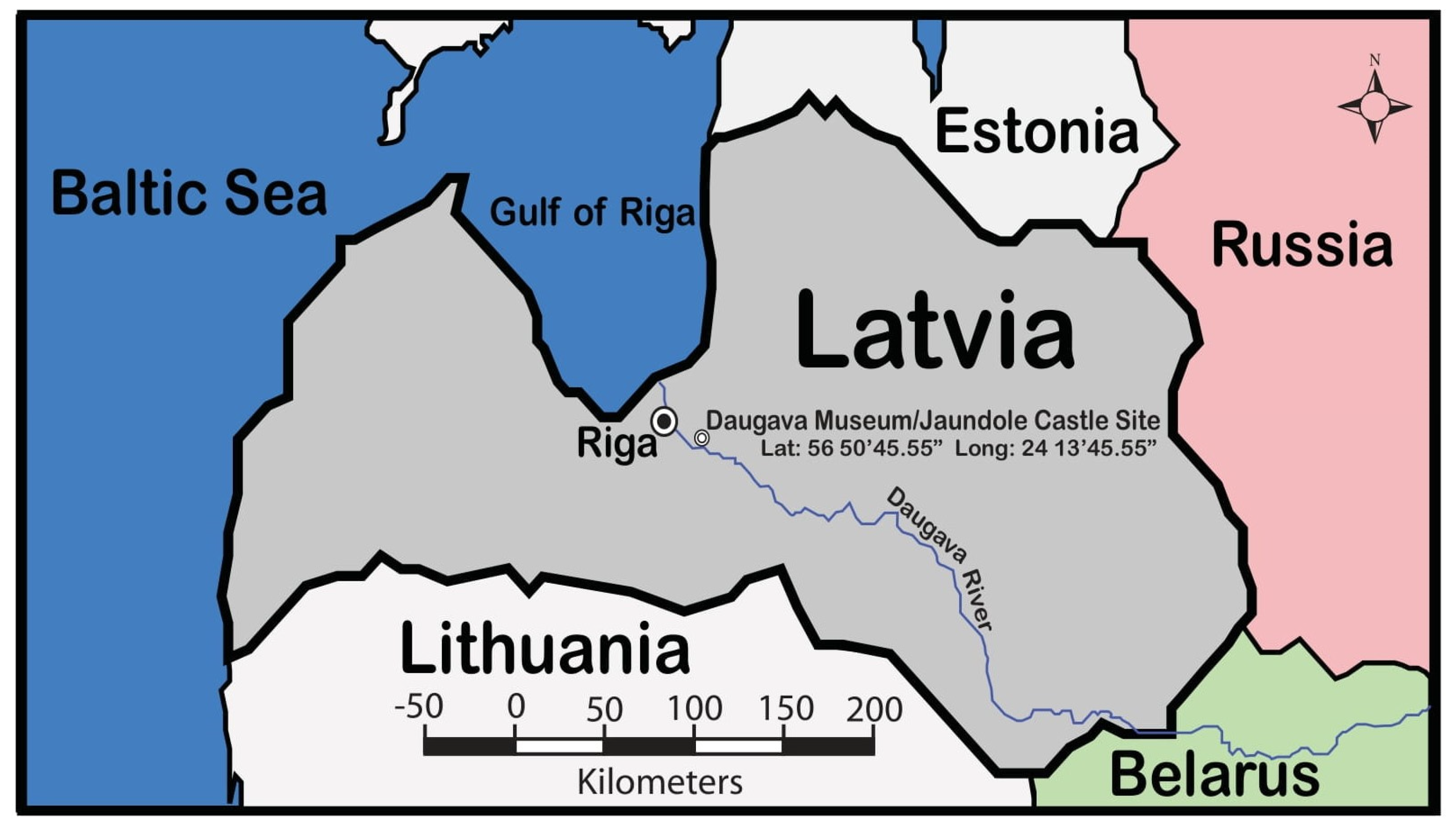

Using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) to Locate the Remains of the Jaundole (New Dahlen) Castle Near Riga, Latvia

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Medieval Historical Background of the Riga Region

