Virtual Museums as Meaning-Modeling Systems in Digital Heritage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Forms of Meaning in the Virtual Museum

“…they are mediated by the innumerable forms of meaning created and conveyed by the words, drawings, artifacts and other models of the world that people make and use routinely. The world of human beings is a de facto world of meaning-bearing forms.”[28]

2.2. Meaning Generation, Audience Agency, and Internal Insufficiency

“…human semiosis is dependent on logical computations that automatically generate ‘meanings’ in the same way that computers operate. With some sort of external input (stimuli) perceived from Umwelten, semiosis (sign activity) will take care of the rest of the operations. In some cases, such as introspection and meditation, there is even no need for such input, as the attention will be on whatever is cognized in the Innenwelten”.[65]

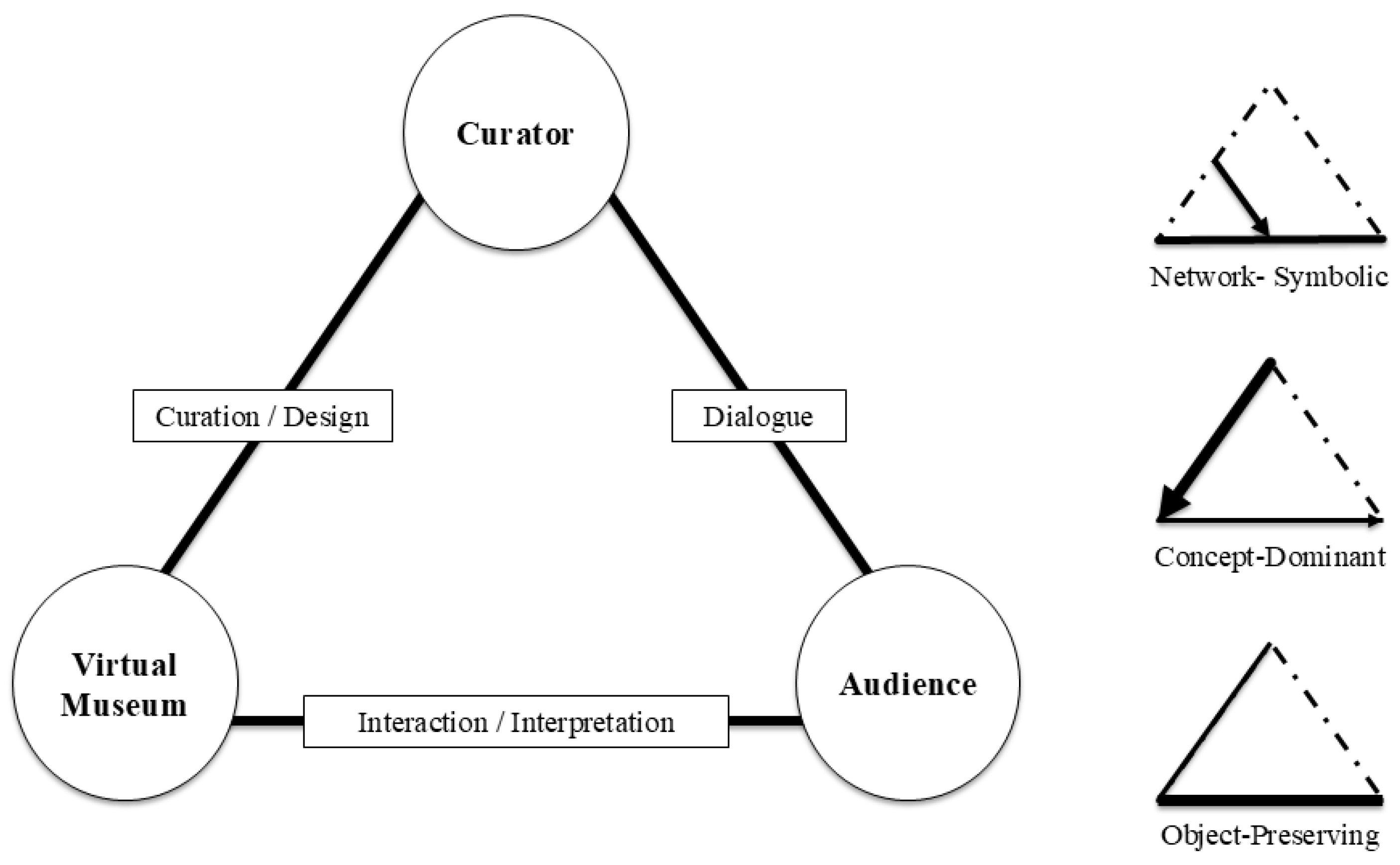

- The virtual museum system itself occupies a central, intermediary position as a represented and constructed virtual entity (the “mediator of mediators”).

- 2.

- The curator’s own cognition, i.e., the curator as a subject with knowledge, biases, and intentions (a knowledge level that informs everything they do).

- 3.

- The curator’s conceptualization of the virtual museum—how the curator imagines and models the virtual platform as a medium (including its capabilities and constraints).

- 4.

- The curator’s conceptualization of the audience—assumptions and models about who the viewers are, what they know, and how they might interpret the content.

- 5.

