From Thermal City to Well-Being Landscape: A Proposal for the UNESCO Heritage Site of Pineta Park in Montecatini Terme

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Spa Towns and Well-Being Landscapes

1.2. Evolution and Current Challenges of Spa Towns

2. Objective and Methodology

- What is the value of a landscape and territorial approach in safeguarding the tangible and intangible heritage of thermal cities?

- How can landscape design support a sustainable, compatible, and context-sensitive transformation of thermal cities?

3. The Case Study

3.1. The Great Spa Towns of Europe

3.2. The Site of Montecatini Terme, Italy

3.3. Heritage Preservation Constraints

- Protection areas within the UNESCO-listed site (core and buffer zones) (Cultural Heritage and Landscape Code, Art. 143, c.1) [83].

- Landscape assets designated under the Cultural Heritage and Landscape Code (Art. 136) and legally protected areas such as waterways (Art. 142).

- Architectural assets under formal heritage protection orders.

4. Landscape Analysis

4.1. Strengths

- Central location in the heart of the city—the park’s central position enhances accessibility for both residents and visitors, contributing to its attractiveness and ease of access.

- Strategic placement of viewpoints—carefully positioned viewpoints highlight the park’s iconic landmarks and panoramic vistas, increasing its visual appeal and stimulating visitors’ imagination.

- Diverse architectural palimpsest—the park features a variety of architectural styles and structures that narrate layers of history and culture, offering visitors a fascinating journey through time and a deeper appreciation of its cultural fabric.

- Water features and thermal springs—beyond their aesthetic beauty, these natural elements provide therapeutic benefits, creating a serene and invigorating environment that enhances the overall visitor experience, making the park an ideal destination for relaxation and well-being.

4.2. Weaknesses

- Lack of designated spaces for events—the absence of dedicated areas for cultural and musical performances limits the park’s ability to attract new visitors and may redirect such activities to alternative locations.

- Insufficient focal points—it is essential for users to have a clear sense of destination or well-defined pathways leading to points of interest.

- Lack of regular maintenance—insufficient upkeep led to the deterioration of structures and the gradual loss of natural features over time.

- Absence of an intermediate vegetation layer—this lack reduces ecosystem diversity, affecting habitat complexity and biodiversity. It also diminishes the park’s aesthetic appeal and ecological resilience.

- Extensive use of asphalt—even pedestrian-only pathways, including secondary routes, are paved with asphalt, which is visually unappealing, prone to degradation due to roots and frost, and not well-integrated from a landscape perspective.

4.3. Opportunities

- Creation of contemplative and therapeutic spaces—designated areas could offer visitors tranquil environments immersed in the park’s natural beauty, ideal for relaxation, reflection, and rejuvenation. By leveraging the park’s scenic charm to promote mental and emotional well-being, this initiative could attract wellness seekers and nature enthusiasts, reinforcing the park’s reputation as a destination for holistic health and recovery.

- Development of cultural entertainment spaces—this initiative could position the city advantageously in attracting high-quality tourism while serving as a key asset for enhancing other local offerings.

4.4. Threats

- Loss of identity—the integration of modern elements that do not respect the park’s heritage poses a significant risk. The introduction of contemporary features or structures misaligned with the park’s historical and cultural significance could compromise its authenticity and erode its sense of identity.

- Abandoned construction sites—the presence of unfinished or abandoned construction projects can negatively impact the park’s integrity and visitor experience. Such sites not only detract from the park’s aesthetic appeal but also pose safety and environmental hazards.

- Multiple ownerships—fragmented management and the absence of a unified maintenance approach present major challenges. When different parts of the park are owned or managed by separate entities, conflicting priorities, independent decision-making processes, and varying maintenance standards may arise. This lack of coordination can lead to inconsistencies in visitor experiences, uneven resource distribution, and inefficiencies in overall park management. Moreover, the absence of a cohesive governance model can exacerbate issues such as environmental degradation, habitat fragmentation, and infrastructure decay.

5. Landscape Strategy

5.1. Design Principles

- Attractiveness—ensuring that the park remains engaging and appealing year-round by incorporating functions that cater to diverse user groups.