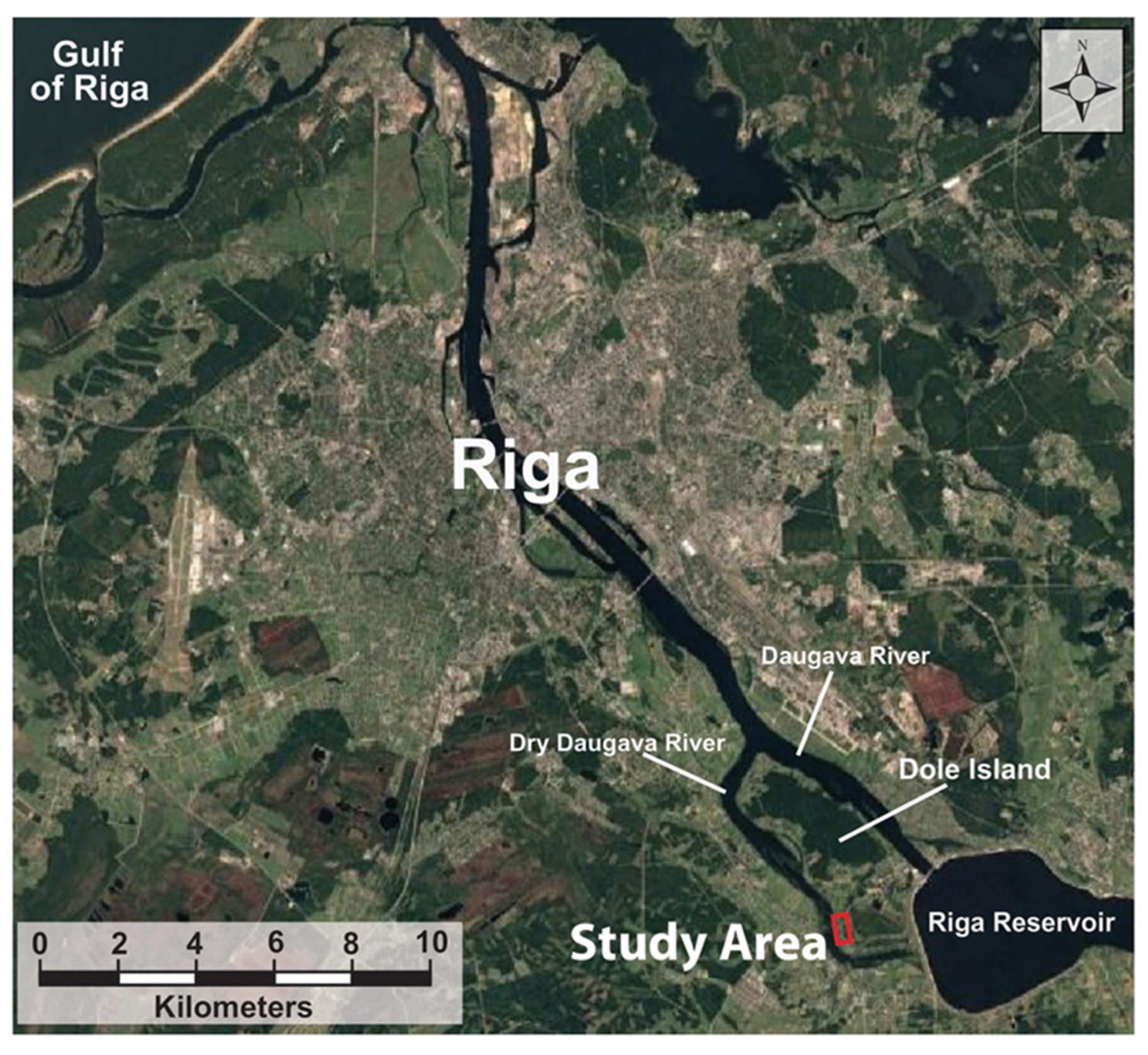

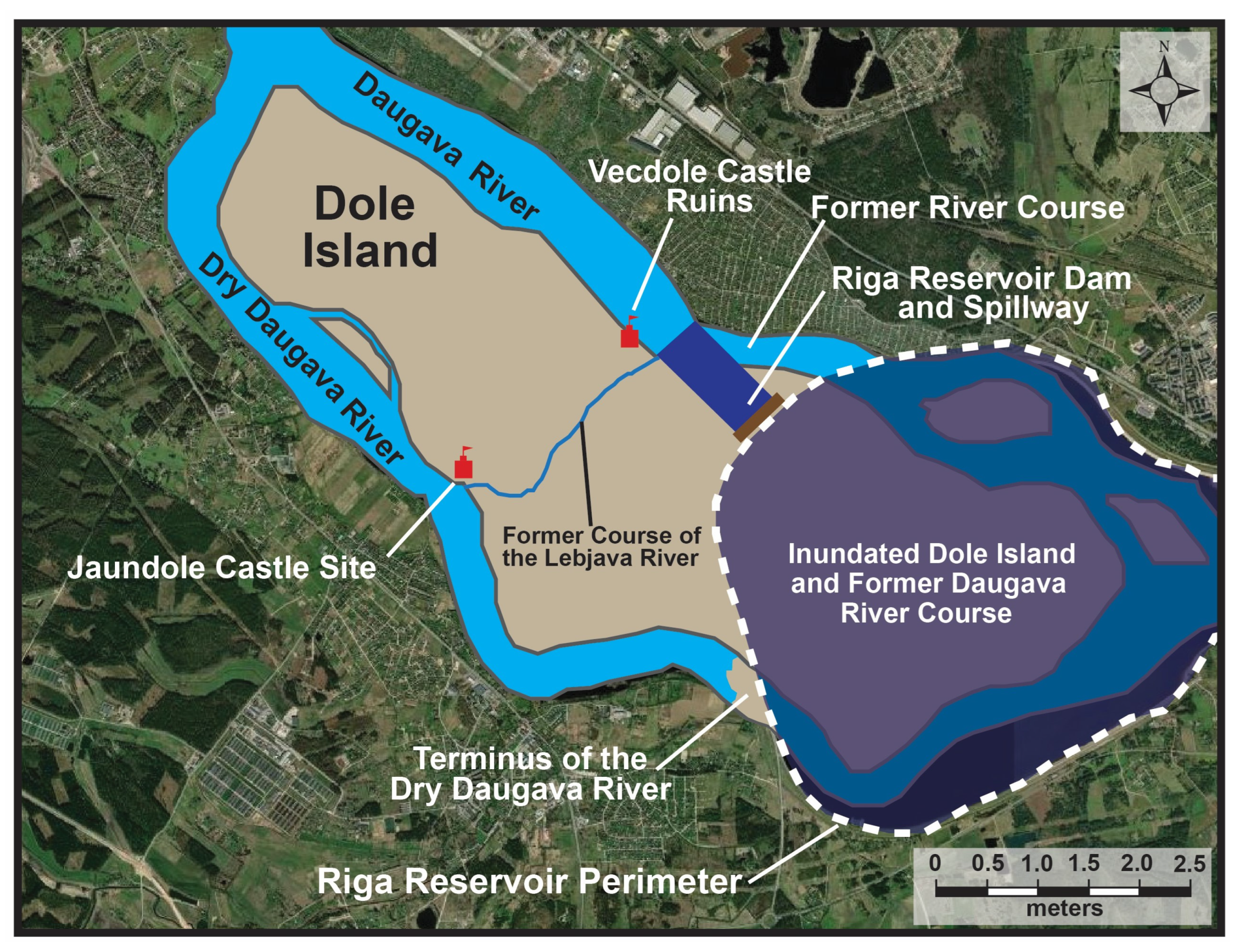

1.2. Dole Island, the Dry Daugava and Daugava Rivers, and Riga Reservoir

2. Historical and Iconographic Description

2.1. Historical Context for Vecdole Castle

2.1.1. Historical Timeline and Related Events for Vecdole Castle (1226 to 1355) [15]

- Castle first mentioned in documents on 15 May 1226.

