Abstract

In July 2024, the “Investigating the Archaeology of Death in Pompeii Research Project” carried out a scientific and methodical excavation of the areas outside two of the gates to the city of Pompeii. One of them is the funerary area of Porta Nola (next to the tomb of Obellio Firmo) and the other is outside Porta Sarno area (east of the tomb of Marcus Venerius Secundius). The investigated funerary area to the east of Porta Sarno corresponds with the area excavated in 1998 for the construction of the double Circumvesuviana rails. The 1998 excavations recorded the presence of more than 50 cremation burial sites, marked by stelae (columelle) and a monument with an arch, which are delineated by a boundary wall. The tombs were initially dated to the Late Republican period. In order to carry out comprehensive studies of the funerary area uncovered in 1998, a four metre by four metre trench was stratigraphically excavated. This investigation allowed mapping of the area and the carrying out of archaeological analysis and bioarchaeological studies in order to answer the questions that guided our archaeological research, such as whether the funerary area was abandoned and, if so, when? What was the chronological succession, monumentality, and prestige of this funerary space? Was it a single family and private funerary enclosure, or was it an open public space? How were this funerary area and the spaces destined to preserve the memory of the deceased managed? How were the funerary and mortuary rituals and gestures articulated and what did they consist of? Our methodical excavation discovered a monumental tomb which allows us to answer many of the questions raised by our research. This extraordinary monument consists of a wide wall with several niches containing the cremated remains of the deceased built into its structure and which is crowned by a relief of a young couple. The symbolism of the carved accessories of the wife may identify her as a priestess of Ceres. Additionally, the quality of the carving in the sculptures and their archaic characteristics suggest a Republic period dating, which is uncommon in southern Italy.

1. Introduction

Our research project on the funeral archaeology in Pompeii is mainly focused on the study of the sepulchral spaces located east of the city, in particular those within the area of Porta Sarno. This funerary area, one of the oldest in Pompeii, was active from the Samnite period (IV–II century BC) to the years preceding the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius (79 AD). Recent discoveries in this area further our knowledge of the history of Pompeii. In particular, our knowledge of its religion, of the management and organisation of its grave places, and of the rituals and ideology of death in Pompeii has grown with the study of the tombs in front of the Sarno Gate [1,2,3,4].

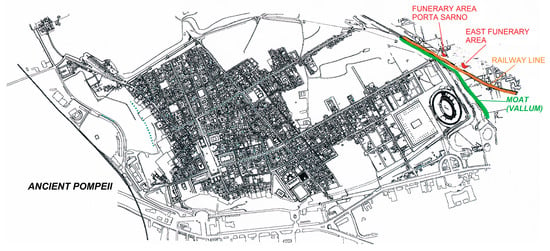

This periurban funerary area, in some cases called a suburb, was discovered during the survey carried out in 1998 for the purpose of building a double road for the Circumvesuviana railway line, which runs alongside the walls of Pompeii near Porta Sarno. The excavation identified extensive tombs in a sector that is separated from the amphitheatre by a particularly inaccessible section of the moat (vallum) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map of Pompeii. Location of the funerary areas outside Porta Sarno (map: Pompeii Archaeological Park).

The excavations were conducted under the supervision of the Superintendence and Maria Lucia Cinquepalmi at the beginning of 1998. A summary of these excavations was published by D’Ambrosio in 1999 [5,6].

A complete description of the funerary areas along the ancient road that runs parallel to the banks of the river Sarno, including the Samnite phase (end of the fourth century to the end of the second century BC), was published by G. Stefani in the project documentation for the course of the Circumvesuviana. She describes the area located 90 m from Porta Sarno as “an abandoned necropolis on the bank of a river” [7]. She reports that the burial area is bordered to the east by a boundary wall built in opus incertum, beyond which were cultivated fields. The burial area is characterised by the presence of more than 50 cremation burial sites that are marked on the surface by anepigraphic stelae carved from lava stone. At the centre of the excavated area, we found a collapsed funerary monument with a sculpted head belonging to a male bust and carved of grey tuff. Two other tuff heads were found. Based on the hairstyle, one of the female heads was dated to the Augustan period. Stefani also suggested that the area had already been abandoned by the time of the eruption in AD 79, given that the area is affected by the presence of a thick layer of subsoil on which widespread traces of combustion were evident, in addition to a large scattering of animal bones.

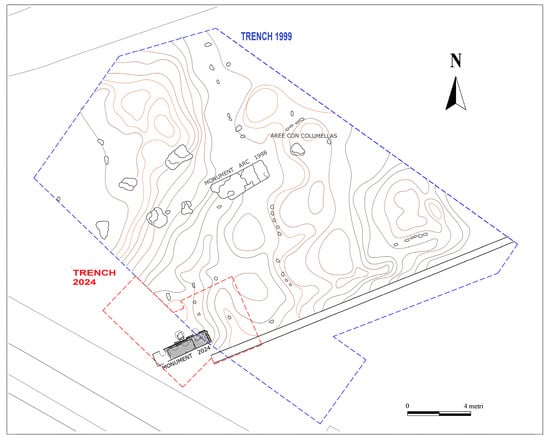

During the 2018 campaign, we studied the materials that were described as having been deposited in the female baths of Pompeii, where we located two stelae and five cinerary urns. These two fragments of tombstones carved in lava stone were located in the warehouse together with other stelae from different necropolises. One of them was quadrangular in shape with a circular perforation to facilitate its transport. The other was a fragmented female-shaped stela. Inside the urns, calcined bones were found beside symbolic objects such as coins and fragments of a funerary bed. Thus, we were able to carry out a micro-excavation and anthropological study of the five urns. By studying the materials from the described funerary area, we learned that more investigation was needed in accordance with the amount of findings from this area. In addition, the presence of a boundary wall suggested the existence of a funerary enclosure, in which members of the same family or lineage could be buried side by side. Our approach to investigating the area respected the limits of the 1998 excavation (Figure 2). Therefore, the first task was to locate the enclosure wall found in 1999 and the limit of the pyroclastic currents from the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. Once located, we planned an excavation area of four metres by four metres between the enclosing wall and the edge formed by the volcanic deposits (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

General plan of the excavated trenches (map: Pilar Mas and Joaquin Alfonso).

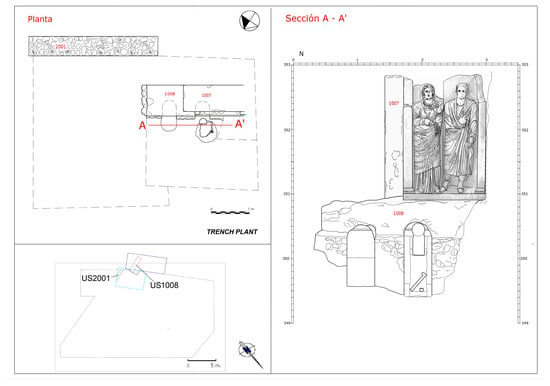

Figure 3.

Plan, elevation, and section of the tomb (graphic: Pilar Mas and Joaquin Alfonso).

Our scientific analysis applies a decidedly interdisciplinary method that allows for an optimal assessment of funerary customs and rituals and a restitution of their gestures and actions. An exhaustive and precise record that follows the sequence of the original stratigraphic-temporal disposition of each of the elements is essential [8,9,10]. Archaeological analysis of the funerary area implies a precise recognition of sediments, structures, materials, and objects, but also the actions related to them, constructions, visits, transfers, abandonments, and destructions. The management of death is also an element of social definition and identity, a faithful reflection of the status of the living, since both the biological and the cultural dimensions extend beyond death.

The analysis of the human remains, the treatment of the corpse, the cremation, and the selection of and collection on the pyre, as well as its deposition in the definitive place of the grave, are decisive. The nature of the remains and traces that are left, such as animal remains which are used as offerings or consumed at feasts, ointments which were used as perfumed oils, containers for liquids such as wine or milk, lamps, coins, human bones, or charred plant remains, are often evidence of momentary actions and, therefore, their recording and identification must be precise in order to identify whether they are part of the funeral or of the subsequent commemorations.

The complete graphic and topographic representation of each of the elements found in the funerary area and the systematic recording of them in situ is essential to recognise, reconstruct, and interpret the funerary and commemorative actions that took place. Likewise, the exhaustive collection of all of the elements and materials for their subsequent analytical study is also imperative, and, therefore, all of the excavated sediments were sieved, which resulted in us obtaining remains of burnt pine cones and pine kernels from the pyre.

In our research, apply an exhaustive methodology for the study of cremations, which begins with the study and classification of the context and continues with the in situ micro-excavation of the cremated human remains. Each bone fragment is recorded, identified, analysed, weighed, inventoried, and photographed, and then their number, weight, colour, sex, age, pathologies, etc., are entered into a database that allows us to know the percentages of the different bones and anatomical regions.

Our objective is to identify the physical characteristics of the cremated individuals, which allows us to develop a biological profile and to make interpretations about the conditions of their life and death, but also to identify arrangements for cremations and funerals. This is essentially an interdisciplinary approach that makes use of various analytical techniques to decipher all the materials deposited in the tomb, which include human and animal remains, ointments, coins, vessels, various other symbolic objects, and remains from the pyre.

