Abstract

The protection of historic buildings in seismic-prone regions is a critical challenge requiring strategies that balance structural safety with cultural preservation. This study proposes an integrated methodological framework for assessing seismic risk in heritage contexts by combining Geographic Information System (GIS)-based large-scale analyses with detailed Finite Element Method (FEM) simulations. At the urban scale, the framework is applied to more than 70 buildings in the historic center of Bronte (Eastern Sicily, Italy) to evaluate Soil–Structure Interaction (SSI) effects and identify priority areas for mitigation. At a detailed scale, the approach is validated through an in-depth investigation of the San Giovanni Evangelista bell-tower, a representative historic structure within the study area. For this case, sustainable Geotechnical Seismic Isolation (GSI) systems using well-graded Gravel–Rubber Mixtures (wgGRMs) are numerically tested as a low-impact retrofitting strategy. The results demonstrate that combining large-scale mapping with detailed structural modeling provides both broad urban insight and accurate site-specific evaluations, offering a replicable decision-support tool for seismic risk reduction in heritage environments. Additionally, wgGRMs-based GSI system significantly reduces seismic accelerations and drifts, offering a low-impact, sustainable retrofitting solution that reuses waste materials and fully preserves architectural integrity.

1. Introduction

The conservation of building heritage in seismic-prone regions represents a pressing scientific and societal challenge. Historic structures, which often embody unique architectural styles and construction techniques, are particularly vulnerable to seismic events due to age-related degradation, inadequate structural systems, and a lack of compliance with modern seismic codes [1,2]. Their protection requires not only preservation of cultural value but also the integration of advanced engineering solutions capable of mitigating seismic risk. Within this dual context, the development of methodological frameworks that reconcile heritage conservation with innovative seismic safety strategies has emerged as a central research priority. Italy is among the Mediterranean countries most exposed to seismic hazards, as it experiences both frequent and intense earthquake events [1,3,4]. Furthermore, Eastern Sicily (Italy) stands out as one of the areas with the most significant seismic risk. This is primarily attributed to the fragility of its historic masonry buildings, combined with the occurrence of significant earthquakes that have repeatedly affected the area [5,6].

A key factor influencing the seismic performance of the structures is Soil–Structure Interaction (SSI) and the local soil conditions. SSI can either amplify or reduce structural demands depending on the soil type, building characteristics, and seismic hazard scenarios [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Neglecting these effects can lead to inaccurate predictions of seismic risk and misguided retrofitting interventions. While it is widely recognized that SSI alters a structure’s dynamic response and the foundation input motion [13,14,15,16,17,18], conventional structural design and urban risk assessments often neglect this complexity, relying on fixed-base models. This simplification can lead to inaccurate risk predictions, as local soil conditions are known to significantly modify seismic motion characteristics [19,20,21,22]. Consequently, studies on Local Seismic Response (LSR) have been central to Seismic Microzonation (SM), typically conducted under free-field conditions to map surface-level hazard [23,24,25,26].

In this framework, several studies have developed methodologies to explicitly incorporate SSI into large-scale assessments. For example, research studies [12,27] studies by leveraged LiDAR and design accelerations to quantify SSI effects at an urban scale in Thessaloniki and Catania, respectively. Parallel, more comprehensive frameworks have been proposed [28,29,30], which integrate physics-based simulations and data-driven techniques to evaluate fragility, loss, and resilience while explicitly accounting for SSI.

However, rather than being a complicating factor, SSI effects can be strategically exploited to improve the overall structural response through controlled geotechnical interventions. This principle is the basis for Geotechnical Seismic Isolation (GSI), an emerging line of research that mitigates seismic demand at the soil-foundation interface rather than through structural interventions [31,32]. GSI solutions are inherently compatible with heritage conservation principles, as they operate beneath the structure without altering its architectural integrity. GSI systems capitalize on the SSI effects by replacing or modifying the foundation’s natural soil with well-controlled, low-modulus materials, thereby enhancing the overall structural performance [32,33]. In this context, soil-rubber mixtures have been proposed as low-modulus GSI materials [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] utilizing the well-known foundation rocking isolation mechanism [32]—a topic that has received considerable attention in recent years [42,43,44]. Additionally, they can lengthen the structure’s fundamental natural period and increase the system’s damping, thereby limiting the structure’s potential for damage [45,46]. Soil-rubber mixtures are made by mixing cohesionless soil with rubber grains from End-of-Life tires (ELT). The recycling of waste, such as ELT or part of ELT, to transform it into products, represents a significant challenge that supports the global Sustainable Development Goals [47]. Recent experimental and numerical studies on well-graded Gravel-Rubber Mixtures (wgGRMs) have demonstrated their effectiveness as a GSI system in attenuating ground accelerations, enhancing energy dissipation, and offering sustainable retrofitting alternatives through the reuse of recycled materials [48,49]. This makes GSI particularly attractive in seismically active regions such as Eastern Sicily (Italy), where vulnerable historic masonry assets are widespread and conventional retrofitting strategies often face social, cultural, and economic barriers.

This study addresses a critical disconnect in seismic risk assessment: while urban-scale frameworks often overlook detailed soil-structure coupling, and GSI studies rarely transition to real-world applications, a unified approach is lacking. To bridge this gap, the study presents an integrated methodological framework that combines Geographic Information System (GIS)-based large-scale SSI evaluation, detailed FEM modeling of a representative heritage structure, and the practical implementation of a sustainable GSI strategy using wgGRMs. The methodology is demonstrated through a case study of the historic center of Bronte, Eastern Sicily—an area of particular interest due to its volcanic lithology and its impact on the urban fabric. First, a GIS-based analysis of over 70 buildings provides a large-scale screening of SSI effects, identifying priority zones for intervention. This large-scale prioritization then directly informs a second, detailed-scale investigation of the San Giovanni Evangelista bell tower, within the large-scale study area, where FEM analysis validates the large-scale procedure and quantitatively assesses the effectiveness of an innovative GSI system using wgGRMs. This approach, from urban screening to a validated retrofitting solution for a specific heritage asset, provides a replicable model for seismic risk reduction that connects strategic planning with practical, conservation-compatible implementation.

2. The Investigated Site and Structure

2.1. The Historic Center of Bronte

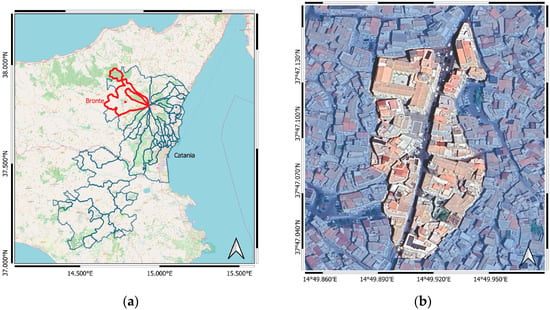

The Municipality of Bronte (Catania, Eastern Sicily, Italy) covers an area of 250.86 km2 and is one of the largest in the Catania area (Figure 1a). The territory extends mainly along a north–south direction, with a maximum length (including the Mt. Etna area) of approximately 33 km and an elevation difference from the lowest point (380 m) to the highest point (3350 m, Mt. Etna) of 2970 m.

Figure 1.

The municipality of Bronte: (a) territorial framework with respect to the Catania area; (b) the investigated Bronte area for Soil–Structure Interaction (SSI) effects using a large-scale assessment procedure.

The historic center of Bronte preserves a medieval urban form, characterized by a tight network of narrow, winding alleys, small courtyards, and under-arch passages—features that are often attributed to Arab-influenced urban typologies on the western slopes of Mt. Etna [50]. The study area in the historic center of Bronte, chosen for a large-scale study of SSI effects, is depicted in Figure 1b.

The area includes buildings that are mainly load-bearing masonry buildings, with 2–3 above-ground floors, originally constructed between the 18th and 19th centuries and subsequently modified or extended during the 20th century. The structures are made of mixed masonry with lava stone and solid bricks, often featuring wooden or vaulted brick floors, and shallow foundations resting on volcanic and pyroclastic soils typical of the western slope of Mount Etna. Some more recent buildings, dating from the 1960s to 1980s, are made of ordinary reinforced concrete with beam-and-column frames, characterized by higher structural stiffness compared to the surrounding historical fabric.

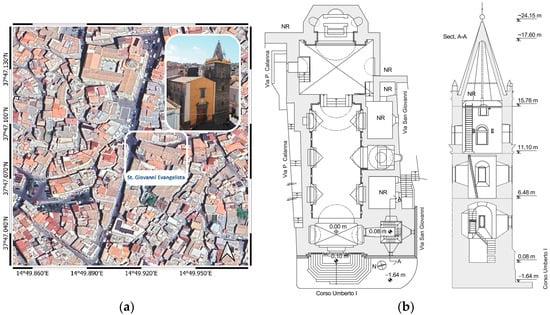

2.2. The Specific Case of the San Giovanni Evangelista Bell-Tower

Within the historic center of Bronte, 16th-century bell towers, slender masonry structures, emerge as significant architectural and social landmarks [51]. Among them, particularly notable in the area under study, is the bell-tower of St. Giovanni Evangelista, leaning against the church of the same name (Figure 2a). The St. Giovanni Evangelista bell-tower will be the focus of a detailed study of SSI effects using FEM modeling (Section 4.1). In addition, its seismic performance will be assessed using wgGRMs as a sustainable GSI system (Section 4.2). Constructed in 1614, the bell-tower features a quadrangular layout with external sides measuring roughly 6.00 m and rises to an overall height of 25.80 m [51] (Figure 2b). Although no instrumental measurements or direct survey data are available, traditional building methods typical of the Mt. Etna area [52,53] suggest that its foundations likely consist of continuous masonry footings, extending approximately 1.50 m below grade and exceeding the thickness of the above-ground walls by 30–50 cm. The tower stands on a pedestal 3.30 m high and is topped by a pyramidal cusp resting on an octagonal base, which has a diameter of 3.98 m and reaches 6.55 m in height at the intrados. The exterior is clad with lava stone blocks (Figure 2a), and the wall thickness tapers progressively with height: from 2.00 to 1.70 m at the ground level, to 1.70–1.63 m at the first floor, and from 1.63 m down to 1.03 m up to the cusp [51]. For the present work, section A–A (Figure 2b) is analyzed numerically through the development of 2D FEM models, as detailed in Section 4.1.

