Sasak Cultural Resilience: A Case for Lombok (Indonesia) Earthquake in 2018

Abstract

1. Introduction

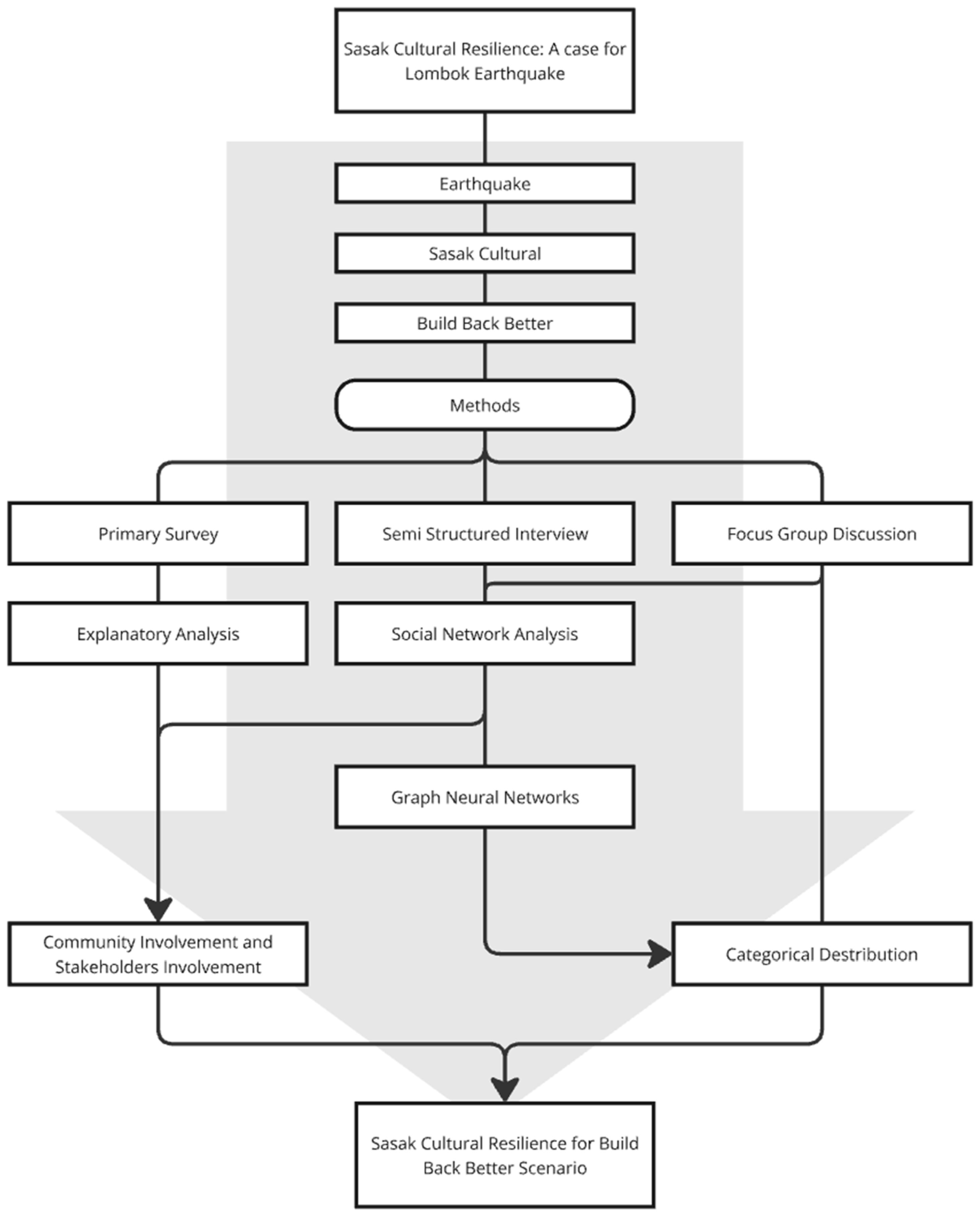

2. Methodology

2.1. Explanatory Analysis

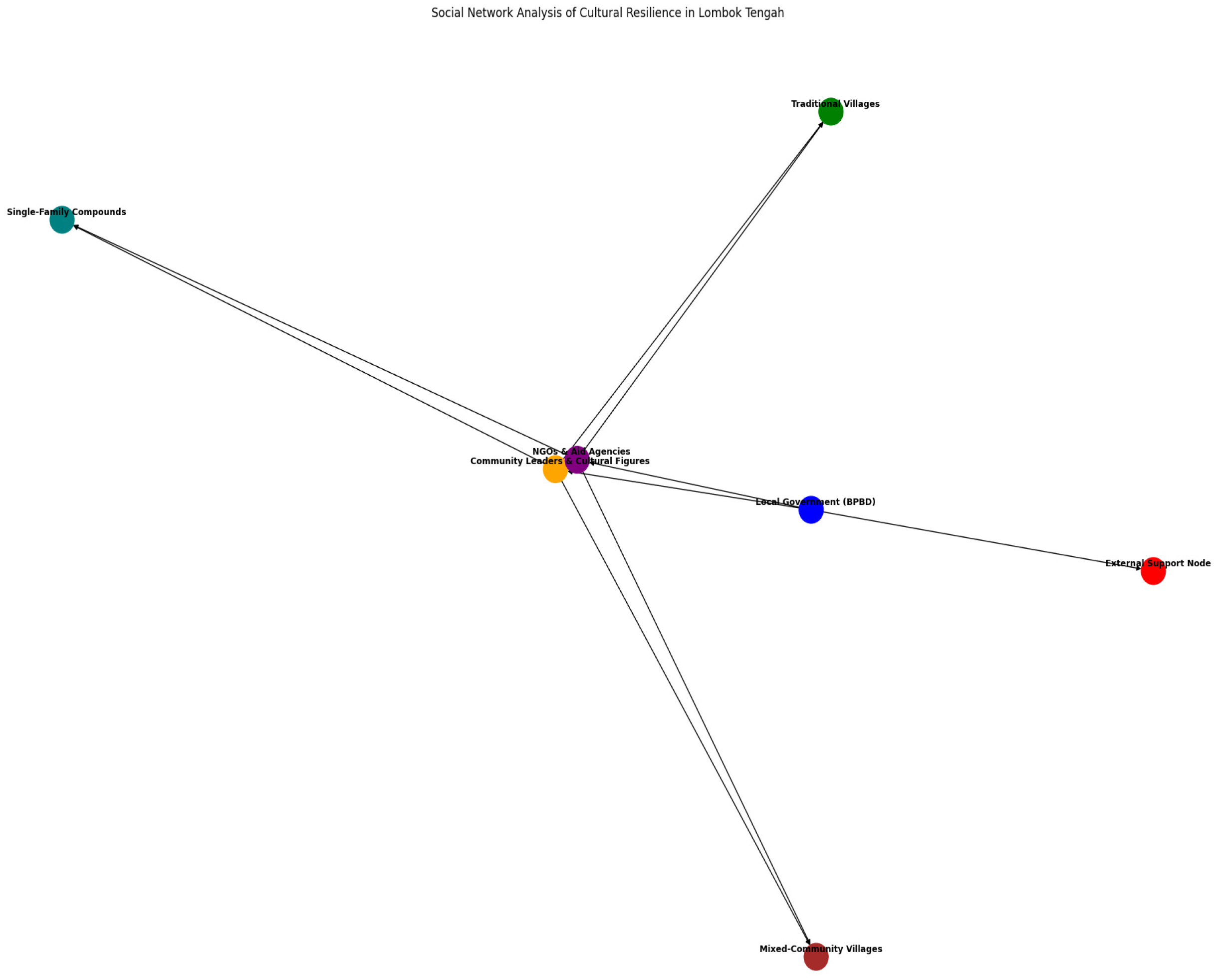

2.2. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

2.3. Categorical Distribution

3. Data and Study Area

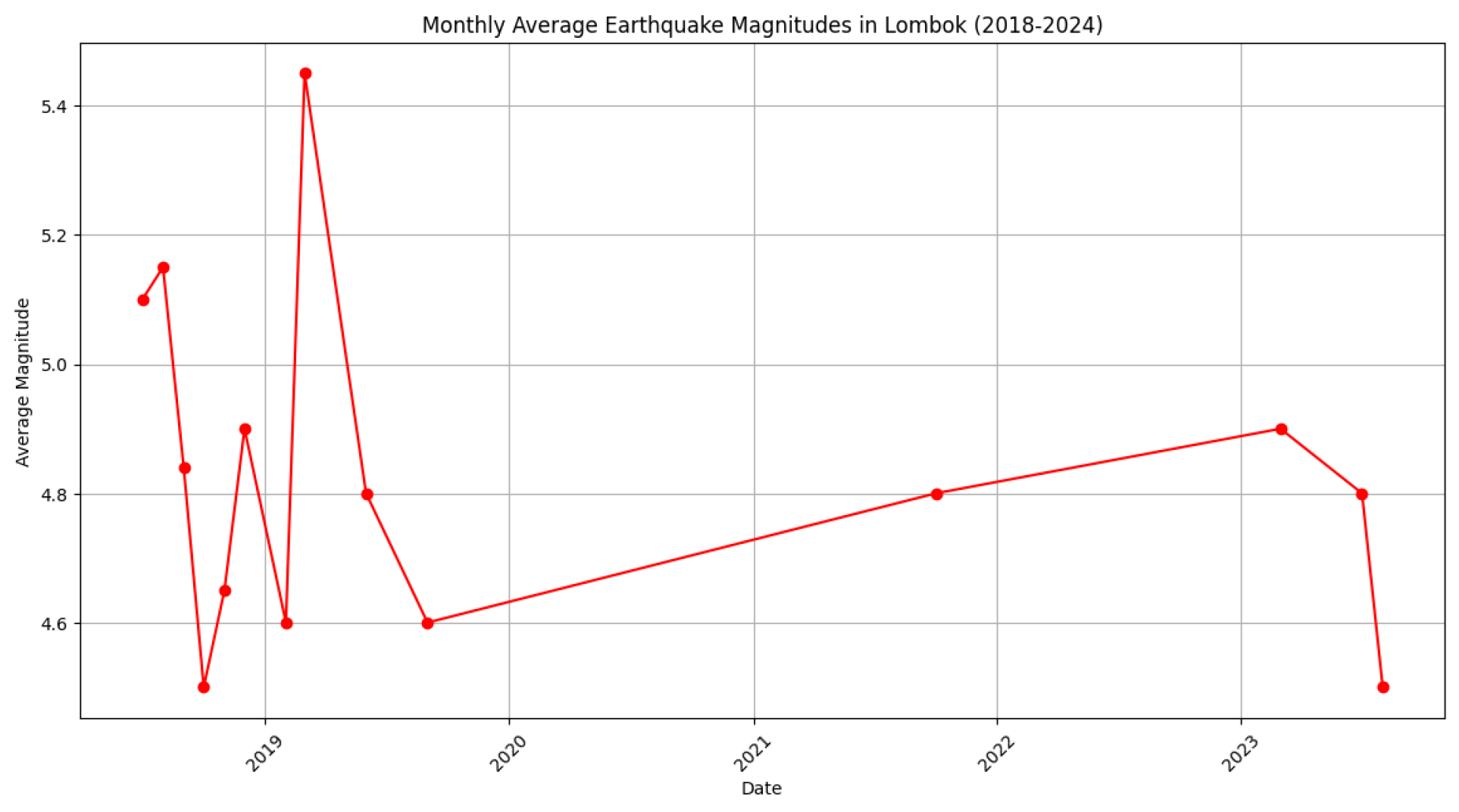

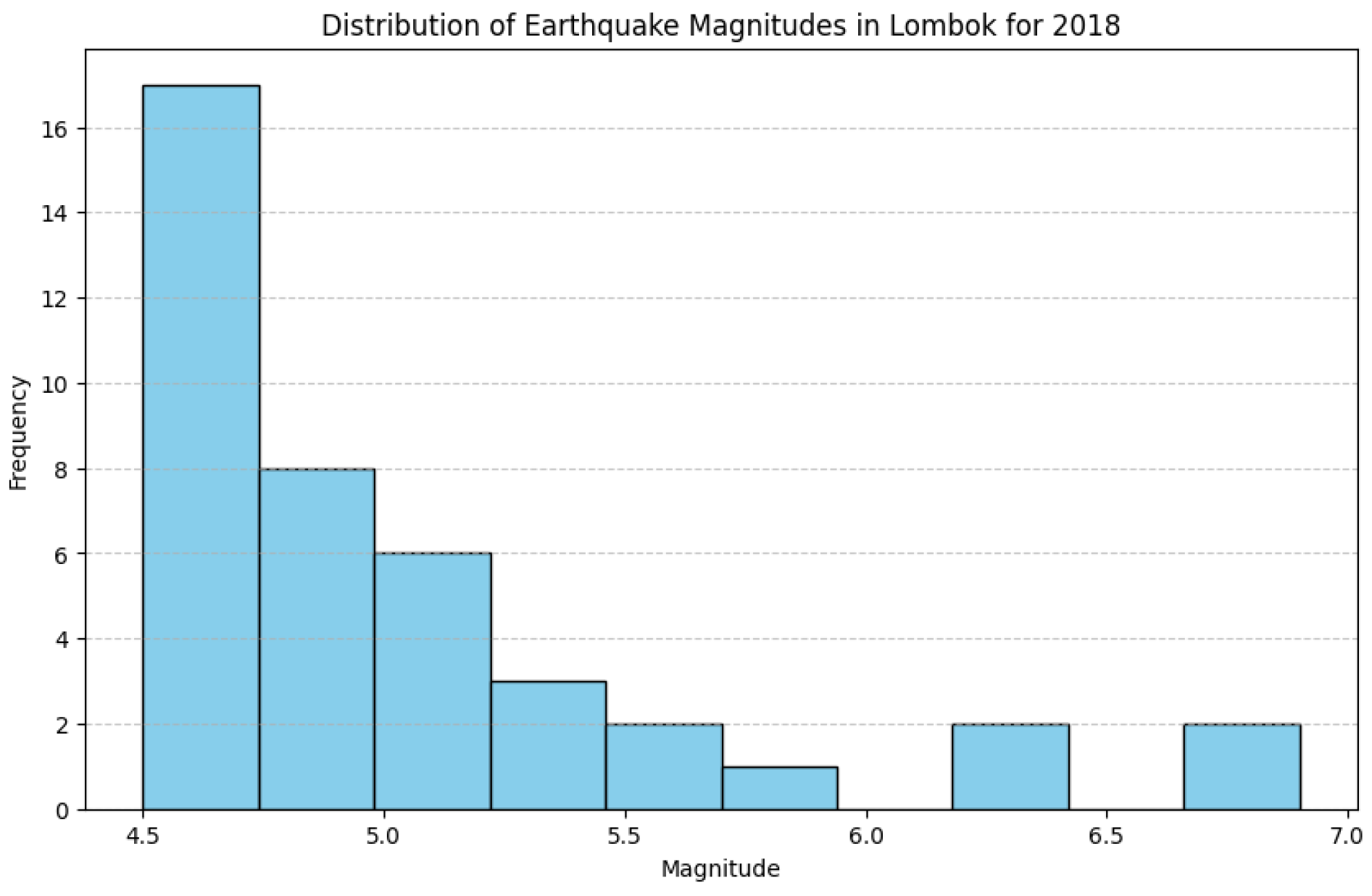

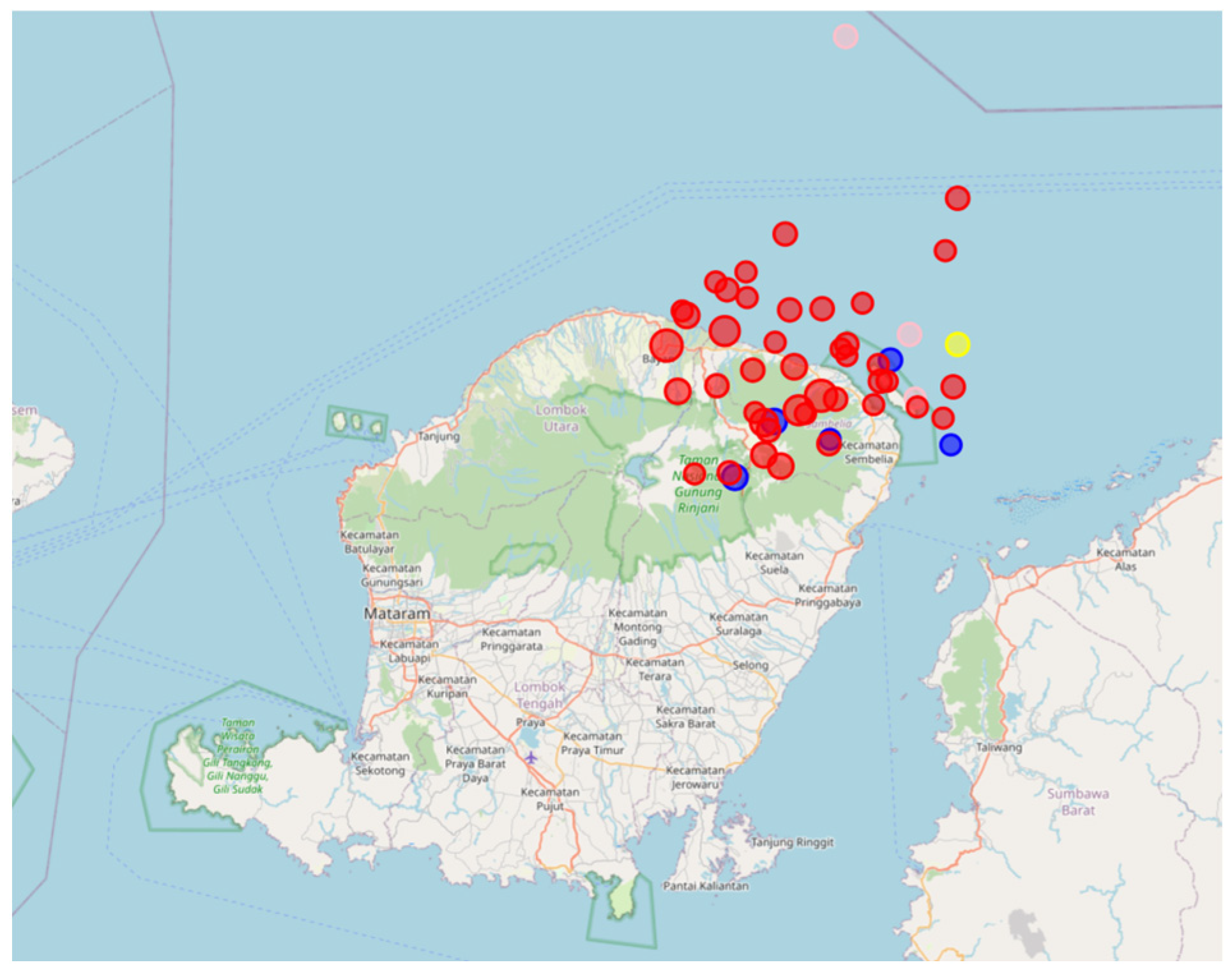

3.1. Lombok Earthquake 2018

3.2. Sasak Cultural Resilience

3.2.1. Traditional Architecture and Building Materials

- Bamboo: Lightweight and flexible, bamboo allows structures to absorb and dissipate seismic energy, reducing the likelihood of collapse. Bamboo’s natural flexibility means it can sway without breaking, making it an ideal material in earthquake-prone areas.