- On 31 March 1255, Pope Alexander IV confirmed to the Archbishop of Riga, Albert II, in documents held by the Vatican, that the Archbishop had the right to Vecdole Castle on Dole Island.

- Despite the Pope’s decision to award the castle and Dole Island to the Archbishop of Riga, the Dolens unofficially held the castle until 1276.

- In 1276, Archbishop Johann I “officially” returned the castle to the Dolen family; however, Archbishop Johann II in 1288 again took the castle and the island away from the Dolen family and presented ownership to the Dome Chapter.

- In 1297, a war broke out between the Archbishop of Riga, the people of Riga, and the Livonian Order, which led to the eventual destruction of Vecdole Castle, probably in 1298.

- By all accounts, the castle was not rebuilt, and it is last mentioned in documents in 1348 and 1355, when the Archbishop confirmed the rights of possession for Dole Island and the most likely ruined Vecdole Castle to the Dome Chapter, which had taken control in 1288.

- In these 1348 and 1355 documents, the castle is referred to as the first Dole Castle, which indicates that there was already a second Dole Castle on the island.

2.1.2. Historical Interpretations

2.2. Historical Context for Jaundole Castle

2.2.1. Historical Timeline and Related Events for Jaundole Castle (1359 to 1628) [16]

- The Dome Chapter built a second Dole Castle, which was first mentioned in historical documents in 1359.

