2. State of Art

Regarding the images for the study of the urban planning of Seville and Triana in the 16th century, it is more than significant that from 1560 onwards, a production of graphic representations of the city began, mostly of a naturalistic nature, which marked a milestone in the history of Sevillian urban iconography. Except for the models of the main altarpiece of the cathedral, these representations are the first of their kind in the city and are fundamental visual documents for understanding the evolution of Seville’s urban landscape. Among the most outstanding works of this period are the panoramic views produced by artists such as Joris Hoefnagel (

Figure 3) and Anton Van der Wyngaerde (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), who captured the city in a precise manner, drawn from life. Another representative example of this graphic tradition is the print by Ambrosio Brambilla (

Figure 6), produced in 1585, which presents a general panorama of Seville from the west, with Triana in the foreground. All these depictions not only offer a detailed view of the urban environment, but also give particular prominence to Triana, an aspect that is especially evident in one of Wyngaerde’s views. This is exceptional in that it shows Triana with a singular focus that underlines the importance of the neighbourhood in the context of the city.

These views are not only valuable as visual documents, but also as a means of exploring how artists of the time perceived and presented the urban development of Seville, with a particular focus on Triana. Their contribution to the study of the city in the 16th century is essential, as they offer a graphic perspective that complements other types of historical records and allows for a deeper understanding of the evolution of urban spaces, their organisation, and the relationship between the different neighbourhoods and the Guadalquivir River.

Also, among the main bibliographical sources for the study of urban representation in the 16th century, works such as

La representación de la ciudad en el Renacimiento by Arévalo Rodríguez [

11] or

La imagen de la ciudad en la Edad Moderna edited by Cámara Muñoz and Gómez López [

12] stand out. In addition,

Ciudades del siglo de oro: Las vistas españolas de Anton van den Wyngaerde edited by Kagan [

13], together with the facsimile editions of

Civitates Orbis Terrarum by Max Schefold [

14] and Skelton [

15], are essential references. For the Sevillian context, the work of Díaz Zamudio and Gámiz Gordo on

Sevilla [

16] is fundamental and complements this perspective. Finally,

Iconografía de Sevilla. 1400–1650 by Cabra Loredo and Santiago Páez [

17], brings together many views of Seville.

The systematic analysis of Seville’s periphery was first addressed in

Sevilla extramuros. La huella de la historia en el sector oriental de la ciudad, edited by Valor Piechotta and Romero Moragas [

18]. Other relevant studies on 16th-century Seville include

Historia de Sevilla. La ciudad del Quinientos by Morales Padrón [

19] and

El urbanismo de Sevilla durante el reinado de Felipe II by Albardonedo Freire [

20]. Finally, the work by Gámiz Gordo and Barrero Ortega,

Imágenes de un patrimonio desaparecido: la Puerta de Triana en Sevilla [

21], is of particular relevance.

Likewise, the study of the city’s urban and rural infrastructures is complemented by works such as

La obra hidráulica en la cuenca baja del Guadalquivir by Moral Ituarte [

22]. Regarding fortifications, the

Estudio histórico-arqueológico de las puertas medievales y postmedievales de las murallas de la ciudad de Sevilla by Jiménez Maqueda [

23] provides a detailed analysis. In relation to the religious buildings found outside the city walls,

Patrimonio y ciudad. El sistema de los conventos de clausura en el centro histórico de Sevilla by Pérez Cano [

24] offers a complete perspective. On the other hand,

Los hospitales de Sevilla by Chueca Goitia et al. [

25] focuses on the hospital institutions of the 16th century. Finally, the study of the rural landscape of Seville is found in

El paisaje rural sevillano en la Baja Edad Media by Montes Romero-Camacho [

26].

For the analysis of the dwelling and urban structure of Seville and Triana, various documentary sources were consulted, including archives such as the Archivo de la Catedral de Sevilla Seville Cathedral Archive (ACS), the Archivo de la Diputación Provincial de Sevilla Provincial Council Archive of Seville (ADPSE), and the Archivo Histórico Provincial de Sevilla Protocolos Notariales Provincial Historical Archive of Seville Notarial Protocols (AHPSPN).

Particularly noteworthy are the surveys of houses, some of them with plans, which provide information on the tenants, trades, dimensions, and construction characteristics of the properties. More than a thousand surveys have been reviewed, including descriptions of houses belonging to the Cathedral and to the hospitals of Las Bubas, El Cardenal, and Las Cinco Llagas (16th-century surveys), as well as of the reduced hospitals (beginning of the 17th century, Amor de Dios and Espíritu Santo hospitals), many of which were illustrated by Vermondo Resta. In addition, other surveys of the hospital of Misericordia (17th century) have been included, allowing the identification of 44 properties in the collación quarter of Triana.