- Alang-alang roofs: These roofs are lightweight, which minimizes the load on the house’s structural frame, further reducing the risk of collapse during an earthquake. The structure of alang-alang also allows for natural ventilation, making homes cooler while maintaining structural stability.

- Low-rise design: Sasak houses are often one-story buildings, which are inherently more stable in earthquakes. The low height keeps the center of gravity close to the ground, reducing the impact of lateral (side-to-side) shaking.

3.2.2. Community Cohesion and Gotong Royong

- Setting up temporary shelters: Villagers worked together to build makeshift homes in safe areas, often using available materials. This was done with remarkable speed and efficiency, highlighting the community’s preparedness and their readiness to mobilize resources and manpower.

- Community kitchens and shared resources: They set up community kitchens to ensure everyone, especially those most vulnerable, had access to meals. This pooling of resources ensures that no one is left without support, especially during the critical early stages of disaster recovery.

3.2.3. Cultural Practices and Rituals

4. Results

4.1. Impact of the 2018 Lombok Earthquake

4.2. Community Involvement in Rebuilding

“Gotong Royong helps in the repair of houses from families, neighbours and the community, the local government also participates in helping and volunteers who want to come to help”—Disasters Local Agency (BPBD) Lombok Tengah

4.3. Resilience of Traditional Sasak Villages

“Houses in Sade and Ende Traditional Villages are built using local materials, such as bamboo and reeds. The low and wide design of the houses can help reduce the impact of earthquakes”—Culture Chief of Sade Village