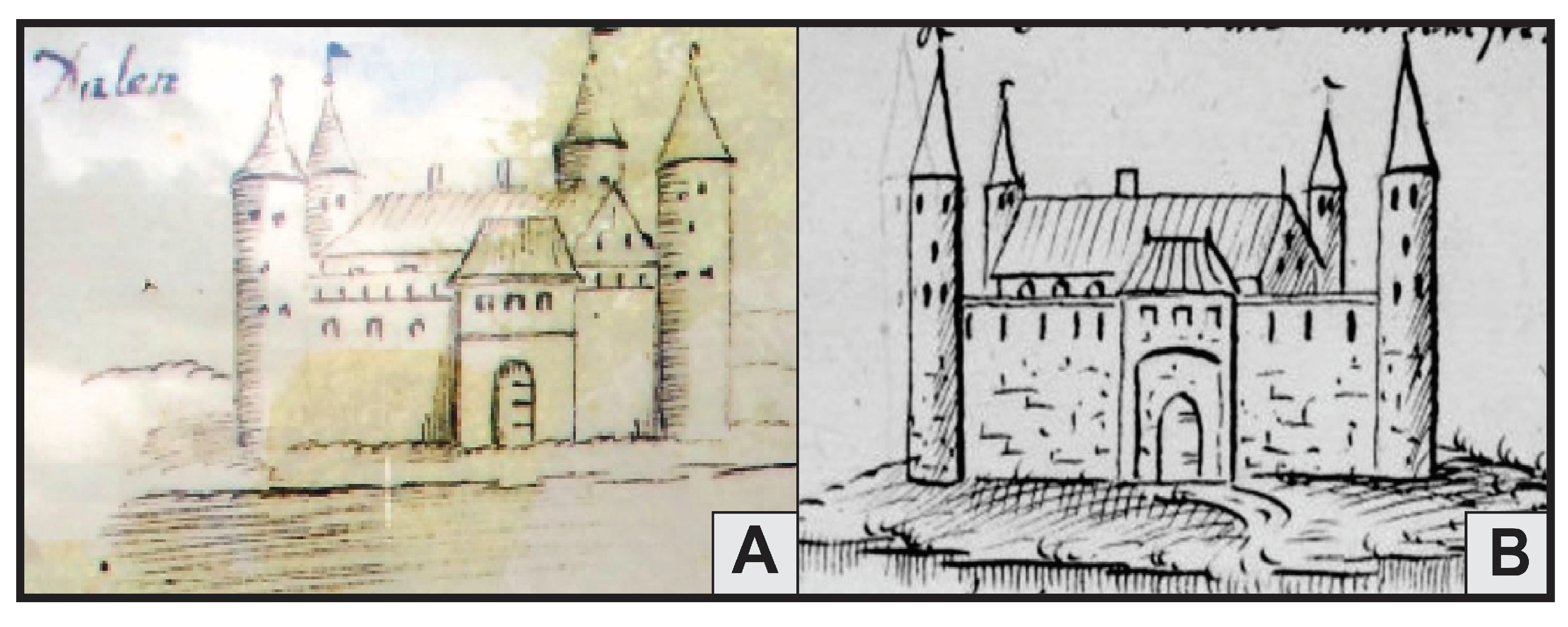

- The new Dole Castle was noted to be minor, with its size estimated to be between 35 × 35 m and 45 × 45 m. On the ground floor was a warehouse for old weapons, a kitchen, and stairs to the second floor, which housed a hall, a small room, and seven rooms for guests. The castle also had a bakery, a brewery, five cellars, a granary, and a small church.

- In 1416, the Dome Chapter gave the castle to the Livonian Order, but in 1449, the Order returned it to the Chapter.

- In 1522, the Archbishop of Riga, Jasper Linde, gave the Dole (Jaundole) Castle to the Provost of the Riga Cathedral Chapter, and in the mid-16th century, the castle served as a refuge for the Archbishop’s servants.

- In 1561, the Livonian states ceased to exist, and in 1566, the control of Dole Island and, hence, Jaundole Castle passed to Poland, becoming a crown estate.

- In 1597, the famous Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe wanted to build an observatory on the island to observe the stars, but he did not receive permission.

- During the Polish–Swedish War in 1621, the Swedes captured the castle and quickly restored and modernized its fortifications.

- In 1627, the Poles captured the castle, and while retreating in 1628, they blew it up so that it would not fall back into the hands of the Swedes [16].

2.2.2. Iconographic Depictions Related to Jaundole Castle (1359 to 1628)

2.2.3. Historical Timeline and Related Events for Jaundole Castle (1628 to 1839) [16]

- After its destruction in 1627, the castle was no longer used as a military fortification, and over the years, the ruins were eventually covered with earth and practically disappeared.

- In 1631, the first manor estate, whose owner was a Swedish army officer, was established on Dole Island within two km of the Jaundole and Vecdole Castle sites.

- After the Great Northern War, which ended in 1721, possession of the manor estate changed hands many times.

- Already in the 18th century, almost nothing remained of the castle walls.

- In the 19th century, as depicted in an 1830 painting, the remains of Jaundole Castle were still visible on the land surface (Figure 6).

- In 1839, the Livonian Charitable and Economic Society published a map of Dole Island (Figure 7).

2.2.4. Iconographic Depictions Related to Jaundole Castle (1628 to 1839)

2.2.5. Historical Timeline and Related Events for Jaundole Castle (1898 to 2024)

- In 1957, Latvian archaeologist Andris Caune drew a plan of the remains of the walls of Jaundole Castle.

- In 1977, the Daugava Museum, which is located in the 1898 Dole Manor House, opened to the public [18].

- In 2024, a research team from Duquesne University and the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire completed data collection using GPR to find the location of the buried remains of Jaundole Castle.

2.2.6. Historical Interpretations (1631 to 2024)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodological Background

3.2. GPR Methodology

4. GPR Results and Data Interpretation

5. Discussion

6. Summary and Conclusions

- (1)

- Identify the likely location, layout, and function of Jaundole Castle through historical sources.

- Two drawings of Jaundole Castle were found that indicate that the castle’s shape was square, with towers at each corner topped by a spire.

- A 1627 map exists on the Castles of Latvia (Jaundole Castle) website [16] that depicts the northern portion of Dole (Dahlen) Island and shows that Jaundole Castle was located at the confluence of the Lebjava and Dry Daugava Rivers. This map contains the inscription “has been blown up, but the fortifications are still there”, indicating that it was destroyed in 1627 or before.

- In a painting by A. Merkela from 1830 (see Figure 6), the ruins of Jaundole Castle can still be seen, with fertile farmland, associated with the main economic function of the castle, depicted across the Dry Daugava River.

- A small area containing the ruins of the castle could still be seen on the land surface in 1957.