Apart from this documentation, chronicles and publications, such as

Curiosidades antiguas sevillanas by Gestoso Pérez [

27],

Curiosidades sevillanas by Álvarez Benavides [

28],

Triana de puente a puente (1147–1853) by Acosta Domínguez [

29], and

Triana: el caserío. Calles, plazas, sitios y lugares by Macías Míguez [

30], the latter based on the population lists of neighbours from the 15th century to the 19th century, have been reviewed.

Finally, the academic research of Díaz Garrido [

31], whose thesis

Triana y la orilla derecha del Guadalquivir was awarded the Focus-Abengoa prize in 2005, stands out. Her study on the residential typology of the

corral de vecinos, a traditional Spanish communal house in Triana, and her coordination of the

Aula Digital de la Ciudad have been fundamental to understanding the urban evolution of the neighbourhood [

32].

3. Historical and Urban Context of Triana

The evolution of the urban form of Triana, when adjusted to the specific context of this article, can be divided into three stages. The first corresponds to the Islamic period, when the arrabal (a peripheral neighbourhood or suburb found outside the city walls) were typically inhabited by working-class residents, artisans, and marginalised communities. These districts often developed organically beyond the official urban limits and played a crucial role in the city’s economic and social life. This was followed by a late medieval stage, crucial for the consolidation of the historic arrabal, extending from the Christian conquest until the end of the 15th century. The third stage covers the 16th and 17th centuries, when the city, along with Triana, reached its peak—linked to the discovery of America—followed by a later period of economic decline. This chronological sequence is the relevant one for our analysis, leaving aside other traditional divisions of urban history.

In the first phase, the Islamic period, the foundations were laid for later growth, with Triana becoming a strategic and significant point in the urban development of the city of Seville. From this time onwards, Triana was intimately linked to the River Guadalquivir, the course of which defined its geographical importance and economic value. On the opposite bank to the Arenal, i.e., on the right bank of the river, the area most affected by the current, was the arrabal of Triana opposite the city. This urban proto-nucleus developed parallel to the riverbank, articulated by two main routes that were based on two different land roads: San Jacinto Street, as part of the road to San Juan de Aznalfarache, and Castilla Street, as an extension of the road to Castilleja de la Cuesta.

From this location, the territory of the arrabal extended northwards to the Monastery of Santa María de las Cuevas, westwards to Madre Vieja (the former course of the River Guadalquivir within the city), and southwards to the stretch of the river between Point of Los Remedios and Point of Tablada. This area, rich in fertile land and occupied by vegetable gardens and orchards, was known as the Vega de Triana. This flat landscape was crossed by paths that connected Seville, through Triana, with the nearby towns of the Aljarafe-Santiponce, Camas, Castilleja, Tomares, and San Juan (by a radial network of paths running north–south that crossed the river, and the plain in a transverse direction). This network was densified in the immediate surroundings of the arrabal by minor paths, used to access the many vegetable gardens.

To this geographical and urban description, we must add two fundamental elements in the original structure of the arrabal, which refer to its origin and its relationship with the location: the old Triana castle, next to the future bridge, today the Triana market; and the Cava, now Pagés del Corro Street, which corresponds to an Islamic moat that surrounded the suburb for defensive purposes. The presence of both castle and moat made the defence of Triana an exceptional case, since, although found in a suburb, they would have formed part of the defensive system of Seville.

As Valencia points out, until the 11th century, Triana must have been at most a small farm estate, beginning to grow from the time of the

Taifas and reaching a greater extension in the Almohad period, when the capital overflowed the Almoravid enclosure and Triana was boosted by the boat bridge that extended in front of this neighbourhood, which made it an obligatory point of access from the Aljarafe [

33].

From this time onwards, references to Triana as a village or recreational town began to appear in Muslim chronicles, and as an arrabal in Christian sources. A particularly relevant moment in this evolution was when Seville became the capital of the Almohad empire, and the construction of a pontoon bridge was ordered, inaugurated in 1171, a key element in the urban development of the suburb. There are also Arab references to the port of Seville, where constructions are described that extended along both banks of the Guadalquivir River, and, in terms of industry, it was when pottery activity in Triana began to be documented.