Figure 2.

The bell-tower of St. Giovanni Evangelista in Bronte: (a) picture of the St. Giovanni Evangelista church and its bell-tower; (b) plan view and cross-section [45,51].

Based on this framework, the Municipality of Bronte was selected as the case-study area based on three main criteria.

- Urban representativeness: The historic center of Bronte preserves a dense medieval layout with numerous unreinforced-masonry buildings and narrow streets, typifying many small and medium-sized Sicilian towns. Therefore, results obtained here can be readily transferred to similar heritage contexts across the region.

- Data availability: Comprehensive geological, geotechnical, and seismic microzonation data are publicly available for Bronte through national and regional databases, enabling reliable GIS-based and FEM analyses.

- Seismic relevance: as will be discussed in Section 2.2, Bronte lies on the western flank of Mt. Etna within one of the most seismically active sectors of Eastern Sicily, repeatedly affected by both regional and volcano-tectonic earthquakes. This makes it a critical site for testing heritage-related seismic mitigation frameworks.

Within this urban fabric, the San Giovanni Evangelista bell-tower was chosen as the representative structure for the detailed-scale analysis. The tower is emblematic of the area’s 16th-century masonry typologies—slender, vertically extended, and composed of lava-stone blocks typical of Mt. Etna construction practices. Its geometric regularity, well-documented historical background, and location within one of the zones identified as seismically sensitive by the large-scale GIS assessment make it an ideal benchmark for detailed SSI and GSI investigation.

2.3. Geotechnical Context and Seismic Input Motions

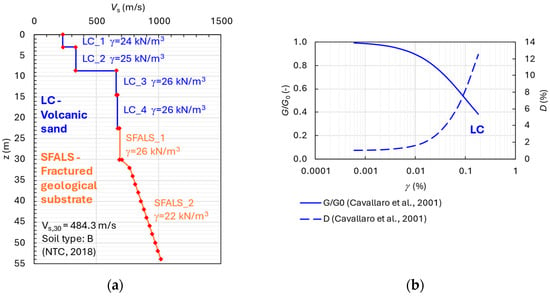

Within the portion of the municipality of Bronte considered in this study, volcanic soils are widespread [54,55]. In the site investigated, Multichannel Analysis of Surface Waves (MASW) surveys and borehole investigations were conducted. The MASW surveys provided the shear-wave velocity (Vs) profile shown in Figure 3a. A linear interpolation of these profiles was used to estimate the depth of the seismic bedrock—defined as the depth at which vs. reaches or exceeds 800 m/s stably [56]—which was determined to be 54 m below the surface. Since this depth exceeds 30 m, the weighted average shear-wave velocity in the upper 30 m (Vs,30) was calculated in accordance with the current Italian building code, NTC 2018 [57], resulting in a value of 484.30 m/s, corresponding to soil type B.

Interpretation of the MASW data, combined with borehole investigations, identified a surface geological unit of volcanic sand, referred to as “LC”, extending from ground level to approximately 22.50 m depth. Below this, a fractured substrate designated “SFALS” was encountered. Laboratory test [58,59] provided the unit weight values for these layers, as illustrated in Figure 3a.

In the absence of site-specific dynamic testing, the dynamic behavior of the LC layers was characterized using experimental relationships proposed in the literature between normalized shear modulus (G/G0) and shear strain (γ), and between damping ratio (D) and γ, for volcanic soils of similar composition [60,61], as shown in Figure 3b.

The LC material is a characteristic volcanic deposit composed of alternating lava and tuff layers interbedded with sandy and gravelly lenses. The deeper SFALS formation has been classified as basaltic lava [56], and its mechanical behavior was inferred from existing studies on volcanic rock formations from the Mt. Etna area.

Bronte lies on the western flank of Mt. Etna, so its seismicity is dominated by frequent, mostly shallow volcano-tectonic earthquakes tied to Etna’s active fault network [62,63,64,65,66], with additional hazard from larger faults (e.g., the Ibleo-Maltese fault system) that have produced damaging events historically in eastern Sicily [67].

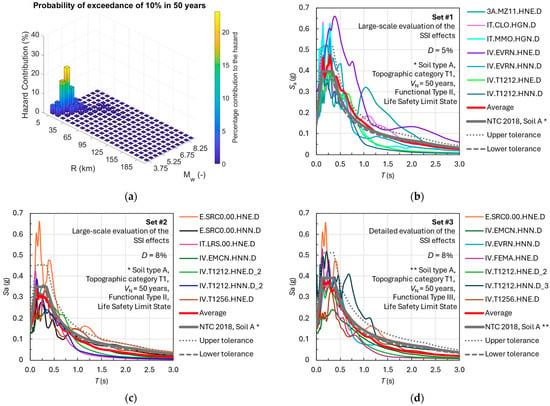

Regarding the seismic motions used in the analyses, three sets of seven spectrum-compatible accelerograms were selected, according to NTC 2018 [57]. Two sets were adopted for the large-scale evaluation of the SSI effects: the first for reinforced concrete buildings and the second for masonry buildings, characterized by damping ratios of 5% and 8%, respectively. A third set was used for the detailed evaluation of the SSI effects on the bell-tower located within the study area.

Figure 3.

The soil properties of the investigated area: (a) Shear wave velocity profile (Vs vs. z) obtained from the MASW test; (b) shear modulus (G/G0 vs. γ) and damping ratio (D vs. γ) curves for the investigated soil layers LC [60].

All the selected seismic motions are compatible with the disaggregation of the seismic hazard [68] in terms of the moment magnitude (Mw) and epicentral distance (R), within the range Mw = 4.0–7.0 and R = 0–30 km (Figure 4a), as well as the target response spectrum specified by NTC 2018 [57]. The seismic motions were selected using the Rexel WEB code [69], in compliance with the average spectral compatibility criteria prescribed by NTC 2018 [57].

Figure 4.

Selection of the seismic motions: (a) range values for the disaggregation of the seismic hazard considering a probability of exceedance of 10% in 50 years; (b) elastic response spectra for the set #1, large-scale evaluation of SSI effects for the reinforced concrete structures with D = 5%; (c) elastic response spectra for the set #2, large-scale evaluation of SSI effects for the masonry structures with D = 8%; (d) elastic response spectra for the set #3, detailed evaluation of SSI effects for the bell-tower with D = 8%. Data compared with the elastic response spectra proposed by NTC 2018 [57].

As for the large-scale evaluation of the SSI effects, the spectra were defined for the following site and design conditions: Soil type A, Topographic category T1, Nominal Life (VN) of 50 years, Functional Type II, and Life Safety Limit State. The final average spectra fall within a tolerance band of −10% to +30% of the reference response spectrum over the period range 0.15–2.0 s. The elastic response spectra were obtained considering a damping of 5% and 8%, which were adopted for reinforced concrete and masonry buildings, respectively, according to NTC 2018 [57].

Regarding the detailed evaluation of the SSI effects, the spectrum was defined based on the previous site and design conditions, except for the Function Type. For the bell-tower, Functional Type III was selected based on the detailed scale analysis carried out and according to guidelines for “The assessment and reduction of seismic risk of cultural heritage aligned with the new NTC 2008” [70]. Additionally, a damping of 8% was considered for a masonry structure, according to NTC 2018 [57]. Figure 4b,c show the elastic response spectra used for the large-scale evaluation of SSI effects. Figure 4d presents the elastic response spectra, which are used for a detailed evaluation of the SSI effects. Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of the seismic motions, including Mw, ag (peak ground acceleration), and R.

Table 1.

Main properties of the earthquake data for the analyses. Sets #1 and #2 are the groups of seismic motions adopted for the large-scale evaluation of the SSI effects, considering reinforced concrete and masonry structures, respectively. Set #3 is the group of seismic motions adopted for the detailed evaluation of the SSI effects on the bell-tower investigated.

3. Methodology for Large-Scale Soil-Structure (SSI) Assessment for the Historic Center of Bronte

3.1. GIS-Integrated Framework and Data Processing

The large-scale GIS-integrated assessment represents the first level of the framework, designed for urban-scale screening. It quantifies potential SSI effects across multiple buildings using simplified, yet spatially exhaustive, models that guide the selection of case-specific detailed studies. The method systematically combines geographical, seismological, geological, geotechnical, and structural data to provide a comprehensive understanding of the site. Developed with the open-source QGIS software (version 3.34 Prizren) [71] and based on open data, the approach is designed to be replicable in other urban contexts within the Italian territory, in accordance with the national regulatory framework (NTC 2018 and ICMS 2008 guidelines [57,72]) and depending on the regional availability of territorial data. Its primary output is a set of thematic maps that analyze potential SSI effects, supporting engineers and planners in monitoring individual buildings as well as sites of historical and architectural value.

