Zooarchaeology of the Pre-Bell Beaker Chalcolithic Period of Barrio del Castillo (Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid, Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

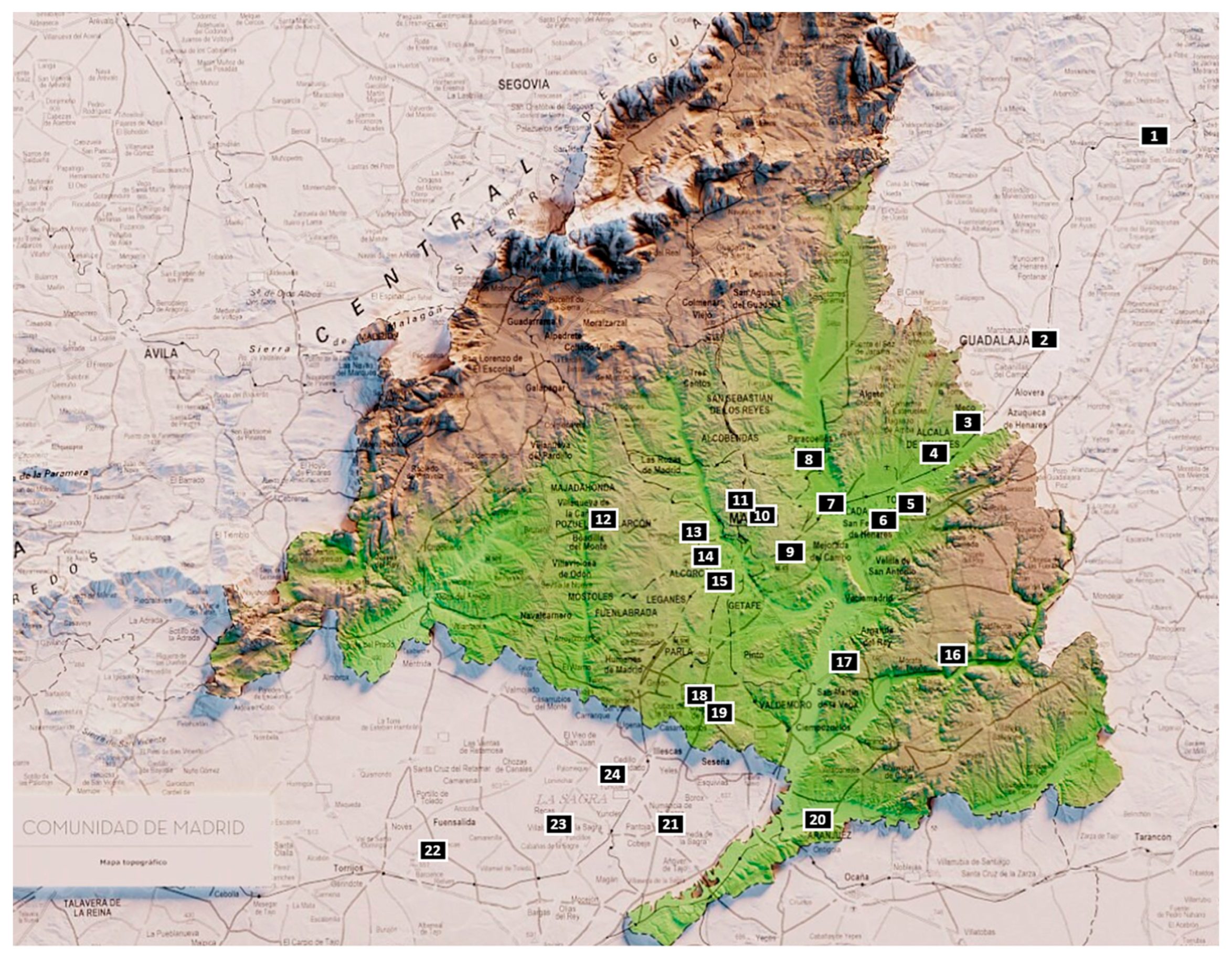

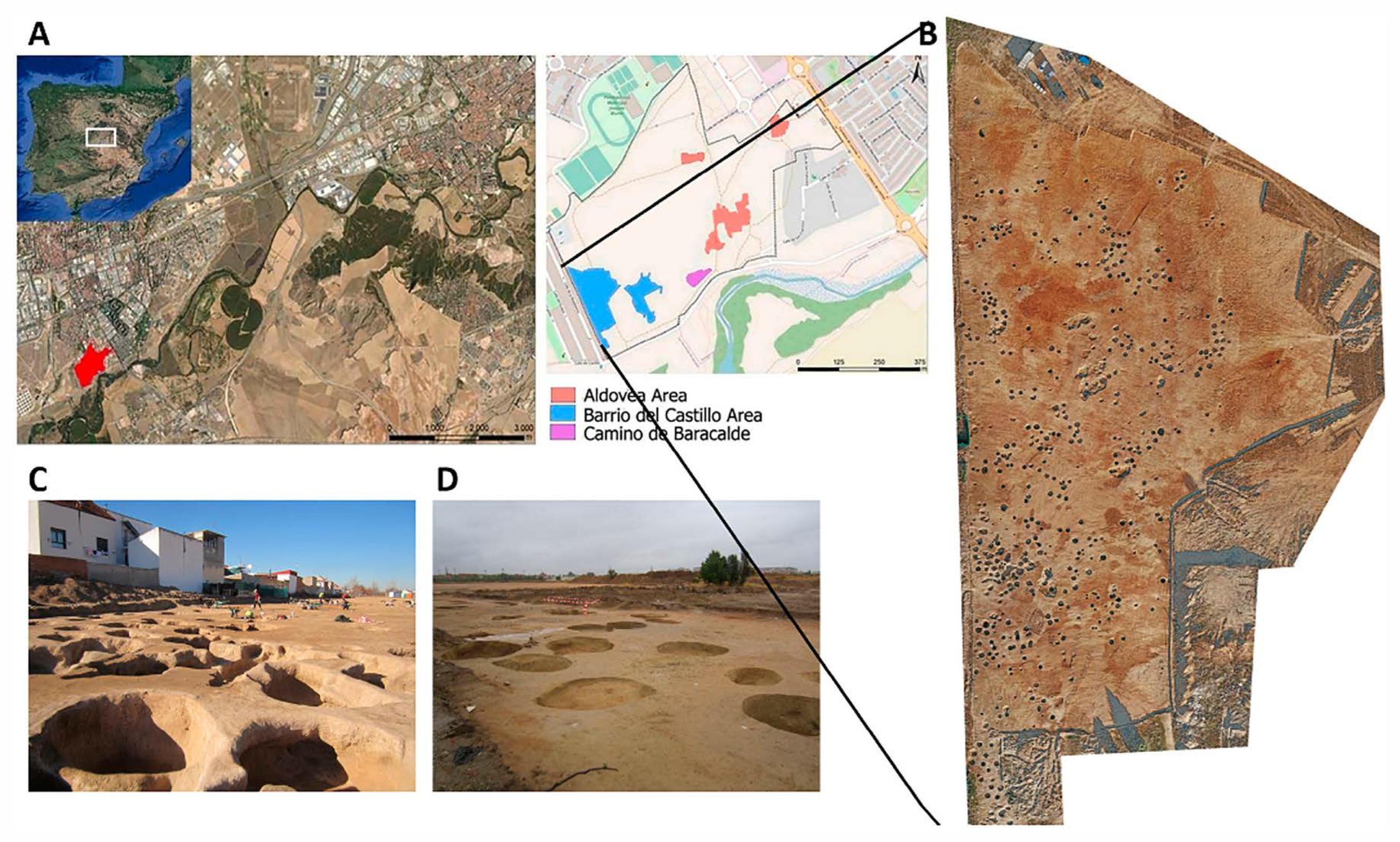

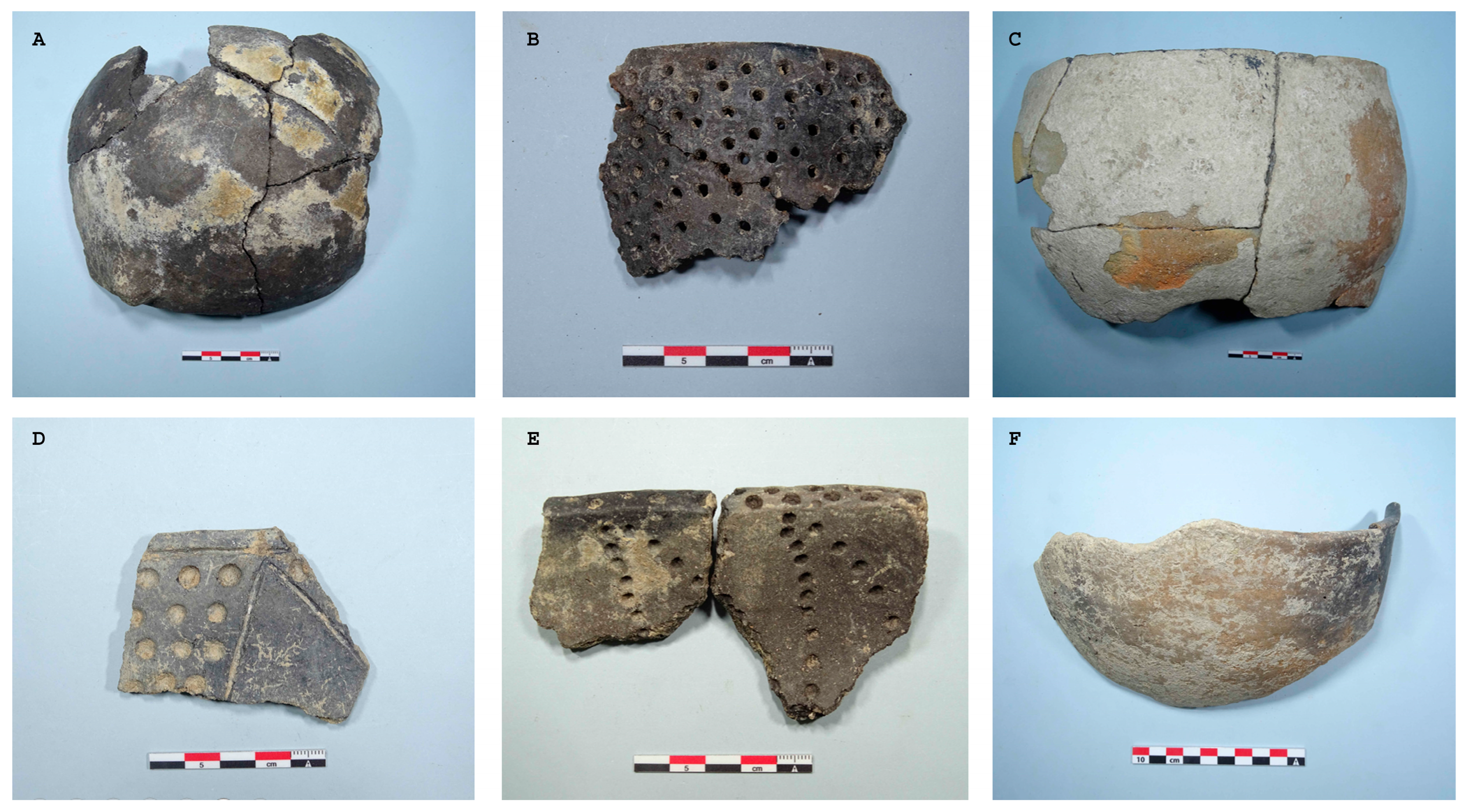

2. Barrio del Castillo

3. Materials and Methods

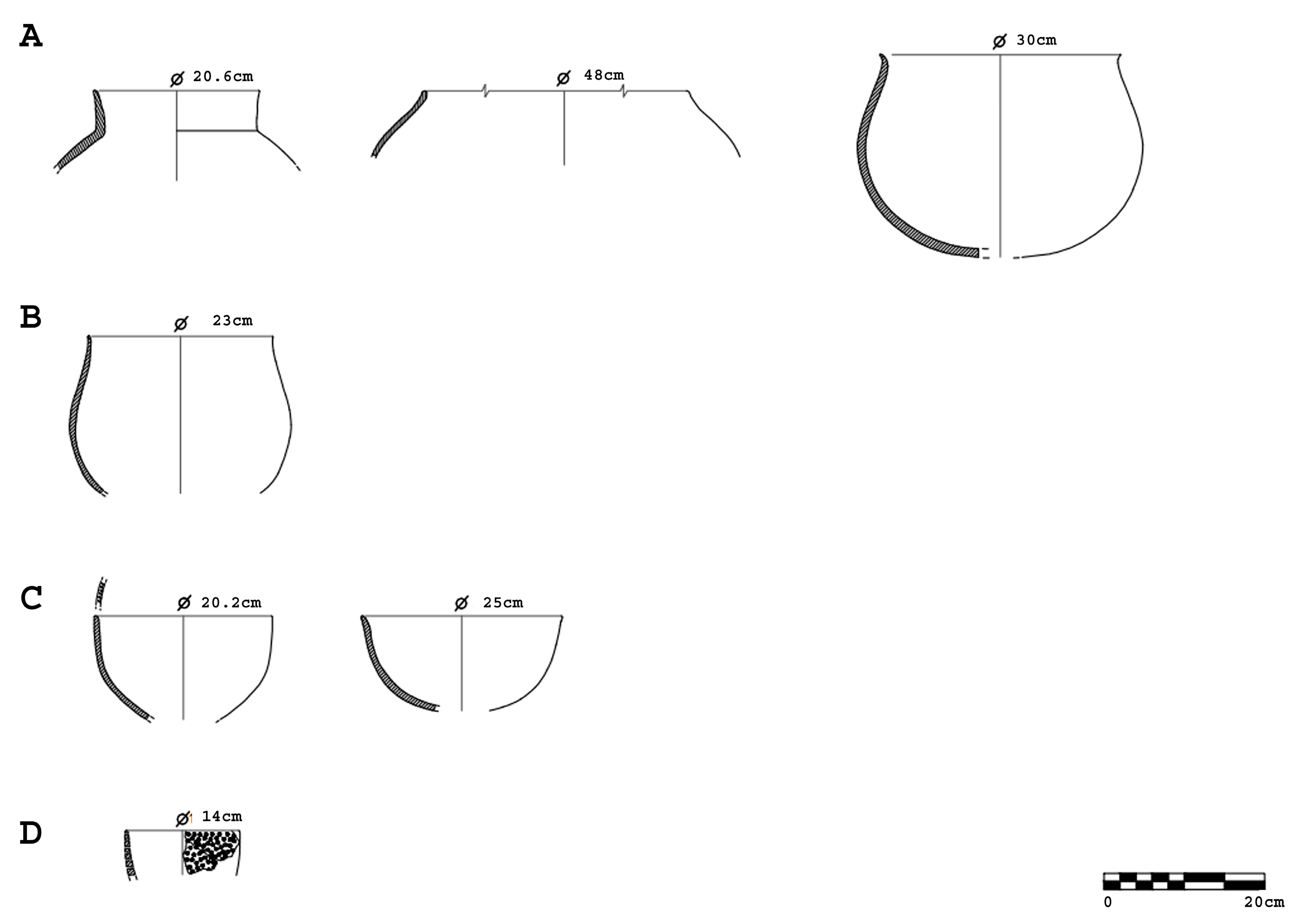

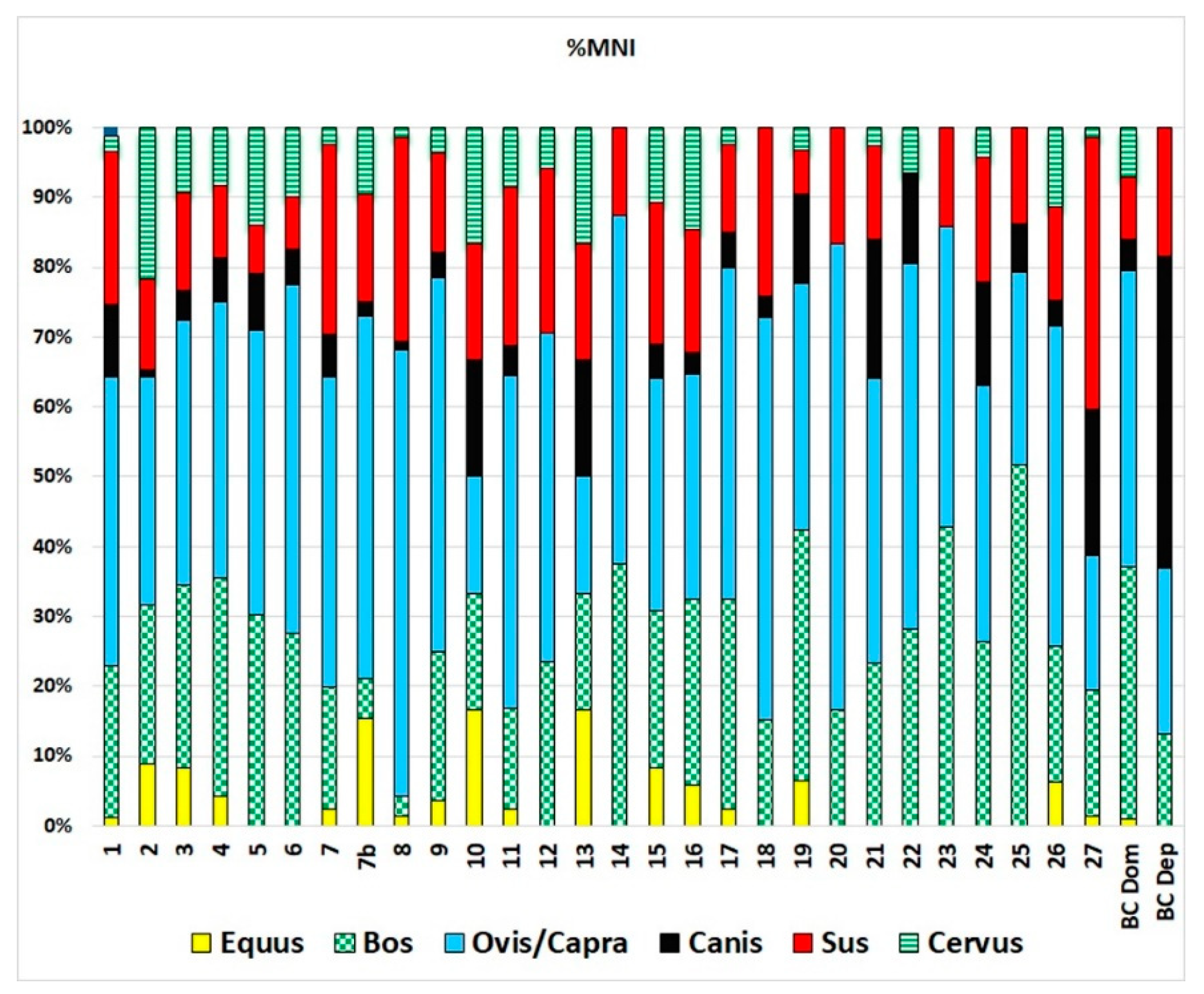

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Future Proposals and Final Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morales, A.; Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck, C. Arqueozoología del Calcolítico en Madrid. In El Horizonte Campaniforme de la región de Madrid en el Centenario de Ciempozuelos; Blasco, C., Ed.; Ensayo Crítico de Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 1994; pp. 227–247. [Google Scholar]

- Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck, C. Fauna in Living and Funerary Contexts of the 3rd Millennium BC in Central Iberia. In Key Resources and Sociocultural Developments in the Iberian Chalcolithic; Bartelheim, M., Bueno Ramirez, P., Kunst, M., Eds.; Academia: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Estaca-Gómez, V.; López, G.; Morín, J.; Yravedra, J. Estudio Zooarqueológico y Tafonómico del Yacimiento Calcolítico Las Zanjillas (Torrejón de Velasco, Madrid). Munibe Antropoligía-Arkeol. 