Monstrous Figurines, of BMAC, and the Dragon Myth: From a Meteoritic Headband to Rig Veda Mythology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. A Short Presentation of the Two Specimens

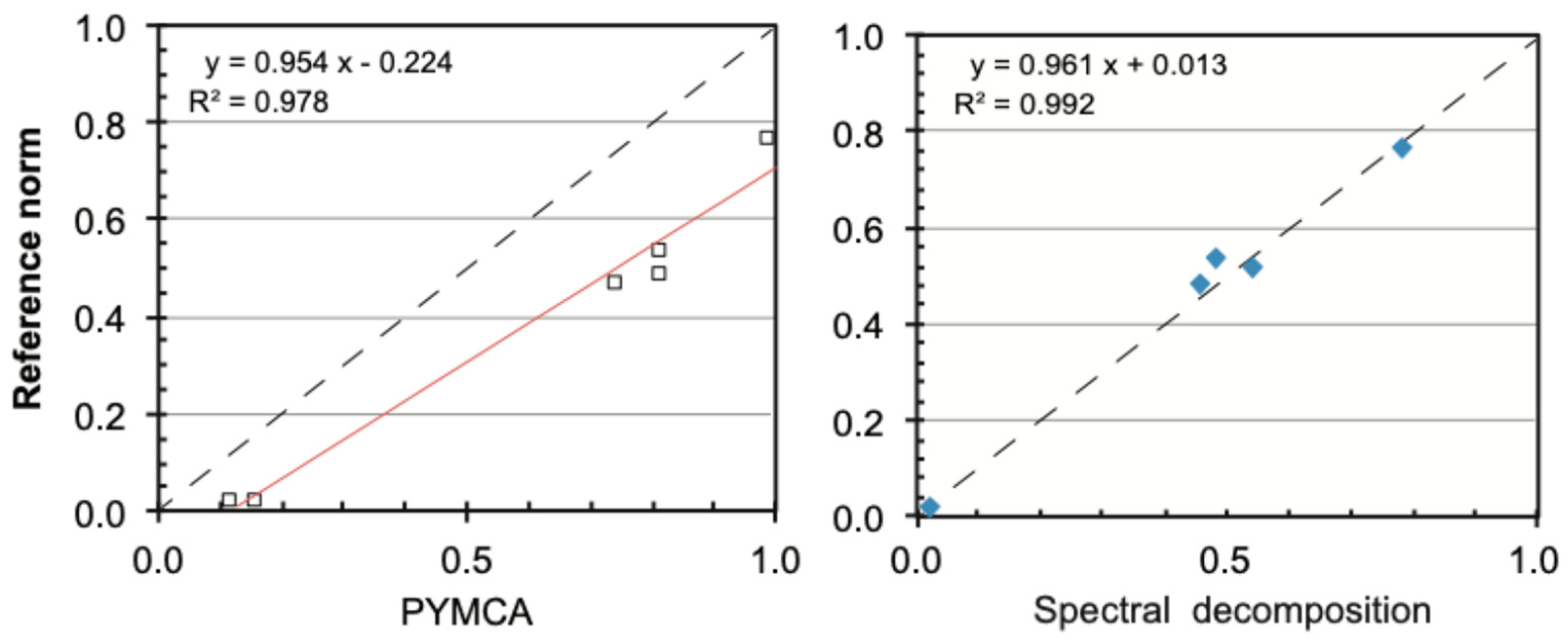

2.2. Analytical Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

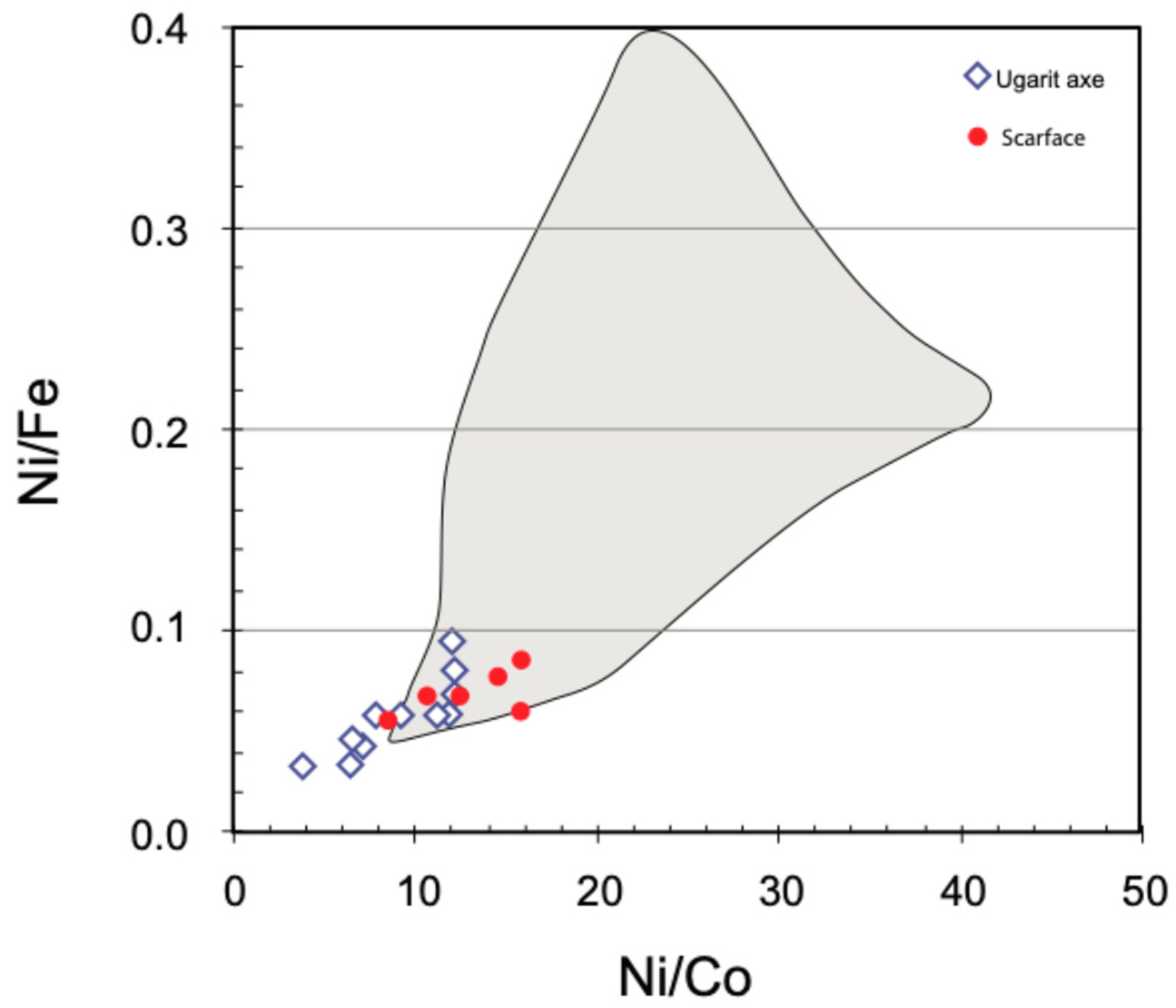

4.1. The Metal

4.2. The Significance of the Iron Headband

4.3. The Relationship with the Indo-European Myth of the Dragon (See Appendix B OSM)

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Co Analysis

| Si | S | K | Ca | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | As | Cd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cape York | 1.41 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 90.38 | 0.80 | 7.11 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| 0.88 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 91.43 | 0.82 | 6.50 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |

| 1.16 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 91.18 | 0.78 | 6.51 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |

| 1.15 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 91.00 | 0.80 | 6.70 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| Coahuila | 1.24 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 92.33 | 0.81 | 5.30 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| 0.76 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 93.10 | 0.76 | 5.08 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | |

| 0.76 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 93.05 | 0.65 | 5.29 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.04 | |

| 0.92 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 92.83 | 0.74 | 5.22 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| Hoba | 0.89 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 81.72 | 0.97 | 16.21 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| 0.56 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 81.97 | 0.96 | 16.20 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| 0.78 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 81.76 | 0.98 | 16.18 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |

| 0.74 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 81.81 | 0.97 | 16.20 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |

| JFP | 0.80 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 90.55 | 0.88 | 7.22 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| 1.82 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 89.86 | 0.75 | 7.26 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | |

| 0.48 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 90.36 | 0.77 | 7.95 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |

| 1.03 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 90.25 | 0.80 | 7.48 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | |

| ROC17 | 1.39 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 81.38 | 0.29 | 16.61 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| 1.88 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 80.96 | 0.28 | 16.62 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | |

| 0.96 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 81.95 | 0.16 | 16.66 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |

| 1.41 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 81.43 | 0.24 | 16.63 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |

| ROC30 | 0.61 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 68.50 | 0.18 | 30.47 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| 0.66 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 68.18 | 0.25 | 30.56 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| 1.34 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 68.25 | 0.20 | 29.79 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | |