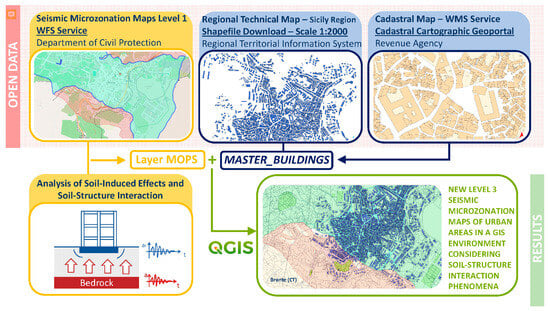

As introduced in Section 2.1, the study area encompasses the urban fabric in the historic center of Bronte, including the San Giovanni Evangelista bell tower. The historical buildings are predominantly composed of bearing-wall masonry structures from the 18th and 19th centuries, constructed with volcanic stone and brick, and later modified in the 20th century. The framework advances traditional cartographic representations of SM maps derived from LSR analyses. It does so by optimizing the structure of vector-based thematic layers for homogeneous zones and incorporating additional layers describing the built environment. More specifically, the system is supported by a geodatabase of vector-based thematic layers, developed in accordance with ICMS 2008 guidelines and Italian SM Standards [72], which stores data and generates thematic maps. The data layers can be obtained from the Information and Cartographic Portal of Seismic Microzonation Studies and Limit Condition for Emergency Analysis [73]. The portal also makes its contents accessible via WMS (Web Map Service) and WFS (Web Feature Service), both OGC (Open Geospatial Consortium) standards, enabling the sharing of geospatial data and ensuring compatibility with GIS (Geographic Information Systems) environments. Additional information on the built environment has been integrated into the framework, including data from the Sicilian Region’s Cartographic Portal and the Italian Revenue Agency [74]. Figure 5 presents a flowchart that illustrates the structure and organization of the geodatabase developed for the large-scale assessment of SSI effects. The diagram shows the process of integrating open data from various institutional sources—Level 1 Seismic Microzonation Maps (Department of Civil Protection), the Regional Technical Map (Sicilian Region), and the Cadastral Map (Italian Revenue Agency)—within the QGIS environment. These datasets are combined to generate the Master buildings layer, to which the data from the Microzones Homogeneous in Seismic Perspective (MOPS) and the results of Local Seismic Response analyses are associated. This process enables the production of advanced SM maps that incorporate SSI effects.

Figure 5.

Integration of open data for the generation of SM maps, including the effects of SSI, using QGIS software [71].

3.2. Modeling Approach for Soil-Structure Interaction

The creation of the geodatabase for the large-scale evaluation of the SSI effects involved the following steps:

- Data Integration: merging fragmented regional building maps with cadastral data to create accurate, whole-building polygons;

- Spatial Linking of Microzonation Data to Building Assets: assigning detailed seismic and geotechnical properties from “Microzones Homogeneous in Seismic Perspective” (MOPS) to each building based on its location;

- Structuring the Model: organizing all this information into a single “Master Buildings” layer with logical modules (Input, Output, etc.), which serves as the foundation for all calculations and map generation.

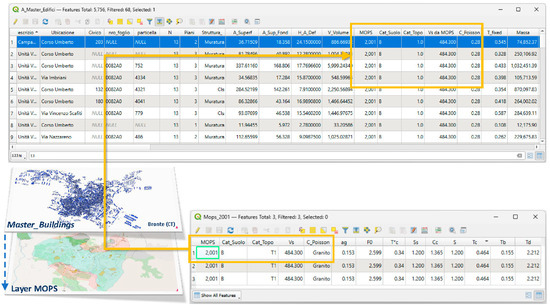

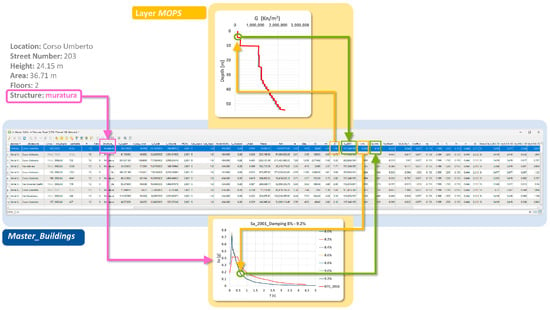

After data acquisition and reprojection, it was necessary to define all the information required for SSI evaluation into a single layer. This layer needed to include not only the physical attributes of each building but also the geotechnical parameters of the site, while allowing classification based on the building’s location and typology. For this purpose, two core components were defined: the MOPS layer, which contained the geotechnical and seismic characteristics of the study area, and the Master Buildings layer, a polygon-based layer that encompassed all buildings within the study area, including their physical attributes. To enable the evaluation of SSI effects, a spatial association was established between the two layers, specifically between microzones and buildings (Figure 6). In this way, each building was assigned to the geotechnical properties of the MOPS on which it is located. The integration of these datasets into a single layer, combining both building-related attributes and geotechnical parameters, formed the integrated framework for all subsequent analyses.

Figure 6.

Functions for related spatial databases: the MOPS layer and the Master Buildings layer for the SSI evaluation.

The MOPS layer was subdivided into as many layers as the number of microzones identified within the investigated area. Each MOPS layer was then enriched with specific attributes (Figure 7). The first set of attributes includes equivalent shear-wave velocity (Vs,eq), Stratigraphic and Topographic Category, and Poisson’s ratio (ν). The Vs,eq was defined according to NTC 2018 [57], based on the shear-wave velocity profile from MASW and Down-Hole geophysical surveys. The Stratigraphic Category was defined based on Vs,eq, according to NTC 2018 [57]. A Topographic Category, designated as “T1” according to NTC 2018 [57], which refers to a flat topographic soil surface leading to a topographic amplification factor (ST) of 1, was defined for the entire investigated area. The values of ν were defined according to the different soil types, based on literature data [75], considering a value for each soil type between the minimum and maximum limits reported. A second set of data includes the seismic base hazard data for the Municipality of Bronte, such as ag, the acceleration response spectrum amplification factor (F0), and the period marking the beginning of the constant-velocity segment of the spectrum (T*c). The third attribute set also comprises the stratigraphic amplification factor (Ss), the dynamic amplification factor (Cc), the amplification factor (S, being equal to Ss × ST), and the characteristic periods of the elastic response spectrum (Tc, Tb, and Td). All these parameters were determined in accordance with NTC 2018 [57] and based on the guidelines provided by the national seismic hazard map developed by INGV [76].

Figure 7.

Specific attributes associated with each MOPS layer: results of LSR analyses; municipal seismic hazard parameters (ag, F0, T*c); parameters determined according to NTC 2018 [57] (Ss, Cc, S, Tc, Tb, Td).

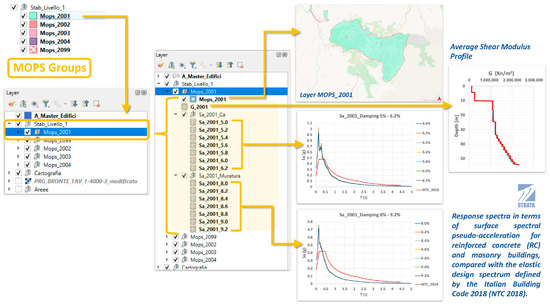

Additionally, the MOPS layers were organized into groups to include the results of LSR analyses performed using STRATA software (version 0.2.0) [77] and utilizing the seismic motion sets #1 and #2, as described in Section 2.2. The output data includes the variation in the shear modulus (G) and the mean response spectra for each set evaluated at the soil surface. Response spectra were computed by differentiating the results according to the structural typology, considering reinforced concrete buildings (D = 5%) and masonry buildings (D = 8%), and by using constant intervals of damping to account for its variability due to SSI effects, denoted as DSSI (Figure 8). During data querying, the software utilizes the selected structural typology, along with the corresponding period and damping ratio values, to determine the appropriate spectral ordinates. The results processed with STRATA software were imported into the software as tabular layers. STRATA software enables the management, processing, and visualization of stratigraphic data derived from geotechnical investigations and borehole surveys; however, its direct integration within GIS software environments is not natively supported.

Figure 8.

Tables processed with STRATA loaded in each group, containing the LSR results analyses on the variation in the shear modulus (G) and the mean response spectra, with D ranges starting from 5% for reinforced concrete structures and from 8% for masonry structures.

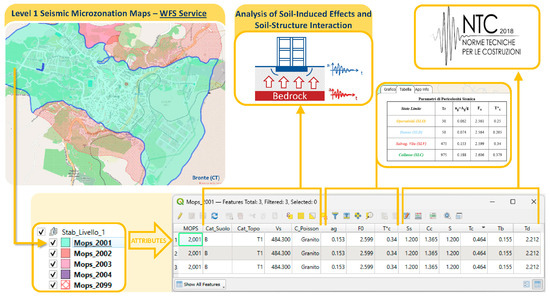

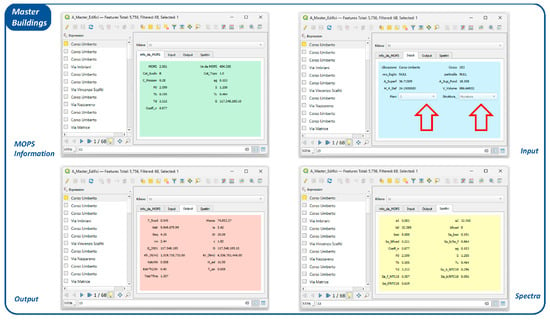

The central and unifying informational layer of the project is the Master Buildings layer (Figure 9). Through spatial overlay functions, the attributes associated with each graphical element on the map are enriched with information from the various underlying MOPS layers, which are preloaded and essential for SSI analyses. The Master Buildings layer (Figure 10) is organized into four logical modules designed to ensure a clear and integrated accessibility of information for each building:

Figure 9.