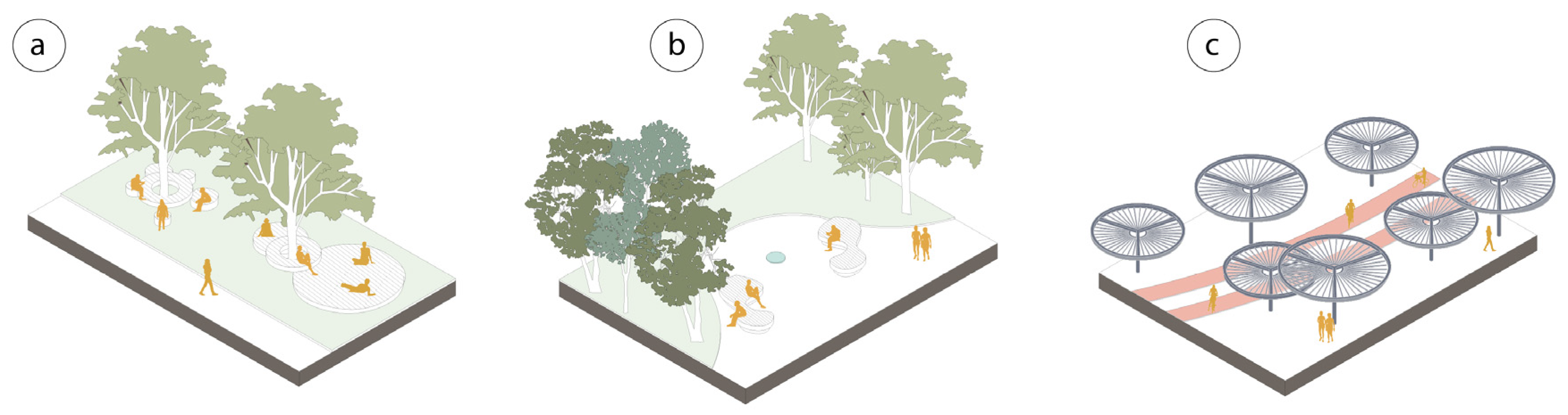

- Variety—designing both open areas with unobstructed views and enclosed spaces suitable for group gatherings or solitude, introducing varied linear pathways to offer diverse spatial experiences.

- Landmark definition—establishing strong focal points that allow clear visibility of destinations and the ability to follow well-defined routes guiding users through the landscape.

- Natural integration—maintaining a balance between natural elements, such as vegetation, and artificial structures, emphasizing the presence of nature while limiting the introduction of new built elements.

- Accessibility—designing barrier-free pathways that ensure universal accessibility and encourage seamless exploration of the park.

- Feasibility—scaling the program in proportion to the technical and financial capacity of the involved stakeholders while considering the impact of the implementation phase on the temporary usability of the park.