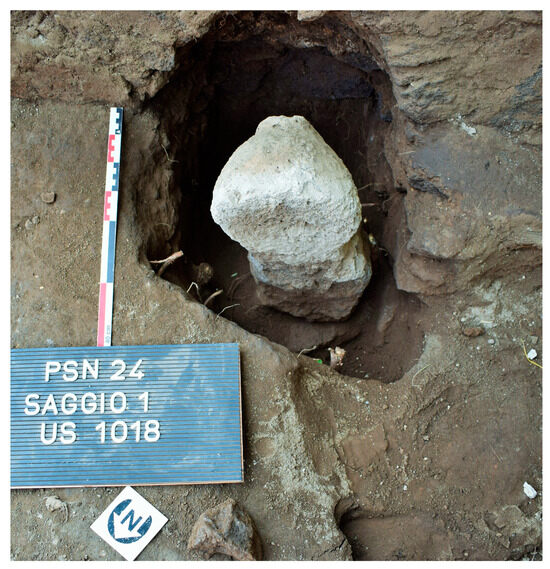

The first discovery was a wide wall located 0.94 m west of the boundary wall (Figure 4). This wall is built in opus incertum and is covered with painted stucco. Opus incertum was a construction technique used in Pompeii to create walls with an irregular stone face [11]. It was a common method of constructing walls in the first style of wall decoration in Pompeii. The irregular stones that formed the walls were usually tuff stones. Tuff stones are not very durable building stones, so they were preserved with protective stuccoes [12]. A small portion of the corner of this wall had already been found during the 1999 excavation, as attested by some labels nailed to the wall. Our excavation recorded that this wall is 0.81 m wide and formed a funerary structure whose west-facing facade contained several recesses or niches for cremation burials. In front of one of the niches there is a stela (columella) with a schematically sculpted head with a bun hairstyle, indicating the presence of a female burial [13] (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Funerary monument located at a distance of 0.94 m from the boundary wall situated behind, suggesting that the monument is within a bounded enclosure (photo: Joaquin Alfonso).

Figure 5.

Stela (columella) in front of the niche corresponding to the female relief (photo: Llorenç Alapont).

Figure 6.

Head stela sculpted with a bun hairstyle (photo: Joaquín Alfonso).

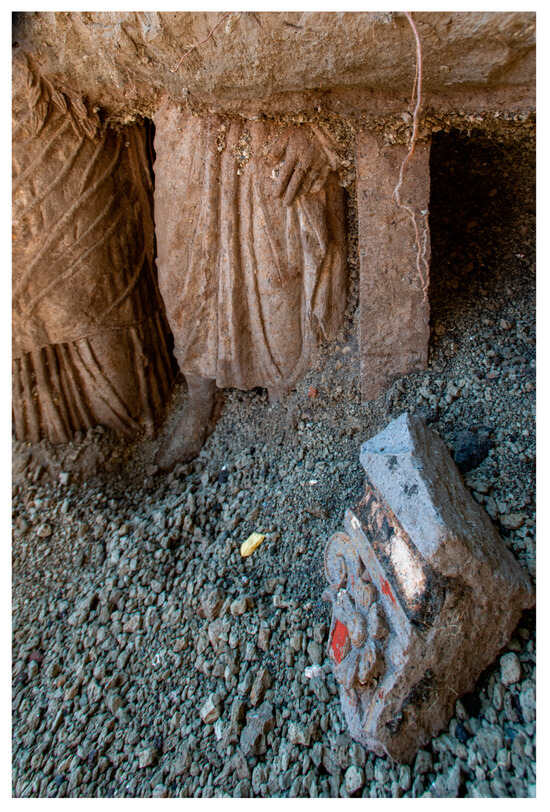

The wall extended south and was buried by deposits of pumice stone and compacted ash. Above the wall containing the niches, at a distance of 1.15 m from its northern end, there is another wall of opus incertum, which is decorated with painted stucco that had a width of 0.68 m and a height of 1.95 m. This wall forms a structure which frames a detailed high-relief carved tuff stone. However, ongoing petrographic and rock testing studies and field observations indicate that the relief is carved in grey tuff. Grey tuff is a volcanic stone of local origin that was widely used in public and private constructions in ancient Pompeii. In fact, grey tuff is the stone that was most commonly used in the edification of the tombs of the necropolis of Porta Nocera and Porta Stavia. In addition, ancient quarries of grey tuff have been identified in the Sarno river plain and Insula meridionalis in Pompeii (Kastenmeier et al. 2018 [14]). Even the use of grey tuff stone has chronological implications, as it was used in buildings constructed between 6th and 1st century BC [14]. This period has even been described by the term “The Tuff-period (B.C. 200–80)”, which Engelmann described as being “so called after the grey tuff-stone used by preference for public and private buildings.” As an example, the Temple of Apollo dates from this period [15]. The Romans developed a good knowledge of the diverse material properties of the tuffs over centuries of use and exposure. Early in its use, the soft grey tuff was particularly suitable for detailed sculptural carving [12].

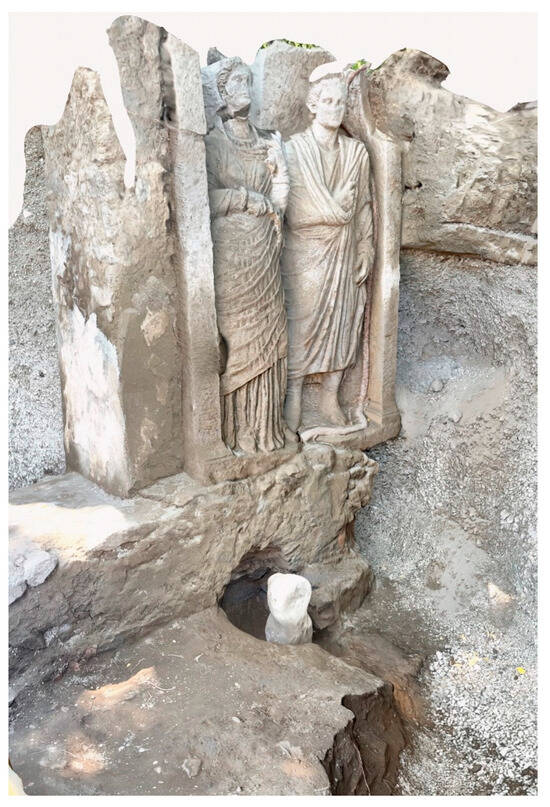

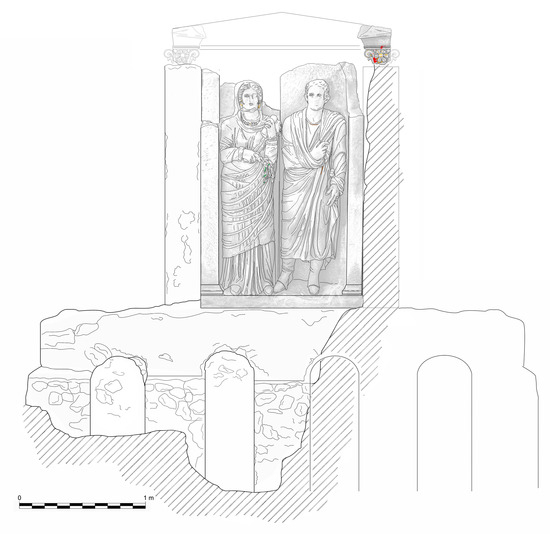

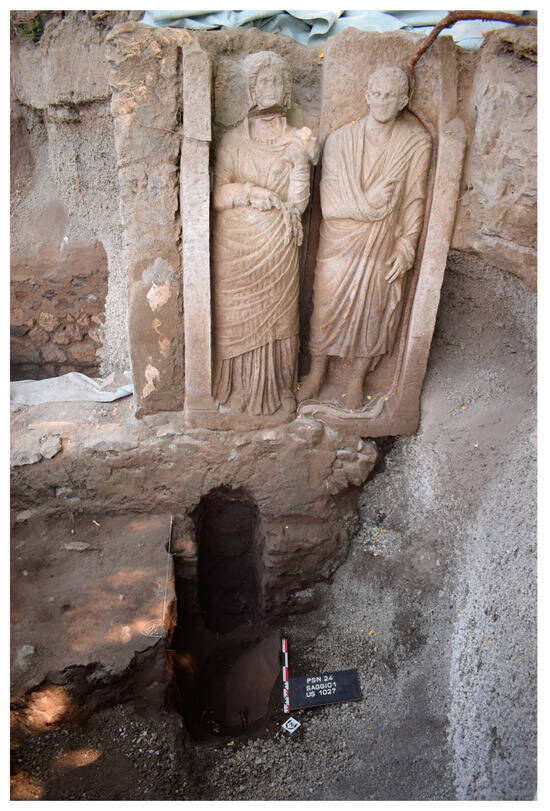

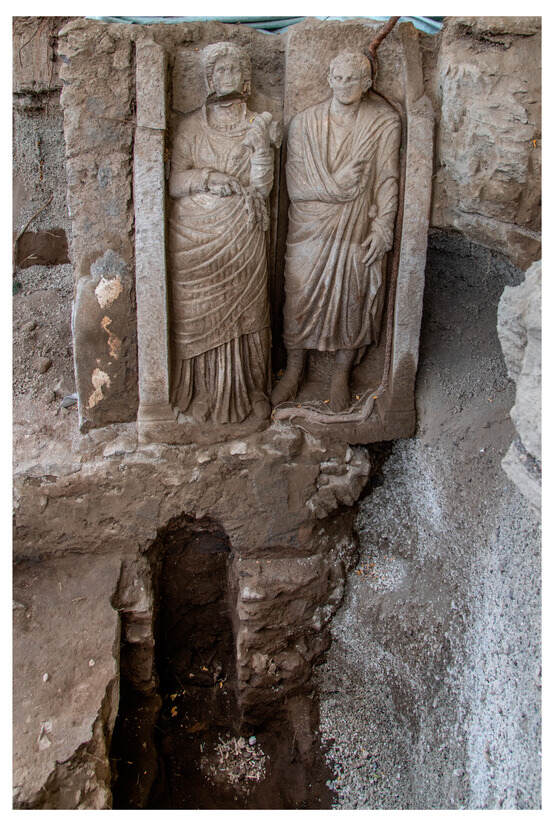

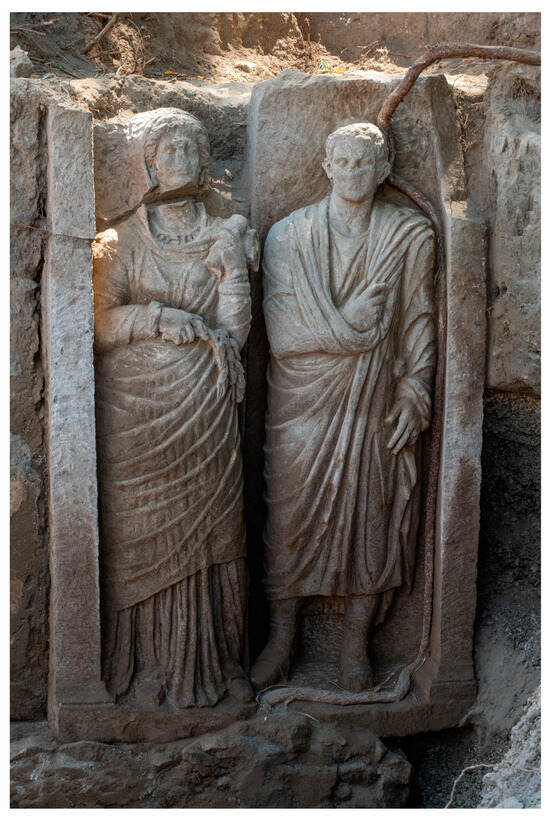

After stratigraphically excavating and removing the levels of pumice stone and compact ash, the life-size representation of a couple in high relief was exposed (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Reliefs of a life-sized married couple (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