The Master Buildings layer retrieves data related to the shear modulus and response spectra for each building, based on its structural typology and the flexible-base period value.

Figure 10.

Informative modules of the Master Buildings layer: MOPS Information, Input, Output, Spectra. In the Input module: only editable information → number of building floors and structural typology.

- MOPS Information: The seismic/geotechnical properties assigned from the microzone;

- Input Module: Contains the only user-editable data—the building’s number of floors and structural typology (e.g., masonry, reinforced concrete)—which were collected via field surveys;

- Output Module: Presents the key results, including the building’s fixed-base fundamental period (Tfixed) and the modified period considering SSI effects (TSSI);

- Spectra Module: Provides the corresponding spectral acceleration Sa(Tfixed) and Sa(TSSI), evaluated from the mean response spectra obtained from STRARA software.

Each module aggregates coherent sets of attributes, organized according to the logical sequence of computational procedures and following methodologies described in various studies available in the literature [12].

In particular, the soil–structure system was modeled as an equivalent oscillator capable of translational and rocking motion at its base [13,78]. In this framework, TSSI is a function of a set of parameters, including Tfixed, the stiffness of the structure and foundation, and the effective height of the building [27]. Tfixed was estimated using the simplified relation provided by NTC 2008 [79], as a function of building height and construction type (masonry or concrete). The translational and rocking stiffnesses of the foundation were evaluated by adopting equivalent models based on the footprint area and the moment of inertia of the foundation [27,80,81]. G was introduced by considering an effective influence depth and its degradation with the strain level, as recommended by Eurocode 8 [82]. For the bell-tower subjected to a detailed evaluation of SSI effects, Tfixed is 0.61 s, while TSSI is 0.66 s.

DSSI was defined as the combination of the structural contribution and the contribution related to the foundation [78]. In general, it is higher than the values assumed for fixed-base structures (greater than 5% for concrete and 8% for masonry) [83,84]. As previously introduced, the values thus determined were subsequently used to construct response spectra through the STRATA software. They were then integrated into the MOPS layer in the form of tables. The only editable information is contained in the Input module. It refers to the number of stories and the structural typology of each building, which are not available in the consulted databases and must therefore be acquired through direct survey.

4. Methodology for Detailed (SSI) Effects and Strategies for the Seismic Mitigation Risk for the San Giovanni Evangelista Bell-Tower

4.1. Finite Element Model of the Bell-Tower-Soil System

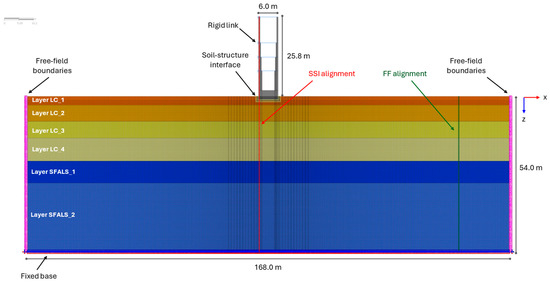

The GIS-based analysis provided a prioritization map for the urban area, identifying zones where SSI effects warranted deeper investigation. Based on these results, the San Giovanni Evangelista bell-tower was selected for a detailed-scale analysis. This second part of the methodology aims to: (i) validate large-scale SSI predictions and capture local nonlinearities for a representative heritage structure, and (ii) evaluate the efficiency of wgGRMs as a sustainable GSI system, as discussed in Section 4.2. FEM analyses provide a robust framework for capturing SSI effects, allowing for a detailed representation of soil stratigraphy, structural properties, and boundary conditions. A rigorous FEM-based approach is therefore fundamental to investigate uplift, sliding, and nonlinear effects at the soil–foundation interface, ensuring reliable predictions of seismic performance. The detailed evaluation of SSI effects for the St. Giovanni Evangelista bell-tower was carried out using 2D FEM modeling with MIDAS FEA NX software (version 1.1) [85]. This modeling approach, while a simplification of the full 3D reality, was chosen for its computational efficiency and its ability to capture the fundamental SSI mechanisms that may be critical for this symmetric, load-bearing wall structure. Two-dimensional models provide reliable first-order insights into SSI effects before moving to complex 3D models, although they assume infinite extent in the out-of-plane direction and cannot reproduce out-of-plane rocking, torsion, and combined vibration modes.

The bell-tower was modeled as a stand-alone structure; both historical and dynamic considerations support this simplification. Historical data indicate the tower was erected in 1614, preceding subsequent structural interventions that formed the main body of the church [51]. This construction sequence suggests that the two structures are likely not monolithically connected, a common feature of historical complexes, where separation joints often allow for independent movement. Dynamically, the slender bell-tower has a higher fundamental frequency than the typically stiffer, more massive church. This significant frequency separation implies that dynamic coupling, while present, is not the dominant factor governing the tower’s primary rocking and translational modes, which are the central focus of this SSI and GSI investigation.

The FEM model (Figure 11) was developed with a soil domain 54.0 m deep and 168.0 m wide to reduce boundary effects and accurately simulate wave propagation. Stratigraphy was assigned according to the geotechnical profile (Figure 3a), while the structure—25.8 m in height and 6.0 m in width (Section 2.1)—was centrally placed. Geometry was derived from Section A–A (Figure 2b); the geometry of the pyramidal cusp was linearized, a common simplification in such analyses that preserves the overall mass and the stiffness of the main masonry walls. Soil layers were discretized using plane-strain four-node solid elements, whereas the structure was modeled with plane stress four-node solid elements. The contribution of the internal floors to the in-plane stiffness was simulated using rigid links at each level (Figure 11), ensuring a realistic coupling between the opposing walls. Mesh sizes satisfied the criterion of being smaller than one-eighth of the shortest wavelength of the input signal [86].

Figure 11.

Two-dimensional FEM model of the fully coupled bell-tower-soil system.

Free-field boundary conditions and Lysmer–Kuhlemeyer viscous dampers [87] were imposed at the model edges, while the base was fixed. At the model base, the seismic motions described in Section 2.2 were applied. The contribution of the internal floors to the in-plane stiffness was simulated using rigid links at each level (Figure 11)

The soil–foundation interaction was represented by contact surfaces that allowed for sliding and uplift, governed by a Coulomb-based formulation [85]. For more details, see Fiamingo et al. [45].

Regarding the constitutive assumptions in the FEM simulations, the structure was modeled as a linear viscoelastic material. In the absence of in situ experimental data, the mechanical parameters were calibrated using a two-tiered methodology to ensure reliability. This approach consolidated code-compliant values from NTC 2018 [57] with empirical data derived from specific studies on traditional masonry structures in the Mt. Etna area. More specifically, the Young’s modulus (E) was assigned following the values recommended by NTC 2018 [57] for stone masonry. Poisson’s ratio (ν) and the unit weight (γweight) of the masonry were derived from values reported in the literature [88]. Furthermore, an eigenvalue analysis of the final bell-tower model yielded a first fundamental period (1.66 s) that is consistent with the empirical formula provided by NTC 2018 [57], providing further validation of the model’s accuracy. Table 2 reports on the values adopted for FEM analysis.

Table 2.

Parameters for the linear viscoelastic constitutive model adopted for modeling the masonry structure.

As for the soil layers, the elasto-plastic Hardening Soil with small strain stiffness model, denoted as HSsmall model [89], and the nonlinear Generalized Hoek-Brown model, denoted as GHB model [90], were adopted to reproduce the behavior of the LC layers (volcanic sand) and of the SFALS layers (fractured geological substrate), respectively.

The HSsmall model parameters were calibrated and validated following the methodology proposed in the literature [45,91,92]. More specifically, the initial shear modulus reference corresponding to the reference confining pressure of 100 kPa (G0ref) was directly estimated from the shear wave velocity profile obtained from field MASW tests. The power law coefficient (m) was set to 0 to model a constant small-strain shear modulus with depth for each stratum. The shear strain at which the secant shear modulus is equivalent to 70% of the shear modulus at small strains (γ0.7) was selected to achieve the best fit between the numerical and experimental normalized shear modulus reduction (G/G0 vs. γ) and damping ratio (D vs. γ) curves from the literature (Figure 3b). The reference stiffness moduli (E50ref, Eoedref, Eurref) were evaluated according to established recommendations, as fully described in Fiamingo et al. [45]. The Poisson’s ratio for unloading-reloading (νur) was taken as 0.25, based on Obrzud [93]. The coefficient of earth pressure at rest (k0), was estimated using the formulation proposed by Jâky [94] for coarse-grained soils. The failure ratio (Rf) was assumed to be 0.9, which is the standard default value. Finally, the cohesion (c′), friction angle (φ′), dilatancy angle (ψ), and small-strain damping ratio (D0) were taken from previous laboratory studies on similar volcanic soils in the Catania area [60,61,95]. Additionally, the soil’s cyclic response was evaluated numerically through 3D FEM simulations using MIDAS FEA NX software [85], which replicated cyclic triaxial tests under a confining pressure of 100 kPa. A half-cylindrical specimen (100 mm × 200 mm) was discretized into hybrid solid elements, with boundary conditions reproducing those of a cyclic triaxial apparatus: y-displacements constrained on the sectioned face and z-displacements fixed at the base. The analyses reproduced the two main phases of triaxial testing: consolidation and cyclic shearing. The HSsmall parameters adopted for the LC layers are reported in Table 3; further details about the interpretation and validation are provided in Fiamingo et al. [45].