| 0.87 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 68.31 | 0.21 | 30.27 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Fe | Co | Ni | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JFP | A | 91.85 | 0.55 | 7.59 |

| B | 91.78 | 0.51 | 7.71 | |

| C | 91.14 | 0.52 | 8.34 | |

| Mean | 91.59 | 0.53 | 7.88 | |

| sigma | 0.39 | 0.02 | 0.40 | |

| Ref | 91.27 | 0.54 | 8.19 | |

| ROC17 | 1 | 82.49 | 0.19 | 17.32 |

| 2 | 82.50 | 0.14 | 17.36 | |

| 3 | 82.58 | 0.11 | 17.32 | |

| Mean | 82.52 | 0.14 | 17.33 | |

| sigma | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.02 | |

| Ref | 82.91 | 0.11 | 16.98 | |

| ROC30 | 1 | 68.76 | 0.09 | 31.16 |

| 2 | 68.64 | 0.10 | 31.26 | |

| 3 | 68.73 | 0.10 | 31.17 | |

| Mean | 68.71 | 0.09 | 31.20 | |

| sigma | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.05 | |

| Ref | 69.90 | 0.15 | 29.96 | |

| Hoba | 1 | 82.46 | 0.72 | 16.82 |

| 2 | 82.46 | 0.71 | 16.82 | |

| 3 | 82.50 | 0.71 | 16.80 | |

| Mean | 82.47 | 0.71 | 16.81 | |

| sigma | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| Ref | 83.07 | 0.79 | 16.14 | |

| Coahuila | 1 | 94.03 | 0.44 | 5.53 |

| 2 | 94.19 | 0.46 | 5.35 | |

| 3 | 93.89 | 0.48 | 5.63 | |

| 4 | 93.99 | 0.46 | 5.55 | |

| 5 | 93.98 | 0.46 | 5.57 | |

| 6 | 93.90 | 0.44 | 5.66 | |

| Mean | 93.99 | 0.46 | 5.55 | |

| sigma | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.11 | |

| Ref | 93.98 | 0.46 | 5.56 | |

| Cape York | 1 | 92.00 | 0.53 | 7.48 |

| 2 | 92.61 | 0.56 | 6.83 | |

| 3 | 92.76 | 0.47 | 6.77 | |

| 4 | 91.65 | 0.45 | 7.90 | |

| 5 | 91.49 | 0.48 | 8.03 | |

| 6 | 91.03 | 0.47 | 8.50 | |

| 7 | 92.49 | 0.52 | 6.99 | |

| sigma | 0.67 | 0.04 | 0.69 | |

| Mean | 92.00 | 0.50 | 7.50 | |

| Ref | 91.90 | 0.49 | 7.61 |

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. The Dragon Myth

Appendix B.2. The Indo-European Myth and the Relationship with the Oxus Culture

Appendix B.3. The Slaying/Splitting of the Dragon

“The Oxus Civilization scheme, representing the cycles of nature and life, is notably different from the usual and well-known interpretive schemes of the Mesopotamian, Indus or Avestan mythologies, but certainly related to the Iranian Elamite artistic language (forms and style) if not beliefs, and deeply rooted in Bactria–Margiana. In this respect, the symbolic system of the Oxus Civilization is an original expression of a more general Eurasian mythological universe of very ancient origin.”

References

- Ghirshman, R. Statuettes Archaïques du Fars (Iran). Artibus Asiae 1963, 26, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francfort, H.P. The Central Asian Dimension of the Symbolic System in Bactria and Margiana. Antiquity 1994, 68, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarianidi, V.I. Togolok 21, an Indo-Iranian Temple in the Karakum. Bull. Asia Inst. 1990, 4, 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Jambon, A. Bronze Age Iron: Meteoritic or not? A Chemical Strategy. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2017, 88C, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calligaro, T. (Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France, Paris, France). Personal communication, 2025.

- Waldbaum, J. The first archaeological appearance of lron and the transition to the iron age. In The Coming of the Age of Iron; Wertime, T.A., Muhly, D., Eds.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 1980; pp. 69–98. [Google Scholar]

- Waldbaum, J.C. The coming of iron in the eastern Mediterranean: Thirty years of archaeological and technological research in the archaeometallurgy of the Asian World. In MASCA Research Papers in Science and Archaeology; Pigott, V.C., Ed.; Museum Applied Science Center for Archaeology: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1999; Volume 16, pp. 27–57. [Google Scholar]

- Jean, E. Le fer chez les Hittites: Un Bilan des Données Archéologiques. Mediterr. Archaeol. 2001, 14, 163–188. [Google Scholar]