2023, 74, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estaca Gómez, V.; de la Torre García, A.; Señoran Martín, J.M.; Martínez Granero, A.B.; Major González, M.; Yravedra Sainz de los Terreros, J. Aprovechamiento de recursos animales en el yacimiento calcolítico precampaniforme de Aldovea (Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid). Complutum 2023, 34, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck, C. La Arqueozoología, un elemento clave en la concepción espacial de Camino de las Yeseras. Los restos de mamíferos del ámbito doméstico y funerario. In Yacimientos Calcolíticos con Campaniforme de la región de Madrid. Nuevos Estudios; Blasco, C., Liesau, C., Ríos, P., Eds.; Patrimonio Arqueológico de Madrid, 6; Universidad Autónoma de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2011; pp. 167–170. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Pellicena, M.Á.; San José, V.; Sánchez, M.; Sánchez, M.; Lorente, M. Soto del Henares. Aproximación a un poblado de recintos. In Actas de las Cuartas Jornadas de Patrimonio Arqueológico de la Comunidad de Madrid; Jordana, N.B., Benito López, J.E., Eds.; Museo Arqueológico Regional: Alcalá de Henares, Spain, 2009; pp. 263–271. [Google Scholar]

- Valiente Malla, J. La Loma del Lomo III, Cogolludo Guadalajara; Patrimonio Historico; Arqueología: Castilla la Mancha, Spain, 2001; Volume 17, 304p. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz del Río, P. Campesinado y gestión pluriactiva del ecosistema: Un marco teórico para el análisis del III y el II milenios a.C. en la Meseta peninsular. Trab. Prehist. 1995, 54, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major-González, M.; Señorán Martín, J.M.; López-López, G.; Martínez Granero, A.B.; Izquierdo Zamora, A. Los yacimientos prehistóricos de Aldovea; Actas de la RAM: Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid; Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Estaca Gómez, V.; de la Torre, A.; Tardaguila-Giacomozzi, S.; Major González, M. Zooarchaeological study of Aldovea (Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid), a new Bronze Age archaeological site from the Iberian Peninsula inland. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2024, 57, 104616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez-Orta, R.; Rodríguez, L.; Major González, M.; Estaca-Gómez, V.; De Gaspar, I.; Feranec, R.S.; Carretero, J.M.; Arsuaga, J.L.; García, N. Dogs from the past: Exploring morphology in mandibles from Iberian archaeological sites using 3D geometric morphometrics. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2024, 57, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellido, A. Los campos de hoyos. In Inicios de la Economía Agrícola en la Submeseta Norte; Studia Archaeológica, 85; Universidad de Valladolid: Valladolid, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz del Río, P. La Formación del Paisaje Agrario: Madrid en el III y II Milenios BC; Arqueología, Paleontología Y Etnografía, 9; Comunidad de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2001; 397p, Available online: https://www.madrid.org/bvirtual/BVCM002085.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Díaz del Río, P. Recintos de fosos del III milenio ac en la meseta peninsular. Trab. Prehist. 2003, 60, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameda Cuenca-Romero, M.C.; Carmona Ballestero, E.; Pascual Blanco, S.; Martínez Díez, G.; Díez Pastor, C. El “campo de hoyos” calcolítico de Fuente Celada (Burgos): Datos preliminares y perspectivas. Complutum 2011, 22, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.M. Interpretación arqueológica de un “Campo de Hoyos” en Forfoleda (Salamanca). Zephyrus 2009, 46, 309–313. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, R. Anatomie Comparée des Mammifères Domestiques 1; Ostéologie-Paris Laboratoire d’Anatomie, Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire: Paris, France, 1986; 879p. [Google Scholar]