Although the

arrabal had its origins in the Islamic period, it can be affirmed, e.g., by Díaz Garrido [

31], that a second foundation of Triana took place during the late Middle Ages. The Christian conquest marked a new milestone in the town’s history with the construction of the church of Santa Ana and the creation of the town around it. This foundation must have responded, if not to a real need of the existing population, then to factors of a representative and defensive nature linked to the control of the port.

The late medieval period, from the Christian conquest of Seville in 1248 until the end of the 15th century, was crucial for the consolidation of the arrabal as a neighbourhood. At this time, Triana underwent a profound transformation. Its status as an arrabal was strengthened and it evolved into an urban centre with its own identity, even being recognised as a guarda y collación de Sevilla (guard post and quarter of Seville). The neighbourhood became important not only as a residential area but also as a commercial and productive enclave, acting as a strategic link between Seville and its immediate surroundings. In this context, Triana was a centre of craft, agricultural, and industrial activity, with a population whose economy was centred around the river, the cultivation of the land, and the dynamics of river trade.

After the conquest and the later process of repartimiento, Triana is often mentioned in historical sources. Its prominent role during the siege of Seville explains the frequent mention of the suburb in relation to two key elements in the defence of Seville: the castle and the bridge. Through the Libro del Repartimiento, and from the description of the vegetable gardens, the outline of the arrabal of Triana can be delineated, extending from the road to Sanlúcar in the north to the road to San Juan de Aznalfarache in the south. The Cava also appears in these descriptions, although without sufficient detail to characterise it. The last element mentioned in these sources is the almona (soap factory), the importance of which would later be consolidated.

Starting from the oldest and most structuring element of the arrabal, the current Castilla Street predates both the bridge and the castle. The plan of the new town must have been based on an elementary layout articulated around three main components: a street laid out along the main axis, a square, and a church, forming a longitudinal layout.

This new urban organisation was based on an unpopulated territory, although conditioned by the existence and limits of the Islamic arrabal. The main street, the axis of the settlement, was arranged tangentially to these limits, around the castle, but without showing direct continuity with the earlier routes. On both sides of the main axis, built-up strips of different widths were arranged, determined by the proximity of the river on one side and the presence of the church on the other. The planning of this built-up strip, characterised by a regular distribution of transversal streets and plots, could be interpreted as evidence of an interest in generating a continuous image of the front of the town that was visible from Seville.

In this sense, the construction of the church of Santa Ana and the shaping of the town around it are undoubtedly the most significant event in the urban development of this period. It is worth noting the fortified nature of the original church, of which traces remained until the 18th-century renovations, when the church lost its crenellated features [

31].

At the end of the 15th century, Triana experienced greater growth than the rest of the city, driven by its privileged location next to the port and by the boom in its industry, especially ceramics. In this context, a more spontaneous settlement appeared on the

Cava, which acted as a structuring element. Two main sectors were formed on either side of San Jacinto Street which began to play a new role as an urban boundary. The church of Santa Ana and the associated village were consolidated as the nerve centre of the neighbourhood, around which later growth would be concentrated. This expansion tended towards the south, favoured both by the location of the different port docks and by the appearance of dwellings also on the other side of the

Cava (

Figure 7).

During the 16th and 17th centuries, Triana experienced a period of splendour, driven largely by the discovery of America and the subsequent boom in trade with the Indies. As Morgado points out, by the end of the 16th century, Triana had become a key warehouse for goods such as tar, nails, oars, and various equipment for navigation [

34]. This underscores not only Triana’s significance in maritime and commercial activities, but also the growing prominence of sailors, captains, and shipmasters who settled in the area, drawn by the economic opportunities stemming from the port’s dynamic role. This connection to the maritime world was further reflected in local industries producing goods essential for navigation, such as gunpowder, biscuit (a staple food for crews), and ceramics, much of which was destined for transatlantic trade [

35].

The fluid connection between Seville and Triana through the Pontoon bridge was essential for the exchange of goods and people, complemented by a road network linking the neighbourhood to surrounding territories on the Iberian Peninsula [

36]. Industry and commerce played crucial roles in Triana’s growth, consolidating the neighbourhood as both a production hub and a strategic point for trade routes extending both across the peninsula and to the Americas.