After the reliefs were exposed, we were able to ascertain that the niche marked with the stela corresponded to the woman located just below her relief. We could also recognise the presence of another niche under the relief of the man. However, the niche corresponding to the male figure was on the south side of the wall, and almost half of the tomb had collapsed and was thus not visible, since it was completely covered with pumice. The pumice burying the tomb confirms that the southern half collapsed as a result of earthquakes prior to the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius and that the structure was certainly standing before the eruption. In fact, the woman’s head was separated from the rest of the sculpture at chin level by the pyroclastic ash flows. A fragment of the decorated pediment, which originally crowned the tomb, was found under the image of the husband and provides further evidence that the structure partially collapsed during an earthquake (Figure 8). This stratigraphic sequence of pumice stone and pyroclastic levels that is attached to the relief and the niche structure is evidence that the tomb was standing and in use until the time of the eruption, and that, at least, this enclosure was not abandoned at the time prior to the eruption, as was claimed in the publication of Di Maio and Stefani.

Figure 8.

Fragment of the pediment fallen in front of the male relief (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

2. The Tomb

Originally, the tomb would have consisted of a structure built of opus incertum covered with painted plaster which would have had a a width of 0.81 m and a length of approximately 4 m, but its length is only preserved up to 2.72 m because the rest of the structure collapsed and was covered by the deposits of pumice and ash. This structure was 1.60 m high, which would only have been visible 0.60 m above ground level during the first century AD. The rest of the structure, marked by a step from which it widens, would be underground. On the west-facing facade of this structure, there were originally four niches for cremation burials: the side niches and the two central ones corresponding to the sculptural relief. Only three of these niches have been fully preserved, with the one corresponding to the male only being partially preserved. The niches are vaulted and have a width of 0.42 m and a depth of 0.44 m. The height of the niches is 1.21 m, but only the vault (approximately 0.34 m) would be visible, and the rest would have been below the level of the floor. The side niche to the north of the structure was never used since it was filled with large stone blocks, sealed with masonry, and covered with painted plaster. On the other hand, the vault of one of the central niches corresponding to the female figure was open, with a tuff stone columella in front which schematically represented the head of a woman with her hair tied up in a bun [13].

The structure described above, consisting of a wide wall with vaulted niche openings on its façade, serves as a podium for a large high relief sculpture of two spouses, which will be explained in detail in the following section. Resting on top of this structure is a wall made of opus incertum that is covered with painted plaster and measures 2 m high, 0.68 m wide on the north side, and 0.70 m wide on the facade side. This wall frames and supports the two life-size high-relief sculptures, which were sculpted separately on two different ashlars (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Image of both reliefs separated for restoration. The rectangle delimited with a red line shows the place where the side of the painted frame is located. (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

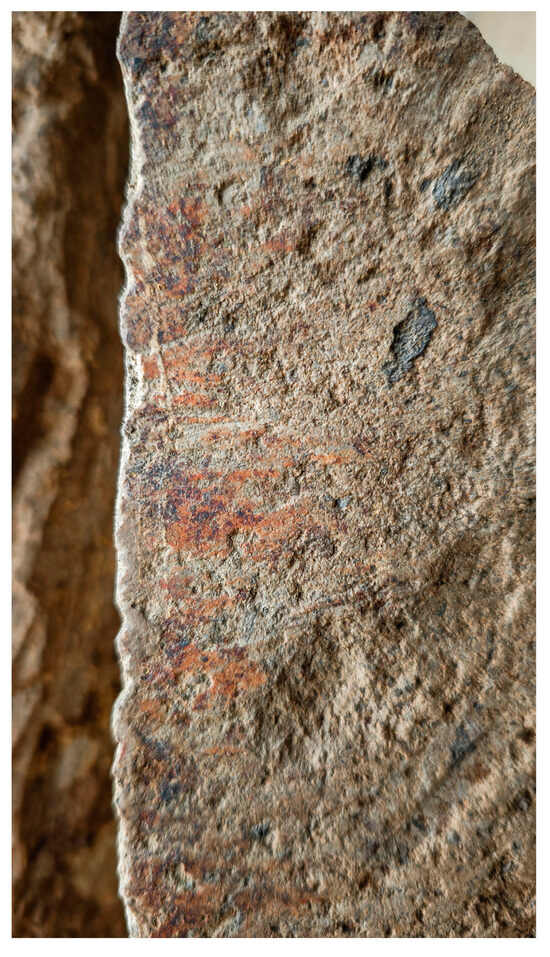

The figures were fully polychromed, as traces of pigment can be seen throughout both reliefs, with the green of the laurel leaves and the yellow of the amphorae earrings being particularly evident. We expect that the restoration work being carried out will allow the pigments to be seen more clearly, as the study of the polychromy used for the statues is also underway. Nevertheless, initial observations of the separate figures have revealed traces of paint on the side of the frame of the female figure that joined that of the male figure (Figure 10). This means that the female figure was made first and was displayed alone for some time until the male figure was added.

Figure 10.

Detail of the side of the painted frame (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

Nevertheless, both reliefs are perfectly joined, with the foot of one of them placed next to the foot of the other, making it seem as if they were the same relief. In fact, both reliefs have a jamb sculpted at their side with mouldings (a cavetto on listel) that frame the figures in a single scene. The sculptures were surmounted by a pediment that was decorated with marquetry (as indicated by the remains of charred wood) and an architrave decorated with scrolls and flowers that were painted in red. The flowers, which have six compound petals, can be identified as Coleostephus Myconis (wild chrysanthemum) (Figure 11). We can deduce that the pediment crowned the reliefs due to the discovery of a large portion of the same pediment in front of the feet of the male image, inside the pumice stone deposits (Figure 12).

Figure 11.

Pediment, which originally crowned the tomb (photo: Llorenç Alapont).

Figure 12.

Hypothetical reconstruction of the tomb crowed by the pediment (graphic: Pilar Mas).

3. The Funerary and Mortuary Rituals of the Woman’s Sepulchre

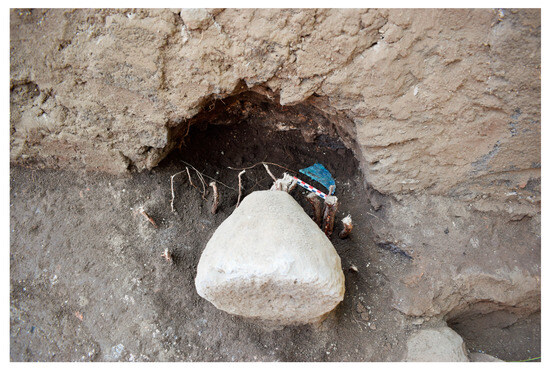

A floor level, designated the interfacial (UIS 1031), was recorded in front of the tomb façade, situated just above a large fill (US1020), which contained numerous ceramics remains, most of them fragments of thin-walled vessels and ceramic ointment jars that indicate continuous visits to the funerary space [16,17]. In front of the niche corresponding to the wife’s relief, a female stela sculpted in tuff marked the sepulchre. Only the head of the stela was visible, with the rest of the columella having been buried in a rounded pit (this pit is identified in the stratigraphic section of Figure 2 with the number US1019), and rested on its eastern (rearward) cut. Inside that same niche behind the stela, we found a glass ointment jar with part of its neck and rim missing in a small pit (identified in the stratigraphic section of Figure 2 with the number US1017), and beneath it a large fragment of a broken bronze mirror (Figure 13 and Figure 14).

Figure 13.

Broken glass ointment jar in a small pit (US1017) (photo: Joaquin Alfonso).

Figure 14.

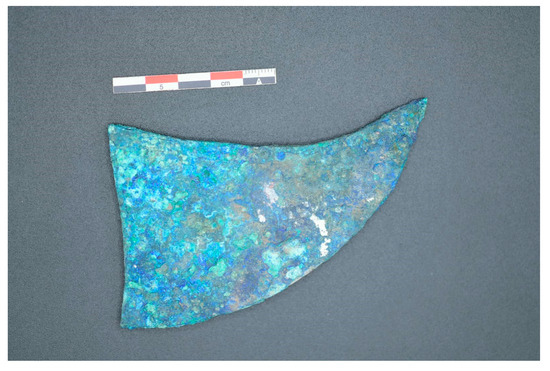

Large fragment of a broken bronze mirror (photo: Joaquin Alfonso).