- The audience’s self-concept—the viewer’s pre-existing cognitive models, prior knowledge and expectations (which they bring into the museum experience).

- 6.

- The audience’s conceptualization of the virtual museum—how the viewer understands the platform/interface and its authority or reliability (e.g., do they treat it like a real museum? a game? an educational tool?).

- 7.

- The audience’s modeling of other subjects—how the viewer perceives and models the curator (or authors) and potentially other virtual visitors or commentators, mediated by the virtual museum (for instance, through interactive features or social sharing).

2.3. Subject–Object Critique: Non-Identity and the Dialectics of Meaning

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Selection

3.2. Coding Scheme: Modeling Levels and Forms

3.3. Quantitative Metrics

- Abstraction Ratio (AR): A measure of the degree of conceptual abstraction in the content. We operationalized AR as the proportion of modeling instances coded at the tertiary level out of all instances in a case. This ratio indicates how much the virtual museum relies on symbolic or highly abstract modeling (e.g., overarching narratives, gamified experiences, conceptual metaphors) as opposed to more direct or contextual representation. A higher AR suggests a more concept-dominant approach, whereas a lower AR suggests content stays closer to direct representation of objects or straightforward context.

- Connectivity Ratio (CR): A measure of how networked or interlinked the content is. We defined CR as the proportion of instances coded as cohesive or connective forms out of all instances. These two forms (cohesive and connective) both deal with linking multiple elements: cohesive forms provide systematic structure, like unified interfaces or consistent design languages; and connective forms explicitly link disparate elements, like interactive links or relational metadata. A higher CR indicates a highly interconnected meaning system, the virtual museum encourages nonlinear exploration and synthesis (a “network-symbolic” quality), whereas a lower CR indicates a more discrete, isolated presentation of content.

- Object Primacy Score (OPS): A measure devised to capture the emphasis on original artifacts or direct object representation. We calculated OPS as the proportion of instances at the primary modeling level (iconic representations) out of all instances. This serves as an indicator of how strongly the virtual museum foregrounds authentic objects or faithful reproductions thereof, relative to more interpretive content. A high OPS means the virtual museum is largely object-preserving (the bulk of content is direct depiction of artifacts or tangible elements), whereas a low OPS means the virtual museum gives primacy to concepts, context, or narrative over raw object display. In Adorno’s terms, OPS reflects the degree of “object precedence,” how much the real object is allowed to “speak for itself” in the virtual space.