Fully integrated into the urban life of Seville, Triana gradually developed a reputation as a populous, industrial suburb, known for its potters and sailors. Its privileged location by the river enabled the development of infrastructure and industries typically not found in the city’s interior, such as secondary docks, shipyards, and factories. Notably, the neighbourhood became home to traditional industries like soap-making and pottery, as well as newer ones, including gunpowder mills for the Navy. The location of these mills near the port was strategic, although they had to be relocated several times due to explosions (

Figure 8).

In addition to its port and industrial function, Triana was home to other important institutions. One of the most outstanding was the seat of the Tribunal of the Holy Office, installed by the Catholic Monarchs in the castle of Triana from 1481 onwards. In 1569, the Universidad de Mareantes (University of the Men of the Sea), heir to the medieval Colegio de los Comitres (School of the Shipmen), was founded as a reference point for seafaring professionals. This university brought together the sailors, masters, and pilots who formed part of the structure of the maritime trade to the Indies. The university was present in Triana until the end of the 17th century, in the building where the Casa de las Columnas (House of Columns) stands today.

Economic growth brought with it a considerable demographic increase. At the end of the 16th century, Triana had an estimated population of 4000 inhabitants, a figure that, according to estimates, would be equivalent to around 20,000 today. In this context, more than 2500 houses were built in Seville, of which more than 900 were in Triana [

38]. This dynamism was also reflected in the religious and welfare sphere, with the founding of many convents and hospitals motivated by the populous nature of the neighbourhood. In the 16th century, the convents of Santa María de la Victoria, Espíritu Santo, Nuestra Señora de la Consolación, and Nuestra Señora de los Remedios were founded, and in the 17th century, the Convent of San Jacinto. Except for the Espíritu Santo, all of them were outside the limits on the other side of the

Cava. There was also a proliferation of hermitages and chapels, such as those of San Sebastián, Los Mártires, La Encarnación, and La Candelaria, and small-scale hospitals associated with them, the most important of which were the hospitals of Santa Ana and Santa Catalina (

Figure 9).

Triana was in constant interaction with other communities, especially with the Portuguese. According to Morales Padrón [

19], the Portuguese presence was notable, and the cooperation between Castilian and Portuguese sailors played an essential role in Atlantic expansion. This alliance favoured commercial exchanges and consolidated Triana as one of the most important seafaring districts on the peninsula. Urban expansion was also influenced by the arrival of new settlers, such as the Moors expelled from Granada by Philip II. At the end of the 16th century, it is estimated that the Moorish population in Seville reached 7000 people, many of whom settled in Triana, significantly influencing its social and cultural composition.