Table 3.

Parameters for the HSsmall constitutive model adopted for modeling the LC soil layers.

The GHB model parameters were calibrated and validated following the literature data on the mechanical behavior of volcanic rocks from the Mt. Etna area [96,97,98,99]. The model parameters were primarily derived from empirical relationships and literature values specific to Mt. Etna’s volcanic rocks. The Young’s Modulus (E) was estimated from shear wave velocity data, the intact rock strength (σci) and material constant (mi) were defined based on massive specimen data [99] and porosity relationships [100]. ν was fixed equal to 0.20 according to Cavallaro et al. [60]. The rock mass quality was characterized using a standard Geological Strength Index (GSIrock), considering an average value for lavas and lava breccias [98], while the disturbance factor (Dfactor) was assumed equal to 0 (undisturbed in situ rock mass). The GHB strength parameters (mb, s*, a) were evaluated according to the data provided for the mechanical behavior of volcanic rocks from the Mt. Etna area [96,97,98,99], while ψ and D0 were defined directly from previous dynamic studies on similar volcanic soils in the Catania areas [60,61]. The GHB parameters adopted for the SFALS layers are reported in Table 4; further details about the interpretation and validation are provided in Fiamingo et al. [45]. Rayleigh damping was assigned to all materials. A damping ratio of 8% was assumed for the structure, according to NTC 2018 [57], and 1% for the LC and SFALS soil layers [95]. At the base of the model, seismic motion set #3 was applied to investigate the SSI effects in detail.

Table 4.

Parameters for the GHB constitutive model used to model the SFALS soil layers.

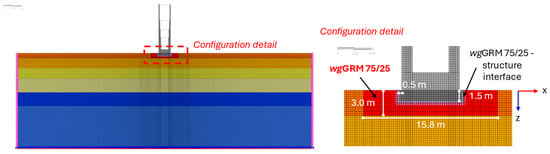

4.2. Finite Element Model of the Bell-Tower-Soil System with Geotechnical Seismic Isolation (GSI) System

In this study, the effectiveness of GSI systems in mitigating seismic risk is assessed. In particular, attention is given to the performance of well-graded Gravel–Rubber Mixtures (wgGRMs) with a 25% volumetric rubber content (hereafter referred to as wgGRMs 75/25), applied beneath and alongside the foundation of the St. Giovanni Evangelista bell-tower. The behavior of the adopted wgGRMs 75/25 has been thoroughly investigated in the literature [48,49] through drained monotonic triaxial tests, bender element tests, and drained cyclic triaxial tests. In the present study, the structure is fully isolated by a wgGRMs 75/25 layer with a height of 3.00 m and a total width of 15.80 m. To analyze the performance of this mixture, a finite element model (FEM) was developed (Figure 12) with the same characteristics as the reference FEM model described in Section 4.1. The comparison of the FEM model results allows us to highlight how wgGRMs 75/25 can affect the performance of the structure, providing insights into its suitability as a GSI system.

Figure 12.

Two-dimensional FEM model of the fully coupled bell-tower-soil system, including wgGRMs 75/25.

The wgGRMs 75/25 layer was discretized using plane-strain four-node solid elements with a mesh size that satisfied the criterion of being smaller than one-eighth of the shortest wavelength of the input signal [86]. The HSsmall model was adopted to reproduce the mechanical behavior of the mixture. The calibration and validation of the HSsmall model parameters were performed following an iterative trial-and-error procedure proposed by Fiamingo et al. [101]. Specifically, it was based on the results of monotonic drained triaxial compression tests conducted on wgGRMs under a confining pressure of 100 kPa, as reported in Fiamingo et al. [48]. These monotonic triaxial tests were reproduced through FEM simulations of a half-cylindrical specimen, consistent with the configuration described in Section 4.1, and employing the same 3D elements and boundary conditions. Regarding the loading conditions, both the isotropic consolidation phase and the monotonic shearing phase were considered. As for the parameters of the HSsmall model, already presented in Section 4.1 for LC layers, G0ref was determined from bender element tests conducted in a prior study on the same mixtures [49]. m was fine-tuned using an iterative optimization process. γ0.7 was derived from data obtained in cyclic triaxial tests [49]. E50ref, Eoedref and Eurref were calibrated by a trial-and-error procedure, as fully described in Fiamingo et al. [45]. νur was taken as 0.30, based on Fiamingo et al. [101]. k0, was estimated using the formulation proposed by Jâky [94] for coarse-grained soils. Rf was another parameter finalized through the iterative calibration process, according to Fiamingo et al. [101]. Finally, c′, φ′, ψ, and D0 were sourced directly from the comprehensive laboratory characterization of the mixtures [48,49]. Table 5 summarizes the HSsmall parameters adopted for the wgGRMs 75/25 layer; further details about the interpretation and validation are provided in Fiamingo et al. [45]. Rayleigh damping was assigned to the wgGRMs 75/25, assuming a damping ratio equal to 4%, according to Fiamingo et al. [49]. At the base of the model, seismic motion set #3 was applied to investigate the SSI effects in detail, the same set adopted for the model without wgGRMs.

Table 5.

Parameters for the HSsmall constitutive model used to model the wgGRMs 75/25.

5. Results

5.1. Large-Scale SSI Effects from the GIS-Integrated Framework

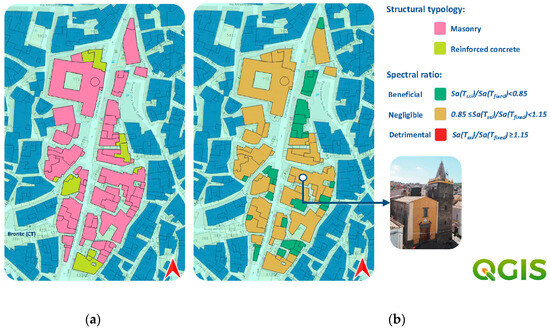

The large-scale evaluation of SSI effects, based on the GIS-integrated methodological framework described in Section 3, was applied to 70 buildings surrounding the Church of San Giovanni Evangelista. The built environment in the study area (Figure 13a) is predominantly composed of masonry structures, with only a few reinforced concrete structures. For each structure, the developed GIS-integrated methodological framework provides the ratio Sa(TSSI)/Sa(Tfixed), which serves as an indicator of SSI effects: values ≤ 0.85 denote SSI beneficial effects, values between 0.85 and 1.15 indicate SSI negligible effects, and values > 1.15 correspond to SSI detrimental effects. These indicators are derived from the studies by Rovithis et al. [27] and Abate et al. [12], in which the ratio between spectral accelerations under flexible-base and fixed-base conditions is used as a quantitative parameter for assessing the influence of SSI. The results (Figure 13b) show that no buildings exhibit detrimental SSI effects, as no spectral ratio exceeded 1.15 (yellow area). Most structures display negligible effects, regardless of construction type, while a smaller number benefit from SSI, represented in the green area. Regarding the investigated bell-tower, it appears that the SSI effects are negligible. It is essential to note that these results pertain to a rapid SSI analysis, suitable for a preliminary investigation of large urban areas, and must be confirmed or refuted by integrating FEM modeling of each structure within the framework. The FEM model captures the complex dynamic interaction between soil and structures in more detail, allowing for a more realistic assessment of spectral response ratios, Sa(TSSI)/Sa(Tfixed). This combination of GIS-based large-scale evaluation and FEM-based structural modeling ensures both spatial coverage and analytical depth, making the methodology robust and suitable for application in different urban contexts.

Figure 13.

Results obtained from the large-scale evaluation of the SSI effects: (a) Structural typologies, (b) spatial distribution of Sa(TSSI)/Sa(Tfixed) ratios.

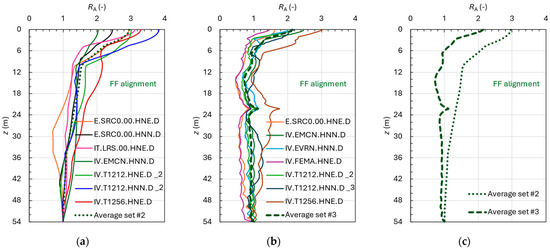

5.2. Detailed SSI Effects from FEM Simulations

The 2D FEM analyses enable the comparison of large-scale and detailed simulations of the San Giovanni Evangelista bell-tower, thereby assessing SSI effects and providing valuable insights into the accuracy of the large-scale procedure. The first step involved evaluating the seismic response of the soil along the Free-Field (FF) alignment (highlighted in Figure 11). This was achieved by comparing the LSR analyses carried out using the STRATA software for seismic motion set #2, which was adopted for the large-scale evaluation of SSI effects (see Section 3), with the FEM analyses performed for seismic motion set #3 (Figure 14). Figure 14a,b present the amplification ratio profiles RA(z) obtained for motion sets #2 and #3, respectively, while Figure 14c shows the average amplification ratio profiles for both sets. RA is the ratio between the ag at a given depth z and ag at the base of the model. As seen in Figure 14a,b, values of RA ≈ 1 are observed for depths z ≥ 24m, which is consistent with the high stiffness of the SFALS layers. For shallower depths (z < 24 m), the RA increases due to the softer behavior of the LC layers, characterized by low Vs, particularly near the soil surface. Notably, the FEM results for motion set #3 (Figure 14b) yield lower RA values than those obtained from the LSR analyses for motion set #2 (Figure 14a), as further confirmed by the average profiles in Figure 14c. This difference can be attributed to the soil nonlinearity accounted for by the HSsmall constitutive model in the FEM simulations. In contrast, the equivalent linear visco-elastic constitutive model employed in the LSR analyses is unable to fully capture the nonlinear variation in soil stiffness and damping under high shear strain levels, leading to systematically different predictions. This highlights the importance of explicitly modeling soil nonlinearity to obtain more realistic estimates of site response and SSI effects. Figure 15a–g compare the amplification ratio profiles, RA(z), obtained from the FEM analyses along the two reference alignments: the SSI alignment (beneath the tower) and the FF alignment (highlighted in Figure 11). For all seismic motions of set #3, the two profiles exhibit very similar trends up to a depth of about 24 m, indicating that soil response is primarily governed by stratigraphy and input motion in the deeper layers. Above this depth, however, the presence of the structure increasingly influences the response. Along with the SSI alignment, RA(z) values progressively exceed those of the free-field case, with the most significant differences occurring near the soil surface. This indicates that the presence of the structure modifies the stress–strain state of the near-surface soil. These differences demonstrate the coupling between soil and structure, validating the necessity of explicitly incorporating SSI effects in the seismic assessment of structures. The findings also show that localized soil–structure coupling can produce non-uniform acceleration fields at the foundation, an aspect that cannot be captured by conventional free-field analyses.

