Abstract

Folk art includes objects that are items for everyday use and, at the same time, gracefully reflect the Greek artistic point of view, drawing its inspiration from life itself, the environment and its beauties, and local tradition. An 18th c. wood-carved and painted chest coming from the famous wood-carved centers of Epirus in Greece is presented in this study. As the number of studies and the general bibliographical references are limited for these kinds of items, prior to interventive conservation, a protocol of analysis was followed to identify the damages, the construction materials, and previous alterations. The main goal of this study is to identify the component materials using non-destructive techniques. The methodology followed for the documentation of the artifact includes the following: a. digital microscopy to identify damage from insects, different cracks and losses on the gesso and paint surface, corrosion products, etc.; b. 3D imaging using a polycam, with special attention given to the inside decoration of the cap; c. IR and UV photography to identify any previous alterations or signs of alterations in the varnish layers; d. and XRF analysis to identify the three (3) main colors of the chest, such as the blue used extensively as a background, red, and white. Nevertheless, the Greek folklore painting palette is limited, and for this reason, this study can be a foundation for research on similar artifacts.

1. Introduction

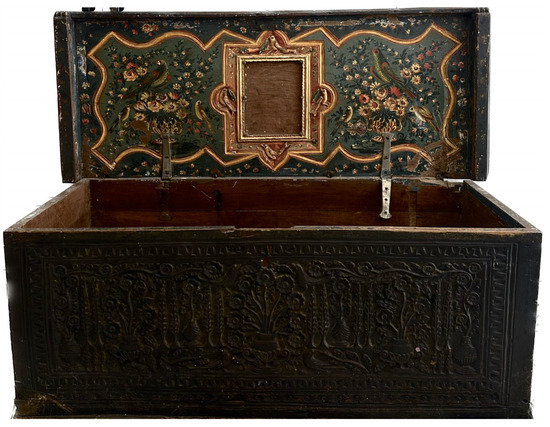

Greek folk art produces objects that serve practical purposes in daily life while embodying the esthetic perspective of the natural and cultural aspects of Greek art [1,2]. These creations are inspired by life, its natural beauty, and local traditions. This study focuses on an 18th-century carved and painted wooden chest, originating from the renowned woodcarving centers of Epirus [3,4] (Figure 1), a historical region in Southeastern Europe. The chest comes from the villages of Epirus, situated in the mountains of Pindus in Northern Greece, between Ioannina to the west and Meteora to the east. Εpirus has a very long tradition in the art of woodcarving, and the names of famous woodcarvers are preserved, who traveled to all Greek-inhabited areas, including the Balkans and beyond [5].

Figure 1.

Τhe case study object, an 18th-century carved and painted wooden chest before any treatment.

The wooden chest under study dates to the 18th century and is a quintessential example of the rich woodcarving tradition of Epirus, a region known for its distinctive craftsmanship. Epirus woodcarving is characterized by intricate floral patterns, geometric designs, and symbolic motifs that are deeply rooted in the region’s cultural and religious history. This tradition flourished during the post-Byzantine period, particularly in the 17th and 18th centuries, and the craftsmanship reflected both local influences and broader trends across the Eastern Mediterranean. The chest, in its form and design, follows this regional tradition and provides insights into the artistic practices of that time [6,7].

However, the influence of Epirus woodcarving extends beyond Greece. Similar carved wooden chests can also be found in regions such as Macedonia, Thrace, and even beyond the borders of the Greek world. These similarities suggest a broader cultural exchange that occurred over centuries as the spread of artistic and craftsmanship traditions was common in the post-Byzantine world.

Similar chests were discovered in Kosovo and Metohija, Serbia, and Slovakia [8], where the woodcarving style and the painted decoration closely resemble those of Epirus. One such chest, attributed to the 18th century, features classic floral patterns and symbolic decorations typical of the region. The chest is believed to have been used to store a bride’s dowry, a common use for such chests, which also highlights the cultural importance of these items as both functional and decorative objects [9].

Similarly, objects with analogous designs have been found in the Islamic world, where the influence of Ottoman craftsmanship is particularly evident in the decorative style. Ottoman-style woodcarving techniques, with their emphasis on floral motifs and geometric patterns, had a significant impact on local craftsmanship throughout Southeast Europe, including regions such as Croatia, Serbia, and parts of Slovakia. These shared stylistic features demonstrate the diffusion of artistic traditions, particularly during the period of Ottoman rule in these regions.

Furthermore, the Benaki Museum in Athens [10], as well as the Μuseum of Modern Greek Culture in Athens [11], houses several examples of similar wooden painted chests. The museum’s collection reveals how regional styles, such as that of Epirus, though distinct, were also part of a larger cultural dialog, where local artistic forms were influenced by broader European and Islamic traditions.