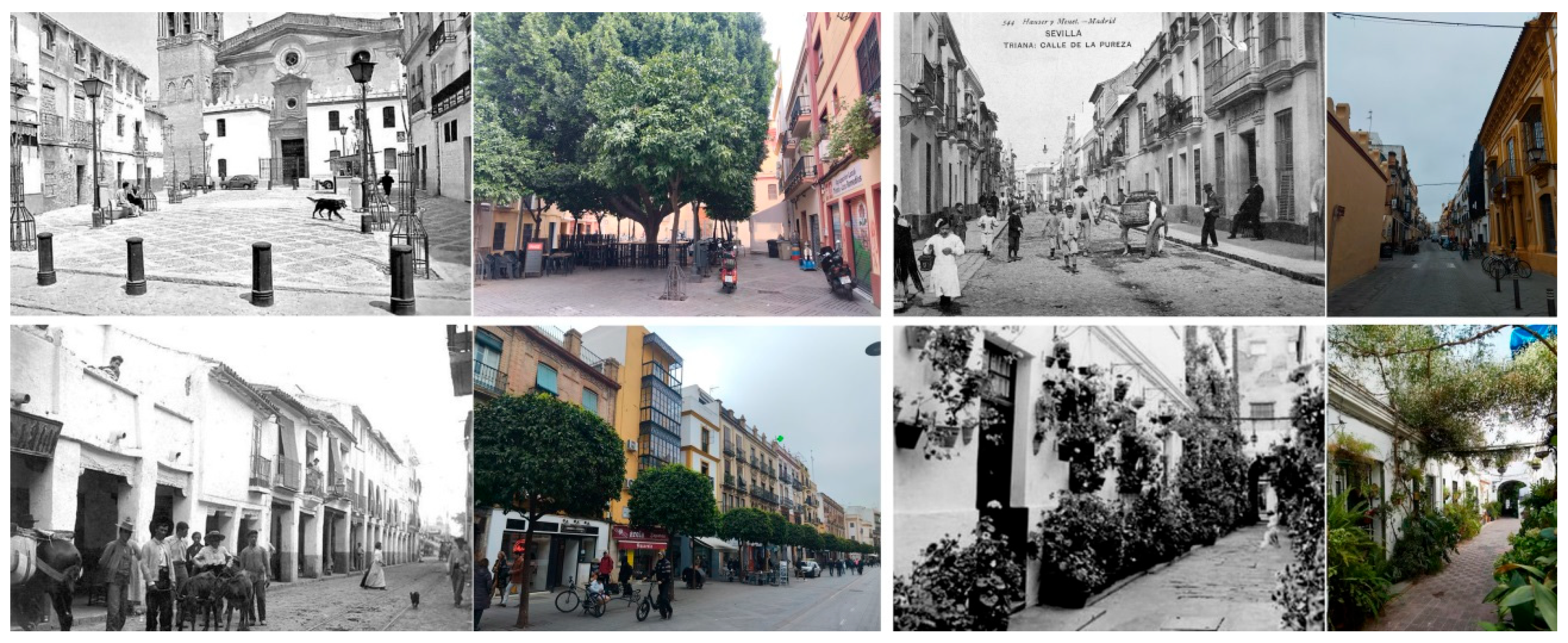

This notable urban and functional growth led to a profound transformation of Triana, although no specific records of planning initiatives have been preserved, as is the case with Seville. The only documented interventions correspond to the attempt to replace the Pontoon Bridge (

Figure 10) and the proposal by the Count of Salvatierra in 1615 to provide Triana’s dwellings with marble arcades [

31]. The urban morphology of Triana would be characterised from this time onwards by a complex grid made up of houses, corrals, shops, and inns, especially concentrated from this time onwards in Altozano or Santo Domingo Street, the names given to what is now San Jacinto Street from the Pontoon Bridge to the

Cava until the 19th century. Commercial and industrial activities also took place in the neighbourhood [

30,

37].

There was also an expansion towards the area of the orchards, with new streets appearing from old paths, as well as the extension of Castilla Street beyond the Cava Vieja. Ultimately, this urban and social landscape of Triana, shaped by its ties to commerce, industry, the sea, and the routes to the Americas, reflected an interdependence of elements that contributed to its consolidation as a key neighbourhood in the history of early modern Seville.

4. Neighbours: Occupations and Backgrounds

As has been observed since the late medieval period, the population of Triana had been distinguished by its notable diversity of trades, a reflection of the economic and social structure of the neighbourhood. According to historians, Trianeros were engaged in activities linked to the sea, agriculture, and industry. Among the most widespread traders were sailors, who played a fundamental role in maritime traffic to the Indies, as well as builders and craftsmen, who were essential to producing elements necessary for navigation and daily life. In fact, Triana was a centre for the manufacture of items such as pottery, soap, gunpowder, and biscuit, products that were closely related to the expeditions and trade to America. In addition, the area surrounding the neighbourhood, rich in vegetable gardens, allowed agriculture to flourish, with the production of oil and wine, activities that were fundamental for the supply of the city and foreign trade [

40].

Along with these trades, the population of Triana was also made up of potters and other craftsmen who carried out work related to local production and trade. These trades were essential for the supply of basic products and the creation of utensils used in everyday life. In addition to these workers, Triana also housed servants, people dedicated to various domestic and support tasks, as well as professionals from different fields, such as doctors, apothecaries, and clergymen [

19]. The latter constituted an important part of the community, as they played significant roles in both the religious life and public health of the neighbourhood (

Figure 11).

An analysis of the documents of the surveys studied, which describe the properties and the conditions of the tenants, confirmed the variety of professions in the neighbourhood. In these texts, the occupation or social status of residents is often mentioned, allowing us to see a wide range of trades, from the humblest to the most prestigious. Among the tenants recorded are potters, labourers, sailors, and merchants, highlighting the economic versatility and the importance of manual and commercial work in the development of the neighbourhood. Married couples, widows, and a considerable number of married women, who were an active part of the community, also stand out. It is interesting to note the presence of Portuguese among the residents, which is consistent with the research of Quiles García et al. [

40], who underlined the significant Portuguese influence in Triana during the 16th century, especially in the maritime sphere.

The surveys also mention other professions that formed part of everyday life in Triana. Among them, the following trades are documented:

atahonero (flour mill worker), apothecary, ship captain, clergyman, doctor, farrier, ship master, pilot, merchant, and oil merchant, which once again shows the diversity of economic activities and the social plurality that existed in the neighbourhood. This professional diversity and the presence of people of different origins and social status constitute one of the most defining characteristics of Triana currently, reflecting its complexity as a meeting place for diverse social, ethnic, and economic groups (

Figure 12).