- Yalçın, Ü. Early iron metallurgy in Anatolia. Anatol. Stud. 1999, 49, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, A. Le Balafré, un dragon-serpent de la civilisation de l’Oxus. In Actualité du Département des Antiquités Orientales; Le Louvre: Paris, France, 2006; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Sole, V.A.; Papillon, E.; Cotte, M.; Walter, P.; Susini, J. A multiplatform code for the analysis of energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectra. Spectrochim. Acta B 2007, 62, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambon, A.; Bielińska, G.; Kosiński, M.; Wieczorek-Szmal, M.; Miśta-Jakubowska, E.; Tarasiuk, J.; Dzięgielewski, K. Heavenly Metal for the Commoners: Meteoritic Irons from the Early Iron Age Cemeteries in Częstochowa (Poland). J. Archeol. Sci. Rep. 2025, 62, 104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almansa Vilatoro, V.; Newman, R.; Jambon, A. An Ancient Egyptian Meteoritic Iron on Khufu’s Magic Knife from Giza (c. 2550 BCE). Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 2025; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, J.I. The Formation of the Kamacite Phase in Metallic Meteorites. J. Geophys. Res. 1965, 70, 6223–6232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Tyldesley, J.; Lowe, T.; Withers, P.J.; Grady, M.M. Analysis of a prehistoric Egyptian iron bead with implications for the use and perception of meteorite iron in ancient Egypt. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 2013, 48, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehren, T.; Belgya, T.; Jambon, A.; Káli, G.; Kasztovszky, Z.; Kis, Z.; Kovács, I.; Maróti, B.; Martinón-Torres, M.; Miniaci, G.; et al. 5000 years old Egyptian iron beads made from hammered meteoritic iron. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 40, 4785–4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C. How to kill a dragon in Indo-European. In Studies in Memory of Warren Cowgill (1929–1985); Watkins, C., Ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1987; pp. 270–299. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, C. How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mallory, J.P. A European perspective on Indo-Europeans in Asia. In The Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Peoples of Eastern Central Asia; Mair, V.H., Ed.; The Institute for the Study of Man: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; Volume I, pp. 175–201. [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan, V.M.; Patterson, N.; Moorjani, P.; Rohland, N.; Bernardos, R.; Mallick, S.; Lazaridis, I.; Nakatsuka, N.; Olalde, I.; Lipson, M.; et al. The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia. Science 2019, 365, eaat7487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinault, G.-J. Contacts religieux et culturels des Indo-Iraniens avec la Civilisation de l’Oxus. In Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres; Persée: Lyon, France, 2005; pp. 213–257. [Google Scholar]

- Lubotsky, A. The Indo-Iranian Substratum. In Early Contacts Between Uralic and Indo-European: Linguistic and Archaeological Considérations, Proceedings of the International Symposium, Helsinki, Finland, 8–10 January 1999; Carpelan, C., Parpola, A., Koskikallio, P., Eds.; Mémoires De La Société Finno-Ougrienne: Helsinki, Finland, 2001; Volume 422, pp. 301–317. [Google Scholar]

- Vidale, M. Treasures from the Oxus: The Art and Civilization of Central Asia; Tauris, I.B., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Slade, B. How (exactly) to slay a dragon in Indo-European? Hist. Sprachforsch. 2010, 121, 3–53. [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald, V.F. Handbook of Iron Meteorites. Their History, Distribution, Composition and Structure 1–3; State University, Center for Meteorite Studies: Tempe, AZ, USA; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1975; Available online: https://evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/handle/10524/33750 (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- Van Buren, E.D. The Dragon in Ancient Mesopotamia. Orientalia 1946, 15, 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Caubet, A. Myths and Gods in the Oxus Civilization. In The World of the Oxus Civilization; Lyonnet, B., Dubova, N.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Sarianidi, V.I. Die Kunst des Alten Afghanistan; VEB EA Seemann Verlag: Leipzig, Germany, 1986; pp. 50–72. [Google Scholar]

- Francfort, H.P. La civilisation de l’Asie Centrale à l’Âge du Bronze et à l’Âge du Fer. In Catalogue De l’Indus à l’Oxus. Archéologie de l’Asie Centrale; Association IMAGO-Musée De Lattes: Montpellier, France, 2003; pp. 29–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hiebert, F.T. South Asia from a Central Asian perspective. In The lndo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia; Edosy, G., Ed.; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 192–205. [Google Scholar]