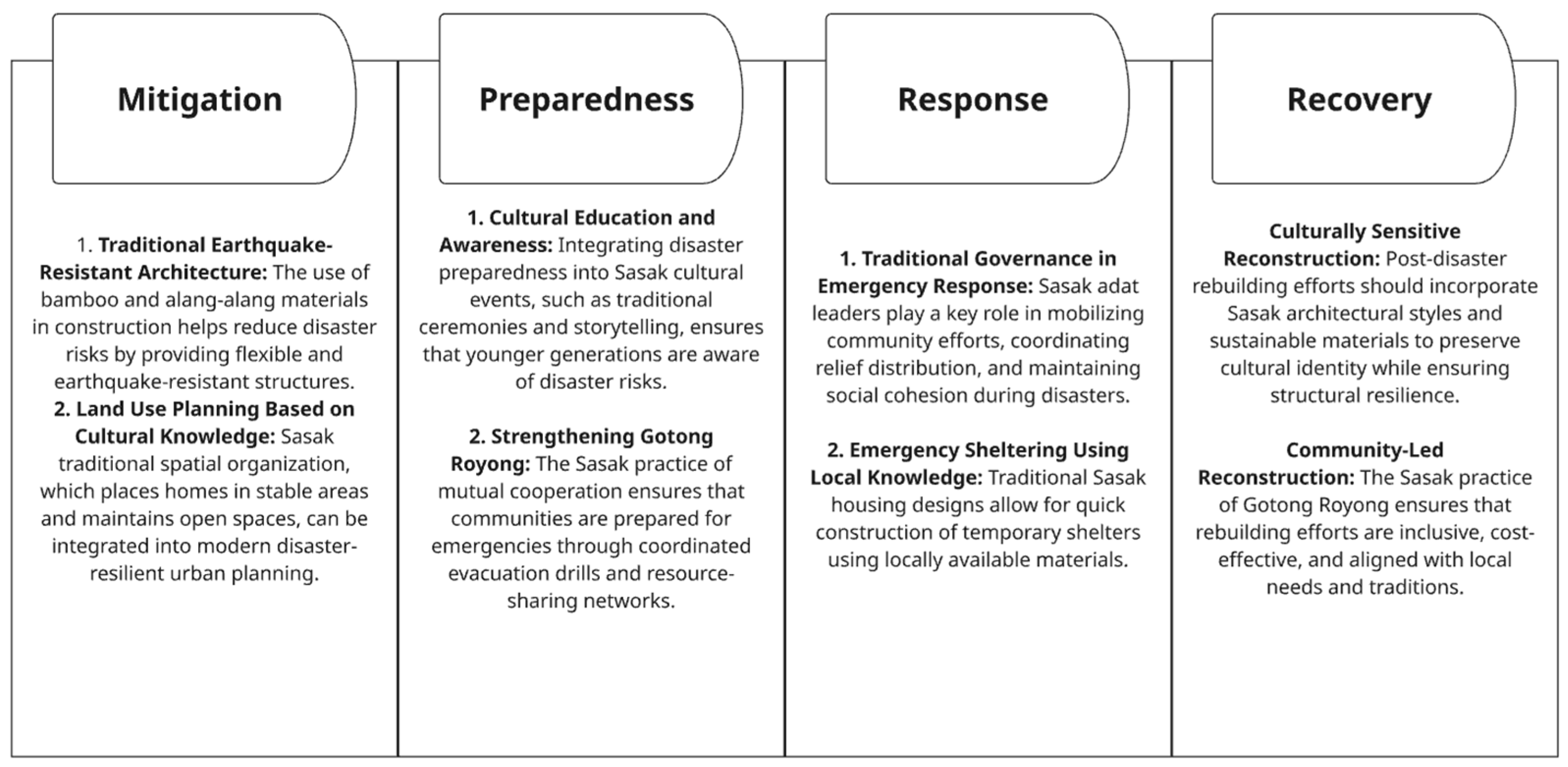

4.4. Reconstruction Model for Earthquake Cultural Resilience

“The government carried out post-earthquake recovery in house repairs by organising coaching activities for community groups (pokmas) as supervision in the construction of houses for affected communities. there are Facilitators (cross-village: trained and trained, there are applicators)”—Local Planning and Research Agency (BAPPERIDA) Lombok Tengah

“The community becomes the supervisor in the construction of each house. With funds already available, the community will be involved through the Pokmas (Community Group) contract mechanism. This gives the community the opportunity to choose and oversee the building process, as well as ensure that the construction of the houses is carried out in accordance with the set standards”—Local Infrastructure Agency (PUPR)—Lombok Tengah

4.5. Cultural Resilience

“Public facilities were repaired by the local, provincial and central government as well as other assets and assisted by the community in the spirit of gotong royong (mutual cooperation).”—Disasters Local Agency (BPBD) Lombok Tengah

4.6. Actor Involvement

“Infrastructure improvements were carried out for approximately 2 years”—Local Infrastructure Agency (PUPR)—Lombok Tengah

“National Disasters Agency (BNPB) determines the funds, namely with severe damage levels of 50 million, medium 25 million, light 10 million. The mechanism of work is from Pokmas (community groups) of affected communities. Supervising the construction of houses, there are facilitators from the civilian army and police and PUPR who oversee”—Local Disasters Agency (BPBD) Lombok Tengah

