Characterization and Analysis of Gypsum Alabaster Constituting the “Santissimo Salvatore” Statue by Gabriele Brunelli (Bologna, 1615–1682)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection from the Statue and Specific Preparation

2.2. Analytical Methods

2.3. Alabaster Geological Provenance

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optical Microscopy

3.2. X-Ray Powder Diffraction

3.3. FE-ESEM, EDS

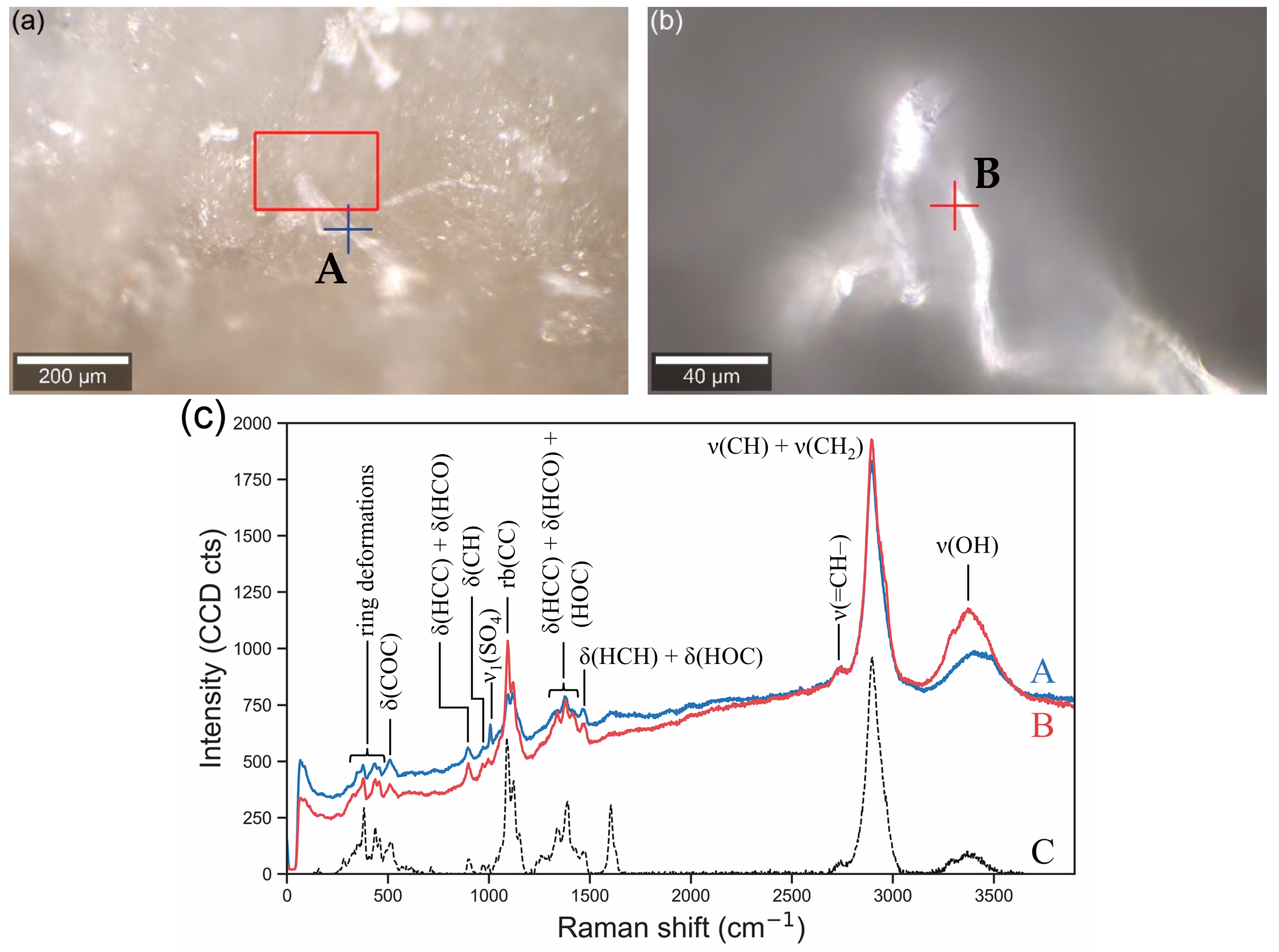

3.4. Raman

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poli, M. La Chiesa Canonicale Del SS. Salvatore. Un Complesso Architettonico Innovativo Nel Cuore Di Bologna; Costa Editore: Bologna, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Trombelli, G.C. Memorie Istoriche Concernenti Le Due Canoniche Di S. Maria Di Reno e Di S. Salvatore Insieme Unite; Corciolani: Bologna, Italy, 1752. [Google Scholar]

- Malvasia, C.C. Le Pitture Di Bologna Che Nella Pretesa, e Rimostrata Sin Hora Da Altri Maggiore Antichità, & Impareggiabile Eccellenza Nella Pittura, Con Manifesta Evidenza Di Fatto, Rendono Il Passeggiere Disingannato Ed Instrutto Dell’Ascoso Accademico Gelato; Giacomo Monti: Bologna, Italy, 1686. [Google Scholar]

- Oretti, M. Pitture Nelle Chiese Della Città Di Bologna; Biblioteca Comunale dell’Archiginnasio: Bologna, Italy, 1767; Volume B30. [Google Scholar]