- Pales, L.; Lambert, C. Atlas Osteologique Pour Servir à l’Identification des Mamiferes du Quaternaire; Éditions du Centre national de la Recherche Scientifique: Paris, France, 1971; 177p. [Google Scholar]

- Prummel, W. Distinguishing Features en Postcranial SKELETAL elememnts of Cattle, Bos primigenius, Bos taurus and Red deer, Cervus elaphus; Schriften aus der Archäologisch-Zoologischen Arbeitsgruppe Schleswig-Kiel; Heft 12; Institut für Haustierkunde Neue Universität: Paris, France, 1988; pp. 5–52. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, E. Atlas of Animal Bones for Prehistorians, Archaeologist and Quaternary Geologist; Elsevier Publishing Company: Amsterdan, The Netherland; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1972; 156p. [Google Scholar]

- Hilson, S. Mammal Bones and Teeth: An Introductory Guide to Methods of Identification; London Institute of Archaeology: London, UK, 1992; 119p. [Google Scholar]

- Boesseneck, J. Osteological Differences between Sheep (Ovis aries Linné) and Goats (Capra hircus Linné). In Science in Archaeology; Praeger: New York, NY, USA, 1969; pp. 331–358. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, H. Osteologie Comparee des Petties Ruminants Eurasiatiques Sauvages et Domestiques (Genres Rupicapra, Ovis, Capra et Capreolus): Diagnose Differentialle du Squelette Apendiculaire. Ph.D. Thesis, Facultat de Ciencies, Universite de Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, S. Morphological distinction between the mandibular teeth of young sheep, Ovis and goats, Capra. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1985, 12, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prummel, W.; Frisch, H.J. A guide for the distinction of species, sex and body size in bones of sheep and goat. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1986, 13, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolett, B.V.; Chiu, M. Age Estimation of Prehistoric Pigs (Sus scrofa) by Molar Eruption and Attrition. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1994, 21, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Ripoll, M. Estudio de la secuencia del desgaste de los molares de Capra pyrenaica de los yacimientos prehistóricos. Arch. Prehist. Levantina 1988, 18, 83–128. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, S. Kill-off pattern in sheep and goats: The mandibles of Açvan Kale. Anatol. Stud. 1973, 23, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducos, P. L’Origine des Animaux Domestiques en Palestine. Publications de l’Institut de Pr´ehistoire de l’Universite´ de Bordeau/M´emoire, Volume 6; Delmas: Bordeaux, France, 1968; 191p. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A. The use of tooth wear as a guide to the age of domestic ungulates. In Ageing and Sexing Animal Bones from Archaeological Sites; Wilson, B., Grigson, C., Payne, S., Eds.; BAR International Series 109; BAR Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1982; pp. 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, T.P. Husbandry decisions: Age at death. In The Analysis of Urban Animal Bones Assemblages: A Hand Book for Archaeologists; O’Connor, T.P., Ed.; Council for British Archaeology: York, UK, 2003; pp. 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Yravedra, J. Tafonomía Aplicada a Zooarqueología; Aula Abierta: Madrid, Spain, 2006; 412p. [Google Scholar]

- Yravedra, J. Arqueozoología y Tafonomía del Yacimiento Calcolítico del Barranco del Herrero (San Martín de la Vega, Madrid). Estud. Prehist. Arqueol. Madrileñas 2007, 14–16, 427–440. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-García, M.; y Cantalapiedra, V. Sobre el aprovechamiento de recursos de origen animal en la región de Madrid durante el III milenio cal. AC: La fauna de los contextos calcolíticos del Sector 3 de Las Cabeceras (Pozuelo de Alarcón, Madrid). Boletín Semin. Estud. Arte Arqueol. (BSAA) 2021, LXXXV–LXXXVI, 177–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estaca Gómez, V.; Yravedra, J. Informe Zooarqueológico de Humanjos; Parla: Comunidad de Madrid, Spain, 2015; (Unpublished). [Google Scholar]

- García Somoza, P. Zooarqueología de los sectores 0 y Vía Pecuaria del yacimiento Ampliación Aguas Vivas. In El yacimiento arqueológico de Aguas Vivas. Prehistoria Reciente en el Valle del Río Henares (Guadalajara); Cantalapiedra-Jiménez, V., Ísmodes-Ezcurra, A., Eds.; La Ergástula Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 133–161. [Google Scholar]

- Yravedra, J. Zooarqueología de los sectores 1 y 2 del Yacimiento Ampliación Aguas Vivas. In El yacimiento arqueológico de Aguas Vivas. Prehistoria Reciente en el Valle del Río Henares (Guadalajara); Cantalapiedra-Jiménez, V., Ísmodes-Ezcurra, A., Eds.; La Ergástula Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Priego, Mª.C.; y Quero, S. El Ventorro, un Poblado Prehistórico de los Albores de la Metalurgia; Estudios de Prehistoria y Arqueología Madrileñas: Madrid, Spain, 1992; Volume 8, 381p. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, A.; Villegas, C. La fauna de mamíferos del yacimiento de “El Ventorro”. Pecado-tesis osteológica de la campaña de 1981. Estud. Prehist. Arqueol. Madrileñas 1994, 9, 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck, C. Depósitos con ofrendas de animales en yacimientos Cogotas I: Antecedentes y características. In Cogotas I, Una cultura de la Edad del Bronce en la Península Ibérica; Rodríguez Marcos, J.A., Fernández Manzano, J., Eds.; Ediciones Universidad de Valladolid: Valladolid, Spain, 2012; pp. 219–257. [Google Scholar]