5. Discussion

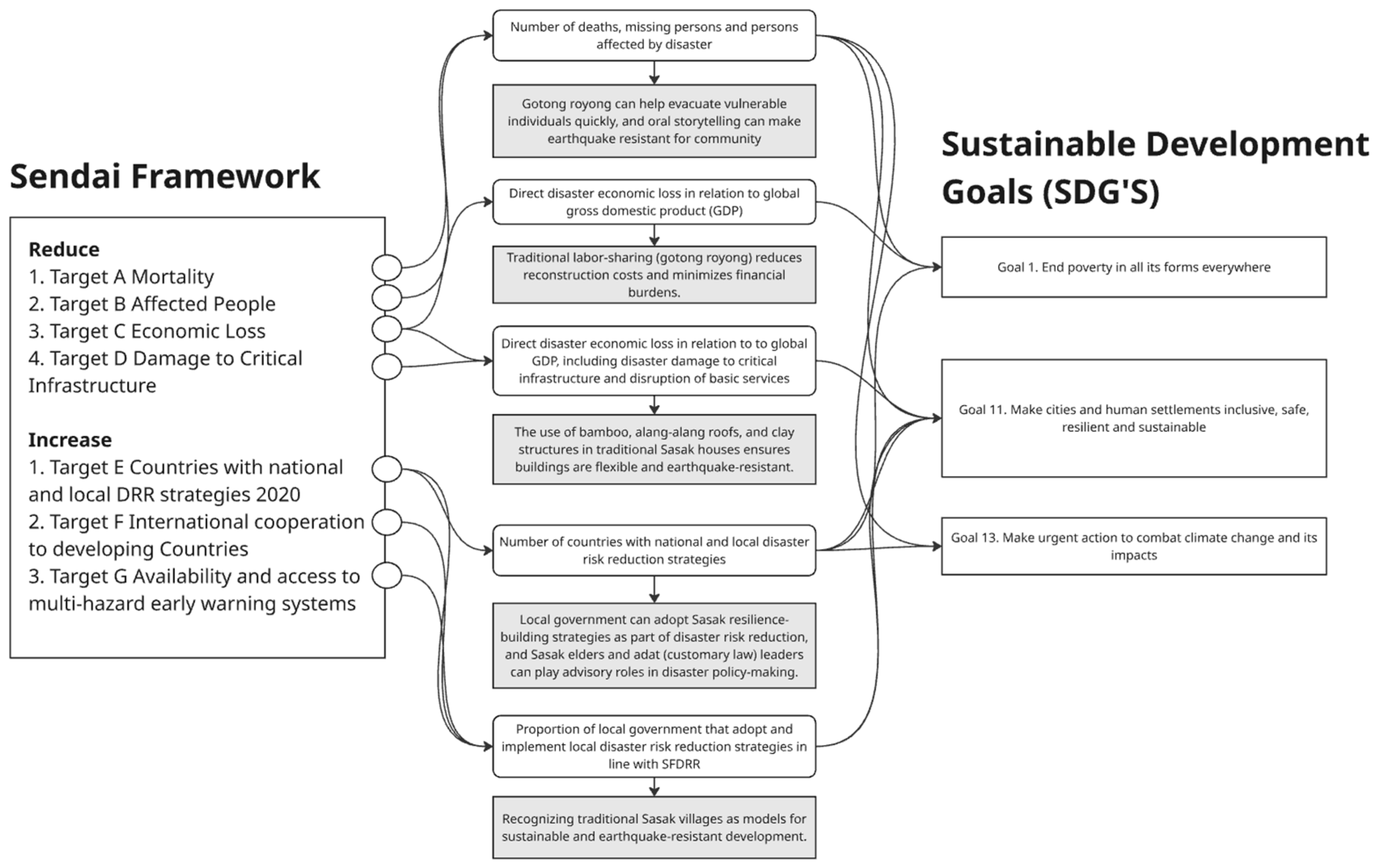

5.1. Integrating Local Knowledge into Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR)

5.2. Bridging Traditional and Modern Resilience Strategies

5.3. Formalizing Cultural Resilience in National Disaster Policies

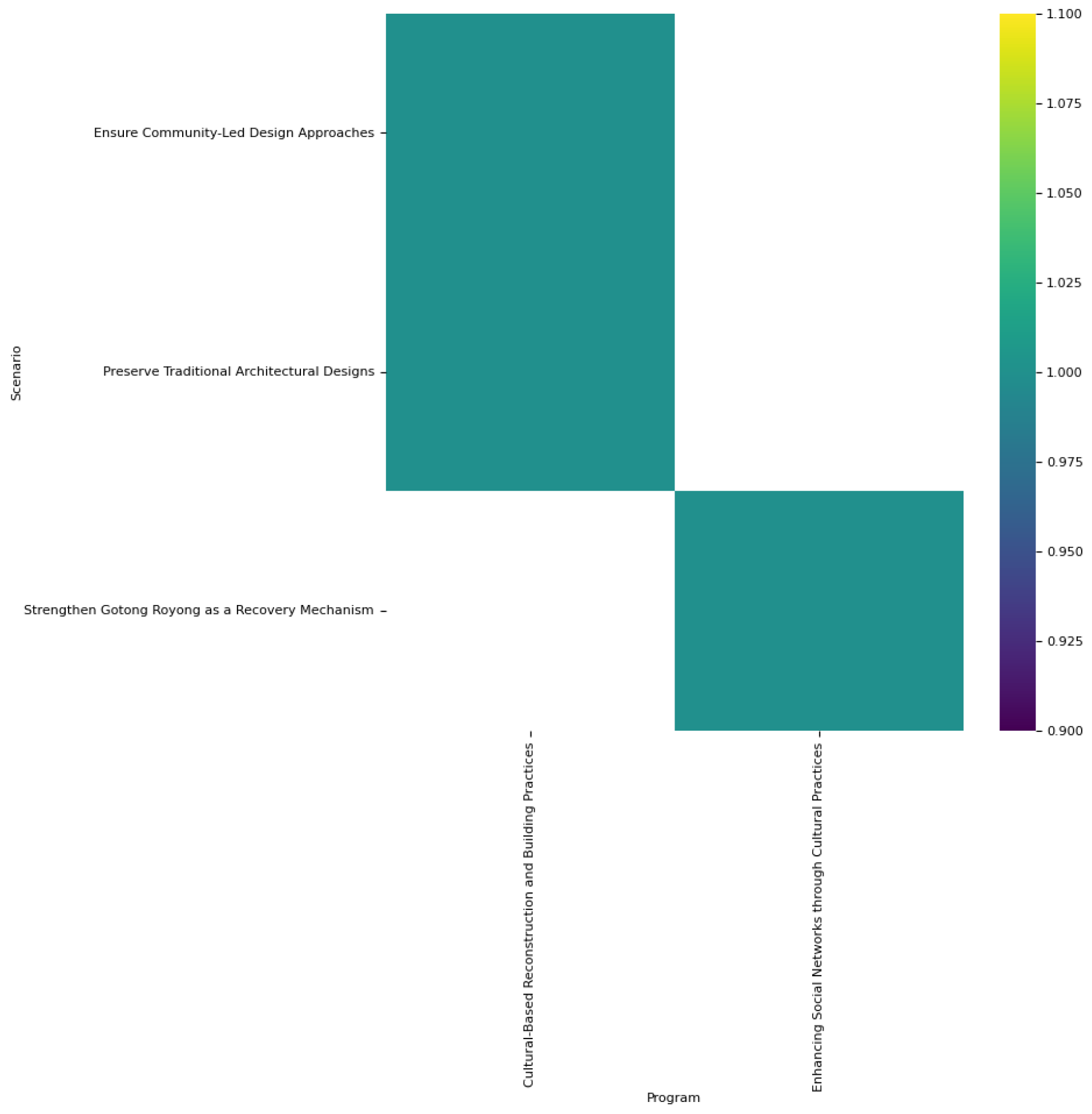

5.4. Sasak Cultural for Build Back Better Scenario

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AHA Centre. AHA-Situation_Update_no_5_M-7.0-Lombok-Earthquake. 2018. Available online: https://ahacentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/AHA-Situation_Update_no_5_M-7.0-Lombok-Earthquake-final.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Dayaratne, R. Theoretical Inspirations of Amos Rapoport: Reflection on the International Studies on Vernacular Settlement. ISVS E-J. 2022, 1, 1. Available online: https://isvshome.com/pdf/Amos%20Rapoport%20Paper.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Intansari, I.; Saptono, B.; Sugara, U.; Wulandari, S. Disaster Risk Reduction Based on Indigenous Knowledge in Fostering Environmental Care and Student Responsibility. J. Elem. Educ. 2023, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulmayana, N.; Suharini, E.; Sholeh, M. Local Wisdom of Sasak Tribe Community in Dealing with Earthquake Disasters. Int. J. Res. Rev. 2023, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfadrim, Z.; Toyoda, Y.; Kanegae, H. The Integration of Indigenous Knowledge for Disaster Risk Reduction Practices through Scientific Knowledge: Cases from Mentawai Islands, Indonesia. Int. J. Disaster Manag. 2019, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton-Geddes, Z. World Bank. 2017. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/cb952994-d802-5e3a-9c7c-6e2391c7019c (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Hallegate, S. Building Back Better: Achieving Resilience Through Stronger, Faster, and More Inclusive Post-Disaster Reconstruction. 2017. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/420321528985115831/pdf/127215-REVISED-BuildingBackBetter-Web-July18Update.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Build Back Better. UNISDR. 2017. Available online: https://www.unisdr.org/files/53213_bbb.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Sari, M.; Rachman, H.; Astuti, N.J.; Afgani, M.W.; Siroj, R.A. Explanatory Survey dalam Metode Penelitian Deskriptif Kuantitatif. J. Pendidik. Sains Komput. 2022, 3, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. What Is Quantitative Research? An Overview and Guideline. Sage J. 2024. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/14413582241264622 (accessed on 3 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Ma, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Cai, G.; Tang, J.; Yin, D. A Graph Neural Network Framework for Social Recommendations. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 34, 2033–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, D. Social Network Analysis: From Graph Theory to Applications with Python. In Proceedings of the Third Israeli Python Conference (PyCon ’19), Ramat Gan, Israel, 3–5 June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.E. Discrete Categorical Distribution. Available online: https://mlg.eng.cam.ac.uk/teaching/4f13/2425/discrete.