Figure 14.

Amplification ratio profiles RA(z) evaluated for the Free-Field alignment and different seismic motion sets: (a) seismic motion set #2; (b) seismic motion set #3; (c) average profiles from set #2 and #3.

Figure 15.

The amplification ratio profiles RA(z) for the SSI and FF alignments under the seismic motions of set #3: (a) E.SRC0.00.HNE.D; (b) IV.EMCN.HNN.D; (c) IV.EVRN.HNN.D; (d) IV.FEMA.HNE.D; (e) IV.T1212.HNE.D_2; (f) IV.T1212.HNN.D_3; (g) IV.T1256.HNE.D.

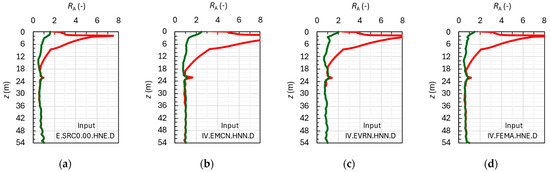

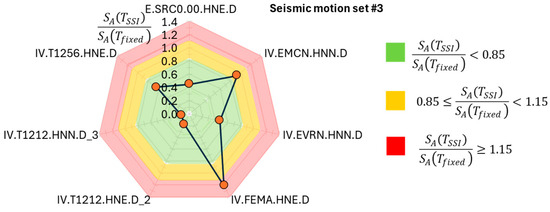

The assessment of SSI effects was conducted by computing the ratio Sa(TSSI)/Sa(Tfixed) for each seismic motion in set #3, as illustrated in Figure 16. The definition of TSSI is central to this evaluation; for this detailed analysis, it was determined from the first-mode frequency of the amplification function. This function is defined as the absolute value ratio of the Fourier spectrum at the roof of the structure to the Fourier spectrum at its foundation. The value for Tfixed was consistently adopted from the previous analysis detailed in Section 3.2, ensuring a coherent basis for comparison.

Figure 16.

Detailed-scale evaluation of SSI effects on the bell-tower evaluated through the SA(TSSI)/SA(Tfixed) ratio.

In the large-scale evaluation (Figure 13), and particularly for the bell-tower within the urban dataset, this ratio ranges from 0.85 to 1.15, indicating that SSI effects are negligible at this level of analysis. In contrast, the detailed FEM evaluation of the bell-tower (Figure 16) yields ratios predominantly below 0.85, indicating that SSI leads to a systematic reduction in spectral demand—a beneficial effect in terms of seismic response. This is essentially due to the previously commented soil nonlinearity effects that induce a decrease in the RA values (Figure 14). In practical terms, these results emphasize the need for a multi-tiered assessment strategy: large-scale SSI evaluations are effective for rapid mapping and risk prioritization, but heritage structures of exceptional value (like bell towers) require refined SSI modelling to capture the beneficial/detrimental reduction in demand and to design tailored, cost-effective interventions. These results also confirm the reliability of the large-scale GIS-based procedure, which predicted predominantly non-detrimental SSI effects in the same area.

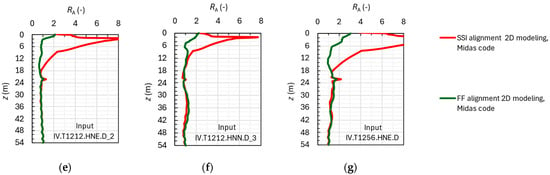

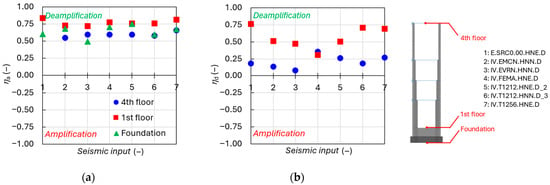

5.3. Effectiveness of the GSI Retrofitting Strategy

As part of the investigation into innovative GSI systems, this section evaluates the effectiveness of wgGRMs 75/25 in reducing seismic acceleration in the bell-tower. The analysis compares the results of the FEM model without wgGRMs (described in Section 4.1) to those of the FEM model with wgGRMs placed at the base and around the bell-tower’s foundation (described in Section 4.2). As previously mentioned, all FEM analyses were performed considering seismic motion set #3. The efficiency of the proposed wgGRMs 75/25 is analyzed, assuming the maximum horizontal accelerations (ηa, depicted in Figure 17a) and maximum drifts (ηd, depicted in Figure 17b) at the foundation and at different floors, as indices of the structure’s performance, according to Somma et al. [102]. They are defined as:

where amax,GSI is the maximum horizontal acceleration for the configurations with GSI system (i.e., configuration with wgGRMs 75/25), amax,NO GSI is the maximum horizontal acceleration for the configuration without GSI systems (i.e., configurations with no mixture), ud,max,GSI is the maximum drift for the configurations with GSI systems, ud,max,NO GSI is the maximum drift for the configuration without GSI systems.

Figure 17.

Efficiency of the wgGRMs 75/25 layer placed at the base of the bell-tower: (a) maximum horizontal accelerations (ηa); (b) maximum drift (ηd).

It is worth noting that drift is computed as:

where ux,dyn,floor is the dynamic horizontal displacement at each floor, ux,dyn,found is the dynamic horizontal displacement of the foundation, θ is the rocking angle (calculated from the vertical displacement of the two foundation corners), and h is the floor-to-floor height.

As illustrated in Figure 17a, the GSI system provides a de-amplification of seismic acceleration, approximately 60%, which is consistent across the foundation, 1st floor, and 4th floor of the bell-tower. A similar trend is observed for drift (Figure 17b), where a de-amplification of approximately 30% is achieved on average.

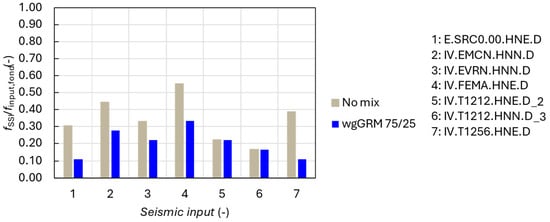

These reductions indicate that the wgGRMs 75/25 layer effectively dissipates seismic energy and decouples the structure from the ground motion. Importantly, the improvement is achieved without any structural alteration, aligning with conservation requirements for heritage buildings. The data confirm that ground-based isolation can enhance seismic performance while maintaining architectural authenticity and sustainability by utilizing recycled materials. Figure 18 illustrates the ratio between the fundamental frequency of the structure, accounting for SSI effects, and the input frequency at the foundation level (fSSI/finput, found) for each analyzed seismic motion in set #3. The results clearly highlight the influence of the wgGRMs: their inclusion systematically reduces the values of fSSI/finput,found compared to the configuration without wgGRMs. The decrease in fSSI/finput,found values, suggests that the wgGRMs increase the effective flexibility of the soil–structure system. This additional compliance shifts the system away from potentially harmful resonance conditions, promoting a safer dynamic response under seismic loading. The observed frequency shift confirms the dual role of wgGRMs: they provide energy dissipation and modify system dynamics to achieve a more favorable frequency separation between soil and structure.

Figure 18.

Variation in the frequency ratio fSSI/finput,found with ground motion.

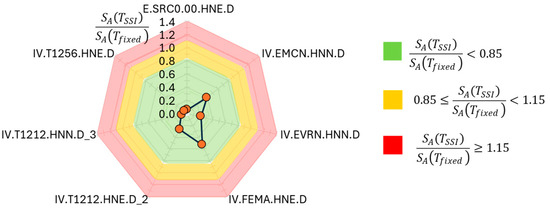

The beneficial influence of the wgGRMs is further confirmed in Figure 19, which reports the ratio Sa(TSSI)/Sa(Tfixed). The results consistently show values below 0.85, indicating that SSI effects contribute positively to the seismic response of the structure. When compared with the configuration without wgGRMs (Figure 16), the ratios obtained with wgGRMs are significantly lower, demonstrating that the inclusion of the mixture enhances the beneficial impact of SSI. This reduction highlights the wgGRMs 75/25 amplifies the beneficial influence of SSI by increasing damping and reducing stiffness contrasts at the interface. Consequently, seismic energy transmitted to the structure is minimized, improving overall safety without invasive intervention.

