodology represents an epistemological advancement in heritage education research, providing empirical evidence that supports critical, affective, and pluralistic conceptions of heritage. The article sets a precedent for the data-driven, interpretive analysis of educational discourse within digital learning ecosystems.

The 21st century ushered in a significant increase in the valuation of cultural legacy [3], which explains why in recent years the world has seen a growing demand for the recognition of heritage assets [4]. This has, moreover, led different communities and stakeholders to claim their rights over the several manifestations of heritage [5]. Thus, legacy has come to occupy a prominent place in political, cultural, and social agendas [6], promoting legacy diplomacy as a constantly expanding field of interest [7]. In this way, new forms of relating to legacy have been enabled, which has consequently favored its multiple conceptualizations [8].

The conceptualization of heritage as a process-based action is conditioned by dynamism and adaptability [9], i.e., it is a product under constant construction and deconstruction [10]. Factors such as cultural evolution, political and economic changes, social and ideological transformations, as well as the acceptance of other socio-cultural realities, have proved determinant in the ongoing redefinition of heritage [11,12]. Likewise, the events of the present and the emergence of new generations make it possible for the conceptualization of legacy to be further enriched [13]. Far from being a static concept, heritage is variable and highly self-critical so that the new perspectives that arise involve the democratization of memory [14,15].

However, the meaning of heritage is not restricted to one sole dimension. Instead, it is the individuals who elicit the values that lead to its conceptualization [16]: the main axis that sustains its definition is shaped by those who recognize, choose, enjoy, create, disseminate and transmit heritage itself [17]. In other words, the category of heritage is molded by people, their contributions and their ways of being [18], so heritage is understood as a result of the relationship between assets and people [19]. The growing number of subjects sensitive to heritage fuels interpretations, opinions, attitudes, points of view and definitions around it [20]. Different conceptualizations of legacy currently coexist in a compatible manner, and this makes it possible for us to enhance its value [21].

This conceptual plurality reflects the growing diversity around heritage [22], highlighting that such diversity is not the exception but rather the rule [21]. The multiple ways in which heritage terminologies are used [23] evidence the need to interpret legacy according to different approaches to perceiving and understanding it [24].

It is essential to recognize that individual perceptions of heritage are subjective and vary according to sex, knowledge, age, and culture [25]. In this sense, heritage is seated in the minds of individuals [26] and functions as a conceptual hinge [27]. This explains why it is so difficult to define or establish a uniform concept of heritage [28]. In order to shed light on this phenomenon, a study of the similarities and differences in legacy definitions and conceptualizations at the European level reveal that the concept of heritage is reasonably diverse [29], highlighting the growing importance of addressing this issue, as well as its progressive expansion [6].

Fontal’s [2] vision of heritage as a bond represents a significant theoretical shift within the field of heritage education. Her approach emphasizes the affective, symbolic, and participatory dimensions of legacy, viewing it as a relational process tied to identity, memory, and emotional connection, rather than a fixed inventory of objects. This perspective prioritizes intergenerational dialogue, civic engagement, and the subjective appropriation of cultural references.

In contrast, more classical perspectives on legacy education, such as those proposed by authors like Gutiérrez Pérez [30], or González Moreno-Navarro [31], tend to focus on tangible legacy—especially monumental architecture, historical buildings, and artistic masterpieces. These views align with traditional museological frameworks, emphasizing preservation, transmission of historical facts, and the didactic use of legacy sites for fostering national identity and historical consciousness.

The controversy lies in the ontological and pedagogical implications: while Fontal advocates for a constructivist and affective approach—in which heritage is co-constructed and emotionally meaningful—more conservative models tend to prioritize expert knowledge, objective narratives, and heritage as a cultural product to be protected and transmitted. Fontal’s model [2] challenges the verticality and exclusivity of classical legacy paradigms, arguing instead for horizontal, inclusive, and pluralistic educational practices. This tension reflects broader epistemological debates between essentialist vs. constructivist conceptions of heritage in contemporary scholarship.

The present study, therefore, undertakes an analysis of the definitions of heritage provided in ten Massive Online Open Courses (MOOC) carried out over a four-year period at the University of Valladolid (Spain). Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are essential tools for integrating the conceptualization of heritage as a bond—as proposed by Olaia Fontal—with the diversity of target audiences engaging with cultural content in the digital age. Fontal emphasizes heritage not as a static collection of artifacts, but as a dynamic and participatory process rooted in identity, memory, and emotional connection. MOOCs, by their open and accessible nature, facilitate this dialogical approach to heritage by enabling broad and heterogeneous participation across geographical, generational, socio-economic, and cultural boundaries.

For instance, a MOOC on intangible legacy can engage high school students in Argentina, museum professionals in France, Indigenous community members in Canada, and policy-makers in India. Each group brings unique epistemologies and emotional attachments, enriching the interpretive process. MOOCs thus serve as interactive platforms where these diverse publics can not only receive information but also co-construct heritage narratives through forums, peer-review activities, and collaborative projects.

Furthermore, the two-way communication afforded by MOOCs enables real-time feedback loops between audiences and scientific presenters. This fosters epistemic humility and encourages researchers to adapt their content and methodologies based on user insights and culturally embedded perspectives. In this way, MOOCs transcend their educational function to become cultural laboratories, catalyzing inclusive knowledge production and reinforcing heritage as a shared, negotiated, and evolving construct.

Here are 10 articulated scientific objectives from the research:

- To critically examine the sources of discomfort experienced by individuals regarding institutional and societal constraints on the concept of heritage.

- To analyze the impact of urban planning, technological mediation, and the seriality of modern life on both tangible and intangible legacy.

- To explore how the commodification of culture and leisure contributes to the devaluation of traditional arts, craftsmanship, and original heritage practices.

- To investigate the erosion of conviviality and the proliferation of social and cultural “noise” as barriers to meaningful heritage engagement.

- To identify the ways in which language—as a vehicle of cultural transmission—reflects broader processes of heritage enrichment or impoverishment.

- To assess the degradation and neglect of territorial legacy, including its environmental, cultural, and symbolic dimensions.

- To propose educational interventions that prioritize heritage as a multidimensional, affective, and inclusive construct rather than a static institutional asset.

- To incorporate linguistic awareness into heritage education, recognizing language as both a product and a shaper of cultural legacy.

- To advocate for a paradigm shift in heritage education towards holistic approaches that account for conceptual plurality, context-dependence, and emotional resonance.

- To contribute to the development of a critical and transformative research agenda in heritage education that challenges reductionist and technocratic models.

2. Materials and Methods

Statistically analyzing participatory MOOCs developed by the Heritage Education research group at the University of Valladolid offers an ideal framework for addressing the theoretical dichotomy between heritage as a monumental legacy and heritage as a social bond. These MOOCs are specifically designed to emphasize active learner engagement, dialogic interaction, and the co-construction of meaning—elements that are central to the “heritage as bond” paradigm.