In recent years, the conservation and restoration of wood-carved chests in the Balkan area have become a growing field of interest, highlighting the region’s rich tradition in craftsmanship and material culture [12]. The geographic setup of the Balkans and its long history provides many influences across different cultural settings. These chests, often tied to family histories, religious practices, and local identities, require an interdisciplinary approach, including the combination of scientific analysis with historical and ethnographical research. A detailed analysis of wood chests and their components revealed the use of traditional pigments, such as vermilion, malachite, orpiment, and lead white, while metal surfaces were often made with gold and silver. Gilding is also a common practice applied on such artifacts. Collections in museums have also played a crucial role in documenting and classifying various types of wooden chests, offering valuable context about their construction, use, and current condition [13]. Regarding conservation, non-academic institutions such as the Balkan Heritage Foundation are actively supporting hands-on conservation projects and training initiatives, aiding in the safeguard of cultural heritage, particularly such objects, for future generations [14].

The primary objective of this research was to conduct a comprehensive investigation into the construction materials of this 18th-century carved and painted wooden chest with the goals of understanding its historical context and preserving its integrity. The study also aimed to analyze the chest’s morphology, detailing the shape, structure, and design elements, and to examine its color palette in order to understand the artistic choices and techniques employed in its creation. Non-destructive techniques, including imaging and spectroscopic methods, were employed to ensure that the chest’s physical and esthetic characteristics could be examined without causing any harm to the object itself.

Through this research, valuable insights were gained not only about the chest’s material composition but also about the broader historical and cultural significance of similar objects within Greek folk art. The analysis revealed details about the types of wood and pigments used, as well as the craftsmanship that went into creating the chest. Furthermore, by documenting the various types of damage—such as wear and tear, fading of paint, and possible structural weaknesses—this study highlights the challenges faced by conservators in preserving such objects. The findings contribute to the growing body of knowledge on the conservation of Greek folk art, providing new data that can inform future restoration efforts and deepen our understanding of the historical significance of these objects within their cultural context.

2. Materials and Methods

The chest, with overall dimensions of a 50 cm height and 1.30 cm width, is decorated inside of the lid with floral motifs, vibrant colors, i.e., red, orange, yellow, and white, and two (2) large bird figures on a dark blue background (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Details of the interior decoration of the chest before conservation (left) and after conservation (right).

The two (2) large birds in the right and left center, which are greenish, are not related to any specific species in Greece, but could, due to their intensely colored body structure and small chain and beak, represent parrots (a non-Greek species).

The black and white bird on the left with the relatively long tail in relation to the rest of its body could be either a White Wagtail (Motacilla alba) or a Common Wagtail (Aegithalos caudatus), both common in Greece. Alternatively, it could be a Magpie (Pica pica), but it would need to have an iridescent blue patch on its wings to be more convincing.

The bird on the right looks more like a pigeon-like species, perhaps a young pigeon (Comumba livia) or a decaocto (Streptopelia decaocto), although in the latter case, it should have a black ring on its neck.

There is also a fourth species of owl in the middle that is depicted four (4) times. It looks like a Little Owl (Atnene noctua), especially on the right [15].

The front face of the chest is decorated with a large vase of flowers between small pears of cypress trees. Close to the large vase at the base, two (2) small birds on the right and left hold branches. The space between the large and small vases is filled with small cypress trees and flowers. The base is decorated with a repeated rosette decoration.

Before undertaking any conservation treatment, a detailed protocol of analysis with non-destructive techniques was followed to assess and document the damages, to determine the materials used in the construction of the chest, and to identify any previous alterations made to the object.

The selected methodology aims to conduct a holistic analysis of the object, with particular emphasis on the interior painted surface of the chest’s lid, which is considered the most crucial area for revealing the object’s history, artistic techniques, and previous interventions. A combination of techniques was specifically chosen to ensure the highest level of detail and accuracy in understanding the materials, morphology, and condition of the chest.

2.1. Digital Microscopy

Nowadays, USB digital microscopy is one of the primary tools utilized prior to any preventive or interventive conservation and can be easily applied in situ. In this study, a ΥPC-X1C digital monocular microscope USB with 1600× enlargement, focus of 15~44 mm, and image resolution of 2560 × 1920 was used. This technique allowed for the identification and detailed examination of insect damage, paint and gesso cracks, and corrosion products (nails, etc.) present on the object. Microscopy primarily focused on the interior surface of the chest’s lid, where the wood’s condition, such as insect infestations and previous attempts of repairs, could be more easily assessed. These micro-level examinations provided valuable information about the physical degradation the chest has undergone over time, as well as insights into the materials used in its construction. By analyzing the intricate details of the surface, we were able to pinpoint specific areas that required intervention and gain a better understanding of how the chest has been affected by environmental parameters, such as humidity, temperature, and insect activity, throughout its history [16].