- Cerdeño, M.E.; Herráez, E. Estudio de la fauna del Yacimiento del Espinillo (Villaverde, Madrid). In El Espinillo: Un Yacimiento Calcolítico y de la edad del Bronce en las Terrazas del Manzanares; Baquedano, E., de la Torre, M.P., Marín, A.B., Eds.; Arqueología, Paleontología y Etnografía: Madrid, Spain, 2000; Volume 8, pp. 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Baquedano, M.L.; Blanco, F.; Alonso, P.; Álvarez, D. El Espinillo: Un Yacimiento Calcolítico y de la Edad del Bronce en las Terrazas del Manzanares; Arqueología, Paleontología y Etnografia: Madrid, Spain, 2000; Volume 8, 164p. [Google Scholar]

- Estaca-Gómez, V. La Zooarqueología Durante la Edad del Hierro en el Valle Medio del Tajo; AUDEMA; UCM: Madrid, Spain, 2017; 328p. [Google Scholar]

- Estaca-Gómez, V. Prácticas socioeconómicas de la fauna doméstica de la Edad del Hierro en el Valle Medio del Tajo. Complutum 2018, 29, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estaca-Gómez, V.; Linares-Matás, G.J. Husbandry practices among Iron Age communities in the centre of the Iberian Peninsula. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 5009–5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cámara, J.A.; Lizcano, R. Ritual y sedentarización en el yacimiento del Polideportivo de Martos (Jaén). Actas del I Congrés del Neolitic a la Península Ibérica, Gavá-Bellaterra, 1995. Rubricantum 1996, 1, 313–322. [Google Scholar]

- Liesau, C.; Vega, J.; Daza, A.; Ríos, P.; Menduiña, R.; Blasco, C. Manifestaciones simbólicas en el acceso Noreste del Recinto 4 de Foso en Camino de las Yeseras (San Fernando de Henares, Madrid). Saldvie 2014, 13/14, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez-Romero, J.E. Sobre los depósitos estructurados de animales en yacimientos de fosos del Sur de la Península Ibérica. Animais na Pré-hisória e Arqueología da Península Ibérica. In Proceedings of the Actas do IV Congreso de Arqueología Peninsular, Braga, Portugal, 14–19 September 2004; pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Liesau, C.; Blasco, C.; Ríos, P.; Vega, J.; Menduiña, R.; Blanco, J.F.; Baena, J.; Herrera, T.; Petri, A.; Gómez, J.L. Un espacio compartido por vivos y muertos: El poblado calcolítico de fosos de Camino de las Yeseras (San Fernando de Henares, Madrid). Complutum 2008, 18, 97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Pellicena, M.Á.; Pérez-Romero, A.; Gómez-Felipe, A.; Romero-Ruiz, M.; Blázquez-Orta, R.; Andreu-Alarcón, S.; Benítez de Lugo Enrich, L. Animals for the Deceased: Zooarchaeological Analysis of the Bronze Age in the Castillejo del Bonete Site (Terrinches, Ciudad Real, Spain). Animals 2025, 15, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estaca Gómez, V.; Cruz-Alcázar, R.; Tardaguila-Giacomozzi, S.; y Yravedra, J. New Evidence for the Bronze Age Zooarchaeology in the Inland Area of the Iberian Peninsula through the Analysis of Pista de Motos (Villaverde Bajo, Madrid). Animals 2024, 14, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Navarrete, M.I. El yacimiento de La Esgaravita (Alcalá de Henares, Madrid) y la cuestión de los llamados fondos de cabaña del Valle del Manzanares. Trab. Prehist. 1979, 36, 83–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ríos, P.; Daza, A.; Ortiz, I.; de Chorro, M.Á.; y Liesau, C. La Cabaña ‘E’ del yacimiento de Camino de las Yeseras. Nuevos datos sobre el espacio doméstico en un Poblado de Hoyos. Cuad. Prehist. Arqueol. 2016, 2, 73–105. [Google Scholar]

- Molero Gutiérrez, G.; Brea López, P.; y Bustos Pretel, V. Estudio faunístico de la cueva de Juan Barbero (Tielmes, Madrid). Trab. Prehist. 1984, 41, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Liesau von Lettow-Vorbeck, C. Análisis faunístico de los yacimientos de “Huerta de los Cabreros”, “Cantera de la Flamenca” y “Puente Largo del Jarama” (Aranjuez, Madrid). In El Poblamiento desde el Neolítico Final a la Primera Edad del Hierro en la Cuenca Media del río Tajo; Muñoz, K., Ed.; Univesidad Complutense de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 1998; pp. 1418–1444. [Google Scholar]

- Priego Fernández, C.M. El yacimiento de Angosta de los Mancebos. Nueva contribución al conocimiento de la Edad del Bronce madrileño. Estud. Prehist. Arqueol. Madrileños 1994, 9, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

| Domestic Contexts | Ritual Deposits | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NISP | % All NISP | % Determinate NISP | MNI | % MNI | NISP | % All Specimens | % Determinate NISP | MNI | % MNI | |

| Bos taurus | 618 | 15.5 | 41.2 | 81 | 35.1 | 280 | 9.4 | 12.7 | 5 | 12.5 |

| Equus ferus | 2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.9 | |||||

| Ovis/Capra | 629 | 15.8 | 41.9 | 95 | 41.1 | 81 | 2.7 | 3.7 | 9 | 22.5 |

| Ovis aries | 15 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 4 | 1.7 | 12 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1 | 2.5 |

| Capra hircus | 13 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 3 | 1.3 | |||||