By collecting and analyzing user data such as participation rates, interaction patterns, forum contributions, and qualitative feedback, researchers can identify how learners conceptualize heritage during and after the course. This helps to measure the effectiveness of participatory methodologies in shifting perceptions away from static, monumental views of heritage toward more relational, inclusive interpretations.

The University of Valladolid’s group also integrates reflexive and affective tasks into their courses, which generate rich datasets for analysis. Responses to these tasks provide insight into the emotional and cultural connections learners form with heritage. These indicators—especially when tracked across diverse demographics—can empirically demonstrate whether a social, community-driven notion of heritage resonates more strongly than a traditional, object-focused one.

Moreover, statistical tools can reveal patterns of engagement and identify which course components most effectively foster conceptual transformation. This evidence-based approach allows for theoretical refinement, offering a grounded response to the long-standing debate between legacy and bond.

In short, these MOOCs are not only pedagogical experiments but also valuable laboratories for testing and evolving heritage theory.

The main purpose of this paper is to explore the representations developed by participants regarding the definition of heritage. We have employed qualitative techniques with an interpretive approach based on evidence from participants and relevant bibliographical sources [32]. Such techniques enable a deeper understanding of the object of study, while additional descriptive–interpretive techniques are deployed to address the analysis and discussion of representations, which implies a search for the meaning attributed by individuals to the content of such representations, i.e., the sense and significance that participants assign to heritage. To understand the facts underlying the collected data, the interpretation process is essential, since understanding the phenomena involves more than a superficial description and requires a deep reflection on their meaning and context supported by anticipated data reduction [33] along a linear sequence. Such a framework makes us return once and again to the essential research categories and questions: What is meant by heritage? What words do participants use to define heritage? What representation of heritage does participants resort to? What inputs and influences can we trace in their descriptions of heritage?

2.1. Sample

The participants in this sample were users enrolled in the Massive Online Open Courses (MOOCs) offered over a four-year period by the University of Valladolid, whose names are next provided in English translation: “New educational strategies for industrial, architectural and cultural heritage: NEP IV”, “Strategies to raise awareness of cultural heritage: NEP V”, “New strategies to save cultural heritage: NEP VI”, “New strategies to save cultural heritage: NEP VII” and “Literacy in heritage education”.

The University of Valladolid has developed a series of five MOOCs over a four-year period aimed at advancing heritage education through innovative, inclusive, and interdisciplinary approaches. These courses—titled “New Educational Strategies for Industrial, Architectural and Cultural Heritage: NEP IV”, “Strategies to Raise Awareness of Cultural Heritage: NEP V”, “New Strategies to Save Cultural Heritage: NEP VI & VII”, and “Literacy in Heritage Education”—share a common objective: to empower participants with tools for understanding, valuing, and preserving cultural heritage across multiple domains.

Their content integrates theoretical frameworks with case studies, practical strategies, and participatory methodologies, focusing on industrial, architectural, artistic, and intangible heritage. Key themes include emotional and civic engagement, sustainability, and educational innovation. NEP VI and VII particularly emphasize the urgency of safeguarding endangered heritage in the face of globalization and urban pressure.

The target audience includes educators, cultural mediators, museum professionals, students, public administrators, and community members with an interest in heritage. Designed to foster both awareness and action, these MOOCs provide a multilingual and accessible platform for global participation, reinforcing the role of education in building inclusive and resilient heritage practices.

Participants enrolled in these MOOCs were not required to meet specific enrollment criteria. Anyone interested in acquiring knowledge and awareness in relation to heritage around the triangle formed by persons, assets, and bonds could access the courses without restrictions.

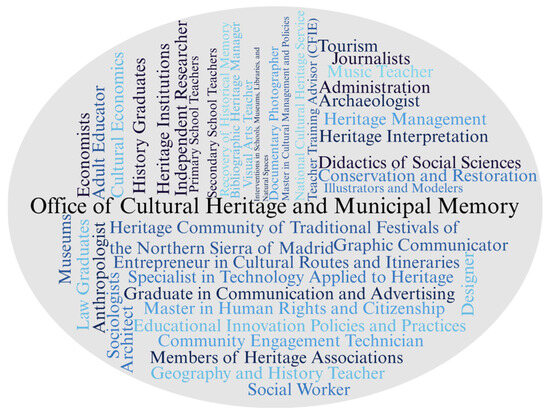

Consequently, the range of nationality profiles was quite diverse, starting with participants from Spain and Portugal, yet also including a relevant participation of enrollees from Latin American countries like Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Uruguay, Colombia, and Peru. Regarding professional profiles, Figure 1 graphically shows the most outstanding ones.

Figure 1.

MOOC participants’ professional profiles. Source: own construction.

Figure 1 indicates a diversification of professions, not limited to teaching but including related areas of both social sciences and humanities, coherently with the diversification of emerging university degrees in Spain and Latin America, attentive to job opportunities: tourism; heritage management; communication and advertising.

A sample was taken following the results of one of the activities in these courses where participants had to “produce their own definition of heritage”, with a total of 309 definitions.

2.2. Procedure

Voyant Tools and QSR NUDIST [34] are particularly suitable for analyzing the semantic correlation between informants’ discourse and the concept of heritage within heritage education research. Aligned with the methodological perspective that emphasizes the intersection of qualitative hermeneutics and digital textual analysis, both tools enable a robust and nuanced exploration of language as a cultural construct. Voyant Tools allows for real-time lexical visualization, frequency mapping, and collocation analysis, making it ideal for detecting patterns in how informants articulate notions of “heritage” and related terms (e.g., memory, identity, territory). It provides visual–semantic models that reveal underlying cognitive and affective associations, supporting such a view of legacy as a socially constructed semantic field. QSR NUDIST [34], on the other hand, enables deep content coding, thematic categorization, and semantic clustering. It is especially effective for identifying discursive structures and latent themes, offering a grounded, bottom-up interpretation of informants’ narratives. This aligns with a call for tools that reveal the plurality, subjectivity, and contextual embeddedness of heritage discourse. Together, these tools support a mixed-methods approach, integrating empirical rigor with interpretive depth, essential for mapping the polysemic and emotional dimensions of heritage in educational contexts.

The procedure was broken down into several phases. (1) First, all data (population and definitions) were collected and organized into a unified and spell-checked document. (2) Then, the text was entered into the Voyant Tools environment [35], which facilitated reading and interpretation. The text mining process involved analyzing natural language texts and then detecting lexical patterns to obtain valuable information [36]. Voyant Tools converts text (unstructured data) into data (structured format) for analysis, using natural language processing (NLP) methods and attempting to extract meaningful information that is useful for a specific purpose [37]. In addition, the environment facilitated the understanding of various statistics related to the terms under scrutiny (absolute frequency, normalized frequency, statistical skewness, and differentiated words), the search of keywords in context, and the export of data. Similarly, it allowed for the visualization of trends by means of distribution graphs displaying the most common terms in the text corpus or the various concordances indicating the co-occurrence of key words or terms with some grammatical context. (3) In a qualitative analysis environment (QSR NUDIST.14) [34] the corpus was then scanned for grammatical categories (Table 1: noun, adjective, verb, and adverb) in a process of categorization and coding.