4. Dialectical Patterns in Virtual Museum Experience Meaning Construction

4.1. Case Descriptions and Coding Results

4.1.1. Case A: British Museum Bronze Age VR (UK)

4.1.2. Case B: Museum of the World (British Museum/Google)

4.1.3. Case C: Digital Beijing Central Axis (China)

4.1.4. Case D: Virtual Angkor (Cambodia)

4.1.5. Case E: National Museum of the D.R. Congo Virtual Tour

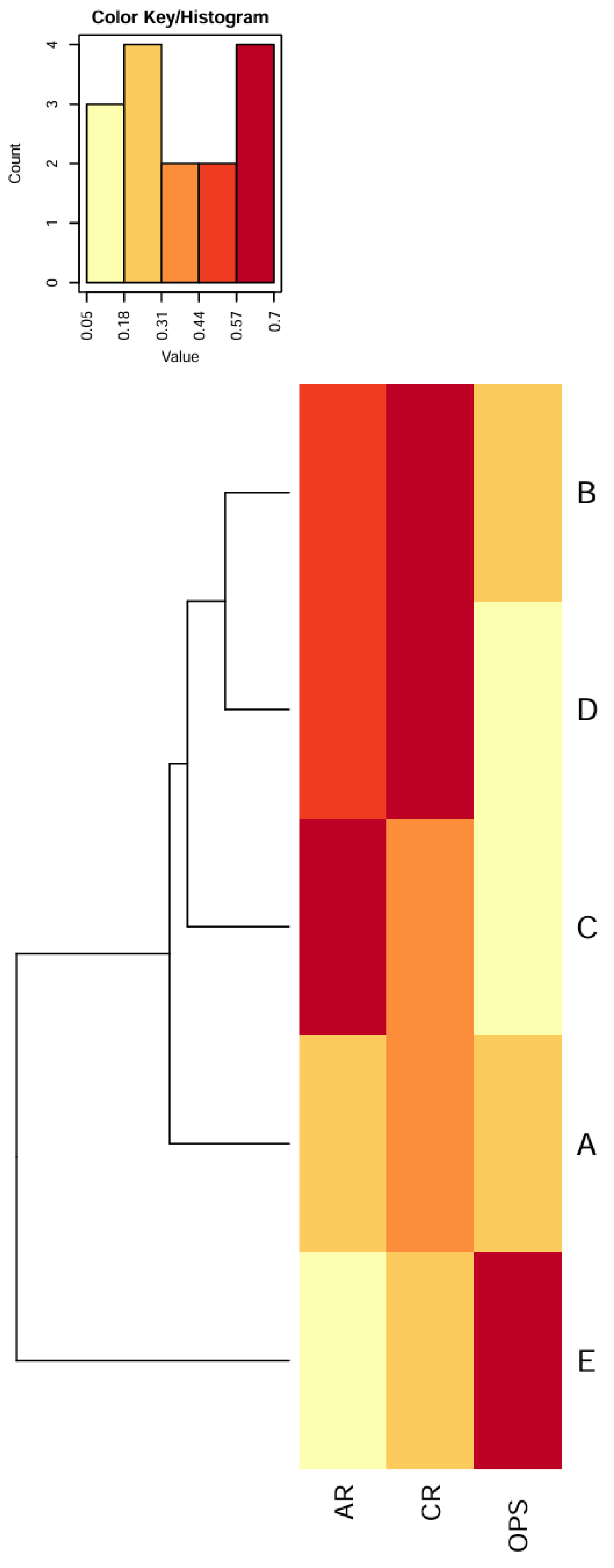

4.2. Typological Clustering of Meaning Systems

- Network-Symbolic Museums: These are characterized by high connectivity and considerable symbolic abstraction, while still incorporating a mix of object representation. Cases B (Museum of the World) clearly falls here, and Case A (BM VR) shows some affinity albeit with lower abstraction. In these systems, knowledge is constructed through a network of relationships; the meaning emerges from how elements are connected across time/space/themes rather than from the elements alone. The “symbolic” aspect refers to the heavy use of tertiary modeling, conceptual frameworks like timelines, global maps, or narrative metaphors shape the experience. The presence of real artifacts is still important, but they are embedded in a rich matrix of links and conceptual overlays. This type aligns with an interactive, exploratory paradigm. It resonates with Adorno’s idea of a “constellation” of concepts around an object rather than a single defining idea, here the object’s meaning is approached via multiple connections, acknowledging it cannot be reduced to one context. However, the risk is that the network of references itself might become reified; users might hop from object to object, skimming meanings, possibly treating the whole network as an infotainment web.

- Concept-Dominant Museums: These feature very high abstraction and typically moderate connectivity, with low emphasis on original objects. The hierarchical clustering pairs D with B at the nearest-neighbor level, with C joining subsequently; this as a prompt for interpretation, not a final classifier. This reading distinguishes local proximity in the dendrogram from conceptual patterning across all three ratios, which is why we treat B-D as nearest neighbors while interpreting C-D as the clearest exemplars of the high-abstraction profile. Here, a unifying concept or narrative dominates the design, be it the “ideal city” or an immersive historical story. The virtual museum becomes a narrative or simulation environment. The actual artifacts or factual authenticity may be secondary; they serve the story more than the story serves them. Connectivity may be present (Virtual Angkor allows exploration), but often within a controlled narrative flow. This type is akin to a virtual exhibit as a coherent story or theme. The advantage is a strongly coherent interpretive message and potentially deep engagement in one narrative. However, from a dialectical perspective, this runs the risk of what Adorno would call identity-thinking: the concept (the narrative of Angkor, or the curatorial thesis) subsumes the object completely. The object’s non-identity, the parts of the artifact’s meaning that do not fit the story are suppressed. Instrumental reason is at play: technology is used to enforce a certain interpretation, albeit for education or entertainment. Such experiences might be very engaging, but they can sacrifice the open-ended, critical engagement that museums traditionally aspire to. The missing element is the object’s ability to surprise or contradict the narrative.

- Object-Preserving Museums: These are marked by low abstraction, low connectivity, and high object primacy. Case E (DRC virtual tour) represents this cluster, and to an extent some traditional online collections or simple museum websites would as well. The design philosophy is to showcase objects with minimal interpretation beyond what a physical museum would provide. The virtual museum acts almost as a high-fidelity mirror of a real museum or collection database. Users can examine artifacts, often getting closer via digital zoom than in person, and read catalog information, but they are not led far beyond that. It resists imposing too much conceptual structure, thereby reducing the chance of misrepresenting the object. It also aligns with MST at the primary level, focusing on iconic representations. The experience can be akin to walking through a museum quietly, valuable for access, but potentially overwhelming or under-explained for those without prior knowledge. The dialectical shortcoming here, from an Adornian view, could be that it leaves the subject relatively passive, or conversely, it leaves meaning entirely up to the subject’s own background, if the museum doesn’t provide connections, the user might not make any new ones. This approach avoids the pitfalls of overt instrumentalization, but it may also miss opportunities to illuminate by context or to engage broader narratives that give objects significance.

4.3. Theoretical Interpretation: MST Modeling Meets Adorno’s Dialectics

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Empirical Findings and MST Validation

5.3. Non-Identity in Digital Cultural Spaces

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. MST-Based Coding Schema for Virtual Museum Content Analysis