Figure 19.

Evaluation of SSI effects including wgGRMs 75/25 at the base of the bell-tower evaluated through the SA(TSSI)/SA(Tfixed) ratio.

Results suggest that this system is a promising low-impact ground-based isolation system that can improve seismic safety while fully preserving the historical and esthetic integrity of the structure. As a ground-based solution, it improves seismic performance by modifying Soil–Structure Interaction rather than modifying the structure itself [32,34,35,45,46,66,92]. As evidenced by the results, the incorporation of wgGRMs beneath the foundation effectively reduces the transmission of seismic energy.

Finally, the comparison between large-scale and detailed-scale results demonstrates the hierarchical consistency of the framework: the GIS-based analysis correctly predicted negligible SSI effects for the bell-tower area, which the detailed FEM model confirmed and refined, revealing beneficial SSI behavior when nonlinear soil effects are included.

6. Discussion

The combined use of a large-scale GIS-based framework and a detailed FEM model demonstrates that multi-level approaches can effectively bridge the gap between urban-scale seismic risk mapping and site-specific engineering design.

At the large scale, the GIS-integrated analysis allowed rapid screening of 70 buildings in the historic center of Bronte, automatically incorporating local geotechnical conditions into SSI assessment. The resulting spectral acceleration ratios, Sa(TSSI)/Sa(Tfixed), predominantly ranged between 0.85 and 1.15, indicating that SSI effects are negligible or slightly beneficial for most structures.

At the detailed scale, the FEM analysis of the San Giovanni Evangelista bell-tower revealed that, once soil nonlinearity and rocking mechanisms are captured, SSI effects can further reduce the seismic demand (Sa(TSSI)/Sa(Tfixed) < 0.85). This consistency in trend—non-detrimental SSI at both scales—validates the reliability of the GIS-based screening method while demonstrating the added accuracy of detailed modeling. Importantly, the comparison highlights that while the GIS framework efficiently identifies risk-prone zones, it cannot fully capture nonlinear soil behavior; therefore, the two levels of analysis must be seen as complementary and interdependent rather than alternative.

The observed beneficial SSI effects at the detailed scale can be attributed to two main mechanisms: the increase in the effective fundamental period (TSSI), which shifts the structure’s response away from the predominant frequencies of the input motion, and the enhancement of damping due to hysteretic energy dissipation in the foundation soils. The bell-tower’s slender geometry and relatively massive foundation promote partial uplift and rocking during dynamic excitation, reducing the seismic acceleration transmitted to the superstructure. This phenomenon, often disregarded in simplified fixed-base models, plays a decisive role in the seismic performance of heritage masonry towers.

One of the most innovative aspects of this research is the introduction of a GSI layer composed of wgGRMs 75/25 placed beneath the tower’s foundation. The detailed FEM analyses revealed that this inclusion substantially improves seismic performance, with maximum horizontal accelerations reduced by approximately 60% and inter-story drifts by about 30% compared to the unmodified soil configuration. These improvements arise from the low stiffness and high damping of the wgGRMs, which decouple the structure from the input motion and dissipate seismic energy at the soil–foundation interface.

In addition to their mechanical effectiveness, wgGRMs offer significant environmental and conservation advantages. The mixture reuses waste tire rubber, aligning with circular-economy and sustainability goals, while operating entirely below the structure, thus preserving the architectural integrity of the heritage asset. This represents a paradigm shift from traditional, intrusive strengthening methods (e.g., jacketing or base isolation systems) toward ground-based, reversible, and low-impact retrofitting solutions. Considering the tower’s historical context and its adjacency to other buildings on two sides, practical implementation of wgGRMs could be achieved through localized and staged underpinning techniques commonly adopted in heritage conservation works. In such cases, excavation could be performed in small sections beneath the foundation, proceeding sequentially and ensuring continuous structural support. The wgGRMs layer could then be placed in each section before advancing to the next. Where the tower is contiguous with neighboring structures, lateral installation could be limited to the accessible sides (front and rear), with wgGRMs inserted beneath the full foundation footprint and, where possible, laterally extended.

The proposed methodology demonstrates both high applicability and accuracy in the context of seismic risk assessment for historic urban areas. Its applicability lies in the use of open-source GIS platforms, publicly available microzonation and cadastral datasets, and code-based seismic parameters, which make the workflow fully replicable for other cities with similar data availability. The modular structure of the “Master Buildings” layer enables the direct integration of new data sources and facilitates large-scale urban screening by non-specialist users, such as municipal engineers or heritage authorities. The accuracy of the approach has been confirmed through multi-level validation. First, the large-scale GIS-based predictions of SSI effects were quantitatively verified by detailed FEM simulations on the San Giovanni Evangelista bell-tower, showing consistent trends (i.e., negligible to beneficial SSI effects). Second, the numerical parameters adopted for soils and materials were derived from field investigations and laboratory-tested mechanical properties of volcanic soils and wgGRMs, ensuring realistic model behavior. Third, the seismic input motions were selected using the Rexel WEB tool in compliance with national code spectral criteria, ensuring statistical representativeness.

The combined GIS–FEM methodology developed here can serve as a replicable model for other historic centers in seismic-prone areas. The GIS-based level enables authorities to prioritize interventions, while the FEM-based level provides quantitative support for the design and validation of conservation-compatible solutions.

7. Conclusions

This study proposed an integrated, multi-scale methodological framework for the seismic risk assessment and sustainable protection of historic buildings, with specific attention to Soil–Structure Interaction (SSI) and innovative Geotechnical Seismic Isolation (GSI) strategies. The framework was applied to the historic center of Bronte (Eastern Sicily, Italy), combining a large-scale GIS-based assessment with a detailed-scale FEM simulation of a representative heritage structure—the San Giovanni Evangelista bell-tower.

At the large scale, the GIS-integrated approach successfully merged geotechnical, seismological, and structural datasets to produce thematic maps that quantify potential SSI effects across more than 70 buildings. This first analytical level provided a spatial overview and identified priority zones for further investigation. Results showed that SSI effects were predominantly negligible or beneficial across the urban area, demonstrating the method’s suitability as a screening and prioritization tool for heritage management and seismic planning.

At the detailed scale, the Finite Element Method (FEM) analyses of the San Giovanni Evangelista bell-tower provided a higher-fidelity understanding of SSI mechanisms compared to the large-scale evaluation based on the GIS-integrated methodological framework. While the GIS-based evaluation suggested negligible SSI effects, the FEM results highlighted beneficial SSI effects, with the ratio between spectral acceleration at the building’s fundamental period considering SSI and spectral acceleration at the building’s fundamental period under fixed-base conditions (Sa(TSSI)/Sa(Tfixed)) consistently below 0.85. This divergence underscores the importance of multilevel approaches: large-scale GIS mapping is suitable for rapid seismic risk screening, while landmark heritage structures require detailed SSI modeling to capture nonlinear soil behavior and structural-soil interaction.

The detailed analysis further demonstrated the effectiveness of a GSI system using well-graded Gravel–Rubber Mixtures (wgGRMs 75/25). The introduction of this layer beneath the tower’s foundation produced substantial improvements in seismic performance. FEM analyses demonstrated a reduction of up to 60% in maximum horizontal accelerations and approximately 30% in inter-story drifts. The GSI system also increased overall flexibility, shifted the dynamic response away from resonance conditions, and enhanced beneficial SSI effects, confirming its viability as a low-impact and sustainable retrofitting solution.

The research highlights several practical implications. First, the GIS-integrated framework provides a readily accessible, replicable tool for local authorities and engineers to prioritize interventions in historic centers, combining seismic microzonation data with structural information. Second, the detailed FEM analysis confirms that wgGRMs are a low-impact, sustainable Geotechnical Seismic Isolation (GSI) system. They effectively reduce seismic accelerations while preserving architectural integrity. This is particularly valuable for retrofitting heritage assets, where conventional methods (e.g., reinforced concrete jackets, steel bracing) may be expensive and alter their architectural identity. The wgGRMs system is both cost-effective and environmentally sustainable, making it suitable for use in sensitive heritage contexts that align with conservation principles and sustainable retrofitting goals.

However, some limitations should be acknowledged. The GIS-based procedure relies on simplified period–height relationships and equivalent single-degree-of-freedom models to estimate the fundamental period of each structure and its modification due to SSI. These assumptions are suitable for rapid urban-scale screening but do not capture the full dynamic complexity of irregular masonry buildings or the influence of local geometric discontinuities, structural degradation, and anisotropic material behavior. The microzonation-derived spectra incorporated into the GIS framework are computed using equivalent linear soil behavior. While this approach is compatible with national guidelines and widespread in seismic microzonation practice, it does not fully represent nonlinear soil stiffness degradation and damping increase under strong shaking, potentially leading to discrepancies when compared with fully nonlinear FEM results. The detailed analysis of the bell-tower employs a 2D plane-strain formulation, which cannot accurately reproduce 3D effects such as torsional response, out-of-plane deformation, localized cracking, or complex boundary interactions with the adjacent church. The tower was modeled as dynamically independent, consistent with historical evidence; however, some degree of coupling may persist in reality. Therefore, the results should be interpreted as first-order estimates of the governing SSI mechanisms. Due to the absence of on-site mechanical testing on the historic masonry, the structural parameters were assumed based on NTC 2018 recommendations and literature data from similar Mt. Etna constructions. These assumptions, while justified and widely adopted in heritage assessment practice, introduce uncertainties regarding the actual stiffness and damping of the soil–foundation–structure system.