This panorama of diversity in the social composition of Triana highlights how the neighbourhood was not only a hub of economic activity, but also a space where diverse cultures and social groups coexisted. The coexistence of sailors, artisans, merchants, and workers of different trades, together with the influence of foreign populations, contributed to giving Triana its unique character within 16th-century Seville. This complex social structure allowed the neighbourhood to become a vibrant centre of production, trade, and culture, comprising a fundamental pillar of the city in the context of the economic boom linked to trade with the Indies.

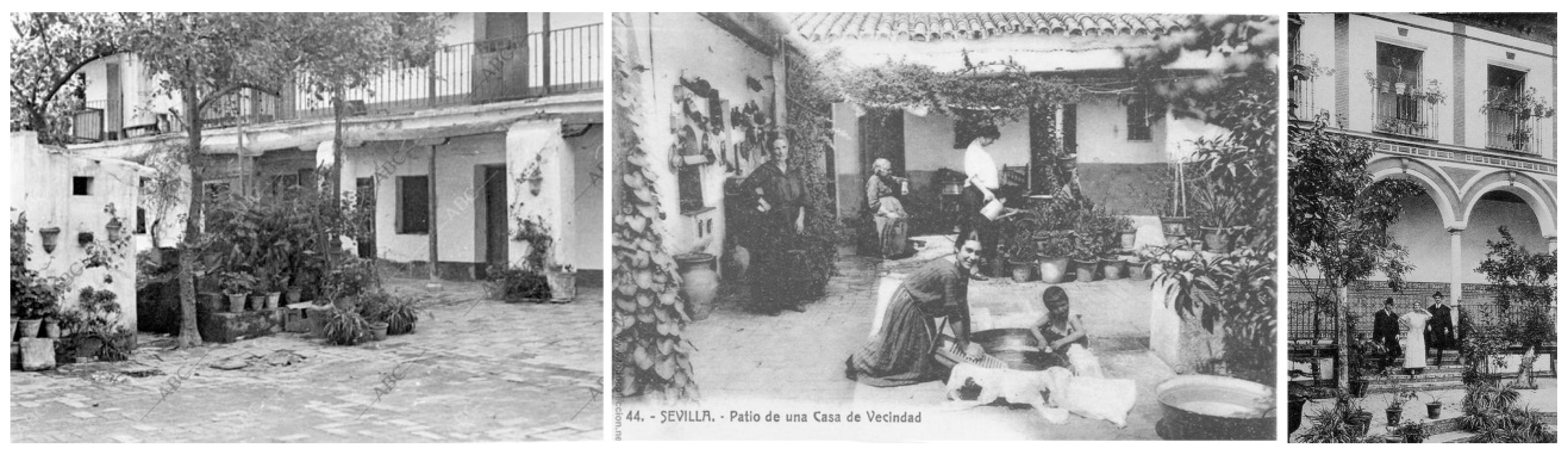

5. The Houses of Triana: Structure, Uses, and Distribution

Study of the dwellings of Triana, based on 44 analysed surveys, showed a notable variety in the types of constructions that predominated in this Sevillian neighbourhood. Most of the buildings were residential in character, although some other uses were documented, such as a corral that served as an orchard, a

corral de vecinos, and a shop. To better understand these spaces, we integrated data from other publications and chronicles that show tenement houses and

corrales de vecinos as the most common architectural typologies in Triana. These corrals and dwellings were not only residential, but also an integral part of a way of life that, due to their proximity to the city, was linked to commercial and service activities. In addition, the presence of inns suggests that Triana, being a neighbourhood outside the city walls and at the confluence of several roads, was a place of transit and rest, which favoured the formation of this type of establishment (

Figure 13).