Appendix A.1. Overview of the Coding Matrix

| Singularized Modeling | Composite Modeling | Cohesive Modeling | Connective Modeling | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary modeling system (PMS) | iconic sign | iconic text | iconic code | Metaform |

| Secondary modeling system (SMS) | secondary singularized modeling (extensional modeling, indicational modeling) | secondary composite modeling | secondary cohesive modeling | Meta-metaform |

| Tertiary modeling system (TMS) | Tertiary singularized modeling (symbol) | Tertiary composite modeling | Tertiary cohesive modeling | Meta-symbol |

| Level | Form | Category | Ratio Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary modeling system (PMS) | Singularized Modeling | Primary-Singularized | OPS |

| Primary modeling system (PMS) | Composite Modeling | Primary-Composite | OPS |

| Primary modeling system (PMS) | Cohesive Modeling | Primary-Cohesive | OPS, CR |

| Primary modeling system (PMS) | Connective Modeling | Primary-Connective | OPS, CR |

| Secondary modeling system (SMS) | Singularized Modeling | Secondary-Singularized | none |

| Secondary modeling system (SMS) | Composite Modeling | Secondary-Composite | none |

| Secondary modeling system (SMS) | Cohesive Modeling | Secondary-Cohesive | CR |

| Secondary modeling system (SMS) | Connective Modeling | Secondary-Connective | CR |

| Tertiary modeling system (TMS) | Singularized Modeling | Tertiary-Singularized | AR |

| Tertiary modeling system (TMS) | Composite Modeling | Tertiary-Composite | AR |

| Tertiary modeling system (TMS) | Cohesive Modeling | Tertiary-Cohesive | AR, CR |

| Tertiary modeling system (TMS) | Connective Modeling | Tertiary-Connective | AR, CR |

Appendix A.2. Primary Modeling System

- Iconic Sign (Primary-Singularized): Individual iconic representations that function as discrete units of meaning. In virtual museums, this category includes standalone photographs of artifacts, individual 3D scans of objects presented in isolation, single architectural elements reproduced digitally, and discrete visual representations of collection items. For example, in the DRC Museum virtual tour, each high-resolution image of an individual artifact viewed through the panoramic interface constitutes an iconic sign.

- Iconic Text (Primary-Composite): Combinations of iconic elements that create compound representations while maintaining direct resemblance to reality. This category encompasses virtual gallery spaces showing multiple objects together, panoramic views combining multiple architectural elements, composite 3D scenes recreating historical spaces, and grouped artifact displays maintaining spatial relationships. The British Museum VR’s Bronze Age roundhouse, combining multiple authentic 3D object scans within a reconstructed dwelling, exemplifies iconic text.

- Iconic Code (Primary-Cohesive): Systematic frameworks for organizing and presenting iconic content according to consistent rules. This includes standardized 3D modeling conventions, uniform photographic documentation systems, consistent virtual space navigation protocols, and systematic visual representation standards. The 360-degree panoramic system used throughout the DRC Museum tour represents an iconic code, providing a cohesive framework for experiencing the physical museum space.

- Metaform (Primary-Connective): Linking mechanisms that create relationships between discrete iconic representations. Examples include visual comparison tools for artifacts, morphological linking systems showing object evolution, visual genealogies of artistic styles, and image-based search functions. When the Museum of the World allows visual comparison between artifacts from different cultures through side-by-side display, it employs metaform structures.

Appendix A.3. Secondary Modeling System

- Secondary Singularized Modeling (Extensional/Indicational): Individual contextual elements that provide interpretive information for specific objects or spaces. This category includes individual object labels and descriptions, single historical contextualization notes, discrete provenance records, and standalone interpretive texts. In Virtual Angkor, individual explanatory panels describing specific architectural features represent secondary singularized modeling.

- Secondary Composite Modeling: Grouped contextual elements that create interpretive frameworks through combination. Examples include thematic exhibition narratives combining multiple objects, historical timelines integrating various artifacts, comparative cultural analyses, and multi-object storytelling sequences. The British Museum VR’s combination of curatorial commentary with multiple Bronze Age objects creates secondary composite modeling.

- Secondary Cohesive Modeling: Overarching interpretive systems that provide consistent contextual frameworks throughout the virtual museum. This encompasses unified curatorial voices across exhibitions, consistent historical periodization schemes, standardized educational frameworks, and systematic interpretive methodologies. Virtual Angkor’s consistent approach to explaining Khmer architectural principles across different temple sites demonstrates secondary cohesive modeling.

- Meta-metaform (Secondary-Connective): Complex linking systems that connect interpretive contexts across different content areas. This includes thematic pathways linking diverse cultural contexts, comparative interpretation tools, cross-cultural analytical frameworks, and networked scholarly annotations. The Museum of the World’s ability to connect objects through interpretive themes like “power” or “belief” across cultures exemplifies meta-metaform structures.

Appendix A.4. Tertiary Modeling System

Appendix A.5. Application Guidelines

Appendix B. Glossary of Key Terms

- Abstraction Ratio (AR): The proportion of content instances coded at the tertiary modeling level (AR = (tertiary instances)/(total instances)) within a virtual museum, indicating the degree of conceptual and symbolic representation relative to more concrete representational modes.

- Cohesive Form: A model form that provides systematic organizational frameworks governing how content is structured and accessed within the virtual museum environment.

- Composite Form: A model form combining multiple elements to create emergent meanings through the relationships between components.

- Connectivity Ratio (CR): The proportion of content instances exhibiting cohesive or connective forms, measuring the degree of systematic organization and interlinking (CR = (cohesive + connective)/(total instances)) within the virtual museum.

- Connective Form: A model form creating explicit links between disparate elements, enabling networked exploration and relationship discovery.

- Dialectical Mediation: The dynamic process through which meaning emerges from the interaction between subjects and objects, rather than being determined by either alone.