The objects were not found in the same pit as the stela but in a more superficial pit. The presence of ointment jars represents the final gesture of pouring perfumed oil on the bones before closing the urn forever and rendering the tomb as a locus religious [18]. The broken glass ointment jar provides clear evidence of rites of libation being performed at the sepulchre of the deceased with perfumed oils [17] (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Broken glass ointment jar (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

The libations could occur at the site of the cremation during the preparation and burning of the body on the pyre, in the tomb during the acts relating to the burial of the urn in its final resting place, or during visits to commemorate the memory of the deceased. Therefore, perfumes were an essential part of funerary rituals (Van Andringa 2021 [17]). Pleasant smells were crucial to the multisensory atmosphere of funerals. Perfumed oils and burning incense counteracted the impure stench of death emanating from the decomposition and cremation of the corpse [17,19]. Therefore, the deposition of ointment jars is undoubtedly intentional as they invoke ritual libation as an offering during the celebrations in honour of the deceased. However, it is more difficult to know whether the breakage of the ointment jar was intentional or accidental, due to the fragility of the object itself. It should be borne in mind that both broken and intact ointment jars are attested in funerary contexts. In this regard, any intentional breakage of these objects would confirm that they were only used to contain substances necessary for funerary practices. Furthermore, in the case of a voluntary breakage, the action can represent a personal or collective decision of the funerary party [20]. Regarding the broken mirror (Figure 16), several cases of this type of object have been reported in funerary contexts [21,22,23]. For example, recently, in the Sepolcreto of the Via Ostiense we found a mirror fragment next to a tintinnabulum inside a cremation urn [24,25]. Mirrors had polyvalent functions and meanings in ancient Rome and were understood as objects with special powers. They served as mediators par excellence, symbolising a threshold between worlds, which ensured their connotation as magical objects [26]. Breaking a mirror was seen as an omen of misfortune because it was thought to also break the connection to the soul [27]. Mirrors were also used by women for prophesying by looking at their shiny surface [23,28].

Figure 16.

Fragment of a broken bronze mirror (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

The pit in which the columella was placed was filled with dark-coloured sandy-clay soil (US 1019). Within this context, we found a coin (Figure 17). The reverse of the coin depicts the god Neptune holding a trident (Figure 18). The symbolic deposition of a coin in the tomb is a frequent and recognisable funerary gesture. However, its meaning is difficult to pin down and it may have different interpretations [29]. The traditional and most widespread interpretation, based on Greek and Latin iconography and literary sources, understands the coin as ‘Charon’s obol’ i.e., the payment of the toll that gave access to the afterlife. However, in recent years, this interpretation has been refined in favour of more subtle explanations. Currently, coins found in sepulchral contexts are interpreted as having two main functions in addition to the aforementioned one of being a tribute for the afterlife and a guarantee of transition between life and death. The first function considers the coins as an offering, both of the deceased and of the people close to them. The second function sees the coins as amulets or talismans endowed with the magical power of defending the tombs and preventing the dead from coming back to life in the form of lemures or larvae (bad spirits) due to being made of metal and their round shape [30,31,32]. When interpreting the symbolic and ritual meaning of coins in the funerary sphere, it is necessary to note the prophylactic value of metal in the context of the beliefs and superstitions of the ancient world, in which coins were magical objects [32]. Lastly, it should not be forgotten that the gesture of depositing a coin in a tomb was not mandatory, although it was frequent. Therefore, its occurrence was greatly influenced by personal choice and behaviour within the private or familial sphere, and did not have any honorific, social, or economic motivation.

Figure 17.

Coin inside the pit in which the columella was placed (photo: Joaquin Alfonso).

Figure 18.

Coin with the god Neptune holding a trident on the reverse (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

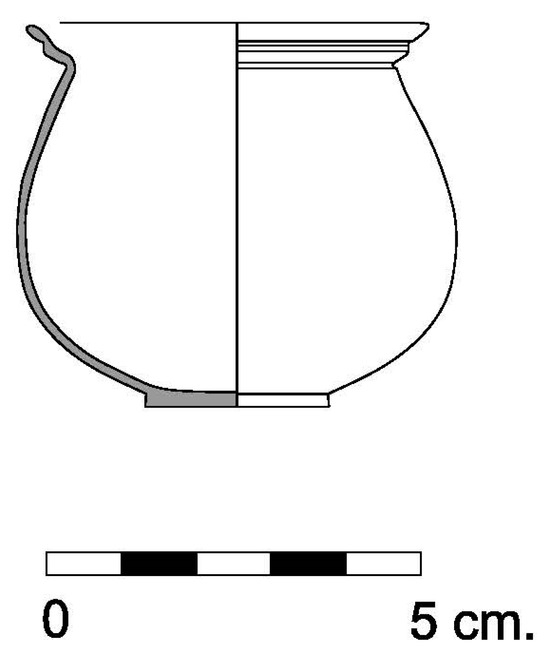

Below the sediment where the coin was found, a new stratum (US 1025) was covering a flat tile. This tegula was leaning against the wall, covering and closing the burial (Figure 19). Below the tegula, another stratum covered a small, complete, and intact thin-walled vessel that had been carefully placed on top of the sediment where the remains of the cremation were deposited (Figure 20). This vessel is an indicator of the ritual act of consecrating the tomb, perhaps by pouring wine over the bones after depositing them in the lower part of the grave [17] (Figure 21 and Figure 22).

Figure 19.

Tegula covering and closing the burial site (photo: Joaquin Alfonso).

Figure 20.

Small thin-walled tegula placed on top of the sediment where the remains of the cremation were deposited (photo: Joaquin Alfonso).

Figure 21.

Thin-walled vessel (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

Figure 22.

Thin-walled vessel (drawn by Ana Miguélez).

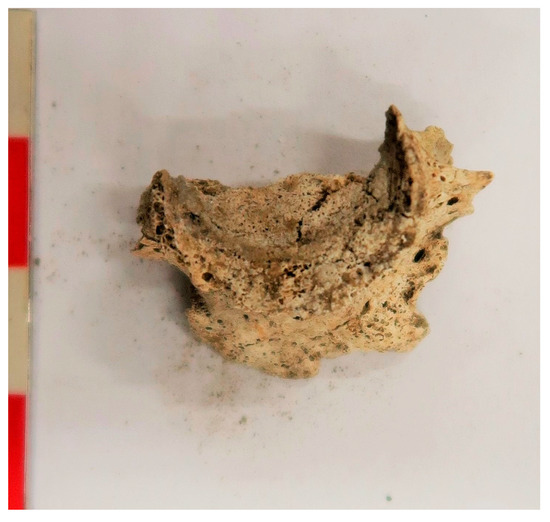

Finally, at the base of the tomb, we found a large quantity of burnt human bones (Figure 23 and Figure 24), all of which were white in colour, indicating that they had been cremated at temperatures of over 650 °C [33,34]. The observation of osteoarthritis in several joints, particularly in the thoracic and cervical vertebrae, suggests that the subject was of mature age [35,36,37] (Figure 25). The morphology of the bone fragments, most of them identifiable, indicated that they belonged to a female individual [38,39,40] (Figure 26). Numerous remains of charcoal, ash, and pine nuts were also found with the bones.

Figure 23.

Large quantity of burnt human bones at the base of the tomb (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

Figure 24.

Burnt human bones buried directly in the pit (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

Figure 25.

Mandible and teeth of the cremated individual (photo: Llorenç Alapont).

Figure 26.

Cervical vertebra with signs of osteoarthrosis (photo: Llorenç Alapont).

4. The Reliefs

The monumental character of the tomb is given by the display of the reliefs of a couple. The two life-sized figures are sculpted separately on two different tuff ashlars. However, the two reliefs are perfectly united, appearing to be a single sculpture. Both the bodies and heads of the well-to-do young married couple are shown frontally in high relief, proudly emphasizing their status through the language of imagery [41] (Figure 27). It is also possible that the couple are mother and son. As the titulus sepulcralis that would identify the figures and their names has not appeared, we cannot know with complete certainty the relationship between the two figures. Although reliefs showing a mother with her son or daughter, or both parents with their children, are known (portrait busts of Petronia Hedone and her son [42], funerary monument for Sextus Maelius Stabilio, Vesinia Iucunda, and Sextus Maelius Faustus, (North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, NC, USA), Farewell to a Boy (Vatican 2167), portrait of Lucius Vibius and Family [43]), this type of relief is very different from the model presented in this paper. However, our sculptural ensemble is very similar to the models of other known marriage reliefs, such as those of Marco Virgilio Eurysaces and his wife Atistia from Eurysaces in the baker’s tomb [44] and the funerary relief of a married couple from the Via Statilia in Rome (Centrale Montemartini Museum, I. 43) [45]. The delicacy and detail of the sculpture is remarkable. We can appreciate the careful carving of the hands, fingers, and nails. We can also see the detailed work on the folds of the clothing and the ornaments—the rings, bracelets, necklace, etc.

Figure 27.

The young married couple are shown frontally in high relief (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