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Agresti, A.; Hitchcock, D.B. Bayesian inference for categorical data analysis. Stat. Methods Appl. 2005, 14, 297–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saptaningtyas, R.S.; Paturusi, S.A.; Dwijendra, N.K.A.; Putra, D.G.A.D. Earthquake-Resistant Wooden Connection System in Sasak Traditional Buildings in Sade Village, Lombok, Indonesia. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2023, 11, 1890–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, L.N.T.; Setijanti, P.; Noerwasito, V.T. Traditional Architectural Tectonics Expression of Sasak Tribe as a Form of Earthquake-Resilient Housing Adaptation. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Publ. 2021, 4, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Irasanti, S.N.; Respati, T.; Januarita, R.; Yuniarti, Y.; Chen, H.W.J.; Marzo, R.R. Domain and perception on community resilience: comparison between two countries. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1157837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D.P.; Meyer, M.A. Social Capital and Community Resilience; Sagepub: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, J. The restoration of gotong royong as a form of post-disaster solidarity in Lombok, Indonesia. South East Asia Res. 2021, 29, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmal, I.; Latief, R. The Presence of a Family Communal Space as a Form of Local Wisdom towards Community Cohesion and Resilience in Coastal Settlements. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.A.; Olshansky, R.B. After great disasters: how six countries managed community recovery. In Policy Focus Report Series; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Planning for Post-Disaster Recovery Briefing Papers 7: Planning for Recovery Management. Available online: https://planning-org-uploaded-media.s3.amazonaws.com/document/post-disaster-paper-7-recovery-management.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Berke, P.; Cooper, J.; Aminto, M.; Grabich, S.; Horney, J. Adaptive Planning for Disaster Recovery and Resiliency: An Evaluation of 87 Local Recovery Plans in Eight States. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2015, 80, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasalamwa, S. Is ‘build back better’ a response to vulnerability? Analysis of the post-tsunami humanitarian interventions in Sri Lanka. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr.-Nor. J. Geogr. 2009, 63, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, E.; Wedawatta, G.; Ginige, K. Building-Back-Better in Post-Disaster Recovery: Lessons Learnt from Cyclone Idai-Induced Floods in Zimbabwe. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2021, 12, 700–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arief, A.Z.; Subadyo, A.T. Sustainability in Architecture of traditional Sasak settlements in Lombok. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Graduate School on Sustainability, New York, NY, USA, 18–19 September 2017; PKP: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2017; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Paton, D. Disaster Resilience: An Integrated Approach, 2nd ed.; Charles C. Thomas Publisher, Limited: Springfield, IL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson, L. Ecological and Human Community Resilience in Response to Natural Disasters. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J.; Kelman, I.; Suchet-pearson, S.; Lloyd, K. Integrating indigenous and scientific knowledge bases for disaster risk reduction in papua new guinea. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2009, 91, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safeguarding and Mobilising Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Context of Natural and Human-induced Hazards. UNESCO. 2017. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/38266-EN.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Daskon, C.D. Cultural Resilience—The Roles of Cultural Traditions in Sustaining Rural Livelihoods: A Case Study from Rural Kandyan Villages in Central Sri Lanka. Sustainability 2010, 2, 1080–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kinzig, A. Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social–ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allred, S.; Harris, R.; Zaman, T.; Kulathuramaiyer, N.; Jengan, G. Cultural Resilience in the Face of globalization: Lessons from the Penan of Borneo. Hum. Ecol. 2022, 50, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, T.A. Of Models and Meanings: Cultural Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Hughes, T.P.; Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Rockström, J. Social-Ecological Resilience to Coastal Disasters. Science 2005, 309, 1036–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partelow, S. Social capital and community disaster resilience: post-earthquake tourism recovery in Gili Trawangan, Indonesia. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, F.; Folke, C. Rediscovery of Traditional Ecological Knowledge as Adaptive management. Tradit. Ecol. Knowl. 2000, 10, 1251–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Tsai, H.-M.; Bayrak, M.M.; Lin, Y.-R. Indigenous Resilience to Disasters in Taiwan and Beyond. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, R.R.; Bishwakarma, K.; Ghimire, K.; Shrestha, K.; Maskey, R.; Joshi, B.R.; Gautam, A.; Koirala, M. Disaster Management and Role of Academic Institutions in Nepal: Current Status and Way Forward. Himal. Biodivers. 2020, 8, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniell, J.E.; Vervaeck, A.; Wenzel, F. A timeline of the Socio-economic effects of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake with emphasis on the development of a new worldwide rapid earthquake loss estimation procedure. In Proceedings of the Australian Earthquake Engineering Society 2011 Conference, Barossa Valley, South Australia, 18–20 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Post-Disaster Household Assessment and Links to Social Protection in Indonesia. World Bank. 2024. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099062624071097356/pdf/P17734115891e80081afeb1316d034deace.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Gai, A.; Ernan, R.; Fauzi, A.; Barus, B.; Putra, D. Poverty Reduction Through Adaptive Social Protection and Spatial Poverty Model in Labuan Bajo, Indonesia’s National Strategic Tourism Areas. Sustainability 2025, 17, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Node Number | Node Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Community and Cultural Leaders |