- (2)

- Evaluate the effectiveness of ground-penetrating radar (GPR) for detecting its buried remains.

- GPR detected numerous reflection patterns in the subsurface within the five grids (see Figure 12), with the greatest concentration in grid 1.

- On average, the penetration depth in the five grids analyzed in 2024 was 2.5 m, with structural features related to the castle that are buried beneath the contemporary landscape detectable down to depths of at least 2 m.

- (3)

- Determine whether structural elements can be interpreted from GPR data to support future archaeological excavations.

- The reflection patterns present within the GPR grids, with grid 1 containing the most reflections, are linear, probably indicating buried Jaundole Castle wall locations, and, to varying degrees, circular, indicating rubble piles or other human-constructed features.

- Based on these discoveries, possible test excavation locations were provided to the director of the Daugava Museum and the stewards of the property, and it is probable that test excavations will verify that the GPR data reflection patterns and associated features in the cross-sections are associated with the remains of Jaundole Castle.

- In that case, additional GPR data will be collected to assist with the development of full-scale excavation targets, but no timeline has yet been developed for these excavations.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Medieval Castles of Latvia. Castles of Riga’s Bishop and Capital of Dome. 2025. Available online: https://www.castle.lv/castles4/episkop-eng.html (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Medieval Castles of Latvia. Information About Castles of Different Countries, History, Architecture of Different Eras, etc. 2025. Available online: https://www.castle.lv/lv-title.html (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Lettus, H. The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia, Trans. with New Introduction; Brundage, J.A., Ed.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; p. 262. [Google Scholar]

- Livonas.net. The Livonians in Ancient Times. UL Livonian Institute. 2025. Available online: http://www.livones.net/en/vesture/the-livonians-in-ancient-times (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Mihm, R. The Livonia Crusade Told Through Henry of Livonia’s Chronical. 2024. Available online: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/0856849a87214481b8e7976f552dc399 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Membership of the Teutonic Order. The Order of the Teutonic Knights of St. Mary’s Hospital in Jerusalem–1190. 2025. Available online: https://www.imperialteutonicorder.com/id62.html (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Arnold, U. Eight Hundred Years of the Teutonic Order. In The Military Orders Volume I, 1st ed.; Barber, M., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; p. 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Postgrad Chronicles. European Medieval History from the Viking Age to the Hundred Years’ War. Crusaders on the Baltic Shore–The Livonian & Estonian Crusades (c. 1198–1290). 2025. Available online: https://thepostgradchronicles.org/2017/08/03/crusaders-on-the-baltic-shore-the-livonian-estonian-crusades-c-1198-1290/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Sandomirskii, G.V. Construction of the Riga hydroelectric station. Hydrotech. Constr. 1974, 8, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitalija, Z.; Markots, A. Deglaciation History of Latvia; Developments in Quaternary Science: Riga, Latvia, 2004; Volume 2, pp. 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasks, A. The Lower Reaches of the Daugava River in the Bronze Age, and the Earliest Iron Age (1800–500 to the 1st Century BC). Archaeol. Balt. 2021, 28, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svabe, A. The Story of Latvia—A Historical Survey; Latvian National Foundation: Stockholm, Sweden, 1949; Available online: https://latvians.com/index.php?en/CFBH/TheStoryOfLatvia/SoLatvia-01-chap.ssi (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Brundage, J. The Thirteenth-Century Livonian Crusade: Henricus de Lettus and the First Legatine Mission of Bishop William of Modena. Jahrbücher Für Gesch. Osteur. 1972, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gummarssone, A.; Oras, E.; Talbot, H.; Ilves, K.; Legzdins, D. Cooking for the Living, and the Dead: Lipid analyses of Rauši Settlement and Cemetery Pottery from the 11th-12th Century. Est. J. Archaeol. 2020, 24, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medieval Castles of Latvia. Dole or Vecdole Castle (Alt-Dahlen). 2025. Available online: https://www.castle.lv/latvija/vecdole.html (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Medieval Castles of Latvia. Dole or Jaundole Castle (Dahlen). 2025. Available online: https://www.castle.lv/latvija/jaundole.html (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Zarāns, A. Latvijas pilis un muižas. In Castles and Manors of Latvia; Zarāns, A., Ed.; Latvia, 2006; p. 319. [Google Scholar]