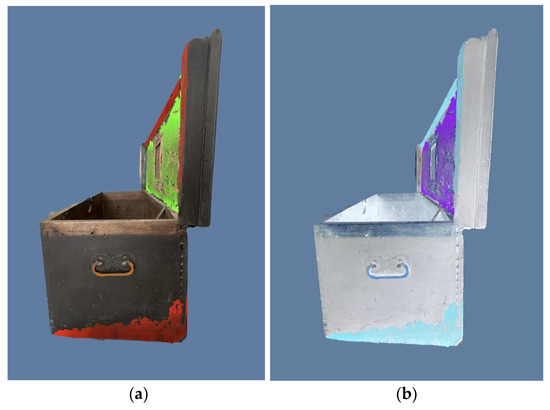

2.2. Three-Dimensional Imaging Using Polycam

To complement the microscopic analysis and gain a more holistic understanding of the chest’s morphology, 3D imaging was performed using Polycam, a state-of-the-art technology that generates highly detailed three-dimensional models of objects. This method was chosen not only to document the object in its entirety but also to inform the conservation strategy which will be used. The 3D models allowed for a more precise visualization of the chest’s form, structural details, and surface features, which would otherwise be difficult to discern through traditional imaging techniques. By mapping the object’s dimensions and contours, this technique facilitated the identification of areas of wear, deformation, or structural instability. Furthermore, the 3D imaging data were useful in informing future restoration efforts, helping to guide the conservators in the decision-making process [17,18].

The process of three-dimensional documentation using the Polycam™ 3D (San Francisco, CA, USA) scanning platform followed a carefully designed methodology to ensure the highest possible accuracy in the final result. The documentation began with a photographic recording of the object, where a series of high-resolution captures were taken from different angles, covering all surfaces and decorative elements. To ensure consistency in the photographic documentation, fixed lighting settings were used, avoiding strong shadows and unwanted reflections that could affect the final processing of the model.

The process involved rotating the camera around the object at different height levels to create a comprehensive dataset, allowing Polycam™ to generate the final three-dimensional model. Additionally, cross-polarized photography techniques were employed to reduce reflections on glossy paint surfaces and capture minor damages and cracks in the material with greater clarity (Figure 3a,b).

Figure 3.

(a,b) The different sides of the wooden chest observed during 3D scanning.

Once a sufficient number of captures were collected, the data were imported into Polycam™, where the application utilized photogrammetry algorithms to generate the initial 3D mesh of the object. Subsequently, geometry optimization was performed to smooth out any imperfections resulting from minor deviations in the photographic captures. The final output was a high-resolution 3D model, providing a reliable representation of the object, including morphological characteristics, color variations, and surface wear.

Polycam™ proved to be an extremely valuable tool as it enabled the creation of a realistic and highly detailed digital representation, which can be used for further analysis, virtual restoration, and comparative studies with similar objects. In a second phase, this model is expected to be transferred and further processed in 3Ds Max™ 2025 (Autodesk Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), aiming for even more precise digital documentation, as well as its future use in research and educational applications [19].

2.3. Infrared (IR) and Ultraviolet (UV) Photography

Infrared and ultraviolet photography were carried out using a DSLR Nikon® D3400 (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) camera along with Hoya®R72 filters (Hoya, Tokyo, Japan). These imaging techniques allowed for the detection of alterations in the varnish layers and other hidden features of the chest, such as previous restoration efforts, over-painting, or modifications to the original surface. IR photography, in particular, is effective at revealing underdrawings or changes made to the object’s design as it can penetrate the upper layers of paint and reveal underlying layers or previous versions of decoration [20,21]. UV photography, on the other hand, provides insights into areas of the chest that may have undergone chemical changes, such as varnish degradation or areas where modern interventions might have been applied. Together, these techniques provided valuable diagnostic data on the chest’s surface and allowed for a deeper understanding of its history, including alterations made in past conservation efforts [22].

2.4. X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Analysis

X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) analysis, a non-destructive method widely used for identifying elemental composition in artifacts [23], was performed using the Bruker© Tracer 5g system (Billerica, MA, USA). Spectra were recorded at spectrometer mode, using a voltage of 50 kV and a current of 15 μA with a 10 s scanning time.

In summary, the combination of digital microscopy, 3D imaging, IR/UV photography, and XRF analysis allowed for a comprehensive and detailed study of the 18th-century chest. These methods were selected to ensure that the object was studied in its entirety, with particular focus on the most vulnerable and informative parts, such as the interior lid. The non-destructive nature of these techniques allowed for the preservation of the chest while still extracting critical data, enabling a thorough analysis of its materials, condition, and historical significance. Each method contributed to a richer understanding of the chest, its artistic and cultural contexts, and the challenges faced in preserving such a significant piece of heritage.

3. Results

3.1. Digital Microscopy

Digital microscopy was a key technique employed to document and study the deterioration levels on the painted surfaces, as well as the presence of cracks, insect damage, and other degradation signs. Using a digital stereo microscope with a magnification power of 1600× (YPC-X1C system), the examination revealed critical details of the chest that were otherwise invisible to the naked eye, especially the intricate damages to the paint layer and structural components.