| 2 | Single-Family Compounds |

| 3 | Traditional Villages |

| 4 | Local Government (BPBD) |

| 5 | Mixed Community Villages |

| 6 | External Support |

| Source Node | Target Node |

|---|---|

| 1 | 2 |

| 1 | 3 |

| 1 | 4 |

| 1 | 5 |

| 1 | 6 |

| Program | Scenario | Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural-Based Reconstruction and Building Practices | Preserve Traditional Architectural Designs | Reinforce traditional bale tani (Sasak house) structures by integrating bamboo framework, alang-alang roofing, and woven walls, which are naturally flexible and seismic-resistant. Implement modern retrofitting techniques while maintaining authenticity. |

| Ensure Community-Led Design Approaches | Establish a Pokmas (Kelompok Masyarakat) Housing Initiative, where villagers collectively rebuild homes using gotong royong and traditional craftsmanship. Encourage local artisans and youth apprenticeships to preserve cultural building knowledge. | |

| Enhancing Social Networks through Cultural Practices | Strengthen Gotong Royong as a Recovery Mechanism | Institutionalize gotong royong disaster recovery groups in each village, responsible for debris clearing, temporary shelter construction, and resource-sharing. Create a village-based emergency rotating fund for disaster-affected families. |

| Revitalize Sasak Rituals for Psychological Recovery | Conduct Bale Beleq (traditional music ceremonies) and Burying Coins Rituals for community healing and post-trauma social reintegration. Rituals provide emotional resilience and strengthen community ties. | |

| Reviving and Integrating Traditional Knowledge in Risk Reduction | Develop a Sasak Early Warning System | Document and integrate traditional weather forecasting (e.g., observing animal behavior, wind patterns, and tree blooming cycles) with modern BMKG (Meteorology, Climatology, and Geophysics Agency) forecasts. Train village elders as disaster knowledge bearers. |

| Integrate Sasak Land-Use Wisdom in Zoning Plans | Protect sacred sites and traditional settlement layouts by incorporating Sasak Natah (open courtyard spaces) into resilience-based urban planning to maintain flood escape routes and reduce earthquake damage. | |

| Empowering Cultural Leaders as Central Recovery Actors | Establish Cultural Leaders as Focal Points in Recovery | Appoint Tua-Tua Adat (Sasak elders) and religious leaders as key advisors in disaster governance, relief coordination, and cultural-sensitive policymaking. Conduct disaster mitigation awareness using traditional storytelling (turun temurun knowledge-sharing). |

| Promoting Cultural Livelihoods for Economic Resilience | Strengthen Traditional Handicrafts for Post-Disaster Economic Recovery | Establish earthquake-affected artisan support programs that revive traditional songket weaving and pottery industries as income sources post-disaster. Develop “Resilient Crafts Market” initiatives to boost local economies. |

| Eco-Cultural Tourism for Sustainable Disaster Recovery | Develop “Sasak Resilience Heritage Trails” showcasing disaster-resistant Sasak architecture, eco-friendly village designs, and traditional recovery methods to attract responsible tourism. Ensure tourism infrastructure is earthquake-resistant. | |

| Integrating Cultural Resilience into Policies and Long-Term Recovery Plans | Legally Recognizing Sasak Cultural Resilience in Disaster Policies | Advocate for Sasak cultural disaster resilience frameworks to be included in Indonesia’s Disaster Management Law. Develop policies that mandate cultural impact assessments in post-disaster urban planning. |

| Monitoring and Evaluating Cultural Resilience in Recovery Metrics | Integrate cultural indicators into national disaster risk assessments, ensuring that cultural resilience is a core metric in long-term recovery policies. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sasongko, I.; Gai, A.M.; Wijayaningtyas, M.; Susanti, D.; Sukowiyono, G.; Putra, D. Sasak Cultural Resilience: A Case for Lombok (Indonesia) Earthquake in 2018. Heritage 2025, 8, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8050155

Sasongko I, Gai AM, Wijayaningtyas M, Susanti D, Sukowiyono G, Putra D. Sasak Cultural Resilience: A Case for Lombok (Indonesia) Earthquake in 2018. Heritage. 2025; 8(5):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8050155

Chicago/Turabian StyleSasongko, Ibnu, Ardiyanto M. Gai, Maranatha Wijayaningtyas, Debby Susanti, Gaguk Sukowiyono, and Dekka Putra. 2025. "Sasak Cultural Resilience: A Case for Lombok (Indonesia) Earthquake in 2018" Heritage 8, no. 5: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8050155

APA StyleSasongko, I., Gai, A. M., Wijayaningtyas, M., Susanti, D., Sukowiyono, G., & Putra, D. (2025). Sasak Cultural Resilience: A Case for Lombok (Indonesia) Earthquake in 2018. Heritage, 8(5), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8050155