The framework is intended as a decision-support tool for prioritizing interventions and conducting preliminary assessments. For the final design of protection measures or restoration works, more detailed 3D nonlinear models, site-specific soil investigations, and structural monitoring of the heritage assets should be carried out. Despite these limitations, the methodology provides a robust and replicable procedure for linking urban-scale SSI screening with site-specific seismic assessment and for evaluating sustainable, minimally invasive retrofitting solutions in heritage environments.

Future research should extend the methodology to different urban contexts, integrate real-time monitoring systems, and explore hybrid solutions that combine GSI with other conservation-compatible retrofitting techniques. Additionally, a fully coupled 3D model would provide a more comprehensive analysis, considering the interaction with the nearby church building.

In summary, the integration of GIS-based SSI evaluation, FEM-based detailed modeling, and innovative GSI solutions demonstrates a powerful and sustainable approach to safeguarding architectural heritage. This research highlights that sustainable GSI systems, such as wgGRMs, can significantly enhance resilience while respecting cultural values, thus contributing to the long-term protection of vulnerable historic structures in seismic-prone areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F., E.M., G.A. and M.R.M.; methodology, A.F., E.M., G.A. and M.R.M.; software, A.F. and E.M.; validation, A.F. and E.M.; formal analysis, A.F. and E.M.; investigation, A.F. and E.M.; resources, A.F., E.M., G.A. and M.R.M.; data curation, A.F. and E.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F. and E.M.; writing—review and editing, A.F., E.M., G.A. and M.R.M.; visualization, A.F. and E.M.; supervision, G.A. and M.R.M.; project administration, G.A. and M.R.M.; funding acquisition, M.R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project is funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR)—Mission 4 Education and research—Component 2 From research to business—Investment 1.3, Notice D.D. 341 of 15 March 2022 entitled: Cultural Heritage Active Innovation for Sustainable Society proposal code PE0000020—CUP E63C22001960006, duration until 28 February 2026.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author, as the dataset is too large to be shared publicly.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| a | Rock mass material constant for the GHB model |

| ag | Peak ground acceleration |

| amax,GSI | Maximum acceleration for the configurations with GSI systems |

| amax,NO GSI | Maximum acceleration for the configurations without GSI systems |

| c | Cohesion |

| Cc | Dynamic amplification factor |

| D | Damping ratio |

| D0 | Damping ratio at small strain |

| Dfactor | Disturbance factor for the GHB model |

| DSSI | Damping ratio considering SSI effects |

| E | Young’s modulus |

| ELT | End-of-Life Tires |

| E50ref | Reference secant stiffness in the standard triaxial test to pref |

| Eoedref | Reference tangent stiffness for the primary oedometer loading condition to pref |

| Eurref | Reference unloading-reloading Young modulus to pref |

| F0 | Acceleration response spectrum amplification factor |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| FF | Free-Field |

| fSSI | Fundamental frequency of the structure considering SSI effects |

| finput,found | Foundation input frequency |

| G | Shear modulus |

| G/G0 | Normalized shear modulus |

| G0ref | Initial shear modulus reference corresponding to the pref |

| GHB | Generalised Hoek-Brown |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GSI | Geotechnical Seismic Isolation |

| GSIrock | Geological Strength Index |

| h | Floor-to-floor height |

| HSsmall | Hardening Soil with small strain stiffness |

| k0 | Coefficient of earth pressure at rest |

| LSR | Local Seismic Response |

| m | Power Law Coefficient of the HSsmall model |

| MASW | Multichannel Analysis of Surface Waves |

| mb | Rock mass material constant for the GHB model |

| mi | Material constant for the intact rock |

| MOPS | Microzones Homogeneous in Seismic Perspective |

| MS | Seismic Microzonation |

| Mw | Moment magnitude |

| OGC | Open Geospatial Consortium |

| pref | Reference confining pressure |

| R | Epicentral distance |

| RA | Amplification Ratio |

| Rf | Failure ratio |

| S | Amplification factor |

| s* | Rock mass material constant for the GHB model |

| Sa(Tfixed) | Spectral acceleration at the building’s fundamental period under fixed-base conditions |

| Sa(TSSI) | Spectral acceleration at the building’s fundamental period considering SSI |

| SM | Seismic Microzonation |

| Ss | Stratigraphic amplification factor |

| SSI | Soil-Structure Interaction |

| ST | Topographic amplification factor |

| T | Period |

| T*c | Constant-velocity segment of the spectrum |

| Tb | Period marking the beginning of the constant-velocity branch |

| Tc | Period marking the end of the constant-velocity branch/beginning of the constant-acceleration branch |

| Td | Period marking the end of the constant-displacement branch |

| Tfixed | Fundamental period of the building assuming fixed-base conditions |

| TSSI | Fundamental period of the building considering SSI |

| ux,dyn,floor | Dynamic horizontal displacement at each floor |

| ux,dyn,found | Dynamic horizontal displacement of the foundation |

| VN | Nominal life |

| Vs | Shear wave |

| Vs,30 | Weighted average shear-wave velocity in the upper 30 m |

| Vseq | Equivalent shear-wave velocity |

| WFS | Web Feature Service |

| wgGRMs | Well-graded Gravel-Rubber Mixtures |

| WMS | Web Map Service |

| z | Vertical depth |

| σci | Unconfined compressive strength |

| γ | Shear strain |

| γ0.7 | Shear strain at which the secant shear modulus is equivalent to 70% of the shear modulus at small strains |

| γweight | Unit weight |

| ν | Poisson’s ratio |

| νur | Poisson’s ratio for unloading-reloading |

| φ | Shear strength angle |

| ψ | Dilatancy angle |

| ηa | Efficiency in terms of the maximum horizontal accelerations |

| ηd | Efficiency in terms of the maximum drift |

| θ | rocking angle |

References

- Barbieri, G.; Biolzi, L.; Bocciarelli, M.; Fregonese, L.; Frigeri, A. Assessing the seismic vulnerability of a historical building. Eng. Struct. 2013, 57, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagomarsino, S. On the vulnerability assessment of monumental buildings. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2006, 4, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pasquale, G.; Orsini, G.; Romeo, R.W. New Developments in Seismic Risk Assessment in Italy. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2005, 3, 101–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolce, M.; Prota, A.; Borzi, B.; da Porto, F.; Lagomarsino, S.; Magenes, G.; Moroni, C.; Penna, A.; Polese, M.; Speranza, E.; et al. Seismic risk assessment of residential buildings in Italy. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 19, 2999–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, G.; Corsico, S.; Fiamingo, A.; Grasso, S.; Massimino, M.R. Evaluation of DSSI for the preservation of the Catania University Central Palace. In Geotechnical Engineering for the Preservation of Monuments and Historic Sites III; Lancellotta, R., Viggiani, C., Flora, A., de Silva, F., Mele, L., Eds.; CRC Press/Balkema: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiamingo, A.; Massimino, M.R. Geotechnical Analyses for the Preservation of Historical Churches: A Case-History in Eastern Sicily (Italy). In Environmental Challenges in Civil Engineering III. ECCE 2024., Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Environmental Challenges in Civil Engineering, Opole, Poland, 22–24 April 2024; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, Perkowski, Z., Beben, D., Zembaty, Z., Massimino, M.R., Oliveira, M.J., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcellini, D. The Role of the Water Level in the Assessment of Seismic Vulnerability for the 23 November 1980 Irpinia–Basilicata Earthquake. Geosciences 2020, 10, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcellini, D. The assessment of the interaction between base isolation (BI) technique and soil structure interaction (SSI) effects with 3D numerical simulations. Structures 2022, 45, 1452–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Zhang, W.; Forcellini, D.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, J. Dynamic centrifuge modeling on the superstructure–pile system considering pile–pile cap connections in dry sandy soils. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 187, 108979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, A.; Sica, S. The role of underground archaeological remains on the seismic response of a historic tower. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 187, 109017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeolla, E.; Brunelli, A.; de Silva, F.; Cattari, S.; Sica, S. Fragility curves of URM buildings in aggregate considering the interaction with soil and among nearby footings. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 23, 3589–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abate, G.; Bramante, S.; Massimino, M.R. Innovative Seismic Microzonation Maps of Urban Areas for the Management of Building Heritage: A Catania Case Study. Geosciences 2020, 10, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veletsos, A.S.; Meek, J. Dynamic behavior of building-foundation systems. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1974, 3, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazetas, G. Analysis of machine foundation vibrations: State of the art. Int. J. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 1983, 2, 2–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.P.; Seed, R.B.; Fenves, G. Seismic soil-structure interaction in buildings II: Empirical findings. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 1999, 125, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonakis, G.; Gazetas, G. Seismic soil-structure interaction: Beneficial or detrimental? J. Earthq. Eng. 2000, 4, 277–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonakis, G.; Syngros, C.; Gazetas, G.; Tazoh, T. The role of soil in the collapse of 18 piers of Hanshin Expressway in the Kobe earthquake. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2006, 35, 547–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovithis, E.; Pitilakis, K.; Mylonakis, G. Seismic analysis of coupled soil-pile-structure systems leading to the definition of a pseudo-natural SSI frequency. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2009, 29, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabozzi, S.; Catalano, S.; Falcone, G.; Naso, G.; Pagliaroli, A.; Peronace, E.; Porchia, A.; Romagnoli, G.; Moscatelli, M. Stochastic approach to study the site response in presence of shear wave velocity inversion: Application to seismic microzonation studies in Italy. Eng. Geol. 2021, 280, 105914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]