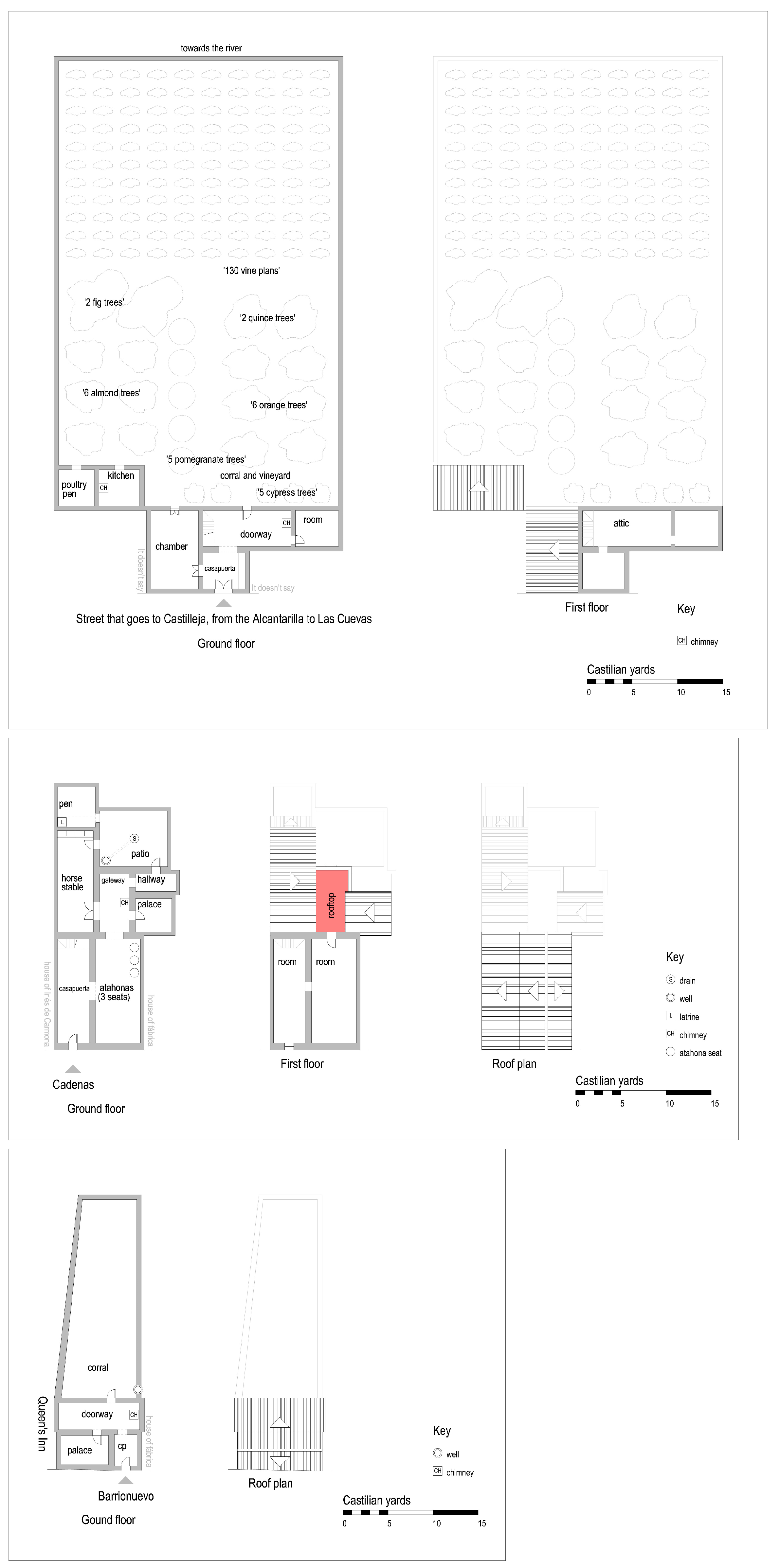

Our analysis of the Triana dwellings was based on 33 literary and 11 graphic surveys, which offer a detailed view of the surface area and distribution of the houses (

Figure 14). The literary surveys use Castilian yards (0.8359 m) to measure the width and length of the spaces, allowing the surface area of each room on the ground floor to be calculated. Once these measurements had been obtained, the occupied area of the plots was estimated by adding 10% to the total surface area of the dwellings to provide a more accurate approximation. The graphic surveys also provided a visual scale, which allowed the exact conversion of the measurements to square metres using a CAD programme (AutoCAD 2026).

Considering the aims of this research, several features of the survey texts and drawings can be identified. These documents serve as valuable sources for graphic representation due to their descriptive richness; they provide relevant data for urban studies by offering information on streets, neighbourhoods, and specific locations; they allow for the analysis of building uses, often including detailed descriptions; and they also contribute to the enrichment of technical and architectural vocabulary.