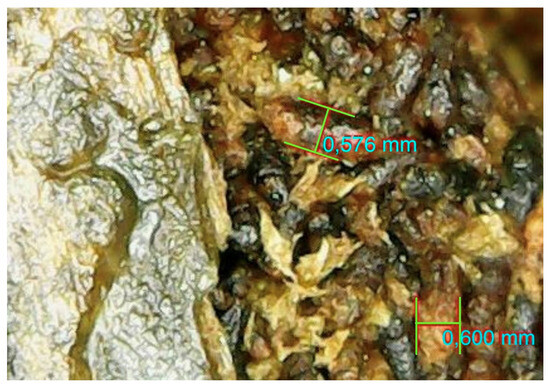

3.1.1. Insect Damage

One of the primary findings from digital microscopy was the confirmation of insect damage on the chest. The infestation appeared most pronounced on the interior surfaces, particularly on the lid, where the wood showed small, round holes (1.5 mm) indicative of wood-boring insects, such as common furniture beetles (Anobium punctatum). These types of insects can cause long-term structural damage by burrowing into the wood and weakening its integrity. Digital microscopy revealed the depth and extent of this damage (Figure 4), allowing for the identification of specific areas that required more immediate attention during the conservation process.

Figure 4.

Details of the insect attack and their products (×50).

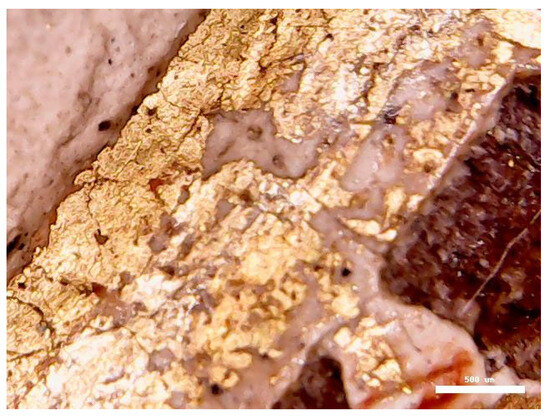

3.1.2. Wood and Paint Cracks

Another significant result from the microscopic examination was the discovery of various cracks in the wood, the gilded areas (Figure 5), and on the painted surface. These cracks, which were not initially visible to the naked eye, were likely due to the natural aging process, as fluctuations in temperature and humidity over time can cause wood to expand and contract. Small and large cracks were identified mainly on the blue background (Figure 6) and on the white paint.

Figure 5.

Losses and cracks on the gilded areas (×20, scale of 500 μm).

Figure 6.

Details of the paint cracks on the blue background of the paint lid (×50, scale of 1000 μm).

Furthermore, a microscopic analysis helped to identify certain enclosed dirt and dust deposits that were not completely removed during the mechanical and chemical cleaning process. These deposits may have accumulated over time due to environmental exposure or previous improper cleaning methods.

3.2. UV and IR Photography

Ultraviolet (UV) and infrared (IR) photography are essential non-destructive techniques that were used to analyze alterations in the varnish layers and to detect hidden details that could not be seen under visible lighting conditions. These imaging methods were employed both before and after mechanical and chemical cleaning procedures to understand the full scope of surface degradation and conservation.

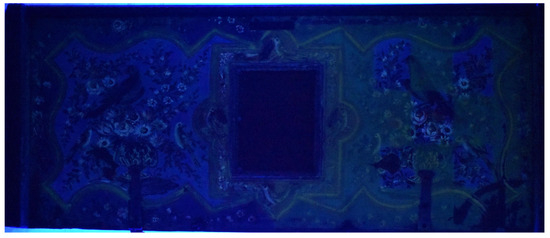

3.2.1. UV Photography Results

Varnish oxidation occurs over time as exposure to light, air, and other environmental factors cause the varnish layer to become discolored, cloudy, or yellowed. This oxidation was most noticeable in five (5) areas on one side of the chest, which were specifically targeted during the cleaning process. Dark areas on the green and orange parts on the large bird figures suggest an older application of over-painting that might exist underneath the varnish layer (Figure 7). It is possible that they were less prominent under UV light because the layer of varnish and dirt deposits were obstructing them.

Figure 7.

(Upper) UV photography revealing over-paintings. (Lower) Incident light photograph of chest.

The UV images clearly highlighted areas where oxidized varnish remained even after the cleaning procedures, demonstrating that there were still visible deposits that had not been fully removed. UV imaging is a valuable tool in detecting such oxidation as it reveals areas that are otherwise invisible under visible radiation, allowing conservators to focus their efforts on specific regions that require further attention.