Table 1.

Corpus categories, definitions and references.

The coding consists of Codes\\CATEGORY, “number density”, total number of participants, participant number, person analyzing, day and time—for example. codes\\NOUNS, “0.8854”, 288, 255, ISM, 11/03/2024 19:54:37. (4) An interpretation of the analyses is performed by implementing the process of going back repeatedly to the research questions.

3. Results

The first results analyzed in Voyant Tools were as follows.

This corpus contains a document with a total of 24,208 words and 4454 unique (unrepeated) words; vocabulary density 0.184; readability index: 12.720; and average words per sentence: 28.4.

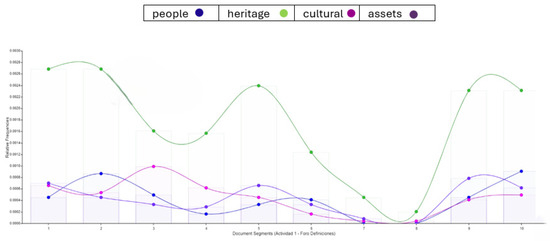

In terms of relative frequency, the most frequently used words (excluding empty words) were: patrimonio (“heritage”), cultural (“cultural”), personas (“persons”), and bienes (“goods/assets”) (see Table 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relative frequencies of most used words. Source: Voyant Tools.

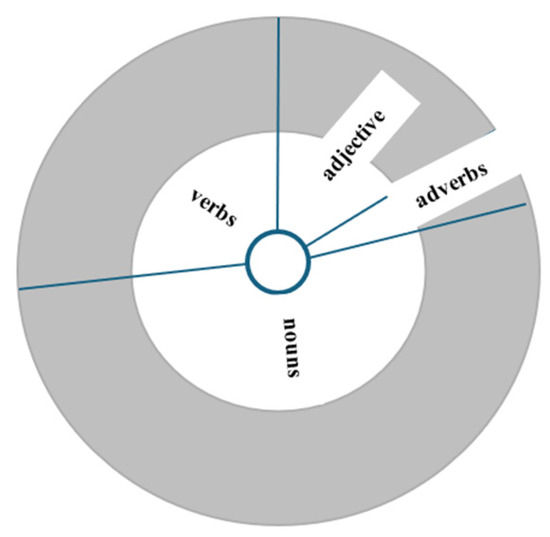

It is striking that within the whole corpus, the words with the highest number of references are (in the following order): nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs. However, when grouping together the most often repeated words by category (Table 2), the order is as follows: nouns (1), adjectives (2), verbs (3), and adverbs (4).

Table 2.

Word count in order of frequency and by category, excluding empty words.

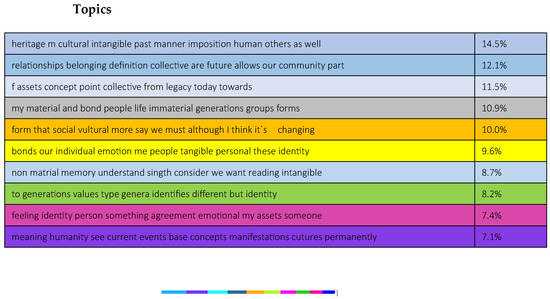

As for the topics detected by the software as most used (including percentages and marked in different colors), these are as follows.

Figure 3 offers a balance of percentage results between the lines with classical definitions of heritage and the qualitative, emotive, and processual proposals that are more in line with the approach of our research group framed in the lexical sequence of Fontal circular or spiral: Know to Understand, to Respect, to Value, to Care for, to Enjoy, to Transmit, and to Know. It gathers in a graphic and simple way the objectives that heritage education should have.

Figure 3.

Document topics by colors and percentages. Source: Voyant Tools: Activity 1: Definitions forum.

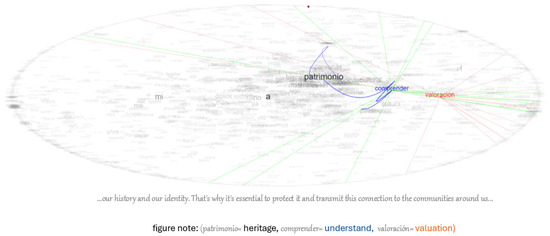

Another visual provided by this software is the textual arc, a dynamic graphic that changes shape as the read words appear (Figure 4):

Figure 4.

Textual arc that interrelates words as they appear in the course of reading. Source: Voyant Tools.

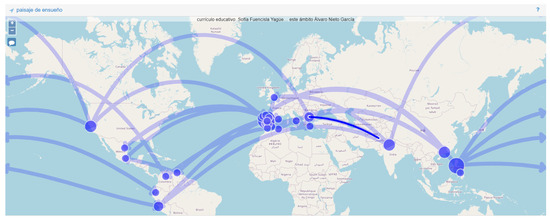

Finally, we highlight the places that are mentioned and appear in the text of the document (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Places mentioned in the corpus. Source: Voyant Tools.

Results are shown next to each of the categories:

NOUNS

Initially, the absolute prevalence of nouns can be observed (see Figure 6) because of several issues.

Figure 6.

Frequency of categories and coding. Source: Nudist*vivo14.

- (a)

- The definition of the word “heritage” (patrimonio) provided by the Royal Spanish Academy [38] seems to be anchored in Roman law, not only in terms of heritage as a set of “substantive” goods but furthermore embracing the legal connotations in Spanish suggestive of property, lineage, identity, territoriality or goods “protected by law”. The Spanish word for heritage (patrimonio), in the sense used in this research, also comprises meanings related to (business) wealth or patrimony (the following is an English translation of the corresponding entry for patrimonio at Diccionario de la lengua española (DLE)):

- From Latin patrimonium.

- DLE First definition: m. The estate that is inherited from one’s ancestors.

- DLE Second definition: m. All of one’s property and rights acquired by any title.

- DLE Third definition: m. patrimonialism.

- DLE Fourth definition: m. Law. Set of goods belonging to a natural or legal person, or attached to a purpose, susceptible to economic estimation.

Historical Heritage

1.m. A collection of a nation’s assets accumulated over the centuries, which, because of their artistic, archaeological, etc., significance, are subject to special protection by legislation. Codes\\NOUNS, “0.3448”, 288, 59, ISM, 29/02/2024 20:47:04.

“Undoubtedly, it is not easy to define heritage in the sense intended in this course. The RAE (Royal Spanish Academy) refers to a set of goods and rights belonging to a person that are susceptible to economic valuation. According to this idea, I would define heritage (cultural, architectural, industrial...) as a set of elements, tangible and intangible, whether they be related to culture, real estate, urbanism...”. Codes\\NOUNS, “0.8854”, 288, 255, ISM, 11/03/2024 19:54:37.