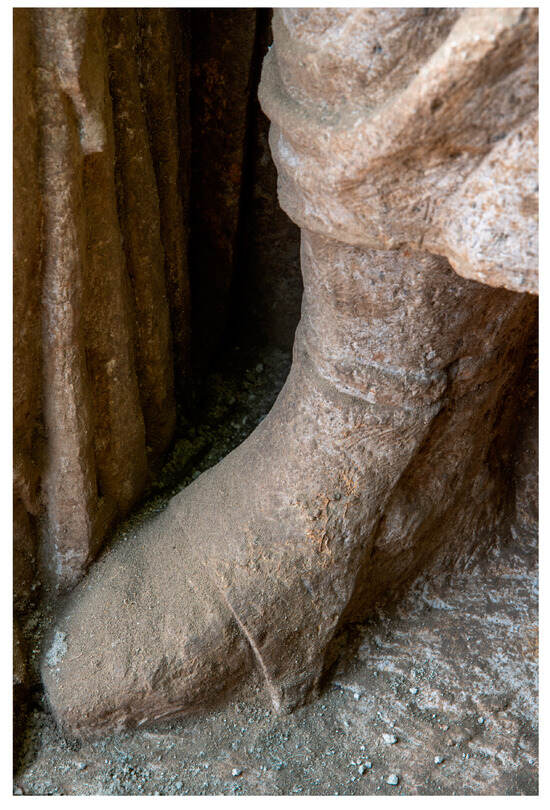

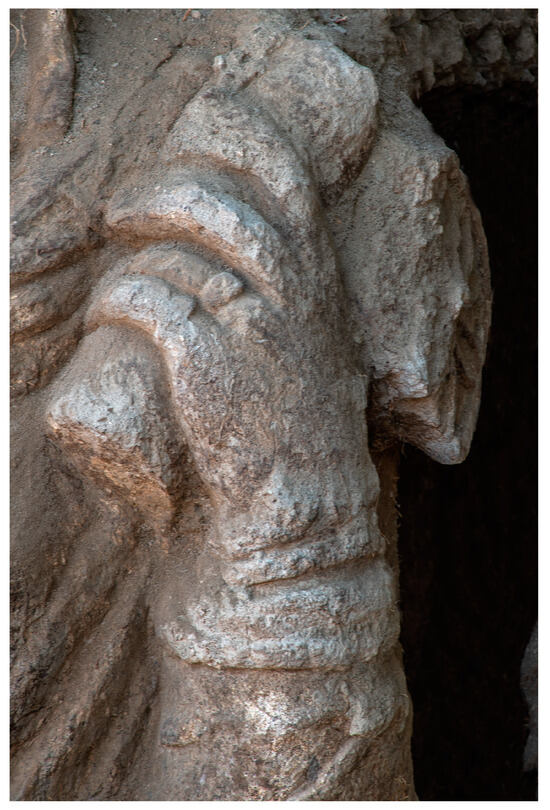

The husband’s stela is 2.06 m high, and his figure is 1.75 m tall. Visual analysis of the piece shows that he is a Roman citizen, which is distinguished by him wearing a toga [46]. The toga is draped over the man’s left shoulder, wrapping around the left arm, and extends down, with his hand resting against his thigh on the dorsal face with its fingers spread apart. He holds the sinus with his right hand, and the toga wraps around his right arm with the elbow bent to finally rest on the right shoulder. It is the peculiar arrangement of the front folds that gives the Roman toga its unique character. The toga was the peculiar distinction of the Romans [47]; hence, men who wore them were called togati or togata gens by authors such as Virgil and Marcial (Virgili, Eneida, I.282; Marcial, XIV.124). In our case, the right hand holding the toga on the chest determines the shape and the fall of the folds, which open radially from the grip of the right hand. The toga reaches to the middle of the shin, with the clear intention of showing the footwear that identifies him as a member of the upper classes. The feet were shod with the calcei patricii (symbols of high social status) [48], which reached to the mid-shin and were tied at the instep (Figure 28). Further indicators of his status are the detail in the curls of his hair and eyes, as well as the ring on the proximal phalanx of the ring finger of the left hand (Figure 29) [49].

Figure 28.

The feet were shod with the calcei patricii (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

Figure 29.

Ring on the proximal phalanx of the ring finger (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

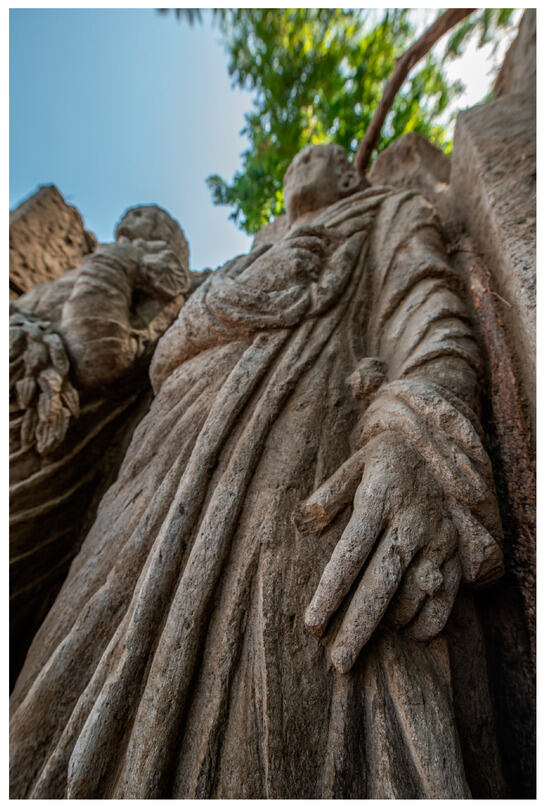

The relief of the wife shows a series of attributes that give her a particular relevance. The woman’s stela is 1.86 m high, and her figure is 1.77 m tall. The young bride is shown veiled, being dressed in a large cloak (himation) over her tunic (chiton), in accordance with the Puditia sculpture type. The iconographic model of Puditia is a creation from the Hellenistic period that was widely taken up in the late Republican and Imperial periods for female sculptures, both honorary and funerary [50]. Covering the tunic is the himation that envelops the entire figure, with diagonal and horizontal folds that fall successively one on top of the other under the right arm. The chiton is visible just below the neck, where it forms small V-shaped folds, as well as on the lower legs and feet. Here the pleating is meticulous, fine, and deep. The tunic falls below the cloak with vertical pleats until it covers the closed shoes, calcei muliembres, where only the toe is visible. The head is veiled, and the arms are folded over the body [51]. All these characteristics highlight the qualities of the reserved, demure, and honest woman [52].

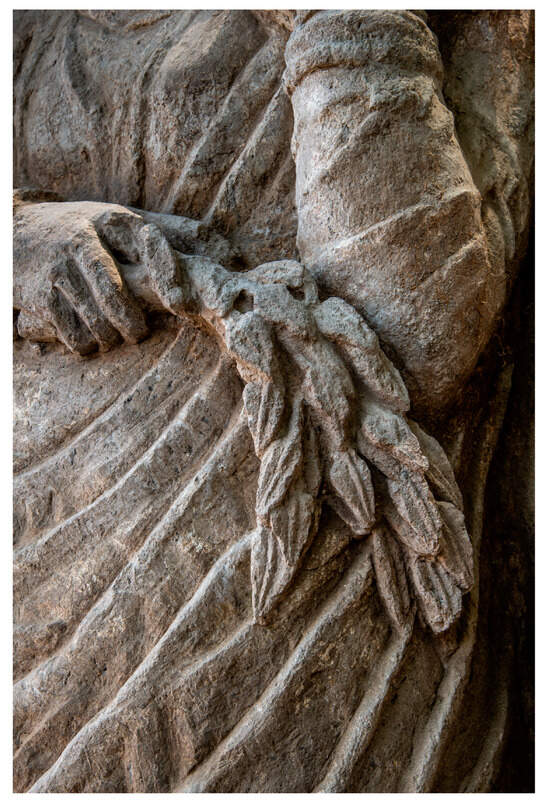

The figure also shows numerous particular ornaments. The right hand, which is clasped at the right shoulder with the elbow bent, shows two bracelets on the wrist and two rings, one on the proximal phalanx of the ring finger and the other on the proximal phalanx of the little finger (Figure 30). The ring on the ring finger can be interpreted as the wedding band. The ring on the little finger may discretely display their wealth, in accordance with what Pliny describes [49]. The young bride is also adorned with amphora earrings. Amphora-shaped pendants are also present on the necklace, which gives this personal adornment an archaic character. Nevertheless, the main element of the necklace is the lunula, a crescent moon hanging in the centre of the necklace (Figure 31).

Figure 30.

Two bracelets on the wrist and two rings, one on the proximal phalanx of the ring finger and the other on the proximal phalanx of the little finger (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

Figure 31.

The main element of the necklace is the lunula, a crescent moon hanging in the centre of the necklace (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

The lunula was one of the amulets used to ward off evil forces, and was worn by women from birth until marriage [53]. The symbol of the crescent moon also had an atavistic and primordial meaning that was linked to the fertility of the earth, abundance, and rebirth, and which was influenced by the lunar cycles (Varro, Rust., 1, 1). Care is present in the execution of all her personal adornments and in the details of her face, her eyes, her lips, and the curls of her hair underneath the veil. In addition to all these attributes, there are other unique elements that give this woman a special religious status. The statue shows her arm with the elbow bent, and her forearm in front of her body, resting on her abdomen, with her hand holding an aspergillum of laurel leaves which preserves elements of green paint (Figure 32 and Figure 33).

Figure 32.

The statue shows her hand holding an aspergillum (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

Figure 33.

The aspergillum of laurel leaves preserves elements of green paint (photo: Alfio Giannotti).

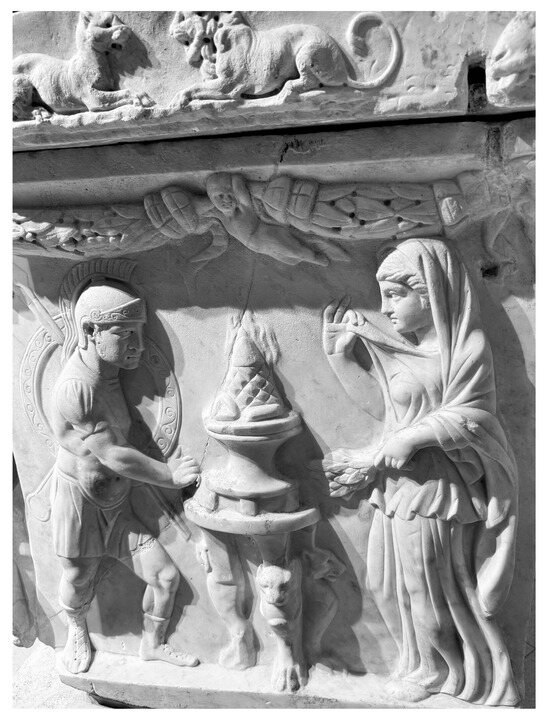

The asperigillum is a laurel or olive branch used by priests and priestesses to purify and bless spaces by dispersing the smoke of incense or other aromatic herbs burned during religious ceremonies. A clear example of this iconography is found on a sarcophagus exhibited in the Museo Centrale Montemartini in Rome (sarcophagus with battle scenes, M.C. inv. 2141, second century AD), on which a priestess with a veiled head holds an aspergillum, dispersing the smoke of a burning cauldron to bless a soldier facing battle (Figure 34).