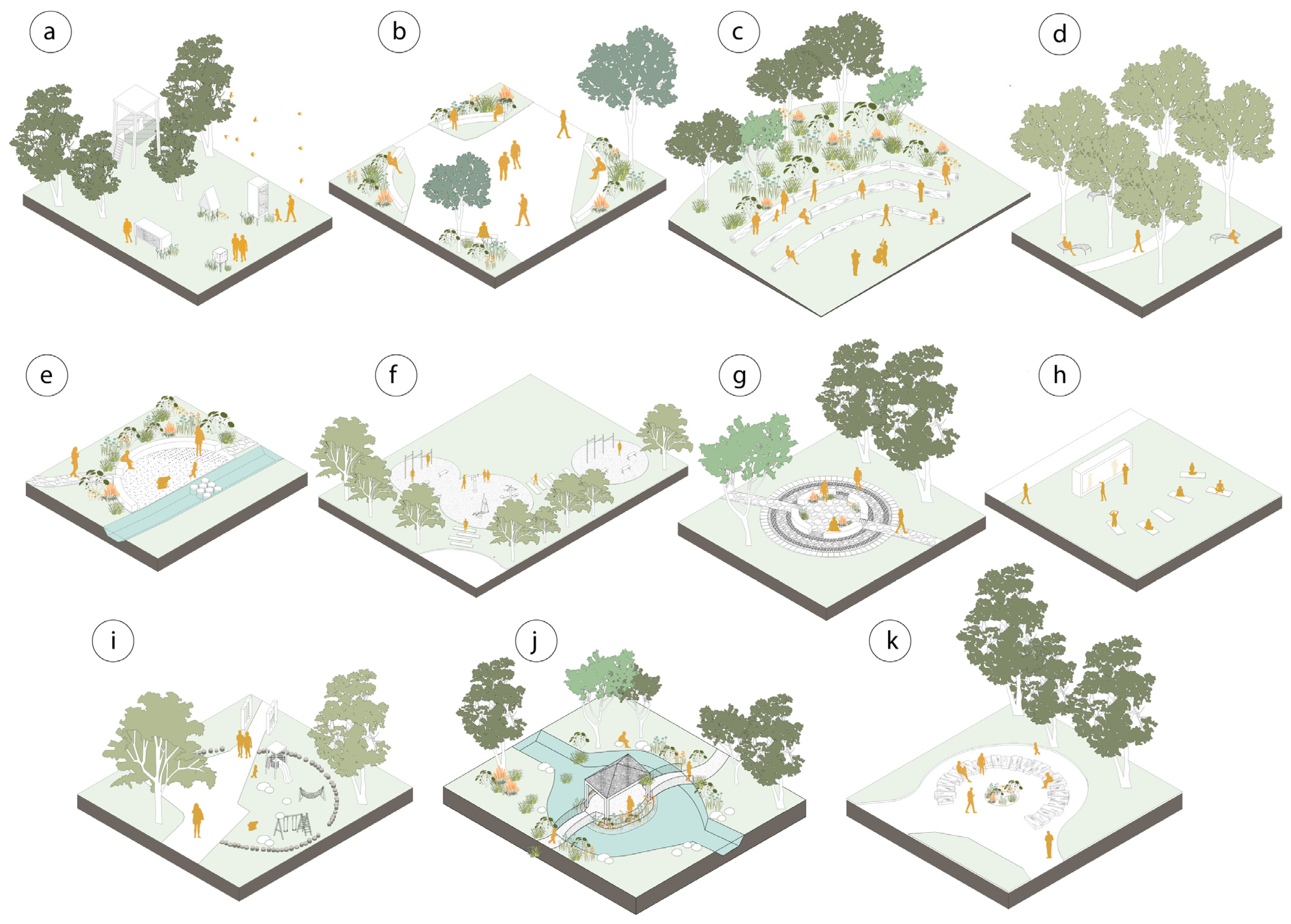

5.2. Operational Program

5.3. Landscape Program

6. Landscape Design

6.1. Structural Interventions

6.1.1. Nodes

6.1.2. Axes

6.2. Auxiliary Interventions

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

- Recognizing thermal landscapes as a synthesis of cultural values. In the case of Montecatini, the role of Pineta Park as a connector within the thermal system was evident from its original design by the architect Bernardini. However, the therapeutic significance of landscapes is a common theme across many European spa towns and can play a key role in the conservation and enhancement of thermal heritage.

- Using territorial and landscape planning as a tool to prevent the fragmentation of heritage and loss of identity. While this issue is particularly urgent for Montecatini, given the imminent sale of thermal buildings, it is also relevant to other spa towns facing abandonment and degradation. Even in cases where direct interventions on architectural heritage are limited, public authorities can still act on the landscape framework, which is crucial for regulating and guiding potential private investments.

- Investing in environmental and landscape quality to support the architectural and urban conservation of spa towns. Viewing the landscape as an integrated and complex system, investments in environmental quality, green areas, parks, and ecological networks are fundamental to preserving the overall value of the historic urban heritage of spa towns.

- Using landscape design as a unifying theme to engage diverse stakeholders. In Montecatini, for instance, the involvement of Fondazione Caript represents an initial step toward expanding stakeholder participation, with potential for further collaboration in future project phases.

- Leveraging landscape design as a driver for the revitalization of declining thermal contexts. Identifying and enhancing the intrinsic qualities of spa town landscapes and strengthening synergies between cultural and natural elements can act as a catalyst for broader regeneration processes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AVAP | Aire de mise en Valeur de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine (Architecture and Heritage Development Area) |

| BIG | Bjarke Ingels Group |

| ECLAS | European Council of Landscape Architecture Schools |

| GI | Green Infrastructure |

| HUL | Historic Urban Landscape |

| NBS | Nature-Based Solution |

| PIT-PPR | Piano di Indirizzo Territoriale con valenza di Piano Paesaggistico (Territorial Strategic Plan) |

| PNRR | Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza (National Recovery and Resilience Plan) |

| PS | Piano Strutturale (Structural Plan) |

| PTC | Piano Territoriale di Coordinamento (Territorial Coordination Plan) |

| RTD | Research through Design |

| RU | Regolamento Urbanistico (Urban Regulation) |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ZPPAUP | Zone de protection du patrimoine architectural urbain et paysager (Zone for the Protection of Urban and Landscape Architectural Heritage) |