The adoption of such a static view of legacy enables us to list a series of statements made by participants concerning the lexical categories discussed in the following sections. These claims reveal a holistic and symbiotic conception that can be traced in contemporary research on heritage education. Moreover, they are interconnected insofar as their tentacles consistently question the major thematic axes involved—both education and heritage and, by extension, contemporary philosophy and society at large.

- (b)

- Next, a first claim against this status quo is observed where a questioning of the institutions of power is alluded to by means of the Spanish cognates for “transformation” and “imposition”. This brings up the debate on the theoretical issue of the role of institutions and de facto powers regarding the state of abandonment of the artistic, monumental and intangible heritage of Iberia and the neglectful deal received by the depopulated regions where most of this heritage is situated:

“…to my mind, and trying to avoid Manichaeism, heritage can be seen as both and opportunity and an imposition. As an opportunity to transform reality, but also as a cultural imposition bequeathed and assumed either uncritically or critically”. Codes\\NOUNS, “0.8854”, 288, 22, ISM, 26/02/2024 12:06:03.

- (c)

- In parallel to the RAE’s approach, while we ask ourselves whether the language of academies has the power to establish reality or at least promote certain realities, we can note the sociological persistence of a social and cultural view of heritage defined in terms of movable and immovable property, a set of “nouns” anchored in tradition, classicism, genealogy, etc. The following evidence deals with the tension between the community and individuals. The complexity of this tension stems from the fact that human beings need a space—and a structure—for social relations in order to develop and express themselves, while at the same time, and on the contrary, the social pressure exerted by custom and inertia leads to different types of psychological dysfunctions from which, in turn, the impulse of liberation emerges.

“In an extremely simple way, I could say that heritage is everything that someone considers heritage; everything which, in relational terms, means some value as regards identity, memory, emotions, and individual and social construction. This basic definition has its social and legal limitations, that is to say, for something that we consider individuals to be thought of as collective or social heritage, it must be part of a set of relationships (belonging, identity, ownership, emotion or sensibility) with other human beings. It is the community that ratifies the cultural heritage value of something, whether it be an object, a site, an experience, a story, a form; although we all have the right to build our relationships, identities and memories, it is legitimate to consider emerging elements as heritage while new relationships are created on the basis of new or already existing elements. Heritage is not static, it flows in its conception and composition along with time, space and the feeling of those who are exposed to it”. Codes\\NOUNS, “0.8854”, 288, 33, ISM, 26/02/2024 12:26:34.

The following participant states the concept of heritage as a social construct (the noun construct itself alludes to the tension between individuals and society mentioned above):

“Heritage is a social construct, in whose conceptualization converge natural, historical, ethnological and scientific-technological elements, always contextualized in a spatio-temporal environment that transforms them into symbols of cultural identity.” Codes\\NOUNS, “0.8854”, 288, 37, ISM, 26/02/2024 12:42:13.

- (d)

- The scientific context of education and research generates per se a communicative bias and a lexical selection slanted toward defining categories instead of using vaguer or more open categories, such as adjectives or adverbs, which are statistically a minority. This scientific context also underpins the fact that many departures from classicism are likewise defined (expressed) by means of nouns or take up nouns enshrined by current theory yet used with a more emotional or holistic sense—e.g., “bond”.

The noun “bond” and all nouns of this kind seem to broaden their meaning so as to encompass an expressiveness that alludes rather to the dynamics of verbs, adjectives, or adverbs. Unlike this category, adverbs are generally circumstantial qualifiers of a verbal predicate and do not have inflections [39]:

“From my point of view, heritage is all those tangible and intangible assets that are part of our history and which therefore people attach a physical or sentimental value to, because in addition to enriching our sense of identity, they create a bond with our ancestors and strengthen or enhance our culture”. Codes\\NOUNS, “0.8854”, 288, 237, ISM, 11/03/2024 19:04:17.

- (e)

- Another piece of evidence worth considering is philosophical in nature, asserting that the individual—and their inalienable freedom of conscience—is the core source of meaning, in contrast to society, the status quo, or the established powers.

“My experience of cultural heritage was mainly from a formal point of view resulting from my exposure to assets that are either public or private property and possess certain aesthetic, historical or technological characteristics that justify their conservation and legal custody. However, thinking about the relationship between those assets and individuals, or groups of individuals, has changed my perception: it is the people who give meaning to things, to goods; it is the people who assign significance to them, who value them and are moved by them. This is the key to the significance of heritage”. Codes\\NOUNS, “0.8854”, 288, 92, ISM, 28/02/2024 18:57:42.

- (f)

- In addition, we find evidence for another philosophical conflict around the concepts vivacidad (“vibrancy”) and cuidado (“care”), which constitutes a contemporary reference not only to a humanist defense of heritage but also to a vindication of the world’s liveliness or “vibrancy” as a differential and crucial factor in any contemplation and interpretation of reality:

“My understanding of heritage emphasizes our connection to the vibrancy of the living world—specifically, the emotions and sensations that arise from the meanings, values, care, and attitudes we associate with certain things, places, and events”. Codes\\NOUNS, “0.8854”, 288, 19, ISM, 24/02/2024 21:23:13.

The following testimony also contains the same vindication of the living world as an emergent, creative, agent—a creator (or co-creator) of sense and meaning:

“…It is the manifestation of every form of life”. Codes\\NOUNS, 288, 11, ISM, 24/02/2024 21:18:53.

- (g)

- In regard to epistemology, mention should be made of a new advocacy for the renewal of the concept of heritage, understood as scientific, historical, and geographical evolution:

“My definition has two aspects. One considers heritage as “nomadic” or “amphibological”, since it changes according to the period and the academic discipline that employs the concept. But on the other hand, it is also a testimony that generates bonds and identities”. Codes\\NOUNS, “0.8854”, 288, 13, ISM, 24/02/2024 21:20:20.

- (h)

- The repetitive aesthetics sometimes implied by today’s hyper-technological society also generates uneasiness in participants who resonate with elements of craftmanship or artistic finesse versus this state of affairs:

“This lock cover encapsulates in its small size a compendium of numerous aesthetic and emotional elements that are captured in a single glance. The blacksmith who designed it showed great delicacy in its execution, and conveyed by means ofs artistic workmanship a welcoming message of closeness to whoever entered the house. He spared no time in crafting this small object which he wanted to transmit a sense of dedication and beauty to those who would see it”. Codes\\NOUNS, “0.8854”, 288, 200, ISM, 11/03/2024 12:46:34.

VERBS

Verbs belong to the second most frequent category after nouns. In order to study them, we will rely on canonical theoretical works in the field of heritage education such as Fontal’s verbal series [2] for the heritage-building process that integrates the sequence of knowing–understanding–respecting–valuing–caring–enjoying–transmitting.