Figure 34.

Sarcophagus with battle scenes from the graveyard in the Via Portuense, in Rome, uncovered in the Viale Gianicolense (1226) (photo: Llorenç Alapont).

Showing and holding this ceremonial instrument indicates that the woman was a priestess. The left elbow is flexed with the hand resting against the shoulder, showing the two rings and holding an object, which could be the cartridge that contained the marriage contract or perhaps the container where incense was extracted and stored [54,55]. Since women in Roman society were commonly relegated to the domestic sphere and to the tasks of the Roman matron, being a priestess was the highest social rank to which a woman could aspire. Priestesses had an important role in the public sphere. They had a position of power that was far removed from other women and very similar to that of male priests.

The lunula was previously described as an amulet worn by girls before marriage. On the eve of the wedding, the bride would gather her clothes, her dolls, and her lunula, everything that had represented her life up to that point, and offer it to the Lares or to the goddess Venus (Moro Ipola 2023, 282 [53]). The lunula present on the necklace of the married woman may thus define her as a priestess of the goddess Ceres. In Roman religion, Ceres has a symbolic connection with the moon, as the phases of the moon were thought to correspond with the growth and harvest of crops, solidifying Ceres’ role as a fertility goddess [56].

Apart from the Vestals and the Salian virgins, the priestesses of Ceres were the only public priestesses in Roman society in the sense that they represented the whole community, and they received support and public funds from both the decurions and the imperial finances, which implied that they possessed great prestige [52,57]. It is likely that only women of prominent families were able to hold this position. According to Cicero (Cic., Verr., 2, 4, 99), just like the priestesses of the goddess, the Roman sacerdotes Cereris were of decent reputation. The cult of Demeter-Ceres had great influence in Southern Italy, particularly in Campania and Magna Graecia during the archaic period. In addition, the existence of a flamen Cerialis dating from the archaic era implies that the sociocultural importance of the goddess Ceres was highly influenced by that of the goddess Demeter. Priestesses served the goddess in ancient Demeter-Ceres cult sites, especially in Campania. In fact, the priesthood of Ceres was one of the few in which women have been attested epigraphically. Particularly in Pompeii, seven known positions of public priestess were dedicated to Ceres, and just one of them also notes her dual role as a priestess of Venus and Ceres.

From the symbolic objects displayed by the woman, we can deduce that this is the only statue representing a priestess that has been identified so far in Pompeii, apart from Eumachia. In fact, this is one of the rare cases in which priestesses display their characteristic attributes. In most cases, priestly identification is only possible thanks to an inscription accompanying an image, since the portraits of priestesses do not present any different characteristics from those of a private citizen or one with different functions, and show the priestess neither in her dress nor in her head dress. This is precisely the case of Eumachia, for which the inscription identifies her as patron saint of the dyers’ guild and public priestess, without specifying which cult. On the other hand, it makes sense that priestesses do not display the attributes that characterise goddesses, such as, in this case, grains or cornucopiae, as these are proper and exclusive attributes of goddesses and are forbidden to humans, and their display would be an offensive attempt for the priestess to deify themself.

Ceres priestesses are well represented in the epigraphic record of Pompeii. In total, 11 priestesses are named in Pompeian inscriptions. Of these, four are identified exclusively as public priestesses without an attributed deity. All of these priestesses lived in the Augustan or early Tiberian period except for Clodia, who is buried in a family tomb at the Porta di Nocera that dates to the Neronian period (Eumachia (CIL X 810 = ILS 3785 = AE 2001: 793 = AE 2006: 249; CIL X 811; CIL X 812; CIL X 813 = ILS 6368 = AE 2006: 249), Holconia (CIL X 950 = CIL X 951), Istacidia Rufilla (CIL X 999 = ILS 6370), and Clodia (D’Ambrosio & De Caro 5OS)).

In Pompeii, five monumental inscriptions, four funerary inscriptions, and three honorific inscriptions refer to seven priestesses, all of them dedicated to the cult of Ceres. Two members of the Alleii family proclaim their religious role in their epitaphs.

The first one is located in the tomb of M. Alleius Luccius Libella and M. Alleius Libella at the east side of the funerary area of Herculaneum Gate, which was excavated in 1813.

CIL X 1036:

M(arco) Alleio Luccio Libellae patri aedili / IIvir(o) praefecto quinq(uennali) et M(arco) Alleio Libellae f(ilio) / decurioni. Vixit annis XVII. Locus monumenti / publice datus est. Alleia M(arci) f(ilia) Decimilla sacerdos / publica Cereris faciundum curavit viro et filio.

“To Marcus Alleius Luccius Libella senior, aedile, duovir, prefect, quinquennial, and to Marcus Alleius Libella, decurion. He lived 17 years. The place for the monument was given publicly. Alleia Decimilla, daughter of Marcus, public priestess of Ceres, oversaw the building on behalf of her husband and son”.

In the other one, Alleia holds the priesthood for two goddesses, serving Venus in addition to Ceres. Dated to the Neronian period, she is the only woman for whom this dual role is recorded.

EE 8.315:

Alleia Mai f(ilia) / [sacerd(os) Veneris / et Cereis sibi / ex dec(urionum) decr(eto) pe[c(unia) pub(lica)]

“Alleia, daughter of Maius, priestess of Venus and Ceres, to herself, in accor- dance with a decree of the town councillors, with [public] money”.

Clodia and Lassia are two women who are also known from funerary inscriptions on a tomb found somewhere in the suburbs of Pompeii, which is now lost. There were clearly two members of this family dedicated to the service of Ceres, but how exactly they were related is not clear.

CIL X 1074a:

Clodia A(uli) f(ilia) / sacerdos / publica / Cereris d(ecreto) d(ecurionum).

“Clodia, daughter of Aulus, public priestess of Ceres, by decree of the decurions”

CIL X 1074b:

Lassia M(arci) f(ilia) / sacerdos / publica / Cereris d(ecreto) d(ecurionum).

“Lassia, daughter of Marcus, public priestess of Ceres, by decree of the decurions”

The only dedicatory inscription naming Ceres which survives comes from the Eumachia Building in the Forum, which names three priestesses of Ceres, two of which have the same name.

CIL X 812:

Eumachia [L(uci) f(ilia)] / sacerd(os) publ(ica). // et // Aquvia M(arci) [f(ilia)] Quarta / sacerd(os) Cereris publ(ica). // [et] // [Heiai Ru]fulai / [M(arci) et L(uci) f(iliae)] sacerdotes / [Cer]eris publ(icae).

“Eumachia, daughter of Lucius, public priestess, and Aquvia Quarta, daughter of Marcus, public priestess of Ceres, and (two) Heia Rufulas, daughters of Marcus and Lucius, public priestesses of Ceres”

Regarding Eumachia, I think it is important to discuss the two inscriptions that identify her as a public priestess. One of them is engraved on the pedestal of her statue located in the Porticus of Concord in the Forum of Pompeii. The other is engraved over one of the two entrances. The first one was dedicated to her by the guild of the fullers (wool weavers and washers), attesting to her generosity to these workers: “EVMACHIAE L F SACERD PVBL FVLLONES” (CIL, vol. X, no. 813; Pompeii, first century AD). The translation of this inscription is “to Eumachia, daughter of Lucius, public priestess, from the fullers”. The statue, along with several architectural features, is the reason that archaeologists conjecture that the building was used primarily as a wool market [58]. Although there is no symbolic element on the statue, nor is there any epigraphic element relating her to goddess Venus, several authors have nevertheless identified her as a priestess of Venus [59]. The same applies to the large inscription on the architrave above the portico columns: “EUMACHIA L F SACERD[os] PUBL[ica], NOMINE SUO ET M NUMISTRI FRONTONIS FILI CHACIDICUM, CRYPTAM, PORTICUS CONCORDIAE AUGUSTAE PIETATI SUA PEQUNIA FECIT CADEMQUE DEDICAVIT” (CIL X, 810, 811). This inscription translates as Eumachia, daughter of Lucius, public priestess, in her own name and that of her son, Marcus Numistrius Fronto, built at her own expense the colonnade, corridor and portico in honour of Augustan Concord and Piety and also dedicated them. However, inside the Eumachia building dedicated to the Augusta Concord, there was not the figure of the Pompeian Venus, but the statue of Livia as Ceres holding a cornucopia. The statue represents the Concordia Augusta personified by Livia, wife of Augustus and mother of Tiberius [60]. In fact, it is very likely that Eumachia celebrated the cult of this figure of Livia-Ceres [61].

Finally, we should not forget the schola triangular monument dedicated to an anonymous public priestess in the funerary area of Porta Nola. Based on the symbols sculpted on the slabs on two sides of the podium, the front (west) and side (south) faces, we have reconstructed the identity of the protagonist of the schola, women who held the position of public priestess. On the side face (south), a large mystical wicker basket is sculpted in the centre, an object that obviously symbolises the cult of Ceres. The basket is flanked by two identical bas-reliefs representing two vegetalised candelabra, probably alluding to the nocturnal rituals dedicated to the mother goddess. On the front face, where the titulus sepulcralis was located, in the lower right part, part of a vegetalised torch is sculpted on the right and, next to it, on the left, a large pinnatisecta plant leaf or spikes are sculpted, symbolising the cult of Ceres, according to Torelli [62], as an element that plays an important role in the myths and rites of this goddess [63]. A serpent is depicted below the plant motifs, clearly alluding to the goddess of fertility. According to Torelli, all these symbols allude to the fact that the priestess officiated at the cults of both Ceres and Venus (Torelli 2020, 340 [62]), a fact that is reminiscent of Samnite culture, in which both cults were attributed to the same priestess [64]. However, the mystical basket, the torch, the ivy leaves or ears of grain, and the serpent are all associated with Ceres on numerous coinage coins.