3.2.2. IR Photography Results

In contrast to UV photography, IR imaging was less effective in detecting previous interventions on the painted surface. IR photography is typically used to reveal under-drawings, hidden layers of paint, or over-painting that might have been applied during past restoration efforts. In this case, IR photography did not show any significant alterations to the original paint layers, suggesting that any past interventions might have been minimal or performed in such a way that did not significantly alter the original design. While IR imaging is typically useful in revealing changes to an object, this particular chest did not exhibit any clear evidence of over-painting or other restoration treatments, at least not in the areas that were analyzed.

3.3. Three-Dimensional Imaging

The final output created using Polycam was a high-resolution 3D model and was able to capture minor damages and cracks in the material with greater clarity. This reliable representation of the object, including morphological characteristics, color variations, and surface wear, can be useful for the documentation of the object. Apart from the fundamental role in documentation, this 3D model of the woodcarved chest can also offer significant advantages for future conservation, research, and public engagement [24,25]. For example, the 3D model is suitable for precise condition monitoring and virtual planning of future restoration interventions. In this way, it is possible for researchers/conservators to simulate and understand any potential treatments before physically applying them [26]. Furthermore, through the 3D model, it is possible to identify structural issues or tool marks depending on the acquired resolution, contributing to research on woodcarving techniques and regional manufacturing traditions [27]. From an educational perspective, 3D models generally facilitate remote access to cultural heritage, supporting online exhibitions and interactive learning without physical contact with the original object [28]. Additionally, 3D data are critical in risk management, enabling accurate replicas or mounts in the event of substantial damage or complete loss of the object. Finally, in recent decades, virtual and augmented reality has been a common practice followed by various institutions, and 3D models such as the one created in the framework of this research can play a significant role in creating immersive experiences that enhance public understanding of historical artifacts.

3.4. X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Analysis

X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) is a non-destructive analytical method that allows for the identification of elements present in the paint layers, providing valuable insights into the materials used and the object’s historical context. The technique was employed with conditions (see Section 2.4 in Materials and Methods) that allowed for the non-destructive detection of specific pigments used in the chest’s decoration, such as common colors like blue, red, and white, which are often derived from particular minerals or synthetic compounds [29,30,31].

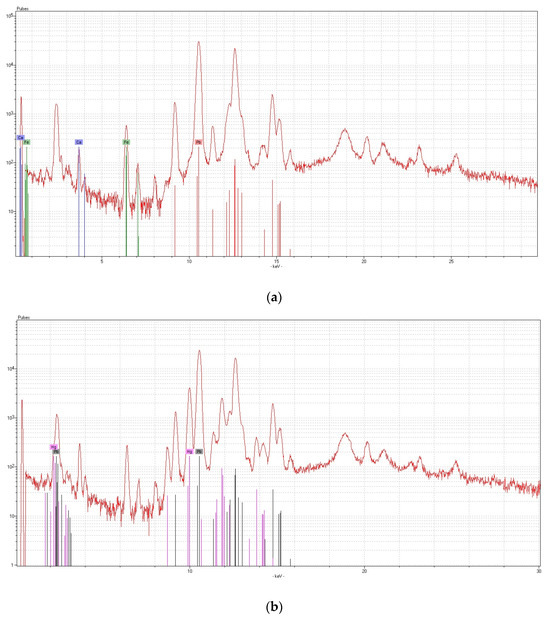

Identification of Main Pigments

XRF analysis was applied on areas carrying three (3) main colors which are typical of the traditional Greek folk art color palette and were used for the decoration of the chest: blue, red, and white (Figure 8). This finding helped confirm the authenticity of the object as these pigments are widely known for their use in 18th-century Greek folk art tradition. The analysis also provided insights into the use of natural pigments, which were common during the period when the chest was created. The results indicate that the blue and red pigments were likely derived from Prussian blue and vermilion/cinnabar, both of which were commonly used during the period [32,33,34,35].

Figure 8.

Spot areas for XRF analysis: 1. blue, 2. red, and 3. white.

- Sample No. 1 (blue background): XRF was applied in situ on the left side of the chest, and the results show the presence of lead (Pb), suggesting the use of lead white and a small amount of iron (Fe) indicating Prussian blue pigment. The high concentration of lead white in this sample suggests that this pigment was primarily used to create the blue background color. Prussian blue, a synthetic pigment introduced in the early 18th century, was used to enhance the vibrancy of blue tones. The combination of these two pigments is consistent with the color palettes used during this period, and their identification provides significant evidence for dating the chest to the 18th century (Figure 9a).

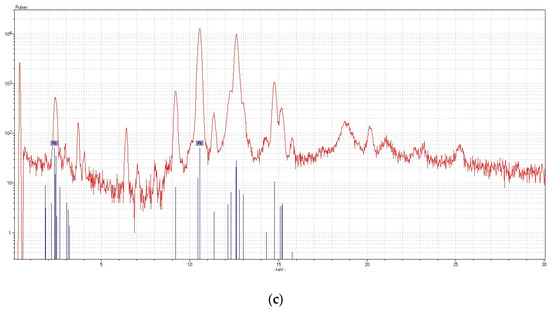

Figure 9. (a) The spectrum of spot area No. 1 showing the characteristic peaks of lead (Pb) and iron (Fe), suggesting the use of Prussian blue. (b) The spectrum of spot area No. 2 showing the characteristic peaks of lead (Pb) and mercury (Hg), suggesting the mixture of lead white with vermilion/cinnabar. (c) The spectrum of spot area No. 3 showing the characteristic peaks of lead (Pb), suggesting the use of lead white.