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Adams, J.M. Water, Health and Leisure. In Healing with Water: English Spas and the Water Cure, 1840–1960; Adams, J.M., Ed.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2015; pp. 184–222. [Google Scholar]

- Yuill, C.; Mueller-Hirth, N.; Song Tung, N.; Thi Kim Dung, N.; Tram, P.T.; Mabon, L. Landscape and Well-Being: A Conceptual Framework and an Example. Health 2019, 23, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, A.; Sommerhalder, K.; Abel, T. Landscape and Well-Being: A Scoping Study on the Health-Promoting Impact of Outdoor Environments. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. European Spa Culture, and the History and Development of The Great Spas of Europe. In Nomination of GREAT SPAS of Europe for Inclusion on the World Heritage List-Volume I: History and Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; Volume I, pp. 302–358. [Google Scholar]

- Borsay, P. Towns, Heritage, and History. In The Image of Georgian Bath, 1700–2000; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 347–391. [Google Scholar]

- Zanetti, C. I Siti Termali d’Italia Tra Fonti Letterarie e Dati Archeologici. In Aquae Salutiferae. Il Termalismo tra Antico e Contemporaneo, Proceedings of the Atti del Convegno Internazionale, Montegrotto Terme, Italy, 6–8 September 2012; Bassani, M., Bressan, M., Ghedini, F., Eds.; Padova University Press: Padova, Italy, 2013; pp. 231–245. ISBN 978-88-97385-64-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bassani, M. Le Acque Termominerali Nell’Italia Antica Fra Pellegrinaggi e Svaghi. In La Città, il Viaggio, il Turismo. Percezione, Produzione e Trasformazione; Belli, G., Capano, F., Pascariello, M.I., Eds.; CIRICE: Napoli, Italy, 2017; pp. 607–614. ISBN 978-88-99930-02-8. [Google Scholar]

- Danzi, M. Thermal Baths in Europe between Medecine and Literature. Quad. D’ital. 2017, 22, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, A. Canaque Sulphureis Albula Fumat Aquis. Il Termalismo Romano in Italia e Le Fonti Letterarie: Un Quadro d’insieme. In Aquae Salutiferae. Il Termalismo fra Antico e Contemporaneo, Proceeding of the Symposium in Montegrotto Terme, Italy, 6–8 September 2012; Bassani, M., Bressan, M., Ghedini, F., Eds.; Padova University Press: Padova, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cinti, M.G. Turismo Termale in Italia: Evoluzione, Impatti e Prospettive Di Rilancio. Doc. Geogr. 2024, 1, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. History and Development of the Component Parts. In Nomination of GREAT SPAS of Europe for Inclusion on the World Heritage List-Volume I: History of the Component Parts; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; Volume I, pp. 360–442. [Google Scholar]

- Scheid, J.; Nicoud, M.; Boisseuil, D.; Coste, J. Le Thermalisme: Histoire d’un Phénomène Culturel et Médical; CNRS Éditions: Paris, France, 2015; ISBN 978-2-271-08651-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bossaglia, R. Stile e Struttura Delle Città Termali; Banca Provinciale Lombarda: Bergamo, Italy, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Urošević, N. The Spa and Seaside Resort in the Development of Euro—Mediterranean Travel and Tourism—the Case of Brijuni Islands. Int. J. Euro-Mediterr. Stud. 2020, 13, 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Borsay, P.; Hein Furnée, J. Leisure Cultures In Urban Europe, C.1700–1870: A Transnational Perspective; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781526104304. [Google Scholar]