| Canis familiaris | 118 | 3.0 | 7.9 | 10 | 4.3 | 1649 | 55.1 | 75.0 | 18 | 45 |

| Sus domesticus | 54 | 1.4 | 3.6 | 20 | 8.7 | 178 | 5.9 | 8.1 | 7 | 17.5 |

| Cervus elaphus | 51 | 1.3 | 3.4 | 16 | 6.9 | |||||

| Large | 409 | 10.3 | 48 | 1.6 | ||||||

| Large/medium | 16 | 0.4 | ||||||||

| Medium | 2 | 0.1 | ||||||||

| Small | 145 | 3.6 | 734 | 24.5 | ||||||

| Indeterminate | 1906 | 47.9 | 10 | 0.3 | ||||||

| Total | 3978 | 100.0 | 231 | 100.0 | 2992 | 100.0 | 40 | 100.0 | ||

| SU with Ritual Deposit | Bos taurus | Canis familiaris | Ovis/ Capra | Ovis aries | Sus domesticus | Large | Small | Indet. | Additional Relevant Information of the SU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | ||

| 10,893 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 33 | Quartzite and ceramic bed, over which two human burials were placed. | ||||

| 11,233 | 39 | 12 | 1 | 89 | Partial deposit with appendicular bones of a female senile sheep, associated with ceramics and lithics. | ||||

| 6834 | 188 | Deposit of complete adult female dog over a bed of quartzite. Placed on its left side with SE/NW orientation. | |||||||

| 6836 | 174 | Deposit of infant dog (5–7 months old) placed under a bed of quartzite. Placed on its right side with W/E orientation. | |||||||

| 6976A | 206 | Deposit with at least seven complete dogs in anatomic connection and another three partial dogs. Additionally, two pigs, one infant (14 months old), and another partial infant individual in 6976J (5–7 months old) The dogs are as follows: 6976A complete infant (6–7 months old) 6976 B partial, not articulated (4–6 weeks old) 6976F–G complete infant (4–5 months old) 6976H complete female adult 6976I partial articulated leg 6976J partial articulated legs (10 months old) 6976L complete juvenile (12 months old) 6976N complete infant (3–5 months old) 69760P complete infant (6 months old) 69760Q complete infant | |||||||

| 6976B | 17 | 3 | 58 | ||||||

| 6976C | 5 | 2 | 4 | 234 | |||||

| 6976F | 150 | ||||||||

| 6976G | 80 | 11 | |||||||

| 6976H | 226 | ||||||||

| 6976I | 10 | 20 | 13 | 2 | 115 | 1 | |||

| 6976J | 37 | 112 | 172 | ||||||

| 6976L | 240 | ||||||||

| 6976N | 11 | ||||||||

| 6976O | 107 | ||||||||

| 6976P | 31 | 1 | |||||||

| 6976Q | 139 | ||||||||

| 6976R | 2 | ||||||||

| 7551 | 183 | 1 | 2 | Complete adult female Bos | |||||

| 8231 | 9 | 16 | 21 | 53 | 12 | 44 | Pig cranium | ||

| 8261 | 76 | 2 | 8 | 9 | Partial skeleton of Bos | ||||

| Total | 280 | 1649 | 81 | 12 | 178 | 48 | 734 | 10 |

| Domestic Context | Deposit SU | Intentional Deposit | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNI | Adult | Infant | %Adult | MNI | Adult | Juv–Infant | %Adult | ||

| Bos taurus | 81 | 75 | 6 | 92.6 | 5 | 5 | 100.0 | 2: 2 Adults | |

| Equus ferus | 2 | 2 | 100 | ||||||

| Ovis/Capra | 95 | 83 | 12 | 87.4 | 9 | 5 | 1–3 | 55.5 | |

| Ovis aries | 4 | 4 | 100.0 | 1 | 1 | 100.0 | 1: 1 Adult | ||

| Capra hircus | 3 | 2 | 1 | 66.7 | |||||

| Canis familiaris | 10 | 8 | 2 | 80.0 | 17 | 6 | 1–11 | 35.3 | 10: 3 Adults/7 Infs |

| Sus domesticus | 20 | 20 | 2 | 100.0 | 7 | 3 | 0–4 | 42.8 | 3: 1 Adult/2 Infs |

| Cervus elaphus | 16 | 16 | 0 | 100.0 | |||||

| Total | 231 | 208 | 23 | 39 | 20 | 2–18 | |||

| Bos | Cervus | Equus | Total O/C | Sus | Canis | Large | Medium | Small | Indet. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NISP | % | NISP | NISP | NISP | % | NISP | NISP | % | NISP | NISP | NISP | NISP | |

| Horn/antler | 58 | 9.4 | 8 | 2 | 0.3 | 43 | |||||||

| Cranium | 60 | 9.7 | 5 | 117 | 17.8 | 4 | 3.4 | 2 | 20 | ||||

| Mandible | 102 | 16.5 | 32 | 4.9 | 4 | 8 | 6.8 | 2 | |||||

| Maxillary | 15 | 2.4 | 6 | 0.9 | 3 | 1 | 0.8 | 1 | |||||

| Tooth | 130 | 21.0 | 148 | 22.5 | 39 | 19 | 16.1 | 10 | 33 | ||||

| Vertebrae | 27 | 4.4 | 5 | 7 | 1.1 | 11 | 9.3 | 19 | 1 | ||||

| Rib | 67 | 10.8 | 9 | 68 | 10.4 | 5 | 20 | 16.9 | 3 | 14 | |||

| Scapula | 58 | 9.4 | 5 | 91 | 13.9 | 4 | 3 | 2.5 | 8 | 2 | |||

| Humerus | 27 | 4.4 | 3 | 26 | 4.0 | 2 | 4 | 3.4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| Radius | 9 | 1.5 | 2 | 25 | 3.8 | 3 | 2.5 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Radio-Ulna | 3 | 0.5 | 11 | 1.7 | 3 | 2.5 | |||||||

| Ulna | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.3 | 6 | 5.1 | 1 | ||||||