Figure 9. (a) The spectrum of spot area No. 1 showing the characteristic peaks of lead (Pb) and iron (Fe), suggesting the use of Prussian blue. (b) The spectrum of spot area No. 2 showing the characteristic peaks of lead (Pb) and mercury (Hg), suggesting the mixture of lead white with vermilion/cinnabar. (c) The spectrum of spot area No. 3 showing the characteristic peaks of lead (Pb), suggesting the use of lead white. - Sample No. 2 (red color): The red color, located on the bottom left of the chest, was found to contain mercury (Hg) and lead (Pb), suggesting the use of vermilion/cinnabar and lead white, respectively (Figure 9b). Lead white alongside vermilion/cinnabar supports the notion that this sample represents a typical formulation for a red pigment of this period; in this, vermilion/cinnabar was added to create vivid red hues, while softer tones were created by using a higher proportion of lead (Pb) in the mixture. This aligns with common practices in 18th-century folk art, where artists often used a combination of pigments to achieve specific color effects [36].

- Sample No. 3 (white color): The XRF results for the white areas of the chest reveal only lead (Pb), suggesting the use of lead white (Figure 9c), a popular pigment in the 18th century, used not only for its opacity but also for its ability to provide a bright, smooth finish. The use of lead white in the white areas of the chest is consistent with the techniques of the time and reinforces the chest’s chronological dating.

4. Discussion

The combination of digital microscopy, IR and UV photography, and XRF analysis provided a comprehensive understanding of the 18th-century carved chest. These techniques enabled the identification of critical information about the chest’s condition, the pigments used, and the methods employed in its creation. Digital microscopy revealed insect damage, wood and paint cracks, and residual dirt deposits. While UV photography revealed useful information about previous alterations, IR photography proved less effective in detecting prior interventions or underlying layers of paint. This suggests that the object underwent limited restoration or over-painting, and most of the original design remained intact. This finding is significant as it suggests that the object has retained much of its original artistic integrity, which is crucial for both its historical value and its conservation.

Finally, the XRF analysis confirmed the authenticity of the chest’s 18th-century pigment palette, especially by identifying lead white and Prussian blue. This technique proved instrumental in determining the palette of pigments used by the original artist, as well as in providing insights into the materials available at the time of its creation. Understanding the pigment composition also provided useful information on the historical context, such as trade routes and material availability, that influenced the choices of colors used in the chest’s decoration. Additionally, XRF data helped establish whether any modern materials had been used in past interventions or repairs, giving further context to the conservation history of the object. This outcome provided valuable chronological context for the construction of this chest.

Chronological Context and Authenticity

The XRF analysis of the pigments used on the chest provided significant information about the historical context of the object. The presence of lead (Pb) white, along with Prussian blue and vermilion/cinnabar, confirms that the chest was made during a time when these pigments were widely available and commonly used in both Greek and European folk art. The findings support the chest being dated to the 18th century and further substantiate its authenticity as an artifact of that period [37,38].

The findings from this study offer new insights into the chest’s historical significance, artistic techniques, and conservation needs. By using these non-destructive methods, this study not only preserved the integrity of the object but also contributed to a deeper understanding of Greek folk art and its broader European connections. The results will inform future conservation efforts and help ensure the longevity of this valuable cultural artifact.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of the 18th-century wood-carved chest provided valuable insights into its construction, materials, artistic significance, and conservation needs. Through the application of non-destructive analytical techniques, such as digital microscopy, infrared (IR) and ultraviolet (UV) photography, and X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) analysis, a comprehensive understanding of the object’s condition, history, and authenticity was established. These techniques, when used in combination, revealed important details about the chest’s past, its design influences, and the overall craftsmanship associated with the Epirus woodcarving tradition. This research contributes not only to the preservation of this particular object but also to the broader understanding of Greek folk art, its historical development, and the materials and methods employed by artisans during the 18th century.

The microscopic analysis revealed the extent of damage caused to the chest’s surface, including insect infestations, cracks in the wood, and residual dirt deposits. The detection of insect damage, particularly within the wooden structure, highlighted the need for targeted conservation efforts to address the degradation of the wood without further compromising the painted surface. The microscopic examination also identified cracks in the painted surface, which are a common result of aging and environmental stress. The identification of these cracks was essential in understanding the extent of deterioration and in formulating a conservation plan that would stabilize the object while preserving its decorative integrity.