- (a)

- First of all, we begin with the verb “to know” and its relation to the geographical and sociological contexts; in this sense, our research exposes us to the controversy around “Empty Spain” (the depopulation of several of the country’s inland regions) and to the implications of the lack of awareness by the general citizenship of the wealth represented by both tangible and intangible legacy. Indeed, such an absence of recognition means dynamiting the first verb of the sequence and undermining the entire chain. Moreover, this dynamic can steer citizens toward productivist urban environments—spaces that determine what to remember and whom to forget. In the context of current discourses on virtual reality and artificial intelligence, it also molds epistemological boundaries by shaping what knowledge itself should be: what we need to know today and what we had better forget today.

“That stable had always been her home and there she was treated like a member of the family.

Years went by and one day Federica disappeared from our lives, our uncle then thought of buying another she-donkey but times had changed, and cars and tractors were already being used for transportation, loading and farm work.

Since the day when we first saw the empty stable in the village house, we learned to value every time we had looked into the stable to see Federica, the rituals and experiences we had lived and felt through the domestic care and the company of that hard-working and good-natured donkey, such as feeding her, stroking her fur and ears, playing with her and riding her in the mornings—all three siblings—on our way to the orchard, or riding her around the old waterwheel”. Codes\\VERBS, “0.3953”, 149, 129, ISM, 11/03/2024 18:52:31.

- (b)

- With respect to the above-mentioned depopulated territories, the verb “to value” [them] is likewise disparaged, since sociological trends such as the huge emigration that took place in Spain cannot be separated from a propagandistic apparatus, generally veiled, subtle or indirect, that promotes them—or at least did in the past—instilling new aspirations and expectations among the population.

“That stable had always been her home and there she was treated like a member of the family.

Years went by and one day Federica disappeared from our lives, our uncle then thought of buying another she-donkey, but times had changed, and cars and tractors were already being used for transportation, loading and farm work...”. Codes\\VERB, “0.3953”, 149, 129, ISM, 11/03/2024 18:52:31.

- (c)

- The verb “enjoy” underpins the following piece of textual evidence where the participant refers to the meaning of his work in terms of belleza (“beauty”), a noun with special characteristics, because, as [39] argues regarding the relationship between nouns and verbs, both can be predicates and both possess the grammatical category of person, even though they differ in their inflectional categories and in some aspects of their syntax. An important interface between both word classes can be found in the infinitive, a verbal form that possesses a hybrid nature, partaking in verbal and nominal features:

“My heritage bond has to do with this “Winged Ram” that is displayed in the Antique Goldsmithing room at the Provincial Museum of Lugo. The reason is that this piece represents my work: the beauty and the challenges of everyday life”. Codes\VERBS, “0.3953”, 149, 131, ISM, 11/03/2024 19:01:16.

- (d)

- Regarding the verb “to care”, ubiquitous in the debate around the values of our contemporary society and in the discourse of many grassroots group,

“Every day I go out on my terrace and contemplate my staghorn fern (...) My dad always took care of it and gave it all his love while I was growing up preparing for adulthood. My father is gone, and now it is my turn to take care of the fern and pass on his legacy”. Codes \\VERBS, “0.3953”, 149, 121, ISM, 11/03/2024 12:48:31.

And in connection with supremacy—or complementarity—of the value of caring over the value of knowledge, also an object of debate both in epistemology and in contemporary philosophy,

“... It is of vital importance to know heritage in order to understand it and give it its own value. But it is even more important to care for it and respect it for individual and collective enjoyment”. Codes \\VERBS, “0.3953”, 149, 61, ISM, 28/02/2024 18:56:18.

ADJECTIVES

- (a)

- Following Fontal’s [2] fertile sequence, the verb “to enjoy” awakens us to a current sociological trend involving leisure and spare time, which is sometimes challenged in the testimonies collected and constitutes a new reason for awareness and social demands. The following participant exalts a handcrafted piece, and by extension, the informant’s admiration for the craftsman, the trade, and the underlying project-worldview. The mode of expression involves refraining from using adjectives or adverbs of manner—e.g., Spanish adverbs ending in -mente (equivalent to English -ly adverbials). Instead, praise is expressed by means of non-adjectival categories (not variable or subtle): “aesthetic and emotional” nouns and verbs as in “transmitiera dedicación y belleza” (“to transmit a sense of dedication and beauty”) or “no reparó” (“he spared no time”). Only the adjective “pequeño” (“small”) is allowed as a narrative or emotional license, an adjective whose semantic and symbolic power, thus embedded into a scientific and academic context, catapults us to the rest of the arguments we have glossed. Here lies what [39] describes as the main difference between adjectives and nouns: that adjectives, unlike nouns, can be gradable:

“This lock cover encapsulates in its small size a compendium of numerous aesthetic and emotional elements that are captured in a single glance. The blacksmith who designed it showed great delicacy in its execution, and conveyed by means ofs artistic workmanship a welcoming message of closeness to whoever entered the house. He spared no time in crafting this small object which he wanted to transmit a sense of dedication and beauty to those who would see it”. Codes\\NOUNS, “0.8854”, 288, 200, ISM, 11/03/2024 12:46:34.

A similar insight is found in the definition provided by the following participant, where the adjectives stick to the scientific nomenclature: espontáneos (“spontaneous”), intencionales (“intentional”), dinámica (“dynamic”), agradables (“pleasant”) or desagradables (“unpleasant”). Such words are again loaded with symbolic power, although the nouns and verbs remain the dominant categories: la música (“music”); las cargamos de significado (“we load with meaning”); trascienden (“trascend”); vivencias, recuerdos, contextos, experiencias pasadas (“experiencias, memories, contexts, past perceptions”); and construcción y reconstrucción del trinomio: lazos, personas y bienes (“construction and reconstruction of the trinomial: links, people and goods”). The profusion of nouns and verbs is remarkable in the testimony of this Ibero-American participant whose outstanding historical–geographical bonds to heritage would appear to justify word choices inclined towards the adjectival, the expressive, and the connotative. Still, these factors do not quite translate into a coherent lexical selection, which is instead influenced by the formal paradigm of the MOOC course:

“Heritage is a construction anchored on the bonds, both spontaneous and intentional, between society and the assets that make up that heritage. These are interwoven in a dynamic way as a result of the values that we project on tangible and intangible assets. This is why heritage reminds me of music, which we load with meaning, semantics, so that it trascends beyond the level of a series of musical notes. Heritage assets transport us to experiences, memories, contexts, past perceptions, emotions and feelings that can be pleasant or even unpleasant. This is where heritage education plays a decisive role, since it becomes a compass for us to materialize the construction and reconstruction of the trinomial: ties, people and goods”. Code\\ADJECTIVES, “0.3448”, 100, 35, ISM, 28/02/2024 14:00:35.