- Laroche, C.; Toulier, B.; Cron, É.; Delorme, F. Architecture et Urbanisme de Villégiature: Un État de La Recherche. Situ 2014, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesler, W.M. Therapeutic Landscapes: Medical Issues in Light of the New Cultural Geography. Soc. Sci. Med. 1992, 34, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesler, W.M. Healing Places; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2003; ISBN 0742519562. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, L.D.; Gesler, W.M. Reconsidering the Concept of Therapeutic Landscapes in J D Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Area 2004, 36, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winchester, M.; McGrath, J. Therapeutic Landscapes: Anthropological Perspectives on Health and Place. Med. Anthropol. Theory 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, R.A.; Gesler, W.M. Putting Health into Place: Landscape, Identity, and Well-Being; Syracuse University Press: Syracuse, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- The Great Spa Towns of Europe. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1613 (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Becheri, E. Il Sistema Termale Della Toscana: Tendenze e Prospettive; UNIONACAMERE Toscana: Firenze, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J.M. The Theory and Practice of the Water Cure. In Healing with Water: English Spas and the Water Cure, 1840–1960; Adams, J.M., Ed.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2015; pp. 23–58. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz, G. Le Thermalisme En France Au XXe Siècle. Ms Med. Sci. 2002, 18, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.M. National Assets and National Interests: Spas and the State. In Healing with Water: English Spas and the Water Cure, 1840–1960; Adams, J.M., Ed.; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2015; pp. 223–256. [Google Scholar]

- Cristini, C.; Porro, A.; Guerrini, G. Termalismo e Invecchiamento Fra Storia e Attualità. Tur. E Psicol. 2014, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Montecatini Terme, Italy. In Nomination of GREAT SPAS of Europe The for inclusion on the World Heritage List; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; Volume I, pp. 250–270. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, S. Trends in the Global Spa Industry. In Understanding the Global Spa Industry; Cohen, M., Bodeker, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 66–84. ISBN 9781136351259. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulou, G. Spa Tourism in Europe: An Economic Approach. Athens J. Tour. 2020, 7, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcea, I.M. The Need to Reconsider the European Balneological Heritage-Two Case Studies: Development by Continuity, Bath, United Kingdom/San Pellegrino, Italy. Argument 2011, 3, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B.M. Reinventions of a Spa Town: The Unique Case of Vichy. J. Tour. Hist. 2012, 4, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, K. The Town of Vichy and the Politics of Identity; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 9783030931971. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanisme à Vichy-Protection Du Patrimoine. Available online: https://www.ville-vichy.fr/urbanisme/protection-patrimoine (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Gigot, M. Les Zones de Protection Du Patrimoine Architectural, Urbain et Paysager (ZPPAUP),Une Forme de Gouvernance Patrimoniale? Cult. Local Gov. 2008, 1, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesler, W.M. Bath’s Reputation as a Healing Place. In Putting Health into Place: Landscape, Identity, and Well-Being; Kearns, R.A., Gesler, W.M., Eds.; Syracuse University Press: Syracuse, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, T. The City of Bath—World Spa and World Heritage. In Europäische Kurstädte und Modebäder des Jahrhunderts; Ediloth, V., Fördererer, A., Ziesemer, J., Eds.; Konrad Theiss Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fabi, V.; Vettori, M.P.; Faroldi, E. Adaptive Reuse Practices and Sustainable Urban Development: Perspectives of Innovation for European Historic Spa Towns. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios Manzano, P.; Gomez Pérez, J. Governance Models for Spa and Health Tourism: Bath and Alang. In Cultural Management and Tourism in European Cultural Routes: From Theory to Practice; Ochoa Siguencia, L., Gomez-Ullate, M., Kamara, A., Eds.; Research and Innovation in Education Institute: Czestochowa, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Perrault, D. Dominique Perrault Architecte; Area, Leisure; Centre Pompidou: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Perrault, D. Baños Termales, San Pellegrino, Lombardía (Italia). AV Proy. 2008, 29, 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Csobán, K.; Szőllős-Tóth, Á.; Sánta, A.K.; Molnár, C.; Pető, K.; Dávid, L.D. Assessment of the Tourism Sector in a Hungarian Spa Town: A Case-Study of Hajdúszoboszló. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2022, 45, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. A Territorial Approach to the Sustainable Development Goals; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; ISBN 9789264719309. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, F. An Agenda for a Reformed Cohesion Policy: A Place-Based Approach to Meeting European Union Challenges and Expectations (Barca Report)|European Website on Integration. In A Place-Based Approach to Meeting European Union Challenges and Expectations-Indipendent Report to the European Commission; Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tzortzi, J.N. The Landscape Design Proposal for the New Archeological Museum of Cyprus. Land 2024, 13, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzholzer, S.; Duchhart, I.; Koh, J. ‘Research through Designing’ in Landscape Architecture. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 113, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picchi, P. Research in Landscape Architecture: System Innovation and Design Approach as Research Challenges for the Future Agenda. R.E.D.S. 4 Biennale Session 2016 “Reporting from the Italian Front”-Designing knowledge At: Biennale of Architecture-Venice. 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317279210_Research_in_Landscape_Architecture_system_innovation_and_design_approach_as_research_challenges_for_the_future_agenda (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Nijhuis, S.; de Vries, J. Design as Research in Landscape Architecture. Landsc. J. 2019, 38, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbergen, C.; Mihl, H.; Reh, W. Introduction: Design Research, Research by Design; Thoth: Bussum, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ginzarly, M.; Houbart, C.; Teller, J. The Historic Urban Landscape Approach to Urban Management: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 999–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. New Life for Historic Cities: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach Explained; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bandarin, F.; van Oers, R. Reconnecting the City: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage; Bandarin, F., van Oers, R., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-118-38398-8. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, Including a Glossary of Definitions; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lux, M.S. Networks and Fragments: An Integrative Approach for Planning Urban Green Infrastructures in Dense Urban Areas. Land 2024, 13, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortzi, J.N.; Lux, M.S. Green Heritage, Green History and Green Planning. In Proceedings of the Book of Abstracts of The Faro Convention Implementation. Heritage Communities as Commons: Relationships, Partecipations and Well-Being in a Shared Multidisciplinary Perspective, Naples, Italy, 16–17 December 2021; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Nocca, F. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Spina, L. Multidimensional Assessment for “Culture-Led” and “Community-Driven” Urban Regeneration as Driver for Trigger Economic Vitality in Urban Historic Centers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hølleland, H.; Skrede, J.; Holmgaard, S.B. Cultural Heritage and Ecosystem Services: A Literature Review. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2017, 19, 210–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortzi, J.N.; Lux, M.S. Re-Starting from Cultural Heritage to Design the Resilience of Historical Urban Centres. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Changing Cities V: Spatial, Design, Landscape, Heritage & Socio-Economic Dimensions, Corfù, Greece, 20–25 June 2022; Gospodini, A., Ed.; Laboratory of Urban Morphology & Design, Department of Planning and Regional Development, University of Thessaly: Corfù, Greece, 2022; pp. 741–751. [Google Scholar]