The XRF analysis provided crucial data on the pigments used in the chest’s decoration, identifying the presence of lead white, Prussian blue, and vermilion/cinnabar. These pigments are characteristic of the 18th century, and their identification confirmed the chest’s chronological dating [39] (Ashok 1993). The use of these pigments not only corroborates the authenticity of the object but also contributes to our understanding of the materials available to artisans at the time. Lead white, in particular, was widely used in the 18th century, and its presence in all the pigment samples analyzed provides a significant clue regarding the chest’s authenticity. The Prussian blue and vermilion/cinnabar found on the chest, while more expensive and less common, further highlight the artistic quality and value of the chest, confirming its high status within folk art tradition. Similar pigments have also been identified in wooden objects/artifacts dating to the same period [12,40,41,42].

For future conservation efforts, the findings of this study will serve as a guide in preserving the chest’s physical and artistic integrity. The data gathered through microscopy and imaging will inform future decisions about cleaning, stabilization, and intervention techniques, ensuring that the chest remains preserved for future generations. Additionally, the use of non-invasive techniques in this study highlights the potential for similar methods to be applied to other artifacts within Greek folk art collections, providing a model for future research and conservation projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and C.K.; methodology, C.K.; validation C.K. and A.O.; formal analysis, A.B. and S.B.; investigation, A.B., C.K. and M.F.; resources, A.B., M.F. and C.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B., C.K., A.O. and S.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B., C.K., A.O. and S.B.; visualization, A.B. and C.K.; supervision, C.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Georgios Karrisfrom the Department of Environment at the Ionian University for the identification of the bird figures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kynigou-Flamboura, M. Folk Art; Benaki Museum: Athens, Greece, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Meraklis, M. The Advocasy of Foklore; Benaki Museum: Athens, Greece, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Papantoniou, I.; Gougouli, C. Ethnographica 10: Tribute to Epirus; Peloponnesian Folklore Foundation: Nafplio, Greece, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Makri, K. Ecclesiastical Woodcarved; Apostoliki Diakonia of the Church of Greece: Athens, Greece, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Κalousios, D. Metsovites woodcarvers at the prefectures of Trikala (18th, 19th and 20th century). In Proceedings of the 1st Conference of Metsovos’ Studies, Metsovo, Greece, 28–30 June 1991; Athens, Greece, 1993; pp. 217–290. [Google Scholar]

- Sioulis, T. Epirus woodcarvers and Macedonian woodcarving. Epirotic Chron. 2001, 35, 221–257. [Google Scholar]

- Stamelos, D. Modern Greek Folk Art; Gutenberg: Athens, Greece, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Vojnović, B. Influences of Artistic Styles in the Croatian Folk Art. Etnol. Res. 2012, 17, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Goosteo. 250 Years of Wooden Chest Craftsmanship in Solkan. 2020. Available online: http://goosteo.nvoplanota.si/dogodki-v-sliki-in-besedi/2020/250-solkan-2020 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Benaki Museum (n.d.). Post-Byzantine and Neo-Hellenic Art. Painted Wooden Chest (ΓΕ31165) Woodcarved Chests in Greek Folk Tradition. Available online: https://www.benaki.org/index.php?option=com_collectionitems&view=collectionitem&Itemid=540&id=142793&lang=en (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Museum of Modern Greek Culture. Wood-Carving. Available online: https://www.mnep.gr/en/collection/the-collection/wood-carving/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Gavrilović, M.; Rančić, D.; Oskolski, A.; Matić, M.; Kocev, M.; Jelikić, A.; Janaćković, P. The coffin-reliquary of the holy Serbian king Stefan of Dečani (fourteenth century): Wood, pigments and metal surfaces. J. Wood Sci. 2024, 70, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanković, T. Wooden chests in the Ethnographic Museum in Zagreb: Typology and preservation status. Ethnol. Res. 2020, 25, 81–93. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/359771 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Balkan Heritage Foundation. Conservation & Restoration Initiatives. 2024. Available online: https://balkanheritage.org/our-heritage/conservation-restoration (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Akriotis, T.; Poirazidis, K.; Karris, G.; Mpontzorlos, B. The birds (Τα πτηνά). In H Πανίδα της Ελλάδας—Βιολογία και Διαχείριση της Άγριας Πανίδας; Pafilis, P., Ed.; Broken Hill Publishers Ltd.: Athens, Greece, 2020; pp. 681–756. [Google Scholar]