- (b)

- To provide further emphasis on the concept of caring, we find in this evidence a number of key adjectives—Sencilla/incalculable/importante (“Simple/priceless/important”)—which explicitly voice the participant’s willingness to care for her grandparents as a virtuous landmark in a scale of values that dissents from the dominant one:

“One part of my most personal heritage is the bracelet my grandma gave me when I graduated. She knew that there was an added personal effort in all those years, and how difficult some moments had been. That’s why, the day I presented my Bachelor’s Thesis, she showed up with this bracelet that was related to my course of studies, with little earth globes for beads. It is a very simple object, but for me it is priceless because of what it means to both of us and what it represents. Sure I have many more bracelets, some of them equally important, gifts from friends, etc. but none of them conveys so many emotions to me as this one. Every time I look at it, I remember how important grandparents are and how much we have to take care of them and enjoy their company”. Codes\\ADJECTIVES, “0.3448”, 100, 77, ISM, 11/03/2024 13:34:48.

ADVERBS

For this category, which is the least used in the statements by participants as they define heritage, we highlight the correlations between all the proposed categories, noting that they all correlate highly and positively (see Table 3):

Table 3.

Correlations between categories of analysis.

This Pearson correlation coefficient shows us that definitions normally use all four categories together, i.e., each definition resorts to nouns in combinations with adjectives, with verbs and with adverbs.

- (a)

- Again, we turn to the verb “to enjoy”, which, together with the verb “to care”, implies a questioning of a worldview that worships speed, haste, and multitasking as values and signs of the times. The participant brings in the following evidence a critical significance to their private time for self-development, social relations, and enjoyment. Let us remember that the difference between adjectives and adverbs proposed by [39] hinges on the consideration that adjectives are predicates can be inflected and regularly modify nouns. The adverbs “constantemente” (“constantly”) and “bien... bien” (“either... or...”) struggle to transcend their limited role in the discourse:

“I am a curator and restorer of cultural property and as such I find this a really big question, since I am constantly in contact with all kinds of heritage. But if I look at my most private and personal side, I would say that my personal heritage would be music and what connects me to it. My father has always had all types of music on his speakers, as has my mother. My brother has played in several music bands. Without being aware of it, I created my own social group around music, either by sharing tastes, or by being socially active in the world. Taking all of this into account, I have no doubt that my most precious asset, after my own artistic creations, would be the CD collection of my favorite music band”. Codes\\ADVERBS, “0.1175”, 29, 16, ISM, 11/03/2024 13:59:19.

4. Discussion

Despite the difficulty involved in establishing a consensual and uniform definition [28] for the concept of cultural heritage, given the huge diversity of individuals that make up the citizenry (regarding gender, age, place of residence, educational level, cultural background, etc.), the analysis based on text mining constitutes a very interesting strategy in order to arrive at conclusions in this regard. Indeed, it enables us to dissect individual perceptions and probe into what the different lexical categories conceal, evidencing hidden patterns, concordances, concurrences and key terms within the selected context.

In our analysis, we have been able to verify that the statistically least represented lexical categories strive to fill themselves with meaning and symbolic power in the context of heritage; in parallel, the informants themselves also try to fill their lives with meaning by making heritage assets take centerstage in their lives, in view of the importance they attach to them in order to reconnect with their own identity, survive in an environment which is often far from idyllic, or return to what they perceive as happier times.

Another relevant conclusion concerns the lexical “uneasiness” of the adjective and the adverb, which, as we saw, seek to transcend by means of syntactic and semantic expansion; in this way, they contribute new meanings that, beyond the purely literal and obvious, add enriching nuances to a discourse on heritage where otherwise the noun and the verb play a hegemonic role. This is worth noting, especially if we take into account that heritage education, as a discipline, operates along a verbal series [2] that clearly defines a sequence in the process of heritagization experienced by people in their relationship with cultural assets. In this sense, the less predictable capitulation of the verb before the statistics of the noun also constitutes a relevant finding.

From a sociolinguistic and semiotic perspective, it is observed that the expansion of the use of the adjective and the adverb in the discourses analyzed has a significant correlation with the emotional approach supported by our research group. This approach, in line with a dynamic and emancipatory conception of heritage, seeks to dissociate itself from essentialist and static visions, as well as from the traditional social structures that have historically legitimized it. The predominance of descriptive and modulating structures (adjectival and adverbial) reflects a discursive intention oriented towards the subjectivization of the heritage narrative and the construction of affective links with cultural assets. This growing plasticity and intentionality of adjectives and adverbs corresponds to the contemporary multiform diversity in the concept of Heritage, both geographical—throughout Europe [29]—and typological according to sex, knowledge, age, and culture [25], a diversity that we announced in the introduction. This supports the trend toward the democratization of memory, which is an issue of our article [14,15].

In contrast, there is a notable recession in the use of verbal forms, which can be interpreted as a linguistic symptom of the absence of a pragmatic or processual dimension in the discursive formulation of heritage. This attenuation of linguistic action indicates that the “first conceptual battle”—focused on categorial redefinition—is not yet accompanied by the necessary performative articulation that verbs, as carriers of dynamism, make possible. This lack suggests a weakness in the operational projection of heritage discourse, which needs to be remedied through educational praxis. Following this line of argument, the related underlying question is the very role of the contemporary university institution, which on the one hand can convince and win in conceptual battles, but could better guide and outline a dynamic transfer of knowledge with respect to the dynamization of the population and the synergy with cultural agents of all kinds. For this task of dynamic knowledge transfer, the university can count precisely on the window of opportunity offered by the political power that is currently given to heritage cataloging and the enhancement of heritage as a systemic plus of the territories [6,7].

In this sense of dynamization by means of verbal action, Fontal’s methodological proposal, expressed in the circular and cumulative sequence “Knowing to Understand, to Respect, to Value, to Care, to Enjoy, to Transmit, to Know”, offers a framework for educational action that incorporates progressivity and feedback as formative principles. Each verb in this sequence represents a specific social action: to know refers to processes of access to information; to understand, to the critical internalisation of meanings; to respect, to the acceptance of heritage diversity; to value, to the construction of judgement; to care, to ethical involvement; to enjoy, to positive emotional appropriation; to transmit, to intergenerational continuity; and again to know, to the cycle of ongoing heritage education. This sequential structure endows the heritage discourse with an active dimension, projecting its conceptualization towards transformative educational action.

5. Conclusions

Our study ultimately highlights the informants’ own discomfort with the pressures and repressions that mediate the concept of heritage, which severally originated in the institutional, the societal (the social constructs), the seriality of urban planning and technology, the loss of conviviality, the devaluation of art and craftsmanship in favor of a consumerist paradigm of leisure and entertainment that also serializes enjoyment to the detriment of originality, the impoverishment of language, the proliferation of ‘noise’—in a broad and philosophical sense—the degradation of tangible and intangible heritage or the neglect and lack of protection inflicted on territories. All of these, in turn, point to the several directions in which we must work for the conservation and bequest of our heritage, especially by means of interventions based on the education of individuals. And in this education, we must include language, with its norms, enrichments and poverties that society imprints on it.