5. Discussion

The cremation rituals and the symbolic funerary objects, the thin-walled basin, the mirror fragment, and, above all, the broken ointment glass (type 6, dated to the Tibero-Claudian decades [20]) indicate that the tomb was in use at least until the time of the earthquakes (62–64 AD) and that the necropolis was not abandoned, as was thought, before the eruption of Vesuvius (79 AD). Therefore, the aristocratic couple depicted in the relief maintained their high status until the last years of the city.

The tomb, with a relief of a high-status couple, that was recently discovered in the funerary area of Porta Sarno is a precious portrait of the Pompeian elites from the late Republican period. The sculpture of the woman is one of the rare examples of a priestess being depicted with the objects characteristic of their religious position and the only one known so far in Pompeii. Beyond the symbolism and aesthetic quality, and the fact that there is no doubt that this couple had considerable resources, these statues and the rest of the tomb would have been of enormous cost, only within the reach of wealthy and influential women and men. The aspergilium held by the woman undoubtedly gives her a religious role, a fact that contrasts with the interesting issue of the priestesses in Pompeii. The most powerful women of Pompeii belonging to the most prominent families all exhibited priestess status, and such is the case of Eumachia and Mamia. Both built, under their name and with their funds, two of the most important works of evergetism in Pompeii that are related to the religious, social, and political spheres. Eumachia built the huge building in the forum dedicated to the Concordia Augusta and Pietas, and Mamia built next to it the temple dedicated to the genius Augusti. These constructions express the close relationship between the benefactresses and Augustu and show how the women of the local aristocracy were establishing a strong relationship with the new imperial power [65]. On the other hand, there is a tendency for some scholars to relate the priestesses of Pompeii to Venus, or more specifically, to the local version of Venus Pompeiana. She was the patron goddess of the city, whose temple, the most symbolically important for the city, located beyond the city walls, dominated the skyline for anyone approaching the city from the sea, and whose name was included in the official title of the city: Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum. However, there is only one inscription mentioning a priestess of Venus, and that is in conjunction with Ceres. In fact, the preponderance of Ceres priestesses in funerary and honorific contexts is overwhelming in Pompeii. The goddess is connected with weddings, rites of passage, funerary rites, the mundus, and prodigies. In this sense, it is true that no temple specifically dedicated to the cult of Ceres has been identified to date. Nevertheless, there are some sacred buildings in Pompeii which could well be connected with the cult of the goddess. This could be the case with the tholos well located in the triangular forum. This well, public and ritual, could represent the mundus of Ceres [56]. The relationship with the Concordia Augusta and Pietas Porticus seems much more evident due to the well being presided over by the statue of Livia as Ceres, on whose architrave up to three priestesses of Ceres are named.

The sculptural relief from Porta Sarno is further archaeological evidence of female leadership in ancient cults occurring for centuries. Women representing cults held public offices with a much broader civic commitment than was previously recognized. For the ancients, the religious and secular were intimately connected. In Roman society, the religious and the political, the public and the private, were intimately connected. The priesthood, therefore, offered the opportunity to participate in all spheres of public life [66]. It allowed one to display wealth but also to access certain levels of social and political power.

6. Conclusions

In recent years, excavations around Porta Sarno have given its funerary area previously unexpected value. These investigations are bringing to light funerary enclosures and monumental sepulchres, such as the one discussed in this paper. Our discoveries indicate that the funerary area may date back to the late-Republican period and may have been active until the eruption in AD 79, but with various changes, transformations, and even abandonments. The relevance of this area is probably due to the location of the funerary space along the access route to Pompeii, across the Sarno River and through the Via of the Abundance, as well as its age. The data provided by our study confirm that the funerary area was active during the years prior to the eruption that buried the city.

The tomb presented in this paper reveals interesting and diverse aspects of funerary customs and rituals, but above all, the presence of two particularly detailed reliefs. These sculptures belong to a large class of funerary reliefs made between the first century BC and the first century AD. Nevertheless, these types of sculptures are very rare in southern Italy. It is even more unusual to find reliefs of priestesses holding their religious objects. Even though other sculptures of priestesses are known, it is unusual that they show the iconography of their position. Although we can relate our relief to some known sculptural models, we preserve only a few images of a generic nature and these often exhibit unclear iconography.

There is no doubt that the laurel leaves held in this woman’s hand indicate that she had a religious role, which identifies her as a priestess. We understand that it is more controversial to ascribe her to the service of the goddess Ceres by means of other symbolic elements that she displays, in particular by the lunula on her necklace. However, the lunula is an apotropaic amulet of childhood that must be given to the lares before marriage, and therefore, in this case, it is devoid of traditional meaning and it is necessary to find another motif for it, which could well be its link with the goddess Ceres.

The absence of a funerary inscription prevents us from knowing the names of this couple and who they were, and, therefore, from knowing with certainty whether the sculpted couple was a married couple. However, the parallels in known funerary models suggest this. The lack of a sepulchral tituli also prevents us from knowing with certainty whether this priestess served Ceres, although the epigraphy and the honorific and funerary architecture of Pompeii suggest this.

Roman women held a relatively limited but well-defined repertoire of priesthoods, in most cases doing so on an individual basis. The female relief therefore brings attention to the active role of women acting as priestesses in the religious life of their communities. Furthermore, our sculpture could be further proof that Ceres had a clear place in the officially sanctioned religion in Pompeii, having a dedicated priestess. Through the inscriptions presented in this article, it is clear that there were priestesses of Ceres in Pompeii, but this statue provides new evidence of the importance of the cult in the city. In addition, the cult of Ceres has been linked to the popular classes. However, the ostentation of the female relief may suggest that the status of priestess was still reserved for women belonging to a relatively high social standing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A., R.C., J.A.L., J.J.R.L. and A.M.G.; methodology, L.A., R.C.; validation, L.A., R.C. and E.A.P.; formal analysis, L.A., J.A.L., J.J.R.L., A.M.G. and P.M.H.; investigation, L.A., R.C., J.A.L., A.M.G., T.H.M., V.R., A.P.P., S.A.V. and A.G.M.; resources, L.A., R.C., P.M.H., V.R., A.P.P. and E.A.P.; data curation, L.A., R.C., J.A.L., J.J.R.L., A.M.G., T.H.M., V.R., A.P.P., S.A.V. and A.G.M.; writing-original draft, L.A.; writing-review & editing, L.A., J.A.L., T.H.M., V.R., A.P.P. and S.H.; supervision, L.A. and R.C.; visualization, L.A. and E.A.P.; project administration, L.A.; software, P.M.H.; funding acquisition, E.A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data are presented in this paper—all sources of data used are cited.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alapont, L.M.; Zuchtriegel, G. The newly discovered tomb of Marcus Venerius Secundio at Porta Sarno, Pompeii: Neronian zeitgeist and its local reflection. J. Rom. Archaeol. 2023, 35, 595–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alapont, L.M.; Alfonso Llorens, J.; Cicone, C.; Hurtado Mullor, T.; Mas Hurtuna, P.; Miguelez González, A.; Puig Palem, A.; Ruiz López, J.J.; Revilla Calvo, V. Indagine sull’archeologia della morte a Pompei. Necropoli di Porta Sarno. Riv. Studi Pompeiani 2023, XXXIV, 268–272. [Google Scholar]

- Alapont, L.M.; Zuchtriegel, G.; Alfonso, J.; Amoretti, V.; Mas, P.; Miguelez, A.; Ruiz López, J.J. L’area funeraria di Porta Sarno e la tomba di Marcus Veneriu Secundio a Pompei, rifesso dell’impulso culturale dopo il terremoto del 62 d.C. Riv. Studi Pompeiani 2022, XXXIII, 208–2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alapont, L.M.; Alfonso Llorens, J.; Cicone, C.; Hurtado Mullor, T.; Mas Hurtuna, P.; Miguelez González, A.; Puig Palem, A.; Ruiz López, J.J.; Revilla Calvo, V. Indagine sull’archeologia della morte a Pompei, Necropoli di Porta Sarno. Relazione campagna di scavo. E-J. Scavi Di Pompei 2022, 21, 01.10.24. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio, A. Scavi e scoperte nel suburbio di Pompei. Riv. Studi Pompeiani 1998, 9, 197. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio, A. «Suburbio orientale» Attività della Soprintendenza Archeològica di Pompei. Riv. Studi Pompeiani l’Erma 1999, 10, 180–183. [Google Scholar]

- Di Maio, G.; Stefani, G. Il Tracciato della Circumvesuviana tra Torre Annunziata e Scafati e la Galleria di Boscoreale/Boscotrecase. Progetta, Testi e Coordinamento; Esecuzione Opere Civili: Confer S.C.a.a.L. costituite da Impregilo s.p.a., Pizzarotti s.p.a.; Committente: Ministero dei Trasporti Esercente: Gestione Governativa della Circumvesuviana: Napoli, Italy, 1999; pp. 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Carandini, A. Storie dalla terra. Manuale di Scavo Archeologico; Einaudi: Turin, Italy, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Roskams, S. Interpreting Stratigraphy; Papers Presented to the Interpreting Stratigraphy Conferences 1993–1997; BAR International Series; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2000; p. 910. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, E.C.; Brown, M.R., III; Brown, G.J. Practices of Archaeological Stratigraphy; Academic Press: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Flohr, M. Commerce and Architecture in Late Hellenistic Italy: The Emergence of the Taberna Row. In Shops, Workshops and Urban Economic History in the Roman World; Propylaeum: Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.D.; Marra, F.; Hay, R.L.; Cawood, C.; Winkler, E.M. The judicious selection and preservation of tuff and travertine building stone in ancient Rome. Archaeometry 2005, 47, 485–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Andringa, W.; Duday, H.; Lepetz, S. Mourir à Pompéi, Fouille d’un Quartier Funéraire de la Nécropole Romaine de Porta Nocera (2003–2007); Collection de l’École française de Rome; École Française de Rome: Rome, Italy, 2013; Volume 843, p. 870. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenmeier, P.; Maio, G.; Balassone, G.; Boni, M.; Joachimski, M.; Mondillo, N. The source of stone building materials from the Pompeii archaeological area and its surroundings. Period. Di Mineralogia 2010, 79, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, W. New Guide to Pompeii; Wilhelm Engelmann: Leipzig, Germany, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Tuffreau-Libre, M. Céramiques et usages funéraires. In Mourir à Pompéi, Fouille d’un Quartier Funéraire de la Nécropole Romaine de Porta Nocera (2003–2007); Van Andringa, W., Duday, H., Lepetz, S., Eds.; Collection de l’École française de Rome; École Française de Rome: Rome, Italy, 2013; Volume 144–146, p. 1075. [Google Scholar]