- Extensionality Principle: MST’s principle that complex models develop from simpler ones, with higher-level modeling systems building upon and extending lower-level systems.

- Iconic Code: The primary-cohesive category representing systematic frameworks for organizing direct representational content.

- Iconic Sign: The primary-singularized category consisting of individual direct representations of real objects or spaces.

- Iconic Text: The primary-composite category combining multiple iconic elements into compound representations.

- Innenwelt: The internal cognitive world that subjects bring to interpretive encounters, shaping how external phenomena are modeled and understood.

- Instrumental Reason: The form of rationality oriented exclusively toward efficiency and control, potentially reducing cultural objects to mere means.

- Meaning-Modeling: The cognitive process through which subjects construct internal representations of external phenomena through systematic semiotic activity.

- Mediator of Mediators: The characterization of virtual museums as systems that mediate already-mediated cultural content, creating multiple interpretive layers.

- Meta-metaform: The secondary-connective category linking interpretive contexts across different content areas.

- Meta-symbol: The tertiary-connective category creating abstract conceptual links across symbolic content.

- Metaform: The primary-connective category establishing relationships between iconic representations.

- Modeling Systems Theory (MST): Sebeok’s framework proposing that humans understand reality through hierarchical modeling systems operating at primary, secondary, and tertiary levels.

- Non-identity: Adorno’s principle that conceptual representations never fully capture object reality, preserving an irreducible remainder.

- Object Primacy Score (OPS): The proportion of primary-level modeling instances, indicating emphasis on direct object representation (OPS = (primary instances)/(total instances)).

- Primary Modeling System (PMS): The foundational modeling level dealing with iconic, directly representational signs.

- Secondary Modeling System (SMS): The modeling level introducing indexical and contextual relationships extending primary representations.

- Semiosis: The process of sign production and interpretation generating meaning through modeling activity.

- Singularized Form: A model form consisting of discrete, independent units of meaning.

- Tertiary Modeling System (TMS): The highest modeling level involving symbolic and abstract conceptual representations.

- Umwelt: The species-specific perceptual world shaping interpretive possibilities, extended in MST to human cultural perception.

Appendix C. Methodological Notes

Appendix C.1. Sample Selection Criteria

Appendix C.2. Coding Procedures

Appendix C.3. Metric Calculation

Appendix C.4. Cluster Analysis

References

- White, M. Where is the Louvre? Space Cult. 1999, 2, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweibenz, W. Museum Exhibitions—The Real and the Virtual Ones: An Account of a Complex Relation. Uncommon Cult. 2012, 3, 38–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dallas, C. The Presence of Visitors in Virtual Museum Exhibitions. In Proceedings of the Numérisation, Lien Social, Lectures Colloquium, University of Crete, Rethymnon, Greece, 3–4 June 2004; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Witcomb, A. The Materiality of Virtual Technologies: A New Approach to Thinking about the Impact of Multimedia in Museums. In Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage; Cameron, F., Kenderdine, S., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Virtual Museums, F.; Becker, I.; Böhmer, O.; Gröne, R.; Günter, B.; Heinzelmann, R.; Kircher-Kannemann, A.; Mahmoudi, Y.; Römhild, J.; Simon, H.; et al. Virtual Museums—A Plea; Deutscher Kunstverlag (DKV): Berlin, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Schweibenz, W. The virtual museum: An overview of its origins, concepts, and terminology. Mus. Rev. 2019, 4, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Schweibenz, W. Wer sind die Besucher des virtuellen Museums und welche Interessen haben sie? (Who are the Visitors of the Virtual Museum and What are they Interested in?). i-com 2008, 7, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, W. The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. In A Museum Studies Approach to Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 226–243. [Google Scholar]