In any case, the conceptual plurality of heritage is so ubiquitous, both in the diversity of existing definitions and in the enormous taxonomy of uses, interpretations, perceptions and contexts involved, that it demands that research on heritage education should be continued by assuming perspectives of a multidimensional and inclusive nature.

Our results bring forward a transformative vision in the field of heritage education, especially in how MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) can shift the paradigm from a legacy-based approach to a relational, participatory model. Our paper critiques the traditional, static conception of heritage as something that is passively received—typically framed as a legacy of monuments, traditions, or artifacts passed down through time. Instead, we argue for a dynamic understanding of heritage as a social construct based on emotional, cultural, and community bonds.

One of the key changes we propose is the integration of community narratives into MOOC content, where learners are not passive recipients of knowledge but active participants and co-creators of heritage meaning. This implies the inclusion of local testimonies, memory archives, and social media interactions to create a living dialogue between learners and heritage.

We emphasize the use of transmedia storytelling, encouraging multiple entry points for engagement (videos, podcasts, blogs) to foster multisensory and multidimensional learning. Another critical innovation is the redesign of evaluation: instead of traditional assessments, we promote reflective tasks where learners connect heritage topics to their personal and community experiences.

We also suggest embedding emotional learning strategies to deepen identification with cultural heritage and foster empathy and inclusion. In terms of structure, we propose modular flexibility in MOOCs, enabling learners to explore heritage topics from various disciplinary and cultural perspectives.

Through these changes, we seek to redefine MOOCs as open cultural laboratories, where heritage education becomes a participatory, evolving, and meaningful experience rooted in collective memory and contemporary identity construction. This shift supports a view of heritage not as a frozen legacy, but as an ongoing, shared link between past, present, and future.

In my exploration of dynamic MOOCs and their potential in heritage education, I focus on shifting the concept of heritage from an outdated, legacy-based model to one rooted in personal and emotional connection. I advocate for MOOCs that are not simply platforms for content delivery but spaces of active, collaborative learning. One of the core changes I promote is learner-centered design, where users navigate flexible pathways instead of following a rigid, hierarchical structure. This empowers them to engage with heritage on their own terms.

I also emphasize the importance of personal storytelling and lived experiences within course activities. Learners are encouraged to reflect on their cultural identities and share local narratives, transforming the learning space into a mosaic of perspectives. Another key shift is the use of peer-to-peer interaction, not just as a supplement but as a central pedagogical tool. Through dialogue, debate, and collaborative tasks, learners build meaning collectively.

To support these changes, I integrate adaptive technologies and real-time feedback mechanisms to make the MOOC environment responsive and emotionally resonant. Evaluation is also transformed—from quizzes to reflective journals, multimedia projects, and co-assessment.

My goal is to dissolve the distance between learner and content. By enabling users to see themselves in the material, heritage becomes not a static inheritance but a living connection, shaped by memory, identity, and shared human experience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.-G. and O.F.M.; methodology, I.S.-M.; software, I.S.-M.; validation, I.S.-M. and O.F.M.; formal analysis, I.S.-M.; investigation, I.S.-M. and O.F.M.; resources, A.G.-G.; data curation, P.d.C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.d.C.M.; writing—review and editing, I.S.-M.; visualization, O.F.M., I.S.-M., P.d.C.M. and A.G.-G.; supervision, P.d.C.M. and O.F.M.; project administration, O.F.M.; funding acquisition, O.F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the project PID2023-147913OB-I00, funded by MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER, UE.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of the project “Heritage communities as educational agents in rural environments: valuation, conservation and transmission of intangible cultural heritage CoPER-PCI” with code PID2023-147913OB-I00, a project founded by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (MCIU), the State Research Agency (AEI) and the European Union (FEDER). During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used Nudist.vivo.11 and Voyant Tools for data analysis purposes. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Pérez-Rodríguez, N.; Navarro-Medina, E. Itinerarios de cambio en las concepciones de los estudiantes del Grado de Educación Primaria sobre los problemas sociales y patrimoniales relevantes. In Repensar el Currículum de Ciencias Sociales: Prácticas Educativas Para una Ciudadanía Crítica; Cuenca-López, J.M., Fraga-Hernández, N., Eds.; Tirant Humanidades: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Fontal, O. La Educación Patrimonial: Definición de un Modelo Integral y Diseño de Sensibilización. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Oviedo, Asturias, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides, J. Siglo XXI: Nuevos significados del patrimonio cultural y del desarrollo. In Libro de Actas del IV Congreso Internacional de Patrimonio Cultural y Cooperación al Desarrollo: 16, 17 y 18 de Junio de 2010; Ordaz, C., Ed.; Comité Científico del IV Congreso de Patrimonio Cultural y Cooperación al Desarrollo, 2010; pp. 335–342. Available online: https://es.scribd.com/document/265598280/SIGLO-XXI-Nuevos-Significados-Del-Patrimonio (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Josefsson, J.; Aronsson, I.L. Heritage as life-values: A study of the cultural heritage concept. Curr. Sci. 2016, 110, 2091–2098. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309722591_Heritage_as_Life-ValuesA_Study_of_the_Cultural_Heritage_Concept (accessed on 25 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.; Bustos, V. Valparaíso: El derecho al patrimonio. Antropol. Del Sur 2015, 2, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selicato, F. The concept of heritage. In Cultural Territorial Systems: Landscape and Cultural Heritage as a Key to Sustainable and Local Development in Eastern Europe; Rotondo, F., Selicato, F., Marin, Y.J., López, V., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähdesmäki, T.; Čeginskas, V.L. Conceptualisation of heritage diplomacy in scholarship. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2022, 28, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Z. ¿Cómo acercar los bienes patrimoniales a los ciudadanos? Educación Patrimonial, un campo emergente en la gestión del patrimonio cultural. Pasos Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2009, 7, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, R.M. Identidades territoriales y patrimonio cultural: La apropiación del patrimonio mundial en los espacios urbanos locales. Revista F@ro 2005, 2, 289–306. Available online: https://www.revistafaro.cl/index.php/Faro/article/view/822/961 (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Ávila, R.M.; Borghi, B.; Mattozzi, I. L’educazione Alla Cittadinanza Europea e la Formazione Degli Insegnanti. Un Progetto Educativo per la “Strategia di Lisbona”: Atti XX Simposio Internacional de Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales. Patron Editore. 2009. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/30945633/_Leducazione_alla_cittadinanza_europea_e_la_formazione_degli_insegnanti_Un_progetto_educativo_per_la_strategia_di_Lisbona_a_cura_di_Rosa_M_Ávila_Beatrice_Borghi_e_Ivo_Mattozzi_Pàtron_Bologna_2009 (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Aparicio, W.O. Concepto de cultura en antropología: El cambio cultural y social. Rev. Int. Filos. Teórica Práctica 2021, 1, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, J.M. Escuela, patrimonio y sociedad. La socialización del patrimonio. Univ. Esc. Sociedad 2016, 1, 22–41. Available online: https://revistaseug.ugr.es/index.php/revistaunes/article/view/12148/10037 (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Gascón, J. El turismo comunitario como estrategia para activar el patrimonio en zonas rurales: Límites y riesgos. INPC Rev. Del Patrim. Cult. Ecuador 2014, 6, 10–21. Available online: https://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/150011/1/658238.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2024).