- Van Andringa, W. Archéologie du Geste: Rites et Pratiques à Pompéi; Hermann Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Duday, H.; Van Andriga, W. Des formes et du temps de la mémoire à Pompéi. 3|du Souvenir à l’oubli: Le temps des ossements. Les Nouv. l’Archéologie 2013, 132, 52–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, S.; Alapont, L.M.; Albiach, R. Pompeii: Porta Nola Necropolis Project (Comune di Pompei, Provincia di Napoli, Regione Campania). Pap. Br. Sch. Rome 2017, 85, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, S. Du parfum pour les morts. Formes et usages du mobilier en verre. In Mourir à Pompéi, Fouille d’un Quartier Funéraire de la Nécropole Romaine de Porta Nocera (2003–2007); Van Andringa, W., Duday, H., Lepetz, S., Eds.; Collection de l’École française de Rome; École Française de Rome: Rome, Italy, 2013; pp. 1169–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Marí Casanova, J.J.; Graziani Echávarri, G.J.; Sureda Torres, P.; Llinàs Riera, M. Espejos votivos en plomo de la necrópolis romana de Vía Púnica 34, (Ibiza). In Amicitia. Miscellània d’Estudis en Homenatge a Jordi H. Fernández; Ferrando, C., Costa, B., Eds.; Formentera: Leeds, UK, 2014; pp. 354–367. [Google Scholar]

- Butti, F. Specchi romani tra Comprensorio del Ticino e Comasco. LANX Studi Amici E Colleghi Maria Teresa Grassi 2021, 29, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihajlovic, V.D. Mirrors in the funerary contexts of Moesia Superior: Roman hegemony, beauty and gender? In Beautiful Bodies Gender and Corporeal Aesthetics in the Past; Matić, U., Ed.; Oxbow Books: Barnsley, UK, 2022; pp. 177–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alapont, L.M.; Sastre, M.; Evans, S.F.; Lhériteau, M.; Corredor, P. Ricerche di bioarcheologia e archeologia funeraria. in Via Ostiense. Nuove ricerche sui colombari del Sepolcreto della via Ostiense. Analisi dei resti antropologici e archeologici (Municipio VIII). Bull. Comm. Archeol. Comunale Roma 2021, CXXII, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Alapont, L.M.; Evans, S.F.; Lhériteau, M. Funerary and commemorative practices and rituals in the necropolis of Via Ostiensis in Rome. Bull. Comm. Archeol. Comunale Roma 2022, CXXIII, 337–343. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfante, L. Etruscan Mirrors and the Grave. In L’Écriture et l’Espace De La Mort. Épigraphie et Nécropoles à l’Epoque Préromaine; Haack, M.-L., Ed.; Publications de l’École française de Rome; École française de Rome: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Grummond, N.T. On mutilated mirrors. In Votives, Places and Rituals in Etruscan Religion; Gleba, M., Becker, H., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Németh, G.; Szabó, A. To a beautiful soul: Inscriptions on lead mirrors. Acta Class. Univ. Sci. Debreceniensis 2010, 46, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Van Andringa, W. Coins for the dead and materiality of funerary rituals: Concluding remarks. J. Archæological Numis. 2019, 9, 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Pera, R. La moneta antica come talismano. RItNum 1993, 95, 347–361. [Google Scholar]

- Perassi, C. Monete amuleto e monete talismano. Fonti scritte, indizi, realia per l’età romana. Numis. Antich. Class. 2011, 40, 223–274. [Google Scholar]

- Ceci, F. La deposizione della moneta nella tomba: Continuità di un rito tra paganesimo e cristianesimo. HistriaAnt 2005, 13, 407–416. [Google Scholar]

- Alapont, M.; Evans, S.F.; Lhériteau, M.; Sastre, L. Anthropological and Paleopathological Study of the Cremations of the Via Ostiensis Necropolis in Rome. Bull. Della Comm. Archeol. Comunale Roma 2022, CXXIII, 345–355. [Google Scholar]

- Alapont, L.; Gallello, G.; Martinón-Torres, M.; Osanna, M.; Amoretti, V.; Chenery, S.; Ramacciotti, M.; Jiménez, J.L.; Rubio, Á.M.; Cervera, M.L.; et al. The casts of Pompeii: Post-depositional methodological insights. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listi, G.A.; Manhein, M.H. The use of vertebral osteoarthritis and osteophytosis in age estimation. J. Forensic Sci. 2012, 57, 1537–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, T.D. Rate of development of vertebral osteoarthritis in American whites and its significance in skeletal age identification. Leech 1958, 28, 144–151. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, S.; Terazawa, K. Age estimation from the degree of osteophyte formation of vertebral columns in Japanese. Leg. Med. 2006, 8, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snodgrass, J.J. Sex differences and aging of the vertebral column. J. Forensic Sci. 2004, 49, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Billings, B.K.; Hummel, S.; Grosskopf, B. Evaluating Morphological Methods for Sex Estimation on Isolated Human Skeletal Materials: Comparisons of Accuracies between German and South African Skeletal Collections. Forensic Sci. 2022, 2, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, B.; Santos, F.; Polet, C.; Villotte, S. Secondary sex estimation using morphological traits from the cranium and mandible: Application to two Merovingian populations from Belgium. Bull. Mémoires Société d’Anthropologie Paris 2024, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koortbojian, M. The Double Identity of Roman Portrait Statues: Costumes and Their Symbolims at Rome. In Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture; Edmondson, J.C., Keith, A., Eds.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008; pp. 71–93. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner, D.E.E. Family Ties: Mothers and Sons in Elite and Non-Elite Roman Art. In I Claudia II, Women in Roman Art and Society; Kleiner, D.E.E., Matheson, S.B., Eds.; Yale University Art Gallery: New Haven, CT, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner, D.E.E. Roman Group Portraiture: The Funerary Reliefs of the Late Republic and Early Empire; Garland Publ.: New York, NY, USA, 1977; pp. 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, L.H. The Baker, His Tomb, His Wife, and Her Breadbasket: The Monument of Eurysaces in Rome. Art Bull. 2003, 85, 230–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, S. The Toga: From National to Ceremonial Costume. In The World of Roman Costume. Studies in Classics; Sebesta, J.L., Bonfante, L., Eds.; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1994; pp. 13–45. [Google Scholar]

- George, M. The ‘Dark Side’ of the Toga. In Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture; Edmondson, J.C., Keith, A., Eds.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008; pp. 94–112. [Google Scholar]

- Rothfus, M.A. The Gens Togata: Changing Styles and Changing Identities. Am. J. Philol. 2010, 131, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, N. Roman Footwear. In The World of Roman Costume. Studies in Classics; Sebesta, J.L., Bonfante, L., Eds.; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1994; pp. 125–127. [Google Scholar]

- Stout, A.M. Jewelry as a Symbol of Status in the Roman Empire. In The World of Roman Costume. Studies in Classics; Sebesta, J.L., Bonfante, L., Eds.; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1994; pp. 125–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sebesta, J.L. Symbolism in the Costume of the Roman Woman. In The World of Roman Costume. Studies in Classics; Sebesta, J.L., Bonfante, L., Eds.; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1994; pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fantham, E. Covering the Head at Rome: Ritual and Gender. In Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture; Edmondson, J.C., Keith, A., Eds.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008; pp. 160–170. [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy, S.B. Goddesses, Whores, Wives and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity; Pimlico: London, UK, 1979; p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- Moro Ípola, M. Amuletos de protección infantil y juvenil en el mundo romano: A propósito de algunas de las bullae del Museo Arqueológico Nacional de Madrid. Boletín Del Mus. Arqueol. Nacional 2023, 42, 282. [Google Scholar]

- Oria Segura, M. Sacerdotisas y devotas en la Hispania antigua: Un acercamiento iconográfico. SPAL 2012, 21, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oria Segura, M. De mujeres y sacrificios: Un estudio de visibilidad. SALDVIE 2010, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaeth, B.S. The Roman Goddess Ceres; University of Texas Press: Houston, TX, USA, 1996; pp. 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Meghan, J.; DiLuzio, A. Place at the Altar: Priestesses in Republican Rome; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grether, G. Livia and the Roman Imperial Cult. Am. J. Philol. 1946, LXVII, 222–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boatwright, M.T.; Gargola, D.J.; Lenski, N.; Talbert, R.J.A. A Brief History of the Romans; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, A.A. Livia: First Lady of Imperial Rome; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 2002; p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- Etienne, R. Pompeii: The Day a City Died; Discoveries Series; Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1992; p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Torelli, M. Le Tombe a Schola di Pompei Sepolture “Eroiche” Giulio-Claudie di Tribuni Militum a Populo e Sacerdotes Publicae; Revue archéologique 2020/2; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 325–358. [Google Scholar]

- Torelli, M. Lavinio e Roma. Riti Iniziatici e Matrimonio tra Archeologia e Storia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984; pp. 164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Castrén, P. Ordo Populusque Pompeianus. Polity and Society in Roman Pompeii. Acta Instituti Romani Finlandiae, 8; Bardi: Rome, Italy, 1975; Volume 70–72, p. 231. [Google Scholar]

- Van Andringa, W. “M. Tullius…aedem Fortunae August(ae) solo et peq(unia) sua”: Private foundation and public cult in a Roman colony. In Public and Private in Ancient Mediterranean Law and Religion; Ando, C., Rüpke, J., Eds.; Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche und Vorarbeiten; de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2015; Volume 65, pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, J.B. Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA; Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).