- Zeller, C. From Object to Information: The End of Collecting in the Digital Age. arcadia 2015, 50, 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, X.; Watanabe, I.; Ochiai, Y. A systematic review of digital transformation technologies in museum exhibition. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 161, 108407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvi, L.; Vermeeren, A.P.O.S. Digitally enriched museum experiences—what technology can do. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2024, 39, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, N. Digital Museum Objects and Memory: Postdigital Materiality, Aura and Value. Curator Mus. J. 2022, 65, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doering, Z.D. Strangers, guests, or clients? Visitor experiences in museums. In Museum Management and Marketing; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 331–344. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Zheng, Y. A Study of Visitor Interaction with Virtual Museum. In Proceedings of the HCI International 2022—Late Breaking Posters, Virtual Event, 26 June–1 July 2022; pp. 354–358. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-19679-9 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Schweibenz, W. The “Virtual Museum”: New Perspectives For Museums to Present Objects and Information Using the Internet as a Knowledge Base and Communication System. In Proceedings of the Knowledge Management und Kommunikationssysteme, Workflow Management, Multimedia, Knowledge Transfer—Proceedings des 6. Internationalen Symposiums für Informationswissenschaft, ISI 1998, Prague, Czech Republic, 3–7 November 1998; pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Evans, L. The museum of digital things: Extended reality and museum practices. Front. Virtual Real. 2024, 5, 1396280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, K. From Blindness to Blindness: Museums, Heterogeneity and the Subject. Sociol. Rev. 1999, 47, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, K. Museums and the Visually Impaired: The Spatial Politics of Access. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 48, 444–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayne, S.; Ross, J.; Williamson, Z. Objects, subjects, bits and bytes: Learning from the digital collections of the National Museums. Mus. Soc. 2009, 7, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurstad, A. Cod, curtains, planes and experts: Relational materialities in the museum. J. Mater. Cult. 2012, 17, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimov, G.I. The ideal essence of a museum object. Issues Museol. 2021, 12, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. A Bodies-On Museum: The Transformation of Museum Embodiment through Virtual Technology. Curator Mus. J. 2023, 66, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhtamo, E. On the Origins of the Virtual Museum. In Museums in a Digital Age, 1st ed.; Parry, R., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, I.; Stärk, T. On The Terminology of the Virtual Museum. In Virtual Museums—A Plea: Around the Clock, Around the World; Forum, V.M., Ed.; Deutscher Kunstverlag (DKV): Berlin, Germany, 2024; pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, K.F.; Simmons, J.E. Foundations of Museum Studies: Evolving Systems of Knowledge; Libraries Unlimited: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tsichritzis, D.; Gibbs, S.J. Virtual Museums and Virtual Realities. In International Cultural Heritage Informatics Meeting; Sheraton Station Square: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1991; pp. 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pujol, L.; Lorente, A. The Virtual Museum: A Quest for the Standard Definition. In Archaeology in the Digital Era; Philip, V., Graeme, E., Eds.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sebeok, T.A.; Danesi, M. The Forms of Meaning; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, T.W. Negative Dialectics; Seabury Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, A. Adorno, Hegel, and Dialectic. Br. J. Hist. Philos. 2014, 22, 1118–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesi, M. Signs, forms, and models: Thomas, A. Sebeok’s enduring legacy for semiotics. Chin. Semiot. Stud. 2021, 17, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. On Semiotic Modeling; Suzhou University Press: Suzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Horkheimer, M. Critique of Instrumental Reason; Verso: Miamisburg, OH, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Biedermann, B. ‘Virtual museums’ as digital collection complexes. A museological perspective using the example of Hans-Gross-Kriminalmuseum. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2017, 32, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Saussure, F. Writings in General Linguistics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bekele, M.K.; Pierdicca, R.; Frontoni, E.; Malinverni, E.S.; Gain, J. A Survey of Augmented, Virtual, and Mixed Reality for Cultural Heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2018, 11, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, Y.; Tian, F. Contrasting Physical and Virtual Museum Experiences: A Study of Audience Behavior in Replica-Based Environments. Sensors 2025, 25, 4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buragohain, D.; Meng, Y.; Deng, C.; Li, Q.; Chaudhary, S. Digitalizing cultural heritage through metaverse applications: Challenges, opportunities, and strategies. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jung, T.H.; tom Dieck, M.C.; Chung, N. Experiencing immersive virtual reality in museums. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, C.S. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Danesi, M. The concept of model in Thomas, A. Sebeok’s semiotics. In New Semiotics. Between Tradition and Innovation; IASS Publications & NBU Publishing House: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2014; pp. 1495–1506. [Google Scholar]

- Kull, K. Umwelt and modelling. In The Routledge Companion to Semiotics; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. A Theory of Semiotics; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Polidoro, P. Umberto Eco and the problem of iconism. Semiotica 2015, 2015, 129–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibniz, G.W.; Remnant, P.; Bennett, J. Leibniz: New Essays on Human Understanding, 2nd ed.; Remnant, P., Bennett, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Juul, J. Half-Real: Video Games between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds; MIT Press: Cambrigde, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mochocki, M. Heritage Sites and Video Games: Questions of Authenticity and Immersion. Games Cult. 2021, 16, 951–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, C.S. The Semiotic Engineering of Human-Computer Interaction; The MIT Press: Cambrigde, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boboc, R.G.; Băutu, E.; Gîrbacia, F.; Popovici, N.; Popovici, D.-M. Augmented Reality in Cultural Heritage: An Overview of the Last Decade of Applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.M.; Corsi, D.; De Stefani, M.; Giachetti, A. Gestural Interaction and Navigation Techniques for Virtual Museum Experiences. In Proceedings of the AVI*CH 2016 Advanced Visual Interfaces for Cultural Heritage, Bari, Italy, 7–10 June 2016; pp. 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bannon, L. Reimagining HCI. Interactions 2011, 18, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, G. A Short History of Human Computer Interaction. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGUCCS Annual Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 7–10 October 2018; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Pietroni, E.; Pagano, A.; Fanini, B. UX Designer and Software Developer at the Mirror: Assessing Sensory Immersion and Emotional Involvement in Virtual Museums. Stud. Digit. Herit. 2018, 2, 13–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liarokapis, F.; Sylaiou, S.; Basu, A.; Mourkoussis, N.; White, M.; Lister, P.F. An interactive visualisation interface for virtual museums. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Intelligent Cultural Heritage, Oudenaarde, Belgium, 7–10 December 2004; pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Giangreco, I.; Sauter, L.; Parian, M.A.; Gasser, R.; Heller, S.; Rossetto, L.; Schuldt, H. Virtue. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, Marina del Ray, CA, USA, 17–20 March 2019; pp. 119–120. [Google Scholar]