- Parpola, A. Formation of the Aryan branch of Indo-European. In Archaeology and Language 1: Theoretical and Methodological Orientations; Blench, R., Spriggs, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cerasetti, B. Who interacted with whom? Redefining the interaction between BMAC people and mobile pastoralists in Bronze Age southern Turkmenistan. In The World of the Oxus Civilization; Lyonnet, B., Dubova, N.A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 487–495. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, G.D. An Introduction to Hinduism; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; 341p. [Google Scholar]

- Witzel, M. Linguistic Evidence for Cultural Exchange in Prehistoric Central Asia; Sino-Platonic Papers 129; University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2003; pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, D. The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, H.-P. Bṛhaspati und Indra; Harassowitz: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, H. The purpose of Rgvedic ritual. In Inside the Texts, Beyond the Texts: New Approaches to the Study of the Vedas; Witzel, M., Ed.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997; pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Witzel, M. The Ṛgvedic religious system and its Central Asian and Hindukush antecedents. In The Vedas: Texts, Language and Ritual; Griffiths, A., Houben, J.E.M., Eds.; Forsten: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 581–636. [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste, E.; Renou, L. Vrtra et Vroragna/Etude de Mythologie Indo-Iranienne; Imprimerie Nationale: Paris, France, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Ligabue, G.; Salvatori, S. Bactria: An Ancient Oasis Civilisation from the Sands of Afghanistan; Ligabue, G., Salvatori, S., Eds.; Erizzo: Venice, Italy, 1989; 187p. [Google Scholar]

- Amiet, P. L’âge des échanges inter-iraniens 3500–1700 avant J.-C. In Notes et Documents des Musées de France 11; Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux: Paris, France, 1986; 332p. [Google Scholar]

- Miroschedji, P.D. Le dieu Elamite au serpent et aux eaux jaillissantes. Iran. Antiq. 1981, 16, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Dieny, J.-P. Le Symbolisme du dragon dans la Chine antique. In Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions; College de France, Institut des Hautes Etudes Chinoises: Paris, France, 1989; Volume 67/2, p. 259. [Google Scholar]

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Si | 7.72 | 5.59 | 11.43 | 11.49 | 12.13 |

| S | 0.74 | 1.12 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.75 |

| K | 0.49 | 0.54 | 1.43 | 1.39 | 1.30 |

| Ca | 2.92 | 9.18 | 1.77 | 2.05 | 2.33 |

| Ti | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.21 |

| V | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.32 |

| Cr | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Mn | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| Fe | 81.82 | 76.48 | 78.85 | 78.00 | 78.17 |

| Co | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.37 |

| Ni | 4.87 | 5.15 | 3.77 | 4.11 | 3.46 |

| Cu | 0.30 | 0.65 | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.36 |

| Zn | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.22 |

| As | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.14 |

| Total | 99.95 | 99.93 | 99.95 | 99.95 | 99.95 |

| Matrix | A | B | C | D | E | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Si | 52.59 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| S | 4.72 | 0.05 | 0.69 | −0.20 | −0.14 | −0.43 | −0.01 |

| K | 6.18 | −0.49 | −0.13 | 0.11 | 0.05 | −0.16 | −0.13 |

| Ca | 9.22 | 1.83 | 9.18 | −0.30 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 2.20 |

| Ti | 1.08 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.00 |

| V | 1.33 | 0.07 | 0.16 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Cr | 0.29 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Mn | 0.61 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| Fe | 16.82 | 93.00 | 83.57 | 96.08 | 95.11 | 96.57 | 92.87 |

| Co | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.39 |

| Ni | 0.00 | 5.70 | 5.77 | 4.82 | 5.26 | 4.49 | 5.21 |

| Cu | 2.31 | −0.05 | 0.45 | −0.13 | −0.07 | −0.23 | −0.01 |

| Zn | 1.11 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.02 |

| As | 0.67 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Cd | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| SUM | 97.14 | 100.49 | 100.34 | 100.79 | 100.80 | 100.86 | 100.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jambon, A. Monstrous Figurines, of BMAC, and the Dragon Myth: From a Meteoritic Headband to Rig Veda Mythology. Heritage 2025, 8, 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120539

Jambon A. Monstrous Figurines, of BMAC, and the Dragon Myth: From a Meteoritic Headband to Rig Veda Mythology. Heritage. 2025; 8(12):539. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120539

Chicago/Turabian StyleJambon, Albert. 2025. "Monstrous Figurines, of BMAC, and the Dragon Myth: From a Meteoritic Headband to Rig Veda Mythology" Heritage 8, no. 12: 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120539

APA StyleJambon, A. (2025). Monstrous Figurines, of BMAC, and the Dragon Myth: From a Meteoritic Headband to Rig Veda Mythology. Heritage, 8(12), 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120539