- Malvasia, C.C. Pitture, Scolture Ed Architetture Delle Chiese Luoghi Pubblici, Palazzi, e Case Della Città Di Bologna, e Suoi Sobborghi: Con Un Copioso Indice Degli Autori Delle Medesime, Corredato Di Una Compendiosa Serie de Notizie Storiche Di Ciascheduno; Longhi: Bologna, Italy, 1782. [Google Scholar]

- Oretti, M. Notizie de Professori Del Disegno Cioè Pittori Scultori Ed Architetti Bolognesi e de Forestieri Di Sua Scuola Raccolte Da Marcello Oretti Bolognese Parte VII; Biblioteca Comunale dell’Archiginnasio: Bologna, Italy, 1846; Volume B129. [Google Scholar]

- Amorini, A.B. Vite de’ Pittori ed Artefici Bolognesi; Forni: Bologna, Italy, 1843; Volume II, ISBN 978-88-271-1966-2. [Google Scholar]

- Riccomini, E. Ordine e Vaghezza. La Scultura in Emilia nell’età Barocca; Zanichelli: Bologna, Italy, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandretti, A. Brunelli, Gabriele. In Dizionario Biografico Degli Italiani; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana: Rome, Italy, 1972; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Favale, C.; Grillini, G.C.; Valdrè, G. Il Gesso Alabastrino Nella Statua Del Salvator Mundi Di Gabriele Brunelli: Geologia e Mineralogia Di Manufatti Artistici in Emilia-Romagna. In Torricelliana. Bollettino della Società Torricelliana di Scienze e Lettere di Faenza; Edit Faenza: Faenza, Itay, 2024–2025; Volume 75–76. [Google Scholar]

- UNI EN 16085:2012; Conservation of Cultural Property. Methodology for Sampling from Materials of Cultural Property. General Rules. UNI (Unificazione Italiana): Bologna, Italy, 2012.