- World Heritage Committee. Serial Transnational Nominations (WHC-09/33.COM/10A); World Heritage Committee: Seville, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Justification for Inscription and Comparative Analysis. In Nomination of GREAT SPAS of Europe for Inclusion on the World Heritage List; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Executive Summary. In Nomination of GREAT SPAS of Europe for inclusion on the World Heritage List; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Extended 44th Session of the World Heritage Committee (2021)—Nominations to the World Heritage List; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mackaman, D.P. Leisure Settings: Bourgeois Culture, Medicine, and the Spa in Modern France; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998; ISBN 0226500756. [Google Scholar]

- Bocchio, C.; Massi, C. Montecatini Terme Nella Candidatura Seriale Transnazionale “The Great Spas of Europe” La Convenzione UNESCO Sulla Protezione Del Patrimonio Mondiale; Bollettino dell’Accademia degli Euteleti: San Miniato, Italy, 2019; pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Massi, C. Montecatini Terme: L’invenzione Della Moderna Città Termale; Edifir editions Florence: Firenze, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Santoianni, V. Montecatini Terme; Octavo: Firenze, Italy, 2000; ISBN 9788880302049. [Google Scholar]

- Massi, C. Montecatini Terme: L’identità Della Ville d’eau; Bollettino della Accademia degli Euteleti,: San Minniato, Italy, 2013; pp. 553–578. [Google Scholar]

- De’Fiori, M. Un’estate Ai Bagni Di Montecatini; Melani, N., Ed.; Tipo-Lit Grotta Giusti: Pistoia, Italy, 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Michelotti, A. Montecatini Terme; Edizioni del Palazzo: Prato, Italy, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Massi, C. Alla Scoperta Delle Città Termali Mitteleuropee Agli Esordi Del Novecento. Il Viaggio Di Giulio Bernardini per La Nuova Montecatini; Bollettino dell’Accademia degli Euteleti: San Miniato, Italy, 2017; pp. 139–172. [Google Scholar]

- Massi, C. Il Parco Termale Nella Montecatini Del Primo Novecento Dopo l’esperienza Mitteleuropea Di Giulio Bernardini. Riv. Di Stor. Dell’agricoltura 2007, 47, 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, M.A.; Giovannelli, R. Montecatini: Città Giardino Delle Terme; Skira: Milano, Italy, 2001; ISBN 9788881189458. [Google Scholar]

- Romei, P. Territorio e Turismo: Un Lungo Dialogo. Il Modello Di Specializzazione Turistica Di Montecatini Terme; Firenze University Press: Firenze, Italy, 2016; pp. 1–240. [Google Scholar]

- Becheri, E. Turismo Termale e Del Benessere in Toscana: Fra Tradizione Ed Innovazione; Mercury S.R.L: San Giovanni in Persiceto, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gonfiantini, G. Montecatini, Addio Sogni Da Archistar. CORRIRE FIORENTINO, 28 February 2016, p. 9.