- González-Varas, I. Patrimonio Cultural. Conceptos, Debates y Problemas; Ediciones Cátedra (Grupo Anaya, S.A.): Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sáez-Rosenkranz, I.; Prats, J. Memoria Histórica y Enseñanza de la Historia; Ediciones Trea: Gijón, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontal, O. Educación Patrimonial Centrada en los Vínculos: El Origami de Bienes, Valores y Personas; Ediciones Trea: Gijón, Spain, 2022; Available online: https://www.educacion.gob.es/teseo/mostrarSeleccion.do (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Mosler, S. Everyday heritage concept as an approach to place-making process in the urban landscape. J. Urban Des. 2019, 24, 778–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontal, O. Estirando hasta dar la vuelta al concepto de patrimonio. In La Educación Patrimonial. Del Patrimonio a las Personas; Fontal, O., Ed.; Ediciones Trea: Gijón, Spain, 2013; pp. 9–22. Available online: https://moodle2023-24.ua.es/moodle/pluginfile.php/270655/mod_resource/content/1/Estirando%20hasta%20dar%20la%20vuelta%20al%20patrimonio.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Loulanski, T. Revising the concept for cultural heritage: The argument for a functional approach. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2006, 13, 207–233. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/231887932_Revising_the_Concept_for_Cultural_Heritage_The_Argument_for_a_Functional_Approach (accessed on 10 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A. Patrimonio para todos… pero ¿quiénes somos todos? Pensamientos, palabras y actuaciones inclusivas. In Guía Práctica Para el Desarrollo de Actividades de Educación Patrimonial; Fontal, O., Ed.; Consejería de Cultura y Turismo de la Comunidad de Madrid, Dirección General de Patrimonio Cultural: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 59–71. Available online: https://www.comunidad.madrid/sites/default/files/version_web_como_educar_en_el_patrimonio_capitulo_4_patrimonio_para_todos.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Fontal, O.; Ibáñez-Etxeberria, A.; Martín, L. (Eds.) Reflexionar desde las experiencias. Una visión complementaria entre España, Francia y Brasil. In Actas del II Congreso Internacional de Educación Patrimonial; IPCE/OEPE: Calgary, AL, Canada, 2014; Available online: https://www.cultura.gob.es/planes-nacionales/dam/jcr:90cfb441-c07f-4455-8032-1d6ea3074055/actas-ii-congreso-internacional-ep.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Diaz Cabeza, M. Criterios y conceptos sobre el patrimonio cultural en el siglo XXI. Ser. Mater. Enseñanza 2010, 1, 1–25. Available online: https://www.ubp.edu.ar/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/112010ME-Criterios-y-Conceptos-sobre-el-Patrimonio-Cultural-en-el-Siglo-XXI.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Penate Villasante, A.G. Proposal of a concept on heritage interpretation. Atenas 2019, 1, 99–113. Available online: https://atenas.umcc.cu/index.php/atenas/article/view/360/596 (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Morón, H.; Wamba, A.M.; Aguaded, J.S. Importancia de la percepción de los riesgos ambientales en la formación inicial del profesorado. In Ciencias Para el Mundo Contemporáneo y Formación del Profesorado en Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales: Actas de los XXIII Encuentros de Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales; Jiménez, M.R., Ed.; Editorial Universidad de Almería: La Cañada de San Urbano, Spain, 2008; pp. 1196–1209. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263902408_IMPORTANCIA_DE_LA_PERCEPCION_DE_LOS_RIESGOS_AMBIENTALES_EN_LA_FORMACION_INICIAL_DEL_PROFESORADO (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Fernández Salinas, V.; Romero Moragas, C. El patrimonio local y el proceso globalizador. Amenazas y oportunidades. In La Gestión del Patrimonio Cultural. Apuntes y Casos en el Contexto Rural Andaluz; Alonso Sánchez, J., Castellano Gámez, M., Eds.; Asociación Para el Desarrollo Rural de Andalucía: Granada, Spain, 2008; pp. 17–29. Available online: https://idus.us.es/server/api/core/bitstreams/37b7ddf4-e555-48af-9b7a-cfa21d3009ff/content (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Morón, H.; Morón, M.C. ¿Educación Patrimonial o Educación Ambiental?: Perspectivas que convergen para la enseñanza de las ciencias. Rev. Eureka Sobre Enseñanza Divulg. Las Ciencias 2017, 14, 244–257. Available online: https://revistas.uca.es/index.php/eureka/article/view/3013/3038 (accessed on 15 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Morón-Monge, H.; Monge, M.D.C. La evolución del concepto de patrimonio: Oportunidades para la enseñanza de las ciencias. Didáctica Las Cienc. Exp. Soc. 2018, pp. 83–98. Available online: https://idus.us.es/server/api/core/bitstreams/ff2b6c0b-0411-45d2-8c08-26eabb00c3fb/content (accessed on 26 March 2024).

- Petti, L.; Trillo, C.; Ncube, B.C. Towards a shared understanding of the concept of heritage in the European context. Heritage 2019, 2, 2531–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Pérez, R. Educación Artística y Comunicación del Patrimonio. Arte Individuo Sociedad 2012, 24, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Moreno-Navarro, A. Patrimoni, Memòria o Malson? Memoria 1990–1992. Diputación de Barcelona; Servei de Patrimoni Arquitectónic Local: Barcelona, Spain, 1995; ISBN 84-7794-405-9. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.; Huberman, M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2013; Available online: https://www.metodos.work/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Qualitative-Data-Analysis.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed.; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, T.; Richards, L. Nudist; [computer program]; La Trobe University: Melbourne, Australia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, S.; Rockwell, G. Voyant Tools. 2016. Available online: https://voyant-tools.org (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Tandel, S.S.; Jamadar, A.; Dudugu, S. A Survey on Text Mining Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th International Conference on Advanced Computing & Communication Systems (ICACCS), Coimbatore, India, 15–16 March 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Bhatia, P.K. Text mining: Concepts, process and applications. J. Glob. Res. Comput. Sci. 2013, 4, 36–39. Available online: https://www.rroij.com/open-access/text-mining-concepts-process-and-applications-36-39.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- RAE Real Academia Española. Diccionario de la Lengua Española. 2014. Available online: https://dle.rae.es/patrimonio?m=form (accessed on 26 April 2024).

- Bosque, I. Las Categorías gramaticales: Relaciones y diferencias. Síntesis. Traslaciones Rev. Latinoam. Lect. Escr. 2015, 9, 306–311. Available online: https://revistas.uncu.edu.ar/ojs/index.php/traslaciones/article/view/5971 (accessed on 26 April 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).