- Daugava Museum. 2025. Available online: https://www.daugavasmuzejs.lv/en/par-muzeju-en (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Sterns, I. Latvijas vēsture 1290-1500; Daugava: Riga, Latvia, 1997; p. 740. [Google Scholar]

- University of Latvia. Collection of Johann Christoph Brotze, Johana Kristofa Broces kolekcija/Collection of Johann Christoph Brotze. Sammlung Verschiedener Liefländischer Monumente, Prospect, Wapen, etc. 1776–1818; University of Latvia Academic Library: Riga, Latvia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Taimina, A. 500 Years of Latvian Books: Johann Christoph Brotze and His Meticulous Book Collection. LSM+. 2024. Available online: https://eng.lsm.lv/article/culture/literature/18.06.2024-500-years-of-latvian-books-johann-christoph-brotze-and-his-meticulous-book-collection.a558447/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Helms, J. Alvin: Platform for Digital Collections and Digitized Cultural Heritage. Appendix. 2025. Available online: https://www.alvin-portal.org/alvin/attachment/document/alvin-record:12516/ATTACHMENT-0001.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Library of Congress, Atlas of Liefland. 2025. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/75572471/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Jürjo, I. Ludwig August krahv Mellin kui talurahva sõber ja estofiil. Dokument Ja Kommentaar. Tuna 2003. Available online: https://www.ra.ee/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/JyrjoIndrek_Ludwig_August_TUNA2003_4-1.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Taimina, A. 500 Years of Latvian Books: The Hartknochs, Father-and-Son Enlightenment Publishers, LSM+. 2024. Available online: https://eng.lsm.lv/article/culture/literature/09.06.2024-500-years-of-latvian-books-the-hartknochs-father-and-son-enlightenment-publishers.a556570/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Jeske, M. The map Specialcharte von Livland: Georg Friedrich Parrot’s agenda or a new perspective on Livland. Acta Balt. Hist. Et Philos. Sci. 2018, 6, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, F.; Podd, F.; Solla, M. From Its Core to the Niche: Insights from GPR Applications. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Lai, W.; Chang, R.; Goodman, D. GPR imaging criteria. J. Appl. Geophys. 2019, 165, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conyers, L. Analysis, and interpretation of GPR datasets for integrated archaeological mapping. Near Surf. Geophys. 2015, 13, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Forte, E.; Pipan, M.; Tian, G. Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) attribute analysis for archaeological prospection. J. Appl. Geophys. 2013, 97, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manataki, M.; Vafidis, A.; Sarris, A. GPR Data Interpretation Approaches in Archaeological Prospection. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jol, H.; Bristow, C. An Introduction to Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) in Sediments; Geological Society: Special Publications, London, 2003; Volume 211, p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jol, C.; Jol, H.; Dettinger, M.; Singleton, K.; Freund, R.; Reeder, P.; Miazga, C.; Bauman, P.; Wiley, P.; Lensky, I.; et al. Subsurface Imaging of a Holocaust Mass Burial Site: Jungfernhof Concentration Camp, Riga, Latvia. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Ground Penetrating Radar, Golden, CO, USA, 12–17 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jol, H.M. Ground penetrating radar antennae frequencies and transmitter powers compared for penetration depth, resolution, and reflection continuity. Geophys. Prospecting. 1995, 43, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) Theory and Applications; Jol, H.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; 524p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.; Jol, H.; Uchyti1, G.; Hall, N.; Freund, R.; Bauman, P.; McClymont, A.; Miazga, C.; Reeder, P.; Konik, J.; et al. Searching for The Ringleblum Archives: Documentation of Life During the Holocaust-A Ground Penetrating Radar Investigation of Krasinskich Park, Warsaw, Poland. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Ground Penetrating Radar, Golden CO, USA, 12–17 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, N.; Jol, H.; Fischer, A.; Uchytil1, G.; Freund, R.; Bauman, P.; McClymont, A.; Miazga, C.; Reeder, P.; Konik, J.; et al. Holocaust Archaeology: GPR Subsurface Imaging of the Mila 18 Memorial in Warsaw, Poland. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Ground Penetrating Radar, Golden, CO, USA, 12–17 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchytil, G.; Jol, H.; Fischer, A.; Hall, N.; Freund, R.; Bauman, P.; McClymont, A.; Miazga, C.; Reeder, P.; Konik, J.; et al. Archaeological GPR investigation of the Bersohn and Bauman Jewish Children’s Hospital in Warsaw, Poland: Locating potential Holocaust artifacts. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Ground Penetrating Radar, Golden, CO, USA, 12–17 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Jol, H.M. Ground penetrating radar: Antenna frequencies and maximum probable depths of penetration in Quaternary sediments. J. Appl. Geophysics. 1995, 33, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensors and Software, Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) Solutions. 2025. Available online: https://www.sensoft.ca/ (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- EKKO_Project™ GPR Software; Sensors and Software: Mississauga, ON, Canada, 2025. Available online: https://www.sensoft.ca/products/ekko-project/overview/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Economou, N.; Bano, M.; Ortega-Ramirez, J. Delineation of Fractures Using a 2D GPR Processing Strategy for 3D Imaging: Weak Zones within Carbonates at the Archaeological Site of Xochicalco in Mexico. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzarone, P.; Bigman, D. Processing considerations and improved interpretation for ground-penetrating radar imaging of a relict archaeological excavation unit. Near Surf. Geophys. 2018, 16, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angeli, S.; Serpetti, M.; Battistin, F. A Newly Developed Tool for the Post-Processing of GPR Time-Slices in A GIS Environment. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böniger, U.; Tronicke, J. Improving the interpretability of 3D GPR data using target–specific attributes: Application to tomb detection. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2010, 37, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A. Ground-penetrating radar, and its use in sedimentology: Principles, problems, and progress. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2004, 66, 261–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Roberts, C. Applications of Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR) to Sedimentological, Geomorphological and Geoarchaeological Studies in Coastal Environments; Geological Society of London, Special Publications; Pye, K., Allen, J., Eds.; Coastal and Estuarine Environments: Sedimentology, Geomorphology and Geoarchaeology: London, UK, 2000; Volume 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Wai-Lok Lai, W. Unified optimization-based analysis of GPR hyperbolic fitting models. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 146, 105633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Q.; Wei, L.; Magee, D.; Cohn, A. Real-Time Hyperbola Recognition and Fitting in GPR Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, D. GPR Methods for Archaeology. Seeing the Unseen: Geophysics and Landscape Archaeology, 1st ed.; Campana, S., Piro, S., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; p. 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, W. GIS in Archaeology—The Interface Between Prospection and Excavation. In Archaeological Prospection; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, S. War and Peace in the Baltic, 1560-1790; Routledge: London, UK, 1992; p. 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldagodi, S.; Orlando, S.; Piro, S.; Rosso, F. Location of Archaeological Structures using GPR Method: Three-dimensional Data Acquisition and Radar Signal Processing. Archaeol. Prospect. 1996, 3, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capstick, L. TEDx Mile High, Individually Devised Ted Event. Hidden History: Three People Who Rose in the Past. 2020. Available online: https://www.tedxmilehigh.com/hidden-history/ (accessed on 23 March 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reeder, P.; Jol, H. Using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) to Locate the Remains of the Jaundole (New Dahlen) Castle Near Riga, Latvia. Heritage 2025, 8, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8050161

Reeder P, Jol H. Using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) to Locate the Remains of the Jaundole (New Dahlen) Castle Near Riga, Latvia. Heritage. 2025; 8(5):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8050161

Chicago/Turabian StyleReeder, Philip, and Harry Jol. 2025. "Using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) to Locate the Remains of the Jaundole (New Dahlen) Castle Near Riga, Latvia" Heritage 8, no. 5: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8050161

APA StyleReeder, P., & Jol, H. (2025). Using Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) to Locate the Remains of the Jaundole (New Dahlen) Castle Near Riga, Latvia. Heritage, 8(5), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8050161