- Zidianakis, E.; Partarakis, N.; Ntoa, S.; Dimopoulos, A.; Kopidaki, S.; Ntagianta, A.; Ntafotis, E.; Xhako, A.; Pervolarakis, Z.; Kontaki, E.; et al. The Invisible Museum: A User-Centric Platform for Creating Virtual 3D Exhibitions with VR Support. Electronics 2021, 10, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, R.; Walczak, K.; White, M.; Cellary, W. Building Virtual and Augmented Reality museum exhibitions. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on 3D Web Technology, Monterey, CA, USA, 5–8 April 2004; pp. 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Nie, J.-W.; Ye, J. Evaluation of virtual tour in an online museum: Exhibition of Architecture of the Forbidden City. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0261607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Zou, N.; Yang, W.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, P. User experience model and design strategies for virtual reality-based cultural heritage exhibition. Virtual Real. 2024, 28, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariya, P.; Wongwan, N.; Worragin, P.; Intawong, K.; Puritat, K. Immersive realities in museums: Evaluating the impact of VR, VR360, and MR on visitor presence, engagement and motivation. Virtual Real. 2025, 29, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, A.; Rodríguez, I.; Arcos, J.L.; Rodríguez-Aguilar, J.A.; Cebrián, S.; Bogdanovych, A.; Morera, N.; Palomo, A.; Piqué, R. Lessons learned from supplementing archaeological museum exhibitions with virtual reality. Virtual Real. 2019, 24, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylaiou, S.; Fidas, C. Virtual Humans in Museums and Cultural Heritage Sites. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Garcia, B.; Guillen-Sanz, H.; Checa, D.; Bustillo, A. A systematic review of virtual 3D reconstructions of Cultural Heritage in immersive Virtual Reality. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 89743–89793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, C.K.; Richards, I.A. The Meaning of Meaning: A Study of the Influence of Language Upon Thought and of the Science of Symbolism; Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H. Meaning Generation. Chin. Semiot. Stud. 2019, 15, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. Modeling in semiotics: An integrative update. Chin. Semiot. Stud. 2021, 17, 639–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fligstein, N.; McAdam, D. A Theory of Fields; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.; Nam, Y. Do Presence and Authenticity in VR Experience Enhance Visitor Satisfaction and Museum Re-Visitation Intentions? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Suh, J. The Impact of VR Exhibition Experiences on Presence, Interaction, Immersion, and Satisfaction: Focusing on the Experience Economy Theory (4Es). Systems 2025, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelhalter, D. Why probability probably doesn’t exist (but it is useful to act like it does). Nature 2024, 636, 560–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, R.S. An Examination of Objective and Subjective Measures of Experience Associated to Odors, Music, and Paintings. Empir. Stud. Arts 1998, 16, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munar, E.; Nadal, M.; Castellanos, N.P.; Flexas, A.; Maestu, F.; Mirasso, C.; Cela-Conde, C.J. Aesthetic appreciation: Event-related field and time-frequency analyses. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2011, 5, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maquet, J.J.P. The aesthetic experience: An anthropologist looks at the visual arts; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lankford, E.L. Aesthetic Experience in Constructivist Museums. J. Aesthetic Educ. 2002, 36, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gernsbacher, M.A.; Derry, S.J. Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 208–213. [Google Scholar]

- Yezhova, O.; Zhao, J.; Pashkevych, K. Exploring Design Aspects of Online Museums: From Cultural Heritage to Art, Science and Fashion. Preserv. Digit. Technol. Cult. 2025, 54, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahrn-Andersen, R.; Festila, M.S.; Secchi, D. Systemic Cognition: Sketching a Functional Nexus of Intersecting Ontologies. In Multiple Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, L.F. How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, T.W. Subject and Object. In The Essential Frankfurt School Reader; Andrew, A., Eike, G., Eds.; Urizen Books: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Theodor Adorno: The Primal History of Subjectivity—Self-Affirmation Gone Wild. In Philosophical-Political Profiles; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill, P. The curatorial turn: From practice to discourse. Issues Curating Contemp. Art Perform. 2007, 25, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wray, L. Taking a position: Challenging the anti-authorial turn in art curating. In Museum Activism; Janes, R.R., Sandell, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 315–325. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, K. From Caring to Creating: Curators Change Their Spots. In The International Handbooks of Museum Studies; McCarthy, C., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 317–339. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. The Theory of Communicative Action: Volume 1: Reason and the Rationalization of Society; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Sparacino, F.; Davenport, G.; Pentland, A. Media in performance: Interactive spaces for dance, theater, circus, and museum exhibits. IBM Syst. J. 2000, 39, 479–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahrn-Andersen, R. Nexuses of performativity: Systemic generalities, infrastructures and practical ontologies. Thesis Elev. 2025, 187, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S.-B.; Kwon, C. Preference Factors of the Korean MZ Generation vis-à-vis the Online Programs of Museums Abroad. J. Digit. Converg. 2022, 20, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, K.A. The Content Analysis Guidebook; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lombard, M.; Snyder-Duch, J.; Bracken, C.C. Content Analysis in Mass Communication: Assessment and Reporting of Intercoder Reliability. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horkheimer, M.; Adorno, T.W.; Noeri, G.S. Dialectic of Enlightenment; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Adorno, T.W.; Simpson, G. On Popular Music. Z. Für Sozialforschung 1941, 9, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Chen, P. Meaning in the Algorithmic Museum: Towards a Dialectical Modelling Nexus of Virtual Curation. Heritage 2025, 8, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, G.E. Learning in the Museum; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, R.; D’souza, W.; Rivière, G.H. The museum as a Communicator: A semiotic analysis of the Western Australian Museum Aboriginal Gallery, Perth. Mus. Int. 1979, 31, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, J. Museums as Contact Zones. In Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997; pp. 188–219. [Google Scholar]