| Carpal | 4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1 | |||||||||

| Metacarpal | 5 | 0.8 | 6 | 0.9 | 4 | 3.4 | 1 | ||||||

| Pelvis | 13 | 2.1 | 2 | 10 | 1.5 | 4 | 3.4 | 14 | 3 | ||||

| Femur | 6 | 1.0 | 1 | 13 | 2.0 | 3 | 2.5 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Tibia | 5 | 0.8 | 5 | 1 | 22 | 3.3 | 5 | 4.2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Fibula | 1 | 0.8 | |||||||||||

| Tarsal | 4 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.5 | 2 | 1.7 | |||||||

| Metatarsal | 10 | 1.6 | 4 | 1 | 32 | 4.9 | |||||||

| Metapodial | 8 | 1.3 | 2 | 25 | 3.8 | 1 | 14 | 11.9 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Phalanges | 10 | 1.6 | 7 | 1.1 | 1 | 3 | 2.5 | ||||||

| Indet. | 353 | 1 | 107 | 1801 | |||||||||

| Total | 618 | 100.0 | 51 | 2 | 657 | 100.0 | 59 | 118 | 100.0 | 409 | 2 | 145 | 1906 |

| Cranial | 365 | 59.1 | 13 | 305 | 46.4 | 46 | 32 | 27.1 | 1 | 14 | 96 | ||

| Axial | 165 | 26.7 | 21 | 176 | 26.8 | 9 | 38 | 32.2 | 44 | 14 | 6 | ||

| Up. Apend. | 33 | 5.3 | 4 | 39 | 5.9 | 2 | 7 | 5.9 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |

| Inter. Apend. | 18 | 2.9 | 7 | 1 | 60 | 9.1 | 18 | 15.3 | 5 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Low. Apend. | 37 | 6.0 | 6 | 1 | 77 | 11.7 | 2 | 23 | 19.5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Forelimb | 103 | 73.0 | 10 | 0 | 165 | 67.3 | 6 | 23 | 65.7 | 12 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Hindlimb | 38 | 27.0 | 12 | 2 | 80 | 32.7 | 0 | 15 | 42.9 | 18 | 0 | 5 | 3 |

| SU: | 11233 | 6834 | 6836 | 6976A | 6976F-G | 6976H | 6976J | 6976J | 6976N | 6976O | 7551 | 8261 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxon | Ovis | Canis | Canis | Canis | Canis | Canis | Canis | Sus | Canis | Canis | Bos | Bos |

| MNE | MNE | MNE | MNE | MNE | MNE | MNE | MNE | MNE | MNE | MNE | MNE | |

| Horn/Antler | 2 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||

| Cranium | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Mandible | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Maxillary | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Tooth | 26 | 16 | 16 | 14 | 7 | 14 | 4 | 21 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 6 |

| Vertebra | 25 | 30 | 20 | 27 | 30 | 27 | 3 | |||||

| Rib | 7 | 48 | 24 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 20 | 2 | |||

| Scapula | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Humerus | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| Radius | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Ulna | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Carpal | 9 | 12 | ||||||||||

| Metacarpal | 2 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 7 | |||||

| Pelvis | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Femur | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Patella | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||

| Tibia | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Fibula | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Metatarsal | 2 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 2 | ||||

| Tarsal | 3 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 | |||||

| Phalanges | 2 | 9 | 6 | 28 | 26 | 3 | 10 | 29 | 1 | 6 | 2 | |

| Total | 50 | 86 | 80 | 101 | 109 | 102 | 32 | 53 | 141 | 74 | 47 | 29 |

| %MNE | %MNE | %MNE | %MNE | %MNE | %MNE | %MNE | %MNE | %MNE | %MNE | %MNE | %MNE | |

| Cranial | 64.0 | 22.1 | 23.8 | 18.8 | 9.2 | 14.7 | 15.6 | 47.2 | 7.1 | 9.5 | 34.0 | 34.5 |

| Axial | 14.0 | 55.8 | 61.3 | 57.4 | 45.9 | 26.5 | 12.5 | 1.9 | 41.8 | 77.0 | 48.9 | 20.7 |

| Up. Apend. | 4.0 | 4.7 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 2.1 | 6.9 |

| Inter. Apend. | 6.0 | 7.0 | 7.5 | 6.9 | 5.5 | 6.9 | 18.8 | 7.5 | 4.3 | 6.8 | 2.1 | 6.9 |

| Low. Apend. | 12.0 | 10.5 | 7.5 | 12.9 | 35.8 | 48.0 | 53.1 | 39.6 | 44.7 | 2.7 | 12.8 | 31.0 |

| Forelimb | 55.6 | 60.0 | 66.7 | 42.3 | 36.0 | 55.9 | 45.8 | 44.4 | 54.3 | 53.8 | 50.0 | 13.3 |

| Hindlimb | 44.4 | 40.0 | 33.3 | 57.7 | 64.0 | 44.1 | 54.2 | 55.6 | 45.7 | 46.2 | 50.0 | 86.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Estaca-Gómez, V.; Major-González, M.; Cañas-Martínez, J.; Yravedra, J. Zooarchaeology of the Pre-Bell Beaker Chalcolithic Period of Barrio del Castillo (Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid, Spain). Heritage 2025, 8, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8050181

Estaca-Gómez V, Major-González M, Cañas-Martínez J, Yravedra J. Zooarchaeology of the Pre-Bell Beaker Chalcolithic Period of Barrio del Castillo (Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid, Spain). Heritage. 2025; 8(5):181. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8050181

Chicago/Turabian StyleEstaca-Gómez, Verónica, Mónica Major-González, Jorge Cañas-Martínez, and José Yravedra. 2025. "Zooarchaeology of the Pre-Bell Beaker Chalcolithic Period of Barrio del Castillo (Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid, Spain)" Heritage 8, no. 5: 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8050181

APA StyleEstaca-Gómez, V., Major-González, M., Cañas-Martínez, J., & Yravedra, J. (2025). Zooarchaeology of the Pre-Bell Beaker Chalcolithic Period of Barrio del Castillo (Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid, Spain). Heritage, 8(5), 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8050181