Architectural Drawing and Analysis

Over the course of our research, we developed a method aimed at incorporating a historical–archaeological perspective into the study of architecture. This approach relied not only on the analysis of abundant written sources and the more limited graphic documentation available, but also (when accessible) on the study of material and archaeological evidence. From an architectural standpoint, historical and archaeological knowledge has always been considered essential to fully understand and contextualise built forms.

Applying this method, 18 of the 19 dwellings analysed were graphically documented. These graphic surveys made it possible to delve into the study of domestic typologies in the Triana neighbourhood during the 16th and 17th centuries.

The procedure used to represent these buildings was based on the formulation of hypotheses regarding their floor plans, elevations, sections, and volumes. This hypothetical reconstruction provided a better understanding and allowed us to undertake an architectural analysis of the structures through a process that could be defined as a ‘translation from the literary and graphic into the digital’.

The work was carried out in several phases. The first stage involved locating, selecting, and then transcribing the documentary sources that would form the basis of the study. Once the archival work was completed, the second stage consisted of inputting the data into digital software to allow for further analysis, graphic reconstruction, and the cataloguing of the dwellings.

More specifically, the methodological process of digitising and analysing the constructions described in the surveys included the following steps:

Search, identification, and selection of the surveys and other documentary sources relevant to the study of Triana’s dwellings.

Study and classification of these sources to determine their reliability and usefulness.

Transcription of the survey texts in detail.

Digital processing of the data, entering the information into specialised software to organise the general data and select only what was necessary for understanding the architecture, construction, and formulation of drawing hypotheses.

Digital drawing of the buildings based on the survey descriptions.

Architectural and graphic analysis of the resulting representations, including both plan and volumetric aspects.

After the analysis, conclusions were drawn that covered the most frequent volumes and the relationship of the buildings with the street, such as the distributions, the uses of the spaces and their surfaces, as well as the most recurrent types of construction and the installations inside them.

Our analysis of the data from these surveys revealed that the average surface area of housing plots in Triana was around 200 square metres, which is higher than the average for Seville, which was approximately 160 square metres [

37]. This suggests that, compared to other areas of the city, Triana offered more spacious dwellings, which is consistent with the demand and commercial character of the neighbourhood.

In terms of the number of floors, most of the houses in Triana were not very tall. Single-floor dwellings predominated, although some exceptions were documented in the areas near the Altozano or Ancha Streets, which were areas with greater commercial activity. Some dwellings of greater surface area and construction quality were also found, which had more than one floor. In all cases, with one exception, the dwellings had a courtyard or a corral, or even both. These open-air spaces were essential for Triana dwellings and represented a characteristic element of the architecture of the neighbourhood.

Among the most common elements in Triana dwellings were casapuerta (vestibule), doorways, kitchens, and courtyards. Compared to the Seville average, Triana had a greater number of doorways, suggesting that the dwellings had multiple passageways that could have other uses. A kitchen, on the other hand, was present in almost 40% of Triana dwellings, compared to 25% in the rest of the city, which could show a difference in the habits and needs of the neighbourhood’s population. In many cases, the houses that did not have a proper kitchen had a space in the casapuerta, the doorway or the courtyard, where a fireplace was situated, or a cooker was installed for the preparation of food.

The living spaces in Triana’s houses were the so-called ‘palaces’, or living and sleeping quarters. The average number of these spaces was two per dwelling, which coincided with the general pattern in the city. However, given that many of the houses did not have

soberados (extra spaces on the upper floor), it is possible that the Triana dwellings had a smaller area devoted to rooms compared to the rest of Seville. It is important to note, however, that the courtyards and corrals were fundamental elements in the structure of Triana’s dwellings. In fact, corrals, with larger surfaces than courtyards were more common than in other areas of the city [

42] (

Figure 15).

In terms of facilities, dwellings in Triana did not always have a well, unlike in other parts of Seville, where this resource was more common. Only 70% of the dwellings analysed had one, which could be due to the proximity to the Guadalquivir River or to an alternative supply system not yet detailed in the documents. For water drainage, some dwellings were equipped with drains, and for sanitation, latrines were used.

To better illustrate the diversity of typologies and uses, three representative dwellings were selected: a house with a large orchard and vineyards, a house with three

atahonas (stone mill seats), and the house of a widow (a cook in a nearby inn). This variety of uses and configurations proves how, in Triana, the dwellings and especially the neighbourhood corrals not only fulfilled residential functions but also commercial and service functions. This trend continued even into the 20th century, when the

corrales de vecinos continued to share spaces with industrial and commercial activities [

43] (

Figure 16).