- DaCosta, B. Historical Depictions, Archaeological Practices, and the Construct of Cultural Heritage in Commercial Video Games: The Role of These Games in Raising Awareness. Preserv. Digit. Technol. Cult. 2024, 53, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan, S. The Virtual Aura—Is There Space for Enchantment in a Technological World? In Proceedings of the Museum and the Web 2001, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–17 March 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B.; Lowe, A. The Migration of the Aura Exploring the Original Through Its Fac similes. In Switching Codes Thinking Through Digital Technology in the Humanities and the Arts; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011; pp. 275–297. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, R.; Dziekan, V. Critical digital: Museums and their postdigital circumstance. In Art, Museums & Digital Cultures: Rethinking Change; Barranha, H., Simoes Henriques, J., Eds.; Universidade NOVA de Lisboa: Lisbon, Portugal, 2021; pp. 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Creed, C.; Al-Kalbani, M.; Theil, A.; Sarcar, S.; Williams, I. Inclusive Augmented and Virtual Reality: A Research Agenda. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 6200–6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepe, F.; Luongo, S.; Di Gioia, L.; Della Corte, V. Cultural heritage experiences in the metaverse: Analyzing perceived value and behavioral intentions. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 28, 2054–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | Intro |

|---|---|

| Case A: British Museum Bronze Age VR Experience (UK, VR). | The British Museum’s first virtual reality weekend exhibit (2015) which allowed visitors to virtually enter a Bronze Age roundhouse and examine 3D-scanned artifacts in situ. This case represents a Western national museum using VR to enhance storytelling around real objects. |

| Case B: The Museum of the World—British Museum/Google (UK, Web Interactive). | An interactive timeline and world map of objects curated by the British Museum in partnership with Google Arts & Culture. This browser-based experience links thousands of objects across time, geography, and themes in a highly networked interface. |

| Case C: Digital Beijing Central Axis (China, 3D/VR). | A digital heritage project presenting Beijing’s Central Axis, a newly UNESCO-inscribed World Heritage site through immersive media. It integrates 3D models of architecture and AR/VR elements to convey the “ideal order” of the historic capital. This East Asian case highlights a concept-driven virtual reconstruction of urban heritage. |

| Case D: Virtual Angkor (Cambodia, 3D Simulation). | An educational 3D simulation of the city of Angkor around 1300 CE, created by a collaboration of historians and technologists. It recreates the sprawling metropolis at the height of the Khmer Empire’s power, allowing exploration of environments and scenarios (e.g., a stone workshop, temple rituals) in a game-like interface. |

| Case E: National Museum of the D.R. Congo Virtual Tour (DRC, 360° Web Tour/VR). | A virtual tour of the National Museum in Kinshasa, developed in partnership with tech firms to enable remote 3D exploration of galleries and artifacts. Viewers can navigate the museum’s interior with high-resolution 360° imagery or VR headsets. This Global South case exemplifies an object-preserving approach, virtually replicating a physical museum for broader access. |

| Case | Region/Tech | Abstraction Ratio (AR) | Connectivity Ratio (CR) | Object Primacy (OPS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. British Museum VR (UK, VR) | Western, VR experience | 0.30 (moderate) | 0.40 (moderate) | 0.20 (low-moderate) |

| B. Museum of the World (UK, Web) | Western, web interactive | 0.50 (high) | 0.60 (high) | 0.30 (moderate) |

| C. Digital Central Axis (China, 3D) | East Asian, 3D/VR heritage | 0.70 (very high) | 0.40 (moderate) | 0.10 (very low) |

| D. Virtual Angkor (Cambodia, 3D) | Global South (Asia), 3D sim | 0.55 (high) | 0.60 (high) | 0.10 (very low) |

| E. DRC Museum Tour (DRC, Web/VR) | Global South (Africa), 360° | 0.05 (negligible) | 0.20 (low) | 0.60 (high) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guan, H.; Chen, P.; Kwon, C.L. Virtual Museums as Meaning-Modeling Systems in Digital Heritage. Heritage 2025, 8, 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110484

Guan H, Chen P, Kwon CL. Virtual Museums as Meaning-Modeling Systems in Digital Heritage. Heritage. 2025; 8(11):484. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110484

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuan, Huining, Pengbo Chen, and Cheeyun Lilian Kwon. 2025. "Virtual Museums as Meaning-Modeling Systems in Digital Heritage" Heritage 8, no. 11: 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110484

APA StyleGuan, H., Chen, P., & Kwon, C. L. (2025). Virtual Museums as Meaning-Modeling Systems in Digital Heritage. Heritage, 8(11), 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110484