- Eastaugh, N.; Walsh, V. Optical microscopy. In Conservation of Easel Paintings; Stoner, J., Rushfield, R., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 322–334. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, S.; Siatou, A.; Degrigny, C.; Mansouri, A.; Sitnik, R. Appearance segmentation and documentation applied to cultural heritage surfaces. Electron. Imaging 2023, 35, 101-1-101-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siatou, A.; Papanikolaou, A.; Saiti, E. Adaption of Imaging Techniques for Monitoring Cultural Heritage Objects. In Advanced Nondestructive and Structural Techniques for Diagnosis, Redesign and Health Monitoring for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage; Osman, A., Moropoulou, A., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Liu, Y. Preserving Sculptural Heritage in the Era of Digital Transformation: Methods and Challenges of 3D Art Assessment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Κontogeorgis, A. Infrared Photography; Ion: Athens, Greece, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- National Gallery Alexandros Soutsos Museum. Imaging Techniques. Available online: https://conservation.nationalgallery.gr/Exhibition.aspx?menuID=49&cul=en (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Amadori, M.L.; Poldi, G.; Germinario, G.; Arduini, J.; Mengacci, V. Spectroscopic and Imaging Analyses on Easel Paintings by Giovanni Santi. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccolieri, G.; Castellano, A.; Iacobelli, V.N.; Carbone, G.G.; Serra, A.; Calcagnile, L.; Buccolieri, A. Non-Destructive In Situ Investigation of the Study of a Medieval Copper Alloy Door in Canosa di Puglia (Southern Italy). Heritage 2022, 5, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosi, C.; Calienno, L.; Fodaro, D.; Borrelli, E.; Rubino, A.R.; Sforzini, L.; Lo Monaco, A. An integrated approach to the conservation of a wooden sculpture representing Saint Joseph by the workshop of Ignaz Günther (1727–1775): Analysis, laser cleaning and 3D documentation. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 17, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanteri, L.; Agresti, G.; Pelosi, C. A New Practical Approach for 3D Documentation in Ultraviolet Fluorescence and Infrared Reflectography of Polychromatic Sculptures as Fundamental Step in Restoration. Heritage 2019, 2, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balletti, C.; Ballarin, M. An Application of Integrated 3D Technologies for Replicas in Cultural Heritage. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clini, P.; Quattrini, R.; Fiori, F. Digital documentation and virtual reconstruction of wooden artworks for restoration and dissemination. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 20, 696–705. [Google Scholar]

- Stylianidis, E.; Remondino, F. 3D Recording, Documentation and Management of Cultural Heritage; Whittles Publishing: Dunbeath, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Romantzi, K. Study and Analysis of Pigments in Paintings of the “Giorgio De Kiriko”, Art Space Collection (Volos, Greece), employing non-destructive techniques. 2017. Available online: https://hellanicus.lib.aegean.gr/handle/11610/17473 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Szökefalvi-Nagy, Z.; Demeter, I.; Kocsonya, A.; Kovács, I. Non-destructive XRF analysis of paintings. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2004, 226, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Asvestas, A.; Gerodimos, T.; Anagnostopoulos, D.F. Revealing the Materials, Painting Techniques, and State of Preservation of a Heavily Altered Early 19th Century Greek Icon through MA-XRF. Heritage 2023, 6, 1903–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D. The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting; Dover Publications: Chicago, IL, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Nöller, R. Cinnabar reviewed: Characterization of the red pigment and its reactions. Stud. Conserv. 2014, 60, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddall, R. Mineral Pigments in Archaeology: Their Analysis and the Range of Available Materials. Minerals 2018, 8, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.R.; Sharma, A. Prussian blue pigment: Bridging the historical palette to modern innovations. Hist. Sci. Technol. 2024, 14, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reus, S.; de Sotto Bastos, E.; van Bommel, M.R.; van den Berg, K.J. Investigation of 19th and early 20th century Prussian blue production methods and their influence on the pigment composition and properties. Dyes Pigment. 2024, 225, 112093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminari, A.; Alexopoulou, A. The Contribution of Imaging Techniques in the Study of Post- Byzantine icons. Characteristic Case Studies from the ARTICON Laboratory. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Meeting Conservation and Documentation of Ecclesiastical Artefacts, Ionian University, Zakynthos, Greece, 14–15 December 2016; pp. 216–222. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, V. The Brilliant History of Color in Art; J. Paul Getty Museum: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 86–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ashok, R. Artists’ Pigments a Handbook of Their History and Characteristics; National Gallery of Art, Washington, Archetype Publications: London, UK, 1993; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sanches, F.A.C.R.A.; Nardes, R.C.; Santos, R.S.; Gama Filho, H.S.; Machado, A.S.; Leitão, R.G.; Leitão, C.C.G.; Calgam, T.E.; Bueno, R.; Assis, J.T.; et al. Characterization an wooden Pietà sculpture from the XVIII century using XRF and microct techniques. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2023, 202, 110556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiapali, M.; Vivdenko, S.; Tsangalidis, H.; Konstanta, A.; Mitsos, M.; Mantzana, E.; Vasileiadou, A.; Zacharias, N. Archaeometric investigation of pigments of the iconostasis from Saint Georgios church of Sohos. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2023, 52, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrotheodoros, G.P.; Beltsios, K.G. Pigments-Iron-based red, yellow, and brown ochres. Archaeol. Anthr. Sci. 2022, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).