- Doebelin, N.; Kleeberg, R. Profex: A Graphical User Interface for the Rietveld Refinement Program BGMN. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2015, 48, 1573–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, J.; Kleeberg, R. Rietveld Analysis of Disordered Layer Silicates. Mater. Sci. Forum 1998, 278–281, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombicci, L. Montagne e Vallate Del Territorio Di Bologna: Cenni Sulla Oro-Idrografia, Geologia, Litologia e Mineralogia Dell’Appennino Bolognese e Sue Dipendenze: Con Una Carta Geologica e Una Carta Schematica Di Oro-Idrografia; Tipografia Fava e Garagnani: Bologna, Italy, 1882. [Google Scholar]

- Tomba, A.M. I Gessi Saccaroidi Di Sassatello e Pieve Di Gesso (Vallata Del Santerno). Rend. Soc. Min. Ital. 1957, XIII, 374–389. [Google Scholar]

- Scicli, A. L’attività Estrattiva e Le Risorse Minerarie Della Regione Emilia-Romagna; Poligrafo Artioli: Modena, Italy, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Piastra, S. L’estrazione Del Gesso Nella Romagna Orientale Tra Passato e Presente. In Gessi e Solfi Della Romagna Orientale; Memorie dell’Istituto Italiano di Speleologia: Bologna, Italy, 2016; Volume 31, p. 527. [Google Scholar]

- AlunnoRossetti, V.; Laurenzi Tabasso, M. Distribuzione Degli Ossalati Di Calcio Mono e 2,25 Idrato Nelle Alterazione Delle Pietre Di Monumenti Esposti All’aperto. In Problemi di Conservazione; Compositori: Bologna, Italy, 1973; pp. 375–386. [Google Scholar]

- Couty, R.; Velde, B.; Besson, J.M. Raman Spectra of Gypsum under Pressure. Phys. Chem. Miner. 1983, 10, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saksena, B.D. Raman Spectrum of Gypsum. Proc. Indian Acad. Sci.—Sect. A 1941, 13, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chio, C.; Sharma, S.; Muenow, D. Micro-Raman Studies of Gypsum in the Temperature Range between 9 K and 373 K. Am. Mineral. 2004, 89, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministero della Cultura. Soprintendenza Speciale di Roma Madonna Del Parto. Un Bio Restauro; Ministero della Cultura: Rome, Italy, 2023.

- Wiley, J.H.; Atalla, R.H. Band Assignments in the Raman Spectra of Celluloses. Carbohydr. Res. 1987, 160, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrales, L.; Abidi, N.; Manciu, F. Characterization of Developing Cotton Fibers by Confocal Raman Microscopy. Fibers 2014, 2, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Position of the Sampling | Analyses |

|---|---|---|

| A | Yellowish-white sherd from a fracture of the dress | XRPD/FE-ESEM-EDS/Raman |

| B | Grey sherd from a lacuna of the base | XRPD/Raman |

| C | White sherd from the right foot | XRPD/FE-ESEM-EDS/Raman |

| D | Darkened sherd from the internal fold of the dress | XRPD/FE-ESEM-EDS/Raman |

| E | Black deposits from a horizontal dress fold | XRPD/Raman |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Favale, C.; Ulian, G.; Grillini, G.C.; Moro, D.; Valdrè, G. Characterization and Analysis of Gypsum Alabaster Constituting the “Santissimo Salvatore” Statue by Gabriele Brunelli (Bologna, 1615–1682). Heritage 2025, 8, 543. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120543

Favale C, Ulian G, Grillini GC, Moro D, Valdrè G. Characterization and Analysis of Gypsum Alabaster Constituting the “Santissimo Salvatore” Statue by Gabriele Brunelli (Bologna, 1615–1682). Heritage. 2025; 8(12):543. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120543

Chicago/Turabian StyleFavale, Camilla, Gianfranco Ulian, Gian Carlo Grillini, Daniele Moro, and Giovanni Valdrè. 2025. "Characterization and Analysis of Gypsum Alabaster Constituting the “Santissimo Salvatore” Statue by Gabriele Brunelli (Bologna, 1615–1682)" Heritage 8, no. 12: 543. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120543

APA StyleFavale, C., Ulian, G., Grillini, G. C., Moro, D., & Valdrè, G. (2025). Characterization and Analysis of Gypsum Alabaster Constituting the “Santissimo Salvatore” Statue by Gabriele Brunelli (Bologna, 1615–1682). Heritage, 8(12), 543. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120543