- Regione Tosccana. PIT-Piano Di Indirizzo Territoriale Con Valenza Di Piano Paesaggistico; Mibact: Firenze, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Provincia di Pistoia. Piano Territoriale Di Coordinamento. Available online: https://www.provincia.pistoia.it/ptc (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Comune di Montecatini Terme. Piano Strutturale. Available online: https://archivio.comune.montecatini-terme.pt.it/servizi/Menu/dinamica.aspx?idSezione=616&idArea=16293&idCat=16316&ID=25348&TipoElemento=pagina (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Regione Toscana. Val Di Nievole e Val d’arno Inferiore. In PIT-Piano di Indirizzo Territoriale con valenza di Piano Paesaggistico; Settore Tutela, R.E.V.D.P., Ed.; Mibact: Firenze, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Repubblica Italiana. Decreto Legislativo 29 Ottobre 1999, n. 490. Testo Unico Delle Disposizioni Legislative in Materia Di Beni Culturali e Ambientali, a Norma Dell’art. 1 Della Legge 8 Ottobre 1997. Testo 1999, 490. [Google Scholar]

- Repubblica Italiana. Decreto Legislativo 22 Gennaio 2004, n. 42 Codice Dei Beni Culturali e Del Paesaggio, Ai Sensi Dell’articolo 10 Della Legge 6 Luglio 2002. 2004. Available online: https://www.bosettiegatti.eu/info/norme/statali/2004_0042.htm (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Sztubecka, M.; Maciejko, A.; Skiba, M. The Landscape of the Spa Parks Creation through Components Influencing Environmental Perception Using Multi-Criteria Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F.; van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 9780470655740. [Google Scholar]

- Nadin, V.; van der Toorn Vrijthoff, W.; Mashayekhi, A.; Arjomand Kermani, A.; Zhou, J.; Pendlebury, J.; Miciukiewicz, K.; Cowie, P.; Scott, M.; Redmond, D.; et al. A Sustainable Future for the Historic Urban Core; Nadin, V., van der Toorn Vrijthoff, W., Mashayekhi, A., Eds.; Urbanism, TU Delft: Delft, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Słonina, D.; Skomorowska, M. The Value of Spa Parks in the Modern Health Resorts: A Case Study of the Western and Central Sudetes Spa Towns. Archit. Kraj. 2018, nr 3, 20–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, W.; Czałczyńska-Podolska, M. Contemporary Significance of the Spa Park Based on the Study of the Recognition of the Health Resort Space. Space Form|Przestrz. I Forma 2023, nr 56, 145–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryglas, D.; Salamaga, M. Therapeutic Landscape as Value Added in the Structure of the Destination-Specific Therapeutic Tourism Product: The Case Study of Polish Spa Resorts-Specific Therapeutic Tourism Product, Therapeutic Landscape, Health Tourism, Spa Resort, Poland. An. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2023, 71, 782–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lux, M.S.; Tzortzi, J.N. From Thermal City to Well-Being Landscape: A Proposal for the UNESCO Heritage Site of Pineta Park in Montecatini Terme. Heritage 2025, 8, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8040123

Lux MS, Tzortzi JN. From Thermal City to Well-Being Landscape: A Proposal for the UNESCO Heritage Site of Pineta Park in Montecatini Terme. Heritage. 2025; 8(4):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8040123

Chicago/Turabian StyleLux, Maria Stella, and Julia Nerantzia Tzortzi. 2025. "From Thermal City to Well-Being Landscape: A Proposal for the UNESCO Heritage Site of Pineta Park in Montecatini Terme" Heritage 8, no. 4: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8040123

APA StyleLux, M. S., & Tzortzi, J. N. (2025). From Thermal City to Well-Being Landscape: A Proposal for the UNESCO Heritage Site of Pineta Park in Montecatini Terme. Heritage, 8(4), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8040123